Abstract

Chiral Ni complexes have revolutionized both asymmetric acid–base and redox catalysis. However, the coordination isomerism of Ni complexes and their open-shell property still often hinder the elucidation of the origin of their observed stereoselectivity. Here, we report our experimental and computational investigations to clarify the mechanism of β-nitrostyrene facial selectivity switching in Ni(II)–diamine–(OAc)2-catalyzed asymmetric Michael reactions. In the reaction with a dimethyl malonate, the Evans transition state (TS), in which the enolate binds in the same plane with the diamine ligand, is identified as the lowest-energy TS to promote C–C bond formation from the Si face in β-nitrostyrene. In contrast, a detailed survey of the multiple potential pathways in the reaction with α-keto esters points to a clear preference for our proposed C–C bond-forming TS, in which the enolate coordinates to the Ni(II) center in apical–equatorial positions relative to the diamine ligand, thereby promoting Re face addition in β-nitrostyrene. The N–H group plays a key orientational role in minimizing steric repulsion.

Introduction

Chiral Ni(II)–enolates have been widely utilized to explore catalytic asymmetric α-functionalization of carbonyl compounds.1−3 Our group has proven the synthetic utility of Ni(II)–enolates through the development of catalytic asymmetric halogenations,4,5 Michael reactions,6 and (3+2) cyloadditions.7−9 The key to the success of these catalytic transformations is soft enolization; Ni(II) is believed to act as a Lewis acid to activate the carbonyl substrate, thereby enhancing the deprotonation process even with the use of a relatively weak Brønsted base.10 However, despite substantial progress in asymmetric Ni catalysis,1−9 structural and mechanistic studies of Ni(II)–enolates remain conspicuously scarce.7−9,11−14 The difficulty arises from several inherent factors in Ni(II)–enolates. First, considering the coordination isomerism that occurs in Ni(II)–enolates, several distinct diastereomeric transition states (TSs) are possible.8,9 Second, the open-shell property of these complexes often impairs NMR kinetic analysis, thereby making it difficult to characterize the stereodetermining TSs even when using DFT calculations. In addition, if we consider the Ni/ligand bifunctional activation mechanism,15−19 we also have to carefully evaluate the dispersive interactions in the TSs.20−23 Thus, mechanistic studies of Ni catalysis are not only attractive for the replacement of noble metals but also challenging in rationalizing the reactivity and selectivity in Ni(II) catalysis.24−26

Isolating chiral Ni catalysts is undoubtedly a critical step in characterizing their structural properties in the ground state. In 2005, Evans and Seidel reported the development of the Michael reaction of nitroalkenes 1 with 1,3-dicarbonyl compounds 2 using Ni(II)-bis[(R,R)-3a]Br2 (Scheme 1, i).11 In 2007, they proposed an octahedral C–C bond-forming TS model based on the X-ray structure analysis of the related Ni(II)–diamine–enolate complex (CCDC 666221).12 They proposed that the nitroalkene approaches from the open apical position at the Ni(II) center. A plausible steric repulsion between the ligand and nitronate in the disfavored TS (pro-R addition) was also used to explain the observed S selectivity in the resulting Michael adduct, 4. Recently, Shiryaev et al. computationally validated the feasibility of the Evans octahedral TS model with a simplified ligand and counteranion, although the enolate formation step and other possible competitive reaction pathways were not systematically investigated.13 In addition, Chusov et al. proposed that the addition of a fluoride source to the NiBr2–diimine14 (or NiBr2–diamine27) complex generates a more active NiBrF–diimine complex.14 Their computational analysis suggested that the fluoride enhances the deprotonation process and the resulting HF acts as the H-bond donor to reduce the energy of the C–C bond-forming TS; this was in good agreement with the observed rate acceleration. However, the computational model could not account for the observed enantioselectivity in the Michael reaction of β-nitrostyrene with dimethyl malonate when they performed the computational analysis with a chiral diimine ligand. On the basis of our previously reported Ni(II)–enolate chemistry,4−9 we planned to examine the reaction pathways with a different set of substrates.

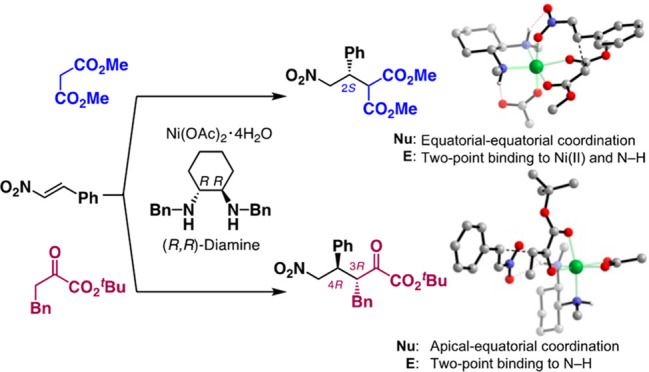

Scheme 1. (i) Catalytic Enantioselective Michael Reaction of Nitroalkenes with Malonates and (ii) Catalytic Enantioselective and anti-Selective Michael Reaction of Nitroalkenes with α-Keto Esters.

During our studies, we encountered pro-nucleophile-dependent selectivity switching in the Ni–diamine–(OAc)2-catalyzed asymmetric Michael reaction,6 even when using the same ligand that was used by Evans, i.e., (R,R)-3a (Scheme 1, ii).11,12 While C–C bond formation occurs through the Si face of 1 with malonates 2 under Evans conditions,11,12 our reaction with α-keto ester 5(3,28) proceeded through the Re face of 1.6 Such substrate-dependent selectivity switching in metal–enolate chemistry29−32 has been sporadically reported; however, the mechanistic origin has not often been computationally rationalized. Guided by our recent mechanistic studies of Ni(II)-catalyzed (3+2) cycloadditions,7−9 we postulated that facial selectivity switching in the nitroalkene could be explained by the difference in (1) the coordination structure of the octahedral Ni(II) complex and (2) the combined activation mode of the nitroalkene. The asymmetric Michael reaction33 has been frequently used as a benchmark test to evaluate the catalytic performance of a transition metal with a chiral1,9,22,33−35 or achiral ligand.35−38 The critical importance of the metal-bound N–H functionality has been recognized15−17 since the metal–ligand bifunctional mechanism in the asymmetric hydrogen transfer reaction was initially characterized in 2000 on the basis of early computational studies.39 Meanwhile, the cooperative effect between the coordination geometry in the metal–enolate complex (inner-sphere activation mode)37,38,40−42 and ligand-enabled H-bonding interaction (outer-sphere activation mode)15−17 has not been systematically analyzed. Thus, as a model study to determine how these two factors may regulate the stereodiscrimination process, we sought to clarify the origin of pro-nucleophile-dependent selectivity switching in the Ni–diamine–(OAc)2-catalyzed asymmetric Michael reaction. To differentiate the two different coordination patterns in the TSs, we refer to the stereochemical model in which the enolate binds in the same plane with the diamine ligand as in the Evans model, regardless of the structure of the nucleophile. On the contrary, the mode in which the enolate generated from the malonate or α-keto ester coordinates to the Ni(II) center in apical–equatorial positions relative to the diamine ligand is defined as in our model. Herein, on the basis of our experimental and computational studies, we propose that the reaction with malonates 2 mainly proceeds via the Evans TS, wherein the enolate occupies the same plane as the diamine ligand. On the contrary, the reaction with α-keto ester 5 predominantly occurs in our originally proposed C–C bond-forming TS, in which the enolate occupies the Ni(II) center in the apical–equatorial positions relative to the diamine ligand. Our computational analysis suggests that the N–H group on the ligand serves as a directing group, which enables control of the reaction face of β-nitrostyrene.

Results and Discussion

Experimental Investigations

Our optimal catalytic system is slightly different from that reported by Evans.11,12 In our proposed reaction with α-keto esters 5, the use of Ni(OAc)2 in THF is essential for attaining high reactivity and selectivity. When we used the Ni(II)-bis[(R,R)-3a]Br2 system developed by Evans under our optimal conditions,11,12 almost no reaction occurred.6 Therefore, we began this study by evaluating the reaction of 1a with malonates 2 under our optimal conditions (Scheme 2). Similar to the Ni(II)-bis[(R,R)-3a]Br2 system developed by Evans,11,12 our catalytic system, prepared from Ni(OAc)2·H2O and (R,R)-3ain situ, also promoted Michael reaction. With regard to enantioselectivity, we found that the substituents in the ester group in 2 significantly influenced the enantiomeric excess (ee) in 4 [with 2a (R = Me), 95%, 75% ee; with 2b (R = iPr), 95%, 90% ee]. Most importantly, each absolute stereochemistry in the major adduct, 4, was assigned as S by comparing the optical rotation with the value under the precedence conditions (see the Supporting Information).11,43 In sharp contrast, the reaction of α-keto ester 5a with 1a afforded the corresponding Michael adduct (3R,4R)-6aa in 82% yield with >20/1 dr and 92% ee. The absolute stereochemistry of 6aa was determined by X-ray crystallographic analysis of 6aa (CCDC 752633).6 These results clearly prove that the facial selectivity in 1 is drastically switched depending on the structure of the pro-nucleophile, even under our catalytic conditions using Ni(OAc)2·H2O and (R,R)-3a.

Scheme 2. (i) Catalytic Enantioselective Michael Reaction of 1a with 2 and (ii) Catalytic Enantioselective and anti-Selective Michael Reaction of 1a with 5a(6),

Isolated yield.

Determined by chiral HPLC analysis.

Reactions were run on a 0.1 mmol scale.

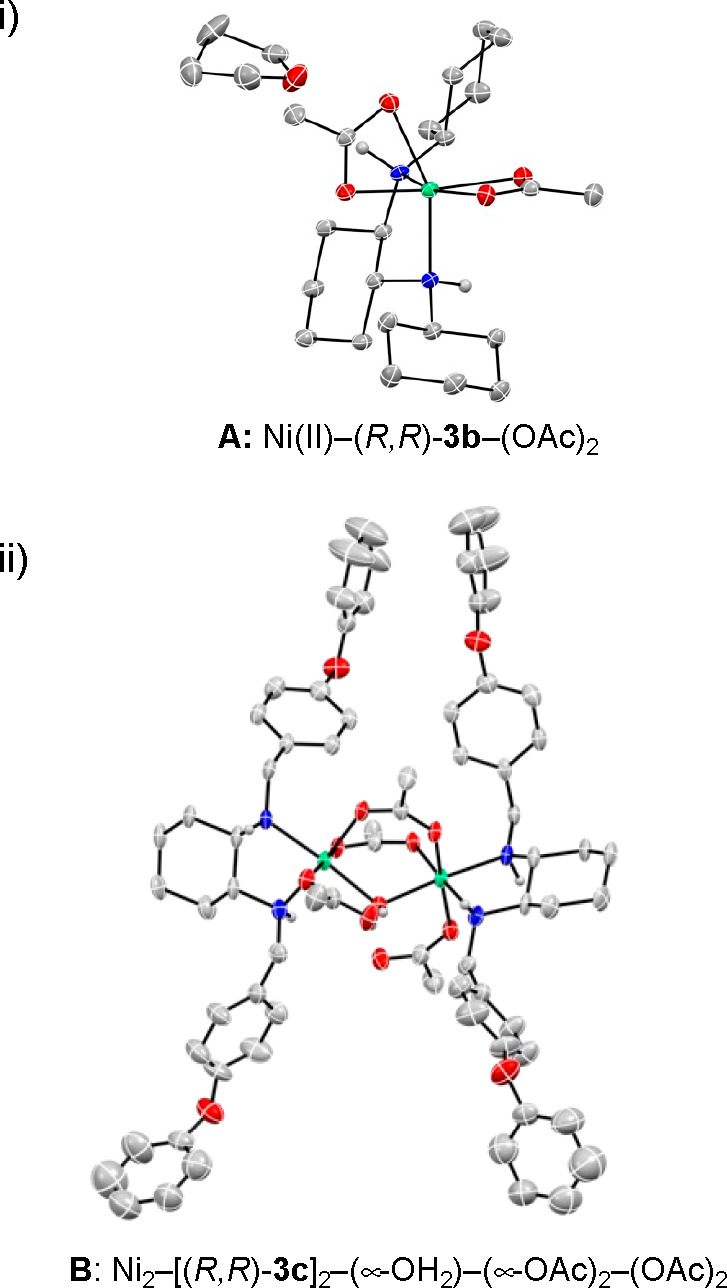

We previously reported that centrochiral Ni(II)–(R,R)-3b–(OAc)2A (CCDC 1482741) acts as a catalyst to promote the formal (3+2) cycloaddition of α-keto esters 5 with nitrones (Figure 1, i).7 However, we failed to grow diffractable crystals from Ni(OAc)2·H2O and (R,R)-3a (R = Bn). Instead, we successfully obtained a single crystal suitable for X-ray crystallographic analysis when (R,R)-3c (R = -CH2C6H4-4-OPh) was used as the ligand. The newly developed Ni(II) complex prepared from Ni(OAc)2·H2O and (R,R)-3c was found to be dinuclear Ni(II) complex B (CCDC 2212091), Ni2–[(R,R)-3c]2–(μ-OH2)–(μ-OAc)2–(OAc)2 (Figure 1, ii). The Cambridge Structural Database (CSD)44 contains several dinuclear complexes that involve three characteristic μ2 bridges (two acetates and a water molecule).45−48 However, to date, no chiral variants have been found among them, with only tetramethylethylenediamine (TMEDA) being used as a diamine ligand. On the contrary, our catalytic activity test with B under optimal conditions revealed that dinuclear Ni(II) complex B displayed results compatible with those of our in situ procedure with (R,R)-3a (R = Bn), affording (3R,4R)-6aa in 75% yield with >20/1 dr and 94% ee. Considering the potential lability of the bridging ligands in B, dinuclear complex B should be in equilibrium with the mononuclear complex, analogous to A, under the reaction conditions. Therefore, we examined the relationship between the ee of (R,R)-3c and that of Michael adduct 6aa under optimal conditions to gain insight into the nature of the potential heterochiral complex.48 The resulting linear relationship (Figure 2) indicated that the diastereomeric Ni species has an only weak effect on the enantioinduction of the Michael reaction.

Figure 1.

ORTEP drawings of (i) A [Ni(II)–(R,R)-3b–(OAc)2] and (ii) B {Ni2–[(R,R)-3c]2–(μ-OH2)–(μ-OAc)2–(OAc)2} (50% probability ellipsoids; hydrogen atoms on the carbons in A and B and the minor disorder components have been omitted for the sake of clarity).

Figure 2.

Relationship between the percent enantiomeric excess (ee) values of ligand 3c and Michael adduct 6aa. Details are listed in Table S1.

Computational Investigations

The mechanistic complexity in the catalytic system, in which multiple pathways are involved, inspired us to assess which TS model (our TS model vs the Evans TS model) is preferable. In this study, we modeled the catalytic asymmetric Michael reaction with α-keto ester 5b (R1 = Me) and β-nitrostyrene (1a) with the simplified ligand (R,R)-3d (R = Me) using Gaussian 16.49 The effect of the structural truncations in 3 and 5 was shown to have minimal effect in our previous work, which well reproduced both the reactive and stereochemical outcomes in the two different classes of (3+2) cycloaddition reactions of nitrones with keto ester 5b.8,9 To systematically consider the coordination isomerism in the octahedral Ni(II) complex, we classified the possible pathways on the basis of the coordination pattern of the α-keto ester enolates with Ni(II) (Figure 3). According to our earlier entries,8,9 the ester carbonyl in the α-keto ester was placed at the apical position in mode A and at the equatorial position in mode B (Figure 3, i). In this metal/ligand bifunctional mechanism of our proposed model,8,91a approaches from the Re face of the α-keto ester enolate through H-bonding interaction with the proximal N–H group on the ligand in mode A while the reaction occurs at the Si face of the enolate in mode B. On the basis of the Evans model originally reported with a malonate, we substituted the nucleophilic component for an α-keto ester enolate (Figure 3, ii). In the modified Evans model with an α-keto ester, the corresponding enolate coordinates to the Ni(II) center in the same plane as the diamine and 1a interacts with the Ni(II) center to form the saturated octahedral Ni(II) complex.11−13

Figure 3.

Schematic illustration of the Ni(II)–enolates generated from an α-keto ester. (i) Our model, in which the enolate coordinates to the Ni(II) center at the apical–equatorial positions. (ii) Modified Evans model, in which the enolate occupies the same plane as that of the diamine ligand.

In this research, we evaluated the deprotonation of 5b (INT-Is, TS-I, INT-IIs, and INT-IIIs) and the C–C bond-forming reaction (INT-IVs, TS-IIs, and INT-Vs) at the UM06L/6-311g+(d,p)/(CPCM: 2-propanol) (Ni: SDD)//UωB97XD/def2-SVPP (Ni: LanL2DZ) level of theory (Figure 4).50−52 As we previously reported,7 the chirality at metal37,38,40−42 in A is configurationally stable even in the solution. Furthermore, when we modeled the energy difference between the Ni(II)–(R,R)-3d–(OAc)2 complex and the corresponding dinuclear Ni complex {Ni2–[(R,R)-3d]2–(μ-OH2)–(μ-OAc)2–(OAc)2} on the basis of the crystal structures of A and B, the mononuclear Ni complex was calculated to be lower in energy than the dinuclear form (see Table S2). Thus, we used the energy level of the Ni(II)–(R,R)-3d–(OAc)2 complex as the reference point in this study. The reactions were initiated by the binding of α-keto ester 5b to the Ni(II)–(R,R)-3d–(OAc)2 complex. The soft enolization mechanism10 indeed works well in both our pathway and the Evans pathways. The barriers for the deprotonation (TS-Is) were calculated to be in the range of 19.0–21.5 kcal/mol (TS-I-A-Z, 19.0 kcal/mol; TS-I-B-Z, 20.5 kcal/mol; TSE-I-A-Z, 21.0 kcal/mol; TSE-I-B-Z, 21.5 kcal/mol). Subsequent dissociation of the resulting acetate from the INT-IIs leads to the formation of the Ni(II)–enolates (INT-IIIs).

Figure 4.

Computed energy profiles in the Michael reaction with α-keto ester 5b. Pathways for accessing (i) our TS model and (ii) the Evans TS model. Pathways for forming the E-enolate are not shown for the sake of clarity. Energy barriers for deprotonation (22.7–25.9 kcal/mol) and 1,4-addition (18.5–30.3 kcal/mol) are higher than those in the pathways to form the Z-enolate (see Tables S3 and S5). We labeled the computed structures (INTs and TSs) in the order of their numbering, coordination mode, geometry of the enolate, and descriptors of the prochiral face to systematically link the computed structures with the products. The descriptors Re (pro-R) and Si (pro-S) are given in the order of the carbon numbering of the product [e.g., TS-A-Z-ReRe and TS-B-Z-SiSi to reach (3R,4R)-6ab and (3S,4S)-6ab, respectively].

We next systematically assessed the C–C bond formation process (INT-IVs, TS-IIs, and INT-Vs) considering the possible patterns of coordination of 1a with the Ni(II)–enolates. Among the possible TSs, the lowest-energy TS in the C–C bond formation process is TS-II-A-Z-ReRe (14.7 kcal/mol), which leads to the formation of (R,R)-6ab (Figure 4, i, left). The second lowest-energy TS is TS-II-B-Z-SiSi (16.2 kcal/mol) to form (S,S)-6ab (Figure 4, i, right). In good agreement with our experimental results, the energetic barriers to form diastereomers (R,S)-7ab and (S,R)-7ab are large. Consequently, only trace amounts of 7 were experimentally detected in all of the substrate combinations that we examined.6

On the contrary, in the Evans pathways (Figure 4, ii), the energy balance between TSE-I and TSE-II was switched depending on the coordination mode. Similar to our pathways, in the most favorable pathway, the energy of TSE-I-B (21.5 kcal/mol) is higher than that of TSE-II-B-Z-SiSi (17.7 kcal/mol). In contrast, the energies of the TSE-Is are lower than those of the TSE-IIs (TSE-II-A-Z-ReRe, 24.0 kcal/mol; TSE-II-A-Z-ReSi, 22.4 kcal/mol; TSE-II-B-Z-SiRe, 28.6 kcal/mol). More importantly, all possible TSs in the Evans pathways have energies higher than that of the proposed C–C bond-forming TS (TS-II-A-Z-ReRe, 14.7 kcal/mol), in which the enolate coordinates to the Ni(II) center at the apical–equatorial positions relative to the diamine ligand.

Taken together, the detailed survey of the potential pathways points to a preference for our proposed C–C bond-forming TS, which merges enolate formation and H-bonding activation, accounting well for the observed stereoselectivity in the Michael reaction of β-nitrostyrene (1a) with α-keto ester 5a. Thus, we provided support for the stereochemical model, originally proposed for (3+2) cycloaddition,7−9 that can be expanded to the Michael reaction of β-nitrostyrene (1a) with α-keto ester 5a.

To gain further insight into the physical factors leading to the observed reactivity and selectivity trends, the transition structures in our proposed pathways were further characterized (Figure 5). The energy of the turnover- and enantio-determining TS in mode A is lower (TS-I-A-Z, 19.0 kcal/mol) than those in mode B (Figure 5, i and ii). As stated previously,8,9 the plausible steric repulsion observed between the tert-butyl group in 5b and an acetate (Brønsted base) may destabilize the energy of TS-I-B-Z (Figure 5, ii). In the TS-IIs, the N–H group in (R,R)-3b close to the nitro group in 1a should play a key role in controlling the reaction face in 1a (Figure 5, iii–vi).53 In the lowest-energy C–C bonding TS (TS-II-A-Z-ReRe), the N–H group is neighboring two oxygens of the nitro group in 1a [NH···Onitro(1), 2.07 Å; ∠NHOnitro(1), 149°; NH···Onitro(2), 2.25 Å; ∠NHOnitro(2), 144°] (Figure 5, iii). The asynchronicity in the H-bonding interaction between the N–H group and nitro group in 1a increases in the second-lowest-energy bonding TS (TS-II-B-Z-SiSi) [NH···Onitro(1), 1.99 Å; ∠NHOnitro(1), 161°; NH···Onitro(2), 2.40 Å; ∠NHOnitro(2), 128°] (Figure 5, iv). Thus, two-point donation of the nitro group lone pairs to the N–H group evidently plays a key role in organizing the transition structure in TS-II-A-Z-ReRe. In the other unfavorable TS-IIs (Figure 5, v and vi), the N–H group only coordinates to one oxygen in the nitro group in 1a, and the H···O distances were calculated to be shorter [TS-II-A-Z-ReSi, NH···Onitro, 1.89 Å; ∠NHOnitro(1), 159°; TS-II-B-Z-SiRe, NH···Onitro, 1.86 Å; ∠NHOnitro(1), 158°] than those of the corresponding lowest- and second-lowest-energy TSs.

Figure 5.

Computed transition structures of (i) TS-I-A-Z, (ii) TS-I-B-Z, (iii) TS-II-A-Z-ReRe, (iv) TS-II-B-Z-SiSi, (v) TS-II-A-Z-ReSi, and (vi) TS-II-B-Z-SiRe. The structures of TS-I-A-Z and TS-I-B-Z are illustrated using the original coordinates reported in ref (8). The single-point calculations were newly performed at the UM06L/6-311g+(d,p)/(CPCM: 2-propanol) (Ni: SDD)//UωB97XD/def2-SVPP (Ni: LanL2DZ) level of theory. Except for the protons that participate in enolate formation, all of the C–H hydrogen atoms have been omitted for the sake of clarity. Selected bond lengths and angles are given in angstroms and degrees, respectively.

We next performed natural bond orbital (NBO) analysis54 to quantify the n → σ* interactions between a lone pair orbital (n) and the antibonding orbital of an N–H bond (σ*) in each TS-II (Table 1). We confirmed that the orbitals of each lone pair in both Onitro(1) and Onitro(2) overlap with the N–H antibonding lone pair orbitals, showing that the H-bonding interactions indeed display bidentate coordination in TS-II-A-Z-ReRe and TS-II-B-Z-SiSi. Additionally, we identified that the Onitro(1) group in TS-II-A-Z-ReRe and TS-II-B-Z-SiSi possesses anionic character. The anionic Onitro(1) group interacts with the N–H group more strongly than the Onitro(2) group in TS-II-A-Z-ReRe, while in TS-II-B-Z-SiSi, the lone pair on the Onitro(2) group binds more tightly to the N–H group. However, the computed total strengths of the n → σ* interactions (TS-II-A-Z-ReRe, 7.2 kcal/mol; TS-II-B-Z-SiSi, 6.6 kcal/mol; TS-II-A-Z-ReSi, 6.6 kcal/mol; TS-II-B-Z-SiRe, 8.4 kcal/mol) are not correlated to each ΔG⧧ value. These results suggest that the n → σ* interactions in TS-II-A-Z-ReRe are not the primary factor that stabilizes the energy but rather play a more orientational role to weaken the unfavorable steric repulsion. For example, in the other TS-IIs (Figure 5, iv–vi), the nitro group in 1a is located near the tert-butyl group in 5b. In contrast, the nitro group in 1a is reasonably oriented away from the tert-butyl group in 5b in TS-II-A-Z-ReRe (Figure 5, iii).

Table 1. Computed Strengths of the H-Bonding Interaction (kilocalories per mole) for the TS-IIs in the Reaction of 1a with 5ba.

| n → σ*N–H | A-Z-ReRe | B-Z-SiSi | A-Z-ReSi | B-Z-SiRe | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| α spin | Onitro(1) | LP(1) | 1.74 | 0.25 | 3.32 | 3.63 |

| LP(2) | 0.26 | 0.10 | 0.59 | |||

| LP(3), anion | 0.54 | 0.11 | ||||

| Onitro(2) | LP(1) | 0.20 | 0.92 | |||

| LP(2) | 0.85 | 1.97 | ||||

| β spin | Onitro(1) | LP(1) | 1.73 | 0.11 | 3.30 | 3.61 |

| LP(2) | 0.26 | 0.25 | 0.59 | |||

| LP(3), anion | 0.54 | |||||

| Onitro(2) | LP(1) | 0.20 | 0.92 | |||

| LP(2) | 0.86 | 1.96 | ||||

| total | 7.2 | 6.6 | 6.6 | 8.4 | ||

NBO analysis for the TS-IIs was performed at the UM06L/6-311+g(d,p)/(CPCM: 2-propanol) (Ni: SDD)//UωB97XD/def2-SVPP (Ni: LanL2DZ) level of theory. Energies of <0.01 kcal/mol are not listed. LP = lone electron pair.

There are two mechanistic scenarios that potentially explain why our pathway involving N–H activation instead of Ni activation (for the TSs in the Evans model, see Figure S15) is preferable in the reaction of an α-keto ester (5b). First, the relative energy of INT-III (Ni–enolate) or INT-IV [Ni–enolate with β-nitrostyrene (1a)] may influence that of the corresponding C–C bond-forming TS (TS-II) regardless of the electrophile activation mode. In our computational analysis, TS-II-A-Z-ReRe (14.7 kcal/mol) and TSE-II-B-Z-SiSi (17.7 kcal/mol) were identified as the lowest-energy C–C bond-forming TS in our pathway and the Evans pathway, respectively. However, the ΔΔG values (ΔGTS-II – ΔGINT-IV) in our pathway and the Evans pathway are comparable (6.2 and 5.9 kcal/mol, respectively). These results suggest that the N–H···O interactions [total value of E(2) in TS-II-A-Z-ReRe of 7.2 kcal/mol] control both reactivity and selectivity through the stabilization of the TS, with a similar impact on the Ni···O interaction if the energetic penalty of the unfavorable steric repulsion is small. Alternatively, the C–C bond-forming TS (TS-II-A-Z-ReRe, 14.7 kcal/mol) is energetically more stable than the corresponding deprotonating TS (TS-I-A-Z, 19.0 kcal/mol) in the most favorable pathway (highlighted in maroon in Figure 4 and Table S3). Once the deprotonation of the α-keto ester occurs via TS-I-A-Z (19.0 kcal/mol), C–C bond formation preferentially takes place via the energetically lower TS-II-A-Z-ReRe (14.7 kcal/mol) without competing with other modes that involve Ni/N–H activation. We reported a similar energetic trend [TS-I (deprotonation) > TS-II (C–C bond formation)] in the Ni-catalyzed (3+2) cycloaddition of an α-keto ester with a C-CN nitrone.8

A similar computational analysis was performed with dimethylmalonate (2a) and Ni(II)–(R,R)-3d–(OAc)2 (Figure 6). The presence of a symmetry axis in the chiral ligand and substrate(s) is often beneficial for reducing the number of possible diastereomeric TSs.55,56 In the case of the reaction of 2a, the isomerism issues, coordination isomerism of the octahedral Ni(II) complex (mode A vs mode B) and E/Z isomerism of the enolate, considered in the reaction with α-keto ester 5b could be eliminated. More importantly, the computational analysis of the reaction with 2a provides several points of mechanistic contrasts with 5b, which improves our understanding of the unique substrate-dependent enantio-switching in the Ni(II)-catalyzed Michael reaction. As shown in the overall potential energy surface (Figure 6), we found that the Evans C–C bond-forming TS (TSE-ii-Si, 18.3 kcal/mol) is the lowest-energy TS in the Michael reaction (Figure 6, ii) with dimethyl malonate (2a). This conclusion is consistent with that previously reported by Shiryaev et al.,13 although their group computed only the Evans TS of acetylacetonate with the Ni complex prepared from NiCl2 and N,N-dimethyl-2,3-butanediamine. In contrast, our computational analysis suggests that deprotonation readily occurs with a relatively small barrier (TSE-i, 13.1 kcal/mol), and thus, the TSE-ii-Si is both the turnover- and enantio-determining step in the favorable pathway (Figure 6, ii, green). In addition, our computational analysis suggests that the Evans TS and our TS could be potentially competitive upon alternation of the substrate or conditions, considering that the energy gap between TSE-ii-Si (Evans TS) and TS-ii-Si (our TS) is not so large (ΔΔG⧧ = 0.7 kcal/mol). Importantly, both the Evans pathway and our pathway preferentially afford (S)-4aa, which is in good agreement with the experimental results.

Figure 6.

Computed energy profiles in the Michael reaction with dimethyl malonate (2a). Pathways to access (i) our TS model and (ii) the Evans TS model.

As shown in the transition structures (Figure 7), H-bonding interactions are present in each TS. In the lowest-energy TS (Figure 7, iv), one oxygen [Onitro(1)] in the nitro group of 1a binds to the Ni(II) center, while the other [Onitro(2)] interacts with the N–H group in (R,R)-3d. Because of H-bonding interaction, the methyl group in TSE-ii-Si is optimally oriented away from 1a to avoid unfavorable steric interactions. In the other TSs, the plausible steric repulsion associated with the substituent in the ester group in 2a destabilizes the energies. For example, in the second-lowest-energy TS (Figure 7, ii, TS-ii-Si), a methyl ester in 2a is oriented in the same direction as the Ph group in 1a. In the third-lowest-energy TS (Figure 7, i, TS-ii-Re), which affords the observed minor enantiomer (R)-4aa, a methyl ester in 2a was positioned close to the nitro group. The experimental observation that the ee value of the product with diisopropyl malonate (2b) is much higher than that with dimethyl malonate (2a) is consistent with this idea.

Figure 7.

Computed transition structures of (i) TS-ii-Re, (ii) TS-ii-Si, (iii) TSE-ii-Re, and (iv) TSE-ii-Si. The C–H hydrogen atoms have been removed for the sake of clarity. Selected bond lengths and angles are given in angstroms and degrees, respectively.

Subsequent NBO analysis54 of the reaction of 1a with 2a revealed unique trends in the n → σ* interactions (Table 2). First, the n → σ* interactions in TS-ii (TS-ii-Re, 17.1 kcal/mol; TS-ii-Si, 13.6 kcal/mol) are significantly stronger than those in TS-II (Table 1; A-Z-ReRe, 7.2 kcal/mol; B-Z-SiSi, 6.6 kcal/mol; A-Z-ReSi, 6.6 kcal/mol; B-Z-SiRe, 8.4 kcal/mol). The results suggest that the strength of the n → σ* interactions for activating β-nitrostyrene (1a) varies depending on the nucleophile. Second, in TSE-ii, the strength of the n → σ* interactions between Onitro(1) and N–H decreased drastically (TSE-ii-Re, 0.69 kcal/mol; TSE-ii-Si, <0.01 kcal/mol) owing to the interaction between Ni(II) and Onitro(1). In the lowest-energy TS (TSE-ii-Si), Onitro(2) independently binds to the N–H group (4.1 kcal/mol). Although the total contribution of H-bonding interactions in TS-ii-Re (our model) was calculated to be the largest, TSE-ii-Si (Evans TS model) is slightly lower in energy than TS-ii-Si (our TS model). These results suggest that the attraction–repulsion balance is critical to decreasing the energy of the TS. In the reaction of 1a with 2a, two-point binding with Ni(II) and N–H in TSE-ii-Si cooperatively fixes two reactants, so that C–C bond formation takes place at the Si face in 1a.

Table 2. Computed Strengths of the H-Bonding Interaction (kilocalories per mole) for the TS-IIs in the Reaction of 1a with 2aa.

| n → σ*N–H | TS-II-Re | TS-II-Si | TSE-II-Re | TSE-II-Si | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| α spin | Onitro(1) | LP(1) | 3.66 | 3.55 | 0.10 | |

| LP(2) | 2.53 | 2.03 | 0.25 | |||

| LP(3), anion | 2.37 | 1.24 | ||||

| Onitro(2) | LP(1) | 0.47 | ||||

| LP(2) | 0.03 | 1.56 | ||||

| β spin | Onitro(1) | LP(1) | 3.63 | 3.54 | 0.14 | |

| LP(2) | 2.52 | 2.01 | 0.20 | |||

| LP(3), anion | 2.36 | 1.24 | ||||

| Onitro(2) | LP(1) | 0.47 | ||||

| LP(2) | 0.03 | 1.59 | ||||

| total | 17.1 | 13.6 | 0.69 | 4.1 | ||

NBO analysis was performed for TS-iis at the UM06L/6-311+g(d,p)/(CPCM: 2-propanol) (Ni: SDD)//UωB97XD/def2-SVPP (Ni: LanL2DZ) level of theory. Energies of <0.01 kcal/mol are not listed. LP = lone electron pair.

Conclusion

Herein, we present our results to clarify the mechanism of β-nitrostyrene facial selectivity switching in Ni–diamine–(OAc)2-catalyzed asymmetric reactions. In the reaction with a dimethyl malonate, the Evans TS, wherein the enolate binds in the same plane as that of the diamine ligand, is identified as the lowest-energy TS to promote C–C bond formation from the Si face in β-nitrostyrene. On the contrary, the reaction with an α-keto ester occurs from the Re face in 1a, in which the enolate coordinates to the Ni(II) center at the apical–equatorial positions relative to the diamine ligand. In both pathways, the N–H group in the ligand plays a key orientational role in constructing a well-defined three-dimensional architecture, which may minimize unfavorable steric repulsion. Although our computational analysis adequately reproduced the experimental results, this work is still in the proof-of-concept stage using relatively simple β-nitrostyrene, α-keto ester, and malonate as a model system. Further studies are certainly needed to assess the generality of the proposed mechanism using other substrates. We hope that this work will serve as a starting point that will eventually lead to the ultimate goal of rational catalyst design with the merger of coordination isomerism and H-bonding activation. Applications of the developed Ni catalysis to explore biologically active molecules are also being extensively studied in our group.

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this study are available in the published article and its online Supporting Information.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.joc.2c02732.

Experimental details, spectroscopic data, DFT calculations, NMR spectra, HPLC charts, and Cartesian coordinates (PDF)

Author Present Address

⊥ S.K.: Graduate School and School of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Osaka University, Osaka 565-0871, Japan

Author Present Address

# A.N.: Kyorin Pharmaceutical, Co., Ltd., Tokyo 101-8311, Japan.

Author Present Address

@ Y.H.: School of Pharmaceutical Sciences, University of Shizuoka, Shizuoka 422-8526, Japan.

Author Present Address

∇ M.U.: The University of Tokyo, Bunkyo-ku, Tokyo 113-0033, Japan.

The work was partially supported by project funding from RIKEN, Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (B) 22H02214 (Y.S.) and Grant-in-Aid for Transformative Research Areas (B) 22H05019 (Y.S.). RIKEN Hokusai GreatWave (GW) and Big Waterfall (BW) provided the computer resources for the DFT calculations.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Dedication

This work is dedicated to the memory of Professor David A. Evans.

Supplementary Material

References

- Pellissier H. Recent Developments in Enantioselec-tive Nickel(II)-Catalyzed Conjugate Additions. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2015, 357, 2745–2780. 10.1002/adsc.201500512. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lectard S.; Hamashima Y.; Sodeoka M. Recent Advances in Catalytic Enantioselective Fluorination Reactions. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2010, 352, 2708–2732. 10.1002/adsc.201000624. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sohtome Y.; Sodeoka M. Multiselective Catalytic Asymmetric Reactions Using α-Keto Esters as Pronucleophiles. Synlett 2020, 31, 523–534. 10.1055/s-0039-1690722. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki T.; Hamashima Y.; Sodeoka M. Asymmetric Fluorination of α-Aryl Acetic Acid Derivatives with the Catalytic System NiCl-Binap/RSiOTf/2,6-Lutidine. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2007, 46, 5435–5439. 10.1002/anie.200701071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamashima Y.; Nagi T.; Shimizu R.; Tsuchimoto T.; Sodeoka M. Catalytic Asymmetric α-Chlorination of 3-Acyloxazolidin-2-One with a Trinary Catalytic System. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2011, 2011, 3675–3678. 10.1002/ejoc.201100453. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura A.; Lectard S.; Hashizume D.; Hamashima Y.; Sodeoka M. Diastereo- and Enantioselective Conjugate Addition of α-Ketoesters to Nitroalkenes Catalyzed by a Chiral Ni(OAc)2 Complex under Mild Conditions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 4036–4037. 10.1021/ja909457b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sohtome Y.; Nakamura G.; Muranaka A.; Hashizume D.; Lectard S.; Tsuchimoto T.; Uchiyama M.; Sodeoka M. Naked d-Orbital in a Centrochiral Ni(II) Complex as a Catalyst for Asymmetric [3+2] Cycloaddition. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 14875. 10.1038/ncomms14875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ezawa T.; Sohtome Y.; Hashizume D.; Adachi M.; Akakabe M.; Koshino H.; Sodeoka M. Dynamics in Catalytic Asymmetric Diastereoconvergent (3 + 2) Cycloadditions with Isomerizable Nitrones and α-Keto Ester Enolates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 9094–9104. 10.1021/jacs.1c02833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sohtome Y.; Sodeoka M. Theoretical Insights into the Substrate-Dependent Diastereodivergence in (3 + 2) Cycloaddition of α-Keto Ester Enolates with Nitrones. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2022, 70, 616–623. 10.1248/cpb.c22-00041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carreira E. M.; Kvaerno L.. Classics in Stereoselective Synthesis; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2009; pp 69–102. [Google Scholar]

- Evans D. A.; Seidel D. Ni(II)-Bis[(R,R)-N,N′-Dibenzylcyclohexane-1,2-Diamine]Br2 Catalyzed Enantioselec-tive Michael Additions of 1,3-Dicarbonyl Compounds to Conjugated Nitroalkenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 9958–9959. 10.1021/ja052935r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans D. A.; Mito S.; Seidel D. Scope and Mechanism of Enantioselective Michael Additions of 1,3-Dicarbonyl Com-pounds to Nitroalkenes Catalyzed by Nickel(II)-Diamine Complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 11583–11592. 10.1021/ja0735913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiryaev V. A.; Nikerov D. S.; Reznikov A. N.; Klimochkin Y. N. DFT Insight into Mechanism of the Ni(II)-Catalyzed Enantioselective Michael Addition: A Combined Computational and Experimental Study. Mol. Catal. 2021, 505, 111463. 10.1016/j.mcat.2021.111463. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Afanasyev O. I.; Kliuev F. S.; Tsygankov A. A.; Nelyubina Y. V.; Gutsul E.; Novikov V. V.; Chusov D. Fluoride Additive as a Simple Tool to Qualitatively Improve Performance of Nickel-Catalyzed Asymmetric Michael Addition of Malonates to Nitroolefins. J. Org. Chem. 2022, 87, 12182–12195. 10.1021/acs.joc.2c01339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao B.; Han Z.; Ding K. The NH Functional Group in Organometallic Catalysis. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 4744–4788. 10.1002/anie.201204921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dub P. A.; Gordon J. C. Metal-Ligand Bifunctional Catalysis: The “Accepted” Mechanism, the Issue of Concertedness, and the Function of the Ligand in Catalytic Cycles Involving Hydrogen Atoms. ACS Catal. 2017, 7, 6635–6655. 10.1021/acscatal.7b01791. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fanourakis A.; Docherty P. J.; Chuentragool P.; Phipps R. J. Recent Developments in Enantioselective Transition Metal Catalysis Featuring Attractive Noncovalent Interactions between Ligand and Substrate. ACS Catal. 2020, 10, 10672–10714. 10.1021/acscatal.0c02957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibasaki M.; Kanai M.; Matsunaga S.; Kumagai N. Recent Progress in Asymmetric Bifunctional Catalysis Using Multimetallic Systems. Acc. Chem. Res. 2009, 42, 1117–1127. 10.1021/ar9000108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumagai N.; Kanai M.; Sasai H. A Career in Catalysis: Masakatsu Shibasaki. ACS Catal. 2016, 6, 4699–4709. 10.1021/acscatal.6b01227. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sperger T.; Sanhueza I. A.; Kalvet I.; Schoenebeck F. Computational Studies of Synthetically Relevant Homogeneous Organometallic Catalysis Involving Ni, Pd, Ir, and Rh: An Overview of Commonly Employed DFT Methods and Mechanistic Insights. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 9532–9586. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sperger T.; Sanhueza I. A.; Schoenebeck F. Computation and Experiment: A Powerful Combination to Understand and Predict Reactivities. Acc. Chem. Res. 2016, 49, 1311–1319. 10.1021/acs.accounts.6b00068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner J. P.; Schreiner P. R. London Dispersion in Molecular Chemistry-Reconsidering Steric Effects. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 12274–12296. 10.1002/anie.201503476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liptrot D. J.; Power P. P. London Dispersion Forces in Sterically Crowded Inorganic and Organometallic Molecules. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2017, 1, 0004. 10.1038/s41570-016-0004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tasker S. Z.; Standley E. A.; Jamison T. F. Recent Advances in Homogeneous Nickel Catalysis. Nature 2014, 509, 299–309. 10.1038/nature13274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ananikov V. P. Nickel: The “Spirited Horse” of Transition Metal Catalysis. ACS Catal. 2015, 5, 1964–1971. 10.1021/acscatal.5b00072. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Diccianni J.; Lin Q.; Diao T. Mechanisms of Nickel-Catalyzed Coupling Reactions and Applications in Alkene Functionalization. Acc. Chem. Res. 2020, 53, 906–919. 10.1021/acs.accounts.0c00032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsygankov A. A.; Chusov D. Straightforward Access to High-Performance Organometallic Catalysts by Fluoride Activation: Proof of Principle on Asymmetric Cyanation, Asymmetric Michael Addition, CO2 Addition to Epoxide, and Reductive Alkylation of Amines by Tetrahydrofuran. ACS Catal. 2021, 11, 13077–13084. 10.1021/acscatal.1c03785. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bartlett S. L.; Johnson J. S. Synthesis of Complex Glycolates by Enantioconvergent Addition Reactions. Acc. Chem. Res. 2017, 50, 2284–2296. 10.1021/acs.accounts.7b00263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beletskaya I. P.; Nájera C.; Yus M. Stereodivergent Catalysis. Chem. Rev. 2018, 118, 5080–5200. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krautwald S.; Carreira E. M. Stereodivergence in Asymmetric Catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 5627–5639. 10.1021/jacs.6b13340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H. Y.; Oh K. Stereodivergent Asymmetric Reactions Catalyzed by Brucine Diol. Synlett 2015, 26, 2067–2087. 10.1055/s-0034-1380862. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lin L.; Feng X. Catalytic Strategies for Diastereodivergent Synthesis. Chem. - Eur. J. 2017, 23, 6464–6482. 10.1002/chem.201604617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng K.; Liu X.; Feng X. Recent Advances in Metal-Catalyzed Asymmetric 1,4-Conjugate Addition (ACA) of Nonorganometallic Nucleophiles. Chem. Rev. 2018, 118, 7586–7656. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis K. G.; Ghosh S. K.; Bhuvanesh N.; Gladysz J. A. Cobalt(III) Werner Complexes with 1,2-Diphenylethylenediamine Ligands: Readily Available, Inexpensive, and Modular Chiral Hydrogen Bond Donor Catalysts for Enantioselective Organic Synthesis. ACS Cent. Sci. 2015, 1, 50–56. 10.1021/acscentsci.5b00035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh S. K.; Ganzmann C.; Bhuvanesh N.; Gladysz J. A. Werner Complexes with ω-Dimethylaminoalkyl Substituted Ethylenediamine Ligands: Bifunctional Hydrogen-Bond-Donor Catalysts for Highly Enantioselective Michael Additions. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 4356–4360. 10.1002/anie.201511314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganzmann C.; Gladysz J. A. Phase Transfer of Enantiopure Werner Cations into Organic Solvents: An Overlooked Family of Chiral Hydrogen Bond Donors for Enantioselective Catalysis. Chem. - Eur. J. 2008, 14, 5397–5400. 10.1002/chem.200800226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wegener A. R.; Kabes C. Q.; Gladysz J. A. Launching Werner Complexes into the Modern Era of Catalytic Enantioselective Organic Synthesis. Acc. Chem. Res. 2020, 53, 2299–2313. and references cited therein 10.1021/acs.accounts.0c00410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L.; Meggers E. Stereogenic-Only-at-Metal Asymmetric Catalysts. Chem. - Asian J. 2017, 12, 2335–2342. and references cited therein 10.1002/asia.201700739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamakawa M.; Ito H.; Noyori R. The Metal-Ligand Bifunctional Catalysis: A Theoretical Study on the Ruthenium(II)-Catalyzed Hydrogen Transfer between Alcohols and Carbonyl Compounds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000, 122, 1466–1478. 10.1021/ja991638h. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Abell J. P.; Yamamoto H. Development and Applications of Tethered Bis(8-Quinolinolato) Metal Complexes (TBOxM). Chem. Soc. Rev. 2010, 39, 61–69. 10.1039/B907303P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehnbom A.; Ghosh S. K.; Lewis K. G.; Gladysz J. A. Octahedral Werner Complexes with Substituted Ethylenediamine Ligands: A Stereochemical Primer for a Historic Series of Compounds Now Emerging as a Modern Family of Catalysts. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2016, 45, 6799–6811. 10.1039/C6CS00604C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L.; Meggers E. Steering Asymmetric Lewis Acid Catalysis Exclusively with Octahedral Metal-Centered Chirality. Acc. Chem. Res. 2017, 50, 320–330. 10.1021/acs.accounts.6b00586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes D. M.; Ji J.; Fickes M. G.; Fitzgerald M. A.; King S. A.; Morton H. E.; Plagge F. A.; Preskill M.; Wagaw S. H.; Wittenberger S. J.; Zhang J. Development of a Catalytic Enantioselective Conjugate Addition of 1,3-Dicarbonyl Compounds to Nitroalkenes for the Synthesis of Endothelin-A Antagonist ABT-546. Scope, Mechanism, and Further Application to the Synthesis of the Antidepressant Rolipram. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002, 124, 13097–13105. 10.1021/ja026788y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groom C. R.; Bruno I. J.; Lightfoot M. P.; Ward S. C. The Cambridge Structural Database. Acta Crystallogr. B Struct Sci. Cryst. Eng. Mater. 2016, 72, 171–179. 10.1107/S2052520616003954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kühnert J.; Rüffer T.; Ecorchard P.; Bräuer B.; Lan Y.; Powell A. K.; Lang H. Reaction Chemistry of 1,1’-Ferrocene Dicarboxylate towards M(II) Salts (M = Co, Ni, Cu): Solid-State Structure and Electrochemical, Electronic and Magnetic Properties of Bi- and Tetrametallic Complexes and Coordination Polymers. Dalton Trans. 2009, 4499–4508. 10.1039/b821407g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margossian T.; Larmier K.; Kim S. M.; Krumeich F.; Fedorov A.; Chen P.; Müller C. R.; Copéret C. Molecularly Tailored Nickel Precursor and Support Yield a Stable Methane Dry Reforming Catalyst with Superior Metal Utilization. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 6919–6927. 10.1021/jacs.7b01625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kani I.; Unver H. Bimetallic Ni(II) Complex with Carboxylate Bridging for Homogeneous Hydrogenation of Alkenes with NaBH4. Polyhedron 2020, 187, 114649. 10.1016/j.poly.2020.114649. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Satyanarayana T.; Abraham S.; Kagan H. B. Nonlinear Effects in Asymmetric Catalysis. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 456–494. 10.1002/anie.200705241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaussian 16, rev. C.01; Gaussian, Inc.: Wallingford, CT, 2019. [Google Scholar]; See the Supporting Information for the full citation.

- Zhao Y.; Truhlar D. G. Density Functionals with Broad Applicability in Chemistry. Acc. Chem. Res. 2008, 41, 157–167. 10.1021/ar700111a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chai J.-D.; Head-Gordon M. Long-range Corrected Hybrid density Functionals with Damped Atom-atom Dispersion Corrections. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2008, 10, 6615–6620. 10.1039/b810189b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng J.; Xu X.; Truhlar D. G. Minimally Augmented Karlsruhe Basis sets. Theor. Chem. Acc. 2011, 128, 295–305. 10.1007/s00214-010-0846-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Allen F. H.; Baalham C. A.; Lommerse J. P. M.; Raithby P. R.; Sparr E. Hydrogen-Bond Acceptor Properties of Nitro-O Atoms: A Combined Crystallographic Database and Ab Initio Molecular Orbital Study. Acta Crystallogr. B 1997, 53, 1017–1024. 10.1107/S0108768197010239. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Glendening E. D.; Landis C. R.; Weinhold F. Natural Bond Orbital Methods. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev.: Comput. Mol. Sci. 2012, 2, 1–42. 10.1002/wcms.51. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Whitesell J. K. C2 Symmetry and Asymmetric Induction. Chem. Rev. 1989, 89, 1581–1590. 10.1021/cr00097a012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moberg C. Symmetry as a Tool for Solving Chemical Problems. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 2021, 94, 558–564. 10.1246/bcsj.20200338. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this study are available in the published article and its online Supporting Information.