Abstract

Background

Patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and poor liver function lack effective systemic therapies. Low‐energy electromagnetic fields (EMFs) can influence cell biological processes via non‐thermal effects and may represent a new treatment option.

Methods

This single‐site feasibility trial enrolled patients with advanced HCC, Child‐Pugh A and B, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group 0–2. Patients underwent 90‐min amplitude‐modulated EMF exposure procedures every 2–4 weeks, using the AutEMdev (Autem Therapeutics). Patients could also receive standard care. The primary endpoints were safety and the identification of hemodynamic variability patterns. Exploratory endpoints included health‐related quality of life (HRQoL), overall survival (OS). and objective response rate (ORR) using RECIST v1.1.

Results

Sixty‐six patients with advanced HCC received 539 AutEMdev procedures (median follow‐up, 30 months). No serious adverse events occurred during procedures. Self‐limiting grade 1 somnolence occurred in 78.7% of patients. Hemodynamic variability during EMF exposure was associated with specific amplitude‐modulation frequencies. HRQoL was maintained or improved among patients remaining on treatment. Median OS was 11.3 months (95% confidence interval [CI]: 6.0, 16.6) overall (16.0 months [95% CI: 4.4, 27.6] and 12.0 months [6.4, 17.6] for combination therapy and monotherapy, respectively). ORR was 24.3% (32% and 17% for combination therapy and monotherapy, respectively).

Conclusion

AutEMdev EMF exposure has an excellent safety profile in patients with advanced HCC. Hemodynamic alterations at personalized frequencies may represent a surrogate of anti‐tumor efficacy. NCT01686412.

Keywords: EMF, hemodynamics, hepatocellular carcinoma, low‐frequency electromagnetic fields, safety

1. BACKGROUND

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is a major global health issue that primarily affects patients with cirrhosis. 1 Most patients with unresectable disease have a poor prognosis, 2 , 3 and many with advanced HCC cannot tolerate systemic therapy. 3 , 4 Poor liver function in patients with advanced HCC arises from tumor‐associated loss of parenchyma and damage by anti‐cancer therapies. 5

Low‐energy radio frequency electromagnetic fields (EMFs) penetrate cells and can influence multiple cell biological processes via non‐thermal effects. 6 Low‐energy EMFs may offer an alternative treatment for advanced HCC, in combination with conventional therapies or as a monotherapy. 7 , 8 , 9 Modalities for EMF treatment in patients with cancer include the Autem electromagnetic device (AutEMdev) and tumor‐treating fields (TTFields). The AutEMdev technology involves intrabuccal delivery of EMFs to the whole body using a 27.12 MHz carrier frequency with amplitude modulation at specific frequencies in the range 10 Hz–20 kHz. 8 The device power of 100 mW is far below than that of a mobile telephone. 10 Amplitude modulation allows generation of different envelope waves with any frequency substantially lower than that of the carrier wave, as shown in Figure 1 and described in detail in a recent review. 10 This modality had a good safety profile with evidence of anti‐tumor effects in a phase 1/2 trial in patients with advanced HCC 7 and in a mouse xenograft model of HCC. 9 TTFields uses low‐energy alternating electric fields of intermediate frequency (∼100–500 kHz). 11 The US Food and Drug Administration approved TTFields as a monotherapy in patients with recurrent glioblastoma and mesothelioma, based on randomized phase 3 clinical trials. 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16

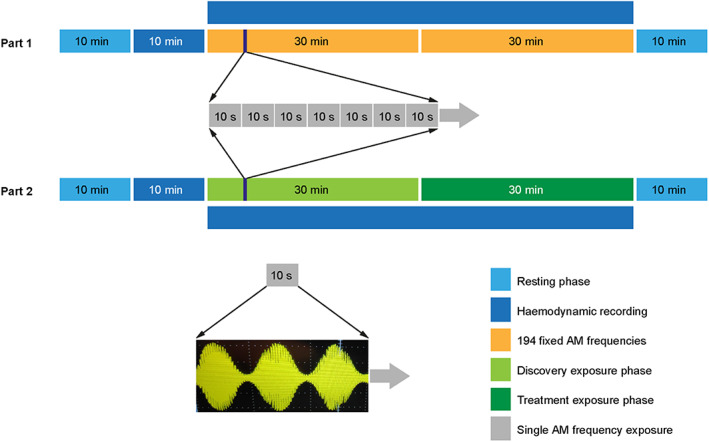

FIGURE 1.

Schematic of EMF exposure procedure using the AutEMdev in study parts 1 and 2. The bottom panel depicts amplitude modulation of the low‐energy 27.12 MHz carrier wave (rapid oscillation; short wavelength) to produce a therapeutic envelope wave with a lower frequency (slow oscillation, long wavelength), which can be any specific frequency in the range from 10 Hz to 20 kHz. Abbreviations: AM indicates amplitude‐modulated; AutEMdev, Autem electromagnetic device; EMF, electromagnetic field.

Evidence indicates that cancer cells may be more susceptible to perturbation by EMFs than normal cells. Ions and molecules with a high electrical dipole moment are susceptible to frequency‐dependent interactions with EMFs. 17 , 18 , 19 EMFs, therefore exert substantial dielectrophoretic forces on microtubules, which may disrupt cell division. 11 , 20 Transmembrane potentials drop from −90 to −20 mV or lower in cancer cells compared with normal cells, presumably because of alterations in ion channel dynamics. 21 , 22 Mitochondrial pH and potassium concentrations also change compared with normal cells. 23 , 24 These alterations may underlie the potentially beneficial effects of EMF exposure on cancer progression. 7 , 9 , 25 , 26

Low‐energy EMFs can also cause alterations in hemodynamic regulation. Although the underlying physiology is unclear, this may offer a route toward identification of potentially beneficial anti‐cancer effects. Heart rate variability and other beat‐to‐beat parameters can be analyzed using non‐linear computing methods as indicators of alterations in hemodynamic regulation during EMF exposure. 27 We hypothesize that amplitude‐modulation frequencies that alter the behavior of electrically excitable cells may also disrupt the proliferation of cancer cells. This predicts a non‐random distribution of hemodynamically active frequencies. A hemodynamic surrogate measure may allow identification of personalized anti‐cancer amplitude‐modulation frequencies. 28 , 29 , 30

We conducted an exploratory study of the AutEMdev in patients with advanced HCC and healthy controls. The study aimed to assess safety and feasibility, and to explore hemodynamic variability parameters as a means of personalizing EMF exposure.

2. METHODS

This was a prospective, open‐label study of the safety and feasibility of intrabuccal EMF exposure using the AutEMdev, with exploratory assessment of hemodynamic regulation alterations. The study had two sequential parts, both conducted in patients with HCC and healthy volunteers (Figure S1). Amplitude‐modulation frequencies were fixed in part 1 and variable in part 2, based on personalized frequencies associated with hemodynamic alterations (Figure 1). The study also included a historical control cohort.

2.1. Study population

Eligible patients were aged at least 18 years and had advanced HCC, defined as unresectable locally advanced or metastatic HCC, confirmed by histology or clinical presentation according to the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases criteria. 31 Child–Pugh A or B liver cirrhosis, Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer stage B or C, and Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status score of 0–2 were required. 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 There were no restrictions on disease progression status, hematological function, organ function, or current or previous therapy (including failure of all available systemic treatments). Eligible healthy volunteers were aged at least 18 years with no history of cancer. Key exclusion criteria for patients and healthy volunteers were cholangiocarcinoma, other active cancer, other life‐threatening medical conditions, implantable medical devices, and eligibility for loco‐regional therapy.

The historical control cohort was non‐interventional and retrospective, comprising patients with unresectable HCC identified from the Hospital Sírio‐Libanês Oncology Department electronic medical records using the keyword “liver cancer.” Patients had to have a diagnosis of advanced HCC after loco‐regional therapy, have been recommended for systemic therapy, or be receiving best supportive care.

2.2. Medical devices

Participants were exposed to low‐energy radio frequency EMFs using the AutEMdev (Autem Therapeutics). The AutEMdev is an autonomous high‐precision EMF generator designed to execute and control systemic exposure to low‐energy radio frequency EMFs with a carrier frequency of 27.12 MHz and sinusoidal amplitude modulation at frequencies ranging from 10 Hz to 20 kHz. EMF exposures via AutEMdev are within the safety levels published by the International Commission on Non‐Ionizing Radiation Protection. 36 Hemodynamic regulation was assessed using a non‐invasive continuous beat‐to‐beat recording device (Task Force Monitor or CNAP500; CNSystems, Graz, Austria) synchronized with the AutEMdev.

2.3. Quality of life assessment

Patients with HCC were required to complete the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire Core 30 (EORTC QLQ–C30) 37 before each AutEMdev exposure procedure. Completion was defined as answering at least 90% of the questions.

2.4. Study procedures

Patients were assigned to at least one 90‐min outpatient AutEMdev exposure procedure. Healthy volunteers were assigned to one exposure procedure only. Patients were invited to repeat procedures every 2–4 weeks if the patient or physician perceived quality of life improvement or objective tumor response. Patients could continue until withdrawal of consent or deterioration in quality of life (10% decrease from baseline in EORTC QLQ–C30 global health status). Patients could receive AutEMdev as a monotherapy or in combination with any conventional treatment approved by the Brazilian health regulatory agency, at any time. All patients were allowed to maintain any supportive care.

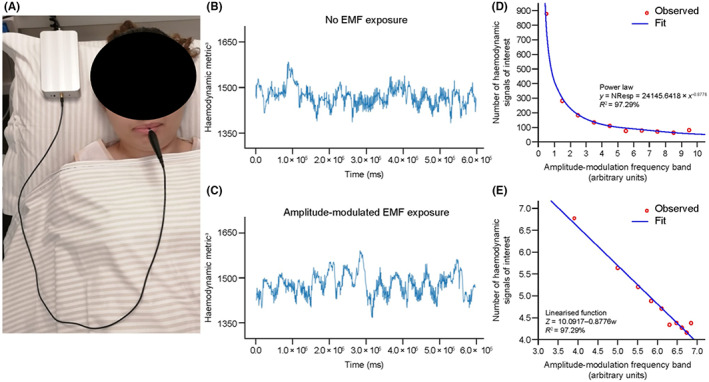

Exposure procedures were conducted with continuous assistance from healthcare professionals. Participants were placed in the supine position wearing a comfortable outfit in a quiet, low‐light ambiance to allow hemodynamic parameters to stabilize. Pressure cuffs were positioned, and the spoon‐shaped AutEMdev antenna was placed over the patient's tongue (Figure 2A). After 10 min, beat‐to‐beat continuous hemodynamic recording started and continued for 10 min (without EMF exposure). EMF exposure and amplitude modulation then started in synchronization with hemodynamic recording/reading and continued for 60 min (Figure 1). Equipment was removed and participants got dressed during the final 10 min of the 90‐min procedure. Exposure was supervised throughout the procedure to allow detection of exposure‐related toxicity or device malfunction. The procedure was aborted if the participant showed signs of intolerability (e.g., inability to tolerate decubitus, extreme discomfort).

FIGURE 2.

Hemodynamic variability alterations during EMF exposure with the AutEMdev. (A) Participant undergoing the procedure showing the AutEMdev and intrabuccal spoon‐shaped antenna. (B,C) Hemodynamic variability without and during exposure to amplitude‐modulated EMFs. (D) Power law distribution and (E) Linearized function for the number of hemodynamic signals of interest identified in 10 specific amplitude‐modulation frequency bands, following division of the time series into 100‐s intervals (data from study part 2). Abbreviations: AutEMdev indicates Autem electromagnetic device; EMF, electromagnetic field; NResp, number of responses (i.e., hemodynamic signals of interest).

2.5. Study design

All participants underwent baseline hemodynamic recording without EMF exposure for 10 min, followed by hemodynamic recording with EMF exposure for 60 min (Figure 1).

In part 1, all participants received two 30‐min exposures to a pre‐programmed fixed range and sequence of 194 separate modulation frequencies via the AutEMdev (Figure 1). Modulation frequencies were applied individually in sequence from lowest (10 kHz) to highest (20 kHz) for 10 s each during each 30‐min exposure.

In part 2, all participants underwent a 30‐min discovery phase followed by a 30‐min individualized phase (Figure 1). In the discovery phase, participants were exposed to a pre‐programmed fixed range and sequence of modulation frequencies (different from part 1) via the AutEMdev. Modulation frequencies were applied individually in sequence from lowest to highest for 10 s each. The AutEMdev then automatically used data filtering and post‐processing to construct a new personalized range and sequence of modulation frequencies, by identifying and prioritizing frequencies associated with hemodynamic signals of interest. Each participant was then exposed sequentially to their unique personalized treatment frequencies (Figure 1).

2.6. Endpoints

The predefined primary endpoints were safety and the identification of hemodynamic variability induced by the EMF exposure. Safety was assessed by monitoring the incidence of adverse events during exposure procedures. Adverse events were reported by investigators and their severity was graded using the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE). Adverse events were not systematically monitored at other times.

Exploratory patient‐reported quality‐of‐life endpoints included the proportion of patients with improvement and worsening and the time to deterioration in global health status, functional scale, and symptom scale (defined as a ≥10% change in EORTC QLQ–C30 score from baseline). Median overall survival (OS) in the intention‐to‐treat population was an exploratory safety endpoint, and was compared with OS in the historical control cohort.

No tumor assessments or clinical laboratory analyses were performed as part of the study. Routine results from radiological and laboratory assessments of patients were used (with primary physician approval) for ad hoc analyses of objective response rate using Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) v1.1, 38 as assessed by investigators and an independent blinded radiologist.

2.7. Hemodynamic analyses

Established hemodynamic time series algorithms were used to ensure stability and reproducibility. 27 We used an auto‐regressive integrated moving‐average model (Autem Mathematical Model) 39 in part 2 to identify hemodynamic signals of interest in the time series synchronized with the amplitude‐modulation frequencies. These were used as measures of hemodynamic variability induced by EMF exposure. Hemodynamic analysis of data collected in part 2 used power spectral density by fast Fourier transform. 40

2.8. Statistical methods

A minimum sample size of 45 patients with advanced HCC and 45 healthy controls was planned to study hemodynamic regulation. Statistical procedures were non‐parametric: Mann–Whitney U test and/or Kruskal–Wallis analysis of variance (ANOVA) for independent distributions; and Wilcoxon test and/or Friedman ANOVA for related distributions. EORTC QLQ–C30 analysis was performed according to the manual. 37 Kaplan–Meier analysis and the log‐rank Mantel–Cox test were used to compare OS in the patient cohort and the historical control cohort (two‐sided α = 0.05). Stratification factors included Child–Pugh classification, albumin–bilirubin (ALBI) score and line of treatment.

2.9. Conduct and oversight

Hospital Sírio‐Libanês was the only study site. All participants gave written informed consent before enrolment. The trial was conducted under the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and the protocol was reviewed and approved by the institutional review board and ethics committee of Hospital Sírio‐Libanês and by the Comissão Nacional de Ética em Pesquisa. After completion of planned enrolment, the Hospital Sírio‐Libanês ethics committee approved an ongoing compassionate access program following the same protocol with an amended consent form. The trial was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov before enrolment began (NCT01686412).

3. RESULTS

3.1. Participants

From March 2018 to March 2019, 47 patients with advanced HCC and 51 healthy volunteers were enrolled in parts 1 and 2 of the study (Figure S1). From April 2019 to August 2021 (data cut‐off), an additional 24 patients were enrolled in part 2 under the compassionate access program. Five patients in part 1 were subsequently found to be ineligible and excluded, two with excessive ascites that prohibited decubitus, and three with mixed cholangiocarcinoma on pathology review (Figure S1).

The study population comprised 66 patients and 51 healthy volunteers, who all underwent at least one AutEMdev exposure procedure (Figure 1). Baseline characteristics are presented in Table 1. Median follow‐up was 30 months (95% confidence interval [CI]: 23.9, 36.0) and no participants were lost to follow‐up. Part 1 comprised 26 patients and 32 healthy controls (fixed frequencies) and part 2 comprised 40 patients and 19 healthy volunteers (personalized frequencies). EMF was a monotherapy in 39 patients and a combination therapy in 27; concurrent treatments are shown in Table S1. Three patients in the monotherapy subgroup subsequently received combination therapy following radiological progression.

TABLE 1.

Baseline demographics and disease characteristics.

| Study population | Historical control cohort (n = 45) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All patients (N = 66) | Monotherapy subgroup (n = 39) | Combination therapy subgroup (n = 27) | ||

| Male, n (%) | 56 (85) | 33 (85) | 23 (85) | 41 (91) |

| Age, median (range) | 69.5 (32–88) | 71 (40–88) | 70 (32–85) | 66.8 (38–94) |

| Pathology confirmation, n (%) | 60 (91) | 34 (87) | 26 (96) | 13 (29) |

| Extrahepatic metastasis, n (%) | 31 (47) | 16 (41) | 14 (52) | 20 (44) |

| Child–Pugh class, n (%) | ||||

| A | 52 (79) | 28 (72) | 24 (89) | 34 (76) |

| B | 14 (21) | 11 (28) | 3 (11) | 11 (24) |

| ECOG performance status, n (%) | ||||

| 0 | 56 (85) | 31 (79) | 25 (93) | NA |

| 1 | 8 (12) | 6 (15) | 2 (7) | |

| 2 | 2 (3) | 2 (5) | 0 (0) | |

| BCLC stage, n (%) | ||||

| B | 22 (33) | 10 (26) | 12 (44) | NA |

| C | 44 (67) | 29 (74) | 15 (56) | |

| ALBI grade, a n (%) | ||||

| 1 | 36 (55) | 18 (46) | 18 (67) | NA |

| 2 | 22 (33) | 15 (38) | 7 (26) | |

| 3 | 7 (11) | 5 (13) | 2 (7) | |

| Previous treatment, n (%) | ||||

| Chemotherapy | 4 (6) | 0 (0) | 4 (15) | 1 (2) |

| TKI b | 14 (21) | 13 (33) | 1 (4) | 6 (13) |

| Immunotherapy | 2 (3) | 1 (3) | 1 (4) | 0 (0) |

| None | 46 (70) | 25 (64) | 21 (78) | 36 (80) |

| Concurrent treatment, b n (%) | ||||

| Chemotherapy | 6 (9) | 0 (0) | 6 (22) | 13 (29) |

| TKI c | 27 (41) | [2 (5)] d | 27 (100) | 24 (53) |

| Immunotherapy c | 7 (11) | [1 (3)] d | 7 (26) | 2 (4) |

| None | 39 (59) | 39 (100) | 0 (0) | 6 (13) |

Abbreviations: ALBI, albumin–bilirubin; BCLC, Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; NA, not available; TKI, tyrosine kinase inhibitor.

Missing in one patient.

Patients may have received more than one concurrent treatment during the study.

See Table 2 for details.

Three patients received standard treatment during follow‐up but were included in the monotherapy group.

3.2. Safety

During the 36‐month study period, 488 exposure procedures were performed in patients (median, 7.0 per patient [range, 1–42]) and 51 in healthy volunteers (one per volunteer, per protocol). All healthy volunteers tolerated the procedure. Two excluded patients were unable to tolerate decubitus during the pre‐exposure resting period (which was therefore unrelated to EMF exposure). No serious adverse events were reported during procedures. CTCAE grade 1 somnolence was the only adverse event, occurring in 52/66 patients (78.8%) and in 25/51 healthy volunteers (49.0%). This was characterized by mild but more than usual drowsiness or sleepiness, started within minutes of exposure initiation and ended spontaneously upon completion. All participants were able to resume normal activities after discharge.

3.3. Hemodynamics

The hemodynamic analysis included 134.3 h of continuous recording (5 × 105 heartbeats) from the 26 patients in part 1 (11.8 h for healthy volunteers). The technique for identifying hemodynamic signals of interest was applied to 13 patients in part 1 and all 40 patients in part 2. The frequency of variation in hemodynamic signals of interest ranged from 0.9 to 5.2 mHz. Hemodynamic signals of interest occurred more frequently in patients than in healthy volunteers (η p 2, 0.7973; p < 0.0001) and during exposure than non‐exposure in both patients and healthy volunteers (p = 0.0039 and p < 0.0001, respectively) (Figure 2B,C). Within patients, hemodynamic signals of interest differed significantly across amplitude‐modulation frequencies (p = 0.0018). In a detrended fluctuation analysis 41 the mean value for fluctuations (F[Δn]) was 1.000 (95% CI: 1.006, 1.011), indicating strong correlation of hemodynamic signals of interest with specific amplitude‐modulation frequencies. A power law defined the number of hemodynamic signals of interest occurring in patients as a function of amplitude‐modulation frequency band (Figure 2D,E). 42

3.4. Quality of life

From baseline (before first exposure) to the second, third, and fourth exposure, the majority of patients had improved or stable EORTC QLQ–C30 scores (Table S2). An increasing trend in global health status from baseline was noted over 25 exposures (p < 0.0001) (Figure S2). Median time to deterioration was not reached for global health status, 1.28 months (95% CI: 7.14, 15.42) for physical functioning, 11.28 months (4.34, 18.22) for role functioning, and 24.87 months (9.05, 40.69) for functioning score (Figure S2).

3.5. Overall survival

During follow‐up, 47/66 patients (71.2%) died from cancer. The median OS of 11.3 months (95% CI: 6.0, 16.6; N = 66) was significantly longer than in the in the historical cohort (5.2 months; p < 0.0001; N = 45; Table 1). Median OS was 16.0 months (95% CI: 4.4, 27.6) for combination therapy and 12.0 months (6.4, 17.6) for monotherapy. A subgroup analysis of OS is presented in Table 2. The median duration of sorafenib treatment was 3.4 months (95% CI: 0.0, 9.0) before enrolment (n = 10) and 6.7 months (0.0, 13.8) during study combination therapy (n = 18).

TABLE 2.

Subgroup analysis of OS.

| Patients, n | Deaths, n | Median OS, months (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| All patients | 66 | 47 | 11.3 (6.0, 16.6) |

| Part 1 | 26 | 21 | 11.4 (5.6, 17.0) |

| Part 2 | 40 | 26 | 10.6 (0.0, 21.4) |

| EMF combination therapy | 27 | 18 | 16.0 (4.4, 27.6) |

| EMF monotherapy | 39 | 29 | 12.0 (6.4, 17.6) |

| First‐line EMF | 46 | 29 | 18.4 (11.9, 24.9) |

| Second‐line EMF | 15 | 13 | 5.2 (0.0, 12.8) |

| ALBI grade 1 | 36 | 21 | 18.9 (13.2, 24.6) |

| ALBI grade 2 | 22 | 18 | 5.2 (0.0, 10.4) |

| First‐line EMF combination therapy | 23 | 15 | 18.4 (12.1, 24.7) |

| First‐line EMF monotherapy | 23 | 14 | 14.6 (1.2, 28.1) |

| First‐line EMF and ALBI grade 1 | 25 | 16 | 21.6 (1.4, 41.8) |

| First‐line EMF and ALBI grade 2 | 14 | 8 | 19.3 (4.3, 34.2) |

Abbreviations: ALBI, albumin–bilirubin; CI, confidence interval; EMF, electromagnetic field; OS, overall survival.

3.6. Radiological responses

By independent review in 37/66 patients (56.1%) with evaluable scans, the objective response rate by RECIST 1.1 was 6/19 (32%) for combination therapy and 3/18 (17%) for monotherapy, with complete responses in 1/19 (5%) and 2/18 (11%) patients, respectively (one with Child–Pugh class B) (Table 3). By investigator assessment in 47/66 patients (71.2%) with evaluable scans, the objective response rate was 10/47 (21.3%) (Table 3). Images from two patients with durable partial responses are shown in Figure 3.

TABLE 3.

RECIST v1.1 responses among evaluable patients.

| Independent review | Investigator read (n = 47) a | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monotherapy (n = 18) | Combination therapy (n = 19) | Overall (n = 37) a | ||

| Complete response, n (%) | 3 (17) b | 1 (5) | 4 (11) b | 4 (9) b |

| Partial response, n (%) | 1 (6) | 5 (26) | 6 (16) | 7 (15) |

| Stable disease, n (%) | 9 (50) | 10 (53) | 19 (51) | 25 (53) |

| Progressive disease, n (%) | 5 (28) | 3 (16) | 8 (22) | 11 (23) |

| Disease control rate, % | 72 c | 84 | 76 c | 74 c |

| Objective response rate, % | 17 | 32 | 24 | 21 |

Abbreviations: AutEMdev, generator of electromagnetics, EMF, electromagnetic field; RECIST, Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors.

Not all of the 66 patients in the study population had follow‐up scans available. 10 patients with data were not evaluable by independent review.

One of these four patients had a complete resection after EMF monotherapy with the AutEMdev and remained cancer‐free.

Excluding patient who received a complete resection and remained cancer‐free.

FIGURE 3.

Imaging of two patients with partial radiographic responses. (A) Metastatic liver disease in a patient receiving 35 AutEMdev EMF exposure procedures as monotherapy (magnetic resonance imaging). (B) Metastatic lung disease in a patient receiving 31 AutEMdev EMF exposure procedures in combination with first‐line lenvatinib (computed tomography). Red arrows indicate tumors. Abbreviations: AutEMdev indicates Autem electromagnetic device; EMF, electromagnetic field.

4. DISCUSSION

This feasibility trial confirmed the safety of EMF therapy with the AutEMdev in patients with advanced HCC, regardless of liver function (Child–Pugh class A–B), combination with systemic treatments and previous lines of therapy. No serious adverse events were reported in patients or healthy volunteers during any EMF exposure procedure. Quality of life was maintained among patients undergoing repeated exposures every 2–4 weeks. The extended OS compared with a historical control cohort indicated that AutEMdev EMF exposure was not harmful, and may suggest potential efficacy when combined with the radiological responses observed in a minority of patients.

AutEMdev EMF exposure caused subtle but reproducible alterations in hemodynamic regulation, as assessed using beat‐to‐beat heart rate variability measurements. 27 Similar findings have been reported, although the underlying physiopathology remains unclear. 28 , 29 , 30 , 43 Furthermore, hemodynamic variability induced by EMF exposure appeared to be more common in patients with cancer than controls, potentially because of alterations in homeostasis induced by the tumor load, although this requires further investigation. Specific amplitude‐modulation frequencies correlated with hemodynamic signals of interest and obeyed a power law, indicating a non‐random relationship. The significance of this finding remains unclear, and the present study did not aim to investigate whether the relationship between hemodynamic variability and specific amplitude‐modulation frequencies is associated with clinical efficacy or safety signals. Further studies are required to test the hypothesis that personalized amplitude‐modulation frequencies are associated with both hemodynamic signals of interest and potential clinical benefits.

Mild, self‐limiting somnolence was a common adverse event in individuals receiving AutEMdev EMF, consistent with previous findings. 44 , 45 , 46 In contrast, in patients receiving TTFields, dermatological adverse events are common and skin toxicity may limit exposure. 47 EMF exposure can affect α waves and is an option for treatment of depression and pain. 10 We speculate that an effect of EMF on excitable cells may underlie both hemodynamic alterations and somnolence. 10 Further studies are required to investigate this possibility.

OS was similar in patients receiving AutEMdev EMF monotherapy and combination therapy, including first‐line EMF. A trend toward increased duration of sorafenib treatment was observed among patients receiving combination therapy compared with pre‐enrolment. Furthermore, complete and partial RECIST v1.1 responses were observed in patients receiving EMF as a monotherapy and in combination with tyrosine kinase inhibitors. These exploratory findings warrant future investigation of the AutEMdev using personalized treatment frequencies in a prospective randomized‐controlled efficacy study.

Limitations of this study include the open‐label, single‐site design, and lack of a sham exposure procedure. This spared patients from placebo interventions and ensured consistency. Safety was only monitored during procedures, and did not include liver function tests. Few patients received PD(L)‐1 inhibitors because these were not approved in Brazil when the study began. Sources of significant potential bias included: wide eligibility criteria, selection of patients willing and able to participate; patients' freedom to repeat exposures; systemic treatment flexibility; and heterogeneity in the historical control arm. Another limitation was that the study did not aim to investigate the potential relationship between hemodynamic signals of interest and clinical efficacy or somnolence side‐effects. Strengths of the study include the blinded independent radiographic review, the evaluation of OS and the use of a validated patient‐reported outcome.

In conclusion, EMF treatment with the AutEMdev had an excellent safety profile in patients with advanced HCC, as both monotherapy and combination therapy. There was evidence for maintained quality of life among patients who remained on treatment. Hemodynamic variability during exposure may provide a biological surrogate for identification of optimal amplitude‐modulation frequencies in each patient. Whether these personalized frequencies are also optimal for potential anti‐tumor effects remains to be established. This study was not designed to assess efficacy, but the positive exploratory trends warrant further investigation.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Fernanda Capareli: Investigation (lead). Frederico Costa: Investigation (equal) and Methodology (equal). Jack Tuszynski: Methodology (equal). Micelange Carvalho de Sousa: Investigation (equal). Yone de Camargo Setogute: Investigation (equal). Pablo Diego Santana: Investigation (equal). Luciana Carvalho: Investigation (equal). Elizabeth Santana dos Santos: Investigation (equal). Brenda Gumz: Investigation (equal). Jorge Sabbaga: Investigation (equal). Tiago Bianc de Castria: Investigation (equal). Denis Leonardo Jardim: Investigation (equal). Daniela de Freitas: Investigation (equal). Natally Horvat: Data curation (equal). Regis França Otaviano: Data curation (equal). Leonardo Testagrossa: Data curation (equal). Tiago Costa: Data curation (equal). Tatiana Zanesco: Investigation (equal). Antonio Francisco Iemma: Data curation (equal). Ghassan K Abou‐Alfa: Writing – review and editing (lead).

FUNDING INFORMATION

Hospital Sírio‐Libanês sponsored this trial and provided the non‐invasive hemodynamic device. The study was part‐funded by National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA008748 to Natally Horvat. The AutEMdev was provided by Autem Therapeutics under a research development agreement with Hospital Sírio‐Libanês. Medical writing support was provided by Oxford PharmaGenesis, Oxford, UK, funded by Autem Therapeutics. Clinical records were reviewed by an independent auditor from Emergo (Austin, TX, USA) and radiological review was conducted by an independent blinded radiologist from Charité–Universitätsmedizin Berlin (Berlin, Germany), funded by Autem Therapeutics.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

TBC: Honoraria, consultancy fees or research funding from AstraZeneca, Bayer, Eli Lilly, Genentech/Roche, Bristol Myers Squibb, Merck and Merck Sharp & Dohme. FC, AFI, and JA: Stock in and honoraria from Autem Therapeutics and patents relating to the AutEMdev. YdCS: Honoraria from Bayer, Merck and Novartis and independent contractor at Hospital Sirio‐Libanês. GKA‐A: Institutional research support from Arcus, Astra Zeneca, BioNtech, BMS, Celgene, Flatiron, Genentech/Roche, Genoscience, Incyte, Polaris, Puma, QED, Silenseed, Yiviva; consulting fees from Adicet, Alnylam, Astra Zeneca, Autem, Beigene, Berry Genomics, Boehringer Ingelheim, Celgene, Cend, CytomX, Eisai, Eli Lilly, Exelixis, Flatiron, Genentech/Roche, Genoscience, Helio, Helsinn, Incyte, Ipsen, Merck, Nerviano, Newbridge, Novartis, QED, Redhill, Rafael, Servier, Silenseed, Sobi, Vector, Yiviva; registered patent: PCT/US2014/031545 filed on March 24, 2014, and priority application Serial No.: 61/804,907; Filed: March 25, 2013. DLJ honoraria, consultancy fees or research funding from AstraZeneca, Bayer, Janssen, Astellas, Genentech/Roche, Bristol Myers Squibb, Merck and Merck Sharp & Dohme.

Supporting information

Data S1.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the patients, volunteers, and study site staff who participated in the study. We thank Dr. Luis F. L. Reis from Hospital Sírio‐Libanês for supervising and advising on post hoc analyses. We thank Dr. Bertram Wiedenmann from Autem Therapeutics for reviewing the manuscript for scientific accuracy.

Capareli F, Costa F, Tuszynski JA, et al. Low‐energy amplitude‐modulated electromagnetic field exposure: Feasibility study in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Med. 2023;12:12402‐12412. doi: 10.1002/cam4.5944

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.

REFERENCES

- 1. Llovet JM, Ricci S, Mazzaferro V, et al. Sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:378‐390. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0708857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bruix J, Llovet JM. Prognostic prediction and treatment strategy in hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2002;35:519‐524. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.32089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Couto OFM, Dvorchik I, Carr BI. Causes of death in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Dig Dis Sci. 2007;52:3285‐3289. doi: 10.1007/s10620-007-9750-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Llovet JM, Kelley RK, Villanueva A, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2021;7:6. doi: 10.1038/s41572-020-00240-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bialecki ES, Di Bisceglie AM. Clinical presentation and natural course of hepatocellular carcinoma. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;17:485‐489. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200505000-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Meijer D, Geesink H. Favourable and unfavourable EMF frequency patterns in cancer: perspectives for improved therapy and prevention. J Cancer Ther. 2018;09:188‐230. doi: 10.4236/jct.2018.93019 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Costa FP, de Oliveira AC, Meirelles R, et al. Treatment of advanced hepatocellular carcinoma with very low levels of amplitude‐modulated electromagnetic fields. Br J Cancer. 2011;105:640‐648. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Zimmerman JW, Jimenez H, Pennison MJ, et al. Targeted treatment of cancer with radiofrequency electromagnetic fields amplitude‐modulated at tumor‐specific frequencies. Chin J Cancer. 2013;32:573‐581. doi: 10.5732/cjc.013.10177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Jimenez H, Wang M, Zimmerman JW, et al. Tumour‐specific amplitude‐modulated radiofrequency electromagnetic fields induce differentiation of hepatocellular carcinoma via targeting Cav3.2T‐type voltage‐gated calcium channels and Ca(2+) influx. EBioMedicine. 2019;44:209‐224. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2019.05.034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tuszynski JA, Costa F. Low‐energy amplitude‐modulated radiofrequency electromagnetic fields as a systemic treatment for cancer: review and proposed mechanisms of action. Front Med Technol. 2022;4:869155. doi: 10.3389/fmedt.2022.869155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tuszynski JA, Wenger C, Friesen DE, Preto J. An overview of sub‐cellular mechanisms involved in the action of TTFields. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2016;13:13. doi: 10.3390/ijerph13111128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Stupp R, Taillibert S, Kanner AA, et al. Maintenance therapy with tumor‐treating fields plus temozolomide vs temozolomide alone for glioblastoma: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2015;314:2535‐2543. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.16669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mumblat H, Martinez‐Conde A, Braten O, et al. Tumor treating fields (TTFields) downregulate the Fanconi anemia‐BRCA pathway and increase the efficacy of chemotherapy in malignant pleural mesothelioma preclinical models. Lung Cancer. 2021;160:99‐110. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2021.08.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Davies AM, Weinberg U, Palti Y. Tumor treating fields: a new frontier in cancer therapy. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2013;1291:86‐95. doi: 10.1111/nyas.12112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kirson ED, Gurvich Z, Schneiderman R, et al. Disruption of cancer cell replication by alternating electric fields. Cancer Res. 2004;64:3288‐3295. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-04-0083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kirson ED, Schneiderman RS, Dbaly V, et al. Chemotherapeutic treatment efficacy and sensitivity are increased by adjuvant alternating electric fields (TTFields). BMC Med Phys. 2009;9:1. doi: 10.1186/1756-6649-9-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Schofield Z, Meloni GN, Tran P, et al. Bioelectrical understanding and engineering of cell biology. J R Soc Interface. 2020;17: 20200013. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2020.0013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kaestner L, Wang X, Hertz L, Bernhardt I. Voltage‐activated ion channels in non‐excitable cells‐a viewpoint regarding their physiological justification. Front Physiol. 2018;9:450. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2018.00450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Eaton DC. The electrical properties of cells . In: Niemtzow RC, ed. Transmembrane Potentials and Characteristics of Immune and Tumor Cell . CRC Press; ; 1985. . [Google Scholar]

- 20. Vassilev PM, Dronzine RT, Vassileva MP, Georgiev GA. Parallel arrays of microtubules formed in electric and magnetic fields. Biosci Rep. 1982;2:1025‐1029. doi: 10.1007/BF01122171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Harguindey S, Stanciu D, Devesa J, et al. Cellular acidification as a new approach to cancer treatment and to the understanding and therapeutics of neurodegenerative diseases. Semin Cancer Biol. 2017;43:157‐179. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2017.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Yang M, Brackenbury WJ. Membrane potential and cancer progression. Front Physiol. 2013;4:185. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2013.00185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Al Ahmad M, Al Natour Z, Mustafa F, Rizvi TA. Electrical characterization of normal and cancer cells. IEEE Access. 2018;6:25979‐25986. doi: 10.1109/ACCESS.2018.2830883 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Payne SL, Ram P, Srinivasan DH, Le TT, Levin M, Oudin MJ. Potassium channel‐driven bioelectric signalling regulates metastasis in triple‐negative breast cancer. EBioMedicine. 2022;75:103767. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2021.103767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Havelka D, Kucera O, Deriu MA, Cifra M. Electro‐acoustic behavior of the mitotic spindle: a semi‐classical coarse‐grained model. PLoS One. 2014;9:e86501. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0086501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zimmerman JW, Pennison MJ, Brezovich I, et al. Cancer cell proliferation is inhibited by specific modulation frequencies. Br J Cancer. 2012;106:307‐313. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Heart rate variability . Standards of measurement, physiological interpretation, and clinical use. Task force of the European Society of Cardiology and the north American Society of Pacing and Electrophysiology. Eur Heart J. 1996;17:354‐381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Andrzejak R, Poreba R, Poreba M, et al. The influence of the call with a mobile phone on heart rate variability parameters in healthy volunteers. Ind Health. 2008;46:409‐417. doi: 10.2486/indhealth.46.409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Misek J, Belyaev I, Jakusova V, Tonhajzerova I, Barabas J, Jakus J. Heart rate variability affected by radiofrequency electromagnetic field in adolescent students. Bioelectromagnetics. 2018;39:277‐288. doi: 10.1002/bem.22115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Misek J, Veternik M, Tonhajzerova I, et al. Radiofrequency electromagnetic field affects heart rate variability in rabbits. Physiol Res. 2020;69:633‐643. doi: 10.33549/physiolres.934425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Marrero JA, Kulik LM, Sirlin CB, et al. Diagnosis, staging, and management of hepatocellular carcinoma: 2018 practice guidance by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology. 2018;68:723‐750. doi: 10.1002/hep.29913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Child CG, Turcotte JG. Surgery and portal hypertension. Major Probl Clin Surg. 1964;1:1‐85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Pugh RN, Murray‐Lyon IM, Dawson JL, Pietroni MC, Williams R. Transection of the oesophagus for bleeding oesophageal varices. Br J Surg. 1973;60:646‐649. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800600817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Llovet JM, Bru C, Bruix J. Prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma: the BCLC staging classification. Semin Liver Dis. 1999;19:329‐338. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1007122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Oken MM, Creech RH, Tormey DC, et al. Toxicity and response criteria of the eastern cooperative oncology group. Am J Clin Oncol. 1982;5:649‐655. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. International Commission on Non‐Ionizing Radiation Protection . Guidelines for limiting exposure to electromagnetic fields (100 kHz to 300 GHz). Health Phys. 2020;118:483‐524. doi: 10.1097/HP.0000000000001210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, et al. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of cancer QLQ‐C30: a quality‐of‐life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85:365‐376. doi: 10.1093/jnci/85.5.365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:228‐247. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Nelson BK. Statistical methodology: V. time series analysis using autoregressive integrated moving average (ARIMA) models. Acad Emerg Med. 1998;5:739‐744. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.1998.tb02493.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Parati G, Saul JP, Di Rienzo M, Mancia G. Spectral analysis of blood pressure and heart rate variability in evaluating cardiovascular regulation. A Critical Appraisal Hypertension. 1995;25:1276‐1286. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.25.6.1276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Bryce RM, Sprague KB. Revisiting detrended fluctuation analysis. Sci Rep. 2012;2:315. doi: 10.1038/srep00315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Lorimer T, Gomez F, Stoop R. Two universal physical principles shape the power‐law statistics of real‐world networks. Sci Rep. 2015;5:12353. doi: 10.1038/srep12353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ekici B, Tanindi A, Ekici G, Diker E. The effects of the duration of mobile phone use on heart rate variability parameters in healthy subjects. Anatol J Cardiol. 2016;16:833‐838. doi: 10.14744/AnatolJCardiol.2016.6717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Reite M, Higgs L, Lebet JP, et al. Sleep inducing effect of low energy emission therapy. Bioelectromagnetics. 1994;15:67‐75. doi: 10.1002/bem.2250150110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Pasche B, Erman M, Hayduk R, et al. Effects of low energy emission therapy in chronic psychophysiological insomnia. Sleep. 1996;19:327‐336. doi: 10.1093/sleep/19.4.327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kelly TL, Kripke DF, Hayduk R, Ryman D, Pasche B, Barbault A. Bright light and LEET effects on circadian rhythms, sleep and cognitive performance. Stress Med. 1997;13:251‐258. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099‐1700(199710)13:4<251::AID‐SMI750>3.0.CO;2‐0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Lukas RV, Ratermann KL, Wong ET, Villano JL. Skin toxicities associated with tumor treating fields: case based review. J Neurooncol. 2017;135:593‐599. doi: 10.1007/s11060-017-2612-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data S1.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.