Abstract

N6-Methyladenosine (m6A) RNA modification, methylation at the N6 position of adenosine, plays critical roles in tumorigenesis. m6A readers recognize m6A modifications and thus act as key executors for the biological consequences of RNA methylation. However, knowledge about the regulatory mechanism(s) of m6A readers is extremely limited. In this study, RN7SK was identified as a small nuclear RNA that interacts with m6A readers. m6A readers recognized and facilitated secondary structure formation of m6A-modified RN7SK, which in turn prevented m6A reader mRNA degradation from exonucleases. Thus, a positive feedback circuit between RN7SK and m6A readers is established in tumor cells. From findings on the interaction with RN7SK, new m6A readers, such as EWS RNA binding protein 1 (EWSR1) and KH RNA binding domain containing, signal transduction-associated 1 (KHDRBS1), were identified and shown to boost Wnt/β-catenin signaling and tumorigenesis by suppressing translation of Cullin1 (CUL1). Moreover, several Food and Drug Administration-approved small molecules were demonstrated to reduce RN7SK expression and inhibit tumorigenesis. Together, these findings reveal a common regulatory mechanism of m6A readers and indicate that targeting RN7SK has strong potential for tumor treatment.

Keywords: m6A methylation, RN7SK, m6A readers, regulatory mechanism, tumorigenesis

Graphical abstract

Xin Xu et al. reveal that RN7SK snRNA and m6A readers establish a positive feedback circuit, which is essential for tumorigenesis. As per such a close relationship, new m6A readers can be discovered. Also, evidence has demonstrated that targeting RN7SK possess strong potential to treat against tumors.

Introduction

Methylation at the N6 position of adenosine, N6-methyladenosine (m6A) modification, is the most common form of RNA modification.1 m6A is enriched in the conserved consensus sequence RRACH (R = G or A; H = A, C, or U)2 and mainly modulates transcription, splicing, processing, translation, and stability of modified RNA.3,4,5,6,7 The m6A modification system includes methyltransferases, demethylases and methylation recognition proteins known as “writers,” “erasers,” and “readers,” respectively. While writers and erasers are required for m6A methylation, the biological consequence of m6A modification is ultimately executed by readers through their specific recognition of m6A-modified RNAs and influence on subsequent gene expression.8

m6A readers are divided into several families. The YT521-B homology (YTH) m6A reader family proteins, which include YTHDC1/2 and YTHDF1/2/3, contain a YTH domain9 and modulate mRNA maturation, translation, and decay.10 Insulin-like growth factor 2 mRNA binding proteins (IGF2BPs) belong to another family, and IGF2BP1/2/3 serve as posttranscriptional regulatory factors for mRNA stability.11 Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoproteins (HNRNPs), including HNRNPC and HNRNPA2B1, are active splicing regulators that correlate with m6A methylation.12 Fewer than 20 m6A readers have been identified thus far, and the upstream regulatory mechanism(s) that regulate m6A readers remain elusive.

Emerging studies have demonstrated a critical role for m6A RNA methylation in various types of tumors, including lung, liver, and colorectum tumors.13,14,15 Abnormality of m6A methylation has been linked with the occurrence, progression, metastasis, drug resistance, and recurrence of tumors.16 Multiple studies have elucidated the downstream effects of several m6A readers in tumor cells.17,18,19 However, while the importance of m6A readers in tumor cells has been established and new m6A readers are being discovered, comprehensive studies investigating new m6A readers in tumor cells are lacking.

Small nuclear RNAs (snRNAs) are small RNAs with a length of approximately 100–300 nt that are located in the nucleus of eukaryotic cells.20 snRNAs interact with proteins to form small nuclear ribonucleoprotein (snRNP) particles, which constitute the main component of the RNA spliceosome and participate in the post-transcriptional processing of RNA precursors.21 Many studies have showed that snRNAs are expressed at a high level in tumors.22 However, whether snRNA regulates tumorigenesis through regulation to m6A readers is extremely limited.

In this study, we investigated the regulatory mechanism(s) of m6A readers and explored a method to identify new m6A readers in tumor cells. We found that m6A readers associated with and facilitated the secondary structure of m6A-methylated RN7SK snRNA, which sustains RNA stability and expression of m6A reader mRNA, representing a positive feedback circuit between RN7SK and m6A readers. From the association with RN7SK, new m6A readers, including EWSR1 and KHDRBS1, were identified and shown to boost Wnt/β-catenin signaling and tumorigenesis.

Results

The RN7SK snRNA associates with m6A readers

To explore the general mechanism(s) that regulate m6A readers, we investigated RNAs that interact with m6A readers by comparing publicly available transcriptomic RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) data generated from RNA immunoprecipitation (RIP) or crosslinking immunoprecipitation experiments using antibodies against well-established m6A readers (Figures S1A–S1J). Only RN7SK, an snRNA, was identified to interact with all the tested m6A readers (Figure 1A). RN7SK is transcribed from a continuous region located within chromosome 6, and PCR products encompassing this region were amplified using both gDNA and cDNA templates (Figure 1B). In contrast, an upstream genomic region was only amplified from a gDNA template, verifying that RN7SK RNA concentration can be reflected in our detection system.

Figure 1.

RN7SK is associated with m6A readers

(A) Overlap of associated RNA with m6A readers. (B) Chromosome location of UGR and RN7SK and their expression in tumor cell lines. (C–I) IF evaluation of RN7SK and indicated m6A readers in A549 and Bel-7402 cells; data were quantified using ScatterJ analysis in ImageJ software. ADRA1A was examined as a negative control. Pearson’s correlation coefficient for co-localization was used between RN7SK and the indicated m6A reader. Pearson’s correlation coefficient R value from 0.5 to 1 indicates positive co-localization, and an R value less than 0.5 indicates little co-localization. (J and K) E14–E16 embryos from WT, Rn7sk+/−, and Rn7sk−/− mice. The images and weights of embryos (J) and Rn7sk and Igf2bp3 expression (K) are shown. (L and M) The images and weights of WT, Igf2bp3+/−, and Igf2bp3−/− mice (L) and Rn7sk and Igf2bp3 expression (M) are shown. (N and O) 3D spheroid generation of A549 cells with or without KO of RN7SK (N) or IGF2BP3 (O). The spheroid number and size are also shown. Scale bar, 100 μm. (P) RN7SK expression in tumorous and adjacent tissues from LUAD patients. (Q) Overall survival of LUAD patients with higher or lower expression of RN7SK. Statistical analysis was performed by one-way ANOVA (J–O), t test (P), or log rank test (Q). Data are presented as means ± SD from indicated samples or experiments; n = 3 for (J–M) and n = 5 for (N and O). ∗∗p < 0.01.

RN7SK was ubiquitously expressed in tumor cells (Figure 1B), suggesting that it may play a role in tumorigenesis. RN7SK was highly expressed in lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD) A549 and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) Bel-7402 cells (Figure 1B), and thus these two cell lines were chosen for subsequent studies. Immunofluorescence (IF) revealed the co-localization of RN7SK and m6A readers in A549 and Bel-7402 cells, supporting the potential RN7SK-m6A reader interactions (Figures 1C–1I and S1K–S1L).

m6A readers are classified into groups depending on the reading domain,9,11 and IGF2BP and YTH are two major m6A reader families. Dysregulations of IGF2BP and YTH m6A readers were observed in approximately 12.9%–88.24% of tumors (Figure S2A). YTHDC2 shows a close association with other m6A readers, while IGF2BP2 and IGF2BP3 are relatively independent from other m6A readers (Figure S2B). In addition, IGF2BP3 and YTHDC2 ranked first among their corresponding m6A reader families in terms of clinical significance (Figure S2A). Thus, IGF2BP3 and YTHDC2 were selected as two representative IGF2BP and YTH family members for subsequent experiments.

To examine whether RN7SK function is related to that of the m6A readers, we evaluated the functions of IGF2BP3 and RN7SK in vivo. Knocking out Rn7sk in mice was lethal, and thus we evaluated E14–E16 embryos from WT, Rn7sk+/−, and Rn7sk−/− mice. The weights of mice were Rn7sk dependent (Figures 1J and 1K) and the sizes of adult mice were Igf2bp3 dependent (Figures 1L and 1M). In vitro A549 and Bel-7402 cell-based experiments also demonstrated that RN7SK and IGF2BP3 stimulated 3D spheroid generation (Figures 1N, 1O, S2C, and S2D). These results demonstrated that the functions of RN7SK and IGF2BP3 may be related and that RN7SK and m6A readers are both essential in development and tumorigenesis. Notably, when Rn7sk positively regulated Igf2bp3 expression, Igf2bp3 also influenced Rn7sk level (Figures 1K and 1M), suggesting that Rn7sk and Igf2bp3 are mutually regulated.

In addition, RN7SK was upregulated in LUAD tumorous tissues compared with adjacent normal tissues (Figure 1P), and higher RN7SK expression was associated with poorer survival outcome in LUAD patients (Figure 1Q), demonstrating that RN7SK also plays a critical role in tumor progression. Together, a close RN7SK-m6A readers association was once again confirmed.

m6A readers recognize m6A-methylated RN7SK and facilitate RN7SK secondary structure formation

We found that the KH3-4 and YTH m6A reading domains of IGF2BP3 and YTHDC2, respectively, were essential for RN7SK-m6A reader interactions (Figures 2A, 2B, S3A, and S3B). Because m6A readers recognize and interact with m6A-methylated RNA,8 we hypothesized that RN7SK may be m6A methylated. Our results confirmed this hypothesis (Figures 2C and S3C). Moreover, RN7SK-m6A reader interactions were reinforced by increasing global m6A methylation by overexpressing the m6A writer METTL3 and dissociated by reducing global m6A methylation by knocking out METTL3 in A549 cells (Figures 2D and S3D–S3F). We further compared Igf2bp3-Rn7sk and Ythdc2-Rn7sk interactions in E14–E16 embryos from WT, Mettl3+/−, and Mettl3−/− mice and found that Rn7sk-m6A reader interactions were dependent on Mettl3 in vivo (Figures 2E–2G). Together, these findings indicate that m6A methylation of RN7SK is a prerequisite for RN7SK-m6A reader interactions.

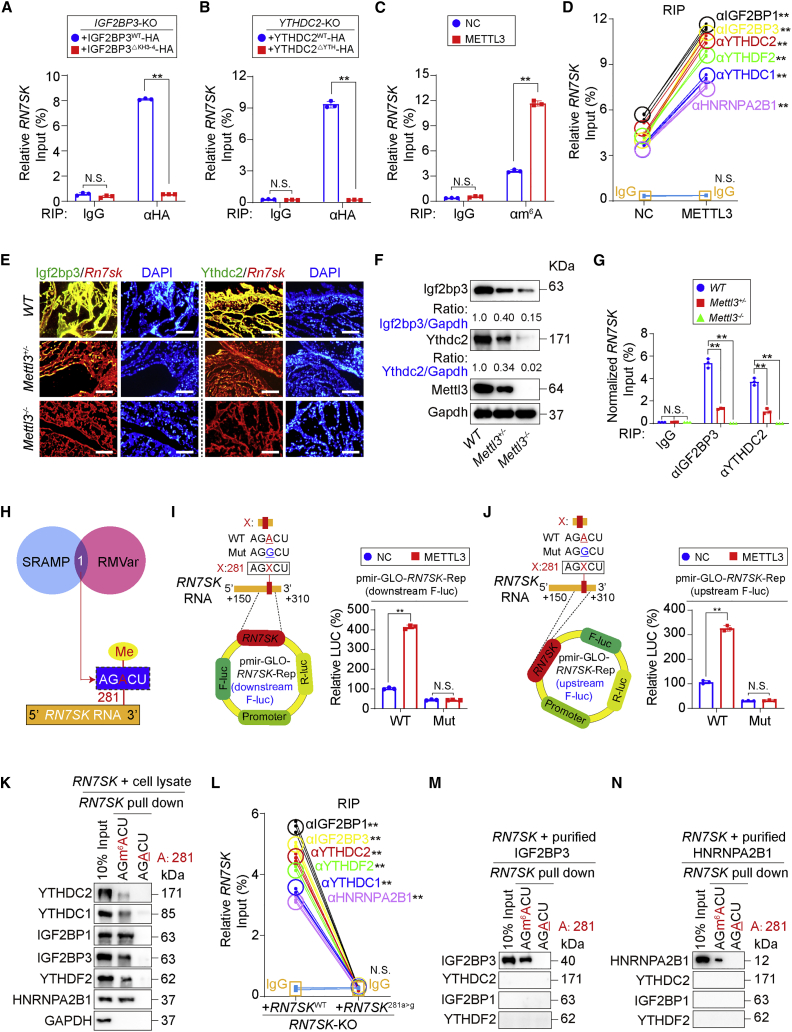

Figure 2.

m6A methylation of RN7SK

(A and B) IGF2BP3-KO A549 cells were reconstituted with IGF2BP3-HA with or without the KH3-4 domain (A) and YTHDC2-KO A549 cells were reconstituted with YTHDC2-HA with or without the YTH domain (B). RIP was performed using anti-HA antibodies, and the enrichment of RN7SK was tested by qPCR. IgG control antibodies were used as controls. (C) m6A methylation of RN7SK was evaluated by RIP using anti-m6A antibodies in A549 cells with or without METTL3 overexpression. IgG antibodies were used as negative controls. (D) RIP experiments using IgG and antibodies against indicated m6A readers in A549 cells with or without overexpression of METTL3. (E) Co-localization of Igf2bp3 with Rn7sk and Ythdc2 with Rn7sk in embryos from WT, Mettl3+/−, and Mettl3−/− mice, as measured by IF. Scale bar, 100 μm. (F) Igf2bp3 and Ythdc2 expression in WT, Mettl3+/−, and Mettl3−/− mice. The ratios of Igf2bp3 and Ythdc2 to Gapdh are indicated below the blots. (G) RIP using anti-Igf2bp3 and anti-Ythdc2 antibodies in WT, Mettl3+/−, and Mettl3−/− embryos. Because both Igf2bp3 and Ythdc2 were downregulated following loss of Mettl3, considering downregulation of Igf2bp3 and Ythdc2, we artificially adjusted their amounts to the same level by multiplying the reciprocal of the reduced ratio to Gapdh as indicated in (F) during analysis in RIP experiments. (H) Potential m6A site in RN7SK predicted by SRAMP and RMVar online software. (I and J) WT or mutant RN7SK was cloned downstream (I) or upstream (J) of the firefly luciferase reporter gene in pmir-GLO plasmids, and luciferase activity was measured in A549 cells with or without METTL3 overexpression. (K) RNA pull-down following incubation of RN7SK probes with or without m6A methylation with A549 cell lysate for the detection of m6A readers. (L) RIP using IgG and antibodies against m6A readers in RN7SK-KO A549 cells reconstituted with RN7SKWT or RN7SK281a>g. (M and N) Purified IGF2BP3 (M) and HNRNPA2B1 (N) were incubated with RN7SK probes with or without m6A methylation in vitro before performing RN7SK pull-down experiments. Statistical analysis was performed by t test (A–D, I, J, and L) or one-way ANOVA (G). Data are presented as means ± SD from three independent experiments. ∗∗p < 0.01, and N.S. indicates non-significance.

We next used SRAMP23 and RMVar24 online software and found that adenosine at 281 was a putative m6A-methylated site in RN7SK (Figure 2H). Luciferase reporter assays are commonly used to evaluate the functional consequences of m6A-methylated site(s) by cloning RNA region of interest downstream of the firefly luciferase gene in luciferase reporter vectors.25,26,27 However, because RN7SK is a non-coding RNA, it is hard to margin functional region. Thereby, to avoid bias, we constructed two kinds of RN7SK luciferase reporters: one contains RN7SK downstream of the firefly luciferase gene (Figure 2I), and another contains RN7SK upstream of the luciferase gene (Figure 2J). Results from both reporters confirmed that a281 was METTL3 associated (Figures 2I and 2J). RNA pull-down experiments following incubation of A549 cell lysate with RN7SK probes demonstrated that m6A methylation at a281 was essential for m6A readers to interact with RN7SK (Figure 2K). By reconstituting RN7SK-KO A549 cells with WT or 281a>g mutated RN7SK followed by RIP experiments using antibodies against m6A readers, we found that a281 was required for RN7SK-m6A reader interactions (Figure 2L). To exclude indirect interactions between RN7SK-m6A readers, purified IGF2BP3 and HNRNPA2B1 were incubated with RN7SK probes in vitro, followed by RNA pull-down experiments. We found that IGF2BP3 and HNRNPA2B1 only bound RN7SK with m6A modification at a281 (Figures 2M and 2N). These results indicate that a281 represents a functional m6A site in RN7SK. Notably, overexpressing either IGF2BP3 or YTHDC2 prevented binding of other m6A readers to RN7SK (Figures S3G and S3H), further revealing a competitive mode for the RN7SK-m6A reader interactions.

We next explored the functional consequence of m6A methylation of RN7SK at a281. Analysis using an RNA secondary structure prediction tool RNAstructure28 identified a stem-loop RN7SK secondary structure (Figure 3A). To visualize the degree of secondary structure formation (SSF) using IF experiments, a Cy3-labeled probe (red) specifically recognizing the large central loop and a FAM-labeled probe (green) targeting a linear stem part of RN7SK were designed. In principle, with the increasing formation of the secondary structure, the overlap of Cy3 and FAM also increases (resulting in a yellow signal) (illustrated in Figure 3B). We found that overexpressing METTL3 significantly increased the proportion of yellow A549 cells while knocking out METTL3 decreased the yellow signal (Figures 3C–3H). Furthermore, without an intact a281, the SSF was almost diminished (Figure 3I). These data suggested that a281 and its m6A methylation is a prerequisite for RN7SK SSF. The influences of m6A readers on SSF were also evaluated. Deleting the KH3-4 and YTH domain of IGF2BP3 and YTHDC2, respectively, reduced SSF (Figures 3J and 3K). Together, these findings indicate that m6A methylation of RN7SK at a281 is required for m6A reader recognition to form a RN7SK secondary structure (Figure 3L).

Figure 3.

m6A methylation boosted secondary structure formation of RN7SK

(A) Secondary structure of RN7SK, as revealed by RNA structure. (B) Schematic presentation of the detection of secondary structure formation (SSF) of RN7SK in IF experiments. (C) METTL3 overexpression in A549 cells. (D and E) SSF of RN7SK in A549 cells with or without METTL3 overexpression. Scale bars, 100 μm (white) and 20 μm (orange). (F) METTL3-KO in A549 cells. (G and H) SSF of RN7SK in A549 cells with or without METTL3-KO. Scale bars, 100 μm (white) and 20 μm (orange). (I–K) SSF of RN7SK in RN7SK-KO A549 cells reconstituted with RN7SKWT or RN7SK281a>g (I) or in IGF2BP3-KO A549 cells reconstituted with IGF2BP3WT or IGF2BP3ΔKH3-4 (J) or in YTHDC2-KO A549 cells reconstituted with YTHDC2WT or YTHDC2ΔYTH (K) as measured by IF. (L) Schematic presentation showing that m6A methylation of RN7SK at adenosine 281 is critical for SSF of RN7SK. Statistical analysis was performed by t test (E and H–K). Data are presented as means ± SD from three independent experiments. ∗∗p < 0.01, and N.S. indicates non-significance.

RN7SK sustains m6A reader mRNAs by inhibiting RNA exonucleases

We next evaluated whether RN7SK influences m6A readers following SSF. We compared the levels of m6A readers in A549 and Bel-7402 cells with RN7SK knockout (KO) or overexpression and controls and observed that RN7SK positively regulates m6A readers both at protein and mRNA levels (Figures 4A, 4B, and S4A–S4F). Because of the importance of a281 in SSF of RN7SK, we wondered whether destruction of SSF impairs the ability of RN7SK to influence m6A reader levels. Indeed, mutation of a281 remarkably reduced m6A reader mRNA levels in A549 and Bel-7402 cells (Figures 4C and S4G). Furthermore, we found that RN7SK, especially a281, plays critical roles to retard the decay of m6A reader mRNA (Figures 4D and 4E). These results suggest that SSF is required for RN7SK to sustain the expression and stability of m6A reader mRNA.

Figure 4.

SSF was essential for RN7SK to upregulate m6A readers

(A and B) Protein (A) and mRNA (B) expression of m6A readers in A549 cells with KO of RN7SK and controls. (C) mRNA expression of m6A readers in RN7SK-KO A549 cells reconstituted with RN7SKWT or RN7SK281a>g. (D) Heatmap showing actinomycin D chase experiments for m6A reader mRNA in A549 cells with RN7SK-KO and controls. (E) Heatmap showing actinomycin D chase experiments for m6A reader mRNA in RN7SK-KO A549 cells reconstituted with RN7SKWT or RN7SK281a>g. (F) mRNA of m6A readers in A549 cells overexpressing XRN2 or EXOSC5 and controls in the presence or absence of RN7SKWT or RN7SK281a>g. (G) Schematic model for the function of secondary structure of RN7SK to absorb and inhibit XRN and EXOSC to degrade m6A reader mRNAs. (H) RIP experiments using antibodies against XRN2 and EXOSC5 and IgG in RN7SK-KO A549 cells reconstituted with RN7SKWT or RN7SK281a>g and with or without METTL3 overexpression. (I and J) RIP experiments using IgG and antibodies against XRN2 (I) or EXOSC5 (J) in A549 cells with or without METTL3 overexpression for the detection of associated m6A reader mRNA. (K) Xrn2-Rn7sk and Exosc5-Rn7sk co-localizations in WT or Mettl3−/− MEF cells, as measured by IF and quantified using ScatterJ analysis in ImageJ software. Pearson’s correlation coefficient for fluorescent co-localizations between Rn7sk and Xrn2 or Exosc5 was determined. Statistical analysis was performed by one-way ANOVA (B and F), t test (C and H–J), or two-way ANOVA (D and E). Data are presented as means ± SD from three independent experiments. ∗∗p < 0.01, and N.S. indicates non-significance.

We next investigated the mechanism underlying how RN7SK sustains the mRNA stability of m6A readers. Exonucleases, such as XRN and EXOSC, are responsible for RNA degradation.29,30 We found that RN7SK was insensitive to XRN2 and EXOSC5, which were used as representative exonucleases (Figure S5A), suggesting that RN7SK is an independent regulator involved in exonuclease-participated regulation of m6A reader mRNA. Overexpressing XRN2 and EXOSC5 caused reduction of m6A reader mRNA, and this was partially reversed by simultaneously overexpressing RN7SK; however, these effects were diminished when a281 was mutated (Figure 4F). In addition, a281 in RN7SK was required for preventing exonuclease-mediated reduction of IGF2BP3 and YTHDC2 mRNA stability (Figures S5B and S5C). These data indicated that SSF is critical for RN7SK to prevent exonuclease-mediated degradation of m6A reader mRNA.

We next speculated whether SSF of RN7SK competitively absorbs XRN and EXOSC and thus separates exonucleases to inhibit their functions to degrade m6A reader mRNA (hypothesis shown in Figure 4G). To address this possibility, RIP was performed in A549 cells expressing RN7SK with or without 281a>g mutation. We found that METTL3 overexpression stimulated XRN2- and EXOSC5-RN7SK interactions in RN7SKWT-expressing A549 cells; however, no effects were observed in RN7SK281a>g-expressing cells (Figure 4H), suggesting that m6A methylation-stimulated SSF of RN7SK is essential for absorbing exonucleases. In contrast, METTL3 overexpression and KO experiments demonstrated that m6A methylation attenuated exonuclease-m6A reader mRNA associations (Figures 4I, 4J, S5D, and S5E). In addition, Xrn2- and Exosc5-Rn7sk interactions were markedly weakened in Mettl3−/− mouse embryonic fibroblast (MEF) cells compared with WT MEF cells (Figures 4K and S5F). These results indicate that m6A methylation-stimulated SSF of RN7SK enables RN7SK absorb to exonucleases and prevent their functions to degrade m6A reader mRNA.

To further confirm the roles of RN7SK and exonucleases to regulate m6A reader mRNA, XRN2, and EXOSC5 were suppressed by siRNA in A549 RN7SK-KO cells. RN7SK-KO-induced downregulation of m6A reader mRNA was partially rescued following inhibition of XRN2 and EXOSC5 (Figure S5G). We next examined whether RN7SK also regulates other mRNAs and found that RN7SK-KO resulted in only slightly downregulated Solute carrier family 3 member 2 (SLC3A2), Yes1-associated transcriptional regulator (YAP1), and Ferritin heavy chain 1 (FTH1) mRNAs (Figure S5H). Notably, XRN2 and EXOSC5 shortened the half-lives of SLC3A2 and YAP1 mRNA to a lesser extent compared with that of IGF2BP3 and YTHDC2 mRNA (Figures S5B, S5C, and S5I), suggesting that RN7SK-specific regulation of m6A readers might depend on exonucleases. Moreover, IP results using anti-XRN2 and anti-EXOSC5 antibodies (Figure S5J) combined with the results from Figure 2 indicated that RN7SK, exonuclease, and m6A readers form one complex, which might facilitate tumorigenesis. Finally, m6A readers were found mutually regulated, although slightly, but RN7SK dependently (Figures S5K and S5L). These results further supported a close and important feedback regulation between RN7SK and m6A readers.

Identification of new readers from interactions with RN7SK

To obtain a more comprehensive understanding of RN7SK’s function, we investigated other potential RN7SK-associated m6A readers. Because m6A readers recognize m6A-methylated RN7SK (Figure 2), and RN7SK sustains levels of m6A reader mRNAs (Figure 4), we performed proteomics following RNA pull down of m6A-methylated RN7SK and RNA-seq before and after KO of RN7SK. Forty new m6A readers and three established m6A readers, IGF2BP2, IGF2BP3, and HNRNPA2B1, were identified to interact with m6A-methylated RN7SK and showed downregulation following KO of RN7SK (Figure 5A).

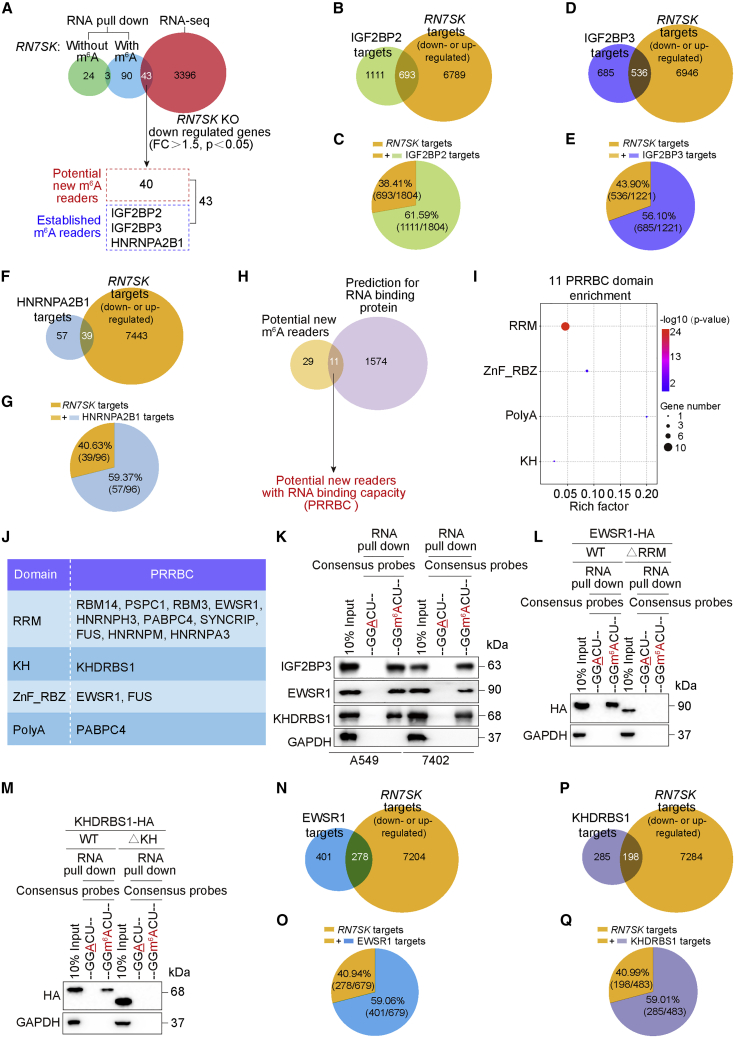

Figure 5.

New readers were identified from interactions with RN7SK

(A) Venn diagram showing the workflow for identifying m6A readers using RNA pull-down experiments followed by proteomics and conventional RNA-seq. (B–G) Venn diagram shows the overlap between targets of IGF2BP2 (B), IGF2BP3 (D), HNRNPA2B1 (F), and RN7SK. The percentages of the overlap targets are illustrated (C, E, and G). (H) Venn diagram showing the numbers of potential new m6A readers that also have RNA binding capacity as predicted by RBPDB database. (I) Domain enrichments for 11 PRRBCs, as predicted by ToppGene Suite and SMART. (J) Sorting of PRRBCs by RNA-binding domains. (K) RNA pull-down experiments were performed followed by incubation of m6A consensus probes with or without m6A methylation with lysates from A549 and Bel-7402 cells. (L and M) RNA pull-down experiments were performed by m6A consensus probes with or without m6A methylation using lysates of A549 cells expressing EWSR1-HA (L) or KHDRBS1-HA (M) with or without the corresponding m6A reading domain. (N–Q) Venn diagram showing the overlap between targets of EWSR1 (N), KHDRBS1 (P) and RN7SK. The percentages of the overlap targets are illustrated (O and Q).

To explore whether these newly identified proteins are genuine m6A readers, we compared the targets of the three established m6A readers and RN7SK. The targets of the three established m6A readers were identified on the basis of whether they were m6A methylated, regulated by m6A readers, or interact with m6A readers. Through analysis of publicly available RIP and high-throughput sequencing (RIP-seq), enhanced crosslinking immunoprecipitation and high-throughput sequencing (eCLIP-seq), photoactivatable ribonucleoside-enhanced crosslinking immunoprecipitation and high-throughput sequencing (PARCLIP-seq), RNA-seq, and methylated RIP sequencing (MeRIP-seq/m6A-seq) data, 1,804 IGF2BP2, 1,221 IGF2BP3, and 96 HNRNPA2B1 targets were identified (Figures S6A–S6C). A total of 7,482 RN7SK targets were also revealed by RNA-seq (Figures 5B, 5D, and 5F). Notably, 38.41% (693/1804), 43.90% (536/1,221), and 40.63% (39/96) of the targets of IGF2BP2, IGF2BP3, and HNRNPA2B1, respectively, overlapped with those of RN7SK (Figures 5B–5G). From the high degree of compliance for the targets between RN7SK and the three established m6A readers, these results strongly suggested that the RN7SK-based strategy to identify new m6A readers is reliable.

We further studied the 40 candidate readers. By searching the RBPDB database of known RNA-binding proteins,31 we found that 11 of the 40 candidates are capable of binding RNA, and we thus named these as potential new m6A readers with RNA binding capacity (PRRBC) (Figure 5H). Domain enrichment analysis revealed that RNA recognition motif (RRM), K homology RNA-binding (KH) domain, ZnF_RBZ, and poly(A) were highly ranked domains among the 11 PRRBCs (Figure 5I).

We next examined whether the 11 PRRBCs are genuine m6A readers. Among the 9 RRM-containing PRRBCs, RNA binding motif protein 14 (RBM14), RNA binding motif protein 3 (RBM3), poly(A) binding protein cytoplasmic 4 (PABPC4), heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein H3 (HNRNPH3), synaptotagmin binding cytoplasmic RNA interacting protein (SYNCRIP), FUS RNA binding protein (FUS), heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein M (HNRNPM), and heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A3 (HNRNPA3) were previously reported as associated with m6A methylation.32,33,34,35 The other two proteins, paraspeckle component 1 (PSPC1) and EWS RNA binding protein 1 (EWSR1), were closely related with cancers.36,37,38 In the KH-containing PRRBC family, we only predicted KH RNA binding domain containing signal transduction-associated 1 (KHDRBS1) (Figure 5J). Of note, EWSR1 was a member of both RRM- and ZnF_RBZ-containing PRRBC families (Figure 5J). Because of the limited knowledge of EWSR1 and KHDRBS1 and the importance of EWSR1 in cancer, we selected these two PRRBCs for further study.

RNA pull-down experiment using probes containing the m6A consensus motif with or without m6A methylation demonstrated that, similar to the canonical m6A reader IGF2BP3, EWSR1, and KHDRBS1 have specific m6A reading functions (Figure 5K). Furthermore, the RRM domain within EWSR1 and the KH domain within KHDRBS1 were proven to be potential m6A reading domains (Figures 5L and 5M). We used a similar strategy to identify targets as described above and identified 679 EWSR1 and 483 KHDRBS1 targets (Figures S6D and S6E). Furthermore, 40.94% (278/679) and 40.99% (198/483) of EWSR1 and KHDRBS1 targets, respectively, overlapped with those of RN7SK (Figures 5N–5Q).

We next examined the relationship between the new m6A readers and RN7SK. We found that EWSR1 and KHDRBS1 protein levels were positively regulated by RN7SK (Figure S6F). The half-lives of EWSR1 and KHDRBS1 mRNAs were also prolonged by SSF of RN7SK because exonuclease-mediated mRNA degradation was effectively attenuated (Figures S6G–S6I). On the basis of the similarity to the established m6A readers (Figure 4), we proposed that the newly identified candidates are genuine m6A readers.

RN7SK activates Wnt/β-catenin signaling via EWSR1 and KHDRBS1

We next investigated the functions of the new m6A readers using EWSR1 and KHDRBS1 as examples. KEGG enrichment for the 52 common targets of EWSR1, KHDRBS1, and RN7SK revealed Wnt signaling as the top signaling pathway and four genes, CUL1, C-terminal binding protein 2 (CTBP2), protein kinase C alpha (PRKCA), and transducin beta-like 1 X-linked (TBL1X), were involved (Figures 6A and S7A). EWSR1 and KHDRBS1 bound the four targets, and their interactions were enhanced by METTL3 (Figure S7B), confirming that the RNA-binding capacity of EWSR1 and KHDRBS1 is m6A dependent.

Figure 6.

Newly identified m6A readers stimulated Wnt/β-catenin signaling by targeting CUL1

(A) KEGG enrichment for 52 common genes of EWSR1, KHDRBS1, and RN7SK. (B and C) Luciferase activities from pTOP- and pFOP-FLASH (B) and AXIN2 and SP5 mRNA expression (C) in A549 cells with EWSR1, KHDRBS1, or RN7SK-KO and controls. (D) Representative IB images of β-catenin and CUL1 in CUL1-KO A549 cells with or without EWSR1, KHDRBS1, or RN7SK-KO and controls. (E) CUL1 was evaluated by IB in A549 cells with EWSR1, KHDRBS1, or RN7SK-KO and controls treated with DMSO, CHX, or α-amanitin. (F) Translation efficiency of CUL1, as measured by the ratio between the levels of CUL1 protein and CUL1 mRNA, in A549 cells with or without EWSR1, KHDRBS1, or RN7SK-KO and controls. (G) Ribosome-associated CUL1 mRNA in A549 cells with or without EWSR1, KHDRBS1, or RN7SK-KO and controls. (H) Schematic representation of putative m6A sites within CUL1 mRNA, as predicted by SRAMP online software. (I) m6A methylation of CUL1 mRNA in A549 cells with or without METTL3 overexpression, as measured by RIP using anti-m6A antibodies. IgG was used as a negative control. (J) Schematic presentation of the construction of the pmir-GLO-CUL1-reporter. (K) Luciferase activities from pmir-GLO-CUL1-reporter containing WT or mutated a1164 CUL1 in A549 cells with or without EWSR1, KHDRBS1, or RN7SK-KO. (L) eIF3e enrichment within Cul1 mRNA, as measured by RIP using IgG or anti-eIF3e antibodies in MEF cells from WT, Mettl3−/−, and RN7SK−/− mice. Statistical analysis was performed by one-way ANOVA (B, C, F, G, I, K, and L). Data are presented as means ± SD from three independent experiments. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, and N.S. indicates non-significance.

We next explored whether Wnt signaling, which plays essential roles in tumorigenesis,39 was affected by RN7SK, EWSR1, and KHDRBS1. By examining luciferase activities from pTOP- and pFOP-FLASH reporters, which are used to assess the transcriptional activity of Wnt/β-catenin,40 and the mRNA levels of Axis inhibition protein 2 (AXIN2) and Sp5 transcription factor (SP5), two well-established Wnt targets, we found that RN7SK, EWSR1, and KHDRBS1 all stimulate Wnt activity (Figures 6B, 6C, S7C, and S7D). β-Catenin is a terminal effector of the canonical Wnt signaling, and CUL1 is a critical component of the ubiquitin E3 ligase to suppress β-catenin.41 Knockout of RN7SK, EWSR1, and KHDRBS1 caused downregulation of β-catenin and this process was dependent on CUL1 (Figure 6D). These results suggested that CUL1 is required for RN7SK and its associated m6A readers to modulate Wnt/β-catenin activity.

We next investigated how RN7SK and its associated-m6A readers inhibit CUL1. Knockout of RN7SK, EWSR1, and KHDRBS1 caused upregulation of CUL1 in A549 cells, and this was suppressed by cycloheximide (CHX), a translation inhibitor; however, it was unaffected by α-amanitin, a polymerase II transcription inhibitor (Figure 6E). These results demonstrated that RN7SK and its associated m6A readers suppress CUL1 at the translation level. Indeed, we found that RN7SK, EWSR1, and KHDRBS1 suppressed the translation efficiency of CUL1 mRNA in A549 cells (Figures 6F and S7C–S7E). We examined the association of CUL1 mRNA with the ribosome and found that the association of CUL1 mRNA to the polysome was induced by KO of RN7SK, EWSR1, and KHDRBS1, while it was reduced by overexpression of these factors (Figures 6G and S7F), further verifying the roles of RN7SK, EWSR1, and KHDRBS1 in suppressing CUL1 translation.

Because EWSR1 and KHDRBS1 are RN7SK-associated m6A readers, we examined whether CUL1 mRNA was m6A methylated. Two potential m6A sites, a1164 and a2597, in CUL1 mRNA were predicted by SRAMP (Figure 6H).23 RIP using anti-m6A antibodies demonstrated that the region around a1164 was METTL3 responsive and likely to be m6A methylated (Figure 6I). Using a luciferase reporter in which a partial CUL1 sequence containing a1164 was cloned upstream of the firefly luciferase gene (Figure 6J), we found that a1164 was a genuine m6A site and was regulated by RN7SK, EWSR1, and KHDRBS1 in A549 cells (Figures 6K and S7G).

Finally, we investigated whether m6A methylation and RN7SK affect translation of CUL1 in vivo. MEF cells were extracted from Mettl3−/− and Rn7sk−/− mice and compared with WT MEF cells. The enrichments of eIF3e, an essential translation initiation factor, to Cul1 mRNA were dramatically enhanced in the KO groups compared with the WT groups (Figure 6L). Taken together, these results indicate that m6A modification of CUL1 mRNA is critical for EWSR1, KHDRBS1, and RN7SK to suppress CUL1 translation.

The correlations among EWSR1, KHDRBS1, and RN7SK are critical for tumorigenesis

To explore the clinical significance of the current findings, we mined TCGA database and found that EWSR1 and KHDRBS1 were elevated in 11/24 cancer types (Figures 7A and 7B). Lung cancer, the leading cause of cancer-related death worldwide,42 was one of the cancer types. LUAD is the major histopathology subtype of lung cancer.43 Thus, we examined the roles of EWSR1, KHDRBS1, and RN7SK in LUAD. Higher EWSR1 and KHDRBS1 expression correlated with poorer overall survival in LUAD patients (Figures 7C and 7D). Their expressions were also associated with tumor progression (Figures S8A and S8B). The pro-tumorigenic roles of EWSR1 and KHDRBS1 were verified by 3D spheroid generation experiments and invasion assays (Figures 7E and S8C–S8E), and these functions were m6A reading domain dependent (Figures 7F, S8F, and S8G). These data suggested that EWSR1 and KHDRBS1, via their m6A reader functions, are important for tumorigenesis.

Figure 7.

Clinical significance of RN7SK-m6A reader interaction

(A and B) EWSR1 (A) and KHDRBS1 (B) expression in normal and indicated tumors; the data were analyzed using TCGA samples by the online UALCAN website. Bladder urothelial carcinoma (BLCA), breast invasive carcinoma (BRCA), cervical squamous cell carcinoma and endocervical adenocarcinoma (CESC), cholangiocarcinoma (CHOL), colon adenocarcinoma (COAD), esophageal carcinoma (ESCA), glioblastoma multiforme (GBM), head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSC), kidney chromophobe (KICH), kidney renal clear cell carcinoma (KIRC), kidney renal papillary cell carcinoma (KIRP), liver hepatocellular carcinoma (LIHC), lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD), lung squamous cell carcinoma (LUSC), pancreatic adenocarcinoma (PAAD), prostate adenocarcinoma (PRAD), pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma (PCPG), rectum adenocarcinoma (READ), sarcoma (SARC), skin cutaneous melanoma (SKCM), thyroid carcinoma (THCA), thymoma (THYM), stomach adenocarcinoma (STAD), and uterine corpus endometrial carcinoma (UCEC). (C and D) Overall survival in LUAD patients with higher or lower expression of EWSR1 (C) and KHDRBS1 (D). The data were analyzed using the Kaplan-Meier Plotter website. (E) 3D spheroid formation and cell invasion assays of A549 and Bel-7402 cells with or without EWSR1 or KHDRBS1 KO. Scale bars, 100 μm (white) and 100 μm (black). (F) 3D spheroid generation in A549 and Bel-7402 cells with or without EWSR1 or KHDRBS1 overexpression. EWSR1 and KHDRBS1 with or without m6A reading domain were tested in parallel. Scale bar, 100 μm. (G) RN7SK level in LUAD with lower or higher RN7SK expression. (H) Representative immunohistochemistry images of ERSR1, KHDRBS1, and CUL1 in LUAD with lower or higher expression of RN7SK. Scale bar, 200 μm. (I–K) Correlations between EWSR1 (I), KHDRBS1 (J), and CUL1 (K) with RN7SK in LUAD specimens (n = 202). Statistical analysis was performed by t test (A and B), or Pearson correlation analysis (I–K). ∗∗p < 0.01.

We next investigated the correlations among EWSR1, KHDRBS1, CUL1, and RN7SK in LUAD. We analyzed 202 LUAD specimens and found that, compared with LUADs with lower RN7SK expressing levels, LUADs with higher RN7SK were more likely to express higher levels of EWSR1 and KHDRBS1 and lower levels of CUL1 (Figures 7G and 7H). Moreover, RN7SK positively correlated with EWSR1 and KHDRBS1 (Figures 7I and 7J) but negatively correlated with CUL1 in LUAD (Figure 7K). These results hinted that the relationship among RN7SK, its associated m6A readers, and its targets may play an important role in LUAD.

Potential strategy to inhibit RN7SK and tumorigenesis

We next explored a strategy to effectively suppress RN7SK. We treated LUAD A549, HCC Bel-7402, and colon adenocarcinoma (COAD) HCT-116 cells with a drug library containing 1,800 FDA-approved small molecules and screened for those with powerful pan-inhibitory efficacy against RN7SK in multiple tumor cell lines. Five drugs, mitoxantrone (MIT), hydroxyurea (HYD), raltitrexed (RAL), oxaliplatin (OXA), and etoposide (ETO), were shown to inhibit RN7SK in A549, Bel-7402, and HCT-116 cells (Figures 8A and S9A–S9C). MIT and HYD were randomly chosen as representative drugs for further analysis. Like KO of RN7SK (Figure 4), both drugs effectively suppressed the levels of not only canonical m6A readers YTHDC2 and IGF2BP3 but also the newly identified m6A readers EWSR1 and KHDRBS1 (Figures 8B and 8C). In addition, the translation efficiency of CUL1 and Wnt activity was suppressed by MIT and HYD in A549 cells (Figures 8D and 8E). These results suggest that the use of small molecules targeting RN7SK may be a promising strategy for tumor treatment.

Figure 8.

Small molecules suppress RN7SK and tumorigenesis

(A) Workflow for screening a drug library containing 1,800 FDA-approved small molecules to identify drugs that downregulate RN7SK in A549, Bel-7402, and HCT-116 cells. (B and C) Protein (B) and RNA (C) levels of the indicated m6A readers in A549 cells treated with DMSO, MIT, or HYD. (D) Translation efficiency of CUL1 in A549 cells treated with DMSO, MIT, or HYD. (E) Luciferase activities from pTOP- and pFOP-FLASH reporters in A549 cells treated with DMSO, MIT, or HYD. (F and G) 3D spheroid generations in A549 cells treated with DMSO, MIT, or HYD. Representative images are shown in (F), and the data are graphed in (G). Scale bar, 100 μm. (H) RN7SK expression in LUSC-PDX with high or low RN7SK level treated with DMSO, MIT, or HYD. (I and J) Tumor growth of PDX in mice treated with DMSO, MIT, or HYD, as indicated. Representative images of PDX are shown in (I), and data are graphed in (J). n = 5/group. (K) RN7SK expression in RN7SK-KO A549 cells reconstituted with RN7SKWT or RN7SK281a>g following treatment with MIT or HYD. (L) RNA stability as measured by qPCR in A549 cells treated as indicated. (M) Schematic presentation of the proposed SMART model. Secondary structure formation (SSF) of RN7SK is facilitated by RN7SK mRNA m6A methylation and recognized by m6A readers. This action prevents m6A reader mRNA degradation by exonucleases. This illustrates a new feedback circuit between RN7SK and m6A readers. Through the relationship to RN7SK, new readers, such as EWSR1 and KHDRBS1, were identified and these readers may play critical roles to stimulate Wnt/β-catenin signaling and tumorigenesis via inhibiting translation of CUL1. Statistical analysis was performed by one-way ANOVA (C, D, E, G, H, and K) or two-way ANOVA (J and L). Data are presented as means ± SD from indicated samples or experiments; n = 3 for (C, D, E, K, and L) and n = 5 for (G, H, and J). ∗∗p < 0.01, and N.S. indicates non-significance.

Next, we investigated the influence of RN7SK on the effects of the small molecules to suppress tumorigenesis. Compared with results in control cells, increased suppression of 3D spheroid generation after treatment with the five drugs was observed in A549 cells overexpressing RN7SK (Figures 8F, 8G, and S9D–S9F). Patient-derived tumor xenografts (PDXs) are powerful models to explore the therapeutic efficacy of drugs. We used mouse models with PDX from lung squamous cell carcinoma (LUSC), another major type of lung cancer,33 and found that higher RN7SK expression led to a stronger tumor suppression caused by MIT and HYD (Figures 8I and 8J). These data suggest that tumors with higher RN7SK levels are prone to be suppressed following therapeutic treatment against RN7SK.

We further investigated how MIT and HYD suppress RN7SK expression and found that the 281a>g mutation in RN7SK prevented RN7SK expression and half-life from being reduced by MIT and HYD (Figures 8K and 8L), suggesting that m6A methylation and SSF of RN7SK are critical for drug efficacy. Finally, we evaluated whether non-tumor cells are also sensitive to MIT and HYD. Compared with LUAD A549 and H1299 cells, the BEAS-2B and 16HBE non-tumor human bronchial epithelial cell lines demonstrated less sensitivity to MIT and HYD (Figure S9G). These results suggest that RN7SK inhibitors may represent a safe approach for the treatment of cancer.

Discussion

snRNAs are a highly abundant small non-coding RNA located in the nucleus that are transcribed by RNA polymerase II or III and mainly function in the processing of mRNAs.44 snRNAs are not involved in protein synthesis, but they also interact with proteins to form snRNP particles to exert biological functions. Our findings demonstrated that m6A-methylated RN7SK is recognized by m6A readers, which facilitates SSF of RN7SK and enables it to absorb exonucleases and interfere with exonuclease function. This prevents degradation of m6A reader mRNAs and is essential for stimulating Wnt/β-catenin signaling and tumorigenesis. Therefore, here we present a model and positive feedback circuit regarding an snRNP formation by m6A reader and RN7SK to stimulate tumorigenesis (SMART) (Figure 8M).

Several studies have shown that some snRNP particles regulate migration, invasion and gene regulation in multiple tumor cell lines.45,46 However, the complete understanding of snRNP particles in tumors is still far from satisfactory. RN7SK is a 331 nt snRNA transcribed by RNA polymerase III.47 In cervical cancer cells, RN7SK interacts with high-mobility group AT-hook 1 (HMGA1) proteins to control polymerase II elongation by regulating the availability of active positive transcription elongation factor b.48 Here, our results indicate that snRNP particles have another role that is linked to m6A RNA methylation and interactions with m6A readers. Our findings also uncover a common regulatory mechanism to elevate m6A reader mRNA expression.

The secondary structure of RNA is important and closely linked to functions for mRNAs and non-coding RNAs, including snRNAs.49,50 When bound by RBPs, RNA secondary structures form higher-order tertiary structures and confer catalytic, regulatory and scaffolding functions.51 RNA secondary structure is also essential for RN7SK to absorb exonucleases and interfere with their functions to degrade m6A reader mRNA. Here, we provide evidence for a positive feedback circuit between RN7SK and m6A readers. RN7SK and m6A readers reinforce each other, resulting in activation of the downstream Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway and tumorigenesis. Given the importance of both RNA secondary structure and feedback circuit, attention should be focused on the interplay between snRNA and m6A RNA methylation.

In this study, we also developed a novel strategy to identify new m6A readers through the relationship with RN7SK. The m6A readers should meet two requirements: (1) interaction with m6A-methylated RN7SK and (2) upregulation by RN7SK. EWSR1 and KHDRBS1 are two examples of the newly identified m6A readers. EWSR1 belongs to the TAF15, EWS and TLS/FUS (TET) family, which include DNA/RNA-binding proteins.52 EWSR1 includes a conserved RRM in the C-terminal region53; it is ubiquitously expressed in almost all cell types and plays diverse roles in various cellular processes.53,54,55 This, to some extent, reflects the importance of m6A readers and RN7SK interactions. We also found that the RRM domain of EWSR1 is capable of m6A recognition, hence expanding the list of functional m6A reading domains. KHDRBS1, a member of the KH domain-containing RNA-binding signal transduction-associated protein family, plays versatile functions in an increasing number of cellular processes, including but not limited to RNA processing, transcription, cell-cycle regulation, tumorigenesis and apoptosis.56 The m6A reading function of KHDRBS1 and established IGF2 m6A reader family all rely on the KH domain, further confirming that KHDRBS1 is a genuine m6A reader. The mechanism underlying how EWSR1 and KHDRBS1 stimulate tumorigenesis was also investigated, and our findings demonstrate that the recognition of m6A-methylated CUL1 mRNA followed by suppression of CUL1 translation is essential for increasing Wnt/β-catenin activity. However, targeting Wnt/β-catenin may not be the only mechanism by which RN7SK and its associated m6A readers influence tumorigenesis. Future studies are required to explore their functions in cancer.

We also identified five FDA-approved small molecules that suppress RN7SK expression. MIT is a topoisomerase II inhibitor that has been used to treat various types of cancer either as a solo chemotherapy regimen or a component in cocktail treatments.57 HYD is a simple organic compound that is currently used as a cancer chemotherapeutic agent. It acts specifically on the S-phase of the cell cycle by inhibiting the enzyme ribonucleoside diphosphate reductase, thereby hindering the reductive conversion of ribonucleotides to deoxyribonucleotides and limiting de novo DNA synthesis.58,59 Here, we found that the efficacies of MIT and HYD rely on the secondary structure of RN7SK. We also found that in addition to suppressing DNA synthesis, MIT and HYD have other roles in accelerating RNA degradation. We speculate that the mechanism might involve the restructure of RN7SK and participation of RNA exonucleases. However, how MIT and HYD facilitate exonuclease function needs to be further investigated. Due to the specific recognition of the secondary structure of RN7SK and less harmful to non-tumor cells, our findings emphasize the efficacies of small molecules to inhibit tumorigenesis and provide a potential new strategy for treatment of tumors with high RN7SK and m6A methylation levels.

In conclusion, we found that m6A-methylated snRNA RN7SK forms a secondary structure after being recognized by m6A readers, which enables RN7SK to act as a sponge to absorb exonucleases and prevent m6A reader mRNAs from degradation. Our findings uncover a positive feedback circuit and common regulatory mechanism to upregulate m6A reader expression. We also show a useful strategy to identify new m6A readers and design novel anti-tumor strategies.

Materials and methods

Clinical specimens

We obtained 202 clinical samples of paired adjacent and LUAD tissue specimens from the Department of Biobank, Shanghai Chest Hospital, between January 2018 and December 2020. The patient information is listed in Table S1. Written informed consent was obtained from each patient, following the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. This study was approved by the institutional ethics committee of Shanghai Chest Hospital (approval number KS(Y)21380).

Cell culture

Human bronchial epithelial cell lines BEAS-2B and 16HBE, human lung cancer cell lines NCI-H1299, NCI-H1975, A549, and PC-9, human liver cancer cell lines Bel-7404, Bel-7402, and HepG2, human pancreatic cancer cell lines SW1990 and PANC-1, human gastric cancer cell lines MKN-45 and MGC-803, human COAD cell lines HCT-116 and HT29, and the human breast cancer cell line MCF-7 were purchased from FuHeng Biotechnology (Shanghai, China). All cell lines were validated by short tandem repeat analysis.

For conventional 2D cell culture, cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) (no. SH30243.1, HyClone, Logan, UT) with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (no. SH30084.03, HyClone) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (no. 15140122, Gibco, Grand Island, NY).

For 3D spheroid culture, 50 μL/well Basement Membrane Extract (no. 3432-005-01-60, Trevigen, MD) was added into a 96-well plate, and 10,000 cells were seeded in the plate. Culture medium was changed every 3 days. Spheroid number and size were calculated after 10 days culture using a microscope (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany).

Animal experiments

Igf2bp3−/− mice were generated by Cyagen Biosciences (Guangzhou, China). Rn7sk−/− mice were generated by GemPharmatech (Nanjing, China). Mettl3−/− mice were described in our previous study.26

For the generation of PDX mouse models, fresh LUSC specimens (2–3 mm3), which were from Shanghai Chest Hospital, were implanted into 4- to 6-week-old athymic nude mice (Jiesijie, Shanghai, China). After successful tumor growth was confirmed, the tumor tissues were passaged and implanted into the next generation of mice. The third to fifth generations of PDX-bearing mice were used for drug administration. When tumors reached approximately 200 mm3, mice were injected daily with DMSO (no. ST038, Beyotime Biotechnology, Shanghai, China) with or without MIT (no. S2485, 5 mg/kg, Selleck, Houston, TX) or HYD (no. S1896, 20 mg/kg, Selleck) (n = 5 mice/group). Tumor growth was monitored, and sizes were calculated by 0.5 × L × W2 (L indicating length and W indicating width). The mice were euthanized at day 28 after implantation. All animal experiments were approved by the institutional ethics committee of Shanghai Chest Hospital (approval number KS(Y)21380).

Preparation of MEF cells

After removal of the extracellular membranes of mouse embryos, the embryos were transferred to a dish containing D-PBS (no. 14190-144, Gibco) and finely chopped with a scalpel. The mixture was centrifuged at 4°C for 5 min, D-PBS was discarded, and the pellet was resuspended in trypsin (no. 25200-056, Gibco) at 37°C for 2 h. After filtration of the mixture through a nylon mesh, the cells were collected by centrifugation for 5 min and inoculated into culture flasks. Medium was replaced with fresh medium 24 h later.

Plasmids and drugs

RN7SK, IGF2BP3, EWSR1, KHDRBS1, and CUL1 single-guide RNAs (sgRNAs) were cloned into LentiCrisprV2 plasmids, which were obtained from our previous study.25RN7SKWT, RN7SK281a>g, IGF2BP3WT, IGF2BP3ΔKH3-4, and XRN2 plasmids were generated by Zuorun Biotech (Shanghai, China). Plasmids expressing EWSR1WT, EWSR1ΔRRM, KHDRBS1WT, and KHDRBS1ΔKH were generated by BioVision Technology (Shanghai, China). YTHDC2-KO, YTHDC2WT, YTHDC2ΔYTH, METTL3, and METTL3-KO plasmids were described in our previous study.51,52 The EXOSC5 plasmid was generated by GeneCopoeia (Guangzhou, China). siRNAs targeting XRN2 and EXOSC5 were purchased from GenePharma (Shanghai, China). The sequences of sgRNAs are listed in Table S2. In some experiments, cells were treated with CHX (10 μg/mL, no. C7698, Sigma, St. Louis, MO), α-amanitin (10 μg/mL, no. HY-19610, MedChemExpress, Monmouth, NJ), actinomycin D (ActD, 5 μg/mL, no. HY17559, MedChemExpress), MIT (1 μg/mL, no. S2485, Selleck), HYD (3 μg/mL, no. S1896, Selleck), RAL (2 μg/mL, no. S1192, Selleck), OXA (5 μg/mL, no. S1224, Selleck), or ETO (10 μg/mL, no. S1225, Selleck).

qRT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol reagent (no. 15590618, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and then reverse transcribed into cDNA using the HiScript III RT SuperMix (no. R333-01, Vazyme, Nanjing, China). qRT-PCR was performed using the HiScript II One Step qRT-PCR SYBR Green Kit (no. Q221-01, Vazyme), and GAPDH mRNA was used as an internal control. The sequences of primers are listed in Table S2.

Immunoblotting, immunohistochemistry, and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

For immunoblotting (IB), protein was extracted from cells or tissues using western and IP lysis buffer (no. P0013, Beyotime), and the protein concentration was measured using the BCA protein assay kit (no. P0010, Beyotime). Proteins were separated using SDS-PAGE gels and transferred onto polyvinylidene fluoride membranes (Pall, New York, NY) before blocking with 5% skim milk and 1% Tween 20 (Sigma) in PBS for 1 h. Membranes were then incubated with the following antibodies: anti-METTL3 (no. ab195352, Abcam, Cambridge, MA), anti-YTHDC1 (no. ab259990, Abcam), anti-YTHDC2 (no. ab176846, Abcam), anti-YTHDF2 (no. ab246514, Abcam), anti-IGF2BP1 (no. ab290736, Abcam), anti-IGF2BP3 (no. ab177477, Abcam), anti-HNRNPA2B1 (no. PA5-119190, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA), anti-HA (no. ab236632 or no. ab1424, Abcam), anti-EWSR1 (no. A9640, Abclonal), anti-KHDRBS1 (no. A6101, Abclonal), anti-β-catenin (no. ab32572, Abcam), anti-CUL1 (no. A2136, Abclonal), anti-YAP1 (no. ab52771, Abcam), anti-SLC3A2 (no. A5702, Abclonal), anti-FTH1 (no. A1144, Abclonal), or anti-GAPDH (no. 5174, CST, Boston, MA) at 4°C overnight. The membranes were then incubated with HRP anti-rabbit or -mouse antibodies (no. 7074S, no. 7076S, CST) at room temperature for 1 h. Bands were detected using ECL (no. E411-05, Vazyme, Nanjing, China) in the Bio-Rad GelDoc XR+ System (Bio-Rad).

For immunohistochemistry, the tissues were placed in an embedding box and fixed in neutral tissue fixative (no. G1101, Servicebio, Wuhan, China) at 4°C for 24 h. After dehydration in graded alcohol and clearing in xylene, the samples were embedded in paraffin. The slides were boiled in sodium citrate antigen retrieval buffer (no. P0081, Beyotime) at high temperature for 2 h after dewaxing with xylene and gradient alcohol. Next, 3% H2O2 (no. P0100A, Beyotime) was added in a dropwise manner to inactivate endogenous peroxidase. The slides were incubated overnight at 4°C with the following antibodies: anti-EWSR1 (no. A9640, Abclonal), anti-KHDRBS1 (no. A6101, Abclonal), and anti-CUL1 (no. A2136, Abclonal). On the second day, HRP anti-rabbit or -mouse antibodies (CST, no. 8114S, no. 8125S) were applied at room temperature for 60 min. A DAB developer kit (no. abs9210, Absin, Shanghai, China) was used for color development and counterstaining was performed with hematoxylin (no. C0107, Beyotime).

For enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), EWSR1, KHDRBS1, and CUL1 proteins were determined using ELISA kits from Yingxin Biotech (Shanghai, China) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. In brief, the proteins extracted from tissues were incubated with labeled antibodies provided by the kits, and the absorbance value was measured at the wavelength of 450 nm by a microplate reader (BioTek, Winooski, VT).

Fluorescence in situ hybridization and IF Cy3- or FAM-labeled human or mice RN7SK/Rn7sk probes were synthesized in vitro using a kit from Generay (Shanghai, China). Cells or tissues were fixed with a formamide-saline sodium citrate solution at 37°C for 4 h before incubation with fluorescent-labeled RN7SK/Rn7sk probes at 37°C overnight. The slides were then incubated with the following primary antibodies: anti-YTHDC1 (no. ab259990, Abcam), anti-YTHDC2 (no. ab176846, Abcam), anti-YTHDF2 (no. ab246514, Abcam), anti-IGF2BP1 (no. ab290736, Abcam), anti-IGF2BP3 (no. ab177477, Abcam), anti-HNRNPA2B1 (no. PA5-119190, Thermo Fisher Scientific), anti-ADRA1A (no. ab137123, Abcam), anti-XRN2 (no. A18350, Abclonal), and anti-EXOSC5 (no. A15870, Abclonal) at 4°C for another 12 h. Afterward, the slides were incubated with fluorescent-labeled secondary antibodies (no. 4412, CST) for 1 h at RT. Finally, nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (no. G1012, Servicebio). All images were obtained using a confocal microscope (Leica). The RN7SK/Rn7sk and protein overlap signals (yellow) were quantified and determined using ScatterJ analysis in ImageJ software. ScatterJ is often used for confirmation for specific molecule-molecule interactions. Pearson’s correlation coefficient for possible co-localization between two molecules was calculated in ScatterJ for representative cells; an R value from 0.5 to 1 and a value less than 0.5 indicated high and low possibility of co-localization, respectively. The calculations were repeated at least three times, and representative data are displayed in Figures 1 and S1. The sequences of probes are listed in Table S2.

Luciferase reporter assay

Regions encoding RN7SK (150–310 nt relative to the transcription start site) and CUL1 (1,000 –1,300 nt relative to the transcription start site) were inserted upstream or downstream of the firefly luciferase gene in the pmir-GLO luciferase reporter plasmid, which is often used to confirm putative m6A sites25,26,27; plasmids were generated by Zuorun Biotech. NheI and XbaI sits were used for downstream of firefly luciferase gene, and the upstream was generated by Zuorun Biotech, respectively. To determine Wnt activity, pTOP-FLASH and pFOP-FLASH luciferase reporter plasmids (available elsewhere) were used. Luciferase activities were detected by a dual luciferase reporter gene assay kit (Promega, Madison, WI). The firefly luciferase activities were normalized to Renilla luciferase activity.

m6A dot blot

Total RNA was isolated with TRIzol reagent (no. 15590618, Invitrogen) and denatured by heating at 100°C for 10 min, followed by chilling on ice. RNA was spotted on Biodyne Nylon Transfer Membranes (Pall) and crosslinked by 365 nm UVP for 10 min. The m6A level was measured using the anti-m6A antibody (no. 202003, Synaptic Systems, Goettingen, Germany) through IB.

RIP and RNA pull-down

For RIP experiments, a Magna RIP Kit (no. 17-700, Millipore, Billerica, MA) was used. In brief, lysates from cells cultured in 10 cm dishes were incubated with magnetic beads loaded with 5 μg of the following primary antibodies: anti-YTHDC1 (no. ab259990, Abcam), anti-YTHDC2 (no. ab176846, Abcam), anti-YTHDF2 (no. ab246514, Abcam), anti-IGF2BP1 (no. ab290736, Abcam), anti-IGF2BP3 (no. ab177477, Abcam), anti-HNRNPA2B1 (no. PA5-119190, Thermo Fisher Scientific), anti-HA (no. ab236632 or no. ab1424, Abcam), anti-m6A antibody (no. 202003, Synaptic Systems), or IgG (no. A7016 or no. A7028, Beyotime Biotechnology) at 4°C overnight. After proteinase K (no. ST535, Beyotime Biotechnology) digestion, the remaining RNA was purified using TRIzol reagent (no. 15590618, Invitrogen) and measured by qRT-PCR.

For RNA pull-down assays, biotin-labeled probes with or without artificial m6A methylation were synthesized by Tsingke Biotechnology (Beijing, China). Biotin-labeled RNA was incubated with cell lysates or purified IGF2BP3 (Chemstan, Wuhan, China) or HNRNPA2B1 (Chemstan) at 4°C overnight. Streptavidin magnetic beads (no. HY-K0208, MedChemExpress) were added to the reaction for 3 h. After washing, the enriched proteins were subjected to IB.

Mass spectrometry and transcriptomic RNA-seq

The mass spectrometry for the proteomics following RNA pull down of RN7SK was performed by Shanghai Applied Protein Technology (Shanghai, China). The mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium (http://proteomecentral.proteomexchange.org) via the iProX partner repository60 with the dataset identifier PXD033184, with accession number: VZTm (https://www.iprox.cn/page/PSV023.html;?url=16591549194360lnL, enter token VZTm). The RNA-seq experiments before and after KO of RN7SK were performed by Shanghai OE Biotech (Shanghai, China) and the data have been deposited to NCBI’s Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/)61 and are accessible through GEO Series accession number GSE20073, with accession number: wlepiaskfxmjzkd (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE200273, enter token wlepiaskfxmjzkd).

Measurements of mRNA decay

Cells were treated with ActD (no. HY17559, MedChemExpress, 5 μg/mL) and mRNA expressions were determined by qRT-PCR at the indicated times.

Assessing RNA association with ribosome

Cells were treated with CHX (10 μg/mL, Sigma) at 37°C for 15 min. Cells were harvested and lysed, and samples were centrifuged in a 10%–50% sucrose gradient for fractionation. Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol reagent (no. 15590618, Invitrogen) and subjected to qRT-PCR for the detection of CUL1 mRNA.

Cell proliferation and transwell invasion assays

Cell proliferation was analyzed by a CCK8 kit (no. G4103, Servicebio). Cells were added into 96-well plates (6 × 103 cells/well). After cell adhesion, reagents or drugs were added. The absorbance value at 450 nm was measured with the microplate reader (BioTek).

For invasion assays, transwell chambers (Costar, Corning, NY) were coated with Basement Membrane Extract (BME, Trevigen) on the upper membrane. Cells were inoculated into the upper compartment with DMEM, and DMEM containing 10% FBS was added in the lower compartment. After incubation for 24 h, cells were fixed and stained. Images were obtained under the microscope (Leica).

Bioinformatics

To identify associated RNAs and targets of m6A readers, data were analyzed by comparing RIP and high-throughput sequencing (RIP-seq), individual-nucleotide resolution crosslinking immunoprecipitation and high-throughput sequencing (iCLIP-seq), enhanced crosslinking immunoprecipitation and high-throughput sequencing (eCLIP-seq), photoactivatable ribonucleoside-enhanced crosslinking immunoprecipitation, and high-throughput sequencing (PARCLIP-seq), high-throughput sequencing of RNA isolated by crosslinking and immunoprecipitation (HITSCLIP-seq), RNA-seq, and methylated RIP-seq (MeRIP-seq/m6A-seq) data, which were extracted from GEO DataSets (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/)61 and m6a2target database (http://m6a2target.canceromics.org).62 The expressions of YTHDC1/2 and YTHDF1/2/3 in normal and tumorous tissue were analyzed using the GEPIA database (http://gepia.cancer-pku.cn/).63 The expression of IGF2BP1/2/3 in normal and tumorous tissue was analyzed using the starBase database (http://starbase.sysu.edu.cn/).64 Interconnections among proteins were determined using the STRING database (https://string-db.org).65 The potential m6A sites were predicted using the online tools SRAMP (http://www.cuilab.cn/sramp)23 and RMVar (http://rmvar.renlab.org).24 RNA secondary structure prediction was conducted with RNAstructure (http://rna.urmc.rochester.edu/RNAstructureWeb).28 KEGG pathway enrichment analysis was performed by DAVID (https://david.ncifcrf.gov).66,67 Domain enrichment analysis was performed by ToppGene Suite (http://toppgene.cchmc.org)68 and SMART (http://smart.embl.de).69 PARCLIP-Seq or eCLIP-Seq data of EWSR1 and KHDRBS1 were extracted from the POSTAR3 database (http://postar.ncrnalab.org).70 RNA-binding proteins were predicted using the RBPDB database (http://rbpdb.ccbr.utoronto.ca).31 Expressions of EWSR1 and KHDRBS1 in tumors were analyzed using TCGA samples at the UALCAN website (http://ualcan.path.uab.edu).71 The overall survival for LUAD patients with different expression of EWSR1 and KHDRBS1 were analyzed using online tools at the Kaplan-Meier Plotter website (https://kmplot.com).72

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD); each experiment was repeated three times or five times. Student’s t test, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), two-way ANOVA, Pearson correlation analysis, Kaplan-Meier method, and log rank test were used for statistical analysis. p < 0.05 indicated statistical significance.

Data availability statement

The mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium (http://proteomecentral.proteomexchange.org) via the iProX partner repository60 with the dataset identifier PXD033184. The RNA-seq data have been deposited to NCBI’s GEO (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/)61 and are accessible through GEO Series accession number GSE20073.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82173015 and 81871907), the National Key R&D Program of China (2022YFC2406600), Shanghai Jiao Tong University (YG2022ZD024), the Innovative Research Team of High-level Local Universities in Shanghai (SHSMU-ZLCX20212302), Shanghai Municipal Education Commission-Gaofeng Clinical Medicine (20191834), Project of Clinical Research Supporting System, Clinical Medicine First-class Discipline, Talent Training Plan of Shanghai Chest Hospital in 2021 (2021YNZYJ01 to J.W.), and Science and Technology Commission of Shanghai Municipality Project (21140902800). We thank Gabrielle White Wolf, PhD, from Liwen Bianji (Edanz) (www.liwenbianji.cn) for editing the English text of a draft of this article.

Author contributions

X.X. performed the experiments, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. L.M. and X.Z. analyzed the data. S.G., W.G., Y.W., and S.Q. helped with some experiments. X.T. collected clinical samples. Y.M. performed the animal experiments. Y.Y. designed the study. J.W. designed the study and wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymthe.2022.12.013.

Supplemental information

References

- 1.Jiang X., Liu B., Nie Z., Duan L., Xiong Q., Jin Z., Yang C., Chen Y. The role of m6A modification in the biological functions and diseases. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2021;6:74. doi: 10.1038/s41392-020-00450-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang S., Chai P., Jia R., Jia R. Novel insights on m6A RNA methylation in tumorigenesis: a double-edged sword. Mol. Cancer. 2018;17:101. doi: 10.1186/s12943-018-0847-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barbieri I., Tzelepis K., Pandolfini L., Shi J., Millán-Zambrano G., Robson S.C., Aspris D., Migliori V., Bannister A.J., Han N., et al. Promoter-bound METTL3 maintains myeloid leukaemia by m6A-dependent translation control. Nature. 2017;552:126–131. doi: 10.1038/nature24678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dominissini D., Moshitch-Moshkovitz S., Schwartz S., Salmon-Divon M., Ungar L., Osenberg S., Cesarkas K., Jacob-Hirsch J., Amariglio N., Kupiec M., et al. Topology of the human and mouse m6A RNA methylomes revealed by m6A-seq. Nature. 2012;485:201–206. doi: 10.1038/nature11112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bartosovic M., Molares H.C., Gregorova P., Hrossova D., Kudla G., Vanacova S. N6-methyladenosine demethylase FTO targets pre-mRNAs and regulates alternative splicing and 3'-end processing. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:11356–11370. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xiang Y., Laurent B., Hsu C.H., Nachtergaele S., Lu Z., Sheng W., Xu C., Chen H., Ouyang J., Wang S., et al. m6A RNA methylation regulates the UV-induced DNA damage response. Nature. 2017;543:573–576. doi: 10.1038/nature21671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang X., Lu Z., Gomez A., Hon G.C., Yue Y., Han D., Fu Y., Parisien M., Dai Q., Jia G., et al. N6-methyladenosine-dependent regulation of messenger RNA stability. Nature. 2014;505:117–120. doi: 10.1038/nature12730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen Y., Peng C., Chen J., Chen D., Yang B., He B., Hu W., Zhang Y., Liu H., Dai L., et al. WTAP facilitates progression of hepatocellular carcinoma via m6A-HuR-dependent epigenetic silencing of ETS1. Mol. Cancer. 2019;18:127. doi: 10.1186/s12943-019-1053-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liao S., Sun H., Xu C. YTH domain: a family of N6-methyladenosine m6A readers. Genomics Proteomics Bioinformatics. 2018;16:99–107. doi: 10.1016/j.gpb.2018.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu N., Zhou K.I., Parisien M., Dai Q., Diatchenko L., Pan T. N6-methyladenosine alters RNA structure to regulate binding of a low-complexity protein. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:6051–6063. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huang H., Weng H., Sun W., Qin X., Shi H., Wu H., Zhao B.S., Mesquita A., Liu C., Yuan C.L., et al. Recognition of RNA N6-methyladenosine by IGF2BP proteins enhances mRNA stability and translation. Nat. Cell Biol. 2018;20:285–295. doi: 10.1038/s41556-018-0045-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alarcón C.R., Goodarzi H., Lee H., Liu X., Tavazoie S., Tavazoie S.F. HNRNPA2B1 is a mediator of m6A-dependent nuclear RNA processing events. Cell. 2015;162:1299–1308. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang Q., Chen C., Ding Q., Zhao Y., Wang Z., Chen J., Jiang Z., Zhang Y., Xu G., Zhang J., et al. METTL3-mediated m6A modification of HDGF mRNA promotes gastric cancer progression and has prognostic significance. Gut. 2020;69:1193–1205. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2019-319639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhu H., Gan X., Jiang X., Diao S., Wu H., Hu J. ALKBH5 inhibited autophagy of epithelial ovarian cancer through miR-7 and BCL-2. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019;38:163. doi: 10.1186/s13046-019-1159-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Einstein J.M., Perelis M., Chaim I.A., Meena J.K., Nussbacher J.K., Tankka A.T., Yee B.A., Li H., Madrigal A.A., Neill N.J., et al. Inhibition of YTHDF2 triggers proteotoxic cell death in MYC-driven breast cancer. Mol. Cell. 2021;81:3048–3064.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2021.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huang H., Weng H., Chen J. m6A modification in coding and non-coding RNAs: roles and therapeutic implications in cancer. Cancer Cell. 2020;37:270–288. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2020.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sheng Y., Wei J., Yu F., Xu H., Yu C., Wu Q., Liu Y., Li L., Cui X.L., Gu X., et al. A critical role of nuclear m6A reader YTHDC1 in leukemogenesis by regulating MCM complex-mediated DNA replication. Blood. 2021;138:2838–2852. doi: 10.1182/blood.2021011707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu T., Wei Q., Jin J., Luo Q., Liu Y., Yang Y., Cheng C., Li L., Pi J., Si Y., et al. The m6A reader YTHDF1 promotes ovarian cancer progression via augmenting EIF3C translation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020;48:3816–3831. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkaa048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xu Y., He X., Wang S., Sun B., Jia R., Chai P., Li F., Yang Y., Ge S., Jia R., et al. The m6A reading protein YTHDF3 potentiates tumorigenicity of cancer stem-like cells in ocular melanoma through facilitating CTNNB1 translation. Oncogene. 2022;41:1281–1297. doi: 10.1038/s41388-021-02146-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jorjani H., Kehr S., Jedlinski D.J., Gumienny R., Hertel J., Stadler P.F., Zavolan M., Gruber A.R. An updated human snoRNAome. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:5068–5082. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kuhlmann J.D., Baraniskin A., Hahn S.A., Mosel F., Bredemeier M., Wimberger P., Kimmig R., Kasimir-Bauer S. Circulating U2 small nuclear RNA fragments as a novel diagnostic tool for patients with epithelial ovarian cancer. Clin. Chem. 2014;60:206–213. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2013.213066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dong X., Ding S., Yu M., Niu L., Xue L., Zhao Y., Xie L., Song X., Song X. Small nuclear RNAs (U1, U2, U5) in tumor-educated platelets are downregulated and act as promising biomarkers in lung cancer. Front. Oncol. 2020;10:1627. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2020.01627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhou Y., Zeng P., Li Y.H., Zhang Z., Cui Q. SRAMP: prediction of mammalian N6-methyladenosine (m6A) sites based on sequence-derived features. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:e91. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Luo X., Li H., Liang J., Zhao Q., Xie Y., Ren J., Zuo Z. RMVar: an updated database of functional variants involved in RNA modifications. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021;49:D1405–D1412. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkaa811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ma L., Chen T., Zhang X., Miao Y., Tian X., Yu K., Xu X., Niu Y., Guo S., Zhang C., et al. The m6A reader YTHDC2 inhibits lung adenocarcinoma tumorigenesis by suppressing SLC7A11-dependent antioxidant function. Redox Biol. 2021;38:101801. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2020.101801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ma L., Xue X., Zhang X., Yu K., Xu X., Tian X., Miao Y., Meng F., Liu X., Guo S., et al. The essential roles of m6A RNA modification to stimulate ENO1-dependent glycolysis and tumorigenesis in lung adenocarcinoma. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2022;41:36. doi: 10.1186/s13046-021-02200-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen F., Chen Z., Guan T., Zhou Y., Ge L., Zhang H., Wu Y., Jiang G.-M., He W., Li J., Wang H. N6-Methyladenosine regulates mRNA stability and translation efficiency of KRT7 to promote breast cancer lung metastasis. Cancer Res. 2021;81:2847–2860. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-20-3779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bellaousov S., Reuter J.S., Seetin M.G., Mathews D.H. RNAstructure: web servers for RNA secondary structure prediction and analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:W471–W474. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nagarajan V.K., Jones C.I., Newbury S.F., Green P.J. XRN 5'→3' exoribonucleases: structure, mechanisms and functions. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2013;1829:590–603. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2013.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Januszyk K., Lima C.D. The eukaryotic RNA exosome. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2014;24:132–140. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2014.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cook K.B., Kazan H., Zuberi K., Morris Q., Hughes T.R. RBPDB: a database of RNA-binding specificities. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:D301–D308. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang Y., Hamada M. Identification of m6A-associated RNA binding proteins using an integrative computational framework. Front. Genet. 2021;12:625797. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2021.625797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jønson L., Vikesaa J., Krogh A., Nielsen L.K., Hansen T.v., Borup R., Johnsen A.H., Christiansen J., Nielsen F.C. Molecular composition of IMP1 ribonucleoprotein granules. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 2007;6:798–811. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M600346-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hu J., Yang L., Peng X., Mao M., Liu X., Song J., Li H., Chen F. METTL3 promotes m6A hypermethylation of RBM14 via YTHDF1 leading to the progression of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hum. Cell. 2022;35:1838–1855. doi: 10.1007/s13577-022-00769-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhao Y., Shi Y., Shen H., Xie W. m6A-binding proteins: the emerging crucial performers in epigenetics. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2020;13:35. doi: 10.1186/s13045-020-00872-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Surdez D., Zaidi S., Grossetête S., Laud-Duval K., Ferre A.S., Mous L., Vourc'h T., Tirode F., Pierron G., Raynal V., et al. STAG2 mutations alter CTCF-anchored loop extrusion, reduce cis-regulatory interactions and EWSR1-FLI1 activity in Ewing sarcoma. Cancer Cell. 2021;39:810–826.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2021.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hamilton G. Comparative characteristics of small cell lung cancer and Ewing’s sarcoma: a narrative review. Transl. Lung Cancer Res. 2022;11:1185–1198. doi: 10.21037/tlcr-22-58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Endo A., Tomizawa D., Aoki Y., Morio T., Mizutani S., Takagi M. EWSR1/ELF5 induces acute myeloid leukemia by inhibiting p53/p21 pathway. Cancer Sci. 2016;107:1745–1754. doi: 10.1111/cas.13080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhi X., Lin L., Yang S., Bhuvaneshwar K., Wang H., Gusev Y., Lee M.H., Kallakury B., Shivapurkar N., Cahn K., et al. βII-Spectrin (SPTBN1) suppresses progression of hepatocellular carcinoma and Wnt signaling by regulation of Wnt inhibitor kallistatin. Hepatology. 2015;61:598–612. doi: 10.1002/hep.27558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Du Q., Zhang X., Liu Q., Zhang X., Bartels C.E., Geller D.A. Nitric oxide production upregulates Wnt/β-catenin signaling by inhibiting Dickkopf-1. Cancer Res. 2013;73:6526–6537. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-1620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Maniatis T. A ubiquitin ligase complex essential for the NF-κB, Wnt Wingless, and Hedgehog signaling pathways. Mol. Cell. 2022;10:1519–1526. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sung H., Ferlay J., Siegel R.L., Laversanne M., Soerjomataram I., Jemal A., Bray F. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA. Cancer J. Clin. 2021;71:209–249. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Relli V., Trerotola M., Guerra E., Alberti S. Abandoning the notion of non-small cell lung cancer. Trends Mol. Med. 2019;25:585–594. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2019.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lee Y., Rio D.C. Mechanisms and regulation of alternative pre-mRNA splicing. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2015;84:291–323. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060614-034316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Oh J.M., Venters C.C., Di C., Pinto A.M., Wan L., Younis I., Cai Z., Arai C., So B.R., Duan J., Dreyfuss G. U1 snRNP regulates cancer cell migration and invasion in vitro. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:1. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-13993-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang Z., Wang X., Wang Y., Tang S., Feng C., Pan L., Lu Q., Tao Y., Xie Y., Wang Q., Tang Z. Transcriptomic analysis of gene networks regulated by U11 small nuclear RNA in bladder cancer. Front. Genet. 2021;12:695597. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2021.695597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Diribarne G., Bensaude O. 7SK RNA, a non-coding RNA regulating P-TEFb, a general transcription factor. RNA Biol. 2009;6:122–128. doi: 10.4161/rna.6.2.8115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]