Abstract

The human cervical spine supports substantial compressive load in vivo. However, the traditional in vitro testing methods rarely include compressive loads, especially in investigations of multi-segment cervical spine constructs. Previously, a systematic comparison was performed between the standard pure moment with no compressive loading and published compressive loading techniques (follower load - FL, axial load - AL, and combined load - CL). The systematic comparison was structured a priori using a statistical design of experiments and the desirability function approach, which was chosen based on the goal of determining the optimal compressive loading parameters necessary to mimic the segmental contribution patterns exhibited in vivo. The optimized set of compressive loading parameters resulted in in vitro segmental rotations that were within one standard deviation and 10% of average percent error of the in vivo mean throughout the entire motion path. As hypothesized, the values for the optimized independent variables of FL and AL varied dynamically throughout the motion path. FL was not necessary at the extremes of the flexion-extension (FE) motion path but peaked through the neutral position, whereas, a large negative value of AL was necessary in extension and increased linearly to a large positive value in flexion. Although further validation is required, the long-term goal is to develop a “physiologic” in vitro testing method, which will be valuable for evaluating adjacent segment effect following spinal fusion surgery, disc arthroplasty instrumentation testing and design, as well as mechanobiology experiments where correct kinematics and arthrokinematics are critical.

Keywords: cervical spine, kinematics, range of motion, follower load, compressive preload, optimization, design of experiments, desirability function

1. Background

The human cervical spine supports substantial compressive load in vivo resulting from muscle forces and the weight of the head. However, the traditional in vitro testing methods rarely include compressive loads, especially in investigations of multi-segment cervical spine constructs. Various methods of modeling physiologic loading have been reported in the literature, including axial forces produced with inclined loading plates, eccentric axial force application, follower load, and attempts to individually apply or model muscle forces in vitro (Adams and Dolan, 2005; Cook and University of Pittsburgh. School of Engineering, 2009; Cripton et al., 2000; DiAngelo and Foley, 2004; Goel et al., 2006; Miura et al., 2002; Panjabi, 1988, 2007; Panjabi et al., 2001; Patwardhan et al., 2000; Wilke et al., 1994; Wilke et al., 1998; Wilke et al., 2001). The importance of correctly applying compressive loading to recreate the segmental motion patterns exhibited in vivo has been highlighted in previous studies (DiAngelo and Foley, 2004; Miura et al., 2002; Panjabi et al., 2001). However, appropriate methods of representing the weight of head and muscle loading are still subject to debate.

Previously, a systematic comparison was performed between standard pure moment with no compressive loading and published compressive loading techniques (follower load - FL, axial load - AL, and combined load - CL) (Bell et al., 2016). The pure moment testing protocol without compression, or with the application of FL, was not able to replicate the typical in vivo segmental motion patterns throughout the entire motion path. AL, or a combination of axial and follower load (combined load - CL), was necessary to mimic the in vivo segmental contributions at the extremes of the extension-flexion motion path. It was hypothesized that dynamically altering the compressive loading throughout the motion path was necessary to mimic the segmental contribution patterns exhibited in vivo.

The systematic comparison of the compressive loading techniques was structured a priori using a statistical design of experiments (DOE). DOE is a statistical technique, used primarily in quality control, wherein experiments are intentionally planned at the data collection stage to ensure valid and defensible conclusions are determined with minimal cost (Anderson and Whitcomb, 2000). This technique is particularly beneficial at the screening phase of experimentation when there is a hypothesized effect of some input factor, but the parameters surrounding the anticipated effect are largely unknown.

The DOE methodology was also chosen based on the goal of determining the optimal compressive loading parameters (multiple inputs) required to mimic the segmental motion patterns exhibited in vivo (multiple outputs). The desirability function approach, which optimizes multiple response processes, searches for the optimal input conditions that provide the “most desirable” outputs (National Institute of Standards and and International). In the desirability function any output parameter outside of the desired limits is unacceptable, and results in a desirability score of zero (0), whereas complete agreement for all response values results in a desirability score of one (1).

The DOE and desirability function were employed to further explore the finding that either AL or CL was necessary to mimic in vivo segmental contributions at the extremes of the extension-flexion motion path. The objective of this study was to determine the optimal compressive loading parameters to confirm or reject the hypothesis that dynamically altering loading throughout the motion path is necessary to mimic the segmental contribution patterns exhibited in vivo.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. In vitro dataset

The previously reported in vitro dataset, consisting of twelve fresh-frozen human cervical cadaveric specimens (N=12, C3-7, 2 female and 10 male, 51.8 years ± 7.3), were pre-screened with computed tomography (CT) and dissected, preserving osteoligamentous structures (Bell et al., 2016). Specimens were mounted on a robotic spine testing system as previously described (Bell et al., 2013). The robot was controlled via custom PC software (MATLAB, Mathworks, Inc., Natick, MA) and operated under adaptive displacement control to a pure moment target of 2.0 Nm for flexion and extension (FE) for each state in a randomized order (no compression, FL = 100 N, AR = 50 N, and CL = 150 N). Segmental motion was recorded using a five-camera motion tracking system (VICON Inc., Denver, CO) with passive reflective markers rigidly attached to each vertebral body. A handheld VICON digitizer was utilized to digitize the anatomical coordinate system for each vertebral body relative to the marker group, and the Euler angle rotations of C34, C45, C56, and C67 were determined and reported.

2.2. Load application

As previously reported, FL, AL, and CL were applied to the specimen (Bell et al., 2016). FL of 100 N was accomplished by loading the specimen using bilateral cables that passed through cable guides inserted into the vertebral bodies and over pulleys attached to the base. Optimization of FL path to align with the specimen’s center of rotation was accomplished through an offline iterative feedback process using the moment output of the testing system’s on-board six-axis load cell. The position of the cable guide was then adjusted to counteract the moment change and the process was repeated until less than 0.1 Nm change in moment was observed. Based on previous reports that show that the cervical spine buckles at very low loads when AL is applied globally, AL was applied along a locally fixed axis (perpendicular to the robot end effector) or globally fixed to the world coordinate system (Patwardhan et al., 2000). AL with a target of 50 N (DiAngelo and Foley, 2004) was applied using the robotic arm to represent the approximate weight of the head. CL, the combination of FL and AL, was applied based on the hypothesis that the combination would have a synergistic effect, producing more physiologic kinematics.

2.3. In vivo dataset

The previously reported in vivo dataset (Anderst et al., 2013a, b) utilized in the present study was reanalyzed for direct comparison with the current in vitro data. In vivo data consisted of N=20 asymptomatic control patients (13 female and 7 male, 45.5 years ± 5.8) who consented to participate in an Institutional Review Board-approved protocol. Subjects performed continuous, full range of motion (ROM) flexion-extension at a rate of one complete cycle every three seconds. Subject-specific bone models of C3-C7 were created from CT scans. A previously validated tracking process determined three-dimensional vertebral position with sub-millimeter accuracy by matching bone models from the CT scan to the biplane X-rays (Anderst et al., 2011). As reported previously, the in vitro ROM was on average 12.3% smaller than the in vivo dataset (Bell et al., 2016). Therefore, the in vivo segmental rotation was uniformly “scaled” by a factor of 87.7% prior to optimization.

2.4. Data analysis

The data was analyzed using the DOE methodology, in which physiologic values of the independent variables (FL and AL) were tested individually, then in combination, in order to explore their effect on the dependent variables (C34, C45, C56, and C67 segmental kinematics). An analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed to determine percentage of the variance in the dependent variables that is attributed to the independent variables. The results were quantified in terms of percent contribution and standardized effect size of the independent variables.

The in vivo data was uniformly scaled to match the in vitro data by adjusting for mean differences between in vitro and in vivo ROM then normalizing to percent ROM. Optimization was then performed based on the output of the ANOVA using the desirability function approach. The desirability function approach searched for the optimal independent variables (FL and AL) that provided the “most desirable” independent variables (segmental kinematics). It was previously reported that effects of the loading conditions were dependent on percentage of ROM and segmental level, therefore the optimization was performed at 20%, 40%, 60%, 80%, and 100% of the overall extension-flexion motion path (Bell et al., 2016).

Since the goal was to optimize the in vitro data using the in vivo data as the target, the “target is best” desirability function was used (Equation 1) (Derringer and Suich, 1980). The segment-specific target was defined as the mean of the in vivo data, and the upper and lower limits were defined as the in vivo mean plus or minus the in vivo standard deviation respectively (Equation 1). The overall desirability (Equation 2) was determined by calculating the geometric mean of the individual desirability values. The implication of the multiplicative term in the equation for calculating the overall desirability was that if any of the individual desirability values fell outside the acceptable limits (one standard deviation of the mean) then the overall desirability equaled zero (0).

Equation 1: “Target is Best” Desirability Function

Equation 2: Overall Desirability

A Shapiro-Wilk test was performed, which indicated that not all data were normally distributed, therefore a non-parametric Wilcoxon signed-rank test for paired design was used to identify significant (*p<0.05) differences between the experimental and optimized results.

3. Results

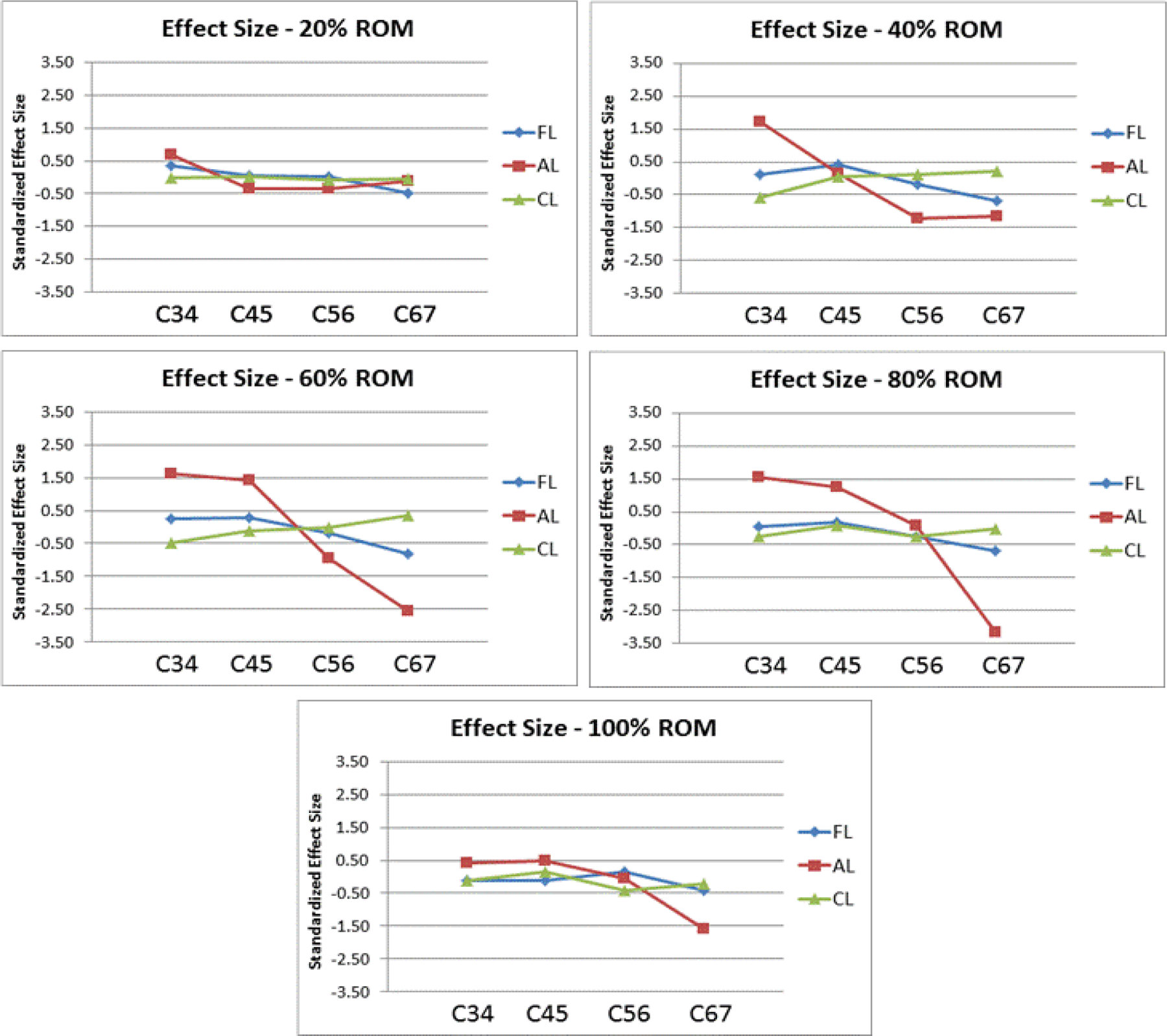

Overall, the application of AL was shown to have the largest effect in altering the segmental motion patterns (Figure 1). The largest effects were observed throughout the middle of the motion path (40%, 60%, and 80%). The effect of AL varied in magnitude throughout the motion path, but the overall trend was preserved with an increase of ROM of C34 and C45 and decrease of ROM of C56 and C67. Applying AL is an ideal candidate for optimization based on its relatively large effect size.

Figure 1.

Line graphs detailing the standardized effect size of FL, AL, and CL at C34, C45, C56, and C67 at 20%, 40%, 60%, 80%, and 100% of the extension-flexion motion path.

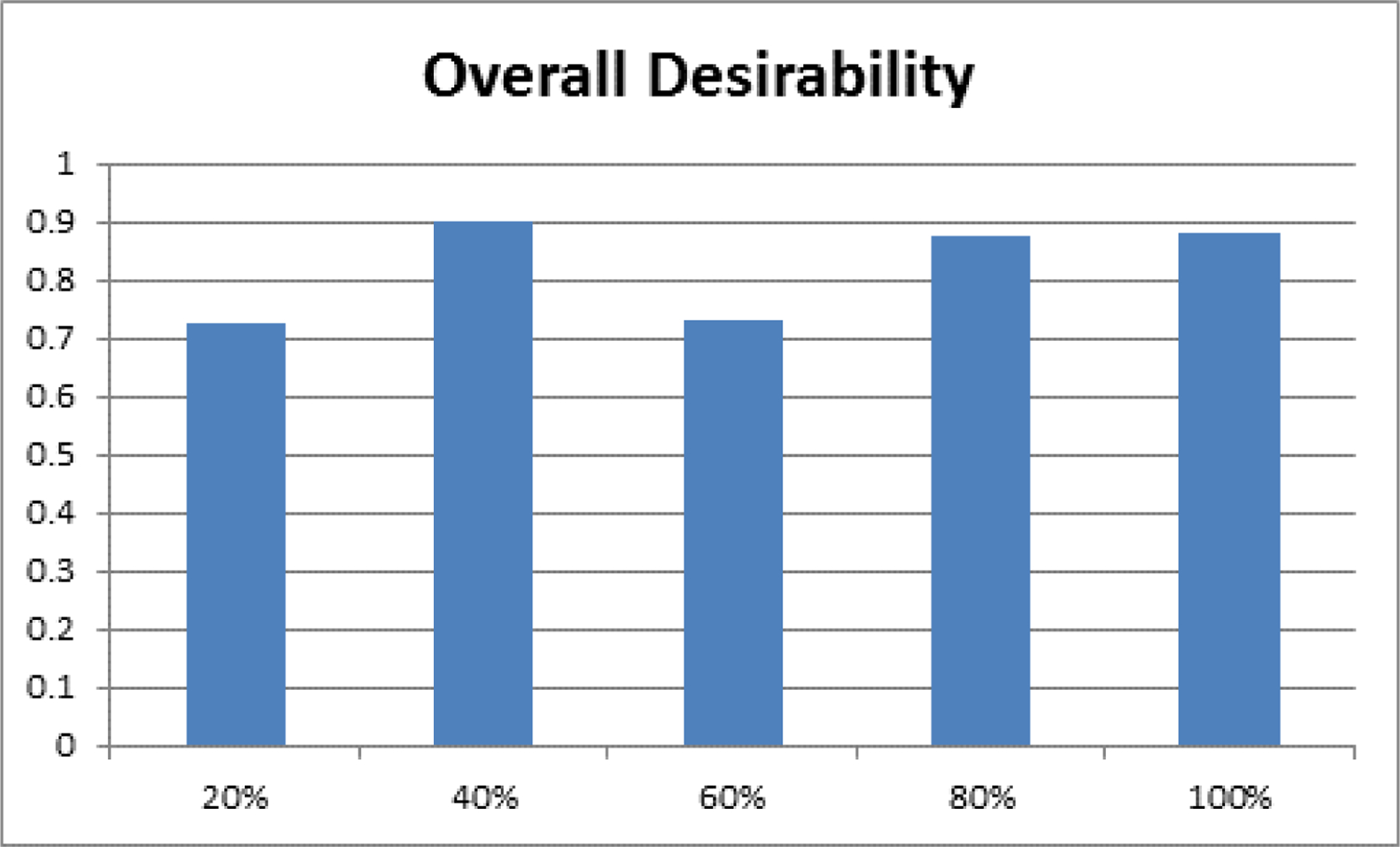

With regards to overall desirability, greater than 0.7 desirability was observed at all points in the motion path indicating large agreement with the in vivo dataset (Figure 2). The lowest overall desirability was observed at 20% and 60% of the overall motion path and the best agreement was observed at 40%, 80%, and 100%—each of which had close to a 0.9 overall desirability.

Figure 2:

A bar graph of the overall desirability, an indication of the agreement with the in vivo dataset, shown at 20%, 40%, 60%, 80%, and 100% of the extension-flexion motion path.

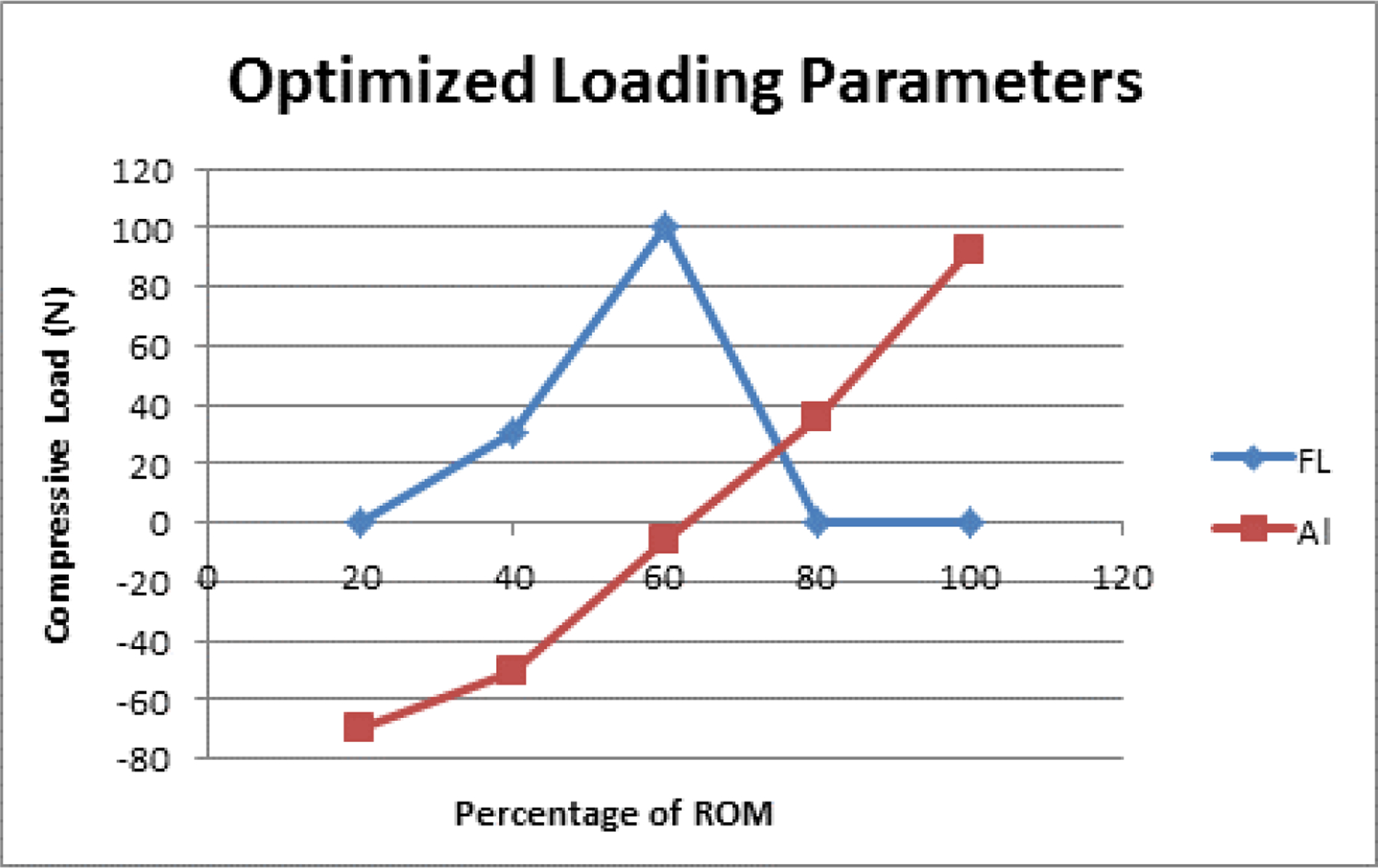

Based on the optimized loading parameters that were determined, FL was found to be equal to zero at the extremes of the extension-flexion motion path, but peaked near the middle portion of the motion path with a maximum value of 100 N at 60% ROM (Figure 3). Conversely, AL increased linearly throughout the motion path with a range of −69.8 N to 92.8 N with the 60% ROM resulting in 0 N of AL.

Figure 3:

Line graph of the optimized loading parameters for FL and AL at 20%, 40%, 60%, 80%, and 100% of the extension-flexion motion path.

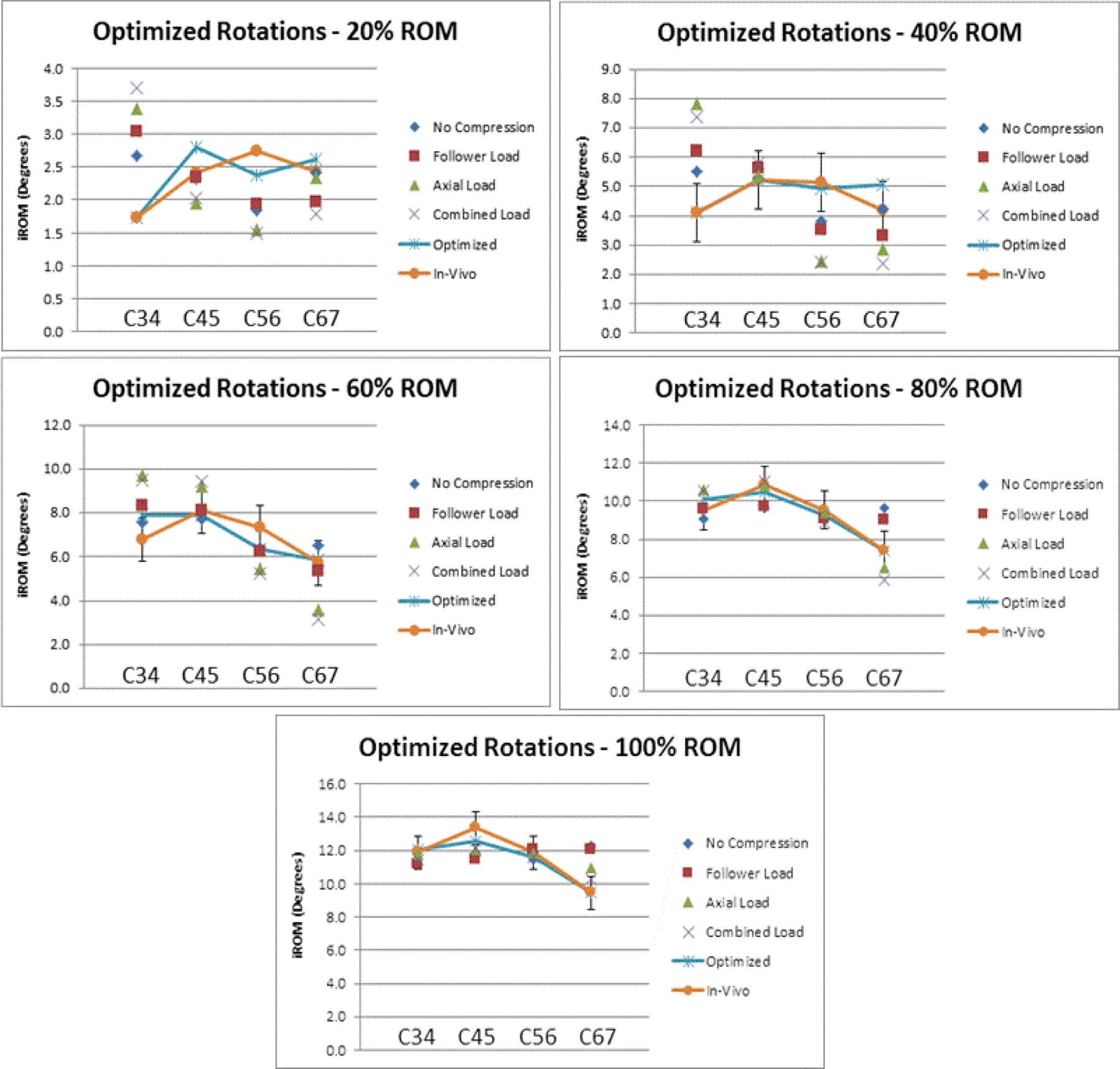

As shown in the scatterplot of the optimized rotations relative to the in vivo mean values and the four in vitro compressive loading states, none of the un-optimized compressive loading states are individually able to replicate the in vivo segmental motion patterns (Figure 4). However, the optimized compressive loading parameters were able to mimic the in vivo segmental motion patterns throughout the entire motion path.

Figure 4:

Line graph of the optimized segmental rotations plotted relative to the segmental rotation for the individual compressive loading conditions and the in vivo segmental rotation at 20%, 40%, 60%, 80%, and 100% of the extension-flexion motion path. Error bars represent the in vivo standard deviation.

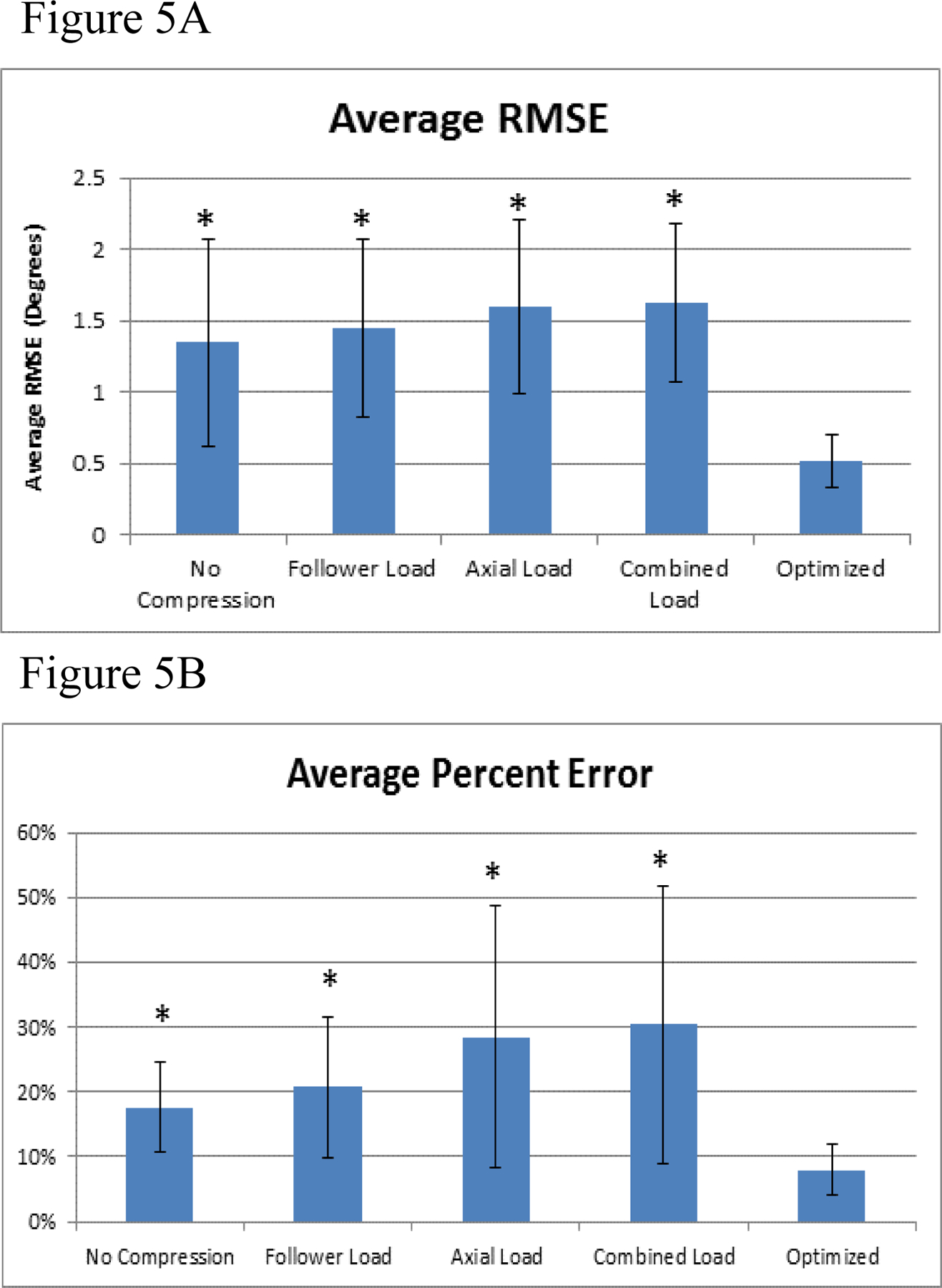

The agreement between compressive loading states, including the optimized compressive loading parameters and the in vivo segmental rotation was quantified using root mean square error (RMSE) (Figure 5A). All compressive loading states had significantly higher RMSE (p<0.05) than the optimized loading parameters. Normalization of RMSE was performed and quantified as average percent error, which is defined as the RMSE divided by the in vivo mean ROM (Figure 5B). Again, all un-optimized compressive load states had a significantly higher (p<0.05) average percent error than the optimized compressive loading parameters. Additionally, the optimized compressive loading parameters were the only states resulting in an average percent error of less than 10%.

Figure 5:

A) The average root mean square error (RMSE) and the B) average percent error relative to in vivo for the optimized loading conditions and the individual compressive loading conditions. Error bars represent the standard deviations and * represents significant differences (p , 0.05) compared to the optimized values.

4. Discussion

Recent critical reviews of the in vitro biomechanics (Volkheimer et al., 2015) and in vivo kinematic (Malakoutian et al., 2015) literature demonstrated a notable disconnect, bringing into question the current “gold standard” in vitro biomechanical methodologies. Based on the observed limitations of the current in vitro testing methods, the review concluded that “…none of the current test protocols can replicate the in-vivo kinematics…” (Volkheimer et al., 2015). Therefore, the objective of the present study was to determine the optimal compressive loading parameters necessary to mimic the segmental contribution patterns exhibited in vivo.

In this study, the DOE and desirability function were employed to determine the optimal compressive loading parameters necessary to mimic the segmental contribution patterns exhibited in vivo. The optimized set of compressive loading parameters were within plus or minus one standard deviation of the in vivo mean throughout the entire motion path. In terms of average percent error, the optimized compressive loading parameters resulted in in vitro segmental contributions that were within 10% of the in vivo mean. As hypothesized, the values for the optimized independent variables of FL and AL varied dynamically throughout the motion path. FL was not necessary at the extremes of the extension-flexion motion path but peaked through the neutral position. FL is critical through the “Neutral Zone” (NZ) for stability but detrimental in the “Elastic Zone” (EZ), whereas a large negative value of AL was necessary in extension and increased linearly to a large positive value in flexion.

The linear increasing value for AL may be reflective of the in vivo influence of increased muscular contribution with increasing rotation. This is consistent with muscular models of the cervical spine, which illustrate that the resultant load experienced on the head increases with rotation (Cheng et al., 2008; Johnston et al., 2008; Schuldt, 1988). In the present study the AL force was applied perpendicular to the most superior vertebral body (C3), which mimics the resultant muscular force on the head as it is transmitted to the vertebral column through the occiput.

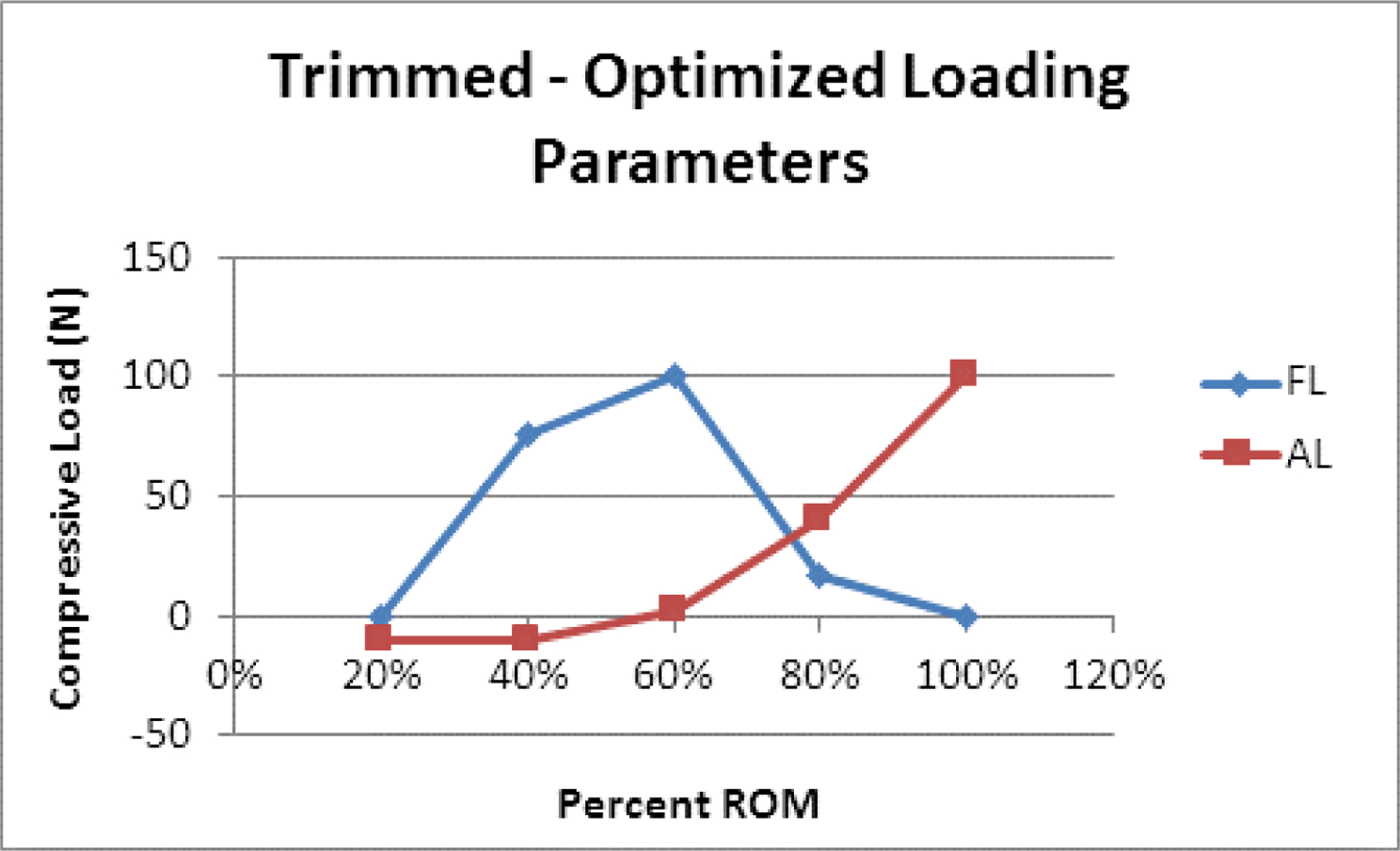

This study was based upon in vitro (Bell et al., 2016) and in vivo (Anderst et al., 2013a, b) data previously collected and reported. Therefore, this study is also subject to the same limitations as the primary manuscripts. One additional limitation of the present study is that the in vivo data had to be scaled prior to optimization. It is hypothesized that the reason for the higher ROM in the in vivo data resulted from a disagreement in the mechanism for determining the end ROM. In the in vivo dataset, the subjects were asked to rotate to a self-determined maximum rotation stopping point; whereas in the in vitro dataset, end ROM was defined as +/− 2.0 Nm. Optimization of the scaled segmental rotation data resulted in the large negative value for AL in the extreme extension portion of the motion path, which was well outside of the tested parameters for the model. To better understand and possibly avoid the large negative values for AL, optimization was also performed with AL restricted to a range of −10 N to 100 N. Using the scaled in vivo dataset, restricting AL to a range of −10 N to 100 N resulted in zero desirability at 20% and 40% ROM. To explore this further, instead of scaling the in vivo dataset, a secondary analysis was performed wherein the in vivo dataset was “trimmed” based on the average flexion and extension endpoints relative to the neutral position. Approximately 10% of the overall trimming occurred on the extension side and approximately 2% of the trimming occurred on the flexion side. When the optimization procedure was repeated with the “trimmed” data, and AL restricted to a range of −10 N to 100 N, acceptable optimized solutions were found within one standard deviation of the in vivo mean for all portions of the motion path (20% = 0.42 desirability, 40% = 0.61 desirability, 60% = 0.76 desirability, 80% = 0.91 desirability, 100% = 0.83 desirability). In comparison to the scaled optimized loading parameters (AL −10 N to 100 N), the optimized values for FL still began and ended at 0 N at the extremes of extension-flexion, but the peak was broadened, extending across 40% to 60% (Figure 6). The optimized values for AL were now restricted to −10 N and they increased non-linearly to a maximum value of 100 N at 100% ROM.

Figure 6:

Line graph of the optimized loading parameters for FL and AL at 20%, 40%, 60%, 80%, and 100% of the extension-flexion motion path using the “Trimmed” data rather than the “Scaled” in vivo data.

In the present study the kinematic data was presented as a change in kinematics throughout the motion path from full extension to full flexion, where full extension was defined as zero. This methodology was chosen due to a lack of confidence in the alignment of the neutral positions between the in vivo and in vitro datasets. In the in vivo dataset the subjects were asked to self-select a comfortable starting position, whereas in the in vitro dataset the neutral position was defined as the point of zero moment. In both scenarios subjectivity and sensitivity lead to low intra- and inter-testing repeatability in the neutral position, making independent analysis of the extension and flexion tails of the motion path difficult. A previous report focused on comparing in vivo and in vitro FE rotation and found that in vitro studies generally overestimate extension ROM and underestimate flexion ROM (Adams, 2004). However, the study performed by Adams et al. (2004) was performed in the lumbar spine and it is unclear if this observation can be applied to the cervical spine. Work is ongoing to develop and validate a methodology to align the in vitro and in vivo datasets using the model-based tracking software currently utilized to analyze the in vivo dataset singly. Using the model-based tracking software to define consistent anatomical coordinate systems between the in vitro and in vivo datasets would not only address this limitation, but would also expand the kinematic and arthrokinematics parameters that could be evaluated.

Finally, future work should also aim to validate the optimized parameters presented here to ensure confidence in the overall model. Specifically, the effect of independent and combined application of dynamic FL and AL, which will require increasing the range of the AL and exploring the influence of negative AL. It would also be valuable to further refine the resolution for the comparison between the in vivo and in vitro data and the resulting optimization. Currently, comparison only occurs at 20% increments throughout the extension-flexion path and although the predicted optimized loading parameters appear to change continuously throughout the motion path, the intermediate data has not been analyzed. Anderst et al. (2013a) used a mixed-model analysis to model the percent contributions from each motion segment throughout the motion path. Research aimed at optimizing the loading parameters based on a continuous model would highlight one of the largest strengths of this study: direct access to dynamic muscle-driven in vivo kinematic data.

Ultimately, optimization could be performed such that an optimized set of compressive loads would be determined for each segment. Implementation of a segment-specific loading scheme is less intuitive and may ultimately be difficult, or impossible, to achieve with the described loading schemes. However, it is theoretically possible to alter the moment each segment is experiencing throughout the motion path by optimizing/altering the line of action of AL. This segment-specific optimization would be best performed using a computational model of the cervical spine with simulated compression and rotational loads (Ahn and DiAngelo, 2007; de Jongh et al., 2007; Marin et al., 2010) and iterative learning control algorithms (Son et al., 2013). The resulting “physiologic” in vitro testing method would be valuable for evaluating adjacent segment effect following spinal fusion surgery, disc arthroplasty instrumentation testing and design, as well as mechanobiology experiments where correct kinematics and arthrokinematics are critical.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

In vitro testing was performed with the support of the Albert B. Ferguson, Jr. MD Orthopaedic Fund of The Pittsburgh Foundation. In vivo data was acquired with support from the National Institutes of Health (grant # R03 AR056265) and the Cervical Spine Research Society. I would also like to acknowledge Bill Anderst for valuable contributions to the content of this manuscript. Funding from NIH/NCCAM K08AT004718-02 award also is also acknowledged. I would also like to acknowledge Jessa Darwin and Ethan Lennox for the editorial support that they provided during the preparation of this manuscript.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no known conflicts of interest associated with this publication and there has been no significant financial support for this work that could have adversely influenced its outcome.

REFERENCES

- Adams MA, 2004. Biomechanics of back pain. Acupuncture in Medicine 22, 178–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams MA, Dolan P, 2005. Spine biomechanics. J Biomech 38, 1972–1983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahn HS, DiAngelo DJ, 2007. Biomechanical testing simulation of a cadaver spine specimen: development and evaluation study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 32, E330–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson MJ, Whitcomb PJ, 2000. DOE simplified : practical tools for effective experimentation Productivity, Portland, Or. [Google Scholar]

- Anderst WJ, Baillargeon E, Donaldson WF 3rd, Lee JY, Kang JD, 2011. Validation of a noninvasive technique to precisely measure in vivo three-dimensional cervical spine movement. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 36, E393–400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderst WJ, Donaldson WF 3rd, Lee JY, Kang JD, 2013a. Cervical Motion Segment Percent Contributions to Flexion-Extension During Continuous Functional Movement in Control Subjects and Arthrodesis Patients. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 38, E533–E539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderst WJ, Donaldson WF, Lee JY, Kang JD, 2013b. Cervical spine intervertebral kinematics with respect to the head are different during flexion and extension motions. J Biomech 46, 1471–1475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell KM, Hartman RA, Gilbertson LG, Kang JD, 2013. In vitro spine testing using a robot-based testing system: comparison of displacement control and “hybrid control”. J Biomech 46, 1663–1669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell KM, Yan Y, Debski RE, Sowa GA, Kang JD, Tashman S, 2016. Influence of varying compressive loading methods on physiologic motion patterns in the cervical spine. J Biomech 49, 167–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng CH, Lin KH, Wang JL, 2008. Co-contraction of cervical muscles during sagittal and coronal neck motions at different movement speeds. European journal of applied physiology 103, 647–654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook DJ, University of Pittsburgh. School of Engineering, 2009. Characterization of the Response of the Cadaveric Human Spine to Loading in a Six-Degree-of-Freedom Spine Testing Apparatus University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA. [Google Scholar]

- Cripton PA, Bruehlmann SB, Orr TE, Oxland TR, Nolte LP, 2000. In vitro axial preload application during spine flexibility testing: towards reduced apparatus-related artefacts. J Biomech 33, 1559–1568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Jongh CU, Basson AH, Scheffer C, 2007. Dynamic simulation of cervical spine following single-level cervical disc replacement. Conference proceedings : ... Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society. Conference 2007, 4289–4292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derringer G, Suich R, 1980. Simultaneous-Optimization of Several Response Variables. J Qual Technol 12, 214–219. [Google Scholar]

- DiAngelo DJ, Foley KT, 2004. An improved biomechanical testing protocol for evaluating spinal arthroplasty and motion preservation devices in a multilevel human cadaveric cervical model. Neurosurg Focus 17, E4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goel VK, Panjabi MM, Patwardhan AG, Dooris AP, Serhan H, 2006. Test protocols for evaluation of spinal implants. J Bone Joint Surg Am 88 Suppl 2, 103–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston V, Jull G, Souvlis T, Jimmieson NL, 2008. Neck movement and muscle activity characteristics in female office workers with neck pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 33, 555–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malakoutian M, Volkheimer D, Street J, Dvorak MF, Wilke H-J, Oxland TR, 2015. Do in vivo kinematic studies provide insight into adjacent segment degeneration? A qualitative systematic literature review. European Spine Journal 24, 1865–1881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marin F, Hoang N, Aufaure P, Ho Ba Tho MC, 2010. In vivo intersegmental motion of the cervical spine using an inverse kinematics procedure. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon) 25, 389–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miura T, Panjabi MM, Cripton PA, 2002. A method to simulate in vivo cervical spine kinematics using in vitro compressive preload. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 27, 43–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Standards and, T., International, S., 2003. Engineering statistics handbook NIST, Gaithersburg, MD. [Google Scholar]

- Panjabi MM, 1988. Biomechanical evaluation of spinal fixation devices: I. A conceptual framework. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 13, 1129–1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panjabi MM, 2007. Hybrid multidirectional test method to evaluate spinal adjacent-level effects. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon) 22, 257–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panjabi MM, Miura T, Cripton PA, Wang JL, Nain AS, DuBois C, 2001. Development of a system for in vitro neck muscle force replication in whole cervical spine experiments. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 26, 2214–2219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patwardhan AG, Havey RM, Ghanayem AJ, Diener H, Meade KP, Dunlap B, Hodges SD, 2000. Load-carrying capacity of the human cervical spine in compression is increased under a follower load. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 25, 1548–1554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuldt K, 1988. On neck muscle activity and load reduction in sitting postures. An electromyographic and biomechanical study with applications in ergonomics and rehabilitation. Scandinavian journal of rehabilitation medicine Supplement 19, 1–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Son TD, Ahn HS, Moore KL, 2013. Iterative learning control in optimal tracking problems with specified data points. Automatica : the journal of IFAC, the International Federation of Automatic Control 49, 1465–1472. [Google Scholar]

- Volkheimer D, Malakoutian M, Oxland TR, Wilke HJ, 2015. Limitations of current in vitro test protocols for investigation of instrumented adjacent segment biomechanics: critical analysis of the literature. Eur Spine J 24, 1882–1892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilke HJ, Claes L, Schmitt H, Wolf S, 1994. A universal spine tester for in vitro experiments with muscle force simulation. Eur Spine J 3, 91–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilke HJ, Jungkunz B, Wenger K, Claes LE, 1998. Spinal segment range of motion as a function of in vitro test conditions: effects of exposure period, accumulated cycles, angular-deformation rate, and moisture condition. The Anatomical record 251, 15–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilke HJ, Rohlmann A, Neller S, Schultheiss M, Bergmann G, Graichen F, Claes LE, 2001. Is it possible to simulate physiologic loading conditions by applying pure moments? A comparison of in vivo and in vitro load components in an internal fixator. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 26, 636–642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]