Abstract

Objective

To review the available literature on accountability frameworks to construct a framework that is relevant to voluntary partnerships between government and food industry stakeholders.

Design

Between November 2012 and May 2013, a desk review of ten databases was conducted to identify principles, conceptual frameworks, underlying theories, and strengths and limitations of existing accountability frameworks for institutional performance to construct a new framework relevant to promoting healthy food environments.

Setting

Food policy contexts within high-income countries to address obesity and diet-related non-communicable diseases.

Subjects

Eligible resources (n 26) were reviewed and the guiding principles of fifteen interdisciplinary frameworks were used to construct a new accountability framework.

Results

Strengths included shared principles across existing frameworks, such as trust, inclusivity, transparency and verification; government leadership and good governance; public deliberations; independent bodies recognizing compliance and performance achievements; remedial actions to improve accountability systems; and capacity to manage conflicts of interest and settle disputes. Limitations of the three-step frameworks and ‘mutual accountability’ approach were an explicit absence of an empowered authority to hold all stakeholders to account for their performance.

Conclusions

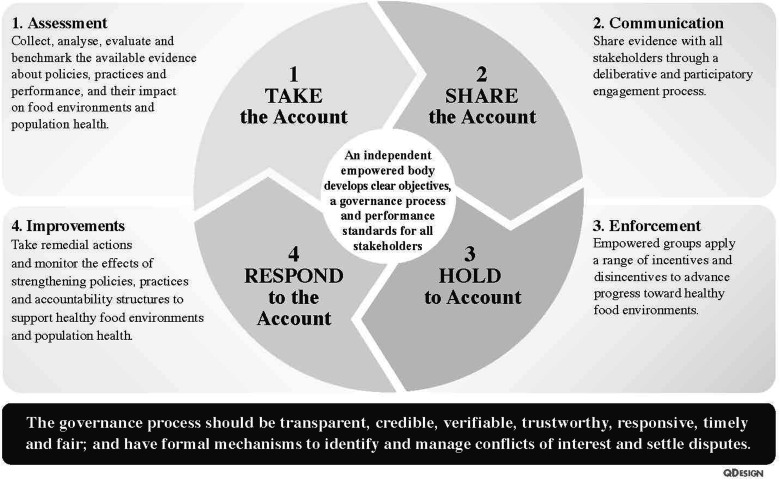

We propose a four-step accountability framework to guide government and food industry engagement to address unhealthy food environments as part of a broader government-led strategy to address obesity and diet-related non-communicable diseases. An independent body develops clear objectives, a governance process and performance standards for all stakeholders to address unhealthy food environments. The empowered body takes account (assessment), shares the account (communication), holds to account (enforcement) and responds to the account (improvements).

Keywords: Healthy food environments, Voluntary partnerships, Accountability structures, Commitments, Performance, Disclosures

Policy action to improve food environments exists at three levels: (i) development; (ii) implementation; and (iii) monitoring and evaluation. As rates of obesity and non-communicable diseases (NCD) increase worldwide( 1 ), norm-setting institutions such as the WHO recommend that national governments have primary responsibility and authority to develop policies that create equitable, safe, healthy and sustainable food environments to prevent and control obesity and diet-related NCD( 2 – 6 ).

Expert bodies recommend that governments engage all societal sectors to successfully reduce NCD( 3 ). Diverse stakeholders can share responsibility to implement, monitor and evaluate policies without compromising the integrity of these efforts( 2 – 7 ). However, national governments are increasingly sharing or relinquishing their responsibility for policy development with non-governmental stakeholders, especially unhealthy commodity industries that manufacture and market fast foods, sweetened beverages and alcohol, which is discouraged( 8 – 11 ).

A century ago, the US Supreme Court Justice, Louis Brandeis, emphasized the need for public information disclosure and law enforcement to hold the government and corporations accountable for their impacts on society( 12 ). He is often remembered for the quote: ‘Publicity is justly commended as a remedy for social and industrial diseases. Sunlight is said to be the best of disinfectants; electric light the most efficient policeman.’

This observation is salient today to guide national governments’ engagement strategy with private-sector businesses and non-governmental organizations (NGO) to address unhealthy food environments and improve population health outcomes.

Governments are accountable to the people who elect them and are expected to protect the policy-making process from commercial interests by upholding robust standards to promote public interests over private interests, ensure transparency and manage conflicts of interest( 8 – 11 ). Some contend that there has been very limited progress to develop policies that support healthy food environments due to commercial interest-group pressures on government policy( 8 – 11 ).

The purpose of the present paper is to describe the current food policy-making context at the global level and in high-income countries before conducting an interdisciplinary evidence review of principles, frameworks and underlying theories about accountability for institutional performance. The results are used construct a new accountability framework to address unhealthy food environments. We discuss this framework using examples from high-income countries, which are relevant to government, food industry and NGO in low- and middle-income countries, to address obesity and diet-related NCD.

Background

The global context

The WHO's 2004 Global Strategy on Diet, Physical Activity and Health( 2 ) emphasized different priorities for government, businesses and NGO. Governments are responsible for developing policy to support healthy food environments and ensure that all stakeholders follow recommended guidelines and laws. Businesses are responsible for adhering to laws and international standards, and NGO are responsible for influencing consumer behaviour and encouraging other stakeholders to support positive efforts.

Nearly a decade later, explicit language was included in the WHO's 2013–2020 global action plan to prevent and control NCD that encouraged collaborative partnerships among government agencies, civil society and the private sector to reduce NCD by 25 % by 2025( 3 ). The resolution approved by 194 Member States encouraged national governments to ‘ensure appropriate institutional, legal, financial and service arrangements to prevent and control NCDs’( 3 ). The WHO Director, Dr Margaret Chan, has criticized the food industry for opposing government regulation by blaming obesity on a lack of individual willpower instead of acknowledging the failure of governments to regulate ‘Big Business’( 11 ).

Governments are faced with managing power imbalances that influence policy, institutionalized norms and governance processes. Accountability involves how and why decisions are made, who makes decisions, how power is used, whose views are important and who holds decision makers to account( 13 ). Without strong and independent accountability structures, governments are unlikely to implement actions to manage the power imbalances that can influence the policy development and governance processes( 14 ) to achieve the WHO's global target to reduce NCD morbidity and mortality( 15 ).

In July 2013, the UN Economic and Social Council established a WHO-led Interagency Task Force to coordinate and implement all UN organizational activities supporting the WHO's 2003–2020 global NCD action plan( 16 ). The Task Force represents a transnational governance structure to advise governments, NGO and the private sector on how to reduce obesity and diet-related NCD while safeguarding public health from potential conflicts of interest( 16 ).

Food environments

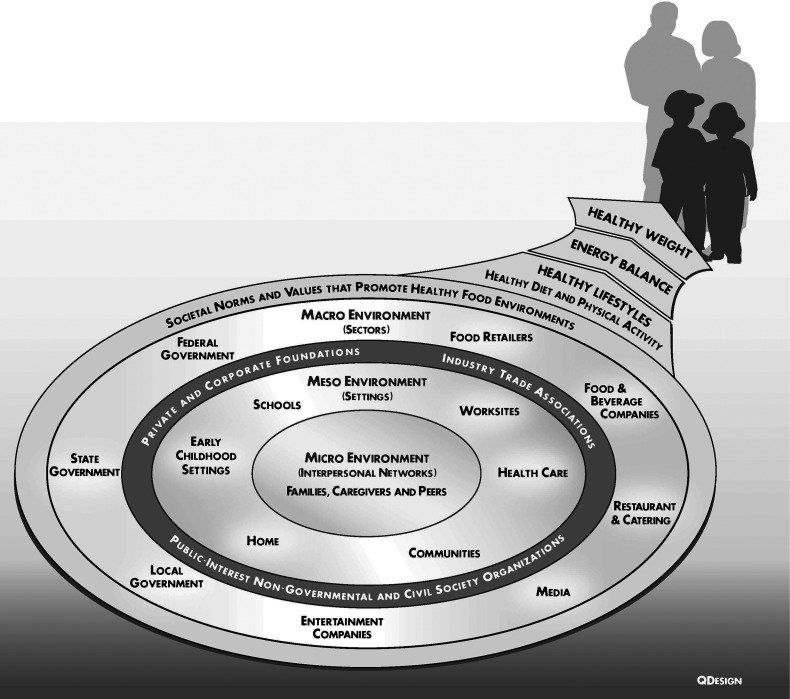

Food environments are conceptualized and interpreted in different ways( 17 – 22 ). Empirical research suggests that food environments influence the dietary choices, preferences, quality and eating behaviours of individuals and populations( 17 – 22 ) at local, national and global levels. In the present paper, healthy food environments are defined as the collective economic, policy and sociocultural conditions and opportunities( 21 ) across sectors (i.e. macro, meso and micro) and settings (i.e. home, schools, worksites, food retail outlets) that provide people with regular access to a healthy diet to achieve a healthy weight to prevent obesity and diet-related NCD (Fig. 1)( 20 – 22 ).

Fig. 1.

A socio-ecological model illustrating stakeholders involved in promoting healthy food environments for populations (adapted from references 20–22)

Guidelines for a healthy diet encourage a variety of nutrient-dense foods and modest consumption of energy-dense foods to help people maintain a healthy weight( 2 , 4 , 5 , 7 , 23 , 24 ).

An unhealthy diet is linked to poorer health outcomes( 25 ) because it encourages people to overconsume energy, total fat, saturated fat, trans-fats, added sugars and salt( 26 , 27 ).

Unhealthy diets and food environments drive three major NCD contributing to premature morbidity and mortality( 1 , 3 ). In 2010, seven of the top twenty deaths and disabilities worldwide were related to poor diet( 28 ) and excessive salt consumption and inadequate fruit and vegetable intake contributed 10 % of the global burden of disease( 29 ).

Government responsibility shifting to the private and non-governmental organization sectors

Since the 1970s, many Western democracies have embraced neoliberal governance models that support government de-regulation, privatization of public services and devolution of government responsibility to the private sector and NGO through public–private partnerships to address complex societal problems( 30 – 32 ).

These trends have produced three outcomes. First, national governments have embraced private-interest language that has shifted the state's responsibility to address social problems from collective concerns to individual or family concerns requiring self-help solutions( 30 – 32 ). Second, major public policy choices are framed as what governments can afford rather than what will benefit the public's interests( 30 – 32 ). Third, private entities have used government legislative and legal institutions to secure corporate privileges over citizens’ rights( 30 , 33 , 34 ).

Neoliberal approaches have fostered governance gaps in an era of industry self-regulation. Certain global food industry stakeholders have used their economic and political power to set policy agendas; engage in corporate lobbying and political campaign financing to legitimize commercial interests; and influence the regulatory decisions of government agencies( 35 ).

Some suggest that governments have conspired with the food industry to prevent meaningful action by using libertarian paternalism (i.e. ‘nudge approach’) and voluntary partnerships as the primary strategies to address unhealthy food environments( 30 , 35 – 37 ) without adequate accountability structures to ensure that societal needs are met.

One example is the Public Health Responsibility Deal Food Network in England that has evoked criticism of voluntary industry engagement approaches because the government has not established consequences for non-participating companies or sectors( 37 ). These concerns highlight the need for clear accountability structures to prevent the ‘corporate capture of public health’, where private-sector stakeholders can circumvent government regulation by encouraging voluntary cooperation through non-adversarial partnerships and oppose government regulation for economic reasons( 36 , 37 ).

Responses to voluntary partnerships

Strategic alliances and voluntary partnerships are recommended by numerous authoritative bodies( 2 – 7 , 16 , 22 , 24 ) to address unhealthy food environments, yet these mechanisms were not intended as the central approach of a national obesity and NCD prevention strategy. Several types of voluntary partnerships have emerged to respond to nutrition-related challenges, ranging from undernutrition to obesity and diet-related NCD( 38 ). These partnerships remain controversial because evidence of their effectiveness to address specific food environment objectives, without undermining public health goals, is lacking( 10 , 39 – 42 ).

The food industry complex is comprised of many private-sector stakeholders who interact in different ways with government and other public and private entities to influence consumer demand and promote food and beverage product purchases and consumption( 20 – 22 ) (Fig. 1).

Food industry stakeholders have responded to obesity and NCD in several ways.

Some have formed alliances and partnerships at global( 43 ), regional( 44 – 47 ) and national( 48 – 50 ) levels by committing to food product reformulation or developing new products with healthier nutrient profiles by reducing salt, energy and saturated fat, and eliminating trans-fats( 43 – 45 , 47 – 50 ); implementing community-based obesity prevention programmes( 45 , 46 ); providing nutrition information, out-of-home energy (calorie) and front-of-package labelling to inform marketplace purchases( 43 , 49 – 51 ); and improving the quality of foods advertised and marketed to children and adolescents( 43 , 45 , 52 , 53 ) (Table 1). Industry alliances and companies also have disseminated reports outlining their accomplishments( 48 , 54 ) or contracted third-party auditors to assess, verify and report on their performance for more contested issues( 55 , 56 ).

Table 1.

Examples of food industry alliances and intersectoral partnerships to promote healthy food environments

| Initiative (year started) | Description | Voluntary pledges and commitments |

|---|---|---|

| Global examples | ||

| International Food and Beverage Alliance( 43 ) (2008) | An alliance comprised of ten leading global food and beverage manufacturers whose CEO made five public pledges aligned with the WHO's 2004 Global Strategy on Diet, Physical Activity and Health. The companies include: Coca Cola Company, Ferrero, General Mills, Grupo Bimbo, Kellogg's, Mondelez International, Mars, Nestlé, PepsiCo and Unilever | In 2008, the Alliance made the following pledges: 1. Reformulate products and develop new products to improve diets 2. Provide understandable information to consumers 3. Extend responsible advertising and marketing to children's initiatives globally 4. Raise awareness about balanced diets and increasing physical activity levels 5. Actively support public–private partnerships through WHO's Global Strategy |

| Transnational examples | ||

| Cereal Partners Worldwide( 44 ) (2009) | A joint venture between Nestlé S.A. and General Mills to produce, manufacture and market cereals worldwide outside the USA and Canada | In 2009, the partners pledged to reduce the sugar content in breakfast cereals and meet other nutrient pledges in the EU and Australia |

| EU Platform for Action on Diet, Physical Activity and Health( 45 ) (2005) | A multi-stakeholder forum comprised of twenty-seven EU governments, the WHO, thirty-three European associations, industry, NGO and health professionals to engage members in constructive dialogue to stimulate actions that address healthy nutrition, physical activity promotion and obesity prevention | Between 2005 and 2012, 292 commitments were launched for six areas: 1. Advocacy and information exchange 2. Improve marketing and advertising 3. Improve food composition, expanding healthy products and portion sizes 4. Provide consumer information (i.e. labelling) 5. Promote education and lifestyle modification 6. Promote physical activity |

| Task Force for a Trans Fat Free America Initiative( 47 ) (2007) | A regional initiative of PAHO/WHO involving several Latin American and Caribbean countries to phase out and eliminate trans-fats from their food supplies | In 2007, the PAHO/WHO Task Force aimed to: 1. Evaluate the impact of trans-fats on human nutrition and health 2. Examine the feasibility of using healthier alternative fats 3. Engage with the food industry to identify common ground for action to expedite the process of phasing out trans-fatty acids and promote the adoption of healthier oils and dietary fats in the national and regional food supply 4. Identify legislative and regulatory approaches to phase out trans-fats from the Latin American and the Caribbean food supply |

| National examples | ||

| US Healthy Weight Commitment Foundation( 48 ) (2009) | A food industry initiative described as a ‘CEO-led coalition and partnership comprised of more than 200 organizations working together to reduce childhood obesity by 2015’ | In 2010, sixteen food and beverage companies made a calorie-reduction pledge to remove 1·5 trillion calories from the US food supply by 2015 |

| Public Health Responsibility Deal Food Network( 49 ) (2011) | A UK government initiative to foster voluntary partnerships with relevant food industry groups to improve the healthfulness of food environments | Between March 2011 and September 2013, the Food Network implemented voluntary pledges for relevant food industry sectors to: 1. Implement out-of-home calorie labelling 2. Reduce salt (6 g salt/person per d by 2015) among food manufacturers, restaurants and caterers 3. Remove or eliminate trans-fats 4. Reduce calories to collectively remove 5 billion calories from the food supply 5. Reduce saturated fat from the food supply |

| 6. Support an environment for fruit and vegetable promotion | ||

| Healthy Australia Commitment( 50 ) (2012) | Australian initiative launched and coordinated by the Australian Food & Grocery Council, an industry commitment to meet several nutrient targets by 2015 | In October/November 2012, the commitment proposed implementing three pledges by 2015: 1. Reduce saturated fat by 25 % 2. Reduce salt in products by 25 % 3. Reduce calories in products by 12·5 % |

CEO, chief executive officer; EU, European Union; NGO, non-governmental organization; PAHO, Pan American Health Organization.

Many public-interest NGO, professional societies and academics have observed that large food industry stakeholders have privileged access to policy makers that permits financial and political lobbying to support business interests over public health interests( 57 – 60 ). Corporate lobbying is one of many practices that has fuelled public-interest NGO distrust of food industry practices including voluntary partnerships to address obesity and NCD rates( 9 , 10 , 61 – 66 ). Despite the promise of collaborative approaches( 38 ) certain public health advocates have deemed them to be ineffective at tackling food environment policy issues( 10 ). Partnerships alone will not mitigate harmful commercial practices. Government legislation and regulatory oversight are also necessary to address unhealthy food environments( 66 – 69 ).

The background literature discussed shows that the issue of voluntary partnerships to address unhealthy food environments has primarily focused on establishing boundaries for stakeholders’ responsibility and measuring their effectiveness to achieve goals. There is limited empirical research on the accountability structures, processes and mechanisms required to build trust and ensure credibility for voluntary partnerships to promote healthy food environments. The current paper fills an important research and policy gap by seeking to integrate principles, conceptual frameworks and theories for institutional accountability to develop a new framework that national governments, food industry and NGO stakeholders can use to collectively promote healthy food environments to address obesity and diet-related NCD.

Design

The present review was guided by two research questions:

-

1.

What types of accountability frameworks, principles and mechanisms are used to hold major stakeholders accountable for institutional performance to implement specific policies and actions to address unhealthy food environments?

-

2.

How can these findings inform the development of an accountability framework to hold relevant stakeholders accountable for promoting and not undermining healthy food environments?

The accountability literature was initially explored to identify appropriate search terms. Due to the complexity and breadth of this literature, a systematic review was not used. Instead, an interdisciplinary literature review of ten databases (i.e. Academic Search Complete, Business Source Complete, CINAHL, Global Health, Health Business Elite, Health Policy Reference Center, Health Source, MEDLINE Complete, Political Science Complete and SocINDEX) was conducted over six months (November 2012 through May 2013) for English-language documents (from 1 January 2000 through 31 May 2013) to identify principles, conceptual frameworks and their underlying theories related to accountability for institutional performance. A combination of subject heading and text terms were used to search the databases including: accountability, responsibility, framework, government, industry, corporate, food companies, NGOs, civil society, media, partnerships, alliances, performance, commitment, compliance, legislation and regulation.

A total of 180 peer-reviewed journal articles, reports and books were retrieved, screened by title and abstract, and imported into an Endnote database. Full-text versions of potentially relevant sources were screened and read for inclusion. The reference lists of the included documents were searched and supplemented by the grey literature to identify conceptual frameworks, theories and principles related to accountability for institutional performance.

Results

The findings from twenty-six evidentiary sources based on fifteen existing interdisciplinary frameworks included in the current review are summarized in Table 2. These findings were used to develop a new accountability framework that government and other stakeholders can use to promote healthy food environments.

Table 2.

Summary of evidence used from fifteen interdisciplinary frameworks to develop the healthy food environments accountability framework

| Source | Conceptual framework (underlying theory) | Description of accountability principles |

|---|---|---|

| Disciplines: international relations, trade and development, human rights and health | ||

| Grant & Keohane( 70 ) | Rational actor model framework | In the transnational and global contexts, accountability is based on a relationship of power-wielders or agents (ones who are held to account) and principals (ones who hold to account), where there is general recognition of the legitimacy of the standards for accountability and the authority of the parties to the relationship. The agents are obliged to act in ways that are consistent with accepted standards of behaviour or they will be sanctioned for failures to comply with the standards |

| Principal–agent theory | ||

| Each actor has his/her own set of goals and objectives, and these actors take action based on an analysis of the costs and benefits of various available options to maximize their self-interest | ||

| Bovens( 71 ) | Accountability evaluation framework for public organizations and officials | This framework can be used to map and evaluate the adequacy of political accountability arrangements for public organizations and officials who exercise authority in the EU or other governance system where decisions and actions impact on society. It identifies three theoretical accountability perspectives: |

| Principal–agent theory Each actor has his/her own set of goals and objectives, and these actors take action based on an analysis of the costs and benefits of various available options to maximize their self-interest | 1. Democratic perspective (e.g. popular control makes the citizens the primary principals in the principal–agent model who are at the end of the accountability chain) | |

| 2. Constitutional perspective (e.g. checks and balances and independent judicial power foster a dynamic equilibrium to oversee good governance) | ||

| 3. Learning perspective (e.g. accountability is an instrument for ensuring that governments, agencies, businesses and officials deliver on their promises, otherwise face consequences or sanctions) | ||

| The framework describes four ways of conceptualizing accountability – the nature of the setting (five forums), the nature of the stakeholder (four types), the nature of the conduct (three types) and the nature of the obligation (three types): | ||

| 1. To whom is the account to be delivered? | ||

| • Political accountability (e.g. elected officials, political parties, voters and the media) | ||

| • Legal accountability (e.g. courts) | ||

| • Administrative accountability (e.g. auditors, inspector and controllers) | ||

| • Professional accountability (e.g. peers) | ||

| • Social accountability (e.g. interest groups, watchdog NGO) | ||

| 2. Who is the actor or stakeholder to be held accountable? | ||

| • Corporate accountability (the organization as the actor) | ||

| • Hierarchical accountability (one for all) | ||

| • Collective accountability (all for one) | ||

| • Individual accountability (each person for himself or herself) | ||

| 3. Which aspect of the conduct is to be held to account? | ||

| • Financial | ||

| • Procedural | ||

| • Product | ||

| 4. What is the nature of the accountability arrangement? | ||

| • Vertical accountability (e.g. formal authority where one group holds power over another group) | ||

| • Diagonal accountability (e.g. providing account to society is voluntary and there are no interventions on the part of a principal power-wielder within a hierarchy) | ||

| • Horizontal accountability (e.g. when agencies account for themselves, such as mutual accountability) | ||

| Steets( 72 ) | Accountability model for global partnerships | Accountability principles for global partnerships vary depending on the type of partnership. Four major types of partnerships have different accountability standards: |

| Principal–agent theory | 1. Partnerships for advocacy and awareness-raising | |

| Each actor has his/her own set of goals and objectives, and these actors take action based on an analysis of the costs and benefits of various available options to maximize their self-interest | 2. Partnerships for rule-setting and regulation | |

| 3. Partnerships for policy or programme implementation | ||

| 4. Partnerships for generating information | ||

| Wolfe & Baddeley( 73 ) | Regulatory transparency framework | Accountability mechanisms reduce information asymmetry and allow verification by other parties and citizens of national laws, policies and implementation to achieve intended objectives. The framework has three transparency principles: |

| New trade theory | 1. Publication of the trade rules (e.g. right to know) | |

| A set of economic models in international trade that focus on the role of building large industrial bases in certain industries and allowing these sectors to dominate the world trade market | 2. Peer review by governments (monitoring and surveillance) | |

| 3. Public engagement (e.g. reporting on results and the role of NGO as watchdogs) | ||

| Joshi( 74 ) | Social accountability framework | This framework examines the contextual factors in macro and micro environments and processes (causal chain factors) associated with achieving social accountability, which represents the broad actions that citizens can take (in cooperation with other stakeholders including civil society groups and the media) to hold the government and state actors accountable for improving development outcomes. Social accountability has three main components: |

| O'Meally( 75 ) | Change theory | 1. Information and transparency |

| This theory maps out the steps, conditions or sequence of events from inputs to outcomes to achieve a desirable goal. It informs how one conceptualizes citizen-led accountability actions to pursue good governance practices | 2. Citizen action | |

| 3. An official response to achieve desired outcomes | ||

| The principles associated with social accountability include transparency and information collection; operational tools (e.g. community scorecards or advocacy campaigns); institutional reform (e.g. policy, legal and financial); modes of engagement (e.g. collaboration, contention and citizen participation); and a focus on outcomes (e.g. improved service delivery, answerability or sanctions) | ||

| OECD( 76 ) | Partnership governance accountability framework | This framework offers several principles to guide partnership governance and accountability to enhance partnership credibility and effectiveness, including: 1. Being held to account (compliance) 2. Giving an account (transparency) 3. Taking account (responsiveness to stakeholders) 4. Mutual accountability (compacts are built between partners and relevant stakeholders) 5. Create incentives for good partnership governance systems that stakeholders trust |

| Rochlin et al.( 13 ) | Governance theory | |

| Steer & Wanthe( 77 ) | This theory was developed by the World Bank to support partnerships for international development focused on public service and infrastructure (e.g. waste management and transport) and delivering resources to address public health goals (e.g. HIV/AIDS, road safety, capacity development and issue-based advocacy) | |

| Ruger( 78 ) | Shared health governance framework | This framework advocates for a shared global governance for health to reduce suboptimal results of self-maximization of a principal–agent theory-based framework. A social agreement model supports collective actions based on three features: |

| Shared health governance theory An alternative to global health governance theory based on a moral conception of global health justice that asserts a duty to reduce inequalities, addresses threats to health and identifies shared global and domestic health responsibilities | 1. Partnerships are defined by shared goals | |

| 2. Clear objectives and agreed roles and responsibilities 3. Shared expertise and accountability to pursue goals | ||

| WHO( 79 ) | Accountability framework for women's and children's health Human rights theory Based on the premise that there is a rational moral order that precedes social and historical conditions and applies certain universal rights to all human beings at all times | The Commission on Information and Accountability for Women's and Children's Health developed ten recommendations and a three-step accountability framework to ensure that all women and children achieve healthy equity and attain the fundamental human right of the highest standard of health. The framework has three interconnected guiding principles (e.g. Monitor, Review and Act) that inform continuous improvement. It links accountability for resources to the results, outcomes and impacts they produce; and involves active engagement of national governments, communities and civil society with strong links between national and global mechanisms |

| UN Human Rights Office( 80 ) | Protect, respect and remedy framework Human rights theory Based on the premise that there is a rational moral order that precedes social and historical conditions and applies certain universal rights to all human beings at all times | The guiding principles of this three-step framework include: |

| 1. Protect: states (national governments) have a legal and policy duty to protect against human rights abuses | ||

| 2. Respect: corporations have a responsibility to respect human rights and must act with due diligence to identify, prevent, mitigate and account for how they address impacts on human rights | ||

| 3. Remedy: governments are held accountable when they fail to take appropriate steps to investigate, punish and redress human rights abuses by corporations through effective policies, legislation, regulations and adjudication | ||

| Bonita et al.( 81 ) | Accountability framework for NCD prevention Accountability theory This theory does not assume a trust-based relationship between a principal (the one who holds to account) and the agent (the one who is held to account). Agents (organizations) cannot be trusted to act in the best interests of the principal (society) when there is a conflict between both parties | Strong leadership is required from governments to meet national commitments to the UN political declaration on preventing and managing NCD and to achieve the goal of a 25 % reduction in premature NCD mortality by 2025. This three-step accountability framework is based on the UN Protect, Respect and Remedy framework described above. The steps include: |

| 1. Monitor stakeholders’ progress toward commitments | ||

| 2. Review progress achieved | ||

| 3. Respond appropriately to address NCD | ||

| Disciplines: business, finance and social accounting | ||

| Deegan( 82 ) | Corporate accountability framework | |

| Isles( 83 ) Moerman & Van Der Laan( 84 ) | Legitimacy theory A perceived social contract exists between a company and the society in which it operates. The contract represents the social expectations for how a company should conduct its business operations | Accountability principles for financial accounting or CSR or sustainability reporting include: public information and financial disclosures, auditability, completeness, relevance, accuracy, transparency, comparability, timeliness, inclusiveness, clarity, checks and balances, stakeholder dialogue, scope and nature of the process, meaningfulness of information, and remediation to address misconduct. Two levels of legitimacy relevant to corporations include macro and micro levels: |

| Newell( 85 ) Stanwick & Stanwick( 86 ) Swift( 87 ) Tilling & Tilt( 88 ) Tilt( 89 ) | Stakeholder theory Extends legitimacy theory to consider how stakeholders demand different information from businesses, which respond to these demands in several ways | 1. Macro level (institutional legitimacy) is influenced by government, social norms and market-based economy values |

| 2. Micro level (company-specific strategic legitimacy) involves a cycle whereby a company establishes, maintains, extends and defends or loses its institutional legitimacy | ||

| Disciplines: social psychology and behavioural economics | ||

| Irani et al.( 90 ) | Schlenker's triangle model of accountability | When individuals and groups in society are held accountable for their actions, citizens can trust that those individuals and groups will follow society's rules, and if the rules are broken, the offenders will be appropriately sanctioned. With regard to genetically engineered foods, when the links between the three components of the model (e.g. prescriptions, events and identify) are strong, consumers will be able to judge industry and government as being accountable for their policies and actions: |

| Social psychology theory | ||

| Draws from a broad range of specific theories for various types of social and cognitive phenomena | ||

| 1. Prescriptions are rules and regulations that govern conduct | ||

| 2. Events are actions and their consequences | ||

| 3. Identity represents the roles and commitments of each group | ||

| Dolan et al.( 91 ) | MINDSPACE framework Nudge theory This theory is grounded in behavioural psychology and economics and was developed Thaler and Sunstein in the book, Nudge: Improving Decisions about Health, Wealth and Happiness (2008). The theory describes how people can potentially be incentivized to make small changes based on their choice architecture, which represents the context in which they make choices, in order to create the circumstances that will encourage them to make the healthy choice the default choice and facilitate desirable lifestyle-related behaviours to support good health | The MINDSPACE framework was proposed by the UK Behavioural Insights Team staff to inform the UK Coalition Government's efforts to improve population health in England. MINDSPACE is an acronym representing the principles of messenger, incentives, norms, defaults, salience, priming, affect, commitment and ego. The MINDSPACE framework is designed to foster personal accountability for individual behaviours, and is intended to improve public accountability for the UK Coalition Government to use public resources efficiently and fairly. The framework acknowledges that elected Members of Parliament and public servants have a key role for being held accountable for their decisions about desirable and undesirable behaviours and the strategies taken by the UK Coalition Government to encourage desirable behaviours that influence health |

| Disciplines: public health policy and law | ||

| Gostin( 92 ) | State public health turning point model Public health law theory This theory, which is rooted in human functioning and democracy theories, is based on the premise that government acts on behalf of the people and gains its legitimacy through the political process where it has a primary responsibility for ensuring the public's health | This framework is grounded in three state principles: power, duty and restraint, and contains five components: |

| 1. The population elects the government and holds the state accountable for a meaningful level of health protection and promotion | ||

| 2. Government prioritizes preventive and population health | ||

| 3. Government enables citizens to take advantage of their social and political rights | ||

| 4. Government partners to protect and promote public health | ||

| 5. Government promotes social justice | ||

| IOM( 93 , 94 ) | Measurement and legal frameworks for public health accountability Public health law theory This theory maintains that laws and public policy are the basis for government authority to implement multisectoral approaches to improve population health. The theory recognizes that changing the conditions to create good health requires the contributions of many sectors and stakeholders | The framework is grounded in the principles that data and information are needed to mobilize action and to hold government and other stakeholders accountable for their actions. It recognizes that governance and related regulatory and funding mechanisms are strong levers to hold all stakeholders accountable for their performance to support population health. The framework applies to the delivery of funded public health programmes by public agencies; the role of public health agencies in mobilizing the public health system; and the roles, contributions and performance of other health system partners (e.g. NGO, private-sector stakeholders and communities) |

OECD, Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development; IOM, Institute of Medicine; NCD, non-communicable disease; EU, European Union; NGO, non-governmental organization; CSR, corporate social responsibility.

Discussion

This section provides a synthesis of the frameworks reviewed. Although accountability has several different theoretical underpinnings and meanings across the disciplines of international relations( 70 – 72 ), trade( 73 ) and development( 74 , 75 ); global governance for health and human rights( 13 , 76 – 81 ); business, finance and social accounting( 82 – 89 ); social psychology and behavioural economics( 90 , 91 ); and public health policy and law( 92 – 94 ), there are common principles across these diverse disciplines.

Responsibility involves individuals, groups, government agencies and business firms acknowledging their commitments and obligations based on social, moral and/or legal standards( 95 ). Accountability entails individuals or stakeholders answering to others empowered with authority to assess how well they have achieved specific tasks or goals and to enforce policies, standards or laws to improve desirable actions and outcomes. Accountability has traditionally entailed gathering information, monitoring and measuring financial or institutional performance against voluntary or mandatory standards, and using information to improve performance( 13 , 70 – 94 ).

Other accountability principles that are similar across existing frameworks are trust, inclusivity, transparency and verification; government leadership and good governance; public deliberations to respond to stakeholders’ interests and concerns; establishing or strengthening independent bodies (e.g. ombudsman or adjudicator); empowering regulatory agencies and using judicial systems to ensure fair and independent assessments; recognizing compliance and performance achievements with incentives (e.g. carrots) and addressing misconduct or non-performance with disincentives (e.g. sticks); and taking remedial actions to improve institutional performance and accountability systems( 13 , 70 – 94 ).

Accountability expectations for partnerships

The literature shows various accountability expectations for transnational alliances and partnerships depending on their purpose( 72 ). Partnerships that raise awareness and advocate for important issues (e.g. Maternal Child Health Integrated Programme) emphasize compliance with rules and regulations, financial accountability and working towards the partnership's mission. Partnerships intended for self-regulation (e.g. Global Reporting Initiative) emphasize transparency and democratic participation. Partnerships for implementing a policy or programme (e.g. Global Alliance for Improved Nutrition) emphasize stakeholders’ performance for clearly defined objectives and performance outcomes. Partnerships used to generate information (e.g. World Action on Salt for Health) emphasize impartiality through professional independence, accuracy and quality( 72 ).

Strengths and limitations of the frameworks reviewed

Of the fifteen accountability frameworks reviewed, ten were developed for the disciplines of international relations, trade and development( 13 , 70 – 77 ), human rights( 79 , 80 ) and global health( 81 ).

One general framework was rooted in business, finance and social accounting( 82 – 89 ). Two were rooted in social psychology( 90 ) and behavioural economics( 91 ); and two were rooted in public health policy and law( 92 – 94 ). None of the frameworks were specific to promoting healthy food environments.

A strength of the public governance framework( 71 ) is the consideration of four concurrent factors (i.e. setting, stakeholders, conduct and obligations of interest) to achieve accountability outcomes. Many other frameworks included elements of a coherent accountability system but none integrated all of the cross-cutting accountability principles identified earlier.

Several limitations were apparent for the WHO and UN System's three-step frameworks to ‘monitor, review and act’ or ‘monitor, remedy and respond’( 79 – 81 ). There is a need to differentiate between ‘remedy’ and ‘respond’ for an empowered authority to hold all stakeholders to account. Moreover, several frameworks lacked an explicit step to make system-wide changes to improve accountability structures based on continuous learning.

A four-step framework would include monitoring enforcement while also improving accountability structures.

Two shared governance frameworks( 13 , 76 – 78 ) supported the concept of ‘mutual accountability’ whereby two or more partners agree to be held responsible for voluntary commitments they make to each other. However, mutual accountability arrangements lack enforcement structures, thereby requiring formal independent accountability mechanisms( 14 , 81 ) to address complex public health problems such as obesity and diet-related NCD( 10 , 11 , 14 , 96 ).

The Institute of Medicine has identified four accountability steps to promote population health( 93 ) that were central to informing our four-step framework and which include:

-

1.

Establish a neutral and arms-length body with a clear charge to accomplish goals;

-

2.

Ensure that the body has authority and capacity to undertake required activities;

-

3.

Measure accomplishments against a clear charge given to the body; and

-

4.

Improve accountability effectiveness by establishing a feedback loop to make system-wide improvements.

The Institute of Medicine identified several accountability challenges( 93 ) such as: the limited ability to attribute the impact of promising interventions to a specific stakeholder group; a long time before an intervention's impact is observed; and the need to assess certain stakeholders’ actions that may concurrently support and undermine population health goals.

Accountability framework to promote healthy food environments

The accountability framework that we developed is based on government appointing an empowered and independent body with a well-defined charge to develop clear objectives, a governance process, performance standards and indicators for all stakeholders to address unhealthy food environments, and to report back on progress. The four-step framework involves taking account (assessment), sharing the account (communication), holding to account (enforcement) and responding to the account (improvements; Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Accountability framework to promote healthy food environments

Although it is a non-linear process, we describe it in a stepwise manner to simplify one's understanding of the accountability dimensions. The governance process should be transparent, credible, verifiable, trustworthy, responsive, fair and timely; and have institutionalized mechanisms to identify and manage conflicts of interest and settle disputes.

Taking the account

This step involves an independent body collecting, reviewing, verifying, monitoring and evaluating meaningful data to establish benchmarks and to analyse each stakeholder's compliance with implementing policies and practices that impact food environments and diet-related population health. Clear reporting expectations and time frames are needed to achieve specific performance goals.

Evidence reviews

UN System bodies, governments and private foundations have appointed expert committees and independent commissions to review public-domain evidence from peer-reviewed and grey literature and trusted advisors( 97 ), NGO and self-reported industry evidence( 55 , 56 , 98 , 99 ), or investment banking firms and contracted auditors who use specific indices that compare and rank company performance for corporate social responsibility indicators within certain sectors( 100 , 101 ).

Monitoring and evaluating policy interventions

The WHO global monitoring framework and action plan to reduce NCD by 25 % by 2025 offers nine voluntary global targets and twenty-five indicators( 3 , 16 ) that will require tailoring to national contexts. INFORMAS( 102 ) is a network of researchers from nine universities across fourteen countries who monitor food environment policy interventions to prevent obesity and diet-related NCD. Government progress can be assessed using the Healthy Food Environment Policy Index( 103 ) and food industry progress can be assessed across seven food environment domains (i.e. composition, labelling, promotion, provision, retail, pricing, and trade and investment) using a prioritized, step-based approach( 104 ).

The Access to Nutrition Index (ATNI) is another independent monitoring effort that rates twenty-five global food and beverage manufacturers on nutrition-related commitments, disclosure practices and performance to address undernutrition and obesity( 105 ). The ATNI used seven indicators (i.e. corporate governance, product portfolio, accessibility of products, marketing practices, support for healthy lifestyles, food labelling and stakeholder engagement) to rate companies for promising or best practice achievements. The 2013 ATNI evaluation found most companies lacked transparency by not publicly sharing their nutrition-related practices and did not adhere to many public commitments( 105 ).

Evaluations of the European Union's (EU) Platform for Action on Diet, Physical Activity and Health revealed that defining clear measurable objectives is essential for policy makers to determine the value of the EU Platform's partnerships( 45 , 106 ). Evaluations of the Pan American Health Organization/WHO Trans Fat Free America initiative found that national governments must coordinate all efforts – including tracking industry reformulation, ensuring mandatory food labelling requirements are consistent across countries, and monitoring changes in the food supply and the dietary intake of populations – to effectively eliminate trans-fats from the food supply in the Latin American and the Caribbean region( 107 , 108 ).

In the USA, private foundations are funding independent evaluations to verify and review progress for private-sector pledges to improve food environments. Examples include the sixteen food manufacturers’ 2010 pledge to remove 1·5 trillion calories from the US food supply by 2015 through the Health Weight Commitment Foundation (Table 1)( 48 , 109 ) and the Partnership for a Healthier America( 110 ).

Sharing the account

This step involves the empowered body communicating results to all stakeholders through a deliberative and participatory engagement process. This step is important to encourage transparency and understanding among stakeholders about the development of the performance standards and accountability expectations; to foster dialogue among stakeholders who hold divergent views and positions on food environment issues; to facilitate shared learning among diverse stakeholders to foster understanding of positions and constraints; to develop timelines for action; and to inform accountability actions at subsequent steps.

Stakeholder engagement can provide insights into accountability needs and challenges related to balancing divergent perspectives. On example is the UK ‘Race to the Top’ project that had convened food retailers and civil society groups to establish sustainability benchmarks( 111 ). The evaluation showed that public-interest NGO viewed the engagement process as too conciliatory whereas the food retailers perceived that there was insufficient consensus building. Participating NGO also criticized the overreliance on food retailers’ self-reported data and the lack of consequences for non-participating companies. On the other hand, food retailers were concerned that their participation in the process would be used to develop a new government regulatory framework to raise expectations about their performance( 111 ).

Holding to account

Holding to account is the most difficult step in the framework because it involves an empowered group appraising and either recognizing successful performers or enforcing policies, regulations and laws for non-participants or under-performers through institutional, financial, regulatory, legal or reputational mechanisms( 70 ). Accountability challenges exist at the international level because treaties, conventions and resolutions have limited sanctioning powers to hold national governments accountable for healthy food environments. The 2010 resolution to reduce unhealthy marketing to children recommended ten actions( 112 ) but the WHO lacks legal authority, oversight or enforcement capacity to compel governments to reduce unhealthy food marketing to children.

National governments can leverage incentives (e.g. tax breaks, investment decisions or praising) and disincentives (e.g. fines, divestment, penalties, litigation, naming or shaming)( 70 ) to hold stakeholders accountable for policies and practices that impact food environments. Some of the most effective voluntary agreements include disincentives and reputational costs for non-participation and sanctions for non-compliance( 70 , 113 ).

Adjudication is another option where a national government can appoint an ombudsman to mediate and manage disputes to avoid litigation and address complex dilemmas arising from power asymmetries among food environment stakeholders( 114 ). In 2013, an independent UK Groceries Code Adjudicator was appointed to ensure that large food retailers will adhere to the Groceries Supply Code of Practice and treat suppliers fairly within legal guidelines( 115 ).

Holding to account also involves public-interest NGO pursuing ‘social accountability goals’( 74 , 75 ) by exposing unacceptable practices such as government corruption and food industry lobbying that undermine public health goals( 116 , 117 ). NGO can utilize disclosure laws that compel governments to release information( 118 ); work with investigative journalists to expose practices that adversely impact food environments and population health( 119 – 121 ); use consumer and company boycotts( 122 – 124 ); use parents’ juries( 125 ); praise companies that meet performance expectations and name or shame non-participating or under-performing businesses( 126 – 128 ); encourage corporations to endorse investors’ statements that recognize health, wellness and nutrition as drivers of future economic-sector growth( 99 , 126 , 129 ); and spearhead shareholder advocacy to change corporate practices( 126 , 130 ) and persist even when resolutions are rejected by company boards( 131 ).

Responding to the account

Responding to the account involves stakeholders taking remedial actions to improve their performance and strengthen systemic accountability structures. This step involves monitoring the fidelity of government policy implementation (which differs from monitoring stakeholders’ compliance with existing policies), as well as government's enforcement of policies, regulations and laws. It also involves assessing how effectively the empowered authority applies incentives and disincentives to promote healthy food environments.

Step 4 involves building stronger internal and external approaches to track a company's performance on commitments and targets. Finally, this step addresses ‘pseudo accountability’, by challenging weak regulations that give an appearance of enforcing high standards but do not lead to meaningful changes( 132 ).

Implications

The proposed accountability framework has several implications. First, it can be used to inform, guide and model private-sector practices to optimize good performance and minimize undesirable or unintended corporate practices. Second, holding to account and responding to the account offer recommendations that have been weak in existing frameworks. Third, the framework encourages stakeholders to explicitly examine power relationships and accountability expectations at all four steps. Fourth, several formal and informal mechanisms are provided for stakeholders to hold each other to account. Finally, the proposed framework requires empirical testing for relevant issues, and especially to evaluate whether the accountability structures of voluntary partnerships can be strengthened to improve credibility, quality of engagement and produce a positive impact on healthy food environments.

Conclusions

National governments’ reliance on food industry partnerships to develop and implement policies to address unhealthy food environments requires explicit, transparent and independent accountability structures. The proposed accountability framework involves an empowered body developing clear objectives, a governance process and performance standards for all stakeholders to promote healthy food environments. The body takes account (assessment), shares the account (communication), holds to account (enforcement) and responds to the account (improvements). The governance process must be transparent, credible, verifiable, trustworthy, responsive, fair and timely, and manage conflicts of interest and settle disputes. The proposed framework requires empirical testing to evaluate whether the accountability structures can be strengthened to improve partnership credibility, engagement and impact on healthy food environments within a broader government-led strategy to address obesity and diet-related NCD.

Acknowledgements

Sources of funding: This paper was supported by the World Health Collaborating Centre for Obesity Prevention and the Population Health Strategic Research Centre at Deakin University in Melbourne, Victoria, Australia. V.I.K. received PhD research support from Deakin University's World Health Collaborating Centre for Obesity Prevention and the Population Health Strategic Research Centre to complete this paper, and otherwise has no financial disclosures. B.S., M.L. and P.H. have no financial disclosures. Conflicts of interest: V.I.K., B.S., M.L. and P.H. have no conflict of interest related to the content in this paper. Ethics approval: This study was a desk review of the literature and did not involve human subjects; therefore ethics approval was not required. Authors’ contributions: V.I.K. developed the initial concept, conducted the literature review, wrote the first draft, coordinated feedback for subsequent revisions and led the submission process. B.S., M.L. and P.H. further developed the concepts and provided feedback on drafts of the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. Acknowledgements: The authors are grateful to Juan Quirarte for designing Figs 1 and 2.

References

- 1. World Health Organization (2011) Global Status Report on Noncommunicable Diseases 2010. Geneva: WHO; available at http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2011/9789240686458_eng.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 2. World Health Organization (2004) Global Strategy on Diet, Physical Activity, and Health. Report no. WHA57.17. Geneva: WHO; available at http://www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/strategy/eb11344/en/index.html [Google Scholar]

- 3. World Health Organization (2013) Follow-up to the Political Declaration of the High-level Meeting of the General Assembly on the Prevention and Control of Non-communicable Diseases, 25 May. http://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA66/A66_R10-en.pdf (accessed May 2013).

- 4. World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research (2007) Food, Nutrition, Physical Activity and the Prevention of Cancer: A Global Perspective. Washington, DC: AICR; available at http://www.dietandcancerreport.org/downloads/summary/english.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 5. European Heart Network (2011) Diet, Physical Activity and Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Europe. Brussels: EHN; available at http://www.ehnheart.org/publications/publications.html [Google Scholar]

- 6. World Health Organization (2011) Intersectoral Action on Health. A Path for Policy-Makers to Implement Effective and Sustainable Action on Health. Kobe: WHO Centre for Health Development; available at http://www.who.int/kobe_centre/publications/ISA-booklet_WKC-AUG2011.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 7. Committee on Preventing Obesity in Children and Youth, Institute of Medicine (2005) Preventing Childhood Obesity: Health in the Balance [JP Koplan, CT Liverman and VI Kraak, editors]. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; available at http://www.nap.edu/catalog.php?record_id=11015 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Swinburn BA, Sacks G, Hall KD et al. (2011) The global obesity pandemic: shaped by global drivers and local environments. Lancet 378, 804–814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Conflicts of Interest Coalition (2011) Statement of Concern. http://info.babymilkaction.org/sites/info.babymilkaction.org/files/COIC150_0.pdf (accessed April 2013).

- 10. Moodie R, Stuckler D, Monteiro C et al. (2013) Profits and pandemics: prevention of harmful effects of tobacco, alcohol, and ultra-processed food and drink industries. Lancet 381, 670–679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. World Health Organization (2013) WHO Director-General addresses health promotion conference. Opening address at the 8th Global Conference on Health Promotion, Helsinki, Finland, 10 June. http://www.who.int/dg/speeches/2013/health_promotion_20130610/en/index.html (accessed June 2013).

- 12. Brandeis LD (1913) What publicity can do. Harper's Weekly, 20 December. http://www.law.louisville.edu/library/collections/brandeis/node/196 (accessed May 2013).

- 13. Rochlin S, Zadek S & Forstater M (2008) Governing Collaboration. Making Partnerships Accountable for Delivering Development. London: AccountAbility; available at http://www.accountability.org/images/content/4/3/431/Governing%20Collaboration_Full%20report.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 14. Muntaner C, Ng E & Chung H (2012) Making power visible in global health governance. Am J Bioeth 12, 63–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Beaglehole R, Bonita R & Horton R (2013) Independent global accountability for NCDs. Lancet 381, 602–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. World Health Organization (2013) United Nations to establish WHO-led Interagency Task Force on the Prevention and Control of Noncommunicable Diseases. Media release, 22 July. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/notes/2013/ncds_ecosoc_20130722/en/index.html (accessed August 2013).

- 17. McKinnon RA, Reedy J, Morrissette MA et al. (2009) Measures of the food environment: a compilation of the literature, 1990–2007. Am J Prev Med 36, 4 Suppl., S124–S133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Glanz K (2009) Measuring food environments: a historical perspective. Am J Prev Med 36, 4 Suppl., S93–S98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ball K & Thornton L (2013) Food environments: measuring, mapping, monitoring and modifying. Public Health Nutr 16, 1147–1150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Story M, Kaphingst KM, Robinson-O'Brien R et al. (2008) Creating healthy food and eating environments: policy and environmental approaches. Annu Rev Public Health 29, 253–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Swinburn B, Egger G & Raza F (1999) Dissecting obesogenic environments: the development and application of a framework for identifying and prioritizing environmental interventions for obesity. Prev Med 29, 563–570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Committee on Progress in Preventing Childhood Obesity, Institute of Medicine (2007) Progress in Preventing Childhood Obesity: How Do We Measure Up? [JP Koplan, CT Liverman, VI Kraak et al., editors]. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; available at http://www.nap.edu/catalog.php?record_id=11722 [Google Scholar]

- 23. US Department of Agriculture & US Department of Health and Human Services (2010) Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2010, 7th edition. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office; available at http://www.cnpp.usda.gov/Publications/DietaryGuidelines/2010/PolicyDoc/PolicyDoc.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mozaffarian D, Afshin A, Benowitz NL et al. (2012) Population approaches to improve diet, physical activity, and smoking habits: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 126, 1514–1563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Pérez-Escamilla R, Obbagy JE, Altman JM et al. (2012) Dietary energy density and body weight in adults and children: a systematic review. J Acad Nutr Diet 112, 671–684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lin BH & Guthrie J (2012) Nutritional Quality of Food Prepared at Home and Away From Home, 1977–2008. Economic Information Bulletin no. EIB-105. Washington, DC: US Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service; available at http://www.ers.usda.gov/media/977761/eib-105.pdf

- 27. Popkin BM, Duffey K & Gordon-Larsen P (2005) Environmental influences on food choice, physical activity and energy balance. Physiol Behav 86, 603–613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lozano R, Naghavi M, Foreman K et al. (2012) Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 380, 2095–2128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lim SS, Vos T, Flaxman AD et al. (2012) A comparative risk assessment of burden of disease and injury attributable to 67 risk factors and risk factor clusters in 21 regions, 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 380, 2224–2260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Guthman J (2008) Thinking inside the neoliberal box: the micro-politics of agro-food philanthropy. Geoforum 39, 1241–1253. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Clarke J (2004) Dissolving the public realm?: the logics and limits of neo-liberalism. J Soc Policy 33, 27–48. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Peck J & Tickell A (2002) Neoliberalizing space. Antipode 34, 380–404. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wilst WH (2011) Citizens United, public health, and democracy: the Supreme Court ruling, its implications, and proposed action. Am J Public Health 101, 1172–1179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Piety TR (2011) Citizens United and the threat to the regulatory state. Michigan Law Review First Impressions 109, 16–22. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Clapp J & Fuchs D (2009) Agrifood corporations, global governance, and sustainability: a framework for analysis. In Corporate Power in Global Agrifood Governance, pp. 1–28 [J Clapp & D Fuchs, editors]. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Mindell JS, Reynolds L, Cohen DL et al. (2012) All in this together: the corporate capture of public health. BMJ 345, e8082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Bonnell C, McKee M, Fletcher A et al. (2011) Nudge smudge: UK government misrepresents ‘nudge’. Lancet 377, 2158–2159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kraak VI, Harrigan P, Lawrence M et al. (2012) Balancing the benefits and risks of public–private partnerships to address the global double burden of malnutrition. Public Health Nutr 15, 503–517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kraak VI, Swinburn B, Lawrence M et al. (2011) The accountability of public–private partnerships with food, beverage and restaurant companies to address global hunger and the double burden of malnutrition. SCN News issue 39, 11–24; available at http://www.unscn.org/files/Publications/SCN_News/SCNNEWS39_10.01_high_def.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 40. Watzman N (2012) Congressional Letter Writing Campaign Helps Torpedo Voluntary Food Marketing Guidelines for Kids. Washington, DC: Sunlight Foundation Reporting Group; available at http://reporting.sunlightfoundation.com/2012/congressional_letter_writing_campaign/ [Google Scholar]

- 41. Yanamadala S, Bragg MA, Roberto CA et al. (2012) Food industry front groups and conflicts of interest: the case of Americans Against Food Taxes. Public Health Nutr 15, 1331–1332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Grynbaum MM (2013) In N.A.A.C.P. industry gets ally against soda ban. The New York Times, 23 January. http://www.nytimes.com/2013/01/24/nyregion/fight-over-bloombergs-soda-ban-reaches-courtroom.html?ref=health&_r=1& (accessed April 2013).

- 43. International Food and Beverage Alliance (2013) Our Commitments. https://www.ifballiance.org/our-commitments.html (accessed April 2013).

- 44. Cereal Partners Worldwide SA, Nestlé and General Mills (2009) CPW Commitments. http://www.cerealpartners.com/cpw/euPledge.html (accessed April 2013).

- 45. European Commission (2013) Public Health. Nutrition and Physical Activity. The EU Platform for Action on Diet, Physical Activity and Health. http://ec.europa.eu/health/nutrition_physical_activity/publications/index_en.htm (accessed April 2013).

- 46. Van Koperen TM, Jebb SA, Summerbell CD et al. (2013) Characterizing the EPODE logic model: unravelling the past and informing the future. Obes Rev 14, 162–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Pan American Health Organization/World Health Organization (2008) Healthy Oils and the Elimination of Industrially Produced Fatty Acids in the Americas. Washington DC: PAHO; available at http://www.healthycaribbean.org/nutrition_and_diet/documents/TransFats.pdf

- 48. US Healthy Weight Commitment Foundation (2013) Home page. http://www.healthyweightcommit.org/ (accessed April 2013).

- 49. UK Department of Health (2013) Public Health Responsibility Deal. https://responsibilitydeal.dh.gov.uk/ (accessed April 2013).

- 50. Australia Food and Grocery Council (2012) Healthier Australia Commitment. http://www.togethercounts.com.au/healthy-australia-commitment/ (accessed April 2013).

- 51. Facts Up Front (2013) Facts Up Front nutrition education initiative launches digital platform to help Americans make informed decisions when they shop for food. A Joint initiative of the Grocery Manufacturers Association and the Food Marketing Institute. Press release, 17 April. http://www.factsupfront.org/Newsroom/6 (accessed April 2013).

- 52. Better Business Bureau (2013) US Children's Food and Beverage Advertising Initiative. http://www.bbb.org/us/childrens-food-and-beverage-advertising-initiative/ (accessed April 2013).

- 53. Advertising Standards Canada (2013) Canadian Children's Food and Beverage Advertising Initiative. http://www.adstandards.com/en/childrensinitiative/default.htm (accessed April 2013).

- 54. International Food & Beverage Alliance (2011) Five Commitments to Action in support of the World Health Organization's 2004 Global Strategy on Diet, Physical Activity and Health. 2011 Progress Report. https://www.ifballiance.org/sites/default/files/IFBA%20Progress%20Report%202011%20%28FINAL%2029%204%202012%29.pdf (accessed April 2013).

- 55. Accenture (2012) 2011 Compliance Monitoring Report for the International Food & Beverage Alliance on Global Advertising on Television, Print and Internet. https://www.ifballiance.org/sites/default/files/IFBA%20Accenture%20Monitoring%20Report%202011%20FINAL%20010312.pdf (accessed April 2013).

- 56. Vladu C, Christensen R & Pana A (2012) Monitoring the European Platform for action on Diet, Physical Activity and Health activities. Annual Report 2012. Brussels: IBF International Consulting; available at http://ec.europa.eu/health/nutrition_physical_activity/docs/eu_platform_2012frep_en.pdf

- 57. Union of Concerned Scientists (2012) Heads They Win, Tails We Lose. How Corporations Corrupt Science at the Public's Expense. Cambridge, MA: UCS Publications; available at http://www.ucsusa.org/assets/documents/scientific_integrity/how-corporations-corrupt-science.pdf

- 58. European Court of Auditors (2012) Management of Conflicts of Interest in Selected EU Agencies. Special report no. 15. Luxembourg: European Court of Auditors; available at http://eca.europa.eu/portal/pls/portal/docs/1/17190743.PDF

- 59. Freudenberg N & Galea S (2008) The impact of corporate practices on health: implications for health policy. J Public Health Policy 29, 86–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Wilst WH (2006) Public health and the anticorporate movement: rationale and recommendations. Am J Public Health 96, 1370–1375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Stuckler D, McKee M, Ebrahim S et al. (2012) Manufacturing epidemics: the role of global producers in increased consumption of unhealthy commodities including processed foods, alcohol, and tobacco. PLoS Med 9, e1001235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Brownell KD & Warner KE (2009) The perils of ignoring history: Big Tobacco played dirty and millions died. How similar is Big Food? Milbank Q 87, 259–294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Which? (2012) Government must do more to tackle the obesity crisis, says Which? The Government's Responsibility Deal is inadequate. Press release, 15 March. http://www.which.co.uk/news/2012/03/government-must-do-more-to-tackle-the-obesity-crisis-says-which-281403/ (accessed April 2013).

- 64. Ludwig DS & Nestle M (2008) Can the food industry play a constructive role in the obesity epidemic? JAMA 300, 1808–1811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Brownell KD (2012) Thinking forward: the quicksand of appeasing the food industry. PLoS Med 9, e1001254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Lumley J, Martin J & Antonopoulos N (2012) Exposing the Charade: The Failure to Protect Children from Unhealthy Food Advertising. Melbourne: Obesity Policy, Coalition; available at http://www.aana.com.au/data/AANA_in_the_News/OPC_Exposing_the_Charade_report_2012.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 67. Batada A (2013) Kids’ Meals: Obesity on the Menu. Washington, DC: Center for Science in the Public Interest; available at http://cspinet.org/new/pdf/cspi-kids-meals-2013.pdf

- 68. Hawkes C & Harris JL (2011) An analysis of the content of food industry pledges on marketing to children. Public Health Nutr 14, 1403–1414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Sharma LL, Teret SP & Brownell KD (2010) The food industry and self-regulation: standards to promote success and to avoid public health failures. Am J Public Health 100, 240–246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Grant RW & Keohane RO (2005) Accountability and abuses of power in world politics. Am Polit Sci Rev 99, 29–43. [Google Scholar]

- 71. Bovens M (2007) Analysing and assessing accountability: a conceptual framework. Eur Law J 13, 447–468. [Google Scholar]

- 72. Steets J (2010) Accountability in Public Policy Partnerships. UK: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- 73. Wolfe R & Baddeley S (2012) Regulatory Transparency in Multilateral Agreements Controlling Exports of Tropical Timber, E-waste and Conflict Diamonds. OECD Trade Policy Papers no. 141. 10.1787/5k8xbn83xtmr-en (accessed April 2013). [DOI]

- 74. Joshi A (2013) Context Matters: A Causal Chain Approach to Unpacking Social Accountability Interventions. Brighton: Institute of Development Studies; available at http://www.ids.ac.uk/files/dmfile/ContextMattersaCasualChainApproachtoUnpackingSAinterventionsAJoshi2013.pdf

- 75. O'Meally SC (2013) Mapping Context for Social Accountability: A Resource Paper. Washington, DC: The World Bank, Social Development Department; available at http://siteresources.worldbank.org/EXTSOCIALDEVELOPMENT/Resources/244362-1193949504055/Context_and_SAcc_RESOURCE_PAPER.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 76. Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (2009) Mutual Accountability: Emerging Good Practice. http://www.oecd.org/dac/aideffectiveness/49656340.pdf (accessed April 2013).

- 77. Steer L & Wanthe C (2009) Mutual Accountability at Country Level: Emerging Good Practice. ODI Background Note, April 2009. London: Overseas Development Institute; available at http://www.aideffectiveness.org/media/k2/attachments/3277_1.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 78. Ruger JP (2012) Global health governance as shared health governance. J Epidemiol Community Health 66, 653–661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. World Health Organization (2011) Keeping Promises, Measuring Results. Geneva: WHO Commission on Information and Accountability for Women's and Children's Health; available at http://www.who.int/topics/millennium_development_goals/accountability_commission/Commission_Report_advance_copy.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 80. United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner (2011) Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights. Implementing the United Nations ‘Protect, Respect and Remedy’ Framework. http://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Publications/GuidingPrinciplesBusinessHR_EN.pdf (accessed April 2013).

- 81. Bonita R, Magnusson R, Bovet P et al. (2013) Country actions to meet UN commitments on non-communicable diseases: a stepwise approach. Lancet 381, 575–584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Deegan C (2002) The legitimizing effect of social and environmental disclosures – a theoretical foundation. Account Audit Accountability J 15, 282–311. [Google Scholar]

- 83. Isles A (2007) Seeing sustainability in business operations: US and British food retailer experiments with accountability. Bus Strat Environ 16, 290–301. [Google Scholar]

- 84. Moerman L & Van Der Laan S (2005) Social reporting in the tobacco industry: all smoke and mirrors? Account Audit Accountability J 18, 374–389. [Google Scholar]

- 85. Newell P (2008) Civil society, corporate accountability and the politics of climate change. Global Environ Polit 8, 122–153. [Google Scholar]

- 86. Stanwick PA, Stanwick SD (2006) Environment sustainability disclosures: a global perspective and financial performance. In Corporate Social Responsibility. vol. 2: Performance and Stakeholders, pp. 84–104 [J Allouche, editor]. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- 87. Swift T (2001) Trust, reputation and corporate accountability to stakeholders. Bus Ethics Eur Rev 10, 16–26. [Google Scholar]

- 88. Tilling MV & Tilt CA (2010) The edge of legitimacy: voluntary social reporting in Rothmans’ 1956–1999 annual reports. Account Audit Accountability J 23, 55–81. [Google Scholar]

- 89. Tilt CA (2010) Corporate responsibility, accounting and accountants. In Professionals’ Perspectives of Corporate Social Responsibility, pp. 11–32 [SO Idowu and WL Filho, editors]. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; available at http://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007%2F978-3-642-02630-0_2

- 90. Irani T, Sinclair J & O'Malley M (2002) The importance of being accountable: the relationship between perceptions of accountability, knowledge, and attitude toward plant genetic engineering. Sci Commun 23, 225–242. [Google Scholar]

- 91. Dolan P, Hallsworth M, Halpern D et al. (2010) MINDSPACE: Influencing Behaviour Through Public Policy. London: Institute for Government; available at http://www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publications/2/ [Google Scholar]

- 92. Gostin LO (2008) A theory and definition of public health law (Georgetown University/O'Neill Institute for National & Global Health Law Scholarship Research Paper no. 8). In Public Health Law Power, Duty and Restraint, revised and expanded 2nd ed., pp. 3–41 [LO Gostin, editor]. Berkley, CA: University of California Press/Millbank Memorial Fund; available at http://ssrn.com/abstract=1269472

- 93. Institute of Medicine, Committee on Public Health Strategies to Improve Health (2011) For the Public's Health: The Role of Measurement in Action and Accountability. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; available at http://www.nap.edu/catalog.php?record_id=13005

- 94. Institute of Medicine, Committee on Public Health Strategies to Improve Health (2011) For the Public's Health: Revitalizing Law and Policy to Meet New Challenges. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; available at http://www.iom.edu/Reports/2011/For-the-Publics-Health-Revitalizing-Law-and-Policy-to-Meet-New-Challenges.aspx

- 95. Turoldo F (2009) Responsibility as an ethical framework for public health interventions. Am J Public Health 99, 1197–1202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. World Health Organization (2013) Key issues for the development of a policy on engagement with nongovernmental organizations. Report by the Director-General. EB 132/5 Add.2, 18 January. http://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/EB132/B132_5Add2-en.pdf (accessed April 2013).