Abstract

Background:

Preterm infants are uniquely vulnerable to early toxic stress exposure while in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) and also being at risk for suboptimal neurodevelopmental outcomes. However, the complex biological mechanisms responsible for variations in preterm infants’ neurodevelopmental outcomes because of early toxic stress exposure in the NICU remain unknown. Innovative preterm behavioral epigenetics research offers a possible mechanism and describes how early toxic stress exposure may lead to epigenetic alterations, potentially affecting short- and long-term outcomes.

Objective:

The aim of this study was to review the relationships between early toxic stress exposures in the NICU and epigenetic alterations in preterm infants. The measurement of early toxic stress exposure in the NICU and effect of epigenetic alterations on neurodevelopmental outcomes in preterm infants were also examined.

Methods:

We conducted a scoping review of the literature published between January 2011 and December 2021 using databases PubMed, CINAHL, Cochrance Library, PsycINFO, and Web of Science. Primary data-based research that examined epigenetics, stress, and preterm infants or NICU were included.

Results:

A total of 13 articles from nine studies were included. DNA methylations of six specific genes were studied in relation to early toxic stress exposure in the NICU: SLC6A4, SLC6A3, OPRMI, NR3C1, HSD11B2, and PLAGL1. These genes are responsible for regulating serotonin, dopamine, and cortisol. Poorer neurodevelopmental outcomes were associated with alterations in DNA methylation of SLC6A4, NR3C1, and HSD11B2. Measurements of early toxic stress exposure in the NICU were inconsistent among the studies.

Discussion:

Epigenetic alterations secondary to early toxic stress exposures in the NICU may be associated with future neurodevelopmental outcomes in preterm infants. Common data elements of toxic stress exposure in preterm infants are needed. Identification of the epigenome and mechanisms by which early toxic stress exposure leads to epigenetic alterations in this vulnerable population will provide evidence to design and test individualized intervention.

Keywords: epigenesis, genetic, infant, physiological, preterm, stress

Preterm infants hospitalized in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) are frequently exposed to early and repeated stressful circumstances, including numerous painful procedures, excessive exposure to light and sound, and prolonged separation from parents (Cheong et al., 2020; El-Metwally & Medina, 2020). These stressful events have the potential to be severe, frequent, and/or prolonged, increasing the risk for disruptions in the physiology of preterm infants (Weber & Harrison, 2019). Toxic stress is the maladaptive and chronic dysregulation of the stress response resulting from severe, frequent, and prolonged adversity during sensitive periods of development without protective factors (Bucci et al., 2016). Preterm infants’ central nervous systems are immature and at unique risk for injury—which may affect subsequent neurodevelopment (Duncan & Matthews, 2018). Thus, toxic stress may pose numerous deleterious effects on preterm infants’ neurodevelopment and escalate the risk for suboptimal outcomes. Preterm infants are more likely to have autism, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, learning impairments, and increased depression and anxiety later in life (DʼAgata et al., 2016). Nonetheless, the complex biological mechanisms responsible for variations in preterm infants’ neurodevelopmental outcomes because of early toxic stress exposure in the NICU remain largely unknown.

Epigenetics is a field of study focused on phenotypic changes that do not involve alterations in the DNA sequence. Epigenetic alterations occur through chemical changes to the DNA and result in a change (increase or decrease) in gene expression that produces phenotypic variations. Epigenetic alterations are sensitive to environmental exposures and experiences and can influence health and illness (Cavalli & Heard, 2019). Preterm behavioral epigenetics is an emerging field of study that links early life stress, gene modifications, neurodevelopmental alterations, and risk for future illness (Griffith et al., 2020; Provenzi, Guida, & Montirosso, 2018). Novel research within the field offers evidence describing how early toxic stress exposure may lead to epigenetic alterations, which may be critical in shaping neurodevelopmental outcomes. Specifically, prenatal exposures to adverse events, NICU-related stress, and NICU-related quality of care, all influence the preterm infants’ phenotypes through epigenetic mechanisms (Montirosso & Provenzi, 2015). Building upon the recent work of Provenzi, Guida, and Montirosso (2018) elucidating the epigenetic mechanisms resulting from NICU early toxic-related stress exposure and connecting them to phenotypic changes and altered neurodevelopment is needed to further clarify the pathways of the preterm behavioral epigenetics model.

It is a scientific priority to clarify the relationships between stress-related epigenetic alterations and neurodevelopmental outcomes in preterm infants (Nist et al., 2019). However, the linkage between NICU early toxic stress exposure and epigenetic alterations in preterm infants is unknown. The lack of standardized valid measurements of early toxic stress exposure in preterm infants further complicates the ability to address its effect on preterm infants’ neurobehavioral outcomes reliably. A recent systematic review of neonatal stress and development acknowledged that stress is often operationalized as skin-breaking procedures in the NICU but also recognized that there remains an extensive range of neonatal stressors in the NICU that are understudied (van Dokkum et al., 2021). Further exploration of these concepts is needed. The research questions of this scoping review are as follows:

What are the relationships between early toxic stress exposure in the NICU and epigenetic alterations as measured by DNA methylation in preterm infants?

What is the effect of stress-related epigenetic alterations as measured by DNA methylation on neurodevelopmental outcomes in preterm infants?

What measurements of early toxic stress exposures in the NICU have been used in previous research within the context of stress-related epigenetic modifications?

METHODS

A scoping review of the literature was determined to be the most appropriate form of review because the concepts of early neonatal stress, epigenetic alterations in preterm infants, and neurodevelopmental outcomes secondary to epigenetic alterations in this population are contemporary and remain ill-defined (Arksey & O’Malley, 2005). As evidence about these concepts emerges, there is a need to map their definitions and relationships to identify the gaps and guide future research (Munn et al., 2018). Using Arksey and O’Malley’s (2005) five steps for conducting a scoping review, the authors (a) identified research questions, (b) identified relevant studies, (c) selected studies, (d) charted the data, and (d) collated/summarized and reported the findings.

Eligibility Criteria

Eligibility criteria included (a) use of DNA methylation as epigenetic measurements, (b) focus on preterm infants, (c) measuring stress during NICU hospitalization, and (d) original research.

Search Strategy

Searches were conducted in April 2021 in collaboration with a nursing librarian (A. V. F.). Search strategies, including specific terminology and electronic databases, were selected (see Supplemental Table 1, http://links.lww.com/NRES/A461). The following electronic databases were searched: PubMed, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Cochrane Library (including trials), PsycINFO, and Web of Science. The search strategies were developed in PubMed using a combination of database-controlled vocabulary—Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)—and text words. Once the initial search was determined, it was modified to fit the parameters of the other databases (e.g., CINAHL headings). The parameters included epigenetics, stress—both physiological and psychology—and preterm infants or NICU. Sample terminology included “epigenomics”[MeSH], “epigenesis, genetic”[MeSH], “stress, psychological”[MeSH], “infant, premataure”[MeSH], and “intensive care units, neonatal”[MeSH]. With the other database searches, text words were searched. Results were limited to English language, 2011–2021, and humans.

Selection and Data Collection Process

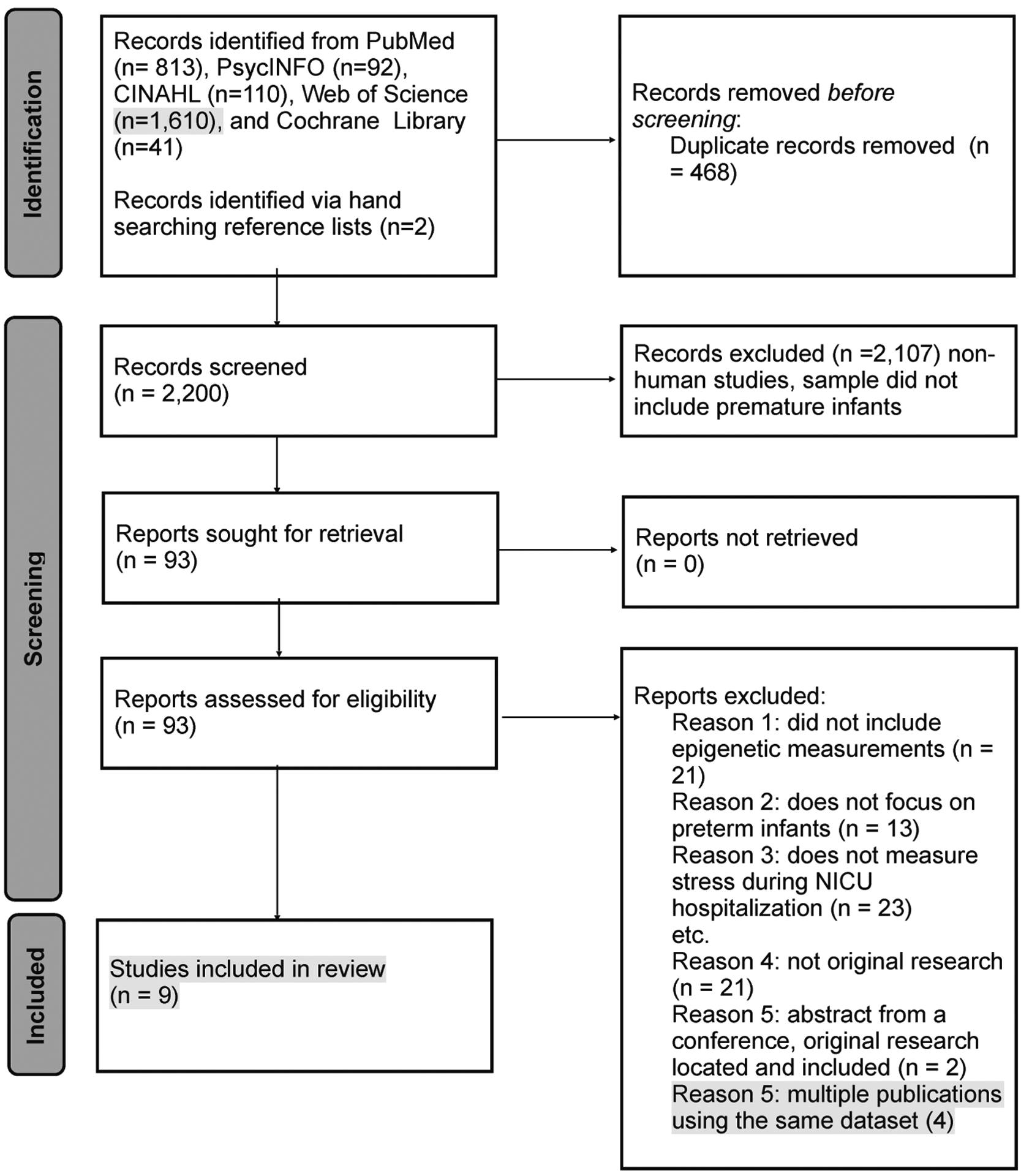

Articles were screened for eligibility by four authors (KM, KG,RM, TG). All authors met to discuss conflicts, and they decided to include or exclude the article. Four authors evaluated each article for strength and quality (KM, KG, RM, TG). Data were extracted into Excel files. The four authors read and discussed the findings to form themes relating to relationships between the major concepts. Figure 1 displays the literature search results in a PRISMA flow diagram and cites reasons for exclusion of articles.

FIGURE 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of the literature search results and reasons for exclusion of articles. NICU = neonatal intensive care unit.

RESULTS

Thirteen articles met the inclusion criteria for this scoping review. Five of the articles used the same data set, and so only the primary article detailing the findings from the data set was included in the analysis (Provenzi et al., 2015). All articles measured DNA methylation as epigenetic alterations as opposed to other mechanisms. Details regarding epigenetic alterations, early toxic stress exposures, and neurodevelopmental outcomes are displayed in Table 1. Only one study examined the whole DNA methylome and did not identify specific genes to study a priori (Lorente-Pozo et al., 2018). The epigenetic alterations of six specific genes were studied in relation to early toxic stress exposure in the NICU. These genes include SLC6A4, SLC6A3, OPRMI, NR3C1, HSD11B2, and PLAGL1. Two of the total articles included data analysis, and three articles using data from one of the original research data sets evaluated neurodevelopmental outcomes (Arpón et al., 2018; Chau et al., 2014; Fumagalli et al., 2018; Montirosso, Provenzi, Fumagalli, et al., 2016; Montirosso, Provenzi, Giorda, et al., 2016; Provenzi et al., 2020). Early toxic stress exposure, epigenetic alterations, and neurodevelopmental outcomes were measured at different time points across the studies, ranging from birth to 7 years of age (Chau et al., 2014; Fumagalli et al., 2018; Kantake et al., 2014; Lorente-Pozo et al., 2018; Montirosso, Provenzi, Fumagalli, et al., 2016; Montirosso, Provenzi, Giorda, et al., 2016; Provenzi, Carli, et al., 2018; Provenzi et al., 2015, 2020). Figure 2 displays mapping of identified relationships between sources of early toxic stress exposure in NICU, epigenetic alterations, and neurodevelopmental outcomes.

TABLE 1.

Details of Original Studies Included in This Review (n = 9)

| Author (year), country | Study aims | Methods/sample | Source or measurement of toxic stress | Genetic marker studies/time of measurement | Source of tissue used for epigenetic measurement | Relationship between stress and DNA methylation | Association between DNA methylation and neurodevelopment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arpón etal. (2018), Spain | Determine epigenetic differences between preterm and full-term newborns, which could help explain the adverse effects associated with prematurity | Prospective, observational study of 24 preterm (GA <34 weeks) and 22 full-term infants | NICU hospitalization | SLC6A3 at 12 months corrected age | Blood | Increased DNA methylation of cg00997378 associated with prematurity risk factors and decreased BSID scores in simple linear regression. | Preterm infants with methylation changes in SLC6A3 were associated with prematurity risk factors demonstrated decreased BSID-II motor and mental scores at 24/36 months. |

| Chau et al. (2014), Canada | Examine (1) if methylation of SLC6A4 promoter differed between very preterm children and full-term controls at 7 years, (2) relationships with child behavior problems, (3) extent of neonatal pain and COMT Val158Met genotype and SLC6A4 methylation | Cross-sectional study of 111 school age children; 61 born very preterm and 50 born full-term | NICU hospitalization and neonatal pain (skin-breaking procedures) | SLC6A4, 7 years of age | Saliva | Very preterm children had increased DNA methylation at 7 of 10 CpG sites in SLC6A4 compared to full-term children. Increased neonatal pain was associated with decreased DNA methylation of SLC6A4 only in children with COMT Met genotype. | Neonatal pain was associated with increased total child behavior problems using CBCL. The CBCL total problems was associated with greater SLC6A4 methylation. |

| Giarraputo et al. (2017), United States | Examine the relationships between medical morbidities in preterm infants and DNA methylation of NR3C1 | Observational study of 67 preterm infants weighing <1,500 g | 36 different medical variables including neonatal therapeutic intervention scoring scores | Promoter region 1F of NR3C1, at time of NICU discharge | Buccal epithelial cells | Decreased DNA methylation at CpG1 in infants in the “high-risk” medical group. | N/A |

| Hatfield et al. (2018), United States | Determine the effectiveness of a noninvasive DNA sampling technique for comparing epigenetic modifications | Proof-of-concept study, 12 infants: 6 healthy term infants and 6 preterm infants (<37 weeks gestation) | NICU hospitalization | 5’-end of the OPRMI gene, time of admission to nursery and time of discharge from nursery or NICU | Saliva | No difference in OPRMI DNA methylation between healthy term infants and preterm infants | N/A |

| Kantake et al. (2014), Japan | Examine environmental effects on cytosine methylation of preterm infants DNA | Prospective cohort study, 20 term and 20 preterm (<37 weeks gestation and NICU admission) | NICU hospitalization | 1-F promoter region of NR3C1, time of birth, and 4 days of life | Blood | Increased DNA methylation of 1-F promoter region of GR gene in preterm infants. Methylation rates on day of life 4 predicted the occurrence of later complications requiring glucocorticoid administration | N/A |

| Lester et al. (2015), United States | Determine if methylation of HSD11B2 and NR3C1 is associated with neurobehavioral profiles in preterm infants | Observational study of 67 preterm infants (23–35 weeks gestation) | NICU hospitalization and designated medical variables (e.g., gestational age, length of stay) | HSD11B2 and NR3C1, at time of NICU discharge | Buccal epithelial cells | Infants with high-risk neurobehavioral profiles had increased DNA methylation at CpG3 for NR3C1 and decreased DNA methylation of CPG3 for HSD11B2. | At the time of discharge from the NICU, infants with high-risk profiles based on the NNNS demonstrated poor selfregulation, were highly excitable, and showed poor quality of movement and substantial stress signs. |

| Lorente-Pozo et al. (2018), Spain | Determine whether the amount of oxygen provided during postnatal stabilization changes the DNA methylome in preterm infants | Prospective, observational study of 32 preterm infants (<32 weeks gestation) who received oxygen in the delivery room | Oxygen requirement at time of birth | Whole DNA methylome, before and after oxygen administration in the delivery room | Blood | Oxygen loads of >500 ml o2/kg changed the methylation pattern of selected CpGs. Genes associated with these CpGs were enriched in KEGG pathways involved in cell cycle progression, DNA repair, and oxidative stress. | N/A |

| Provenzi et al. (2015), Italy | Investigate the relationships between levels of pain-related stress and changes in SLC6A4 methylation at NICU discharge very premature infants | Prospective, observational study of 88 infants (56 very preterm ≤32 weeks gestation and 32 term infants) | Pain-related stress (number of skin-breaking procedures) | SLC6A4, collected at time of birth and time of NICU discharge in preterm infants | Blood | No difference in SLC6A4 DNA methylation at time of birth.Increased DNA methylation at CpG sites 5 and 6 at time of discharge in infants with high pain exposure during NICU. | N/A |

| Provenzi, Carli et al. (2018), Italy | To compare PLAGL1 methylation between very premature infants and full term infants | Longitudinal, cohort study, 56 preterm infants (≤32 weeks gestation) and 27 full term infants | Prematurity and NICU hospitalization | PLAGL1 | Blood | PLAGL1 decreased DNA methylation at birth and at discharge was highly correlated in preterm infants. | N/A |

Note. GA = gestational age; NICU = neonatal intensive care unit; BSID = Bailey Scale of Infant Development; CBCL = Child Behavior Checklist; NNNS = NICU Network Neurobehavioral Scale; N/A = not applicable.

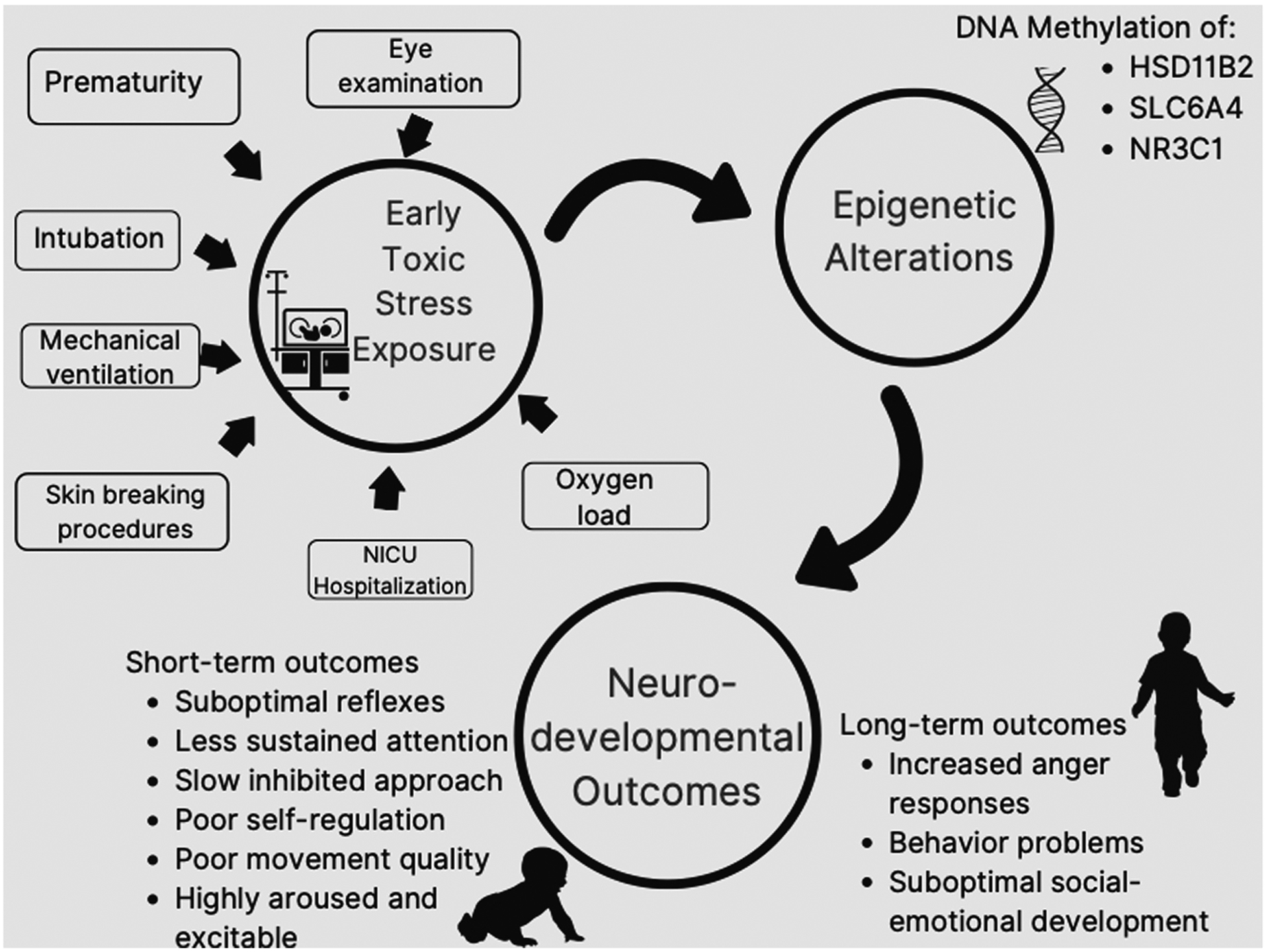

FIGURE 2.

Mapping of identified relationships between sources of early toxic stress exposure in the NICU, epigenetic alterations, and neurodevelopmental outcomes in preterm infants. Short-term neurodevelopmental outcomes include outcomes up to 36 months of age. Long-term neurodevelopmental outcomes included outcomes after 36 months of age. NICU = neonatal intensive care unit.

Relationship Between Early Toxic Stress Exposure in the NICU and Epigenetic Alterations in Preterm Infants

SLC6A4 was one of the most frequently studied genes in relation to early stress exposure in the NICU. Two primary studies in this review included the DNA methylation of SLC6A4 (Chau et al., 2014; Provenzi et al., 2015). One study utilized longitudinal measurements of SLC6A4, beginning at the time of birth/admission to the NICU (Provenzi et al., 2015). The other used a cross-sectional design to examine the DNA methylation of SLC6A4 of preterm children and full-term controls at 7 years of life (Chau et al., 2014). Higher levels of early toxic stress exposure in the NICU were associated with increased DNA methylation of SLC6A4 at the time of NICU discharge (Provenzi et al., 2015). Specifically, increased DNA methylation at CpG5 and CpG6 was identified at the time of NICU discharge in the infants with higher levels of pain exposure during NICU hospitalization as compared to preterm infants with lower levels of pain exposure (Provenzi et al., 2015). Notably, an increase in DNA methylation of seven different CpG sites of SLC6A4 at 7 years of age in children born extremely preterm and experienced increased neonatal pain exposure was also identified (Chau et al., 2014). Distinctly, decreased DNA methylation of SLC6A4 was identified in children with COMT VAL158Met genotype who experienced increased neonatal pain (Chau et al., 2014).

One study in this review examined the DNA methylation patterns of SLC6A3 in preterm infants using a prospective, observational design (Arpón et al., 2018). At 12 months of life, preterm infants born less than 34 weeks gestation demonstrated a significantly higher level of DNA methylation at the CpG site cg00997378 of the SLC6A3 as compared to full-term infants (Arpón et al., 2018).

Using an innovative longitudinal approach, Hatfield et al., 2018 concentrated on the opioid receptor gene OPRM1. In a pilot feasibility study examining the difference in DNA methylation of the 5′-end of the OPRM1 gene from buccal cell samples taken at admission and discharge in six healthy full-term infants in the newborn nursery and in six preterm infants exposed to repeated painful procedures in the NICU, there was no difference in the DNA methylation of the OPRM1 gene between the groups (Hatfield et al., 2018).

Three studies examined the relationships between early stress exposures in the NICU and DNA methylation of theNR3C1 gene using a mix of cross-sectional and longitudinal designs. Two study research teams hypothesized that, in preterm infants, postnatal biological and environmental stressors may influence the epigenetic alterations (measured by DNA methylation in buccal cells) of NR3C1, thus affecting early neurobehavior (Giarraputo et al., 2017; Lester et al., 2015). Infants with several medical morbidities (“high risk”) demonstrated decreased DNA methylation at the CpG1 site of the NR3C1 gene promoter (Giarraputo et al., 2017). Whereas in another study, infants with high-risk neurobehavioral profiles demonstrated increased DNA methylation at the CpG3 site of the NR3C1 gene promoter (Lester et al., 2015). In preterm infants, between birth and Day 4 postpartum, DNA methylation of the NR3C1 gene promoter increased significantly at 11 CpG sites (1, 2, 8, 9, 10, 14, 16, 25, 26, 28, and 29) and decreased significantly at the CpG4 site (Kantake et al., 2014). In contrast, DNA methylation between birth and Day 4 post-partum in full-term infants remained stable. In addition, at birth, preterm infants had significantly lower DNA methylation at CpG1, CpG5, and CpG4 when compared to full-term infants. By Day 4 postpartum, DNA methylation at seven CpG sites (15, 16, 21, 25, 26, 27, and 28) were significantly higher in preterm infants when compared to full-term infants (Kantake et al., 2014).

DNA methylation of the HSD11B2 gene between preterm infants who were classified into two groups of neurobehavioral profiles (low and high risk for neurobehavioral complications) were compared in a cross-sectional study (Lester et al., 2015). The high-risk group was found to have lower DNA methylation at CpG3 site of HSD11B2 than infants who were classified as low risk (Lester et al., 2015).

Full-term infants demonstrated higher DNA methylation of PLAGL1, compared to very preterm infants (born before 32 weeks gestation) in a sample of 56 preterm infants and 32 term infants (Provenzi, Carli, et al., 2018). This was shown to be true at both the time of birth and the time of discharge (Provenzi, Carli, et al., 2018).

Finally, only one study examined the entire DNA methylome (Lorente-Pozo et al., 2018). Using repeated measures before and after oxygen administration in the delivery room, the authors identified oxygen loads of >500 mL02/kg were associated with changed methylation patterns in genes associated with the KEGG pathways (Lorente-Pozo et al., 2018).

Effect of Epigenetic Alterations on Neurodevelopmental Outcomes in Preterm Infants

One of the primary studies evaluating SLC6A4 assessed the effect of DNA methylation of SLC6A4 on neurodevelopmental outcomes (Chau et al., 2014). Four additional studies— using the data from Provenzi et al. (2015)—also reported on the associations between DNA methylation of SLC6A4 and neurodevelopmental outcomes (Fumagalli et al., 2018; Montirosso, Provenzi, Fumagalli, et al., 2016; Montirosso, Provenzi, Giorda, et al., 2016; Provenzi et al., 2020). Using repeated measures, the timing of measurement of neurodevelopmental outcomes varied greatly in the studies included in this review. The age when neurodevelopmental outcomes were evaluated ranged from the time of discharge from the NICU to 7 years of life (Chau et al., 2014). Neurodevelopmental outcomes were assessed using different instruments. These included the NICU Network Neurobehavioral Scale (Lester et al., 2015), The Child Behavior Checklist (Chau et al., 2014), the Personal-Social dimension of the Griffith Mental Development Scales (Fumagalli et al., 2018), the Italian version of the Infant Behavior Questionnaire–Revised (Montirosso, Provenzi, Fumagalli, et al., 2016), and the Preschooler Regulation of Emotional Stress procedure (Provenzi et al., 2020).

Increased DNA methylation of SLC6A4 was associated with the following: higher total problems on the Child Behavior Checklist at 7 years of life (Chau et al., 2014); suboptimal social–emotional development at 12 months corrected age (Fumagalli et al., 2018); less sustained attention and slow inhibited approach at 3 months corrected age (Montirosso, Provenzi, Fumagalli, et al., 2016); greater socio-emotional stress sensitivity at 3 months corrected gestational age (Montirosso, Provenzi, Giorda, et al., 2016); and increased anger response to emotion stress at 4.5 years of age (Provenzi et al., 2020). Specifically, increased DNA methylation of SLC6A4 on CpG sites 2, 5, 6, 7, and 9 were associated with altered neurodevelopmental outcomes later in life, including suboptimal social–emotional development and increased anger response to emotional stress (Montirosso, Provenzi, Giorda, et al., 2016; Provenzi et al., 2020). In regression analysis, increased DNA methylation of SLC6A3 was associated with decreased Bayley II mental and motor scores at 24 and 36 months of age (Apron et al., 2018).

The NICU Network Neurobehavioral Scale was used to classify preterm infants into two neurodevelopmental risk profiles (high risk and low risk; Lester et al., 2015). Infants classified in the high-risk profile showed poor attention that required substantial handling, had poor self-regulation, were highly aroused and excitable, showed poor movement quality, and showed substantial signs of stress at the time of discharge from the NICU. These high-risk profile infants demonstrated higher DNA methylation at CpG3 of the NR3C1 gene promoter and lower DNA methylation of CpG3 of the HSD11B2 gene as compared to the low-risk profile infants (Lester et al., 2015).

Measurements of Early Toxic Stress Exposure in the NICU Within the Context of Stress-Related Epigenetic Modifications

Inconsistent measurements of early toxic stress exposure in the NICU were identified in this review. Researchers often considered the presence of NICU hospitalization as a proxy for a measurable stressor (Arpón et al., 2018; Hatfield et al., 2018; Kantake et al., 2014; Lester et al., 2015). Details about the NICU hospitalization, such as FiO2 requirement and gestational age (reflecting the degree of prematurity), were at times used to operationalize the NICU hospitalization as a stressful event (Lorente-Pozo et al., 2018). Painful procedures were also used as a measure for stressful events in the NICU (Chau et al., 2014; Provenzi et al., 2015). In one study, a principal component analysis of selected indexes was used to create a single measurement of NICU stress. Selected indexes (such as skin breaking procedures, total days of ventilation, and presence of sepsis) were identified, leading to a one-factor solution that explained 74% of the variance. This global index was then used as a measure of stress exposure in the NICU (Fumagalli et al., 2018). Another study used the Neonatal Therapeutic Intervention Scoring System, along with other clinical variables (i.e., length of hospitalization and birth gestational age), to create a “low-risk medical cluster” and a “high-risk medical cluster” of preterm infants based on risk for neurodevelopmental outcome. These two clusters were then used to compare methylation patterns and make conclusions about relationships among medical morbidities and DNA methylation of NR3C1 (Giarraputo et al., 2017).

DISCUSSION

The results of this scoping review indicate that early toxic stress exposure during NICU hospitalization experienced by preterm infants may be associated with epigenetic alterations and with altered neurodevelopmental outcomes in preterm infants. However, the lack of standardized measurements of early toxic stress exposure in the NICU has resulted in varied and inconsistent reporting.

Researchers detected DNA methylation changes in five genes (SLC6A4, SLC6A3, NR3C1, HSD11B2, and PLAGL1) in preterm infants who were hospitalized in the NICU. The genes identified in this review are known to be involved in the stress response pathway. A critical component within the stress response pathway is the activation of the negative feedback loop of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis. Initially, the negative feedback loop of the HPA axis adequately regulates the release of cortisol; however, with repeated and prolonged toxic stress exposure, the mechanism becomes dysregulated (Casavant et al., 2019; Montirosso & Provenzi, 2015; Provenzi, Guida, & Montirosso, 2018). Cortisol is an established marker of stress reactivity and is thought to be partially responsible for changes in prefrontal–hypothalamic–amygdala and dopaminergic circuits. These changes, in turn, are thought to influence individual neurodevelopmental outcomes (Smith & Pollak, 2020).

The serotonin promoter gene SLC6A4 is classified as a protein-coding gene and is responsible for encoding the membrane protein that transports serotonin. SLC6A4 has been identified as a germane biomarker for life adversity and is susceptible to stress and trauma throughout the time span (Provenzi, Guida, & Montirosso, 2018). It is associated with obsessive-compulsive disorder and anxiety disorders in children and adults. Specifically, shorter alleles and environment exposures have been associated with greater risk for depression (Abugessaisa & Kasukawa, 2022). Our results indicate increased DNA methylation to be associated with early toxic stress in the two studies examining the SLC6A4 gene (Chau et al., 2014; Provenzi et al., 2015). The SLC6A3 gene is responsible for encoding a dopamine transporter and is part of the sodium- and chloride-dependent neurotransmitter transporter family (Abugessaisa & Kasukawa, 2022; Caspi et al., 2003). Again, increased DNA methylation was identified to be associated with prematurity risk factors (Apron et al., 2018).

The OPRM1 gene is responsible for making mu opioid receptors. It is hypothesized to regulate the transition from acute to chronic pain. Excessive and prolonged pain exposure can elicit a substantial stress response, leading to overactivating and/or blunting of the cortisol-regulating HPA axis (Hatfield et al., 2018). No association in DNA methylation of OPRM1 and painful procedures in preterm infants was identified in our review (Hatfield et al., 2018).

The promoter region 1F of the glucocorticoid receptor gene NR3C1plays a significant role in the biomechanism within the HPA axis for the regulation of cortisol levels in response to acute and chronic stress (Tyrka et al., 2012). Specifically, NR3C1 encodes glucocorticoid receptors to activate transcription and is involved in the inflammatory responses as well as cell proliferation (Abugessaisa & Kasukawa, 2022). Our results indicate a mix of both increased and decreased DNA methylation of the NR3C1 gene in preterm infants with different exposures to early toxic stress (Giarraputo et al., 2017; Kantake et al., 2014; Lester et al., 2015). These contrasting results may be a result of differences in gestational age, inclusion of different medical variables as a measure of stress, and different sources of DNA (blood vs. buccal cells).

The 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 2 (HSD11B2) gene regulates the enzyme that metabolically breaks down cortisol and thus buffering and protecting the infant from damaging effects of excess cortisol (Abugessaisa & Kasukawa, 2022). The CpG3 on the HSD11B2 gene demonstrated decreased DNA methylation in preterm infants at high risk for neurobehavioral complications (Lester et al., 2015). Finally, the PLAGL1 gene is a protein-coding gene that suppresses cell growth. The PLAGL1 gene has been associated with risk of illness and risk for low-birth-weight offspring; it is often silenced in cancer cells and is associated with transient neonatal diabetes mellitus (Abugessaisa & Kasukawa, 2022). Preterm infants, as compared to term infants, demonstrated decreased DNA methylation of PLAGL1 in the one study evaluating this gene (Provenzi, Carli, et al., 2018).

The changes in DNA methylation were noted as early as the fourth day of life (Kantake et al., 2014), at the time of hospital discharge (Fumagalli et al., 2018; Giarraputo et al., 2017; Lester et al., 2015; Montirosso, Provenzi, Giorda, et al., 2016; Provenzi, Carli, et al., 2018; Provenzi et al., 2015), at 3 and 12 months corrected age (Arpón et al., 2018; Montirosso, Provenzi, Fumagalli, et al., 2016), and up to 7 years of age (Chau et al., 2014). Of note, the review findings indicate no difference in DNA methylation between full-term and preterm infants at the time of birth. Considering this lack of difference at the time of birth, researchers in the studies included in this review hypothesized that NICU hospitalization and its related early life toxic stress exposure may contribute to epigenetic alterations in preterm infants. Furthermore, increased SLC6A4 DNA methylation was associated with reduced brain volume at the time of term gestation, which was also associated with reduced personal–social traits at 12 months corrected gestational age (Fumagalli et al., 2018). Although preliminary, this finding is suggestive that epigenetic alterations secondary to early life toxic stress exposure in the NICU may take place during the first critical days of life and may have a lasting effect on future neurodevelopmental outcomes. These findings are surprising considering previous evidence that confirmed gestational age can accurately be estimated using DNA methylation of cord blood (Knight et al., 2016). This discrepancy may be a result of targeted DNA methylation versus whole genome methylation but warrants further investigation.

Interestingly, the only study examining the entire DNA methylome linked oxygen—a very common medication used in the NICU—with changes in methylation of CpGs on multiple genes involved in cell cycle progression (Lorente-Pozo et al., 2018). These findings indicate that the possible epi-genetic changes secondary to common NICU occurrences are vast and largely unknown. Furthermore, these findings indicate a need for discovery-based, whole genome assessments in preterm infants in light of the dearth of information about the physiology of toxic stress in the preterm infants in the NICU.

The relationships described between early toxic stress exposure in the NICU and DNA methylation of different genes are rudimentary. At this time, it is impossible to know whether the stress is from the NICU hospital stay versus the developmental phenomenon that is associated with epigenetic modifications. Perhaps, both factors played a complex role in altering the epigenetic markers. This is an important topic that requires further research. Figure 2 provides a map to guide future research. Specifically, measurements of the genes HSD11B2, SLC6A4, and NR321 at multiple points in time, along with measurements of short- and long-term outcomes in both healthy term infants and preterm infants, will delineate causes of epigenetic modifications.

The lack of valid measurements of neonatal toxic stress employed in neonatal stress research has led to inconsistent descriptions and measures of the early toxic stress experience in this population. Measuring toxic stress in infants in the NICU is often subjective and random, leading to difficulty in interpretation of results. These difficulties are compounded by infants’ low thresholds for tactile and nociceptive stimulation and a lack of reliable instruments (Fitzgerald, 2015). No studies in this review included a valid and reliable instrument to measure stress in the NICU. Although NICU hospitalization poses the risk for early toxic stress exposure, a generalization that toxic stress related to NICU hospitalization is a uniform experience for all preterm infants is limited. Valid measurements of NICU toxic stress are required for individualized patient care and developmental care interventions in the NICU. Furthermore, broad discussions of early toxic stress in the NICU do not allow for the many different potential outcomes each preterm infant possesses at the time of birth, which are affected differently depending on the source of toxic stress in the NICU. There remains a need for common data elements of toxic stress in preterm infants in both research and clinical settings. Future research needs to include focused and detailed information regarding the sources and measurements of toxic stress from NICU hospitalization in preterm infants.

This scoping review has several limitations. First, because measurements of early toxic stress in preterm infants remains ill-defined, there is a potential for underrepresentation of findings in this review. It is possible that studies were excluded that did not explicitly identify early toxic stress but did measures of concepts like parental separation and light and sound exposures. Second, although the results from our Research Question 3 provide additional insights regarding the specific biological, medical, and procedural stressors during the NICU, the results are limited to those included in the context of stress-related epigenetic modifications. Third, methodological issues regarding how and when neurodevelopmental outcomes are measured in relation to methylation of gene remains are inconsistent, making it difficult to confirm a direct linkage between toxic stress and altered neurodevelopmental outcomes. Fourth, only research published in English was included in the search, possibly limiting the number of articles included. Finally, epigenetic modulations secondary to changes in DNA methylation, such as changes in microRNA sequencing, were not included in this review and may limit the detail of the mapping of major concepts.

The early evidence linking epigenetic alterations in pre-term infants secondary to early toxic stress exposure and neurodevelopmental outcomes offer a new biological and behavioral perspective on the health of preterm infants over their lifespans. Thus, this topic remains a research priority and has promising future implications. The emerging knowledge identified in this review is critical to advancing neonatal care and research. The six genes in this review are known to be responsible for regulating serotonin, dopamine, and cortisol, thus potentially affecting infant health, disease, and neurodevelopment. However, the evidence regarding epigenetic alterations secondary to early toxic stress exposure in the NICU remains limited and inconsistent.

Conclusion

It is both a clinical and research priority to identify and confirm the profile of the epigenome and the mechanisms by which early toxic stress in the NICU may lead to epigenetic alterations. Epigenetic alterations are sensitive to environmental exposure and experience. Therefore, we can aim to design and test individualized interventions to facilitate the prevention of pathological epigenetic alterations. Future research needs to include common data elements of early toxic stress exposures in the NICU to create robust transferable data. In addition, more longitudinal data of DNA methylation are needed to generate the data needed to begin targeting the timing stress reducing interventions during and after NICU hospitalization. Addressing these gaps will significantly advance the field of preterm infant epigenetics and provide crucial data to develop these clinical interventions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This article was supported by the National Center for Research Resources and National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health (NIH), through Grant Number UL1TR001436. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. The authors acknowledge Allison Kuhn for her support in creating Figure 2.

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Review manuscripts do not require ethical approval or informed consent.

Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text and are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal’s Web site (www.nursingresearchonline.com).

Contributor Information

Kathryn J. Malin, Marquette University, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, and Neonatal Nurse Practitioner, Children’s Wisconsin, Milwaukee..

Kaboni W. Gondwe, University of Washington, Seattle..

Alissa V. Fial, Marquette University, Milwaukee, Wisconsin..

Rachel Moore, Marquette University, Milwaukee, Wisconsin..

Yvette Conley, University of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania..

Rosemary White-Traut, Children’s Wisconsin, Milwaukee..

Thao Griffith, Loyola University Chicago, Illinois..

REFERENCES

- Abugessaisa I, & Kasukawa T (Eds.) (2022). Practical guide to life science databases. Springer Nature. [Google Scholar]

- Arksey H, & O’Malley L (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8, 19–32. 10.1080/1364557032000119616 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arpón A, Milagro FI, Laja A, Segura V, de Pipaón MS, Riezu-Boj J-I, & Alfredo Martínez J (2018). Methylation changes and pathways affected in preterm birth: A role for SLC6A3 in neurodevelopment. Epigenomics, 10, 91–103. 10.2217/epi-2017-0082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bucci M, Marques SS, Oh D, & Harris NB (2016). Toxic stress in children and adolescents. Advances in Pediatrics, 63, 403–428. 10.1016/j.yapd.2016.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casavant SG, Cong X, Fitch RH, Moore J, Rosenkrantz T, & Starkweather A (2019). Allostatic load and biomarkers of stress in the preterm infant: An integrative review. Biological Research for Nursing, 21, 210–223. 10.1177/1099800418824415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, Sugden K, Moffitt TE, Taylor A, Craig IW, Harrington H, McClay J, Mill J, Martin J, Braithwaite A, & Poulton R (2003). Influence of life stress on depression: Moderation by a polymorphism in the 5-HTT gene. Science, 301, 386–389. 10.1126/science.1083968 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavalli G, & Heard E (2019). Advances in epigenetics link genetics to the environment and disease. Nature, 571, 489–499. 10.1038/s41586-019-1411-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chau CM, Ranger M, Sulistyoningrum D, Devlin AM, Oberlander TF, & Grunau RE (2014). Neonatal pain and COMT Val158Met genotype in relation to serotonin transporter (SLC6A4) promoter methylation in very preterm children at school age. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience, 8, 409. 10.3389/fnbeh.2014.00409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheong JLY, Burnett AC, Treyvaud K, & Spittle AJ (2020). Early environment and long-term outcomes of preterm infants. Journal of Neural Transmission, 127, 1–8. 10.1007/s00702-019-02121-w [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DʼAgata AL, Young EE, Cong X, Grasso DJ, & McGrath JM (2016). Infant medical trauma in the neonatal intensive care unit (IMTN): A proposed concept for science and practice. Advances in Neonatal Care, 16, 289–297. 10.1097/ANC.0000000000000309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan AF, & Matthews MA (2018). Neurodevelopmental outcomes in early childhood. Clinics in Perinatology, 45, 377–392. 10.1016/j.clp.2018.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Metwally DE, & Medina AE (2020). The potential effects of NICU environment and multisensory stimulation in prematurity. Pediatric Research, 88, 161–162. 10.1038/s41390-019-0738-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald M (2015). What do we really know about newborn infant pain? Experimental Physiology, 100, 1451–1457. 10.1113/EP085134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fumagalli M, Provenzi L, De Carli P, Dessimone F, Sirgiovanni I, Giorda R, Cinnante C, Squarcina L, Pozzoli U, Triulzi F, Brambilla P, Borgatti R, Mosca F, & Montirosso R (2018). From early stress to 12-month development in very preterm infants: Preliminary findings on epigenetic mechanisms and brain growth. PLOS ONE, 13, e0190602. 10.1371/journal.pone.0190602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giarraputo J, DeLoach J, Padbury J, Uzun A, Marsit C, Hawes K, & Lester B (2017). Medical morbidities and DNA methylation of NR3C1 in preterm infants. Pediatric Research, 81, 68–74. 10.1038/pr.2016.185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffith T, White-Traut R, & Janusek LW (2020). A behavioral epigenetics model to predict oral feeding skills in preterm infants. Advances in Neonatal Care, 20, 392–400. 10.1097/ANC.0000000000000720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatfield LA, Hoffman RK, Polomano RC, & Conley Y (2018). Epigenetic modifications following noxious stimuli in infants. Biological Research for Nursing, 20, 137–144. 10.1177/1099800417754141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kantake M, Yoshitake H, Ishikawa H, Araki Y, & Shimizu T (2014). Postnatal epigenetic modification of glucocorticoid receptor gene in preterm infants: A prospective cohort study. BMJ Open, 4, e005318. 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-005318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight AK, Craig JM, Theda C, Baekvad-Hansen M, Bybjerg-Grauholm J, Hansen CS, Hollegaard MV, Hougaard DM, Mortensen PB, Weinsheimer SM, Werge TM, Brenn PA, Cubells JF, Newport DJ, Stowe ZN, Cheong JLY, Dalach P, Doyle LW, Loke YJ, … Smith AK (2016). An epi-genetic clock for gestational age at birth based on blood methylation data. Genome Biology, 17, 206. 10.1186/s13059-016-1068-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lester BM, Marsit CJ, Giarraputo J, Hawes K, LaGasse LL, & Padbury JF (2015). Neurobehavior related to epigenetic differences in preterm infants. Epigenomics, 7, 1123–1136. 10.2217/epi.15.63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorente-Pozo S, Parra-Llorca A, Núñez-Ramiro A, Cernada M, Hervás D, Boronat N, Sandoval J, & Vento M (2018). The oxygen load supplied during delivery room stabilization of preterm infants modifies the DNA methylation profile. Journal of Pediatrics, 202, 70–76. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.07.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montirosso R, & Provenzi L (2015). Implications of epigenetics and stress regulation on research and developmental care of preterm infants. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, & Neonatal Nursing, 44, 174–182. 10.1111/1552-6909.12559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montirosso R, Provenzi L, Fumagalli M, Sirgiovanni I, Giorda R, Pozzoli U, Beri S, Menozzi G, Tronick E, Morandi F, Mosca F, & Borgatti R (2016). Serotonin transporter gene (SLC6A4) methylation associates with neonatal intensive care unit stay and 3-month-old temperament in preterm infants. Child Development, 87, 38–48. 10.1111/cdev.12492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montirosso R, Provenzi L, Giorda R, Fumagalli M, Morandi F, Sirgiovanni I, Pozzoli U, Grunau R, Oberlander TF, Mosca F, & Borgatti R (2016). SLC6A4 promoter region methylation and socio-emotional stress response in very preterm and full-term infants. Epigenomics, 8, 895–907. 10.2217/epi-2016-0010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munn Z, Peters MDJ, Stern C, Tufanaru C, McArthur A, & Aromataris E (2018). Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 18, 143. 10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nist MD, Harrison TM, & Steward DK (2019). The biological embedding of neonatal stress exposure: A conceptual model describing the mechanisms of stress-induced neurodevelopmental impairment in preterm infants. Research in Nursing & Health, 42, 61–71. 10.1002/nur.21923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Provenzi L, Carli P, Fumagalli M, Giorda R, Casavant S, Beri S, Citterio A, D’Agata A, Morandi F, Mosca F, Borgatti R, & Montirosso R (2018). Very preterm birth is associated with PLAGL1 gene hypomethylation at birth and discharge. Epigenomics, 10, 1121–1130. 10.2217/epi-2017-0123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Provenzi L, Fumagalli M, Scotto di Minico G, Giorda R, Morandi F, Sirgiovanni I, Schiavolin P, Mosca F, Borgatti R, & Montirosso R (2020). Pain-related increase in serotonin transporter gene methylation associates with emotional regulation in 4.5-year-old preterm-born children. Acta Paediatrica, 109, 1166–1174. 10.1111/apa.15077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Provenzi L, Fumagalli M, Sirgiovanni I, Giorda R, Pozzoli U, Morandi F, Beri S, Menozzi G, Mosca F, Borgatti R, & Montirosso R (2015). Pain-related stress during the neonatal intensive care unit stay and SLC6A4 methylation in very preterm infants. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience, 9, 99. 10.3389/fnbeh.2015.00099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Provenzi L, Guida E, & Montirosso R (2018). Preterm behavioral epigenetics: A systematic review. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 84, 262–271. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2017.08.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith KE, & Pollak SD (2020). Early life stress and development: Potential mechanisms for adverse outcomes. Journal of Neurodevelopment Disorders, 12, 34. 10.1186/s11689-020-09337-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyrka AR, Price LH, Marsit C, Walters OC, & Carpenter LL (2012). Childhood adversity and epigenetic modulation of the leukocyte glucocorticoid receptors: Preliminary findings in healthy adults. PLOS ONE, 7, e30148. 10.1371/journal.pone.0030148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Dokkum NH, de Kroon MLA, Reijneveld SA, & Bos AF (2021). Neonatal stress, health, and development in preterms: A systematic review. Pediatrics, 148, e2021050414. 10.1542/peds.2021-050414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber A, & Harrison TM (2019). Reducing toxic stress in the neonatal intensive care unit to improve infant outcomes. Nursing Outlook, 67, 169–189. 10.1016/j.outlook.2018.11.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.