Abstract

Background

African American (AA) adults are disproportionately affected by cardiovascular disease risk factors. Many nutrition interventions aim to promote healthier eating to reduce cardiovascular disease incidences among participants. However, little is known about what influences individuals’ nutrition self-efficacy while participating in these interventions.

Objective

The objective of this study is to explore the drivers and barriers of nutrition self-efficacy among Nutritious Eating With Soul (NEW Soul) participants. The NEW Soul study was funded from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

Design

A purposive-current study sampling was used to conduct 4 audio-recorded focus groups for this qualitative study. Bandura’s self-efficacy theory of behavior change guided the framework. This theory asserts that individual self-efficacy is influenced by 4 factors: (1) mastery experiences, (2) vicarious experiences, (3) social persuasion, and (4) somatic and emotional states.

Participants/setting

Inclusion criteria for the NEW Soul program included being an AA, being between 18 and 65 years old, and having a body mass index between 25 and 49.9. Participants in cohort 2 (n = 84) of the NEW Soul program were asked to participate in focus groups. In total, 28 individuals (16 vegan, 12 omnivorous participants) took part in 4 in-person focus groups, which contained 3 to 13 participants. Focus groups took place in the southeastern United States.

Main outcome measure

Perception of drivers and barriers of following the diet.

Statistical analysis

Responses were analyzed qualitatively using principles of content analysis.

Results

Nine themes influenced participants’ confidence in their ability to follow their diet: food preference, planning and preparation, identity and tradition, mindfulness, representation, social support, social influence, accountability, and state of mind.

Conclusion

In this study, self-efficacy played a prominent role in participants’ motivations toward following the diet. Mastery experiences, vicarious experiences, social persuasion, and positive psychological arousal were all common themes in participant-reported sources of motivation. Nutrition interventions are likely to elicit positive behavioral outcomes if these 4 factors that enhance self-efficacy are incorporated into program development.

Keywords: Nutrition self-efficacy, Qualitative research, Community engagement, Vegan diet, African American

Rates of Obesity are High Among African Americans (AAs) in the United States (49.6%), with AA women having the highest rate (56.9%) compared with any other racial group.1 Having obesity increases the risk of noncommunicable diseases, such as cardiovascular disease, cancer, and stroke, which are among the leading causes of death among AAs in the United States.2 Sedentary behavior and poor diet quality are some of the top individual-level contributors to obesity.3 States in the southern United States have one of the highest prevalence of obesity compared with other regions of the United States.4 Soul food cuisines are traditionally consumed by AAs in the southern United States. The term “soul food” was originated in the 1960s to represent AA cultural food practices.5 Soul food evolved from the US era where slave masters gave enslaved AAs foods that were both low in quality and nutrition value.6,7 To make use of the undesirable foods that they were given, enslaved AAs added ingredients like cornmeal, salt pork, and molasses, and they fried foods to enhance flavor and satiety.6–8 Given the increased energy expenditure enslaved AAs experienced due to rigorous labor, they needed to consume higher-calorie diets to replenish what was lost.8

Today, soul food is regularly consumed among AAs living in the south. However, AA adults are now less active overall; therefore, they are not expending as much energy as generations prior.9 This may pose some concerns because soul food is higher in saturated fats, processed meats, sodium, and sugar and lower in fruits and vegetables, fiber, and calcium compared with the US Dietary Guidelines recommendations.8 Recent research has found that the southern soul food diet may in part explain racial and regional disparities in diet quality among AAs compared with non-Hispanic White Americans.10,11

A prospective cohort study conducted over the span of 30 years saw that higher intake of unprocessed and processed meats (hot dogs, bacon, sausage, salami, bologna, etc), and total red meat consumption were associated with a higher risk of coronary heart disease,12 whereas the intake of plant-based proteins (1 serving a day), legumes, dairy products, and whole grains were associated with having a lower risk of cardiovascular disease.12 Furthermore, a meta-analysis found that every 5% increase in energy from animal protein consumed was associated with a 5% increase in cardiovascular disease mortality.13 Plant-based diets show promise of reducing these disparities by maximizing the consumption of nutrient-dense plant foods while reducing or eliminating the consumption of processed foods, oil, and meat products.14 Plant-based diets are protective against several chronic diseases, including diabetes,15 the incidence of total cancers,16 and overall mortality.17 Previous research has demonstrated that switching from a standard American diet to a more plant-based diet can confer health benefits. Research from the Adventist Health Study found that compared with AA omnivores, AA vegetarians and vegans had a significantly lower risk of hypertension, diabetes, and total and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol.18 However, there has been little research examining the psychosocial factors, such as dietary self-efficacy, that may play a role in adopting and sustaining a more healthful, plant-based version of a soul food diet among AAs living in the South. This relationship is important because understanding the level of self-efficacy and motivation of individuals, coupled with appropriate interventions, can help create sustainable lifestyle change among this group.19

Existing literature underscores the importance of culturally relevant interventions to improve dietary outcomes in AAs. In a study of AA adults in North Carolina, researchers found high self-efficacy and knowledge of healthy foods, but despite this self-efficacy, participants were not meeting dietary guidelines.20 The authors emphasize the importance of culturally tailored interventions for AAs, which may help improve dietary intake. Researchers conducted qualitative research with AA women to understand the barriers to healthy eating and physical activity.21 They similarly found that although the women were knowledgeable about the importance of eating healthy and staying active, some lacked the motivation to engage in physical activity and planning for healthy diets was a barrier to improving diet quality.21 Thus, identifying facilitators to follow healthy diets may help improve diet quality.

There is limited research on long-term clinical interventions with AAs adopting healthful, plant-based diets. Few studies also address the challenges that AA participants face while attempting to maintain a new lifestyle diet. The Nutritious Eating With Soul (NEW Soul) study (funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, R01HL135220) is one of the first long-term randomized controlled trials that includes both a vegan and a low-fat, meat-reduced condition with the aim of improving dietary intake while maintaining traditional AA culture food choices.22 To date, no qualitative research has been conducted with AAs regarding their successes or challenges faced while currently following a vegan or a low-fat, meat-reduced omnivorous (omni) soul food diet. Therefore, the primary objective of this study is to explore the drivers and barriers for following plant-based vegan or a low-fat, meat-reduced diet (omni) among NEW Soul participants. This article will also examine how participants’ attitudes and beliefs are related to their motivation to follow their diet.

METHODS

The NEW Soul study is delivered across 2 cohorts separated by 1 year (cohort 1: years 2018–2020 and cohort 2: years 2019–2021). The recruitment process for NEW Soul has been described in detail elsewhere.22 In short, researchers conducted extensive outreach to outlets like community events, radio advertisements, and social media platforms. Primary inclusion criteria were if individuals self-identified as AA, had a body mass index between 25 and 49.9, lived in or around the Columbia, South Carolina, area, and were able to attend classes. Primary exclusion criteria were individuals who were pregnant or planning to become pregnant during the study period, on medication for type 2 diabetes, concurrently participating in another weight loss program, and/or were already following a vegan diet.22

AA adults were randomized to a plant-based vegan diet (vegan) or a low-fat, meat-reduced omni diet. Participants randomized to the vegan diet were asked to exclude all animal products, whereas those in the omni group were asked to reduce animal product intake (eg, no more than 3 to 5 oz of meat per day, no more than 2 egg yolks per week).22 Both of the NEW Soul diets were based on the Oldways African Heritage Pyramid.23 This pyramid was designed for AAs and African descendants to bring together culture and healthy eating.23 Foods on this pyramid (fruits, vegetables, tubers, beans, nuts, rice, and herbs and spices) are represented from countries of Africa, the Americans, and the Caribbean.23

Participants attended weekly classes for the first 6 months of the study, biweekly classes for the following 6 months, and then 1 class a month for the final year of the study. Transitioning to fewer class meetings as time progressed was done to ease participants into dietary maintenance. The behavioral content and curriculum for the 2 groups were the same apart from the exclusion of animal products in the vegan. All classes were led by a staff consisting of 1 White registered dietitian nutritionist, 1 AA registered dietitian nutritionist, an AA program coordinator, and 2 AA community members. Each of the staff members conducted different parts of the class.

Focus Group Recruitment

In the present study, participants in cohort 2 (n = 84) were recruited to participate in the focus groups. The recruitment for the focus groups was done during regular NEW Soul class time. Moderators announced date and times of focus groups with instructions on how to sign up. Reminders about focus groups were sent out via e-mail and posted on the participant Facebook support groups. All participants in cohort 2 of NEW Soul were eligible to participate.

Researchers sought to have 8 to 10 participants in each of the 4 groups because this number is within the desired range for focus groups.24 There were 4 time slots allotted for the focus groups: 2 for the omni group and 2 for the vegan group. Participants were given the option of signing up for one of the focus groups that corresponded to their diet. All focus groups were organized by the NEW Soul study research team at a date and time convenient for participants (ie, come before or stay after their class to complete focus group).

Focus Group Guide Development

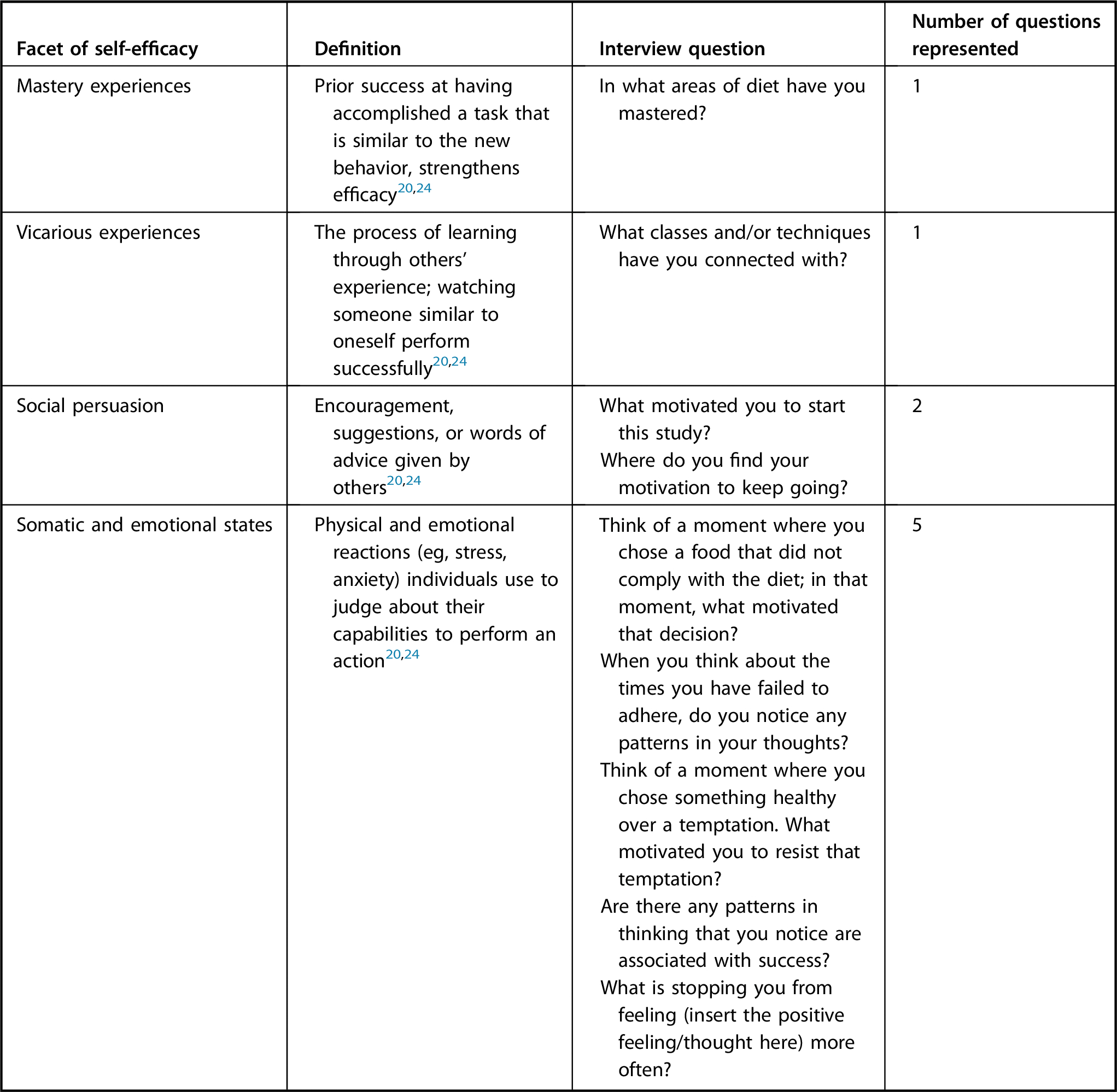

Albert Bandura’s theory of self-efficacy was used to develop the focus group guide. This theory states that self-efficacy is underscored by 4 core concepts: (1) mastery experiences, (2) vicarious experiences, (3) social persuasion, and (4) somatic and emotional states.25,26 Mastery experiences occur when one successfully completes a task, which then increases his or her confidence in the ability to complete the same task in the future. Vicarious experiences occur when one observes another person, with perceived similar attributes, successfully complete a task. Social persuasion occurs when one receives encouragement (or discouragement) pertaining to individual’s performance or ability to perform. Somatic and emotional (psychological) states refer to physical or emotional feelings one has when they imagine the likelihood of their success or failure in completing a task.25,26 See Figure 1 for a sample of the focus group guide questions.

Figure 1.

Focus group sample questions exploring the drivers and barriers of nutrition self-efficacy for African American participants following a plant-based vegan or a low-fat soul food diet.

Data Collection

A total of 28 participants took part in the 4 focus groups. Of the 28, 16 participants were represented from the vegan group and 12 participants were represented from the omni group. All focus groups took place in a private room across the hall from where participants attended their regular class. The focus groups were led by 2 trained moderators from the NEW Soul program. Notetakers were present at each session to capture nonverbal information. The focus group ranged from 50 to 65 minutes. All sessions were recorded with the permission of the participants and transcribed verbatim. Participation in the focus groups was voluntary and all participants provided oral and written consent. Participants received a $10 gift card for their participation. This study received institutional review board approval from the University of South Carolina.

Qualitative research methods were appropriate given that few studies have examined the experiences of AA participation in dietary interventions. The research team employed a phenomenological approach, which allows for an in-depth exploration of how and why participants change or do not change their health behaviors as they are experiencing the diet,24 which was central to the study’s objectives. Focus groups are an effective method of data collection, particularly with groups that have a shared experience, so that participants can react to other thoughts that they may not have disclosed in individual interviews.27 Therefore, focus groups were used to gain insight into participants’ attitudes, beliefs, and knowledge of following a vegan or a low-fat, meat-reduced omni diet while participating in the NEW Soul program.

Data Analysis

The transcripts were coded by 2 of the study authors, who were trained in qualitative research, using the qualitative data analysis software NVivo version 12.28 Emergent thematic coding techniques were used to examine the data given the exploratory nature of the study.29 The qualitative research process described by Tolley used 5 steps: reading, coding, displaying, reducing, and interpreting.30 We coded the first set of data separately to find emergent themes. We then collaborated to assess congruency in codes; any discrepancies were resolved in subsequent coding meetings. Then, we combined our emergent themes and cross-coded the second set of data. Once all codes were completed, we categorized our codes into broader concepts to formulate our themes and subthemes.

RESULTS

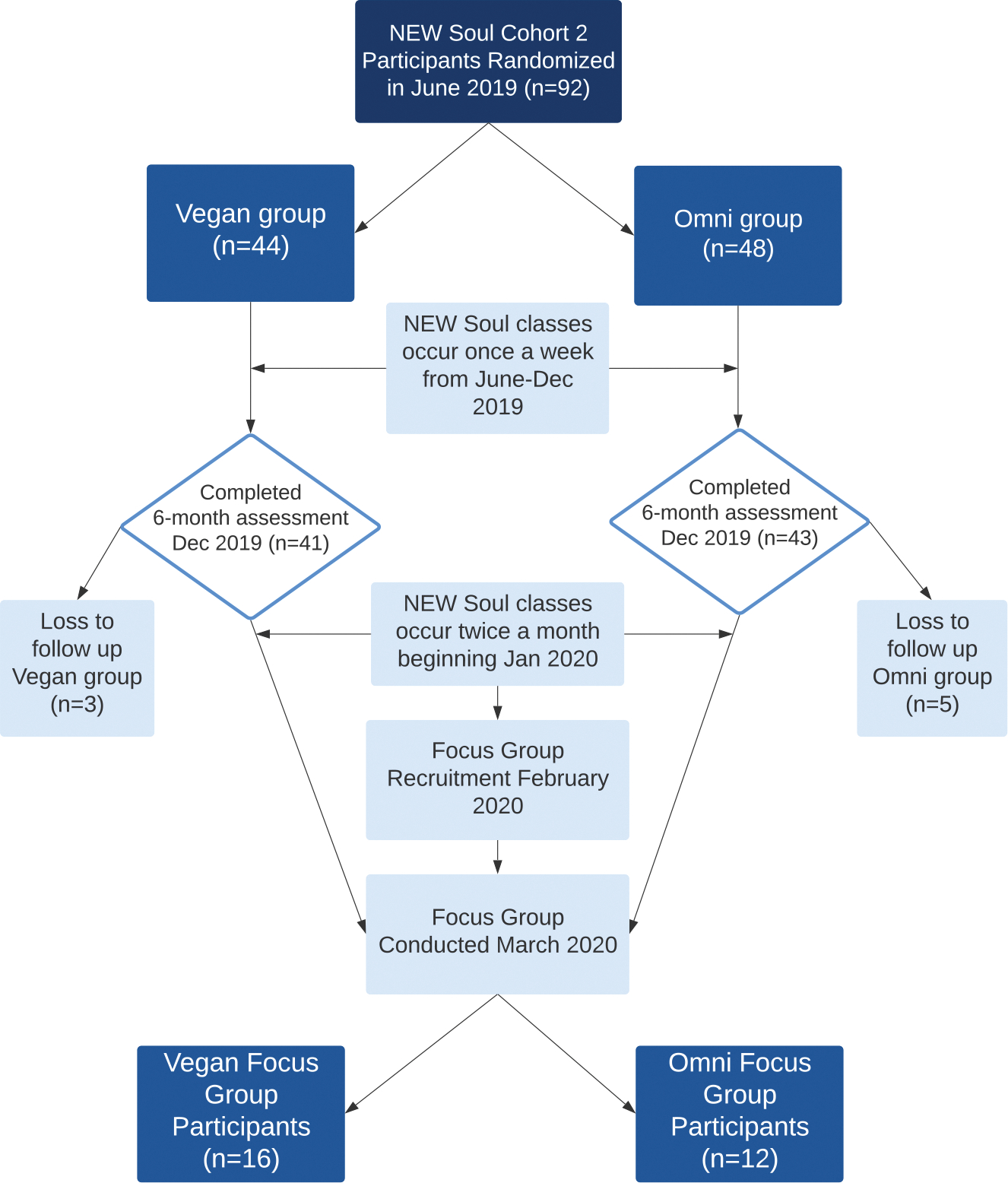

In total, 4 focus groups were conducted, which included 3 to 13 participants per group. The study comprised of 28 individuals (21 female participants; 16 vegan participants) who were all participating in the NEW Soul program nearing their 1-year mark. See Figure 2 for NEW Soul study protocol flowchart. See the Table for participant demographics.

Figure 2.

Flowchart of the Nutritious Eating With Soul (NEW Soul) study protocol illustrating timeline of qualitative data collection.

Table.

Demographic characteristics of the drivers and barriers of nutrition self-efficacy for African American participants following a plant-based vegan or a low-fat soul food diet21

| Characteristic | NEW Soula participants at 6-mo mark | NEW Soul focus group participants |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| ← n → | ||

| n | 84 | 28 |

| ← mean (SD) → | ||

| Age | 50.5 (9.8) | 52.5 (8.7) |

| ← n (%) → | ||

| Gender | ||

| Female | 63 (75) | 21 (75) |

| Male | 21 (25) | 7 (25) |

| African | 84 (100) | 28 (100) |

| American Race | ||

| ← mean (SD) → | ||

| BMI b | 35.8 (6.4) | 35.4 (6.5) |

| ← n (%) → | ||

| Diet group | ||

| Omnic | 43 (51) | 12 (43) |

| Vegan | 41 (49) | 16 (57) |

| Education | ||

| High school | 3 (4) | 1 (4) |

| Some college | 17 (20) | 4 (14) |

| College graduate | 34 (40) | 12 (43) |

| Advanced degree | 30 (36) | 11 (39) |

| Occupation status | ||

| Employed | 63 (75) | 21 (75) |

| Self-employed | 8 (10) | 3 (11) |

| Out of work | 1 (1) | 0 |

| Homemaker | 2 (2) | 0 |

| Retired | 8 (10) | 3 (11) |

| Student | 1 (1) | 0 |

| Unable to work | 1 (1) | 1 (4) |

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 20 (24) | 5 (18) |

| Married | 47 (56) | 15 (54) |

| Divorced or separated | 14 (17) | 6 (21) |

| Widowed | 2 (2) | 2 (7) |

| Partnered/living with someone | 1 (1) | 0 |

NEW Soul = The Nutritious Eating With Soul study.

BMI = body mass index.

Omni = omnivorous.

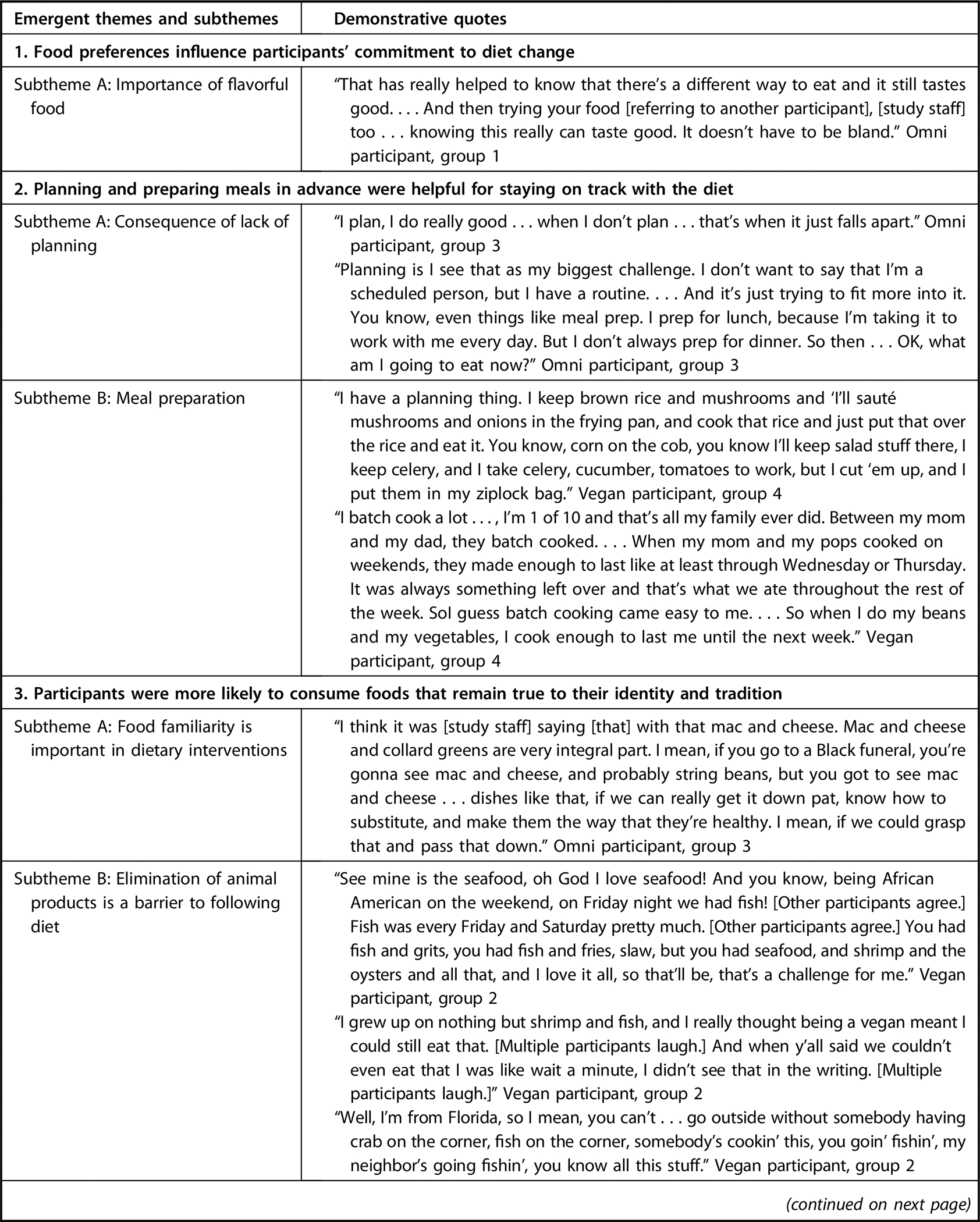

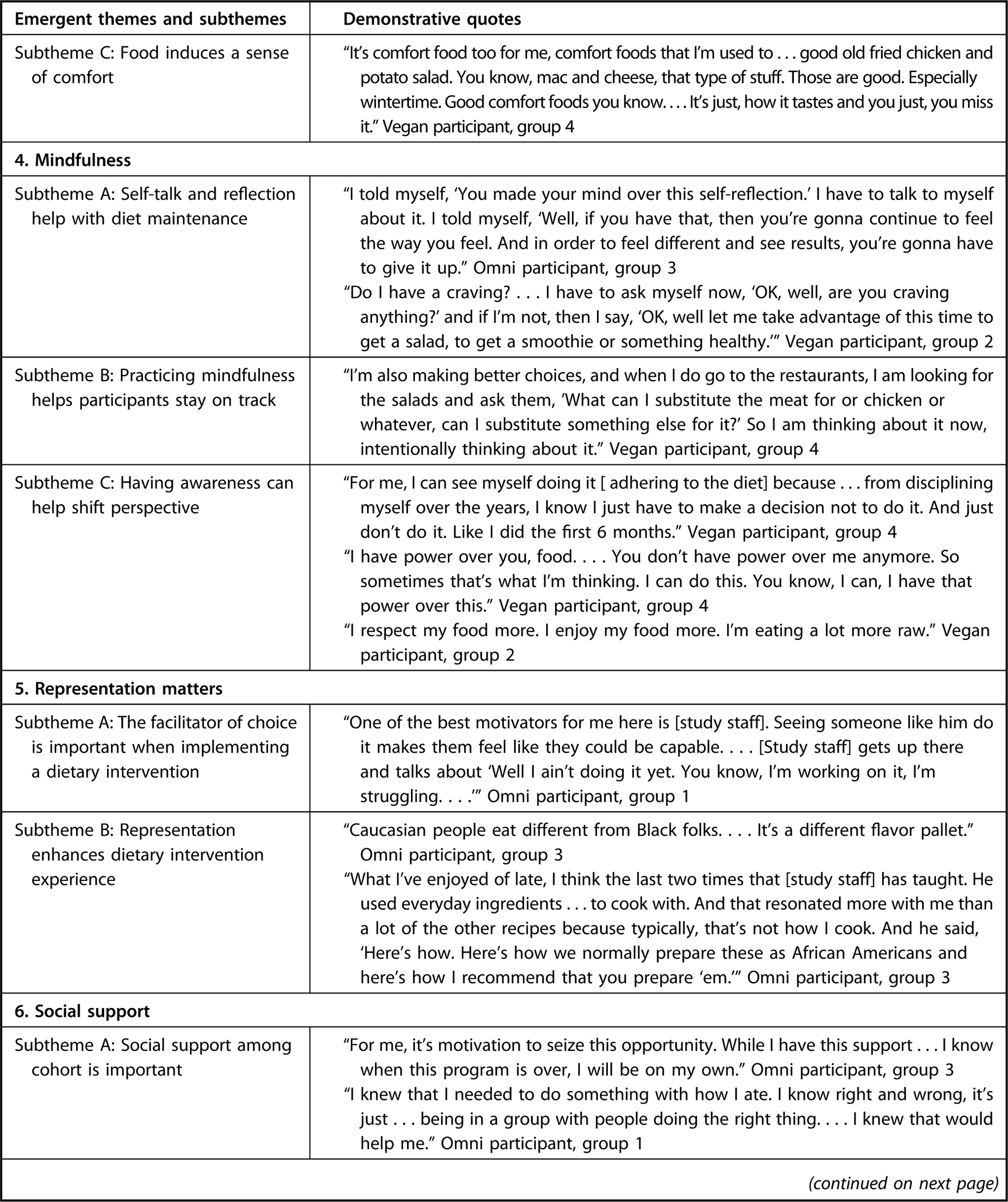

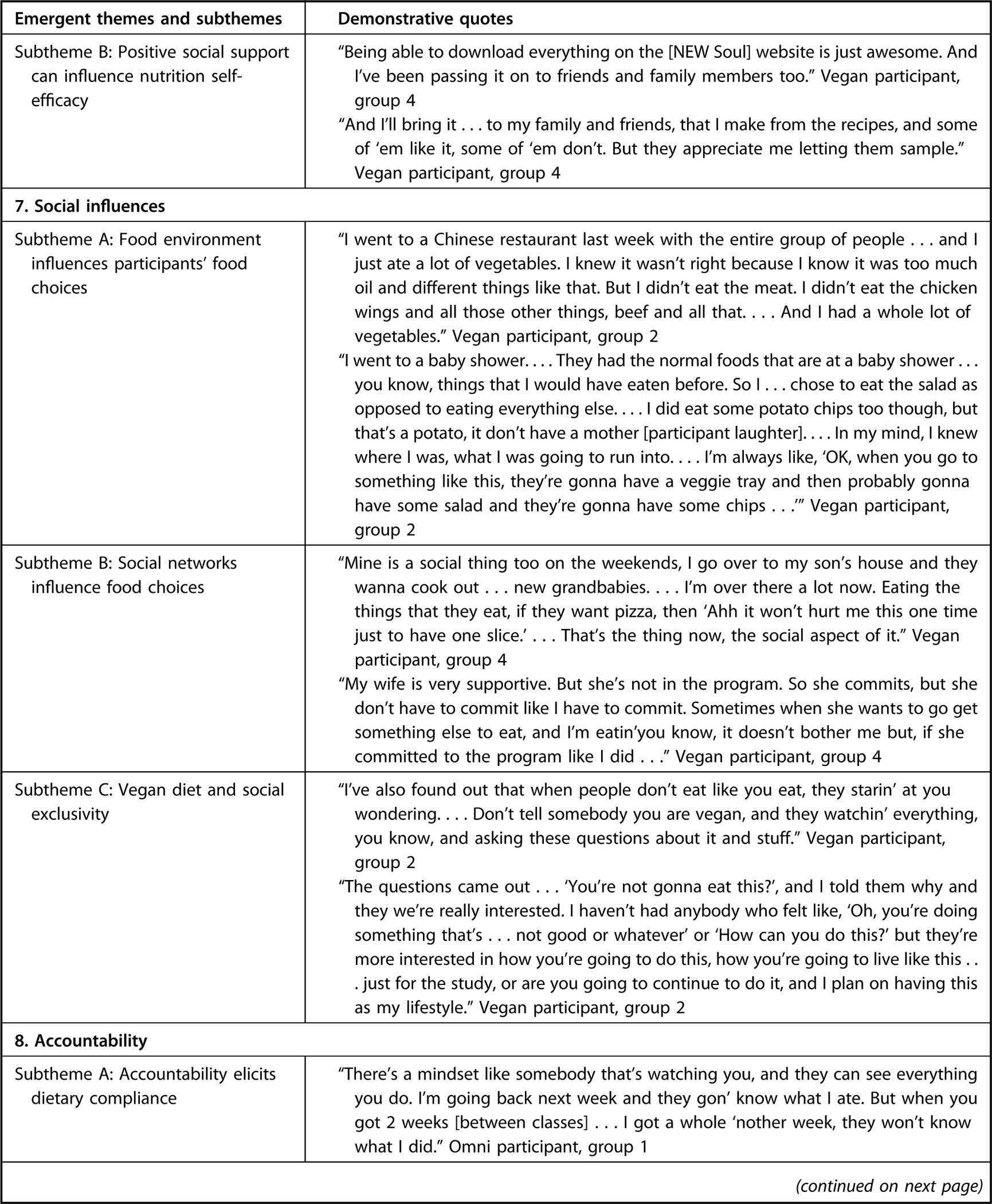

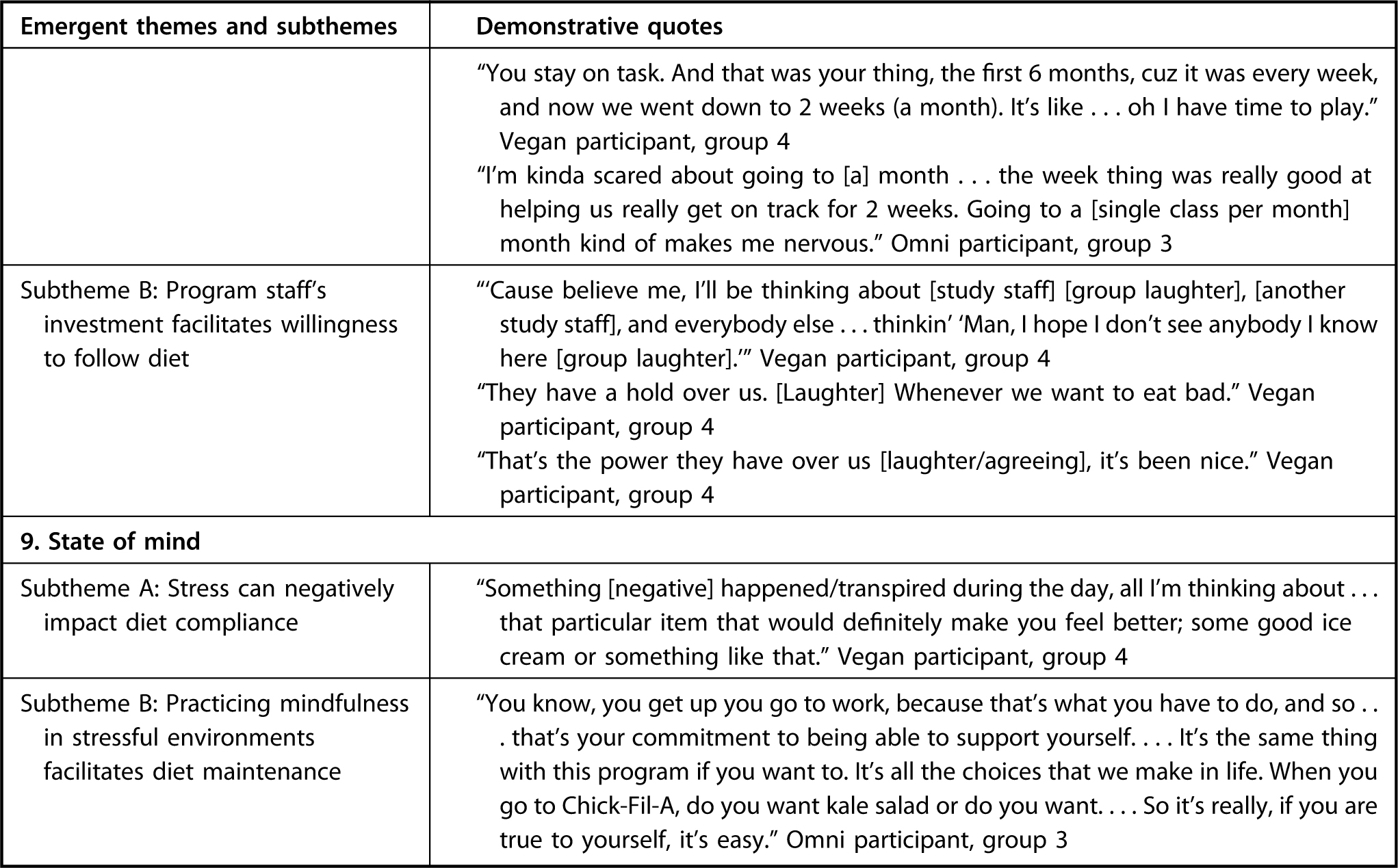

The 9 themes found to elicit nutrition self-efficacy were: (1) food preference, (2) planning/preparation, (3) identity and tradition, (4) mindfulness, (5) representation, (6) social support, (7) social influence, (8) accountability, and (9) state of mind. Representative quotes are provided for each theme. Given that both diets were very focused on plant-based eating styles and elimination or reduction in animal product intake and represented a departure from usual eating habits, both diet groups were analyzed together. The 9 overall themes emerged among all focus groups. See Figure 3 for a summary of themes, subthemes, and demonstrative quotes.

Figure 3.

Themes, subthemes, and demonstrative quotes on the drivers and barriers of nutrition self-efficacy for African American participants following a plant-based vegan or a low-fat soul food diet21

Theme 1: Food Preference

In both the vegan and omni groups, participants reported that taste was an important factor that influenced their decision to follow their assigned diet. Participants emphasized that they enjoyed foods that were “flavorful” or “tasted good.” The participants explained that the NEW Soul cooking demonstrations were especially helpful as they introduced new ways of flavoring food.

“I think that the study is going to help me eat better . . . I’ve learned to make the food taste better.” Omni participant, group 1

Theme 2: Planning and Preparation

Participants identified planning and preparation as an important factor in their ability to follow their assigned diet. Many participants indicated that if they failed to plan ahead, they would likely make food decisions based on convenience (See the Table, subtheme 2A: consequence of lack of planning), which oftentimes included fast foods and sugary, salty, and oily snacks. Conversely, participants shared that planning contributed to daily successes. One participant added that because he witnessed his parents successfully plan meals in childhood, he found it easy to plan and prepare meals in adulthood (see the Table, subtheme 2B: meal preparation). Success with following the diet occurred more during the workweek than the weekends as a participant explained that she struggled to follow the diet on the weekend due to a lack of planning.

“You didn’t plan to cook for the weekend. I only planned during the week for my lunch and my dinner because of work. . . . I don’t think about planning for the weekend so then it’s like, ‘Oh what imma eat?’ I guess I’ll stop and get me some crab legs, or . . . stop and get this . . .” Vegan participant, group 4

Theme 3: Identity and Tradition

The participants expressed that maintaining the diet was facilitated when foods presented in class had a familiar taste or resembled AA cuisines because it connected closely with their culture and identity. A vegan participant explained that she favored recipes provided by the NEW Soul team if it elicited a sense of familiarity.

“We had the lasagna the other night [during NEW Soul class]. . . . That was really good to see. . . . It was almost like it was that comfort food I finally tasted, you know? Like ‘mmm-mm,’ this is really hearty, you know. So that’s what I felt with the lasagna.” Vegan participant, group 4

Many of the participants appreciated when their meals brought a feeling of nostalgia and comfort (see the Table, subthemes 3A: food familiarity is important in dietary interventions and 3C: Food induces a sense of comfort), and if they sensed that this feeling was missing, they were likely to revert to old eating patterns. Some participants in the vegan group were okay with not eating meat, but others had more difficulties complying with the diet because animal products were an integral part of their upbringing (see the Table, subtheme 3b: elimination of animal products is a barrier to following diet). Other participants had trepidation about the diet, but changed their mind as the study continued:

“I was adamant I did not want to be part of the vegan group....I love bacon and seafood. I’m from Charleston but I stuck with it. I stuck with it, and it has been absolutely wonderful. I mean, I do not miss eating meat. . . . It has been very good.” Vegan participant, group 2

Theme 4: Mindfulness

According to participants, being mindful and participating in self-talk helped rationalize their thinking and made it easier for them to follow the diet.

“I’m telling myself, ‘Oh, you know, you don’t want that. That’s not what you’re supposed to have.’” Vegan participant, group 2

Participants were also cognizant of the challenges that they face, and they explained that being disciplined helps them persevere (see the Table, subthemes 4B: practicing mindfulness helps participants stay on track and 4C: having awareness can help shift perspective). One participant explained that she takes advantage of incidences where she is not craving unhealthy foods, and she uses that as an opportunity to eat healthier foods (see the Table, subtheme 4A: self-talk and reflection helps with diet maintenance).

Theme 5: Representation

The participants explained that representation was important for them in following the NEW Soul program and their assigned diets. Because the moderators reflected the participants racially and had similar experiences (1 moderator was also going through a weight loss journey), the participants were encouraged and committed to following through with the program (see the Table, subthemes 5A: the facilitator of choice is important when implementing a dietary intervention and 5B: representation enhances dietary intervention experience). The participants also agreed that when the moderators are open and honest (the moderator shared some of his setbacks to losing weight) it motivated them and made it easier for them to relate.

“Facilitators . . . like the choice of the facilitator really matters . . . [study staff] matters.” Omni participant, group 1

Theme 6: Social Support

Support among the cohort also helps with participants’ success in following the diet. The participants explained that also having support from their family, spouse, friends, and NEW Soul team increased their likelihood of maintaining the diet.

“When it comes to the meat, my whole family has reduced their meat intake.” Omni participant, group 3

Many of them shared recipes with their support systems and found them to be receptive to their diet (see the Table, subthemes 6A: social support among cohort is important and 6B: positive social support can influence nutrition self-efficacy).

Theme 7: Social Influences

The participants agreed that their social surroundings influenced their eating behavior and ability to maintain their diet. The participants who expressed greater efficacy behavior found it easier to stick to the diet regardless of social influences. However, those who described lower-efficacy behavior stated that family and social gatherings sometimes have a negative influence on whether they followed their diet (see the Table, subtheme 7B: social networks influence food choices).

“[Comfort foods can] make you go back to some of those old habits . . . ‘cause you’re with family . . . You know, gatherings.” Vegan participant, group 4

Some participants also found it difficult to eat in public because their diet tended to be the focus of conversations; sometimes in a judgmental way (see the Table, subtheme 7C: vegan diet and social exclusivity). The participants also agreed that if their spouses were on the same diet as them, compliance would be easier. This demonstrates the importance of social support when following a new diet. Social support can operate on individual (eg, partner), social (eg, family), and environmental (eg, restaurant choices) levels.31 The influences that support dietary changes can contribute to greater nutrition efficacy.

Theme 8: Accountability

The participants agreed that having accountability mechanisms help keep them on track with their goals. Some participants also agreed that switching from weekly to biweekly classes hindered their progress (see the Table, subtheme 8A: accountability elicits dietary compliance). They reported eating differently in the weeks that they have class compared with the weeks that they did not have class. One participant stated that when she was going to class once a week, she felt a greater responsibility to follow the diet because she knew the NEW Soul staff would ask about her progress (see the Table, subtheme 8B: program staff’s investment facilitates willingness to follow diet). The participants explained that it was hard for them to “fail” when they think of the NEW Soul team members and their influence that the team has on them. Some felt a sense of responsibility and duty to follow the diet.

“Who . . . said that we needed the magnet of [study staff’s] face to put on your refrigerator? To remind you not to eat something!” Omni participant, group 3

Theme 9: State of Mind: Stress

There were mixed findings on how stress influenced eating patterns. The participants that described an easier time with following the diet saw stress as motivation, helping with diet compliance. These participants viewed challenges and stressors as another life event that they accept and are willing to overcome. However, participants who described lower levels of efficacy behaviors were negatively impacted by stress and were less likely to comply with the diet (see the Table, subthemes 9A: stress can negatively impact diet compliance and 9B: practicing mindfulness in stressful environments facilitates diet maintenance).

“I’m a snacker when, I travel, I snack. When . . . I’m stressed, it’s like I’m snacking without even realizing it . . . and even with sweets, I’m not a real big sweet eater, but when I want them, I just kind of want ‘em.” Omni participant, group 1

DISCUSSION

The aim of this qualitative study was to assess drivers and barriers of nutrition self-efficacy for participants in the NEW Soul program following 1 of 2 healthy soul food diets. More specifically, we examined the role that self-efficacy plays in participants’ likelihood in following their diet. Utilizing Bandura’s self-efficacy theory of behavior change, we identified that participant’s self-efficacy was influenced by mastery experiences, vicarious experiences, social persuasion, and emotional states. When these facets were apparent either during the NEW Soul classes or in participants’ social environment, they expressed confidence and capability to perform behaviors necessary to comply with their assigned diet. This study adds to the limited research on assessing vegan and low-fat diet compliance using qualitative methods with AA individuals participating in a long-term nutrition behavior intervention. Furthermore, this research elucidated the role that motivation has on nutrition self-efficacy. Next we detail how the themes identified in this study relate to the 4 components of self-efficacy described by Bandura.

Vicarious Experiences

Vicarious experiences or social role modeling (eg, having a trusted person modeling desired behavior) helps build participants’ motivation because when they see people like themselves succeed, individuals begin to believe that they also have the capabilities to achieve comparable activities.32 The NEW Soul program includes persons in the community to lead various portions of the class with the goal of increasing trust and engagement among the participants. The participants noted that because the NEW Soul facilitators were AA and also working on improving their diet, they felt a connection and were motivated to follow their assigned diet. Identity and tradition (eg, providing recipes that closely resemble foods in AA culture) were also important components that affected diet compliance. Our participants expressed that finding comfort in what they were eating increased the likelihood that they will continue eating that food. This suggests that providing a sense of familiarity in veganized or low-fat, meat-reduced culturally tailored cuisines may be key to seeing long-term diet adaptation. This finding is consistent with the 2 studies that found that dietary adherence in patients with diabetes is related to social and cultural factors.33,34 Epstein et al found that AAs had lower dietary adherence to the DASH diet compared with White participants, and AAs identify culturally tailored interventions as a mechanism to address this disparity.35 Findings with the NEW Soul intervention are consistent with this hypothesis, though quantitative analysis is needed to further specify this relationship.

This study also found that representation (eg, leaders sharing similar racial and psychosocial traits) was an important driver for participants’ commitment to the NEW Soul program and sticking to the diet. These results are consistent with a study that found interventions involving community health workers were beneficial in improving glycemic control among AA and Latinos with diabetes.36 Furthermore, a study on a diabetes prevention nutrition program among AA women found that cultural relevance was significantly associated with program satisfaction and diet pattern changes.37 To our knowledge, this study is the first to identify the importance of representation as a facilitator in following a diet in a nutrition intervention trial. It adds to literature because it suggests that in combination with culturally tailored recipes being true to identity and rooted in tradition, having represented individuals demonstrate these meals will likely result in efficacy behaviors, like sharing recipes with loved ones.

Social Persuasion

Social persuasion (eg, providing encouraging words of support) through social support and accountability influence human behavior.32 Individuals believe that they can accomplish tasks when they are encouraged by an authoritative and trustworthy figure. Therefore, people who are told that they possess the capabilities to accomplish desired behaviors will likely result in a greater effort to accomplish the task.32 The present study shows how accountability (eg, being held responsible for behaviors) influenced participants’ nutrition self-efficacy. The participants explained that being held accountable by the NEW Soul staff allows them to stay on track with their diet. Aside from classes, the NEW Soul staff are available for one-on-one consultations, monthly make-up classes, and monthly morning workouts. The participants expressed that more frequent interactions helped them uphold self-responsibility and having less frequent classes hindered their progress. Epstein et al suggested that regular interactions with study staff encouraged self-monitoring behaviors among the participants.35 Along with the support received from the NEW Soul staff, the participants stated the importance of having social support (eg, spouse, family, coworkers, and friends). This finding is congruent with Miller and DiMatteo’s study, which found that family members play a major role in patients’ adherence to their treatment, and without family, adherence will be difficult and sometimes impossible to achieve.38 Personal connections between participants and study staff can facilitate this social support, which may be particularly important for participants that do not have an outside source of social support. Therefore, our study adds to current literature as it suggests support from both the community leader and program staffs aids with individuals’ diet compliance.

Mastery Experience

According to Bandura, self-efficacy increases mastery experiences (eg, successfully performing a task) because mastery experiences build coping skills and give individuals the belief that they have control over potential threats.32 Planning and preparation were very important factors for self-reported diet adherence among the participants in the present study. The participants explained being more compliant with the diet during the weekday as they often prepared lunches for workdays. They were less compliant during the weekends when they followed a less structured schedule. These results are congruent with prior research that found that planning facilitates dietary consumption.21,39,40 When participants in the present study veered from their assigned diet, it was often based on convenience or lack of planning. Therefore, as suggested in a previous study, having a plan of what to eat and having the items readily accessible makes it easier for individuals to comply with the diet.39 In the present study, food preferences (eg food taste) were also a determinant in whether the participants would follow the diet. Participants explained when the food tastes good, they would not only make it for themselves, but also for their loved ones. Existing literature has found that taste and sensory experiences influence food purchasing and consumption, but most of these studies are observational and/or cross-sectional experiments.41e43 This study extends that work by exploring this relationship in the context of a dietary intervention. Our findings suggest that food tastes are critical to maintaining dietary adherence. Nutrition interventions often focus primarily on nutrient profiles (eg, DASH diet; carbohydrate-controlled diabetes diet). Although these aspects are important, it is also critical to address taste preferences to facilitate dietary adherence and maintenance.

Somatic and Emotional States

A person’s self-efficacy in coping with situations is greater when they have a positive somatic and emotional state.32 The present study found that participants’ negative somatic and emotional states deterred healthy eating behaviors. Some NEW Soul participants reported better compliance with the diet when they were less stressed. The participants explained that stressful situations triggered mindless eating, consistent with other studies that found a relationship between stress and negative eating habits among various age groups.44–46 Life stressors are associated with a greater preference for foods that are higher in fats and sugars.47 However, some NEW Soul participants explained that being placed in a stressful environment (fast-food restaurants with multiple food options) did not deter their food choices when they practiced being mindful in that situation. Bandura explains that high stressors may not always equate to negative outcomes.32 Previous interventions that use mindfulness to promote metabolic risk reduction in AA adults found that mindfulness-based eating can reduce perceived stress, body mass index, and calorie and fat intake, and promote weight maintenance and increases in spiritual well-being.48,49 Our present study suggests that the practice of mindfulness is important in individuals’ perceived ability to follow their diets at 6 months. Our findings build on and support previous research into drivers that influence an individual’s motivation to making diet changes. Further research is needed on mindful eating and stressed-induced mindless eating.

Strengths and Limitations

This study has several strengths. Participants were able to report drivers and barriers for following their assigned diet as they were experiencing the diet. This is more beneficial than conducting focus groups before or after an intervention is implemented as it (1) gives a more accurate depiction of what is occurring and (2) allows for study staff to adjust to the needs of the participants. Also, participants may have been comfortable honestly sharing information given that there was a level of comfortability between moderators and the participants, increasing the trustworthiness of the data. Another strength worth mentioning is that neither vegan nor omni participants mentioned cost as a barrier to following the diet, indicating that the NEW Soul program was able to provide affordable food choices for both groups. Few studies have adopted qualitative designs to research insight on factors that help or hinder participants’ ability to follow a healthy diet alternative. A qualitative research approach is important because more needs to be known about what factors contribute to the success of dietary interventions among AA participants.

This study must also be interpreted in consideration of some limitations. Individuals in our focus groups ranged from 3 to 13 people. Focus groups are more effective when they have 7 to 12 individuals per group.24 Participants signed up for times a month in advance, but some participants had to switch times, which resulted in uneven group sizes. With bigger groups, there are concerns that power structure and group dynamics may influence the response50; however, the NEW Soul participants had been together for about 9 months and were already comfortable speaking with each other. Also, participants were accustomed to this discussion environment as it was done in every class. Purposive sampling was used to recruit participants for focus groups. Given that researchers could only obtain information from individuals who were participating in the NEW Soul study, there were a limited number of potential participants. Furthermore, it is possible that NEW Soul participants who were not frequently attending classes might not have been reached. Thus, we could not use a data saturation approach because all interested eligible participants took part in focus groups. Furthermore, participants in this study were majority women and college educated. Therefore, our findings cannot be generalized to the entire AA population. Finally, our study did not objectively assess dietary adherence but rather how confident our participants felt they were with adherence. Providing a quantitative measure of dietary adherence would increase the study’s validity.

CONCLUSION

Our results demonstrate the prominent role that self-efficacy plays in participants’ motivations toward nutrition self-efficacy. Mastery experiences, vicarious experiences, social persuasion, and somatic and emotional states were all common themes in participant-reported sources of motivation. Nutrition interventions are likely to elicit positive behavioral outcomes if these 4 factors that enhance self-efficacy are incorporated into program development.

RESEARCH SNAPSHOT.

Research Question:

What are motivators and facilitators for following a vegan or a low-fat reduced-animal-product diets among participants in the Nutritious Eating With Soul (NEW Soul) dietary intervention?

Key Finding:

Successfully choosing foods that aligned with the diet (mastery), watching others cook low-fat/vegan soul food meals (vicarious experiences), positive feedback and support (social persuasion), and experiencing positive psychological arousal (somatic and emotional state) were motivators for sticking to the diet. Nine themes were identified that facilitated nutrition self-efficacy: food preference, planning and preparation, identity and tradition, mindfulness, representation, social support, social influence, accountability, and state of mind.

PRACTICE IMPLICATIONS.

This study has several implications for practice. First, when implementing community behavioral interventions, registered dietitian nutritionists and nutrition health professionals should be invested in providing instruction in culturally tailored healthy diets to participants. Also, being conscious about staffing is important for participants’ success. Staff who are responsible for leading discussion in nutrition behavioral interventions should be representative of the population in which they are working. These discussion leaders should act as models for the participants, building trust and relationships among them. Lastly, staff should anticipate difficulties in adherence when contact time for the intervention decreases. Therefore, providing a variety of continued methods for interaction may be helpful.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Mary Wilson for help with recruitment; John Bernhart for guidance with data training and collection; and the BRIE lab for guidance on the interview and focus group guides.

FUNDING/SUPPORT

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01HL135220. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. This project was also funded by the University of South Carolina’s Magellan Scholar Award.

Footnotes

STATEMENT OF POTENTIAL CONFLICT OF INTEREST

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Contributor Information

Nkechi Okpara, doctoral student, Department of Health Promotion, Education, and Behavior, and the Prevention Research Center, Arnold School of Public Health, University of South Carolina, Columbia..

Christina Chauvenet, postdoctoral fellow, Prevention Research Center, Arnold School of Public Health, University of South Carolina, Columbia..

Katherine Grich, research assistant, Department of Health Promotion, Education, and Behavior, and the Prevention Research Center, Arnold School of Public Health, University of South Carolina, Columbia..

Gabrielle Turner-McGrievy, Department of Health Promotion, Education, and Behavior, and the Prevention Research Center, Arnold School of Public Health, University of South Carolina, Columbia..

References

- 1.Hales CM, Carrol MD, Fryar CD, Ogden CL. Prevalence of obesity and severe obesity among adults: United States, 2017e2018. NCHS Data Brief No. 360, February 2020. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Published February 27, 2020. Accessed February 5, 2021, http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db360.htm [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Health of Black or African American population. FastStats. Published January 12, 2021. Accessed February 5, 2021, https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/blackhealth.htm [Google Scholar]

- 3.Howard G, Howard VJ. Twenty years of progress toward understanding the stroke belt. Stroke. 2020;51(3):742–750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Adult obesity prevalence maps. Published 2021. Accessed September 15, 2021, https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/data/prevalence-maps.html. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Poe T The origins of soul food in black Urban Identity: Chicago, 1915e1947. Am Stud Int. 1999;37(1):4–33. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lumpkins CL. Soul food. African American Studies Center. 2009. 10.1093/acref/9780195301731.013.46221 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Covey HC, Eisnach D. What the Slaves Ate: Recollections of African American Foods and Foodways From the Slave Narratives. Greenwood Press/ABC-CLIO; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bower A African American Foodways Explorations of History and Culture. University of Illinois Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Owen N, Sparling PB, Healy GN, Dunstan DW, Matthews CE. Sedentary behavior: Emerging evidence for a new health risk. Mayo Clin Proc. 2010;85(12):1138–1141. 10.4065/mcp.2010.0444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kant AK, Graubard BI. Secular trends in regional differences in nutritional biomarkers and self-reported dietary intakes among American adults: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 1988e1994 to 2009e2010. Public Health Nutr. 2018;21(5):927–939. 10.1017/s1368980017003743 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Howard G, Cushman M, Moy CS, et al. Association of clinical and social factors with excess hypertension risk in Black compared with White US adults. JAMA. 2018;320(13):1338. 10.1001/jama.2018.13467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Al-Shaar L, Satija A, Wang DD, et al. Red meat intake and risk of coronary heart disease among US men: Prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2020;371:m4141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen Z, Glisic M, Song M, et al. Dietary protein intake and all-cause and cause-specific mortality: Results from the Rotterdam Study and a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Eur J Epidemiol. 2020;35(5):411–429. 10.1007/s10654-020-00607-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tuso P Nutritional update for physicians: Plant-based diets. Perm J. 2013;17(2):61–66. 10.7812/tpp/12-085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Olfert MD, Wattick RA. Vegetarian diets and the risk of diabetes. Curr Diab Rep. 2018;18(11):101. 10.1007/s11892-018-1070-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dinu M, Abbate R, Gensini GF, Casini A, Sofi F. Vegetarian, vegan diets and multiple health outcomes: A systematic review with meta-analysis of observational studies. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2017;57(17):3640–3649. 10.1080/10408398.2016.1138447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Orlich MJ, Singh PN, Sabaté J, et al. Vegetarian dietary patterns and mortality in Adventist Health Study 2. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(13):1230–1238. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.6473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fraser G, Katuli S, Anousheh R, Knutsen S, Herring P, Fan J. Vegetarian diets and cardiovascular risk factors in black members of the Adventist Health Study-2. Public Health Nutr. 2015;18(3):537–545. 10.1017/S1368980014000263. FirstView:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rajati F, Sadeghi M, Feizi A, Sharifirad G, Hasandokht T, Mostafavi F. Self-efficacy strategies to improve exercise in patients with heart failure: A systematic review. ARYA Atheroscler. 2014;10(6):319–333. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pawlak R, Colby S. Benefits, barriers, self-efficacy and knowledge regarding healthy foods; perception of African Americans living in eastern North Carolina. Nutr Res Pract. 2009;3(1):56. 10.4162/nrp.2009.3.1.56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Doldren MA, Webb FJ. Facilitators of and barriers to healthy eating and physical activity for Black women: A focus group study in Florida, USA. Crit Public Health. 2013;23(1):32–38. 10.1080/09581596.2012.753407 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Turner-McGrievy G, Wilcox S, Frongillo EA, et al. The Nutritious Eating with Soul (NEW Soul) Study: Study design and methods of a two-year randomized trial comparing culturally adapted soul food vegan vs. omnivorous diets among African American adults at risk for heart disease. Contemp Clin Trials. 2020;88:105897. 10.1016/j.cct.2019.105897 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oldways. Oldways African heritage pyramid. Published 2021. Accessed September 15, 2021, https://oldwayspt.org/resources/oldways-african-heritage-pyramid

- 24.Harris JE, Gleason PM, Sheean PM, Boushey C, Beto JA, Bruemmer B. An introduction to qualitative research for food and nutrition professionals. J Am Diet Assoc. 2009;109(1):80–90. 10.1016/j.jada.2008.10.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bandura A Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control. W.H. Freeman; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Self-efficacy Bandura A.. In: Ramachaudran VS, ed. Encyclopedia of Human Behavior. Vol 4. Academic Press; 1994:71–81. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Green J, Thorogood N. Qualitative Methods for Health Research. Sage; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 28.International Pty QsRLtd 2018. https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo-qualitative-data-analysis-software/home.

- 29.Creswell JW. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Traditions. Sage; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tolley EE. Qualitative Methods in Public Health: A Field Guide for Applied Research. Jossey Bass; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 31.McCloskey DJ, McDonald MA, Cook J, et al. Community engagement: Definitions and organizing concepts from the literature. In: Principles of Community Engagement. 2nd ed. Bethesda, MD: NIH; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bandura A Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol Rev. 1977;84(2):191–215. 10.1037//0033-295x.84.2.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Garvin CC, Cheadle A, Chrisman N, Chen R, Brunson E. A community-based approach to diabetes control in multiple cultural groups. Ethn Dis. 2004;14(3 Suppl 1):S83–S92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Juárez-Ramírez C, Théodore FL, Villalobos A, et al. The importance of the cultural dimension of food in understanding the lack of adherence to diet regimens among Mayan people with diabetes. Public Health Nutr. 2019;22(17):3238–3249. 10.1017/s1368980019001940 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Epstein DE, Sherwood A, Smith PJ, et al. Determinants and consequences of adherence to the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension Diet in African-American and White adults with high blood pressure: Results from the ENCORE Trial. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2012;112(11):1763–1773. 10.1016/j.jand.2012.07.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Spencer MS, Rosland AM, Kieffer EC, et al. Effectiveness of a community health worker intervention among African American and Latino adults with type 2 diabetes: A randomized controlled trial. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(12):2253–2260. 10.2105/AJPH.2010.300106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Williams JH, Auslander WF, de Groot M, Robinson AD, Houston C, Haire-Joshu D. Cultural relevancy of a diabetes prevention nutrition program for African American women. Health Promot Pract. 2006;7(1):56–67. 10.1177/1524839905275393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Miller TA, Dimatteo MR. Importance of family/social support and impact on adherence to diabetic therapy. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2013;6:421–426. 10.2147/DMSO.S36368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gibson AA, Sainsbury A. Strategies to improve adherence to dietary weight loss interventions in research and real-world settings. Behav Sci (Basel). 2017;7(4):44. 10.3390/bs7030044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Larson NI, Perry CL, Story M, Neumark-Sztainer D. Food preparation by young adults is associated with better diet quality. J Am Diet Assoc. 2006;106(12):2001–2007. 10.1016/j.jada.2006.09.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kourouniotis S, Keast RSJ, Riddell LJ, Lacy K, Thorpe MG, Cicerale S. The importance of taste on dietary choice, behaviour and intake in a group of young adults. Appetite. 2016;103:1–7. 10.1016/j.appet.2016.03.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Renner B, Sproesser G, Strohbach S, Schupp HT. Why we eat what we eat. The Eating Motivation Survey (TEMS). Appetite. 2012;59(1):117–128. 10.1016/j.appet.2012.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McCrickerd K, Forde CG. Sensory influences on food intake control: Moving beyond palatability. Obes Rev. 2016;17(1):18–29. 10.1111/obr.12340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yau YH, Potenza MN. Stress and eating behaviors. Minerva Endocrinol. 2013;38(3):255–267. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Michels N, Sioen I, Braet C, et al. Stress, emotional eating behaviour and dietary patterns in children. Appetite. 2012;59(3):762–769. 10.1016/j.appet.2012.08.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hill DC, Moss RH, Sykes-Muskett B, Conner M, O’Connor DB. Stress and eating behaviors in children and adolescents: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Appetite. 2018;123:14–22. 10.1016/j.appet.2017.11.109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Torres SJ, Nowson CA. Relationship between stress, eating behavior, and obesity. Nutrition. 2007;23(11–12):887–894. 10.1016/j.nut.2007.08.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Woods-Giscombe CL, Gaylord SA, Li Y, et al. A mixed-methods, randomized clinical trial to examine feasibility of a mindfulness-based stress management and diabetes risk reduction intervention for African Americans with prediabetes. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2019;2019:1–16. 10.1155/2019/3962623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chung SY, Zhu S, Friedmann E, et al. Weight loss with mindful eating in African American women following treatment for breast cancer: A longitudinal study. Support Care Cancer. 2015;24(4):1875–1881. 10.1007/s00520-015-2984-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Leung FH, Savithiri R. Spotlight on focus groups. Can Fam Physician. 2009;55(2):218–219. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]