Abstract

Objective

Family meals have been negatively associated with overweight in children, while television (TV) viewing during meals has been associated with a poorer diet. The aim of the present study was to assess the association of eating family breakfast and dinner, and having a TV on during dinner, with overweight in nine European countries and whether these associations differed between Northern and Southern & Eastern Europe.

Design

Cross-sectional data. Schoolchildren reported family meals and TV viewing. BMI was based on parental reports on height and weight of their children. Cut-off points for overweight by the International Obesity Task Force were used. Logistic regressions were performed adjusted by age, gender and parental education.

Setting

Schools in Northern European (Sweden, the Netherlands, Iceland, Germany and Finland) and Southern & Eastern European (Portugal, Greece, Bulgaria and Slovenia) countries, participating in the PRO GREENS project.

Subjects

Children aged 10–12 years in (n 6316).

Results

In the sample, 21 % of the children were overweight, from 35 % in Greece to 10 % in the Netherlands. Only a few associations were found between family meals and TV viewing during dinner with overweight in the nine countries. Northern European children, compared with other regions, were significantly more likely to be overweight if they had fewer family breakfasts and more often viewed TV during dinner.

Conclusions

The associations between family meals and TV viewing during dinner with overweight were few and showed significance only in Northern Europe. Differences in foods consumed during family meals and in health-related lifestyles between Northern and Southern & Eastern Europe may explain these discrepancies.

Keywords: Family meals, Television, Overweight, Children, Europe

The prevalence of overweight and obesity has increased among schoolchildren in Europe and has been higher among those living in Southern & Eastern Europe compared with Northern Europe( 1 – 3 ). The possible determinants of overweight and obesity are several, including dietary factors such as nutrient intake, food intake and eating and meal patterns, as well as physical activity and time spent in sedentary activities, such as television (TV) viewing and computer use( 3 , 4 ).

Two recent reviews( 5 , 6 ) found that children and adolescents who had shared more frequent family meals were more likely to have a normal weight than those who had less often shared family meals. However, in one of the reviews( 6 ) the conclusion was that the inverse association between family meal frequency and overweight is inconsistent. A possible association may be explained by a healthier overall food intake( 7 , 8 ) induced by planned and daily meals. Foods typically consumed during main meals are therefore considered healthier than foods eaten as snacks. Another explanation is that a certain meal pattern is an indicator of a health-promoting lifestyle of the family. Skipping breakfast has in other studies been associated with a less healthy lifestyle, with lower levels of physical activity and higher levels of sedentary behaviour( 9 , 10 ).

Most of the studies included in the reviews of frequency of family meals and childhood overweight( 5 , 6 ) were conducted in North America and none in Europe. One study of Finnish schoolchildren showed that more frequent family meals predicted a lower BMI two years later( 11 ). The proportion of children having family meals varies between countries( 12 ) and therefore the associations between the frequency of shared family meals and overweight status may vary by country.

Another suggested meal-related determinant of overweight is TV viewing during meals( 13 – 15 ). Previous studies have found that having a TV on during meals and eating supper while watching TV negatively affect the consumption of fruit and vegetables and overall diet quality( 16 , 17 ), as well as body weight( 16 ).

The PRO GREENS project provides the opportunity to study the associations between shared family meals and overweight and between watching TV while having dinner and overweight among 11-year-olds across Europe. This age group is an interesting study population as these children are in the transition from childhood to adolescence. The children are getting more autonomy and learning to make their own decisions regarding activities, including health behaviours, but as they are still rather dependent on their parents, parents are important in shaping these children's behaviour. At same time the children are able to answer questionnaires by themselves. The daily routines developed in this age group are important for later well-being because previous studies have shown that they track into adulthood( 18 ).

The aim of the present study was to examine the associations of family meals and a habit of having the TV on during dinner with 11-year-old children's overweight in nine European countries. Based on the differences in overweight levels between Northern and Southern & Eastern European countries, we also examined whether the associations vary between these two regions. The general hypothesis was that having family meals and not having a TV on during meals are associated with a lower risk of overweight among children.

Materials and methods

The present study is a part of the PRO GREENS project, which was designed primarily to assess 11-year-olds’ consumption of fruit and vegetables in ten European countries (Bulgaria, Finland, Germany, Greece, Iceland, Norway, Portugal, Slovenia, Sweden and the Netherlands) before and after an intervention to promote fruit and vegetable consumption in schools. In the current analysis we used cross-sectional data collected at baseline in nine of the ten European countries; Norway was excluded since no data on weight were collected there. The baseline survey was conducted from April to October 2009. Sampling of schools was performed regionally in all countries, except Slovenia and the Netherlands, where the sample was nationally representative. In Bulgaria, Finland, Iceland and Sweden, schools were selected in the capital regions or in other areas, mainly in urban areas. In Finland, only Swedish-speaking schools along the Finnish coast were included (both urban and rural areas). In Germany, Greece and Portugal, the selected schools were close to the research centres (Porto, Heraklion and Giessen; C Lynch, AG Kristjansdottir, SJ te Velde et al., unpublished results).

All participating schools received a letter or a telephone call introducing the project and enquiring about participation. The procedure for collecting data had been performed before and entailed providing information to teachers on how to collect the data( 19 ). The children were asked to complete a questionnaire in the classroom, supported by teachers or research staff. The children then took another questionnaire home to be completed by one of their parents. The teachers returned all the questionnaires in closed envelopes to the national research groups, who in turn entered the data according to an agreed data protocol. All relevant medical ethics committees in the participating countries approved the PRO GREENS project's study protocol in autumn 2008. All participating parents and their children signed a consent form, whereas no incentives were given for those participating in the study.

In total (nine countries), 10 373 children were invited to participate in the study. Of these, 7680 children completed the questionnaire. The children invited to participate were born mainly in 1997 and 1998, and their mean age at baseline was 11·3 years (see Table 1). The participation rate was 74·0 % and varied between countries, from 55·2 % (the Netherlands) to 91·8 % (Greece). The present paper reports findings on 6316 children whose parents reported data on the weight and height of their child. The proportion of observations with data on weight and height varied between countries, from 54 % in Iceland to 92 % in Bulgaria and Slovenia.

Table 1.

Main sociodemographic characteristics of 11-year-old children in Europe with data on weight status, by country and in Northern and Southern & Eastern Europe, PRO GREENS project, 2009

| Variable | All | Southern & Eastern Europe | Northern Europe | Sweden | The Netherlands | Iceland | Finland | Germany | Portugal | Slovenia | Greece | Bulgaria |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n for those with weight data | 6316 | 3359 | 2957 | 652 | 503 | 378 | 857 | 567 | 703 | 1121 | 652 | 883 |

| Age (years), mean | 11·3 | 11·2 | 11·3 | 11·2 | 11·2 | 11·1 | 11·4 | 11·5 | 11·1 | 10·9 | 11·0 | 11·8 |

| Overweight (%)* | 21 | 26 | 15 | 11 | 10 | 19 | 17 | 19 | 30 | 22 | 35 | 20 |

| Parental educational level=university degree (Bachelor's or Master's) (%) | 40 | 38 | 43 | 59 | 29 | 59 | 48 | 18 | 11 | 37 | 39 | 60 |

*As defined using age- (year and month) and sex-specific cut-off points available from the International Obesity Task Force( 22 ).

Overweight

The children's BMI was based on their weight and height reported in the parents’ questionnaire. BMI based on parental reporting of height and weight has previously been found reliable and to have strong correlations with actual values( 20 , 21 ). Overweight, including obesity, was defined using age- (year and month) and sex-specific cut-off points available from the International Obesity Task Force( 22 ).

Meal-related determinants

The children's questionnaire included questions on family meal patterns and having a TV on during dinner, as follows. The children were asked how often they ate breakfast together with their mother and/or father. Corresponding questions and response categories were also asked about dinner (evening meal). The response categories were ‘every day’, ‘4–6 days per week’, ‘1–3 days per week’, ‘less than one day per week’ and ‘never’. The last two categories were combined into one for family breakfast and one for family dinner because of the few observations in these categories. The children also answered how often a TV was on during dinner. The response categories were the same as for family meals.

Confounders

Children's gender, age and parental educational level were included in the analyses as possible confounders. The parents’ questionnaire enquired about the child's mother's highest level of education; this level of education was then transformed into a dichotomous variable, distinguishing children with mothers who reported a university degree (a Bachelor's or Master's) from those with mothers of lower levels of education.

Statistical methods

The nine countries were further divided into two groups based on geographical location. The first (Northern Europe) included Finland, Germany, Iceland, the Netherlands and Sweden. The second (Southern & Eastern Europe) included Bulgaria, Greece (i.e. Crete), Portugal and Slovenia. The reason for dividing the countries is that overweight and obesity and health behaviours among schoolchildren vary between Southern & Eastern Europe, compared with Northern Europe( 1 – 3 ). Another reason for doing it was to increase the power, since the number of participants in single countries was not too high.

Data were described by mean values for continuous variables and by proportions for dichotomized variables. The χ 2 test was conducted to test whether there were differences in meal-related and overweight status variables between countries or country groups.

Logistic regression analysis was used to test the association between the meal-related variables and children's overweight separately in all nine countries. All analyses were adjusted for the gender and age of the child, as well as parental educational level. Logistic regression was used to test whether these associations differed between Northern and Southern & Eastern Europe by including an interaction term for country group and meal-related variables in the models. If the interaction terms approached significance (P < 0·1), stratified analyses by country groups were conducted and adjusted for age, gender, parental educational level and country. The results from the logistic regression analyses were reported as odds ratios and 95 % confidence intervals.

Results

Table 1 presents characteristics described by country and European region. The proportion of overweight children was higher in countries in Southern & Eastern Europe than in Northern Europe (26 % v. 15 %). The highest proportion of overweight was found in Greece (i.e. Heraklion; 35 %) and the lowest in the Netherlands (10 %). All meal-related variables and overweight status differed between countries and between country groups (all P values <0·001).

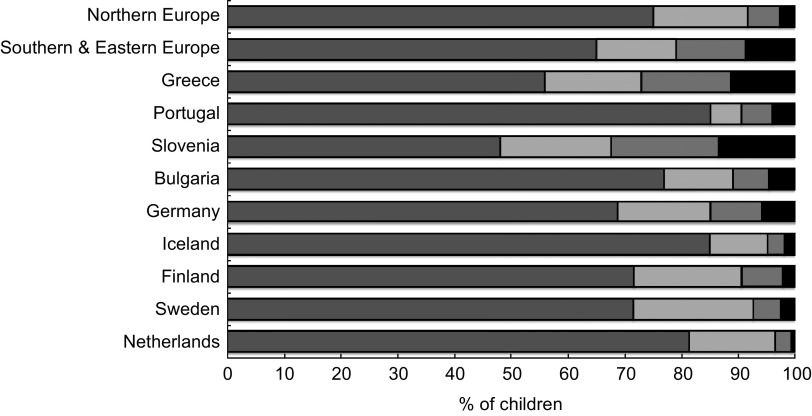

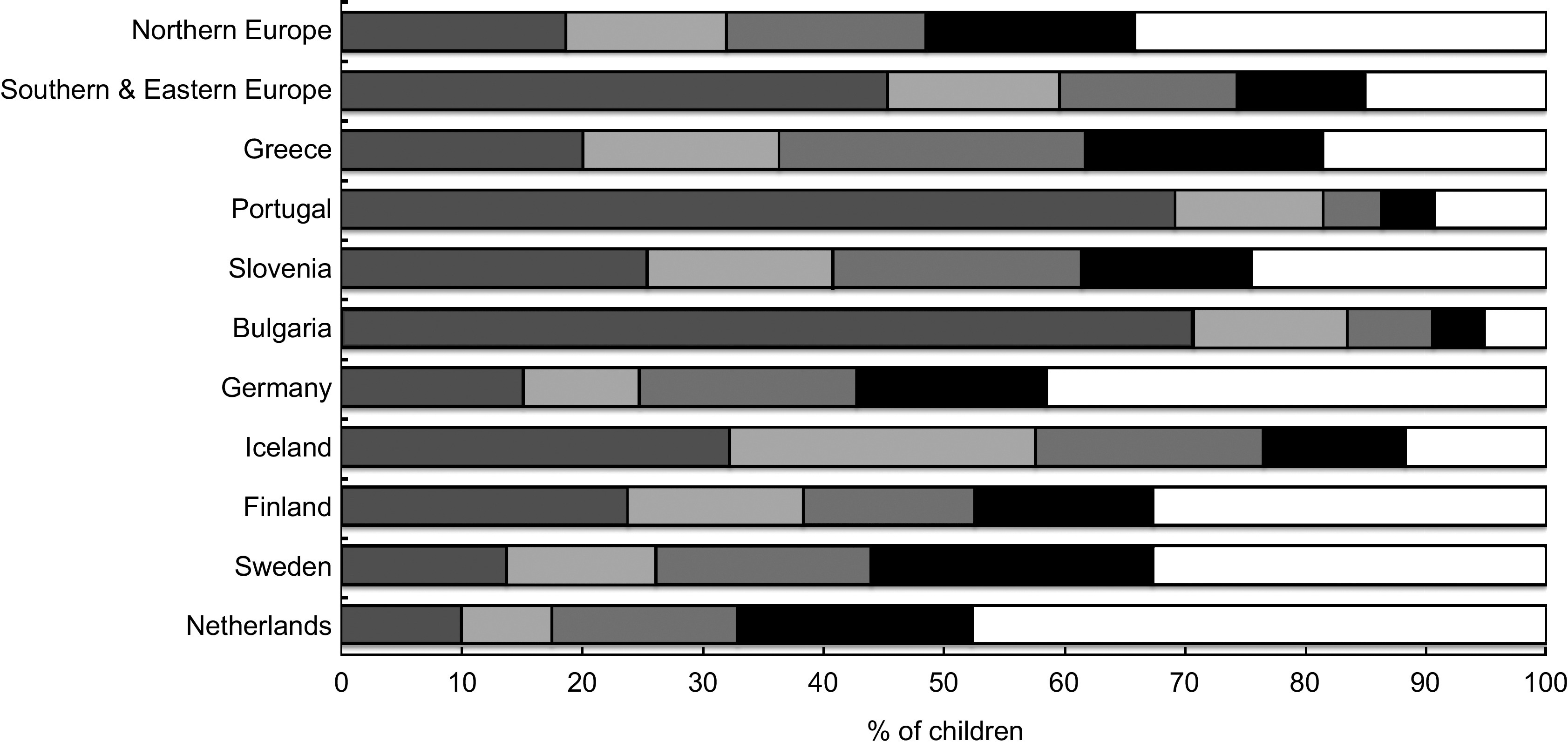

Figures 1–3 illustrate the weekly frequency of family meals and having a TV on during dinner. Daily family breakfast was more common in Northern Europe (49 %) than in Southern & Eastern Europe (38 %) with the exception of Portugal, which showed the highest proportion (60 %) of children having family breakfast daily. The lowest proportion of children having daily family breakfast was found in Slovenia (28 %) and Greece (30 %). Having family dinner daily was also more common in Northern Europe (75 %) compared with Southern & Eastern Europe (65 %). Daily family dinner was most common in Portugal (85 %) and least common in Slovenia (48 %). Having a TV on during dinner daily was less common in Northern Europe (19 %) than in Southern & Eastern Europe (45 %), most common in Portugal (68 %) and least common in the Netherlands (10 %).

Fig. 2.

How often 11-year-old children in Europe reported eating dinner together with their family ( , every day;

, every day;  , 4–6 d/week;

, 4–6 d/week;  , 2–3 d/week;

, 2–3 d/week;  , <1 d/week or never), by country and in Northern and Southern & Eastern Europe, PRO GREENS project, 2009

, <1 d/week or never), by country and in Northern and Southern & Eastern Europe, PRO GREENS project, 2009

Fig. 1.

How often 11-year-old children in Europe reported eating breakfast together with their family ( , every day;

, every day;  , 4–6 d/week;

, 4–6 d/week;  , 2–3 d/week;

, 2–3 d/week;  , <1 d/week or never), by country and in Northern and Southern & Eastern Europe, PRO GREENS project, 2009

, <1 d/week or never), by country and in Northern and Southern & Eastern Europe, PRO GREENS project, 2009

Fig. 3.

How often 11-year-old children in Europe reported having a television on during dinner ( , every day;

, every day;  , 4–6 d/week;

, 4–6 d/week;  , 2–3 d/week;

, 2–3 d/week;  , <1 d/week;

, <1 d/week;  , never), by country and in Northern and Southern & Eastern Europe, PRO GREENS project, 2009

, never), by country and in Northern and Southern & Eastern Europe, PRO GREENS project, 2009

The results from the logistic regression analyses conducted for each country are shown in Table 2. No significant association was found for family breakfast and overweight in the nine European countries. Only in Germany was family dinner associated with overweight. German children who ate dinner with their family on less than one day per week were more likely to be overweight compared with children eating dinner with their family every school day. Having a TV on during dinner was associated with overweight in three countries (Sweden, Finland and Portugal). In each of these countries, children reporting that a TV was on during dinner every day were more likely to be overweight than those reporting never having a TV on during dinner.

Table 2.

Logistic regression analyses for the relationship between overweight and family meals and watching TV during meals in 11-year-old children in nine European countries, PRO GREENS project, 2009; odds ratios and 95 % confidence intervals, adjusted for age, gender and parental educational level. Separate model for every meal-related variable

| Meal-related determinants of | Sweden | The Netherlands | Iceland | Finland | Germany | Portugal | Slovenia | Greece | Bulgaria | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| overweight | OR | 95 % CI | OR | 95 % CI | OR | 95 % CI | OR | 95 % CI | OR | 95 % CI | OR | 95 % CI | OR | 95 % CI | OR | 95 % CI | OR | 95 % CI | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| How often do you have breakfast with your mother and father? | P = 0·39 (n 622) | P = 0·69 (n 495) | P = 0·55 (n 324) | P = 0·24 (n 816) | P = 0·28 (n 524) | P = 0·92 (n 666) | P = 0·52 (n 1102) | P = 0·82 (n 639) | P = 0·26 (n 846) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Every day | 1·00 | Ref. | 1·00 | Ref. | 1·00 | Ref. | 1·00 | Ref. | 1·00 | Ref. | 1·00 | Ref. | 1·00 | Ref. | 1·00 | Ref. | 1·00 | Ref. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4–6 d/week | 1·30 | 0·67, 2·52 | 0·56 | 0·21, 1·50 | 1·63 | 0·78, 3·41 | 1·15 | 0·68, 1·95 | 0·94 | 0·47, 1·92 | 0·83 | 0·43, 1·60 | 1·06 | 0·67, 1·67 | 1·15 | 0·67, 2·00 | 0·87 | 0·52, 1·45 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1–3 d/week | 1·44 | 0·72, 2·90 | 0·86 | 0·36, 2·03 | 1·06 | 0·47, 2·37 | 1·47 | 0·92, 2·34 | 1·54 | 0·91, 2·61 | 0·92 | 0·55, 1·52 | 1·10 | 0·77, 1·58 | 1·16 | 0·76, 1·79 | 1·32 | 0·86, 2·05 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| <1 d/week | 1·84 | 0·87, 3·89 | 1·07 | 0·39, 2·95 | 1·47 | 0·64, 3·35 | 1·63 | 0·93, 2·86 | 1·58 | 0·77, 3·27 | 1·06 | 0·67, 1·66 | 0·82 | 0·54, 1·24 | 0·98 | 0·63, 1·52 | 0·83 | 0·50, 1·39 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| How often do you have dinner with your mother and father? | P = 0·89 (n 621) | P = 0·55 (n 493) | P = 0·82 (n 313) | P = 0·89 (n 809) | P = 0·003 (n 522) | P = 0·37 (n 664) | P = 0·79 (n 1078) | P = 0·92 (n 632) | P = 0·17 (n 838) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Every day | 1·00 | Ref. | 1·00 | Ref. | 1·00 | Ref. | 1·00 | Ref. | 1·00 | Ref. | 1·00 | Ref. | 1·00 | Ref. | 1·00 | Ref. | 1·00 | Ref. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4–6 d/week | 1·02 | 0·55, 1·89 | 0·70 | 0·28, 1·73 | 1·56 | 0·62, 3·94 | 1·11 | 0·69, 1·78 | 0·59 | 0·29, 1·21 | 0·57 | 0·24, 1·33 | 1·17 | 0·79, 1·72 | 1·12 | 0·71, 1·76 | 1·48 | 0·90, 2·43 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1–3 d/week | 1·25 | 0·41, 3·75 | 1·17 | 0·25, 5·50 | 0·90 | 0·18, 4·41 | 1·14 | 0·58, 2·22 | 0·79 | 0·33, 1·85 | 0·75 | 0·34, 1·63 | 1·18 | 0·80, 1·73 | 0·96 | 0·61, 1·53 | 0·94 | 0·45, 1·95 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| <1 d/week | 1·59 | 0·43, 5·83 | 4·46 | 0·36, 55·3 | 1·02 | 0·11, 9·54 | 0·66 | 0·15, 2·97 | 3·70 | 1·67, 8·19 | 0·54 | 0·18, 1·64 | 1·13 | 0·73, 1·76 | 1·13 | 0·67, 1·94 | 0·45 | 0·16, 1·31 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| How often is a TV on during dinner? | P = 0·012 (n 622) | P = 0·46 (n 477) | P = 0·71 (n 329) | P = 0·003 (n 816) | P = 0·49 (n 508) | P = 0·036 (n 665) | P = 0·63 (n 1084) | P = 0·39 (n 640) | P = 0·16 (n 859) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Every day | 2·12 | 1·08, 4·17 | 1·75 | 0·71, 4·32 | 0·98 | 0·40, 2·38 | 2·57 | 1·57, 4·20 | 1·82 | 0·95, 3·50 | 2·96 | 1·41, 6·15 | 1·20 | 0·81, 1·79 | 0·77 | 0·45, 1·30 | 1·03 | 0·47, 2·24 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4–6 d/week | 0·39 | 0·13, 1·16 | 1·92 | 0·70, 5·28 | 0·97 | 0·39, 2·42 | 1·56 | 0·85, 2·84 | 1·45 | 0·67, 3·15 | 2·21 | 0·94, 5·22 | 0·89 | 0·55, 1·44 | 0·87 | 0·50, 1·50 | 0·73 | 0·29, 1·82 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1–3 d/week | 0·73 | 0·33, 1·58 | 0·91 | 0·37, 2·26 | 0·54 | 0·19, 1·55 | 1·25 | 0·66, 2·36 | 1·09 | 0·56, 2·12 | 2·38 | 0·83, 6·81 | 0·89 | 0·57, 1·38 | 0·75 | 0·46, 1·24 | 0·66 | 0·23, 1·87 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| <1 d/week | 0·82 | 0·41, 1·65 | 0·87 | 0·37, 2·06 | 0·80 | 0·26, 2·45 | 1·40 | 0·75, 2·59 | 1·15 | 0·58, 2·31 | 1·58 | 0·50, 4·98 | 1·04 | 0·64, 1·68 | 1·16 | 0·69, 1·95 | 2·08 | 0·73, 5·93 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Never | 1·00 | Ref. | 1·00 | Ref. | 1·00 | Ref. | 1·00 | Ref. | 1·00 | Ref. | 1·00 | Ref. | 1·00 | Ref. | 1·00 | Ref. | 1·00 | Ref. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

TV, television; ref., referent category.

Significant interactions between Northern Europe and Southern & Eastern Europe for the association between meal-related determinants and overweight were found for all three variables (family breakfast, P = 0·05; family dinner, P = 0·03; TV on during dinner, P < 0·001; estimates of models not shown). Separate analyses of the association between meal-related determinants and overweight were therefore conducted in Northern Europe and Southern & Eastern Europe (Table 3). The analyses revealed that in Northern Europe overweight was more likely among children who had breakfast with the family on less than one day per week (OR=1·53) compared with those who had family breakfast daily, and among children who had a TV on during dinner daily (OR=1·94) compared to those who never had a TV on during dinner (Table 3). No significant associations between meal-related determinants and overweight were found in Southern & Eastern Europe.

Table 3.

Logistic regression analyses for the relationship between overweight and family meals and watching TV during meals in 11-year-old children in Northern Europe and Southern & Eastern Europe, PRO GREENS project, 2009; odds ratios and 95 % confidence intervals adjusted for age, gender, parental educational level and country. Separate model for every meal-related variable

| Northern Europe | Southern & Eastern Europe | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Meal-related determinants of overweight | OR | 95 % CI | OR | 95 % CI | ||

| How often do you have breakfast with your mother and father? | P=0·04 (n 2781) | P=0·27 (n 3253) | ||||

| Every day | 1·00 | Ref. | 1·00 | Ref. | ||

| 4–6 week | 1·10 | 0·81, 1·48 | 0·98 | 0·75, 1·27 | ||

| 1–3 d/week | 1·31 | 1·00, 1·72 | 1·14 | 0·93, 1·40 | ||

| <1 d/week | 1·53 | 1·11, 2·12 | 0·91 | 0·73, 1·33 | ||

| How often do you have dinner with your mother and father? | P=0·06 (n 2758) | P=0·77 (n 3212) | ||||

| Every day | 1·00 | Ref. | 1·00 | Ref. | ||

| 4–6 d/week | 0·94 | 0·70, 1·25 | 1·12 | 0·88, 1·42 | ||

| 1–3 d/week | 1·02 | 0·66, 1·59 | 1·01 | 0·78, 1·30 | ||

| <1 d/week | 2·08 | 1·21, 3·58 | 0·95 | 0·70, 1·28 | ||

| How often is a TV on during dinner? | P<0·001 (n 2752) | P=0·07 (n 3248) | ||||

| Every day | 1·94 | 1·45, 2·59 | 1·26 | 0·94, 1·68 | ||

| 4–6 d/week | 1·24 | 0·88, 1·76 | 0·96 | 0·71, 1·29 | ||

| 1–3 d/week | 0·96 | 0·68, 1·35 | 0·91 | 0·67, 1·23 | ||

| <1 d/week | 1·07 | 0·77, 1·49 | 1·24 | 0·91, 1·70 | ||

| Never | 1·00 | Ref. | 1·00 | Ref. | ||

TV, television; ref., referent category.

Discussion

The main finding of the current study was that in the total sample of nine European countries, having family meals was not associated with schoolchildren's overweight. However, when these associations were stratified by region, results showed that in Northern Europe, children having a family breakfast or dinner less than once weekly were more likely to be overweight, while there was no association between family breakfast or dinner and overweight status in the Southern & Eastern European countries. Having a TV on during dinner was associated with overweight in Northern Europe, but no significant association was found in Southern & Eastern Europe.

The proportion of children classified as overweight was 21 % and overweight was found to be more common in Southern & Eastern Europe, particularly Greece (i.e. Crete) and Portugal. The proportion of children classified as overweight in our study in different countries may not, however, be nationally representative of the prevalence of overweight, since we chose to take regional samples in Sweden, Finland, Germany, Iceland, Norway, Portugal, Bulgaria and Greece. Despite most of the samples being regional, the pattern of overweight observed between countries was quite similar to that in other studies conducted among schoolchildren in Europe, showing a high proportion of overweight particularly in Southern Europe( 1 – 3 ).

One weakness of our study is that weight data could not be obtained for all of the children and that the proportion of obtained weight data varied largely between countries, from 54 % to 92 %. This might have influenced the results, since some countries have more selective data than others and in those countries it is likely that the observed associations are weaker than they would have been with less selective data. Another weakness is that the data are not nationally representative and that the regional samples from different countries derived mainly from urban areas. The value of family meals may vary between urban and rural areas and might have influenced the results. Also, response rates varied between countries, with the highest rate observed in the countries where data collection was done close to research centres and the lowest in the countries recruiting nationally representative samples.

The proportion of children having frequent family meals or a TV on during dinner varied considerably between countries. This finding should be interpreted taking into account that the data were not nationally representative in all countries. Children in Portugal and Iceland reported the highest frequency of family meals and Slovenia and Greece the lowest, compared with the other countries. Comparable data for family meals were not found for different European countries. However, the ENERGY study, carried out in Europe among schoolchildren, also found more favourable health behaviours among children in Northern European countries compared with Southern ones( 1 – 3 ), as the current study did. The differences in family meals probably reflect differences in food culture and in organizing public meals, such as breakfast and lunch in schools, as well as differences between countries in the proportion of mothers engaged in working life and whether mothers are working full time or part time. When mothers worked full time, meal frequency in families was lower than that in families where mothers were not employed( 8 ).

Large differences between countries were also detected as to whether a TV was on during dinner. Both Portugal and Bulgaria had very high proportions of children reporting a TV being on during dinner on a daily basis. We have no clear explanation for why this variable showed a large variation between countries. Perhaps the average size or layout of apartments in the countries and the number of TV sets per family had an influence, or maybe TV habits and norms during meal times vary between, as well as within, the countries and cultures. We found a positive association between family meals and having a TV on during meals with overweight among children in Northern Europe but not in Southern & Eastern Europe. However, the association was almost significant in Southern & Eastern Europe, and significant in Portugal.

Country-specific variations in associations exist in Europe. The food eaten during family meals may vary between countries due to differences in food culture. For example, the content of breakfast varies between European countries( 23 ). Having frequent family meals may be an indicator of a healthy lifestyle in the family only in some countries. In the Nordic countries, children with frequent meals are generally more physically active and eat healthier food than children with less frequent meals( 9 , 24 ). Children watching more TV eat a greater amount of unhealthy food compared with those watching less, according to previous studies( 25 , 26 ). Having a TV on during meals may influence children's eating behaviours, such as paying attention to the TV reduces the ability to regulate energy intake( 27 , 28 ). In addition, food commercials on TV may affect eating behaviours. A study conducted in Australia, Asia, Western Europe, and North and South America found that children were exposed to high volumes of TV advertising for unhealthy foods( 29 ) and that their consumption of unhealthy foods may increase by watching more TV. Not having a TV on during meals may also be an indicator of a healthy lifestyle in some parts of Europe.

Socio-economic status, including parental educational level, income level and parental social class, may be a possible confounder, since high socio-economic status has been associated with both frequent family meals and lower risk of overweight( 30 ). We adjusted for parental educational level in the analyses, but the associations between meal-related determinants and overweight did not change. The parents’ questionnaire did not include questions on other aspects of socio-economic status, such as income level. Future studies should ideally take this element into account when examining such associations.

Most studies finding associations between family meals and overweight have been conducted in North America and to a lesser extent in Europe( 5 ). In Northern Europe, the same pattern was found as in North America, whereas no clear pattern was found in Southern & Eastern European countries. The eating context in Europe probably varies across the North–South axis, which influences the prospect of finding a consistent pattern between family meals and overweight. Despite the quite consistent association between meal patterns and overweight observed in cross-sectional studies, particularly in North America, the causality has not been confirmed in intervention studies( 10 , 31 , 32 ). The hypothesis that frequent family meals are inversely associated with overweight among adolescents in different parts of Europe could not be confirmed. It might be that in some cultures, meal patterns are indicators of a healthy lifestyle and therefore an association exists between meal patterns and overweight. Further longitudinal and intervention studies should be carried out to confirm this hypothesis.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the present cross-sectional study did not confirm the hypothesis that eating family meals and not having a TV on during dinner are consistently associated with overweight among schoolchildren in Europe. However, it seems that having a family breakfast on less than one day per week and having a TV on during dinner daily are associated with overweight in Northern Europe.

Acknowledgements

Sources of funding: The PRO GREENS project has been made possible through financial support from the European Commission's Programme of Community Action in the Field of Public Health 2003–2008 (Original Contract No. 007324). The study does not necessarily reflect the Commission's views and in no way anticipates its future policy in this area. Support from The Research Fund of the University of Iceland and as well as the Ax:son Johnson Foundation in Sweden and the JuhoVainio Foundation in Finland is also acknowledged. The above-mentioned funders had no role in the design, analysis or writing of this article. Conflicts of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest. The material presented is based on the original research of the authors and the paper has not been submitted for consideration elsewhere. Ethics: Ethical approvals for this study have been obtained from: the Regional Ethical Review Board, Stockholm, Sweden; Medisch Etische Toetsingscommissie, VU Medisch Centrum, Amsterdam, the Netherlands; the Ethics Committee at the Department of Public Health, Faculty of Medicine, University of Helsinki, Finland; the National Bioethics Committee, Reykjavik, Iceland; the Ethics Committee of the Justus-Liebig University in Giessen, Germany; the Ministry of Education and headmasters of School Julio Saul Dias and School FreiJoão de Vila do Conde, Portugal; the National Medical Ethics Committee of the Republic of Slovenia, Ljubljana, Slovenia; the Ministry of Education, Lifelong Learning and Religious Affairs, Greece; and the Commission of Medical Ethics at the National Centre of Public Health Protection, Sofia, Bulgaria. Authors’ contributions: Each author has participated sufficiently in the work, analysis of the data and writing of the manuscript, as well as has seen and approved the final version. Acknowledgements: The authors would like to give a special thanks to all teachers and children who took the time to participate in this survey and to all the staff and students from the ten participating countries who contributed to the collection and entry of the data.

References

- 1. Pigeot I, Barba G, Chadjigeorgiou C et al. (2009) Prevalence and determinants of childhood overweight and obesity in European countries: pooled analysis of the existing surveys within the IDEFICS Consortium. Int J Obes (Lond) 33, 1103–1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Yngve A, De Bourdeaudhuij I, Wolf A et al. (2008) Differences in prevalence of overweight and stunting in 11-year olds across Europe: The Pro Children Study. Eur J Public Health 18, 126–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Brug J, van Stralen MM, Te Velde SJ et al. (2012) Differences in weight status and energy-balance related behaviors among schoolchildren across Europe: the ENERGY-project. PloS One 7, e34742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Branca F, Nikogosian H & Lobstein T (2007) The Challenge of Obesity in the WHO European Region and the Strategies of Response. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hammons AJ & Fiese BH (2011) Is frequency of shared family meals related to the nutritional health of children and adolescents? Pediatrics 127, e1565–e1574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Valdes J, Rodriguez-Artalejo F, Aguilar L et al. (2013) Frequency of family meals and childhood overweight: a systematic review. Pediatr Obes 8, e1–e13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pedersen TP, Meilstrup C, Holstein BE et al. (2012) Fruit and vegetable intake is associated with frequency of breakfast, lunch and evening meal: cross-sectional study of 11-, 13-, and 15-year-olds. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 9, 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Neumark-Sztainer D, Hannan PJ, Story M et al. (2003) Family meal patterns: associations with sociodemographic characteristics and improved dietary intake among adolescents. J Am Diet Assoc 103, 317–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Keski-Rahkonen A, Kaprio J, Rissanen A et al. (2003) Breakfast skipping and health-compromising behaviors in adolescents and adults. Eur J Clin Nutr 57, 842–853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Timlin MT, Pereira MA, Story M et al. (2008) Breakfast eating and weight change in a 5-year prospective analysis of adolescents: Project EAT (Eating Among Teens). Pediatrics 121, e638–e645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lehto R, Ray C & Roos E (2012) Longitudinal associations between family characteristics and measures of childhood obesity. Int J Public Health 57, 495–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Patro B & Szajewska H (2010) Meal patterns and childhood obesity. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care 13, 300–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bauer KW, Neumark-Sztainer D, Fulkerson JA et al. (2011) Familial correlates of adolescent girls’ physical activity, television use, dietary intake, weight, and body composition. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 8, 25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Custers K & Van den Bulck J (2010) Television viewing, computer game play and book reading during meals are predictors of meal skipping in a cross-sectional sample of 12-, 14- and 16-year-olds. Public Health Nutr 13, 537–543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gable S, Chang Y & Krull JL (2007) Television watching and frequency of family meals are predictive of overweight onset and persistence in a national sample of school-aged children. J Am Diet Assoc 107, 53–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Liang T, Kuhle S & Veugelers PJ (2009) Nutrition and body weights of Canadian children watching television and eating while watching television. Public Health Nutr 12, 2457–2463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Feldman S, Eisenberg ME, Neumark-Sztainer D et al. (2007) Associations between watching TV during family meals and dietary intake among adolescents. J Nutr Educ Behav 39, 257–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mikkila V, Rasanen L, Raitakari OT et al. (2005) Consistent dietary patterns identified from childhood to adulthood: the Cardiovascular Risk in Young Finns Study. Br J Nutr 93, 923–931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Haraldsdottir J, Thorsdottir I, de Almeida MD et al. (2005) Validity and reproducibility of a precoded questionnaire to assess fruit and vegetable intake in European 11- to 12-year-old schoolchildren. Ann Nutr Metab 49, 221–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Goodman E, Hinden BR & Khandelwal S (2000) Accuracy of teen and parental reports of obesity and body mass index. Pediatrics 106, 52–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sekine M, Yamagami T, Hamanishi S et al. (2002) Accuracy of the estimated prevalence of childhood obesity from height and weight values reported by parents: results of the Toyama Birth Cohort study. J Epidemiol 12, 9–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Cole TJ, Bellizzi MC, Flegal KM et al. (2000) Establishing a standard definition for child overweight and obesity worldwide: international survey. BMJ 320, 1240–1243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mullan BA & Singh M (2010) A systematic review of the quality, content, and context of breakfast consumption. Nutr Food Sci 40, 81–114. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sjoberg A, Hallberg L, Hoglund D et al. (2003) Meal pattern, food choice, nutrient intake and lifestyle factors in The Goteborg Adolescence Study. Eur J Clin Nutr 57, 1569–1578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Rey-Lopez JP, Vicente-Rodriguez G, Repasy J et al. (2011) Food and drink intake during television viewing in adolescents: the Healthy Lifestyle in Europe by Nutrition in Adolescence (HELENA) study. Public Health Nutr 14, 1563–1569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sisson SB, Broyles ST, Robledo C et al. (2012) Television viewing and variations in energy intake in adults and children in the USA. Public Health Nutr 15, 609–617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bellisle F, Dalix AM & Slama G (2004) Non food-related environmental stimuli induce increased meal intake in healthy women: comparison of television viewing versus listening to a recorded story in laboratory settings. Appetite 43, 175–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Francis LA & Birch LL (2006) Does eating during television viewing affect preschool children's intake? J Am Diet Assoc 106, 598–600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kelly B, Halford JC, Boyland EJ et al. (2010) Television food advertising to children: a global perspective. Am J Public Health 100, 1730–1736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Vereecken C, Dupuy M, Rasmussen M et al. (2009) Breakfast consumption and its socio-demographic and lifestyle correlates in schoolchildren in 41 countries participating in the HBSC study. Int J Public Health 54, Suppl. 2, 180–190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Koletzko B & Toschke AM (2010) Meal patterns and frequencies: do they affect body weight in children and adolescents? Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 50, 100–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Smith Price JL, Day RD & Yorgason JB (2009) A longitudinal examination of family processes, demographic variables, and adolescent weight. Marriage Family Rev 45, 310–330. [Google Scholar]