Abstract

Objective

To examine the association of breakfast consumption with objectively measured and self-reported physical activity, sedentary time and physical fitness.

Design

The HELENA (Healthy Lifestyle in Europe by Nutrition in Adolescence) Cross-Sectional Study. Breakfast consumption was assessed by two non-consecutive 24 h recalls and by a ‘Food Choices and Preferences’ questionnaire. Physical activity, sedentary time and physical fitness components (cardiorespiratory fitness, muscular fitness and speed/agility) were measured and self-reported. Socio-economic status was assessed by questionnaire.

Setting

Ten European cities.

Subjects

Adolescents (n 2148; aged 12·5–17·5 years).

Results

Breakfast consumption was not associated with measured or self-reported physical activity. However, 24 h recall breakfast consumption was related to measured sedentary time in males and females; although results were not confirmed when using other methods to assess breakfast patterns or sedentary time. Breakfast consumption was not related to muscular fitness and speed/agility in males and females. However, male breakfast consumers had higher cardiorespiratory fitness compared with occasional breakfast consumers and breakfast skippers, while no differences were observed in females. Overall, results were consistent using different methods to assess breakfast consumption or cardiorespiratory fitness (all P ≤ 0·005). In addition, both male and female breakfast skippers (assessed by 24 h recall) were less likely to have high measured cardiorespiratory fitness compared with breakfast consumers (OR = 0·33; 95 % CI 0·18, 0·59 and OR = 0·56; 95 %CI 0·32, 0·98, respectively). Results persisted across methods.

Conclusions

Skipping breakfast does not seem to be related to physical activity, sedentary time or muscular fitness and speed/agility as physical fitness components in European adolescents; yet it is associated with both measured and self-reported cardiorespiratory fitness, which extends previous findings.

Keywords: Physical activity, Sedentarism, Aerobic capacity, Muscular strength, Speed/agility

Skipping breakfast has been associated with less healthful lifestyle behaviours, including poorer overall dietary quality or food choices and inactive lifestyle, in adolescents( 1 – 4 ). The amount of energy available early in the morning may have an impact on adolescents’ physical activity levels in the first part of the day( 5 , 6 ). Several studies showed that adolescents who consumed breakfast regularly were more likely to be physically active compared with their skipper counterparts( 6 – 8 ). In contrast, other studies did not observe a significant relationship between breakfast consumption and physical activity( 2 , 3 , 5 ). These contradictory findings may be in part due to the different methodology used to assess physical activity (accelerometry v. questionnaire). The definition of breakfast consumption and the methodology used also vary across studies. In addition, there is no consensus regarding the best tool to assess breakfast patterns. Thus, studies examining whether the observed associations persist when using different methodologies are warranted. The HELENA (Healthy Lifestyle in Europe by Nutrition in Adolescents) Study( 9 ) includes data on two different methods to assess breakfast consumption in European adolescents: two non-consecutive 24 h recalls and the ‘Food Choices and Preferences’ questionnaire, as well as data on objectively measured and self-reported physical activity and sedentary time. Therefore, we were able to examine the association of breakfast consumption with physical activity and sedentary time using two different methods of measuring these variables.

A higher physical activity level has been associated with higher physical fitness, which is a health marker in children and adolescents( 10 , 11 ). Thus, to study if breakfast consumption is associated with a health marker in young people is of public health interest. Sandercock et al. showed that males (10–16 years) who consumed breakfast regularly presented high levels of cardiorespiratory fitness, while no differences were observed in females( 6 ). Previous findings from the HELENA Study showed that regular breakfast consumption, as assessed by the ‘Food Choices and Preferences’ questionnaire, was associated with a healthier cardiovascular profile, which included objectively measured cardiorespiratory fitness as a health marker, in European adolescents( 12 ). However, the relationship among breakfast and other health-related physical fitness components such as muscular fitness and speed/agility have not been previously studied. The present study aimed to add to our previous study by: (i) using a different method to assess breakfast consumption, namely 24 h recall; (ii) including a subjective (self-reported) measure of cardiorespiratory fitness assessed by the International Fitness Scale (IFIS)( 13 ); and (iii) analysing other physical fitness components such as muscular fitness and speed/agility.

The major contribution of the present study to our previous study and the existing literature is to provide more explanatory information about the association of breakfast with physical activity and sedentary time among measurement methods. Therefore, the aims of the present study were: (i) to examine the association of two different methods to assess breakfast consumption with objectively measured and self-reported physical activity and sedentary time; and (ii) to study the association of breakfast consumption with physical fitness components including cardiorespiratory fitness, muscular fitness and speed/agility, both measured and self-reported, in European adolescents participating in the HELENA Study.

Materials and methods

Study design

Data were derived from the HELENA Cross-Sectional Study (HELENA-CSS). HELENA-CSS is a multi-centre study conducted in ten European cities. A total of 3528 adolescents (age range 12·5–17·5 years) were assessed at schools between 2006 and 2007( 14 ). All procedures involving human participants were approved by the Ethics Committee of each city involved( 15 ). Written informed consent was obtained from both adolescents and their parents.

Assessment of self-reported breakfast habit

Breakfast habit was assessed by both a computerized tool for self-reported 24 h recalls (HELENA-DIAT (Dietary Assessment Tool)) and the ‘Food Choices and Preferences’ questionnaire.

The 24 h recall was conducted on two non-consecutive days. Adolescents completed the program autonomously in the computer classroom during school time( 16 ) assisted by field workers. The program is built up around six meal occasions (i.e. breakfast, morning snacks, lunch, afternoon snacks, evening meal, evening snacks) with questions that help adolescents to remember what they ate. A question asked if they had breakfast. If they responded no, the adolescents were prompted to an additional question to confirm that they didn't eat anything for breakfast: ‘You didn't have anything, although small, to eat or drink for breakfast?’ If the adolescents had breakfast, a drink or something small, they were asked: ‘Where and with whom did you have breakfast yesterday?’ and ‘Around what time was that?’ Then the adolescents selected the food items consumed from a culturally adapted list and finally they described the quantity consumed by choosing among different pictures. A validation study indicated that the YANA-C (Young Adolescents’ Nutrition Assessment on Computer), a former version of the HELENA-DIAT, showed good agreement with an interviewer-administered YANA-C interview (κ = 0·48–0·92 and 0·38–0·90 for food records and 24 h dietary recall interviews, respectively)( 17 ) and that it is a good method to collect detailed dietary information from adolescents( 16 ). We categorized adolescents into three groups as follows: (i) ‘consumer’ if they consumed breakfast on the two 24 h recall days; (ii) ‘occasional consumer’ if they consumed breakfast on one recall day; and (iii) ‘skipper’ if they did not consume breakfast on either of the recall days.

The ‘Food Choices and Preferences’ questionnaire was developed based on forty-four focus groups which explored attitudes and issues of concern among adolescents regarding food choices, preferences, healthy eating and lifestyle( 18 ). Breakfast consumption was assessed based on agreement with the statement: ‘I often skip breakfast’, with seven answer categories from strongly disagree (= 1) to strongly agree (= 7). Then adolescents were categorized into three groups in accordance with Hallström et al.( 12 ): (i) ‘consumer’ if they answered 1 or 2; (ii) ‘occasional consumer’ if they answered 3 to 5; and (iii) ‘skipper’ if they answered 6 or 7.

Assessment of objectively measured and self-reported physical activity and sedentary time

Physical activity and sedentary time were measured during seven consecutive days using accelerometers (Actigraph GT1M; Manufacturing Technology Inc., Pensacola, FL, USA). Adolescents wore the accelerometers on the lower back during the waking hours. Data were saved in 15 s intervals (epochs). Data with periods of continuous zero values for more than 20 min were considered ‘accelerometer non-wear’ periods and were therefore excluded from the analyses. Likewise, registers of more than 20 000 counts per minute were interpreted as a potential malfunction of the accelerometer and were also excluded from the analyses. Data were considered valid if the adolescents had accelerometer counts for at least 3 d with at least 8 h of recording time per day( 19 ). Physical activity variables included in the present study were: sedentary time and moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA) in minutes per day (min/d) and total physical activity in counts per minute (cpm). Sedentary time and MVPA were calculated according to the standardized cut-off point of <100 and ≥2000 cpm, respectively( 19 , 20 ). MVPA was dichotomized into <60 min/d (not meeting the physical activity recommendation) and ≥60 min/d (meeting the recommendation) according to the WHO guidelines( 21 ).

Patterns of physical activity were also self-reported using the International Physical Activity Questionnaire for Adolescents (IPAQ-A)( 22 ). IPAQ-A covers four domains of physical activity: (i) school-related physical activity (including activity during physical education classes and breaks); (ii) transportation; (iii) housework; and (iv) activities during leisure time. In each of the four domains, the time periods per day (and the numbers of days per week) involved in activities were recorded. Data were cleaned and truncated( 23 ) and afterwards classified into light (i.e. walking), moderate and vigorous activity according to the guidelines for data processing and analyses of IPAQ (http://www.ipaq.ki.se/ipaq.htm). Physical activity variables included in the present study were: MVPA and total physical activity (walking + MVPA intensities) as min/d. Habitual sedentary time was estimated by the self-reported HELENA sedentary behaviour questionnaire( 24 , 25 ). The HELENA sedentary behaviour questionnaire includes daily minutes of the following sedentary items: television viewing, playing with computer games, playing with console games, use of Internet for non-study reasons, use of Internet for study and studying/homework (lessons not included). The average time spent per day in those sedentary activities was calculated.

Assessment of objectively measured and self-reported physical fitness

Physical fitness was measured by the following components: cardiorespiratory fitness, muscular fitness and speed/agility. A full description of the tests used has been published previously( 26 ). Briefly, we assessed cardiorespiratory fitness by the 20 m shuttle run test; upper-body muscular strength by the handgrip strength test; lower-body muscular strength by the standing broad jump test; and speed/agility by the 4 × 10 m shuttle run test( 26 ). The equation reported by Leger et al.( 27 ) was used to estimate VO2max (ml/kg per min) from the 20 m shuttle run test scores. Participants were classified into low and high cardiorespiratory fitness levels according to the FITNESSGRAM Standards for the Healthy Fitness Zones( 28 ). The FITNESSGRAM proposed one threshold for boys and three thresholds for girls based on age, since VO2max (expressed in relative terms) is stable across the adolescence period in boys but decreases progressively in girls. Boys with a VO2max of 42 ml/kg per min or higher were classified as having a high cardiorespiratory fitness level. Girls aged 12 and 13 years with a VO2max of 37 and 36 ml/kg per min or higher, respectively, were classified as having a high cardiorespiratory fitness level. Girls aged 14 years or older with a VO2max of 35 ml/kg per min or higher were classified as having a healthy cardiorespiratory fitness level. Upper-body muscular strength was expressed as mean handgrip right and left divided by weight and lower-body muscular strength was expressed as maximum distance achieved (in centimetres) in the standing broad jump test. Speed/agility was shown by the minimum time (in seconds) for completion of the 4 × 10 m shuttle run test. All tests were performed twice and the best score was retained, while the 20 m shuttle run test was performed only once.

Also, subjective physical fitness was assessed using a single-response item included in the IFIS (www.helenastudy.com/IFIS)( 13 ). Possible answers ranged from 1 to 5, which correspond to ‘very poor’, ‘poor’, ‘average’, ‘good’ and ‘very good’, respectively. Participants were categorized into two groups: ‘low cardiorespiratory fitness’ if they answered 1 to 3 and ‘high cardiorespiratory fitness’ if they answered 4 or 5.

Assessment of socio-economic status

Adolescents completed a self-reported questionnaire developed to collect data about socio-economic status( 29 ) during classroom time( 3 ). The questionnaire contained information about the educational level of parents and family affluence. Parent's educational level was categorized into the following levels: elementary education, lower-secondary education, higher secondary education and high education or university degree. Family affluence was estimated using a modified version of the Family Affluence Scale (FAS), a scale developed by the WHO collaborative Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC) Study( 30 ). A sum score of the following items was used: whether the adolescent had his/her own bedroom, the number of cars in the family, the number of computers and the presence of an Internet connection at home.

Data analyses

We studied the association of breakfast consumption (i.e. consumer, occasional consumer and skipper) with physical activity, sedentary time and physical fitness using multilevel analysis. Breakfast consumption was entered in the analysis as the independent variable, with physical activity, sedentary time and physical fitness components as dependent variables, and centre (random intercept), age, parent's education as well as family affluence as covariates. All analyses were performed with the two different methods to assess breakfast patterns, (i) the computer-based tool for 24 h recalls and (ii) the ‘Food Choices and Preferences’ questionnaire, and with measured and self-reported physical activity, sedentary time and physical fitness. The level of statistical significance was controlled for multiple testing (0·05/number of tests = 0·05/10 = 0·005); therefore, results were considered statistically significant when P ≤ 0·005.

The associations between breakfast consumers and compliance with the physical activity recommendations (MVPA of at least 60 min/d) and high cardiorespiratory fitness level (FITNESSGRAM Standards for the Healthy Fitness Zones), both measured and self-reported, were examined by binary logistic regression analysis, after controlling for centre, age, parent's education and family affluence. All analyses were conducted using the statistical software PASW for Windows version 18.

Results

Table 1 shows breakfast consumption categories and mean estimates of measured and self-reported physical activity and sedentary time by gender in European adolescents. No differences were observed across breakfast consumption categories (assessed by 24 h recall or the ‘Food Choices and Preferences’ questionnaire) and mean estimates of measured and self-reported physical activity after adjusting for multiple comparisons (Table 1). There was an association between breakfast consumption and sedentary time in both males and females, yet the results were not consistent when considering the different methods used in males or females. Using the computer-based tool for 24 h recalls to assess breakfast patterns and measured sedentary time, male breakfast consumers spent on average ∼2 % more time in sedentary time compared with occasional breakfast consumers, yet they spent on average ∼8 % less time in sedentary time compared with breakfast skippers (P = 0·003). While using the ‘Food Choices and Preferences’ questionnaire to assess breakfast consumption and self-reported sedentary time, female breakfast consumers spent on average ∼4 % less time in sedentary time compared with occasional breakfast consumers; however, they spent on average ∼13 % more time in sedentary time compared with breakfast skippers (P = 0·004; Table 1).

Table 1.

Association of breakfast consumption categories with objectively measured and self-reported physical activity by sex in European adolescents (n 2148) aged 12·5–17·5 years, HELENA (Healthy Lifestyle in Europe by Nutrition in Adolescence) Cross-Sectional Study, 2006–2007

| Males | Females | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | se | P | Mean | se | P | |

| Breakfast consumption categories assessed by 24 h recall | ||||||

| Measured PA | ||||||

| MVPA (min/d) | ||||||

| Consumer | 66·1 | 2·0 | 50·8 | 2·1 | ||

| Occasional | 68·0 | 3·0 | 0·706 | 53·5 | 2·6 | 0·153 |

| Skipper | 64·7 | 4·3 | 54·7 | 3·3 | ||

| Total PA (cpm) | ||||||

| Consumer | 485·1 | 13·7 | 387·0 | 14·0 | ||

| Occasional | 503·6 | 20·2 | 0·294 | 395·1 | 16·9 | 0·189 |

| Skipper | 457·6 | 28·5 | 417·6 | 21·9 | ||

| Sedentary time (min/d) | ||||||

| Consumer | 538·9 | 7·4 | 549·0 | 7·8 | ||

| Occasional | 526·3 | 11·1 | 0·003 | 554·9 | 9·7 | 0·368 |

| Skipper | 583·3 | 15·7 | 538·2 | 12·7 | ||

| Self-reported PA | ||||||

| MVPA (min/d) | ||||||

| Consumer | 115·6 | 9·8 | 90·2 | 9·2 | ||

| Occasional | 114·4 | 11·3 | 0·876 | 94·3 | 10·4 | 0·638 |

| Skipper | 110·1 | 14·0 | 86·0 | 12·0 | ||

| Total PA (min/d) | ||||||

| Consumer | 172·7 | 12·5 | 154·6 | 13·2 | ||

| Occasional | 181·5 | 14·5 | 0·515 | 161·1 | 14·8 | 0·696 |

| Skipper | 166·1 | 17·9 | 150·1 | 17·1 | ||

| Sedentary time (min/d) | ||||||

| Consumer | 64·6 | 4·9 | 81·8 | 6·9 | ||

| Occasional | 53·9 | 6·2 | 0·081 | 79·1 | 8·1 | 0·163 |

| Skipper | 59·7 | 8·3 | 67·6 | 9·8 | ||

| Breakfast consumption categories assessed by the ‘Food Choices and Preferences’ questionnaire | ||||||

| Measured PA | ||||||

| MVPA (min/d) | ||||||

| Consumer | 63·8 | 2·2 | 49·6 | 2·3 | ||

| Occasional | 67·8 | 2·6 | 0·159 | 48·5 | 2·5 | 0·022 |

| Skipper | 66·7 | 2·7 | 52·9 | 2·4 | ||

| Total PA (cpm) | ||||||

| Consumer | 476·5 | 14·8 | 383·1 | 14·2 | ||

| Occasional | 498·6 | 17·6 | 0·296 | 368·4 | 15·6 | 0·040 |

| Skipper | 490·9 | 17·9 | 397·0 | 14·8 | ||

| Sedentary time (min/d) | ||||||

| Consumer | 536·0 | 9·2 | 547·4 | 9·4 | ||

| Occasional | 526·9 | 10·6 | 0·416 | 552·5 | 10·1 | 0·698 |

| Skipper | 527·0 | 10·8 | 548·9 | 9·7 | ||

| Self-reported PA | ||||||

| MVPA (min/d) | ||||||

| Consumer | 114·5 | 9·8 | 88·5 | 9·2 | 0·507 | |

| Occasional | 128·0 | 10·4 | 0·116 | 94·7 | 9·7 | |

| Skipper | 115·9 | 10·7 | 89·9 | 9·4 | ||

| Total PA (min/d) | ||||||

| Consumer | 172·6 | 12·4 | 145·5 | 13·0 | 0·226 | |

| Occasional | 187·7 | 13·2 | 0·182 | 159·0 | 13·7 | |

| Skipper | 181·4 | 13·5 | 155·5 | 13·3 | ||

| Sedentary time (min/d) | ||||||

| Consumer | 67·6 | 5·1 | 85·3 | 7·1 | ||

| Occasional | 59·1 | 5·8 | 0·022 | 88·9 | 7·6 | 0·004 |

| Skipper | 56·5 | 5·8 | 74·0 | 7·3 | ||

PA, physical activity; MVPA, moderate and vigorous physical activity; cpm, counts per minute.

Values are presented as means with their standard errors. Statistical significance is considered when P ≤ 0·005. All analyses were adjusted for centre, age, mother's education, father's education and family affluence.

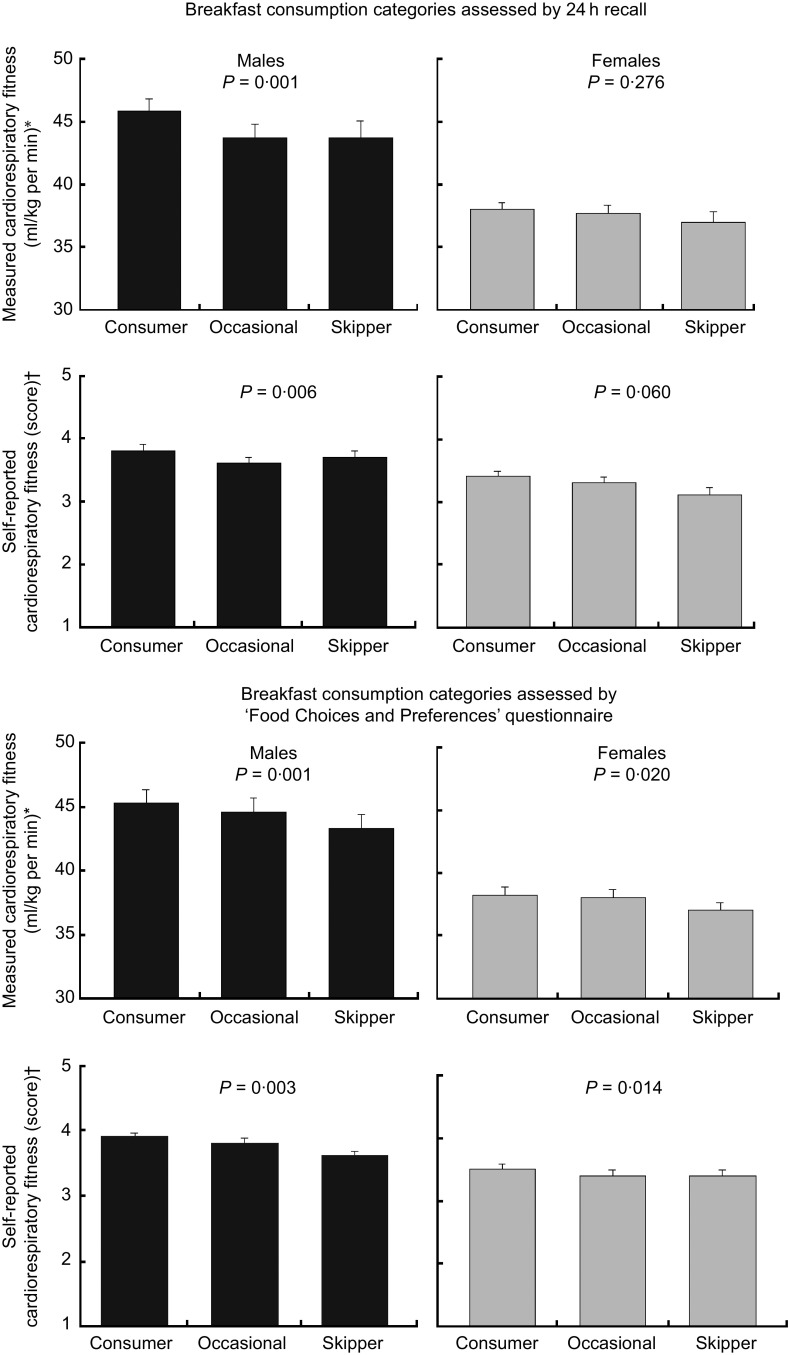

Figure 1 and Table 2 show breakfast consumption categories and mean estimates of measured and self-reported physical fitness components by sex in European adolescents. When breakfast habit was assessed by 24 h recall, we observed significant associations between breakfast consumption and cardiorespiratory fitness in males, but not in females, after adjusting for multiple comparisons (Fig. 1). Male breakfast consumers had on average ∼5 % higher measured cardiorespiratory fitness compared with occasional breakfast consumers and breakfast skippers (P = 0·001). Similar results were observed when cardiorespiratory fitness was self-reported (with a borderline difference of P = 0·006). The results persisted when breakfast consumption was assessed with the ‘Food Choices and Preferences’ questionnaire (Fig. 1). However, both in males and females no differences were observed across breakfast consumption categories (assessed by 24 h recall or the ‘Food Choices and Preferences’ questionnaire) and mean estimates of measured and self-reported muscular fitness and speed/agility after adjusting for multiple comparisons (Table 2).

Fig. 1.

Association of breakfast consumption categories with objectively measured and self-reported cardiorespiratory fitness by sex in European adolescents (n 2148) aged 12·5–17·5 years, HELENA (Healthy Lifestyle in Europe by Nutrition in Adolescence) Cross-Sectional Study, 2006–2007. Values are means with their standard errors represented by vertical bars. The level at which significance is considered is P ≤ 0·005. All analyses were adjusted for centre, age, mother's education, father's education and family affluence. *Estimated by Leger's equation. †Assessed by the International Fitness Scale (IFIS, www.helenastudy.com/IFIS)

Table 2.

Association of breakfast consumption categories with objectively measured and self-reported muscular fitness and speed/agility by sex in European adolescents (n 2148) aged 12·5–17·5 years, HELENA (Healthy Lifestyle in Europe by Nutrition in Adolescence) Cross-Sectional Study, 2006–2007

| Males | Females | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | se | P | Mean | se | P | |

| Breakfast consumption categories assessed by 24 h recall | ||||||

| Measured | ||||||

| Upper-body muscular strength (kg)* | ||||||

| Consumer | 0·5 | 0·02 | 0·6 | 0·01 | ||

| Occasional | 0·5 | 0·03 | 0·775 | 0·6 | 0·02 | 0·131 |

| Skipper | 0·5 | 0·03 | 0·6 | 0·03 | ||

| Lower-body muscular strength (cm)† | ||||||

| Consumer | 187·9 | 2·54 | 147·3 | 3·64 | ||

| Occasional | 183·4 | 3·11 | 0·122 | 144·4 | 3·97 | 0·306 |

| Skipper | 185·8 | 4·09 | 147·0 | 4·53 | ||

| Speed/agility (s)‡ | ||||||

| Consumer | 11·5 | 0·16 | 12·9 | 0·21 | ||

| Occasional | 11·6 | 0·17 | 0·390 | 13·0 | 0·22 | 0·118 |

| Skipper | 11·6 | 0·20 | 12·9 | 0·24 | ||

| Self-reported | ||||||

| Muscular fitness (score)§ | ||||||

| Consumer | 3·7 | 0·04 | 3·3 | 0·07 | ||

| Occasional | 3·7 | 0·07 | 0·817 | 3·2 | 0·09 | 0·007 |

| Skipper | 3·7 | 0·11 | 3·0 | 0·12 | ||

| Speed/agility (score)§ | ||||||

| Consumer | 3·9 | 0·06 | 3·5 | 0·08 | ||

| Occasional | 3·8 | 0·08 | 0·030 | 3·4 | 0·10 | 0·441 |

| Skipper | 3·7 | 0·12 | 3·3 | 0·13 | ||

| Breakfast consumption categories assessed by the ‘Food Choices and Preferences’ questionnaire | ||||||

| Measured | ||||||

| Upper-body muscular strength (kg)* | ||||||

| Consumer | 0·5 | 0·02 | 0·6 | 0·01 | ||

| Occasional | 0·5 | 0·02 | 0·289 | 0·6 | 0·02 | 0·186 |

| Skipper | 0·5 | 0·02 | 0·5 | 0·01 | ||

| Lower-body muscular strength (cm)† | ||||||

| Consumer | 185·1 | 3·77 | 146·1 | 4·18 | ||

| Occasional | 182·3 | 3·94 | 0·257 | 144·7 | 4·29 | |

| Skipper | 182·6 | 3·97 | 142·7 | 4·23 | ||

| Speed/agility (s)‡ | ||||||

| Consumer | 11·5 | 0·16 | 12·7 | 0·22 | ||

| Occasional | 11·6 | 0·17 | 0·053 | 12·8 | 0·23 | 0·062 |

| Skipper | 11·6 | 0·17 | 12·9 | 0·22 | ||

| Self-reported | ||||||

| Muscular fitness (score)§ | ||||||

| Consumer | 3·8 | 0·05 | 3·4 | 0·07 | ||

| Occasional | 3·7 | 0·06 | 0·748 | 3·3 | 0·08 | 0·020 |

| Skipper | 3·8 | 0·06 | 3·2 | 0·07 | ||

| Speed/agility (score)§ | ||||||

| Consumer | 3·9 | 0·06 | 3·5 | 0·08 | ||

| Occasional | 3·9 | 0·07 | 0·091 | 3·5 | 0·09 | 0·362 |

| Skipper | 3·8 | 0·07 | 3·5 | 0·08 | ||

Values are presented as means with their standard errors. Statistical significance is considered when P ≤ 0·005. All analyses were adjusted for centre, age, mother's education, father's education and family affluence.

*Measured by the handgrip strength test (mean handgrip right and left divided by weight).

†Measured by the standing broad jump test.

‡Measured by 4 × 10 m shuttle run.

§Assessed by the International Fitness Scale (IFIS, www.helenastudy.com/IFIS).

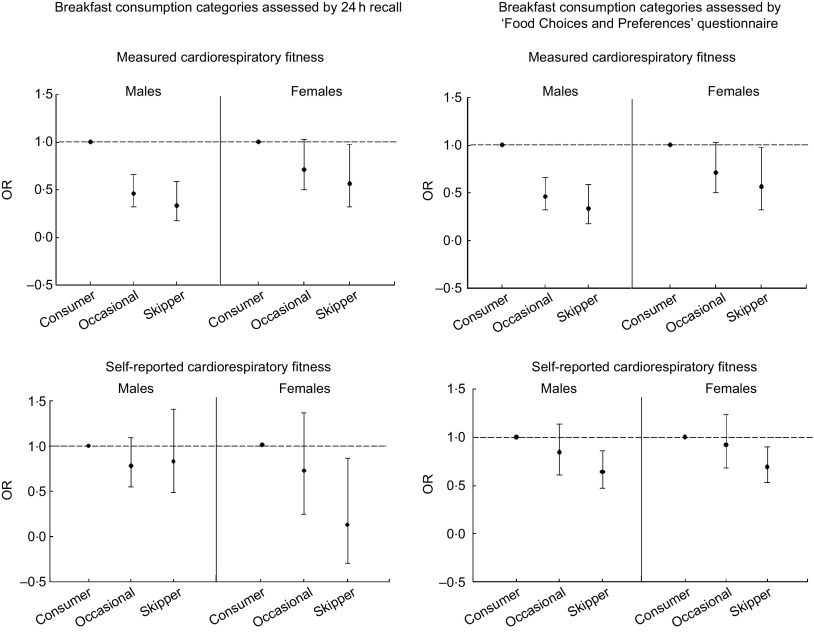

Finally, the odds ratios and 95 % confidence intervals for meeting the physical activity recommendations and having high cardiorespiratory fitness according to breakfast consumption categories were calculated. Breakfast consumption was not associated with meeting the physical activity recommendations, either measured or self-reported, with no difference when using both methods to assess the breakfast patterns (data not shown). However, using the 24 h recall to assess breakfast patterns, male occasional breakfast consumers and breakfast skippers were less likely to have high measured cardiorespiratory fitness compared with breakfast consumers (OR = 0·46; 95 % CI 0·32, 0·66 and OR = 0·33; 95 % CI 0·18, 0·59, respectively; both P < 0·001; Fig. 2). Similarly, female breakfast skippers had a lower odds of having high measured (OR = 0·56; 95 % CI 0·32, 0·98; P = 0·004) and self-reported (OR = 0·52; 95 % CI 0·31, 0·89; P = 0·018) cardiorespiratory fitness than their peers who consumed breakfast. Similar results were observed when breakfast consumption was assessed with the ‘Food Choices and Preferences’ questionnaire (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Odds ratios (with their 95 % confidence intervals represented by vertical bars) for having high cardiorespiratory fitness according to breakfast consumption categories (assessed by 24 h recall and the ‘Food Choices and Preferences’ questionnaire) by sex in European adolescents (n 2148) aged 12·5–17·5 years, HELENA (Healthy Lifestyle in Europe by Nutrition in Adolescence) Cross-Sectional Study, 2006–2007. References are breakfast consumer and having high cardiorespiratory fitness (– – – is the reference high cardiorespiratory fitness). All analysis were adjusted for centre, age, mother's education, father's education and family affluence

Discussion

The present study results suggest that habitual breakfast consumption is not associated with physical activity in male and female European adolescents. These findings were consistent across the different methods used to assess breakfast consumption (24 h recalls on two non-consecutive days or the ‘Food Choices and Preferences’ questionnaire) and physical activity (objectively or self-reported). However, we observed an association between breakfast consumption and measured sedentary time in both males and females; although results were not consistent across methods or gender. On the other hand, breakfast consumption was not related to some physical fitness components such as muscular fitness and speed/agility in males and females. However, habitual breakfast consumption was associated with higher cardiorespiratory fitness in males. In addition, male and female breakfast skippers were less likely to have high cardiorespiratory fitness. These findings were consistent when using different methods to assess either breakfast consumption or cardiorespiratory fitness, and extend previous findings observed in the HELENA Study showing that those adolescents who consumed breakfast regularly had a healthier cardiovascular profile( 12 ).

We did not find any significant association between breakfast consumption and physical activity, which agrees with a previous study developed by Corder et al.( 5 ). They did not find a significant relationship between eating breakfast and objectively measured physical activity( 5 ). In contrast, other authors showed higher levels of self-reported physical activity in those youngsters who were breakfast consumers( 6 , 8 ). The different methodology used to assess physical activity may explain differences among our findings and those previously observed. Our data concur with those that assessed physical activity objectively( 5 ). To the best of our knowledge, the present study is the first to explore the association between breakfast consumption and physical activity assessed by two validated methods, accelerometry and IPAQ-A, in the same report. On the other hand, although some associations between breakfast consumption and sedentary time were detected for males and females, the present study does not provide strong evidence that breakfast consumption was related to sedentary time because the results were not consistent across methods or gender. In addition, we have not found previous studies analysing the association between breakfast habits and sedentary time, which hampers further comparisons.

Of note is that there is no consensus about the best tool to assess breakfast patterns, as well as the more appropriate definition of breakfast consumption categories. Definitions of consumer, occasional consumer or breakfast skipper vary between studies. Most of the studies have used three categories of breakfast pattern such as ‘always’, ‘sometimes’ and ‘never’( 5 , 6 , 12 ), whereas others categorized breakfast consumption into two groups, ‘consumer’ and ‘skipper’( 2 , 8 ). Differences in participants’ age may also contribute to explain these different findings. There is evidence that younger adolescents were more likely to be breakfast consumers( 31 , 32 ). The age range of the study sample of Cohen et al. (8 to 16 years) and Sandercock et al. (10 to 16 years) was lower than for our study sample and they observed a significant relationship between breakfast consumption and physical activity, while we did not find that association( 6 , 8 ). It is known that healthier habits have been observed in children compared with adolescents, and this might be because adolescents begin to make decisions regarding their habits while at younger ages children are more influenced by their parents’ decisions. On the other hand, socio-economic status (both parental educational level and family affluence) is an important factor influencing breakfast consumption( 2 , 3 , 32 ); previous studies that showed a relationship between breakfast consumption and self-reported physical activity did not control for that variable in the analysis( 6 , 8 ).

The association between breakfast consumption and cardiorespiratory fitness has been recently examined( 6 , 12 ), although little information exists as compared with the number of studies exploring the association with physical activity. In the present study, we confirmed that male occasional consumers and breakfast skippers had lower levels of cardiorespiratory fitness than breakfast consumers. We added new data that showed similar results using a validated tool to assess self-reported cardiorespiratory fitness, the IFIS( 13 ). Moreover, we observed that male and female breakfast skippers were less likely to have high cardiorespiratory fitness, both objectively measured and self-reported, than breakfast consumers. Similar results were observed by Sandercock et al.( 6 ), although the authors failed to take into account the socio-economic status (e.g. educational level of parents and family affluence) as a potential confounder, which has been associated with breakfast consumption( 2 , 32 ). In addition, we were the first to study other components of physical fitness, muscular fitness and speed/agility. We observed that breakfast consumption was not related to measured and self-reported muscular fitness or speed/agility in both males and females.

Although higher physical activity is associated with higher cardiorespiratory fitness( 10 ), in our study only cardiorespiratory fitness, not physical activity, was associated with breakfast consumption. In contrast, Sandercock et al. reported that young people aged 10–16 years who regularly ate breakfast had higher levels of both physical activity and cardiorespiratory fitness( 6 ). Although both physical activity and cardiorespiratory fitness were objectively assessed, the measure of physical activity (which is a complex behaviour) is less accurate than the measure of physical fitness. Consequently, the measure of physical fitness may overestimate compared with physical activity( 11 ). Moreover, physical fitness is influenced by other factors such genetics which could also explain differences in physical fitness( 33 ). The amount of energy available early in the morning through breakfast intake may have an impact on adolescents’ physical activity levels in the first part of the day, but not always over the whole day( 5 ). Thus, adolescent breakfast skippers could get energy in the rest of the meals of the day and be more active during the afternoon. Taken together, these hypotheses may explain the lack of association between breakfast consumption and physical activity, whereas we observed an association between breakfast consumption and cardiorespiratory fitness.

Some limitations of the present study need to be mentioned. Lifestyle habits could be different on weekdays and weekends, thus further studies might observe this relationship from assessing physical activity and breakfast consumption during weekdays and weekends separately. In addition, the cross-sectional study design does not allow us to identify causal relationships. On the other hand, a major strength is that the study examines the relationship across breakfast consumption and measured and self-reported physical activity, sedentary time and physical fitness in the same report, and uses different methods to assess breakfast consumption.

Conclusion

Our results suggest that skipping breakfast is not associated with lower physical activity or higher sedentary time in European adolescents. Moreover, breakfast consumption is not associated with some physical fitness components such as muscular fitness or speed/agility. Breakfast consumption is, however, associated with both measured and self-reported cardiorespiratory fitness, which extends previous findings. As cardiorespiratory fitness is considered a health marker in children and adolescents, promoting regular breakfast consumption is of public health interest.

Acknowledgements

Sources of funding: The HELENA Study took place with the financial support of the European Community Sixth RTD Framework Programme (Contract FOOD-CT: 2005-007034). This work was also partially supported by the European Union, in the framework of the Public Health Programme (ALPHA project, ref. 2006120); the Swedish Council for Working Life and Social Research (FAS); the Spanish Ministry of Education (grant nos. AP-2008-03806, RYC-2010-05957, RYC-2011-0901); the Spanish Ministry of Health, Maternal, Child Health and Development Network (grant no. RD08/0072 to L.A.M.); the Universidad Politécnica of Madrid (grant no. CH/018/2008); and the Swedish Heart-Lung Foundation (grant no. 20090635). The contents of this paper reflect only the views of the authors and the rest of the HELENA Study Group members, and the European Community is not liable for any use that may be made of the information contained herein. Conflicts of interest: The authors declare that there are no competing interests. Authors’ contributions: M.C.-G. participated in the analysis and interpretation of the results and drafted the manuscript. J.R.R. was involved in manuscript drafting and coordinated the statistical analysis. F.B.O., I.L. and M.J.C. contributed to interpretation of the results and editing of the manuscript. L.A.M. coordinated the total HELENA Study on an international level. M.G.-G., L.A.M., D.M., F.G., Y.M., W.K., A.K., S.D.H., M.S. and M.J.C. were involved in the design of the HELENA Study and coordinated the project locally. S.G.-M., D.C., L.H. and A.W. performed the data collection locally. All authors have read and have approved the manuscript as submitted. Acknowledgements: The authors gratefully acknowledge all participating children and adolescents, and their parents and teachers, for their collaboration. They also acknowledge all the members involved in field work for their efforts and great enthusiasm.

Appendix.

HELENA Study Group

Coordinator: Luis A. Moreno.

Core Group members: Luis A. Moreno, Fréderic Gottrand, Stefaan De Henauw, Marcela González-Gross, Chantal Gilbert.

Steering Committee: Anthony Kafatos (President), Luis A. Moreno, Christian Libersa, Stefaan De Henauw, Jackie Sánchez, Fréderic Gottrand, Mathilde Kersting, Michael Sjöstrom, Dénes Molnar, Marcela González-Gross, Jean Dallongeville, Chantal Gilbert, Gunnar Hall, Lea Maes, Luca Scalfi.

Project Manager: Pilar Meléndez.

Universidad de Zaragoza (Spain): Luis A. Moreno, Jesús Fleta, José A. Casajús, Gerardo Rodríguez, Concepción Tomás, María I. Mesana, Germán Vicente-Rodríguez, Adoración Villarroya, Carlos M. Gil, Ignacio Ara, Juan Revenga, Carmen Lachen, Juan Fernández Alvira, Gloria Bueno, Aurora Lázaro, Olga Bueno, Juan F. León, Jesús Ma Garagorri, Manuel Bueno, Juan Pablo Rey López, Iris Iglesia, Paula Velasco, Silvia Bel.

Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas (Spain): Ascensión Marcos, Julia Wärnberg, Esther Nova, Sonia Gómez, Esperanza Ligia Díaz, Javier Romeo, Ana Veses, Mari Angeles Puertollano, Belén Zapatera, Tamara Pozo, David Martínez.

Université de Lille 2 (France): Laurent Beghin, Christian Libersa, Frédéric Gottrand, Catalina Iliescu, Juliana Von Berlepsch.

Research Institute of Child Nutrition Dortmund, Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Bonn (Germany): Mathilde Kersting, Wolfgang Sichert-Hellert, Ellen Koeppen.

Pécsi Tudományegyetem (University of Pécs) (Hungary): Dénes Molnar, Eva Erhardt, Katalin Csernus, Katalin Török, Szilvia Bokor, Mrs Angster, Enikö Nagy, Orsolya Kovács, Judit Repásy.

University of Crete School of Medicine (Greece): Anthony Kafatos, Caroline Codrington, María Plada, Angeliki Papadaki, Katerina Sarri, Anna Viskadourou, Christos Hatzis, Michael Kiriakakis, George Tsibinos, Constantine Vardavas, Manolis Sbokos, Eva Protoyeraki, Maria Fasoulaki.

Institut für Ernährungs- und Lebensmittelwissenschaften – Ernährungphysiologie, Rheinische Friedrich Wilhelms Universität (Germany): Peter Stehle, Klaus Pietrzik, Marcela González-Gross, Christina Breidenassel, Andre Spinneker, Jasmin Al-Tahan, Miriam Segoviano, Anke Berchtold, Christine Bierschbach, Erika Blatzheim, Adelheid Schuch, Petra Pickert.

University of Granada (Spain): Manuel J. Castillo, Ángel Gutiérrez, Francisco B. Ortega, Jonatan R Ruiz, Enrique G. Artero, Vanesa España-Romero, David Jiménez-Pavón, Palma Chillón, Magdalena Cuenca-García.

Istituto Nazionalen di Ricerca per gli Alimenti e la Nutrizione (Italy): Davide Arcella, Elena Azzini, Emma Barrison, Noemi Bevilacqua, Pasquale Buonocore, Giovina Catasta, Laura Censi, Donatella Ciarapica, Paola D'Acapito, Marika Ferrari, Myriam Galfo, Cinzia Le Donne, Catherine Leclercq, Giuseppe Maiani, Beatrice Mauro, Lorenza Mistura, Antonella Pasquali, Raffaela Piccinelli, Angela Polito, Raffaella Spada, Stefania Sette, Maria Zaccaria.

University of Napoli ‘Federico II’ Department of Food Science (Italy): Luca Scalfi, Paola Vitaglione, Concetta Montagnese.

Ghent University (Belgium): Ilse De Bourdeaudhuij, Stefaan De Henauw, Tineke De Vriendt, Lea Maes, Christophe Matthys, Carine Vereecken, Mieke de Maeyer, Charlene Ottevaere, Inge Huybrechts.

Medical University of Vienna (Austria): Kurt Widhalm, Katharina Phillipp, Sabine Dietrich, Birgit Kubelka, Marion Boriss-Riedl.

Harokopio University (Greece): Yannis Manios, Eva Grammatikaki, Zoi Bouloubasi, Tina Louisa Cook, Sofia Eleutheriou, Orsalia Consta, George Moschonis, Ioanna Katsaroli, George Kraniou, Stalo Papoutsou, Despoina Keke, Ioanna Petraki, Elena Bellou, Sofia Tanagra, Kostalenia Kallianoti, Dionysia Argyropoulou, Katerina Kondaki, Stamatoula Tsikrika, Christos Karaiskos.

Institut Pasteur de Lille (France): Jean Dallongeville, Aline Meirhaeghe.

Karolinska Institutet (Sweden): Michael Sjöstrom, Patrick Bergman, María Hagströmer, Lena Hallström, Mårten Hallberg, Eric Poortvliet, Julia Wärnberg, Nico Rizzo, Linda Beckman, Anita Hurtig Wennlöf, Emma Patterson, Lydia Kwak, Lars Cernerud, Per Tillgren, Stefaan Sörensen.

Asociación de Investigación de la Industria Agroalimentaria (Spain): Jackie Sánchez-Molero, Elena Picó, Maite Navarro, Blanca Viadel, José Enrique Carreres, Gema Merino, Rosa Sanjuán, María Lorente, María José Sánchez, Sara Castelló.

Campden & Chorleywood Food Research Association (United Kingdom): Chantal Gilbert, Sarah Thomas, Elaine Allchurch, Peter Burguess.

SIK – Institutet foer Livsmedel och Bioteknik (Sweden): Gunnar Hall, Annika Astrom, Anna Sverkén, Agneta Broberg.

Meurice Recherche & Development asbl (Belgium): Annick Masson, Claire Lehoux, Pascal Brabant, Philippe Pate, Laurence Fontaine.

Campden & Chorleywood Food Development Institute (Hungary): Andras Sebok, Tunde Kuti, Adrienn Hegyi.

Productos Aditivos SA (Spain): Cristina Maldonado, Ana Llorente.

Cárnicas Serrano SL (Spain): Emilio García.

Cederroth International AB (Sweden): Holger von Fircks, Marianne Lilja Hallberg, Maria Messerer.

Lantmännen Food R&D (Sweden): Mats Larsson, Helena Fredriksson, Viola Adamsson, Ingmar Börjesson.

European Food Information Council (Belgium): Laura Fernández, Laura Smillie, Josephine Wills.

Universidad Politécnica de Madrid (Spain): Marcela González-Gross, Jara Valtueña, David Jiménez-Pavón, Ulrike Albers, Raquel Pedrero, Agustín Meléndez, Pedro J. Benito, Juan José Gómez Lorente, David Cañada, Alejandro Urzanqui, Juan Carlos Ortiz, Francisco Fuentes, Rosa María Torres, Paloma Navarro.

See Appendix for full list of HELENA Study Group members.

References

- 1. Giovannini M, Verduci E, Scaglioni S et al. (2008) Breakfast: a good habit, not a repetitive custom. J Int Med Res 36, 613–624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Utter J, Scragg R, Mhurchu CN et al. (2007) At-home breakfast consumption among New Zealand children: associations with body mass index and related nutrition behaviors. J Am Diet Assoc 107, 570–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Keski-Rahkonen A, Kaprio J, Rissanen A et al. (2003) Breakfast skipping and health-compromising behaviors in adolescents and adults. Eur J Clin Nutr 57, 842–853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Moreno LA, Rodriguez G, Fleta J et al. (2010) Trends of dietary habits in adolescents. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 50, 106–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Corder K, van Sluijs EM, Steele RM et al. (2011) Breakfast consumption and physical activity in British adolescents. Br J Nutr 105, 316–321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sandercock GR, Voss C & Dye L (2010) Associations between habitual school-day breakfast consumption, body mass index, physical activity and cardiorespiratory fitness in English schoolchildren. Eur J Clin Nutr 64, 1086–1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Aarnio M, Winter T, Kujala U et al. (2002) Associations of health related behaviour, social relationships, and health status with persistent physical activity and inactivity: a study of Finnish adolescent twins. Br J Sports Med 36, 360–364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cohen B, Evers S, Manske S et al. (2003) Smoking, physical activity and breakfast consumption among secondary school students in a southwestern Ontario community. Can J Public Health 94, 41–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Moreno LA, Gonzalez-Gross M, Kersting M et al. (2008) Assessing, understanding and modifying nutritional status, eating habits and physical activity in European adolescents: the HELENA (Healthy Lifestyle in Europe by Nutrition in Adolescence) Study. Public Health Nutr 11, 288–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ruiz JR, Rizzo NS, Hurtig-Wennlof A et al. (2006) Relations of total physical activity and intensity to fitness and fatness in children: the European Youth Heart Study. Am J Clin Nutr 84, 299–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ortega FB, Ruiz JR, Castillo MJ et al. (2008) Physical fitness in childhood and adolescence: a powerful marker of health. Int J Obes (Lond) 32, 1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hallström L, Labayen I, Ruiz JR et al. (2013) Breakfast consumption and CVD risk factors in European adolescents: the HELENA (Healthy Lifestyle in Europe by Nutrition in Adolescence) Study. Public Health Nutr 16, 1296–1305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ortega FB, Ruiz JR, Espana-Romero V et al. (2011) The International Fitness Scale (IFIS): usefulness of self-reported fitness in youth. Int J Epidemiol 40, 701–711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Moreno LA, De Henauw S, Gonzalez-Gross M et al. (2008) Design and implementation of the Healthy Lifestyle in Europe by Nutrition in Adolescence Cross-Sectional Study. Int J Obes (Lond) 32, Suppl. 5, S4–S11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Beghin L, Castera M, Manios Y et al. (2008) Quality assurance of ethical issues and regulatory aspects relating to good clinical practices in the HELENA Cross-Sectional Study. Int J Obes (Lond) 32, Suppl. 5, S12–S18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Vereecken CA, Covents M, Sichert-Hellert W et al. (2008) Development and evaluation of a self-administered computerized 24-h dietary recall method for adolescents in Europe. Int J Obes (Lond) 32, Suppl. 5, S26–S34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Vereecken CA, Covents M, Matthys C et al. (2005) Young adolescents’ nutrition assessment on computer (YANA-C). Eur J Clin Nutr 59, 658–667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gilbert C, Hegyi A, Sanchez M et al. (2008) Qualitative research exploring food choices and preferences of adolescents in Europe. HELENA Food Choices and Preferences (Work Package 11): Deliverable 11.1. http://www.helenastudy.com/packages.php

- 19. Ruiz JR, Ortega FB, Martínez-Gómez D et al. (2011) Objectively measured physical activity and sedentary time in European adolescents: the HELENA study. Am J Epidemiol 174, 173–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Martinez-Gomez D, Ruiz JR, Ortega FB et al. (2011) Author response. Am J Prev Med 41, e2–e3. [Google Scholar]

- 21. World Health Organization (2010) Global Recommendations on Physical Activity for Health. Geneva: WHO. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ottevaere C, Huybrechts I, De Bourdeaudhuij I et al. (2011) Comparison of the IPAQ-A and actigraph in relation to VO2max among European adolescents: the HELENA study. J Sci Med Sport 14, 317–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Haerens L, Deforche B, Maes L et al. (2007) Physical activity and endurance in normal weight versus overweight boys and girls. J Sports Med Phys Fitness 47, 344–350. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Rey-Lopez JP, Vicente-Rodriguez G, Ortega FB et al. (2010) Sedentary patterns and media availability in European adolescents: the HELENA study. Prev Med 51, 50–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Rey-Lopez JP, Ruiz JR, Ortega FB et al. (2012) Reliability and validity of a screen time-based sedentary behaviour questionnaire for adolescents: the HELENA study. Eur J Public Health 22, 373–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ortega FB, Artero EG, Ruiz JR et al. (2011) Physical fitness levels among European adolescents: the HELENA study. Br J Sports Med 45, 20–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Leger LA, Mercier D, Gadoury C et al. (1988) The multistage 20 metre shuttle run test for aerobic fitness. J Sports Sci 6, 93–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. The Cooper Institute (2004) FITNESSGRAM Test Administration Manual, 3rd ed. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Iliescu C, Beghin L, Maes L et al. (2008) Socioeconomic questionnaire and clinical assessment in the HELENA Cross-Sectional Study: methodology. Int J Obes (Lond) 32, Suppl. 5, S19–S25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Boyce W, Torsheim T, Currie C et al. (2006) The family affluence scale as a measure of national wealth: validation of an adolescent self-report measure. Soc Indic Res 78, 473–487. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Raaijmakers LG, Bessems KM, Kremers SP et al. (2010) Breakfast consumption among children and adolescents in the Netherlands. Eur J Public Health 20, 318–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hallström L, Vereecken CA, Labayen I et al. (2012) Breakfast habits among European adolescents and their association with sociodemographic factors: the HELENA (Healthy Lifestyle in Europe by Nutrition in Adolescence) study. Public Health Nutr 15, 1879–1889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bouchard C (1986) Genetics of aerobic power and capacity. In Sport and Human Genetics, pp. 59–89 [RM Malina and C Boucherd, editors]. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics. [Google Scholar]