Abstract

Objective:

The current study used the family stress model to test the mechanisms by which economic insecurity contributes to mothers’ and fathers’ mental health and couples’ relationship functioning.

Background:

Although low household income has been a focus of poverty research, material hardship—defined as everyday challenges related to making ends meet including difficulties paying for housing, utilities, food, or medical care—is common among American families.

Methods:

Participants were from the Building Strong Families project. Couples were racially diverse (43.52% Black; 28.88% Latinx; 17.29% White; 10.31% Other) and living with low income (N = 2,794). Economic insecurity included income poverty and material hardship. Bayesian mediation analysis was employed, taking advantage of the prior evidence base of the family stress model.

Results:

Material hardship, but not income poverty, predicted higher levels of both maternal and paternal depressive symptoms. Only paternal depressive symptoms were linked with higher levels of destructive interparental conflict (i.e., moderate verbal aggression couples use that could be harmful to the partner relationship). Mediation analysis confirmed that material hardship operated primarily through paternal depressive symptoms in its association with destructive interparental conflict.

Conclusion:

The economic stress of meeting the daily material needs of the family sets the stage for parental mental health problems that carry over to destructive interparental conflict, especially through paternal depressive symptoms.

Implications:

Family-strengthening programs may want to consider interventions to address material hardship (e.g., comprehensive needs assessments, connections to community-based resources, parents’ employment training) as part of their efforts to address parental mental health and couples’ destructive conflict behaviors.

Keywords: Bayesian statistics, Building Strong Families project, destructive interparental conflict, family stress model, material hardship, parental depressive symptoms

In the United States, it is estimated that 6.5 million families live in poverty (U.S. Census Bureau, 2020). In 2020, federal poverty guidelines established the poverty threshold of $26,200 for a family of four (e.g., two parents and two children; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2020). In families with low income, approximately 44% of the children (the largest proportion of children under age 18 years) were young children below the ages of 3 years (Koball & Jiang, 2018). The deleterious effects of poverty on families are well documented and include hardships with purchasing everyday goods, parents’ deteriorating mental health, and destructive interparental conflict (i.e., moderate verbal aggression couples use that could be harmful to the partner relationship)—all of which contribute to poor outcomes for children’s development (Brooks-Gunn & Duncan, 1997; Evans, 2004). Research suggests that poverty operates through specific family processes (Conger et al., 1994; McLoyd, 1990; Parke et al., 2004). For example, adverse economic conditions have shown to be linked with more economic pressure felt by parents, which in turn leads to decreased parental mental health that contributes to poor relationship quality between parents (Conger et al., 1994).

Although low household income has been a focus of poverty research, material hardship is common among American families. Most families with low income (70%) report experiencing material hardship defined as difficulties paying for housing, utilities, or medical care in the past year (Karpman et al., 2018a). Other terms such as economic hardship, economic pressure, and economic cutbacks have similar definitions as material hardship. That said, there is currently a lack of consensus surrounding the definition and measures used for material hardship (Heflin et al., 2009). To be consistent with prior literature on material hardship (e.g., Gershoff et al., 2007; Ouellette et al., 2004; Shelleby, 2018), we use the term material hardship throughout the current study. Building on the family stress model (FSM; Conger et al., 1994), the current study examined links between economic insecurity (operationalized as income poverty and material hardship), parental depressive symptoms, and destructive interparental conflict in a large and racially diverse sample of mothers and fathers with low income.

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK: THE FAMILY STRESS MODEL

The FSM was developed to understand the impact on families of economic insecurity caused by the Great Farm Crisis in the 1980s. The FSM posits that negative economic conditions, such as low family income, can lead to higher levels of economic pressure mothers and fathers experience, which then are associated with higher levels of depressive mood for both parents. This elevated parental depressive mood then leads to relationship strain in the form of higher levels of interparental conflict, which subsequently is associated with less involved or nurturant parenting that ultimately leads to children’s maladjustments (Conger et al., 1992). Economic pressure is also thought to exert a direct and negative impact on interparental relationship quality (Conger et al., 2002). Most early FSM studies were conducted with White farming families in rural Iowa (Conger et al., 1990, 1992, 1993, 1994). Such research provided support for the tenets of the FSM, demonstrating that adverse economic conditions are linked to poor child outcomes through its effects on parents’ psychological functioning, relationship quality, and parenting behaviors. Some of these early studies also demonstrated that a positive parent–child relationship served as a protective factor (Conger et al., 1990, 1994).

The FSM has been expanded to examine the processes that link poverty to relationship quality, parenting, and child outcomes among Black and Latinx families in urban contexts and among families that experience economic stress (Cassells & Evans, 2017; Conger & Donnellan, 2007; Gard et al., 2020; Masarik & Conger, 2017; McLoyd, 1990; Parke et al., 2004; Simons et al., 2016). For example, using a community-based sample of two-parent Black families with low income, Simons et al. (2016) showed that economic stress (i.e., low income and negative financial events) was linked with higher levels of depressed mood for both parents, which then were linked with higher levels of poor relationship quality between the parents. Together, these studies show that the core tenets of the FSM apply widely across diverse populations (for a review of relevant studies, see Masarik & Conger, 2017). Of interest to the current study, we tested the FSM’s proposed associations between low family income, economic pressure in the form of material hardship, mothers’ and fathers’ depressive symptoms, and destructive interparental conflict in a large sample of racially diverse mothers and fathers from low-income contexts.

ECONOMIC INSECURITY AND PARENTAL DEPRESSIVE SYMPTOMS

One of the most robust findings from research on the FSM is evidence demonstrating that economic disadvantage and strain are linked to mothers’ and fathers’ depressed mood. Early FSM studies with rural White families showed that economic pressure (e.g., having difficulty paying bills each month) arising from families’ income loss due to the farming crisis was associated with higher levels of both maternal and paternal depressive symptoms (Conger et al., 1992, 1993, 1994). As noted earlier, subsequent research with more diverse populations have replicated these results (Gard et al., 2020; Masarik & Conger, 2017; Parke et al., 2004; Shelleby, 2018; Williams & Cheadle, 2016). For example, Shelleby (2018) used maternal data from the Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study and found that lower family income (at the time of children’s births and when they were 1 year old) was linked with higher levels of maternal depressive symptoms when the children were 3 years old and that this association was mediated by mothers’ reports of material hardship (e.g., could not pay gas or electric bills, got evicted for not paying rent) when the children were 1 year old. Overall, the mechanism linking low family income to poorer parental mental health via some level of material hardship seems to cross race and ethnicity, as well as geographic (urban or rural) boundaries (Gard et al., 2020; Masarik & Conger, 2017; Parke et al., 2004; Shelleby, 2018).

Despite the wide application of the FSM, studies testing the theoretical model that include both mothers and fathers—especially those from socioeconomically disadvantaged contexts—are still limited (exceptions include Curran et al., 2021; Parke et al., 2004). Parke et al. (2004), who used an urban sample of Mexican American mothers and fathers, showed that family income was linked with less economic pressure (e.g., have difficulty paying bills each month) as perceived by both mothers and fathers. Economic pressure was subsequently linked with higher levels of maternal and paternal depressive symptoms. A more recent example is Curran et al. (2021), in which the researchers used both mothers’ and fathers’ data from the Building Strong Families (BSF) project and found no relations between material hardship at 15 months and parental depressive symptoms at 36 months but found that maternal depressive symptoms at 15 months were linked with higher levels of material hardship at 36 months. The researchers noted that these findings were unexpected and opposite of what they hypothesized based on the FSM. Their explanation was that mothers may experience additional burdens, such as childcare, that further contribute to their depressive symptoms predicting material hardship (Curran et al., 2021).

Importantly, Curran et al. (2021) were primarily interested in testing the bidirectionality between material hardship and parental depressive symptoms among other variables. As such, testing specific mechanisms involving parental depressive symptoms as mediators was, rightly so, not the focus of the study. There is a need to apply the FSM in testing the mechanisms underlying the links between material hardship and destructive interparental conflict. This is a gap the current study fills by using data from both mothers and fathers from low-income contexts to test mediating pathways between material hardship and destructive interparental conflict via mothers’ and fathers’ depressive symptoms as proposed by the FSM. Together, prior research suggests that low family income may be adversely linked with mothers’ and fathers’ mental health, possibly through material hardship, although additional research is needed to elucidate this mechanism among socioeconomically disadvantaged mothers and fathers, such as those in the BSF project.

ECONOMIC INSECURITY AND DESTRUCTIVE INTERPARENTAL CONFLICT VIA MOTHERS’ AND FATHERS’ DEPRESSIVE SYMPTOMS

Another key mechanism in the FSM is that economic insecurity is associated with poorer interparental relationship quality that arises from parents’ hostile behaviors or lack of warmth toward one another (Conger et al., 1990; Cummings & Davies, 2010). This mechanism within the FSM has been demonstrated with White rural families (Conger et al., 1990, 1992, 1993, 1994) and replicated in studies that use more racially and geographically diverse samples (Conger et al., 2002; Helms et al., 2014; Martin et al., 2019; O’Neal et al., 2015; Parke et al., 2004). Research suggests that economic insecurity may erode interparental relationship quality through its impact on parental depressive symptoms. Specifically, there is evidence to suggest that paternal depressive symptoms, which can take the form of irritability or hostility, may primarily be responsible for mediating the links between economic insecurity and poorer interparental relationship quality (Conger et al., 1990). For example, Conger et al. (1990) showed that economic pressure was indirectly linked with lower levels of relationship quality and higher levels of relationship instability by promoting hostile behaviors and reducing warm behaviors couples expressed to each other. Importantly, they found that these processes were more pronounced for men, whose hostile and irritable behaviors had a stronger relationship with financial difficulties than the behaviors of women (Conger et al., 1990), possibly suggesting the economic pressure fathers feel in fulfilling traditional breadwinner roles (Christiansen & Palkovitz, 2001; Edin & Nelson, 2013; Marsiglio & Roy, 2012).

Again, studies including the assessment of socioeconomically disadvantaged fathers’ and mothers’ perceptions of interparental relationship quality are generally limited. A few exceptions exist, including one prior BSF study that used maternal reports of destructive interparental conflict only (J. Y. Lee et al., 2021a) and another BSF study that used both parents’ reports of destructive interparental conflict (S. J. Lee et al., 2022). These studies aimed to apply an emotional security framework to BSF samples to elucidate pathways linking destructive interparental conflict and children’s behavioral problems and thus tested children’s emotional insecurity as key mediators. Said differently, there is a gap in our knowledge in terms of how economic insecurity, such as income poverty and material hardship, is linked with destructive interparental conflict via both mothers’ and fathers’ depressive symptoms as proposed by the FSM. The current study fills this gap by directly testing the FSM with a BSF sample and is timely given emerging research indicating increasing levels of economic hardship and mental health problems, including depression, among mothers and fathers during the COVID-19 pandemic (Cai et al., 2021; S. J. Lee et al., 2021, 2022; Patrick et al., 2020; Vazzano et al., 2022).

Regarding prior research using BSF data, Curran et al. (2021) notably employed a BSF sample and showed in their preliminary analyses that mothers and fathers who experienced material hardship at 15 months were likely to manage their conflict in destructive ways by being hostile to each other at 36 months, although these associations were no longer present in their main analyses, where material hardship at 36 months and destructive interparental conflict at 15 were also entered into their models. That said, the researchers did find that paternal depressive symptoms at 15 months (but not maternal depressive symptoms) were linked with higher levels of destructive interparental conflict at 36 months as reported by both fathers and mothers. Collectively, these studies indicate that material hardship may be linked with higher levels of destructive interparental conflict primarily through paternal depressive symptoms over maternal depressive symptoms. However, additional research, using data from both mothers and fathers from socioeconomically disadvantaged contexts, is needed to test the FSM proposed pathways by which economic insecurity is linked with couples’ destructive interparental conflict (i.e., via mothers’ and fathers’ depressive symptoms).

CURRENT STUDY

The current study aimed to use the FSM to investigate the mediating pathways between economic insecurity and family functioning. In particular, although the FSM includes pathways to parenting behaviors and child development, the current study focused on couples’ destructive conflict as the key outcome and material hardship and parental depressive symptoms as mediators. The current study contributes to the literature in several domains. First, we examined the FSM processes linking two kinds of economic insecurity (i.e., family income and material hardship) to parental mental health and interparental conflict. Second, we used a large sample of racially diverse families with high levels of socioeconomic disadvantage. Third, we examined these mechanisms for mothers and fathers, addressing gaps in knowledge related to testing the FSM with data involving both mothers and fathers with low income. Finally, we took advantage of the well-established research base of the FSM by using a Bayesian approach to mediation analysis. A Bayesian approach has the benefit of mathematically incorporating into models the empirical results from previous studies in the form of prior distributions and thus allows for building directly on an evidence base. Another way to understand this method is if we were able to quantify our initial beliefs about a research question of interest (i.e., pooling evidence from previous FSM studies), we could possibly update those beliefs with new data (Kruschke, 2014).

On the basis of prior material hardship measurement research (Ouellette et al., 2004), we operationalized material hardship to include whether families had medical care, residential stability, and the ability to pay monthly bills (Ouellette et al., 2004). These measures of material hardship extend beyond the objective measure of income to encompass the difficulties that parents may face “making ends meet,” even when income may be above the poverty threshold. Consistent with prior research extending the FSM to include material hardship (Gard et al., 2020; Gershoff et al., 2007; Shelleby, 2018), we first hypothesized that the effects of household income poverty on mothers’ and fathers’ depressive symptoms would be mediated by families’ material hardship (Hypothesis 1). Informed by the original FSM model and subsequent work (Conger er al., 1990; Conger & Elder, 1994; Curran et al., 2021; Masarik & Conger, 2017), we also hypothesized that mothers’ and fathers’ depressive symptoms would mediate the associations between material hardship and destructive interparental conflict (Hypothesis 2).

METHODS

The Building Strong Families project

Data were from the BSF project, a large-scale demonstration and evaluation of a healthy marriage and relationship education program conducted between 2002 and 2013. Active data collection occurred between 2005 and 2008 across eight cities in the United States for low-income, romantically involved, and unmarried heterosexual couples who were expecting or recently had a baby together (Wood et al., 2010). The project was sponsored by the Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation in the Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, and developed, implemented, and evaluated by Mathematica Policy Research with the goal to strengthen unmarried, socioeconomically disadvantaged couples’ relationships so that they could create stable and healthy home environments for their children (Wood et al., 2010).

Procedures

The BSF project recruited 5,102 couples from hospitals, maternity wards, prenatal clinics, health clinics, and special nutritional programs for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC). Couples were eligible to enroll if (a) both the mother and father agreed to participate in the intervention, (b) the couple was romantically involved, (c) the couple was either expecting a baby together or had a baby younger than 3 months old, (d) the couple was unmarried at the time the baby was conceived, and (e) both parents were 18 years and older (Wood et al., 2010). After recruitment, Mathematica Policy Research obtained participants’ written consents and randomly assigned couples into an intervention group (n = 2,553) or a control group (n = 2,549), where the intervention group received 30 to 42 hours of relationship education but the control group did not. Data collection occurred at three time points in the BSF project: baseline (enrollment in the project), the 15-month follow-up (15 months after enrollment in the BSF project using telephone surveys), and the 36-month follow-up (36 months after enrollment in the BSF project using telephone surveys). The Institutional Review Board (IRB) at the University of Michigan determined that secondary analysis of BSF data was exempt from IRB oversight.

Participants

The analytic sample consisted of BSF families in which the father was residential with the mother and child across all three data collection time points. Consistent with prior research examining residential fathers in the BSF sample (J. Y. Lee et al., 2020, 2021b), fathers’ residential status was defined as living with the mother and child all or most of the time at each time point. To create the analytic sample, 18 families with a deceased BSF partner were first excluded from the original sample of 5,102 families. Next, 2,290 fathers who reported living only some or none of the time with the mother and child across all three periods were excluded because they were considered nonresidential fathers, for whom family functioning may be different compared to residential fathers. Again, this sample selection approach aligns with previous research with BSF residential father families (J. Y. Lee et al., 2020, 2021b). The final analytic sample was N = 2,794 families in which the fathers were consistently residential all or most of the time with the mother and child across all three time points.

Measures

Income poverty

BSF families’ income poverty measured at the 15-month follow-up survey was the independent variable and used both fathers’ and mothers’ reports of their individual incomes contributed to the family in the past month (i.e., “What were your total earnings in the past month before taxes and other deductions? Please include tips, commissions, and overtime pay”). Mothers and fathers were asked to provide a specific numeric amount for their monthly incomes. Both parents’ reports were summed to create a composite variable that captures BSF families’ income in the past month. The mean of the families’ annual income was $28,360.20, which corresponded to approximately 150% of the federal poverty threshold for a family of four in 2005 (Georgia Department of Community Health, 2005). Families with annual income falling between 100% and 200% of the poverty threshold are considered families with low income (U.S. Census Bureau, n.d.).

Material hardship

Material hardship measured at the 15-month follow-up survey served as another independent variable, as well as a mediating variable. It used mothers’ and fathers’ reports of the following four indicators of material hardship: (a) ability to pay rent assessed families’ hardship paying rent or mortgage in the past year (i.e., “You could not pay the full amount of the rent or mortgage?”) with a binary response of 0 = no or 1 = yes; (b) consistency of utilities assessed hardship families experienced related to utilities in the past year (i.e., “You had services turned off by the water, gas, or electric company or the oil company would not deliver oil in the past 12 months because you could not afford to pay the bill?”) with a binary response of 0 = no or 1 = yes; (c) residential stability assessed hardship families experienced related to housing in the past year (i.e., “You were evicted from your home or apartment because you could not pay the rent or mortgage”?) with a binary response of 0 = no or 1 = yes; and (d) medical care assessed the hardship families experienced related to medical insurance. Two questions were asked (i.e., “Are you currently covered by Medicaid, [STATE/LOCAL FILL], or any other government program that pays for medical care?” and “Are you currently covered by health insurance through your or someone else’s employer or insurance purchased directly from a private insurance company?”) with a binary response of 0 = no or 1 = yes. The medical care indicators were reverse-coded to be consistent with the other material hardship indicators and combined to create a single measure of medical hardship. A response of 1 indicated the presence of any medical hardship and 0 no medical hardship with respect to insurance coverage. Mothers’ reports were used primarily to create a composite variable indicating families’ material hardship, although where data from mothers were missing, fathers’ reports were used.

Parental depressive symptoms

Mothers’ and fathers’ depressive symptoms measured at the 15-month follow-up survey served as the primary mediating variables. Parents’ depressive symptoms were measured by asking both mothers and fathers to report on a 12-item version of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D; Radloff, 1977). The CES-D assessed the prevalence of depressive symptoms (e.g., felt depressed, experienced sleep problems, had difficulty concentrating) in the past week. Both parents rated the items on a 4-point scale ranging from 1 = rarely or none of the time (less than 1 day in the past week) to 4 = most or all of the time (5–7 days in the past week). Higher scores reflected higher levels of depressive symptoms. Composite variables for mothers (α = 0.85) and fathers (α = 0.81) were created by averaging the 12 items.

Couples’ destructive interparental conflict

Mothers’ and fathers’ reports of couple conflict measured at the 36-month follow-up survey were the dependent variables, which captured destructive interparental conflict behaviors as described by Cummings and Davies (2010). The measure had nine items that primarily represented moderate verbal aggression couples use that could be harmful to the partner relationship (e.g., “Partner blames me for things that go wrong,” “Partner puts down my opinions, feelings, or desires”). Both mothers and fathers rated the items on a 4-point scale from 1 = often to 4 = never. The scale was reverse-coded so that higher scores reflected more frequent use of destructive interparental conflict behaviors. Composite variables for mothers (α = 0.88) and fathers (α = 0.86) were created by averaging the nine items.

Sociodemographic control variables

A robust set of sociodemographic variables from baseline, when the couples enrolled in the BSF project, were used as control variables in all of the analytic models. Consistent with previous literature, these included mothers’ and fathers’ age, education (Sobolewski & Amato, 2005), ethnicity and race (DeNavas-Walt et al., 2011), work status (Sayer et al., 2011), number of children BSF couples had together (Paulson et al., 2006), multiple-partner fertility (Turney & Carlson, 2011), couples’ marital status (McLanahan & Beck, 2010), couples’ relationship length, couples’ random assignment status in the BSF project (to account for BSF intervention effects), BSF program site (to account for income variability across geographic locations), and mothers’ reports of receiving public welfare, which asked about whether the mother received cash welfare, food stamps, Medicaid, Supplemental Security Income, WIC, or unemployment compensations. A sum score was created for mothers’ reports of receiving public welfare. Fathers’ additional financial support for children, which asked how much the fathers cover the cost of raising the focal child on a scale of 1 = all or almost all to 5 = little or none, was based on mothers’ reports at the 15-month follow-up survey. The scale was reverse-coded so that higher scores reflected more cost of raising children covered by the fathers. For models testing destructive interparental conflict at 36 months as the main outcome, the following variables at 36 months were also controlled for: income poverty, material hardship, maternal depressive symptoms, and paternal depressive symptoms.

Analysis plan

Bayesian statistics

In the simplest terms, a Bayesian method assesses the degree to which data make a claim more or less plausible (Gronau et al., 2021). According to Kruschke (2014), if we are able to quantify our initial beliefs about a research question of interest, we can update those beliefs with data. In applications with real data, however, the mathematics of the Bayesian approach may admittedly become difficult. One way to approach this is to create prior distributions from results of previous studies (e.g., pooling their regression coefficients) that can be mathematically incorporated into models being tested. This allows for examining whether prior study results impact results of interest given the set of new data. There are several advantages to using Bayesian statistics over the frequentist approach (van de Schoot et al., 2014). First, Bayesian analysis allows for incorporating prior evidence (or lack thereof) into the analyses using new data. Prior beliefs can come from diverse sources, including clinical expertise and previous studies. This allows the researcher to account for prior evidence in the analysis of new data, which ultimately yields updated results in the form of posterior distributions. Second, Bayesian statistics provide a credible interval—specifically, a 95% credible interval, which suggests that there is a 95% probability that the estimated value lies within the limits of the interval (compared with a 95% frequentist confidence interval, which is interpreted as of an infinite number of samples drawn from the population, 95% of them contain the true population estimate under the null hypothesis (van de Schoot et al., 2014). Finally, a Bayesian approach is useful for handling nonnormal parameters because, unlike the frequentist approach, it does not require normal distributions of parameters in the model (van de Schoot et al., 2014).

Bayesian mediation analysis

The current study employed a Bayesian mediation analysis within a regression framework. Given the substantial evidence base of studies testing the FSM, such prior information could be useful in informing the current study despite differences in measures and methodology. To fit a Bayesian mediation model, the current study used the “brms” package (Bürkner, 2017) available in R Version 3.61 (R Core Team, 2021). Both informative and uninformative (or default) priors were used in the models. Informative priors give numerical information crucial to estimating a model, and such numerical information typically comes from a literature review or earlier data analysis (Gelman, 2007). A literature review was conducted for articles using similar samples (e.g., racially diverse families from socioeconomically disadvantaged contexts) to test the FSM. A total of 13 articles were identified and reviewed (Conger et al., 2002; Derlan et al., 2019; Hardaway & Cornelius, 2014; Helms et al., 2014; Iruka et al., 2012; Landers-Potts et al., 2015; Martin et al., 2019; Newland et al., 2013; O’Neal et al., 2015; Parke et al., 2004; Ponnet, 2014; Shelleby, 2018; Simons et al., 2016). The articles were examined for their means and standard deviations of relevant regression paths (e.g., income to material hardship, material hardship to maternal depression). Means were averaged to create pooled means and whichever standard error information available in the articles was used as standard deviations for individual priors entered into the analytic models.

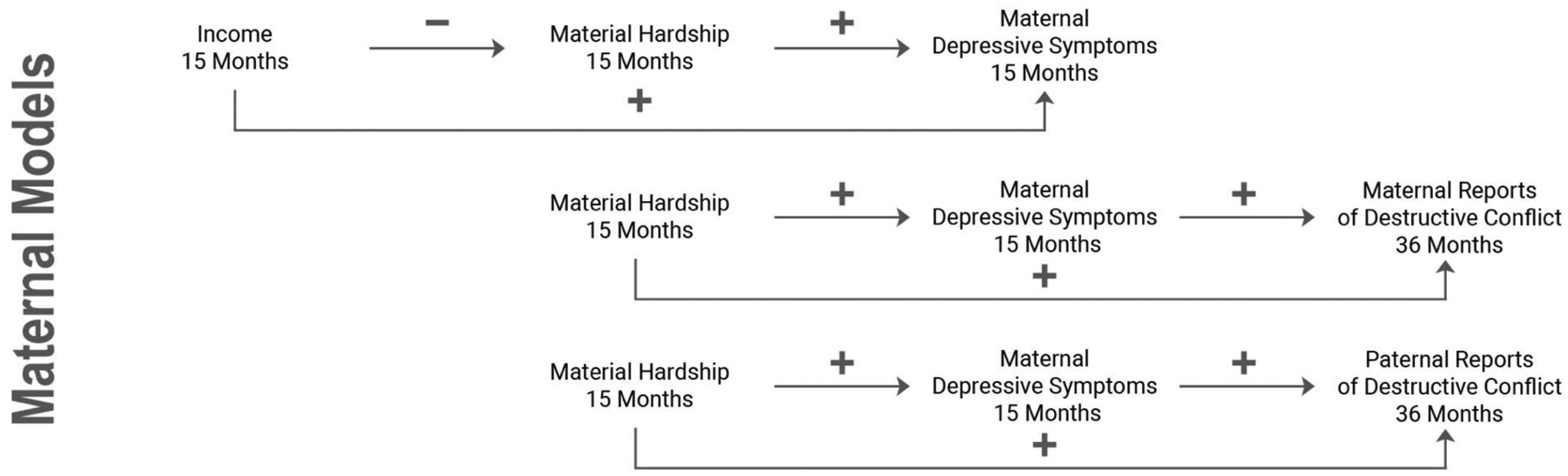

Informed by the FSM, three models were investigated for mothers, which are shown in Figure 1. The first model tested material hardship as a mediator between family income and maternal depressive symptoms. The second model tested maternal depressive symptoms as a mediator between material hardship and mothers’ reports of destructive interparental conflict. The third model tested maternal depressive symptoms as a mediator between material hardship and fathers’ reports of destructive interparental conflict. With regard to the specific prior values in these maternal models, the income poverty to material hardship path had an informative prior with M = −0.25 and SD = 0.07, and the material hardship to maternal depressive symptoms path had an informative prior with M = 0.33 and SD = 0.07. The maternal depressive symptoms to destructive interparental conflict path had an informative prior with M = 0.25 and SD = 0.10, and the material hardship to destructive interparental conflict path had an informative prior with M = 0.01 and SD = 0.10.

FIGURE 1.

Three conceptual models for mothers as informed by the family stress model

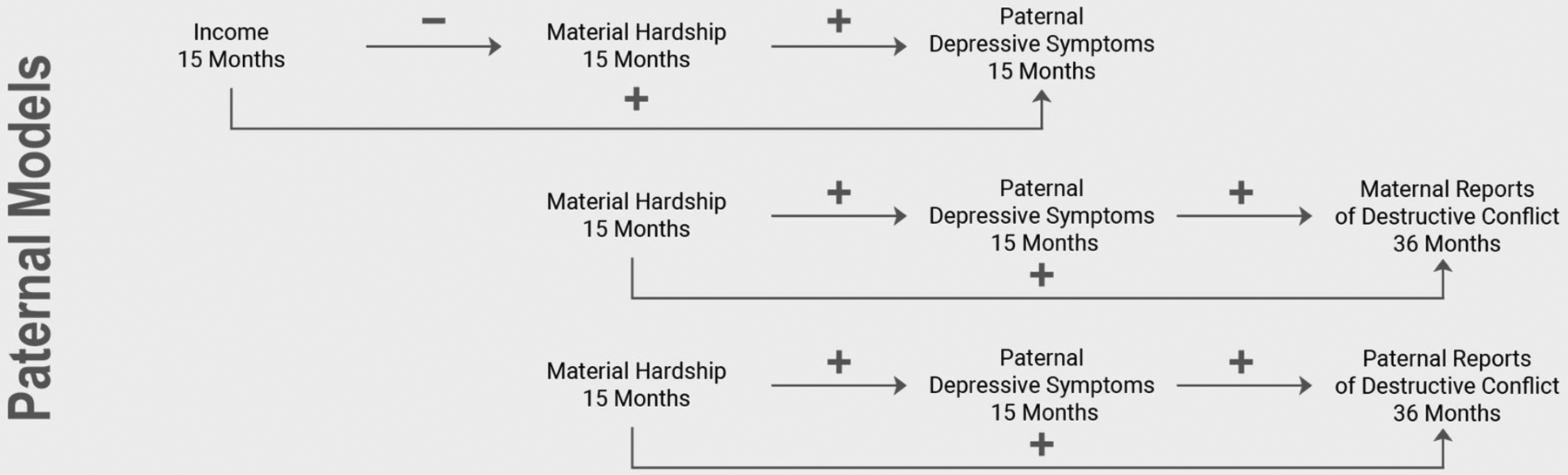

Similarly, informed by the FSM, the same three models were tested for fathers, which are shown in Figure 2. Specifically, the first model tested material hardship as a mediator between family income and paternal depressive symptoms. The second model tested paternal depressive symptoms as a mediator between material hardship and mothers’ reports of destructive interparental conflict. The third model tested paternal depressive symptoms as a mediator between material hardship and fathers’ reports of destructive interparental conflict. In these paternal models, the income poverty to material hardship path had an informative prior with M = −0.29 and SD = 0.10, and the material hardship to paternal depressive symptoms path had an informative prior with M = 0.26 and SD = 0.10. The paternal depressive symptoms to destructive interparental conflict path had an informative prior with M = 0.23 and SD = 0.10, and the material hardship to destructive interparental conflict path had an informative prior with M = 0.09 and SD = 0.10.

FIGURE 2.

Three conceptual models for fathers as informed by the family stress model

For the remaining regression paths in the models, including the links between the study’s key variables and control variables, uninformative priors (M = 0, SD = 100) were used because of the complexity involved in pooling varied information pertaining to sociodemographic variables across studies. Sensitivity analyses were also conducted for different prior specifications. Effect sizes were estimated as the percentage of the model R2 explained by the predictors. The credible interval represented the boundaries within which parameters of interest were expected to fall.

Missing data

Stata’s Version 15 (StataCorp, 2017) missingness pattern analysis and logistic regression were used to examine missing data. Stata’s missingness pattern analysis showed that data were missing in 0% to 43.70% (for fathers’ depressive symptoms) of the cases. Data for family income and material hardship at 15 months were missing in 28.13% and 18.97% of the cases, respectively. Data for mothers’ and fathers’ depressive symptoms at 15 months were missing in 19.43% and 33.46% of the cases, respectively. Data for mothers’ reports and fathers’ reports of destructive interpersonal conflict at 36 months were missing in 32.96% and 43.31% of the cases, respectively. Across all sociodemographic control variables, data were missing in less than 3.33% of the cases, with the exception of mothers’ reports of receiving public welfare at baseline (16.89%), fathers’ financial support at 15 months (22.26%), family income at 36 months (64.92%), material hardship at 36 months (24.77%), mothers’ depressive symptoms at 36 months (25.98%), and fathers’ depressive symptoms at 36 months (43.70%).

Results from logistic regressions showed that missing cases for family income were missing at random (MAR), which indicates that missingness is conditional on other variables in the dataset. Indeed, missing values of family income were significant associated with maternal depressive symptoms (p = 0.03), paternal depressive symptoms (p = 0.04), education level (p = 0.01), ethnicity/race (p = 0.03), and fathers’ work status (p = 0.01). Missing cases for family material hardship were MAR as well, where missing values were significantly linked with fathers’ work status (p = 0.01). Missing cases for fathers’ depressive symptoms were MAR, with missing values significantly linked with family income (p = 0.00), fathers’ age (p = 0.04), fathers’ additional financial support (p = 0.00). Missing cases for mothers’ depressive symptom were MAR, with missing values significantly associated with mothers’ multiple-partner fertility (p = 0.01). Missing cases for mothers’ reports of destructive interparental conflict were MAR, with missing values significantly associated with fathers’ additional financial support (p = 0.03) and family income at 15 months (p = 0.03) and 36 months (p = 0.03). Missing cases for fathers’ reports of destructive interparental conflict were not associated with any of the observed variables, suggesting missing completely at random. That said, the missing data mechanism was more likely MAR given the possibility that missing cases in fathers’ reports of destructive interparental conflict depended on observed variables of the original (and not the current subset of) BSF dataset.

Although listwise deletion is the default in R for Bayesian mediation analysis, multiple imputation (MI) was used to account for all cases and missing data patterns given that listwise deletion would result in losing approximately half of the analytic sample. MI is a mechanism for handling missing data (Rubin, 2004). MI replaces each missing value with two or more acceptable values, representing a distribution of possibilities (Rubin, 2004). In particular, using the “mice” package (van Buuren & Groothuis-Oudshoorn, 2011), R generates multiple imputations for incomplete multivariate data using Gibbs sampling, and the algorithm imputes missing data by generating plausible values given information from available data. Each column with missing data serves as a target, and columns with complete data function as a set of predictors to produce imputation values (also known as massive imputation) (van Buuren, 2020). The default method was used with predictive mean matching for variables with numeric data, logistic regression imputation for variables with binary data, and proportional odds model for variables with ordered categorical data. The number of multiple imputations was set to m = 100 (Graham et al., 2007; Rubin, 2004).

RESULTS

Descriptive statistics

Mothers and fathers were young (mothers: M = 23.59 years, SD = 4.83; fathers: M = 26.00 years, SD = 6.14). Couples were from economically disadvantaged contexts, as demonstrated by an average monthly household income of $2,363.35, with at least one material hardship experienced in the past year (M = 1.38, SD = 0.62). Couples were racially and ethnically diverse, with 43.52% being Black, 28.88% Latinx, 17.28% White, and 10.31% Other. Approximately half of the couples (47.85%) reported that both mothers and fathers had a high school diploma, and another third (33.97%) reported that only one parent had a high school diploma. In general, both mothers and fathers reported relatively low levels of depressive symptoms (mothers: M = 1.39, SD = 0.49; fathers: M = 1.29, SD = 0.39; range: 1–4 for both parents) and destructive interparental conflict (mothers: M = 2.12, SD = 0.73; fathers: M = 2.10, SD = 0.68; range: 1–4 for both parents). Details of sample characteristics and descriptive statistics of key variables are further provided in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Sample characteristics and descriptive statistics of main study variables

| Variable | M (SD) or % |

|---|---|

| Mothers’ age (range: 18–41), years | 23.59 (4.83) |

| Fathers’ age (range: 18–52), years | 26.00 (6.14) |

| Couples’ ethnicity and race | |

| Black | 43.52% |

| Latinx | 28.88% |

| White | 17.28% |

| Other | 10.31% |

| Couples’ education | |

| Neither parent has high school diploma | 18.18% |

| One parent has high school diploma | 33.97% |

| Both parents have high school diploma | 47.85% |

| Couple relationship length (range: 0.02–25), years | 3.62 (3.36) |

| Couple married (yes) | 8.95% |

| Mothers’ work status (yes) | 24.80% |

| Fathers’ work status (yes) | 78.10% |

| Number of biological children mothers have with BSF fathers | 1.43 (0.77) |

| Mothers’ multiple-partner fertility (yes) | 32.18% |

| Fathers’ multiple-partner fertility (yes) | 30.31% |

| Mothers’ reports of welfare receipt | 1.88 (1.17) |

| Assignment in the BSF program (intervention) | 50.54% |

| Mothers’ reports of fathers’ financial support to raise childrena | 3.93 (1.29) |

| Monthly family incomea | $2,363.35 ($4,614.25) |

| Material hardshipa (range: 0–4) | 1.38 (0.62) |

| Maternal depressive symptomsa (range: 1–4) | 1.39 (0.49) |

| Paternal depressive symptomsa (range: 1–4) | 1.29 (0.39) |

| Mothers’ reports of destructive interparental conflictb (range: 1–4) | 2.12 (0.73) |

| Fathers’ reports of destructive interparental conflictb (range: 1–4) | 2.10 (0.68) |

Note. N = 2,794. Unless otherwise stated, all variables are from baseline when couples enrolled in the BSF project. BSF = Building Strong Families.

Variable is from the 15-month follow-up period.

Variable is from the 36-month follow-up period.

Bayesian mediation analysis results

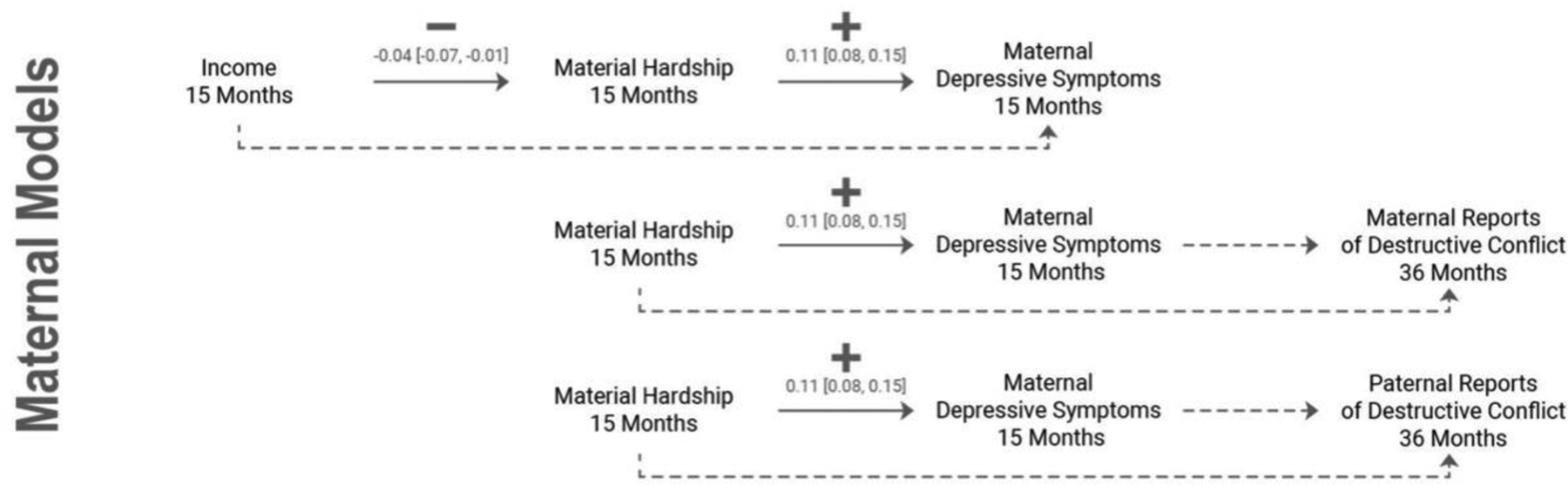

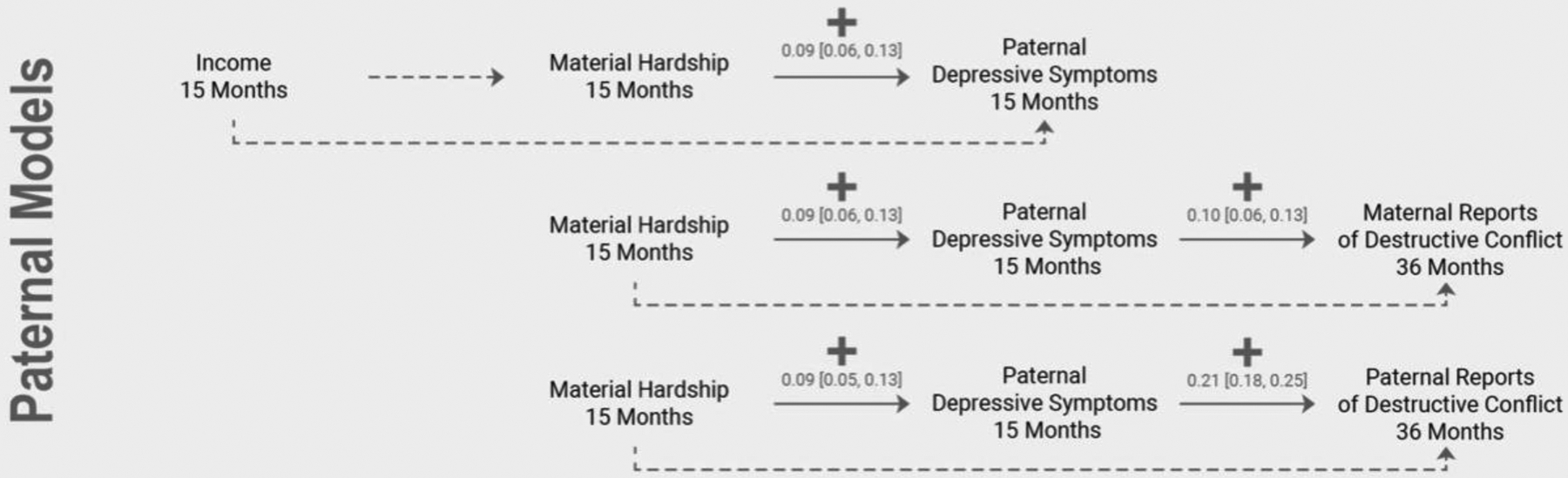

Results from the Bayesian mediation analysis can be found in Tables 2, 3, and 4. Interpretations of the Bayesian mediation results are primarily based on the mean of the parameter estimate, as well as the 95% credible interval for the parameter estimate. When a two-tailed credible interval excludes 0, it suggests that there is a 95% probability that the parameter estimate is not 0. Three models were investigated for mothers: (a) material hardship as a mediator between family income and maternal depressive symptoms, (b) maternal depressive symptoms as a mediator between material hardship and mothers’ reports of destructive interparental conflict, and (c) maternal depressive symptoms as a mediator between material hardship and fathers’ reports of destructive interparental conflict. The same three models were also investigated for fathers: (d) material hardship as a mediator between family income and paternal depressive symptoms, (e) paternal depressive symptoms as a mediator between material hardship and mothers’ reports of destructive interparental conflict, and (f) paternal depressive symptoms as a mediator between material hardship and fathers’ reports of destructive interparental conflict. All models converged normally with chains in the models reaching a value close or equal to 1. Figure 3 provides a graphical illustration that summarizes the main findings of all maternal and paternal models.

TABLE 2.

Bayesian mediation results for family income predicting parental depressive symptoms via material hardship

| Maternal model | Paternal model | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SE | 95% CI | M | SE | 95% CI | |

| Material hardship at 15 months | ||||||

| Family income at 15 monthsa | −0.04 | 0.02 | [−0.07, −0.01] | −0.03 | 0.02 | [−0.07, 0.00] |

| Fathers’ age | 0.00 | 0.03 | [−0.04, 0.05] | 0.00 | 0.03 | [−0.04, 0.05] |

| Mothers’ age | 0.01 | 0.03 | [−0.05, 0.06] | −0.01 | 0.03 | [−0.04, 0.06] |

| Couples’ education level | −0.01 | 0.02 | [−0.05, 0.03] | −0.01 | 0.02 | [−0.05, 0.03] |

| Couples’ race and ethnicity | ||||||

| Black | 0.03 | 0.03 | [−0.03, 0.09] | 0.03 | 0.03 | [−0.03, 0.09] |

| White | 0.04 | 0.02 | [−0.01, 0.08] | 0.04 | 0.02 | [−0.01, 0.08] |

| Other | 0.03 | 0.02 | [−0.01, 0.07] | 0.03 | 0.02 | [−0.01, 0.07] |

| Couples’ relationship length | −0.01 | 0.02 | [−0.05, 0.03] | −0.01 | 0.02 | [−0.05, 0.03] |

| Couples’ marital status | 0.03 | 0.02 | [−0.01, 0.06] | 0.03 | 0.02 | [−0.01, 0.07] |

| Number of biological children mothers have with BSF fathers | 0.04 | 0.02 | [−0.01, 0.08] | 0.04 | 0.02 | [−0.01, 0.08] |

| Fathers’ work status | −0.04 | 0.02 | [−0.07, 0.00] | −0.04 | 0.02 | [−0.07, 0.00] |

| Mothers’ work status | −0.01 | 0.02 | [−0.03, 0.05] | 0.01 | 0.02 | [−0.03, 0.05] |

| Fathers’ multiple-partner fertility | 0.01 | 0.02 | [−0.04, 0.05] | 0.00 | 0.02 | [−0.04, 0.04] |

| Mothers’ multiple-partner fertility | 0.04 | 0.02 | [0.00, 0.09] | 0.04 | 0.02 | [0.00, 0.09] |

| Receipt of public welfare | 0.01 | 0.02 | [−0.03, 0.06] | 0.01 | 0.02 | [−0.03, 0.06] |

| Fathers’ financial support at 15 months | 0.00 | 0.02 | [−0.04, 0.03] | 0.00 | 0.02 | [−0.05, 0.04] |

| Assignment in the BSF program | −0.03 | 0.02 | [−0.07, 0.01] | −0.03 | 0.02 | [−0.07, 0.01] |

| Location of the BSF program site | 0.00 | 0.02 | [−0.04, 0.05] | −0.05 | 0.02 | [−0.09, 0.00] |

| Intercept | 0.00 | 0.02 | [−0.04, 0.04] | 0.00 | 0.02 | [−0.04, 0.04] |

| Parental depressive symptoms at 15 months | ||||||

| Family income at 15 monthsa | 0.03 | 0.02 | [−0.01, 0.06] | −0.02 | 0.02 | [−0.05, 0.02] |

| Material hardship at 15 monthsa | 0.11 | 0.02 | [0.08, 0.15] | 0.09 | 0.02 | [0.06, 0.13] |

| Maternal depression at 15 months | — | — | — | 0.03 | 0.02 | [−0.01, 0.07] |

| Paternal depression at 15 months | 0.03 | 0.02 | [−0.01, 0.07] | — | — | — |

| Fathers’ age | 0.02 | 0.02 | [−0.03, 0.07] | 0.01 | 0.02 | [−0.04, 0.06] |

| Mothers’ age | −0.02 | 0.03 | [−0.07, 0.04] | −0.02 | 0.03 | [−0.07, 0.03] |

| Couples’ education level | −0.01 | 0.02 | [−0.05, 0.03] | 0.01 | 0.02 | [−0.02, 0.05] |

| Couples’ race and ethnicity | ||||||

| Black | 0.07 | 0.03 | [0.02, 0.12] | 0.15 | 0.03 | [0.09, 0.20] |

| White | 0.03 | 0.02 | [−0.01, 0.08] | 0.07 | 0.02 | [0.02, 0.11] |

| Other | 0.02 | 0.02 | [−0.02, 0.06] | 0.09 | 0.02 | [0.04, 0.13] |

| Couples’ relationship length | 0.02 | 0.02 | [−0.03, 0.06] | −0.01 | 0.02 | [−0.05, 0.03] |

| Couples’ marital status | 0.01 | 0.02 | [−0.03, 0.04] | 0.00 | 0.02 | [−0.03, 0.04] |

| Number of biological children mothers have with BSF fathers | −0.01 | 0.02 | [−0.04, 0.03] | 0.05 | 0.02 | [0.01, 0.09] |

| Fathers’ work status | −0.01 | 0.02 | [−0.05, 0.03] | −0.05 | 0.02 | [−0.08, −0.01] |

| Mothers’ work status | −0.06 | 0.02 | [−0.09, −0.02] | 0.02 | 0.02 | [−0.02, 0.06] |

| Fathers’ multiple-partner fertility | 0.01 | 0.02 | [−0.03, 0.05] | 0.04 | 0.02 | [0.00, 0.09] |

| Mothers’ multiple-partner fertility | 0.01 | 0.02 | [−0.03, 0.05] | 0.04 | 0.02 | [0.03, 0.09] |

| Receipt of public welfare | 0.03 | 0.02 | [−0.01, 0.07] | 0.04 | 0.02 | [0.00, 0.08] |

| Fathers’ financial support at 15 months | −0.23 | 0.02 | [−0.27, −0.19] | 0.14 | 0.02 | [0.10, 0.18] |

| Assignment in the BSF program | −0.06 | 0.02 | [−0.10, −0.03] | −0.02 | 0.02 | [−0.06, 0.02] |

| Location of the BSF program site | −0.01 | 0.02 | [−0.05, 0.03] | −0.05 | 0.02 | [−0.09, 0.00] |

| Intercept | 0.00 | 0.02 | [−0.04, 0.03] | 0.00 | 0.02 | [−0.04, 0.04] |

| Indirect effect | −0.004 | [−0.009, −0.001] | 0.00 | [−0.01, 0.00] | ||

| Direct effect | 0.03 | [−0.01, 0.07] | −0.02 | [−0.05, 0.02] | ||

| Total effect | 0.02 | [−0.02, 0.06] | −0.02 | [−0.06, 0.01] | ||

| R2 for material hardship | 1.65% | [0.88, 2.55] | 1.62% | [0.88, 2.51] | ||

| R2 for parental depressive symptoms | 9.47% | [7.50, 11.46] | 6.40% | [4.82, 8.13] | ||

Note. Bold indicates parameter estimate whose credible interval excludes a 0, suggesting that there is a 95% probability that the estimated value is not equal to 0 and lies within the limits of the credible interval. BSF = Building Strong Families; CI = credible interval.

Main predictor variable of interest to the model.

TABLE 3.

Bayesian mediation results for material hardship predicting mothers’ reports of destructive interparental conflict via parental depressive symptoms

| Maternal model | Paternal model | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SE | 95% CI | M | SE | 95% CI | |

| Parental depressive symptoms at 15 months | ||||||

| Material hardship at 15 monthsa | 0.11 | 0.02 | [0.08, 0.15] | 0.09 | 0.02 | [0.06, 0.13] |

| Maternal depression at 15 months | — | — | — | 0.03 | 0.02 | [−0.01, 0.07] |

| Paternal depression at 15 months | 0.03 | 0.02 | [−0.01, 0.07] | — | — | — |

| Fathers’ age | 0.02 | 0.03 | [−0.03, 0.07] | 0.01 | 0.03 | [−0.04, 0.06] |

| Mothers’ age | −0.01 | 0.03 | [−0.06, 0.03] | −0.02 | 0.03 | [−0.07, 0.03] |

| Couples’ education level | −0.01 | 0.02 | [−0.05, 0.03] | 0.01 | 0.02 | [−0.03, 0.05] |

| Couples’ race and ethnicity | ||||||

| Black | 0.07 | 0.03 | [0.01, 0.12] | 0.15 | 0.03 | [0.09, 0.21] |

| White | 0.03 | 0.02 | [−0.01, 0.08] | 0.07 | 0.02 | [0.02, 0.11] |

| Other | 0.02 | 0.02 | [−0.02, 0.06] | 0.09 | 0.02 | [0.04, 0.13] |

| Couples’ relationship length | 0.02 | 0.02 | [−0.02, 0.06] | −0.01 | 0.02 | [−0.05, 0.03] |

| Couples’ marital status | 0.01 | 0.02 | [−0.03, 0.04] | 0.00 | 0.02 | [−0.03, 0.04] |

| Number of biological children mothers have with BSF fathers | −0.01 | 0.02 | [−0.05, 0.04] | 0.05 | 0.02 | [0.01, 0.09] |

| Fathers’ work status | −0.01 | 0.02 | [−0.04, 0.03] | −0.05 | 0.02 | [−0.08, −0.01] |

| Mothers’ work status | −0.06 | 0.02 | [−0.09, −0.02] | 0.02 | 0.02 | [−0.02, 0.06] |

| Fathers’ multiple-partner fertility | 0.01 | 0.02 | [−0.03, 0.05] | 0.04 | 0.02 | [0.00, 0.08] |

| Mothers’ multiple-partner fertility | 0.01 | 0.02 | [−0.03, 0.05] | 0.04 | 0.02 | [0.00, 0.08] |

| Receipt of public welfare | 0.03 | 0.02 | [−0.01, 0.07] | 0.04 | 0.02 | [0.00, 0.08] |

| Fathers’ financial support at 15 months | −0.23 | 0.02 | [−0.26, −0.19] | 0.14 | 0.02 | [0.10, 0.18] |

| Assignment in the BSF program | −0.06 | 0.02 | [−0.10, −0.03] | −0.02 | 0.02 | [−0.06, 0.01] |

| Location of the BSF program site | −0.01 | 0.02 | [−0.06, 0.03] | −0.05 | 0.02 | [−0.09, 0.00] |

| Intercept | 0.00 | 0.02 | [−0.04, 0.04] | 0.00 | 0.02 | [−0.04, 0.04] |

| Mothers’ reports of destructive interparental conflict at 36 months | ||||||

| Material hardship at 15 monthsa | 0.02 | 0.02 | [−0.01, 0.06] | 0.03 | 0.02 | [−0.01, 0.06] |

| Material hardship at 36 months | 0.06 | 0.02 | [0.02, 0.09] | 0.05 | 0.02 | [0.02, 0.09] |

| Maternal depression at 15 monthsa | 0.02 | 0.02 | [−0.02, 0.05] | 0.01 | 0.02 | [−0.03, 0.04] |

| Maternal depression at 36 months | 0.34 | 0.02 | [0.30, 0.37] | 0.34 | 0.02 | [0.30, 0.37] |

| Paternal depression at 15 monthsa | 0.09 | 0.02 | [0.05, 0.13] | 0.10 | 0.02 | [0.06, 0.13] |

| Paternal depression at 36 months | −0.06 | 0.02 | [−0.10, −0.02] | −0.06 | 0.02 | [−0.09, −0.02] |

| Family income at 36 months | 0.01 | 0.02 | [−0.03, 0.04] | 0.01 | 0.02 | [−0.03, 0.04] |

| Fathers’ age | −0.03 | 0.02 | [−0.07, 0.02] | −0.03 | 0.02 | [−0.07, 0.02] |

| Mothers’ age | 0.05 | 0.02 | [0.00, 0.09] | 0.05 | 0.02 | [0.00, 0.09] |

| Couples’ education level | 0.04 | 0.02 | [0.00, 0.07] | 0.04 | 0.02 | [0.00, 0.07] |

| Couples’ race and ethnicity | ||||||

| Black | 0.04 | 0.03 | [−0.01, 0.09] | 0.04 | 0.03 | [−0.01, 0.09] |

| White | 0.04 | 0.02 | [0.00, 0.09] | 0.04 | 0.02 | [0.00, 0.08] |

| Other | 0.01 | 0.02 | [−0.03, 0.05] | 0.01 | 0.02 | [−0.03, 0.05] |

| Couples’ relationship length | 0.03 | 0.02 | [−0.01, 0.07] | 0.03 | 0.02 | [−0.01, 0.07] |

| Couples’ marital status | 0.00 | 0.02 | [−0.03, 0.04] | 0.00 | 0.02 | [−0.03, 0.04] |

| Number of biological children mothers have with BSF fathers | −0.01 | 0.02 | [−0.03, 0.02] | −0.02 | 0.02 | [−0.05, 0.02] |

| Fathers’ work status | −0.01 | 0.02 | [−0.04, 0.03] | −0.01 | 0.02 | [−0.04, 0.03] |

| Mothers’ work status | 0.03 | 0.02 | [−0.01, 0.06] | 0.03 | 0.02 | [−0.01, 0.06] |

| Fathers’ multiple-partner fertility | 0.00 | 0.02 | [−0.04, 0.04] | 0.00 | 0.02 | [−0.04, 0.03] |

| Mothers’ multiple-partner fertility | −0.01 | 0.02 | [−0.05, 0.03] | −0.01 | 0.02 | [−0.05, 0.03] |

| Receipt of public welfare | 0.01 | 0.02 | [−0.02, 0.05] | 0.01 | 0.02 | [−0.02, 0.05] |

| Fathers’ financial support at 15 months | 0.05 | 0.02 | [0.01, 0.09] | 0.05 | 0.02 | [0.01, 0.09] |

| Assignment in the BSF program | 0.04 | 0.02 | [0.00, 0.07] | 0.04 | 0.02 | [0.00, 0.07] |

| Location of the BSF program site | 0.02 | 0.02 | [−0.01, 0.06] | 0.02 | 0.02 | [−0.02, 0.07] |

| Intercept | 0.00 | 0.02 | [−0.03, 0.03] | 0.00 | 0.02 | [−0.03, 0.03] |

| Indirect effect | 0.00 | [0.00, 0.01] | 0.01 | [0.004, 0.014] | ||

| Direct effect | 0.02 | [−0.01, 0.06] | 0.03 | [−0.01, 0.06] | ||

| Total effect | 0.03 | [−0.01, 0.06] | 0.04 | [0.00, 0.07] | ||

| R2 for parental depressive symptoms | 9.33% | [7.47, 11.17] | 6.33% | [4.73, 8.10] | ||

| R2 for destructive interparental conflict | 17.11% | [14.81, 19.41] | 17.14% | [14.95, 19.54] | ||

Note. Bold indicates parameter estimate whose credible interval excludes a 0, suggesting that there is a 95% probability that the estimated value is not equal to 0 and lies within the limits of the credible interval. BSF = Building Strong Families; CI = credible interval.

Main predictor variable of interest to the model.

TABLE 4.

Bayesian mediation results for material hardship predicting fathers’ reports of destructive interparental conflict via parental depressive symptoms

| Maternal model | Paternal model | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SE | 95% CI | M | SE | 95% CI | |

| Parental depressive symptoms at 15 months | ||||||

| Material hardship at 15 monthsa | 0.11 | 0.02 | [0.08, 0.15] | 0.09 | 0.02 | [0.05, 0.13] |

| Maternal depression at 15 months | — | — | — | 0.03 | 0.02 | [−0.01, 0.07] |

| Paternal depression at 15 months | 0.03 | 0.02 | [−0.01, 0.07] | — | — | — |

| Fathers’ age | 0.02 | 0.02 | [−0.03, 0.07] | 0.01 | 0.02 | [−0.04, 0.06] |

| Mothers’ age | −0.01 | 0.03 | [−0.07, 0.03] | −0.02 | 0.03 | [−0.07, 0.03] |

| Couples’ education level | −0.01 | 0.02 | [−0.05, 0.03] | 0.01 | 0.02 | [−0.03, 0.05] |

| Couples’ race and ethnicity | ||||||

| Black | 0.07 | 0.03 | [0.01, 0.12] | 0.15 | 0.03 | [0.09, 0.21] |

| White | 0.03 | 0.02 | [−0.01, 0.08] | 0.07 | 0.02 | [0.03, 0.11] |

| Other | 0.02 | 0.02 | [−0.02, 0.06] | 0.09 | 0.02 | [0.04, 0.13] |

| Couples’ relationship length | 0.02 | 0.02 | [−0.03, 0.05] | −0.01 | 0.02 | [−0.05, 0.03] |

| Couples’ marital status | 0.01 | 0.02 | [−0.03, 0.05] | 0.00 | 0.02 | [−0.03, 0.04] |

| Number of biological children mothers have with BSF fathers | −0.01 | 0.02 | [−0.05, 0.04] | 0.05 | 0.02 | [0.00, 0.09] |

| Fathers’ work status | −0.01 | 0.02 | [−0.05, 0.03] | −;0.05 | 0.02 | [−0.08, −0.01] |

| Mothers’ work status | −0.06 | 0.02 | [−0.09, −0.02] | 0.02 | 0.02 | [−0.02, 0.06] |

| Fathers’ multiple-partner fertility | 0.01 | 0.02 | [−0.03, 0.05] | 0.04 | 0.02 | [0.00, 0.09] |

| Mothers’ multiple-partner fertility | 0.01 | 0.02 | [−0.03, 0.05] | 0.04 | 0.02 | [0.00, 0.09] |

| Receipt of public welfare | 0.03 | 0.02 | [−0.01, 0.07] | 0.04 | 0.02 | [0.00, 0.08] |

| Fathers’ financial support at 15 months | −0.23 | 0.02 | [−0.27, −0.19] | 0.14 | 0.02 | [0.10, 0.18] |

| Assignment in the BSF program | −0.06 | 0.02 | [−0.10, −0.03] | −0.02 | 0.02 | [−0.06, 0.02] |

| Location of the BSF program site | −0.01 | 0.02 | [−0.05, 0.03] | −0.05 | 0.02 | [−0.09, 0.00] |

| Intercept | 0.00 | 0.02 | [−0.03, 0.04] | 0.00 | 0.02 | [−0.04, 0.04] |

| Fathers’ reports of destructive interparental conflict at 36 months | ||||||

| Material hardship at 15 monthsa | 0.01 | 0.02 | [−0.03, 0.04] | 0.01 | 0.02 | [−0.02, 0.04] |

| Material hardship at 36 months | −0.01 | 0.02 | [−0.05, 0.03] | −0.01 | 0.02 | [−0.05, 0.02] |

| Family income at 36 months | 0.03 | 0.02 | [−0.01, 0.06] | 0.03 | 0.02 | [−0.01, 0.06] |

| Maternal depression at 15 monthsa | −0.04 | 0.02 | [−0.07, 0.00] | −0.05 | 0.02 | [−0.09, −0.01] |

| Maternal depression at 36 months | 0.12 | 0.02 | [0.08, 0.15] | 0.12 | 0.02 | [0.08, 0.16] |

| Paternal depression at 15 monthsa | 0.21 | 0.02 | [0.18, 0.25] | 0.21 | 0.02 | [0.18, 0.25] |

| Paternal depression at 36 months | −0.30 | 0.02 | [−0.34, −0.27] | −0.30 | 0.02 | [−0.34, −0.27] |

| Fathers’ age | 0.02 | 0.02 | [−0.03, 0.06] | 0.02 | 0.02 | [−0.03, 0.06] |

| Mothers’ age | −0.03 | 0.02 | [−0.07, 0.02] | −0.03 | 0.02 | [−0.07, 0.02] |

| Couples’ education level | 0.02 | 0.02 | [−0.02, 0.05] | 0.02 | 0.02 | [−0.02, 0.05] |

| Couples’ race and ethnicity | ||||||

| Black | 0.05 | 0.03 | [0.00, 0.10] | 0.05 | 0.03 | [0.00, 0.10] |

| White | 0.06 | 0.02 | [0.02, 0.10] | 0.06 | 0.02 | [0.01, 0.10] |

| Other | 0.01 | 0.02 | [−0.03, 0.05] | 0.01 | 0.02 | [−0.03, 0.05] |

| Couples’ relationship length | −0.01 | 0.02 | [−0.04, 0.03] | −0.01 | 0.02 | [−0.04, 0.03] |

| Couples’ marital status | 0.00 | 0.02 | [−0.03, 0.04] | 0.00 | 0.02 | [−0.03, 0.04] |

| Number of biological children mothers have with BSF fathers | 0.01 | 0.02 | [−0.03, 0.05] | 0.01 | 0.02 | [−0.03, 0.05] |

| Fathers’ work status | 0.00 | 0.02 | [−0.04, 0.04] | 0.00 | 0.02 | [−0.03, 0.04] |

| Mothers’ work status | 0.02 | 0.02 | [−0.01, 0.06] | 0.02 | 0.02 | [−0.01, 0.06] |

| Fathers’ multiple-partner fertility | 0.01 | 0.02 | [−0.03, 0.05] | 0.01 | 0.02 | [−0.03, 0.05] |

| Mothers’ multiple-partner fertility | 0.00 | 0.02 | [−0.03, 0.04] | 0.00 | 0.02 | [−0.03, 0.04] |

| Receipt of public welfare | 0.04 | 0.02 | [0.00, 0.07] | 0.04 | 0.02 | [0.00, 0.07] |

| Fathers’ financial support at 15 months | 0.08 | 0.02 | [0.04, 0.11] | 0.07 | 0.02 | [0.04, 0.11] |

| Assignment in the BSF program | 0.02 | 0.02 | [−0.01, 0.05] | 0.02 | 0.02 | [−0.02, 0.06] |

| Location of the BSF program site | −0.01 | 0.02 | [−0.06, 0.03] | −0.01 | 0.02 | [−0.05, 0.02] |

| Intercept | 0.00 | 0.02 | [−0.03, 0.03] | 0.00 | 0.02 | [−0.03, 0.03] |

| Indirect effect | 0.00 | [−0.01, 0.00] | 0.02 | [0.011, 0.028] | ||

| Direct effect | 0.01 | [−0.03, 0.04] | 0.01 | [−0.02, 0.04] | ||

| Total effect | 0.00 | [−0.03, 0.04] | 0.03 | [0.00, 0.06] | ||

| R2 for parental depressive symptoms | 9.34% | [7.42, 11.32] | 6.36% | [4.74, 7.99] | ||

| R2 for destructive interparental conflict | 18.57% | [16.28, 20.81] | 18.63% | [16.34, 20.97] | ||

Note. Bold indicates parameter estimate whose credible interval excludes a 0, suggesting that there is a 95% probability that the estimated value is not equal to 0 and lies within the limits of the credible interval. BSF = Building Strong Families; CI = credible interval.

Main predictor variable of interest to the model.

FIGURE 3.

Summary of all maternal models testing the associations between family income, material hardship, parental depressive symptoms, and destructive interparental conflict as informed by the family stress model

Note. Solid line indicates parameter estimate for which the credible interval excludes a 0, suggesting that there is a 95% probability that the estimated value is not equal to 0 and lies within the limits of the credible interval. Dotted line indicates parameter estimate for which the credible interval includes a 0.

Maternal model results

Family income at 15 months to maternal depressive symptoms at 15 months via material hardship at 15 months

As shown in the first model of Figure 3 and in Table 2, results of the family income model predicting maternal depressive symptoms at 15 months via material hardship at 15 months showed that family income at 15 months was linked with less material hardship at 15 months (estimate = −0.04, SE = 0.02, 95% credible interval [CI]: [−0.07, −0.01]), which was then linked with higher levels of maternal depressive symptoms at 15 months (estimate = 0.11, SE = 0.02, 95% CI: [0.08, 0.15]). Family income at 15 months was not directly linked with maternal depressive symptoms at 15 months (estimate = 0.03, SE = 0.02, 95% CI: [−0.01, 0.06]). Mediation analysis testing the indirect effect of material hardship showed a very small indirect effect between family income at 15 months and maternal depressive symptoms at 15 months via material hardship at 15 months (indirect effect = −0.004, 95% CI: [−0.009, −0.001]).

Material hardship at 15 months to mothers’ reports of destructive interparental conflict at 36 months via maternal depressive symptoms at 15 months

As shown in the second model of Figure 3 and in Table 3, results of the material hardship model predicting mothers’ reports of destructive interparental conflict at 36 months via maternal depressive symptoms at 15 months showed that material hardship at 15 months was linked with higher levels of maternal depressive symptoms at 15 months (estimate = 0.11, SE = 0.02, 95% CI: [0.08, 0.15]). However, maternal depressive symptoms at 15 months were not linked with mothers’ reports of destructive interparental conflict at 36 months (estimate = 0.02, SE = 0.02, 95% CI: [−0.02, 0.05]). Further, there was no direct link between material hardship at 15 months and mothers’ reports of destructive interparental conflict at 36 months (estimate = 0.02, SE = 0.02, 95% CI: [−0.01, 0.06]).

Material hardship at 15 months to fathers’ reports of destructive interparental conflict at 36 months via maternal depressive symptoms at 15 months

As shown in the third model of Figure 3 and Table 4, we replaced mothers’ reports of destructive interparental conflict at 36 months with fathers’ reports of destructive interparental conflict at 36 months to test the same material hardship models. Overall, results were nearly identical as those of the models using mothers’ reports of destructive interparental conflict. Specifically, the material hardship model predicting fathers’ reports of destructive interparental conflict at 36 months via maternal depressive symptoms at 15 months showed that material hardship at 15 months was linked with higher levels of maternal depressive symptoms at 15 months (estimate = 0.11, SE = 0.02, 95% CI: [0.08, 0.15]). Maternal depressive symptoms at 15 months were not linked with fathers’ reports of destructive interparental conflict at 36 months (estimate = −0.04, SE = 0.02, 95% CI: [−0.07, 0.00]). Further, there was no direct link between material hardship at 15 months and fathers’ reports of destructive interparental conflict at 36 months (estimate = 0.01, SE = 0.02, 95% CI: [−0.03, 0.04]).

Paternal model results

Family income at 15 months to paternal depressive symptoms at 15 months via material hardship at 15 months.

As shown in the first model of Figure 4 and in Table 2, results of the family income model predicting paternal depressive symptoms at 15 months via material hardship at 15 months showed no associations between family income at 15 months and material hardship at 15 months (estimate = −0.03, SE = 0.02, 95% CI: [−0.07, 0.00]). Material hardship at 15 months was associated with higher levels of paternal depressive symptoms at 15 months (estimate = 0.09, SE = 0.02, 95% CI: [0.06, 0.13]). Family income at 15 months was not directly linked with paternal depressive symptoms at 15 months (estimate = −0.02, SE = 0.02, 95% CI: [−0.05, 0.02]).

FIGURE 4.

Summary of all paternal models testing the associations between family income, material hardship, parental depressive symptoms, and destructive interparental conflict as informed by the family stress model.

Note. Solid line indicates parameter estimate for which the credible interval excludes a 0, suggesting that there is a 95% probability that the estimated value is not equal to 0 and lies within the limits of the credible interval. Dotted line indicates parameter estimate for which the credible interval includes a 0.

Material hardship at 15 months to mothers’ reports of destructive interparental conflict at 36 months via paternal depressive symptoms at 15 months

As demonstrated by the second model in Figure 4 and by Table 3, results of the material hardship model predicting mothers’ reports of destructive interparental conflict at 36 months via paternal depressive symptoms at 15 months showed that material hardship at 15 months predicted higher levels of paternal depressive symptoms at 15 months (estimate = 0.09, SE = 0.02, 95% CI: [0.06, 0.13]), which were subsequently linked with higher levels of mothers’ reports of destructive interparental conflict at 36 months (estimate = 0.10, SE = 0.02, 95% CI: [0.06, 0.13]). There was no direct link between material hardship at 15 months and mothers’ reports of destructive interparental conflict at 36 months (estimate = 0.03, SE = 0.02, 95% CI: [−0.01, 0.06]). Mediation analysis testing the indirect effect of paternal depressive symptoms showed a small indirect effect between material hardship at 15 months and mothers’ reports of destructive interparental conflict at 36 months via paternal depressive symptoms at 15 months (indirect effect = 0.01, 95% CI: [0.004, 0.014]).

Material hardship at 15 months to fathers’ reports of destructive interparental conflict at 36 months via paternal depressive symptoms at 15 months

As demonstrated by the third model in Figure 4 and by Table 4, results of the material hardship model predicting fathers’ reports of destructive interparental conflict at 36 months via paternal depressive symptoms at 15 months showed that material hardship at 15 months was linked with higher levels of paternal depressive symptoms at 15 months (estimate = 0.09, SE = 0.02, 95% CI: [0.05, 0.13]), which were subsequently linked with higher levels of fathers’ reports of destructive interparental conflict at 36 months (estimate = 0.21, SE = 0.02, 95% CI: [0.18, 0.25]). There was no direct link between material hardship at 15 months and fathers’ reports of destructive interparental conflict at 36 months (estimate = 0.01, SE = 0.02, 95% CI: [−0.02, 0.04]). Mediation analysis testing the indirect effect of paternal depressive symptoms showed again a small indirect effect between material hardship at 15 months and fathers’ reports of destructive interparental conflict at 36 months via paternal depressive symptoms at 15 months (indirect effect = 0.02, 95% CI: [0.011, 0.028]).

DISCUSSION

Using a large and racially diverse sample of two-parent families with high levels of economic disadvantage, the current study applied the FSM to investigate mechanisms linking economic insecurity to interparental conflict. The FSM argues that adverse economic events, including low family income, are associated with increased economic pressures mothers and fathers feel, which are then linked with higher levels of maternal and paternal depressive symptoms, respectively. Subsequently, higher levels of parental depressive symptoms are thought to contribute to higher levels of relationship strain such as destructive conflict between mothers and fathers, which is then linked with poor parenting that ultimately results in children’s maladjustments (Conger et al., 1992). The FSM has been tested and replicated with different samples, suggesting that the core tenants of the theory apply widely across diverse populations and contexts (Masarik & Conger, 2017). That said, there is still limited research using data from both mothers and fathers from socioeconomically disadvantaged contexts to test the FSM—a gap the current study fills by including BSF mothers and fathers (i.e., mothers and fathers who face economic precarity) in our models. In accordance with the paths proposed by the FSM, the current study specifically examined material hardship as a mediator between families’ household income and fathers’ and mothers’ depressive symptoms, which were also examined as mediators between families’ material hardships and couples’ destructive conflict behaviors.

Another important contribution of this study is the finding that material hardship was consistently linked with higher levels of destructive interparental conflict primarily through paternal depressive symptoms, above and beyond the effects of maternal depressive symptoms and whether we used mothers’ or fathers’ reports of destructive interparental conflict. That is, difficulties associated with making ends meet may be especially detrimental to fathers’ mental health functioning in its association with destructive interparental conflict. Overall, the material hardship models seemed to function more robustly than the family income models. This is consistent with prior evidence that income alone does not adequately capture families’ economic insecurity and that material hardship is as an important consumption-based poverty index tapping into daily struggles with paying utility bills, health insurance, and housing among other expenses (Gershoff et al., 2007; Ouellette et al., 2004; Zilanawala & Pilkauskas, 2012).

Material hardship as a mediator of family income and parental depression

Consistent with the FSM and shown in Figures 3 and 4, material hardship mediated the links between family income and maternal depressive symptoms, with a very small, indirect effect. We did not find the same mechanism for paternal depressive symptoms. Further, family income was not directly linked with either mothers’ or fathers’ depressive symptoms. Results of the study partially supported the first hypothesis derived from the FSM, with material hardship mediating the links between family income and maternal depressive symptoms. Family income had a small negative association with material hardship, which was then linked with higher levels of maternal depressive symptoms. This is consistent with prior research applying the FSM to test material hardship as a mediator in some of the family stress pathways involving family income and maternal depressive symptoms (Gershoff et al., 2007; Shelleby, 2018). Gershoff et al. (2007) used data from the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study—Kindergarten and found that material hardship mediated the association between family income and maternal stress (a latent variable including depressive symptoms, marital conflict, and parenting stress). Similarly, Shelleby (2018) used maternal data from the Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study to show that material hardship mediated the links between family income at the children’s births and when they were 1 year old and maternal depressive symptoms when the children were 3 years old. We did not find the same mechanism for fathers, as family income had no direct link with material hardship and thus no mediation between family income and paternal depressive symptoms via material hardship.

Our findings suggest that family income as mediated by material hardship affects mothers’ mental health more so than fathers’ mental health. This may be because mothers, many of whom are the primary caregivers (less than a quarter of the BSF mothers reported working), are more likely than fathers to assume domestic responsibilities, including caring for their children and managing household income and financial resources. Simultaneously, it is important to note that the indirect effect of material hardship in the maternal model was very small and close to zero, suggesting that processes linking family income with parental depressive symptoms may not be substantially different for mothers and fathers. Family income also was not associated with either parent’s depressive symptoms directly. Collectively, these findings suggest a ceiling effect of family income among this highly economically disadvantaged sample in which the majority of families earned an annual household income of less than $30,000. That is, there may have been a general lack of predictive power in the family income models, which may be stemming from the consistently low levels of income BSF families reported.

Parental depression as a mediator of material hardship and destructive conflict

Consistent with the FSM and shown in Figures 3 and 4, paternal depressive symptoms mediated the links between material hardship and both mothers’ and fathers’ reports of destructive interparental conflict. We did not find the same mechanism for mothers. Together, these study findings partially supported the second hypothesis derived from the FSM by showing that paternal depressive symptoms, but not maternal depressive symptoms, mediated the links between material hardship and destructive interparental conflict. Material hardship was associated with higher levels of depressive symptoms for both mothers and fathers, but only paternal depressive symptoms were linked with higher levels of destructive interparental conflict whether reported by mothers or fathers. That is, paternal depressive symptoms served as a mediator in both models—one in which mothers’ reports of destructive interparental conflict was used as the outcome and another in which fathers’ reports of destructive interparental conflict was used as the outcome. Our results support those of prior FSM studies with both majority White rural and racially diverse urban samples (Conger et al., 1990; Curran et al., 2021). For instance, Conger et al. (1990) showed that material hardship (although they call their measure “economic pressure”) arising from negative financial events of the Great Farm Crisis operated primarily through fathers’ hostility and lack of warmth to negatively impact couples’ relationship quality. Using a BSF sample of mothers and fathers, Curran et al. (2021) showed that paternal depressive symptoms, and not maternal depressive symptoms, were associated with higher levels of destructive conflict at 36 months as reported by both parents.

The breadwinner role has long been considered a defining feature of traditional fatherhood (Christiansen & Palkovitz, 2001). The breadwinner role is a central focus of how many men who live in poverty define their success as fathers (Edin & Nelson, 2013; Marsiglio & Roy, 2012). Yet, fulfilling the expectations of the breadwinner role may be particularly challenging for fathers with low income. The expectation is that men economically contribute to their families’ financial stability (Edin & Nelson, 2013), but fathers with low income often lack access to the employment opportunities and resources to be able to do so (Marsiglio & Roy, 2012). These challenges often arise from systemic barriers (e.g., structural racism, discriminatory policies) fathers with low income, many of whom are men of color, face (Lemmons & Johnson, 2019). Our results suggest that BSF fathers, most of whom were the primary breadwinners in their families (58.46% families in which fathers, but not mothers, were working for pay), may be more likely than mothers to feel stressed about not being able to alleviate their families’ material hardships, which may lead to experiencing higher levels of depressive symptoms that eventually manifest as destructive conflict behaviors in their couple relationships.

Contrary to what the FSM proposes, and as shown in Figures 3 and 4, our results showed no direct associations between material hardship and destructive interparental conflict. This suggest that material hardship primarily has an indirect effect, through fathers’ depressive symptoms, in its association with higher levels of destructive interparental conflict. Notably, our results can be interpreted to provide quantitative evidence for prior qualitative research documenting urban fathers’ lack of employment and financial support being factors contributing to relationship conflicts with mothers (Edin & Nelson, 2013; Edin & Kefalas, 2005).

Limitations and directions for future research

The current study has several limitations. The empirical evidence used to create pooled priors is limited in that the literature review focused on selected FSM articles (i.e., more recent and with similar samples). Although the FSM has been tested and replicated over 20 years, a meta-analysis has yet to be conducted. A meta-analysis produces effect sizes that could be built into Bayesian models. Future research would benefit from a meta-analysis that combines data from multiple FSM studies, especially those that focus on families from socioeconomically disadvantaged contexts. Furthermore, although we endeavored to use studies with similar samples as the BSF, children in some of the samples of the studies used for creating priors were older, and thus family processes may vary.

Specific to the definition and measurement of material hardship (which share similar qualities as “economic pressure” proposed by the FSM), while material hardship is understood to be a complementary poverty measure to family income, there is still limited consensus as to how material hardship should be defined (Heflin et al., 2009). One reason may be the lack of theoretical understanding as to how individual indicators of material hardship relate to each other (Heflin et al., 2009). Researchers have suggested using a model of material hardship that includes dimensions of health, bill paying, housing, and food (Heflin et al., 2009). Related to this suggestion, BSF data were missing food insecurity, an important index that captures families’ food needs. Additional research with an improved or empirically validated material hardship measure is needed to better understand material hardship’s impact on family processes. Consistent with prior measurement work, future research may consider examining separate dimensions (i.e., health, food, bill paying, housing) of material hardship (Heflin et al., 2009) and see how each dimension relates to the FSM proposed variables in families with low income. Further, although our measure of material hardship included medical insurance, families may forgo health care out of concern that they may need to pay a portion of their medical expenses. Future research on material hardship in families with low income can examine this possibility.

Given that we tested mediation within a regression framework, outcomes of interests could not be examined simultaneously in the same model. This, generally speaking, resulted in running separate models for mothers and fathers and thus not being able to make direct comparisons between the two groups for some of the key paths. Future research may consider running mediation models, such as structural equation models (SEM), in which more than one outcome can be entered into a single model and variables from mothers and fathers can be jointly tested more consistently. Such SEM models may better reflect paths and dyadic relations originally proposed in the FSM and would allow for statistically assessing and drawing conclusions about whether there are equivalent or different paths for mothers and fathers.

Results cannot be generalized to all couples with low income because BSF families volunteered to participate in a relationship skills education intervention. BSF families were likely interested in strengthening their relationships. Use of population-level, nationally representative data is needed to advance future research testing the FSM. Relatedly, future research with BSF may examine race as a potential moderator, and, more broadly, additional research with samples similar to the BSF is needed to better understand the mediating role of material hardship between income poverty and parental mental health.