Abstract

The study aimed to understand the relationship between the psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and turnover intention and the moderating role of employee engagement. Data were collected via a structured questionnaire through both hand deliveries of printed questionnaires and Google docs from 187 frontline employees in the Ghanaian public sector. The hypotheses were tested using structural equation modeling. There exists a positive and significant relationship between the COVID-19 pandemic and employee turnover intentions. Out of the three dimensions of work engagement, vigor had a significant negative moderating effect on the relationship between psychological impact and turnover intentions. This implies that the positive effect of the psychological impact of COVID-19 on turnover intentions is minimized, where employees have high levels of energy and mental resilience while working, thus their vigor is high rather than low. The study contributes to literature on employee work engagement by using the Job demands-resources model to unravel the specific dimension of employee engagement that can minimize the negative impact of COVID-19 on employees’ turnover intention in the public sector in a developing country.

Keywords: COVID-19, Job demands-resources model, Turnover intention, Employee engagement

1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has wreaked severe damage on governments, economies, and businesses all over the world (Du et al., 2023; Takyi et al., 2023; Usman et al., 2020; World Bank, 2020). The pandemic has had enormous consequences on people's livelihoods as most countries closed their borders, restricted the movement of people, and confined citizens within their homes for several weeks because of quarantine (Donthu & Gustafsson, 2020). Citizens around the globe, irrespective of their social norms and values were encouraged to observe social distance as individuals' mindfulness was found to have a positive and significant relationship with physical distancing (Kumar et al., 2021). In addition, the COVID-19 pandemic led to the closure of businesses, leading to unprecedented disruption in production, and commercial activities. As a result, organizations were confronted with issues relating to employee health, safety, and anxiety management (Jungmann & Witthöft, 2020; Obuobisa-Darko, 2022), supply chain (Aday & Aday, 2020), and workforce management (Wynne et al., 2021). Recent studies have indicated that individuals around the globe have experienced changes in their mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic (Morin et al., 2021; Williams et al., 2020).

While a burgeoning body of research has investigated the psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health (Serafini et al., 2020), employees and societies (e.g., Akat & Karataş, 2020; Morassaei et al., 2021; Passavanti et al., 2021; Tee et al., 2020), empirical evidence regarding the psychological impact of the pandemic on employee work performance outcomes such as work engagement and turnover intention remains scarce in the literature. To the best of our knowledge, this study is among the first attempts to examine the psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on employee work performance outcomes in the public sector within a developing country.

Psychological effects of COVID-19 have been highly associated with stress, anxiety, depression, frustration, and insomnia, among other mental health indicators (Morin et al., 2021; Pappa et al., 2020). According to Barbisch et al. (2015), the psychological reactions to infectious diseases could range from anxiety behavior to persistent feelings of hopelessness and depreciation, which could have negative consequences, including the intention to commit suicide (Thakur & Jain, 2020) or leave an organization. Previous studies that have examined the psychological impact of COVID-19 on healthcare professionals and employees, in general, reported a high incidence of anxiety, distress, depression and insomnia (Huang et al., 2020; Pappa et al., 2020). In the context of the present study, frontline public sector employees became vulnerable during the COVID-19 pandemic, which could have effects on their work engagement and turnover intention (ILO, 2022; World Bank, 2020).

Work engagement refers to the harnessing of organization members’ selves to their roles, where individuals employ and express themselves physically, cognitively, and emotionally during the performance of their job roles (Kahn, 1990). Engaged employees, in particular, put in a lot of effort to complete their assigned tasks because they identify with the task (Obuobisa-Darko, 2022; Nkansah et al., 2022; Coffie et al., 2023). Employees who are engaged with the work have a sense of enthusiastic and effective connection with their work, as they consider the work to be challenging and fulfilling rather than stressful and demanding (Bakker et al., 2014). They work with vigor, are dedicated and get absorbed in their work (Schaufeli & Taris, 2014).

On the other hand, turnover intention measures the intent of an employee to find a new job with another employer. It represents the voluntary withdrawal from the organization by an employee (De Croon et al., 2004) Thus, high levels of employee turnover may lead to a decline in the quality of services and, in turn, increase customers’ dissatisfaction with the services an organization provides (Trevor & Nyberg, 2008). The question then is, “Does employee engagement, specifically, vigor, absorption and dedication, make a difference in the relationship between the psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and turnover?” Drawing on the job demand-resources (JD-R) model, this study argues that excessive job demands, including anxiety and uncertainties during the COVID-19 era, could lead to sustained stress and work overload, which would cause one to wish to leave an organization. The JD-R model presumes that the health and well-being of the workforce are a product of a balance between positive (resources) and negative (demands) job characteristics (Schaufeli & Taris, 2014). While high job demands lead to strain, health impairment and anxiety (Magnavita, 2009), high resources result in increased motivation and enhanced work output. Thus, a lack of resources such as social support (Grey et al., 2020) and organizational support during COVID-19 may have a negative psychological impact (Labrague & De los Santos, 2020), which will lead to withdrawal behavior and a subsequent intention to leave the organization (Labrague & de Los Santos, 2021).

This study is very significant and contributes to both theory and practice. Theoretically, the study contributes to the JD-R model, which, relatively, has not been used much in studies that focus on psychological impacts within developing countries. Thus, since context matter in research (Arnould et al., 2006; Ruël & Van der Kaap, 2012), the study of the psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic in a developing country significantly bridges the knowledge gap. Again, although the pandemic situation has generally improved worldwide, its psychological impact is still an important issue that is worth investigating due to the effect it has on both individuals and organizations (Ahmad et al., 2023; Asif et al., 2022; Lange et al., 2023; Rodríguez-Martín et al., 2022). The findings will, therefore, help leaders adopt the appropriate strategies to manage the negative effect and leverage the positive to ensure organizational success in the current emerging economy.

2. Theoretical perspective and hypotheses

2.1. The job demands-resources model

Proposed by Demerouti et al. (2001), the JD-R model has been widely used to explain how specific workplace and organizational factors influence and affect employee well-being and performance (Bakker & Demerouti, 2017). According to the theory, employees’ job characteristics can be put into two main classifications: job demand and job resources (Bakker & Demerouti, 2007; Demerouti et al., 2001). Job demands refer to those parts of the job which involve continual efforts and therefore require a level of psychological and physiological effort (Bakker & Demerouti, 2017). It is those “aspects of the job that require sustained physical or mental effort and are therefore associated with certain physiological and psychological costs” (Demerouti et al., 2001; p. 501). Examples include high work pressure, an unfavorable physical environment, emotionally demanding interactions with clients, organizational constraints, and workload perceptions (Bakker & Demerouti, 2017; Hughes & Jex, 2022).

Job resources, on the other hand, describe the aspects of the job that help in the achievement of work-related goals and stimulate personal growth and development (Demerouti et al., 2001). They are “physical, psychological, social, or organizational aspects of the job that are either functional or both in achieving work goals, reduce job demands and the associated physiological and psychological costs, and stimulate personal growth, learning, and development” (Bakker & Demerouti, 2007, p. 312). These have inherent motivational qualities that spark employees' energy and make them feel engaged (Schaufeli, 2017). Examples include feedback, social support, autonomy and/or job control (Van den Broeck et al., 2013). There have been a few modifications since the publication of the JD-R theory by Demerouti et al. (2001), and one of them is the addition of personal resources (Bakker & Demerouti, 2007; Xanthopoulou et al., 2009). Personal resources describe an individual's belief in how much control he has over the environment (Bakker & Demerouti, 2017). It refers to an individual's psychological characteristics of the self that are associated with the individual's resiliency (Schaufeli & Taris, 2014). Examples of these personal resources are self-efficacy, self-esteem, and optimism (Xanthopoulou et al., 2007). Hence, all three – job demands, personal resources and job resources contribute to employees' wellbeing and engagement.

One main proposition of the JD-R theory is that job demands, personal resources, and job resources influence processes in different ways (Demerouti et al., 2001). While both high job demands and poor resources can result in burnout, abundant job resources, as well as low job demand contribute to employee engagement (Schaufeli, 2017). Thus, a high Job demand as a result of COVID-19 can have a negative psychological impact on employees, which may lead to employees being stressed and, as a result, leaving an organization. In contrast, high resources, where employees receive social support from colleagues and are allowed a level of job control, will foster employee engagement (Kim, 2017; Schaufeli, 2017). As a result, employees are likely to stay with the organization and work with vigor, become dedicated, and absorbed in their work.

2.2. Employee engagement

Employee engagement (EE) in the recent past has become one of the most important areas of interest for both scholars and practitioners. This is expected given the significant role EE plays in organizational competitiveness and sustainability (Sharma, 2021) and employees’ behavior, attitude, and performance (Bailey et al., 2017; Bhardwaj & Kalia, 2021; Pattnaik & Sahoo, 2021). Engaged workers tend to be very active in performing their jobs, develop a relationship with their colleagues, and define their tasks as “challenging” rather than “damaging” (Ghani et al., 2019).

The engagement literature shows that EE has been defined in a broad, more inclusive way than similar constructs like employee attitude, job involvement, job satisfaction, job embeddedness, burnout, and organizational commitment (Christian et al., 2011; Macey & Schneider, 2008; Vigoda-Gadot et al., 2013). It is described as a multi-dimensional construct that measures cognitive, affective, and behavioral or action, and as a result, the entire self of an engaged employee is involved in performing any task (Christian et al., 2011). Kahn (1990), often cited as the first to describe EE, explained it as “harnessing of organization members' selves to their work roles; in engagement, people employ and express themselves physically, cognitively, and emotionally during role performances” (p. 694). Thereafter, Rich et al. (2010) also defined it as the “simultaneous investment of an individual's physical, cognitive, and emotional energy in active, full work performance” (p. 619). In contrast, personal disengagement was explained by Kahn (1990) to mean “the uncoupling of selves from work roles; in disengagement, people withdraw and defend themselves physically, cognitively, or emotionally during role performances” (p. 694). From another perspective, the Institute for Employment Studies (IES) presented a detailed definition of EE and explained that it is the positive attitude an employee has toward the job, where such an employee collaborates and cooperates with his or her colleagues so that he or she can achieve an improved and better outcome (CIPD, 2017). As a result, the employer as well as the leaders have a responsibility to develop an effective relationship with their subordinates to create an engaged employee.

This study adopts how Schaufeli et al. (2002) conceptualize EE since it is hailed as a true representative of an engaged employee and therefore highly used in different fields (Jeung, 2011). An engaged employee exhibits certain characteristics, which are reflected in how EE is defined by Schaufeli et al. (2002). According to them, work engagement reflects a “positive, fulfilling, work-related state of mind that is characterized by vigor, dedication, and absorption” (p. 74). Vigor is characterized by high levels of energy and mental resilience while working and is therefore, ready to devote much time and effort to the task assigned (Schaufeli et al., 2002; Mauno et al., 2010). This characteristic makes the engaged employee willing to invest much effort in their work and sustain this high level of determination even when they encounter challenges (Gemeda & Lee, 2020). Thus, in addition to seeing vigor as a high mental level of positive energy and mental resilience during the time working (Schaufeli & Bakker, 2003), it involves the willingness to overcome difficulties while maintaining a passion for individual growth at the workplace (Stairs & Galpin, 2010).

Dedication refers to being strongly involved in one's work and experiencing a sense of significance, enthusiasm, and challenge (Schaufeli et al., 2002). The dedicated employees are therefore inspired, highly involved, and enthusiastic about the work assigned (Schaufeli et al., 2002; Schaufeli et al., 2006). This characteristic of engaged employees results in such employees experiencing a sense of purpose and being highly enthusiastic in their job (Gemeda & Lee, 2020). Absorption refers to a state of fully concentrating and being engrossed in one's work, and thus, time passes so fast without the individual recognizing it (Schafeli et al., 2002). This characteristic makes engaged employees have a sense of feeling detached from their surroundings and rather possess a high sense of concentration on the job and generally, unconscious about the amount of time spent on the job (Schaufeli et al., 2002; Schaufeli et al., 2006). Thus, engaged employees are well-absorbed in their work, very dedicated, and have a high mental level of positive energy and resilience, which makes them work with vigor. On the other hand, disengaged employees are demotivated to work and tend to be dissatisfied with their work as well as their position (Jeha et al., 2022). This causes them to be unproductive, disloyal to the organization, and more likely to leave the organization anytime the opportunity presents itself (Mondy & Martocchio, 2016).

2.3. Turnover intentions

Both researchers and practitioners are currently interested in the study of employee turnover (Belete, 2018) due to its effects, both positive and negative on organizational performance. Employee turnover refers to the rate at which an employer acquires and loses employees, as well as the rate at which staff tend to leave and join an organization (Armstrong, 2006). Additionally, it describes the ratio of employees who have left an organization during a particular period to the average number of employees in that organization during the same period (Byerly, 2012). Abbasi and Hollman (2000), however, believe that employee turnover does not describe only the voluntary termination of employees in an organization, but also involves the rotation of employees within the labor market, between firms, and between occupations. There are several factors that result in employee turnover. These can be job-related or personal factors (Amah & Oyetuunde, 2020). Examples of job-related factors include job satisfaction, employee work engagement (Edwards-Dandridge et al., 2020; Porath, 2014), employee perceptions of development (Kasdorf & Kayaalp, 2022), leadership and pay (Chen, Brown, Bowers, & Chang, 2015; Caffey, 2012), and personal factors such as age, gender, education, and marital status (Zhang & Zhang, 2003).

There are two major categories of turnover: voluntary and involuntary. Voluntary turnover describes the type of turnover that is initiated by the employee (Egan et al., 2004; NOE et al., 2006). For instance, an employee may leave one organization for another due to better pay or a better work environment. On the other hand, involuntary turnover is initiated by the organization (Heneman, Judge, & Kammeyer-Mueller, 2003; Egan et al., 2004). For example, the management of an organization may decide to terminate the employment of employees due to gross misconduct. High employee turnover has cost implications for the organization. The cost may be in terms of advertising expenses, headhunting fees, loss of time and efficiency, work imbalance, and employee training and development expenses for new recruits. Again, uncontrolled turnover causes disruption in the flow of work, which leads to reduced production and profits for the organization (Murphy, 2009). Another effect of the cost of the replacement of an employee, which takes time and lots of effort to recruit, select and place such employees, is a form of cost to the organization (Anthony, 2006). Although generally turnover seems to have a detrimental effect on performance, there may be some benefits like reduced labor costs and the elimination of unqualified employees (Heneman, Judge, & Kammeyer-Mueller, 2003).

Different factors have been cited as the antecedents of employee voluntary turnover. These include getting a new job offer, job dissatisfaction, and lack of job embeddedness (Dechawatanapaisal, 2017; Huning et al., 2020; Reyes et al., 2019), as well as some psychological factors such as job insecurity, anxiety, depression, and stress (Boyar et al., 2012; Ogony & Majola, 2018; Reyes et al., 2019). These may have a negative psychological impact on the employee. Psychological impact refers to the effect that an action or inaction, activity, or situation has on an individual's mind and thoughts. The World Health Organization encouraged organizations to introduce different work plans and practices at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, and some of these changes have affected employees psychologically, affecting their minds, thoughts, and perceptions of job security, financial stability, and work-family balance (Hebles et al., 2022) and general psychological wellbeing (Kokubun et al., 2022). Perceived lack of job security (Jung et al., 2021; Urbanaviciute et al., 2018), fear of contracting the disease (Abd-Ellatif et al., 2021) and an imbalance in work-family life (Aman-Ullah et al., 2022; Yu, 2019) could influence employees' turnover intentions. It can therefore be deduced and hypothesized that:

H1

The psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic affects employee turnover.

2.4. Employee engagement and turnover

A major strategy to adopt to enable leaders to anticipate and prevent employees from leaving an organization is to understand what influences their intention to quit (Parent-Lamarche, 2022). The anticipation and prevention of employee turnover have, therefore, become very important because if this is not done, the organization may lose competent employees (Kim et al., 2010). Findings from numerous studies show that a high predictor of employee turnover intention is their level of engagement (Edwards-Dandridge et al., 2020; Jung et al., 2021). This is why engagement is named the most influential psychological factor that can cause a reduction in employee turnover (Pattnaik & Panda, 2020; Rafiq et al., 2019; Shin & Jeung, 2019). Employee engagement refers to the level of commitment, energy, and involvement in which employees are willing to invest in the organization. It describes an employee's positive and/or negative association with the job, other employees, and work (Jaiswal et al., 2017). Employees with positive associations with the job and others they work with tend not to leave the organization, and vice versa.

A study by Hughes and Rog (2008) showed that the behavior of engaged employees influences an organization's success significantly. In that sense, these employees work with enthusiasm and have a relatively low intent to leave their organization. Santhanam and Srinivas (2019) also provide empirical evidence suggesting that a disengaged employee is likely to leave the organization in the near future. This is because a disengaged employee's lack of commitment and turnover intention, low energy, low prosocial behavior, withdrawal, disconnection, disaffection, disinterestedness, uncertainty, dissatisfaction, poor work performance, and counterproductive work behaviors (Rastogi et al., 2018) can affect turnover intentions. Thus, employee engagement is sufficiently and closely related to employee turnover. Work engagement, therefore, has a negative impact on employee turnover and plays an important role in reducing turnover (Babakus et al., 2017; Kim, 2017; Memon et al., 2020; Timms et al., 2015). Engaged employees display a high level of dedication, vigor, and absorption in their work. Employees who are highly dedicated are characterized as having a strong sense of pride, purpose, and inspiration (Schafeli et al., 2002), and it is an indicator of job satisfaction (Alarcon & Edwards, 2011; Lu et al., 2016). Employees who are satisfied with their jobs have a low tendency to leave their organization (Kurniawaty et al., 2019; Lu et al., 2016). Absorption is linked with intrinsic enjoyment while losing self-consciousness at work (Alarcon & Edwards, 2011), and this causes such employees to be immersed in their work, stay in the job to complete the task, and have difficulty quitting the job at the end of the work shift (Schaufeli et al., 2002). Again, employees who have high levels of vigor are highly motivated to excel in their jobs, regardless of the challenges they encounter (Salanova et al., 2005), and therefore less likely to quit their job (Kahn, 1990; Saks, 2006). This implies that a high level of employee engagement will cause a reduction in employee turnover.

2.5. Psychological impact of COVID-19, employee engagement and turnover intention

The COVID-19 pandemic has brought about a new reality that has had a psychological impact on employees. Some of these negative psychological impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic include depression, anxiety, insomnia, and stress (Aguiar et al., 2021; Nabi et al., 2022), and a high level of turnover (Labrague & de Los Santos, 2021). However, research shows that individuals who are strongly involved in their work and experience a sense of significance, that is, are dedicated (Schaufeli et al., 2002) tend to stay on their jobs (Halbesleben & Wheeler, 2008; Lu et al., 2016). Also, when employees who work with vigor and get absorbed in their work stay to complete any assignment (Lu et al., 2016). Engaged employees are known to work with vigor and dedication, get absorbed in their work, and therefore tend not to leave their organization.

It is, therefore, concluded that even though the covid-19 pandemic has had a significant negative psychological impact and has caused serious problems for individuals, organizations, families and communities around the world and a feeling of loneliness and poor cognitive performance (Donthu & Gustafsson, 2020), created high level of anxiety, and stress (Breaugh, 2021; Das et al., 2023; Orgambídez-Ramos et al., 2014; Uzun et al., 2020), increase intention to quit or turnover (Kachi et al., 2020; Anthony-McMann et al., 2017) and a feeling of job insecurity (Khan et al., 2021), engaged employees who are dedicated, work with vigor and are absorbed in their work (Schaufeli et al., 2002) will make a positive difference in the negative relationship between the psychological impact of COVID 19 pandemic on employee turnover. Accordingly, we propose that:

H2

Work engagement will moderate the relationship between psychological impact and turnover intentions.

Conceptual framework

3. Methodology

3.1. Sample and data collection procedure

A convenience sampling procedure was used to collect data from study participants working in the public sector. Using this approach appeared to be the most appropriate because, during the period of collecting the data, a number of public sector employees were being investigated on different allegations. This made public-sector employees hesitant to be involved in any form of giving out information. The adoption of the convenience sampling procedure, therefore helped collect data from individuals who were available, willing and it was convenient for them (Creswell, 2014). Again, using it ensured high internal validity, making the findings trustworthy (Andrade, 2021). Two public healthcare facilities based in the national capital, Accra and one government agency were selected for data collection. A total of 205 public sector employees were surveyed using a structured questionnaire. The questionnaires were distributed both online and through the paper-and-pencil method of hand delivery, with the help of departmental heads. The responses of 18 participants were removed from the final data set after the data cleansing process due to missing data, resulting in a final sample size of 187. To lessen the effects of common method variance and social desirability (Podsakoff et al., 2003), the items for the independent and dependent variables were separated in the survey, and the purpose of the study was explained to the respondents. Respondents were assured of anonymity and confidentiality of their responses and were also informed that the research is for academic purposes and that participation is completely voluntary. Participants were encouraged to complete and return the survey within three weeks. Respondents were mostly female (63.6%), and a majority of them (84%) were below the age of 40.

3.2. Measures

3.2.1. Psychological impact of COVID-19

The psychological impact of COVID-19 was measured using a seven-item scale that assessed work-related stressors due to COVID-19 (Morassaei et al., 2021). Participants were required to indicate to what extent they agree with statements on how they were impacted psychologically. Sample statements were “fear of transmitting COVID-19 into workplaces”, “fear of transmitting COVID-19 from work to family and friends”, and “changes in household income due to COVID-19”. Responses were rated on a five-point Likert scale, ranging from strongly disagree = 1 to strongly agree = 5. Higher scores indicated a greater level of stressors and anxiety due to COVID-19.

3.2.2. Employee engagement

The multi-dimensional construct of employee engagement (vigor, dedication, and absorption) was measured using a 17-item scale by Schaufeli et al. (2002). Sample items included “I feel bursting with energy at the workplace”, “I find the work that I do full of meaning and purpose”, and “When I am working, I forget everything else around me”. Participants responded on a five-point Likert scale, ranging from strongly disagree = 1 to strongly agree = 5. Higher scores indicated greater work engagement.

3.2.3. Turnover intentions

Employee turnover intentions were measured using a three-item subscale of the MOAQ (Cammann et al., 1983). The study participants were asked to indicate to what extent they agree with statements such as “I think a lot about leaving the organization” and “I am actively searching for an alternative to the organization”. Participants responded on a five-point Likert scale, ranging from strongly disagree = 1 to strongly agree = 5. Higher scores indicated a greater intention to leave the organization.

4. Results

4.1. Structural equation modeling

The data was analyzed using CB-based structural equation modeling technique of AMOS version 26 (Byrne, 2013). The results of the measurement model showed excellent fit indices (Chi-square = 90.56, df = 80, CMIN/DF = 1.1, RMSEA = 0.027, CFI = 0.999) (Hu & Bentler, 1999). Also, all the composite reliability and AVEs were above 0.7 and 0.50, respectively. Therefore, convergent validity was met (Table 1 ). All HTMT values were below 0.85; therefore, discriminant validity was met (Table 2 ).

Table 1.

Validity analysis.

| Variables | CR | AVE | MSV | MaxR(H) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Dedication | 0.87 | 0.63 | 0.284 | 0.894 | 0.794 | ||||

| 2. Turnover Intentions | 0.914 | 0.781 | 0.158 | 0.918 | −0.398*** | 0.884 | |||

| 3. Absorption | 0.741 | 0.500 | 0.269 | 0.756 | 0.519*** | −0.366*** | 0.7 | ||

| 4. Psychological Impact | 0.887 | 0.723 | 0.019 | 0.895 | 0.136 | 0.055 | 0.022 | 0.851 | |

| 5. Vigor | 0.755 | 0.61 | 0.284 | 0.806 | 0.533*** | −0.393*** | 0.425*** | −0.126 | 0.781 |

Table 2.

HTMT.

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Dedication | _ | ||||

| 2. Turnover Intentions | 0.388 | _ | |||

| 3. Absorption | 0.485 | 0.367 | _ | ||

| 4. Psychological Impact | 0.126 | 0.054 | 0.03 | _ | |

| 5. Vigor | 0.514 | 0.367 | 0.443 | 0.152 | _ |

Convergent validity refers to the degree to which individual items reflect, converge or share a high proportion of variance in common (Hair et al., 2011), as compared to items measuring different constructs. To ascertain convergent validity, average variance extracted (AVE) was used as suggested by Hair et al. (2014). Convergent validity of a factor is achieved when the AVE value of a construct is at least 0.5 and the standardized loadings of items are significant and higher than 0.5 or 0.7 (Hair et al., 2014). Discriminant validity was used to differentiate measures of construct from one another. It refers to the degree to which two concepts that are similar are distinct (Hair et al., 2011).

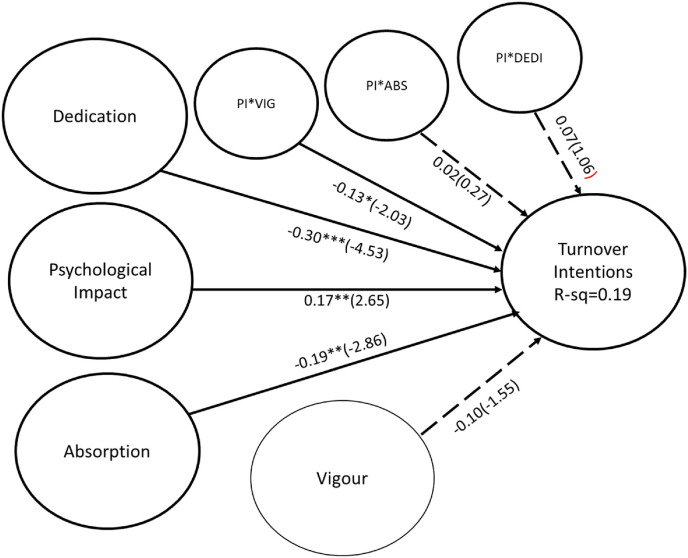

The structural model presented in Fig. 1 shows that a positive and significant relationship exists between the psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and turnover intentions, thus lending support to Hypothesis H1. This implies that the most impacted public sector employees due to COVID-19 were the most likely to exit the service. Of the three dimensions of work engagement, vigor had a significant negative moderating effect on the relationship between psychological impact and turnover intentions, thus lending partial support to hypothesis H2. This implies that the positive effect of psychological impact on turnover intentions is minimized, where vigor is high rather than low.

Fig. 1.

Structural Model Analysis.

Note: PI*VIG (Interaction between psychological impact and Vigor); PI*ABS (Interaction between psychological impact and Absorption); PI*DEDI (Interaction between psychological impact and Dedication) ***p < 0.001; **p < 0.01; *p < 0.05; Dotted line means path is not statistically significant.

4.2. Moderating analysis

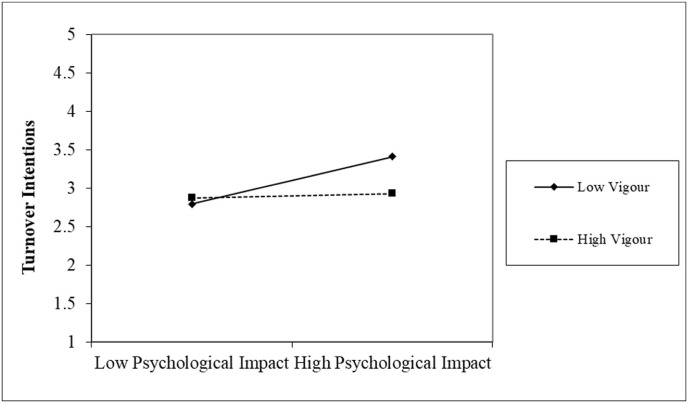

The negative moderating effect of vigor in the relationship between psychological impact and turnover intentions is illustrated in Fig. 2 . It can be observed that the two slopes are not parallel, showing evidence of moderation. The moderation is negative because low values of vigor are increasing faster than their corresponding high values.

Fig. 2.

Moderating effect of vigor on the psychological impact of COVID-19 and turnover intention.

5. Discussion

This study examined the psychological effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on employee turnover intention and tested whether employee engagement (vigor, absorption, and dedication) moderates the relationship. Consistent with the literature and expectations, results showed a positive and significant relationship between the psychological effect of the COVID-19 pandemic and turnover intentions, thus lending support to Hypothesis H1. This implies that the COVID-19 pandemic psychologically affects employee turnover in developing countries. Some psychological effects of the COVID-9 pandemic are depression, anxiety, stress, and fear (Nabi et al., 2022; Obuobisa-Darko, 2022). The findings from this study are consistent with several studies carried out in developed countries, which have confirmed a positive relationship between COVID-19 and turnover (Chen & Qi, 2022; Li et al., 2022; Uludag et al., 2022). These findings can be explained from the perspective that employees' lives, safety, and well-being have been threatened; there was an increase in the mortality rate of employees during the COVID-19 period which made working in the workplace a threat to their lives, thus the relationship with turnover. Since employees’ fear and anxiety about COVID-19 have been shown to increase their turnover intentions (Chen & Qi, 2022; Kokubun et al., 2022; Uludag et al., 2022) as well as turnover, it can thus be concluded that the anxiety, fear, and stress of employees about COVID-19, explains the relationship between COVID-19 and turnover intention.

Again, consistent with the assumptions of the JD-R theory, high job demands cause employees to be stressed (Ben-Ezra & Hamama-Raz, 2021; Hamann & Foster, 2014), and when employees are stressed, it affects organizational commitment negatively (Saadeh & Suifan, 2019) and such employees tend to leave the organization (Mosadeghrad, 2013). The literature confirms that the COVID-19 pandemic resulted in high job demand (Ben-Ezra & Hamama-Raz, 2021) and caused employees to be stressed (Kundu et al., 2022). Consequently, arguing from the JD-R theory's perspective, with a high job demand as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, employees get stressed and therefore tend to leave, which explains the results of this study.

Further, this study found a significant negative moderating effect of vigor on the relationship between psychological impact and employee turnover intention. This implies that the effect of psychological impact on turnover intention is minimized, where employees' vigor is high. Thus, the observation that vigor has a significant negative moderating effect in this relationship makes sense. It indicates that being fully immersed in one's activities, having a high level of energy and mental resilience while working, and therefore devoting much effort to work positively relates to employee satisfaction and commitment to the organization. Thus, it reduces the tendency of employees to leave the organization. While employees who have a high level of energy and mental peace are said to have the vigor to perform and are willing to work continuously for long hours (Gera, Sharma, & Saini, 2019), those with low levels of vigor are associated with high turnover intention (Coetzee & van Dyk, 2018). Therefore, having employees who have a high level of energy and consequently, devote much effort to work, will tend to stay with the organization. This explains why when employees have high levels of vigor, it reduces the extent to which they would like to leave the organization, even if they are anxious, fearful, frustrated, or stressed.

6. Implications

6.1. Theoretical implications

The present study examined the psychological impact of COVID-19 on employee turnover intention, with work engagement as a moderating variable in the relationship. This study contributes significantly to a growing body of knowledge relating to the impact of COVID-19 on employees' work outcomes, specifically, their turnover intentions. Also, the study adds to the limited empirical evidence on the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on employee turnover intentions in public sector organizations. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to empirically explore the psychological effect of COVID-19 on employee turnover intention in the public sector from a developing country's context using the JD-R as the underpinning theory. According to the JD-R model, certain work-related factors can have an effect on employee well-being and performance (Bakker & Demerouti, 2017). In addition, this paper explores the moderating effect of employee engagement, specifically vigor, dedication, and absorption, in the relationship between the psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and turnover intention and found vigor, one of the dimensions of employee engagement to moderate the relationship. Thus, contrary to our hypothesized model, dedication and absorption dimensions were not significant as moderators between the psychological impact of COVID-19 and turnover intention. The findings of this study also lend support to the claim that individual employees experienced varied levels of anxiety, stress, fear, and discomfort during the pandemic (Kundu et al., 2022; Nabi et al., 2022; Obuobisa-Darko, 2022), which had implications on their intention to leave the job.

6.2. Managerial implications

The results of this study have valuable implications for managers and human resource practitioners. The study highlights the significant role of psychological well-being in employees' decisions to remain working in their organizations or not. Employees' safety, mental, and psychological health and well-being are critical and particularly non-negotiable in uncertain situations such as the COVID-19 pandemic. As a result, organizations that seek to retain their workforce must prioritize and ensure their employees' psychological wellbeing. Thus, top management and human resource practitioners should adopt and implement people management practices and policies that safeguard employees’ health and safety and ensure their psychological wellbeing.

Second, our study shows that vigor, one of the dimensions of employee engagement, moderates the psychological impact of COVID-19 and turnover intention. Employees in the public sector who are engaged in their work and derive meaning from what they do are more likely to become loyal, attached to their organizations, and devote much time and effort to their work. This could influence their decision to remain with their employers. Hence, organizations should initiate and implement high-engagement work systems to secure high levels of mental resilience and energy in their employees.

7. Limitations and future research directions

Even though some important findings have emerged from this study which contribute to a burgeoning body of research on the psychological impact of COVID-19 on employees’ engagement and turnover intentions, it is not without limitations. First, this study collected data using a self-report survey instrument and adopted a cross-sectional design, increasing the possibility of common method variance (Podsakoff et al., 2003). As a strategy to minimize the potential for common method bias in the present study, the items for the independent and dependent variables were separated in the survey (Podsakoff et al., 2003). It is, therefore, recommended that future studies use more objective measures for examining COVID-19 and employee work outcomes. Another possible way to extend this research is to make use of longitudinal data, which could provide more holistic evidence to enhance our understanding of the relationships among the study variables. Second, the study did not measure actual turnover. While meta-analytic studies have provided evidence suggesting that turnover intention has a significant positive relationship with turnover (Podsakoff et al., 2007), future studies could investigate turnover using turnover analysis data from organizations. Third, this research was limited to the analysis of data from public sector employees. Given that the working conditions and general work climate in the public sector organizations might vary from what exists in the private sector, similar studies could be extended to other organizations in the private sector for comparative analysis. Future researchers who intend to replicate this research could consider using a probability sampling technique and a mixed methods research design to explore, validate, and enhance the generalisability of their findings. The mixed methods research represents a comprehensive research technique that integrates thematic and statistical data leading to the validity and reliability of results. Finally, the vigor dimension of work engagement was used to explain the relationship between the psychological impact of COVID-19 and turnover intention. There could be other moderation or mediation variables such as perceived organizational support, and supervisor and co-worker support that are yet to be explored. Building on this research, it would be insightful for future studies to examine the various sources of support in the relationship between psychological impact of COVID-19 and turnover intention.

8. Conclusions

This paper aimed at understanding the relationship between the psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and turnover intention and the moderating role of employee engagement. Guided by the JD-R theory, the aim was founded on the notion that excessive job demands, including anxiety and uncertainties during the COVID-19 era, could lead to sustained stress and work overload, which will cause employees to wish to leave an organization. However, when employees are engaged and therefore vigorous, dedicated, and absorbed, it reduces the negative effects, such as stress and anxiety on employees’ turnover intentions. This inquiry was necessitated by the fact that the COVID-19 pandemic had a psychological effect on employees in the public sector, which could influence turnover intentions. Since PSOs (Public Sector Organizations) need employees who are ready to stay and provide the needed services to the public, there is a need to identify what can minimize this negative effect caused by the psychological effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on turnover.

Using the quantitative approach to research, questionnaires were distributed via Google Docs and hand-delivered to employees in the public sector in the Greater Accra region. Results showed a positive and significant relationship between the psychological effect of the COVID-19 pandemic and turnover intentions, thus lending support to Hypothesis H1. Further, this study found a significant negative moderating effect of vigor on the relationship between the psychological impact and employees' turnover intention, which is noteworthy. This implies that the positive effect of the psychological impact on turnover intentions is minimized where employees’ vigor is high rather than low.

Contextual factors, to a large extent, create differences in the behavior of employees. Nevertheless, results from this study largely establish that there exists a positive and significant relationship between the psychological effect of the COVID-19 pandemic and turnover intentions, irrespective of whether it is a developed or developing country. This finding is very important in PSOs due to the kind of services they deliver. It is therefore critical that leaders in these organizations understand their role in ensuring that the psychological effect of the COVID-19 pandemic does not negatively impact employees’ turnover. By understanding this, they can identify and adopt appropriate measures to enhance employee engagement, which will significantly affect their turnover intentions. Thus, the employees will be engaged and vigorous, in order for them to stay and provide unique services to the public.

Credit author statement

All All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by Prof. Theresa Oboubisa-Darko and Dr. Evans Sokro. Literature review section of the manuscript was written by Prof. Theresa Oboubisa-Darko while Dr. Evans Sokro took care of the introduction and discussion. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Dr. Evans Sokro and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Abbasi S.M., Hollman K.W. Turnover: The real bottom line. Public Personnel Management. 2000;29(3):333–342. [Google Scholar]

- Abd-Ellatif E.E., Anwar M.M., AlJifri A.A., El Dalatony M.M. Fear of COVID-19 and its impact on job satisfaction and turnover intention among Egyptian physicians. Safety and Health at Work. 2021;12(4):490–495. doi: 10.1016/j.shaw.2021.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aday S., Aday M.S. Impact of COVID-19 on the food supply chain. Food Quality and Safety. 2020;4(4):167–180. [Google Scholar]

- Aguiar A., Maia I., Duarte R., Pinto M. The other side of COVID-19: Preliminary results of a descriptive study on the COVID-19-related psychological impact and social determinants in Portugal residents. Journal of Affective Disorders Reports. 2021;7:100294. doi: 10.1016/j.jadr.2021.100294. 100294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad S., Masood S., Khan N.Z., Badruddin I.A., Ahmadian A., Khan Z.A., Khan A.H. Analysing the impact of COVID-19 pandemic on the psychological health of people using fuzzy MCDM methods. Operations Research Perspectives. 2023;10 [Google Scholar]

- Akat M., Karataş K. Psychological effects of COVID-19 pandemic on society and its reflections on education. Electronic Turkish Studies. 2020;15(4):1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Alarcon G.M., Edwards J.M. The relationship of engagement, job satisfaction and turnover intentions. Stress and Health. 2011;27(3):e294–e298. [Google Scholar]

- Amah O.E., Oyetuunde K. The effect of servant leadership on employee turnover in SMEs in Nigeria: The role of career growth potential and employee voice. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development. 2020;27(6):885–904. [Google Scholar]

- Aman-Ullah A., Ibrahim H., Aziz A., Mehmood W. Balancing is a necessity not leisure: A study on work–life balance witnessing healthcare sector of Pakistan. Asia-Pacific Journal of Business Administration. 2022 doi: 10.1108/APJBA-09-2020-0338. ahead-of-print. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Andrade C. The inconvenient truth about convenience and purposive samples. Indian Journal of Psychological Medicine. 2021;43(1):86–88. doi: 10.1177/0253717620977000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anthony W. 5th ed. Thomson Publishers; 2006. Human resource management. [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong M. Kogan Page Publishers; 2006. A handbook of human resource management practice. [Google Scholar]

- Arnould E.J., Price L., Moisio R. Making contexts matter: Selecting research contexts for theoretical insights. Handbook of Qualitative Research Methods in Marketing. 2006:106–125. [Google Scholar]

- Asif H.M., Hashmi H.A.S., Zahid R., Ahmad K., Nazar H. COVID-19 pandemic impact on mental health and quality of life among general population in Pakistan. Mental Health Review Journal. 2022;27(3):319–332. [Google Scholar]

- Babakus E., Yavas U., Karatepe O.M. Work engagement and turnover intentions: Correlates and customer orientation as a moderator. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management. 2017;29(6):1580–1598. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey C., Madden A., Alfes K., Fletcher L. The meaning, antecedents and outcomes of employee engagement: A narrative synthesis. International Journal of Management Reviews. 2017;19(1):31–53. [Google Scholar]

- Bakker A.B., Demerouti E. The job demands‐resources model: State of the art. Journal of Managerial Psychology. 2007;22(3):309–328. [Google Scholar]

- Bakker A.B., Demerouti E. Job demands–resources theory: Taking stock and looking forward. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology. 2017;22(3):273. doi: 10.1037/ocp0000056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakker A.B., Demerouti E., Sanz-Vergel A.I. Burnout and work engagement: The JD–R approach. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior. 2014;1(1):389–411. [Google Scholar]

- Barbisch D., Koenig K.L., Shih F.Y. Is there a case for quarantine? Perspectives from SARS to ebola. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness. 2015;9(5):547–553. doi: 10.1017/dmp.2015.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belete A.K. Turnover intention influencing factors of employees: An empirical work review. Journal of Entrepreneurship & Organization Management. 2018;7(3):1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Ezra M., Hamama-Raz Y. Social workers during COVID-19: Do coping strategies differentially mediate the relationship between job demand and psychological distress? British Journal of Social Work. 2021;51(5):1551–1567. [Google Scholar]

- Bhardwaj B., Kalia N. Contextual and task performance: Role of employee engagement and organizational culture in hospitality industry. Vilakshan-XIMB Journal of Management. 2021;18(2):187–201. [Google Scholar]

- Boyar S.L., Valk R., Maertz C.P., Sinha R. Linking turnover reasons to family profiles for IT/BPO employees in India. Journal of Indian Business Research. 2012;4(1):6–23. [Google Scholar]

- Breaugh J. Too stressed to be engaged? The role of basic needs satisfaction in understanding work stress and public sector engagement. Public Personnel Management. 2021;50(1):84–108. [Google Scholar]

- Byerly B. Measuring the impact of employee loss. Performance Improvement. 2012;51(5):40–47. [Google Scholar]

- Caffey R.D. University of Missouri-Columbia; 2012. The relationship between servant leadership of principals and beginning teacher job satisfaction and intent to stay. [Google Scholar]

- Cammann C., Fichman M., Jenkins G.D., Klesh J.R. In: Assessing organizational change: A guide to methods, measures, and practices. Seashore S.E., Lawler E.E., Mirvis P.H., Cammann C., editors. Wiley; 1983. The MI organizational assessment questionnaire: Assessing the attitudes and perceptions of organizational members; pp. 71–138. [Google Scholar]

- Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development . 2017. Developing managers to manage sustainable employee engagement, health and well-being. Research Report Phase 2. London. [Google Scholar]

- Chen I.H., Brown R., Bowers B.J., Chang W.Y. Work‐to‐family conflict as a mediator of the relationship between job satisfaction and turnover intention. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2015;71(10):2350–2363. doi: 10.1111/jan.12706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H., Qi R. Restaurant frontline employees' turnover intentions: Three-way interactions between job stress, fear of COVID-19, and resilience. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management. 2022;34(7):2535–2558. [Google Scholar]

- Christian M.S., Garza A.S., Slaughter J.E. Work engagement: A quantitative review and test of its relations with task and contextual performance. Personnel Psychology. 2011;64(1):89–136. [Google Scholar]

- Coetzee M., van Dyk J. Workplace bullying and turnover intention: Exploring work engagement as a potential mediator. Psychological Reports. 2018;121(2):375–392. doi: 10.1177/0033294117725073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coffie R.B., Gyimah R., Boateng K.A., Sardiya A. Employee engagement and performance of MSMEs during COVID-19: The moderating effect of job demands and job resources. African Journal of Economic and Management Studies. 2023 doi: 10.1108/AJEMS-04-2022-0138. ahead-of-print. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Creswell J.W. 2014. Research design: Qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods. [Google Scholar]

- Das H., Maca R., Balamurugan G., Gurung K. Anxiety level in covid-19 survivors. International Journal of Psychiatric Nursing. 2023;9(4):21–23. [Google Scholar]

- De Croon E.M., Sluiter J.K., Blonk R.W., Broersen J.P., Frings-Dresen M.H. Stressful work, psychological job strain, and turnover: A 2-year prospective cohort study of truck drivers. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2004;89(3):442. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.89.3.442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dechawatanapaisal D. The mediating role of organizational embeddedness on the relationship between quality of work life and turnover: Perspectives from healthcare professionals. International Journal of Manpower. 2017;38(5):696–711. [Google Scholar]

- Demerouti E., Bakker A.B., Nachreiner F., Schaufeli W.B. The job demands-resources model of burnout. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2001;86(3):499. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donthu N., Gustafsson A. Effects of COVID-19 on business and research. Journal of Business Research. 2020;117:284–289. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du L., Razzaq A., Waqas M. The impact of COVID-19 on small-and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs): Empirical evidence for green economic implications. Environmental Science and Pollution Research. 2023;30(1):1540–1561. doi: 10.1007/s11356-022-22221-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Edwards-Dandridge Y., Simmons B.D., Campbell D.G. Predictor of turnover intention of register nurses: Job satisfaction or work engagement? International Journal of Applied Management and Technology. 2020;19(1):7. [Google Scholar]

- Egan T.M., Yang B., Bartlett K.R. The effects of organizational learning culture and job satisfaction on motivation to transfer learning and turnover intention. Human Resource Development Quarterly. 2004;15(3):279–301. [Google Scholar]

- Gemeda H.K., Lee J. Leadership styles, work engagement and outcomes among information and communications technology professionals: A cross-national study. Heliyon. 2020;6(4) doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e03699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gera N.A.V.N.E.E.T.R.K., Sharma R., Saini P. Absorption, vigor and dedication: Determinants of employee engagement in B-schools. Indian Journal of Economics and Business. 2019;18(1):61–70. [Google Scholar]

- Ghani A., Kaliappen N., Jermsittiparsert K. Enhancing Malaysian SME employee work engagement: The mediating role of job crafting in the presence of task complexity, self-efficacy and autonomy. International Journal of Innovation, Creativity and Change. 2019;6(11):1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Grey I., Arora T., Thomas J., Saneh A., Tohme P., Abi-Habib R. The role of perceived social support on depression and sleep during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychiatry Research. 2020;293 doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hair J.F., Hult G.T.M., Ringle C.M., Sarstedt M. Sage; Thousand Oaks: 2014. A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) [Google Scholar]

- Hair J.F., Ringle C.M., Sarstedt M. PLS-SEM: Indeed a silver bullet. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice. 2011;19(2):139–152. [Google Scholar]

- Halbesleben J.R., Wheeler A.R. The relative roles of engagement and embeddedness in predicting job performance and intention to leave. Work & Stress. 2008;22(3):242–256. [Google Scholar]

- Hamann D.J., Foster N.T. An exploration of job demands, job control, stress, and attitudes in public, nonprofit, and for-profit employees. Review of Public Personnel Administration. 2014;34(4):332–355. [Google Scholar]

- Hebles M., Trincado-Munoz F., Ortega K. Stress and turnover intentions within healthcare teams: The mediating role of psychological safety, and the moderating effect of COVID-19 worry and supervisor support. Frontiers in Psychology. 2022;12:6594. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.758438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heneman H.G., Judge T., Kammeyer-Mueller J.D. Mendota House; Middleton, WI: 2003. Staffing organizations. [Google Scholar]

- Huang L., Wang Y., Liu J., Ye P., Chen X., Xu H.…Ning G. Factors influencing anxiety of health care workers in the radiology department with high exposure risk to COVID-19. Medical Science Monitor: International Medical Journal of Experimental and Clinical Research. 2020;26 doi: 10.12659/MSM.926008. 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L.T., Bentler P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal. 1999;6(1):1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes I.M., Jex S.M. Individual differences, job demands and job resources as boundary conditions for relations between experienced incivility and forms of instigated incivility. International Journal of Conflict Management. 2022;33(5):909–932. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes J.C., Rog E. Talent management: A strategy for improving employee recruitment, retention and engagement within hospitality organizations. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management. 2008;20(7):743–757. [Google Scholar]

- Huning T.M., Hurt K.J., Frieder R.E. The effect of servant leadership, perceived organizational support, job satisfaction and job embeddedness on turnover intentions: An empirical investigation. Evidence-Based HRM: A Global Forum for Empirical Scholarship. 2020;8(2):177–194. [Google Scholar]

- International Labour Organization . 2022. The next normal: The changing workplace in Ghana Employers Association (GEA) [Google Scholar]

- Jaiswal G., Pathak R., Kumari S. Impact of employee engagement on job satisfaction and motivation. Global Advancements in HRM Innovation and Practices. 2017:68–78. [Google Scholar]

- Jeha H., Knio M., Bellos G. COVID-19: Tackling global pandemics through scientific and social tools. 2022. The impact of compensation practices on employees' engagement and motivation in times of COVID-19; pp. 131–149. [Google Scholar]

- Jeung C.W. The concept of employee engagement: A comprehensive review from a positive organizational behavior perspective. Performance Improvement Quarterly. 2011;24(2):49–69. [Google Scholar]

- Jung H.S., Jung Y.S., Yoon H.H. COVID-19: The effects of job insecurity on the job engagement and turnover intent of deluxe hotel employees and the moderating role of generational characteristics. International Journal of Hospitality Management. 2021;92 doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jungmann S.M., Witthöft M. Health anxiety, cyberchondria, and coping in the current COVID-19 pandemic: Which factors are related to coronavirus anxiety? Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2020;73 doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2020.102239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kachi Y., Inoue A., Eguchi H., Kawakami N., Shimazu A., Tsutsumi A. Occupational stress and the risk of turnover: A large prospective cohort study of employees in Japan. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):1–8. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-8289-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahn W.A. Psychological conditions of personal engagement and disengagement at Work. Academy of Management Journal. 1990;33(4):692–724. [Google Scholar]

- Kasdorf R.L., Kayaalp A. Employee career development and turnover: A moderated mediation model. International Journal of Organizational Analysis. 2022;30(2):324–339. doi: 10.1108/IJOA-09-2020-2416. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Khan K.I., Niazi A., Nasir A., Hussain M., Khan M.I. The effect of COVID-19 on the hospitality industry: The implication for open innovation. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity. 2021;7(1):30. [Google Scholar]

- Kim W. Examining mediation effects of work engagement among job resources, job performance, and turnover intention. Performance Improvement Quarterly. 2017;29(4):407–425. [Google Scholar]

- Kim B.P., Lee G., Carlson K.D. An examination of the nature of the relationship between Leader-Member-Exchange (LMX) and turnover intent at different organizational levels. International Journal of Hospitality Management. 2010;29(4):591–597. [Google Scholar]

- Kokubun K., Ino Y., Ishimura K. Social and psychological resources moderate the relation between anxiety, fatigue, compliance and turnover intention during the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Workplace Health Management. 2022;15(3):262–286. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S., Panda T.K., Behl A., Kumar A. A mindful path to the COVID-19 pandemic: An approach to promote physical distancing behavior. International Journal of Organizational Analysis. 2021;29(5):1117–1143. doi: 10.1108/IJOA-. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kundu S.C., Tuteja P., Chahar P. COVID-19 challenges and employees' stress: Mediating role of family-life disturbance and work-life imbalance. Employee Relations: The International Journal. 2022;44(6):1318–1337. doi: 10.1108/ER-03-2021-0090. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kurniawaty K., Ramly M., Ramlawati R. The effect of work environment, stress, and job satisfaction on employee turnover intention. Management Science Letters. 2019;9(6):877–886. [Google Scholar]

- Labrague L.J., de Los Santos J.A.A. Fear of Covid‐19, psychological distress, work satisfaction and turnover intention among frontline nurses. Journal of Nursing Management. 2021;29(3):395–403. doi: 10.1111/jonm.13168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labrague L.J., De los Santos J.A.A. COVID‐19 anxiety among front‐line nurses: Predictive role of organisational support, personal resilience and social support. Journal of Nursing Management. 2020;28(7):1653–1661. doi: 10.1111/jonm.13121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lange M., Licaj I., Stroiazzo R., Rabiaza A., Le Bas J., Le Bas F., Humbert X. COVID-19 psychological impact in general practitioners: A longitudinal study. L'encephale. 2023 doi: 10.1016/j.encep.2023.03.001. ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J.C., Cheung C.K., Sun I.Y., Cheung Y.K., Zhu S. Work–family conflicts, stress, and turnover intention among Hong Kong police officers amid the covid-19 pandemic. Police Quarterly. 2022;25(3):281–309. doi: 10.1177/10986111211034777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu L., Lu A.C.C., Gursoy D., Neale N.R. Work engagement, job satisfaction, and turnover intentions: A comparison between supervisors and line-level employees. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management. 2016;28(4):737–761. [Google Scholar]

- Macey W.H., Schneider B. The meaning of employee engagement. Industrial and Organizational Psychology. 2008;1(1):3–30. [Google Scholar]

- Magnavita N. Perceived job strain, anxiety, depression and musculo-skeletal disorders in social care workers. Giornale Italiano di Medicina del Lavoro ed Ergonomia. 2009;31(1 Suppl A):A24–A29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mauno S., Kinnunen U., Mäkikangas A., Feldt T. Job demands and resources as antecedents of work engagement: A qualitative review and directions for future research. Handbook of Employee Engagement. 2010:111–128. [Google Scholar]

- Memon M.A., Salleh R., Mirza M.Z., Cheah J.H., Ting H., Ahmad M.S., Tariq A. Satisfaction matters: The relationships between HRM practices, work engagement and turnover intention. International Journal of Manpower. 2020;42(1):21–50. [Google Scholar]

- Mondy R.W., Martocchio J.J. Pearson; 2016. Human resource management. [Google Scholar]

- Morassaei S., Di Prospero L., Ringdalen E., Olsen S.S., Korsell A., Erler D.…Johansen S. A survey to explore the psychological impact of the COVID‐19 pandemic on radiation therapists in Norway and Canada: A tale of two countries. Journal of Medical Radiation Sciences. 2021;68(4):407–417. doi: 10.1002/jmrs.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morin C.M., Bjorvatn B., Chung F., Holzinger B., Partinen M., Penzel T.…Espie C.A. Insomnia, anxiety, and depression during the COVID-19 pandemic: An international collaborative study. Sleep Medicine. 2021;87:38–45. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2021.07.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosadeghrad A.M. Quality of working life: An antecedent to employee turnover intention. International Journal of Health Policy and Management. 2013;1(1):43. doi: 10.15171/ijhpm.2013.07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy R. 2nd ed. Pearson Publishers; 2009. Human resource planning. [Google Scholar]

- Nabi S.G., Rashid M.U., Sagar S.K., Ghosh P., Shahin M., Afroz F.…Ahmed H.U. Psychological impact of COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional study of hospitalized COVID-19 patients in an urban setting, Bangladesh. Heliyon. 2022;8(3) doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e09110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nkansah D., Gyimah R., Sarpong D.A.A., Annan J.K. The effect of employee engagement on employee performance in Ghana's MSMEs sector during COVID-19: The moderating role of job resources. Open Journal of Business and Management. 2022;11(1):96–132. [Google Scholar]

- Noe R., Hollenbeck J., Gerhart B., Wright P. Tenth Global Edition. McGraw-Hill Education; New York, MA: 2006. Human resources management: Gaining a competitive advantage. [Google Scholar]

- Obuobisa-Darko T. Managing employees' health, safety and anxiety in a pandemic. International Journal of Workplace Health Management. 2022;15(2):113–130. [Google Scholar]

- Ogony S.M., Majola B.K. Factors causing employee turnover in the public service, South Africa. Journal of Management & Administration. 2018;2018(1):77–100. [Google Scholar]

- Orgambídez-Ramos A., Borrego-Alés Y., Mendoza-Sierra I. Role stress and work engagement as antecedents of job satisfaction in Spanish workers. Journal of Industrial Engineering and Management. 2014;7(1):360–372. [Google Scholar]

- Pappa S., Ntella V., Giannakas T., Giannakoulis V.G., Papoutsi E., Katsaounou P. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and insomnia among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. 2020;88:901–907. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parent-Lamarche A. Teleworking, work engagement, and intention to quit during the COVID-19 pandemic: Same storm, different boats? International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022;19(3):1267. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19031267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passavanti M., Argentieri A., Barbieri D.M., Lou B., Wijayaratna K., Mirhosseini A.S.F.…Ho C.H. The psychological impact of COVID-19 and restrictive measures in the world. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2021;283:36–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2021.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pattnaik S.C., Panda N. Supervisor support, work engagement and turnover intentions: Evidence from Indian call centres. Journal of Asia Business Studies. 2020;14(5):621–635. [Google Scholar]

- Pattnaik S.C., Sahoo R. Employee engagement, creativity, and task performance: Role of perceived workplace autonomy. South Asian Journal of Business Studies. 2021;10(2):227–241. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff N.P., LePine J.A., LePine M.A. Differential challenge stressor-hindrance stressor relationships with job attitudes, turnover intentions, turnover, and withdrawal behavior: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2007;92(2):438. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.92.2.438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff P.M., MacKenzie S.B., Lee J.Y., Podsakoff N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2003;88(5):879. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porath C. Half of employees don't feel respected by their bosses. Harvard Business Review. 2014;19 [Google Scholar]

- Rafiq M., Wu W., Chin T., Nasir M. The psychological mechanism linking employee work engagement and turnover intention: A moderated mediation study. Work. 2019;62(4):615–628. doi: 10.3233/WOR-192894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rastogi A., Pati S.P., Krishnan T.N., Krishnan S. Causes, contingencies, and consequences of disengagement at work: An integrative literature review. Human Resource Development Review. 2018;17(1):62–94. [Google Scholar]

- Reyes A.C.S., Aquino C.A., Bueno D.C. Why employees leave: Factors that stimulate resignation resulting in creative retention ideas. CCAR Journal: A Multidisciplinary Research Review. 2019;14(1):14–24. [Google Scholar]

- Rich B.L., Lepine J.A., Crawford E.R. Job engagement: Antecedents and effects on job performance. Academy of Management Journal. 2010;53(3):617–635. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Martín B., Ramírez-Moreno J.M., Caro-Alonso P.Á., Novo A., Martínez-Andrés M., Clavijo-Chamorro M.Z.…López-Espuela F. The psychological impact on frontline nurses in Spain of caring for people with COVID-19. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing. 2022;41:27–34. doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2022.07.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruël H., Van der Kaap H. E-HRM usage and value creation: Does a facilitating context matter? German Journal of Human Resource Management. 2012;26(3):260–281. [Google Scholar]

- Saadeh I.M., Suifan T.S. Job stress and organizational commitment in hospitals: The mediating role of perceived organizational support. International Journal of Organizational Analysis. 2019;28(1):226–242. [Google Scholar]

- Saks A.M. Antecedents and consequences of employee engagement. Journal of Managerial Psychology. 2006;21(7):600–619. [Google Scholar]

- Salanova M., Agut S., Peiró J.M. Linking organizational resources and work engagement to employee performance and customer loyalty: The mediation of service climate. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2005;90(6):1217–1227. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.90.6.1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santhanam N., Srinivas S. Modeling the impact of employee engagement and happiness on burnout and turnover intention among blue-collar workers at a manufacturing company. Benchmarking: An International Journal. 2019;27(2):499–516. [Google Scholar]

- Schaufeli W.B. Applying the job demands-resources model. Organizational Dynamics. 2017;2(46):120–132. [Google Scholar]

- Schaufeli W.B., Bakker A.B. Department of Psychology, Utrecht University; 2003. UWES – utrecht work engagement scale: Test manual. [Google Scholar]

- Schaufeli W.B., Bakker A.B., Salanova M. The measurement of work engagement with a short questionnaire: A cross-national study. Educational and Psychological Measurement. 2006;66:701–716. [Google Scholar]

- Schaufeli W.B., Salanova M., González-Romá V., Bakker A.B. The measurement of engagement and burnout: A two sample confirmatory factor analytic approach. Journal of Happiness studies. 2002;3:71–92. [Google Scholar]

- Schaufeli W.B., Taris T.W. A critical review of the job demands-resources model: Implications for improving work and health. Bridging Occupational, Organizational and Public Health. 2014:43–68. [Google Scholar]

- Serafini G., Parmigiani B., Amerio A., Aguglia A., Sher L., Amore M. The psychological impact of COVID-19 on the mental health in the general population. QJM: International Journal of Medicine. 2020;113(8):531–537. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcaa201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma N. Using positive deviance to enhance employee engagement: An interpretive structural modelling approach. International Journal of Organizational Analysis. 2021;30(1):84–98. [Google Scholar]

- Shin I., Jeung C.W. Uncovering the turnover intention of proactive employees: The mediating role of work engagement and the moderated mediating role of job autonomy. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2019;16(5):843. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16050843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stairs M., Galpin M. online edition Oxford University Press; 2010. Positive engagement: From employee engagement to workplace happiness, 155–172. accessed 23 Feb. 2023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Takyi P.O., Bosco J.D., Akosah N.K., Aawaar G. Economic activities' response to the COVID-19 pandemic in developing countries. Scientific African. 2023 doi: 10.1016/j.sciaf.2023.e01642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tee M.L., Tee C.A., Anlacan J.P., Aligam K.J.G., Reyes P.W.C., Kuruchittham V., Ho R.C. Psychological impact of COVID-19 pandemic in the Philippines. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2020;277:379–391. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.08.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thakur V., Jain A. COVID 2019-suicides: A global psychological pandemic. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. 2020;88:952. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Timms C., Brough P., O'Driscoll M., Kalliath T., Siu O.L., Sit C., Lo D. Flexible work arrangements, work engagement, turnover intentions and psychological health. Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources. 2015;53(1):83–103. [Google Scholar]

- Trevor C.O., Nyberg A.J. Keeping your headcount when all about you are losing theirs: Downsizing, voluntary turnover rates, and the moderating role of HR practices. Academy of Management Journal. 2008;51(2):259–276. [Google Scholar]

- Uludag O., Olufunmi Z.O., Lasisi T.T., Eluwole K.K. Women in travel and tourism: Does fear of COVID-19 affect women's turnover intentions? Kybernetes. 2022 (ahead-of-print) [Google Scholar]

- Urbanaviciute I., Lazauskaite-Zabielske J., Vander Elst T., De Witte H. Qualitative job insecurity and turnover intention: The mediating role of basic psychological needs in public and private sectors. Career Development International. 2018;23(3):274–290. [Google Scholar]

- Usman M., Ali Y., Riaz A., Riaz A., Zubair A. Economic perspective of coronavirus (COVID‐19) Journal of Public Affairs. 2020;20(4) doi: 10.1002/pa.2252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uzun N.D., Tekin M., Sertel E., Tuncar A. Psychological and social effects of COVID-19 pandemic on obstetrics and gynecology employees. Journal of Surgery and Medicine. 2020;4(5):355–358. [Google Scholar]

- Van den Broeck A., Lens W., De Witte H., Van Coillie H. Unraveling the importance of the quantity and the quality of workers' motivation for well-being: A person-centered perspective. Journal of Vocational Behavior. 2013;82(1):69–78. [Google Scholar]

- Vigoda-Gadot E., Eldor L., Schohat L.M. Engage them to public service: Conceptualization and empirical examination of employee engagement in public administration. The American Review of Public Administration. 2013;43(5):518–538. [Google Scholar]

- Williams R.D., Shah A., Tikkanen R., Schneider E.C., Doty M.M. The Commonwealth Fund; 2020. Do Americans face greater mental health and economic consequences from COVID-19? Comparing the US with other high-income countries. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank . 2020. COVID‐19 forced businesses in Ghana to reduce wages for over 770,000 workers and caused about 42,000 layoffs‐research reveals. [Google Scholar]

- Wynne R., Davidson P.M., Duffield C., Jackson D., Ferguson C. Workforce management and patient outcomes in the intensive care unit during the COVID‐19 pandemic and beyond: A discursive paper. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2021 doi: 10.1111/jocn.15916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xanthopoulou D., Bakker A.B., Demerouti E., Schaufeli W.B. The role of personal resources in the job demands-resources model. International Journal of Stress Management. 2007;14(2):121. [Google Scholar]

- Xanthopoulou D., Bakker A.B., Demerouti E., Schaufeli W.B. Reciprocal relationships between job resources, personal resources, and work engagement. Journal of Vocational Behavior. 2009;74(3):235–244. [Google Scholar]

- Yu H.H. Work-life balance: An exploratory analysis of family-friendly policies for reducing turnover intentions among women in US federal law enforcement. International Journal of Public Administration. 2019;42(4):345–357. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M., Zhang D. A study on the factors influencing voluntary turnover in IT companies. China Soft Science. 2003;5(3):76–80. [Google Scholar]