Abstract

Objective

There is a recognised need to strengthen capacity in the nutrition in emergencies sector and for greater clarity on the role of emergency nutritionists and the skills they require. Competency frameworks are an important tool for human resource development and have been developed for several other humanitarian sectors. We therefore developed a technical competency framework for practitioners in nutrition in emergencies.

Design

Existing competency frameworks were reviewed and interviews conducted to explore methods used in developing competency frameworks for other sectors. Competencies were identified through interviews with field experts, feedback from course trainees, academic course content and job specifications. Competencies were then categorised and behavioural indicators developed for each. The draft framework was then reviewed by members of the Global Nutrition Cluster and modified in an iterative process.

Setting

Global.

Subjects

Not applicable.

Results

A wide range of competencies were identified as essential for nutritionists working in emergencies, covering technical skills and general core competencies. The proposed framework contains twenty competency areas with 161 behavioural indicators categorised into three levels, corresponding to the requirements of progressively more senior roles. Many of the competencies are common across development and emergency nutrition.

Conclusions

The proposed technical competency framework should prove to be a valuable tool in creating standards within the sector and promoting effective capacity strengthening and professionalisation. Continued research is needed to validate the framework, optimise methods for assessment, develop approaches to integrate it within the sector and measure its impact on performance.

Keywords: Capacity development, Competency framework, Human resources, Emergencies, Disasters

Over the past 6 years, the humanitarian system has undergone a series of major reforms in an attempt to address inadequacies that have hindered effective response( 1 ). Climate change, ongoing conflict and global economic recession are all contributing to the increasing frequency of humanitarian emergencies worldwide( 2 ). The need to strengthen the system to manage and respond to these crises remains a priority. A key aspect of the humanitarian reform process has involved developing capacity. The 2005 Humanitarian Response Review noted: ‘there are simply not enough people with the right experience available quickly’( 1 ). In response, there has been increased investment in training and professional development for existing and future cadres of humanitarian staff.

As part of this process, a number of international organisations have debated the value of professionalising the humanitarian sector( 3 ). It has been argued that a recognised set of standards for humanitarian staff would improve performance and promote quality and accountability( 4 ). The result has been the development of a number of competency frameworks, which are increasingly being used to measure ability and to structure training. The concept of competencies emerged during the early 1980s as a response to the need for improved performance in the business sector. Competencies are defined as the behaviours and technical attributes that individuals must have, or acquire, to perform effectively in a particular role( 5 ). The benefits of adopting competency-based training and development in the humanitarian sector were described by People in Aid: ‘competency frameworks provide a potentially powerful way of better ensuring that recruitment choices and the development of people fits the roles they will fill. The hope is that by making clear the ways people are expected to behave and in which they will be held to account for their behaviours, individual performance will improve, followed by increased team and organisational effectiveness’( 6 ).

To date, members of the Consortium of British Humanitarian Agencies have agreed a core humanitarian competency framework( 7 ) and several ‘technical’ competency frameworks have also been produced for different sectors( 8 , 9 ). The core competencies are considered to be the foundation set of skills for effective national and international humanitarian staff, with the technical competency frameworks providing benchmarks for ability and performance in specialist areas.

Outside the immediate humanitarian domain, several livelihoods, nutrition, dietetics and public health technical competency frameworks have been recently developed or are in the process of development( 10 – 15 ). Work is also ongoing that could, in time, allow for the international professional recognition of public health nutritionists( 16 ). The importance of workforce development for the successful implementation of nutrition policy objectives, in both high- and low-income countries, is being increasingly recognised( 17 , 18 ).

However, no technical competency framework had been developed to describe the skills required for emergency nutrition preparedness, response and recovery; a sector within the humanitarian system that is experiencing serious gaps in capacity, having faced a notable lack of skilled staff for many years( 19 ). Emergencies put affected populations at a much higher risk of malnutrition and disease. In order to prevent malnutrition in these contexts, and to treat cases that do arise, a cadre of nutritionists are needed at both national and international level who can respond quickly and effectively to emergencies. The recent establishment of the Nutrition in Emergencies Regional Training Initiative, which is intended to provide sustainable, high-quality training in nutrition in emergencies (NIE), highlighted the need for a more detailed examination of the role of emergency nutritionists and the skills required( 20 ).

The competencies required of a nutritionist working in emergencies differ between agencies and contexts, and the content of training courses varies significantly. In an attempt to develop a technical competency framework for NIE that is both globally applicable and also addresses the diversity of operational requirements, we worked with key stakeholders in the sector. In the present paper we document the process of developing the proposed framework and discuss some of the potential opportunities and challenges to its implementation as a tool to strengthen human resource capacity.

Methods

Review of existing literature on humanitarian competencies

A review of the literature relating to humanitarian competency frameworks was undertaken using the PubMed and Web of Knowledge electronic databases. A search was also conducted in the resources section of the Global Nutrition Cluster (GNC) website( 21 ) and requests for information and existing frameworks were sent to operational agencies.

Interviews were conducted with senior staff from two sectors that have implemented a competency-based approach for training and assessment (Humanitarian Logistics and Child Protection in Emergencies (CPIE)). Interviewees were purposefully chosen for their involvement in the development and regular use of the frameworks. Additional frameworks were collated from humanitarian organisations and reviewed. The structure for the NIE framework was then chosen based on the merits and uses of the existing frameworks. This process was also used to ascertain how the NIE competency framework could be used as part of recruitment, assessment and training.

Construction of the competency framework

The key features of a competency framework were identified from the review of existing frameworks (see Table 1) and, using these as a guide, the NIE competencies identified were categorised as either technical or core. Core professional competencies are regarded as those that are needed to function effectively in a work environment and include behaviours such as the ability to communicate and work effectively with others, while core humanitarian competencies include behaviours that are required for humanitarian work, such as the application of humanitarian principles. Competencies that already feature in the existing core humanitarian frameworks were removed to avoid replication. The competencies were then assigned to a technical domain and, where necessary, re-formulated into a behavioural indicator. Expressing competencies in the form of behavioural indicators facilitates the use of a framework as a tool for assessing ability and performance. This was done using a revised version of Bloom's taxonomy of learning behaviour as a guide( 22 ). Each behavioural indicator was then allocated to one of three levels, corresponding to progressive seniority within the sector (see Table 2). This allocation was done using NIE job specifications for posts requiring varying levels of professional experience.

Table 1.

Competency frameworks in related sectors

| Framework name | Author, date | Competency type |

|---|---|---|

| Child Protection in Emergencies (CPIE) | Save the Children, 2010( 8 ) | Core and Technical |

| Certification in Humanitarian Logistics (CHL) Competence Model | Fritz Institute and Chartered Institute of Logistics and Transport, 2005( 28 ) | Core and Technical |

| Livelihoods | Department For International Development, 2011( 12 ) | Core and Technical |

| Core Humanitarian Competencies Framework | Consortium of British Humanitarian Agencies & People in Aid, 2010( 7 ) | Core |

| Enhanced Learning and Research for Humanitarian Assistance | Walker and Russ, 2010( 3 ) | Core |

| UN Competency Development – A Practical Guide (Version 1·0) | UN Office of Human Resources Management, 2010( 29 ) | Core and Managerial |

Table 2.

Proposed structure for nutrition in emergencies competency framework

| Competency domain | Level 1 behaviour | Level 2 behaviour | Level 3 behaviour |

|---|---|---|---|

| Descriptive name of competency domain | Required for field-level workers | Required for team coordinators/supervisors | Required for country and international level technical staff |

Identification of nutrition in emergencies competencies

The identification of NIE competencies was designed to be as comprehensive as possible, and consisted of four stages. First, existing competency frameworks, course curricula and emergency nutrition job specifications were reviewed and relevant competencies extracted. Frameworks, courses and job specifications were included only if they featured an aspect of emergency nutrition.

Second, semi-structured interviews were conducted with a convenience sample of ‘field experts’ working for humanitarian organisations. The sample consisted of three independent consultants, three employees from UN agencies and three employees from international non-governmental organisations (NGO). The interview questions were designed to explore which competencies were viewed as essential for an emergency nutritionist and also those that interviewees perceived to be commonly limiting in the field. Where necessary, questions were open-ended to encourage interviewees to expand on the issue. Interviews were conducted by telephone due to the geographical spread of participants and lasted approximately 45 min.

Third, participants from NIE courses held in Uganda, Thailand and Lebanon in 2010 and 2011 were contacted to identify which skills they felt were essential for their roles in emergency nutrition( 20 ). Finally, the compiled list of competencies was reviewed by members of the Capacity Development Working Group of the Global Nutrition Cluster (GNC-CDWG) during the second half of 2011.

Results

Existing humanitarian competency frameworks

Six humanitarian competency frameworks were identified and reviewed (see Table 1). Interviews were then conducted with two key informants from the Humanitarian Logistics and CPIE clusters.

From these interviews, and the review of the frameworks, three key features were identified. (i) Competencies were categorised as either core or technical, with a number of frameworks focusing exclusively on core competencies and others on both core and technical. (ii) All the frameworks reviewed organise the competencies into domains. Within these domains, most frameworks then outline specific behaviours or examples of how to successfully demonstrate skills relating to each domain. The Humanitarian Logistics framework includes key learning points within each domain to ensure complete coverage of required skills. (iii) Most of the frameworks have been further developed to take into account progressive levels of learning, with each level featuring a set of behavioural indicators.

Structure for the nutrition in emergencies framework

This review of the existing competency frameworks and their key features led to the proposed structure for the NIE framework shown in Table 2. The categorisation of competencies and assigned behavioural indicators with progressive additive levels provides clarity regarding the skills required and gives a clear vision of career progression. This structure is based closely on the CPIE framework.

The CPIE framework includes core humanitarian competencies which are based on those previously identified by the Consortium of British Humanitarian Agencies. We recognise that these core competencies are essential for all humanitarian workers, and so the NIE framework is designed to be used in conjunction with these.

Extraction, compilation and selection of competencies

Seven courses that either focus on NIE or include relevant components were identified and included for review. Courses ranged from master's degree level, to short, non-accredited training.

A total of fifty-six NIE job specifications were identified with roles ranging from graduate entry level to those requiring over 10 years’ experience. Job titles included nutrition advisers, coordinators, programme managers and chiefs of health and nutrition. The hiring organisations consisted of international humanitarian NGO and UN agencies, with thirty-six and twenty job specifications, respectively.

Full interviews were conducted with eight NIE experts; a further two responded to selected questions by email. All the interviewees work in international emergency nutrition and have between 8 and 23 years’ experience working across Africa, Asia, Europe and America.

Feedback from twenty-five NIE training course participants in Thailand, Lebanon and Uganda was collected. Participants were staff working for governmental departments in health and nutrition and international NGO, and came from a wide range of countries in Asia, Africa and elsewhere. The participants were asked to list the skills they used for their roles in emergency nutrition and specifically those for which they felt they required more training.

Once collected, the competencies from each method were assigned to a domain (e.g. preparation of F-100, a therapeutic treatment for acute malnutrition, would be assigned to ‘management of acute malnutrition’). These competency domains are shown in Table 3. Examining the tables reveals that some domains which are identified as essential in job specifications and by key informants do not feature in the training course curricula. In general, the technical nutritional competencies are covered, with the main disparity in the more general competencies such as leadership, communication and policy development.

Table 3.

Competency domains identified from course curricula, job specifications and key informant interviews (listed alphabetically)

| Competency domain | Course curricula | Job specifications | Field experts and NIE course participants |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ability to live/work in changing & insecure environment | • | ||

| Advocacy | • | • | • |

| Analytical skills | • | • | • |

| Behavioural change communication | • | • | |

| Capacity development | • | ||

| Emergency preparedness | • | • | • |

| Financial management | • | ||

| Food assistance | • | • | |

| Food security and livelihoods | • | • | • |

| Health and disease assessment | • | • | • |

| Human resource management/recruitment | • | • | |

| Humanitarian system | • | • | • |

| Infant feeding in emergencies | • | • | • |

| Interpersonal and communication | • | • | |

| Keeping knowledge current | • | • | • |

| Leadership | • | • | |

| Logistics | • | ||

| Management of malnutrition | • | • | • |

| Measuring malnutrition: surveys | • | • | • |

| Measuring malnutrition: rapid assessments | • | • | • |

| Micronutrient deficiencies | • | • | • |

| Monitoring and evaluation | • | • | • |

| Needs assessment | • | ||

| Partner management & coordination | • | ||

| Policy development | • | ||

| Prevention of malnutrition | • | • | |

| Programme set up | • | • | |

| Reporting | • | • | |

| Sector integration | • | ||

| Surveillance/early warning | • | • | • |

| Technical writing | • |

NIE, nutrition in emergencies.

Filled circles indicate the inclusion of the competency domain.

To avoid duplication, any competencies which were already included within the CPIE core competency framework were extracted so the NIE framework contains only technical competencies. That is not to suggest that these core areas should be ignored; indeed, the NIE technical competency framework should be used alongside the existing core competency framework, ensuring all essential competencies are considered.

In terms of gaps in skills, the main theme that emerged from the interviews was management and leadership, which was mentioned by the majority of respondents. One interviewee stated: ‘Management and leadership skills are not usually taught, yet once staff reach a certain level they are expected to possess these skills, which is often not the case’.

Other limiting competencies mentioned include: understanding and adhering to guidelines, analysing data, report writing, training others, working well with different teams, strategy writing, coordination, adapting programmes to suit the specific context, communicating with media, funding applications, and knowing where to find resources. In addition, skills related to the integration of community management of acute malnutrition into health systems, prevention and treatment of malnutrition, and social and behavioural change were noted as lacking among NIE personnel.

The next step was to develop behavioural indicators for each competency within the technical domains that had been identified, using Bloom's taxonomy action verbs. Once these were developed the whole framework was reviewed by members of the GNC-CDWG and the framework was then revised based on their feedback. The full competency framework including behavioural indicators is shown in Table 4. The proposed framework contains twenty competency areas with 161 behavioural indicators categorised into three levels.

Table 4.

Technical competency framework for nutrition in emergencies practitioners

| Competency domain | Level 1 behaviours | Level 2 behaviours | Level 3 behaviours |

|---|---|---|---|

| Humanitarian system & standards | Demonstrates awareness of relevant sphere or organisation-specific standards and indicators | Implements programmes in line with humanitarian standardsAble to describe responsibilities of different organisations within the humanitarian response | Designs programme strategies that are coherent with humanitarian standards |

| Coordination | Identifies relevant local stakeholders, including representatives from the beneficiary population, for inclusion in nutrition programme coordination activitiesAssists in compiling nutrition activity inputs for proposalsAttends and actively participates in all relevant meetingsEffectively communicates with relevant stakeholders | Disseminates information to all relevant local and national stakeholders on a timely basisDevelops good relations with other nutrition actors and other sectors | Initiates contacts and effectively communicates with all relevant local, national and global stakeholdersWorks towards integration, coordination and harmonisation of programme tools and approaches with stakeholdersWorks effectively with stakeholders on development of strategies and proposals |

| Measuring malnutrition: rapid assessments | Demonstrates ability to participate in rapid assessments of the nutritional situation | Organises assessment teams and ensures adherence to guidelinesConducts rapid assessments in line with guidelines and protocols | Plans, organises and leads nutritional assessmentsProvides technical support to teams where needed |

| Measuring malnutrition: surveys | Collects good-quality data (anthropometric and non-anthropometric)Correctly uses growth charts and malnutrition cut-offsObtains secondary data and identifies gapsConducts data entry using spreadsheet or statistical software | Demonstrates understanding of different survey designsUnderstands the use of both quantitative and qualitative methodsTrains teams to effectively use quantitative and qualitative methodsSupervises surveys and ensures data qualityConducts data analysis using statistical softwareConducts full situation analyses, triangulates data and prepares good-quality survey reportsDemonstrates understanding of the cultural determinants of malnutritionUses appropriate conceptual frameworks for analysis | Assesses all available information to select appropriate survey designs for the contextDevelops context-specific strategies for measuring malnutritionProvides technical leadership, coordination and support for survey activitiesCollates, analyses, interprets and disseminates nutrition information |

| Health and disease assessment: the link with nutrition | Demonstrates awareness of nutrition–disease interactions and importance of health and WASH interventions for nutritionImplements appropriate measures to reduce risk of communicable disease transmission | Ensures nutrition–disease relationship is considered in all nutrition programmesInitiates and conducts health assessments where appropriate | Actively engages with health, WASH and other relevant sectorsDesigns appropriate interventions accounting for disease status of target population (e.g. HIV/AIDS, malaria, chronic diseases) |

| Food security and livelihoods assessment | Demonstrates ability to participate in food security assessmentsDemonstrates understanding of the role of food security in preventing malnutrition | Demonstrates understanding of livelihoods and household economy analysis methodsCorrectly uses livelihoods framework in causal analysisEnsures good communication links with food security staffDemonstrates familiarity with Integrated Phase Classification | Initiates food security and livelihoods assessments where appropriateActively integrates nutrition and food security sector activities |

| Surveillance and early warning | Correctly collects and records the different types of data required for the surveillance system | Conducts appropriate trend analysisUnderstands the importance of non-anthropometric data (e.g. disease incidence)Sources both primary data and secondary data (e.g. from routine crop assessment reports) | Designs, implements and follows up surveillance and early warning programmesProvides guidance on use of indicators for monitoring |

| Design and implementation of nutrition programmes | Effectively implements nutrition programmes under guidance of programme managerDemonstrates awareness of programme objectivesDemonstrates awareness of both preventive and curative interventions | Manages nutrition programmes in line with humanitarian standards and documents any deviationsManages programmes with long-term transitions in mindMonitors programme performanceInterprets results or analyses data to design or improve existing programmes appropriatelyDemonstrates understanding of the importance of cultural considerations for successful programme designAdapts programmes to local contextsAssesses local capacity and ensures programmes are integrated into existing health systems where appropriateEnsures projects are implemented in accordance with set time framesContributes to development of project proposals | Develops new project proposals building on lessons learned from previous programme experiencesOversees design and implementation of nutrition programmes, ensuring all are in line with humanitarian standards and documents any deviationsAnalyses nutrition programmes on an ongoing basis and proposes and implements improvementsDesigns programmes with awareness of long-term transitionsEnsures other programmes and sectors are considered when designing the programme |

| GFD and cash/voucher programmes | Demonstrates ability to participate in GFD and/or cash/voucher distributionsDemonstrates awareness of potential challenges and necessary precautions | Plans and manages GFD or cash/voucher distributionsCalculates nutritional content of rations and suggests suitable alterations where necessaryConducts market analysisDemonstrates understanding of the implications of conditional cash transfers | Demonstrates awareness of different food assistance strategies and reasons for choosing themDesigns appropriate food assistance programmes |

| Blanket supplementary feeding | Demonstrates ability to participate in BSFP | Plans and manages BSFP | Designs appropriate programmes and strategies to prevent malnutrition |

| Management of moderate and severe acute malnutrition | Demonstrates ability to participate in active screening for targeted groupsApplies standard assessment toolsExecutes monitoring activities for CMAMAdheres to protocols for in/outpatient treatmentDelivers appropriate nutrition messages to carers/mothers at OTP/TSFP sites | Maintains and supports CMAM programme activities (TSFP/OTP/SC)Integrates CMAM into existing health systems where appropriateProvides leadership on CMAM approachesProvides technical assistance and support to all programme staffEnsures all staff adhere to protocolsMaintains and shares programme-monitoring database | Assesses suitability for integration of CMAM programmes into health systems where appropriateDevelops implementation strategy and effectively manages the implementation of CMAM programmesDesigns and implements CMAM monitoring toolsProvides technical assistance to programme managers and government departmentsFacilitates the development and scheduling of outreach activitiesConducts regular field visits |

| Micronutrient deficiencies | Correctly identifies micronutrient deficiencies from clinical signsAppropriately treats deficiencies or refers to appropriate health staffDemonstrates awareness of possible interventions for preventing micronutrient malnutrition including supplementation, fortification and diet diversification | Builds micronutrient deficiency assessments into surveys when appropriateProposes suitable interventions to prevent deficienciesConducts nutritional analysis of food assistance to determine whether all micronutrient needs are met | Designs interventions to treat and prevent micronutrient deficienciesProvides technical support to staff when necessary |

| IYCF-E | Demonstrates understanding of operational guidance on IYCF-EProvides support for breast-feedingTakes appropriate measures to minimise risks of artificial feeding | Provides technical guidance to teamsEnsures all staff adhere to criteria set out in the operational guidance on IYCF-E | Ensures all actions of staff are contributing to supporting breast-feeding and minimising risks of artificial feedingEnsures logisticians are aware that they should adhere to the guidelines on distribution and use of breast-milk substitutes and other milk products |

| BCC | Performs BCC sessions with beneficiaries | Oversees BCC activities | Designs and implements BCC programmes |

| Emergency preparedness | Conducts activities outlined in emergency preparedness planInvolves communities in preparedness activitiesDemonstrates understanding of objectives of emergency preparedness | Identifies potential disasters for inclusion in preparedness planAssesses populations to identify at risk groupsIdentifies activities to mitigate risk and ensure nutrition response is timely and appropriateUses early warning systems and projections | Designs, develops and oversees implementation of emergency preparedness planFacilitates links between emergency response, DRR and development teamsUses DRR frameworks to identify potential impact of disasters on nutritional status |

| Logistics | Follows system for monitoring stock levels and reporting procurement needs | Develops procurement plans and liaises with logisticians | Develops strategic procurement plans well in advance and liaises with logisticians, ensuring all details and time lines are understood |

| M&E | Conducts data collection for key nutritional indicatorsParticipates in analysis of dataConducts the M&E work planSupports programme evaluations | Develops M&E framework/work plan in line with existing programmesAdapts M&E system to local contextEnsures strong monitoring systems are in place that collect data for key nutrition indicatorsEnsures all data are analysed, reviewed and responded to on an ongoing basis | Designs and implements strong M&E systemsEnsures effective supervisory mechanisms are in placeEvaluates programmes on a regular basis and adapts them in line with findings |

| Advocacy and communication | Communicates with relevant stakeholders to convey nutrition messages | Communicates effectively with government, media and other organisationsDemonstrates ability to independently structure and write relevant, clear and precise reports in different formats and for different audiencesProvides inputs into policy development | Proactive in communicating nutrition agenda with all relevant stakeholdersOversees all communication ensuring appropriate messages are being conveyedDevelops advocacy strategies to influence policy |

| Reporting | Reports accurately and in a timely mannerWrites in a clear and concise manner, providing all required information | Compiles and verifies nutrition reportsClearly presents data, using appropriate graphs and tablesSubmits good-quality narrative and financial reports in a timely manner | Submits high-quality reports, both narrative and financial, in a timely manner to internal and external partiesTakes responsibility for ensuring a regular reporting system is in place |

| Capacity development and training | Identifies areas in need of strengtheningDelivers basic training to teams of national staff | Assesses training needs of nutrition staffDesigns, delivers and supports staff training | Liaises with appropriate authorities to develop capacity building plan for national staffDesigns training materials and delivers and supports staff training at all levels including training of trainersProvides mentoring |

GFD, general food distribution; IYCF-E, infant and young child feeding in emergencies; BCC, behavioural change communication; M&E, monitoring and evaluation; WASH, water, sanitation and hygiene; BSFP, blanket supplementary feeding programmes; CMAM, community-based management of acute malnutrition; OTP, outpatient treatment programme; TSFP, targeted supplementary feeding programme; SC, stabilisation centre; DRR, disaster risk reduction.

Application of the nutrition in emergencies competency framework

Across the sectors reviewed, competency frameworks are used as a basis for recruitment, development of training and for professional development. From the interviews with CPIE staff, a more detailed overview of the processes involved in applying a competency framework emerged.

Recruitment

The CPIE framework is used to create job profiles which define the key competencies required for a role and the necessary level of skill. Once a profile has been created it is used to form a job description and as a reference against which to assess candidate suitability. Recruitment assessment methods include scenario questions, observation, and role play in group assessments. This improves recruitment processes, ensuring that the selected individual has all the competencies essential for the role. Those with a lack of formal academic qualifications, such as a relevant BSc, MSc or professional training certificate, are not necessarily excluded in this process as the essence of a competency-based approach is that individuals are assessed on skills and attributes that may have been gained through experience or personal development.

Using the example of a Nutrition Coordinator, an example job profile was created using the NIE competency framework and is shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

An example job profile for a Nutrition Coordinator

| Competency | Minimum required level |

|---|---|

| Coordination | 3 |

| Communication | 3 |

| CMAM | 3 |

| Surveys/data collection | 3 |

| Reporting | 2 |

| Humanitarian system | 3 |

| Capacity development | 2 |

| Leadership | 2 |

CMAM, community-based management of acute malnutrition.

Note: This example is purely illustrative, there may be additional competencies required for the role of a nutrition coordinator in different contexts.

Training

The framework can also be used as a reference from which training is developed with the indicators relating to learning objectives, thereby standardising training courses across the sector. Competency-based training naturally leads on to competency-based assessment methods. In studies on assessment methods from the medical sector, it has been shown that in addition to standard essay and exam questions, assessing technical and behavioural competencies through observation of simulated situations is a valid method( 23 ). This approach facilitates the assessment of a person's behaviours such as decision-making capacity in addition to technical competencies.

Professional development

The framework can also be a tool for professional development and continuous learning. Staff can use the framework as a self-assessment tool, grading themselves for each competency and identifying areas which would benefit from further development. The competency areas in which they score lower, or areas which they would like to develop, can then be focused upon, with the behavioural indicators providing clear examples of what is required to attain each level.

Discussion

In the present paper we have proposed the structure and contents for a competency framework for practitioners in NIE and described how it could be used to improve staff recruitment, assessment and professional development. We have also extracted and synthesised competencies and developed behavioural indicators for each. The framework has since been adopted for preliminary use by the international NGO Concern Worldwide, World Vision, Valid International and International Medical Corps. This is an important initial step to developing a competency-based approach to human resource development for emergency nutrition practitioners, and the framework should provide a valuable tool for strengthening capacity within the sector.

The benefits of a competency-based approach have been increasingly studied and discussed, with the medical sector investing heavily in research in this area. The key benefits that have been recognised include the introduction of transparent standards and increased public accountability. The standardisation of training and provision of a clear framework also encourage learning and professional development( 24 ). In other humanitarian sectors it is felt that the introduction of a competency-based approach improves recruitment processes and is viewed as having been beneficial in developing capacity within the sector (K Bisaro, personal communication, 2011).

However, the approach is not without its criticisms and there are recognised limitations, including an increased administrative burden and possibility of a focus on achieving acceptable minimum standards rather than the best that is possible. Despite these limitations, competency-based learning is now dominant at most stages of medical training in high-income countries( 25 ).

Regardless of how comprehensive and well-constructed a framework is, its success is contingent on gaining widespread acceptance and ensuring effective implementation. A key lesson learned within the medical sector is that there needs to be a clear implementation strategy from the outset( 25 ). Through the present research, we have explored the three main ways in which the framework may be used – for recruitment, training and professional development – based on the approaches described within the CPIE competency framework( 8 ). However, further work is required to explore the specific methods for implementation and challenges faced. For the NIE framework to be successful, it is important that we continue to learn from other humanitarian sectors that have engaged in this process.

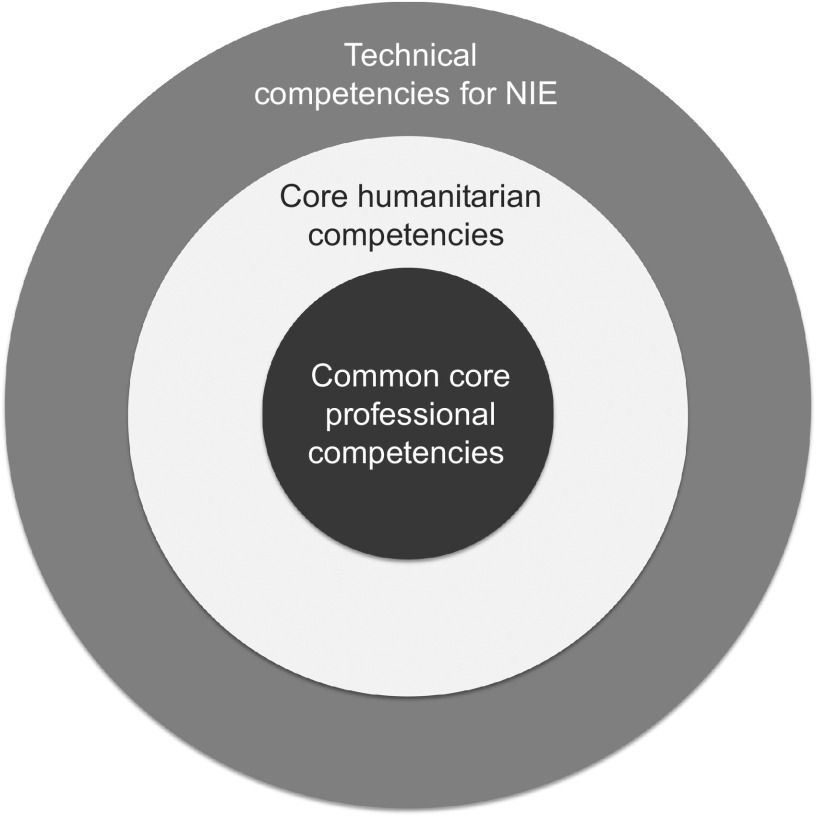

The competencies identified as essential for any individual working within NIE are diverse, encompassing common core competencies, such as communication and teamwork; humanitarian competencies essential to all humanitarian workers, such as knowledge and application of humanitarian system and standards; and nutrition specific technical areas, such as identification of micronutrient deficiencies. This leads to a layered approach to building a competency framework, which is based on the CPIE framework, and is shown in Fig. 1 ( 8 ).

Fig. 1.

The layered approach to building core professional, core humanitarian and technical competencies for nutrition in emergencies (NIE)

When comparing the competencies identified in Table 3, we can see a clear difference between what was identified as essential from job specifications and interviews and what is currently being taught in the academic and training courses we reviewed that focused on NIE. While the majority of the technical skills are covered, the main difference lies in the more general competencies. This is further supported through the findings from the interviews, where many of the same competencies are regarded as limiting effectiveness in the field, with seven interviewed experts commenting on the lack of leadership and management training in particular.

It may seem obvious that general core competencies are an important part of any role, yet this research has found that many are sorely neglected when it comes to training and were noted as limiting effectiveness in the field. So, our findings are that not only is there a lack of national and international nutritionists who can be deployed in response to emergencies, but those who are available may lack some of the essential competencies required to perform effectively. This was evident in a self-assessment of general nutrition capacity in the twenty countries with the highest global burden of undernutrition, where the main weaknesses were found to be in the areas of management and training( 26 ).

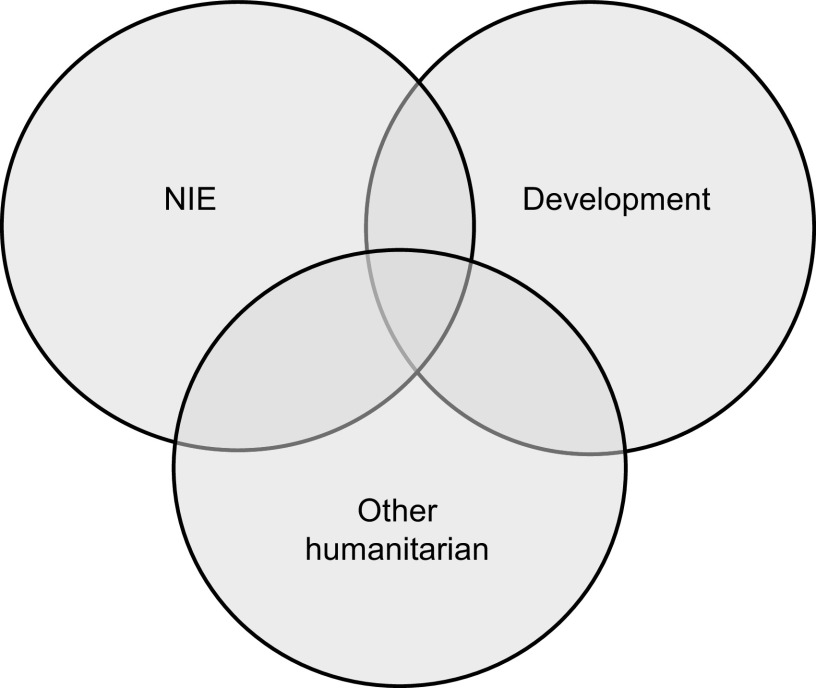

It has been noted that there are many important commonalities between development and emergency nutrition, and while developing the NIE framework it became apparent that many of the required competencies are not specific to emergency nutrition but overlap with disaster preparedness, recovery and long-term development work( 19 ). There is also strong overlap with other humanitarian sectors such as food security and logistics. For example, data collection and surveys is a competency area required by both emergency and non-emergency nutritionists; however, in an emergency there are additional specific skills and behaviours required relating to data collection that differ from those required in a non-emergency situation.

A similar overlap was also found by the developers of the child protection framework, which led them to separate the competencies into three areas: (i) core humanitarian; (ii) general child protection; and (iii) emergency-specific competencies( 8 ). This approach allows those who come from other professional backgrounds to identify the competencies they already possess that are included in the framework, thereby encouraging those in general nutrition or other sectors such as food security or livelihoods to undertake specific training to build those competencies required for working in emergency nutrition.

Many situations fluctuate in and out of crisis so that ‘development’ nutritionists who are running existing programmes are required to respond to an emergency. As highlighted by O'Dempsey and Munlow: ‘a lack of definition as to what constitutes a humanitarian emergency and the absence of rules of engagement of NGOs and donors further complicates the problem’( 27 ).

This then begs the question of whether it is appropriate to develop a separate competency framework for NIE when the required skills are so clearly interlinked with development work (Fig. 2). While there is an undoubted need to strengthen nutrition capacity in both development and emergency contexts, nevertheless there is a set of skills and knowledge that is unique to emergencies. In addition, the mechanisms by which staff are recruited, assessed and supported usually differ between the development and emergency sectors.

Fig. 2.

The overlap of competencies between nutrition in emergencies (NIE) and other sectors

Limitations

Although every effort has been made to identify all essential competencies, the list may not be exhaustive due to the various limitations of the present research. Some relevant documents may be held by agencies and not be in the public domain. It is also noted that the competencies highlighted through expert interviews are likely to have been biased towards each individual's area of expertise and reflect international rather than national perspectives. Ideally a larger sample of field experts and national staff would have been included, with experts also included from government departments, training institutions, donor organisations and other NGO (national and international).

Some competency areas have gaps due to a lack of available information and this may or may not reflect the actual need for expertise in these areas of work. Areas like social and behavioural change and emergency preparedness are often neglected within job specifications and course content, and this is reflected in the framework.

Conclusion

The move to a competency-based approach is a logical step to strengthen the NIE sector and build human resource capacity. However, the competency framework proposed here will require further review involving a wider range of stakeholders that includes beneficiary populations, in order to encourage sector-wide adoption and use. The competency approach has already been adopted by the logistics and child protection sectors and is perceived to be beneficial, although formal evaluations are still required. It is therefore essential that indicators for monitoring and evaluating the use of competency frameworks are defined in order to build an evidence base on their use not just within NIE, but within the humanitarian sector as a whole.

Acknowledgements

Sources of funding: This work was partly funded by a grant from the US Agency for International Development/Office of US Foreign Disaster Assistance. The Office of US Foreign Disaster Assistance had no role in the design, analysis or writing of this article. Conflicts of interest: There are no conflicts of interest. Ethics: Ethical approval was not required for this study. Authors’ contributions: J.M. conducted the data collection and wrote the first draft. C.E., K.G., C.A. and A.W. reviewed and revised the competency framework. A.P., C.D. and A.S. supervised the study and revised the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

References

- 1. Adinolfi C, Bassiouni DS, Lauritzsen HF et al. (2005) Humanitarian Response Review. New York and Geneva: UN. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Economic and Social Council (2012) Strengthening the Coordination of Emergency Humanitarian Assistance of the United Nations (E/2011/L.33). New York: UN. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Walker P & Russ C (2010) Professionalising the Humanitarian Sector: A Scoping Study. London: Enhancing Learning and Research for Humanitarian Assistance. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Walker P, Hein K, Russ C et al. (2010) A blueprint for professionalizing humanitarian assistance. Health Aff (Millwood) 29, 2223–2230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development (2012) Competence and Competency Frameworks: Resource Summary. http://www.cipd.co.uk/hr-resources/factsheets/competence-competency-frameworks.aspx (accessed January 2013).

- 6. Swords S (2007) Behaviours which lead to effective performance in humanitarian response. A review of the use and effectiveness of competency frameworks within the Humanitarian Sector. People in Aid, June 2007. http://www.ecbproject.org/resources/library/21-behaviours-which-lead-to-effective-performance-in-humanitarian-response (accessed September 2013).

- 7. Consortium of British Humanitarian Agencies (2012) Core Humanitarian Competencies Framework. http://www.thecbha.org/media/website/file/Competencies_Framework_2012_colour.pdf (accessed September 2013).

- 8. Child Protection Working Group (2010) Child Protection in Emergencies (CPIE) Competency Framework. http://resourcecentre.savethechildren.se/node/5656 (accessed May 2013).

- 9. Humanitarian Logistics Association (2009) Professionalisation of Humanitarian Supply and Logistics. Corby, UK: HLA. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ash S, Dowding K & Phillips S (2011) Mixed methods research approach to the development and review of competency standards for dietitians. Nutr Diet 68, 305–315. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Calhoun JG, Ramiah K, Weist EM et al. (2008) Development of a core competency model for the master of public health degree. Am J Public Health 98, 1598–1607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Department for International Development (2011) Livelihoods technical competency framework. https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/214067/technical-competency-livelihoods-advisers.pdf (accessed September 2013).

- 13. Hughes R (2004) Competencies for effective public health nutrition practice: a developing consensus. Public Health Nutr 7, 683–691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jonsdottir S, Hughes R, Thorsdottir I et al. (2011) Consensus on the competencies required for public health nutrition workforce development in Europe – the JobNut project. Public Health Nutr 14, 1439–1449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Schofield C, Ashworth A, Annan R et al. (2012) Malnutrition treatment to become a core competency. Arch Dis Child 97, 468–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Davies J & Hughes R & Margetts B (2012) Towards an international system of professional recognition for public health nutritionists: a feasibility study within the European Union. Public Health Nutr 15, 2005–2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Yngve A, Tseng M, Haapala I et al. (2012) A robust and knowledgeable workforce is essential for public health nutrition policy implementation. Public Health Nutr 15, 1979–1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Pelletier DL, Frongillo EA, Gervais S et al et al. (2012) Nutrition agenda setting, policy formulation and implementation: lessons from the Mainstreaming Nutrition Initiative. Health Policy Plan 27, 19–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gostelow L (2007) Capacity Development for Nutrition in Emergencies: Beginning to Synthesise Experiences and Insights. NutritionWorks. http://www.nutritionworks.org.uk/our-publications/96-publications/capacity-development/capacity-development-pre-2010 (accessed May 2013).

- 20. Nutrition in Emergencies Regional Training Initiative (2012) About Us. http://www.nietraining.net/p/project-background.html (accessed May 2013).

- 21. Global Nutrition Cluster (2013) About the GNC. http://www.unicef.org/nutritioncluster/index_aboutgnc.html (accessed May 2013).

- 22. Association of Schools of Public Health (2012) Learning Taxonomy Levels for Developing Competencies & Learning Outcomes, Reference Guide. http://www.asph.org/document.cfm?page=723 (accessed January 2013).

- 23. Gaba DM, Howard SK, Flanagan B et al. (1998) Assessment of clinical performance during simulated crises using both technical and behavioral ratings. Anesthesiology 89, 8–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Voorhees RA (2001) Competency-based learning models: a necessary future. New Direct Institut Res 2001, 5–13. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Leung WC (2002) Competency based medical training: review. BMJ 325, 693–695. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bryce J, Coitinho D, Darnton-Hill I et al. (2008) Maternal and Child Undernutrition 4 – Maternal and child undernutrition: effective action at national level. Lancet 371, 510–526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. O'Dempsey T & Munslow B (2009) ‘Mind the gap!’ rethinking the role of health in the emergency and development divide. Int J Health Plan Manag 24, Suppl. 1, S21–S29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Humanitarian Logistics Certification Programme (2005) Certification in Humanitarian Logistics (CHL) Competence Model. http://www.hlcertification.org/mod/page/view.php?id=12 (accessed September 2013).

- 29. United Nations, Office of Human Resources Management (2010) UN Competency Development – A Practical Guide (Version 1·0). http://www.un.org/staffdevelopment/DevelopmentGuideWeb/intro1.html (accessed September 2013).