Abstract

Objectives

In this large multicentre study, we compared the effectiveness and safety of tocilizumab intravenous versus subcutaneous (SC) in 109 Takayasu arteritis (TAK) patients.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective multicentre study in referral centres from France, Italy, Spain, Armenia, Israel, Japan, Tunisia and Russia regarding biological-targeted therapies in TAK, since January 2017 to September 2019.

Results

A total of 109 TAK patients received at least 3 months tocilizumab therapy and were included in this study. Among them, 91 and 18 patients received intravenous and SC tocilizumab, respectively. A complete response (NIH <2 with less than 7.5 mg/day of prednisone) at 6 months was evidenced in 69% of TAK patients, of whom 57 (70%) and 11 (69%) patients were on intravenous and SC tocilizumab, respectively (p=0.95). The factors associated with complete response to tocilizumab at 6 months in multivariate analysis, only age <30 years (OR 2.85, 95% CI 1.14 to 7.12; p=0.027) and time between TAK diagnosis and tocilizumab initiation (OR 1.18, 95% CI 1.02 to 1.36; p=0.034). During the median follow-up of 30.1 months (0.4; 105.8) and 10.8 (0.1; 46.4) (p<0.0001) in patients who received tocilizumab in intravenous and SC forms, respectively, the risk of relapse was significantly higher in TAK patients on SC tocilizumab (HR=2.55, 95% CI 1.08 to 6.02; p=0.033). The overall cumulative incidence of relapse at 12 months in TAK patients was at 13.7% (95% CI 7.6% to 21.5%), with 10.3% (95% CI 4.8% to 18.4%) for those on intravenous tocilizumab vs 30.9% (95% CI 10.5% to 54.2%) for patients receiving SC tocilizumab. Adverse events occurred in 14 (15%) patients on intravenous route and in 2 (11%) on SC tocilizumab.

Conclusion

In this study, we confirm that tocilizumab is effective in TAK, with complete remission being achieving by 70% of disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs-refractory TAK patients at 6 months.

Keywords: Autoimmune Diseases, Systemic vasculitis, Inflammation

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ON THIS TOPIC

Summarise the state of scientific knowledge on this subject before you did your study and why this study needed to be done Few high-quality evidence is available to guide therapy in Takayasu arteritis (TAK).

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

Summarise what we now know as a result of this study that we did not know before.

Tocilizumab therapy achieved 6 months complete remission in 70% of disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (DMARDs)-refractory TAK patients and compare subcutaneous and intravenous tocilizumab route.

HOW THIS STUDY MIGHT AFFECT RESEARCH, PRACTICE OR POLICY

Summarise the implications of this study.

This study confirms that tocilizumab is effective in DMARDs-refractory TAK patients and compares the subcutaneous and intravenous formulations of tocilizumab for the first time.

Introduction

Takayasu arteritis (TAK) is a chronic inflammatory large-vessel vasculitis, predominantly affecting the aorta and its major branches.1 Vessel inflammation leads to wall thickening, fibrosis, stenosis and thrombus formation. TAK mostly affects women and many ethnic groups worldwide. Morbidity from TAK itself is substantial: up to 50% of TAK patients will relapse and experience a vascular complication within 10 years of initial diagnosis.2 The mortality rate in TAK patients is 2.7 times higher as compared with age-matched and sex-matched healthy controls.3 In parallel, treatment strategies are not well recognised. The place of glucocorticoids, disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs), and more recently biological targeted therapies, is still not determined.

The first-line therapy consists of glucocorticoids which often results in substantial toxicity. In addition, approximately one-half of TAK patients have steroid-resistant or relapsing disease, and the addition of other immunosuppressive agents is frequently needed to achieve remission and to reduce the glucocorticoid dose. Methotrexate, azathioprine, leflunomide or mycophenolate mofetil are conventional synthetic DMARDs (csDMARDs) usually used in TAK initial management.4–7 However, in a setting where few high-quality evidence is available to guide pharmacotherapy in TAK4 increasing data have reported the benefit of biological-targeted therapies8–23.

Recently, the effectiveness of biological therapies such as inhibitors of tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and IL-6 receptor (tocilizumab) in TAK patients who were refractory to other immunosuppressive therapies has been reported in several studies.8–26 We have recently reported a French nationwide registry that showed quite similar effectiveness of TNF-α antagonists and tocilizumab, with acceptable safety profile and significant steroid sparing effect27. A recent phase III, randomised, double blind, placebo-controlled trial of tocilizumab versus placebo in TAK failed to reach its primary intention-to-treat analysis, but tocilizumab was favoured in a secondary per-protocol analysis regarding TAK time to relapse.28 Besides its role on refractory patients, intravenous tocilizumab was also evaluated in treatment-naïve TAK patients in the French TOCITAKA prospective multicentre open-labelled trial, showing 6-month remission rates of 80%, of whom 54% were in glucocorticoid-free remission at 6 months.29 So far, data regarding the effectiveness and safety of intravenous versus subcutaneous (SC) use of tocilizumab in TAK are currently lacking.

In this large multicentre study, we compared the effectiveness and safety of tocilizumab intravenous versus SC in 109 TAK patients. We assessed long-term outcomes and predictive factors for response, relapse and revascularisation in these patients.

Methods

Patients and data collection

We conducted a retrospective multicentre study in referral centres from France, Italy, Spain, Armenia, Israel, Japan, Tunisia and Russia regarding biological-targeted therapies in TAK, with the data collection period corresponding to January 2017 to September 2019 . All physicians were asked to fulfil standardised anonymised excel form for all patients which were followed in their centre and which have been treated by any biological targeted therapy. From this registry, only patients with active TAK that were treated with tocilizumab (intravenous and/or SC forms) were extracted and analysed in this study. All patients fulfilled TAK ACR and/or Ishikawa criteria modified by Sharma.1 The patients’ age, sex, associated diseases, TAK duration and vascular extension (Numano scale), clinical, laboratory and imaging data, as well as treatments were analysed at baseline (ie, tocilizumab initiation), at 6 months, at each new treatment regimen initiation and at the last available visit. Glucocorticoids dosages were analysed at the initiation of each new treatment regimen and during the follow-up. Routine laboratory indicators of disease activity, including C reactive protein (CRP) levels, were collected. The different lines of tocilizumab therapies used in intravenous and SC forms were separately analysed and pooled for the statistical analysis.

Disease activity and treatment response definitions

Disease activity was defined according to the NIH criteria as previously defined.27 Briefly, disease is active if NIH score is of two or superior and in remission otherwise. Treatment response was initially considered using NIH scale <2; because of usual decrease of CRP on tocilizumab, the prednisone dose decrease and sparing effect were also considered in complete response definition, determined by the combination of NIH scale <2 and prednisone <7.5 mg/day by 6 months. Relapse was defined as active disease after a remission period and with the need for treatment regimen change. Tocilizumab failure was considered in the case of non-response (persistent NIH score equal or superior to 2,27 treatment changes, ischaemic vascular event and/or the need for vascular intervention during the tocilizumab course. Steroid dependence was defined as a prednisone dose ≥20 mg/day before each new therapeutic line.

Statistical analysis

For descriptive analyses, categorical variables are reported with counts (per cent) and quantitative variables with median (IQR) (ranges). Six-month response was analysed as a binary endpoint. Time to treatment failure was defined as the time between the date of tocilizumab initiation and the date of treatment discontinuation due adverse event, inefficacy, relapse, death, whichever occurred first. Treatment discontinuation due to remission was treated as informative censoring (competing risk); treatment discontinuation due to lost to follow-up or pregnancy was treated as non-informative censoring. Multiple imputation by chained equations was used to handle missing data on endpoint and covariates for 6-month response and covariates for relapse risk analysis. The multivariable models were selected using a majority approach combined with Wald testing (variable selection procedure using Akaike’s information criterion performed on each imputed data set, variables being selected on more than 50% of imputed datasets being considered for the final model then confirmed for inclusion in the final model using Wald testing). These results are presented either as OR or HR along with their 95% CI. Sensitivity analyses were performed on complete cases, with variable selection using Akaike’s information criterion, yielding consistent results for the different outcomes. All statistical tests were two sided at a 5%-significance level. Analyses were performed on R statistical platform, V.3.5.3.30

Results

Characteristics of Tak patients on tocilizumab

A total of 109 TAK patients received tocilizumab therapy and were included in this study. Among them, 91 and 18 patients received intravenous and SC tocilizumab, respectively. Intravenous tocilizumab was used initially at 8 mg/kg/monthly and SC at 162 mg/week. Patients’ characteristics and TAK-specific features on the initiation of tocilizumab are summarised in tables 1 and 2. Overall, the demographic and comorbidity profile, TAK-specific features, and treatments used concurrently with tocilizumab were similar between groups. Tocilizumab was used as first-line therapy in 25 (27%) and 4 (22%) cases of intravenous and SC routes, respectively. In the remaining patients, the median number of csDMARDs before tocilizumab was similar between groups, but patients using SC route had significantly higher number of previous biological DMARDs than those on intravenous tocilizumab (p=0.039). Tocilizumab was prescribed along with a csDMARD in 51 (49.5%) patients.

Table 1.

Overall patient characteristics and previous treatments at baseline

| Variables | Total (n=109) | IV (n=91) | SC (n=18) | P |

| Female sex | 93 (85.3) | 78 (85.7) | 15 (83.3) | 0.73 |

| Age at inclusion, years | 30 (23;42)(7 ; 62) | 31 (24;42)(7 ; 62) | 27 (19;34)(14 ; 52) | 0.16 |

| ≥ 30 years | 54 (50) | 47 (53) | 7 (39) | |

| Smoking | 16 (15) | 11 (12) | 5 (28) | 0.14 |

| Arterial hypertension | 19 (17) | 16 (18) | 3 (17) | 1 |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 7 (6) | 5 (5) | 2 (11) | 0.33 |

| Diabetes | 3 (3) | 3 (3) | 0 (0) | 1 |

| Other systemic disease | 0.37 | |||

| None | 93 (85) | 77 (85) | 16 (89) | |

| Crohn’s disease | 4 (4) | 4 (4) | 0 (0) | |

| Granulomatosis with polyangiitis | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (6) | |

| Sarcoidosis | 5 (5) | 5 (5) | 0 (0) | |

| Sjogren syndrome | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | |

| Spondyloarthritis | 5 (5) | 4 (4) | 1 (6) | |

| csDMARDs-naive | 29 (27) | 25 (27) | 4 (22) | 0.78 |

| Previous csDMARDs | 0.49 | |||

| Azathioprine | 10 (12.5) | 9 (13.6) | 1 (7.1) | |

| Cyclophosphamide | 5 (6.2) | 5 (7.6) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Mycophenolate mofetil | 2 (2.5) | 1 (1.5) | 1 (7.1) | |

| Methotrexate | 62 (77.5) | 50 (75.8) | 12 (85.7) | |

| No. previous csDMARDs | 1 (0;1)(0 ; 4) | 1 (0;1)(0 ; 4) | 1 (1;2)(0 ; 3) | 0.23 |

| 0 | 29 (26.6) | 25 (27.5) | 4 (22.2) | |

| 1 | 53 (48.6) | 46 (50.5) | 7 (38.9) | |

| 2 | 24 (22.0) | 18 (19.8) | 6 (33.3) | |

| 3 | 2 (1.8) | 1 (1.1) | 1 (5.6) | |

| 4 | 1 (0.9) | 1 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) | |

| No. previous csDMARDs in non-naive | 1 (1;2)(1 ; 4) | 1 (1;2)(1 ; 4) | 2 (1;2)(1 ; 3) | 0.15 |

| No. bDMARDs prior to Tocilizumab | 0.039 | |||

| 0 | 74 (68) | 65 (71) | 9 (50) | |

| 1 | 23 (21) | 19 (21) | 4 (22) | |

| 2 | 9 (8) | 5 (5) | 4 (22) | |

| 3 | 2 (2) | 2 (2) | 0 (0) | |

| 4 | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (6) |

bDMARDs, biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs; csDMARDs, conventional synthetic DMARDs; IV, intravenous; SC, subcutaneous.

Table 2.

Overall TAK features and concomitant treatments at baseline

| Variables | Total (n=109) | IV (n=91) | SC (n=18) | P value |

| Disease activity | ||||

| Vascular signs | 78 (73.6) | 68 (76.4) | 10 (58.8) | 0.14 |

| Systemic signs | 45 (45.5) | 37 (43.5) | 8 (57.1) | 0.39 |

| Numano classification | 0.60 | |||

| I | 12 (11) | 9 (10) | 3 (17) | |

| II | 10 (9) | 10 (11) | 0 (0) | |

| IIa | 13 (12) | 12 (14) | 1 (6) | |

| IIa P(+) | 2 (2) | 2 (2) | 0 (0) | |

| IIb | 17 (16) | 12 (14) | 5 (28) | |

| III | 7 (7) | 6 (7) | 1 (6) | |

| IV | 4 (4) | 3 (3) | 1 (6) | |

| V | 40 (38) | 33 (38) | 7 (39) | |

| Va | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | |

| Vessel activity on imaging | 96 (93.2) | 80 (93.0) | 16 (94.1) | |

| NIH scale | 3 (2 to 3) (0 to 4) | 3 (2 to 3) (1 to 4) | 3 (2 to 3) (0 to 4) | 0.89 |

| NIH scale ≥3 | 68 (63.0) | 56 (62.2) | 12 (66.7) | 0.79 |

| CRP | 23 (11;41) (0 ; 191) | 21 (10;40) (0 ; 150) | 35 (21;57) (1 ; 191) | 0.16 |

| CRP ≥20 mg/L | 64 (61) | 50 (57) | 14 (78) | 0.11 |

| Concomitant treatments | ||||

| Prednisone, n (%) | 101 (95) | 83 (94) | 18 (100) | 0.59 |

| Dose, mg/day | 20 (10;40) (3 ; 90) | 20 (11;40) (3 ; 90) | 28 (6;45) (5 ; 50) | 0.50 |

| Dose ≥20 mg/day, n (%) | 64 (60) | 54 (61) | 10 (56) | 0.79 |

| First line biologics | 29 (27) | 25 (27) | 4 (22) | 0.78 |

| Associated csDMARDs | 0.85 | |||

| None | 51 (49.5) | 44 (50.0) | 7 (46.7) | |

| Azathioprine | 3 (2.9) | 3 (3.4) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Mycophenolate mofetil | 4 (3.9) | 3 (3.4) | 1 (6.7) | |

| Methotrexate | 42 (40.8) | 35 (39.8) | 7 (46.7) | |

| Sirolimus | 1 (1.0) | 1 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Salazopyrine | 1 (1.0) | 1 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Median time from TAK diagnosis, years | 2.2 (0.9;6.3) (0.0 ; 31.3) | 2.1 (0.9;6.3) (0.0 ; 24.1) | 3.4 (0.8;8.0) (0.0 ; 31.3) | 0.70 |

CRP, C reactive protein; csDMARDs, conventional synthetic DMARDs; IV, intravenous; SC, subcutaneous; TAK, Takayasu arteritis.

Effectiveness of tocilizumab

A complete response (NIH <2 with less than 7.5 mg/day of prednisone) at 6 months was evidenced in 69% of TAK patients, of whom 57 (70%) and 11 (69%) patients were on intravenous and SC tocilizumab, respectively (p=0.95). The factors associated with complete response to tocilizumab at 6 months in univariate analysis were age <30 years, time between TAK diagnosis and tocilizumab initiation, absence of vascular signs and baseline prednisone dose <20 mg/day (table 3). In multivariate analysis, only age <30 years (OR 2.85, 95% CI 1.14 to 7.12; p=0.027) and time between TAK diagnosis and tocilizumab initiation (OR 1.18, 95% CI 1.02 to 1.36; p=0.034) were significantly associated with complete response at 6 months.

Table 3.

Univariate analysis of factors associated with complete response at 6 months

| Variables | N* | No response (%)* | OR (95% CI) | P value |

| No of patients | 98 | 68 (69.4) | ||

| Age ≥30 years | ||||

| No | 48 | 28 (58.3) | 1 | |

| Yes | 48 | 38 (79.2) | 2.55 (1.06 to −6.10) | 0.036 |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 14 | 13 (92.9) | 1 | |

| Female | 84 | 55 (65.5) | 0.15 (0.018 to −1.22) | 0.076 |

| Underlying disease | ||||

| None | 83 | 56 (67.5) | 1 | |

| Crohn/spondyloarthritis | 9 | 8 (88.9) | 4.16 (0.48 to −35.8) | 0.19 |

| Sarcoidosis/other | 6 | 4 (66.7) | 1.26 (0.22 to −7.19) | 0.79 |

| Smoking | ||||

| No | 83 | 55 (66.3) | 1 | |

| Yes | 15 | 13 (86.7) | 3.36 (0.68 to −16.5) | 0.13 |

| Arterial hypertension | ||||

| No | 81 | 55 (67.9) | 1 | |

| Yes | 17 | 13 (76.5) | 1.52 (0.45 to −5.13) | 0.49 |

| Dyslipidaemia† | 0.17 | |||

| No | 92 | 62 (67.4) | ||

| Yes | 6 | 6 (100) | ||

| Diabetes | ||||

| No | 95 | 67 (70.5) | 1 | |

| Yes | 3 | 1 (33.3) | 0.22 (0.019 to −2.65) | 0.23 |

| DMARDs-CS naïve | ||||

| No | 73 | 53 (72.6) | 1 | |

| Yes | 25 | 15 (60) | 0.55 (0.21 to −1.41) | 0.21 |

| Time between TA diagnosis and tocilizumab (years) | 97 | – | 1.16 (1.01 to −1.33) | 0.040 |

| Numano | ||||

| No | 56 | 39 (69.6) | 1 | |

| Yes | 39 | 27 (69.2) | 0.94 (0.39 to −2.27) | 0.88 |

| Numano - Supra-aortic trunks | ||||

| No | 11 | 10 (90.9) | 1 | |

| Yes | 84 | 56 (66.7) | 0.23 (0.029 to −1.86) | 0.17 |

| Numano—thoracic aorta | ||||

| No | 15 | 12 (80) | 1 | |

| Yes | 80 | 54 (67.5) | 0.63 (0.17 to −2.42) | 0.50 |

| Numano—abdominal aorta | ||||

| No | 49 | 33 (67.3) | 1 | |

| Yes | 46 | 33 (71.7) | 1.18 (0.49 to −2.85) | 0.71 |

| Vascular signs | ||||

| No | 25 | 22 (88) | 1 | |

| Yes | 70 | 44 (62.9) | 0.30 (0.09 to −0.97) | 0.044 |

| Systemic signs | ||||

| No | 51 | 36 (70.6) | 1 | |

| Yes | 38 | 26 (68.4) | 0.90 (0.35 to −2.31) | 0.83 |

| Vessel activity on imaging† | 0.17 | |||

| No | 6 | 6 (100) | ||

| Yes | 87 | 59 (67.8) | ||

| NIH ≥3 | ||||

| No | 36 | 29 (80.6) | 1 | |

| Yes | 61 | 38 (62.3) | 0.40 (0.15 to −1.07) | 0.068 |

| CRP ≥20 mg/L | ||||

| No | 37 | 28 (75.7) | 1 | |

| Yes | 57 | 38 (66.7) | 0.73 (0.29 to −1.82) | 0.49 |

| Baseline prednisone ≥20 mg | ||||

| No | 39 | 32 (82.1) | 1 | |

| Yes | 58 | 36 (62.1) | 0.36 (0.13 to −0.96) | 0.041 |

| Associated DMARDs | ||||

| No | 51 | 34 (66.7) | 1 | |

| Yes | 47 | 34 (72.3) | 1.29 (0.55 to −3.03) | 0.55 |

| Tocilizumab route | ||||

| IV | 82 | 57 (69.5) | 1 | |

| SC | 16 | 11 (68.8) | 1.04 (0.32 to −3.35) | 0.95 |

*Complete cases counts.

†Fisher’s exact test on complete cases.

CRP, C reactive protein; DMARDs, disease-modifying antirheumatic drug; DMARDs-CS, conventional synthetic DMARDs; IV, intravenous; SC, subcutaneous.

Relapses

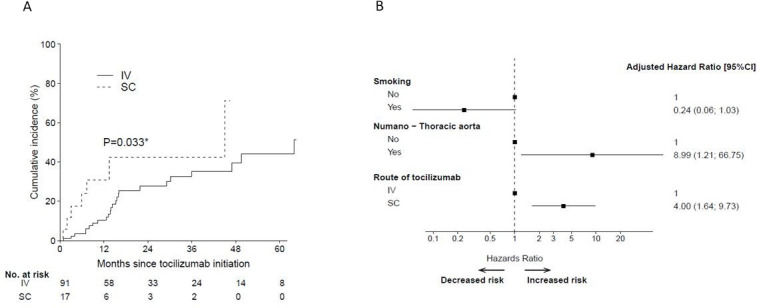

During the median follow-up of 30.1 months (0.4; 105.8) and 10.8 (0.1; 46.4) (p<0.0001) in patients who received tocilizumab in intravenous and SC forms, respectively, the risk of relapse was significantly higher in TAK patients on SC tocilizumab (HR 2.55, 95% CI 1.08 to 6.02; p=0.033) (figure 1A,B). In univariate analysis, only SC route was significantly associated with higher relapse rates as compared with intravenous one (table 4). The overall cumulative incidence of relapse at 6 months in TAK patients was at 6.8% (95% CI 3.0% to 12.7), with 3.4% (95% CI 0.9% to 8.9%) for patients on intravenous tocilizumab vs 24% (95% CI 7.0% to 46.4%) for those receiving SC tocilizumab, and, at 12 months 13.7% (95% CI 7.6% to 21.5) overall, 10.3% (95% CI 4.8% to 18.4%) for those on intravenous tocilizumab vs 30.9% (95% CI 10.5% to 54.2%) for patients receiving SC tocilizumab (table 5) (with 79% estimated with 12 months or more follow-up in the intravenous group and 44% in the SC group).

Figure 1.

(A) The cumulative incidence of relapse by route of administration. (B) HR of risk of relapse by route of administration. IV, intravenous; SC, subcutaneous. *=p<0.05.

Table 4.

Univariate analysis of factors associated with relapse in TAK patients

| Variable | Nevt/N | HR (95% CI) | P value |

| No relapses/no lines | 32/108 | ||

| Age ≥30 years | |||

| 0 | 14/52 | 1 | |

| 1 | 17/54 | 1.05 (0.52 to 2.14) | 0.89 |

| Female sex | |||

| 0 | 5/16 | 1 | |

| 1 | 27/92 | 0.88 (0.33 to 2.30) | 0.79 |

| Underlying disease | |||

| None | 26/92 | 1 | |

| Crohn/spondyloarthritis | 3/9 | 0.82 (0.24 to 2.75) | 0.75 |

| Sarcoidosis/other | 3/7 | 0.98 (0.29 to 3.26) | 0.97 |

| Smoking | |||

| 0 | 30/92 | 1 | |

| 1 | 2/16 | 0.30 (0.07 to 1.24) | 0.097 |

| Hypertension | |||

| 0 | 26/89 | 1 | |

| 1 | 6/19 | 0.82 (0.33 to 2.01) | 0.66 |

| Dyslipidaemia | |||

| 0 | 29/102 | 1 | |

| 1 | 3/6 | 1.12 (0.34 to 3.68) | 0.86 |

| Diabetes | |||

| 0 | 31/105 | 1 | |

| 1 | 1/3 | 2.08 (0.28 to 15.5) | 0.48 |

| DMARDs-glucocoricoids naive | |||

| 0 | 24/79 | 1 | |

| 1 | 8/29 | 1.40 (0.63 to 3.13) | 0.41 |

| Time between TA diagnosis and biotherapy (years) | 0.96 (0.89 to 1.04) | 0.36 | |

| Numano | |||

| I–III | 16/60 | 1 | |

| IV–V | 16/45 | 1.32 (0.66 to 2.65) | 0.43 |

| Numano—supra aortic trunks | |||

| 0 | 2/11 | 1 | |

| 1 | 30/94 | 1.70 (0.41 to 7.15) | 0.47 |

| Numano—thoracic aorta | |||

| 0 | 1/16 | 1 | |

| 1 | 31/89 | 7.51 (1.02 to 55.2) | 0.048 |

| Numano—abdominal aorta | |||

| 0 | 14/53 | 1 | |

| 1 | 18/52 | 1.33 (0.66 to 2.67) | 0.43 |

| Vascular signs | |||

| 0 | 8/27 | 1 | |

| 1 | 24/78 | 1.42 (0.63 to 3.17) | 0.39 |

| Systemic signs | |||

| 0 | 16/54 | 1 | |

| 1 | 14/44 | 1.21 (0.59 to 2.49) | 0.60 |

| Vessel activity on imaging | |||

| 0 | 1/7 | 1 | |

| 1 | 31/95 | 1.95 (0.27 to 14.4) | 0.51 |

| NIH scale ≥3 | |||

| 0 | 8/40 | 1 | |

| 1 | 24/67 | 2.10 (0.94 to 4.70) | 0.070 |

| CRP ≥20 mg/L | |||

| 0 | 12/41 | 1 | |

| 1 | 19/63 | 1.27 (0.61 to 2.61) | 0.52 |

| Prednisone ≥20 mg/day | |||

| 0 | 16/42 | 1 | |

| 1 | 16/63 | 0.85 (0.42 to 1.70) | 0.64 |

| Associated immunosuppressant/DMARDs | |||

| 0 | 15/56 | 1 | |

| 1 | 17/52 | 0.96 (0.47 to 1.94) | 0.90 |

| Route of administration tocilizumab | |||

| Tocilizimab Intravenous form | 25/91 | 1 | |

| Tocilizumab subcutaneous form | 7/17 | 2.55 (1.08 to 6.02) | 0.033 |

CRP, C reactive protein; DMARDs, disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs; TAK, Takayasu arteritis.

Table 5.

Overall cumulative incidences of relapse, treatment failure and revascularisation in TAK patients and according IV and SC route

| All (n=109) | IV (n=91) | SC (n=18) | |

| Relapse (%) | |||

| 12 months | 13.7 (7.6 ; 21.5) | 10.3 (4.8; 18.4) | 30.9 (10.5; 54.2) |

| 36 months | 36.8 (25 ; 48.7) | 35.2 (22.6; 48.1) | 42.4 (14.2 ; 68.6) |

| Treatment failure (%) | |||

| 12 months | 12.6 (6.8; 20.2) | 10.0 (4.6; 17.8) | 25.7 (7.4; 49.2) |

| 36 months | 28.9 (18.6; 40.0) | 27.6 (16.9; 39.3) | 25.7 (7.4; 49.2) |

| Revascularisation (%) | |||

| 12 months | 4.5 (1.5; 10.4) | 3.9 (1.0; 10.1) | 8.3 (0.4; 32.3) |

| 36 months | 15.7 (7.7; 26.4) | 16.0 (7.5; 27.3) | 8.3 (0.4 ; 32.3) |

| 60 months | 15.7 (7.7; 26.4) | 16.0 (7.5; 27.3) | 8.3 (0.4 ; 32.3) |

Cumulative incidence is presented as percentage along with its 95% CI.

IV, intravenous; SC, subcutaneous; TAK, Takayasu arteritis.

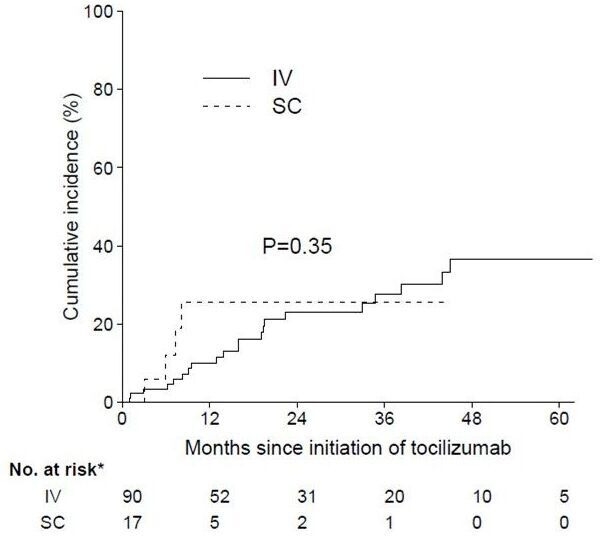

Time to treatment failure

The cumulative incidence of treatment discontinuation by route of administration is displayed in figure 2, and was not significantly different between groups (HR 1.52, 95% CI 0.51 to 4.50; p=0.35). Although smoking was associated with treatment discontinuation in univariate analysis (p=0.009), no independent factor was found in multivariate analysis.

Figure 2.

The cumulative incidence of treatment doiscontinuation by route of administration. IV, intravenous; SC, subcutaneous.

The revascularisation-free survival was not significantly different regarding intravenous and SC tocilizumab (table 5), and there was no factor significantly associated with the risk of revascularisation (data not shown).

Safety

Overall, adverse events occurred in 16 (15%) TAK patients during tocilizumab treatment. They included mainly viral infections, non-severe infections and mild hepatitis. Adverse events occurred in 14 (15%) patients on intravenous route (infusion reaction=5, bacterial infections=4, mild cytolysis=2, zoster and herpes reactivation=2 and neutropenia with infection=1) and in 2 (11%) on SC tocilizumab (mild hepatitis and zooster infection). Serious adverse events leading to treatment discontinuation occurred in one case on intravenous tocilizumab (ie, neutropenia with infection). There was no drug-related death.

Discussion

In this study, we confirm that tocilizumab is effective in TAK, with complete remission being achieving by 70% of DMARDs-refractory TAK patients at 6 months. Tocilizumab had a significant steroid-sparing effect and we did not evidence specific safety signal. We define high-risk patients for relapse according to a multivariate model.

Monoclonal antibodies have been increasingly employed in the management of large-vessel vasculitis. In giant cell arteritis (GCA), the other prototype of large vessel vasculitis, tocilizumab has been shown to be effective and safe in both clinical trial24 and real-life settings.26 For TAK, a recent meta-analysis endorsed the benefits of both TNF inhibitors and tocilizumab, although a high degree of heterogeneity was noted among observational studies.4 Looking specifically at pooled data from tocilizumab, it was able to induce at least a partial response in 87% of patients, being also effective in angiographic stabilisation and daily corticosteroid doses reduction. Although the single randomised controlled trial to date (ie, TAKT study) was felt to be underpowered, SC tocilizumab was statistically superior to placebo in the per protocol analysis for time-to-relapse reduction in csDMARD-refractory TAK patients.28 Its use has proven promising in other settings as well, with a recent open-label trial that evaluated tocilizumab in TAK treatment-naïve patients revealing its efficacy in inducing remission and making these patients corticosteroid-free within 6 months.29 All together, these data have led to international guidelines consensus in recommending tocilizumab for patients with relapsing or refractory disease despite first-line DMARDs. In our study, we confirmed the effectiveness of tocilizumab in TAK, by demonstrating a 6-month 70% rate of complete response, regardless of the route of administration. About a half of our patients were on combined therapy with other csDMARD, which did not seem to affect tocilizumab therapeutic response. Although tocilizumab either in combination or monotherapy has been proven effective in refractory patients, studies evaluating the effect of concomitant csDMARD use on retention rates of biological agents in TAK have yielded conflicting results.11 27 Data regarding DMARDs combination in TAK remain very scarce and variably reported in studies,4 precluding formal recommendations to be formulated.

Despite its overall clinical effectiveness in TAK, the direct effects of tocilizumab on vascular inflammation—and therefore its ability to prevent complications—are not yet fully known. This is well illustrated in studies designed to assess vascular inflammation by imaging techniques in GCA with large-vessel involvement, in which persistent aortic inflammation was documented in a non-negligible proportion of patients on tocilizumab.31 32 In TAK, case reports have been documenting disease progression and vascular complications (eg, aortic ulceration) in patients receiving tocilizumab.14–16 These patients’ management should rely on combined clinical assessments and serial imaging studies, given the expected suppression of serum inflammatory markers (eg, CRP) on tocilizumab, regardless of therapeutic response. In the post hoc analysis of TAKT trial, about 40% of TAK patients on tocilizumab experienced wall thickness progression in CT angiography within 96 weeks of treatment initiation.33 The occurrence of such vascular complications may require surgical treatment, which is extremely challenging in TAK. Despite largely based on retrospective series, current recommendations are consistent regarding optimal clinical control on surgical intervention, underlining the role of immunosuppressants in achieving favourable outcomes. Here, we describe the overall revascularisation rate in TAK patients on tocilizumab as roughly 15% at 36 months, with no significant role for route of administration in this outcome. Although we did not identify any factors associated with revascularisation, elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate at diagnosis has been associated with the need for future intervention.2 The preventive immunosuppressive benefit seems similar across biological DMARDs, as no difference in surgery requirement for TAK patients on either TNF inhibitors or tocilizumab have been documented.11 27 This topic, however, lacks further prospective and specific investigation.

Intravenous or SC formulations of tocilizumab are label approved for some immune-mediated diseases. Among these, rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is the one with the most available data, where both SC and intravenous are comparable in terms of long-term efficacy and safety. In GCA, each of the available randomised controlled trials evaluated different routes of tocilizumab, but no comparative data between these have been published so far. The data comparing intravenous versus SC use of tocilizumab are mainly available in RA, and among 3448 patients with 2414 with TCZ-IV and 1034 with TCZ-SC, clinical disease activity and low disease activity was lower in TCZ-IV patients: 41.0% in TCZ-IV vs 49.1% in TCZ-SC (difference: 8.0%; bootstrap 95% CI 2.4%–12.4%).34 Although tocilizumab route did not influence the 6 month complete response rate in our study, relapse risk in SC group was significantly higher than in the intravenous one. Possible explanations could lie in the different pharmacokinetic properties of tocilizumab routes of administration. Although these differences do not pose clinical implications in RA, the SC route has lower bioavailability (ie, 79%) and longer time to reach steady-state maximum serum concentration (ie, 12 weeks vs right after the first intravenous dose), which may have a distinct impact on TAK.35 36 Also, possible lower compliance with SC treatment, as opposed to supervised intravenous infusions, may have contributed to a higher relapse risk following an adequate primary response. Antitocilizumab antibodies could be another argument, as SC route is more immunogenic, but few data are available on this issue.

As with immunosuppressive therapies in general, infectious adverse events are a common concern for tocilizumab. In line with our findings, infections have indeed been the most frequent adverse events in clinical trial settings for RA, GCA and TAK.8 12 16 26 35 However, in both the GiACTA (ie, SC tocilizumab in GCA) and TAKT trials, adverse event rates o n tocilizumab were not significantly different when compared with placebo arms, including infections.26 28 In TAKT longer-term open-label extension, serious adverse event rate was at 25% after a median follow-up of 108 weeks; however, all infections resolved without sequelae, there were no study withdrawals due to adverse events, and no deaths were documented, a long-term safety profile that is comparable to the one seen in RA.33 There were no new or unexpected safety issues in both TAKT and GiACTA open-label extensions.24 25 In our cohort, the overall adverse event rate of 15% lies within the range of pooled data from meta-analysed observational studies evaluating TAK patients on tocilizumab (ie, 95% CI 12% to 35%).4 Moreover, treatment discontinuation due to serious adverse event occurred in only one case on intravenous tocilizumab, and there was no drug-related death. Regarding the safety of different tocilizumab formulations, comparative data are available from a 97-week trial in RA, where adverse event rates were similar between SC and intravenous arms.35 The sole exception was site injection reactions, more frequent in those receiving SC route. Notably, the overall safety profile remained stable throughout the study period even for patients switching routes, whereas infection rates decreased over time. This is also consistent with the frequency and side effects profile that we found comparing tocilizumab routes, favouring the safe use of the SC formulation within the management of TAK patients.

Our study has several limitations, such as its retrospective design and the fact that the choices of tocilizumab formulation and csDMARDs combination were at treating physicians’ discretion. Since there was no formal sample size calculation, the available number of patients in the SC arm may have been insufficient to identify more subtle differences between the groups, especially for multivariate analyses. Also, as patients’ compliance to SC tocilizumab could not be weighed, this bias should be recognised when analysing relapse rates.

In this international multicentre cohort, the effectiveness and safety profile of SC and intravenous formulations of tocilizumab are reported for the first time. The 6-month complete response rates and safety profile were similar between groups, offering a promising posological possibility for TAK patients and their treating physicians. These data should be further validated in clinical trials, ideally with proper pharmacokinetic and compliance surveillance.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Takayasu group for their participation in this paper.

Footnotes

Correction notice: This article has been corrected since it was first published online. The author Corrado Campochiaro was incorrectly listed as Corrado Campochiaro. The author Alberto Lo Gullo was incorrectly listed as Alberto Logullo.

Contributors: Am is the guarantor of this manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as online supplemental information.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

References

- 1. Kerr GS, Hallahan CW, Giordano J, et al. Takayasu arteritis. Ann Intern Med 1994;120:919–29. 10.7326/0003-4819-120-11-199406010-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Comarmond C, Biard L, Lambert M, et al. Long-term outcomes and Prognostic factors of complications in Takayasu arteritis: A multicenter study of 318 patients. Circulation 2017;136:1114–22. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.027094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mirouse A, Biard L, Comarmond C, et al. Overall survival and mortality risk factors in Takayasu's arteritis: A multicenter study of 318 patients. J Autoimmun 2019;96:35–9.:S0896-8411(18)30368-8. 10.1016/j.jaut.2018.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Misra DP, Rathore U, Patro P, et al. Disease-Modifying anti-rheumatic drugs for the management of Takayasu arteritis-a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Rheumatol 2021;40:4391–416. 10.1007/s10067-021-05743-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hoffman GS, Leavitt RY, Kerr GS, et al. Treatment of glucocorticoid-resistant or Relapsing Takayasu arteritis with methotrexate. Arthritis Rheum 1994;37:578–82. 10.1002/art.1780370420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Numano F, Okawara M, Inomata H, et al. Takayasu's arteritis. Lancet 2000;356:1023–5. 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02701-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ogino H, Matsuda H, Minatoya K, et al. Overview of late outcome of medical and surgical treatment for Takayasu arteritis. Circulation 2008;118:2738–47. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.759589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Abisror N, Mekinian A, Lavigne C, et al. Tocilizumab in refractory Takayasu arteritis: A case series and updated literature review. Autoimmunity Reviews 2013;12:1143–9. 10.1016/j.autrev.2013.06.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bravo Mancheño B, Perin F, Guez Vázquez Del Rey MDMR, et al. Successful Tocilizumab treatment in a child with refractory Takayasu arteritis. Pediatrics 2012;130:e1720–4. 10.1542/peds.2012-1384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bredemeier M, Rocha CM, Barbosa MV, et al. One-year clinical and radiological evolution of a patient with refractory Takayasu's arteritis under treatment with Tocilizumab. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2012;30(1 Suppl 70):S98–100. 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2020.01.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Comarmond C, Plaisier E, Dahan K, et al. Anti TNF-alpha in refractory Takayasu's arteritis: cases series and review of the literature. Autoimmun Rev 2012;11:678–84. 10.1016/j.autrev.2011.11.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. de Kruif MD, van Gorp ECM, Bel EH, et al. Streptococcal lung abscesses from a dental focus following Tocilizumab: a case report. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2012;30:951–3. 10.1093/rheumatology/key015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Goel R, Danda D, Kumar S, et al. Rapid control of disease activity by Tocilizumab in 10 'difficult-to-treat' cases of Takayasu arteritis. Int J Rheum Dis 2013;16:754–61. 10.1111/1756-185X.12220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hoffman GS, Merkel PA, Brasington RD, et al. Anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy in patients with difficult to treat Takayasu arteritis. Arthritis Rheum 2004;50:2296–304. 10.1002/art.20300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Maffei SF, Di Renzo M. Refractory Takayasu arteritis successfully treated with Infliximab. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2009;13:63–5. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-215459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mekinian A, Neel A, Sibilia J, et al. Efficacy and tolerance of Infliximab in refractory Takayasu arteritis: French Multicentre study. Rheumatology 2012;51:882–6. 10.1093/rheumatology/ker380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Molloy ES, Langford CA, Clark TM, et al. Anti-tumour necrosis factor therapy in patients with refractory Takayasu arteritis: long-term follow-up. 2008;67(11):1567-9. Ann Rheum Dis 2008;67:1567–9. 10.1136/ard.2008.093260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Nakaoka Y, Higuchi K, Arita Y, et al. Tocilizumab for the treatment of patients with refractory Takayasu arteritis. 2013;54(6):405-11. Int Heart J 2013;54:405–11. 10.1536/ihj.54.405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Nishimoto N, Nakahara H, Yoshio-Hoshino N, et al. Successful treatment of a patient with Takayasu arteritis using a Humanized anti-Interleukin-6 receptor antibody. Arthritis Rheum 2008;58:1197–200. 10.1002/art.23373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Nunes G, Neves FS, Melo FM, et al. Takayasu arteritis: anti-TNF therapy in a Brazilian setting. Rev Bras Reumatol 2010;50:291–8. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.014321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Osman M, Aaron S, Noga M, et al. Takayasu's arteritis progression on anti-TNF Biologics: a case series. Clin Rheumatol 2011;30:703–6. 10.1007/s10067-010-1658-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Salvarani C, Magnani L, Catanoso MG. Rescue treatment with Tocilizumab for Takayasu arteritis resistant to TNF-alpha blockers. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2012;30:S90–3. 10.1080/17425247.2019.1618828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Schmidt J, Kermani TA, Kirstin Bacani A, et al. Tumor necrosis factor inhibitors in patients with Takayasu arteritis: experience from a referral center with long-term followup. Arthritis Care Res 2012;64:n. 10.1002/acr.21636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Seitz M, Reichenbach S, Bonel HM, et al. Rapid induction of remission in large vessel vasculitis by IL-6 blockade. A case series. Swiss Med Wkly 2011;141:w13156. 10.4414/smw.2011.13156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Tombetti E, Franchini S, Papa M, et al. Treatment of refractory Takayasu arteritis with Tocilizumab: 7 Italian patients from a single referral center. J Rheumatol 2013;40:2047–51. 10.3899/jrheum.130536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Unizony S, Arias-Urdaneta L, Miloslavsky E, et al. Tocilizumab for the treatment of large-vessel vasculitis (giant cell arteritis, Takayasu arteritis) and Polymyalgia Rheumatica. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2012;64:1720–9. 10.1002/acr.21750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mekinian A, Comarmond C, Resche-Rigon M, et al. Efficacy of biological-targeted treatments in Takayasu arteritis: multicenter, retrospective study of 49 patients. Circulation 2015;132:1693–700. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.014321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Nakaoka Y, Isobe M, Takei S, et al. Efficacy and safety of Tocilizumab in patients with refractory Takayasu arteritis: results from a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial in Japan (the TAKT study). Ann Rheum Dis 2018;77:348–54. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2017-211878 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Mekinian A, Saadoun D, Vicaut E, et al. Tocilizumab in treatment-Naïve patients with Takayasu arteritis: TOCITAKA French prospective multicenter open-labeled trial. Arthritis Res Ther 2020;22:218. 10.1186/s13075-020-02311-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Therneau T GP. Modeling survival data: extending the Cox model statistics for biology and health. Springer, 2000: 189. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Reichenbach S, Adler S, Bonel H, et al. Magnetic resonance angiography in giant cell arteritis: results of a randomized controlled trial of Tocilizumab in giant cell arteritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2018;57:982–6. 10.1093/rheumatology/key015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Quinn KA, Dashora H, Novakovich E, et al. Use of 18F-Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography to monitor Tocilizumab effect on vascular inflammation in giant cell arteritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2021;60:4384–9. 10.1093/rheumatology/keaa894 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Nakaoka Y, Yamashita K, Yamakido S. Long-term efficacy and safety of Tocilizumab in refractory Takayasu arteritis: final results of the randomized controlled phase 3 TAKT study. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2020;59:e48–9. 10.1093/rheumatology/keaa255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lauper K, Mongin D, Iannone F, et al. Comparative effectiveness of TNF inhibitors and Tocilizumab with and without conventional synthetic disease-modifying Antirheumatic drugs in a pan-European observational cohort of bio-Naïve patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2020;50:17–24. 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2019.06.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Burmester GR, Rubbert-Roth A, Cantagrel A, et al. Efficacy and safety of subcutaneous Tocilizumab versus intravenous Tocilizumab in combination with traditional Dmards in patients with RA at week 97 (SUMMACTA). Ann Rheum Dis 2016;75:68–74. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2015-207281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Scott LJ. Tocilizumab: A review in rheumatoid arthritis. Drugs 2017;77:1865–79. 10.1007/s40265-017-0829-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as online supplemental information.