Abstract

BACKGROUND

Vonoprazan (VPZ)-based regimens are an effective first-line therapy for Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection. However, their value as a rescue therapy needs to be explored.

AIM

To assess a VPZ-based regimen as H. pylori rescue therapy.

METHODS

This prospective, single-center, clinical trial was conducted between January and August 2022. Patients with a history of H. pylori treatment failure were administered 20 mg VPZ twice daily, 750 mg amoxicillin 3 times daily, and 250 mg Saccharomyces boulardii (S. boulardii) twice daily for 14 d (14-d VAS regimen). VPZ and S. boulardii were taken before meals, while amoxicillin was taken after meals. Within 3 d after the end of eradication therapy, all patients were asked to fill in a questionnaire to assess any adverse events they may have experienced. At least 4-6 wk after the end of eradication therapy, eradication success was assessed using a 13C-urea breath test, and factors associated with eradication success were explored.

RESULTS

Herein, 103 patients were assessed, and 68 patients were finally included. All included patients had 1-3 previous eradication failures. The overall eradication rates calculated using intention-to-treat and per-protocol analyses were 92.6% (63/68) and 92.3% (60/65), respectively. The eradication rate did not differ with the number of treatment failures (P = 0.433). The rates of clarithromycin, metronidazole, and levofloxacin resistance were 91.3% (21/23), 100.0% (23/23), and 60.9% (14/23), respectively. There were no cases of resistance to tetracycline, amoxicillin, or furazolidone. In 60.9% (14/23) patients, the H. pylori isolate was resistant to all 3 antibiotics (clarithromycin, metronidazole, and levofloxacin); however, eradication was achieved in 92.9% (13/14) patients. All patients showed metronidazole resistance, and had an eradication rate of 91.3% (21/23). The eradication rate was higher among patients without anxiety (96.8%) than among patients with anxiety (60.0%, P = 0.025). No severe adverse events occurred; most adverse events were mild and disappeared without intervention. Good compliance was seen in 95.6% (65/68) patients. Serological examination showed no significant changes in liver and kidney function.

CONCLUSION

VAS is a safe and effective rescue therapy, with an acceptable eradication rate (> 90%), regardless of the number of prior treatment failures. Anxiety may be associated with eradication failure.

Keywords: Vonoprazan, Saccharomyces boulardii, Rescue therapy, Helicobacter pylori, Eradication, Anxiety

Core Tip: Vonoprazan (VPZ)-containing triple therapies have been shown to contribute to global antimicrobial resistance, while Saccharomyces boulardii (S. boulardii) supplementation has significantly improved Helicobacter pylori eradication rates and decreased adverse events. This study revealed that the VPZ and amoxicillin dual regimen with S. boulardii supplementation is safe and effective H. pylori rescue therapy, regardless of the number of prior treatment failures. Acceptable eradication rates (> 90%) were achieved in patients with resistance to clarithromycin, metronidazole, and levofloxacin. However, the regimen may need to be adjusted for patients with anxiety.

INTRODUCTION

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori), which infects over 50% of the global population, is a leading cause of chronic gastritis, peptic ulcer disease, and gastric cancer. The eradication of H. pylori can effectively prevent peptic ulcer recurrence and lower gastric cancer incidence[1,2]. In regions with high antibiotic resistance, such as China, 14-d bismuth-containing quadruple therapy (BQT) is the recommended first-line treatment for H. pylori infection[3-5]. However, as the rates of resistance to clarithromycin, metronidazole, and levofloxacin have markedly increased worldwide, BQT fails to eradicate H. pylori infection in approximately 15%-20% patients[6,7]. Multiple failed attempts at eradication therapy tend to increase the prevalence of multidrug-resistant strains, making rescue treatment more difficult[8,9]. Unlike the above antibiotics, the rates of primary and secondary resistance of H. pylori to amoxicillin have remained low and stable[10]. Amoxicillin shows a pH- and time-dependent bactericidal effect. Recently, high-dose, high-frequency dual therapy with amoxicillin and a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) was reported to show promising outcomes when used as a first-line or rescue treatment for the eradication of H. pylori[11,12]. The Maastricht VI/Florence Consensus Report recommends high-dose dual therapy with a PPI plus amoxicillin as a rescue therapy for H. pylori infection[5].

Vonoprazan (VPZ), the first clinically available potassium-competing acid blocker (P-CAB), produces a more rapid and sustained acid inhibition effect than PPIs[13]. Therefore, VPZ-amoxicillin dual therapy (VA-dual) is expected to be more effective than PPI-amoxicillin dual therapy. In recent years, first-line treatment with VA-dual, consisting of amoxicillin (3 g/d or less) and VPZ (40 mg/d), has been reported to achieve eradication rates of 78.5%-93.5%[14-17]. However, limited reports are available on the success rate of VA-dual as a rescue treatment for H. pylori infection; only one retrospective study conducted in China has reported a successful eradication rate of 92.5% after VA-dual[18]. However, the regimens were not consistent, and the frequencies of the amoxicillin and VPZ doses varied. Therefore, further optimization of VA-dual as a rescue treatment is warranted.

Some recent consensus guidelines for the management of H. pylori infection have proposed that certain probiotics can effectively decrease the gastrointestinal side effects of H. pylori eradication therapies[3-5]. A recent meta-analysis demonstrated that Saccharomyces boulardii (S. boulardii) supplementation during standard eradication therapy (triple regimen, sequential regimen, or quadruple regimen) significantly improved eradication rates and decreased the overall incidence of adverse events[19]. However, few studies have evaluated the effects of S. boulardii as a supplement to the VA-dual regimen in terms of the eradication rate of H. pylori and treatment-related adverse events.

Therefore, the aim of this prospective study was to determine the safety and efficacy of VA-dual plus S. boulardii supplementation as a rescue treatment for patients with H. pylori infection. We additionally explored potential factors influencing eradication rates, and put forward our recommendations to improve H. pylori eradication rates in clinical practice.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Statement of ethics and trial registration

Ethical approval for this pilot study was obtained from Affiliated Changzhou No. 2 People’s Hospital of Nanjing Medical University [No. (2021) YLJSD004]. The study adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients prior to their enrollment in this study. The study has been registered in the Chinese Clinical Trial Registry (No. ChiCTR2200055125).

Study participants

Patients who attended our center between January and August 2022 were screened for their eligibility to participate in this study. The detailed inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Patients aged over 18 years; (2) patients with a history of at least one failed H. pylori eradication treatment; and (3) a minimum 6-mo interval after the end of the last treatment. The following exclusion criteria were applied: (1) A history of gastric surgery; (2) severe concomitant diseases such as hepatic or renal dysfunction; (3) allergy or contraindication to the drugs used in the study regimen; (4) pregnancy or lactation; (5) treatment with a PPI, bismuth, or an antibiotic within 4 wk before the study treatment; (6) alcohol abuse or drug addiction; and (7) lack of informed consent.

Study design and outcomes

Before enrollment, the patients’ demographic data, clinical characteristics, and any concomitant diseases were recorded through medical records and physician interviews. The diagnosis of H. pylori infection was based on a positive result of at least one of the following tests: 13C-urea breath test (13C-UBT), rapid urease test, and histological examination. Some patients also underwent gastroscopy, and H. pylori culture and antimicrobial susceptibility testing before treatment. Serum chemistry tests were performed before and after treatment.

All patients were administered VPZ (20 mg twice daily; Takeda Pharmaceutical, Tokyo, Japan), amoxicillin (750 mg 3 times daily; Federal Pharmaceutical, Hong Kong, China), and S. boulardii (250 mg twice daily; Laboratoires BIOCODEX, France) for 14 d (14-d VAS regimen). VPZ and S. boulardii were taken before meals, while amoxicillin was taken after meals. Patients who felt unwell during treatment or forgot to take their medication were advised to contact the investigators immediately.

All patients were asked to keep the remaining drugs after treatment and fill out the relevant questions in the questionnaire within 3 d after the end of eradication therapy. Adverse events and patient compliance were assessed using the questionnaires and the patients’ medication diaries. The intensity of the adverse events was graded as follows: None; mild, causing discomfort but not interfering with daily life; moderate, causing discomfort and interfering with daily life; and severe, causing discomfort requiring cessation of treatment. Patient compliance was rated as good if the patient had taken > 80% of all medications prescribed, and as poor, if not[20]. All patients underwent repeat 13C-UBT for the assessment of H. pylori infection 4-6 wk after the end of eradication therapy. The H. pylori status was interpreted as positive when the δ value was greater than the baseline value of 4, and as negative when the δ value was less than the baseline value of 4. If the δ value exceeded the baseline value, which was between 4 and 6, the test was repeated 1 mo later.

The primary endpoint of this study was the H. pylori eradication rate, as confirmed by a negative 13C-UBT. All patients were included in the intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis. Patients who did not undergo a 13C-UBT during follow-up were considered to have treatment failure in the ITT analysis. Patients who failed to attend follow-up assessments and those with poor compliance were excluded from the per protocol (PP) analysis. The secondary endpoints were the rate of adverse events, patient compliance, resistance to antibiotics, and factors related to the eradication rate.

H. pylori culture and antimicrobial susceptibility testing

From patients who underwent gastroscopy, we collected 2 biopsy specimens for H. pylori culture, one from the gastric antrum and another from the gastric corpus. Both specimens were stored at -80 °C in brain-heart infusion broth (Oxoid, Basingstoke, United Kingdom) and immediately transported to Zhiyuan Medical Laboratory Institute (Hangzhou, Zhejiang Province, China) for testing. Fully ground specimens were cultured and maintained for 3-7 d in brain-heart infusion agar medium (Oxoid, Basingstoke, United Kingdom) supplemented with 5% defibrinated sheep blood at 37 °C in a low-oxygen environment (85% N2, 10% CO2, and 5% O2). H. pylori isolates were identified on the basis of colony morphology and urease, catalase, and oxidase positivity.

The standard agar plate dilution method was used to assess H. pylori susceptibility to commonly used antibiotics. Minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) were calculated after 72 h of culture at 37 °C in a low-oxygen environment. We used H. pylori ATCC43504 (NCTC11637) for quality control. Antibiotic resistance was defined at the following MIC values: ≥ 1 µg/mL for clarithromycin, ≥ 8 µg/mL for metronidazole, and ≥ 2 µg/mL each for amoxicillin, furazolidone, levofloxacin, and tetracycline. The MIC values for antibiotic resistance were obtained from the fourth edition of the National Guide to Clinical Laboratory Procedures[21].

Sample-size calculation and statistical analysis

We assumed a 93% eradication rate with VPZ-based rescue therapy[22]. The 95% confidence interval was 86.6%-99.4%, and the sample size was 64 patients. Assuming a 5% follow-up loss, at least 68 patients would be required. Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± SD, and compared between groups by using the t test or Mann-Whitney U test. Categorical variables were expressed as numbers with percentages, and compared between groups by using the Fisher exact test or Pearson χ2 test. Statistical significance was inferred at P values < 0.05. All statistical analyses were conducted using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences v23.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY, United States) and Power Analysis and Sample Size software v15.0.5 (NCSS LLC, Kaysville, UT, United States).

RESULTS

Patient characteristics

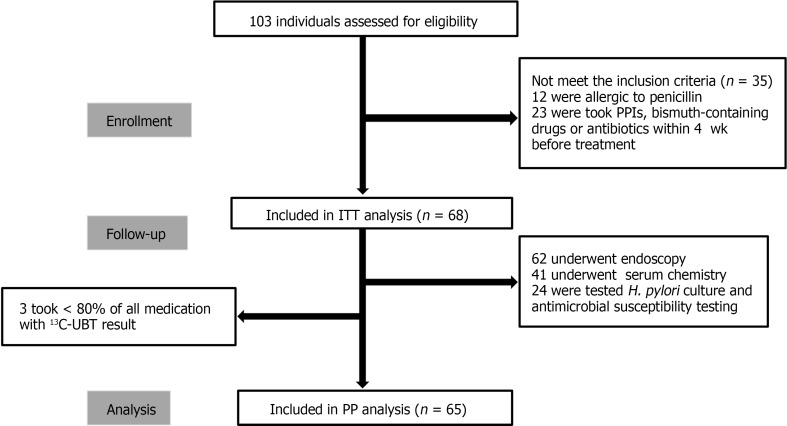

We screened a total of 103 patients for eligibility, and excluded 35 patients who did not meet the inclusion criteria. Thus, finally, 68 patients were enrolled in this study, of whom 62 patients underwent endoscopy, 41 patients underwent serological testing before and after treatment, and 24 patients underwent antimicrobial susceptibility testing. Three patients were excluded from the PP analysis due to poor compliance despite a negative 13C-UBT during follow-up (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the study. PPI: Proton pump inhibitor; ITT: Intention-to-treat analysis; PP: Per-protocol analysis; UBT: Urea breath test; H. pylori: Helicobacter pylori.

Of the 68 patients, 20 were men and 48 were women (Table 1). Prior to the present treatment, 47 patients had undergone treatment once, 15 patients had undergone treatment twice, and 6 patients had undergone treatment 3 times. Most patients were asymptomatic (n = 37, 54.4%). The most common concomitant diseases were hypertension (n = 14, 20.6%) and diabetes (n = 9, 13.2%); 4 patients (5.9%) had anxiety disorder. The most common previous treatment regimen was BQT, and the most commonly used antibiotics were amoxicillin, levofloxacin, clarithromycin, and metronidazole, with a few patients using furazolidone.

Table 1.

Clinicodemographic characteristics of the study patients, n (%)

|

Characteristic

|

Total No. of patients (n = 68)

|

Number of prior eradication failures

|

||

|

1 (n = 47)

|

2 (n = 15)

|

3 (n = 6)

|

||

| Sex (male) | 20 (29.4) | 10 (21.3) | 6 (4.0) | 4 (66.7) |

| Age (yr), mean ± SD | 49.60 ± 10.57 | 49.94 ± 10.00 | 48.87 ± 12.65 | 48.83 ± 11.27 |

| Height (m), mean ± SD | 1.63 ± 0.07 | 1.62 ± 0.09 | 1.64 ± 0.08 | 1.68 ± 0.10 |

| Weight (kg), mean ± SD | 59.52 ± 12.30 | 56.83 ± 12.19 | 63.80 ± 9.94 | 69.92 ± 11.50 |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean ± SD | 22.31 ± 3.64 | 21.59 ± 3.98 | 23.63 ± 2.04 | 24.63 ± 1.80 |

| Lifestyle factors | ||||

| Smoking | 5 (7.3) | 4 (8.5) | 0 (0) | 1 (16.7) |

| Drinking | 4 (5.9) | 0 (0) | 1 (6.7) | 3 (50.0) |

| Symptom | ||||

| Abdominal pain | 7 (10.3) | 5 (10.6) | 2 (13.3) | 0 (0) |

| Bloating | 6 (8.8) | 4 (8.5) | 2 (13.3) | 0 (0) |

| Diarrhea | 1 (1.5) | 0 (0) | 1 (6.7) | 0 (0) |

| Halitosis | 1 (1.5) | 1 (2.1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Belching | 13 (19.1) | 8 (17.0) | 3 (20.0) | 2 (33.4) |

| Nausea | 2 (2.9) | 2 (4.3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Bitter taste | 1 (1.5) | 1 (2.1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Asymptomatic | 37 (54.4) | 26 (55.3) | 7 (46.7) | 4 (66.7) |

| Concomitant disease | ||||

| Diabetes mellitus | 9 (13.2) | 8 (17.0) | 1 (6.7) | 0 (0) |

| Hypertension | 14 (20.6) | 7 (14.9) | 5 (33.3) | 2 (33.4) |

| Anxiety disorder | 4 (5.9) | 1 (2.1) | 2 (13.3) | 1 (16.7) |

| Gastroscopy findings | ||||

| Atrophic gastritis | 33 (48.6) | 27 (57.4) | 4 (26.7) | 2 (33.4) |

| Non-atrophic gastritis | 24 (35.3) | 14 (29.8) | 8 (53.3) | 2 (33.4) |

| Peptic ulcer | 4 (5.9) | 1 (2.1) | 1 (6.7) | 2 (33.4) |

| Polyp | 1 (1.5) | 0 (0) | 1 (6.7) | 0 (0) |

| Not applicable (no gastroscopy done) | 6 (8.9) | 5 (10.6) | 1 (13.3) | 0 (0) |

BMI: Body mass index.

H. pylori culture and antimicrobial susceptibility testing

Of the 68 patients, 24 (35.3%) underwent H. pylori culture and antimicrobial susceptibility testing. H. pylori was successfully isolated in 95.8% (23/24) of patients. The rates of resistance to metronidazole, clarithromycin, and levofloxacin were 100% (23/23), 91.3% (21/23), and 60.0% (14/23), respectively. There were no cases of resistance to tetracycline, amoxicillin, or furazolidone. The triple drug-resistance rate (to metronidazole, levofloxacin, and clarithromycin) was 56.3% (9/16) among patients with one prior treatment failure, which increased to 71.4% (5/7) among patients with 2 or more prior treatment failures.

Eradication rate and factors influencing efficacy

The overall eradication rates of 14-d VAS calculated using the ITT and PP analyses were 92.6% (63/68) and 92.3% (60/65), respectively. In 2 of the 5 patients in whom eradication failed, further treatment with VPZ 20 mg twice daily, amoxicillin 1000 mg 3 times daily, and S. boulardii 250 mg twice daily for 14 d successfully eradicated the infection. The remaining 3 patients had not yet received additional rescue therapy at the time of writing as less than 6 mo had passed since the end of the previous treatment.

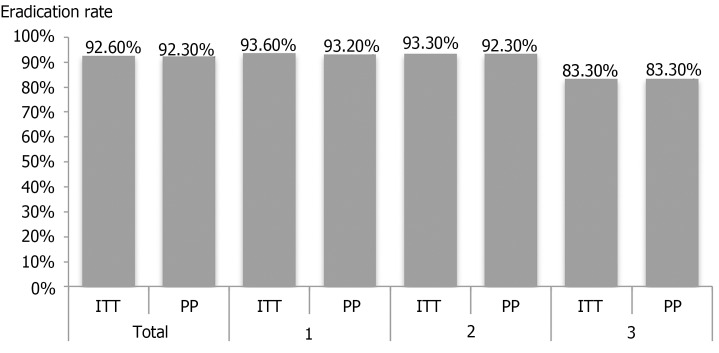

We stratified the H. pylori eradication rate by the number of prior treatment failures (Figure 2). The ITT analysis showed that the eradication rates were 93.6%, 93.3%, and 83.3% (P = 0.433) among patients with 1, 2, and 3 prior treatment failures, respectively. The corresponding eradication rates according to the PP analysis were 93.2%, 93.3%, and 83.3% (P = 0.585). We found that the eradication rate did not significantly differ with the number of previous treatment failures. In addition, eradication rates did not differ between patients who had previously received amoxicillin and those who had not (85.0% vs 95.8%, P = 0.433).

Figure 2.

Eradication rates stratified by number of prior treatment failures. ITT: 93.6% vs 93.3% vs 83.3%, P = 0.433; PP: 93.2% vs 93.3% vs 83.3%, P = 0.585). ITT: Intention-to-treat analysis; PP: Per-protocol analysis.

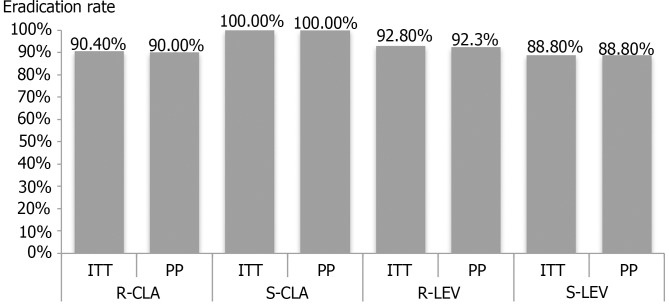

Among the 23 patients who successfully underwent H. pylori culture and antimicrobial susceptibility testing, the ITT analysis showed that similar eradication rates were achieved in the clarithromycin-resistant (90.4%) and clarithromycin-sensitive groups (100%; P = 1.00). PP analysis also showed that the eradication rate did not differ between the clarithromycin-resistant and clarithromycin-sensitive groups (90.0% vs 100%, respectively, P = 1.00). Similarly, we found no significant difference in the H. pylori eradication rate between the levofloxacin-resistant and levofloxacin-sensitive groups (ITT: 92.8% vs 88.8%, respectively, P = 1.00; PP: 92.3% vs 88.8%, respectively, P = 1.00; Figure 3). All patients showed metronidazole resistance, and had an eradication rate of 91.3% (21/23). Notably, eradication was achieved in 92.9% (13/14) patients who showed triple drug resistance (clarithromycin, metronidazole, and levofloxacin).

Figure 3.

Impact of bacterial antibiotic resistance on eradication rate. ITT: Clarithromycin resistant vs clarithromycin sensitive, P = 1.00; levofloxacin resistant vs levofloxacin sensitive, P = 1.00; PP: Clarithromycin resistant vs clarithromycin sensitive, P = 1.00; levofloxacin resistant vs levofloxacin sensitive, P = 1.00). R-CLA: Clarithromycin resistant; S-CLA: Clarithromycin sensitive; R-LEV: Levofloxacin resistant; S-LEV: Levofloxacin sensitive; ITT: Intention-to-treat analysis; PP: Per-protocol analysis.

Anxiety disorder was found to be a risk factor for eradication failure (40.0% vs 3.2%, P = 0.025; Table 2). No significant differences in age, sex, height, weight, body mass index, concomitant diseases, gastroscopy findings, and number of prior treatment failures were found between patients with successful and failed rescue therapy.

Table 2.

Factors potentially influencing Helicobacter pylori eradication, n (%)

|

Factor

|

Eradication failure (n = 5)

|

Successful eradication (n = 63)

|

P value

|

| Sex (male) | 2 (40.0) | 18 (28.6) | 0.627 |

| Age (yr), mean ± SD | 54.40 ± 5.86 | 49.22 ± 10.80 | 0.295 |

| Height (m), mean ± SD | 1.62 ± 0.10 | 1.62 ± 0.07 | 0.778 |

| Weight (kg), mean ± SD | 64.60 ±11.42 | 59.12 ± 12.37 | 0.129 |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean ± SD | 24.43 ± 1.88 | 22.14 ± 3.70 | 0.112 |

| Concomitant disease | |||

| Diabetes mellitus | 1 (20.0) | 8 (12.7) | 0.520 |

| Hypertension | 1 (20.0) | 13 (20.6) | 1.000 |

| Anxiety disorder | 2 (40.0) | 2 (3.2) | 0.025 |

| Gastroscopy findings | |||

| Atrophic gastritis | 2 (40.0) | 31 (49.2) | 1.000 |

| Non-atrophic gastritis | 3 (60.0) | 21 (33.3) | 0.337 |

| Peptic ulcer | 0 (0.0) | 4 (6.3) | 1.000 |

| Polyp | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.6) | 1.000 |

| No. of prior treatments | |||

| 1 | 3 (60.0) | 44 (69.8) | 0.641 |

| ≥ 2 | 2 (40.0) | 19 (30.2) | |

BMI: body mass index.

Adverse events and compliance

A total of 10 patients (14.7%) developed adverse events, including diarrhea (4 patients), skin rash (3 patients), and dry mouth, bloating, and abdominal pain (1 patient each). Most adverse events were mild and disappeared without intervention, except in 2 patients who developed rashes on day 9 and 11, refused continued rescue treatment, and finally recovered after anti-allergy therapy. Another patient discontinued treatment on day 7 because of diarrhea, which improved without intervention. The remaining patients took > 80% of all medications prescribed (compliance rate, 95.6%, 65/68; Table 3). Serum chemistry tests revealed no significant differences in liver and kidney function before and after treatment (Table 4). Among the 10 patients who developed adverse events, only 1 patient (with a rash) had eradication failure.

Table 3.

Adverse events and patient compliance

|

Variable

|

%

|

| Adverse events | |

| Total adverse events | 14.7% (10/68) |

| Dry mouth | 1.5% (1/68) |

| Skin rash | 4.4% (3/68) |

| Bloating | 1.5% (1/68) |

| Diarrhea | 5.9% (4/68) |

| Abdominal pain | 1.5% (1/68) |

| Grade of adverse event | |

| Mild | 70.0% (7/10) |

| Moderate | 30.0% (3/10) |

| Severe | 0% (0/10) |

| 1Compliance | |

| Good | 95.6% (65/68) |

| Poor | 4.4% (3/68) |

Compliance was rated as good if the patient had taken > 80% of all medications prescribed, and as poor, if not.

Table 4.

Comparison of liver and kidney function before and after treatment

|

Characteristic

|

Before (n = 41)

|

After (n = 41)

|

P value

|

| Total bilirubin (μmol/L), mean ± SD | 13.68 ± 4.82 | 14.96 ± 5.22 | 0.252 |

| ALT (U/L), mean ± SD | 16.92 ± 8.33 | 21.46 ± 16.03 | 0.270 |

| AST (U/L), mean ± SD | 18.99 ± 7.61 | 21.03 ± 10.67 | 0.670 |

| Creatinine (μmol/L), mean ± SD | 60.105 ± 12.060 | 60.53 ± 11.35 | 0.974 |

AST: Aspartate transaminase; ALT: Alanine transaminase.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this study is the first to determine the safety and efficacy of 14-d VA-dual plus S. boulardii supplementation as a rescue therapy for H. pylori infection. This VAS regimen achieved an acceptable eradication rate (92.6% by ITT and 92.3% by PP), regardless of the number of prior treatment failures. Most patients could tolerate this regimen, and compliance was good in this Chinese patient population. Except for anxiety disorder, no other factors were observed to be associated with treatment failure. Notably, eradication was successful in 92.9% (13/14) of patients with multiple antibiotic resistance. Therefore, the 14-d VAS regimen is a safe and effective rescue therapy for H. pylori infection.

Currently, H. pylori culture-guided therapy is recommended by most consensus guidelines as a rescue therapy for H. pylori infection. However, culture-guided therapy is not widely used in routine clinical practice[3-5]. Until recently, susceptibility tests still required the microbiological examination of samples obtained through endoscopy, which is invasive and expensive. In addition, many hospitals lack the facilities required to perform H. pylori culture and antimicrobial susceptibility testing, which limits the clinical use of culture-guided therapy in many countries[3,5,20]. Furthermore, H. pylori culture is technically challenging. Several studies have reported culture success rates of < 80% among patients with failure of at least one prior H. pylori eradication treatment[23]. It should be emphasized that in our study, culture was performed in only 35.3% of the patients. This reflects the current state of routine clinical practice in China. Culture-guided therapy has not yet become a routine clinical practice, and rescue therapy is mainly prescribed on an empirical basis in China.

Compared with PPIs, VPZ, the first clinically applied P-CAB, has a faster and stronger acid-inhibition effect[13]. This provides an opportunity to potentially improve H. pylori eradication therapy by simplifying complex regimens and possibly helping to develop effective therapies[5]. In one study, a PP analysis showed that a 7-d VPZ-based regimen (VPZ 20 mg twice daily, sitafloxacin 100 mg twice daily, and amoxicillin 750 mg twice daily) as a third-line therapy resulted in a significantly higher eradication rate than a PPI-based regimen (83.3% vs 57.1%, P = 0.043)[24]. In a small study, a 10-d triple therapy regimen consisting of VPZ 20 mg twice daily, rifabutin 150 mg twice daily, and amoxicillin 750 mg twice daily yielded a 100% eradication rate in 19 patients with ≥ 3 prior treatment attempts[25]. Similarly, in 57 patients administered a 7-d rifabutin-containing triple therapy regimen (VPZ 20 mg twice daily, amoxicillin 500 mg 4 times daily, and 150 mg rifabutin 150 mg once daily) as a third- or later-line H. pylori eradication regimen, the eradication rate was 91.2%[26]. It should be emphasized that all the above studies were conducted in Japan, and they all used triple regimens containing VPZ and amoxicillin. Although the use of 2 antibiotics may lead to higher eradication rates, this practice promotes the use of an unnecessary second antibiotic[27]. Hence, optimization of VPZ-based rescue therapy needs to be further explored. However, the relevant research in China is limited. Only one retrospective study has reported that the 14-d VA-dual regimen (VPZ 20 mg/d or 40 mg/d and amoxicillin 3000 mg/d) was safe and effective as a rescue therapy (92.5%, 172/186); however, the frequencies and doses of VA-dual therapy varied among the patients[18].

The 14-d VAS regimen used in this study offers certain advantages over previous rescue therapies. First, it minimizes the use of antibiotics, which is especially important in the light of the global increase in H. pylori antibiotic resistance. Indeed, VPZ-containing triple therapies have been shown to contribute to global antimicrobial resistance[27]. The 14-d VAS regimen eliminated the need for a second antibiotic while providing remarkable H. pylori eradication efficacy. Second, the optimal amoxicillin dose for dual therapy remains uncertain. Available evidence suggests that a dose of 2 g/d is insufficient, and 3 g or 2.25-3.00 g in split doses (every 6 h or 8 h) may be optimal[27]. Therefore, amoxicillin was administered at a dose of 750 mg 3 times daily in the 14-d VAS regimen. Third, for the first time, we supplemented S. boulardii to VA-dual as a rescue therapy for H. pylori eradication. Several potential mechanisms by which S. boulardii acts as an adjunct to H. pylori eradication therapy have been elucidated: (1) It inhibits the growth and proliferation of H. pylori by upregulating short-chain fatty acids and other antimicrobial substances[28]; (2) it expresses a neuraminidase that reduces the expression of α(2-3)-linked sialic acid on the epithelial cell surface, which prevents the adhesion of H. pylori to the duodenal epithelium[29]; and (3) it reduces the incidence of adverse events and indirectly improves patient compliance, thereby increasing the eradication rate of H. pylori[19].

Poor patient compliance is a main cause of treatment failure, and adverse events are a key factor affecting patient compliance[30]. Our 14-d VAS regimen was well tolerated, and all adverse events were mild or moderate, with diarrhea (5.9%) and rash (4.4%) being the most common. Patient compliance was also good, which may be attributable to the low rate of adverse events and the simplicity of the regimen.

We analyzed the factors potentially influencing the eradication rate of the 14-d VAS regimen. Only anxiety disorder was significantly associated with eradication failure; other factors such as gender, age, smoking, and alcohol consumption were not associated with treatment failure. There is evidence that state anxiety and trait anxiety are related to H. pylori infection. Anxiety appears to heighten the intensity and perception of gastrointestinal signals, which gives patients more reasons to worry about their health, leading to a higher anxiety response, and making patients more inclined to seek medical advice[31]. Thus, identifying patients with anxiety prior to the treatment of H. pylori infection and management by a professional team including a gastroenterologist and a psychologist to improve anxiety may be necessary to improve eradication rates and reduce the costs associated with frequent medical consultations.

This study has some limitations. First, it is impossible to compare the safety and effectiveness of the VA-dual regimen and the VAS regimen because this study is a single-arm pilot study. Large-scale, multicenter randomized controlled trials in areas with different patterns of antibiotic resistance are needed to confirm our results. Second, the number of patients with anxiety disorder in this study was small, and the relevant conclusions and potential mechanisms need to be further explored in future studies. Third, H. pylori culture and antimicrobial susceptibility testing were performed in only 35.3% of our patients, and no resistance was detected to amoxicillin. So, it was impossible to determine whether amoxicillin resistance affected the eradication rate of the 14-d VAS regimen. However, considering that the rates of primary and secondary resistance to amoxicillin are low and stable[10], we believe that the 14-d VAS regimen is an effective rescue therapy. Fourth, this study was underpowered to analyze the association between eradication rate and prior eradication regimens because the study patients had previously been treated with multiple different regimens.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, the 14-d VAS regimen is safe and effective H. pylori rescue therapy, with an acceptable eradication rate (> 90%), regardless of the number of prior treatment failures. This regimen avoids the use of additional antibiotics, but may need to be adjusted for patients with anxiety. Large-scale, multicenter randomized controlled trials are needed to confirm our results.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

Research background

Vonoprazan (VPZ)-containing triple therapies have been shown to contribute to global antimicrobial resistance. Hence, the value of VPZ-based regimens as rescue therapies needs to be explored.

Research motivation

Saccharomyces boulardii (S. boulardii) supplementation significantly improved H. pylori eradication rates and decreased the incidence of adverse events. We are the first to combine S. boulardii supplementation with VPZ-amoxicillin dual therapy (VAS regimen) as a rescue therapy for H. pylori eradication.

Research objectives

To determine the safety and efficacy of the VAS regimen as a rescue treatment for H. pylori infection.

Research methods

We performed a prospective, single-center, clinical trial with the VAS regimen.

Research results

The overall eradication rates calculated using intention-to-treat and per-protocol analyses were 92.6% and 92.3%, respectively. The eradication rate did not differ with the number of treatment failures (P = 0.433). Acceptable eradication rates (> 90%) were achieved in patients with resistance to clarithromycin, metronidazole, and levofloxacin. Most adverse events were mild, and 95.6% patients showed good compliance.

Research conclusions

The VAS regimen is a safe and effective rescue therapy, with an acceptable eradication rate (> 90%), regardless of the number of prior treatment failures.

Research perspectives

Large-scale, multicenter randomized controlled trials in areas with different patterns of antibiotic resistance are needed to confirm our results. It will be necessary to compare the safety and effectiveness of the VPZ-amoxicillin dual therapy regimen with the VAS regimen in the future.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors are grateful to Dr. Liu-Lan Qian for her help in the statistical analysis of this paper.

Footnotes

Institutional review board statement: The study was reviewed and approved by the Clinical Medical Technical Ethics Committee of the Affiliated Changzhou No. 2 People’s Hospital of Nanjing Medical University [approval. No. (2021) YLJSD004].

Clinical trial registration statement: This study is registered at Chinese Clinical trial Registry. The registration identification number is ChiCTR2200055125.

Informed consent statement: All study participants provided informed written consent prior to the study enrollment and declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Conflict-of-interest statement: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

CONSORT 2010 statement: The authors have read the CONSORT 2010 statement, and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the CONSORT 2010 statement.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Peer-review started: February 27, 2023

First decision: March 13, 2023

Article in press: April 23, 2023

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Keikha M, Iran; Krzyzek P, Poland; Nishida T, Japan S-Editor: Chen YL L-Editor: A P-Editor: Cai YX

Contributor Information

Jing Yu, Department of Gastroenterology, The Affiliated Changzhou No. 2 People’s Hospital of Nanjing Medical University, Changzhou 213000, Jiangsu Province, China.

Yi-Ming Lv, Department of Gastroenterology, The Affiliated Changzhou No. 2 People’s Hospital of Nanjing Medical University, Changzhou 213000, Jiangsu Province, China.

Peng Yang, Department of Gastroenterology, The Affiliated Changzhou No. 2 People’s Hospital of Nanjing Medical University, Changzhou 213000, Jiangsu Province, China.

Yi-Zhou Jiang, Department of Gastroenterology, The Affiliated Changzhou No. 2 People’s Hospital of Nanjing Medical University, Changzhou 213000, Jiangsu Province, China.

Xiang-Rong Qin, Department of Gastroenterology, The Affiliated Changzhou No. 2 People’s Hospital of Nanjing Medical University, Changzhou 213000, Jiangsu Province, China.

Xiao-Yong Wang, Department of Gastroenterology, The Affiliated Changzhou No. 2 People’s Hospital of Nanjing Medical University, Changzhou 213000, Jiangsu Province, China. wxy20009@126.com.

Data sharing statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- 1.Zamani M, Ebrahimtabar F, Zamani V, Miller WH, Alizadeh-Navaei R, Shokri-Shirvani J, Derakhshan MH. Systematic review with meta-analysis: the worldwide prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2018;47:868–876. doi: 10.1111/apt.14561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chiang TH, Chang WJ, Chen SL, Yen AM, Fann JC, Chiu SY, Chen YR, Chuang SL, Shieh CF, Liu CY, Chiu HM, Chiang H, Shun CT, Lin MW, Wu MS, Lin JT, Chan CC, Graham DY, Chen HH, Lee YC. Mass eradication of Helicobacter pylori to reduce gastric cancer incidence and mortality: a long-term cohort study on Matsu Islands. Gut. 2021;70:243–250. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-322200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu WZ, Xie Y, Lu H, Cheng H, Zeng ZR, Zhou LY, Chen Y, Wang JB, Du YQ, Lu NH Chinese Society of Gastroenterology, Chinese Study Group on Helicobacter pylori and Peptic Ulcer. Fifth Chinese National Consensus Report on the management of Helicobacter pylori infection. Helicobacter. 2018;23:e12475. doi: 10.1111/hel.12475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chey WD, Leontiadis GI, Howden CW, Moss SF. ACG Clinical Guideline: Treatment of Helicobacter pylori Infection. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112:212–239. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2016.563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Malfertheiner P, Megraud F, Rokkas T, Gisbert JP, Liou JM, Schulz C, Gasbarrini A, Hunt RH, Leja M, O’Morain C, Rugge M, Suerbaum S, Tilg H, Sugano K, El-Omar EM European Helicobacter and Microbiota Study group. Management of Helicobacter pylori infection: the Maastricht VI/Florence consensus report. Gut. 2022 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koroglu M, Ayvaz MA, Ozturk MA. The efficacy of bismuth quadruple therapy, sequential therapy, and hybrid therapy as a first-line regimen for Helicobacter pylori infection compared with standard triple therapy. Niger J Clin Pract. 2022;25:1535–1541. doi: 10.4103/njcp.njcp_89_22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Song Z, Suo B, Zhang L, Zhou L. Rabeprazole, Minocycline, Amoxicillin, and Bismuth as First-Line and Second-Line Regimens for Helicobacter pylori Eradication. Helicobacter. 2016;21:462–470. doi: 10.1111/hel.12313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cortés P, Nelson AD, Bi Y, Stancampiano FF, Murray LP, Pujalte GGA, Gomez V, Harris DM. Treatment Approach of Refractory Helicobacter pylori Infection: A Comprehensive Review. J Prim Care Community Health. 2021;12:21501327211014087. doi: 10.1177/21501327211014087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Graham DY, Fischbach L. Helicobacter pylori treatment in the era of increasing antibiotic resistance. Gut. 2010;59:1143–1153. doi: 10.1136/gut.2009.192757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li SY, Li J, Dong XH, Teng GG, Zhang W, Cheng H, Gao W, Dai Y, Zhang XH, Wang WH. The effect of previous eradication failure on antibiotic resistance of Helicobacter pylori: A retrospective study over 8 years in Beijing. Helicobacter. 2021;26:e12804. doi: 10.1111/hel.12804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bi H, Chen X, Chen Y, Zhao X, Wang S, Wang J, Lyu T, Han S, Lin T, Li M, Yuan D, Liu J, Shi Y. Efficacy and safety of high-dose esomeprazole-amoxicillin dual therapy for Helicobacter pylori rescue treatment: a multicenter, prospective, randomized, controlled trial. Chin Med J (Engl) 2022;135:1707–1715. doi: 10.1097/CM9.0000000000002289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guan JL, Hu YL, An P, He Q, Long H, Zhou L, Chen ZF, Xiong JG, Wu SS, Ding XW, Luo HS, Li PY. Comparison of high-dose dual therapy with bismuth-containing quadruple therapy in Helicobacter pylori-infected treatment-naive patients: An open-label, multicenter, randomized controlled trial. Pharmacotherapy. 2022;42:224–232. doi: 10.1002/phar.2662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sakurai Y, Mori Y, Okamoto H, Nishimura A, Komura E, Araki T, Shiramoto M. Acid-inhibitory effects of vonoprazan 20 mg compared with esomeprazole 20 mg or rabeprazole 10 mg in healthy adult male subjects--a randomised open-label cross-over study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;42:719–730. doi: 10.1111/apt.13325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zuberi BF, Ali FS, Rasheed T, Bader N, Hussain SM, Saleem A. Comparison of Vonoprazan and Amoxicillin Dual Therapy with Standard Triple Therapy with Proton Pump Inhibitor for Helicobacter Pylori eradication: A Randomized Control Trial. Pak J Med Sci. 2022;38:965–969. doi: 10.12669/pjms.38.4.5436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chey WD, Mégraud F, Laine L, López LJ, Hunt BJ, Howden CW. Vonoprazan Triple and Dual Therapy for Helicobacter pylori Infection in the United States and Europe: Randomized Clinical Trial. Gastroenterology. 2022;163:608–619. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2022.05.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Suzuki S, Gotoda T, Kusano C, Ikehara H, Ichijima R, Ohyauchi M, Ito H, Kawamura M, Ogata Y, Ohtaka M, Nakahara M, Kawabe K. Seven-day vonoprazan and low-dose amoxicillin dual therapy as first-line Helicobacter pylori treatment: a multicentre randomised trial in Japan. Gut. 2020;69:1019–1026. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2019-319954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gotoda T, Kusano C, Suzuki S, Horii T, Ichijima R, Ikehara H. Clinical impact of vonoprazan-based dual therapy with amoxicillin for H. pylori infection in a treatment-naïve cohort of junior high school students in Japan. J Gastroenterol. 2020;55:969–976. doi: 10.1007/s00535-020-01709-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gao W, Teng G, Wang C, Xu Y, Li Y, Cheng H. Eradication rate and safety of a "simplified rescue therapy": 14-day vonoprazan and amoxicillin dual regimen as rescue therapy on treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection previously failed in eradication: A real-world, retrospective clinical study in China. Helicobacter. 2022;27:e12918. doi: 10.1111/hel.12918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhou BG, Chen LX, Li B, Wan LY, Ai YW. Saccharomyces boulardii as an adjuvant therapy for Helicobacter pylori eradication: A systematic review and meta-analysis with trial sequential analysis. Helicobacter. 2019;24:e12651. doi: 10.1111/hel.12651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang JW, Hsu PI, Lin MH, Kao J, Tsay FW, Wu IT, Shie CB, Wu DC. The efficacy of culture-guided versus empirical therapy with high-dose proton pump inhibitor as third-line treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection: A real-world clinical experience. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;37:1928–1934. doi: 10.1111/jgh.15942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shang H, Wang YS, Shen ZY. National Guide to Clinical Laboratory Procedures. 4th ed. Beijing: People’s medical Publishing House, 2014: 574-628. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saito Y, Konno K, Sato M, Nakano M, Kato Y, Saito H, Serizawa H. Vonoprazan-Based Third-Line Therapy Has a Higher Eradication Rate against Sitafloxacin-Resistant Helicobacter pylori. Cancers (Basel) 2019;11 doi: 10.3390/cancers11010116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gisbert JP. Empirical or susceptibility-guided treatment for Helicobacter pylori infection? Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2020;13:1756284820968736. doi: 10.1177/1756284820968736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sue S, Shibata W, Sasaki T, Kaneko H, Irie K, Kondo M, Maeda S. Randomized trial of vonoprazan-based versus proton-pump inhibitor-based third-line triple therapy with sitafloxacin for Helicobacter pylori. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;34:686–692. doi: 10.1111/jgh.14456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hirata Y, Yamada A, Niikura R, Shichijo S, Hayakawa Y, Koike K. Efficacy and safety of a new rifabutin-based triple therapy with vonoprazan for refractory Helicobacter pylori infection: A prospective single-arm study. Helicobacter. 2020;25:e12719. doi: 10.1111/hel.12719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Inokuchi K, Mori H, Matsuzaki J, Hirata K, Harada Y, Saito Y, Suzuki H, Kanai T, Masaoka T. Efficacy and safety of low-dose rifabutin-based 7-day triple therapy as a third- or later-line Helicobacter pylori eradication regimen. Helicobacter. 2022;27:e12900. doi: 10.1111/hel.12900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Graham DY, Lu H, Shiotani A. Vonoprazan-containing Helicobacter pylori triple therapies contribution to global antimicrobial resistance. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;36:1159–1163. doi: 10.1111/jgh.15252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McFarland LV. Systematic review and meta-analysis of Saccharomyces boulardii in adult patients. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:2202–2222. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i18.2202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sakarya S, Gunay N. Saccharomyces boulardii expresses neuraminidase activity selective for α2,3-linked sialic acid that decreases Helicobacter pylori adhesion to host cells. APMIS. 2014;122:941–950. doi: 10.1111/apm.12237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li H, Liang X, Chen Q, Zhang W, Lu H. Inappropriate treatment in Helicobacter pylori eradication failure: a retrospective study. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2018;53:130–133. doi: 10.1080/00365521.2017.1413132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Addolorato G, Mirijello A, D’Angelo C, Leggio L, Ferrulli A, Abenavoli L, Vonghia L, Cardone S, Leso V, Cossari A, Capristo E, Gasbarrini G. State and trait anxiety and depression in patients affected by gastrointestinal diseases: psychometric evaluation of 1641 patients referred to an internal medicine outpatient setting. Int J Clin Pract. 2008;62:1063–1069. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2008.01763.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.