Abstract

To respond to the unintended consequences of prevention measures to reduce COVID-191 transmission, individuals and groups, including religious leaders, have collaborated to provide care to those negatively impacted by these measures. Amid these various efforts and interventions, there is a need to deepen our understanding of diverse expressions of care across various geographical and social contexts. To address this need, the objective of this study was to investigate how religious leaders in the Philippines practiced care for their communities by meeting emergency food needs amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Guided by an ethics of care theoretical orientation, we conducted 25 remote semi-structured interviews with Filipino religious leaders who partnered with a Philippines-based non-governmental organization (NGO) to mobilize essential food aid to their local communities. Through defining the efforts and activities of these religious leaders as care work, we found that religious leader experiences revolved around navigating care responsibilities, caring alongside others, and engaging holistically with the care work. Additionally, we observed how contextual factors such as the humanitarian settings where religious leaders worked, the partnership with an NGO, and the positionality of local religious leaders within their communities, fundamentally shaped the care work. This study expands our understanding of how care is practiced and experienced and also brings greater visibility to the experiences and efforts of local religious leaders in responding to humanitarian emergencies.

Keywords: Humanitarian response, COVID-19 pandemic, Religious leaders, Ethics of care, Non-governmental organizations, Philippines

1. Introduction

Unintended consequences resulting from essential public health measures during the COVID-19 pandemic have become a catalyst for people around the world to reach out to others – family members, friends, neighbors, strangers – to alleviate the negative impacts they observed. Indeed, voluntary efforts have been abundant in activities such as checking on others’ wellbeing, delivering medicine, staffing telephone helplines, delivering food, supporting the public health system, and assisting non-governmental organizations (NGOs) with delivering various services (Dodd et al., 2021; Mak and Fancourt, 2022; Marston et al., 2020; Roy and Ayalon, 2021; Trautwein et al., 2020).

Among volunteers, religious leaders have been particularly active. Not only have religious leaders adapted their services to accommodate health restrictions, but they have been instrumental in disseminating information, encouraging disease prevention activities, and promoting public health and safety measures (del Castillo et al., 2020; Frei-Landau, 2020; Mbivnjo et al., 2021; Osei-Tutu et al., 2021; Wijesinghe et al., 2022; Yoosefi Lebni et al., 2021). Beyond disease prevention and health promotion, religious leaders have been active in addressing a range of needs which have arisen during the pandemic. In an effort to address physical, mental, emotional, spiritual, and relational needs, religious leaders have mobilized food, hygiene items, clothes, and finances; offered psychological support, counseling, prayer, and spiritual support; provided shelter; found creative ways to foster belonging and resilience despite isolation measures; and shared messages of hope and faith with congregants (Arruda, 2020; del Castillo et al., 2020; Frei-Landau, 2020; Osei-Tutu et al., 2021). Indeed, concern has been raised regarding the wellbeing of religious leaders as their roles and responsibilities have shifted and expanded during the pandemic (Greene et al., 2020).

In the Philippines, where over 90% of the population identifies as religious (predominantly Catholic, in addition to Protestant and Muslim), local religious leaders have played a crucial role in providing stability, instilling hope, and meeting local needs during the pandemic (Calleja, 2020; Corpuz, 2021; del Castillo et al., 2020; Guadalquiver, 2021; Philippine Statistics Authority, 2019). In particular, due to President Rodrigo Duterte's implementation of nationwide community quarantines which were considered to be one of the longest and strictest lockdowns worldwide, food insecurity became a critical problem in the country, especially for individuals already experiencing extreme poverty prior to the pandemic (Angeles-Agdeppa et al., 2022; Hapal, 2021; Ong et al., 2020; Philippine Department of Agriculture, 2020; Republic of the Philippines Official Gazette, 2020a). Religious leaders responded to address the food crisis across the country by mobilizing food and other resources to provide for individuals in need (Dodd et al., 2023; Calleja, 2020; del Castillo et al., 2020; Hilario, 2020). In doing so, religious leaders were recognized by the Philippine government for filling an essential gap since government aid alone had not been sufficient (Calleja, 2020).

More broadly, we consider religious leaders to be individuals that provide support, comfort, and guidance to communities in which they are culturally, spiritually, and physically embedded (World Health Organization, 2020). They typically have comprehensive understanding of local networks and historical context (Lau et al., 2020; Oyo-Ita et al., 2021; Powell, 2014), are seen as reputable sources of information by their communities, and hold community relationships broadly characterized by trust (Lau et al., 2020; Harr and Yancey, 2014; Powell, 2014). Their care work can be situated among the not-for-profit 'point' of Razavi's "care diamond" (2007p.21), a well-established typology for the structure of care provision in society. Accordingly, existing evidence has revealed religious leaders to be valuable social agents for change in some contexts, particularly regarding health and well-being promotion (Adedini et al., 2018; Lau et al., 2020; Cohen- Dar and Obeid, 2017; Oyo-Ita et al., 2021; Rivera-Hernandez, 2015). Especially in religious societies – including the Philippines – religious leaders have a history of effective emergency response and contribution to humanitarian and disaster response, positioning them as experienced care workers within the COVID-19 pandemic (Ager et al., 2014, 2015; Sheikhi et al., 2021; Wilkinson, 2018; World Humanitarian Summit, 2016).

Indeed, in this study, we argue that the pandemic-related efforts of Filipino religious leaders can be understood as a type of care work, with nuanced dimensions that have not been extensively explored in the humanitarian or disaster response literatures. Accordingly, ethics of care (or care ethics) provides a theoretical underpinning for this research, in that it can be used to map the care work of religious leaders against established 'forms' of care, thus providing an entry point for deeper inquiry and characterization of this work. Ethics of care has its beginnings in feminist moral psychology and was initially identified as an alternative moral paradigm to dominant understandings of morality such as justice- and rights-based approaches (see Gilligan, 1982). The theory has since expanded to include a broad range of conceptualizations, fields, and disciplines (Bond and Barth, 2020; Hamington and Sander-Staudt, 2011; Kittay, 2011; Langford et al., 2017; Locke, 2017; Pols, 2015; Tronto, 1993, 2013). Due to the theory's wide theorization and application, there is no commonly held definition of care ethics (Engster and Hamington, 2015). However, a widely known and used description of care within care ethics is that which Fisher and Tronto (1990) have developed: “…a species activity that includes everything that we do to maintain, continue, and repair our ‘world’ so that we can live in it as well as possible” (p.40). Further, several core dimensions of care ethics are commonly endorsed by theorists, which Engster and Hamington (2015) have identified as: relationality and interdependence, responsiveness to others, the inseparability of context, crossing the public-private divide, and the inherence of emotion.

More recently, scholars have called to further expand theorization surrounding care ethics to explore diverse forms of care as situated in various geographical and social contexts (Bartos, 2019; Hanrahan and Smith, 2020; Kallio, 2020; Raghuram, 2016). Importantly, Raghuram (2016) has contended the need to “emplace” (p.512) care beyond the Global North and “trouble” (p.515) care by exploring unfamiliar forms of care. Overall, there is a call for more critical engagement with care to explore uncomfortable cases (Bartos, 2018) and “stretch the boundaries of care” (Bartos, 2019, p.769).

Previously, ethics of care has been explored in relation to NGOs and civil society organizations (Collins, 2015; Dodd et al., 2022), food and livelihood security (Giraud, 2021; Hanrahan, 2015), community voluntary work (Tuyisenge et al., 2020), faith actors (Barnes, 2020), the COVID-19 pandemic (Gary and Berlinger, 2020), and social support in the Philippines (Ofreneo et al., 2022). While interest in the theory is growing, there is a need to better understand how care is practiced by local religious leaders in crisis settings in the Philippines particularly and the Global South broadly, including instances that involve partnership with NGOs, and the nuances inherent to this care work. In addition, there is a need to expand our understanding of care as practiced in diverse forms and contexts, through the use of a theoretical lens that has less often been applied to an examination of religious leaders' contributions within humanitarian and disaster response literatures. To address these gaps, the objective of this study was to investigate how local religious leaders in the Philippines practiced care for their communities by meeting food needs during the COVID-19 pandemic by partnering with a Philippines-based NGO, International Care Ministries (ICM). In doing so, we aim to respond to calls from care ethics scholars to diversify our study of care, as well as provide greater visibility and insight into the care practice of local religious leaders in humanitarian settings.

2. Methods

2.1. Study context

This study was grounded in partnership between researchers from International Care Ministries (ICM; Philippines) and the University of Waterloo (Canada). ICM is a faith-based NGO that has served individuals experiencing extreme poverty, whom they identify as ultra-poor,2 , in the Philippines since 1992. ICM offers poverty-alleviation programs through its 12 regional bases located across the Visayas and Mindanao. In response to the pandemic-aggravated food crisis, ICM activated its Rapid Emergencies and Disasters Intervention (REDI), a program intended to mobilize humanitarian aid. REDI operates through a broad network of approximately 15,000 community volunteers, all of whom are local religious leaders (Dodd et al., 2023). Volunteer religious leaders play a critical intermediary role as they assess community needs to determine a required amount of aid, connect with ICM to make their request, then, upon approval, obtain ICM's aid and distribute it to community members. During the pandemic, aid mobilized through REDI included fortified rice packs, seeds, and other essential items, and ICM together with religious leaders reached 5.3 million people with resources, providing 14 million meals and 314 million vegetable seeds (International Care Ministries, 2021).

In this pandemic context, ICM identified a need to better understand the experiences of religious leaders with REDI implementation. Due to ongoing pandemic restrictions, the study was conducted remotely. Thus, ICM's Bacolod regional base in the province of Negros Occidental was chosen as the study site as ICM staff working at this base had previously facilitated remote research. Further, focusing our scope of inquiry to one province allowed a more in-depth investigation into how regional COVID-19-related public health measures shaped experiences of REDI implementation. To build a contextual foundation for the research team, ICM shared documents related to REDI, and consultations were held with ICM staff members who were involved in administering REDI to discuss program operations.

2.2. Theoretical framing: Ethics of care

This research was framed by an ethics of care theoretical orientation. Ethics of care was chosen for its usefulness in understanding and characterizing the community engagement of religious leaders through REDI implementation. Particularly, Fisher and Tronto's (1990) comprehensive view of care provided an inclusive lens through which to consider religious leaders’ efforts to address emergency food insecurity in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. In addition, more recent calls by care theorists (Bartos, 2019; Hanrahan and Smith, 2020; Kallio, 2020; Raghuram, 2016) to explore diverse forms and locatedness of care provided a compelling foundation for engagement with ethics of care throughout the project. Accordingly, ethics of care broadly informed study design, data analysis, and research presentation.

2.3. Participant recruitment

Participants were recruited for this study based on their involvement with REDI during the COVID-19 pandemic. All participants were recruited through the Bacolod regional base in the province of Negros Occidental. Purposive sampling (Boddy, 2016; Green and Thorogood, 2014; Malterud et al., 2016; Patton, 1990) with a combined a priori and ongoing sampling approach (Gentles et al., 2015) was used to recruit individuals of diverse ages, genders, and geographical locations with the aim to explore a range of experiences. Individuals were contacted by an ICM staff member through a pre-existing relationship, informed of the study, and invited to participate voluntarily. A total of 25 religious leaders who resided in 17 distinct communities across Negros Occidental agreed to participate in the study (see Fig. 1 ; Table 1 ). Participants included female and male individuals between the ages of 34 to 70 years and were all Christian religious leaders (e.g., pastors or pastoras) (see Table 1). All participants provided informed oral consent for participation and audio recording of their interview. Research ethics approval was obtained from the University of Waterloo (ORE #42565).

Fig. 1.

Map of the study region: Negros Occidental (Bacolod, Silay, E.B. Magalona, Cadiz, Sagay, Escalante, Don Salvador Benedicto, San Carlos, La Castellana, Isabela, Himamaylan, Kabankalan, Sipalay, Cauayan, Ilog, Hinigaran, Bago), Philippines.

Table 1.

Assigned pseudonyms and demographic characteristics of interviewees who were religious leaders engaged in the implementation of International Care Ministries’ Rapid Emergencies and Disasters Intervention program (n = 25).

| Pseudonym | Gender | Age | Location | Occupation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alejandro | Male | 52 | Bacolod | Pastor |

| Gloria | Female | 65 | Bacolod | Pastora |

| Jerome | Male | 62 | Bacolod | Pastor |

| Arnold | Male | 55 | Bago | Pastor |

| Simon | Male | 66 | Bago | Pastor |

| Charles | Male | 46 | Cadiz | Pastor |

| Evelyn | Female | 51 | Cadiz | Pastora |

| Nelson | Male | 45 | Cauayan | Pastor |

| Theo | Male | 44 | Don Salvador Benedicto | Pastor |

| Eduardo | Male | 58 | E. B. Magalona | Pastor |

| Dinah | Female | 47 | Escalante | Pastora |

| Vincent | Male | 50 | Escalante | Pastor |

| Marie | Female | 62 | Himamaylan | Pastora |

| Benilda | Female | 51 | Hinigaran | Pastora |

| Grace | Female | 34 | Ilog | Pastora |

| Dalisay | Female | 42 | Isabela | Pastora |

| Benjie | Male | 59 | Kabankalan | Pastor |

| Francisco | Male | 54 | Kabankalan | Pastor |

| Lucas | Male | 58 | Kabankalan | Pastor |

| Gerardo | Male | 50 | La Castellana | Pastor |

| Lester | Male | 51 | Sagay | Pastor |

| Faye | Female | 52 | San Carlos | Pastora |

| Manuel | Male | 36 | San Carlos | Pastor |

| Antonio | Male | 54 | Silay | Pastor |

| Ramon | Male | 70 | Sipalay | Pastor |

2.4. Data collection

Between November 2020 and January 2021, semi-structured interviews were conducted with REDI religious leaders. Interviews took place in three rounds (November, n = 10; December, n = 6; January, n = 9). This staged approach was more feasible for ICM in the pandemic context and facilitated our combined a priori and ongoing sampling technique (Gentles et al., 2015). Interviews occurred virtually over Skype© and telephone3 with a Filipino research team member, who was also an ICM staff member, and a Canadian research team member present in each conversation. Participants were welcome to communicate in English, Tagalog, Hiligaynon, or Cebuano, and the Filipino team member interpreted as necessary. The presence of the Filipino ICM staff member in interviews was essential, both to facilitate depth of discussion despite language challenges, and to ensure conversations were a trusted, safe, and familiar space for participants, which enabled rich and relational dialogue. In addition, time was used at the start of interviews to establish comfort, trust, and bridge the relational gap due to the virtual setting (Green and Thorogood, 2014; Rapley, 2004). Accordingly, participants were invited to share generally about themselves, their community involvement, and their pandemic experiences. Subsequently, interviews focused broadly on religious leaders’ experiences with REDI during the pandemic. Conversations followed an interview guide (see Appendix A) while remaining flexible for participants and interviewers to engage with content each considered important (Patton, 2015; Rapley, 2004). Research team members debriefed frequently to discuss interview content and study development. The interview guide was adapted as necessary to facilitate discussion and focus on less understood aspects of participant experiences (Green and Thorogood, 2014; Rapley, 2004). All interviews were audio recorded and the length of interviews ranged from 50 to 120 min (average length = 77 min).

2.5. Data analysis

Data were analyzed using an inductive reflexive thematic analysis approach (Braun and Clarke, 2006, 2021) while being broadly informed by sensitization to ethics of care literature. Prior to coding, interviews were transcribed verbatim, and transcripts were checked closely by the interviewers for accuracy. First, a round of inductive open coding was performed to identify initial concepts in the data. Thematic maps were utilized to categorize codes and concepts and determine dominant themes. Second, a round of inductive coding was conducted which clustered around the broad themes identified, again using thematic maps to conceptualize data (see Appendix B). QSR NVivo 12© software was used to code and organize data and retrieve participant quotations. Members of the research team met regularly to discuss observations and thematic development.

3. Results

3.1. Navigating care responsibilities

3.1.1. Motivation to care: “because they're so in need”

Religious leaders practiced care through holding and acting on a sense of responsibility for their community members. Many religious leaders described observing the negative impacts of pandemic restrictions in their communities, including exacerbation of food insecurity, and feeling concerned but unable to help due to lack of personal resources or structural pandemic-related constraints. Thus, once religious leaders became aware of the available aid through REDI, many participants described feeling relieved and motivated to care by becoming a conduit through which these crucial supplies could flow. Accordingly, a predominant motivator cited among religious leaders for engaging in the care work was seeing the need around them and feeling a desire to meet this need. Other motivating factors were also discussed, such as their faith, their connection to ICM, and relationships with their community. In addition, religious leaders often discussed multiple intersecting motivators, such as 54-year-old Antonio from Silay, who stated:

…with the working relationship with REDI Help,4 we can really give assistance [to] people who are really needy in our place…So, as long as we have ICM, we are there, we are willing to support this organization. Because we pastors are located in places, you know, like ours, with a lot of people that are really needy.

Antonio's description highlighted that it was both the connection to ICM, as well as the need of individuals in his local community, that motivated his care work. From excerpts such as this, it was clear that religious leaders held a deep sense of responsibility toward community members and that this was reflected in their motivation to care. Further, the willingness and decision to participate in the REDI program demonstrated how religious leaders translated their sense of responsibility into action by taking the opportunity to meet the needs they identified.

3.1.2. Caring through commitment and creativity: “we are going to make a way”

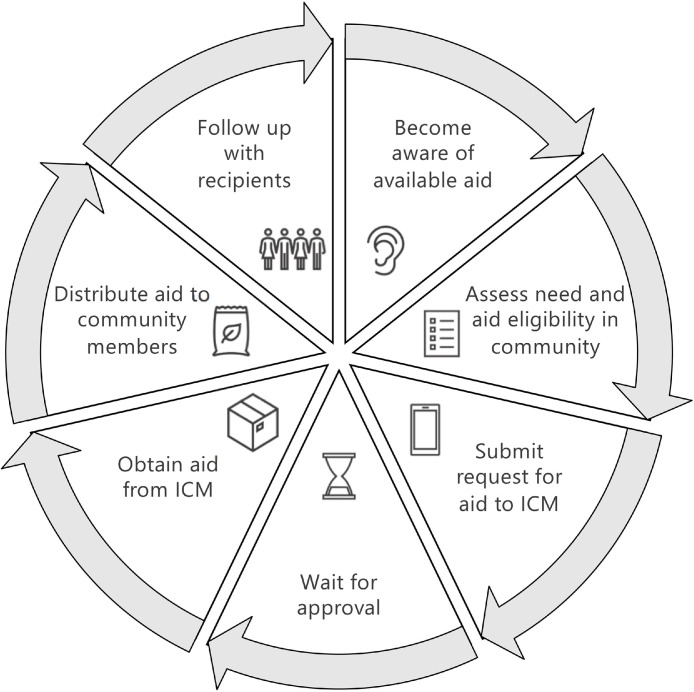

Once religious leaders chose to become involved with REDI, their care practice shifted to entail carrying out, and determining how to carry out, necessary REDI program tasks. In other words, religious leaders agreed to care through a predetermined process. Specifically, interviewees described engaging in several process-oriented care tasks through REDI, including assessing aid eligibility of community members, creating a recipient list, submitting a request to ICM, waiting for approval, obtaining aid, distributing aid, and following up with recipients (see Fig. 2 ). However, since care tasks were broad, and individual and pandemic-related contexts were unique to each religious leader, we noticed that interviewees managed the tasks distinctively. Thus, across participants, care tasks engaged in were largely uniform, but personal strategies, values, and approaches were employed to carry the tasks out.

Fig. 2.

Process-oriented care tasks religious leaders described completing in International Care Ministries’ Rapid Emergencies and Disasters Intervention program.

For example, when determining aid eligibility, 34-year-old Grace from Ilog described that she was “the one deciding, with the coordination of the barangay 5 also,” while 51-year-old Evelyn from Cadiz recounted going through the neighborhoods to survey individuals about the aid: “Okay, so, we go to puroks,6 it's the smaller part of a barangay, and we ask people if they want the manna packs7 …And those that are okay with manna packs…[are] being listed.8 ” Some interviewees also described receiving and following guidance from ICM to identify ultra-poor households, and several interviewees mentioned having knowledge of individuals in need from prior ICM program involvement. A diversity of approaches, such as those exemplified in determining aid eligibility, was observed across care tasks, highlighting the adaptability and innovation with which participants practiced care. Accordingly, interviewees recounted leveraging personal resources, navigating various guidelines, managing encounters with community members, and establishing methods for determining aid eligibility and aid dissemination throughout their care tasks, which further emphasized their personal investment in and dedication to completing the care work.

Additionally, some interviewees shared a rationale for their approach to accomplishing tasks, revealing a sense of morality participants maintained toward their care work. For example, 65-year-old Gloria from Bacolod described how she thought aid ‘should’ be managed:

Because…these people trusted me. I am a steward of this. So, I have to be handling [it] properly…Though it is a dole out, we should be very careful to implement [it]. We will not just give this any way, this is for free…Though this is free, we should be handling this properly.

From excerpts such as this, it was clear that how they accomplished tasks was important for some participants. That is, practicing care went beyond merely performing tasks and involved discerning how to do them ‘appropriately’, whether according to personally-held values and principles, instructions communicated by ICM, or regulations set by government administration. Notably, a few participants described cases of non-adherence to pandemic protocols; overall, however, participants shared striving to meet standards, whether internally or externally derived. This sentiment was echoed regarding various elements of REDI involvement, demonstrating the moral integrity connected to how these individuals practiced care. Thus, we observed that religious leaders drew on a depth of commitment, personal investment, creativity, and integrity when practicing their care work.

3.2. Caring alongside others

3.2.1. Initiating care work: “I called them and shared with them”

Another prominent way religious leaders practiced care through REDI was in connection to others. That is, it was evident that religious leaders did not carry out care tasks in isolation but rather mobilized relational support to complete the care work. A wide range of relationships were referenced by interviewees in connection to their experiences, including ICM staff, government officials, their faith community, and other community members. Accordingly, all interviewees drew support from personal relations, and many interviewees offered support to other religious leaders, to accomplish care tasks.

Connecting to the REDI program initially was one context in which relational support with care tasks was discussed. Thus, many interviewees described instances of information sharing or aid application support. For example, 51-year-old Evelyn from Cadiz explained that “[registration] was hard because it was online…but I called [an ICM staff member] and he guided me on how to [register] and it went well.” Many other interviewees also indicated receiving helpful assistance, instruction, or communication from ICM staff. Additionally, several interviewees described reaching out to other religious leaders to share information or support them in applying for aid. Initiating the care work in this collective manner highlighted religious leaders’ relational approach to care.

3.2.2. Managing care resources: “we distribute together to the community”

Aid management was a context in which all interviewees discussed relational support with care tasks. Predominantly, support with obtaining and distributing aid was discussed, but assistance with storing aid, listing recipients, and following up with recipients was also cited. For example, 47-year-old Dinah from Escalante, like many religious leaders, described the support she received from community members in transporting aid:

So, the goods were just carried by motorcycle to the port and then to the pump boat and from the pump boat, our members, when we arrived to the community, they're the ones who got the boxes…So, that's when the manna packs were distributed…The rent of the pump boat is usually around 200 pesos,9 but [the] pump boat we used that day is from a member and he is also one of the recipients…So, we saved some rent on that.

In contrast, 36-year-old Manuel from San Carlos explained that he organized, facilitated, and funded transportation of aid for several other religious leaders and reached out to his Local Government Unit (LGU) to do so. Notably, many interviewees mentioned receiving transportation support from ICM staff or their LGU. Overall, a few interviewees mentioned the mutual support with care tasks experienced between religious leaders, which further underscored their relational practice of care.

3.2.3. Caring through pre-existing connections: “because we are already friends”

Another context in which religious leaders cited relational support was with navigating pandemic restrictions throughout their care tasks. Importantly, some interviewees described how pre-existing relationships with government officials proved useful. For example, 52-year-old Faye from San Carlos explained that having a church member in the LGU helped her gain permission to distribute the food aid:

…before we distributed it, we should see to it that the LGU know[s] us…So, we ask permission from them in order that we can go there in that area…We are so blessed because one of our [church] members is already in the LGU. So, we write a letter for the LGU to approve that we are already permitted.

Similarly, having established roles as frontline workers or prior involvement in the LGU were mentioned as being helpful to navigate pandemic restrictions, especially with crossing checkpoints. Additionally, some interviewees described government officials handling aid distribution when public health measures prevented religious leaders from distributing aid. Notably, interviewees recounted the supportive role of government officials even when a pre-existing relationship was not mentioned.

Collective effort was observed across participants and throughout REDI tasks. Thus, it was evident that religious leaders’ sphere of care extended beyond their personal context to include other individuals. That is, as they reached out to elicit or extend support with care tasks, they opened their care work to invite and enable the participation of others. Accordingly, we observed that care was practiced within and through religious leaders’ relationships as a collective and dynamic network of care.

3.3. Engaging holistically with care

3.3.1. Navigating care challenges: “sometimes it hurts my heart”

A third way religious leaders practiced care was by engaging multi-dimensionally with the care work. In one sense, we observed that all interviewees encountered challenging circumstances or emotions during their care tasks. For instance, some interviewees mentioned the difficulty of maneuvering heavy boxes of aid, feeling physically tired during or after involvement, or participating despite health concerns. Other interviewees discussed the challenge of navigating pandemic measures, or of organizing aid transportation across complex terrain or long durations. A few interviewees described observing that other religious leaders were unable to care through REDI because the barriers they faced were too great to overcome (e.g., physical ability, application process, pandemic restrictions). Indeed, it was evident that social support with care tasks was essential as the challenges involved with completing the care work were not feasible to manage alone.

Additionally, several interviewees described care difficulties related to resource limitations. For example, 52-year-old Alejandro from Bacolod shared the challenge of facing community members with limited aid in a time of such great need:

…sometimes it hurts my heart to think of others thinking of us not extending help to all of them…because we are also limited…especially in one community where all of them, actually, are in need during that time. So, how I wish all of them could receive, but we have no choice.

Similarly, other interviewees mentioned the challenge of providing an explanation to individuals who were unable to receive aid due to supply constraints, including 55-year-old Arnold from Bago who was brought to tears when explaining, “We cannot please you or give you anything.” In contrast, a few interviewees described community members who demonstrated a lack of desire for the aid, which was an equally challenging care experience for some participants.

Accordingly, caring in this context was not always straightforward, but involved complicated and even uncomfortable situations and emotions for individuals to navigate. That religious leaders continued with care tasks in the face of such difficulties demonstrated the perseverance with which they practiced care.

3.3.2. Positive framings of care: “I cannot describe my feelings; I was so very happy”

Overall, religious leaders were expressly positive in their accounts of the care work, which highlighted a positive dimension to their experience of care and demonstrated that they practiced care with a degree of optimism. Describing the program and food aid as “a blessing”, “a great help”, and as bringing happiness to community members and religious leaders was echoed across participants. Similarly, all interviewees shared the gratitude they felt or saw during their care work. In addition, nearly all interviewees identified positive outcomes from the care work and elements of care tasks that were managed with ease. Importantly, an optimistic perspective of the care work was exemplified as all interviewees expressed willingness to continue participating in the REDI program, whether presently or in the future.

Additionally, some interviewees deemphasized the caring difficulties they experienced, which further demonstrated their optimism. For example, 45-year-old Nelson from Cauayan commented that they “don't worry so much about the hardships and struggles.” Other interviewees highlighted positive elements over the difficulties or underscored their faith as a source of strength to manage care challenges. 54-year-old Francisco from Kabankalan shared both sentiments when he described:

…in the community, if that place is not reachable by vehicle, you have to climb the mountains, all while carrying the manna packs, requesting other families and workers to help carry the materials going to a certain place…the rains, the heat of the sun…but everybody's happy because we're doing [it] for the Lord.

Therefore, religious leaders’ especially positive descriptions of the care work, even given hardships, demonstrated the deep value they held for the care work and the optimism with which they practiced care.

3.3.3. Caring through emotional connection: “[we] give them a word of encouragement”

Religious leaders also practiced care multi-dimensionally by providing emotional care, in addition to physical support, through food aid delivery. Several interviewees described the negative emotional impact of the pandemic on their communities. With this knowledge, and their position as local spiritual leaders, we observed that nearly all interviewees offered some form of emotional care to community members.

Spiritual support was a predominant type of emotional care provided by religious leaders. Most interviewees offered prayer or spiritual instruction during their care tasks, such as 44-year-old Theo from Don Salvador Benedicto, who described of his experience with aid distribution, “They are smiling, and sometimes we pray for them…and encourag[e] them.” Indeed, many religious leaders considered their care work with REDI to be part of their ministerial roles. Some interviewees explicitly articulated the value of providing a “balance” of material and spiritual support. This was meant both to emphasize the importance of supplementing material aid with spiritual care, and to explain that REDI offered them a chance to complement their typically spiritual roles by caring physically in the community through delivery of material aid.

Additionally, a few interviewees described providing emotional care through counseling. For example, 65-year-old Gloria from Bacolod explained that her counsel to aid recipients extended beyond REDI care tasks as her “phone [was] 24 hours ready for all their calls”. Several interviewees also described offering encouragement, either to recipients of aid, other religious leaders, or community members who were unable to receive aid due to supply constraints. Thus, we observed that some religious leaders cared by aiming to address emotional needs even when they were unable to address physical needs.

Accordingly, we observed that religious leaders practiced care by participating wholly in the work. They involved their entire, multi-dimensional selves in the care work and connected with the entire, multi-dimensional selves of others. Thus, it was evident that religious leaders’ sphere of care extended beyond physical needs to include emotional and spiritual aspects and that their holistic engagement with care included managing a range of circumstances and emotions with optimism.

4. Discussion

4.1. Caring in context

The findings of our study revealed that religious leaders practiced care by navigating care responsibilities, caring alongside others, and engaging holistically with the care work. Our study contributes an empirical example of how these care components have been realized when grounded in a particular caring context. In doing so, these findings offer new insights into our conceptualization of care practice. A central tenet in care ethics is that all care work is contextual (Engster and Hamington, 2015; Gilligan, 1982; Tronto, 1993, 2013). Accordingly, we identified several contextual factors that shaped the care work in our research. While geographic and demographic characteristics diverged between participants, shared contextual factors “emplace[d]” (Raghuram, 2016, p.512) the care work within a humanitarian setting in the Philippines, in connection to an NGO and the REDI program, and as practiced by religious leaders. Thus, the study builds on appeals by care scholars to broaden our examination of care situatedness (Bartos, 2019; Hanrahan and Smith, 2020; Kallio, 2020; Raghuram, 2016), and also strengthens its contribution as a study that brings an analysis of multi-dimensional and 'emplaced' care work to the existing humanitarian and disaster response scholarship.

The positionality of participants as religious leaders fundamentally impacted the care work. Notably, participant narratives indicated that the social and geographical (e.g., physical locality) embeddedness of religious leaders both provided grounds for the care work and enabled the care work. This finding is consistent with research in other humanitarian and health promotion contexts that has found religious leaders to be key stakeholders due to their connectedness (Ergul, 2020; Lau et al., 2020; Wijesinghe et al., 2022). In addition, religious leaders exhibited a strong orientation to care. This orientation was evidenced through their deep motivation to engage with the work and commitment to carry out tasks despite the personal investment required and challenges encountered. It could be that their positionality as religious leaders enhanced their orientation to care as has been discussed elsewhere (Greene et al., 2020; Jackson-Jordan, 2013). Further, that participants offered holistic care – namely, emotional and spiritual support alongside material aid – reflects what has been previously discussed on the humanitarian efforts of religious leaders (Arruda, 2020; del Castillo et al., 2020; Wijesinghe et al., 2022; Yoosefi Lebni et al., 2021) and aligns with their pre-existing roles as spiritual leaders in the community. This orientation to care among religious leaders also extends beyond the COVID-19 pandemic to a broader temporal and contextual scope, as evidenced by a long history of religious leaders' involvement in community-based humanitarian and disaster response (Ager et al., 2014, 2015; Sheikhi et al., 2021; Wilkinson, 2018; World Humanitarian Summit, 2016). Accordingly, findings from our study highlight the increased reliance on and provision of care by faith-based actors in a pandemic context, which underscores the importance of care provided by religious actors in humanitarian settings. This evidence emphasizes the need for increased understanding and support of this type of care to ensure caring crisis responses moving forward.

The humanitarian setting and partnership with an NGO also profoundly influenced the care work. Importantly, these factors set parameters to the care in terms of the type of needs addressed, the type of care possible, the ways in which the care was to be completed, and the extent of the care. In other words, religious leaders addressed local food needs since food needs became pressing in the pandemic context and because food support was the type of assistance available through ICM. Further, to meet the food needs they identified, religious leaders were required to follow the procedures laid out by ICM. Finally, the extent of food needs met by religious leaders was characterized by the amount of support available through ICM. Accordingly, all aspects of the care work were defined, to an extent, by the crisis environment and collaboration with ICM. We have termed this form of care as ‘caring through a predetermined process’ since partnership with an NGO meant that the care work followed a specific and delineated process. Given studies that examine ethics of care within a civil society organization are few (Barnes, 2020; Collins, 2015; Dodd et al., 2022), our research provides a starting point for further examination and conceptualization of care work that follows stipulated process-oriented care tasks.

Locatedness in the Philippines also necessarily shaped the care work. A widely held concept in the Philippines is bayanihan, a sentiment which signifies communal effort for the common good. Originally used in the context of collective agriculture, the term has since gained applicability throughout Filipino society, having particular importance during challenging times such as disasters and emergencies (Aruta et al., 2022; Bankoff, 2020; Boquet, 2017; Eadie and Su, 2018). In the COVID-19 pandemic, use of the term proliferated, both to refer to a spirit of cooperation in navigating disease prevention, public health measures, and resulting impacts on livelihoods and food security (Bagayas, 2020), and as President Duterte enacted the ‘Bayanihan to Heal as One Act’ (Republic Act No. 11,469, March 2020) which enabled him greater authority over restriction implementation and enhanced provision of government support (Bankoff, 2020; Republic of the Philippines Official Gazette, 2020b). Accordingly, bayanihan has been contentious during the pandemic and other emergencies since political authorities employ the term to promote compliance among residents, and the sentiment has even been considered a myth (Bankoff, 2020; Eadie and Su, 2018; Su and Tanyag, 2020).

In this environment, a clear finding of our study was that participants did not complete the care work in isolation but alongside their social relations as a collective and dynamic network of care. It could be that the Filipino concept of bayanihan contributed to religious leaders’ engagement with the care work in this communal manner and perhaps even their motivation to participate with REDI overall. Notably, bayanihan was not mentioned by religious leaders; however, during preliminary research consultations, one Filipino ICM staff member used the term in their description of observed religious leader efforts. The evident interconnectedness between participants and their personal relations is consistent with the literature on Filipino society and previous research showing the presence of strong bonding social capital (e.g., between family members, friends, neighbors) among Filipinos (Abad, 2005; Eadie and Su, 2018; Morais, 1981; Turgo, 2016). Irrespective of whether bayanihan was an explicit motivating factor for religious leaders, their collective approach furthers a non-dyadic view of care (i.e., as not occurring between two people) (Aslanian, 2020; Tronto, 1993) in that religious leaders provided care at the community rather than individual level and did so alongside others.

Taken together, this study's insights into the multi-dimensional and nuanced care practice of religious leaders point to the opportunity present in collaborating with local religious leaders in humanitarian response; the approaches that may be used by individuals when doing so; and the supports that may be needed by individuals in this process. Additionally, the care experiences of religious leaders in this study contribute to further expanding and complicating our understanding of care through the use of care ethics, a necessary endeavor to ensure that diverse positionalities, practices, approaches, and experiences with care are recognized and valued.

4.2. Limitations and future research

This study was conducted through one of ICM's 12 regional bases. Accordingly, participant experiences may not be reflective of religious leaders connected to other regional bases as public health measures and restrictions were diverse across regions and throughout the pandemic. Additionally, our remote approach prevented in-person interviews which may have impacted rapport development and, thus, the extent and quality of sharing. To mitigate this challenge, research consultations were held with ICM staff members involved with REDI and space was provided for participants to share openly about themselves to facilitate comfort and connection between interviewees and interviewers. Further, the presence of a research team member who was a Filipino ICM staff member during interviews may have prompted participants to share more favorable experiences. To mitigate this potential impact, interviewers emphasized to participants that their identity would remain confidential and that what they shared would not impact their relationship with ICM.

Further research is needed to explore care work conducted in partnership with NGOs, both faith-based and secular, to illuminate how individuals manage prescribed care tasks. Future studies are also needed to examine the care motivations and efforts of local religious leaders from diverse faith traditions in crisis environments through an ethics of care lens in order to expand visibility of the role of religious leaders in providing care in these contexts.

5. Conclusion

Our study described how the care components of responsibility, relationality, and emotion unfolded in the context of Filipino religious leaders meeting local food needs through partnership with an NGO during the COVID-19 pandemic. In doing so, our study offers an in-depth examination of empirical findings related to an under-explored form of care work within ethics of care, and engages a theoretical framework less common within the existing scholarship on religious leaders' work within humanitarian and disaster response. Our research highlighted the integral role that social and geographical embeddedness played for religious leaders in that it both enabled and enhanced their efforts. In addition, religious leaders practiced care holistically by offering material, emotional, and spiritual support. Further, religious leaders demonstrated a strong orientation to care as they expressed deep motivation to meet community needs and displayed commitment and creativity to complete care tasks by leveraging personal, material, and social resources, in addition to navigating a challenging and dynamic pandemic context with optimism. Overall, our study builds on an invitation within care ethics to explore care as situated and practiced in diverse settings, and also expands visibility of the humanitarian response of local religious leaders during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Funding

This work was supported by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (892–2021–1004). Further funding was provided to Shoshannah J. Speers through scholarships from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada, the University of Waterloo, and the Global Health Policy and Innovation Research Centre (University of Waterloo). These funding sources had no involvement in the study design; collection, analysis, or interpretation of data; writing of the report; or decision to submit the article for publication.

Ethics

This study was approved by the University of Waterloo Human Research Ethics Committee in October 2020 (ORE #42565).

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests:

Lincoln L. Lau reports financial support was provided by International Care Ministries. Danilo Servano Jr. reports financial support was provided by International Care Ministries. Daryn J. Go reports financial support was provided by International Care Ministries. All other authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to participants for sharing their stories and to International Care Ministries for their support with this project.

Footnotes

List of Abbreviations: COVID-19: Coronavirus Disease 2019; ICM: International Care Ministries; LGU: Local Government Unit; NGO: Non-Governmental Organization; REDI: Rapid Emergencies and Disasters Intervention.

ICM defines ultra-poor as households that live on less than US $0.50 per person per day (International Care Ministries, 2021).

Skype© was used as the platform for interviews since it facilitated a multimodal connection. A three-way call was enabled whereby the Filipino and Canadian researchers communicated via videoconference while conversing with participants by telephone. This approach enhanced accessibility for participants (most of whom did not have Internet access), enriched quality of conversation, and supported adherence to pandemic safety measures.

The term REDI Help refers to ICM's REDI program as used during the COVID-19 pandemic.

A barangay is the smallest political unit in the Philippines, akin to a district or village (Matthies, 2017). The term is used both in reference to the administration and the geographical location.

A purok is a subdivision of the barangay, akin to a sub-village (Matthies, 2017).

The term manna pack refers to the fortified rice pack ICM distributed through REDI during the pandemic.

Community members had varying levels of familiarity and preference toward the aid which impacted interest in the aid.

200 Philippine pesos is equivalent to approximately four US dollars as of May 2022.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.wss.2023.100154.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- Abad R.G. Social capital in the Philippines: results from a national survey. Philipp. Sociol. Rev. 2005;53:1–57. [Google Scholar]

- Adedini S.A., Babalola S., Ibeawuchi C., Omotoso O., Akiode A., Odeku M. Role of religious leaders in promoting contraceptive use in Nigeria: evidence from the Nigerian Urban Reproductive Health Initiative. Glob. Health Sci. Pract. 2018;6(3):500–514. doi: 10.9745/GHSP-D-18-00135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ager J., Abebe B., Ager A. Mental health and psychosocial support in humanitarian emergencies in Africa: challenges and opportunities for engaging with the faith sector. Rev. Faith Int. Aff. 2014;12(1):72–83. doi: 10.1080/15570274.2013.876729. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ager J., Fiddian-Qasmiyeh E., Ager A. Local faith communities and the promotion of resilience in contexts of humanitarian crisis. J. Refug. Stud. 2015;28(2):202–221. doi: 10.1093/jrs/fev001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Angeles-Agdeppa I., Javier C.A., Duante C.A., Maniego M.L.V. Impacts of COVID-19 pandemic on household food security and access to social protection programs in the Philippines: findings from a telephone Rapid Nutrition Assessment Survey. Food Nutr. Bull. 2022;43(2):213–231. doi: 10.1177/03795721221078363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arruda G.A. The impact of the pandemic on the conception of poverty, discourse, and praxis of Christian religious communities in Brazil from the perspective of their local leaders. Int. J. Latin Am. Religi. 2020;4(2):380–401. doi: 10.1007/s41603-020-00122-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aruta J.J.B.R., Crisostomo K.A., Canlas N.F., Almazan J.U., Peñaranda G. Measurement and community antecedents of positive mental health among the survivors of typhoons Vamco and Goni during the COVID-19 crisis in the Philippines. Int. J. Disast. Risk Reduct. 2022;72 doi: 10.1016/j.ijdrr.2022.102853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aslanian T.K. Every rose has its thorns: domesticity and care beyond the dyad in ECEC. Glob. Stud. Childh. 2020;10(4):327–338. doi: 10.1177/2043610620978508. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bagayas, S. (2020). Pandemic Can't Stop bayanihan: How Filipinos Took Action On Urgent Issues in 2020. Rappler. https://www.rappler.com/moveph/times-filipinos-acted-issues-yearend-2020/.

- Bankoff G. Old ways and new fears: bayanihan and COVID-19. Philippine Stud.: Histor. Ethnograph. Viewp. 2020;68(3–4):467–475. doi: 10.1353/phs.2020.0029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes M. Community care: the ethics of care in a residential community. Ethic. Soc. Welf. 2020;14(2):140–155. doi: 10.1080/17496535.2019.1652334. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bartos A.E. The uncomfortable politics of care and conflict: exploring nontraditional caring agencies. Geoforum. 2018;88:66–73. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2017.11.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bartos A.E. Introduction: stretching the boundaries of care. Gend. Place Cult. 2019;26(6):767–777. doi: 10.1080/0966369X.2019.1635999. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boddy C.R. Sample size for qualitative research. Qualit. Mark. Res. 2016;19(4):426–432. doi: 10.1108/QMR-06-2016-0053. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bond S., Barth J. Care-full and just: making a difference through climate change adaptation. Cities. 2020;102 doi: 10.1016/j.cities.2020.102734. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boquet, Y. (2017). The Philippine Archipelago. Springer International Publishing. 10.1007/978-3-319-51926-5. [DOI]

- Braun V., Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Braun V., Clarke V. One size fits all? What counts as quality practice in (reflexive) thematic analysis? Qual. Res. Psychol. 2021;18(3):328–352. doi: 10.1080/14780887.2020.1769238. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Calleja, J.P. (2020). Philippine Govt Praises Church Pandemic Efforts. Union of Catholic Asian News. https://www.ucanews.com/news/philippine-govt-praises-church-pandemic-efforts/87859.

- Cohen-Dar M., Obeid S. Islamic religious leaders in Israel as social agents for change on health-related issues. J. Relig. Health. 2017;56(6):2285–2296. doi: 10.1007/s10943-017-0409-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins K.J. A critical ethic of care for the homeless applied to an organisation in Cape Town. Soc. Work. 2015;51(3):434–455. doi: 10.15270/51-3-457. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Corpuz J.C.G. COVID-19: spiritual interventions for the living and the dead. J. Public Health (Oxf) 2021;43(2):e244–e245. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdaa167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- del Castillo F.A., Biana H.T., Joaquin J.J.B. ChurchInAction: the role of religious interventions in times of COVID-19. J. Public Health (Bangkok) 2020;42(3):633–634. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdaa086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodd W., Kipp A., Bustos M., McNeil A., Little M., Lau L.L. Humanitarian food security interventions during the COVID-19 pandemic in low- and middle-income countries: A review of actions among non-state actors. Nutrients. 2021;13(7):2333. doi: 10.3390/nu12072333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodd W., Brubacher L.J., Kipp A., Wyngaarden S., Haldane V., Ferrolino H., Wilson K., Servano D., Jr., Lau L.L., Wei X. Navigating fear and care: The lived experiences of community-based health actors in the Philippines during the COVID-19 pandemic. Soc. Sci. Med. 2022;308:115222. doi: 10.1010/j.soscsimed.2022.115222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodd W., Brubacher L.J., Speers S., Servano D., Jr., Go D.J., Lau L.L. The contributions of religious leaders in addressing food insecurity during the COVID-19 pandemic in the Philippines: A realist evaluation of the Rapid Emergencies and Disasters Intervention (REDI) Int. J. Disast. Risk Reduct. 2023;86:103545. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdrr.2023.103545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eadie P., Su Y. Post-disaster social capital: trust, equity, bayanihan and Typhoon Yolanda. Disast. Prev. Manag. 2018;27(3):334–345. doi: 10.1108/DPM-02-2018-0060. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Engster, D., & Hamington, M. (2015). Introduction. In D. Engster & M. Hamington (Eds.), Care Ethics and Political Theory (pp. 1–17). Oxford University Press. 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198716341.003.0001. [DOI]

- Ergul, H. (2020). The Role of Faith in the Humanitarian response: Strengthening community Participation and Engagement Through Religious Leaders in Rohingya camps in Cox's Bazar, Bangladesh. UNICEF. https://www.unicef.org/bangladesh/media/4436/file/CaseStudy4_CXBC4D.pdf.pdf.

- Fisher, B., & Tronto, J. (1990). Toward a feminist theory of caring. In E. K. Abel & M. K. Nelson (Eds.), Circles of care: Work and Identity in Women's Lives (pp. 35–62). State University of New York Press.

- Frei-Landau R. When the going gets tough, the tough get—Creative”: Israeli Jewish religious leaders find religiously innovative ways to preserve community members’ sense of belonging and resilience during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psycholog. Trauma: Theor. Res. Pract. Policy. 2020;12(S1):S258–S260. doi: 10.1037/tra0000822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gary M., Berlinger N. Interdependent citizens: the ethics of care in pandemic recovery. Hast. Cent. Rep. 2020;50(3):56–58. doi: 10.1002/hast.1134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentles S.J., Charles C., Ploeg J., McKibbon K.A. Sampling in qualitative research: insights from an overview of the methods literature. Qualit. Rep. 2015;20(11):1772–1789. doi: 10.46743/2160-3715/2015.2373. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gilligan, C. (1982). In a Different voice: Psychological theory and Women's Development. Harvard University Press.

- Giraud E. Urban food autonomy: the flourishing of an ethics of care for sustainability. Humanities. 2021;10(1):48. doi: 10.3390/h10010048. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Green, J., & Thorogood, N. (2014). Qualitative Methods For Health Research (3rd ed.). Sage.

- Greene T., Bloomfield M.A.P., Billings J. Psychological trauma and moral injury in religious leaders during COVID-19. Psycholog. Trauma: Theor., Res. Pract. Policy. 2020;12(S1):S143–S145. doi: 10.1037/tra0000641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guadalquiver, N. (2021). Bacolod Religious Leaders Offer Prayers For Healing from COVID-19. Philippine News Agency. https://www.pna.gov.ph/articles/1158045.

- Hamington, M., & Sander-Staudt, M. (Eds.). (2011). Applying Care Ethics to Business. Springer.

- Hanrahan K.B., Smith C.E. Interstices of care: re-imagining the geographies of care. Area. 2020;52(2):230–234. doi: 10.1111/area.12502. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hanrahan K.B. Living care-fully: the potential for an ethics of care in livelihoods approaches. World Dev. 2015;72:381–393. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2015.03.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hapal K. The Philippines’ COVID-19 response: securitising the pandemic and disciplining the pasaway. J. Curr. Southeast Asian Aff. 2021;40(2):224–244. doi: 10.1177/1868103421994261. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Harr C.R., Yancey G.I. Social work collaboration with faith leaders and faith groups serving families in rural areas. J. Religi. Spirit. Soc. Work: Soc. Though. 2014;33(2):148–162. doi: 10.1080/15426432.2014.900373. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hilario, E.M. (2020). Church in the Philippines responds to COVID-19. Licas News. https://www.licas.news/2020/03/24/church-in-the-philippines-responds-to-covid-19/.

- International Care Ministries. (2021). International Care Ministries: 2021-2022 Annual Report. https://indd.adobe.com/view/d019732f-3551-4df9-a956-8f5e3a296d7e.

- Jackson-Jordan E.A. Clergy burnout and resilience: a review of the literature. J. Pastor. Care Counsel. 2013;67(1):1–5. doi: 10.1177/154230501306700103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kallio K.P. Care as a many-splendoured topology (including prickles) Area. 2020;52(2):269–272. doi: 10.1111/area.12490. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kittay E.F. The ethics of care, dependence, and disability. Ratio Juris. 2011;24(1):49–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9337.2010.00473.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Langford R., Richardson B., Albanese P., Bezanson K., Prentice S., White J. Caring about care: reasserting care as integral to early childhood education and care practice, politics and policies in Canada. Glob. Stud. Childh. 2017;7(4):311–322. doi: 10.1177/2043610617747978. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lau L.L., Dodd W., Qu H.L., Cole D.C. Exploring trust in religious leaders and institutions as a mechanism for improving retention in child malnutrition interventions in the Philippines: A retrospective cohort study. BMJ Open. 2020;10(9) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-036091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Locke C. Do male migrants ‘care’? How migration is reshaping the gender ethics of care. Ethics Soc. Welf. 2017;11(3):277–295. doi: 10.1080/17496535.2017.1300305. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mak H.W., Fancourt D. Predictors of engaging in voluntary work during the COVID-19 pandemic: analyses of data from 31,890 adults in the UK. Persp. Public Health. 2022;142(5):287–296. doi: 10.1177/1757913921994146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malterud K., Siersma V.D., Guassora A.D. Sample size in qualitative interview studies: guided by information power. Qual. Health Res. 2016;26(13):1753–1760. doi: 10.1177/1049732315617444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marston C., Renedo A., Miles S. Community participation is crucial in a pandemic. Lancet North Am. Ed. 2020;395(10238):1676–1678. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31054-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthies A. Community-based disaster risk management in the Philippines: achievements and challenges of the purok system. Austr. J. South-East Asian Stud. 2017;10(1):101–108. doi: 10.14764/10.ASEAS-2017.1-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mbivnjo E.L., Kisangala E., Kanyike A.M., Kimbugwe D., Dennis T.O., Nabukeera J. Web-based COVID-19 risk communication by religious authorities in Uganda: a critical review. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2021;(63):40. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2021.40.63.27550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morais R.J. Friendship in the rural Philippines. Philipp Stud. 1981;29(1):66–76. [Google Scholar]

- Ofreneo M.A., Canoy N., Martinez L.M., Fortin P., Mendoza M., Yusingco M.P., Aquino M.G. Remembering love: memory work of orphaned children in the Philippine drug war. J. Soc. Work. 2022;22(1):46–67. doi: 10.1177/1468017320972919. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ong M.M., Ong R.M., Reyes G.K., Sumpaico-Tanchanco L.B. Addressing the COVID-19 nutrition crisis in vulnerable communities: applying a primary care perspective. J. Prim. Care Commun. Health. 2020;11:1–4. doi: 10.1177/2150132720946951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osei-Tutu A., Affram A.A., Mensah-Sarbah C., Dzokoto V.A., Adams G. The impact of COVID-19 and religious restrictions on the well-being of Ghanaian Christians: the perspectives of religious leaders. J. Relig. Health. 2021;60(4):2232–2249. doi: 10.1007/s10943-021-01285-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oyo-Ita A., Bosch-Capblanch X., Ross A., Oku A., Esu E., Ameh S., Oduwole O., Arikpo D., Meremikwu M. Effects of engaging communities in decision-making and action through traditional and religious leaders on vaccination coverage in Cross River State, Nigeria: a cluster-randomised control trial. PLoS One. 2021;16(4) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0248236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton, M.Q. (1990). Designing qualitative studies. In M. Q. Patton (Ed.), Qualitative Evaluation and Research Methods (2nd ed., pp. 169–186). Sage.

- Patton, M.Q. (2015). Qualitative Research and Evaluation methods: Integrating theory and Practice (4th ed.). Sage.

- Philippine Department of Agriculture. (2020). DA to Set in Motion ALPAS COVID-19 to Ease the Threat of Hunger. https://www.da.gov.ph/da-to-set-in-motion-alpas-covid-19-to-ease-the-threat-of-hunger/.

- Philippine Statistics Authority . 2019 Philippines in Figures. 2019. https://psa.gov.ph/sites/default/files/PIF2019_revised.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Pols J. Towards an empirical ethics in care: relations with technologies in health care. Med. Health Care Philosoph. 2015;18(1):81–90. doi: 10.1007/s11019-014-9582-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell C.L. Working together for global health goals: the United States Agency for International Development and faith-based organizations. Christ. J. Glob. Health. 2014;1(2):63–70. doi: 10.15566/cjgh.v1i2.36. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Raghuram P. Locating care ethics beyond the Global North. ACME: Int. J. Criti. Geograph. 2016;15(3):511–533. [Google Scholar]

- Rapley, T. (2004). Interviews. In C. Seale, G. Gobo, J. F. Gubrium, & D. Silverman (Eds.), Qualitative Research Practice (pp. 15–33). Sage.

- Razavi S. The political and social economy of care in a development context: conceptual issues, research questions and policy options. Unit. Nat. Res. Instit. Soc. Develop.: Gend. Develop. Program. Paper. 2007;(No. 3; June 2007) https://cdn.unrisd.org/assets/library/papers/pdf-files/razavi-paper.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Republic of the Philippines Official Gazette. (2020a). Executive Order No. 112. https://www.officialgazette.gov.ph/downloads/2020/04apr/2020030-EO-112-RRD.pdf.

- Republic of the Philippines Official Gazette. (2020b). Republic Act No. 11469. https://www.officialgazette.gov.ph/downloads/2020/03mar/20200324-RA-11469-RRD.pdf.

- Rivera-Hernandez M. The Role of religious leaders in health promotion for older Mexicans with diabetes. J. Relig. Health. 2015;54(1):303–315. doi: 10.1007/s10943-014-9829-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy S., Ayalon L. Goodness and kindness”: long-distance caregiving through volunteers during the COVID-19 lockdown in India. J. Gerontol., Ser. B: Psycholog. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2021;76(7):E281–E289. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbaa187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheikhi R.A., Seyedin H., Qanizadeh G., Jahangiri K. Role of religious institutions in disaster risk management: a systematic review. Disast. Med. Public Health Prep. 2021;15(2):239–254. doi: 10.1017/dmp.2019.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su Y., Tanyag M. Globalising myths of survival: post-disaster households after Typhoon Haiyan. Gend., Place Cult.: A J. Femin. Geogr. 2020;27(11):1513–1535. doi: 10.1080/0966369X.2019.1635997. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Trautwein S., Liberatore F., Lindenmeier J., von Schnurbein G. Satisfaction with informal volunteering during the COVID-19 crisis: an empirical study considering a Swiss online volunteering platform. Nonprofit Volunt Sect Q. 2020;49(6):1142–1151. doi: 10.1177/0899764020964595. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tronto, J.C. (1993). Moral boundaries: A political Argument For an Ethic of Care. Routledge. 10.4324/9781003070672. [DOI]

- Tronto, J.C. (2013). Caring democracy: Markets, equality, and Justice. New York University Press.

- Turgo N. The kinship of everyday need: relatedness and survival in a Philippine fishing community. South East Asia Res. 2016;24(1):61–75. doi: 10.5367/sear.2016.0291. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tuyisenge G., Crooks V.A., Berry N.S. Using an ethics of care lens to understand the place of community health workers in Rwanda's maternal healthcare system. Soc. Sci. Med. 2020;264 doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wijesinghe M.S.D., Ariyaratne V.S., Gunawardana B.M.I., Rajapaksha R.M.N.U., Weerasinghe W.M.P.C., Gomez P., Chandraratna S., Suveendran T., Karunapema R.P.P. Role of religious leaders in COVID‑19 prevention: a community‑level prevention model in Sri Lanka. J. Relig. Health. 2022;61(1):687–702. doi: 10.1007/s10943-021-01463-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson O. Faith can come in, but not religion”: secularity and its effects on the disaster response to Typhoon Haiyan. Disasters. 2018;42(3):459–474. doi: 10.1111/disa.12258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2020). Practical considerations and recommendations for religious leaders and faith-based communities in the context of COVID-19: interim guidance. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/331707/WHO-2019-nCoV-Religious_Leaders-2020.1-eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

- World Humanitarian Summit. (2016). Charter for Faith-Based Humanitarian Action.https://agendaforhumanity.org/initiatives/4012.html#:~:text=The%20Charter%20for%20Faith%2DBased,traditions%20and%20different%20geographical%20regions.

- Yoosefi Lebni J., Ziapour A., Mehedi N., Irandoost S.F. The role of clerics in confronting the COVID-19 crisis in Iran. J. Relig. Health. 2021;60(4):2387–2394. doi: 10.1007/s10943-021-01295-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.