Abstract

Background:

Green tea (Camellia sinensis) mouth rinse is found effective in reducing periodontitis. However, studies evaluating the effectiveness of green tea extracts in reducing oral halitosis and tongue coating on Indian population were scanty.

Objective:

The objective of this study was to evaluate the effectiveness of green tea-based mouth rinse in comparison with 0.2% chlorhexidine gluconate mouth rinse in reducing dental plaque, tongue coating, and halitosis among human volunteers.

Materials and Methods:

This was a parallel-arm double-blind randomized controlled trial conducted in two residential hostels in Mysuru city over 21 days. 90 adult participants were recruited and randomized into three groups: Group A: mouth rinse containing saline, Group B: 5% C. sinensis mouth rinse, and Group C: 0.2% chlorhexidine diluted to with equal quantity of water. Preintervention prophylaxis was done; tongue coating and oral halitosis scores were recorded and compared between the groups at baseline and after 21 days.

Results:

The mean plaque buildup at postintervention was highest in Group 1 (2.45 ± 0.38) followed by Group 3 (1.18 ± 0.12) and Group 2 (1.08 ± 0.11) in the descending order. The mean oral halitosis score was highest in Group 1 (3.00 ± 0.79) followed by Group 3 (1.53 ± 0.50) and Group 2 (1.50 ± 0.50) in the descending order. The mean tongue coating score was highest in Group 1 (1.17 ± 0.47) followed by Group 2 (0.75 ± 0.36) and Group 3 (0.69 ± 0.34) in the descending order.

Conclusion:

Five percent C. sinensis mouth rinse is as effective as commercially available 0.2% chlorhexidine mouthwash in reducing plaque deposition, tongue coating, and oral halitosis.

Keywords: Camellia sinensis, green tea mouth rinse, halitosis, plaque control, tongue coating

INTRODUCTION

Dental plaque is one of the major etiological factors for gingivitis, periodontitis, and oral halitosis.[1,2] Due to various other reasons, such as tooth anatomy, occlusion, dexterity of the patient, and wrong technique of brushing and flossing, plaque cannot be completely removed from all the surfaces. This necessitates adjunctive methods of plaque control such as chemical methods.[1] Various solutions have been in use for chemical control of plaque. These include saltwater, chlorhexidine, other alcohol based mouthwashes. More recently, natural additives such as green tea have been tried. Due to its favorable properties, such as antibacterial activity, relative low toxicity, affinity to oral mucosa, and its substantivity effect, it is considered the gold standard in chemical plaque control. However, it has some disadvantages such as altered taste sensation, staining of teeth, and scalding of oral mucosa.[3,4]

Among the various natural substances tried in mouthwashes, green tea is attracting special interest due to favorable properties such as anti-collagenase activity, cysteine protease activity against Porphyromonas gingivalis, and anti-inflammatory and anti-mutagenic properties.[5-7] It contains polyphenols that are bactericidal and also prevent the adhesion of P. gingivalis to oral epithelia.[8] It has also been shown that these polyphenols have an anti-inflammatory effect by decreasing production of interleukin (IL)-6 and IL-8.[9]

Oral halitosis is mainly caused by volatile sulfur compounds that are a by-product of metabolism of substrate by plaque bacteria.[10] While there are studies proving the beneficial effect of green tea-based mouthwash on gingivitis and periodontitis,[2-4,6] and other studies proving its efficacy in improving halitosis,[8-14] literature evaluating the effectiveness of green tea mouth rinse in reducing oral halitosis, tongue coating, and plaque accumulation in the same study among Indian population was scanty. In this background, the present study evaluated the effectiveness of green tea mouth rinse on oral halitosis, tongue coating, and plaque accumulation in comparison with 0.2% chlorhexidine mouth rinse.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This was a parallel-arm double-blinded randomized controlled trial conducted in two residential hostels in Mysuru city over a period of 21 days. The study protocol was approved by the Institution Ethics Committee. Permission was obtained to conduct the study from the heads of the college hostels. The trial was registered with the Clinical Trials Registry of India with trial registration number CTRI/2021/09/036113. Written informed consent was obtained from students participating in the study, after informing them about the research protocol.

The sample size was estimated using nMaster software. It was computed to be 25 per group for estimating mean difference of 0.25 between the groups, at 5% level of significance, and 80% power. It was rounded off to 30 per group, to compensate for any dropouts. Participant recruitment was based on the following inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Adults aged between 18 and 60 years, who had a minimum of 20 natural teeth, who were free from systemic diseases and physical and mental disabilities, and willing to offer informed consent were included in the study.

Participants with gross oral defects that interfered with chewing, history of the use of antibiotics in the last 3 months, any deleterious and/or parafunctional habits, and who had removable/fixed appliances were excluded from the study. A total of 90 adult participants fulfilling above eligibility criteria were recruited for the study.

The primary investigator was trained in the use of the indices by Author 2 over 2 weeks. The calibration was undertaken on a group of ten participants using test–retest method. The Cronbach’s alpha for Turesky’s modification of the Quigley Hein Plaque Index, Winkel Tongue Coating Index, (WTCI), and Rosenberg Scale for Oral Halitosis were 0.87, 0.92, and 0.89, respectively.

Fresh green tea leaves were procured from a tea estate and then ground into a coarse powder form. The green tea extract was prepared through maceration.[15-20]

For every 100 ml of green tea mouth rinse, we used 2 g of green tea extract, 4 mL of Tween 80 oil, 0.3 mL of peppermint oil, 150 mg of methyl paraben, 5 g of mannitol, and 500 mg of poloxamer.

The following steps were used for preparation of green tea mouth rinse:

2 g of green tea extract was taken in a glass mortar pestle and grinded into a fine powder

2 mL of Tween 80 oil was added followed by trituration

0.3 mL of peppermint oil was added followed by trituration

The remaining Tween 80 oil was added followed by trituration.

500 mg of poloxamer was added followed by trituration

100 mL of Millipore water was taken

150 mg of methyl paraben and 5 g of mannitol were added to the Millipore water

The mixture was added to the triturated paste in stages and mixed gently

The resultant mixture was double filtered using filter paper and stored in plastic bottles.

The placebo was made using the exact same ingredients of the exact same weight as that of green tea mouth rinse, but, instead of green tea extract, a blue-coloring dye agent was used. The coded mouth rinse bottles are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The coded mouth rinse bottles used in the study

A pilot study was conducted on a group of five participants each, before the main randomized trial was undertaken, to evaluate the feasibility and operational efficiency of protocol. The protocol was found feasible.

Baseline examination was carried out by the principal investigator. The plaque score was assessed using Turesky’s modification of the Quigley Hein Plaque Index.[21] Tongue coating was measured using WTCI.[22] The tongue was divided into six segments. Each segment was scored using the criteria – 0: no coating on the tongue, 1: light coating found on tongue, and 2: heavy tongue coating found on tongue. The highest score among the six segments was taken as the score for the participant. Oral halitosis was measured using the Rosenberg Scale.[23] Oral halitosis was assessed by one trained and calibrated investigator using the criteria – 0: absence of odor, 1: questionable odor, 2: slight malodor, 3: moderate malodor, 4: strong malodor, and 5: severe malodor. Each participant was informed to exhale through the mouth, using moderate force, into a 10-cm long, hollow, Teflon pipe, attached with a screen, for 2–3 s. The participants were instructed to tightly hold one end of the pipe, so that there was no scope for breath to mix with room air and then blow into the pipe within its diameter. At the same time, the investigator assessed breath from the other end of pipe keeping the nose close to the screen. The procedure was repeated three times before a final score was recorded for each participant.

Preintervention prophylaxis (scaling and polishing) was carried out among eligible participants using a portable dental chair and ultrasonic scaler (Cavitron Select SPS 30K Ultrasonic Scaler, Dentsply, USA). The plaque score was brought to zero.

Eligible ninety participants were randomly assigned to three different categories using block randomization method by the coordinator. Group allocation information was concealed from participants and investigator involved in clinical data collection to ensure blinding. Mouth rinse bottles were coded with labels A, B, and C without disclosing the identity of the mouth rinse bottles.

Each participant was given an oral hygiene kit containing a toothbrush, a toothpaste, and a 200-ml coded mouth rinse bottle.

Group 1: Mouth rinse containing saline

Group 2: 5% Camellia sinensis mouth rinse

Group 3: 0.2% Chlorhexidine diluted to with equal quantity of water.

Participants were requested to use 10 ml of the assigned mouth rinse twice a day (once in the morning and once in the night) for about a minute. They were requested to refrain from using any other oral hygiene aid during the study period. Directions for the use of mouth rinse were specified on bottles along with contact details of investigator to report any adverse events.

Participants were requested to get mouth rinse bottles replaced after 7 days which enabled us to check compliance besides providing the mouth rinses which were freshly prepared.

Postintervention evaluation for clinical parameters was done 21 days after the intervention by the principal investigator using the indices specified earlier.

After the study, all the participants were informed about the group they belonged to, and queries were clarified (debriefing). They were also asked about any adverse effects they encountered while using the mouthwashes.

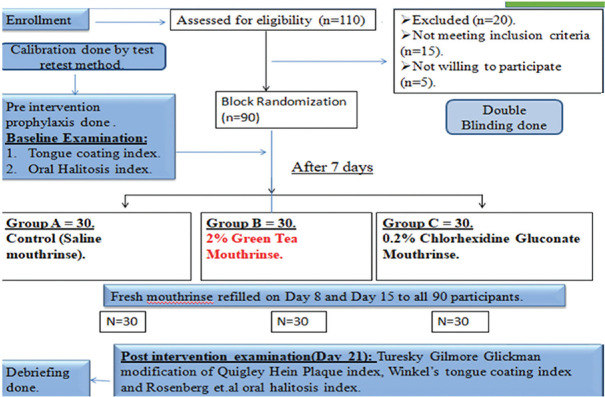

The Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials flow diagram of the entire experiment is presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

CONSORT flow diagram of the experiment. CONSORT – Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials. n – Number of participants; N – Sample size

The data were entered into Microsoft Excel, and analysis was done using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS, IBM, Chicago, USA) software version 24. The difference in the mean plaque buildup, tongue coating, and oral halitosis score between different groups at baseline and postintervention was compared using one-way analysis of variance and Tukey’s post hoc test. The difference in the mean tongue coating and oral halitosis score between baseline and postintervention in each group was compared using paired samples t-test. The distribution of participants reporting adverse drug reactions in different groups was compared using Pearson’s Chi-square test. The statistical significance was fixed at 0.05.

RESULTS

A total of 90 participants took part in the study. All study participants were available during the follow-up with no dropouts. The age and gender distribution of the study participants is denoted in Table 1. Seventy-six (84.4%) participants were female and 14 (25.6%) were male with no significant difference in the gender distribution between different intervention groups (P = 0.553) [Table 1].

Table 1.

Age and gender distribution of study participants in three different groups

| Groups | <25 years | >25 years | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

||||

| Males, n (%) | Females, n (%) | Males, n (%) | Females, n (%) | Males, n (%) | Females, n (%) | |

| Group 1 | 5 (21.7) | 18 (78.5) | 0 | 7 (100) | 5 (16.7) | 25 (85.3) |

| Group 2 | 0 (0.1) | 20 (100) | 3 (30.0) | 7 (70) | 3 (10.0) | 27 (90) |

| Group 3 | 3 (15) | 17 (85) | 3 (30.0) | 7 (70) | 6 (20) | 24 (80) |

| Total | 8 (12.7) | 55 (87.3) | 6 (22.2) | 21 (77.8) | 14 (15.6) | 76 (84.4) |

| Statistical inference (χ2, df, P) | 4.700; 2; 0.095 | 2.700; 2; 0.259 | 1.184; 2; 0.553 | |||

P<0.05 was considered statistically significant. df – Degree of freedom; n – Frequency; χ2 – Chi square value; P – P value

The plaque score was brought to zero before intervention, and hence, the baseline comparison for plaque was not made between the groups. There was no significant difference in the mean oral halitosis score (P = 0.840) [Table 2] and the mean tongue coating score (P = 0.555) [Table 2] between the participants in three intervention groups at baseline.

Table 2.

Comparison of mean oral halitosis and tongue coating scores at baseline between the three groups

| Groups | Mean±SD | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Oral halitosis | Tongue coating | |

| Group 1 (G1) | 3.30±0.83 | 1.44±0.52 |

| Group 2 (G2) | 3.10±1.49 | 1.53±0.41 |

| Group 3 (G3) | 3.17±1.55 | 1.40±0.50 |

| Total | 3.19±1.32 | 1.45±0.48 |

| Statistical inference | ||

| F | 0.174 | 0.593 |

| df | 2 | 2 |

| P | 0.840 | 0.555 |

| Post hoc comparison | ||

| G1 versus G2 | 0.831 | 0.732 |

| G1 versus G3 | 0.921 | 0.950 |

| G2 versus G3 | 0.980 | 0.543 |

P<0.05 was considered statistically significant. SD – Standard deviation; df – Degree of freedom; F – F statistic; P – P value.

The mean plaque buildup at postintervention was highest in Group 1 (2.45 ± 0.38) followed by Group 3 (1.18 ± 0.12) and Group 2 (1.08 ± 0.11) in the descending order. The difference was statistically significant (P ≤ 0.001) [Table 3]. However, the post hoc analysis found a significant difference between Group 1 and others with no significant difference between Group 2 and Group 3 [Table 3]. The mean oral halitosis score was highest in Group 1 (3.00 ± 0.79) followed by Group 3 (1.53 ± 0.50) and Group 2 (1.50 ± 0.50) in the descending order. The difference was statistically significant (P ≤ 0.001) [Table 3]. However, the post hoc analysis found a significant difference between Group 1 and others with no significant difference between Group 2 and Group 3 [Table 3]. The mean tongue coating score was highest in Group 1 (1.17 ± 0.47) followed by Group 2 (0.75 ± 0.36) and Group 3 (0.69 ± 0.34) in the descending order. The difference was statistically significant (P ≤ 0.001) [Table 3]. However, the post hoc analysis found a significant difference between Group 1 and others with no significant difference between Group 2 and Group 3 [Table 3].

Table 3.

Comparison of mean plaque buildup, oral halitosis, and tongue coating scores at postintervention between the three groups

| Groups | Mean±SD | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Plaque buildup | Oral halitosis | Tongue coating | |

| Group 1 (G1) | 2.45±0.38 | 3.00±0.79 | 1.17±0.47 |

| Group 2 (G2) | 1.08±0.11 | 1.50±0.50 | 0.75±0.36 |

| Group 3 (G3) | 1.18±0.12 | 1.53±0.50 | 0.69±0.34 |

| Total | 1.57±0.67 | 2.01±0.93 | 0.87±0.44 |

| Statistical inference | |||

| F | 298.73 | 58.0 | 12.877 |

| df | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| P | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Post hoc comparison | |||

| G1 versus G2 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| G1 versus G3 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| G2 versus G3 | 0.976 | 0.976 | 0.846 |

P<0.05 was considered statistically significant. SD – Standard deviation, df – Degree of freedom; F – F statistic; P – P value

There was a significant decrease in the mean oral halitosis score and tongue coating score at postintervention compared to baseline scores in each group. The difference was more pronounced in Groups 2 and 3 compared to that observed in Group 1 [Table 4]. There was no significant difference in the distribution of study participants with regard to adverse effects [Table 5].

Table 4.

Comparison of mean oral halitosis score between baseline and postintervention in each group

| Groups | Mean±SD | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Oral halitosis | Tongue coating | |||||

|

|

|

|||||

| Preintervention | Postintervention | Statistical inference (t, df, P) | Preintervention | Postintervention | Statistical inference | |

| Group 1 | 3.30±0.83 | 3.00±0.788 | 3.071, 29, 0.005 | 1.44±0.52 | 1.173±0.47 | 4.701, 29, <0.001 |

| Group 2 | 3.10±1.49 | 1.50±0.509 | 7.738, 29, <0.001 | 1.53±0.41 | 0.753±0.37 | 11.240, 29, <0.001 |

| Group 3 | 3.17±1.55 | 1.53±0.507 | 7.527, 29, <0.001 | 1.39±0.50 | 0.696±0.34 | 14.279, 29, <0.001 |

P<0.05 was considered statistically significant. SD – Standard deviation; df – Degree of freedom; t – t-value; P – P value

Table 5.

Distribution of adverse effects in different intervention groups

| Groups | Adverse effect (nausea), n (%) | Adverse effect (bad smell/odor), n (%) | Total, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1 | 1 (25) | 0 | 1 (16.7) |

| Group 2 | 3 (75) | 2 (100) | 5 (83.3) |

| Group 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 4 (100) | 2 (100) | 6 (100) |

| Statistical inference (χ2, df, P) | 0.600, 1, 0.439 | ||

P<0.05 was considered statistically significant. n – Frequency; df – Degree of freedom; χ2 – Chi square value; P – P value

DISCUSSION

In the field of dental public health, it is common to see many sections of society with individuals who are not competent to perform toothbrushing as per the taught methods. This could be due to various reasons such as illiteracy, lack of motor skills owing to underlying systemic diseases, or disorders.[24,25] Studies in the past have shown a favorable effect of green tea in plaque control[2-4,6] and halitosis.[8-10] However, studies on the effectiveness of green tea-based mouth rinse on halitosis, tongue coating, and plaque levels in the same study sample minimize the role of confounding factors while providing more realistic results.

At baseline, scores for oral halitosis and tongue coating were similar among the participants, i.e. no statistically significant difference between the different values noted. It could be inferred from these findings that the oral hygiene methods of the study population were similar regardless of which group they were assigned to. This ruled out the possibility of oral hygiene methods acting as potential confounders.

Postintervention oral halitosis scores were highest in Group 1 followed by Groups 3 and 2 [Table 3]. These differences were statistically significant (P < 0.001) [Table 3]. It can be inferred from these findings that saline mouth rinse was least effective in reducing oral halitosis, while green tea and chlorhexidine mouth rinses were equally effective similar to the results of other studies.[8,9,26]

The postintervention tongue coating scores were highest in Group 1 followed by Groups 2 and 3. The difference in the mean scores between the three groups was statistically significant (P < 0.001) [Table 3]. The effectiveness of green tea-based mouth rinse in reducing tongue coating was comparable to that produced by chlorhexidine mouth rinse. Saline was not effective in comparison with green tea-based mouth rinse and chlorhexidine mouth rinse. We could not find any human studies which assessed the effectiveness of a green tea mouth rinse on tongue coating per se, but we did find a few studies that assessed in vitro, the effect of green tea-based mouthwash on common microorganisms found in tongue coating such as Solobacterium moorei.[8] A study by Morin MP et al, found the green tea extract and epigallocatechin gallate to inhibit the growth of S. moorei at Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) values of 500 µg/ml and 250 µg/ml, respectively.[8]

The effectiveness of green tea-based mouth rinse could be due to the various phytochemical constituents present in green tea extract. It contains polyphenols, specifically the four major catechins which are epicatechin gallate, epigallocatechin gallate, epicatechin, and epigallocatechin.[8] These catechins have been shown to be bactericidal and also prevent the adhesion of P. gingivalis to oral epithelia. It has also been shown that the polyphenols in green tea can have an anti-inflammatory effect by decreasing production of IL-6 and IL-8.[9]

The postintervention plaque buildup scores were highest in Group 1 followed by Groups 3 and 2. The differences were statistically significant between the three groups (P = 0.000) [Table 3]. This shows that the effectiveness of green tea-based mouth rinse and chlorhexidine was similar. The effectiveness of green tea in reducing plaque score was similar to the results of other studies.[3,4,26-28] For example, in the study by Kaur et al.,[4] they reported no statistically significant difference in mean plaque scores between chlorhexidine and green tea catechin mouthwash. They reported scores for posterior teeth for green tea as 2.8633 ± 0.32535 and for chlorhexidine as 2.9034 ± 0.33646 (P > 0.05).

The postintervention oral halitosis scores of the participants in all three groups decreased significantly. These results were statistically significant [Table 4]. Similarly, when we assessed the pre- and postintervention tongue coating scores, overall, a statistically significant reduction was noted in all three groups, including the saline group. We found a reduction in oral halitosis scores and tongue coating scores in the control group as well. This could be attributed to increased attention on oral hygiene practice by all study participants during the study period. The participation in a study where the participants were informed about the follow-up examination which was supposed to be undertaken after 3 weeks following intervention would have motivated them to improve their oral hygiene practices. Besides, the uniform guidelines pertaining to the use of mouth rinse as well as the distribution of oral hygiene aids along with demonstration of oral hygiene practices would have contributed to improvements in the scores in the group using saline as well.

Although the mouth rinses for Groups 2 and 3 were prepared by the investigator herself under supervision of an expert in a pharmacy college, the possibility of some adverse effects in the form of bad odor and nausea was anticipated. The prevalence of these two adverse effects (nausea and bad smell) was elicited from the participants. Nausea was reported by one participant in Group 1 (saline), three participants in Group 2 (green tea mouthwash), and none in Group 3 (commercially available chlorhexidine) with no significant difference in the prevalence of these adverse effects between the three groups. Bad odor was reported by two participants in Group 2 with no significant difference between the groups. The students in the hostel lived together and we assume the possibility of reporting bias among the participants since the students might have discussed among themselves about the adverse effects before reporting them to the investigator.

The study evaluated the effectiveness of a novel, indigenously prepared green tea mouth rinse in reducing plaque buildup, oral halitosis, and tongue coating. Although some studies have evaluated the effectiveness of green tea rinse on plaque buildup, this was the first of its kind study on human participants evaluating the effectiveness of green tea mouth rinse on oral halitosis and tongue coating.

The objective assessment of oral halitosis using gas chromatography would have validated the results obtained through organoleptic scale. We could not undertake gas chromatography in the present study owing to some logistic difficulties.

CONCLUSION

Under the limitations of the study, it can be concluded that 5% C. sinensis mouth rinse is as effective as commercially available 0.2% chlorhexidine mouth rinse in reducing plaque scores, tongue coating, and oral halitosis. Larger sample size and long-term studies are recommended to validate the results of the present study. The long-term studies will help us in assessing the acceptability of this indigenously prepared mouth rinse while providing opportunity for evaluating the long-term side effects.

Financial support and sponsorship

The study was funded by ICMR vide MD19DEC-0083.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

We acknowledge the kind support extended by the participants, heads of institutions, and ICMR for their financial assistance for the project.

REFERENCES

- 1.Newman MG, Takei HH, Klokkevold PR, Carranza FA. Carranza's Clinical Periodontology. 12th ed. St Louis, Missouri: Eslevier/Saunders; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Deshmukh MA, Dodamani AS, Karibasappa G, Khairnar MR, Naik RG, Jadhav HC. Comparative evaluation of the efficacy of probiotic, herbal and chlorhexidine mouthwash on gingival health: A randomized clinical trial. J Clin Diagn Res. 2017;11:C13–6. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2017/23891.9462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Khobragade VR, Vishwakarma PY, Dodamani AS, Jain VM, Mali GV, Kshirsagar MM. Comparative evaluation of indigenous herbal mouthwash with 0.2% chlorhexidine gluconate mouthwash in prevention of plaque and gingivitis: A clinico-microbiological study. J Indian Assoc Public Health Dent. 2020;18:111–7. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaur H, Jain S, Kaur A. Comparative evaluation of the antiplaque effectiveness of green tea catechin mouthwash with chlorhexidine gluconate. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2014;18:178–82. doi: 10.4103/0972-124X.131320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Neturi RS, Srinivas R, Simha V, Sandya Sree Y, Chandrashekar T, Siva Kumar P. Effects of green tea on Streptococcus mutans counts –A randomised control trail. J Clin Diagn Res. 2014;8:C128–30. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2014/10963.5211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hoshi M, Aida J, Kusama T, Yamamoto T, Kiuchi S, Yamamoto T, et al. Is the association between green tea consumption and the number of remaining teeth affected by social networks?A cross-sectional study from the Japan gerontological evaluation study project. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:2052. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17062052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Okamoto M, Sugimoto A, Leung KP, Nakayama K, Kamaguchi A, Maeda N. Inhibitory effect of green tea catechins on cysteine proteinases in Porphyromonas gingivalis . Oral Microbiol Immunol. 2004;19:118–20. doi: 10.1046/j.0902-0055.2003.00112.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morin MP, Bedran TB, Fournier-Larente J, Haas B, Azelmat J, Grenier D. Green tea extract and its major constituent epigallocatechin-3-gallate inhibit growth and halitosis-related properties of Solobacterium moorei. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2015;15:48. doi: 10.1186/s12906-015-0557-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rassameemasmaung S, Phusudsawang P, Sangalungkarn V. Effect of green tea mouthwash on oral malodor. ISRN Prev Med. 2013;2013:975148. doi: 10.5402/2013/975148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krespi YP, Shrime MG, Kacker A. The relationship between oral malodor and volatile sulfur compound-producing bacteria . Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;135:671–6. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2005.09.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lodhia P, Yaegaki K, Khakbaznejad A, Imai T, Sato T, Tanaka T, et al. Effect of green tea on volatile sulfur compounds in mouth air. J Nutr Sci Vitaminol (Tokyo) 2008;54:89–94. doi: 10.3177/jnsv.54.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Higuchi T, Suzuki N, Nakaya S, Omagari S, Yoneda M, Hanioka T, et al. Effects of Lactobacillus salivarius WB21 combined with green tea catechins on dental caries, periodontitis, and oral malodor. Arch Oral Biol. 2019;98:243–7. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2018.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zeng QC, Wu AZ, Pika J. The effect of green tea extract on the removal of sulfur-containing oral malodor volatiles in vitro and its potential application in chewing gum. J Breath Res. 2010;4:036005. doi: 10.1088/1752-7155/4/3/036005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Farina VH, Lima AP, Balducci I, Brandão AA. Effects of the medicinal plants Curcuma zedoaria and Camellia sinensis on halitosis control. Braz Oral Res. 2012;26:523–9. doi: 10.1590/s1806-83242012005000022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ingle KP, Deshmukh AG, Padole DA, Dudhare MS, Moharil MP, Khelurkar VC. Phytochemicals: Extraction methods, identification, and detection of bioactive compounds from plant extracts. J Pharmacogn Phytochem. 2017;6:32–6. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Azwanida NN. A review on the extraction methods use in medicinal plants, principle, strength, and limitation. Med Aromat Plants. 2015;4:196. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pandey A, Tripathi S. Concept of standardization, extraction, and pre-phytochemical screening strategies for herbal drug. J Pharmacogn Phytochem. 2014;2:115–9. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Doughari JH. Phytochemicals: Extraction methods, basic structures, and mode of action as potential chemotherapeutic agents, phytochemicals –A global perspective of their role in nutrition and health. In: Venketeshwer R, editor. Global Perspective of Their Role in Nutrition and Health. InTech. University of toranto; Canada: 2012. [[Last accessed on 2022 Sep 12]]. Available from:https://www.intechope n.com/books/878 . [Google Scholar]

- 19.Majekodunmi SO. Review of extraction of medicinal plants for pharmaceutical research. Merit Res J Med Med Sci. 2015;3:521–7. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ujang ZB, Subramaniam T, Diah MM, Wahid HB, Abdullah BB, Rashid AA, et al. Bioguided fractionation and purification of natural bioactive obtained from Alpinia conchigera water extract with melanin inhibition activity. J Biomater Nanobiotechnol. 2013;4:265–72. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Turesky S, Gilmore ND, Glickman I. Reduced plaque formation by the chloromethyl analogue of victamine C. J Periodontol. 1970;41:41–3. doi: 10.1902/jop.1970.41.41.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Winkel EG, Roldán S, Van Winkelhoff AJ, Herrera D, Sanz M. Clinical effects of a new mouthrinse containing chlorhexidine, cetylpyridinium chloride and zinc-lactate on oral halitosis. A dual-center, double-blind placebo-controlled study. J Clin Periodontol. 2003;30:300–6. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.2003.00342.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rosenberg M, Kulkarni GV, Bosy A, McCulloch CA. Reproducibility and sensitivity of oral malodor measurements with a portable sulphide monitor. J Dent Res. 1991;70:1436–40. doi: 10.1177/00220345910700110801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thomas A, Thakur SR, Shetty SB. Anti-microbial efficacy of green tea and chlorhexidine mouth rinses against Streptococcus mutans, Lactobacilli spp. and Candida albicans in children with severe early childhood caries: A randomized clinical study. J Indian Soc Pedod Prev Dent. 2016;34:65–70. doi: 10.4103/0970-4388.175518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sinija VR, Mishra HN. Green tea: Health benefits. J Nutr Environ Med. 2009;17:232–42. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Priya BM, Anitha V, Shanmugam M, Ashwath B, Sylva SD, Vigneshwari SK. Efficacy of chlorhexidine and green tea mouthwashes in the management of dental plaque-induced gingivitis: A comparative clinical study. Contemp Clin Dent. 2015;6:505–9. doi: 10.4103/0976-237X.169845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jenabian N, Moghadamnia AA, Karami E, Mir A PB. The effect of Camellia sinensis (green tea) mouthwash on plaque-induced gingivitis: A single-blinded randomized controlled clinical trial. Daru. 2012;20:39. doi: 10.1186/2008-2231-20-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goyal AK, Bhat M, Sharma M, Garg M, Khairwa A, Garg R. Effect of green tea mouth rinse on Streptococcus mutans in plaque and saliva in children: An in vivo study. J Indian Soc Pedod Prev Dent. 2017;35:41–6. doi: 10.4103/0970-4388.199227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]