Abstract

Neutrophils are major effectors and regulators of the immune system. They play critical roles not only in the eradication of pathogens but also in cancer initiation and progression. Conversely, the presence of cancer affects neutrophil activity, maturation, and lifespan. By promoting or repressing key neutrophil functions, cancer cells co-opt neutrophil biology to their advantage. This co-opting includes hijacking one of neutrophils’ most striking pathogen defense mechanisms: the formation of neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs). NETs are web-like filamentous extracellular structures of DNA, histones, and cytotoxic granule-derived proteins. Here, we discuss the bidirectional interplay by which cancer stimulates NET formation, and NETs in turn support disease progression. We review how vascular dysfunction and thrombosis caused by neutrophils and NETs underlie an elevated risk of death from cardiovascular events in cancer patients. Finally, we propose therapeutic strategies that may be effective in targeting NETs in the clinical setting.

Keywords: neutrophils, NETs, cancer, metastasis, neutrophil extracellular traps, tumor

Brief/eTOC

Adrover et al. discuss the bidirectional interplay between neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) and cancer, review how vascular dysfunction and thrombosis caused by neutrophils and NETs underlie an elevated risk of cardiovascular events in cancer patients, and propose therapeutic strategies that may be effective in targeting NETs in the clinical setting.

Introduction

Neutrophils are the main leukocyte population in human blood and “first responders” under inflammatory conditions1. They exist in circulation for approximately 12h2,3 and have, until recently, been considered uniform, endpoint effector cells protecting against invading pathogens. This oversimplified view of neutrophil biology has slowed progress on understanding their role in chronic diseases, including cancer4. However, over the last decade, the roles of neutrophils in cancer biology have been receiving more attention; they are now considered major players within the tumor microenvironment (TME) and have been functionally implicated in all stages of cancer progression. Neutrophils promote tumor initiation, mainly through the inflammatory production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) or protease release5–7. They also regulate tumor progression, with both pro- and anti-tumor functions8. Depending on the context, neutrophils can either inhibit metastasis directly through cytotoxic activity or support metastasis by promoting immunosuppression, angiogenesis, cancer cell motility, and epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT)9–17. Nonetheless, most studies on neutrophils in cancer have reported on pro-tumor role. Indeed, intratumoral neutrophils were reported to be the most adverse prognostic cell type of all tumor-infiltrating leukocyte populations, based on a pan-cancer assessment of over 3,000 solid tumors from 14 different cancer types18.

Here, we discuss the involvement of neutrophils in cancer initiation, progression, and metastasis. We focus on the role of neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs), as the role of neutrophils in cancer more generally has been recently reviewed elsewhere19,20. We first discuss the effects of cancer on NET formation, including how tumors alter the neutrophil maturation lifecycle, then explore how different NET components affect specific steps of cancer initiation and progression. Finally, we discuss how NETs may underlie the link between cancer and co-morbidities (particularly cardiovascular events and obesity), and provide insights into developing therapeutic strategies to target NETs in the clinical setting.

Neutrophil extracellular traps

As prime effector cells of the immune system, neutrophils possess a wide array of functions to fight invading pathogens: phagocytosis21, ROS generation22, degranulation and the consequent release of proteases and other cytotoxic granule components23, the recruitment of other immune cells24 and the formation of NETs25.

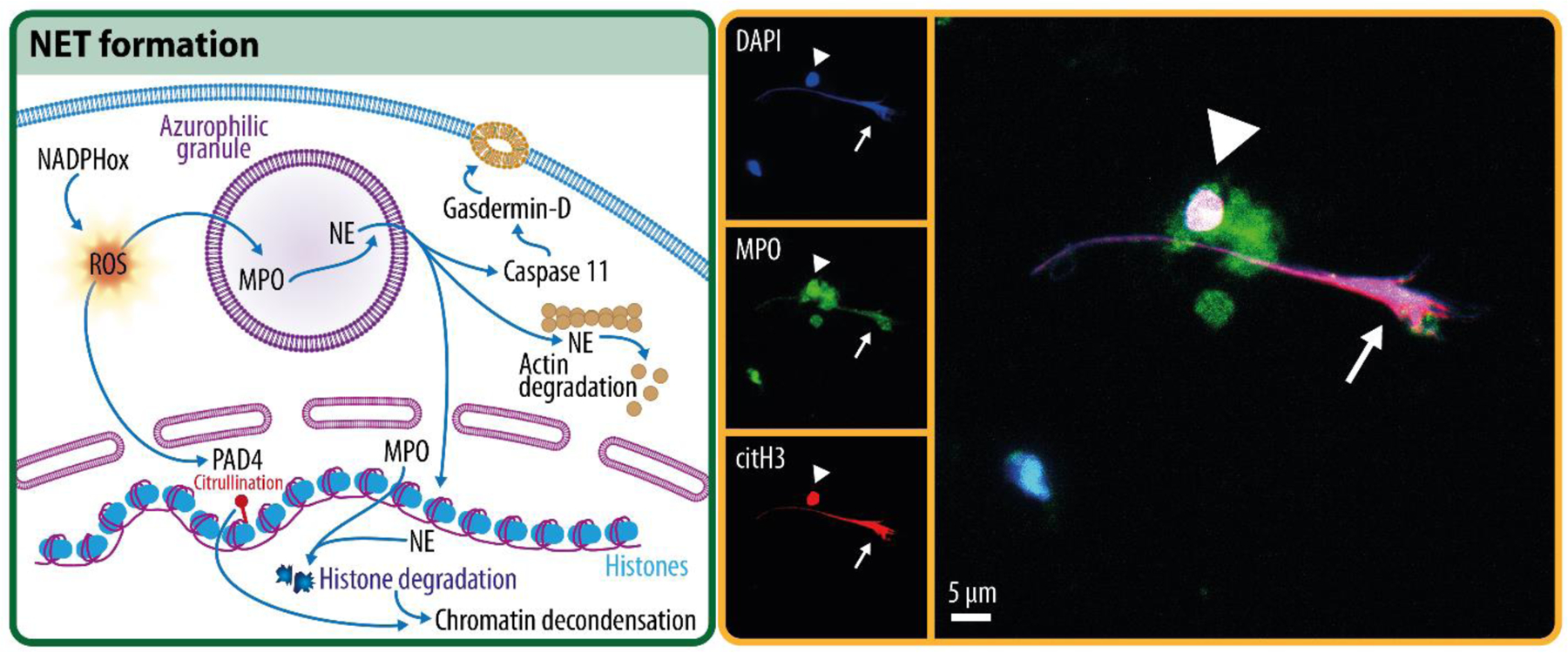

NETs are web-like filamentous extracellular structures released by neutrophils in response to supernumerary25 or oversized26 pathogens. NETs entrap pathogens in a network of DNA, histones, proteases, and other cytotoxic and highly inflammatory compounds, including myeloperoxidase (MPO), lactotransferrin, LL-37, calprotectin, bactericidal/permeability increasing protein, and pentraxin 325,27–32. To form NETs (Figure 1), neutrophils decondense their chromatin in a process that requires ROS, neutrophil elastase (NE), myeloperoxidase activity, and histone citrullination33–35. Within NET-forming neutrophils, NE degrades the actin cytoskeleton, thereby impeding their ability to move and phagocytose36. The nuclear membrane is also dismantled, causing the nuclear contents to blend with the cytotoxic cargo released from the granules37. Lastly, NETs are released into the extracellular space following the loss of plasma membrane integrity, a process involving gasdermin-D polymerization38–40. NET formation usually leads to the lytic death of the neutrophil, termed “NETosis”37; however, non-lytic forms of NET formation have also been reported41,42.

Figure 1: NET formation.

Overview schematic of key steps in the process of NET formation (left), and a confocal microscopy image of a NET (right, arrow), showing the overlap of DNA (DAPI), myeloid peroxidase (MPO), and citrullinated histone 3 (citH3), which are commonly used to define a NET. Note the presence of a neutrophil in the process of forming a NET showing citrullinated histone 3, DNA, and MPO overlap prior to membrane rupture (arrowhead).

Given that NETs form through a cellular “suicidal” process and indiscriminately affect both pathogens and host tissues upon their release, the formation of NETs can be thought of as a last-resort pathogen defense mechanism. However, NETs are produced in response to many different pathogens25,26,43–46, and using extracellular DNA traps to defend against pathogens is an evolutionarily conserved innate immune mechanism found in social amoeba47 and plants48. Besides the pathogen response, NETs are also released in response to sterile injuries49, although their purpose in this setting is less clear. Many inflammatory mediators that induce NETs (e.g., interleukin 8 [IL-8, or C-X-C Motif Chemokine Ligand 8, CXCL8], CXCL1, mitochondrial DNA, or nitric oxide) are shared between sterile and non-sterile injuries, suggesting that NET deployment under sterile conditions may be coincidental50. However, NETs also have anti-inflammatory functions. For example, NETs with associated proteases can act as cytokine- or chemokine-degrading scaffolds to dampen further inflammation51. Additionally, they can promote T cell exhaustion through immunosuppressive ligands embedded within their chromatin, such as programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1)52. Nevertheless, due to their high cytotoxicity, NETs are most commonly reported to be detrimental in sterile injuries53.

NETs are coated with granule-derived, lytic, cationic antimicrobial peptides54; proteases; and histones, which are highly cytotoxic to pathogens and bystander host cells alike55,56. Dysregulated NET formation can inflict collateral damage to healthy tissues; highly vascularized organs, e.g., lung, kidney, and liver, are particularly vulnerable31,32,57,58. As a consequence, NET-induced damage has been implicated in several conditions: lupus59, periodontitis60, atherosclerosis56,61,62, thrombosis63,64, acute lung injuries26,26,58,65–67, sepsis68, psoriasis69, diabetes70,71, and cancer72–76.

NETs are induced in cancer through various mediators. Ex vivo, inflammatory molecules released from cancer cells [e.g., IL-8/CXCL8, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF), CXCL1, CXCL2, Cathepsin C, and Toll-like receptor (TLR) ligands76–81] can induce NETs, although data confirming that these molecules induce NETs in vivo are largely lacking. Tumor-derived exosomes can also induce NETs, coinciding with enhanced cancer-associated thrombosis82. Additionally, cells within the TME, such as cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) and platelets, can induce NETs. In mouse models of melanoma, and lung and pancreatic cancer, CAFs induce NETs by secreting amyloid β83. Tumors also activate platelets84, which, in turn, promote intravascular NET formation85. Activated platelets induce NETs, e.g., by releasing high mobility group box 1 protein (HMGB1)86 or via P-selectin87, which may act on neutrophils in both soluble or cell-bound forms. Besides specific cell populations, the state of the microenvironment is also relevant; for example, cancer cells experiencing hypoxia—as frequently observed in solid tumors—may have an enhanced ability to induce NETs88. The presence of NETs in aggressive tumors is therefore common, and hallmark features of NETs, including a citrullinated form of histone 3, are prognostic in the clinical setting89,90. Intriguingly, several NET-inducing molecules supplied by cancer cells serve multiple functions in neutrophil biology. For example, CXCL1, CXCL2, and IL-8 are major neutrophil recruitment factors91, while G-CSF and CXCL1 regulate granulopoiesis and neutrophil efflux from bone marrow92–94. Thus, tumors can hijack many aspects of basic neutrophil biology, including their maturation, trafficking, and effector functions.

Influence of cancer on the neutrophil lifecycle

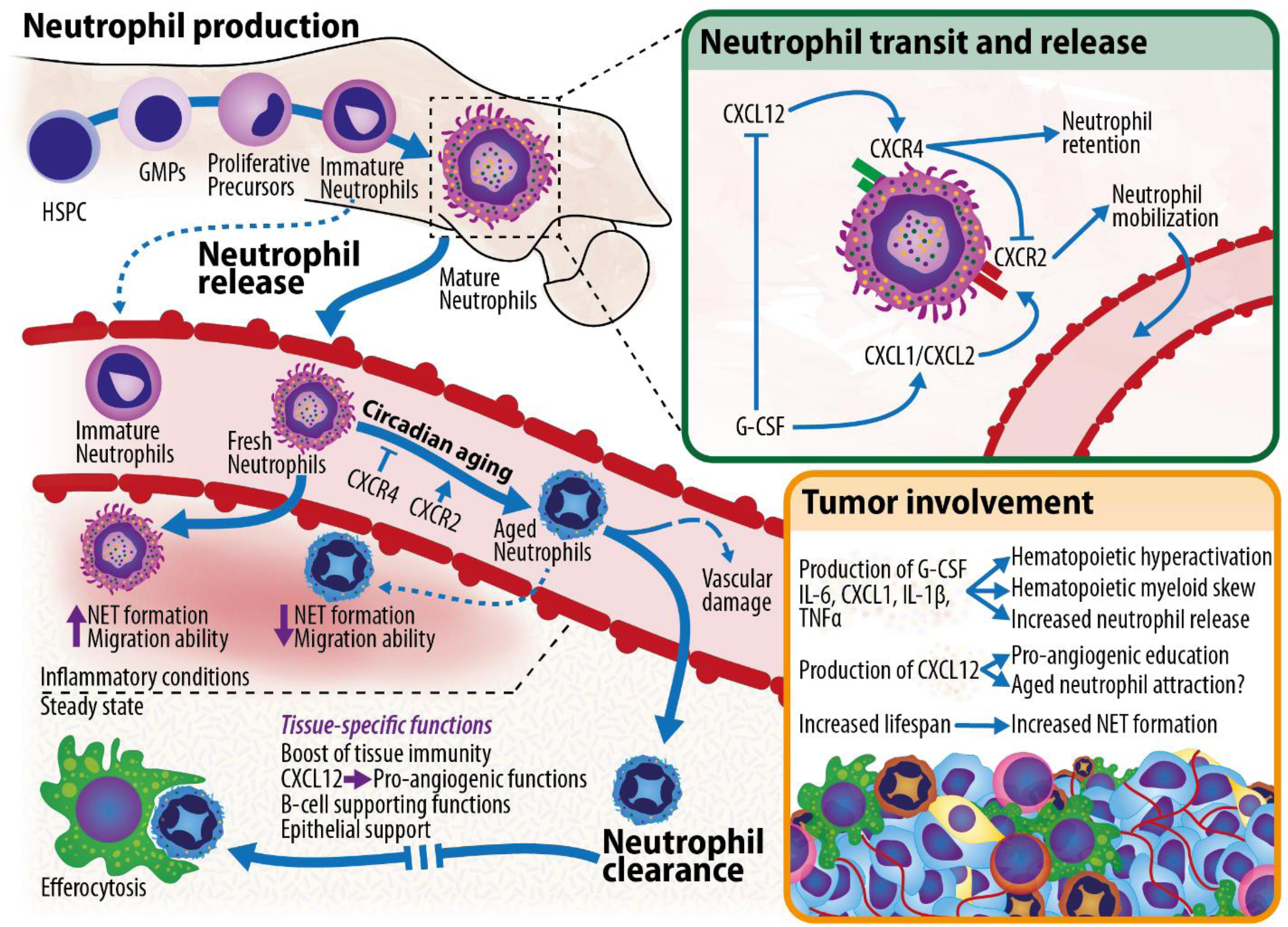

The neutrophil lifecycle and neutrophil maturation are tied to the acquisition of effector functions, including the ability to form NETs and migrate. Therefore, disentangling how cancer alters neutrophil maturation is key to understanding the impact of NETs on cancer. Neutrophils are produced in the bone marrow within hematopoietic cords surrounded by venous sinuses. One fascinating feature of neutrophils is their short lifespan95, which under normal conditions, is less than one day following release into the bloodstream2. The reason for their short lifespan is unclear, but may be a guard against the damaging potential of their vast cytotoxic arsenal58. Many factors that regulate the neutrophil lifecycle under normal conditions are highly expressed by tumors, leading to dysregulated neutrophil maturation, lifespan, and effector functions in cancer (Figure 2). For instance, tumors can induce the early release of immature, immune-suppressive neutrophils by producing G-CSF96. In the following section, we summarize the main steps of the neutrophil lifecycle, the influence of lifecycle on NET formation, and how cancer changes the lifecycle.

Figure 2: The neutrophil lifecycle.

Overview of neutrophils’ lifecycle, from their production in the bone marrow compartment, to their release into circulation, to their subsequent circadian aging, and to their final clearance into the tissues, where they are educated to perform specific functions before being disposed of through efferocytosis by tissue-resident macrophages. Top right: signals governing neutrophil mobilization from the bone marrow. Bottom right: mechanisms through which the tumor can affect the neutrophil lifecycle. HSPC (hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell); GMP (granulocyte-monocyte progenitor).

Infancy.

Neutrophils are produced from hematopoietic stem cells that give rise to proliferative multipotent, common myeloid, and granulocyte-monocyte progenitors (GMPs). The latter, via committed proliferative neutrophil precursors97,98, ultimately differentiate into mature neutrophils. Neutrophil maturation is governed by the complex interplay of several transcription factors: PU.1, CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein alpha (C/EBPα), CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein epsilon (C/EBPε), Growth Factor Independent 1 (Gfi-1), and GATA-binding factor 1 (GATA-1)99. Immature neutrophils are less effective at forming NETs than their mature counterparts100–102.

Adolescence.

Recently generated neutrophils spend 4–6 days in the bone marrow before their release into the circulation3. This release is controlled by C-X-C motif chemokine receptor 2 (CXCR2, mobilization-promoting) and CXCR4 (retention-promoting) signals103,104 and follows a circadian rhythm: in mouse, neutrophils are released from the marrow into circulation during the night2,105. In homeostasis, sympathetic innervation controls the rhythmic, circadian expression of CXCL12, the ligand for CXCR4, in bone marrow stromal cells106,107. G-CSF promotes mobilization by decreasing CXCL12 expression in the bone marrow108 while simultaneously increasing the expression of CXCR2 ligands (CXCL1 and CXCL2) in bone marrow endothelial cells103. “Fresh” or “young” neutrophils, newly released from the bone marrow, stay in circulation for less than one day before being cleared into tissues.

Maturity.

Within the blood, fresh neutrophils undergo neutrophil “aging”, a process of phenotypic changes, before being cleared out of circulation2. This process is also circadian: it maximizes immune readiness during the active phase of the organism, when pathogen encounter is more likely, while minimizing potential collateral damage to healthy tissues from overactive neutrophils during the resting period. Control of neutrophil aging is cell-intrinsic and -extrinsic. Cell-intrinsic mechanisms are driven by the core molecular clock machinery to induce circadian CXCL2 expression, which promotes neutrophil aging through autocrine CXCR2 signaling58,109. External cues also guide the process: engaging the CXCL12-CXCR4 axis dominantly blocks CXCR2 signaling103 in an AKT- and mTOR-dependent manner110, effectively inhibiting aging. As CXCL12 is highly expressed in the bone marrow107, the aging process does not start until neutrophils are released into circulation105. CXCL12 levels in plasma show a circadian pattern that peaks in antiphase with the number of aged neutrophils, serving as a second circadian control checkpoint109.

As neutrophils age, their transcriptomic and proteomic profiles change, as do their effector functions. Fresh neutrophils have high surface levels of L-selectin (CD62L) and CXCR2 and low levels of CXCR4. As they age, CD62L and CXCR2 expression decreases, while CXCR4 expression increases111. They also slowly degranulate, reducing their cytotoxic potential before being cleared to the tissues58. Fresh neutrophils have higher migration capacity to inflamed tissues, while aged neutrophils are preferentially recruited to tissues in homeostasis109, where they can be reprogrammed to perform tissue-specific functions112. Aged neutrophils can cause more intravascular damage109,113 and have increased phagocytic capacity114 than fresh neutrophils. In terms of NET formation, there are conflicting reports: fresh neutrophils release NETs more efficiently in response to inflammatory stimuli than their aged counterparts58,110, but increased NET formation by aged neutrophils has also been reported113. This discrepancy may be due to differences in experimental models, such as whether aged neutrophils were isolated under physiological conditions58 or from animals where aged neutrophils in blood were enriched by blocking extravasation into tissues113.

End-of-lifespan.

Once neutrophils have fully matured and been cleared out of circulation, they enter their final lifecycle stage. It was previously thought that neutrophils were exclusively cleared from blood to the bone marrow, liver, and spleen115,116. However, recent data show that during homeostasis, neutrophils are cleared into virtually all tissues117, and are removed at the end of their life by tissue-resident macrophages118–120. Before elimination, neutrophils in tissues provide immune surveillance (mainly during the night, the active phase in mice)109. In the lung, liver, and intestine, neutrophils gain pro-angiogenic functions; in the spleen, they support B cells; and in the skin, they exert epithelial and connective tissue-supporting functions112,121. Neutrophil lifespan varies dramatically between organs, likely reflecting differences in tissue-specific functions112. Finally, despite their short lifespan, neutrophils are continuously being produced, rhythmically released, and cleared in great numbers, allowing them to function as a phenomenal collective workhorse.

Cancer and the neutrophil lifecycle.

Cancer can affect the neutrophil lifecycle, as cancer cells often express G-CSF and/or CXCL1122,123, which can promote granulopoiesis and drive neutrophil mobilization into the bloodstream. Other cytokines expressed by tumors—e.g., IL-6, IL-1β, interferon gamma (IFN-γ), and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α)—also enhance the production and mobilization of neutrophils from the bone marrow. This process, known as emergency granulopoiesis, can lead to an expansion of mature, fresh neutrophils in circulation—neutrophils that have increased NET formation ability58,124. However, emergency granulopoiesis can also lead to the release of immature neutrophil populations with reduced NET formation capacity101. It is unclear exactly what determines whether mature versus immature neutrophils leave the bone marrow, but the process likely depends on a balance between the signals that promote granulopoiesis versus release. Emergency granulopoiesis, in both infection and cancer, also induces the release of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) that can circulate and seed in other tissues to induce extramedullary hematopoiesis, which further increases hematopoietic output125–128.

Skewing of immune cells toward myeloid lineages is correlated with worse prognosis in breast, cervical, esophageal, gastrointestinal, and lung cancers129, likely caused by cytokines, including G-CSF, secreted by cancer cells122. High numbers of neutrophils or an elevated neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) in blood are associated with poor prognosis in many cancers130–133. Consistently, during treatments, a low NLR in blood may indicate improved responses e.g., following immune checkpoint blockade in non-small cell lung cancer134.

As humans age, HSPCs become skewed toward myelopoiesis135, resulting in a bias toward myeloid cells over lymphoid cells. Age also contributes to clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential (CHIP)136, a condition in which genetic mutations in hematopoietic stem cells grant a selective proliferative advantage without meeting the definition of cancer137, although it can sometimes progress to leukemia138. Cancer patients with CHIP are at higher risk of progression and recurrence after treatment139,140. Interestingly, one common mutation driving CHIP is an activating mutation of JAK2 that enhances proliferation and is associated with a 12-fold higher risk of coronary heart disease and thrombosis141. Moreover, clonal hematopoiesis with JAK2 mutation enhances neutrophils’ ability to form NETs142, which could explain the increased risk of atherosclerosis, given the role of NETs in atherogenesis143.

Other alterations at the level of the bone marrow can also affect neutrophil behavior. “Trained immunity” is a long-term memory mechanism that causes a shift in the function of innate immune cells against subsequent (and often unrelated) immune challenges144. It is mediated by long-term epigenetic and metabolic rewiring of progenitor cells in the bone marrow145,146. Unlike adaptive immune system memory mechanisms, trained immunity is not antigen-specific147. Trained immunity can be elicited by exogenous pathogen-associated molecular patterns, endogenous danger-associated molecular patterns148, and even by dietary components149. Studies have shown that canonical trained immunity (e.g., caused by β-glucan or Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccination) induces a myeloid bias in hematopoiesis144,146, leads to long term effects on neutrophil effector functions150, and enhances anti-tumor responses151. In cancer, childhood BCG vaccination significantly decreases lung cancer incidence152, while in bladder cancer, it is used as an adjuvant immunotherapy153 where it can trigger NET formation to mediate tumor-control154. Thus, in this context, trained immunity and NETs are anti-tumor. On the other hand, trained immunity can also be pro-tumor, as innate immune training driven by myocardial infarction drives immunosuppressive phenotypes in myeloid cells that can promote breast cancer155. Thus, trained immunity can positively and negatively affect cancer progression, and further research will be needed to understand these opposing effects.

In addition to the interactions between tumors and the bone marrow, several studies implicate potential interactions with the process of aging and clearance of neutrophils in cancer. As neutrophils age within the circulation, an intriguing possibility is that they may facilitate metastasis by allowing circulating cancer cells to ‘hitchhike’ and follow the neutrophils into tissues. Neutrophil-cancer cell interactions can be governed by CD11b156, which is elevated on the cell surface of aged neutrophils111. Additionally, disseminating cancer cells in blood can be physically guided by NETs73,157. Many cancers express high levels of CXCL12158,159 and may, therefore, attract aged neutrophils, which express higher levels of the CXCL12 receptor CXCR4104,111. Neutrophils infiltrating tumors may be reprogrammed by tumor-derived factors similarly to their reprogramming in normal tissues112. One example is the pro-tumor phenotype of neutrophils that have been exposed to transforming growth factor (TGFβ) in solid tumors12. Aged neutrophils are less efficient at forming NETs during homeostasis, but it is conceivable that the pro-inflammatory milieu of many tumors, which can extend neutrophil lifespan160–163, also increases NET formation. In the context of cystic fibrosis, delayed neutrophil apoptosis leads to an increased likelihood of NET formation164.

The normal circadian changes in neutrophil migration patterns mirror recent findings that breast cancer cells have greater metastatic potential during the “resting” period of both humans and mice, driven by an increase in mitotic gene expression165. This phenomenon raises the possibility that neutrophils and NETs play a role in promoting rest phase-driven metastasis, given that neutrophil numbers in circulation are greatest during this period. Additional studies suggest a role for aged neutrophil clearance in metastasis: more cancer cells home to the lungs during the time of day when neutrophils are actively cleared into tissues, and this diurnal difference in cancer cell homing is lost upon neutrophil depletion117,166. The extent to which these diurnal effects act within the circulation or the target tissues remains unclear72

In summary, cancer can co-opt neutrophils at different stages of their lifecycle, including changing neutrophil aging to alter the neutrophil’s behavior and ability to form NETs. Further research is needed to fully understand the role of bona fide neutrophil aging and aging-related changes in NET formation in cancer.

NET components affecting cancer

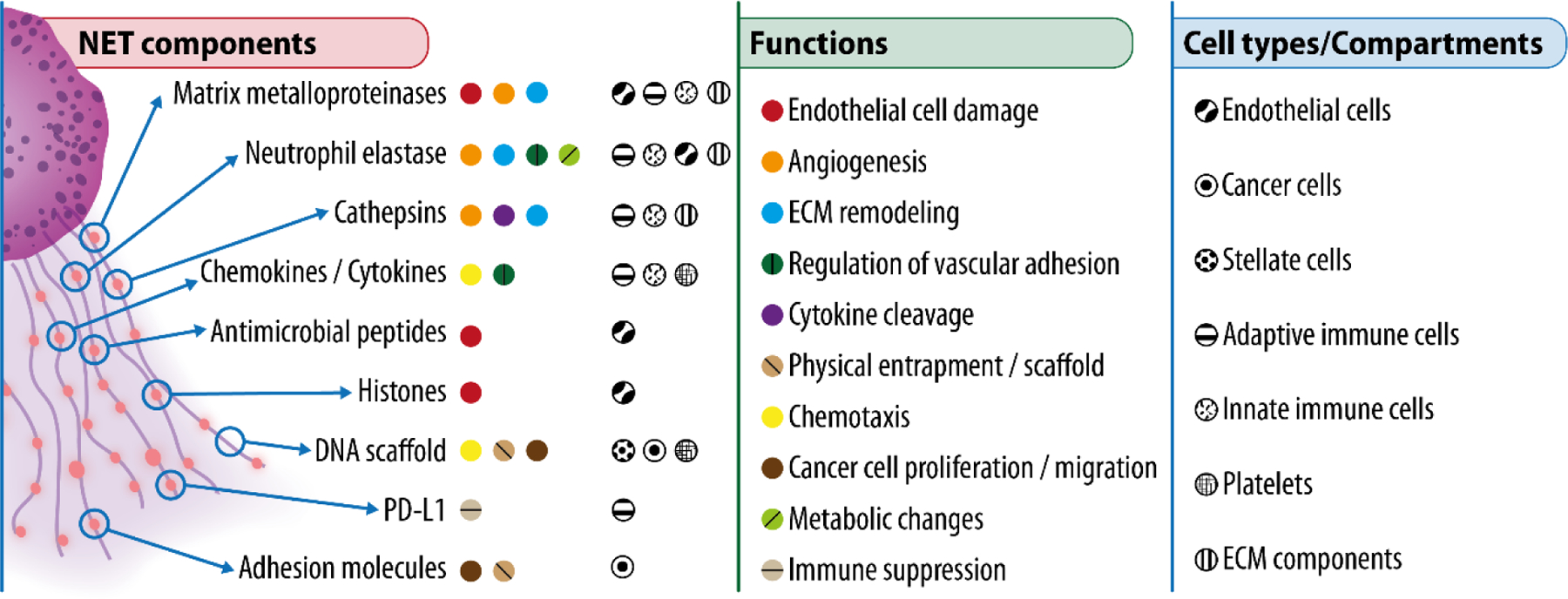

NETs contain diverse antimicrobial components, many of which have been directly implicated in modifying cancer biology. The most well-studied are proteases, which become bound to NET-DNA as neutrophils undergo NET formation. These enzymes elicit broad cytotoxic effects against target cells, as well as proteolytic effects on the vasculature and extracellular matrix (ECM). In the following section, we present key NET components and their effects on cancer progression (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Overview of key NET components.

Main components of NETs (left), their functions in the context of cancer (center), and their main target cells or compartments (right).

Neutrophil elastase (NE).

NE is a serine protease stored in neutrophil azurophilic granules and released into the extracellular space following degranulation. It regulates NET formation by translocating to the nucleus and cleaving histones, thus promoting chromatin decondensation, and by degrading the actin cytoskeleton34,36. In mouse models of lung cancer, host deletion of Elane (encodes NE) results in a profound survival advantage compared to wild-type mice13,167. NE’s proteolytic activities affect cancer biology by modifying the vasculature or surrounding matrix. For instance, NE proteolysis releases growth factors and pro-angiogenic mediators, e.g., vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) or platelet-derived growth factors (PDGFs), from the ECM168. NE can also induce the expression of P-selectin, a vascular luminal adhesion protein, on human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs)169, and can cause dilation of the tumor vasculature to enable cancer cell transmigration during metastasis170. NET-associated NE can also modify the ECM by cleaving laminin and thrombospondin-1 (Tsp-1)72. NE can be taken up by cancer cells to induce aggressive phenotypes by activating the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) pathway13,171, and it can proteolytically cleave the adhesion molecule E-cadherin to promote invasion172. Paradoxically, anti-tumor effects specific to human NE have also been reported; after uptake by cancer cells, its proteolytic activity liberates the death domain of CD95, thereby leading to cancer cell death17. These results highlight potential species-specific effects of neutrophil proteolytic function173.

Matrix metalloproteinase 9 (MMP9).

MMP9 is another key neutrophil protease released into the extracellular space via both degranulation and its association with NETs. MMP9 is part of the zinc metalloproteinase family of proteins that proteolyze the ECM and many other substrates174. MMP9 has been extensively studied, as its activity supports multiple aspects of tumor progression by regulating the TME175. Notably, the first report of MMP9 activity and NETs showed that NET-associated MMP9 can induce vascular dysfunction by causing endothelial cell damage and death through cleavage and activation of endothelial pro-MMP2176. Owing to its ability to regulate vascular phenotypes, neutrophil-produced MMP9 can also induce angiogenesis177, consistent with a landmark finding that MMP9 triggers an “angiogenic switch” during cancer progression178. Despite being abundant in neutrophils, evidence suggests that MMP9 levels may be fine-tuned depending on the state of the host; for example, MMP9 is upregulated in neutrophils in obesity where NET formation can impair the endothelial barrier179. In addition to effects on the vasculature, MMP9 bound to NETs can alter the ECM, specifically laminin, to induce the awakening of quiescent cancer cells72.

Cathepsin G.

Cathepsin G belongs to the chymotrypsin-related serine protease family, encoded within the chymase locus, and is highly enriched within azurophilic granules in neutrophils. Neutrophil-derived cathepsin G is important for killing pathogens180, either intracellularly in phagolysosomes or after release into the extracellular environment, including through NET deployment181. Neutrophil-derived DNA can block the protective activity of endogenous protease inhibitors within tissues such as the lung, to amplify cathepsin G proteolysis182. As a result, NET-bound cathepsin G can cleave and activate metalloproteases and proteolyze many ECM components, enabling cell invasion. In hepatocellular carcinoma models, NET-associated cathepsin G promotes invasive phenotypes of cancer cells183. Cathepsin G can also proteolytically modify chemokines and cytokines to mediate inflammation; for example, cathepsin G’s truncation of CCL15 enhances its ability to attract monocytes almost 1,000-fold184, which may contribute to macrophage accumulation within tumors. Similarly, cathepsin G-mediated cleavage of chemerin, a chemotactic protein, increases the chemotaxis of dendritic cells during early stages of inflammation185. Additionally, the activities of the IL-1 family of cytokines, including IL-18, IL-33, and IL-36186–188 are also enhanced by cathepsin G cleavage. In cancer models, soluble forms of cathepsin G can stimulate angiogenesis via cleavage of pro-MMP9 and subsequent TGFβ activation, leading to VEGF induction189. This echoes the effects of other neutrophil serine proteases on vascular remodeling at sites of inflammation.

Histones and DNA.

Histones within NETs can damage endothelial cells directly, as they are inherently cytotoxic56,190. At sub-cytotoxic concentrations, histones together with DNA can induce pro-inflammatory signaling more potently than DNA alone191–193. Additionally, NET-DNA has both structural and signaling functions194. In mouse models of sepsis induced by cecal ligation and puncture, NET-DNA was shown to physically trap circulating cancer cells to guide them across the vascular barrier into secondary tissues, including the liver73,195. NET-DNA can also function as a scaffold to concentrate protease activity on ECM substrates72. Association with the DNA scaffold has also been proposed to reduce serine protease activity, giving the DNA-bound proteases a potentially different role than their soluble counterparts34. More recently, NET-DNA itself has also been shown to have chemotactic functions, acting as a signaling moiety via the protein CCDC25196. In cancer cells, NET-DNA, recognized by CCDC25, activates the ILK-β-parvin pathway, resulting in enhanced cell proliferation, adhesion, and migration196. NET-DNA has higher levels of 8-hydroxy-2’-deoxyguanosine (8-OHdG), a marker of oxidative damage, than normal genomic DNA196. Interestingly, 8-OHdG is also a recognized risk factor for cancer, atherosclerosis, and diabetes, which all are diseases linked with NETs197,198. Finally, it is likely that partially digested NET-DNA can be taken up by immune cells to trigger signaling from intracellular DNA sensors, such as cyclic GMP-AMP synthase / stimulator of interferon genes 1 (cGas/STING)199, absent in melanoma 2 (AIM2)200,201, or TLR9202. The consequences of NET-DNA’s activation of pattern recognition receptors or cGAS203 remain an active area of research.

Additional NET-bound factors.

Tandem mass spectrometry on NETs isolated from the blood of healthy volunteers has revealed more than 500 NET-affiliated proteins, including adhesion molecules belonging to the integrin (ITGAM, ITGB2, ITGAIIb, ITGAL) and carcinoembryonic Ag cell adhesion molecule (CEACAM; CEACAM1, CEACAM6, CECAM8) families204. Many of these proteins are likely to have both direct and indirect effects on cancer cells. For example, CEACAM1 is found on NETs and directly stimulates colorectal cancer cell adhesion and migration204. β1-integrin, present in NETs, can physically tether NETs to circulating cancer cells, assisting in their dissemination into secondary organs195. NET-bound proteins can also regulate cancer indirectly through their effects on other cells in the microenvironment. For example, PD-L1 can be detected on NETs, resulting in T cell exhaustion and an immunosuppressive TME52. These studies represent an evolving understanding of the roles of the many NET-associated factors in cancer.

Neutrophils and NETs in cancer initiation

Neutrophils and NETs play roles in cancer initiation, either indirectly by exacerbating inflammation or directly by perpetuating genotoxic stress (Figure 4). A direct role for neutrophils in cancer initiation was found in zebrafish models of melanoma, where wounding-induced inflammation increased cancer formation in a neutrophil-dependent manner205. A classical analogy in cancer biology is that tumors are like “wounds that do not heal”206. During wound healing, neutrophils, NETs, and their associated proteases are highly abundant207,208; however, NETs’ role in tissue repair is poorly understood, as neutrophil depletion accelerates wound closure in animal models209. Indeed, NETs can induce chronic wounding and directly impede wound closure, as exemplified by their defining role in the diabetic wound, another “wound that does not heal”71.

Figure 4: NETs in cancer progression.

Overview of the steps of cancer progression in which NETs have been found to play a role, from malignant transformation and cancer initiation to cancer progression, invasion, intravasation, survival in circulation, entrapment, extravasation and, finally, to the establishment of a successful metastasis.

It is estimated that at least 20% of all cancers arise as a direct consequence of various chronic inflammatory conditions210. Specific examples include inflammation stemming from infections with Helicobacter pylori, hepatitis virus B and C, or Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus, or from schistosomiasis, endometriosis, inflammatory bowel disease, thyroiditis, prostatitis, or asbestos211. For each of these inflammatory conditions, neutrophils212,213 and NETs214 are part of the innate immune response to clear pathogens and/or re-establish tissue homeostasis. In a mouse model of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH)-induced tumor development, NETs promoted the onset of hepatocellular carcinoma by orchestrating monocyte-derived macrophage infiltration to the inflamed liver and inflammatory cytokine production215. Thus, NETs can be critical components of a microenvironment that favors cancer initiation.

In addition to supporting tumor formation by exacerbating chronic inflammation, neutrophils may also have direct carcinogenic capacity. Classical literature linked neutrophil production of ROS (which precedes NET formation) with an ability to cause malignant transformation through the induction of mutations and sister chromatid exchanges216–218. More recently, neutrophils were shown to be critical for tumor formation in several chemical carcinogenesis mouse models219–221, although it was not clear whether the neutrophils acted by generating a tumor-permissive microenvironment or by directly inducing mutations. In addition to ROS, neutrophils have been proposed to promote neoplastic transformation by producing genotoxic hypochlorous acid and other reactive molecules generated by MPO during oxidative bursts222,223. Finally, micro-RNAs (miR-23a and miR-155) released by neutrophils promote double-stranded break formation, leading to genomic instability in cancer224,225. Intriguingly, miR-155 can also induce NETs226.

NETs in cancer progression

The emergence of single cell technologies over the past decade has revealed the vast heterogeneity of neutrophil states within tumors19. It is now appreciated that neutrophils are highly plastic cells in cancer, akin to the diverse repertoire of mononuclear phagocytes/macrophages. Some of this heterogeneity may be related to the previously stated differences in neutrophils’ ability to migrate or form NETs at different points in the neutrophil lifecycle. In the following sections, we discuss examples of how NETs contribute to cancer progression (Figure 4).

Progression of the primary tumor.

Following oncogenic transformation, cell proliferation within the primary niche is required to sustain a viable tumor. This process often coincides with early inflammatory events, including the recruitment of neutrophils that can deploy NETs within solid tumors. In most cases, peptidyl arginine deiminase 4 (PAD4) is required for NET formation, and in mouse models of pancreatic cancer, bone marrow transplantation from Pad4 null donors into wild-type recipients prevents NET formation, consequently reducing tumor growth and increasing survival227. The NETs activate pancreatic stellate cells via the receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE), causing stellate cell proliferation and protease secretion, which feeds back to cancer cells to stimulate their proliferation227. These findings suggest that NETs are pro-tumor in the primary tumor niche, similar to their role in more aggressive disease states90. NETs can also promote metabolic changes within the TME. In mouse models of metastatic colorectal cancer, NET-derived NE stimulated TLR4 signaling on tumor cells to enhance mitochondrial production of ATP, thereby increasing primary tumor growth228. Thus, NETs can promote tumor growth through multiple mechanisms.

Invasion and migration.

Bidirectional communication between cancer cells and neutrophils can promote invasion and migration. Several aggressive cancer cell lines induce NET formation, which then stimulates cancer cell invasion and migration76,78,229,230. One mechanism by which NETs stimulate cancer cell migration is through chemotactic effects of NET-DNA on DNA sensors like CCDC25196. Another may be by inducing EMT, which can endow epithelial-derived cancer cells with invasive properties. For example, incubating cancer cells with NETs can downregulate E (epithelial)-cadherin and upregulate mesenchymal proteins, including fibronectin, N (neural)-cadherin, and vimentin, in breast and lung cancer models231,232. By endowing cancer cells with the capacity to leave the primary tumor site, NETs influence early steps of the metastatic cascade.

Angiogenesis.

For tumors to sustain their growth, they must orchestrate the establishment of a sufficient blood supply233. The effects of NETs on the vasculature are well studied. The tumor vasculature is highly torturous and leaky, making it a vulnerable target for NET-mediated destruction. It is conceivable that the loss of vascular integrity in tumors is due in part to the abundance of neutrophils and NETs within the TME. Indeed, NETs can affect endothelial cell-cell contacts and increase permeability, including in the context of metastasis179,234. Moreover, in mouse models of ischemic stroke, NETs can hinder vascular repair235. However, in other disease models, e.g., models of ischemic retinopathies, NETs promote vascular remodeling by clearing and reshaping the senescent, non-functioning retinal endothelium236. Similarly, during angiogenesis, NETs support the proliferation and tube-forming ability of human endothelial cells in vitro234, including in an in vitro model of pancreatic cancer78. In mouse models of different types of cancer, MMP9 promotes angiogenesis177,178,237, further supporting the idea that NET-associated proteases can help tumors establish their needed blood supply. Thus, context is critical for determining the outcome of NET-mediated effects on vascular remodeling.

Formation of an immunosuppressive niche.

NETs can regulate immune cell function to establish an immunosuppressive niche through various means. It has been proposed that the NET-DNA structure may act as a physical barrier that limits contact between cancer cells and cytotoxic80 natural killer or T cells80,238. Consequently, preventing NET formation via PAD4 inhibition improved response to checkpoint inhibitors in vivo80. The presence of immunomodulatory PD-L1 embedded within NETs can also influence adaptive anti-cancer immune responses by causing T cell exhaustion and dysfunction within the TME in liver metastasis mouse models52. Furthermore, NETs can stimulate differentiation of immunosuppressive regulatory T cells via metabolic reprogramming: in mouse models of NASH, NETs increased naïve CD4+ T cell oxidative phosphorylation via TLR4 signaling, which stimulated CD4+ T cell differentiation into regulatory T cells to favor hepatocellular carcinoma development from NASH239. γδ T cells, which are critical for epithelial and mucosal pathogen defense, can also regulate neutrophils. In the context of cancer, IL-17 secreted by activated γδ T cells, likely acting on epithelial cells, increases systemic levels of G-CSF, causing an increased number of neutrophils240,241. This expansion has been shown to suppress CD8+ T cells within both primary pancreatic tumors and metastatic breast tumors in mice240,242. Of note, IL-17 secreted by γδ T cells can promote NET formation, and these NETs may further suppress CD8+ T cell recruitment to tumors242. NET-mediated immunosuppression of CD8+ T cells has also been shown in response to cytotoxic therapies: following radiation, neutrophils are recruited to tumors and form NETs243. In patients with bladder cancer, resistance to radiation therapy is associated with a high neutrophil-to-CD8+ T cell ratio within tumors243. In preclinical models of bladder cancer, digesting NETs with DNase I increased tumor-infiltrating CD8+ T cells after radiation to improve treatment response243. These findings further exemplify how NETs’ immunosuppressive properties can indirectly support tumor growth and impair therapy responses.

Anti-tumor role of NETs.

Like most other immune cells, neutrophils can adopt either pro- or anti-tumor functions14,17,244,245, and this is also the case for NETs. NETs can limit the migration and proliferation of human melanoma cells cultured in vitro246. NETs may also play a role in promoting anti-tumor immune responses. For example, in an in vitro co-culture model, NETs lowered the activation threshold of CD4+ T cells by causing upregulation of CD25 and CD69 and phosphorylation of ZAP70247. Furthermore, injecting NET-DNA and NET proteins into subcutaneous tumors resulted in the recruitment of more T lymphocytes, cancer cell death, and reduced tumor size154. In addition, BCG, which is used to treat bladder cancer, induces NETs, coinciding with the recruitment of T cells, monocytes, and macrophages to early-stage tumors to mediate tumor control154. Beyond cancer, the immunoregulatory functions of NETs have been described in several other disease models. For example, in mouse models of gout, NETs were found to resolve inflammation by degrading cytokines and chemokines51.

NETs can therefore exert both pro- and anti-tumor effects depending on context. One important point that the literature often fails to specify is the precise location where NETs are forming. Tissues and tumors are not homogeneous, and NETs forming in different locations can have different effects. For example, NETs forming inside the vasculature, at the tumor margin, near dormant vs. proliferating cancer cells, or in regions with different types of ECM or immune cell infiltration will likely have different effects. Hence, we believe that understanding the spatial context in which NETs are formed is important for untangling the opposing effects of NETs on cancer. Additionally, understanding neutrophils’ migration patterns and abilities, which depend on their lifecycle stage, will also be important for determining whether NETs can be deployed in a particular location.

NETs promote metastasis

In cancer biology, NETs are most studied in relation to metastasis. NETs are able to guide cancer cells from the primary tumor to the secondary site and contribute to the establishment of proliferating metastatic lesions (Figure 4).

NETs escort cancer cells in transit.

NETs guide cancer cells within the circulation and facilitate extravasation by supporting transmigration across the vascular barrier. Within the circulation, NETs can capture disseminating cancer cells to support metastatic spread. Initial studies using intravital microscopy in mouse models of sepsis, showed that NETs can physically trap circulating cancer cells to enhance liver metastases formation73. Intravascular cancer cell “NET-entrapment” was found to increase liver micrometastases in part through NETs adhesion within liver sinusoids. It was subsequently determined that NET-to-cancer cell adhesion is mediated by β1-integrin, expressed on both cancer cells and NETs195. A similar metastasis-promoting role for intravascular cancer cell “NET-entrapment” was later shown in the context of surgical stress in lung cancer models248. In this context, activated platelets adhering to the circulating cancer cells facilitated entrapment by NETs and metastasis248. These findings may be related to the observation that neutrophils can cluster with cancer cells within the circulation to favor metastasis in patients and mouse models of breast cancer249. NETs also affect the vasculature to promote metastasis. NETs isolated from patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma induce junctional gaps between endothelial cells in vitro, suggesting that NETs may weaken the vascular barrier, thereby facilitating extravasation. Indeed, in a mouse model of postoperative abdominal infectious complications, NETs were shown to promote gastric cancer cell extravasation and metastasis to the liver250. Collectively, NETs play critical roles guiding cancer cells through the vasculature to the metastatic niche.

NETs establish a metastatic niche.

Following their arrival at a secondary site, cancer cells must next colonize the new tissue. This process is aided by the establishment of an altered microenvironment, often termed the pre- or pro-metastatic niche, depending on whether the changes to the microenvironment occur before or after the arrival of the disseminating cancer cells. NETs have been reported to be present in various premetastatic tissues, including liver, lung, and omentum79,90,196. NETs were detected in omental tissues of patients with early-stage ovarian cancer before metastases were detected, and NETs, formed in response to cancer cell-secreted factors, were required for metastasis to the omentum in a mouse model of ovarian cancer79. In the liver, NETs in the premetastatic niche can act as chemotactic factors for cancer cells196. NETs have also been observed in microenvironments harboring growing metastases, such as breast cancer lung metastases, in mice as well as humans76. Also under these circumstances, the metastatic cancer cells were shown to secrete factors to stimulate NET formation, and the NETs were found to be critical for establishing metastases76.

Beyond interactions between NETs and other cell types, NETs also engage with several components of the ECM (Figure 3). Proteases associated with expelled NETs, including NE, cathepsin G, and MMP9, can degrade ECM proteins, such as Tsp-1, to enhance metastasis in mice81,252. In mouse models of experimental sustained inflammation, NET-associated NE and MMP9 were found to proteolyze laminin in the ECM, generating an epitope that stimulates integrin β1 signaling in quiescent cancer cells to trigger their re-entry into the cell cycle, thereby promoting metastatic conversion72. The NET-associated proteases could also degrade Tsp-172. Thus, there is ample evidence that NETs support metastasis within the secondary niche.

NETs and cancer co-morbidities

NETs are important players in the TME, but they impede health beyond promoting cancer. In the 19th century, Trousseau realized that malignancies and thrombotic events were correlated253, and unexplainable thrombotic events are now taken to indicate a possible hidden visceral cancer in clinical practice. The link between cancer and thrombosis is clinically very important, as thromboembolic cardiovascular events are the second most common cause of death in patients with cancer254. Cancer survivors have a higher risk of death from cardiovascular disease than the general population255–257, and up to 50% of cancer patients show postmortem histological evidence of venous thromboembolism258. These relationships are further exacerbated by additional host co-morbidities, e.g., obesity and metabolic syndrome, that impede cardiovascular health. In this regard, cancer can be considered a vascular disease, and multiple host factors likely cross-talk to bolster this relationship (Figure 5).

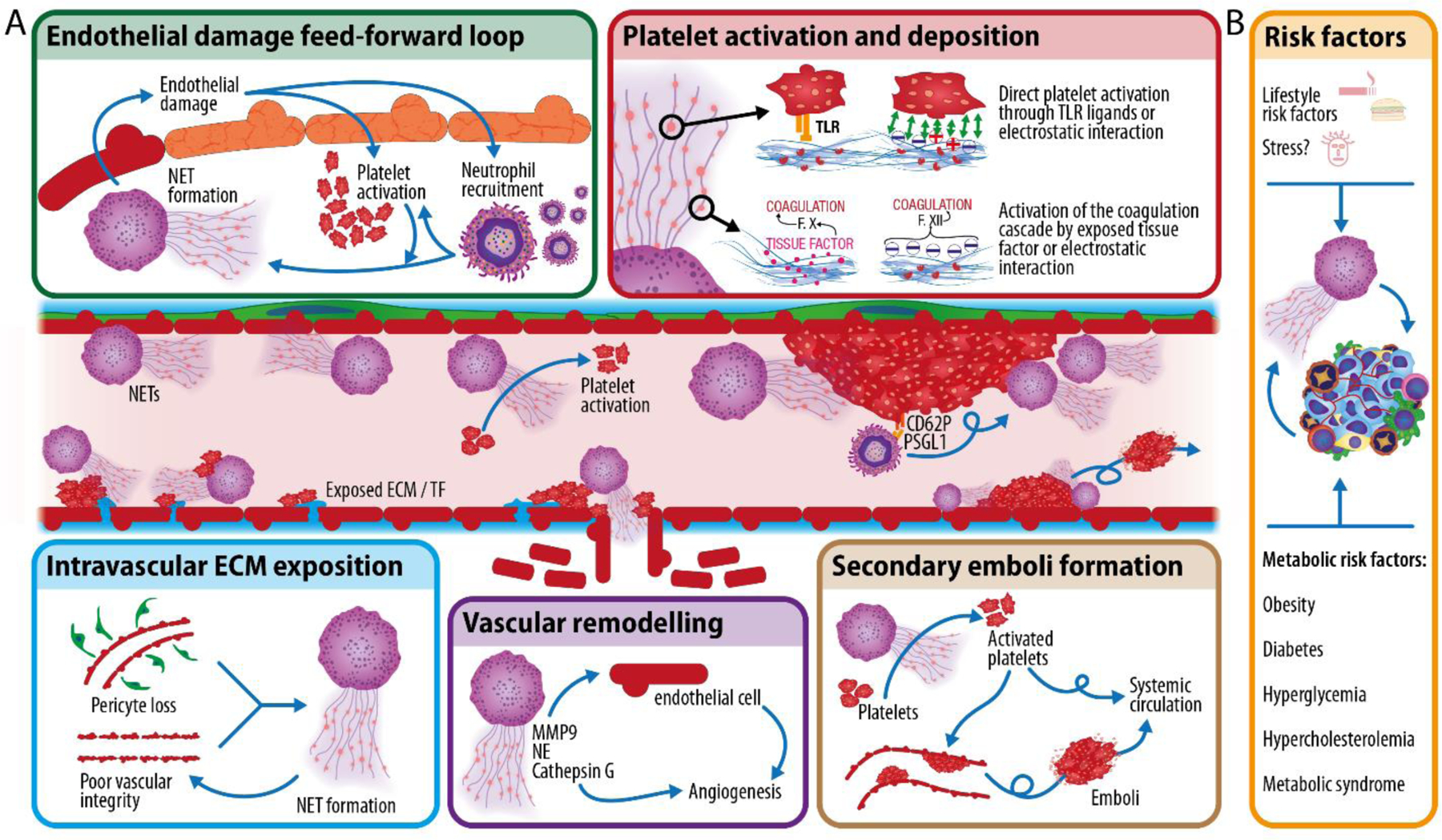

Figure 5: NETs and vascular inflammation.

A) NETs can damage the endothelium and induce platelet activation to form intravascular thrombi (top). Cancer is also a vascular disease (bottom). Intravascular exposition of tissue factor (TF) and extracellular matrix (ECM) components due to pericyte loss and poor vascular integrity in the tumors induces platelet activation and NET formation. NETs, in return, induce vascular remodeling and together with platelets, once activated, promote vascular dysfunction in other organs. B) Various lifestyle risk factors (e.g., smoking, poor diet, and possibly stress), or metabolic risk factors (e.g., obesity, diabetes, hyperglycemia, hypercholesterolemia or metabolic syndrome), likely cross-talk with cancer to amplify the effects of cancer on vascular health.

The tumor vasculature is pro-coagulant, and both cancer cells and the TME release pro-thrombotic compounds259,260. Moreover, the tumor vasculature itself is leaky, mainly resulting from low pericyte coverage261,262, and it is marked by intraluminally-exposed ECM components263. Together, these vascular abnormalities contribute to platelet and neutrophil activation and subsequent NET formation85, leading to severe vascular dysfunction264. In fact, poor vascular integrity, which triggers NETs, indirectly promotes metastasis through varied effects on cancer cells, including hypoxia induction, EMT initiation, and MET activation265. Intravascular NET release also leads to increased tumor angiogenesis via, e.g., NE (discussed above) and MMP9 and latency-associated peptide of TGFβ1, which induce endothelial expression of pro-angiogenic compounds234.

Within the vasculature, NETs play prominent roles in thrombosis: they damage endothelial cells266 and induce aggregation by providing a scaffold for platelet deposition267, exposing pro-coagulant nucleic acids and polyphosphates268, as well as several platelet-activating ligands269. They also expose tissue factor (that activates the coagulation cascade) together with NE (which inhibits the tissue factor inhibition pathway), further inducing thrombosis270,271. Of note, NETs deployed in the brain vasculature can also disrupt the blood-brain barrier272, potentially assisting metastatic spread to the brain. Histones themselves also interact with platelets and activate the intrinsic coagulation cascade273,274. Although platelets are key players in thrombosis, NETs can also induce platelet-independent clots63. Together with other cytotoxic components of neutrophil granules, histones themselves damage endothelial cells56, causing neutrophil recruitment and establishing a feed-forward loop between NETs and platelets that ultimately drives more neutrophil recruitment, more platelet activation, and more NET formation. This feedforward loop leads to thrombi formation, and thrombi themselves can further drive NET formation and neutrophil recruitment86,275, especially in the lower-shear region downstream of the thrombi276. Finally, NETs can induce emboli formation, as exemplified in their role in atheroma plaque destabilization277. In summary, excessive NET formation can induce thrombosis and thromboembolism64, leading to ischemic events and potentially organ failure, and there is compelling evidence that NETs contribute to cancer-associated thrombosis [see for example77,142].

Host metabolism is closely tied to cardiovascular health, and many aspects of metabolic syndrome—including hyperglycemia, hypertension, and hypercholesterolemia—influence neutrophil-specific biology251,278. Obesity is strongly associated with the development of metabolic syndrome and is estimated to underlie 14–20% of all cancer-related mortalities in adults279. Preclinical models of breast cancer have shown that obesity increases NET formation, which impairs vascular integrity in the lungs to enhance permeability and metastasis179,251. Inhibiting NET formation with PAD4 inhibitors or digesting NETs with DNase I are sufficient to restore vascular barrier integrity and reduce obesity-associated lung metastasis179. Clinical studies have also shown that individuals with type 2 diabetes (T2D) display increased circulating levels of NETs due to hyperglycemia-induced NET formation70. Similarly, homocysteine (also a risk factor for T2D when elevated systemically) can stimulate NET formation and platelet aggregation to influence vascular pathologies280, reinforcing the role host factors play in influencing immune and vascular states. A similar finding was reported in patients with severe coronary atherosclerosis, whereby circulating levels of NET markers were elevated in patients compared to healthy subjects281. Finally, endocrinological factors affected by psychological stress can also impact vascular biology and cardiovascular health, although the role of stress in cancer immunology and outcomes is still an emerging area of research282,283. In preclinical models of sickle cell disease, it was found that exposure to chronic stress negatively impacted vascular disease via an increase in aged neutrophils284. Although a direct connection with NETs was not explored, these findings reveal the intricate relationship between host co-morbidities and neutrophil states.

Taken together, it is important to recognize that co-occurrence of certain disease states may confound our current understanding of the mechanisms contributing to cancer disease processes. It is plausible that underlying host conditions perturb neutrophil and NET biology, with cancer exacerbating these effects, but further research is needed. Nevertheless, data strongly support the idea that NETs can drive cancer-associated thrombosis in humans. First, elevated blood levels of citrullinated histones are associated with increased risk of venous thrombotic events in patients with cancer285. Second, cancer-associated arterial microthrombi in autopsy samples contain citrullinated histones286. The fact that neutrophils release NETs in the context of cancer likely contributes to the abnormally high incidence of cardiovascular events, including thromboembolic events, in patients with cancer.

How to target NETs

Given the many roles for NETs in cancer progression, including secondary cardiovascular events, pharmacologically targeting of NETs would have great therapeutic benefit. Unfortunately, drugs targeting NETs remain scarce. There are, nonetheless, several enzymes in the NET formation cascade that have clinically available inhibitors, e.g., NE inhibitors34. One NE inhibitor is sivelestat, which was approved in Japan to treat acute respiratory distress syndrome, but unfortunately failed to improve patient outcomes287. One possible explanation is that NE-independent mechanisms of NET formation have been reported288,289, thus decreasing enthusiasm for NE inhibitors to block NET formation. Another important molecule in NET formation is PAD4, which regulates histone citrullination. Inhibiting PAD4 is highly successful in the experimental setting, where NET formation can be blocked using small molecule inhibitors like Cl-amidine or GSK48462,72,290. Unfortunately, no drug that targets PAD4 is currently approved for human use. Another possible target is gasdermin D, which is a pore-forming molecule involved in pyroptosis291, also required for NET release38–40. Although some reports indicate that gasdermin D is not required for NET formation292, the FDA-approved drug disulfiram efficiently blocks gasdermin D polymerization293 and prevents NET formation40,66,294. This makes disulfiram the first FDA-approved compound to block NET formation, although this activity can be considered off-target as disulfiram is approved for alcohol abuse disorder due to its activity on aldehyde dehydrogenase.

An alternative approach is to target NETs once they have been released. Recombinant DNases can digest the DNA backbone of NETs and are effective in preclinical models [e.g.,72]. An inhaled DNase I formulation (Pulmozyme®) is FDA-approved for human use in cystic fibrosis where it improves symptoms of the disease295. However, inhaled DNase I is unlikely to reach the circulation66, leading to poor efficacy in contexts where NETs are found in the vasculature or in organs other than the lungs. Furthermore, although DNases target the DNA backbone, they leave several NET components behind296, which could be detrimental in certain contexts297. Nonetheless, digesting the NET-DNA scaffold may enhance the proteolytic activity of NET-bound proteases against the NET-released histones and thereby reduce the histones’ pro-inflammatory activity192,193,295.

Besides targeting NETs directly, an alternative therapeutic approach is to target upstream mediators of NET deployment in cancer. Antibodies against IL-8 and CXCR2 inhibitors in combination with immune checkpoint blockade have shown promising results in preclinical cancer models298–301 and are actively being explored in clinical trials for cancer. Similarly, there are approved agents that could be repurposed (for example, antibodies against IL-17, used to treat psoriasis), that can regulate both neutrophil recruitment and NET formation240,242. In addition, C5a can prime neutrophils to form NETs acting on C5aR, and C5aR1 inhibitors are approved for use in antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated small-vessel vasculitis31,302. Finally, inhibiting pattern recognition receptors, e.g., TLRs or cGAS, may hold therapeutic value303,304. NETs can be triggered through TLR8, which detects nucleic acid-containing immune complexes305; in turn, NET-DNA can act as a TLR9 ligand for other innate immune cells, like dendritic cells306,307. How these pathways translate to cancer remain largely unknown; however, such therapies could elicit beneficial effects by targeting NETs against NETs, and also, by dampening inflammation more broadly.

The development of new NET-targeting drugs will be possible as our understanding of the molecular mechanisms leading to NET formation evolves. The COVID-19 pandemic revealed the need for NET inhibitors: although it was clear early during the pandemic that NETs played a role in severe disease, there were limited approaches available to target NETs in COVID-19 patients. So far, there are just two FDA-approved compounds that can target NETs, DNase I (in inhaled form) and disulfiram. The latter can efficiently block NET formation, but it is not specific for NETs and interferes with alcohol metabolism. Further efforts should be devoted to finding drugs able to specifically block NET formation, as they would be potentially useful in many disease contexts, including cancer.

Concluding remarks

In the past decade, neutrophils and NETs have emerged as central regulators of tumor progression, with diverse effects on cancer cells and the microenvironment. Yet many knowledge gaps remain regarding how NETs influence cancer biology. First, although most studies identified tumor-promoting effects of neutrophils and NETs, other studies have shown tumor-inhibiting effects, most often in early-stages of cancer or metastasis244,308. Factors that dictate whether NETs are pro- or anti-tumor are unknown. There are likely to be tissue-specific determinants, given the profound variation in tissue composition, and thus protease substrates or cells, that the NETs can act on. Of note, NETs are present in both the tumor tissue and plasma of cancer patients90,309, and it is likely that NETs released within blood vessels versus tissues have different consequences. The context-dependent effects of NET formation raise another fundamental question: are all NETs are equal? We know very little about whether NET components (e.g., their proteolytic or immunoregulatory components) differ in different contexts, although the diurnal changes of neutrophil granule contents58 suggest that NET-associated proteins may also vary. Finally, how NETs are cleared from tissues and blood is not well understood. Plasma DNases can degrade intravascular NETs63,310, and internalization by macrophages and subsequent intracellular degradation has been proposed as well311, but how NET degradation or its potential dysregulation influences cancer remains largely unexplored. It is conceivable that NET degradation could have a major impact by regulating the amount of time that NETs are present and by generating NET degradation products: proteases and histones released from the NET-DNA scaffold, as well as nucleic acid fragments, may have different functions than intact NETs.

Perhaps the biggest remaining goal in the field is to be able to move neutrophil- and NET-targeted therapies into clinical practice. So far, advancements have been limited, yet we are hopeful that leveraging efforts to target NETs in other conditions, such as COVID-19, or repurposing drugs, such as disulfiram, may accelerate progress toward this goal. Nevertheless, our insights into the functions of neutrophils and NETs in cancer are growing at unprecedented speed, and there is a growing realization that they are attractive targets due to their multifaceted effects on the microenvironment and on the body as a whole.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by funding provided to M.E. by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (1R01CA2374135) and the Department of Defense Breast Cancer Research Program (W81XWH-20-1-0753). Funding was provided to D.F.Q. by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (PJT-159742, PJT-178306) and the Canada Research Chairs Program. J.M.A. is the recipient of a Cancer Research Institute/Irvington Postdoctoral Fellowship (CRI Award #3435). S.A.C.M. is the recipient of a Rosalind Goodman Commemorative Scholarship. X-Y.H is supported by the 2021 AACR-AstraZeneca Breast Cancer Research Fellowship (grant number 21-40-12-HE). The authors wish to thank David Ng for helpful discussions and the reviewers for their thoughtful comments and suggestions.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of Interests

M.E. is a member of the research advisory board for brensocatib for Insmed, Inc.; a member of the scientific advisory board for Vividion Therapeutics, Inc.; a consultant for Protalix, Inc.; and holds shares in Agios. She is also a member of the Cancer Cell advisory board. The rest of the authors declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Mayadas TN, Cullere X, and Lowell CA (2013). The Multifaceted Functions of Neutrophils. Annual Review of Pathology: Mechanisms of Disease 9, 181–218. 10.1146/annurev-pathol-020712-164023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adrover JM, Nicolás-Ávila JA, and Hidalgo A (2016). Aging: A Temporal Dimension for Neutrophils. Trends in Immunology 37, 334–345. 10.1016/j.it.2016.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Summers C, Rankin SM, Condliffe AM, Singh N, Peters a. M., and Chilvers ER. (2010). Neutrophil kinetics in health and disease. Trends in Immunology 31, 318–324. 10.1016/j.it.2010.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nicolás-Ávila JÁ, Adrover JM, and Hidalgo A (2017). Neutrophils in Homeostasis, Immunity, and Cancer. Immunity 46, 15–28. 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Balkwill F, Charles KA, and Mantovani A (2005). Smoldering and polarized inflammation in the initiation and promotion of malignant disease. Cancer Cell 7, 211–217. 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Knaapen AM (2006). Neutrophils and respiratory tract DNA damage and mutagenesis: a review. Mutagenesis 21, 225–236. 10.1093/mutage/gel032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mangerich A, Knutson CG, Parry NM, Muthupalani S, Ye W, Prestwich E, Cui L, McFaline JL, Mobley M, Ge Z, et al. (2012). Infection-induced colitis in mice causes dynamic and tissue-specific changes in stress response and DNA damage leading to colon cancer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 109. 10.1073/pnas.1207829109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coffelt SB, Wellenstein MD, and De Visser KE (2016). Neutrophils in cancer: Neutral no more. Nature Reviews Cancer 16, 431–446. 10.1038/nrc.2016.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chee DO, Townsend CM, Galbraith MA, Eilber FR, and Morton DL (1978). Selective reduction of human tumor cell populations by human granulocytes in vitro. Cancer Res 38, 4534–4539. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lichtenstein A, and Kahle J (1985). Anti-tumor effect of inelammatory neutrophils: Characteristics of in vivo generation and in vitro tumor cell lysis. International Journal of Cancer 35, 121–127. 10.1002/ijc.2910350119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stockmeyer B, Beyer T, Neuhuber W, Repp R, Kalden JR, Valerius T, and Herrmann M (2003). Polymorphonuclear Granulocytes Induce Antibody-Dependent Apoptosis in Human Breast Cancer Cells. The Journal of Immunology 171, 5124–5129. 10.4049/jimmunol.171.10.5124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fridlender ZG, Sun J, Kim S, Kapoor V, Cheng G, Ling L, Worthen GS, and Albelda SM (2009). Polarization of Tumor-Associated Neutrophil Phenotype by TGF-b: “N1” versus “N2” TAN. Cancer Cell 16, 183–194. 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Houghton AM, Rzymkiewicz DM, Ji H, Gregory AD, Egea EE, Metz HE, Stolz DB, Land SR, Marconcini LA, Kliment CR, et al. (2010). Neutrophil elastase-mediated degradation of IRS-1 accelerates lung tumor growth. Nat Med 16, 219–223. 10.1038/nm.2084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Granot Z, Henke E, Comen EA, King TA, Norton L, and Benezra R (2011). Tumor entrained neutrophils inhibit seeding in the premetastatic lung. Cancer Cell 20, 300–314. 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deryugina EI, Zajac E, Juncker-Jensen A, Kupriyanova TA, Welter L, and Quigley JP (2014). Tissue-Infiltrating Neutrophils Constitute the Major In Vivo Source of Angiogenesis-Inducing MMP-9 in the Tumor Microenvironment. Neoplasia 16, 771–788. 10.1016/j.neo.2014.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mensurado S, Rei M, Lança T, Ioannou M, Gonçalves-Sousa N, Kubo H, Malissen M, Papayannopoulos V, Serre K, and Silva-Santos B (2018). Tumor-associated neutrophils suppress pro-tumoral IL-17+ γδ T cells through induction of oxidative stress. PLoS Biol 16, e2004990. 10.1371/journal.pbio.2004990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cui C, Chakraborty K, Tang XA, Zhou G, Schoenfelt KQ, Becker KM, Hoffman A, Chang Y-F, Blank A, Reardon CA, et al. (2021). Neutrophil elastase selectively kills cancer cells and attenuates tumorigenesis. Cell 184, 3163–3177.e21. 10.1016/j.cell.2021.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gentles AJ, Newman AM, Liu CL, Bratman SV, Feng W, Kim D, Nair VS, Xu Y, Khuong A, Hoang CD, et al. (2015). The prognostic landscape of genes and infiltrating immune cells across human cancers. Nat Med 21, 938–945. 10.1038/nm.3909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hedrick CC, and Malanchi I (2022). Neutrophils in cancer: heterogeneous and multifaceted. Nat Rev Immunol 22, 173–187. 10.1038/s41577-021-00571-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Quail DF, Amulic B, Aziz M, Barnes BJ, Eruslanov E, Fridlender ZG, Goodridge HS, Granot Z, Hidalgo A, Huttenlocher A, et al. (2022). Neutrophil phenotypes and functions in cancer: A consensus statement. Journal of Experimental Medicine 219, e20220011. 10.1084/jem.20220011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee WL, Harrison RE, and Grinstein S (2003). Phagocytosis by neutrophils. Microbes and Infection 5, 1299–1306. 10.1016/j.micinf.2003.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nguyen GT, Green ER, and Mecsas J (2017). Neutrophils to the ROScue: Mechanisms of NADPH Oxidase Activation and Bacterial Resistance. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol 7, 373. 10.3389/fcimb.2017.00373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Borregaard N, Sørensen OE, and Theilgaard-Mönch K (2007). Neutrophil granules: a library of innate immunity proteins. Trends in Immunology 28, 340–345. 10.1016/j.it.2007.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leliefeld PHC, Koenderman L, and Pillay J (2015). How neutrophils shape adaptive immune responses. Frontiers in Immunology 6, 1–8. 10.3389/fimmu.2015.00471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brinkmann V, Reichard U, Goosmann C, Fauler B, Uhlemann Y, Weiss DS, Weinrauch Y, and Zychlinsky A (2004). Neutrophil Extracellular Traps Kill Bacteria. Science 303, 1532–1535. 10.1126/science.1092385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Branzk N, Lubojemska A, Hardison SE, Wang Q, Gutierrez MG, Brown GD, and Papayannopoulos V (2014). Neutrophils sense microbe size and selectively release neutrophil extracellular traps in response to large pathogens. Nature Immunology 15, 1017–1025. 10.1038/ni.2987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pham CTN (2006). Neutrophil serine proteases: specific regulators of inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol 6, 541–550. 10.1038/nri1841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jaillon S, Peri G, Delneste Y, Frémaux I, Doni A, Moalli F, Garlanda C, Romani L, Gascan H, Bellocchio S, et al. (2007). The humoral pattern recognition receptor PTX3 is stored in neutrophil granules and localizes in extracellular traps. Journal of Experimental Medicine 204, 793–804. 10.1084/jem.20061301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lauth X, von Köckritz-Blickwede M, McNamara CW, Myskowski S, Zinkernagel AS, Beall B, Ghosh P, Gallo RL, and Nizet V (2009). M1 protein allows Group A streptococcal survival in phagocyte extracellular traps through cathelicidin inhibition. J Innate Immun 1, 202–214. 10.1159/000203645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Urban CF, Ermert D, Schmid M, Abu-Abed U, Goosmann C, Nacken W, Brinkmann V, Jungblut PR, and Zychlinsky A (2009). Neutrophil extracellular traps contain calprotectin, a cytosolic protein complex involved in host defense against Candida albicans. PLoS Pathogens 5. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kessenbrock K, Krumbholz M, Schönermarck U, Back W, Gross WL, Werb Z, Gröne H-J, Brinkmann V, and Jenne DE (2009). Netting neutrophils in autoimmune small-vessel vasculitis. Nat Med 15, 623–625. 10.1038/nm.1959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Papayannopoulos V (2017). Neutrophil extracellular traps in immunity and disease. Nature Reviews Immunology, 1–14. 10.1038/nri.2017.105. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Li P, Li M, Lindberg MR, Kennett MJ, Xiong N, and Wang Y (2010). PAD4 is essential for antibacterial innate immunity mediated by neutrophil extracellular traps. The Journal of Experimental Medicine 207, 1853–1862. 10.1084/jem.20100239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Papayannopoulos V, Metzler KD, Hakkim A, and Zychlinsky A (2010). Neutrophil elastase and myeloperoxidase regulate the formation of neutrophil extracellular traps. Journal of Cell Biology 191, 677–691. 10.1083/jcb.201006052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Metzler KD, Fuchs TA, Nauseef WM, Reumaux D, Roesler J, Schulze I, Wahn V, Papayannopoulos V, and Zychlinsky A (2011). Myeloperoxidase is required for neutrophil extracellular trap formation: implications for innate immunity. Blood 117, 953–959. 10.1182/blood-2010-06-290171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Metzler KD, Goosmann C, Lubojemska A, Zychlinsky A, and Papayannopoulos V (2014). Myeloperoxidase-containing complex regulates neutrophil elastase release and actin dynamics during NETosis. Cell Reports 8, 883–896. 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.06.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fuchs TA, Abed U, Goosmann C, Hurwitz R, Schulze I, Wahn V, Weinrauch Y, Brinkmann V, and Zychlinsky A (2007). Novel cell death program leads to neutrophil extracellular traps. Journal of Cell Biology 176, 231–241. 10.1083/jcb.200606027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sollberger G, Choidas A, Burn GL, Habenberger P, Lucrezia RD, Kordes S, Menninger S, Eickhoff J, Nussbaumer P, Klebl B, et al. (2018). Gasdermin D plays a vital role in the generation of neutrophil extracellular traps. Science Immunology 3. 10.1126/sciimmunol.aar6689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen KW, Monteleone M, Boucher D, Sollberger G, Ramnath D, Condon ND, von Pein JB, Broz P, Sweet MJ, and Schroder K (2018). Noncanonical inflammasome signaling elicits gasdermin D-dependent neutrophil extracellular traps. Sci Immunol 3, eaar6676. 10.1126/sciimmunol.aar6676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Silva CM, Wanderley CWS, Veras FP, Sonego F, Nascimento DC, Gonçalves AV, Martins TV, Colón DF, Borges VF, Brauer VS, et al. (2021). Gasdermin D inhibition prevents multiple organ dysfunction during sepsis by blocking NET formation. Blood, blood.2021011525. 10.1182/blood.2021011525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 41.Peschel A, and Hartl D (2012). Anuclear neutrophils keep hunting. Nature Medicine 18, 1336–1338. 10.1038/nm.2918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yipp BG, Petri B, Salina D, Jenne CN, Scott BNV, Zbytnuik LD, Pittman K, Asaduzzaman M, Wu K, Meijndert HC, et al. (2012). Infection-induced NETosis is a dynamic process involving neutrophil multitasking in vivo. Nature Medicine 18, 1386–1393. 10.1038/nm.2847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Urban CF, Reichard U, Brinkmann V, and Zychlinsky A (2006). Neutrophil extracellular traps capture and kill Candida albicans and hyphal forms. Cellular Microbiology 8, 668–676. 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2005.00659.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Abdallah DSA, Lin C, Ball CJ, King MR, Duhamel GE, and Denkers EY (2012). Toxoplasma gondii triggers release of human and mouse neutrophil extracellular traps. Infection and Immunity 80, 768–777. 10.1128/IAI.05730-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Saitoh T, Komano J, Saitoh Y, Misawa T, Takahama M, Kozaki T, Uehata T, Iwasaki H, Omori H, Yamaoka S, et al. (2012). Neutrophil Extracellular Traps Mediate a Host Defense Response to Human Immunodeficiency Virus-1. Cell Host & Microbe 12, 109–116. 10.1016/j.chom.2012.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Thanabalasuriar A, Scott BNV, Peiseler M, Willson ME, Zeng Z, Warrener P, Keller AE, Surewaard BGJ, Dozier EA, Korhonen JT, et al. (2019). Neutrophil Extracellular Traps Confine Pseudomonas aeruginosa Ocular Biofilms and Restrict Brain Invasion. Cell Host & Microbe 25, 526–536.e4. 10.1016/j.chom.2019.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang X, Zhuchenko O, Kuspa A, and Soldati T (2016). Social amoebae trap and kill bacteria by casting. Nature Communications 6, 1–9. 10.1038/ncomms10938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wen F, White GJ, VanEtten HD, Xiong Z, and Hawes MC (2009). Extracellular DNA is required for root tip resistance to fungal infection. Plant Physiol 151, 820–829. 10.1104/pp.109.142067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jorch SK, and Kubes P (2017). An emerging role for neutrophil extracellular traps in noninfectious disease. Nature Medicine 23, 279–287. 10.1038/nm.4294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liu L, Mao Y, Xu B, Zhang X, Fang C, Ma Y, Men K, Qi X, Yi T, Wei Y, et al. (2019). Induction of neutrophil extracellular traps during tissue injury: Involvement of STING and Toll-like receptor 9 pathways. Cell Prolif 52, e12579. 10.1111/cpr.12579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schauer C, Janko C, Munoz LE, Zhao Y, Kienhöfer D, Frey B, Lell M, Manger B, Rech J, Naschberger E, et al. (2014). Aggregated neutrophil extracellular traps limit inflammation by degrading cytokines and chemokines. Nat Med 20, 511–517. 10.1038/nm.3547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kaltenmeier C, Yazdani HO, Morder K, Geller DA, Simmons RL, and Tohme S (2021). Neutrophil Extracellular Traps Promote T Cell Exhaustion in the Tumor Microenvironment. Front. Immunol 12, 785222. 10.3389/fimmu.2021.785222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mutua V, and Gershwin LJ (2021). A Review of Neutrophil Extracellular Traps (NETs) in Disease: Potential Anti-NETs Therapeutics. Clinic Rev Allerg Immunol 61, 194–211. 10.1007/s12016-020-08804-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Poon IKH, Baxter AA, Lay FT, Mills GD, Adda CG, Payne JAE, Phan TK, Ryan GF, White JA, Veneer PK, et al. (2014). Phosphoinositide-mediated oligomerization of a defensin induces cell lysis. eLife 2014, 1–27. 10.7554/eLife.01808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Saffarzadeh M, Juenemann C, Queisser MA, Lochnit G, Barreto G, Galuska SP, Lohmeyer J, and Preissner KT (2012). Neutrophil extracellular traps directly induce epithelial and endothelial cell death: A predominant role of histones. PLoS ONE 7. 10.1371/journal.pone.0032366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Silvestre-Roig C, Braster Q, Wichapong K, Lee EY, Teulon JM, Berrebeh N, Winter J, Adrover JM, Santos GS, Froese A, et al. (2019). Externalized histone H4 orchestrates chronic inflammation by inducing lytic cell death. Nature 569, 236–240. 10.1038/s41586-019-1167-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cedervall J, Zhang Y, Huang H, Zhang L, Femel J, Dimberg A, and Olsson A-K (2015). Neutrophil Extracellular Traps Accumulate in Peripheral Blood Vessels and Compromise Organ Function in Tumor-Bearing Animals. Cancer Res 75, 2653–2662. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-3299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Adrover JM, Aroca-Crevillén A, Crainiciuc G, Ostos F, Rojas-Vega Y, Rubio-Ponce A, Cilloniz C, Bonzón-Kulichenko E, Calvo E, Rico D, et al. (2020). Programmed “disarming” of the neutrophil proteome reduces the magnitude of inflammation. Nat Immunol 21, 135–144. 10.1038/s41590-019-0571-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Knight JS, Zhao W, Luo W, Subramanian V, Dell AAO, Yalavarthi S, Hodgin JB, Eitzman DT, Thompson PR, and Kaplan MJ (2013). Peptidylarginine deiminase inhibition is immunomodulatory and vasculoprotective in murine lupus. Journal of Clinical Investigation 123, 2981–2993. 10.1172/JCI67390.ex. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.White PC, Chicca IJ, Cooper PR, Milward MR, and Chapple ILC (2016). Neutrophil Extracellular Traps in Periodontitis: A Web of Intrigue. J Dent Res 95, 26–34. 10.1177/0022034515609097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Döring Y, Soehnlein O, and Weber C (2014). Neutrophils Cast NETs in Atherosclerosis: Employing Peptidylarginine Deiminase as a Therapeutic Target. Circ Res 114, 931–934. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.114.303479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Knight JS, Luo W, O’Dell AA, Yalavarthi S, Zhao W, Subramanian V, Guo C, Grenn RC, Thompson PR, Eitzman DT, et al. (2014). Peptidylarginine Deiminase Inhibition Reduces Vascular Damage and Modulates Innate Immune Responses in Murine Models of Atherosclerosis. Circulation Research 114, 947–956. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.114.303312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]