SUMMARY

Background:

Medications taken during pregnancy can impact maternal and child health outcomes, but few studies have compared the safety and virologic efficacy of different antiretrovirals. We here report the primary safety outcomes from enrolment through 50 weeks postpartum and secondary virologic efficacy outcome at 50 weeks postpartum of the following commonly used antiretroviral treatment (ART) regimens for HIV-1: dolutegravir plus emtricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide fumarate; dolutegravir plus emitricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate; or efavirenz efavirenz/emitricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate, started in pregnancy.

Methods:

In this multisite trial, we randomised women living with HIV between 14 and 28 weeks of gestation at 22 clinical research sites in nine countries (Botswana, Brazil, India, South Africa, Tanzania, Thailand, Uganda, the USA, and Zimbabwe) to start one of three oral regimens: dolutegravir+emitricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide; dolutegravir+emitricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate; or efavirenz/emitricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate. Up to 14 days of antepartum ART prior to enrollment was permitted. Women with known multiple gestation, fetal anomalies, acute significant illness, transaminases ≥2.5 times the upper limit of normal, or estimated creatinine clearance <60 mL/minute were excluded. Primary safety analyses of maternal and infant grade 3 or higher adverse events through 50 weeks postpartum were pairwise comparisons of proportions between ART regimens. Secondary efficacy analyses at 50 weeks postpartum included comparison of the proportion of women with HIV-1 RNA <200 copies per mL in the combined dolutegravir-containing groups versus the efavirenz-containing group. This trial was registered with ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT03048422.

Findings:

From Jan 19, 2018 through Feb 08, 2019, we randomized 643 pregnant women: 217 (34%) to dolutegravir+emitricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide, 215 (33%) to dolutegravir+emitricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate, and 211 (33%) to efavirenz/emitricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate. Median values at enrolment were gestational age 21.9 weeks (IQR 18.3– 25.3), CD4 count 466 cells per uL (IQR 308–624), and HIV-1 RNA 903 copies per mL (IQR 152·0–5182·5). Most (532 [83%] of 643) women briefly took non-study ART while being screened for enrollment, as permitted per protocol (for median of 6 days). Six hundred and seven (94%) women and 566 (92%) of 617 liveborn infants completed the study. There were no differences through week 50 postpartum visit in the probability of mothers or infants experiencing a grade 3 or higher adverse event between the three treatment groups. Death through postnatal week 50 visit was more common among liveborn infants whose mothers were in the efavirenz-containing group (n=14, 7%) compared to the combined dolutegravir-containing groups (n=6, 1%). Five hundred and seventy-three (89%) women had HIV-1 RNA data available at 50 weeks postpartum: 366 (96%) in the dolutegravir-containing groups and 186 (96%) in the efavirenz-containing group had HIV-1 RNA <200 copies per mL (difference [95% CI]: −0.1% [−3.3% to 3.2%], p-value = 0.97). Virologic failure was more frequent in the efavirenz-containing group (10%) than in the combined dolutegravir-containing groups (5%); 14 women in the efavirenz-containing group (and no women in the dolutegravir-containing groups) changed their regimen due to virologic failure and/or drug resistance.

Interpretation:

In our study, the safety and efficacy data from the entire antepartum through postpartum study follow-up period support the current recommendation of dolutegravir-based ART (particularly in combination with emitricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide) to efavirenz/emitricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate when started in pregnancy.

Funding:

National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, and the National Institute of Mental Health.

BACKGROUND

Antiretroviral therapy (ART) during pregnancy is critical to both the health of women with HIV and for preventing vertical transmission of HIV. The optimal first-line ART regimen in this context must balance both antiviral efficacy and safety outcomes.1–3 However, high quality comparative data for maternal and infant safety and efficacy outcomes for ART regimens used in pregnancy (and during lactation) are scarce for most antiretrovirals.

In 2018, WHO guidelines for first-line ART treatment of adults (including those who are pregnant) replaced efavirenz with dolutegravir, a potent and well-tolerated integrase inhibitor with a high genetic barrier to drug resistance.3 While these guidelines continue to recommend tenofovir disoproxil fumarate as a component of first-line ART, several countries have begun to prescribe tenofovir alafenamide fumarate in its place. With similar efficacy to tenofovir disoproxil fumarate, tenofovir alafenamide has less renal and bone toxicity and is less costly to manufacture.4–6 Previous studies have shown greater weight gain in non-pregnant adults starting dolutegravir-based ART (particularly in combination with tenofovir alafenamide) compared with efavirenz-based ART,7 and have also raised the concern for possible increased neural tube defect risk with first trimester dolutegravir use8 (a risk that has not been confirmed with larger datasets).9,10 We conducted the IMPAACT 2010 (or Virologic Efficacy and Safety of ART Combinations with tenofovir alafenamide/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate, efavirenz, and dolutegravir [VESTED]) trial to compare the safety and virologic efficacy of dolutegravir- and tenofovir alafenamide-containing ART in pregnancy. Results through delivery showed that when started in pregnancy, dolutegravir-containing ART had superior antiviral efficacy at delivery compared with the efavirenz-containing ART, and that dolutegravir+emitricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide had the lowest rate of composite adverse pregnancy outcomes and of neonatal deaths.11 Here we report virologic efficacy and maternal and infant safety outcomes during the entire study period, from antepartum enrolment through 50 weeks postpartum.

METHODS

Study design and participants

VESTED was a Phase III open-label randomised trial conducted at 22 clinical research sites in nine countries (Botswana, Brazil, India, South Africa, Tanzania, Thailand, Uganda, the United States, and Zimbabwe). We enrolled pregnant women aged ≥18 years with confirmed HIV-1 infection at 14 to 28 weeks of gestation. Women were ART-naïve with the following exceptions permitted: up to 14 days of ART use during the current pregnancy but before enrollment (in order to not delay ART initiation during screening for the study); previous tenofovir disoproxil fumarate or tenofovir disoproxil fumarate /emitricitabine pre-exposure prophylaxis; or ART during prior pregnancies or breastfeeding if the last dose was taken ≥6 months before study entry. We excluded women whose screening ultrasound revealed multiple gestation or fetal anomalies. We also excluded women with psychiatric illness (if currently on medication or history of suicidal ideation), women hospitalised or with acute significant illness in preceding 14 days, and women with active tuberculosis, serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) or aspartate aminotransferase (AST) ≥2.5 times the upper limit of normal, or estimated creatinine clearance <60 mL/minute.11 Women and infants were followed through 50 weeks postpartum.

Randomisation and masking

We randomly assigned eligible women (1:1:1) to receive either dolutegravir+emitricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide, dolutegravir+emitricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate, or efavirenz/emitricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate. Randomization was stratified by gestational age (14–18, 19–23, 24–28 weeks’ gestation) and by country. Permuted blocks of size six were generated by central computerized randomisation. Local study staff and participants were unmasked to study treatment assignment. The statisticians had access to unmasked data.

Study procedures and study ART regimens

Participants underwent obstetric ultrasound before or within 14 days after enrollment, which contributed to gestational age estimation using the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists algorithm.12 Following randomisation, women had scheduled study visits every four weeks during pregnancy, at delivery, and at 6, 14, 26, 38, and 50 weeks postpartum. From Mar 31, 2020, the visit window for the remaining week 50 postpartum visits was expanded to 38–74 weeks after pregnancy outcome instead of 44–56 weeks accommodate site COVID-19 restrictions. With the exceptions of infant HIV infections and deaths, and virologic failures, analyses presented here only include data from within the original +/−6 week visit window. Maternal HIV-1 RNA (Abbott RealTime HIV-1 Viral Load assay; Abbott Molecular, Des Plaines, IL, USA), ALT, AST, and creatinine were measured before randomisation and regularly throughout follow-up. In infants, HIV-1 nucleic acid test (RNA or DNA), ALT, creatinine, and complete blood count were performed at the birth visit (and at 26 weeks, in breastfeeding infants). HIV-1 nucleic acid test was also performed at 6, 14, and 50 weeks of age in all infants (and at 26 and 38 weeks in breastfeeding infants).

Maternal participants received either once-daily oral dolutegravir 50 mg, and once-daily oral fixed-dose combination emitricitabine 200 mg and tenofovir alafenamide 25 mg; once-daily oral dolutegravir 50 mg, and once-daily oral fixed-dose combination emitricitabine 200 mg and tenofovir disoproxil fumarate 300 mg; or once-daily oral fixed-dose combination of efavirenz 600 mg, emitricitabine 200 mg, and tenofovir disoproxil fumarate 300 mg. Infants received non-study antiretroviral prophylaxis and infant feeding consistent with the local standard of care of each participating research site.

We defined viral suppression as plasma HIV-1 RNA <200 copies per mL. In cases of virologic failure (defined as 2 successive HIV-1 RNA ≥200 copies per mL, with specimen collection for the first test occurring at or after 24 weeks on study) or drug toxicity, site investigators consulted with the study’s Clinical Management Committee for alternative antiretroviral regimens using both study-provided and non-study provided antiretrovirals. In participants with virologic failure, samples from confirmation-of-failure and screening visits were sent to Virology Quality Assurance (VQA)-approved laboratories for genotypic HIV drug resistance testing with results made available to study sites for clinical management.

Study outcomes

In this paper, we report maternal and infant results through 50 weeks postpartum. The pre-specified primary objectives through 50 weeks postpartum were occurrence of maternal grade 3 or higher adverse events (AE) and of infant grade 3 or higher AE (clinical or laboratory, regardless of relatedness to study drug) using the Division of AIDS grading tables.13 The maternal primary safety outcomes included maternal follow-up time from randomization during pregnancy to 50 weeks postpartum.

Postpartum virologic efficacy analyses were pre-specified secondary objectives that included all data from enrollment through the end of follow-up, and were comprised of the following at 50 weeks postpartum: the proportions of women with viral suppression in the dolutegravir-containing groups (combined) vs. the efavirenz group; and the proportions of women with HIV-1 RNA <200 copies per mL using the FDA snapshot algorithm,14 compared pairwise between the 3 groups (and the combined dolutegravir-containing groups vs. the efavirenz group). We also performed a post hoc pairwise comparison of virologic failure. HIV drug resistance was defined as the presence of one or more drug resistance mutations conferring low-, intermediate-, or high-level resistance in VQA-approved laboratories, using the Stanford University HIV Drug Resistance Database version 9.0.15

We defined the secondary outcome of infant HIV infection as two positive HIV-1 nucleic acid tests from different dates or a single positive test in an infant who died before subsequent testing. Other secondary outcomes included infant mortality, and maternal weight change between enrollment and 50 weeks postpartum.

Statistical analysis

We selected a sample size of 639 pairs to provide 80% power for a −10% non-inferiority margin for virologic efficacy at delivery of the combined dolutegravir-containing groups versus the efavirenz/emitricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate group, assuming 10% of data for the primary outcomes would be missing. For the maternal primary safety outcome: with 213 women per group, assuming 15% of women on the efavirenz-containing regimen would experience a grade 3 or higher AE through 50 weeks postpartum, the study had 80% power to detect absolute outcome percentages of 27% vs. 15% and 6% vs. 15%. For the infant primary safety outcome: assuming 25% of infants in the maternal efavirenz-containing group would experience a grade 3 or higher AE through 50 weeks of age, we had 80% power to detect absolute percentages of 38% vs. 25% and 14% vs. 25%.

We analysed binary outcomes with two-sample tests of proportions with normal approximation and continuous outcomes with two-sample t-test assuming unequal variance. For primary safety outcomes and secondary outcomes of infant death and HIV infection, analyses were based on pairwise differences in Kaplan-Meier estimates of the incident probabilities of experiencing an event through 50 weeks postpartum, using Greenwood’s standard error.16 We analysed average weekly maternal weight change through 50 weeks postpartum longitudinally using generalised estimating equations with an identity link, an exchangeable working correlation matrix, and main effects for study-time and group plus a study-time by group interaction term. We conducted post hoc pairwise between-arm comparisons of proportions of women with obesity (body mass index [BMI] ≥30 kg/m2) at 50 weeks postpartum. We used the Wald test for by-arm differences of proportions of participants with drug resistance.

We performed all comparisons using the intention-to-treat principle, which included all randomised participants with available data. P-values were 2-sided, and we considered p-values <0·05 as statistically significant. We made no adjustments for multiple comparisons. We performed all analyses using SAS Version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Trial ethics and oversight

Each participating site received study approval from the appropriate research ethics authorities in the respective country. All maternal participants provided written informed consent. The study was monitored by an independent data and safety monitoring board and registered with ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT03048422.

Role of the funding source

The U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) funded the trial. Gilead Sciences, ViiV Healthcare, and Mylan Pharmaceuticals donated the study drugs. Representatives of the U.S. NIH and pharmaceutical companies participated in the study design and writing of the report, but had no role in data collection, data analysis, or data interpretation.

RESULTS

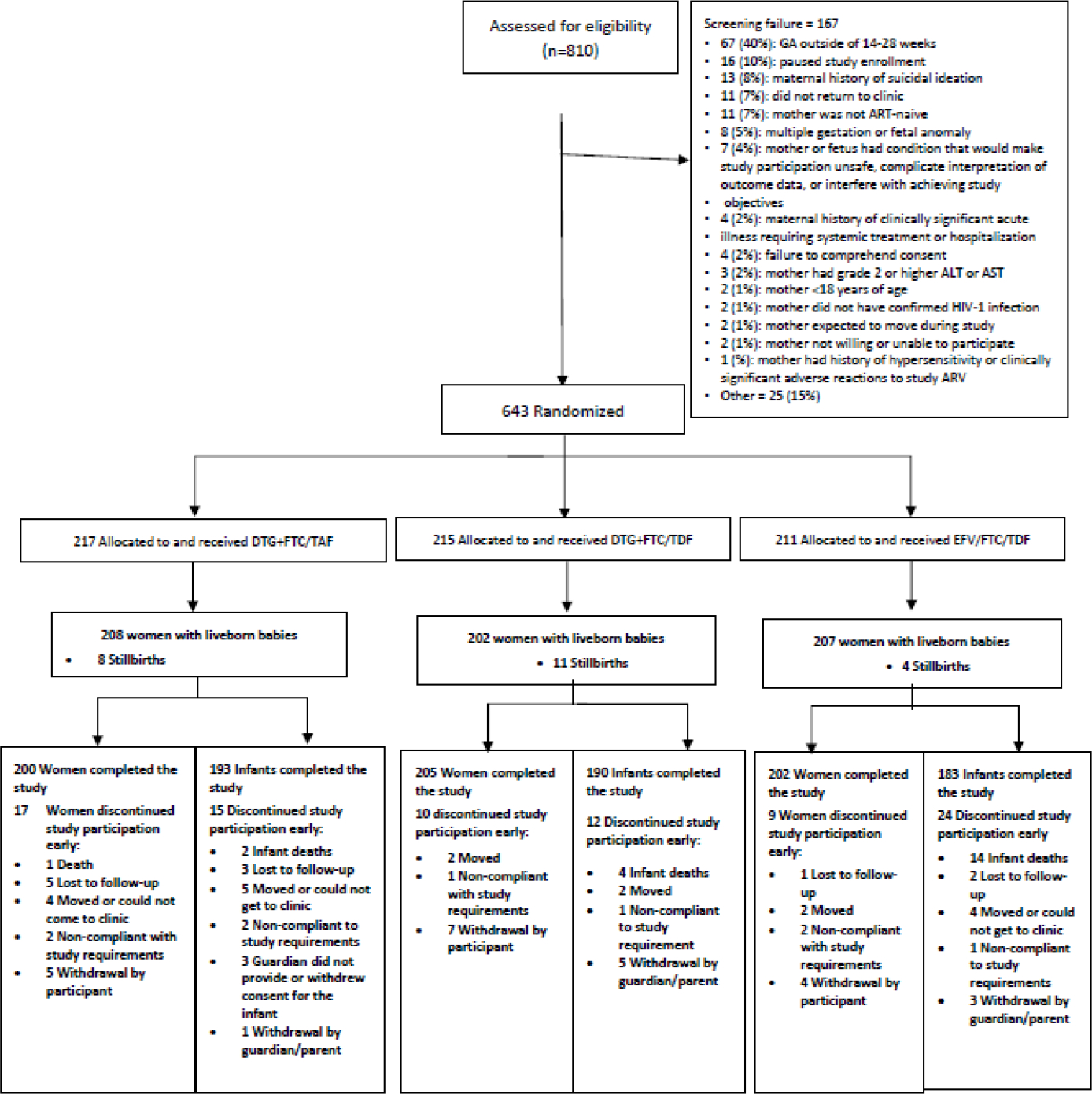

From 19 January 2018 through 8 February 2019, we randomly assigned 643 pregnant women with equal probability to the dolutegravir+emitricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide group (n=217), the dolutegravir+emitricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate group (n=215), or the efavirenz/emitricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate group (n=211; figure 1).

Figure 1:

CONSORT Diagram

Six-hundred and forty (99.5%) had a pregnancy outcome recorded, 617 (96%) with live births and 23 (4%) with stillbirths, defined as intrauterine fetal demise at ≥ 20 weeks gestation (n=19, 3% in the combined dolutegravir-containing groups; n=4, 1% in the efavirenz/emitricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate group). Six hundred and seven (94%) women completed the study through 50 weeks postpartum; 36 (6%) women discontinued study participation early. Of the 617 liveborn infants, 566 (92%) completed the study through postnatal week 50; 51 (8%) discontinued the study early (figure 1).

Baseline maternal characteristics were similar across randomisation groups (table 1). We enrolled the majority (564 [88%]) of participants at research sites in Africa, and most (532 [83%] of 643) had received ART for several days during the pregnancy before enrolment, as permitted per protocol (median 6 days [IQR 4–9], primarily efavirenz-based) (appendix p 6). At enrolment, 640 participants had a plasma HIV-1 RNA load result, with a median 903 copies per mL; 181 (28%) women had HIV-1 RNA <200 copies per mL (table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline maternal and infant characteristics at study enrollment by randomized group

| MATERNAL BASELINE CHARACTERISTICS | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| DTG+FTC/TAF (N = 217) | DTG+FTC/TDF (N = 215) | EFV/FTC/TDF (N = 211) | Total (N = 643) | |

|

| ||||

| Age (median years, range) | 26·8 (18·1–44·5) | 26·0 (18·1–44·0) | 26·6 (18·3–42·7) | 26·6(18·1–44·5) |

|

| ||||

| Country | ||||

| Zimbabwe | 82 (37%) | 84 (39%) | 83 (39%) | 249 (39%) |

| South Africa | 37 (17%) | 37 (17%) | 37 (18%) | 111 (17%) |

| Uganda | 37 (17%) | 37 (17%) | 36 (17%) | 110 (17%) |

| Brazil | 21 (10%) | 19 (9%) | 17 (8%) | 57 (9%) |

| Botswana | 16 (7%) | 18 (8%) | 17 (8%) | 51 (8%) |

| Tanzania | 15 (7%) | 13 (6%) | 15 (7%) | 43 (7%) |

| Thailand | 5 (2%) | 4 (2%) | 6 (3%) | 15 (2%) |

| United States | 2 (1%) | 2 (1%) | 0 (0%) | 4 (1%) |

| India | 2 (1%) | 1 (1%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (1%) |

|

| ||||

| Race | ||||

| Black | 195 (90%) | 196 (91%) | 194 (92%) | 585 (91%) |

| Asian | 7 (3%) | 5 (2%) | 6 (3%) | 18 (3%) |

| White | 5 (2%) | 7 (3%) | 7 (3%) | 19 (3%) |

| Other | 10 (5%) | 6 (3%) | 4 (2%) | 20 (3%) |

| Unknown | 0 (0%) | 1 (1%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (1%) |

|

| ||||

| Gestational age at study enrollment (median weeks, Q1, Q3) | 22·1 (18·4, 25·0) | 21·3 (18·1, 25·1) | 22·1 (18·3, 25·4) | 21·9 (18·3, 25·3) |

|

| ||||

| Gestational age at study entry (categorized) | ||||

| 14–18 weeks | 58 (27%) | 64 (30%) | 59 (28%) | 181 (28%) |

| 19–23 weeks | 93 (43%) | 83 (39%) | 77 (37%) | 253 (39%) |

| 24–28 weeks | 66 (30%) | 68 (32%) | 75 (36%) | 209 (33%) |

|

| ||||

| Hepatitis B surface antigen positive | 3 (1%) | 6 (3%) | 4 (2%) | 13 (2%) |

|

| ||||

| Log10 HIV-1 RNA (median copies/mL, Q1, Q3) | 2·9 (2·2, 3·8) | 2·9 (2·1, 3·6) | 3·1 (2·3, 3·7) | 3·0 (2·2, 3·7) |

|

| ||||

| HIV-1 RNA (median copies/mL, Q1, Q3) | 781 (147, 5,733) | 715 (128, 4,304) | 1,357 (198, 5,125) | 903 (152, 5,183) |

|

| ||||

| HIV-1 RNA (copies/mL, categorized) | ||||

| <50 | 35 (16%) | 37 (17%) | 27 (13%) | 99 (16%) |

| <200 | 62 (29%) | 66 (31%) | 53 (25%) | 181 (28%) |

|

| ||||

| CD4 (median cells/uL, Q1, Q3) | 467 (324, 624) | 481 (332, 642) | 439 (300, 616) | 466 (308, 624) |

|

| ||||

| CD4 (cells/uL, categorized) | ||||

| <50 | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| 50–349 | 64 (30%) | 60 (28%) | 73 (35%) | 197 (31%) |

| 350–499 | 56 (26%) | 54 (25%) | 50 (24%) | 160 (25%) |

| 500–750 | 68 (32%) | 67 (31%) | 59 (28%) | 194 (30%) |

| > 750 | 27 (13%) | 34 (16%) | 26 (13%) | 87 (14%) |

|

| ||||

| Took prior TDF or FTC/TDF pre-exposure prophylaxis * | 1 (1%) | 2 (1%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (1%) |

|

| ||||

| Received ART during a previous pregnancy / breastfeeding * | 1 (1%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (1%) | 2 (0%) |

|

| ||||

| Received ART during current pregnancy prior to enrollment | 176 (81%) | 180 (84%) | 176 (83%) | 532 (83%) |

| Median # days of ART | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 |

| EFV-containing ART regimen | 166 (77%) | 165 (77%) | 166 (79%) | 497 (77%) |

| DTG-containing ART regimen | 7 (3%) | 9 (4%) | 6 (3%) | 22 (3%) |

| Other regimen (not containing DTG or EFV) | 3 (1%) | 6 (3%) | 4 (2%) | 13 (2%) |

|

| ||||

| BMI † , (median BMI [kg/m2], Q1, Q3) | 25.1 (22.5, 29.4) | 24.5 (22.0, 28.1) | 24.2 (21.5, 28.0) | 24.7 (22.0, 28.4) |

|

| ||||

| Weight (median kg, Q1, Q3) | 65.0 (56.7, 77.1) | 63.0 (56.3, 72.0) | 61.4 (55.4, 70.8) | 63.0 (56.2, 73.0) |

|

| ||||

| Creatinine Clearance (median mL/min, Q1, Q3) | 181.2 (150.6, 218.1) | 173.1 (147.1, 214.1) | 168.2 (142.8, 211.2) | 174.2 (146.0, 214.7) |

|

| ||||

| INFANT CHARACTERISTICS, LIVEBORN BABIES | ||||

|

| ||||

| N = 208 | N = 202 | N = 207 | N = 617 | |

|

| ||||

| Female sex | 97 (47%) | 109 (54%) | 101 (49%) | 307 (50%) |

|

| ||||

| Estimated gestational age at birth, (median weeks, Q1, Q3) | 39.7 (38.6, 40.7) | 39.9 (38.7, 40.7) | 39.6 (38.4, 40.4) | 39.6 (38.6, 40.7) |

|

| ||||

| Preterm birth (gestational age <37 weeks at birth) | 12 (6%) | 19 (9%) | 25 (12%) | 56 (9%) |

|

| ||||

| Birthweight (median grams, Q1, Q3) | 3,160 (2,850, 3,500) | 3,065 (2,800, 3,440) | 3,000 (2,705, 3,325) | 3,080 (2,790, 3,400) |

|

| ||||

| Small for gestational age at birth (<10th percentile) | 33 (16%) | 45 (23%) | 41 (21%) | 119 (20%) |

|

| ||||

| Ever breastfed | 161/208 (77%) | 158/202 (78%) | 160/207 (77%) | 479/617 (78%) |

|

| ||||

| Duration of breastfeeding (median weeks, Q1, Q3) | 50.0 (43.7, 51.3) | 49.8 (43.7, 50.6) | 50.0 (41.4, 50.6) | 49.9 (42.9, 50.7) |

|

| ||||

| Received cotrimoxazole prophylaxis | 179 (86%) | 174 (86%) | 169 (82%) | 522 (85%) |

|

| ||||

| Median duration of cotrimoxazole prophylaxis, weeks | 43.1 (20.1, 44.9) | 42.6 (22.3, 44.1) | 42.4 (19.9, 44.3) | 42.8 (20.9, 44.3) |

|

| ||||

| Received antiretroviral prophylaxis | 203 (98%) | 200 (99%) | 196 (95%) | 599 (97%) |

|

| ||||

| Duration of antiretroviral prophylaxis (median weeks, Q1, Q3) | 6.3 (5.9, 6.7) | 6.1 (5.7, 6.9) | 6.3 (5.9, 7.0) | 6.3 (5.9, 6.9) |

All 3 women took <1 week of pre-exposure prophylaxis.

Pre-pregnancy BMI was not available

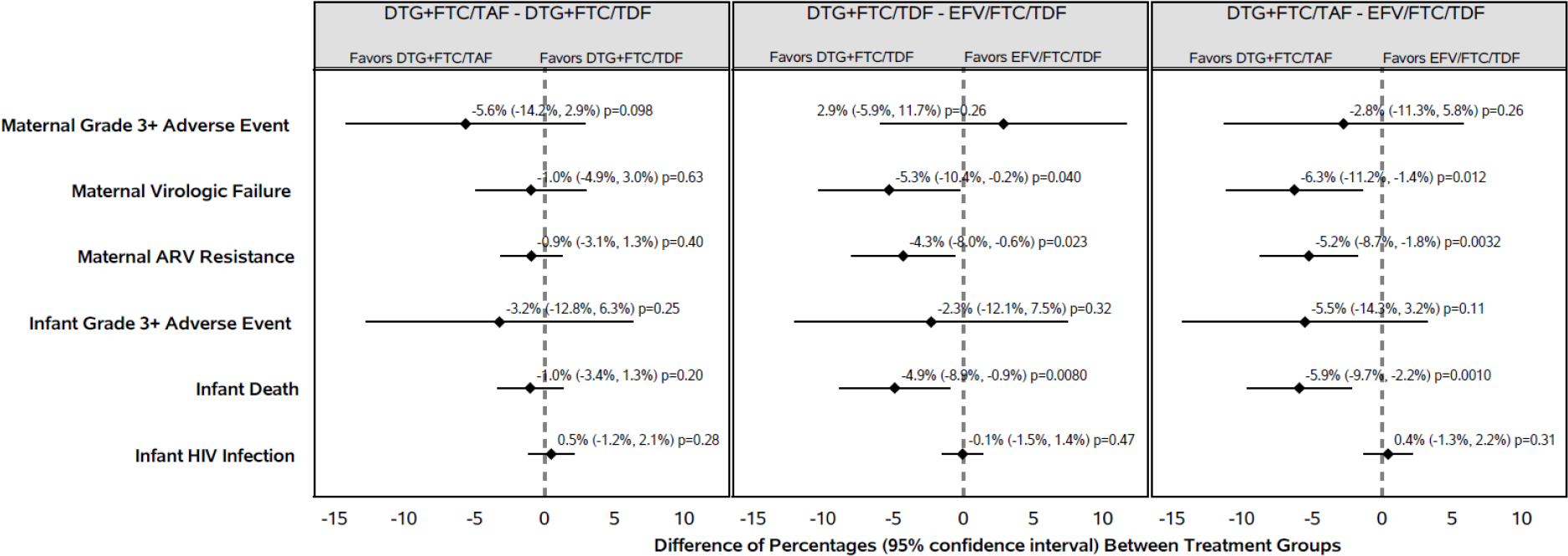

The mean maternal duration on study was 67.1 weeks. The proportions of women experiencing a grade 3 or higher AE by 50 weeks postpartum were 25% in the dolutegravir+emitricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide group, 31% in the dolutegravir+emitricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate group, and 28% in the efavirenz/emitricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate group (table 2). The by-arm differences in the percentage of women experiencing a grade 3 or higher AE were modest and not statistically significant (figure 2). Five women in the dolutegravir+emitricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide group, 2 in the dolutegravir+emitricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate group, and 4 in the efavirenz/emitricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate group experienced an AE that led to at least one switch, addition, or removal (including pauses) of any drug in the study treatment regimen (appendix pp 7–8).

Table 2.

Maternal and infant safety and other Health outcomes from enrollment through 50 weeks postpartum

| DTG+FTC/TAF (N = 217) | DTG+FTC/TDF (N = 215) | EFV/FTC/TDF (N = 211) | TOTAL (N=643) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| MATERNAL ADVERSE EVENTS THROUGH 50 WEEKS POSTPARTUM | ||||

|

| ||||

| Any grade ≥ 3 clinical or laboratory adverse event † | 53 (25%) | 66 (31%) | 58 (28%) | 177 (28%) |

|

| ||||

| Any grade ≥ 3 clinical adverse event | 43 (20%) | 41 (19%) | 45 (21%) | 129 (20%) |

| Selected frequent/relevant clinical events: | ||||

| Infection | 5 (2%) | 5 (2%) | 9 (4%) | 19 (3%) |

| Gestational diabetes | 0 (0%) | 1 (1%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (0%) |

| Type 2 diabetes mellitus | 1 (1%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (0%) |

|

| ||||

| Death * | 1 (1%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (0%) |

|

| ||||

| Any grade ≥ 3 laboratory-based adverse event | 16 (7%) | 33 (15%) | 23 (11%) | 72 (11%) |

| Low hemoglobin (most grade 3) | 8 (4%) | 20 (9%) | 15 (7%) | 43 (7%) |

| Low creatinine clearance† (all grade 3) | 4 (2%) | 7 (3%) | 3 (1%) | 14 (2%) |

| Elevated aspartate aminotransferase (AST)‡ | 1 (1%) | 4 (2%) | 2 (1%) | 7 (1%) |

|

| ||||

| OTHER MATERNAL HEALTH OUTCOMES AT 50 WEEKS POSTPARTUM | ||||

|

| ||||

| Median CD4 cell count (cells/mm3) | 743 | 747 | 682 | 724 |

|

| ||||

| Estimated creatinine clearance (mean (sd), mL/min) ¥ | 124.4 (42.4) | 117.8 (34.7) | 131.3 (36.4) | 124.5 (38.3) |

|

| ||||

| Antepartum average (95% CI) weight change per week through delivery (kg) | 0.378 (0.343, 0.412) | 0.319 (0.291, 0.348) | 0.291 (0.260, 0.322) | 0.331 (0.312, 0.349) |

|

| ||||

| Postpartum average (95% CI) weight change per week through week 50 postpartum (kg) | 0.014 (−0.004, 0.032) | −0.008 (−0.027, 0.012) | −0.032 (−0.048, −0.017) | −0.009 (−0.019, 0.002 |

|

| ||||

| Maternal obesity at week 50 postpartum (BMI ≥ 30kg/m2), n (%) | 43/190 (23%) | 35/190 (18%) | 29/193 (15%) | 107/543 (19%) |

|

| ||||

| INFANT ADVERSE EVENTS THROUGH 50 WEEKS AFTER BIRTH | ||||

|

| ||||

| Any grade ≥ 3 clinical or laboratory adverse event † | 51 (25%) | 53 (29%) | 63 (31%) | 167 (28%) |

|

| ||||

| Any grade ≥ 3 clinical adverse event | 29 (14%) | 34 (17%) | 44 (21%) | 107 (17%) |

| Infections excluding HIVꬸ | 10/208 (5%) | 17/202 (8%) | 19/207 (9%) | 46/617 (8%) |

| Respiratory disorders | 11/208 (5%) | 7/202 (4%) | 13/207 (6%) | 31/617 (5%) |

| Nervous system disorders | 4/208 (2%) | 1/202 (1%) | 7/202 (3%) | 12/617 (2%) |

|

| ||||

| Any grade ≥ 3 clinical laboratory-based adverse event | 27 (13%) | 25 (12%) | 29 (14%) | 81/617 (13%) |

| Decreased neutrophil count | 10/208 (5%) | 7/202 (4%) | 14/207 (7%) | 31/617 (5%) |

| Low hemoglobin or reported anemia | 9/208 (4%) | 9/202 (5%) | 7/207 (3%) | 25/617 (4%) |

| Increased blood creatinine | 4/208 (2%) | 8/202 (4%) | 4/207 (2%) | 16/617 (3%) |

| Decreased blood glucose | 3/208 (1%) | 3/202 (2%) | 4/207 (2%) | 10/617 (2%) |

| Othersꬹ | 2/208 (1%) | 3/202 (2%) | 3/207 (1%) | 8/617 (1%) |

|

| ||||

| Infant death § | 2 (1%) | 4 (2%) | 14 (7%) | 20 (3%) |

| Born preterm (<37 weeks) | 1 | 1 | 6 | 8 |

| Small for gestational age | 2 | 2 | 3 | 7 |

|

| ||||

| Major congenital anomaly | 2/208 (1%) | 0/202 (0%) | 2/207 (1%) | 4/617 (1%) |

|

| ||||

| Estimated creatinine clearance at week 26 post-birth (mean (sd), mL/min) ¥ | 134.8 (109.6) | 123.6 (40.3) | 135.0 (51.1) | 131.1 (73.8) |

|

| ||||

| Infant HIV infection † | 2 (0.98%) | 1 (0.50%) | 1 (0.55%) | 4 (0.6%) |

Table 2 presents the numbers of women and infants with grade ≥ 3 adverse events; some women and infants may have each had more than 1 adverse event, hence not all columns will total. Participants who experienced multiple grade ≥ 3 events were reported at the highest-grade event in each row. Only the most frequent or relevant specific clinical events are listed.

Estimated probability of experiencing an event through 50 weeks postpartum or after birth from Kaplan-Meier model

One mother died of sepsis approximately 2 weeks following Cesarean section.

Defined as creatinine concentration of 1·8 times the upper limit of normal or estimated creatinine clearance <60 mL/min by Cockcroft-Gault.

Of the elevated AST, 2 were grade 4; elevated AST occurred during pregnancy and the other during postpartum period.

Calculated by the Cockcroft-Gault equation

Only one infant death from a mother on DTG+FTC/TDF had confirmed HIV infection, other infants had unknown HIV status (n=12; 9 in EFV/FTC/TDF, 2 in DTG+FTC/TAF and 1 in DTG+FTC/TDF), indeterminate HIV status (n=3; 2 in EFV/FTC/TDF and 1 in DTG+FTC/TDF) and likely HIV-uninfected (n=3; 2 in EFV/FTC/TDF and 1 in DTG+FTC/TDF)) at the time of death

Include increased bilirubin, increased potassium, increased alanine aminotransferase and decreased white cell count

Include neonatal sepsis, pneumonia, bronchiolitis

Figure 2:

Pairwise Differences in Safety and Virologic Outcomes

The most common grade 3 or higher clinical AE was infection and the most common grade 3 or higher laboratory AE was decreased hemoglobin (table 2). One woman in the dolutegravir+emitricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide group died of sepsis 2 weeks after caesarean delivery. Three women (1 in dolutegravir+emitricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate and 2 in efavirenz/emitricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate) had gestational diabetes reported (any grade), and 1 woman had grade 3 type 2 diabetes mellitus (in the dolutegravir+emitricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide group). One woman had grade 3 suicidal ideation (in the efavirenz/emitricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate group).

Creatinine clearance data were available for 574 (89%) women at 50 weeks postpartum; low creatinine clearance (grade 3 or higher was observed) in 4 (2%) women in the dolutegravir+emitricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide group, 7 (3%) women in the dolutegravir+emitricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate group and 3 (1%) women in the efavirenz/emitricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate group (table 2).

The average weekly antepartum weight gain was significantly greater among women in the dolutegravir+emitricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide group than those in the dolutegravir+emitricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate group (difference [95% CI]: 0·058 kg/week [0·013, 0·103], p=0·011) and the efavirenz/emitricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate group (difference [95% CI]: 0·086 kg/week [0·040, 0·133], p=0·0002) (table 2). Postpartum, women in the dolutegravir+emitricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide group gained an average of 0.014 kg/week, while women in the efavirenz/emitricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate group lost an average of 0.032 kg/week (difference [95% CI]: 0.046 kg/week [0.022, 0.070], p=0.0001). Postpartum maternal weight change did not differ significantly between the dolutegravir+emitricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide and dolutegravir+emitricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate groups (difference [95% CI]: 0.022 kg/week [−0.005, 0.048], p=0.11). At postpartum week 50, a higher proportion of women in the dolutegravir+emitricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide group (23%) were obese (BMI ≥30 kg/m2) than in the efavirenz/emitricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate group (15%) (difference [95% CI]: 7.6% [−0.2%, 15.4%]), or the dolutegravir+emitricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate group (18%), (difference [95% CI]: 4.2% [−3.9%, 12.3%]). The by-arm difference between women in the dolutegravir+emitricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate group and women in the efavirenz/emitricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate group was 3.4% (95% CI: −4.1%, 10.9%) (appendix table p 9).

Characteristics at birth of the 617 liveborn infants were similar by randomization group except birthweight, preterm birth (gestational age <37 weeks at birth in liveborn infants), and small for gestational age (<10th percentile) (table 1). Four infants were diagnosed with major congenital anomalies: atrial septal defect in 1 infant and talipes equinovarus in 1 infant in the dolutegravir+emitricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide group, duodenal atresia plus ileal stenosis in 1 infant and subgaleal cyst in 1 infant in the efavirenz/emitricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate group (table 2). No infants were diagnosed with neural tube defect.

Most (522, 85%) infants received co-trimoxazole prophylaxis and 479 (78%) breastfed (99% of infants were breastfeeding at time of last infant HIV test) (table 1, appendix p 10). Nearly all neonates (599, 97%), took antiretroviral prophylaxis for a median duration of 6.3 weeks (table 1), with nevirapine prescribed to 526 (85%) of the infants.

The mean infant duration on study was 47.6 weeks. The probability of experiencing at least one grade 3 or higher AE by postnatal week 50 was 28% overall, with small and non-statistically significant differences between arms (table 2, figure 2). The most common types of grade 3 or higher clinical AE in infants were infectious and respiratory disorders. Twenty (3%) infants died by 50 weeks after birth, 15 of whom died within 28 days of birth (8 were born preterm and 7 were born small for gestational age) (table 2). Infant deaths were significantly higher in the efavirenz/emitricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate group (14 [7%]) than either the dolutegravir+emitricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide group (2 [1%]), (difference [95% CI]: −5.9% [−9.7%, −2.2%], p=0.0010) or the dolutegravir+emitricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate group (4 [2%]), (difference [95%CI: −4.9% [95% CI: −8.9%, −0.9%], p = 0.008) (figure 2). The main causes of infant death were hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy, sepsis, and pneumonia.

In post-hoc analysis, a combined endpoint of either infant death or stillbirth occurred in 5% of mother-infant pairs in the dolutegravir+emitricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide group, 7% in the dolutegravir+emitricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate group, and 9% in the efavirenz/emitricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate group. This combined endpoint of stillbirth or neonatal death did not appear to differ between the study treatment groups (p-values ≥ 0.37; appendix p 11).

The most common grade 3 or higher laboratory test AE was decreased neutrophil count (table 2). At birth, 558 (90%) infants had creatinine clearance data. There were no significant differences in infant creatinine clearance between study treatment groups at birth (p-values ≥ 0.18; appendix p 12]). Among breastfeeding infants at postnatal week 26, the estimated creatinine clearance was lower in the dolutegravir+emitricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate group than the efavirenz/emitricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate group (difference [95% CI]: −11.4 [−22.6, −0.1] ml/min, p-value = 0.048) but did not differ significantly between the two dolutegravir-containing groups, nor between the dolutegravir+emitricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide and efavirenz/emitricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate groups (appendix p 12).

Five hundred fifty-seven (90%) liveborn infants had at least one HIV-1 nucleic acid result available at the week 50 visit. Four infant HIV-1 infections occurred in the study with no differences in the probability of HIV infection among the three treatment groups (p-value ≥ 0.28, table 2, appendix p 13). Two infants had a first positive HIV-1 test within 14 days after birth, one in the dolutegravir+emitricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide group with maternal HIV-1 RNA >9000 copies per mL at all visits through delivery, and one in the dolutegravir+emitricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate group, with the highest maternal HIV-1 RNA through delivery of 42 copies per mL (as previously reported11). One infant in the dolutegravir+emitricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide group had a first positive HIV-1 test at 6 weeks of age, with maternal HIV-1 RNA < 40 copies per mL from antepartum 8 weeks on study. One infant in the efavirenz/emitricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate group had a first positive HIV-1 test at 50 weeks of age, with maternal HIV-1 RNA ≥ 64 copies per mL through 26 weeks postpartum (appendix pp 14–15). All 4 infants with HIV were breastfed and received at least 6 weeks of antiretroviral prophylaxis prior to HIV diagnosis.

Overall, 573 (89%) of 643 women had plasma HIV-1 RNA available within the pre-specified week 50 visit window (an additional 30 [5%] women had HIV-1 RNA available in the extended visit window during the COVID-19 pandemic).

The proportions of women with HIV-1 RNA <200 copies per mL at week 50 were similar in the combined dolutegravir-containing groups (366, 96%) and the efavirenz/emitricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate group (186, 96%; difference [95% CI]: −0.1% [−3.3%, 3.2%], p-value = 0.97) (appendix pp 16–18). In multiple imputation analysis (which included HIV-1 RNA results from the 30 women with data in the extended visit window and all participants with missing week 50 HIV-1 RNA), the estimated proportions of women with virologic suppression at week 50 were 96% in the dolutegravir-containing group and 96% in the efavirenz/emitricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate group.

Overall, 42 (7%) women experienced virologic failure: 9 (4%) in the dolutegravir+emitricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide group, 11 (5%) in the dolutegravir+emitricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate group, and 22 (10%) in the efavirenz/emitricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate group (table 3). Among the 26 participants who discontinued study treatment in the efavirenz/emitricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate group, 14 discontinued due to virologic failure (n=7), viremia (n=2), or drug resistance (n=5) whereas no participant discontinued treatment due to these reasons in the dolutegravir-containing groups. Twenty-one women in the dolutegravir-containing groups discontinued study treatment postpartum per protocol due to their desire for pregnancy postpartum and/or to not use protocol-specified contraception).

Table 3.

Study treatment regimen switches from enrollment to 50 weeks postpartum

| DTG+FTC/TAF n/N (%) | DTG+FTC/TDF n/N (%) | EFV/FTC/TDF n/N (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Switched (or stopped but not pauses) study ART regimen early for any reason * | 33/217 (15%) 0/33 (0%) |

25/215 (12%) 0/25 (0%) |

26/211 14§/26 (12%) |

| Virologic failure/drug resistance | 4/33 (12%) | 2/25 (8%) | 3/26 (12%) |

| Adverse event | 11/33 (33%) | 10/25 (40%) | 0/26 (0%) |

| Desire for pregnancy postpartum | 18/33 (55%) | 13/25 (52%) | 9/26 (37%) |

| Other‡ | |||

|

| |||

| Virologic failure †,¥ | 9/217 (4%) | 11/215 (5%) | 22/211 (10%) |

|

| |||

| Any HIV drug resistance | 2/217 (1%) | 4/215 (2%) | 13/211 (6%) |

Virologic failure defined as 2 successive HIV-1 RNA ≥ 200cp/mL at or after 24 weeks on study.

Of the 14 who stopped or switched treatment: 7 were due to virologic failure, 2 to viremia and 5 to drug resistance

Other; most frequent reasons were participant withdrew of consent, relocation from study site, noncompliance

Among the 607 women on study at 50 weeks postpartum, 598 (99%) were taking ARVs: 197/200 (99%) in the DTG+FTC/TAF arm, 201/205 (98%) in DTG+FTC/TDF arm, and 200/202 (99%) in EFV/FTC/TDF arm.

Of the 42 women experiencing virologic failure, 35 (83%) had a genotype result from a sample taken at the time of failure. While 19 (54%) of these women had at least one HIV drug resistance mutation at virologic failure, most of these mutations were also detected in their enrollment samples. At study entry, drug resistance mutations were detected in 15 (36%) of 42 women with virologic failure, including 10 women in the efavirenz/emitricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate group, and 5 women in the dolutegravir-containing groups. In 13 of these women, non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTI) resistance mutations were present, whereas 2 women had protease inhibitor resistance mutations at study entry. At study entry, no woman had mutations associated with dolutegravir resistance. Of the 19 women who had HIV drug resistance at the time of virologic failure, new resistance mutations (compared with study entry) were detected in 9 women. These included 2 women in the dolutegravir-containing groups, one with a NNRTI mutation (K103N) and one with major (N155H) and accessory (L74I, S147G, and S230R) dolutegravir-associated mutations; and 7 women in the efavirenz/emitricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate group (primarily efavirenz-associated mutations K103N, V106M, V108I and/or P225H).

DISCUSSION

We performed a randomized comparison of the efficacy and safety in pregnancy and postpartum of three commonly used ART regimens. This study is the earliest and largest trial to assess the effect of dolutegravir (and tenofovir alafenamide) started in pregnancy on virologic and safety outcomes. Our results provide further assurance regarding the use of dolutegravir-based ART by pregnant and postpartum women, particularly when combined with emitricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide, due to both better safety and efficacy outcomes in pregnancy and postpartum.

Our primary week 50 endpoint was safety. We did not observe significant differences in grade 3 or higher AEs in women or infants between treatment groups. The proportion of women experiencing grade 3 or higher AEs in our study was similar to rates in women receiving efavirenz-based ART during pregnancy in a prior trial in Uganda.17 However, we observed a significantly higher rate of 50-week mortality in infants whose mothers were in the efavirenz/emitricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate group than in either of the dolutegravir groups. Most infant mortality occurred within 4 weeks of birth, and the main diagnoses associated with death included hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy, sepsis, and pneumonia, which reflect common causes of neonatal death.18 The reason for the higher 50-week infant mortality rate in the efavirenz/emitricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate group is not known. Potential hypotheses include higher rates of preterm birth and small for gestational age in infants in the efavirenz/emitricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate group, the potential mechanisms of which need further research. We previously reported significantly lower rates of a composite of adverse pregnancy outcomes (stillbirth, preterm birth, and small for gestational age) in the dolutegravir+emitricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide group compared with either of the other two groups.19

Collectively, pregnancy outcome and week 50 postpartum data from this trial suggest that dolutegravir-containing ART (particularly dolutegravir+emitricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide) is safer to start in pregnancy than efavirenz/emitricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate and has greater virologic efficacy. The reasons for the worse pregnancy and infant mortality outcomes with efavirenz/emitricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate are unknown. One potential explanation is the lower pregnancy weight gain (and higher frequency of inadequate weight gain) in women in the efavirenz/emitricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate group. Women in the dolutegravir+emitricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide group gained more weight antepartum than the women in the efavirenz/emitricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate group (although weight gain in all groups was still below the recommended weight gain in pregnancy)20, and greater antepartum weight gain was associated with better birth and neonatal outcomes. The reasons for better pregnancy outcomes with tenofovir alafenamide compared with tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (each in combination with dolutegravir+emitricitabine) are also not known; tenofovir alafenamide yields substantially lower plasma tenofovir levels than tenofovir disoproxil fumarate, and ART containing tenofovir disoproxil fumarate was associated with higher rates of severe adverse pregnancy/neonatal outcomes in the randomized PROMISE trial compared with zidovudine (in combination with lopinavir/ritonavir and lamivudine).21 Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate is also associated with lower weight gain than tenofovir alafenamide (including during pregnancy in our trial). Additional analyses of the potential contribution of maternal weight gain to birth and child outcomes are underway, and the long-term effects of greater weight gain with dolutegravir (including on outcomes of subsequent pregnancies) should be studied.

Major congenital anomalies were uncommon, with no concerning pattern, and no infant was born with neural tube defects (although ART was started after the first trimester). Breastfeeding infants born to women in the efavirenz/emitricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate group had significantly higher creatinine clearance than in the dolutegravir+emitricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate group; this may be due to the interference of dolutegravir (ingested in breastmilk) with renal tubular creatinine excretion, which can lead to a non-pathologic increase in estimated creatinine clearance.

Four infants were diagnosed with HIV, 2 of them in the setting of maternal HIV-1 RNA close to or <40 copies per mL on all tests preceding the first positive infant HIV-1 test (1 in the dolutegravir+emitricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide group and 1 in the dolutegravir+emitricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate group). Plausible explanations for HIV infection in these 2 infants include in utero transmission prior to ART initiation at 25–26 weeks’ gestation, or post-randomization transmission during periods of possible non-adherence while on study treatment.

We found similarly high maternal virologic suppression at 50 weeks postpartum in women starting dolutegravir-containing vs. efavirenz-containing ART in pregnancy, in the primary intent-to-treat analyses which does not account for regimen switches due to virologic failure. However, more women in the efavirenz/emitricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate group switched or stopped their ART regimen due to virologic failure or drug resistance in the efavirenz/emitricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate group compared with each of the dolutegravir-containing groups.

The VESTED study has several strengths. It is one of very few randomised trials of ART in pregnancy and the only study of its size to study contemporary antiretrovirals (including tenofovir alafenamide).19,22,23 The study enrolled women in multiple countries and settings and provides robust data for use of ART in settings disproportionately affected by HIV and beyond. All women underwent obstetric ultrasound for gestational age estimation (although accuracy was less optimal than with first trimester ultrasound). Retention and data completeness were high. The study also had several limitations. We enrolled women from 14 weeks gestation, thus we could not fully evaluate congenital anomalies or spontaneous abortion arising from the effects of drug exposure at conception or during organogenesis. We also are unable to evaluate pregnancy, postpartum and infant outcomes in women who become pregnant after taking these regimens for prolonged periods. The study was not powered to detect differences in rare AE outcomes including dolutegravir-associated hyperglycemia and perinatal HIV transmission between groups.

In conclusion, the VESTED study showed that among women starting ART in pregnancy and their infants, dolutegravir-containing ART resulted in lower rates of virologic failure, HIV drug resistance, and infant mortality through 50 weeks postpartum compared with efavirenz/emitricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate. However, rates of grade ≥ 3 AEs were similar. When considered in conjunction with superior virologic efficacy at delivery with dolutegravir-containing ART, and lower rates of adverse pregnancy outcomes with dolutegravir+emitricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide, our data suggest that dolutegravir-based ART is safer and more effective for women than efavirenz/emitricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate started in pregnancy, and that tenofovir alafenamide is preferable to tenofovir disoproxil fumarate with regard to adverse pregnancy outcomes (when combined with dolutegravir and emitricitabine). These findings affirm the WHO recommendation to use dolutegravir in all populations,24 including in pregnant and postpartum women.

Supplementary Material

RESEARCH IN CONTEXT.

Evidence before this study

Approximately 1.3 million pregnant women with HIV deliver infants annually. Until recently, the World Health Organization (WHO) recommended a 3-drug combination of efavirenz, lamivudine or emtricitabine, and tenofovir disoproxil fumarate as first-line antiretroviral therapy (ART) for adults, including pregnant women. In 2018, these guidelines were modified, and efavirenz was replaced with dolutegravir, a potent and well-tolerated integrase inhibitor with a high genetic barrier to drug resistance. In addition, the newer agent tenofovir alafenamide fumarate has begun to replace tenofovir disoproxil fumarate as first-line ART in several countries, owing to its lower bone and renal toxicity and lower manufacturing cost.

On March 11, 2021, we searched PubMed for primary research articles published in any language between database inception and the date of the literature search using the Medical Subject Heading search terms “HIV” and “pregnancy”, in conjunction with either “dolutegravir”, “efavirenz”, “tenofovir alafenamide fumarate”, or “tenofovir disoproxil fumarate”; we also searched abstracts of major HIV conferences over the past 3 years using the same search terms. We found a total of 73 publications, including 23 clinical trials, and 161 abstracts. We found limited safety and efficacy data in pregnancy through postpartum for most antiretrovirals, including those recommended by the WHO for first-line treatment of adults. Some small studies have reported high virologic efficacy of dolutegravir-containing ART during pregnancy, but these were not designed to evaluate adverse pregnancy outcomes or compare maternal and infant adverse events through the postpartum period. Furthermore, limited data exist regarding the safety and efficacy of tenofovir alafenamide in pregnancy.

Added value of this study

Our study is one of very few randomized trials designed to compare the safety and virologic efficacy of different contemporary ART regimens taken in pregnancy and postpartum. In nine countries, we randomized pregnant women with HIV at 14–28 weeks of gestation to start one of three ART regimens: dolutegravir+emitricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide, dolutegravir+emitricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate, or efavirenz/emitricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate. Here, we report longer term safety and virologic efficacy outcomes of the study treatment regimens used during pregnancy and breastfeeding through 50 weeks postpartum for women and their infants. We previously reported that adverse pregnancy outcomes occurred less frequently in the dolutegravir+emitricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide group than in the other groups. At 50 weeks postpartum, we observed similarly high efficacy in the combined dolutegravir-containing groups (96%) and the efavirenz-containing group (96%). However, women in the efavirenz-containing group were more likely to stop or switch their regimen due to virologic failure or resistance to efavirenz. The proportion of maternal grade 3 or higher adverse events and of infant grade 3 or higher adverse events through 50 weeks postpartum were similar in all treatment groups. However, a higher proportion of infants died in the efavirenz-containing group compared to either of the dolutegravir-containing groups. Vertical transmission of HIV through the first 50 weeks after birth was low with no difference by treatment group.

Implications of all the available evidence

Our findings support the recommendation for use of dolutegravir-containing regimens started in pregnancy through postpartum because of their superior virologic efficacy in pregnancy and postpartum, lower rate of regimen switch due to virologic failure or drug resistance, and higher infant survival. Our findings also support the use of tenofovir alafenamide/emitricitabine started in pregnancy (in combination with dolutegravir) due to its favorable safety profile.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded and sponsored by the IMPAACT Network. Overall support for the IMPAACT Network was provided by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, with co-funding from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, and the National Institute of Mental Health, all of which are components of the National Institutes of Health (UM1AI068632 [IMPAACT LOC], UM1AI068616 [IMPAACT SDMC], and UM1AI106716 [IMPAACT LC], and HHSN275201800001I). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. We thank and acknowledge the trial participants; the site investigators, site staff, and collaborating institutions, and the local and IMPAACT community advisory board members who supported this trial; the IMPAACT Network leadership; the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases African Data and Safety Monitoring Board members; the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Therapeutics and Prevention Data and Safety Monitoring Board members; and the Safety Review Group members.

Footnotes

Declaration of interest

JvW is an employee of ViiV Healthcare and JFR is an employee of Gilead Sciences. All other authors declare no competing interests.

IMPAACT 2010/VESTED Study Team and Investigators

Participating Sites: BOTSWANA. Botswana Harvard AIDS Institute Partnership, Gaborone and Molepolole: Ponego L. Ponatshego, MD, Lesedi Tirelo, Dip Nursing, Boitshepo J. Seme, Dip Nursing, Georginah O. Modise, Dip Nursing, Mpho S. Raesi, BSN, Marian E. Budu, MBBS, Moakanyi Ramogodiri, Dip Nursing; BRAZIL. Instituto de Puericultura e Pediatria Martagão Gesteira - IPPMG, UFRJ, Rio de Janeiro: Ricardo Hugo Oliveira, MD, Mac, Cristina Barroso Hofe,PhD, Thalita Fernandes de Abreu, PhD, Lorena Macedo Pestanha, MD; Hospital Federal dos Servidores do Estado, Rio de Janeiro: Esaú João, PhD, Leon Claude Sidi, MD, Trevon Fuller, PhD, Maria Leticia Santos Cruz, PhD; Federal University of Minas Gerais: Jorge Pinto, MD, Flãvia Ferreira, MD, Mãrio Correa Jr, MD, Juliana Romeiro, PhD; Hospital Geral de Nova Iguacu & Aids and Molecular Immunology Laboratory/ IOC: Jose Henrique Pilotto, PhD, Luis Eduardo Barros Costa Fernandes, MD, Luiz Felipe Moreira, MD, Ivete Martins Gomes, MD; INDIA. Byramjee Jeejeebhoy Medical College (BJMC) CRS, Pune: Shilpa Naik, MD, Neetal Nevrekar, MD, Vidya Mave, MD, Aarti Kinikar, MD; SOUTH AFRICA. Shandukani Research Centre, Wits Reproductive Health and HIV Institute, Johannesburg: Elizea Horne, MBCHB, Hamisha Soma-Kasiram, MBBCh; Perinatal HIV Research Unit, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg: Avy Violari, FCPaed, Sisinyana Ruth Mathiba, MBChB, Mandisa Nyati, MBChB; FAMCRU, Cape Town: Gerhard Theron, MD, Jeanne de Jager, MSc, Magdel Rossouw, MBChB, Lindie Rossouw, MBChB; CAPRISA Umlazi CRS, University of Kwazulu Natal, Durban: Sherika Hanley, MMed, Alicia Catherine Desmond, MPharm, Rosemary Gazu, Dip Nursing, Vani Govender, BSC Hon; THAILAND. Siriraj Hospital, Mahidol University, Bangkok: Amphan Chalermchockcharoenkit, MD, Manopchai Thamkhantho, MD, Peerawong Werarak, MD, Supattra Rungmaitree, MD; Chiangrai Prachanukroh Hospital, Chiangrai: Jullapong Achalapong, MD, Lukkana Sitiritkawin, BSN; AMS-CMU & IRD Research Collaboration, Chiangrai: Tim R. Cressey, PhD, Pra-ornsuda Sukrakanchana, BSN; Research Institute for Health Sciences, Chiang Mai University: Linda Aurpibul, MD, Fuanglada Tongprasert, MD, Chintana Khamrong, MSc, Sopida Kiattivej, BNS, RN; UGANDA. MUJHU CARE LTD, Kampala: Deo Wabwire, MMED, Enid Kabugo, MSc, Joel Maena, MPH, Frances Nakayiwa, BSCN; Baylor College of Medicine Children’s Foundation-Uganda, Kampala: Victoria Ndyanabangi, MPH, Beatrice Nagaddya, Dip Nus Mid, Rogers Sekabira, MPS, Justus Ashaba, BCS; UNITED STATES. University of Miami, Miami, FL: Charles D. Mitchell, MD, Adriana Drada, CCRP, Grace A. Alvarez, MPH, Gwendolyn B. Scott, MD; UF CARES, Jacksonville, FL: Mobeen Rathore, MD, Saniyyah Mahmoudi, MSN, ARNP, Adnan Shabbir, BS, Nizar Maraqa, MD; ZIMBABWE. University of Zimbabwe Clinical Trials Research Centre, Harare: St. Mary’s: Patricia Fadzayi Mandima, MPH, Mercy Mutambanengwe, BPharm Hons, Suzen Maonera, MSc, Gift Chareka, MSc; Seke North: Teacler Nematadzira, MSc, Vongai Chanaiwa, MSc, Taguma Allen Matubu, PhD, Kevin Tamirepi, BPharm Hons; Harare Family Care: Sukunena Maturure, DCN, Tsungai Mhembere, MPH, Tichaona Vhembo, MPH, Tinashe Chidemo, MBA; Additional Study Team Members: Boston Medical Center, Boston, MA, USA: Mark Mirochnick; Community Advisory Board Member, Kampala, Uganda: Nagawa Jaliaah; FHI 360, Durham, NC, USA: Cheryl D. Blanchette; Laboratory Center at UCLA: William Murtaugh, MPH, and Frances Whalen, MPH; University of California, San Diego, CA, USA: Brookie M. Best; National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, Rockville, MD, USA: Renee Browning.

Data sharing

The data in this study cannot be made publicly available due to ethical restrictions in the study’s informed consent documents and in the IMPAACT Network’s approved human subjects protection plan; public data availability could compromise participant confidentiality. However, data, including participant data with partially identifying information, are available to interested researchers on request to the IMPAACT Statistical and Data Management Center’s Data Access Committee (sdac.data@fstrf.org), with the agreement of the IMPAACT Network.

References

- 1.Connor EM, Sperling RS, Gelber R, Kiselev P, Scott G, O’Sullivan MJ, et al. Reduction of maternal-infant transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 with zidovudine treatment. Pediatric AIDS Clinical Trials Group Protocol 076 Study Group. N Engl J Med [Internet]. 1994. Nov 3 [cited 2021 Apr 6];331(18):1173–80. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7935654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Panel on Treatment of Pregnant Women with HIV Infection and Prevention of Perinatal Transmission. Recommendations for Use of Antiretroviral Drugs in Transmission in the United States. Available at http://aidsinfo.nih.gov/contentfiles/lvguidelines/PerinatalGL.pdf. (Accessed Dec 13, 2022). [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization “Updated Recommendations on First-Line and Second-Line Antiretroviral Regimens and Post-Exposure Prophylaxis and Recommendations on Early Infant Diagnosis of HIV: Interim Guidelines: Supplement to the 2016 Consolidated Guidelines on the Use of Antiretrovi. World Health Organization, “Updated Recommendations on First-Line and Second-Line Antiretroviral Regimens and Post-Exposure Prophylaxis and Recommendations on Early Infant Diagnosis of HIV: Interim Guidelines: Supplement to the 2016 Consolidated Guideline. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sax PE, Wohl D, Yin MT, et al. Tenofovir alafenamide versus tenofovir disoproxil fumarate, coformulated with elvitegravir, cobicistat, and emtricitabine, for initial treatment of HIV-1 infection: two randomised, double-blind, phase 3, non-inferiority trials. Lancet 2015; 385: 2606–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ripin D, Prabhu VR. A cost-savings analysis of a candidate universal antiretroviral regimen. Curr Opin HIV AIDS 2017; 12: 403–07. / [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gupta SK, Post FA, Arribas JR, et al. Renal safety of tenofovir alafenamide vs. tenofovir disoproxil fumarate: a pooled analysis of 26 clinical trials. AIDS 2019; 33: 1455–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Venter WDF, Sokhela S, Simmons B, Moorhouse M, Fairlie L, Mashabane N, Serenata C, Akpomiemie G, Masenya M, Qavi A, Chandiwana N, McCann K, Norris S, Chersich M, Maartens G, Lalla-Edward S, Vos A, Clayden P, Abrams E, Arulappan N, Hill A. Dolutegravir with emtricitabine and tenofovir alafenamide or tenofovir disoproxil fumarate versus efavirenz, emtricitabine, and tenofovir disoproxil fumarate for initial treatment of HIV-1 infection (ADVANCE): week 96 results from a randomised, phase 3, non-inferiority trial. Lancet HIV. 2020. Oct;7(10):e666–e676. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3018(20)30241-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zash R, Makhema J, Shapiro RL. Neural-Tube Defects with Dolutegravir Treatment from the Time of Conception. N Engl J Med. 2018. Sep 6;379(10):979–981. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1807653. Epub 2018 Jul 24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zash R, Holmes L, Diseko M, Jacobson DL, Brummel S, Mayondi G, Isaacson A, Davey S, Mabuta J, Mmalane M, Gaolathe T, Essex M, Lockman S, Makhema J, Shapiro RL. Neural-Tube Defects and Antiretroviral Treatment Regimens in Botswana. N Engl J Med. 2019. Aug 29;381(9):827–840. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1905230. Epub 2019 Jul 22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zash R, Holmes L, Diseko M et al. Update on neural tube defects with antiretroviral exposure in the Tsepamo study, Botswana Zash R, Holmes L, Diseko M, et al. Update on neural tube defects with antiretroviral exposure in the Tsepamo study, Botswana. 23rd International AIDS Conference; vi. In 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lockman S, Brummel SS, Ziemba L, Stranix-Chibanda L, McCarthy K, Coletti A, et al. Efficacy and safety of dolutegravir with emtricitabine and tenofovir alafenamide fumarate or tenofovir disoproxil fumarate, and efavirenz, emtricitabine, and tenofovir disoproxil fumarate HIV antiretroviral therapy regimens started in pregnancy (IMPAACT 2010/VESTED): a multicentre, open-label, randomised, controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2021. Apr 3;397(10281):1276–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Committee Opinion No. 700 Summary: Methods for Estimating the Due Date. Obstet Gynecol. 2017. May 1;129(5):967–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Division of AIDS. Division of AIDS table for grading the severity of adult and pediatric adverse events. … Allergy Infect Dis Div AIDS [Internet]. 2014;(August):1–21. Available from: http://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&btnG=Search&q=intitle:DIVISION+OF+AIDS+TABLE+FOR+GRADING+THE+SEVERITY+OF+ADULT+AND+PEDIATRIC+ADVERSE+EVENTS#0 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Center for Drug Evaluation and Research | CDER | FDA [Internet]. [cited 2022 Jun 7]. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/about-fda/fda-organization/center-drug-evaluation-and-research-cder

- 15.HIVdb Program: Sequence Analysis - HIV Drug Resistance Database [Internet]. [cited 2022 Mar 22]. Available from: https://hivdb.stanford.edu/

- 16.Kalbfleisch John D., and Prentice Ross L.. The statistical analysis of failure time data. John Wiley & Sons, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cohan D, Natureeba P, Koss CA, Plenty A, Luwedde F, Mwesigwa J, Ades V, Charlebois ED, Gandhi M, Clark TD, Nzarubara B, Achan J, Ruel T, Kamya MR, Havlir DV. Efficacy and safety of lopinavir/ritonavir versus efavirenz-based antiretroviral therapy in HIV-infected pregnant Ugandan women. AIDS. 2015. Jan 14;29(2):183–91. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lawn JE, Osrin D, Adler A, Cousens S. Four million neonatal deaths: counting and attribution of cause of death. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2008. Sep;22(5):410–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2008.00960.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lockman S, Brummel SS, Ziemba L, Stranix-Chibanda L, McCarthy K, Coletti A, et al. Efficacy and safety of dolutegravir with emtricitabine and tenofovir alafenamide fumarate or tenofovir disoproxil fumarate, and efavirenz, emtricitabine, and tenofovir disoproxil fumarate HIV antiretroviral therapy regimens started in pregnancy (IMPAACT 2. Lancet. 2021;397(10281):1276–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rasmussen KM, Abrams B, Bodnar LM, Butte NF, Catalano PM, Maria Siega-Riz A. Recommendations for weight gain during pregnancy in the context of the obesity epidemic. Obstet Gynecol. 2010. Nov;116(5):1191–5. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181f60da7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fowler MG, Qin M, Fiscus SA, Currier JS, Flynn PM, Chipato T, et al. Benefits and Risks of Antiretroviral Therapy for Perinatal HIV Prevention. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(18):1726–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zash R, Jacobson DL, Diseko M, Mayondi G, Mmalane M, Essex M, Gaolethe T, Petlo C, Lockman S, Holmes LB, Makhema J, Shapiro RL. Comparative safety of dolutegravir-based or efavirenz-based antiretroviral treatment started during pregnancy in Botswana: an observational study. Lancet Glob Health. 2018. Jul;6(7):e804–e810. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30218-3. Epub 2018 Jun 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kintu K, Malaba TR, Nakibuka J, Papamichael C, Colbers A, Byrne K, Seden K, Hodel EM, Chen T, Twimukye A, Byamugisha J, Reynolds H, Watson V, Burger D, Wang D, Waitt C, Taegtmeyer M, Orrell C, Lamorde M, Myer L, Khoo S; DolPHIN-2 Study Group. Dolutegravir versus efavirenz in women starting HIV therapy in late pregnancy (DolPHIN-2): an open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet HIV. 2020. May;7(5):e332–e339. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3018(20)30050-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Update of recommendations on first- and second-line antiretroviral regimens. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2019. (WHO/CDS/HIV/19.15). Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data in this study cannot be made publicly available due to ethical restrictions in the study’s informed consent documents and in the IMPAACT Network’s approved human subjects protection plan; public data availability could compromise participant confidentiality. However, data, including participant data with partially identifying information, are available to interested researchers on request to the IMPAACT Statistical and Data Management Center’s Data Access Committee (sdac.data@fstrf.org), with the agreement of the IMPAACT Network.