Abstract

Dysregulated cell migration and invasion are hallmarks of many disease states. This dysregulated migratory behavior is influenced by the changes in expression of aquaporins (AQPs) that occur during pathogenesis, including conditions such as cancer, endometriosis, and arthritis. The ubiquitous function of AQPs in migration of diseased cells makes them a crucial target for potential therapeutics; this possibility has led to extensive research into the specific mechanisms underlying AQP-mediated diseased cell migration. The functions of AQPs depend on a diverse set of variables including cell type, AQP isoform, disease state, cell microenvironments, and even the subcellular localization of AQPs. To consolidate the considerable work that has been conducted across these numerous variables, here we summarize and review the last decade’s research covering the role of AQPs in the migration and invasion of cells in diseased states.

Keywords: Cancer, Endometriosis, Cell signaling, Cell volume

Introduction

Dysregulated cell migration is a hallmark of many diseases. Though the exact processes regulating how or why cells migrate across different disease states are still being elucidated, increasing evidence points toward the involvement of a family of water channel proteins, aquaporins (AQPs), as a conserved linchpin throughout these diseased cell migratory events. While AQPs have historically been known to be responsible for passive water transport across the cell membrane, recent work has evidenced the diverse functions of AQPs beyond water homeostasis [1, 2], many of which contribute to mechanisms regulating cell migration. Due to the prevalence of cancer cell migration research, the majority of the work connecting AQPs to cell migration stems from cancer. However, as migration is an indispensable stage in many diseases, researchers have sought to expand their knowledge to identify the roles AQPs play in other disease states. The goal of this review paper is to consolidate, in a comprehensive manner, work connecting AQPs and dysregulated cell migration in cancer and other disease states and introduce potential drug therapies that could help alleviate the burden caused by these diseases.

Cancer

Metastatic cancers account for more than 90% of cancer-related deaths [3]. An indispensable behavior of the metastatic process is cellular migration through heterogeneous microenvironments [4–6]. An incomplete understanding of how and why cancer cells migrate during metastasis has impeded the development of viable metastatic cancer therapies [7]. Given the roles that AQPs have been identified to play in the migration of healthy cells [8, 9] (see also our submitted manuscript), the field has hypothesized that these proteins also play a role in cancer.

Indeed, recent research has identified AQPs as an essential component of cancer cell migration [5, 10]. This section discusses in-depth the factors that mediate AQP expression and localization in cancer cells, the role of AQPs in cancer cell migration and invasion, critical AQP-mediated signaling pathways involved in cancer cell migration, and the prognostic implications of AQPs (Fig. 1). We note that AQPs are also involved in other basic cell processes, such as the cell cycle [11–14], cell proliferation [5, 15], and apoptosis [16–18]; here, we focus on cell migration.

Fig. 1.

The role of aquaporins in cancer progression. There is substantial evidence that AQPs are an indispensable protein in cancer progression and more specifically tumor cell migration. The influence of AQPs on this process can be broadly broken down into four categories that are depicted in this schematic: (1) AQP influence on cancer cell signaling, leading to direct [23, 75, 108, 151] and indirect [13, 14, 20, 38, 78, 81, 93] activation of signaling cascades associated with migration and overall cancer survival; (2) AQP-mediated epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition [40, 48, 55, 73, 78, 93, 97], resulting in more invasive phenotypes [23, 40, 70, 75] associated with poor prognosis; (3) tumor-associated angiogenesis mediated by AQPs [17, 112, 124, 126], providing the tumor with highways to spread throughout the body and the nutrients needed to proliferate; 4) AQPs involvement in cancer metastasis occurs at key stages [23, 105, 130, 131] (note that the role of AQPs in intravasation still has yet to be investigated)

Aquaporin expression

AQP1, AQP3, and AQP5 are the most overexpressed isoforms in cancer cells [19]. While AQP1 and AQP3 are often found in non-diseased tissue, AQP5 is interesting because it is primarily expressed within cancer cells, with increasing expression levels as cancer progresses. Specifically, many tissues seldom express AQP5 (e.g., colonic, breast, lung, bone marrow, etc.); however, as cells become cancerous, they begin to develop a prominent expression of the AQP5 protein [20–23]. These changes in expression can lead to more aggressive phenotypes; in many cases, the level of AQP5 expression correlates with increased lymph node metastasis in patients [24, 25]. On the other hand, some AQP isoforms are downregulated in cancer cells. AQP9, the most abundant aquaglyceroporin in the liver, is heavily downregulated in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) [14]. Though AQP8 is not as widely expressed in healthy colorectal ductal cells, its expression is also downregulated in colorectal tumors [26].

These are just a few examples of the alterations in AQP expression that accompany cancer development and we included them to give the reader context. For a more thorough summary on the changes in AQP expression associated with cancer, we direct the reader to another comprehensive review [10].

Factors mediating aquaporin expression

The changes in AQP expression level and isoform type can vary based on cell type, cancer stage, and even the patient from which cells are derived. To decipher the complexities that prompt changes in AQP expression, researchers have probed specific signaling pathways that are often dysregulated during the progression of cancer. Variables influencing AQP expression in cancer can generally be broken up into three categories: soluble factors, upstream signaling, and alterations in genetic mediators. Intriguingly, there is also recent evidence that physical factors such as hydrostatic pressure can enhance lung cancer cell motility through AQP1 upregulation [27], which opens up new avenues for future research that may link AQPs to cell mechanotransduction.

Soluble factors

Soluble factors broadly refer to a variety of molecules including growth factors, small molecules, and cytokines that help cells signal to one another and sense their surroundings. Expression of epithelial growth factor receptor (EGFR) in tumor cells is usually correlated with a more aggressive cancer phenotype [28]; for instance, increased EGFR expression in esophageal cancer reduces AQP8 (anti-cancer) expression, thus increasing cell migration [29]. In ovarian cancer cells, gastric cancer, and pancreatic cancer cells, EGFR activation via hEGF leads to an overexpression of AQP3, thereby enhancing cell migration and proliferation [30–32]. In part, this overexpression of AQP3 is mediated by activation of the extracellular signal regulated kinase (ERK) in these three tumor types. Similarly, in human colorectal carcinoma (CRC) cells, human epithelial growth factor (hEGF) increases the expression of AQP3 and subsequently, the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/protein kinase B (PI3K/AKT)-mediated migratory capacity of these cells [33].

Other growth factors such as human hepatocyte growth factor (hHGF) regulate AQP3 expression. In human breast and gastric cancer, activation of c-Met via hHGF leads to overexpression of AQP3, likely mediated by the ERK signaling pathway [34, 35]. Human fibroblast growth factor 2 (hFGF-2) induces AQP3 expression in human breast cancer cell lines in a dose-dependent manner, leading to increased cell migration, again likely mediated by PI3K and ERK [36]. In vitro, transforming growth factor β1 (TGF-β1) induces AQP3 expression in human peritoneal mesothelial cells, likely mediated by activation of the ERK/mitogen activated protein kinase (MAPK)/P38 signaling cascade [37]. Aside from growth factors, calcium influx via activation of bradykinin receptor B1/B2 can enhance AQP4 expression and subsequent migration and invasion in U87-MG glioblastoma cells. Activation of AQP4 is mediated by ERK1/2/MAPK/NF-kB pathways [38].

Upstream signaling

AQPs can be affected by signaling initiated intracellularly or extracellularly. For example, estrogen receptors (ERs) can act as transcription factors to regulate AQP expression. Breast cancer cells with higher ER expression have increased AQP3 expression compared to normal tissue [39]. This upregulation of AQP3 was later found to be induced by activation of the estrogen response element (ERE) in the promoter region of the AQP3 gene [40]. In glioblastoma multiform (GBM) cells, ERα expression is high, while ERβ and AQP2 expression are low [41]. By reversing this natural GBM state, overexpressing ERβ and silencing ERα, the expression levels of AQP2, genes ANKFY1, LAX1, and LTBP1 were upregulated. It is noteworthy that these genes are linked to the cells’ invasive potential [41]. Upstream intracellular signaling is also capable of influencing AQP expression. Osmoregulated transcription factor nuclear factor of activated T-cell 5 (NFAT5) suppression leads to a significant reduction in proliferation and migration of cells, in concert with a significant reduction in AQP5 levels [42].

Hypoxia occurs when cells experience oxidative stress, causing an increase in the expression of hypoxia inducible factors (HIFs). HIFs have been connected to the regulation of AQPs, which are able to reduce the load of the oxidative stress. In neuroblastoma, increased AQP1 expression is preceded by an increase in HIF-1α, suggesting that hypoxia influences AQP1 expression, likely mediated by the HIF binding domains in the AQP1 promoter region [43–45]. This HIF-1α induced AQP1 expression leads to an increase in wound healing speed of SH-SY5Y and neuroblastoma Kelly cells [44]. Similarly, there is a correlation between the expression of AQP1 and HIF-1 in breast cancer tissues [46]. In PC-3M cells, the hypoxia-induced increase in expression of AQP1 can occur via Ca2+ and PKC phosphorylation of p38 MAPK [47]. This mechanism and HIF binding to the promoter region of AQP1 are likely the main pathways by which HIF-1 increases AQP1 expression.

Changes in genetic mediators

Among other changes that occur during carcinogenesis, there are alterations in cancer gene expression that can influence AQP expression. First, Tan et al. discovered several epigenetic modifications in salivary gland adenoid cystic carcinoma (ACC); among them, AQP1 is the most promising candidate for an oncogene. AQP1 promoter hypermethylation is found in ACC samples, leading to AQP1 mRNA overexpression. In another study, SNU-16 and HCG-27 cell types, both from human gastric cancers, exhibited low and high PANX1 gene expression respectively. Induced overexpression of PANX1 in SNU-16 cells upregulated AQP5, while suppression of PANX1 in HGC-27 cells downregulated AQP5 [48]. In a final example, BRAF, a downstream effector of EGFR, showed increased V600E mutations in cutaneous melanoma, leading to an overexpression of AQP1s. Groups with increased BRAF V600E mutations were also associated with reduced disease-free survival (DFS) and overall survival [49].

Changes in aquaporin localization

During cell migration, specific proteins localize to regions of the cell to facilitate cell movement. During 2D cell migration, AQPs localize to the leading and lagging edges of the cell to facilitate the volumetric changes necessary for membrane protrusion formation and cell retraction, respectively. The function and regulation of AQP localization becomes more obscure and complex for cancer cell migration in various microenvironments that more accurately replicate in vivo cues. These mechanisms underlying AQP localization in cancer cell migration are not universal across cell types or even cancer stages, making it difficult to fully elucidate the resulting cell behavior.

Within the cell, AQPs are found in the nucleus, cytoplasm, and cell membrane. Though some studies have determined that localization can be mediated by AQPs’ consensus site, there is little known about how AQP movement and distribution is regulated. Here, we will only discuss AQP localization with regard to cell migration, but we refer readers to another review for a broader explanation of AQP localization [50].

Single cells

As expected by their function of transporting water into and out of the cell, AQPs are localized to the cell membrane in most types of cancer. This localization holds true for AQP3 and AQP5 in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma [25]. The dual localization and co-expression of AQP3 and AQP5 on the cell membrane is associated with increased cell invasion, lymph migration, and distant metastasis. From histological samples of patients with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, AQP5 is expressed at the apical membrane of intercalated and intralobular ductal cells, while AQP3 is expressed at the plasma membrane of ductal cells [51]. This expression occurs simultaneously with a decrease in epithelial-like markers and an increase in mesenchymal-like markers, followed by a more infiltrative morphology. This AQP3 and AQP5 localization and the resulting cell invasiveness are correlated with a decreased survival rate. Furthermore, in bronchial epithelium, AQP5 is polarized to the apical membrane. Interestingly, AQP4 can be expressed in two isoforms: M1-AQP4 and M23-AQP4. The M23-AQP4 isoform self-assembles into large well-ordered structures, while M1-AQP4 does not [52]. As studied in glioma cells, M1-AQP4 isoforms are highly mobile in the plasma membrane, helping facilitate the rapid water transport for cell migration. In contrast, the M23-AQP4 orthogonal arrays exhibit much slower diffusion, resulting in more defined cell–cell adhesions and reduced cell migration. Finally, we have previously found that breast cancer cells migrating in confined microchannels polarize AQP5 to the leading edge of the cell membrane [53]. Such polarization facilitates water transport and enables the cells to propel themselves forward in a phenomenon called the “Osmotic Engine Model.”

AQPs are also found in the cytoplasm of cells. In prostate cancer, while AQP3 is primarily expressed at the plasma membrane, AQP9 is mostly expressed in the cytoplasm of cells [54]. The driving force for AQP9 cytoplasmic localization is unexplored, but it could relate to the anti-cancer properties of AQP9 in HCC [55]. This motivates the theory: If AQP9 has such anti-cancer properties in the prostate cancer, could cells be actively preventing its trafficking to the cell membrane, thereby disabling the anti-cancer functions? In contrast, expression of AQP1 in the cytoplasm is correlated with a lower survival rate in patients with esophageal and breast cancer, compared with AQP1 localization to other regions of the cell [56, 57].

In HCC, AQP3 is localized to both the cytoplasm and cell membrane in HepG2s cells [58] and in tissue samples from patients [59], while Chen et al. found AQP3 in the cytoplasm and nucleus of HCC patient tissues samples [60]. This complicates findings, because the localization of AQP3 may be dependent on many factors not yet known. To our knowledge, there is only one study reporting excessive AQP nuclear localization. In that study, GBM U87 cells overexpressing AQP2 and treated with estradiol (E2) exhibited mostly nuclear AQP2 localization and significantly reduced cell invasion compared to mock cells [41]. This strange phenomenon was confirmed as the researchers found similar nuclear localization in five other cell lines from various tissues [41]. It was proposed that E2 regulates AQP2 localization by inhibiting phosphorylation of AQP2 in the membrane, which may prevent its accumulation on the membrane and enhance cell migration [41].

We also emphasize that AQP expression and localization are separate concepts. It is possible (though not yet demonstrated) that AQP localization may change in migrating cells in response to changing conditions or progression to pathological state even though overall AQP expression does not change. For example, multiple previous studies have shown increases in AQP4 membrane localization in primary human astrocytes even in the absence of changes in AQP4 protein expression levels [61, 62]. Though these studies did not address cell migration and were completed using normal, healthy cells, future work could evaluate AQP mislocalization in migrating or invading cells specifically. It is possible that mislocalization of AQPs, or trafficking of AQPs to the cell membrane, could be an even more effective therapeutic target than AQP expression itself [50].

Role of aquaporins in cancer cell invasion and migration

Below we detail different methods and implications derived connecting AQPs and cell migration. As we expand our knowledge of AQPs’ role in cell migration, more physiologically relevant 3D models could be developed and implicated to further understand the complexity of AQPs’ various functions in cell migration. These models could include the use of humanized self-organized models, organoids, and 3D organ-on-a-chip platforms.

Wound healing studies

Wound healing assays are simple and inexpensive, while mimicking some aspects of cell migration during wound healing in vivo. This assay is one of the most widely used to identify the influence of AQPs in cell migration. Table 1 provides a summary of cell types, relevant AQPs, and resulting changes in cell migration that have been identified using wound healing assays. To summarize Table 1, we note that inhibiting or suppressing AQP1, AQP2, AQP3, AQP4, or AQP5 leads to a decrease in the speed of wound closure across a variety of cancers [9, 13, 15, 30, 34, 36–38, 40, 40, 41, 44, 48, 63–80]. Interestingly, AQP 8 and AQP9 appear to be capable of both inducing cell wound healing or inhibiting it based on the cell type. [18, 29, 55, 81, 82]

Table 1.

Changes in cell migration speed in a wound healing assay following treatment to regulate a specific AQP isoform in specific cell lines

| AQP isoform | Cell line | Treatment | Change in migration speed | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AQP1 | 4T1 and B16F10 | AQP1 over expression | Increased | [63] |

| AQP1 | AGS and MKN45 | AQP1-siRNA | Decreased | [13] |

| AQP1 | AGS and MKN45 | AQP1-siRNA | Decreased | [13] |

| AQP1 | HCT-116 | AqB013 | No significant effects across various doses | [64] |

| AQP1 | HT20 | AQP1-sh1 | Decreased | [65] |

| AQP1 | HT20 | AdV-AQP1 overexpression | Increased | [65] |

| AQP1 | HT29 | AqB006 | No significant change | [66] |

| AQP1 | HT29 | AqB007 | Decreased | [66] |

| AQP1 | HT29 | AqB013 | Decreased | [64] |

| AQP1 | HT29 | Bacopaside I | Decreased | [67] |

| AQP1 | HT29 | Bacopaside II | Decreased | [67] |

| AQP1 | HT29 and MDA-MB-231 | 5AMF, 5NFA, 5HMF, M5NF | Decreased | [68] |

| AQP1 | HT29 | AqB0011 | Decreased | [66] |

| AQP1 | LLC and LTEP-A2 | AQP1-siRNA | Decreased | [15] |

| AQP1 | SACC83 | AQP1 overexpression | No significant change | [69] |

| AQP1 | SH-SY5Y | AQP1-siRNA | Decreased | [44] |

| AQP1 | SW480 | M5NF | Decreased | [68] |

| AQP1 | U251 and U87 | No treatment, observed across different tissue samples with increasing AQP1 expression levels | Migration was greater in tissues with increased AQP1 expression | [70] |

| AQP2 | T98G | E2 | Increased | [41] |

| AQP3 | A549 and NCI-H460 | AQP3-siRNA | Decreased only under hypoxic conditions | [71] |

| AQP3 | A549 and NCI-H460 | Hypoxia | Increased | [30] |

| AQP3 | AGS and SGC7901 | AQP3-siRNA | Decreased | [30] |

| AQP3 | AGS and SGC7901 | hEGF | Increased | [30] |

| AQP3 | AGS and SGC7901 | U0126 | Decreased | [30] |

| AQP3 | AGS and SGC7901 | AQP3-siRNA | Decreased | [35] |

| AQP3 | AGS and SGC7901 | HGF | Increased | [35] |

| AQP3 | AGS and SGC7901 | c-Met siRNA | Decreased | [35] |

| AQP3 | Bcap-37 and MDA-MB-231 | FGF-2 | Increased | [36] |

| AQP3 | Bcap-37 and MDA-MB-231 | AQP3 shRNA | Decreased | [36] |

| AQP3 | HPMC | AQP3-siRNA | Decreased | [37] |

| AQP3 | HPMC | TGF-β1 | Increased | [37] |

| AQP3 | MCF7 | E2 | Increased | [40] |

| AQP3 | MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 | hHGF | Increased | [34] |

| AQP3 | MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 | c-Met siRNA | Decreased | [34] |

| AQP3 | MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 | AQP3-siRNA | Decreased | [34] |

| AQP3 | MDA-MB-231 | AQP3 shRNA | Decreased | [72] |

| AQP3 | MGC803 and SGC7901 | AQP3-siRNA | Decreased | [73] |

| AQP3 | MGC803 and SGC7901 | AQP3 over expression | Increased | [73] |

| AQP3 | MNT-1 | Polyoxotungstates | Decreased | [74] |

| AQP3 | T47D | AQP3-siRNA | Decreased | [40] |

| AQP3 | T47D | AQP3-siRNA + E2 | Decreased | [40] |

| AQP3 | T47D | E2 | Increased | [40] |

| AQP3 | T47D | AQP3 over expression vector | Increased | [40] |

| AQP4 | CHO and FRT | AQP1 overexpressing plasmid | Increased | [9] |

| AQP4 | GL-261 and U87 MG | Bradykinin | Increased | [38] |

| AQP4 | LN229 | AQP4-siRNA | Decreased | [75] |

| AQP4 | Mouse-derived AQP4 -/- astroglia | AQP4-/- | Decreased | [76] |

| AQP5 | H1299 | AQP5-siRNA | Decreased | [77] |

| AQP5 | HCT-116 and SW480 | AQP5-siRNA | Decreased | [78] |

| AQP5 | HCT-116 and SW480 | AQP5 over expression | Increased | [78] |

| AQP5 | HCT-116 and SW480 | Cairicoside E | Decreased | [78] |

| AQP5 | HGC-27 | AQP5-siRNA | Decreased | [48] |

| AQP5 | LETP-A2 | AQP5-siRNA | Decreased | [79] |

| AQP5 | LN229, U251, and U87-MG | AQP5-siRNA | Decreased | [80] |

| AQP5 | LN229, U251, and U87-MG | FlagAQP5 (overexpression) | Decreased | [80] |

| AQP5 | PANX1-overexpressing SNU-16 | AQP5-siRNA | Decreased | [48] |

| AQP5 | PC-9 and SPC-A1 | AQP5 over expression | Increased | [79] |

| AQP8 | Eca-109 | EGF | Increased | [29] |

| AQP8 | Eca-109 | PD153035 | Decreased | [29] |

| AQP8 | Eca-109 | U0126 | Decreased | [29] |

| AQP8 | HT-29 and SW480 | AQP8 Overexpression | Decreased | [81] |

| AQP9 | Overexpressing LO2 and SMMC-7721 | AQP9-siRNA | Increased | [55] |

| AQP9 | PC-3 | AQP9-siRNA | Decreased | [18] |

| AQP9 | SHG44 | AQP9-overexpressing pcDNA | Increased | [82] |

| AQP9 | SMMC-7721 | AQP9 overexpression | Decreased | [55] |

| AQP9 | U251 | AQP9-siRNA | Decreased | [82] |

Though the wound healing assay was the first used to prove that AQPs play a role in cellular migration [9], there are very few places in vivo where cancer cells would ever experience the context of a wound healing assay. Since there are limitations to the wound healing assay in terms of its physiological relevance, researchers have turned to more complex cell migration assays and engineered environments.

Cell invasion in Transwell/Boyden chamber

A more complex, yet still simple and relatively inexpensive, method to understand the migration and invasive capacity of cells toward a chemo-attractant gradient is a Transwell or Boyden chamber invasion assay. Similar to the wound healing assay, cells in experiments have been treated to inhibit or suppress expression of AQP1, AQP3, AQP4, AQP5, AQP8, or AQP9 [13, 15, 21, 37, 40, 44, 57, 68, 70–73, 75, 77, 78, 82–97] (Table 2). In general, cells with decreased AQP expression tend to have lower invasion capabilities.

Table 2.

Changes in Transwell invasion capability following treatment to regulate a specific AQP isoform in specific cell lines

| AQP isoform | Cell line | Treatment | Change in migration speed | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AQP1 | AGS and MKN45 | AQP1-siRNA | Decreased | [13] |

| AQP1 | C6 | Dexamethasone | Increased | [83] |

| AQP1 | HT29 | 5AMF | None | [68] |

| AQP1 | HT29 | 5HMF | Decreased | [68] |

| AQP1 | HT29 | 5NFA | Decreased | [68] |

| AQP1 | HT29, MDA-MB-231, and SW480 | M5NF | Decreased | [68] |

| AQP1 | Kelly, SH-SY5Y, SH-EP Tet-21/N, and SK-N-B(2)-M17 | Observed expression of AQP1, HIF-1α, and HIF-2α | Cells that migrated through the Transwell showed increased expression of the observed proteins | [44] |

| AQP1 | LLC and LTEP-A2 | AQP1-siRNA | Decreased | [15] |

| AQP1 | MCF7 and MDA-MB-231 | AQP1 over expression | Increased | [57] |

| AQP1 | MDA-MB-231 and MCF7 | AQP1 over expression | Increased | [57] |

| AQP1 | MDA-MB-231 | 5AMF | None | [68] |

| AQP1 | MDA-MB-231 | 5HMF | Decreased | [68] |

| AQP1 | MDA-MB-231 | 5NFA | None | [68] |

| AQP1 | MG63 and U2OS | AQP1-siRNA | Decreased | [84] |

| AQP1 | SW480 | 5AMF | None | [68] |

| AQP1 | SW480 | 5HMF | None | [68] |

| AQP1 | SW480 | 5NFA | None | [68] |

| AQP1 | U251 and U87 | Cell clones with varying degrees of AQP expression | Cells with Increased AQP1 expression demonstrated elevated invasion | [70] |

| AQP3 | A549 and NCI-H460 | Hypoxia | Increased | [71] |

| AQP3 | A549 and NCI-H460 | AQP3-siRNA | Decreased but only under hypoxic conditions, had no effect at normoxic levels | [71] |

| AQP3 | DI-145 and PC-3 | AQP3-siRNA | Decreased | [85] |

| AQP3 | DU4475 and MDA-MB-231 | CXCL12 + AQP3-siRNA | Increased migration after culturing with CXCL12, however after AQP3 knockdown, migration reverts to non-CXCL12 migration speed | [86] |

| AQP3 | HepG2 | AQP3-siRNA + TCDD | Decreased | [87] |

| AQP3 | Hep3B and Huh-7 | miR-345-5p | Increased | [88] |

| AQP3 | Huh7 and MHCC-LM3 | AQP3-siRNA | Decreased | [98] |

| AQP3 | Huh7 and MHCC-LM3 | AQP3 over expression | Increased | [98] |

| AQP3 | HPMC | AQP3-siRNA | Decreased | [37] |

| AQP3 | HPMC | TGF-β1 | Increased | [37] |

| AQP3 | MDA-MB-231 | AQP3-shRNA | Decreased | [72] |

| AQP3 | MGC803 and SGC7901 | AQP3-siRNA | Decreased | [73] |

| AQP3 | MGC803 and SGC7901 | EGF + AQP3-siRNA | Increased | [73] |

| AQP3 | T47D | AQP3 over expression | Increased | [73] |

| AQP3 | T47D | AQP3-siRNA | Decreased | [40] |

| AQP3 | T47D | AQP3-siRNA + E2 | Decreased | [40] |

| AQP3 | XWLC-05 | AQP3-siRNA | Decreased | [90] |

| AQP4 | A172 and U251 | si-LINC00461 + AQP4 | Decreased migration following si-LINC00461 treatment. Migration recovered after AQP4 overexpression | [91] |

| AQP4 | D54-MG | Chelerythrine | Increased | [92] |

| AQP4 | D54-MG | PMA | Decreased | [92] |

| AQP4 | D54-MG | U0126 | No significant change | [92] |

| AQP4 | D54-MG | U73122 | Decreased | [92] |

| AQP4 | LN229 | AQP4-siRNA | Decreased | [75] |

| AQP5 | H1299 | AQP5-siRNA | Decreased | [77] |

| AQP5 | HCT-116 and SW480 | Cairicoside E | Decreased | [78] |

| AQP5 | Hep-3B | AQP5-siRNA and Helenalin | Decreased | [93] |

| AQP5 | MCF7 | Sorbitol | Decreased | [21] |

| AQP5 | PC-3 | AQP5-siRNA | Decreased | [94] |

| AQP5 | PC-9 and SPC-A1 | AQP1 over expression | Increased | [95] |

| AQP8 | SiHa | AQP8 over expression | Increased | [96] |

| AQP8 | SiHa | AQP8-shRNA | Decreased | [96] |

| AQP9 | Huh-7 and SMMC-7721 | AQP9 over expression lenti virus | Decreased | [97] |

| AQP9 | U251 | AQP9-siRNA | Decreased | [82] |

Cell migration in microchannels

Cancer cells experience the physical cue of confinement while migrating in vivo through pre-existing pores or channels ranging from 10 to 300 µm [2]. Intriguingly, cancer cells are capable of modulating their migration mechanism to continue moving forward when confronted with these cues. Using an in vitro microchannel device that replicated the cue of confinement, it was discovered that even after the inhibition of cell’s actin polymerization, Rho/ROCK signaling, myosin contractility, or β1 integrins, some cancer cell types are still able to migrate [99] through confining microchannels.

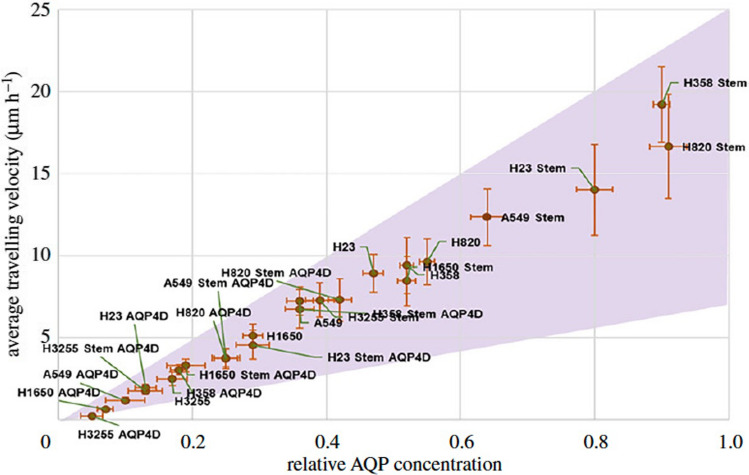

This prompted us to investigate the hypothesis that AQPs in tandem with ion channels could provide water fluxes needed to propel cells forward [53]. In previous work, we discovered that MDA-MB-231 cancer cells polarize AQP5 and NHE1 to the leading edge of the cell, that their migration can be directed through osmotic shocks at the leading or lagging edge of the cell, and that knocking down AQP5 reduces cell migration speed in confined microchannels. These experimental observations aligned with our model’s theoretical predictions based on a mechanism of migration where a net inflow of water at the leading edge and a net outflow of water at the lagging edge lead to a net cell displacement. We named this mode of cell migration the “Osmotic Engine Model” [53]. This mechanism of cell migration was later supported when Hui et al. related the AQP4 expression across more than 20 cell lines to the increased migration in confined microchannels [100] (Fig. 2). Knockdown of AQP4 reduced the migration speed of these cells migrating in the confining microchannels. Additionally, the cells move faster when the channels are not coated with an adhesive protein, suggesting that the Osmotic Engine Model is a more efficient mechanism of cell movement through confined spaces. Finally, in confining microchannels, it was found that AQP4 localizes with SWELL1 at the trailing edge of breast cancer cells [101]. This localization, in concert with NHE1, provides the local volume efflux needed to propel the cell forward. This localization of SWELL1 is indicative of the directionality of cell migration [101].

Fig. 2.

Average cell velocity vs. relative AQP4 expression in a range of cell types: Representation of the relationship between cancer cell migration velocity in confined microchannels and their AQP4 expression across more than 20 different cancer cell lines (reproduced with permission from Ref. [100])

Cell–matrix adhesion

Cell adhesion is a crucial aspect of many migratory phenotypes, especially as cells are migrating away from the tumor and into the surrounding matrix. The specific adhesion-related proteins AQPs influence is described in full below in the Changes in Aquaporin Signaling Pathways section. Yet, some studies used simpler assays, such as counting the number of floating cells in a culture after given time periods, to investigate cell adhesion without observing the adhesive proteins involved. For instance, the modulation of AQP1 expression in osteosarcoma cells directly relates to cell adhesion [102]. Similarly, AQP5 suppression can lead to strongly inhibited cell adhesion in squamous cell carcinoma, but not standard fibroblasts [103].

A more rigorous study of adhesion in mesothelioma found AQP1 expression enhances cell adhesion to laminin-1, collagen-1, and fibronectin (FN) in M14K cells, but not Zl34 cells. MeT-5A cells were AQP1 adhesion dependent only on FN [104]. The migration speed of sarcoma cells, which have a higher expression of AQP1, is significantly faster than that of the respective nonmalignant cells. AQP1 inhibition in the sarcoma cells significantly reduced their speed.

Cell invasion in 3D gels

Gel invasion assays are used to identify the invasive capabilities of cells into the surrounding extracellular matrix (ECM). NSCLC cells with strong AQP5 expression demonstrate the highest degree of cell invasion into Matrigel, while the invasion of cells with AQP5 N185D and S156A mutants are markedly slower [23]. Furthermore, in basement membrane extract, the knockdown of AQP3 reduces breast cancer invasion [72]. We suggest that more studies should be conducted with different material parameters, such as substrate stiffness, porosity, and ligand presentation, and explore their effects on AQP-mediated migration. These studies could not only elucidate how cells use AQPs to invade into surrounding tissue, but also could delineate how microenvironment properties impact the role of AQPs in invasion.

Invasion/migration in vivo

Mouse models are powerful tools to help understand how tumor cells invade the surrounding tissue and migrate to other regions in the body. Here, we will narrow the focus only to results related to cell migration. A crucial step of tumor growth is invasion into the surrounding tissue. AQP3 knocked down in XWLC-05 human lung cancer cells injected into nude mice does not alter the rate of subcutaneous tumor formation, but there is overall less tumor growth when compared to injection of wild type cells [90]. Interestingly, a similar decrease in growth is observed in HCC tumors xenografted into nude mice, but in this case the decrease in growth is caused by overexpression of AQP9 [14].

We note that it is difficult to isolate the cues prompting the migration of single cells within mice, which is why in vitro models are quite informative. However, one approach to understand AQP-mediated changes in cell migration is to assess a process in which migration plays a key role: metastasis. In mice transfected with AQP1-overexpressing 4T1 cells, which traditionally do not express any AQP1, cell extravasation was observed in only 6 h after injection, which was significantly faster than injection with control, non-AQP1-expressing cells [105]. Two weeks after the injection, mice with AQP1-expressing cells showed more lung metastasis with greater alveolar wall infiltration when compared to the mice with non-AQP1-expressing cells. Conversely, Zhang et al. found that HCC tumors implanted into mice with higher levels of AQP9 have a reduced metastasis rate [55]. Another study found reduction of lung metastasis from CRC tumors upon overexpression of AQP8, and this overexpression also resulted in a reduction of tumor growth [81]. Overall, there is mounting evidence pointing to the role of multiple isoforms of AQPs being involved in tumor cell migration, even leading to alterations in disease phenotypes in vivo.

Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition

Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) is a highly dynamic process where epithelial cells shift toward a mesenchymal phenotype. Cancer cells can make this transition, leading to an increase in the aggressiveness of cells and resistance toward cancer treatments [106]. This change from epithelial-like cells to mesenchymal-like cells is regulated by a group of transcription factors, including SNAIL, SLUG, and/or TWIST1 [40, 48, 97], which may be regulated by AQPs (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Currently known pathways by which AQPs are capable of inducing tumor cell EMT. Other pathways have been implicated in the progression of cancer, but this figure focuses specifically on EMT-related signaling

Activation of the ERK signaling cascade is often one of the first steps in EMT, and in CRC, activation of this pathway is mediated by AQP5 [20]. EMT is also regulated by AQP5-mediated smad2/3 signaling, leading to an increase in SNAIL expression [78]. In gastric cancer, AQP3 overexpression increases AKT phosphorylation, leading to the activation of SNAIL [73]. Furthermore, in HCC AQP5 regulates the activation of NF-kB, a transcription factor involved in activation of TWIST1 [93]. Additionally, AQP5’s phosphorylating D-loop induces EMT through direct activation of c-Src, Lyn, and Grap2 c-terminal [23]. Interestingly, the overexpression of AQP9 inhibits the activation of AKT, thus suppressing cell invasiveness by reducing cell EMT [55]. However, in HCC the expression of AQP9 is reduced, and thus AQP9’s anti-EMT effects are negligible [55].

EMT-induced changes in cell protein expression

The switch from epithelial cell phenotype to a mesenchymal phenotype is marked by changes in cell morphology and protein expression. When cells are in the epithelial stage, they display cell-to-cell adhesions marked by the presence of E-cadherin. As they transition to a mesenchymal-like phenotype, cells upregulate proteins such as N-cadherin, vimentin, and FN. As we discuss further below, AQP expression has been clearly shown to regulate this change from an epithelial phenotype to a mesenchymal phenotype. For instance, AQP8 overexpression leads to upregulated vimentin and N-cadherin with a downregulation in E-cadherin [96]. Expression of E-cadherin is downregulated upon AQP3 overexpression in gastric cancer [73], with a concomitant increase in vimentin and FN. The pI3K/AKT/SNAIL signaling pathway is likely involved in this induction of the gastric cancer’s AQP3-mediated EMT. Meanwhile, AQP4 suppression enhances E-cadherin expression by reducing the activation of the ERK pathway in breast cancer [107]. Though the study did not specifically focus on EMT, it demonstrated that GBM cells expressing AQP4 have decreased cell–cell adhesion, a more dynamic actin organization, and increased invasive and migratory capacity when compared to AQP4-silenced cells [75]. It was postulated that these changes are a result of AQP4’s regulation of β-catenin and connexin 43 expression. He et al. later found that a downregulation of AQP5 in HCC causes EMT suppression marked by the decrease in EMT proteins N-cadherin and vimentin, and an increase in the epithelial proteins E-cadherin and α-cadherin. This downregulation of AQP5 leads to a clear reduction in p-NF-kB in HCC cells, potentially indicating a signaling pathway AQP5 utilizes to mediate cell EMT [93]. Interestingly, AQP9 overexpression decreases EMT in HCC, likely mediated by the decreased levels of p-AKT [55]. In a separate study, AQP9 expression reduces growth and metastasis of HCC through the inhibition of PCNA, N-cadherin, α-smooth muscle actin, DVL2, GSK-3B, cyclinD1 and, importantly, β-catenin. The downregulation of β-catenin likely inhibits cell growth through reduced expression of TWIST1 [97]. Additionally, AQP1 co-immunoprecipitation with Lin7 was shown to regulate β-catenin expression in melanoma cells. Upon knockdown, there was a significant decrease in cell migration [108].

The expression of AQPs and their interactions with other proteins results in these EMT-like changes as well. For instance, estrogen can induce AQP5-mediated EMT in prostate epithelial cells, marked by an increase in vimentin and a decrease in E-cadherin [109]. Estrogen can directly upregulate AQP3 by activating the estrogen response element (ERE) promoter of the AQP3 gene, which leads to upregulation of N-cadherin, vimentin, and FN, likely mediated by the increase in SNAIL 1 and 2 [40]. AQP5 activation via PANX1 is involved in gastric cancer cell EMT, as shown by the increase in vimentin and SLUG expression with a decrease in E-cadherin expression [48]. AQP5 activation of EMT in NSCLCs results in a loss of the epithelial markers E-cadherin, α-cadherin, and γ-cadherin and gain of the mesenchymal markers FN and vimentin [23]. In pancreatic ductal cells, there is simultaneous overexpression of AQP3, EGFR, Ki-67, and CK7, along with a decrease in E-cadherin and increase in vimentin [51].

EMT-induced changes in cell protease production

During mesenchymal-like cell migration, cells secrete proteases to degrade the ECM to facilitate invasion into the surrounding tissue [110]. In SGC7901 cells, there is a decrease in MMP2 and MMP9 after AQP3 suppression, while secretion of these proteins is significantly increased after AQP3 overexpression [111]. AQP1 also plays a role in the regulation of MMP expression. For example, in lung cancer cells LLC and LTEP-A2, MMP2 and MMP9 have a dose-dependent relationship with AQP1 suppression via siRNA. However, this decrease in MMP expression is not dependent on TGF- or EGFR, the traditionally perceived regulators of MMP expression [15]. Meanwhile, MMP expression is also reduced in melanoma cells with an AQP1 knockdown [16]. In GBM, migration and invasion are dependent on AQP1- and AQP4- mediated MMP2 and MMP9 secretion [70, 75, 112]. In the same study as above, Oishi et al. also found that AQP1-mediated Cathepsin B expression is involved in GBM migration and invasion [70].

EMT-induced changes in cell morphology and behavior

The resulting AQP-mediated activation of EMT leads to changes in cell migratory phenotypes. In cervical cancer, there is a strong correlation between AQP8 expression and prognosis. Overexpression of AQP8 in SiHa cells enhances cell viability, invasiveness, and migratory abilities, while reducing apoptotic rate [96]. In breast cancer cells, ER-mediated overexpression of AQP3 increases cell migration and invasion. AQP3 upregulation leads to reorganization of the cytoskeleton and formation of filopodia, likely contributing to migration [40]. Furthermore, in human bronchial epithelial cells, induced AQP5 overexpression leads to activation of EMT-mediated signals. These AQP5-overexpressing cells show decreased cell adhesion and transition toward a more spindle-like fibroblastic morphology [23]. Finally, after an AQP2 knockdown in endometrial adenocarcinoma there is a reduction in cell migration, invasion, and adhesion [113]. The knockdown also leads to a change in cell morphology by decreasing annexin-2 and F-actin levels, resulting in smaller, displaced lamellipodia [113].

Changes in aquaporin-mediated signaling pathways

Aside from facilitating cell water transport and mediating EMT in cancer cells, AQPs are key regulators in many cellular signaling pathways that are crucial to the migration and subsequent metastasis of cancer cells. This section is organized according to the major signaling pathways regulated by AQPs.

Focal adhesion regulators

In GBM, AQP1 knockdown leads to a decrease in αvβ3 integrins, as well as resulting reduced migration and invasion in vitro [112]. AQP5 plays a role in α5 and β1 integrin expression in squamous cell carcinoma of the tongue. Suppression of AQP5 leads to a decrease in cell adhesion and growth, yet this relationship is not found in standard fibroblasts [103]. This suggests that AQPs’ role in adhesion could be initiated following cancer progression [103]. AQP3 also regulates integrin α5 and β1 in squamous skin cancer, where suppression of AQP3 is associated with a decrease in FAK [114]. This decrease in FAK interferes with the MAPK pathway and directly increases cell death. These results are somewhat surprising, as they differ from behaviors that are found in healthy cells. This is further discussed in Part 1 of this review, where we discussed that increased AQP expression can induce increased integrin and focal adhesion turnover in actively migrating cells, such that migrating healthy cells do not get “stuck” by an excessive number of integrin-based adhesions. Furthermore, in GBM, AQP1 dose-dependently accelerates cell migration and invasion through upregulation of FAK and Cathepsin B; this change is likely mediated by AQP1’s activation of Src [70].

PI3K/AKT

In some types of cancer, certain AQP isoforms have been implicated in the decrease of PI3K signaling. In CRC, overexpression of AQP8 decreases growth, aggressiveness, and colony formation in CRC SW480 and HT-29 cells [81]. It is likely that this occurs through the inhibited activation of PI3K/AKT signaling. In HCC, cells overexpressing AQP9 show reduced levels of PI3K, leading to a reduced phosphorylation of AKT [14]. This reduction increases the functional FOXO1 levels in the nucleus.

Conversely, the role that AQPs play in PI3K changes based on cancer type. In astrocytoma, the same AQP9 isoform is an essential part of cell migration and invasion, in part through its activation of AKT [82]. In adenocarcinoma human alveolar basal epithelial cells, AQP3 knockdown reduces AKT phosphorylation, suppresses MMP2 and MMP9, and decreases cell invasiveness [17]. In SGC 7901 cells, AQP3 silencing significantly decreases the phosphorylation of ser473 of AKT, thus reducing cell invasion capabilities [111]. As anticipated, AQP regulation of PI3K is also extended to the protein’s downstream effectors. Mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) is a protein that acts both upstream and downstream of AKT to regulate the protein synthesis necessary for cell growth, proliferation, and angiogenesis [115]. Via proteomics, AQP3 expression has been found to be associated with an increase in mTOR_S2448 activity among other changes in protein expression (caspase-9↓, cyclin E1↓, EPPK1↓, HER3_pY1289↓, IRF-1↓ and Src↓ activity, Rad50↑, and S6pS235S_236↑) [115]. Further investigation led to the finding that miRNA-874, an AQP3 inhibitor, drastically decreases the activity of mTOR signaling [115].

ERK/MAPK/p38

While the mechanisms by which AQPs impact Ras activation remain unclear and could vary between cell types, it is well established that some AQPs alter the expression of Ras and subsequently the ERK1/2 signaling pathway. As ERK signaling has critical downstream effects in cancer progression, multiple studies have investigated how AQPs directly mediate ERK activation. In gastric cancer, AQP1 enhances GRB7-mediated Ras/ERK activation [13]. Suppression of AQP1 is associated with a reduction in activated Ras, and thus ERK, leading to a decrease in cell proliferation, migration, and invasion [13]. As mentioned above, AQPs are regulators of FAK, which can act as an upstream regulator of GRB7. Though the direct relationship between the two has not been investigated, AQP3 suppression decreases FAK, which thereby decreases ERK and MAPK in esophageal and lingual cancers [114]. Kang et al. discovered that AQP5-mediated activation of the ERK1/2 pathway is dependent on its SH3 consensus site in loop D of AQP5 in HCT116 cells, and overexpression of AQP5 leads to an increase in ERK1/2 activation that increases cell growth [20]. Unexpectedly, the same study showed that AQP1 and AQP3 have no effect on the activation of ERK. Meanwhile, Jensen et al. found that there is no correlation between AQP5 expression and Ras or Rac1in patient-derived breast cancer samples [116]. These conflicting results demonstrate that there are differences in the roles AQPs play based on isoform, cell type, or even whether the study was conducted in vivo or in vitro.

Though other studies have not investigated the direct mechanism by which AQPs alter ERK signaling, there are still correlations between the two. For example, Zhang et al. found that AQP5 overexpression increases activation of the EFGR/ERK/p38/MAPK pathway, and deletion of AQP5 reverses this effect [95]. The group also found that the activation of EGFR/ERK/p38/MAPK is not dependent on AQP1 or AQP3 in lung cancer. Unlike the work by Kang et al., this paper did not investigate the direct contribution of AQP5 in ERK signaling [20, 95]. However, they did find that AQP5-mediated ERK activation leads to increased local invasiveness, mucin production, proliferation, and in vivo migration and metastasis [79, 95]. Another study focusing on human glioma cancer cells (U87-MG, U251, and LN229) found that suppression of AQP5 decreases expression of ERK/MAPK/P38 and subsequently reduces cell migration [80]. In prostate cancer cells (PC-3 and DU145), AQP3 promotes the activation of ERK1/2, thereby increasing MMP3 expression [73]. In ECA-109 cells, AQP8 mediates cell migration through regulation of the EGFR/ERK1/2 pathway. Activation of EGFR increased AQP8 expression, potentially leading to another positive feedback loop [29]. Finally, hyperglycemic conditions, which correlate with tumor size, lead to upregulation of AQP3 and cell migration in GC cells in a dose and time-dependent manner and through the ERK and PI3K pathways, with a reversal of this behavior upon AQP3 knockdown [117].

Stem cell markers

Cancer stem cells are a small subpopulation of cancer cells capable of self-renewal, differentiation, and tumorigenicity [118]. Intriguingly, initial evidence indicates that AQPs could be implicated in the development of cancer stem cells. When in the cytoplasm, AQP3 activates signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) by promoting its phosphorylation and resulting in its translocation to the nucleus. STAT3 binds to the promoter of CD133, resulting in its increased transcription. CD133 is considered a liver cancer stem cell marker [119]. Overexpression of AQP3 induces expression of another cancer stem cell marker, CD44, and activation of β-catenin pathway in SGC7901, MGC803, and AGS cells, leading to cancer stem cell behaviors [120]. The suppression of AQP4 decreases the cancer stem cell markers SOX1 and Oct4 [100].

Hypoxia

Cells experiencing hypoxic conditions and oxidative stress (e.g., at the center of a large tumor) upregulate HIFs. As mentioned above, these HIFs can induce AQP expression to help relieve the oxidative strain on the cells. In NSCLC cells (A549 and NIC-H460), AQP3 suppression under hypoxic conditions reduces the proliferation, migration, and invasion of these cells [121]. Further analysis showed that this reduction of proliferation and migration occurs in concert with a reduction in HIF-alpha, VEGF, Raf, pMEK and pERK. A similar study found that AQP3 suppression inhibits lung tumor angiogenesis and also reduces the expression of VEGF and HIF-2alpha [17].

H2O2

AQPs can facilitate the transport of small molecules like H2O2. The NADPH oxidase 2 -produced H2O2 is transported into the cell by AQP3. H2O2 subsequently induces the activation of the AKT pathway to contribute to directional migration. The expression level of AQP3 is confirmed to influence breast cancer cell’s migratory ability in vivo and in vitro [86]. Furthermore, AQP5 can facilitate transmembrane H2O2 diffusion [122]. AQP5 permeability to H2O2 is mediated by the His173 residue and its interactions with Ser183; therefore blocking of AQP5 in pancreatic cancer suppresses cell migration [122].

Tumor-related vascular angiogenesis

In terms of AQPs, most of the efforts to better understand tumor angiogenesis have stemmed from work in AQP-deficient mouse models [123]. In AQP1-deficient mice, tumor growth is reduced by increased necrosis because of decreased blood vessel formation [124]. Cultured aortic endothelial cells from AQP1-/- mice migrate slower toward a chemotactic stimulus compared with AQP1 wildtype cells. In other mice models, tumors injected with AQP1 siRNA exhibit a 75% reduction in tumor volume and a 40% reduction in the endothelial marker Factor VIII 6 days post-treatment [125]. Vasculogenic mimicry (non-endothelial tumor cell-lined microvasculature in aggressive malignant tumors) dramatically decreases following AQP1 shRNA-suppression in vivo [112]. In another study, the decreased blood vessel formation is associated with a reduction in number of microvessels and abnormal vascular patterns with smaller and shorter vessels [126]. This abnormal microvessel formation leads to a reduction in the number of murine lung metastases. Injection of AQP3 siRNA into lung tumors also inhibits tumor angiogenesis, in concert with a reduction in HIF2α and VEGF expression [17].

Another method for investigating the role of AQPs in tumor angiogenesis is immunohistochemical (IHC) staining of patient-derived tumor samples. From HCC samples, IHC analysis showed that AQP1 is highly expressed on the membranes of microvessels and small vessels but rarely in the HCC cells [127]. AQP1 expression is related to tumor size, microvascular invasion, and tumor metastasis, indicating the important role that AQP1 plays in tumor progression. Furthermore, from IHC analysis, adipocyte enhancer binding protein 1 (AEBP1) is upregulated in colorectal cancer endothelial cells, leading to increased migration and subsequent angiogenesis. It is proposed that this change in angiogenesis is a result of increased AQP1 expression, likely mediated by AEBP1’s activation of NF-κB [128].

In vitro angiogenesis is investigated through tube formation assays, which measures the ability of endothelial cells to form capillary-like structures that resemble “tubes”. This assay has been utilized to demonstrate that the upregulation of AQP1 in GBM cells increases tube formations. AQP1-expressing GBM can increase wall thickness of vascular endothelial cells ECV304 in a contact-dependent manner [70]. Interestingly, when conditioned media (CM) from H1299 AQP5 downregulated cells is added to HUVECs, tube formation potential is decreased when compared to HUVECs treated with CM from control cells [129]. Furthermore, VEGF is significantly increased in control CM-treated HUVECs compared with AQP5 knockdown CM-treated HUVECs, likely caused by the decreased phosphorylation of the ERK1/2 pathway [129].

Association of AQPs with cancer prognosis

AQP expression, localization, and isoform have been associated with patient prognosis across different cancer types. This review will address the role AQPs play in metastasis-related prognosis; however, other reviews have thoroughly detailed the role that AQPs play in patient survival and disease progression [10, 19].

Lymph node metastasis is a common prognosis marker used to elucidate the role AQPs play in the progression of cancer. AQP1, AQP3, and AQP5 expression in colon cancer are significantly correlated with lymph node metastasis [130]. AQP1 expression in CRC increases cell invasion and lymph node metastasis [131, 132]. AQP5 expression in ovarian cancer is correlated with lymph node metastasis [133]. Overexpression of AQP5 in patient tissue samples correlates with increased lymph node metastasis from human gastric carcinoma cells and prostate cancer cells [94, 134]. Furthermore, the percentage of AQP5 expression is higher in tissue with lymph metastasis than without, although there is no significant difference in AQP5 expression between the primary and metastatic NSCLC [22]. Finally, in adenocarcinoma samples there is a significant correlation between increased disease-free survival and lower AQP5 expression.

However, the relationship between AQP expression and cancer progression is not universal. For example, in a study on squamous cell carcinoma, there was no relationship between AQP5 overexpression and overall survival of patients in squamous cell carcinoma [135]. After reviewing 12,427 prostate cancer tissues, it was found that high and low expression of AQP5 can lead to unfavorable disease outcome and lymph node metastasis in TMPRSS2-ERG fusion and/or PTEN deletion (Fig. 4) [136]. Again in breast cancer, high mRNA expression levels of AQP0, AQP1, AQP2, AQP4, AQP6, AQP8, AQP10 and AQP11 were significantly associated with better relapse-free survival, while AQP3 and AQP9 were associated with worse RFS [137]. In bladder cancer, the loss of AQP3 expression is associated with a significantly worse progression-free survival [138]. Furthermore, AQP1 overexpression from patients with adenocarcinoma has a shorter disease-free survival compared to patients without an AQP1 overexpression [139]. High expression of AQP3 has also been associated with significantly improved progression-free survival, and a decrease in lymph node metastasis in bladder cancer [140]. However, in this last work, the authors noted that their study was small and not appropriately powered, and hence we approach their results with caution. Overall, further work should be conducted to better elucidate the relationship between AQP expression and cancer prognosis, but the body of work reviewed here does provide evidence toward the claim that AQPs do not have a universal role in cancer progression [136].

Fig. 4.

AQPs and their prognostic value. AQP5 expression (the shading) in relation to ERG (prostate cancer prognostic marker) from over 12,000 patient samples (reproduced with permission from Ref. [136])

Co-expression prognosis

In the human body, it is quite rare for a single protein to dictate the entire behavior of a cell. Other studies have investigated co-expression of different AQP isoforms together, as well as AQPs with other proteins, to better understand the overall contributions to metastasis. The combination of AQP3 and AQP5 has been extensively investigated in tandem. Overexpression of AQP3 and AQP5 in triple negative breast cancer is significantly associated with tumor size, lymph status, and local relapse. Overexpression occurs more frequently in tissues with higher Ki-67 expression than those with lower Ki-67 expression [141]. The authors of this study found that AQP3 and AQP5 must be expressed together, as expression of only one showed no significant impact on cancer outcome. Again, this was observed in HCC where the combination of both AQP3 and AQP5 is a strong predictor of poor survival in patients [59]. Interestingly, Direito et al. found that in pancreatic cancer, AQP3 is overexpressed in late and more aggressive stages, while AQP5 is related to tumor differentiation [51].

Aside from expression with other AQPs, a few studies have observed relationships between AQPs and other proteins that can influence patient outcome. For example, expression of AQP3 and CD44 in GC cells is correlated with lymph node metastasis and lymphovascular invasion [120]. Furthermore, high AQP1 expression and intertumoral microvessel density are significant risk factors for mortality; these two proteins could eventually serve as indicators for 5 year DFS [127].

Overall, AQP-mediated dysregulation of cell migration is most well studied in the context of cancer. However, AQPs have also been reported to be involved in cell migration related to other diseases and conditions, including endometriosis, arthritis, and cardiac disease. Furthermore, there are a handful of other studies involving AQPs in cell migration in the context of lung edema, tendon dysfunction, and liver cirrhosis. The next few sections focus on these topics.

Endometriosis

Endometriosis is a disease characterized by the abnormal growth of the endometrium, the inner uterine lining, outside of the uterus. Endometriotic cells (EmCs) are capable of invading surrounding organs and spreading to the abdominal cavity, causing tissue scarring and inflammation. Although several AQP isoforms are normally expressed in healthy human female endometrium [142–144], in the disease state, EmCs overexpress AQP1, AQP2, AQP5, and AQP8 [40, 113, 142, 143, 145]. One explanation for this upregulation could be that AQP expression is sensitive to the high levels of E2 found in endometriosis due to the ERE identified in the promoter region of the AQP1, AQP2, AQP3, AQP5, and AQP7 genes [40, 113, 142, 146, 147].

Recent literature indicates links between aberrant AQP expression and increased EmC migration and invasion in endometriosis. In one of the first studies to investigate the role of AQPs in endometriosis, Jiang et al. found that an AQP5 knockdown yielded a significant reduction in E2-induced proliferation and invasion of primary EmCs in a Boyden chamber. In their mouse model, EmC ectopic nodule formation was also significantly attenuated after an AQP5 knockdown [142]. Similarly, a more recent investigation by Shu et al. discovered that silencing AQP1 in EmCs has inhibitory effects on endometriosis progression in mice by activation of the Wnt signaling pathway [145]. Compared to the scramble group, silencing AQP1 led to an increased expression of Wnt factors (Wnt1 and Wnt4), invasion inhibitors (TIMP-1 and TIMP-2), and apoptotic factors (Caspase-3, Caspase-9, Bax, and BcL-2) in ectopic EmCs in mice with endometriosis. Conversely, the EmC AQP1 silencing caused a decreased expression of invasion factors (MMP2 and MMP9), angiogenic factors (VEGF-A, VEGFR1, and VEGFR2), and adhesion molecules (VCAM-1 and ICAM-1) [145]. These results demonstrate that AQP1 expression correlates with the capacity of EmCs to adhere, invade ectopic sites, and survive in endometriosis, although an analysis of live cell behaviors rather than only gene and protein expression would have strengthened these findings.

Surprisingly, Choi et al. revealed that stromal EmCs from patients with endometriosis expressed significantly lower levels of AQP9 compared to a healthy group, as measured by the NanoString nCounter System [143]. Silencing AQP9 resulted in an increased expression of pMAPK, as well as enhanced migration and invasion potentials as measured by wound healing and Transwell assays, respectively [143].

To our knowledge, other than these studies by Jiang et al. Shu et al. and Choi et al. there is no other published research on the role of AQPs expressly in endometriosis. It is worth noting two studies that utilized endometrial carcinoma and endometrial epithelial cells and elucidated that AQP2 and AQP3 expression, respectively, increase the cell’s migratory, invasion, adhesion, and proliferation capabilities [113, 148]. Endometriosis and endometrial cancer are two distinct conditions but share several symptoms and themes of cell metastasis and invasion in common. Moreover, endometriosis can frequently be associated with endometrial adenocarcinoma or other malignancies. Given that the results from these two publications closely resemble the results from the Jiang et al. and Shu et al. endometriosis research, it would be intriguing to explore more about whether AQPs play an analogous role in the progression of both endometrial cancer and endometriosis.

Overall, the findings discussed in this section suggest that AQP expression and function play intimate roles in the cell migration and invasion processes in endometriosis pathophysiology. Still, many knowledge gaps remain in this field. Further investigation into the functions of AQPs in intracellular signaling pathways relevant to endometriosis, such as ERK/p38 MAPK, PI3K/Akt, and Wnt, is warranted. Moreover, the specific mechanisms by which AQPs may enhance EmC motility and invasiveness in endometriosis are still unclear. The role of AQPs in EmC invasion into confined spaces, such as the peritoneal mesothelium or within the uterine wall, is also unknown. Finally, beyond wound healing and Transwell invasion assays, there is a need for better in vitro models of endometriosis to reflect the various types of cell migration that lead to 3D implants and flat lesions. For a disease about which so little is known, it is especially important to have a variety of models and methods to maximize the rigor and robustness of the foundational research being performed.

Arthritis

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is an autoimmune disease characterized by swollen joints, synovial hyperplasia, and cartilage damage [149]. Though the progression of the disease isn’t fully understood, it is believed that fibroblast-like synoviocytes (FLS) play a key role in RA progression. RA is associated with FLS migration into the surrounding cartilage and bone, where FLS degrade the bone and lead to RA joint destruction [150]. Zhou et al. found that in the FLS cell line MH7A, AQP1 overexpression increases migration and invasion, while silencing AQP1 reverses these effects [151]. Increased FLS migration is influenced by cytoskeletal dynamics, where AQP1 overexpression leads to increased expression of F-actin stress fibers and a more dynamic cytoskeletal reorganization. These cytoskeletal rearrangements could be mediated by AQP1 activation of Wnt/ β-catenin [151]. This same AQP1-activated β-catenin mechanism mediates RA FLS migration in rat collagen [152]. AQP9 is also expressed on FLS, with increased expression in the presence of TNF-alpha, potentially linking AQP9 with RA progression [153]. Furthermore, in adjuvant-induced arthritis, another model of rat induced arthritis, AQP4 levels in articular chondrocytes correlate with paw swelling and joint damage. Inhibition of AQP4 in articular chondrocytes effectively prevents dysfunction by increasing cell proliferation and type-II collagen deposition [154].

Cardiac disease

Cardiac diseases are conditions that affect the structure or function of the heart. One study found that in AQP1 -/- mice, there was a decrease in left ventricular wall thickness (12% reduction), cardiac muscle fiber cross sectional area (17%), and capillary density (10%) [155]. Though this led to no alteration in cardiac function, it was believed the decrease in size led to decreased cardiac output. This revealed that AQP1 is essential for the development of healthy heart tissue. It is possible that the decreased capillary density, caused by reduced AQP1-mediated angiogenesis, deprived cardiac muscles from the nutrients necessary to fully develop. In another study, after an induced heart attack in rabbits, there was increased expression of AQP1 in blood vessels surrounding the infarct region; this correlated with the pattern of neovasculature and increased water content around the infarct border [156].

Aquaporin-based drugs

Due to the increased understanding of the role that AQPs can play in the progression of disease-related cell migration, the ability to modulate cell AQP expression could be a viable therapeutic. Since AQPs possess an extracellular domain, these transmembrane proteins may act as an ideal target for drug delivery. We have compiled some of the drugs that have recently been investigated in manipulating cell expression of various AQPs in the context of cell migration. We also note that although there is not yet a single drug that is FDA-approved and that successfully targets AQPs universally [157], the multi-functional role of AQPs in cell migration (as we reviewed here) may open opportunities for targeting AQPs in other novel ways besides the traditional pore-blocking approach. We refer the reader to several other review papers for a more in-depth perspective into AQP-based drugs [158–160].

miRNAs

miRNAs can downregulate AQPs

The typical approach to understand the potential of miRNAs as a therapeutic is to transfect AQP-expressing cells with a specific miRNA and observe the resulting AQP expression and AQP-induced migration. In MDA-MB-231 cells, miR-19b-3p and miR-1226-3p reduce the expression of AQP5, which reduces cell proliferation and migration. Transfection of these miRNAs has utilized exosomes with high expression of IL-4RPep-1 to bind to the IL-4-receptor overexpressing MDA-MB-231 cells [161]. Also, in patient-derived breast cancer samples, miR-320 downregulates AQP1 expression and thus cell proliferation, migration, and invasion [162]. In HUVECs, miR-133a-3p.1 suppresses AQP1 expression, thereby reducing cell proliferation, migration, and tube formation [163]. miR-320a can reduce glioma cell AQP4 expression and thus their invasion and migration [164]. miR-325p inhibits HCC proliferation and induces apoptosis in HCC by downregulating AQP5 [165]. Finally, overexpression of miR-1271-5p inhibits HCC viability, migration, and invasion, while attenuating HBV infection and impeding tumor growth in vivo by targeting AQP5 [166].

miRNAs are downregulated in diseases

Interestingly, the expression of miRNA is decreased in many disease states, the most studied being cancer. In HCCs, tissues with an increased AQP3 expression also show a decrease in miR-124 expression. Overexpressing miR-124 in HCCs leads to a decrease in AQP3 expression and suppression of cell proliferation and migration [98]. In colorectal cancer (CRC), miR-133a-3p is significantly downregulated, while AQP1 is upregulated. The same study found that miR-133-3p/AQP1 expression is correlated with tumor stage and that AQP1 overexpression is reversed upon overexpression of miR-133a-3p [167]. miR-185-3p is also downregulated in CRC tissues and is inversely correlated with the cells' AQP5 expression. Cells with downregulated miR-185-3p also demonstrate a resistance to the chemotherapy 5-FU. Overexpressing miR-185 leads to an increase in cell chemosensitivity, and a decrease in AQP5 expression, resulting in a reduction of cell migration [168]. In gastric cancer clinical samples, miR-874 levels are significantly downregulated and inversely correlated with AQP3. Upon overexpression of miR-487, there is a decrease in Bcl-2, membrane matrix type 1–matrix metalloproteinase (MT1-MMP), MMP2, and MMP9 levels, with an upregulation of caspase-3 and Bax activity. miR-874 enacts these changes by binding directly with AQP3 mRNA, thus reducing AQP3 expression levels and decreasing subsequent migration and invasion [169].

Though studies were conducted across different cell lines to elucidate the effect of miRNA on AQPs, given the mechanisms by which miRNAs function, it could be inferred that their function in regulating specific AQP isoform expression is maintained across various cell lines. Designing ways to deliver miRNAs to target cell populations could be a future direction for influencing cellular AQP expression and resulting migration.

RNA sponges

When considering miRNAs for therapeutic purposes, one must also consider the variable of RNA sponges. These sponges contain complementary binding sites to miRNAs of interest, thereby causing a loss of miRNA function. Modulating the expression of these sponges could result in the upregulation or downregulation of AQP expression. The circular RNA (circRNA) circ-STIL is highly expressed in CRC, facilitating its progression. The miR-345-5p, shown to inhibit AQP3, is significantly downregulated in HCC tissues, likely mediated by the increase in circ-STIL. This increase in AQP3 leads to a more aggressive cancer [88]. Also in HCC, circHIPK3 acts as an miR-124 sponge, thereby increasing AQP3 expression. Suppression of circHIPK3 decreases AQP3 expression, likely mediated by the resulting increase in miR-124 expression; circHIPK3 suppression and its ensuing role in HCC cancer metastasis has been confirmed in vivo in a mouse metastasis model [89]. Long noncoding RNA (lncRNA) LINC00461 has been confirmed to be a sponge for the AQP4 suppressing miR-216a. Upon reduction of miR-216a by LINC00461, there is an increased AQP4 expression, and thus increased proliferation, migration, and invasion of U251 and A172 cells [91].

Aquaporin inhibitors

Many inhibitors have been found to possess high activities with respect to AQPs, yet none have been clinically approved to modulate AQP-mediated migration. High-throughput drug screening and computer aided drug design could help expedite the process for discovering high affinity drugs with clinically relevant implications [170]. Currently, most research toward identifying AQP inhibitors has been focused on the following small molecules:

Heavy metals

In early studies of the permeability of AQPs, the most well-established water channel inhibitors were sulfhydryl-reactive mercurials. These mercurials inhibit AQP1 channel function by covalently modifying the C187 residue. The heavy metal ions Ag+++ and Ag+ are also confirmed to be AQP1 and AQP3 inhibitors. The mechanism by which Ag+ and Ag+++ inhibit AQP1 remains unknown, but it has been shown that they bind to AQP3’s C40 residue [171]. Additionally, polyoxotungstates P2W12, and P2W18 impair melanoma migration between 55% and 65% due to blockage of AQP3 permeability [143]. Though these molecules have a high efficiency in AQP blockage in vitro, they are non-specific and extremely toxic to living cells [172]. Thus, the pursuit of finding safe and specific therapeutics continued following these early studies.

Acetazolamide

Further studies have been conducted to discover a less-toxic inhibitor to reduce expression and function of AQPs. One such drug is the carbonic anhydrase inhibitor acetazolamide (AZA), which is an FDA-approved diuretic agent used in treating water retention-related diseases. AZA’s function was later determined to occur due to decreased AQP1 expression, and thus a reduction in the cell’s water permeability [173]. AZA was first implicated in cell migration by inhibiting AQP1, thus suppressing tumor metastasis in mice [174]. The same group also found a decrease in the number of capillaries invading into tumor tissue following treatment with acetazolamide [175]. It should be noted that the exact mechanisms and consistent function of AZA on AQP function have shown variable results. Yu et al. found that there was, surprisingly, an increase in AQP1-dependent proximal tubular cell migration following ischemia–reperfusion kidney injury after treatment with AZA [176]. Verkman's research group reported that AZA did not inhibit AQP1 in osmotic water permeability tests [172]. Supporting this finding, AQP1-expressing Xenopus leavis oocytes displayed no change in water permeability when subjected to AZA treatment [177]. It is possible that water flux or fluid transport assays have been misinterpreted, since the substrates of carbonic anhydrase are water and bicarbonate. As AZA is already FDA-approved, the pipeline to a clinical AQP-based therapeutic is dramatically decreased; however, more studies must be conducted to fully understand how (and if) AZA inhibits function and expression of AQPs before the leap to the clinic is made.

Bumetanide-derived AqB drugs

In 2009, Migliati et al. developed a synthetic molecule based on a loop diuretic bumetanide named AqB013 that can block the channel function of AQP1 [178]. Another study by the same group found that AqB013 and an ion channel blocker, AqB050, induce anti-tubulogenic effects in HUVECs, by inhibiting AQP1-based cell migration [179]. Again, this group also found that the blockade of AQP1 using AqB013 shows a significant inhibition of cell migration and invasion in CRC. There was almost a complete inhibition of endothelial tube formation after AqB013 treatment [64]. Similar bumetanide-derived compounds, AqB007 and AqB011, were later found to inhibit AQP1 channel function and decrease migration in CRC cells [66]. Using bumetanide on human microvasculature retinal endothelial cells under hypoxic conditions, there was a significant dose-dependent reduction in oxidative stress and angiogenesis biomarkers. These results were accompanied by reductions in migration, tube formation, and AQP1-AQP7 expression. This reduction of AQPs has been postulated to reduce angiogenesis permeabilization, causing retinal edema, though this has not yet been tested [180]. From this, it could be concluded that bumetanide and synthetic-derived compounds pose as viable and less-toxic AQP inhibitors. However, it should be noted that all positive data regarding bumetanide derivatives are from a single research group, while others have been unable to reproduce these results [181]. Given that bumetanide is clinically used as an NKCC1 inhibitor, this drug is likely to have significant effects in transmembrane osmotic gradients in water transport. This could confound the results of those studies and lead to a potential misinterpretation of the data.

Aside from the more well-studied AQP inhibitors described above, other less-studied drugs have also been implicated in the inhibition of both AQP function and expression, as described in the next few sections below.

Drugs that block AQP function

The channel molecule bacopaside II, derived from the plant Bacopa monnieri, blocks water transport function of AQP1 in Xenopus oocyte cells [182]. Bacopaside II reduces cell migration in CRC cells, while also inhibiting endothelial tube formation [67, 183]. The furan-based compounds 5-hydroxymethly-furfural (5HMF), 5-nitro-2furoic acid (5NFA), and 5-acetoxymethly-2-furaldehyde (5AMF) were predicted to bind in silico with the G165 residue of AQP1s D-loop [68]. Upon treatment of multiple CRC cell lines and MDA-MB-231 cells, 5HMF, 5NFA, and 5AMF binding with AQP1 results in no change of cell water fluxes; however, binding does result in the decrease of cell migration, invasion, and cytoskeletal re-arrangement across all cell lines tested [68]. This promising inhibition is likely mediated by a reduced interaction between AQP1 and its downstream signaling pathways.

Drugs that reduce AQP expression

Aside from inhibiting the function of the AQPs directly, other studies have investigated compounds capable of reducing the overall expression of AQPs in the cell. The drug Goreisan reduces HUVEC VEGF-initiated migration in vitro and in vivo, likely by regulating the coinciding downregulation of ERK. Goreisan treatment also reduces the mRNA levels of AQP1, whose expression has previously been shown to be regulated by the ERK pathway [184]. The well-known anti-ovarian cancer drug, curcumin, was shown to reduce ovarian cancer migration and invasiveness marked by a decrease in AQP3 expression and an inhibition of EGFR and AKT/ERK-induced effects [31].

Also, ginsenoside Rg3 epimers demonstrate anti-angiogenic properties. Among the changes following Rg3 treatment, there is a decrease in AQP1 expression, in concert with decreases in PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling [185]. The Rg3 epimers have a dose-dependent inhibition of endothelial cell migration and invasion. The same group found that Rg3 is capable of significantly inhibiting AQP1 expression in PC-3M prostate cancer cells, with an ensuing reduction of cell migration. Investigating the mechanisms of action, the study found Rg3 treatment triggers the activation of p38 MAPK to reduce AQP1 expression [186]. This is surprising because other studies have discovered that AQP1 expression is increased upon MAPK activation; thus, this result further emphasizes that the field still holds many unknowns regarding AQP function and expression [47].

Drugs that increase aquaporin expression

In other disease response pathways, such as wound healing or the immune response, designing drugs that can increase cell migratory capabilities by increasing AQP expression could provide favorable outcomes. One such drug is the licorice-derived compound 18β-glycyrrhetinic acid, which promotes dermal fibroblast migration and proliferation by upregulating AQP3. This increased AQP3 expression likely occurs via the AKT signaling pathway [187]. Another drug, Fasudil, attenuates LPS-induced lung injury, decreases edema, and increases IL-6 production via inhibition of ROCK [188]. In a study involving a lung injury model, LPS reduced AQP5 expression, yet after Fasudil treatment, AQP5 expression was restored with a coinciding decrease in NF-κB activation [189]. It is likely the Fasudil aids in the healing of lung injuries through upregulation of AQP5 to clear lung edema, while reducing the NF-κB inflammation [189]. Furthermore, epidermal growth factor induces fibroblast migration while also increasing AQP3 expression in a dose-dependent manner. Upon blockade or inhibition of EGF, ERF receptor (EGFR), or MAPK/ERK pathways, there is a reduction in AQP3 expression and resulting migration [190].