Abstract

Sarcopenia is defined as decreasing in muscle strength and mass, and dynapenia is defined as decreasing in muscle strength and maintained muscle mass. This study elucidated the prevalence and characteristics of sarcopenia and dynapenia and evaluate in elderly spinal disorders patients. 1039 spinal disorders patients aged ≥ 65 years were included. We measured age, grip strength, muscle mass, spinal sagittal alignment parameters, low back pain (LBP) scores and health-related quality of life (HR-QoL) scores. Based on the previous reports, patients were categorised into normal group: NG, pre-sarcopenia group: PG, dynapenia group: DG, and sarcopenia group: SG. Pre-sarcopenia, dynapenia, and sarcopenia were found in 101 (9.7%), 249 (19.2%), and 91 (8.8%) patients, respectively. The spinal sagittal alignment parameters, trunk muscle mass, LBP, and HR-QoL scores were significantly worse in DG and SG compared with those in PG and NG. Spinal alignment, trunk muscle mass, and clinical outcomes, including LBP and HR-QoL scores, were maintained in the PG and poor in the DG and SG. Thus, intervention for muscle strength may be a treatment option for changes of spinal sagittal alignment and low back pain.

Subject terms: Epidemiology, Neurological disorders

Introduction

Decreasing muscle strength and muscle mass have recently received increasing attention. Rosenberg et al. first reported sarcopenia, defined as loss of muscle strength and muscle mass due to aging1. It has been reported sarcopenia induced to a high risk of mortality and incident disability2. Additionally, sarcopenia showed a significant financial burden, with medical expense for sarcopenia in the US in 2000 amounting to approximately $18.5 billion3. In contrast, dynapenia, a condition in which maintained muscle mass but reduced muscle strength, has also attracted attention. It has also been reported that dynapenia was highly associated with mortality and physical disfuction4, similar to sarcopenia. Moreover, it has been reported that muscle quality and strength, rather than muscle mass, are important clinical findings including mortality risk and physical performance5,6. Therefore, we should pay attention to muscle strength as well as muscle mass when treating patients with musculoskeletal disorders, such as those with spinal diseases.

Regarding the muscle in patients with spinal diseases, the prevalence of sarcopenia was higher in patients with spinal canal stenosis compared to normal subjects7. In addition, the prevalence of sarcopenia was higher in patients with spinal deformity than in those with spinal stenosis8. Regarding clinical findings, patients with spinal diseases with sarcopenia showed poor LBP scores and outcomes after surgery9,10. However, no reports have evaluated spinal alignment or clinical findings in spinal diseases with dynapenia. Determining whether muscle mass or muscle strength is more important would be helpful when treating patients with spinal diseases; however, this remains unclear. In particular, only a few reports focused on the differences between muscle mass and muscle strength as factors affecting clinical findings including spinal alignment and low back pain in elderly. Therefore, we hypothesized that decreased muscle mass or muscle strength affects clinical findings, spinal alignment, and body composition.

For testing this hypothesis, the purpose of the current study were to elucidate the prevalence of sarcopenia and dynapenia and evaluate whether muscle mass or muscle strength affect clinical outcomes such as low back pain (LBP) and spinal sagittal alignment in elderly spinal disorders patients.

Methods

We obtained ethical approval from our institutional review board for the current study. Further, we also conducted the current study according to the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments.

Patients and measurement items

This cross-sectional and observation study was a multicentre involving nine facilities. We included spinal diseases patients aged ≥ 65 years, whose diagnosis were vertebral fractures, spinal stenosis, spinal deformities, spinal tumours, and osteoporosis, in the current study. Because a myelopathy may affect grip strength, we excluded patients with myelopathies such as cervical spondylosis and cervical disc herniation. We reviewed the age, gender, and anamnestic medical past history from the medical charts of all cases. Body composition, grip strength, lateral X-rays of the whole spine including hip joints on the standing position, and clinical findings, including LBP and health-related quality of life (HRQoL) scores, were also evaluated.

Body composition measurements

We assessed several body composition parameters using bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA) methods. MC-780A or MC-980A body composition analyser (Tanita Co., Tokyo, Japan) was used in all cases. Patients with a pacemaker were excluded because the body composition could not be evaluated. Moreover, we excluded data from patients with implant and instrumentation in their body because of their measurement reliability. Next, we calculated several following parameters.

Skeletal muscle mass index (SMI: the corrected appendicular skeletal muscle mass) = appendicular skeletal muscle mass (kg)/(body height(m))2 (kg/m2).

Trunk muscle mass index (TMI: the corrected trunk muscle mass) = Trunk muscle mass (kg)/(body height(m))2 (kg/m2).

Spinal sagittal alignment and clinical outcome evaluation

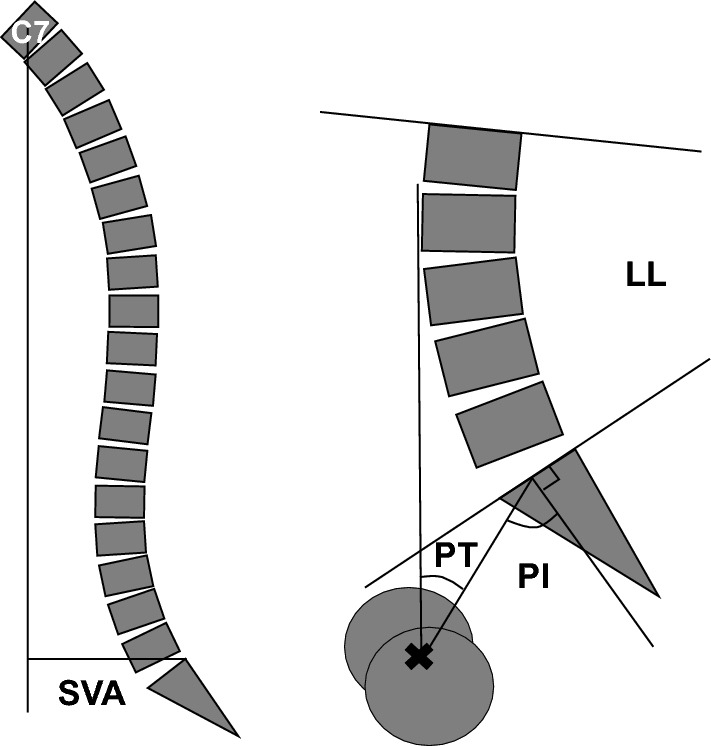

To evaluate spinal sagittal alignment, we evaluated three parameters, including the pelvic tilt (PT), sagittal vertical axis (SVA), and pelvic incidence minus lumbar lordosis (PI − LL), on lateral X-rays of the whole spine including hip joints on the standing position, as previously reported11,12. (Fig. 1) We evaluated LBP scores using the visual analogue scale (VAS) of LBP in the last week and the Oswestry Disability Index (ODI) score. In addition, for evaluating HRQoL, we used the EuroQol 5 Dimension (EQ5D).

Figure 1.

The spinal sagittal alignment measurements. C7 cervical 7, SVA sagittal vertical axis, PT pelvic tilt, PI-LL pelvic incidence minus lumbar lordosis.

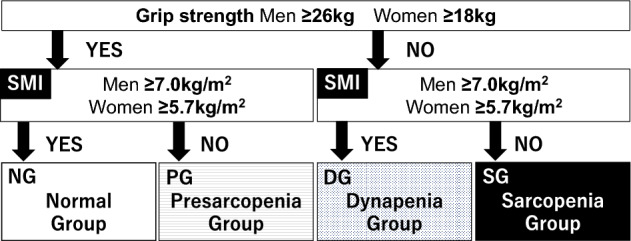

The definition of pre-sarcopenia, dynapenia, and sarcopenia

As previously reported5, we divided patients into four groups: a normal group (NG), comprising normal muscle strength and normal appendicular skeletal muscle mass; a pre-sarcopenia group (PG), comprising normal muscle strength and decreased appendicular skeletal muscle mass; a dynapenia group (DG), comprising decreased muscle strength and normal appendicular skeletal muscle mass; and a sarcopenia group (SG), comprising decreased muscle strength and decreased appendicular skeletal muscle mass. Based on the classification of the Asian Working Group for Sarcopenia13, decreased muscle strength was defined that grip strength was less than 26 kg for men and less than 18 kg for women. Moreover, decreased muscle mass was defined that SMI were less than 7.0 kg/m2 for men and less than 5.7 kg/m2 for women. (Fig. 2). The prevalence of pre-sarcopenia, dynapenia, and sarcopenia was calculated.

Figure 2.

The definitions of pre-sarcopenia, dynapenia, and sarcopenia. SMI Skeletal muscle mass index.

Statistical analysis

As statistical analysis, we performed one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) for comparing the mean of all measurements among the four groups. Then, we performed Post hoc analysis using Tukey’s test for multiple comparisons. We performed these comparisons separately for men and women, since spinal alignment parameters, clinical findings, body composition parameters, and grip strength may differ between the two sexes. We also used Pearson’s correlation coefficients to evaluate the relationships between muscle mass or strength and spinal alignment or clinical outcome. Because muscle mass and strength differ between men and women, we performed these comparisons separately for both sexes. The correlation coefficients were delineated: R-values of 0.2–0.4, 0.4–0.7, and 0.7–1 were considered weak, moderate, and strong correlations, respectively. We analysed all data using IBM SPSS Statistics version 26 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA), and considered significant which a p-value was less than 0.05.

Ethics approval

Ethical approval from the Institutional Review Board of Kitasato University was obtained for this study, which was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles specified in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments. The approval code is B18-086.

Informed consent statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Results

The prevalence of pre-sarcopenia, dynapenia, and sarcopenia

In total, 1039 patients (mean age, 74.6 years; 445 men, 594 women) were analysed in the current study. Among these, 648 (62.4%), 101 (9.7%), 199 (19.2%), and 91 (8.8%) patients were classified into the normal, pre-sarcopenia, dynapenia, and sarcopenia groups, respectively. For men, 326 (73.3%), 46 (10.3%), 52 (11.7%), and 21 (4.7%) patients were classified into the normal, pre-sarcopenia, dynapenia, and sarcopenia groups, respectively. For women, 322 (54.2%), 55 (9.3%), 147 (24.7%), and 70 (11.8%) patients were classified into the normal, pre-sarcopenia, dynapenia, and sarcopenia groups, respectively.

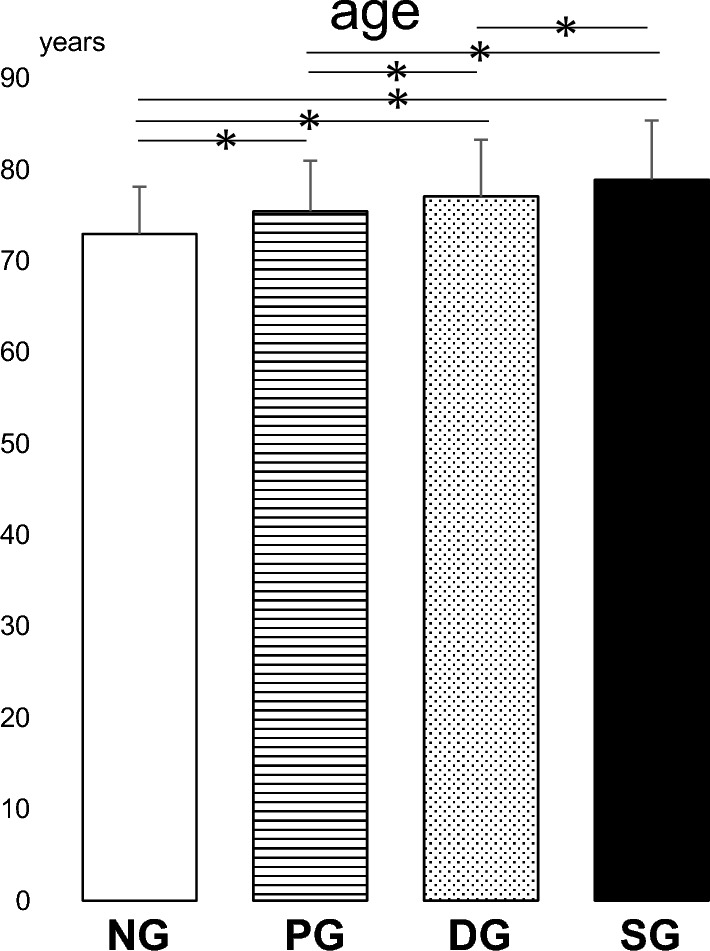

Multiple comparison analysis

Mean age gradually increased in the following order: NG, PG, DG, and SG. The mean ages in SG, DG, and PG were significantly higher than that in NG (p < 0.05). Mean ages in SG and DG were also significantly higher than that in PG (p < 0.05). Furthermore, statistically significantly higher mean age was observed in SG compared with DG. (p < 0.05) (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

The results of the multiple comparison analysis for age among the four groups (NG the normal group, PG pre-sarcopenia group, DG dynapenia group, SG sarcopenia group) are shown. *p < 0.05.

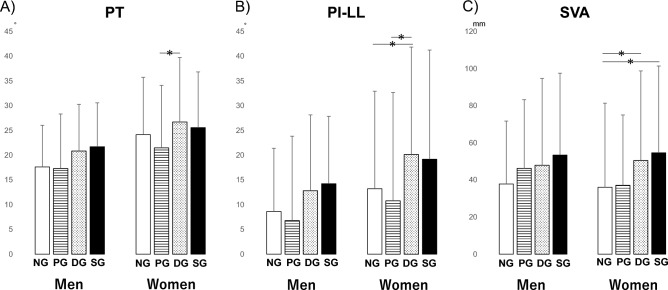

Regarding the spinal sagittal plane alignment, we analyzed the data on men and women separately. Female patients in the DG had a significantly higher PT than those in the NG (p < 0.05) (Fig. 4A). Similarly, significantly higher PI − LL was observed in women in the DG than in the NG (p < 0.05) (Fig. 4B). In addition, female patients in the DG and SG had a significantly higher SVA than those in the NG (p < 0.05) (Fig. 4C).

Figure 4.

The results of the multiple comparison analysis for spinal sagittal alignment parameters among the four groups (NG the normal group, PG pre-sarcopenia group, DG dynapenia group, SG sarcopenia group) are shown. (A) PT pelvic tilt (B) PI − LL pelvic incidence minus lumbar lordosis (C) SVA sagittal vertical axis. *p < 0.05.

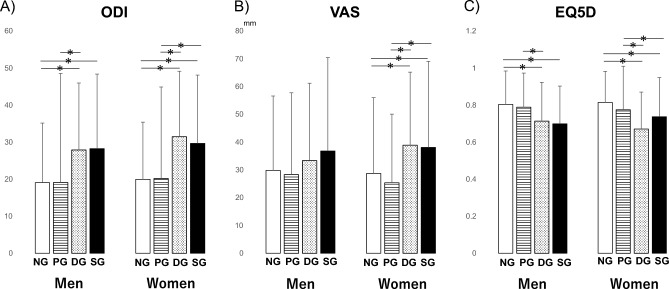

For the clinical findings, similar trends were observed for the ODI, VAS, and EQ5D scores in men and women. For men, the ODI scores in the DG and SG were significantly higher than those in the NG (p < 0.05). In addition, the ODI scores in the DG were significantly higher than those in the PG (p < 0.05). For women, the ODI scores in the DG and SG were significantly higher than those in the NG and PG (p < 0.05) (Fig. 5A). In addition, the VAS scores for LBP in the DG and SG were significantly higher than those in the NG and PG (p < 0.05) (Fig. 5B). For men, the EQ5D scores as HR-QoL scores in the DG and SG were significantly higher than those in the NG (p < 0.05). In addition, the EQ5D scores in the DG were significantly higher than those in the PG (p < 0.05). For women, the EQ5D scores in the DG and SG were significantly higher than those in the NG and PG (p < 0.05) (Fig. 5C).

Figure 5.

The results of the multiple comparison analysis for clinical outcomes among the four groups (NG the normal group, PG pre-sarcopenia group, DG dynapenia group, SG sarcopenia group) are shown. (A) ODI oswestry disability index (B) VAS visual analogue scale of low back pain (C) EQ5D EuroQol 5 dimension. *p < 0.05.

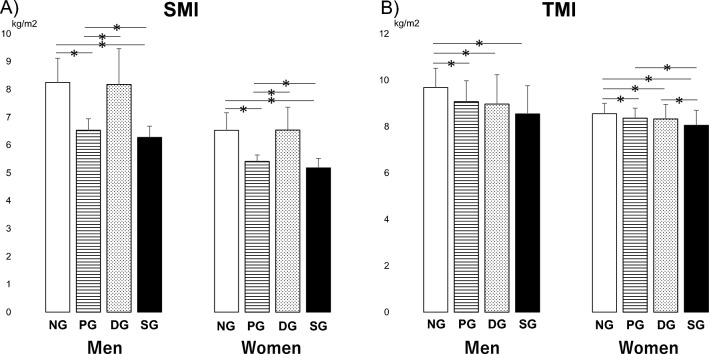

For body composition, we analysed men and women separately. Regarding muscle mass, in both men and women, patients in PG and SG had significantly lower SMI than patients in DG and NG (p < 0.05) (Fig. 6A). However, interestingly, a different tendency was observed for the TMI than for the SMI. In men, patients in PG, DG, and SG had significantly lower TMI compared with patients in NG (p < 0.05). In contrast, no significant difference in the TMI was observed between PG and DG (p > 0.05). In women, patients in PG, DG, and SG had significantly lower TMI compared with patients in NG (p < 0.05). Moreover, the TMI in SG was significantly lower than that in PG and DG (p < 0.05). In contrast, no significant difference in the TMI was observed between PG and DG (p > 0.05) (Fig. 6B).

Figure 6.

The results of the multiple comparison analysis for muscle mass index among the four groups (NG the normal group, PG pre-sarcopenia group, DG dynapenia group, SG sarcopenia group) are shown. (A) SMI Skeletal muscle mass index (B) TMI Trunk muscle mass index. *p < 0.05.

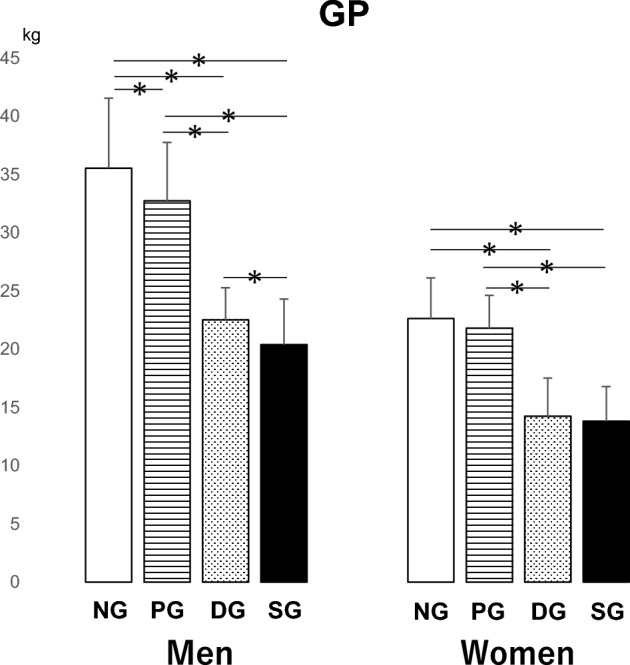

For men, the mean grip strength gradually decreased in the following order: NG, PG, DG, and SG. The mean grip strengths in the SG, DG, and PG were significantly lower than those in the NG (p < 0.05). The mean grip strengths in the SG and DG were also significantly lower than those in the PG (p < 0.05). Furthermore, a statistically significantly lower mean grip strength was observed in the SG than in the DG (p < 0.05). For women, the mean grip strengths in the DG and SG were significantly lower than those in the NG and PG (p < 0.05) (Fig. 7).

Figure 7.

The results of the multiple comparison analysis for grip strength among the four groups (N normal, P pre-sarcopenia, D dynapenia, and S sarcopenia groups) are shown. *p < 0.05.

Table 1 shows the correlations between muscle mass or strength and spinal alignment or clinical outcome. For men, grip strength significantly negatively weakly correlated with PI-LL, SVA, and ODI (r = − 0.208, p = 0.000; r = − 0.217, p = 0.000; and r = − 0.252, p = 0.000, respectively). In addition, a significant positive weak correlation was identified between grip strength and EQ5D (r = 0.227, p = 0.000). For women, grip strength also significantly negatively weakly correlated with PI-LL, SVA, and ODI (r = − 0.239, p = 0.000; r = − 0.224, p = 0.000; and r = − 0.358, p = 0.000, respectively). In addition, a significant positive weak correlation was identified between grip strength and EQ5D (r = 0.227, p = 0.000). A significant positive weak correlation was also found between grip strength and EQ5D (r = 0.351, p = 0.000). In contrast, SMI was not significantly correlated with all spinal sagittal alignment parameters and clinical outcomes for men and women.

Table 1.

The correlations between SMI or grip strength and spinal alignment or clinical outcome.

| PT | PI-LL | SVA | ODI | VAS | EQ5D | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | |||||||

| SMI | r | 0.017 | 0.072 | − 0.013 | − 0.007 | 0.064 | 0.022 |

| P | 0.734 | 0.145 | 0.789 | 0.877 | 0.194 | 0.651 | |

| Grip strength | r | − 0.188 | − 0.208 | − 0.217 | − 0.252 | − 0.081 | 0.227 |

| p | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.098 | 0.000 | |

| Women | |||||||

| SMI | r | 0.065 | 0.006 | 0.031 | 0.007 | 0.017 | − 0.018 |

| p | 0.128 | 0.893 | 0.477 | 0.862 | 0.690 | 0.684 | |

| Grip strength | r | − 0.189 | − 0.239 | − 0.224 | − 0.358 | − 0.182 | 0.351 |

| p | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

Significant values are in bold.

Discussion

In this study, the incidence rates of pre-sarcopenia, dynapenia, and sarcopenia were 9.7%, 19.2%, and 8.8%, respectively, indicating that 37.6% of elderly patients with spinal diseases showed decreased muscle mass or muscle strength. Additionally, the age in PG, DG and SG was significantly higher compared with that in NG. Several authors have reported that decreased muscle strength or mass is highly related with ageing in elderly patients14,15. Additionally, muscle strength decline is more rapid than muscle mass decline14. Petermann-Rocha et al. reported in their systematic review that the incidence of sarcopenia varied between 10 and 27% because subjects, cut-off points, and classifications were different among these studies16. These findings indicated that there were unexpectedly many patients with spinal diseases with decreased muscle mass or strength. In addition, ageing may be a risk factor for loss of muscle strength and mass.

Regarding spinal alignment, in the current study, the groups with decreased muscle strength, not the pre-sarcopenia group showing decreased muscle mass, showed changes of spinal sagittal alignment compared to the normal. In addition, several spinal sagittal alignment parameters, including PI-LL and SVA, significantly correlated with grip strength but not with SMI. Several authors have reported that decreased appendicular skeletal muscle mass was related with spinal sagittal malalignment in spinal diseases patients17–19. In addition, a previous report showed that low trunk muscle mass and grip strength might be risk factors for spinal malalignment in spinal diseases patients20. Thus, muscle strength as well as muscle mass were associated with spinal sagittal alignment. However, there were few reports to elucidate which of muscle mass or strength was strongly associated with spinal alignment. Kudo et al. reported that back extensor muscle strength and quality, but not appendicular skeletal muscle mass, was related with spinal sagittal alignment in elderly patients21. Based on these findings from the current study and previous reports, muscle strength, rather than appendicular skeletal muscle mass, might be more strongly associated with spinal sagittal alignment.

For the LBP scores and HRQoL score, similar to results from spinal alignment, the groups that showed decreased muscle strength, not the pre-sarcopenia group, had deteriorated LBP score including ODI ans VAS of LBP and EQ5D score than the normal. The ODI and EQ5D also significantly correlated with grip strength but not SMI. Spinal alignment may be strongly associated with clinical findings. Matsuyama stated in his review that patients with spinal sagittal malalignment usually have various disabilities due to LBP22. In addition, several spinal sagittal alignment parameters have been reported to be strongly associated with HRQoL scores23–25. In another previous report, patients with osteoporosis and spinal sagittal malalignment showed deteriorated LBP scores26. Moreover, it has been reported that improving spinal sagittal alignment after corrective surgery improved the HRQoL scores27. These findings from the previous reports indicated decreasing muscle strength as well as muscle mass were associated with changes of spinal sagittal alignment leading to low back pain. However, there were no reports to demonstrate which of muscle strength or muscle mass would be important for low back pain. Cobmined with findings from the present study, it was suggested that decreasing muscle strength, but not loss of muscle mass, might cause the deterioration of clinical findings, including LBP and HRQoL, via the deterioration of spinal alignment.

In this study, patients in the dynapenia group with decreased muscle strength had significantly lower trunk muscle mass than patients in the normal group, although the appendicular skeletal muscle mass was preserved. Thus, trunk muscle mass, rather than appendicular skeletal muscle mass, may be important, especially in spinal diseases patients. Yamamoto et al. reported that a low trunk muscle mass was related with hyperkyphosis but not appendicular skeletal muscle mass28. A previous report indicated the trunk muscle mass was significantly related with spinal alignment, ODI scores, and EQ5D scores when adjusted for appendicular skeletal muscle mass29. Furthermore, a decreased trunk muscle mass might be a possible risk factor for LBP in osteoporosis patients30. Thus, trunk muscles might be an important factor for maintaining posture and improving clinical findings and should be considered when treating patients with spinal diseases.

The finding of the current study that muscle strength and trunk muscle mass, rather than appendicular skeletal muscle mass, might affect spinal sagittal alignment, LBP, and HRQoL is of clinical relevance. Several authors reported that even if muscle mass was lost, mortality was not increased if the muscle strength was maintained31,32. In addition, it has been reported exercise therapy had a positive effect on muscle strength, but there is insufficient evidence for muscle mass33. Therefore, exercise therapy for muscle strength may be important for treating patients with spinal diseases.

There were some limitations in the current study. First, this study was a cross-sectional study, and it was unclear whether muscle strength affects spinal alignment and clinical findings or whether spinal alignment and clinical findings affect muscle strength. A longitudinal study is needed in the future to evaluate these aspects. Second, other factors, such as vertebral fractures, may be related with body composition and spinal sagittal alignment. Nevertheless, we did not evaluate vertebral fractures in this study. Thus, some measurements, including the BMI, SMI, and TMI, might be overestimated in patients with vertebral fractures because body height might be underestimated in these patients. However, the method to correct this body composition remains unclear. Therefore, muscle mass can be compared without body height correction, and further longitudinal studies should be conducted in the future. Third, we were concerned about the accuracy of the measurement of trunk muscle mass using BIA because it included visceral and cardiac muscles. However, spinal alignment parameters and low back pain scores have been associated with trunk muscle mass, which was measured by BIA, but not skeletal muscle mass in patients with spinal diseases29. Therefore, the measurement of trunk muscle mass using BIA is worth evaluating, especially in studies of patients with spinal diseases. Fourth, we did not the measure trunk muscle strength. A discrepancy may exist between the tendency of grip strength and trunk muscle strength. Measuring the trunk muscle strength as well as grip strength may be important for evaluating spinal sagittal alignment and LBP, especially in patients with spinal diseases. Further studies are needed.

In conclusion, the current study showed that approximately 20% and 10% of the patients with spinal disorders had dynapenia and sarcopenia, respectively. In addition, patients with low muscle strength had low trunk muscle mass, poor outcomes of LBP, poor HRQoL, changes of spinal sagittal alignment, but elderly patients with low appendicular skeletal muscle mass alone did not. Thus, interventions for muscle strength may be a treatment option for changes of spinal sagittal alignment and LBP.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Motoki Makabe, Yukie Arai, Kazue Takakura and Ikumi Sekihara for their assistance with this study and Honyaku Center Inc. for English language editing.

Author contributions

T.Y. and M.M. drafted the manuscript and participated in the study design. I.G., H.Y. and I.K. helped revise the manuscript; M.K., F.H., K.A., Y.Y., I.S., M.Y., T.S., O.S., T.H., H.M., S.A., T.T., T.H., O.S., E.Y., S.Y., F.T. and M.S. collected the clinical data; I.S., S.E., I.T., N.T. and K.U. performed the data analysis; and O.S., N.H. and T.M. conceived the study and participated in its design and coordination. All the authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This investigation was partly supported by JOA-Subsidized Science Project Research 2018-2.

Data availability

The data are available on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Rosenberg IH. Sarcopenia: Origins and clinical relevance. J. Nutr. 1997;127:990s–991s. doi: 10.1093/jn/127.5.990S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kitamura A, Seino S, Abe T, Nofuji Y, Yokoyama Y, Amano H, Nishi M, Taniguchi Y, Narita M, Fujiwara Y, Shinkai S. Sarcopenia: Prevalence, associated factors, and the risk of mortality and disability in Japanese older adults. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2021;12:30–38. doi: 10.1002/jcsm.12651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Janssen I, Shepard DS, Katzmarzyk PT, Roubenoff R. The healthcare costs of sarcopenia in the United States. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2004;52:80–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52014.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clark BC, Manini TM. Functional consequences of sarcopenia and dynapenia in the elderly. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care. 2010;13:271–276. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0b013e328337819e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yamada M, Kimura Y, Ishiyama D, Nishio N, Abe Y, Kakehi T, Fujimoto J, Tanaka T, Ohji S, Otobe Y, Koyama S, Okajima Y, Arai H. Differential characteristics of skeletal muscle in community-dwelling older adults. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2017;18:807.e809–807.e816. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2017.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Newman AB, Kupelian V, Visser M, Simonsick EM, Goodpaster BH, Kritchevsky SB, Tylavsky FA, Rubin SM, Harris TB. Strength, but not muscle mass, is associated with mortality in the health, aging and body composition study cohort. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2006;61:72–77. doi: 10.1093/gerona/61.1.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Park S, Kim HJ, Ko BG, Chung JW, Kim SH, Park SH, Lee MH, Yeom JS. The prevalence and impact of sarcopenia on degenerative lumbar spinal stenosis. Bone Joint J. 2016;98-b:1093–1098. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.98b8.37623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eguchi Y, Suzuki M, Yamanaka H, Tamai H, Kobayashi T, Orita S, Yamauchi K, Suzuki M, Inage K, Fujimoto K, Kanamoto H, Abe K, Aoki Y, Toyone T, Ozawa T, Takahashi K, Ohtori S. Associations between sarcopenia and degenerative lumbar scoliosis in older women. Scoliosis Spinal Disord. 2017;12:9. doi: 10.1186/s13013-017-0116-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Matsuo S, Kawakami M, Minetama M, Nakagawa M, Teraguchi M, Kagotani R, Mera Y, Yamamoto Y, Sakon N, Nakatani T, Sumiya T, Nakagawa Y. Clinical features of sarcopenia in patients with lumbar spinal stenosis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2020;45:1105–1110. doi: 10.1097/brs.0000000000003498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Inose H, Yamada T, Hirai T, Yoshii T, Abe Y, Okawa A. The impact of sarcopenia on the results of lumbar spinal surgery. Osteoporos Sarcopenia. 2018;4:33–36. doi: 10.1016/j.afos.2018.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Van Royen BJ, Toussaint HM, Kingma I, Bot SD, Caspers M, Harlaar J, Wuisman PI. Accuracy of the sagittal vertical axis in a standing lateral radiograph as a measurement of balance in spinal deformities. Eur. Spine J. 1998;7:408–412. doi: 10.1007/s005860050098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Duval-Beaupère G, Schmidt C, Cosson P. A Barycentremetric study of the sagittal shape of spine and pelvis: The conditions required for an economic standing position. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 1992;20:451–462. doi: 10.1007/bf02368136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen LK, Woo J, Assantachai P, Auyeung TW, Chou MY, Iijima K, Jang HC, Kang L, Kim M, Kim S, Kojima T, Kuzuya M, Lee JSW, Lee SY, Lee WJ, Lee Y, Liang CK, Lim JY, Lim WS, Peng LN, Sugimoto K, Tanaka T, Won CW, Yamada M, Zhang T, Akishita M, Arai H. Asian working group for sarcopenia: 2019 consensus update on sarcopenia diagnosis and treatment. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2020;21:300–307.e302. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2019.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goodpaster BH, Park SW, Harris TB, Kritchevsky SB, Nevitt M, Schwartz AV, Simonsick EM, Tylavsky FA, Visser M, Newman AB. The loss of skeletal muscle strength, mass, and quality in older adults: The health, aging and body composition study. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2006;61:1059–1064. doi: 10.1093/gerona/61.10.1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Koster A, Ding J, Stenholm S, Caserotti P, Houston DK, Nicklas BJ, You T, Lee JS, Visser M, Newman AB, Schwartz AV, Cauley JA, Tylavsky FA, Goodpaster BH, Kritchevsky SB, Harris TB. Does the amount of fat mass predict age-related loss of lean mass, muscle strength, and muscle quality in older adults? J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2011;66:888–895. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glr070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Petermann-Rocha F, Balntzi V, Gray SR, Lara J, Ho FK, Pell JP, Celis-Morales C. Global prevalence of sarcopenia and severe sarcopenia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2022;13:86–99. doi: 10.1002/jcsm.12783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eguchi Y, Suzuki M, Yamanaka H, Tamai H, Kobayashi T, Orita S, Yamauchi K, Suzuki M, Inage K, Fujimoto K, Kanamoto H, Abe K, Norimoto M, Umimura T, Aoki Y, Koda M, Furuya T, Toyone T, Ozawa T, Takahashi K, Ohtori S. Influence of skeletal muscle mass and spinal alignment on surgical outcomes for lumbar spinal stenosis. Asian Spine J. 2018;12:556–562. doi: 10.4184/asj.2018.12.3.556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hiyama A, Katoh H, Sakai D, Sato M, Tanaka M, Nukaga T, Watanabe M. Correlation analysis of sagittal alignment and skeletal muscle mass in patients with spinal degenerative disease. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:15492. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-33867-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kwon JW, Lee BH, Sung S, Lee SB, Park MS, Cho JH, Yang JH, Lee HM, Moon SH. Hand grip strength as a surrogate marker for postoperative changes in spinopelvic alignment in patients with lumbar spinal stenosis. Sci. Rep. 2020;10:13432. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-70357-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miyagi M, Inoue G, Hori Y, Inage K, Murata K, Kawakubo A, Fujimaki H, Koyama T, Yokozeki Y, Mimura Y, Takahashi S, Ohyama S, Terai H, Hoshino M, Suzuki A, Tsujio T, Dohzono S, Sasaoka R, Toyoda H, Orita S, Eguchi Y, Shiga Y, Furuya T, Maki S, Shirasawa E, Saito W, Imura T, Nakazawa T, Uchida K, Ohtori S, Nakamura H, Takaso M. Decreased muscle mass and strength affected spinal sagittal malalignment. Eur. Spine J. 2022;31:1431–1437. doi: 10.1007/s00586-022-07151-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kudo D, Miyakoshi N, Hongo M, Kasukawa Y, Ishikawa Y, Mizutani T, Mizutani Y, Shimada Y. Impact of appendicular and trunk skeletal muscle mass and back extensor strength on sagittal spinal alignment in Japanese women without vertebral fracture. Osteoporos Sarcopenia. 2021;7:36–41. doi: 10.1016/j.afos.2021.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Matsuyama Y. Surgical treatment for adult spinal deformity: Conceptual approach and surgical strategy. Spine Surg. Relat. Res. 2017;1:56–60. doi: 10.22603/ssrr.1.2016-0036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lafage V, Schwab F, Patel A, Hawkinson N, Farcy JP. Pelvic tilt and truncal inclination: Two key radiographic parameters in the setting of adults with spinal deformity. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2009;34(E599):606. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181aad219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Glassman SD, Bridwell K, Dimar JR, Horton W, Berven S, Schwab F. The impact of positive sagittal balance in adult spinal deformity. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2005;30:2024–2029. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000179086.30449.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schwab F, Ungar B, Blondel B, Buchowski J, Coe J, Deinlein D, DeWald C, Mehdian H, Shaffrey C, Tribus C, Lafage V. Scoliosis Research Society-Schwab adult spinal deformity classification: A validation study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2012;37:1077–1082. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31823e15e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Matsunaga T, Miyagi M, Nakazawa T, Murata K, Kawakubo A, Fujimaki H, Koyama T, Kuroda A, Yokozeki Y, Mimura Y, Shirasawa E, Saito W, Imura T, Uchida K, Nanri Y, Inage K, Akazawa T, Ohtori S, Takaso M, Inoue G. Prevalence and characteristics of spinal sagittal malalignment in patients with osteoporosis. J. Clin. Med. 2021 doi: 10.3390/jcm10132827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miyakoshi N, Hongo M, Kobayashi T, Abe T, Abe E, Shimada Y. Improvement of spinal alignment and quality of life after corrective surgery for spinal kyphosis in patients with osteoporosis: A comparative study with non-operated patients. Osteoporos Int. 2015;26:2657–2664. doi: 10.1007/s00198-015-3163-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yamamoto J, Bergstrom J, Davis A, Wing D, Schousboe JT, Nichols JF, Kado DM. Trunk lean mass and its association with 4 different measures of thoracic kyphosis in older community dwelling persons. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0174710. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0174710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hori Y, Hoshino M, Inage K, Miyagi M, Takahashi S, Ohyama S, Suzuki A, Tsujio T, Terai H, Dohzono S, Sasaoka R, Toyoda H, Kato M, Matsumura A, Namikawa T, Seki M, Yamada K, Habibi H, Salimi H, Yamashita M, Yamauchi T, Furuya T, Orita S, Maki S, Shiga Y, Inoue M, Inoue G, Fujimaki H, Murata K, Kawakubo A, Kabata D, Shintani A, Ohtori S, Takaso M, Nakamura H. ISSLS PRIZE IN CLINICAL SCIENCE 2019: Clinical importance of trunk muscle mass for low back pain, spinal balance, and quality of life-a multicenter cross-sectional study. Eur. Spine J. 2019;28:914–921. doi: 10.1007/s00586-019-05904-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miyagi M, Inoue G, Murata K, Koyama T, Kuroda A, Kawakubo A, Yokozeki Y, Mimura Y, Nanri Y, Inage K, Akazawa T, Ohtori S, Uchida K, Takaso M. Factors associated with pain-related disorders and gait disturbance scores from the Japanese orthopedic association back pain evaluation questionnaire and Oswestry Disability Index in patients with osteoporosis. Arch. Osteoporos. 2021;17:1. doi: 10.1007/s11657-021-01045-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Visser M, Goodpaster BH, Kritchevsky SB, Newman AB, Nevitt M, Rubin SM, Simonsick EM, Harris TB. Muscle mass, muscle strength, and muscle fat infiltration as predictors of incident mobility limitations in well-functioning older persons. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2005;60:324–333. doi: 10.1093/gerona/60.3.324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bianchi L, Ferrucci L, Cherubini A, Maggio M, Bandinelli S, Savino E, Brombo G, Zuliani G, Guralnik JM, Landi F, Volpato S. The predictive value of the EWGSOP definition of sarcopenia: Results from the InCHIANTI study. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2016;71:259–264. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glv129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Escriche-Escuder A, Fuentes-Abolafio IJ, Roldán-Jiménez C, Cuesta-Vargas AI. Effects of exercise on muscle mass, strength, and physical performance in older adults with sarcopenia: A systematic review and meta-analysis according to the EWGSOP criteria. Exp. Gerontol. 2021;151:111420. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2021.111420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data are available on reasonable request to the corresponding author.