Abstract

Objective:

The objective of this review was to examine existing literature and conceptually map the evidence for school-based obesity prevention programs implemented in rural communities, as well as identify current gaps in the literature.

Introduction:

Pediatric obesity is a significant public health condition worldwide. Rural residency places children at increased risk of obesity. Schools have been identified as an avenue for obesity prevention in rural communities.

Inclusion criteria:

We considered citations focused on children (5 to 18 years of age) enrolled in a rural educational setting. We included obesity prevention programs delivered in rural schools that focused on nutrition or dietary changes, physical activity or exercise, decreasing screen time, or combined nutrition and physical activity that aimed to prevent childhood obesity. We included all quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods research designs, as well as text and opinion data.

Methods:

A search was conducted of published and unpublished studies in English from 1990 through April 2020 using PubMed, CINAHL Complete, ERIC, Embase, Scopus, Academic Search Premier, Cochrane Register of Controlled Trials, and ClinicalTrials.gov. Gray literature was also searched. After title and abstract review, potentially relevant citations were retrieved in full text. The full texts were assessed in detail against the inclusion criteria by 2 independent reviewers. Included citations were reviewed and data extracted by 2 independent reviewers and captured on a spreadsheet targeting the review objectives.

Results:

Of the 105 studies selected for full-text review, 72 (68.6%) were included in the final study. Most of the studies (n = 50) were published between 2010 and 2019 and were conducted in the United States (n = 57). Most studies included children in rural elementary or middle schools (n = 57) and targeted obesity prevention (n = 67). Teachers implemented the programs in half of the studies (n = 36). Most studies included a combination of physical activity and nutrition components (n = 43). Other studies focused solely on nutrition (n = 9) or physical activity (n = 9), targeted obesity prevention policies (n = 9), or other components (n = 8). Programs ranged in length from weeks to years. Overall, weight-related, physical activity–specific, and nutrition-specific outcomes were most commonly examined in the included citations.

Conclusions:

Obesity prevention programs that focused on a combination of physical activity and nutrition were the most common. Multiple outcomes were examined, but most programs included weight-specific and health behavior–specific outcomes. The length and intensity of rural school-based obesity prevention programs varied. More research examining scientific rigor and specific outcomes of rural school-based obesity prevention programs is needed.

Keywords: child health, pediatric obesity, preventive health programs, rural health, school health promotion

Introduction

High prevalence rates of pediatric overweight and obesity are global concerns because of their associations with poor health in childhood and adulthood.1–11 Recent data from some countries reveal that prevalence rates of obesity in disadvantaged subpopulations continue to increase,1 and rates of severe obesity in youth are growing.12 It is recognized that people living in rural-designated areas are one of the largest medically under-served populations.13 People living in rural areas encompasses a substantial portion of the world’s population. In 2016, approximately 19% of Americans (60 million), including 13 million children under 18 years of age, lived in a rural area.13 Worldwide, it is estimated that more than 45% of the population, or about 3.5 billion people, live in rural areas.14

Although findings are mixed, living in a rural community has been identified as a risk factor for overweight (ie, body mass index [BMI] greater than or equal to the 85th percentile for age and sex) and obesity (ie, BMI greater than or equal to the 95th percentile for age and sex) in adults and children,15–18 even after adjusting for poverty.17 Multiple factors related to rurality may increase the risk of obesity in adults and children. Residents living in rural areas are more likely to experience economic problems and have limited access to quality physical and mental health care.19 Some findings also suggest higher prevalence of diabetes, stroke, and cancer, as well as worse morbidity and mortality, among individuals living in rural compared with non-rural communities.20,21 Multiple sources indicate that youth from rural areas may engage in more unhealthy behaviors,22 such as spending more time in sedentary activities compared to those living in urban areas.15,16

Additional intersecting features that may influence health disparities in rural communities should also be considered. In some Western countries, such as the United States (US), there is evidence that rural communities are becoming increasingly more racially and ethnically diverse,23 which may result in additional disparity given that the prevalence of overweight and obesity in racial and ethnic minority youth is increasing, while stabilizing in non-Hispanic Whites in the US.12 The intersection between rurality and structural factors, such as minority vs. majority culture, should be considered in the context of obesity risk worldwide.

Prevention efforts in rural and under-served communities are needed to combat obesity in these high-risk groups.24 Schools are one avenue for intervening, given that children spend a large amount of time attending school each week; many children eat multiple meals at school each day, such as breakfast and lunch; and education about healthy nutrition and physical activity (PA) can be incorporated into academic classes. In addition, schools in rural communities and school personnel are well-respected and viewed by parents as important sources of information.25 In addition to educating students, schools may be an avenue to facilitate community health17 by providing parents with education regarding current nutrition and PA recommendations for children, which may not otherwise be available because of limited access and availability of primary care medical services in rural areas.

The role of schools has been recognized in the World Health Organization’s (WHO) Commission on Ending Childhood Obesity, which provided 6 recommendations for policy makers worldwide. One recommendation was specific to the ways schools can be involved to reduce the prevalence of obesity in youth. The school-specific recommendation is to: “Implement comprehensive programmes that promote healthy school environments, health and nutrition literacy and PA among school-age children and adolescents.”26(p.xi) In addition to worldwide efforts, specific countries have also recognized how schools promote improvements in child health. The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Whole School, Whole Community, Whole Child model27 also emphasizes the role schools play in promoting health in children and adolescents by facilitating the adaptation of health behaviors throughout life, with the recognition that health behaviors are easier to modify—and more effectively modified—when addressed in youth as opposed to changing unhealthy behaviors in adults.27

Given the importance of schools in promoting health in children, in recent years researchers have developed, implemented, and evaluated school-based obesity prevention programs focused on lifestyle behaviors and the school environment, such as healthy diet, increased PA, a motivating environment, educational curricula, and training teachers28–30; however, it is unclear what obesity prevention strategies have been implemented in schools in rural communities. Programs implemented in rural communities may need to take into account limited access to heathy foods and places to engage in safe PA, transportation and time-related issues (eg, need to travel farther distances), and economic-related issues.31 A preliminary search for existing systematic and scoping reviews was conducted in January 2018 to locate literature related to rural school-based obesity prevention programs, and no systematic reviews were identified. Thus, the current review was needed to increase understanding about the types of school-based obesity prevention programs that have been implemented in rural schools in order to inform future development of school-based obesity prevention programs in rural communities.

The objective of this scoping review was to examine the existing literature related to school-based obesity prevention programs implemented in rural communities, conceptually map the evidence, and identify current gaps in the literature.

Review questions

What types of school-based obesity prevention programs have been implemented in rural schools?

What specific elements/components of school-based obesity prevention programs have been implemented in rural schools?

What outcomes have been reported regarding school-based obesity prevention programs that have been implemented in rural schools?

Inclusion criteria

Participants

This review considered studies that included children aged 5 to 18 years of age who were enrolled in an institution that provided instruction and teaching of children, such as elementary, middle, or high school, and were conducted in a rural setting. Elementary schools were considered those that generally provided instruction to children in the first 4 years of formal education and also included schools that taught children through the first 8 years of instruction and self-identified as elementary. High school was defined as schools that included grades 9–12 or 10–12. Middle schools usually included grades 5–8 or 6–8, and were defined as such for this study. Schools included those classified as private, parochial, or publicly funded. Private schools were defined as schools that were supported by a non-governmental agency; public schools were free, tax-supported, and controlled by a local governmental authority; and parochial schools were defined as private schools maintained by a religious body. Children who were home-schooled or in an alternative setting, such as juvenile detention or hospitalized for prolonged periods, were excluded.

Concept

This scoping review considered studies about school-based obesity prevention programs implemented in rural schools, including, but not limited to, those focused on nutrition and dietary changes, PA or exercise, decreasing screen time, or mixed nutrition and PA programs aimed at childhood obesity prevention. Physical activity was defined as bodily movement produced by skeletal muscle contraction with increased energy expenditure, whereas exercise, a kind of PA, is planned, structured, repetitive movement that is often intentional and aimed at improving or maintaining health or fitness. We also considered whether the school-based obesity prevention programs implemented in rural schools incorporated behavioral components. Behavioral components included goal-setting, monitoring, self-regulation strategies, rewards/incentives, time management skills, counseling, and/or strategies to improve body image.

The school-based programs could be designed and delivered by health professionals, members of a community organization, or educators whose occupation is to teach; however, programs had to be delivered in the school setting. Health professionals could be registered dietitians, occupational therapists, physical therapists, public health practitioners, licensed nurses, dentists, physicians, pharmacists, nutritionists, mental health providers (eg, counselors, psychologists), or health educators. Studies that focused on physical fitness as an outcome and those conducted by health paraprofessionals, such as dental hygienists or nursing assistants, were excluded. Studies with obesity programs delivered to children outside of elementary, middle, or high schools, or programs offered at community facilities were also excluded.

Context

The context for this scoping review focused on schools in rural settings in any country. “Rural” is usually defined by individual countries13,14,32,33 and is often defined by exclusion, such that any area that is not urban is considered rural.34,35 This review considered any study in which the authors conducting the study classified the area as rural, as well as any study in an area designated as rural by the country’s census geographic entity.

Types of sources

This scoping review considered quantitative, qualitative, and text and opinion data. For quantitative studies, the review considered both experimental and quasi-experimental quantitative study designs including randomized controlled trials, non-randomized controlled trials, before and after studies, and interrupted time-series studies. In addition, analytical observational studies, including prospective and retrospective cohort studies, case-control studies, analytical cross-sectional studies, and systematic reviews were considered for inclusion. This review also considered descriptive observational study designs including case series, individual case reports, descriptive cross-sectional studies, and gray literature for inclusion.

Qualitative studies that focused on qualitative data, including, but not limited to, designs such as phenomenology, grounded theory, ethnography, qualitative description, action research, and feminist research were considered. Text and opinion papers were also considered for inclusion.

Methods

This review was conducted in accordance with an a priori protocol36 and the JBI methodology for scoping reviews.37

Search strategy

The search strategy aimed to find both published and unpublished studies. A three-step strategy was used, and included electronic and manual searches of reference lists, as well as government or agency websites for gray literature. The initial step included a limited search of MEDLINE (PubMed) and CINAHL, and an analysis of the text words contained in the title and abstract and of the index terms used to describe the articles. This informed the development of the search strategy, which was tailored for each information source. The second step was a search using all keywords and index terms identified in the electronic databases listed below. The third step was to search reference lists of included studies, trial registers, and unpublished studies.

Studies published in English since 1990 were included, as the rise in prevalence of childhood obesity began to be recognized during the 1980s in the US, closely followed by recognized increases in trends in other developed countries. In addition, surveillance data and analysis of rates frequently use the baseline comparator of 1990 or later.26,38–40

The databases searched included PubMed (US National Library of Medicine), CINAHL Complete (EBSCO), ERIC (EBSCO), Embase (Elsevier), Scopus (Elsevier), and Academic Search Premier (EBSCO). The trial registers searched included Cochrane Register of Controlled Trials (Wiley) and ClinicalTrials.gov. The search for unpublished studies included ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Sciences and Engineering Collection (ProQuest), OpenGrey, Open Access Theses and Dissertations, Directory of Open Access Journals, and OCLC PapersFirst. Organization websites searched included the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (MedNar), and the US Department of Education. All searches were performed in April 2019 and updated in April 2020. The full search strategies are presented in Appendix I.

Study selection

Following the search, all identified citations were imported into EndNote v.20 (Clarivate Analytics, PA, USA) and duplicates were removed. Titles and abstracts of citations were screened by 2 independent reviewers (CL, JR, XG, MH) and compared to the inclusion criteria for the scoping review. Potentially relevant studies were retrieved in full and their citation details imported into the data extraction spreadsheet in MS Excel (Redmond, Washington, USA). The full text of selected citations was assessed in detail against the inclusion criteria by 2 independent reviewers (CL, JR, XG, AG, CC, MR). Full-text studies that did not meet inclusion criteria were excluded. Reasons for their exclusion are reported in Appendix II. Disagreements that arose between the reviewers at each stage of the study selection process were resolved through consensus or by a third reviewer (CL, JR). The results of the search are reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram.41

Data extraction

Data were extracted from studies included in the scoping review by 2 independent reviewers using an a priori data extraction tool that was modified from the JBI extraction tool (CL, JR, XG, AG, CC, MR). The data extracted included specific author details, year and country of publication, defined rural designation, type of school-based prevention or intervention used, intervention components, duration of intervention, provider of the intervention, study sample and size (when reported), types of outcomes, and key findings. Any disagreements that arose between the reviewers were resolved through discussion or with a third reviewer (CL, JR).

Data analysis and presentation

While addressing the objectives proposed in the scoping review protocol, common groupings across the included articles were analyzed. The first and second authors (CL and JR) reviewed the data extracted from each included study to identify key features of school-based obesity prevention programs in rural communities. Results were later verified by co-authors. Aligned with the PCC mnemonic (participants, concept, context), only 2 of the components were appropriate for analysis and discussion based on the review questions and literature analysis. “Participants” and “concept” were analyzed and discussed because context was limited to rural school settings and invariant given the inclusion criteria for this review.

Results

Source inclusion

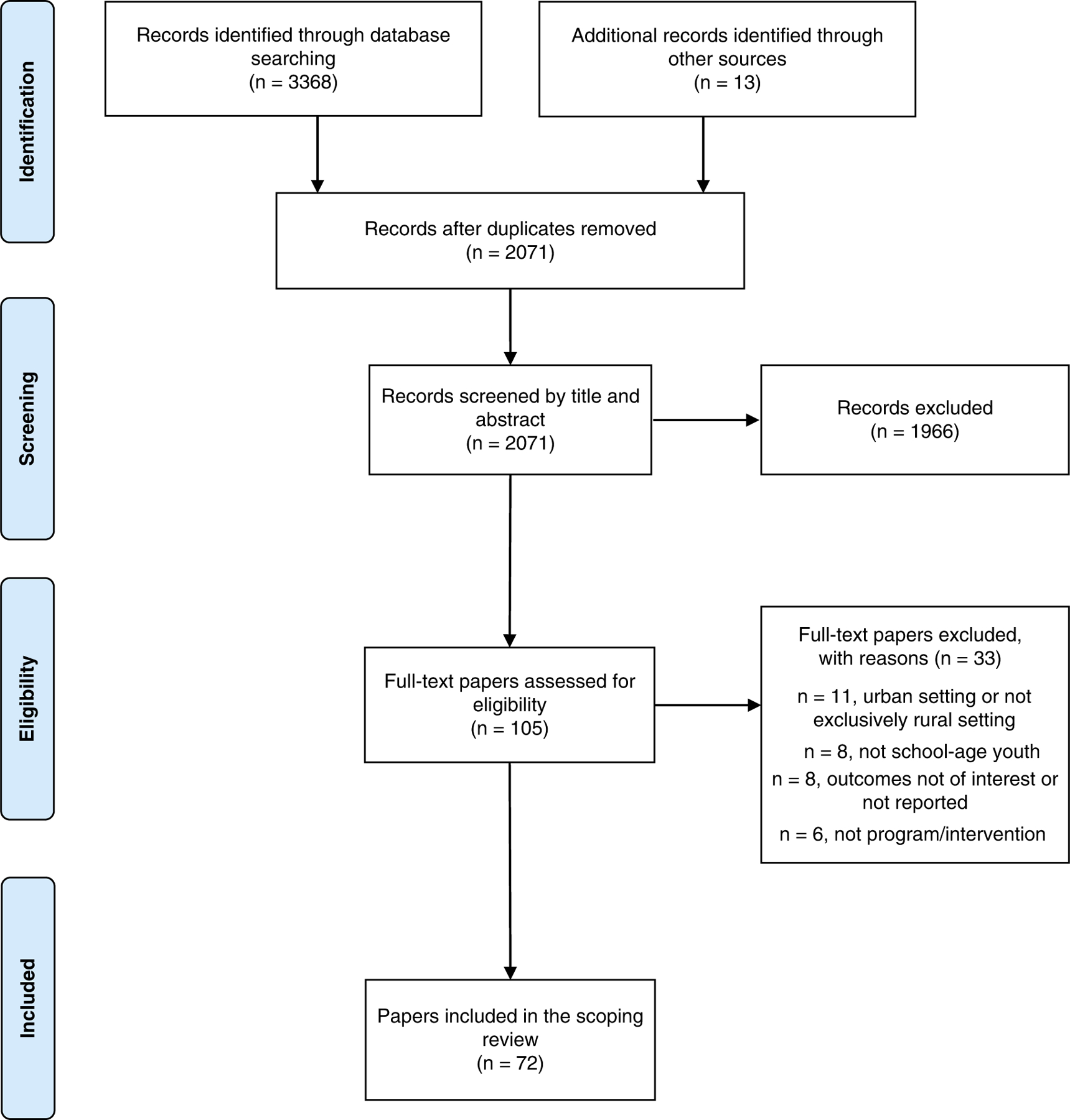

Through database searches conducted in April 2019 and updated in April 2020, 3368 records were identified, and 1310 duplicates were removed. An additional 13 records were identified through reference list searches. A total of 2071 studies were screened by title and abstract for inclusion. Of those, 1966 were excluded. The remaining 105 records were assessed for inclusion based on full-text review, and 33 full-text records were excluded (see Appendix II for reasons for exclusion). The final data set consisted of 72 citations for data extraction. The search results are summarized in a PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1).41

Figure 1:

Search results and source selection and inclusion process41

Characteristics of included sources

Three studies (4.2%) were published in the 1990s,42–44 18 (25.0%) were published between 2000 and 2009,45–62 50 (69.4%) were published between 2010 and 2019,63–112 and 1 (1.4%) was published in 2020.113

Fifty-seven (79.2%) of the studies were conducted in the US,43–55,57–63,65–71,75–81,84,85,87,89–104,106,108,109,113 four (5.6%) in Australia,56,73,107,112 3 in Canada (4.2%),64,74,82 2 in China (2.8%),8,110 1 each in Chile,83 Italy,42 New Zealand,72 Spain,86 and Taiwan,111 and 1 additional study105 that was conducted in multiple countries (US, Australia, and England).

In regard to definition of rurality, most authors reported that participants lived in a rural community or attended a rural school but did not provide a definition of how rurality was identified in their manuscript. Specifically, only 14 articles (19.4%) defined or described how rurality was determined in their manuscript. In terms of study designs, 27 (37.5%) used pre-post designs, 21 (29.2%) implemented a randomized controlled trial (RCT) design, 11 (15.3%) reported using quasi-experimental designs, 5 (6.9%) used qualitative methods,62,67,71,98,107 3 (4.2%) used both pre-post and qualitative designs,48,59,64 3 (4.2%) used cross-sectional designs,42,89,90 1 (1.4%) used both RCT and quasi-experimental designs,105 and 1 (1.4%) study was descriptive.81

Extracted data from each of the included citations are presented in Appendix III.

Review findings

Review question #1: What types of school-based obesity prevention programs have been implemented in rural schools?

Population: children or adolescents

Of the 72 manuscripts, the majority (n = 57; 79.2%) were implemented with children, conceptualized as elementary or middle school students. Additionally, 9 (12.5) studies targeted high school students or adolescents,55,66,69,73,91,99,102,106,113 and 6 (8.3%) were obesity prevention programs that included both children and adolescents (elementary, middle, and high school students).64,74,81,82,88,97

Concept: program type (prevention vs. intervention)

Of the school-based obesity programs, the majority (n = 67; 93.1%) were identified as prevention programs.42–44,46–104,106,108,109,111,112 Four (5.6%) were identified as intervention programs targeting student participants with overweight or obesity, or their engagement in specific health-related behaviors,45,107,110,113 such as reported time engaged in moderate to vigorous PA or recreational screen time.107 One (1.4%) additional study was a systematic review that included a combination of prevention and intervention programs.105

Concept: program providers

Teachers were identified as implementing the obesity prevention program in half of the studies (n = 36; 50%). Of the programs implemented by teachers, 7 were specifically identified as physical education teachers.49,53,59,87,90,100,110 Twelve manuscripts reported researchers or study staff as the primary providers of the obesity prevention program.56,57,60,65,71,74–76,84,104,109,111 Other providers included peers, such as older students serving as mentors (n = 8; 11.1%),54,55,77,82,94,106,107,113 nutritionists or dietitians (n = 7; 9.7%),44,46,61,66,97,105,110 community member volunteers (n = 4; 5.6%),43,49,61,105 members of county extension offices (n = 3; 4.2%),47,61,98 college undergraduate or graduate students (n = 3; 4.2%),44,86,95 trained lifestyle coaches (n = 2; 2.8%),78,85 school nurses (n = 1; 1.4%),95 and other health care professionals (n = 5; 6.9%).46,56,63,69,92 It is important to note that some of the articles reported including multiple types of program providers (eg,66,91); thus, those articles are included more than once in the numbers reported here. However, 13 articles (18.1%) did not provide specific information on who implemented or provided the school-based obesity prevention program in rural schools.51,52,58,62,73,79,81,83,88,89,99,102,112

Review question #2: What specific elements/components of school-based obesity prevention programs have been implemented in rural schools?

Concept: program components

With regard to the program component concept, some of the articles included in this scoping review were categorized as including multiple components; thus, they may be included and discussed under more than one component category.

Exercise/physical activity.

Specific to program components, only 9 (12.5%) studies focused on exercise or PA as an obesity prevention program.53,55,71,87,89,90,100,106,113 Several of the studies also included a PA policy or program evaluation component, such as consistency of schools’ implementation of PA mandates90 and Walk to School Programs.89 Two of the programs focusing on PA also incorporated behavioral components.71,113 The school-based intervention program developed by Smith et al.113 taught self-regulation skills (eg, goal-setting, self-monitoring, time management, self-reward) related to PA in mentored and non-mentored groups. The program by Conway et al.71 consisted of setting goals and keeping logs (ie, behavioral components).

Dietary/nutrition.

Nine (12.5%) of the included studies primarily focused on nutrition or dietary behaviors as the prevention component.42,54,75,79,91,92,97,98,102 Two of the dietary interventions also incorporated behavioral components.79,97 Murimi and colleagues’97 program included medical screening for obesity, diabetes, cholesterol, and high blood pressure; individualized nutrition education and action plans based on screening findings; and group nutrition education classes for rural middle school and high school students. Moss et al.79 implemented nutrition education via the dietary traffic light system and farm tour, and outcomes primarily focused on specific nutritional components, such as fiber and eating vegetables at school.

Combined dietary and physical activity.

Forty-three (59.7%) of the included citations incorporated both nutrition and PA in the school-based obesity prevention program. Seven of the reviewed studies included behavioral components, as well as PA and nutrition, in their prevention programs.48,61,64,70,82,101,111

Policy.

Nine (12.5%) articles focused on policy related to PA or diet as the pediatric obesity prevention component.58,62,69,78,81,85,89–91

Other obesity prevention programs.

Eight (11.1%) articles included in the review did not focus on diet, PA, combination of diet and PA, or policy and were classified as “other.”51,56,63,73,88,105,109,112

As described previously, 12 (16.7%) citations included behavioral components, 7 (9.7%) were in programs with a combined focus on nutrition and PA,48,61,64,70,82,101,111 2 (2.8%) focused on combined nutrition and behavioral components,79,97 2 (2.8%) programs included PA and behavioral components,71,113 and 1 (1.4%) included policy and behavioral aspects.69

Concept: length of prevention programs

The length of the prevention programs was typically implemented according to the school/academic calendar in the rural community. Specifically, 9 out of 72 (12.5%) reported being implemented across 1 school year or 2 academic semesters. In addition, 10 (13.9%) were described as being implemented during 1 semester, 22 (30.6%) reported that the prevention program was less than 1 semester in length, and 1 study74 reported being conducted over more than 1 semester but not the entire school year. Other prevention programs were reported as being conducted over the course of multiple school or calendar years (n = 20; 27.8%). Ten articles (13.9%) did not include information regarding the length of the prevention program described/evaluated.

Review question #3: What outcomes have been reported regarding school-based obesity prevention programs that have been implemented in rural schools?

Concept: outcomes by program components

Exercise/physical activity.

Of the 9 PA programs, 6 examined weight-related outcomes, which were conceptualized as weight, height, BMI, BMI percentiles, BMI z-scores, relative BMI, body fat percentage, or waist circumference. PA-specific outcomes, such as pedometer steps, self-reported PA, and physical fitness, were also included as outcomes in 5 of these programs.53,55,87,89,90 Self-efficacy and barriers to PA were also outcomes included in 3 the programs.53,55,87 Conway and colleagues71 conducted focus groups about their PA and behavioral program; thus, their reported outcomes were qualitative.

Dietary/nutrition.

Of the 9 dietary/nutrition interventions and related policies, 3 included weight-related outcomes42,97,102 and 1 assessed other related health outcomes,97 specifically outcomes from blood work examining cholesterol and triglycerides. Some programs also included nutrition consumption54,75,79,92,102 and/or nutrition knowledge54,75,79,97 as specific outcomes. One of the combined nutrition and policy programs specifically included water and sugar-sweetened beverage consumption as their outcomes of interest.91 In addition to dietary-specific outcomes, Muth and colleagues also included PA-related outcomes in their study.54 Rodriguez and colleagues98 conducted focus groups that qualitatively examined students’ perceptions of a school garden program.

Combined dietary and physical activity.

Of the 43 studies reviewed of combined PA and dietary programs, 33 examined BMI or other weight-related outcomes. In addition, 33 incorporated outcomes specific to PA and diet, 9 included health-related outcomes,44–46,49,60,74,77,94,103 and 5 examined outcomes focused on psychological functioning, such as body image, self-esteem, and depressive symptoms.49,65,82,93,101 Two citations reported qualitative outcomes.64,67 The seven combined PA and nutrition programs that also included behavioral components all examined multiple outcomes.48,61,64,70,82,101,111

Policy.

Three of the policy-focused studies examined weight-related outcomes.69,81,90 Ling and colleagues78,85 implemented a multicomponent, school-level intervention, and focused on PA and dietary behavior outcomes. Three additional citations also included PA- and dietary-specific outcomes to examine policy-related programs. Schetzina and colleagues62 described the design of an obesity-prevention program in response to a new state policy and included outcomes from a qualitative community-needs assessment. Belansky et al.58 included the results of key informant interviews after the implementation of their policy-specific prevention program in rural elementary schools. Ritchie’s69 policy intervention also incorporated behavioral components (eg, cognitive-behavioral skill building), and examined beliefs and perceived difficulties related to healthy lifestyle behaviors.

Other obesity prevention programs.

Five of the other programs incorporated weight-related outcomes.56,73,88,105,112 Some citations also included dietary- and PA-specific outcomes.88,105,109,112 Schiller and colleagues’51 Program ENERGY included outcomes specific to health and science knowledge, and interest in science and health-related careers. Other policy-related programs included outcomes from qualitative interviews with school stakeholders.109,112 Gabriele and colleagues63 described treatment implementation information from an internet educational intervention that incorporated brief behavioral counseling related to weight management depending on the weight status of the student (non-overweight vs. overweight) and only reported implementation related outcomes.

Discussion

Pediatric overweight and obesity are a significant public health burden, and youth in rural areas worldwide are disproportionately impacted. Rural schools are one potential avenue for pediatric obesity prevention and intervention efforts. However, little is known about the components and effectiveness of rural school-based obesity prevention and treatment programs. The purpose of the current scoping was to answer the following questions: i) what types of school-based obesity prevention programs have been implemented in rural schools, ii) what specific elements/components of school-based obesity prevention programs have been implemented in rural schools, and iii) what outcomes have been reported regarding school-based obesity prevention programs that have been implemented in rural schools?

Summary of evidence

We identified 72 citations for inclusion in this scoping review. The majority of the included programs conducted in rural schools were implemented in North America during or after 2010. Among the other studies reviewed, 21 were published before 2009. Five were conducted in Australia or New Zealand, 3 were conducted in Asia, 2 in Europe, 1 in South America, and 1 in multiple countries. Only 14 of the included citations specifically described how rurality was defined or conceptualized in their study. The remaining reported the participants or the schools were located in a rural community.

Review question #1: what types of school-based obesity prevention programs have been implemented in rural schools?

Most of the studies included in this scoping review were implemented with children (elementary and middle school students) and focused on prevention (ie, included children with varying weight status) rather than treatment interventions (ie, included only those who were overweight or obese). Teachers were the primary interventionists, which is not surprising given that the programs were implemented in the school setting. Teachers implementing prevention programs in rural schools could potentially help with program sustainability. The length of the programs implemented in rural schools varied, with most lasting either less than 1 semester in length or over several years.

Review question #2: What specific elements/components of school-based obesity prevention programs have been implemented in rural schools?

The most common elements of school-based obesity prevention programs implemented in rural schools included a combination of nutrition and PA components. Some studies included solely nutrition or PA, and a small number focused on upstream programs aimed at policy changes locally within schools or more broadly with mandates that affected all schools.

Review question #3: What outcomes have been reported regarding school-based obesity prevention programs that have been implemented in rural schools?

Most of the studies reviewed examined multiple outcomes, with weight-related outcomes and PA/nutrition-specific outcomes being the most commonly examined. Several studies reported outcomes from blood work, such as high-density lipoproteins or triglycerides, and some examined psychological outcomes (eg, self-esteem, depressive symptoms), which are associated with pediatric overweight and obesity.

Additional information

While conducting this scoping review, we identified an exploratory interest in understanding characteristics of obesity prevention programs in rural schools that resulted in weight improvements. Therefore, we examined the articles that reported weight changes in more detail. Of the 72 articles included in this review, 14 (19.4%) reported improvements in weight-related outcomes.45,56,57,68,73,82–84,91,95,99,108,110,112 Two of these programs were identified as treatment programs that only included children who were overweight or obese.45,110 The majority of these programs included components focusing on nutrition and exercise, and a few described the inclusion of family involvement and community-based aspects. The programs ranged in length from 2 months to 6 years, but also ranged in intensity from every school day to weekly and monthly implementation.

Overall, conclusions cannot be made from this information because this review did not assess the quality of the research evidence or systematically examine outcomes. There was also variability in the programs that indicated significant improvements in weight outcomes. However, in general, it appears that in rural school-based settings, combined nutrition and PA obesity prevention programs that provide a high dose of prevention/intervention (length, intensity) may be the most effective at impacting weight-related outcomes. Future meta-analytic research is needed to confirm this finding.

Limitations

There are limitations of the current scoping review that are important to consider. First, the lack of information presented in some of the citations made it difficult to determine inclusion/exclusion criteria, as well as to extract data of interest. For example, most of the included citations did not use a specific definition of rurality, but instead the authors reported the school was located in a rural area or community. The definition of what constitutes a rural area is often ambiguous, and standards are not consistent across counties, given that it is often defined by each country differently.32,33 Many definitions of rurality are based on exclusion, such that any area not considered urban is considered rural.35 In addition, our search included “rural” as a term, which may have impacted our ability to include some studies if they were conducted in a rural community but were not identified as such by the authors. Whether the prevention programs were identified as school-based was also at times unclear during the initial citation review. For example, prevention programs that were implemented after school were not included, although they may have been identified as a school-based obesity prevention program by the authors. In addition, extracting specific information about the school-based prevention programs, such as treatment components, was difficult due to limited descriptions or information provided.

Second, we extracted data regarding the providers of the prevention programs but did not extract data on the training the providers may have received or their educational backgrounds. This information would be helpful for those interested in developing obesity prevention programs in rural schools, but it was often not described in the included citations. Also, regarding length of the programs, based on information included in the citations and what was able to be extracted, it was difficult to determine the intensity or dose of the reviewed prevention programs, such as frequency of treatment or hours of prevention/treatment received by students. Because there are specific recommendations regarding pediatric obesity treatment dose (eg, US Preventive Services Task force recommends 26 or more hours of treatment in one year114), this information could be helpful to extract in future scoping and systematic reviews of school-based obesity prevention programs. This could provide additional information regarding the potential impact of dose- and weight-related outcomes and allow comparisons to expert recommendations.

Third, although this information was not specifically intended to be extracted, some authors included information about specific theories that informed their obesity prevention program.66,80,102 For many of the other articles, it was difficult to determine what theories, if any, had guided program development and implementation. It is unclear how this may impact program components or weight-related outcomes in school-based obesity prevention programs in rural communities.

Fourth, although examining the scientific rigor of the included citations was beyond the scope of this scoping review, it is important to consider both the statistical and clinical significance of the findings reported in the included studies. Many of the studies included multiple weight-related, dietary, and PA outcomes requiring multiple statistical analyses and comparisons. Overall, there were limited significant findings across all the reviewed citations, and some of the differences reported could be considered secondary outcomes (ie, the study was not powered to determine differences in specific secondary outcome). Thus, some of the findings could be the result of error due to multiple comparisons. Methodological and statistical rigor of school-based obesity prevention programs in rural communities are needed to guard against exaggerated effectiveness or ineffectiveness of these interventions (for example, see Brown et al.115). Future systematic reviews and meta-analyses are needed to better understand the methodological rigor of research previously conducted in this area.

Conclusions

This scoping review identifies and describes school-based obesity prevention programs that have been implemented in rural communities. Despite the heterogeneity of the programs reviewed, prevention programs that focus on a combination of PA and nutrition appear to be the most common. The length and intensity of the school-based obesity prevention programs reviewed varied. This scoping review provides important directions for future research.

Implications for research

First, future researchers should provide more specific information about obesity prevention programs and the schools and communities where they are implemented. Specifically, understanding how rurality is conceptualized is important because there is increasing recognition that the extent of rurality in the community is associated with poor health outcomes.116 This could impact the implementation and effectiveness of school-based obesity prevention programs. Additionally, there is a need for better reporting of the specific characteristics of programs implemented in rural schools, such as the training of providers, theories that informed program development, specific program components (including behavioral components utilized), and amount of time students are exposed to the prevention program. In addition, it would be helpful for authors to identify what specific aspects of their prevention programs have been modified due to being implemented in a rural location. School-based obesity prevention programs implemented in rural areas could help inform programs in other under-served and under-resourced communities, even if they are not located in a rural community.

Second, because the majority of programs included multiple components, it was difficult to ascertain critical components of school-based obesity prevention programs in rural areas. The studies in this review reported that few (if any) PA, dietary, or policy programs alone impacted weight status. However, more dismantling studies via meta-analyses should be conducted to determine if critical components of these programs can be identified. This would potentially save resources (eg, time, money) as a result of implementing future programs that have limited evidence of success.

Third, more rigorous research designs and outcome assessments should be included in future research, particularly RCTs, and future meta-analyses should focus on synthesizing the specific health- and school-related outcomes of the interventions. In addition, long-term follow-up of outcomes are needed given that weight and other related outcomes may take longer to change after the implementation of prevention programs.

Finally, given the structural nature of conditions that shape health in rural areas, including the increasing risk of obesity in adults and youth, multi-level structural interventions that target root causes of disparities (eg, socioeconomic factors, limited access to physical and mental health care) should be developed and evaluated in under-served rural community-based settings.

Funding

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number 5U54GM115428. The authors participated in the Community Engagement and Outreach Core Working Group, a resource of this award. JR, AG, and CC received funding support though this award. CL received partial funding support through the Federal Office of Rural Health Policy (FORHP), Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) under cooperative agreement award no. 6 U66RH31459-02-03, and partial funding support from NIH/ECHO/ISPCTN 8UG1OD024942-02 and U24 OD02495. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Appendix I: Search strategy

PubMed (US National Library of Medicine)

Search conducted: April 27, 2020

| Search | Query |

|---|---|

| #1 | prevent*[tw] OR intervention[tw] OR program[tw] OR “Health Promotion”[Mesh] OR “health promotion”[tw] |

| #2 | “rural population”[MeSH] OR rural[tw] |

| #3 | schools[MeSH] OR “school based”[tw] OR school-based[tw] OR “school health services”[MeSH] OR school*[tw] |

| #4 | obes*[tw] OR obesity[MeSH] OR “pediatric obesity”[MeSH] |

| #5 | teen*[tw] OR child[tw] OR children[tw] OR “school age”[tw] OR “school aged”[tw] OR child[MeSH] OR “child, preschool”[MeSH] OR adolescent [MeSH] OR adolescen*[tw] OR “high school”[tw] OR “middle school”[tw] OR “elementary school”[tw] OR “pre k”[tw] OR preschool[tw] OR “primary school”[tw] OR youth[tw] OR pediatric[tw] OR paediatric[tw] OR “secondary school”[tw] OR “head start”[tw] OR “nursery school”[tw] OR “Schools, Nursery”[Mesh] |

| #6 | #1 AND #2 AND #3 AND #4 AND #5 |

Limited to English language and years 1990—present

413 results

CINAHL Complete (EBSCO)

Search conducted: April 23, 2020

| Search | Query |

|---|---|

| #1 | prevent* OR intervention OR program OR “health promotion” OR (MH “Health Promotion”) |

| #2 | (MH “Rural Areas”) OR (MH “Rural Population”) OR rural |

| #3 | (MH “Schools”) OR “school based” OR school-based OR school* |

| #4 | obes* OR (MH “Obesity”) OR (MH “Pediatric Obesity”) |

| #5 | (MH “Adolescence”) OR (MH “Child”) OR (MH “Child, Preschool”) OR teen* OR child OR children OR “school age” OR “school aged” OR adolescen* OR “high school” OR “middle school” OR “elementary school” OR “pre k” OR preschool OR “primary school” OR youth OR pediatric OR paediatric OR (MH “Students, High School”) OR (MH “Schools, Middle”) OR (MH “Schools, Secondary”) OR “secondary school” OR (MH “Schools, Elementary”) OR (MH “Students, Elementary”) OR “head start” OR “nursery school” OR (MH “Schools, Nursery”) |

| #6 | #1 AND #2 AND #3 AND #4 AND #5 |

Limited to English language and years 1990—present

255 results

ERIC (EBSCO)

Search conducted: April 23, 2020

| Search | Query |

|---|---|

| #1 | prevent* OR intervention OR program OR DE “Prevention” OR DE “Health Programs” OR DE “Programs” OR DE “Health Promotion” OR DE “Intervention” |

| #2 | rural OR DE “Rural Areas” OR DE “Rural Environment” OR DE “Rural Population” OR DE “Rural Schools” |

| #3 | DE “Schools” OR “school based” OR school-based OR school* |

| #4 | obes* OR DE “Obesity” |

| #5 | teen* OR child OR children OR “school age” OR “school aged” OR adolescen* OR “high school” OR “middle school” OR “elementary school” OR “pre k” OR preschool OR “primary school” OR youth OR pediatric OR paediatric OR “secondary school” OR DE “Adolescents” OR DE “Children” OR DE “Early Adolescents” OR DE “Preadolescents” OR DE “Late Adolescents” OR DE “Youth” OR DE “High School Students” OR DE “Secondary School Students” OR DE “Young Children” OR DE “Preschool Children” OR DE “Middle School Students” OR DE “Middle Schools” OR DE “Secondary School Students” OR DE “Secondary Schools” OR DE “Elementary School Students” OR DE “Elementary Schools” OR “head start” OR “nursery school” OR DE “Nursery Schools” |

| #6 | #1 AND #2 AND #3 AND #4 AND #5 |

Limited to English language and years 1990—present

55 results

Embase (Elsevier)

Search conducted: April 28, 2020

| Search | Query |

|---|---|

| #1 | prevention:ti,ab OR prevent:ti,ab OR ‘prevention and control’/exp OR ‘prevention’/exp OR intervention:ti,ab OR program:ti,ab OR ‘health program’/exp OR ‘health promotion’/exp |

| #2 | ‘rural area’/exp OR ‘rural population’/exp OR ‘rural health care’/exp OR ‘rural health’/exp OR rural:ti,ab |

| #3 | ‘school’/exp OR “school based”:ti,ab OR “school-based”:ti,ab OR school:ti,ab OR ‘school health service’/exp |

| #4 | ‘obesity’/exp OR ‘adolescent obesity’/exp OR ‘childhood obesity’/exp OR obese:ti,ab OR obesity:ti,ab |

| #5 | ‘juvenile’/exp OR ‘adolescent’/exp OR ‘child’/exp OR ‘preschool child’/exp OR ‘school child’/exp OR teen:ti,ab OR teenager:ti,ab OR teenaged:ti,ab OR adolescent:ti,ab OR adolescence:ti,ab OR children:ti,ab OR child:ti,ab OR ‘school age’/exp OR ‘school age population’/exp OR “school aged”:ti,ab OR “school age”:ti,ab OR ‘high school’/exp OR ‘high school student’/exp OR ‘middle school’/exp OR ‘middle school student’/exp OR ‘primary school’/exp OR ‘elementary student’/exp OR “elementary school”:ti,ab OR “pre k”:ti,ab OR ‘preschool’/exp OR ‘preschoolers’/exp OR youth:ti,ab OR pediatric:ti,ab OR paediatric:ti,ab OR ‘secondary schools’/exp OR “head start”:ti,ab OR ‘nursery school’/exp |

| #6 | #1 AND #2 AND #3 AND #4 AND #5 |

Limited to English language and years 1990—present

421 results

Scopus (Elsevier)

Searched conducted: April 28, 2020

| Search | Query |

|---|---|

| #1 | prevent* OR intervention OR program OR “health promotion” |

| #2 | rural |

| #3 | “school based” OR school-based OR school* |

| #4 | obes* |

| #5 | teen* OR child OR children OR “school age” OR “school aged” OR adolescen* OR “high school” OR “middle school” OR “elementary school” OR “pre k” OR preschool OR “primary school” OR youth OR pediatric OR paediatric OR “secondary school” OR “head start” OR “nursery school” |

| #6 | #1 AND #2 AND #3 AND #4 AND #5 |

Limited to English language and years 1990—present

653 results

Academic Search Premier (EBSCO)

Search conducted: April 24, 2020

| Search | Query |

|---|---|

| #1 | prevent* OR intervention OR program OR “health promotion” OR DE “PREVENTION” OR DE “HEALTH promotion” |

| #2 | Rural OR DE “RURAL geography” OR DE “RURAL health” OR DE “RURAL population” OR DE “RURAL schools” OR DE “RURAL youth” OR DE “RURAL teenagers” |

| #3 | “school based” OR school-based OR school* OR DE “SCHOOLS” |

| #4 | obes* OR DE “OBESITY” OR DE “OBESITY in adolescence” OR DE “OBESITY in children” |

| #5 | teen* OR child OR children OR “school age” OR “school aged” OR adolescen* OR “high school” OR “middle school” OR “elementary school” OR “pre k” OR preschool OR “primary school” OR youth OR pediatric OR paediatric OR “secondary school” OR DE “CHILDREN” OR DE “YOUTH” OR DE “ADOLESCENCE” OR DE “TEENAGERS” OR DE “HIGH school students” OR DE “SECONDARY school students” OR DE “HIGH schools” OR DE “MIDDLE school students” OR DE “MIDDLE schools” OR DE “SCHOOL children” OR DE “KINDERGARTEN children” OR DE “ELEMENTARY schools” OR DE “PRIMARY schools” OR DE “PRESCHOOL children” OR DE “SECONDARY schools” OR “head start” OR “nursery school” OR DE “HEAD Start programs” OR DE “NURSERY school education (Great Britain)” OR DE “NURSERY schools (Great Britain)” |

| #6 | #1 AND #2 AND #3 AND #4 AND #5 |

Limited to English language and years 1990—present

557 results

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (Wiley)

Search conducted: April 24, 2020

| Search | Query |

|---|---|

| #1 | prevent* OR intervention OR program OR “health promotion” |

| #2 | rural |

| #3 | “school based” OR school-based OR school* |

| #4 | obes* |

| #5 | teen* OR child OR children OR “school age” OR “school aged” OR adolescen* OR “high school” OR “middle school” OR “elementary school” OR “pre k” OR preschool OR “primary school” OR youth OR pediatric OR paediatric OR “secondary school” OR “head start” OR “nursery school” |

| #6 | #1 AND #2 AND #3 AND #4 AND #5 |

Limited to English language and years 1990—present

95 results

ClinicalTrials.gov

Search conducted on April 24, 2020

| Search | Query |

|---|---|

| #1 | Advanced Search: |

| Condition or disease: obesity | |

| Other terms: school AND rural | |

| Study type: All | |

| Study results: All | |

| Age: Child | |

| Sex: All |

Study Start: From 01/01/1990-present

10 results

ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Sciences and Engineering Collection (ProQuest)

Search conducted: April 23, 2020

| Search | Query |

|---|---|

| #1 | Exact(“Rural” OR “RURAL” OR “Rural adolescents” OR “rural populations” OR “rural adolescents” OR “rural” OR “Rural adolescent females” OR “Rural population” OR “Rural populations” OR “Rural schools”) AND (obesity OR obese) AND (teen* OR child OR children OR “school age” OR “school aged” OR adolescen* OR “high school” OR “middle school” OR “elementary school” OR “pre k” OR preschool OR “primary school” OR youth OR pediatric OR paediatric OR “secondary school” OR “head start” OR “nursery school”) AND (“school based” OR school-based OR school*) |

Limited to English language and years 1990—present

207 results

OpenGrey (opengrey.eu)

Search conducted: April 23, 2020

| Search | Query |

|---|---|

| #1 | (prevention OR intervention) AND rural AND school AND (obesity OR obese) AND (child OR children OR teen) |

Limited to English language and years 1990—present

0 results

Open Access Theses and Dissertations (oatd.org)

Search conducted: April 23, 2020

| Search | Query |

|---|---|

| #1 | (prevention OR intervention) AND rural AND school AND (obesity OR obese) AND (child OR children OR teen) |

Limited to English language and years 1990—present

22 results

Directory of Open Access Journals (doaj.org)

Search conducted: April 23, 2020

| Search | Query |

|---|---|

| #1 | (prevention OR intervention) AND rural AND school AND (obesity OR obese) AND (child OR children OR teen) |

Limited to English language and years 1990—present

21 results

PapersFirst (OCLC)

Search conducted: April 23, 2020

| Search | Query |

|---|---|

| #1 | (prevention OR intervention) AND rural AND school AND (obesity OR obese) AND (child OR children OR teen) |

Limited to English language and years 1990—present

0 results

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (MedNar)

Search conducted: April 24, 2020

| Search | Query |

|---|---|

| #1 | prevention AND rural AND school-based AND obesity AND child |

Limited to English language and years 1990—present

99 results

US Department of Education (ed.gov)

Search conducted: April 23, 2020

| Search | Query |

|---|---|

| #1 | prevention AND rural AND school-based AND obesity AND child |

Limited to English language and years 1990—present

560 results

Appendix III: Characteristics of included studies, organized by program components

| Study, year, location | Method of rural designation | Study type (design) | Intervention components | Intervention frequency/length | Provider | Sample | Type of outcomes | Key findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exercise/physical activity (n = 9) | ||||||||

| Conway et al.71 2012 US (North Dakota) | Author reported rural county | Prevention (qualitative) | PA (and behavioral)a | 5 weeks in winter | 3 member evaluation team | N = 81 5th and 6th grade students |

5 focus groups, qualitative data | Students thought setting goals and keeping logs supported participation in PA; logs helpful but not consistently completed; some students wanted them to be electronic but also to be private; described support from parents and teachers and role models; increasing level and variety of PA was recommendation for change. |

| Eichner et al.100 2016 US (Oklahoma) | Author reported rural school | Prevention (pre-post design) | PA | 2 school semesters (daily PA on school days) | PE teacher | N = 66 Middle school: 6th, 7th, and 8th grade students, 12–15 years old |

BMI z-scores pre- and post-assessments | Significant group differences in BMI z-scores, with participating students staying the same and nonparticipating students increasing; BMI decreased among boys who participated and was stable among girls. |

| Manley53 2008 US (Kentucky) | Author reported rural | Prevention (RCT) | PA | 12 weeks (wore pedometer every day and 10 minutes of moderate to vigorous PA) | PE teacher | N = 116 6th and 7th grade students Intervention n = 55 Control n = 61 |

Self-efficacy levels, PA (pedometers), aerobic fitness (1 mile walk test), and body composition (height, weight, BMI, BMI %ile, relative BMI) pre- and postassessments | No Tx effects—no statistical difference between Tx and control school; Tx school had significantly higher weight status (BMI and relative BMI); Tx school had significantly lower PA and aerobic fitness compared to control school; noteworthy that Tx group had greater improvements in self-efficacy, aerobic fitness levels, and relative BMI than control group. |

| Manley et al.87 2014 US (Kentucky) | Author reported rural | Prevention (RCT) | PA | 12 weeks (wore pedometer every day and 10 minutes of moderate to vigorous PA) | PE teacher | N = 116 11- and 13-year-olds (mean age 11.7 years) Intervention n = 55 Control n = 61 |

Self-efficacy levels, PA (pedometers), aerobic fitness (1 mile walk test), and body composition (BMI, BMI %ile, relative BMI) pre- and postassessments | No significant difference between Tx and control groups; those with optimal relative BMI levels had higher self-efficacy, PA, and aerobic fitness levels. Although not statistically significant, Tx group had greater improvements in mean self-efficacy scores, aerobic fitness levels, and relative BMI. |

| Oluyomi et al.89 2014 US (Texas) | Definition not included (home addresses were geocoded) | Prevention (cross-sectional) | PA (and policy)b | 5-year implementation project | Not described | N = 830 parent-student dyads (4th grade) | Self-reported child walking to school; perceived traffic and personal safety concerns for neighborhood, en route to school, school environments; social capital | Odds of walking to school were higher with no problems related to traffic speed, amount of traffic, sidewalks, intersection safety, crossing guards; odds of walking to school were lower with stray animals and concerns with no walking partner. |

| Robinson et al.90 2014 US (Alabama) | Author reported 1 county in Black Belt Region | Prevention (cross-sectional) | PA (and policy)b | Daily PE for 30 minutes | Certified PE instructor | 5 elementary schools; N = 683 school-age children (341 female; 342 male); mean age 8.22 years; 99.9% Black | BMI; weight status; waist circumference; PA behavior (pedometer step count, System for Observing Fitness Instruction Time, and the System for Observing Play and Leisure Activity in Youth) | Overall, PE and PA state-level policies were only partially implemented; large discrepancy between what is scheduled at school level and what is actually being implemented; PA during PE was students’ only opportunity for school PA. |

| Rye et al.55 2008 US (West Virginia) | Definition not included; state is in Appalachia and ranks 3rd highest among all states on % rural population | Prevention (pre-post design) | PA | 2 academic years | 2 secondary teachers and high school students | Y1, N = 16 Y2, N = 15 + 3 repeaters from Y1, faculty, staff, parents, community members High school focus group: Health Sciences and Technology Academy students Y1, N = 12 Y2, N = 5 Adult focus group participants: teachers, parents, community members | Daily step count (pedometer); perceptions of barriers to PA; self-efficacy; outcome expectations | Pre to post-decreases in Y2 mean scores were statistically significant for total barriers, as well as lack of energy, time, and willpower. |

| Smith et al.113 2020 US (Ohio) | Author reported rural Appalachian high schools in Southern Ohio (based on population density, housing, and territory) | Intervention (RCT) | PA (and behavioral)a | 10 weeks (10 40-minute weekly lessons) | Trained peer mentors and teachers | N = 190 (n = 106 obese and n = 84 extremely obese) in 9th-11th grades Mean age 15.03 years (standard deviation = 0.84) | Conducted baseline, 3-month follow-up, and 6-month postintervention of raw body weight, height, BMI, body fat %, BMI % | All youth lost an average of 7.3 lb from baseline to 3-month follow-up and 10.8 lb from baseline to 6-month follow-up; Obese Mentored Planning to be Active group lost 77.5% more weight by 6-month follow-up compared to the Planning to be Active group. Extremely obese in the Mentored Planning to be Active group lost 80% more weight compared to the Planning to be Active group. Extremely obese females lost more weight compared to males; BMI and body fat had similar results; youth in the Mentored Planning to be Active group had most improvements. |

| Smith et al.106 2018 US (Ohio) | School districts in rural Appalachia counties | Prevention (RCT) | PA | 10 40-minute sessions (2 possible sessions each week) | Teachers and trained teen mentors | N = 654 9th and 10th graders N = 119 older peer mentors N = 8 teachers N = 20 schools |

BMI, height, weight | Peer-to-peer mentoring by local high school students and school-based tailored support strengthens sustainable behavioral change. |

| Dietary/nutrition (n = 9) | ||||||||

| Angelico et al.42 1991 Italy (Sezze Romano) | Author reported small town (70 miles outside Rome) | Prevention (cross-sectional) | Nutrition | 5 years (3 teacher trainings, 6 parent/community interactions); frequency of nutrition education in classroom unclear | Trained school teachers | N = 150 children aged 6–7 years attending rural elementary school | Height, weight, BMI | Height, weight, and BMI increased over time. |

| Moss et al.79 2013 US (Illinois) | US Department of Agriculture Rural designation | Prevention (pre-post design) | Nutrition (and behavioral)a | 4-week intervention (2 30-minute lessons one week apart; 120-minute farm tour in week 4) | Unclear | N = 65 3rd grade students from one elementary school |

Nutrition knowledge; fruit/vegetable consumption, farm exposure; Go, Slow, Whoa foods | Positive eating fiber, fruits/vegetables contain vitamins, eating more vegetables at school; non-significant relationship between fruit/vegetable and farm tour. |

| Murimi et al.97 2015 US (Louisiana) | Definition not included | Prevention (pre-post design) | Nutrition (and behavioral)a | Screening and point-of-testing counseling sessions offered every 6 months for 3 years; 6 possible testing and counseling session opportunities; 2040 minutes per counseling session; nutrition education 1 hour/week for 12 weeks | Registered dietitian, registered nurse, dietetic students | N = 233 6th-12th grade students (11–19 years old), 51% female, 58% White, 51% overweight or obese |

BMI, BP, total cholesterol, HDL, LDL, triglycerides, student food knowledge | Significantly increased HDL and nutrition knowledge (7th and 8th grade), non-significant but stabilized weight and blood values. Participants who attended 4 sessions maintained their weight at 76th %ile; highest-risk participants, systolic BP, total cholesterol, and triglycerides lowered. |

| Muth et al.54 2008 US (North Carolina) | Definition not included | Prevention (RCT) | Nutrition | 12-week curriculum, 60-minute lessons; 15-hour high school student training | Peer modeling by medical and high school students | 1 high school; 8 students trained as health educators, 10 medical students 1 elementary school, 4th grade classrooms, 2 intervention (38 students) and 2 control (37 students) classrooms |

Nutrition servings per day: fruit/vegetable, calcium foods, grains, sweet beverages, fried foods, sweets; nutrition knowledge and attitudes, PA score, sedentary score | Increased fruit/vegetable intake and nutrition knowledge. |

| Nanney et al.102 2016 US (Minnesota) | 50% rural town fringe and 50% rural using National Center for Education Statistics and rural-urban commuting area codes | Prevention (RCT) | Nutrition | 1 academic year; School Breakfast Expansion Team met 5 times; Tx or delayed Tx; block randomization with 4 Tx and 4 control in each wave | School personnel implemented school-level changes; no other detail about provider | 8 schools in Wave 1; 3 schools in Wave 2; all 9th and 10th graders screened for eligibility; 904 enrolled; 54% girls and 30% non-White | Increase systolic BP participation (primary), diet quality, intention to eat school breakfast; decrease calories, BMI, body fat | Community-based approach to translate best practices; study successfully recruited 16 schools and exceeded student enrollment; few results on the intervention; schools did initiate a second chance grab and go breakfast. |

| Rodriguez et al.98 2015 US (Florida) | Author reported Florida Panhandle | Prevention (qualitative) | Nutrition | Not provided | Florida A&M Extension agents | N = 60 3 focus groups; 20 participants per group; 9–12 years |

Student thoughts, feelings, and perceptions of school garden program | Students reported greater technical knowledge and liked spending time outside; talked about growing vegetables and opinions of the different vegetables grown; some participants described having tried new vegetables; however, participants did not speak about an increase in household vegetable consumption. |

| Smith et al.91 2014 US (Ohio) | Author reported a rural Appalachian county | Prevention (pre-post design) | Nutrition (and policy)b | 30-day | Teen Advisory Council (teachers and students from 9th-12th grades) | N = 186 high school students in 9th-12th grades from 2 schools (mean age = 15.85 years) |

Sugar-sweetened beverage consumption and water consumption: pre, post, and 30-day follow-up | Sugar-sweetened beverage consumption decreased significantly, and water consumption increased 19% from baseline to post-intervention. |

| Struempler et al.92 2014 US (Alabama) | Participants from schools eligible for SNAP-Ed, with over 50% students receiving free or reduced-price lunch | Prevention (pre-post design) | Nutrition | Weekly for 17 weeks, 45-minute classes | SNAP-Ed educators | N = 2477 3rd grade students eligible for SNAP-Ed |

Fruit and vegetable consumption during lunch (self-reported food consumption) | School-based childhood obesity prevention programs as means to moderately increase fruit and vegetable consumption through the school lunch program. |

| Tussing-Humphreys et al.75 2012 US (Mississippi) | Author reported “rural Lower Mississippi Delta” Hollandale, MS | Prevention (pre-post design) | Nutrition | 3 times per week over a 6-week period | Research staff, teachers | N = 187 4th-6th graders completed the study |

Fruit and vegetable recognition, willingness to try, and fruit and vegetable consumption pre- and postintervention | A fruit and vegetable snack feeding intervention can increase familiarity, and potentially, the amount of fruits and vegetables consumed by school children. |

| Combined nutrition and physical activity (n = 43) | ||||||||

| Bergan77 2013 US (South Dakota) | Author reported “rural” students (125-mile radius from Brookings, South Dakota) | Prevention (RCT) | Combined nutrition and PA | 6-month program; 6 40-minute lessons (6-month follow-up assessment) 2 interventions compared to control: KidsQuest (Intervention 1) and KidsQuest plus Family Fun Packs and Take 10! Activities (Intervention 2) | Trained teen teachers | N = 91 5th and 6th grade students. Mean age ranged from 10.85 to 11.04 years (128 invited to participate, 91 started the program, and 79 completed the whole study) |

Total cholesterol, triglycerides, LDL, HDL, BMI (assessed pre-, post-, and 6 month [12-month] follow-up) | No significant group difference in total cholesterol, triglycerides, and HDL from pre to post and pre to follow-up; significant decrease in LDL from pre to post in Intervention 2 group; significant increase in BMI for Tx Group 1 pre to post and pre to follow-up for Tx groups 1 and 2. |

| Brown103 2018 US (Washington) | Author reported rural community in eastern Washington | Prevention (quasi-experimental) | Combined nutrition and PA | 6 months | Teachers; provider of child and family intervention unclear | N = 665 (Tx = 282, control = 383) 3rd-5th grade students N = 205 (Tx = 104 and control = 101) 3rd and 4th graders assessed for nutrition and PA for comparison |

Height, weight, BMI z-scores, dietary intake, PA, sedentary behavior (assessed baseline and 6-month follow-up) | Significant improvement in light and moderate PA for the intervention group compared to control group from pre- to postassessment, and significant decrease in moderate and vigorous PA in control group; no significant group difference in dietary behaviors (fruit, vegetable, and sugar consumption) or sedentary behavior. |

| Bumaryoum94 2015 US (South Dakota) | Author reported rural schools | Prevention (RCT) | Combined nutrition and PA | 6 50-minute sessions over 4–6 months | Trained teen teachers and SNAP-Ed educators | N = 254 5th and 6th grade students |

Nutrition, PA, BMI (height, weight), BP, total cholesterol, HDL, hemoglobin (assessed pre and 6 months after initiation) | No significant change in BMI, BP, total cholesterol, HDL, hemoglobin. Significant reduction in eating candy in intervention groups and increases in whole grain consumption. |

| Canavera et al.59 2009 US (Kentucky) | Author reported rural Kentucky | Prevention (qualitative and pre-post design) | Combined nutrition and PA | 12-week intervention (plus focus groups conducted before) | PE and health teachers (no specialized training) | N = 122 5th grade students (mean age not reported) N = 36 focus group parent and child dyads |

PA, watching TV, drinking water, eating fruits and vegetables (pre- and post-assessments); focus group data | Generally no significant pre-post difference with exception of significant pre-post differences for expectations for watching TV, expectations for drinking water, and number of glasses of water consumed. |

| Carrel et al.45 2005 US (Wisconsin) | Author reported rural | Intervention (RCT) | Combined nutrition and PA | 5 times every 2 weeks for 45 minutes; 9 months (school year) | Instructors | N = 50 obese middle school students (mean age 12 years) |

BMI, fasting glucose, insulin, body fat, fat-free mass, cardiovascular fitness (maximal oxygen consumption) | Compared with the control group, treatment group had significant decrease in body fat %, significant improvements in cardiovascular fitness, and significant improvement in fasting insulin level. |

| Cason et al.47 2006 US (South Carolina) | Author reported rural underserved communities | Prevention (quasi-experimental) | Combined nutrition and PA | 7 1-hour sessions over 14 weeks | University Cooperative extension educator | N = 130 4th grade students (mean age 9 years); n = 72 control, n = 58 intervention |

PA and dietary intake knowledge and behavior, 21 items (pre, post, and 5-month follow-up) | Significant group differences (Tx group better) in washing hands, choosing healthy snacks, eating vegetables every day, trying new foods, thinking about foods being healthy, doing moderate PA, working on getting stronger, PA until sweating, exercising or dancing during TV commercials, enjoying being physically active, matching muscle group to body parts, keep-away strategies. |

| Craven et al.66 2011 US (North Carolina) | Author reported rural high schools | Prevention (quasi-experimental) | Combined nutrition and PA | 4 90-minute lessons (6 hours) of nutrition education and 6 hours of PA instruction in one semester | Nutritionist and classroom teacher | N = 399 9th graders (mean age = 14.7 years) N = 214 Tx group and N = 185 control group |

Height, weight, BMI, self- reported eating behaviors (fruits, vegetables, dairy, sweet beverages, fast food), pre and post | No significant group difference in mean BMI change, but mean BMI decreased in Tx group; increases in fruit and vegetable intake for intervention group but not statistically significant (P = 0.09 and 0.08). |

| Culbertson49 2007 US (Colorado) | Author reported rural | Prevention (quasi-experimental) | Combined nutrition and PA | Bimonthly classroom; 1 hour long; 11 hours total intervention time; 2 years | Grad student and community volunteers (PE teacher, high school and nursing students, police officer, veterinarian) |

N = 82 2nd and 3rd graders; Cohort A = 37 2nd graders completing Year 1, Cohort B = 40 3rd graders completing Year 2, Cohort C = 29 2nd and 3rd graders who completed both years |

Food and PA knowledge, attitude and behavior, BMI, waist circumference, body image, pedometer step counts; pre- and post-assessments | Significant improvement in PA attitude and knowledge in Tx group compared to control group; significant improvement in dietary intake pre- and post-Tx group but no significant difference from control group; significant improvement in body image especially for females in Tx group; overall no significant change in BMI z-score; no significant group differences in pedometer steps. |

| Davis et al.43 1993 US (New Mexico) | Author reported rural schools | Prevention (RCT) | Combined nutrition and PA | 5 units; 18 hours of curriculum in one semester | Classroom teachers, older members of community | N = 1543 5th grade students, 9–13 years old (participated over 5-year period) |

Health knowledge and attitudes, dietary habits, exercise behavior; height, weight, BMI, skin folds; pre and post | Significant improvement in overall knowledge in intervention schools vs. control schools; significant increase in exercise in intervention vs. control schools; significant decrease in use of butter or tortillas in intervention vs. control schools. |

| Donnelly et al.44 1996 US (Nebraska) | Author reported rural | Prevention (quasi-experimental) | Combined nutrition and PA | 2 years; nutrition: 18 modules (9 modules per school year) PA: 3 days per week for 30–40 minutes |

Existing classroom teachers | 3rd and 5th grade elementary school students; N = 200 to collect lab data | Aerobic capacity, body composition, blood chemistry, nutrition knowledge, energy intake, and PA | No significant difference in Tx and control schools in weight, BMI, fat %, maximal oxygen consumption, BP, insulin, or glucose; via 24-hour recall, students in Tx schools consumed significantly less sodium vs. control schools at post; no other significant dietary difference, although lunches had less fat, sodium, and total energy; HDL cholesterol and the ratio of cholesterol to HDL significantly improved for Tx vs. control group; Tx group significantly more active at school but significantly less active outside of school vs. control schools. |

| Gittelsohn and Rowan67 2011 US (Native American) | Author reported rural areas (American Indian and First Nation communities) | Prevention (qualitative) | Combined nutrition and PA | Unknown | Teachers | Elementary schools; 3rd-5th grade |

Qualitative/descriptive | Positive change in psychosocial measures and improvements in diet; no significant improvements in PA or obesity (primary outcome). |

| Gombosi et al.50 2007 US (Pennsylvania) | Author reported rural county | Prevention (pre-post design) | Combined nutrition and PA | 5 years | Teachers, guest teachers, health curriculum coordinator | N = 4804 K-8th grade (ages 5–14 years) | BMI %, health assessments at health fairs; pre- and postassessments | Minority of teachers used provided kits; increased incidence of overweight and obesity over time; no treatment effect. |

| Hao et al.110 2019 China | Author reported rural (one district of Benxi City, Liaoning Province, in Northeast China) | Intervention (RCT) | Combined nutrition and PA | Exercise Tx: every school day for 30 minutes for 2 months; skipping rope, 3 times for 10 minutes; nutrition education, 8 45-minute meetings for 2 months (total of 6 hours) | Nutritionist, PE teacher | N = 229; n = 104 girls, n = 125 boys Overweight or obese primary school children 9–12 years of age | Anthropometric assessments (weight, height), dietary survey, nutrition knowledge, daily energy intake at baseline, after 2 months Tx (post), and 1 year follow-up | Compared to baseline, BMI significantly decreased for all 3 groups at post-intervention and follow-up; nutrition knowledge significantly improved for 2 groups who received nutrition education at both post-Tx and follow-up vs. baseline; significant decrease in energy intake post-Tx and follow-up in those who received nutrition education; significant changes in BMI standard deviation scores in exercise and nutrition education intervention, nutrition education intervention, exercise intervention, and control groups, from highest to lowest; combination Tx had best short- and long-term outcomes. |

| Harrell et al.46 2005 US (Mississippi) | Author reported rural southern community (Scott County, MS) | Prevention (quasi-experimental) | Combined nutrition and PA | 16 weeks; 4 monthly sessions | Health care Professionals (pediatrician, pharmacist, Exercise physiologist, and registered dietitian) |

N = 205 5th graders (mean age 11.9 years) |

Health knowledge, height, weight, BMI, body fat %, waist circumference, dietary intake, blood lipids, blood glucose, and BP; pre and post test | Students in intervention school increased health knowledge compared to control school; significant increases in height, weight, and waist circumference over time; significant increase in vegetable consumption and decrease in soft drink consumption in Tx group compared to control group; no significant difference in other outcomes. |

| Harwood60 2009 US (Ohio) | Author reported rural Appalachia (federally designated, <2500 people) | Prevention (quasi-experimental) | Combined nutrition and PA | 16 weeks: 6 45–60 minutes each (child part); parents (3 nutrition education, 5 packets); rowing twice a week for 30 minutes for 16 weeks | Research teachers |

N = 35 (n = 19 Tx group and n = 16 control group) 2nd grade students (7 and 8 years old) |

Dietary behaviors (nutrients, food groups): 3-day food log, height, weight, BMI, body fat % (skin fold), exercise test (aerobic fitness, BP, heart rate, respiratory function); pre- and postassessments | Children in Tx group significantly increased milk and magnesium compared to control group; no other significant difference in nutrition; no significant difference between groups in BMI and body fat %. |

| Hawkins et al.104 2018 US (Louisiana) | Author reported rural | Prevention (RCT) | Combined nutrition and PA | 28 months | Research personnel | N = 1626 4th-6th graders (mean age = 10.5 years); n = 1195 Tx and n = 431 control |

Sodium, added sugars in lunches (baseline, 18 months, and 28 months); food selection and consumption based on digital photography | No significant group difference in energy intake at 18 months, but at 28 months, Tx group consumed significantly fewer kcals; at 18 months, sodium selection and consumption significantly increased in control group vs. Tx group and at 28 months, control group consumed more sodium compared to the Tx group; at 18 months, added sugar consumption increased in control group compared to Tx group and at 28 months, added sugar consumption significantly decreased in Tx group vs. control group; plate waste did not decrease. |

| Hawley et al.48 2006 US (Kansas) | Author reported rural | Prevention (qualitative and pre-post design) | Combined nutrition and PA (and behavioral)a | Five 40-minute session classroom program over 6 weeks | Unclear | N = 65 6th graders (and 25 families) 11–12 years old |