Abstract

Purpose:

To describe predominantly persistent intraretinal fluid (PP-IRF) and its association with visual acuity (VA) and retinal anatomic findings at long-term follow-up in eyes treated with pro re nata (PRN) ranibizumab or bevacizumab for neovascular age-related macular degeneration.

Design:

Cohort within a randomized clinical trial.

Participants:

Participants in the Comparison of Age-related Macular Degeneration Treatments Trials (CATT) assigned to PRN treatment.

Methods:

The presence of intraretinal fluid (IRF) on OCT scans was assessed at baseline and monthly follow-up visits by Duke OCT Reading Center. Predominantly persistent intraretinal fluid through week 12, year 1, and year 2 was defined as the presence of IRF at the baseline and in ≥ 80% of follow-up visits. Among eyes with baseline IRF, the mean VA scores (letters) and changes from the baseline were compared between eyes with and those without PP-IRF. Adjusted mean VA scores and changes from the baseline were also calculated using the linear regression analysis to account for baseline patient features identified as predictors of VA in previous CATT studies. Furthermore, outcomes were adjusted for concomitant predominantly persistent subretinal fluid.

Main Outcome Measures:

Predominantly persistent intraretinal fluid through week 12, year 1, and year 2; VA score and VA change; and scar development at year 2.

Results:

Among 363 eyes with baseline IRF, 108 (29.8%) had PP-IRF through year 1 and 95 (26.1%) had PP-IRF through year 2. When eyes with PP-IRF through year 1 were compared with those without PP-IRF, the mean 1-year VA score was 62.4 and 68.5, respectively (P = 0.002), and was 65.0 and 67.4, respectively (P = 0.13), after adjustment. Predominantly persistent intraretinal fluid through year 2 was associated with worse adjusted 1-year mean VA scores (64.8 vs. 69.2; P = 0.006) and change (4.3 vs. 8.1; P = 0.01) as well as worse adjusted 2-year mean VA scores (63.0 vs. 68.3; P = 0.004) and changes (2.4 vs. 7.1; P = 0.009). Predominantly persistent intraretinal fluid through year 2 was associated with a higher 2-year risk of scar development (adjusted hazard ratio = 1.49; P = 0.03).

Conclusions:

Approximately one quarter of eyes had PP-IRF through year 2. Predominantly persistent intraretinal fluid through year 1 was associated with worse long-term VA, but the relationship disappeared after adjustment for baseline predictors of VA. Predominantly persistent intraretinal fluid through year 2 was independently associated with worse long-term VA and scar development.

Keywords: Anti-VEGF, Choroidal neovascularization, Intraretinal fluid, Persistent, Visual acuity

Randomized clinical trials have demonstrated that intravitreal injections of anti-VEGF agents improve visual acuity (VA) and control the growth and exudation of neovascular lesions. As such, these treatments have been established as the gold standard for the treatment of neovascular age-related macular degeneration (nAMD).1,2 Intraretinal fluid (IRF), subretinal fluid (SRF), and subretinal pigment epithelium (sub-RPE) fluid are caused by leakage from immature blood vessels into the retinal tissue and indicate ongoing neovascular activity.3 The presence of retinal fluid detected using OCT is commonly considered an indication for additional anti-VEGF treatment in as-needed (pro re nata [PRN]) and treat-and-extend regimens.4

Among the types of retinal fluid, IRF has been most consistently associated with poor VA and morphologic outcomes.5–11 Based on data from the Comparison of Age-related Macular Degeneration Treatments Trials (CATT), we previously reported that IRF was present cross-sectionally at the year 2 visit in 35% to 48% of eyes receiving monthly ranibizumab or bevacizumab and 45% to 60% of eyes receiving PRN treatment and was associated with worse VA scores at year 2.8 In the VEGF Trap-Eye: Investigation of Efficacy and Safety in Wet AMD (VIEW 2) trial, which investigated the treatment of nAMD with aflibercept, the presence of intraretinal cysts (IRCs) at 12 weeks was associated with lower VA scores at all follow-up visits up to 2 years among patients with IRCs at baseline.6 Retrospective analyses of nAMD patient registries have suggested that a high burden of the presence of IRF over months to years—termed as persistent IRF—results in a worse visual prognosis and predisposes patients to atrophy and scar development, but these studies did not include a comparison group in which baseline IRF resolved.12

In this post hoc analysis of eyes with baseline IRF that were randomized to receive ranibizumab or bevacizumab administered PRN in CATT, we evaluated the long-term functional and anatomic consequences of the persistence of IRF by comparing the visual and morphologic outcomes of eyes with predominantly persistent intraretinal fluid (PP-IRF) with those of eyes with nonpersistent IRF.

Methods

The present study was a secondary analysis of eyes enrolled in CATT. Full descriptions of the design and methods of CATT are available in previous publications3,9,13 and at http://www.clinicaltrials.gov (identifier NCT00593450). The CATT study was conducted in accordance with the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki and the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act. The institutional review boards of the clinical centers participating in CATT approved the study protocol, and written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

We used the term macular atrophy (MA) in this study to refer to retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) and choriocapillaris atrophy, described as geographic atrophy in previous CATT reports.9,10 We used the term macular neovascularization (MNV) to refer to neovascularization associated with nAMD, which was previously called choroidal neovascularization in CATT, to account for type 3 neovascular lesions that originate from retinal vessels rather than the choroid.14

Patient Selection and Treatment

The enrollment criteria for CATT included an age of ≥ 50 years; the presence of previously untreated, active MNV secondary to nAMD in the study eye; a VA of 20/25 to 20/320 ETDRS letters; and the absence of MA at the foveal center. Active MNV was characterized by the presence of leakage detected using fluorescein angiography and by the presence of IRF, SRF, or sub-RPE fluid detected using time-domain OCT (TD-OCT). The patients were randomized at enrollment to receive either 0.50 mg of ranibizumab or 1.25 mg of bevacizumab monthly or on a PRN treatment schedule. Patients in the PRN treatment arm were assessed at monthly intervals for the presence of fluid using OCT and other signs of MNV lesion activity to determine whether additional anti-VEGF injections were indicated. Patients in the monthly treatment arm underwent OCT less frequently, precluding a detailed longitudinal analysis of persistent fluid. As a result, this study included only patients assigned to the PRN dosing schedule for the identification and evaluation of the effects of PP-IRF. As part of the PRN dosing schedule, the anti-VEGF study drug was given at any monthly follow-up visit when the treating ophthalmologist detected macular IRF, SRF, or sub-RPE fluid using OCT or detected other signs of active MNV.

OCT Image Evaluation

OCT scans were acquired in patients in the PRN treatment arm at each monthly follow-up visit for 2 years. Time-domain OCT images were obtained at all visits during year 1. Between years 1 and 2, 22.6% of OCT scan images taken were spectral-domain OCT images, whereas all others were TD-OCT images.15

The OCT scans were independently evaluated at Duke Reading Center by 2 certified, masked readers. Grading disagreements between the readers were resolved by a senior reader. The scan images were graded for the presence and location (foveal or nonfoveal) of IRF, SRF, and sub-RPE fluid. The subretinal tissue complex thickness, SRF thickness, and retinal thickness at the foveal center were measured. Other morphologic features graded using OCT included subretinal hyperreflective material, vitreomacular attachment, epiretinal membrane (ERM), and RPE elevation. Moderate interreader reproducibility of the presence of IRF was observed, with 73% agreement and a kappa statistic of 0.48.16 In a comparison of IRF grading between paired TD-OCT and spectral-domain OCT scans, there was also a moderate agreement of 73%, and the kappa statistic was 0.47.15

The presence of scars was assessed using color fundus photography and fluorescein angiography based on criteria described previously in CATT.17 Briefly, fibrotic scars were defined as well-demarcated, elevated mounds of yellowish–white tissue, whereas nonfibrotic scars were defined as discrete, flat, hyperpigmented areas with varying amounts of central depigmentation.

Determination of PP-IRF

Predominantly persistent intraretinal fluid was defined over 12-week, 1-year, and 2-year periods based on the grading of IRF performed using OCT. Eyes without a sufficient number of graded OCT scans over the period of interest or missing OCT scans at week 12 or 52 were excluded from the analysis. For the analysis of PP-IRF through year 1, IRF grading was required at the baseline, week 12, and week 52 visits and in ≥ 75% of visits between weeks 4 and 48. Predominantly persistent intraretinal fluid through year 1 was defined as the presence of IRF at the baseline and in ≥ 80% of graded visits between weeks 4 and 48. Among eyes with baseline foveal IRF, foveal PP-IRF through year 1 was defined as the presence of IRF at the fovea in ≥ 80% of graded visits between weeks 4 and 48. The cohort of patients used for the analysis of PP-IRF through year 1 was used for defining PP-IRF through 12 weeks. Predominantly persistent intraretinal fluid though 12 weeks was defined as the presence of IRF at the baseline and in all visits up to, and including, week 12. For the cohort of patients used to define PP-IRF through year 2, the eyes were additionally required to have undergone IRF grading in ≥ 75% of visits between weeks 56 and 100 as well as IRF grading at week 104. Predominantly persistent intraretinal fluid through year 2 was defined as the presence of IRF at the baseline and in ≥ 80% of graded visits between weeks 4 and 100. For a sensitivity analysis, 2 additional cohorts, in which IRF was present in 100% of graded visits up to years 1 and 2, were defined.

For the analysis of persistent IRF through year 1, 4 eyes had a combination of missed visits and ungradable OCT scans for > 25% of year 1 visits, 2 eyes had ungradable OCT scans at the week 12 visit, and 7 eyes had ungradable OCT scans at the year 1 visit. For the analysis of persistent IRF through year 2, 26 eyes had a combination of missed visits and ungradable OCT scans for > 25% of year 2 visits, and 17 eyes had a missed visit or ungradable OCT scan at the year 2 visit. Lack of baseline IRF was the most common reason for exclusion overall (n = 126).

Statistical Analysis

All eyes included in this analysis were graded as having IRF at the baseline, unless stated otherwise. We estimated the time to resolution of IRF and the subsequent first recurrence of IRF using Kaplan–Meier curves. The mean numbers of injections received over the study period were compared between patients with PP-IRF through years 1 and 2 and patients without PP-IRF through years 1 and 2. The baseline predictors of PP-IRF were determined using univariate and multivariate logistic regression models. The baseline predictors evaluated in the univariate analysis included patient demographic characteristics, diabetes, hypertension, cigarette smoking, the assigned study drug, MA in either the study eye or fellow eye, nAMD features of the study eye detected using fluorescein angiography, OCT features such as the presence and location of fluid, retinal thickness at the foveal center, and other nAMD-associated anatomic findings such as subretinal hyperreflective material (Table S1, available at www.ophthalmologyretina.org). Risk factors for PP-IRF, identified using the univariate analysis, associated with P < 0.10 were included in an initial multivariate model, which went through backward variable selection to reach the final multivariate model by keeping only risk factors associated with P < 0.05 in the final multivariate model. The incidence rates of MA and fibrotic scar development by year 2 were compared between patients with PP-IRF through year 2 and patients without PP-IRF through year 2. Adjusted risk ratios were calculated after accounting for concomitant presence of predominantly persistent SRF, defined based on the same criteria as that for PP-IRF described here.18

We compared the mean VA scores and mean changes in VA from the baseline between eyes with PP-IRF and those with nonpersistent IRF through week 12, year 1, and year 2. For these analyses, additional comparisons of VA outcomes were made after adjustment for the baseline predictors of VA identified in previous CATT reports and for concomitant predominantly persistent SRF.19 We also compared the year 1 and 2 mean VA scores and changes in eyes with IRF present in 100% of graded visits with those in eyes with IRF present in < 100% of visits during years 1 and 2. Because of smaller cohort sizes, the VA outcomes in these analyses were adjusted based on fewer baseline VA predictors (study eye VA, MNV area, and lesion type) to avoid overfitting of the data.

To determine the effect of baseline IRF on VA in the study cohorts, the adjusted mean VA scores at week 12, year 1, and year 2 were compared between eyes of the cohort that had PP-IRF through year 1 and eyes that did not possess baseline IRF but otherwise fulfilled all data availability criteria of the PP-IRF cohort. The cross-sectional relationship between VA and the presence of IRF in the study cohorts was examined by comparing the follow-up VA scores of eyes with the presence of IRF at the time of VA measurement with those of eyes without IRF at the time of VA measurement. The relationship between VA and IRF status change in the 4-week period between adjacent visits was assessed using the IRF status at each visit relative to that at the previous visit as a variable. Generalized estimating equations were used to adjust for correlations based on longitudinal measures of VA.20

All statistical analyses were performed using SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc), and 2-sided P values < 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

Results

IRF Persistence through Years 1 and 2

Out of 363 eyes with baseline IRF that were eligible for the analysis, 116 (32.0%) had PP-IRF through week 12, 108 (29.8%) had PP-IRF through year 1, and 95 (26.1%) had PP-IRF through year 2. Among eyes with PP-IRF through week 12, 82 (70.7%) also had PP-IRF through year 1 and 70 (60.3%) had PP-IRF through year 2. Eighty-seven (80.6%) eyes with PP-IRF through year 1 also had PP-IRF through year 2. Out of 226 eyes with baseline subfoveal IRF that were eligible for the analysis, 12 (5.3%) had foveal PP-IRF through year 1. Eyes with PP-IRF through year 1 received a greater mean (standard deviation) number of injections than eyes without PP-IRF by year 1 (9.2 [2.9] vs. 6.6 [3.1], respectively; P < 0.001). Eyes with PP-IRF through year 2 received a greater mean number of injections than eyes without PP-IRF by year 2 (16.8 [6.1] vs. 12.1 [6.5], respectively; P < 0.001). In eyes with PP-IRF through year 2, the time interval between the last injection and the year 2 visit tended to be shorter (median, 4 weeks; interquartile range, 4–12 weeks) than that in eyes without PP-IRF by year 2 (median, 8 weeks; interquartile range, 4–20 weeks).

Retinal Thickness at the Foveal Center

The mean retinal thickness at the foveal center at year 1 was 180.5 μm in eyes with PP-IRF through year 1 and 153.1 μm in eyes without PP-IRF through year 1 (P = 0.003). Among eyes with PP-IRF through year 1, the retinal thickness at the foveal center was between 120 and 212 μm in 67 (62.0%), < 120 μm in 18 (16.7%), and > 212 μm in 23 (21.3%; Table 1) eyes. The retinal thickness at the foveal center at year 2 was similarly distributed in these eyes. Between week 12 and year 1, the maximum observed retinal thickness at the foveal center for each eye was between 120 and 212 μm in 47 (43.5%), < 120 μm in 3 (2.8%), and > 212 μm in 58 (53.7%) eyes.

Table 1.

Retinal Thicknesses at the Foveal Centers in Eyes with Predominantly Persistent Intraretinal Fluid through Year 1

| Retinal Thickness at Foveal Center (μm) | Eyes with predominantly persistent intraretinal fluid through yr 1 (n = 108)* |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Measured at Yr 1 n (%) | Measured at Yr 2* n (%) | Maximum Retinal Thickness between Wk 12 and Yr 1 n (%) | |

| < 120 | 18 (16.7%) | 26 (26.3%) | 3 (2.8%) |

| 120 to 212 | 67 (62.0%) | 52 (52.5%) | 47 (43.5%) |

| > 212 | 23 (21.3%) | 21 (21.2%) | 58 (53.7%) |

|

| |||

| Eyes without predominantly persistent intraretinal fluid through yr 1 (n = 255) † | |||

|

| |||

| < 120 | 22 (8.6%) | 66 (27.5%) | 11 (4.3%) |

| 120 to 212 | 175 (68.6%) | 146 (60.9%) | 167 (65.5%) |

| > 212 | 58 (22.7%) | 28 (11.6%) | 77 (30.2%) |

9 eyes did not have a retinal thickness measurement at year 2.

15 eyes did not have a retinal thickness measurement at year 2.

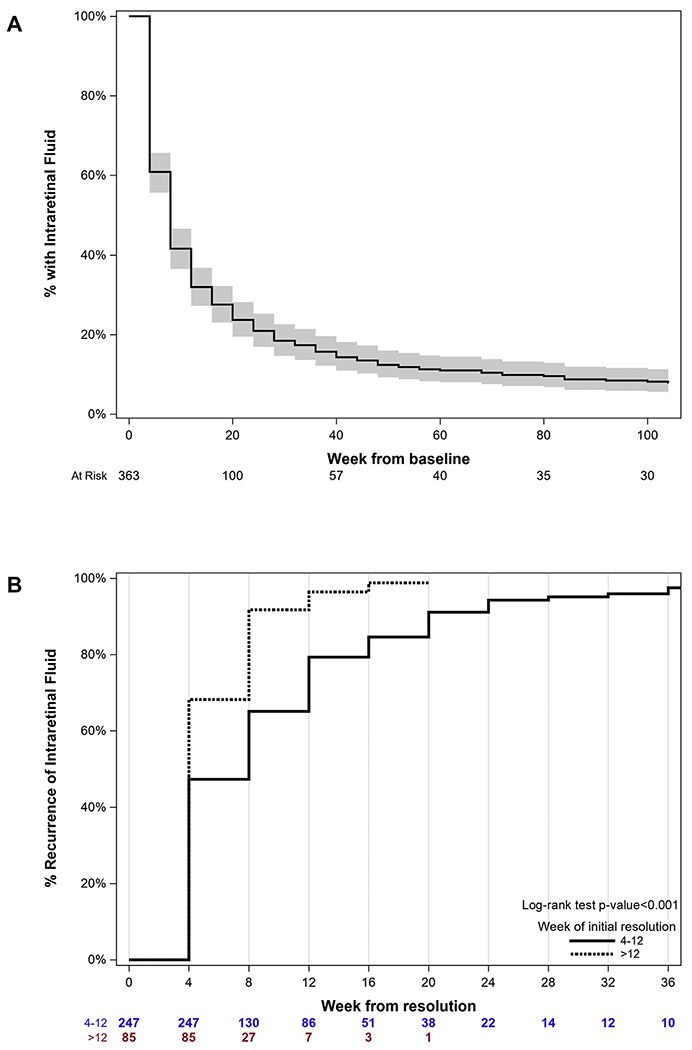

Time to IRF Resolution and Recurrence

The Kaplan–Meier estimates of the time to initial resolution of IRF among all 363 eyes with IRF at the baseline are shown in Figure 1. The median time to initial resolution of IRF was 8 weeks (95% confidence interval [CI], 4–8 weeks). The estimated percentage of eyes with IRF resolution was 88% at year 1 and 92% at year 2. When IRF initially resolved within the first 12 weeks of follow-up, the median time to IRF recurrence was 8 weeks (95% CI, 4–8 weeks). When initial IRF resolution occurred after week 12, the median time to IRF recurrence was 4 weeks (95% CI, 0–4 weeks; log-rank P < 0.001).

Figure 1.

Kaplan–Meier curves for the time to intraretinal fluid (IRF) resolution and recurrence among patients on pro re nata (PRN) treatment. A, Time to IRF resolution among patients with PRN treatment. Shaded regions depict 95% confidence intervals. N values refer to N at the risk of resolution at each time point. B, Time to IRF recurrence after initial resolution among patients with PRN treatment, stratified by IRF resolution occurring before or after week 12. Log-rank P value < 0.001. N values refer to N at the risk of recurrence at each time point.

When stratified by baseline retinal thickness at the foveal center (using a median value of 200 μm as the cutoff), IRF resolved more quickly in eyes with a baseline retinal thickness of 0 to 200 μm than in eyes with a retinal thickness of > 200 μm (log-rank P = 0.04), although the median time to resolution was 8 weeks in both groups (Fig S1, available at www.ophthalmologyretina.org). The median time to the first recurrence of IRF was 8 weeks (95% CI, 4–8 weeks) in eyes with a baseline retinal thickness between 0 and 200 μm and 4 weeks (95% CI, 0–4 weeks) in eyes with a thickness of > 200 μm (log-rank P = 0.01).

Risk Factors for PP-IRF through 1 Year

The baseline predictors of PP-IRF through year 1 determined using the multivariate analysis are shown in Table 2. Predominantly persistent intraretinal fluid was more likely to occur in eyes treated with bevacizumab than in eyes treated with ranibizumab (adjusted odds ratio, 0.4; P < 0.001), eyes with worse baseline VA (adjusted odds ratio, 1.0 with ≥ 68 letters vs. 2.1 with 53–67 letters, 2.4 with 38–52 letters, and 2.9 with < 38 letters; P = 0.01), and eyes with ERM (adjusted odds ratio, 2.2; P = 0.02). All candidate predictors of PP-IRF through year 1 evaluated in the univariate analysis are available in Table S1.

Table 2.

Multivariate Analysis for Baseline Characteristics Associated with Predominantly Persistent Intraretinal Fluid through Year 1

| Baseline Characteristics |

Predominantly Persistent Intraretinal Fluid through Yr 1 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Yes (%) | Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% CI)* | P | ||

| Drug | Bevacizumab | 175 | 68 (38.9%) | Ref. | < 0.001 |

| Ranibizumab | 173 | 36 (20.8%) | 0.4 (0.3–0.7) | ||

| Visual acuity, baseline | ≥ 68 letters, 20/40 or better | 120 | 23 (19.2%) | Ref. | 0.01* |

| 53 to 67 letters, 20/50 to 80 | 134 | 45 (33.6%) | 2.1 (1.1–3.7) | ||

| 38 to 52 letters, 20/100 to 160 | 75 | 28 (37.3%) | 2.4 (1.2–4.7) | ||

| < 38 letters, 20/200 or worse | 19 | 8 (42.1%) | 2.9 (1.0–8.1) | ||

| Epiretinal membrane | No | 297 | 81 (27.3%) | Ref. | 0.02 |

| Yes | 51 | 23 (45.1%) | 2.2 (1.2–4.2) | ||

CI = confidence interval; Ref. = reference.

P value calculated considering category order of baseline visual acuity.

Associations between PP-IRF and Baseline VA

Lower mean baseline VA scores (letters) were observed in eyes with PP-IRF through week 12 (56.8 vs. 61.8; P = 0.001; Table 3), year 1 (56.6 vs. 61.7; P = 0.001), and year 2 (57.5 vs. 62.4; P < 0.001) compared with those observed in eyes with nonpersistent IRF over the same duration.

Table 3.

Baseline Visual Acuity Score (in Letters) by Predominantly Persistent Intraretinal Fluid Status through Week 12, Year 1, and Year 2

| Duration of Fluid | No | Yes | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Persistence | n | Mean (SE) | n | Mean (SE) | P |

| Wk 12 | 247 | 61.8 (0.8) | 116 | 56.8 (1.3) | 0.001 |

| Yr 1 | 255 | 61.7 (0.8) | 108 | 56.6 (1.2) | 0.001 |

| Yr 2 | 219 | 62.4 (0.8) | 95 | 57.5 (1.3) | < 0.001 |

SE = standard error.

Associations between PP-IRF through Week 12, Year 1, and Year 2 and VA Outcomes

Predominantly persistent intraretinal fluid through week 12 was associated with worse week 12 mean VA scores before (60.8 vs. 68.1; P < 0.001; Table 4) and after adjustment (63.8 vs. 66.6; P = 0.02). Predominantly persistent intraretinal fluid through week 12 was marginally associated with less mean VA gain from the baseline at week 12 (4.0 vs. 6.4; P = 0.052), but the relationship weakened with adjustment (4.2 vs. 6.3; P = 0.07). Eyes with PP-IRF through week 12 had similar adjusted mean VA scores at year 1 (65.8 vs. 67.1; P = 0.40) and year 2 (63.7 vs. 67.2; P = 0.06) compared with eyes without PP-IRF through week 12.

Table 4.

Visual Acuity Score (in Letters) by Predominantly Persistent Intraretinal Fluid

| No |

Yes |

Between-Group Difference |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Visual Acuity, Letters | n * | Mean (SE) | n * | Mean (SE) | Mean (95% CI) | P |

| Predominantly persistent intraretinal fluid through wk 12 | ||||||

| At wk 12 | ||||||

| Unadjusted | 247 | 68.1 (1.0) | 116 | 60.8 (1.4) | −7.3 (−10.7 to −4.0) | < 0.001 |

| Adjusted | 238 | 66.6 (0.7) | 109 | 63.8 (1.0) | −2.8 (−5.2 to −0.4) | 0.02† |

| Change at wk 12 | ||||||

| Unadjusted | 247 | 6.4 (0.7) | 116 | 4.0 (1.0) | −2.3 (−4.7 to 0.0) | 0.052 |

| Adjusted | 241 | 6.3 (0.6) | 111 | 4.2 (1.0) | −2.1 (−4.4 to 0.2) | 0.07‡ |

| Predominantly persistent intraretinal fluid through yr 1 | ||||||

| At yr 1 | ||||||

| Unadjusted | 255 | 68.5 (1.1) | 108 | 62.4 (1.7) | −6.1 (−10.0 to −2.2) | 0.002 |

| Adjusted | 244 | 67.4 (0.9) | 103 | 65.0 (1.3) | −2.4 (−5.6 to 0.7) | 0.13† |

| Change at yr 1 | ||||||

| Unadjusted | 255 | 6.9 (0.9) | 108 | 5.8 (1.4) | −1.1 (−4.2 to 2.1) | 0.51 |

| Adjusted | 247 | 7.1 (0.8) | 105 | 5.1 (1.3) | −2.0 (−5.1 to 1.0) | 0.19‡ |

| Predominantly persistent intraretinal fluid through yr 2 | ||||||

| At yr 2 | ||||||

| Unadjusted | 219 | 68.9 (1.2) | 94 | 61.0 (1.8) | −7.9 (−12.1 to −3.6) | < 0.001 |

| Adjusted | 209 | 68.3 (1.0) | 88 | 63.0 (1.5) | −5.3 (−8.9 to −1.7) | 0.004† |

| Change at yr 2 | ||||||

| Unadjusted | 219 | 6.5 (1.1) | 94 | 3.6 (1.6) | −2.9 (−6.7 to 0.9) | 0.13 |

| Adjusted | 211 | 7.1 (1.0) | 91 | 2.4 (1.5) | −4.8 (−8.4 to −1.2) | 0.009‡ |

CI = confidence interval; SE = standard error.

In the adjusted analyses, a small number of eyes were excluded because of missing data for ≥ 1 baseline covariates used in the adjustment.

Visual acuity score was adjusted for baseline predictors of visual acuity, including age, study eye visual acuity, macular neovascularization area, lesion type, study eye macular atrophy, total foveal thickness, retinal pigment epithelium elevation, and predominantly persistent subretinal fluid over the same duration.

Visual acuity change from baseline was adjusted for baseline predictors, including age, study eye visual acuity, macular neovascularization area, retinal angiomatous proliferation, and retinal pigment epithelium elevation, and predominantly persistent subretinal fluid over the same duration.

Predominantly persistent intraretinal fluid through year 1 was associated with worse year 1 mean VA scores (62.4 vs. 68.5; P = 0.002; Table 4), but this was not so after adjustment (65.0 vs. 67.4; P = 0.13). The mean VA gains from the baseline to year 1 were similar between eyes with PP-IRF through year 1 and those with nonpersistent IRF through year 1, both before (5.8 vs. 6.9, respectively; P = 0.51) and after adjustment (5.1 vs. 7.1, respectively; P = 0.19). When only eyes with IRF present in 100% of graded visits through year 1 were considered as having persistent IRF (n = 43), the differences in the adjusted mean year 1 VA scorea (63.1 vs. 67.2; P = 0.08) and adjusted mean VA gains from the baseline at year 1 (3.3 vs. 6.9; P = 0.09) between the groups were somewhat larger, but these difference were not statistically significant (Table S2, available at www.ophthalmologyretina.org).

The mean year 2 VA score was lower in eyes with PP-IRF through year 2 than in eyes without PP-IRF through year 2 before (61.0 vs. 68.9, respectively; P < 0.001; Table 4) and after adjustment (63.0 vs. 68.3, respectively; P = 0.004). The mean VA gains from baseline to year 2 were similar between eyes with PP-IRF and those with nonpersistent IRF through year 2 before adjustment (3.6 vs. 6.5, respectively; P = 0.13) but were significantly lower in eyes with PP-IRF through year 2 after adjustment (2.4 vs. 7.1, respectively; P = 0.009). Predominantly persistent intraretinal fluid through year 2 was also associated with worse adjusted mean year 1 VA scores (64.8 vs. 69.2; P = 0.006) and less mean VA gain from baseline to year 1 (4.3 vs. 8.1; P = 0.01). When only eyes with IRF present in 100% of the graded visits through year 2 were considered as having persistent IRF (n = 23), the 2 groups had similar adjusted mean year 2 VA scores (65.7 vs. 66.8; P = 0.75) and adjusted mean VA changes from the baseline at year 2 (4.5 vs. 5.8; P = 0.69; Table S2).

Associations among PP-IRF through Year 2, MA, and Scars

Among eyes with no baseline MA that were eligible for the analysis of PP-IRF through year 2, 31 (15.5%) eyes with nonpersistent IRF through year 2 and 16 (18.8%) with PP-IRF through year 2 had developed MA by year 2 (adjusted hazard ratio, 1.32; 95% CI, 0.66–2.63; P = 0.44; Table 5). Among eyes with no baseline scar that were eligible for the analysis of PP-IRF through year 2, 93 (43.5%) eyes with nonpersistent IRF and 56 (64.4%) with PP-IRF through year 2 had developed a scar by year 2 (adjusted hazard ratio, 1.49; 95% CI, 1.03–2.14; P = 0.03).

Table 5.

Year 2 Macular Atrophy and Scar Risk by Predominantly Persistent Intraretinal Fluid through Year 2

| Predominantly Persistent Intraretinal Fluid through Yr 2 |

Unadjusted |

Adjusted |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome at Year 2 | No | Yes | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | P | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | P |

| Macular atrophy (%) | 31 (15.5%) | 16 (18.8%) | 1.21 (0.66–2.21) | 0.54 | 1.32 (0.66–2.63) | 0.44* |

| Scar (%) | 93 (43.5%) | 56 (64.4%) | 1.68 (1.20–2.34) | 0.002 | 1.49 (1.03–2.14) | 0.03† |

CI = confidence interval.

Hazard ratio for 2-year risk of macular atrophy adjusted by the baseline features: study eye visual acuity, retinal angiomatous proliferation, blocked fluorescence, fellow eye macular atrophy, subretinal fluid thickness at the foveal center, subretinal tissue complex at the foveal center, vitreomacular attachment, drug group, and regimen group.

Hazard ratio for 2-year risk of scar adjusted by the baseline features: baseline fellow eye visual acuity, macular neovascularization lesion type, lesion-associated hemorrhage, retinal thickness at the foveal center, subretinal fluid thickness at the foveal center, subretinal tissue complex thickness at the foveal center, retinal pigment epithelial elevation, and subretinal hyperreflective material.

Association between IRF Change and Concurrent VA Change between Adjacent 4-Week Visits

Table 6 provides the mean VA changes between adjacent visits 4 weeks apart for each combination of IRF status at the 2 visits in eyes with baseline IRF. The mean VA changes differed significantly among the combinations of IRF status (P < 0.001). An unadjusted mean VA loss of – 0.71 letters was observed when the IRF status changed from absent to present, and an unadjusted mean VA gain of 0.56 letters was observed when the IRF status changed from present to absent. The VA increased by an unadjusted mean of 0.04 letters when IRF was present in 2 consecutive visits and by an unadjusted mean of 0.15 letters when IRF was absent in 2 consecutive visits. Similar mean VA changes for each pattern of IRF status were observed after adjustment.

Table 6.

Visual Acuity Change (in Letters) over 4 Weeks by Change in Intraretinal Fluid Status between Adjacent 4-Week Visits

| Visual acuity change over 4 wks by fluid variables | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Unadjusted

|

Adjusted

*

|

||||

| Intraretinal Fluid Status in Adjacent Visits (Previous Visit/Current Visit) | n | Mean Change (95% CI) | P† | Mean Change (95% CI) | P† | |

| Change in intraretinal fluid status over 4 wks | Present/present | 3808 | 0.04 (0.08) | < 0.001 | 0.03 (0.08) | < 0.001 |

| Not present/present | 1537 | −0.71 (0.17) | −0.66 (0.18) | |||

| Present/not present | 1564 | 0.56 (0.15) | 0.52 (0.16) | |||

| Not present/not present | 2570 | 0.15 (0.07) | 0.19 (0.08) | |||

CI = confidence interval.

Adjusted by baseline predictors of visual acuity, including age, visual acuity, macular neovascularization area, macular neovascularization lesion type, study eye macular atrophy, total foveal thickness, retinal pigment epithelium elevation, drug, and subretinal fluid.

All 4 fluid status variables were considered simultaneously in a model of visual acuity.

Cross-Sectional Association between IRF and VA

In eyes with baseline IRF included in the analysis of PP-IRF through year 1, the presence of IRF at the time of VA measurement was associated with worse mean VA scores at week 12 (63.8 vs. 68.4; P = 0.005; Table 7), year 1 (64.8 vs. 69.7; P = 0.01), and year 2 (62.7 vs. 71.4; P < 0.001). After adjustment for the baseline predictors of VA, the mean VA scores were significantly worse in eyes with IRF than in eyes without IRF at week 12 (64.4 vs. 67.4; P = 0.008) and year 2 (64.0 vs. 69.7; P = 0.001) but not at year 1 (65.9 vs. 68.2; P = 0.12).

Table 7.

Cross-Sectional Association between Visual Acuity Score (in Letters) and the Presence of Intraretinal Fluid at the Time of Visual Acuity Measurement among Patients with Baseline Intraretinal Fluid and Eligible for Year 1 Predominantly Persistent Intraretinal Fluid Analysis

| Intraretinal fluid at the time of visual acuity measurement |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

No

|

Yes

|

Between-Group Difference

|

||||

| Visual Acuity, Letters | n | Mean (SE) | n | Mean (SE) | Mean (95% CI) | P |

| At wk 12 | ||||||

| Unadjusted | 155 | 68.4 (1.2) | 207 | 63.8 (1.1) | −4.6 (−7.8 to −1.4) | 0.005 |

| Adjusted* | 150 | 67.4 (0.8) | 196 | 64.4 (0.7) | −3.0 (−5.3 to −0.8) | 0.008 |

| At yr 1 | ||||||

| Unadjusted | 151 | 69.7 (1.4) | 207 | 64.8 (1.2) | −4.8 (−8.5 to −1.2) | 0.01 |

| Adjusted* | 142 | 68.2 (1.1) | 200 | 65.9 (0.9) | −2.3 (−5.1 to 0.6) | 0.12 |

| At yr 2 (within yr 1 cohort) | ||||||

| Unadjusted | 131 | 71.4 (1.5) | 198 | 62.7 (1.3) | −8.7 (−12.6 to −4.8) | < 0.001 |

| Adjusted* | 126 | 69.7 (1.3) | 187 | 64.0 (1.1) | −5.6 (−9.0 to −2.3) | 0.001 |

CI = confidence interval; SE = standard error.

Adjusted for baseline predictors of visual acuity, including age, study eye visual acuity, macular neovascularization area, lesion type, study eye macular atrophy, total foveal thickness, retinal pigment epithelium elevation, and predominantly persistent subretinal fluid. The baseline predictors of visual acuity change include age, study eye visual acuity, macular neovascularization area, retinal angiomatous proliferation, and retinal pigment epithelium elevation.

Association between the Presence of Baseline IRF and VA over Time

When compared with eyes without baseline IRF, eyes with baseline IRF that were eligible for the analysis of PP-IRF through year 1 had worse mean VA scores at week 12 (65.8 vs. 72.8; P < 0.001), year 1 (66.7 vs. 73.8; P < 0.001), and year 2 (65.9 vs. 73.8; P < 0.001; Table 8). However, the adjusted mean VA scores at week 12 (67.1 vs. 68.7; P = 0.15), year 1 (68.1 vs. 69.6; P = 0.33), and year 2 (66.9 vs. 70.2; P = 0.06) were similar between the 2 groups. The mean VA changes from the baseline were similar between eyes with baseline IRF and those without baseline IRF at week 12 (5.6 vs. 6.1; P = 0.64), year 1 (6.6 vs. 7.2; P = 0.68), and year 2 (5.5 vs. 6.8; P = 0.46). After adjustment, the baseline IRF status remained unassociated with VA change from the baseline at all time points.

Table 8.

Visual Acuity Score (in Letters) by Baseline Intraretinal Fluid among Patients with at Least 75% OCT Visits within Year 1

| Baseline intraretinal fluid |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

No

|

Yes

|

Between-Group Difference

|

||||

| Visual Acuity, Letters | n * | Mean (SE) | n * | Mean (SE) | Mean (95% CI) | P |

| At wk 12 | ||||||

| Unadjusted | 116 | 72.8 (1.4) | 363 | 65.8 (0.8) | −7.0 (−10.1 to −4.0) | < 0.001 |

| Adjusted | 115 | 68.7 (1.0) | 347 | 67.1 (0.6) | −1.7 (−4.0 to 0.6) | 0.15† |

| Change at wk 12 | ||||||

| Unadjusted | 116 | 6.1 (0.9) | 363 | 5.6 (0.5) | −0.5 (−2.7 to 1.6) | 0.64 |

| Adjusted | 115 | 6.9 (0.9) | 347 | 5.4 (0.5) | −1.5 (−3.6 to 0.6) | 0.16‡ |

| At yr 1 | ||||||

| Unadjusted | 116 | 73.8 (1.6) | 363 | 66.7 (0.9) | −7.1 (−10.6 to −3.6) | < 0.001 |

| Adjusted | 115 | 69.6 (1.3) | 347 | 68.1 (0.7) | −1.5 (−4.4 to 1.5) | 0.33† |

| Change at year 1 | ||||||

| Unadjusted | 116 | 7.2 (1.3) | 363 | 6.6 (0.7) | −0.6 (−3.4, 2.2) | 0.68 |

| Adjusted | 115 | 7.9 (1.2) | 347 | 6.3 (0.7) | −1.6 (−4.4 to 1.1) | 0.25‡ |

| At yr 2 | ||||||

| Unadjusted | 108 | 73.8 (1.7) | 344 | 65.9 (0.9) | −7.9 (−11.6 to −4.2) | < 0.001 |

| Adjusted | 107 | 70.2 (1.5) | 328 | 66.9 (0.8) | −3.2 (−6.7 to 0.2) | 0.06† |

| Change at yr 2 | ||||||

| Unadjusted | 108 | 6.8 (1.5) | 344 | 5.5 (0.9) | −1.3 (−4.7 to 2.1) | 0.46 |

| Adjusted | 107 | 8.2 (1.4) | 328 | 5.2 (0.8) | −3.1 (−6.3 to 0.2) | 0.07‡ |

CI = confidence interval; SE = standard error.

In the adjusted analyses, a small number of eyes were excluded because of missing data for ≥ 1 baseline covariates used in the adjustment.

Visual acuity score was adjusted for baseline predictors of visual acuity, including age, study eye visual acuity, macular neovascularization area, lesion type, study eye macular atrophy, total foveal thickness, retinal pigment epithelium elevation, and predominantly persistent subretinal fluid.

The baseline predictors of visual acuity change include age, study eye visual acuity, macular neovascularization area, retinal angiomatous proliferation, retinal pigment epithelium elevation, and predominantly persistent subretinal fluid over the same duration.

Discussion

We evaluated the prevalence of PP-IRF and its association with VA in CATT. Among eyes with baseline IRF, 32% had PP-IRF through week 12. Approximately 70% of eyes with PP-IRF through week 12 also had PP-IRF through year 1, whereas 60% had PP-IRF through year 2. This suggests that eyes with early persistence of IRF through 12 weeks of anti-VEGF treatment have a higher risk of long-term persistent IRF, although some still experience the resolution of IRF between week 12 and year 1 or 2.

Baseline IRF tended to resolve quickly after anti-VEGF therapy initiation and recur shortly thereafter, and IRF recurrence occurred more quickly when initial IRF resolution did not take place within the first 12 weeks. When initial IRF resolution occurred after 12 weeks, 92% recurred within 8 weeks of resolution, whereas in the cohort with initial IRF resolution before 12 weeks, only 65% recurred in the following 8 weeks. It is important to recognize the tendency of IRF to recur after resolution is achieved with anti-VEGF therapy, especially in eyes that exhibit slower initial resolution. Accordingly, for patients who are treated using a PRN or treat-and-extend regimen, if IRF resolution does not occur until after 12 weeks, it may be reasonable for the clinician to consider an earlier follow-up visit, after initial fluid resolution, to prevent an extended period of untreated IRF after fluid recurrence.

Eyes treated with bevacizumab, compared with eyes treated with ranibizumab, had an increased likelihood of PP-IRF through year 1. Ranibizumab has previously been shown in CATT to result in a fluid-free retina more frequently than bevacizumab, although the 1- and 2-year VA outcomes for all CATT patients were similar with the 2 drugs.2,13 In this study, however, the majority of eyes with baseline IRF treated with either PRN bevacizumab or ranibizumab did not exhibit PP-IRF through year 1 (61% and 79%, respectively). The association of worse baseline VA with an increased risk of PP-IRF through year 1 may suggest that eyes with more advanced disease are more likely to resist anti-VEGF therapy. Eyes with ERM were more likely to have persistent IRF through year 1, and the presence of ERM has been associated with an increased number of anti-VEGF injections and decreased treatment intervals in patients with nAMD.21 However, IRCs can occur in eyes with ERM and no evidence of nAMD or other exudative diseases.22 Therefore, some apparently persistent IRF in the setting of ERM may be indicated by hyporeflective spaces formed through a VEGF-independent mechanism, such as mechanical traction exerted by ERM.

Eyes with PP-IRF through year 1 had a significantly lower mean VA score than eyes with nonpersistent IRF through year 1 (62.4 vs. 68.5 letters, respectively). However, when the VA scores were adjusted for other baseline predictors of VA, the mean difference between the groups of eyes with PP-IRF and those of eyes without PP-IRF through year 1 was smaller and no longer significantly associated with lower VA scores at year 1. This finding is important because most studies examining the relationship between morphology and functional outcomes in patients with nAMD have found the presence of IRF to be associated with worse VA.5–9,13,23,24 The lower unadjusted year 1 VA scores observed in eyes with PP-IRF through year 1 showed that these eyes have a poorer functional prognosis than eyes without PP-IRF, as suggested by previous literature. The adjusted analysis demonstrated that the poorer VA observed in eyes with PP-IRF can be largely attributed to baseline patient and disease characteristics that affect VA and are present more or less often in the setting of PP-IRF. When the effects of those covariates were removed in the adjusted analysis, persistent IRF through year 1 was no longer independently associated with worse year 1 VA scores. In a previous study, IRCs that persisted through 12 months of anti-VEGF treatment in a clinical setting were significantly correlated with less VA gain from the baseline at 12 months and showed a borderline association with lower baseline VA.24 In our previous cross-sectional analysis of all eyes without adjustment for the baseline predictors of VA in CATT, the presence of foveal and nonfoveal IRF was associated with worse VA scores at all time points up to year 1.7 When we performed a similar cross-sectional analysis in the cohort of eyes with baseline IRF that were evaluated for PP-IRF through year 1, we also observed a significant association between the presence of IRF at year 1 and worse year 1 VA scores in the unadjusted analysis, but the association diminished after adjustment. Among the baseline predictors of follow-up VA scores, baseline VA was the largest contributor to the difference between the groups in the unadjusted model. This illustrates that when compared with eyes with baseline IRF that was not persistent, those with PP-IRF through year 1 tended to have worse VA at presentation and gained a similar number of letters by year 1, not closing the gap between the groups.

Eyes with PP-IRF through week 12 had significantly lower week 12 VA scores but similar VA changes from the baseline to week 12 compared with eyes with nonpersistent IRF. However, PP-IRF through week 12 was no longer associated with lower VA scores at years 1 and 2 after adjustment for other baseline predictors of VA. In a post hoc analysis of the VIEW1 and VIEW2 trials, the visual outcomes of eyes with IRF or SRF persistence through 3 initial monthly anti-VEGF injections had VA scores at baseline and week 52 similar to eyes without this early persistent fluid.25 The results of both the VIEW analyses and this study suggest that the early persistence of IRF through a 3-month loading phase is not likely to threaten long-term vision in the absence of other pathologies. In this study, eyes with baseline IRF, PP-IRF through week 12, and PP-IRF through year 1 had significantly worse year 1 and year 2 VA scores before adjustment but not after adjustment. This finding indicates that the worse VA outcomes observed in those with baseline IRF and PP-IRF up to year 1 may be partially attributed to other baseline pathologic features in the eye rather than IRF-induced damage to the retina. Similar to PP-IRF through year 1, lower baseline VA was a major contributor to the difference in the VA scores between eyes with PP-IRF and those without PP-IRF through week 12. The underlying cause of the worse baseline VA observed in eyes with PP-IRF through week 12 and year 1 is unclear and may be related to greater MNV lesion maturity or severity, which was not captured by the CATT data, in these eyes.

Persistent IRF through year 2, in contrast, was associated with a lower year 1 and year 2 VA score before and after adjustment. Eyes with PP-IRF through year 2 also tended to gain 2 to 3 fewer letters than eyes with nonpersistent IRF, with the adjusted difference reaching significance at year 1 and borderline significance at year 2. The negative impact of the cross-sectional presence of IRF on year 2 VA scores in the cohort analyzed for the persistence of IRF through year 2 was maintained with adjustment, unlike that for year 1. The association of PP-IRF through year 2 with worse adjusted VA outcomes is consistent with the body of literature demonstrating negative associations between the presence of IRF and VA. The independent association of PP-IRF through year 2 with worse follow-up VA, even after adjustment for baseline VA and other predictors, indicates that the chronic presence of IRF over this duration may result in significant retinal damage unrelated to the status of the eye at the baseline. A post hoc analysis of the pHase III, double-masked, multicenter, randomized, Active treatment-controlled study of the efficacy and safety of 0.5 mg and 2.0 mg Ranibizumab administered monthly or on an as-needed Basis (PRN) in patients with subfoveal neOvasculaR age-related macular degeneration (HARBOR) trial compared the VA outcomes of eyes with baseline IRF, which either resolved (was absent in OCT) or remained residual (present in OCT), at long-term follow-up. Residual IRF at 12 and 24 months was associated with less VA gain at their respective time points after adjusting for baseline VA and treatment group.26 Although its methodology differed in terms of how IRF was assessed and the covariates included in statistical adjustment, this study similarly suggests that unresolved baseline IRF has a detrimental effect on long-term VA. The exception to a zero-tolerance approach to IRF in nAMD may apply to instances of apparent IRF that exhibit the highest degree of “persistence.” Intraretinal cysts can form in the retina via degenerative processes or transudative mechanisms related to impaired fluid transport rather than VEGF-driven leakage from an MNV lesion.27 One might expect eyes with IRF at all graded visits through years 1 and 2 to have even worse VA outcomes than the wider cohort with the presence of IRF in ≥ 80% of visits defined as having PP-IRF through year 2. However, eyes with this sustained persistence of IRF through year 2 had similar year 1 and year 2 VA outcomes compared with eyes without it. This observation could be explained if a large portion of eyes with sustained “IRF persistence” did not have exudative IRF but, instead, had degenerative cystoid spaces that would not fluctuate in response to anti-VEGF treatment. Lacking active neovascularization and, instead, having mostly nonfoveal degenerative cysts (only 12 eyes in CATT had foveal PP-IRF through year 1), these eyes could be expected to have better VA than those with fluctuating, chronic, exudative IRF. A post hoc analysis of the VIEW2 trial used the persistence of IRCs through 3 months of anti-VEGF therapy as a basis to distinguish degenerative IRF from exudative IRF.6 However, this criterion may not be a reliable method to determine whether the observed hyporeflective spaces seen using OCT reflect a VEGF-driven fluid or a degenerative change; we showed that only 71% of eyes with the presence of IRF at all visits up to month 3 went on to have PP-IRF through year 1. However, a complete lack of response of apparent IRF to prolonged anti-VEGF treatment in the absence of other signs of neovascular activity could suggest a nonexudative origin, for which anti-VEGF therapy would be neither effective nor beneficial. Imaging biomarkers that enable differentiation between IRF subtypes would improve the assessment and management of nAMD.

Persistent IRF through year 2 was associated with increased risk of scar development but not MA development at year 2. Given that the formation of a fibrous plaque or disciform scar is the most common end point in the natural history of subfoveal MNV lesions,28 an association might be expected between PP-IRF from treatment-resistant MNV lesions and long-term scar development. A previous CATT report on OCT-based precursors of scarring and MA found that pixels of IRF at baseline were predictive of scar formation at the same pixel by year 2 but not predictive of MA.29 Unlike baseline IRF, which was not independently associated with a greater incidence of scars at 2 years in CATT,17 PP-IRF through year 2 increased the risk of scar development even after adjusting for previously determined independent predictors of scarring. This finding suggests that PP-IRF predisposes eyes to scarring but nonpersistent baseline IRF does not.

A lack of association between PP-IRF and the development of MA may, at first, seem contradictory to post hoc analyses of landmark nAMD trials, including the HARBOR and CATT trials, which have consistently found baseline IRF to increase the risk of MA.30–33 However, all eyes with PP-IRF and eyes in the comparison group with nonpersistent IRF possessed baseline IRF as per the inclusion criteria for this study. In treatment-naive eyes with nAMD, the presence of IRF at baseline may indicate compromised integrity or functioning of RPE, which would normally prevent fluid leakage from the choroid into the retina. As RPE is crucial to support the overall health of the neurosensory retina,34 more diseased RPE at presentation would likely impart increased risk of early MA development, irrespective of the responsiveness of IRF and MNV lesions to anti-VEGF therapy. An eye with PP-IRF may not necessarily be further predisposed to developing MA compared with an eye in which baseline IRF has resolved with treatment. Gianniou et al12 defined the persistence of fluid as the presence of fluid in at least 12 consecutive visits despite monthly anti-VEGF injections and found a 3.34-fold increased risk of atrophy and a 3.30-fold increased risk of fibrotic scars in eyes with persistent IRCs compared with that in eyes with persistent SRF. Although this observed risk of MA associated with persistent IRF is high, the finding cannot be directly compared with those of the present study because of the differences in the comparison groups, especially while considering the potential protective effect of SRF on MA development.32,33

This study has several limitations. The number of eyes with foveal PP-IRF was small, and thus, the analysis of its impact on VA outcomes had low statistical power. Although we provided evidence that IRF persistence over a sufficient duration at any location may result in worse long-term VA outcomes, extrapolating these findings to eyes with chronic foveal IRF may underestimate the risk of a poor functional prognosis. Time-domain OCT scans, which have inferior resolution compared with spectral-domain OCT scans, were used to determine the fluid status at all year 1 visits and most year 2 visits. As a result, small collections of IRF may have been missed on the TD-OCT scans.

In summary, we defined PP-IRF as the presence of IRF detected using OCT at the baseline and in ≥ 80% of visits under treatment with PRN anti-VEGF injections in the CATT study. After adjusting for the baseline predictors of VA and predominantly persistent SRF, PP-IRF through week 12 and year 1 was not independently associated with worse long-term VA scores or VA changes from the baseline. Predominantly persistent intraretinal fluid through year 2 was independently associated with worse long-term VA outcomes. Predominantly persistent intraretinal fluid through year 2 was associated with an increased risk of scars but was not associated with an increased risk of MA at year 2.

Supplementary Material

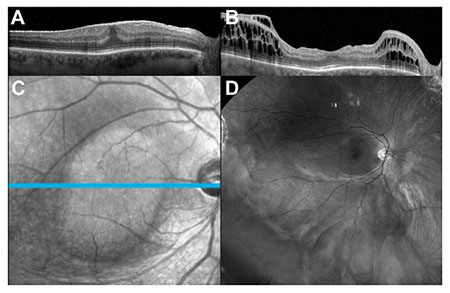

Pictures & Perspectives.

Post-Retinal Detachment Repair Diffuse Tractional Retinoschisis Sparing Region of Internal Limiting Membrane Peel

A visually significant macular epiretinal membrane was observed 2 weeks after pars plana vitrectomy for a rhegmatogenous retinal detachment (visual acuity of 20/60) (Fig A). The patient underwent repeat pars plana vitrectomy with epiretinal and internal limiting membrane peel. The retina remained attached despite the postoperative development of diffuse preretinal membranes sparing only the area of internal limiting membrane peel shown on OCT (Fig B), en face (Fig C), and widefield red-free fundus photograph (Fig D) at month 6. Widespread tractional retinoschisis was noted on OCT at postoperative month 1 and had stabilized by month 4. No further intervention has been performed given the patient’s good macular function and vision of 20/20. (Magnified version of Fig A-D is available online at www.ophthalmologyretina.org).

Greg Budoff, MD

Steven D. Schwartz, MD

Jean-Pierre Hubschman, MD

Retina Division, Stein Eye Institute, University of California Los Angeles, Los Angeles, California

Acknowledgments

Supported by R21EY02368 from National Eye Institute.

Supported by cooperative agreements U10 EY017823, U10 EY017825, U10 EY017826, U10 EY017828 and R21EY023689 from the National Eye Institute, National Institutes of Health, and Department of Health and Human Services. ClinicalTrials.gov number: NCT00593450. The funding organization had no role in the design or conduct of this research.

Disclosure(s):

All authors have completed and submitted the ICMJE disclosures form.

The authors have made the following disclosures:

P.Y.: Grant – National Institutes of Health.

E.D.: Consultant – Novartis International AG.

M.G.M.: Data and safety monitoring committee – Genentech/Roche, Annexon; Grant support – National Eye Institute, National Institutes of Health; Payment – Ohio State University, Retina Society; Payment for travel – Macula Society, Retina Society, Heed Foundation; Board of trustees – ARVO; Honorarium – National Eye Institute.

G.J.J.: Consultancy relationship – Heidelberg Engineering, Alcon/Novartis, Genentech/Roche, Neurotech; Data and safety monitoring committee – Synergy Research Inc.

G.-S.Y.: Consultant – Chengdu Kanghog Biotech Co. Ltd, Ziemer Ophthalmic Systems AG, Synergy Research.

D.F.M.: Consultant – Heidelberg Engineering, Alcon/Novartis, Genentech/Roche. Neurotech.

Abbreviations and Acronyms:

- CATT

Comparison of Age-related Macular Degeneration Treatments Trials

- ERM

epiretinal membrane

- IRC

intraretinal cyst

- IRF

intraretinal fluid

- MA

macular atrophy

- MNV

macular neovascularization

- nAMD

neovascular age-related macular degeneration

- PP-IRF

predominantly persistent intraretinal fluid

- PRN

pro re nata

- RPE

retinal pigment epithelium

- SRF

subretinal fluid

- sub-RPE

subretinal pigment epithelium

- TD-OCT

time-domain OCT

- VA

visual acuity

- VIEW

VEGF Trap-Eye: Investigation of Efficacy and Safety in Wet AMD

Comparison of Age-related Macular Degeneration Treatments Trials (CATT)Research Group: VitreoRetinal Surgery, PA (Edina, MN): David F. Williams, MD (PI); Sara Beardsley, COA (VA/R); Steven Bennett, MD (O); Herbert Cantrill, MD (O); Carmen Chan-Tram, COA (VA/R); Holly Cheshier, CRA, COT, OCTC (OP); John Davies, MD (O); Sundeep Dev, MD (O); Julianne Enloe, CCRP, COA (CC); Gennaro Follano (OP/OCT); Peggy Gilbert, COA (VA/R); Jill Johnson, MD (O); Tori Jones, COA (OCT); Lisa Mayleben, COMT (CC/VA/R/OCT); Robert Mittra, MD (O); Martha Moos, COMT, OSA (VA/R); Ryan Neist, COMT (VA/R); Neal Oestreich, COT (CC); Polly Quiram, MD (O); Robert Ramsay, MD (O); Edwin Ryan, MD (O); Stephanie Schindeldecker, OA (VA/R); Trenise Steele, COA (VA); Jessica Tonsfeldt, AO (OP); Shelly Valardi, COT (VA/R). Texas Retina Associates (Dallas, TX): Gary Edd Fish, MD (PI); Hank A. Aguado, CRA (OP/OCT); Sally Arceneaux (CC/VA/R); Jean Arnwine (CC); Kim Bell, COA (VA/R); Tina Bell (CC/OCT); Bob Boleman (OP); Patricia Bradley, COT (CC); David Callanan, MD (O); Lori Coors, MD (O); Jodi Creighton, COA (VA/R); Kimberly Cummings (OP/OCT); Christopher Dock (OCT); Karen Duignan, COT (VA/R); Dwain Fuller, MD (O); Keith Gray (OP/OCT); Betsy Hendrix, COT, ROUB (OCT); Nicholas Hesse (OCT); Diana Jaramillo, COA (OCT); Bradley Jost, MD (O); Sandy Lash (VA/R); Laura Lonsdale, CCRP (DE); Michael Mackens (OP/OCT); Karin Mutz, COA (CC); Michael Potts (VA/R); Brenda Sanchez (VA/R); William Snyder, MD (O); Wayne Solley, MD (O); Carrie Tarter (VA/R); Robert Wang, MD (O); Patrick Williams, MD (O). Southeastern Retina Associates (Knoxville, TN): Stephen L. Perkins, MD (PI); Nicholas Anderson, MD (O); Ann Arnold, COT (VA/R); Paul Blais (OP/OCT); Joseph Googe, MD (O); Tina T. Higdon, (CC); Cecile Hunt (VA/R); Mary Johnson, COA (VA/R); James Miller, MD (O); Misty Moore (VA/R); Charity K. Morris, RN (CC); Christopher Morris (OCT); Sarah Oelrich, COT (OP/OCT); Kristina Oliver, COA (VA/R); Vicky Seitz, COT (VA/R); Jerry Whetstone (OP/OCT). Retina Vitreous Consultants (Pittsburgh, PA): Bernard H. Doft (PI); Jay Bedel, RN, (CC); Robert Bergren, MD (O); Ann Borthwick (VA/R); Paul Conrad, MD, PHD (O); Christina Fulwylie (VA/R); Willia Ingram (DE); Shawnique Latham (VA/R); Gina Lester (VA/R); Judy Liu, MD (O); Louis Lobes, MD (O); Nicole M. Lucko, (CC); Lori Merlotti, MS, CCRC (CC); Karl Olsen, MD (O); Danielle Puskas, COA (VA/R); Pamela Rath, MD (O); Lynn Schueckler (OCT); Christina Schultz (CC/VA/R); Heather Shultz (OP/OCT); David Steinberg, CRA (OP/OCT); Avni Vyas, MD (O); Kim Whale (VA/R); Kimberly Yeckel, COA, COT (VA/R). Ingalls Memorial Hospital/Illinois Retina Associates (Harvey, IL): David H. Orth, MD (PI); Linda S. Arredondo, RN (CC/VA); Susan Brown (VA/R); Barbara J. Ciscato (CC/VA); Joseph M. Civantos, MD (O); Celeste Figliulo (VA/R); Sohail Hasan, MD (O); Belinda Kosinski, COA (VA/R); Dan Muir (OP/OCT); Kiersten Nelson (OP/OCT); Kirk Packo, MD (O); John S. Pollack, MD (O); Kourous Rezaei, MD (O); Gina Shelton (VA); Shannya Townsend-Patrick (OP/OCT); Marian Walsh, CRA (OP/OCT). West Coast Retina Medical Group, Inc (San Francisco, CA): H. Richard McDonald, MD (PI); Nina Ansari (VA/R/OCT); Amanda Bye, (OP/OCT); Arthur D. Fu, MD (O); Sean Grout (OP/OCT); Chad Indermill (OCT); Robert N. Johnson, MD (O); J. Michael Jumper, MD (O); Silvia Linares (VA/R); Brandon J. Lujan, MD (O); Ames Munden (OP/OCT); Rosa Rodriguez (CC); Jennifer M. Rose (CC); Brandi Teske, COA (VA/R); Yesmin Urias (OCT); Stephen Young (OP/OCT). Retina Northwest, P.C. (Portland, OR): Richard F. Dreyer, MD (PI); Howard Daniel (OP/OCT); Michele Connaughton, CRA (OP/OCT); Irvin Handelman, MD (O); Stephen Hobbs (VA/R/OCT); Christine Hoerner (OP/OCT); Dawn Hudson (VA/R/OCT); Marcia Kopfer, COT (CC/VA/R/OCT); Michael Lee, MD (O); Craig Lemley, MD (O); Joe Logan, COA (OP/OCT); Colin Ma, MD (O); Christophe Mallet (VA/R); Amanda Milliron (VA/R); Mark Peters, MD (O); Harry Wohlsein, COA (OP). Retinal Consultants Medical Group, Inc (Sacramento, CA): Joel A. Pearlman, MD, PHD (PI); Margo Andrews (OP); Melissa Bartlett (OCT); Nanette Carlson (CC/OCT); Emily Cox (VA/R); Robert Equi, MD (O); Marta Gonzalez (VA/R); Sophia Griffin (OP/OCT); Fran Hogue (VA/R); Lance Kennedy (OP/OCT); Lana Kryuchkov (OCT); Carmen Lopez (VA/R); Danny Lopez (OP/OCT); Bertha Luevano (VA/R); Erin McKenna, (CC); Arun Patel, MD (O); Brian Reed, MD (O); Nyla Secor (CC/OCT); Iris R. Sison (CC); Tony Tsai, MD (O); Nina Varghis, (CC); Brooke Waller (OCT); Robert Wendel, MD (O); Reina Yebra (OCT). Retina Vitreous Center, PA (New Brunswick, NJ): Daniel B. Roth, MD (PI); Jane Deinzer, RN (VA/R); Howard Fine, MD MHSC (O); Flory Green (VA/R); Stuart Green, MD (O); Bruce Keyser, MD (O); Steven Leff, MD (O); Amy Leviton (VA/R); Amy Martir (OCT); Kristin Mosenthine (VA/R/OCT); Starr Muscle, RN (CC); Linda Okoren (VA/R); Sandy Parker (VA/R); Jonathan Prenner, MD (O); Nancy Price (CC); Deana Rogers (OP/OCT); Linda Rosas (OP/OCT); Alex Schlosser (OP/OCT); Loretta Studenko (DE); Thea Tantum (CC); Harold Wheatley, MD (O). Vision Research Foundation/Associated Retinal Consultants, P.C. (Royal Oak, MI): Michael T. Trese, MD (PI); Thomas Aaberg, MD (O); Denis Bezaire, CRA (OP/OCT); Craig Bridges, CRA (OP/OCT); Doug Bryant, CRA (OP/OCT); Antonio Capone, MD (O); Michelle Coleman, RN (CC); Christina Consolo, CRA, COT (OP/OCT); Cindy Cook, RN (CC); Candice DuLong (VA/R); Bruce Garretson, MD (O); Tracy Grooten (VA/R); Julie Hammersley, RN (CC); Tarek Hassan, MD (O); Heather Jessick (OP/OCT); Nanette Jones (VA/R/OP/OCT); Crystal Kinsman (VA/R); Jennifer Krumlauf (VA/R); Sandy Lewis, COT (VA/R/OP/OCT); Heather Locke (VA/R); Alan Margherio, MD (O); Debra Markus, COT (CC/VA/R/OP/OCT); Tanya Marsh, COA (OP/OCT); Serena Neal (CC); Amy Noffke, MD (O); Kean Oh, MD (O); Clarence Pence (OP/OCT); Lisa Preston (VA/R); Paul Raphaelian, MD (O); Virginia R. Regan, RN, CCRP (VA/R); Peter Roberts (OP/OCT); Alan Ruby, MD (O); Ramin Sarrafizadeh, MD, PHD (O); Marissa Scherf (OP/OCT); Sarita Scott (VA/R); Scott Sneed, MD (O); Lisa Staples (CC); Brad Terry (VA/R/OP/OCT); Matthew T. Trese (OCT); Joan Videtich, RN (VA/R); George Williams, MD (O); Mary Zajechowski, COT, CCRC (CC/VA/R). Barnes Retina Institute (St. Louis, MO): Daniel P. Joseph, MD (PI); Kevin Blinder, MD (O); Lynda Boyd, COT (VA/R); Sarah Buckley (OP/OCT); Meaghan Crow (VA/R); Amanda Dinatale, (OCT); Nicholas Engelbrecht, MD (O); Bridget Forke (OP/OCT); Dana Gabel (OP/OCT); Gilbert Grand, MD (O); Jennifer Grillion-Cerone (VA/R); Nancy Holekamp, MD (O); Charlotte Kelly, COA (VA/R); Ginny Nobel, COT (CC); Kelly Pepple (VA/R); Matt Raeber, (OP/OCT); P. Kumar Rao, MD (O); Tammy Ressel, COT (VA/R); Steven Schremp (OCT); Merrilee Sgorlon (VA/R); Shantia Shears, MA (CC); Matthew Thomas, MD (O); Cathy Timma (VA/R); Annette Vaughn,(OP/OCT); Carolyn Walters, COT (CC/VA/R); Rhonda Weeks, CRC (CC/VA/R); Jarrod Wehmeier (OP/OCT); Tim Wright (OCT). The Retina Group of Washington (Chevy Chase, MD): Daniel M. Berinstein, MD (PI); Aida Ayyad (VA/R); Mohammed K. Barazi, MD (O); Erica Bickhart (VA/R); Lisa Byank, MA (CC); Alysia Cronise, COA (VA/R); Vanessa Denny (VA/R); Courtney Dunn (VA/R); Michael Flory (OP/OCT); Robert Frantz (OP/OCT); Richard A. Garfinkel, MD (O); William Gilbert, MD (O); Michael M. Lai, MD, PHD (O); Alexander Melamud, MD (O); Janine Newgen (VA/R); Shamekia Newton (CC); Debbie Oliver (CC); Michael Osman, MD (O); Reginald Sanders, MD (O); Manfred von Fricken, MD (O). Retinal Consultants of Arizona (Phoenix, AZ): Pravin Dugel, MD (PI); Sandra Arenas (CC); Gabe Balea (OCT); Dayna Bartoli (OP/OCT); John Bucci (OP/OCT); Jennifer A. Cornelius (CC); Scheleen Dickens, (CC); Don Doherty (OP/OCT); Heather Dunlap, COA (VA/R); David Goldenberg, MD (O); Karim Jamal, MD (O); Norma Jimenez (OP/OCT); Nicole Kavanagh (VA/R); Derek Kunimoto, MD (O); John Martin (OP/OCT); Jessica Miner, RN (VA/R); Sarah Mobley, CCRC (CC/VA/R); Donald Park, MD (O); Edward Quinlan, MD (O); Jack Sipperley, MD (O); Carol Slagle (R); Danielle Smith (OP/OCT); Rohana Yager, COA (OCT). Casey Eye Institute (Portland, OR): Christina J. Flaxel, MD (PI); Steven Bailey, MD (O); Peter Francis, MD, PHD (O); Chris Howell, (OCT); Thomas Hwang, MD (O); Shirley Ira, COT (VA/R); Michael Klein, MD (O); Andreas Lauer, MD (O); Teresa Liesegang, COT (CC/VA/R); Ann Lundquist, (CC/VA/R); Sarah Nolte (DE); Susan K. Nolte (VA/R); Scott Pickell (OP/OCT); Susan Pope, COT (VA/R); Joseph Rossi (OP/OCT); Mitchell Schain (VA/R); Peter Steinkamp, MS (OP/OCT); Maureen D. Toomey (CC/VA/R); Debora Vahrenwald, COT (VA/R); Kelly West (OP/OCT). Emory Eye Center (Atlanta, GA): Baker Hubbard, MD (PI); Stacey Andelman, MMSC, COMT (CC/VA/R); Chris Bergstrom, MD (O); Judy Brower, COMT (CC/VA/R); Blaine Cribbs, MD (O); Linda Curtis (VA/R); Jannah Dobbs (OP/OCT); Lindreth DuBois, MED, MMSC, CO, COMT (CC/VA/R); Jessica Gaultney (OCT); Deborah Gibbs, COMT, CCRC (VA/R); Debora Jordan, CRA (OP/OCT); Donna Leef, MMSC, COMT (VA/R); Daniel F. Martin, MD (O); Robert Myles, CRA (OP); Timothy Olsen, MD (O); Bryan Schwent, MD (O); Sunil Srivastava, MD (O); Rhonda Waldron, MMSC, COMT, CRA, RDMS (OCT). Charlotte Eye, Ear, Nose & Throat Associates/Southeast Clinical Research (Charlotte, NC): Andrew N. Antoszyk, MD (PI); Uma Balasubramaniam, COA (OCT); Danielle Brooks, CCRP (VA/R); Justin Brown, MD (O); David Browning, MD, PHD (O); Loraine Clark, COA (OP/OCT); Sarah Ennis, CCRC (VA/R); Jennifer V. Helms, CCRC,(CC); Jenna Herby, CCRC (CC); Angie Karow, CCRP (VA/R); Pearl Leotaud, CRA (OP/OCT); Caterina Massimino (OCT); Donna McClain, COA (OP/OCT); Michael McOwen, CRA (OP/OCT); Jennifer Mindel, CRA, COA (OP/OCT); Candace Pereira, CRC (CC); Rachel Pierce, COA (VA/R); Michele Powers (OP/OCT); Angela Price, MPH, CCRC (CC); Jason Rohrer (CC); Jason Sanders, MD (O). California Retina Consultants (Santa Barbara, CA): Robert L. Avery, MD (PI); Kelly Avery (VA/R); Jessica Basefsky (CC/OCT); Liz Beckner (OP); Alessandro Castellarin, MD (O); Stephen Couvillion, MD (O); Jack Giust (CC/OCT); Matthew Giust (OP); Maan Nasir, MD (O); Dante Pieramici, MD (O); Melvin Rabena (VA/R); Sarah Risard (VA/R/OCT/DE); Robert See, MD (O); Jerry Smith (VA/R). Mayo Clinic (Rochester, MN): Sophie J. Bakri, MD (PI); Nakhleh Abu-Yaghi, MD (O); Andrew Barkmeier, MD (O); Karin Berg, COA (VA); Jean Burrington, COA (VA/R); Albert Edwards, MD (O); Shannon Goddard, COA (OP/OCT); Shannon Howard (VA/R); Raymond Iezzi, MD (O); Denise Lewison, COA (OP/OCT); Thomas Link, CRA (OP/OCT); Colin A. McCannel, MD (O); Joan Overend (VA/R); John Pach, MD (O); Margaret Ruszczyk, CCRP (CC); Ryan Shultz, MD (O); Cindy Stephan, COT (VA/R); Diane Vogen (CC). Dean A. McGee Eye Institute (Oklahoma City, OK): Reagan H. Bradford Jr, MD (PI); Vanessa Bergman, COA, CCRC (CC); Russ Burris (OP/OCT); Amanda Butt, CRA (OP/OCT); Beth Daniels, COA (CC); Connie Dwiggins, CCRC (CC); Stephen Fransen, MD (O); Tiffany Guerrero (CC/DE); Darin Haivala, MD (O); Amy Harris (CC); Sonny Icks (CC/DE); Ronald Kingsley, MD (O); Rob Richmond (OP/OCT); Brittany Ross (VA/R); Kammerin White, CCRC (VA/R); Misty Youngberg, COA, CCRC (VA/R). Ophthalmic Consultants of Boston (Boston, MA): Trexler M. Topping, MD (PI); Steve Bennett (OCT); Sandy Chong (VA/R); Tina Cleary, MD (O); Emily Corey (VA/R); Dennis Donovan (OP/OCT); Albert Frederick, MD (O); Lesley Freese (CC/VA/R); Margaret Graham (OP/OCT); Natalya Gud, COA (VA/R); Taneika Howard (VA/R); Mike Jones (OP/OCT); Michael Morley, MD (O); Katie Moses (VA/R); Jen Stone (VA/R); Robin Ty, COA (VA/R); Torsten Wiegand, PHD, MD (O); Lindsey Williams (CC); Beth Winder (CC). Tennessee Retina, P.C. (Nashville, TN): Carl C. Awh, MD (PI); Everton Arrindell, MD (O); Dena Beck (OCT); Brandon Busbee, MD (O); Amy Dilback (OP/OCT); Sara Downs (VA/R); Allison Guidry, COA (VA/R); Gary Gutow, MD (O); Jackey Hardin (VA/R); Sarah Hines, COA (CC); Emily Hutchins (VA/R); Kim LaCivita, MA (OP/OCT); Ashley Lester (OCT); Larry Malott (OP/OCT); MaryAnn McCain, RN, CNOR (CC); Jayme Miracle (VA/R); Kenneth Moffat, MD (O); Lacy Palazzotta (VA/R); Kelly Robinson, COA (VA/R); Peter Sonkin, MD (O); Alecia Travis (OP/OCT); RoyTrent Wallace, MD (O); Kelly J. Winters, COA (CC); Julia Wray (OP/OCT). Retina Associates Southwest, P.C. (Tucson, AZ): April E. Harris, MD (PI); Mari Bunnell (OCT); Katrina Crooks (VA/R); Rebecca Fitzgerald, CCRC (CC); Cameron Javid, MD (O); Corin Kew (VA/R); Erica Kill, VAE (VA/R); Patricia Kline (VA/R); Janet Kreienkamp (VA/R); RoyAnn Moore, OMA (CC/OCT); Egbert Saavedra, MD (O); LuAnne Taylor, CSC (CC/OCT); Mark Walsh, MD (O); Larry Wilson (OP). Midwest Eye Institute (Indianapolis, IN): Thomas A. Ciulla, MD (PI); Ellen Coyle, COMT (VA/R); Tonya Harrington, COA (VA/R); Charlotte Harris, COA (VA); Raj Maturi, MD (O); Stephanie Morrow, COA (OP); Jennifer Savage, COA (VA); Bethany Sink, COA (VA/R); Tom Steele, CRA (OP); Neelam Thukral, CCRC (CC/OCT); Janet Wilburn, COA (CC). National Ophthalmic Research Institute (Fort Myers, FL): Joseph P. Walker, MD (PI); Jennifer Banks (VA/R); Debbie Ciampaglia (OP/OCT); Danielle Dyshanowitz (VA/R); Jennifer Frederick, CRC (CC); A. Tom Ghuman, MD (O); Richard Grodin, MD (O); Cheryl Kiesel, CCRC (CC); Eileen Knips, RN, CCRC, CRA (OP/OCT); Crystal Peters, CCRC (CC); Paul Raskauskas, MD (O); Etienne Schoeman (OP/OCT); Ashish Sharma, MD (O); Glenn Wing, MD (O). University of Wisconsin Madison (Madison, WI): Suresh R. Chandra, MD (PI); Michael Altaweel, MD (O); Barbara Blodi, MD (O); Kathryn Burke, BA (VA/R); Kristine A. Dietzman, (CC); Justin Gottlieb, MD (O); Gene Knutson (OP/OCT); Denise Krolnik (OP/OCT); T. Michael Nork, MD (O); Shelly Olson (VA/R); John Peterson, CRA (OP/OCT); Sandra Reed (OP/OCT); Barbara Soderling (VA/R); Guy Somers (VA/R); Thomas Stevens, MD (O); Angela Wealti, (CC). Duke University Eye Center (Durham, NC): Srilaxmi Bearelly, MD (PI); Brenda Branchaud (VA/R); Joyce W. Bryant, COT, CPT (CC/VA/R); Sara Crowell (CC/VA); Sharon Fekrat, MD (O); Merritt Gammage (OP/OCT); Cheala Harrison, COA (VA/R); Sarah Jones (VA); Noreen McClain, COT, CPT, CCRC (VA/R); Brooks McCuen, MD (O); Prithvi Mruthyunjaya, MD (O); Jeanne Queen, CPT (OP/OCT); Neeru Sarin, MBBS (VA/R); Cindy Skalak, RN, COT (VA/R); Marriner Skelly, CRA (OP/OCT); Ivan Suner, MD (O); Ronnie Tomany (OP/OCT); Lauren Welch (OP/OCT). University of California-Davis Medical Center (Sacramento, CA): Susanna S. Park, MD, PHD (PI); Allison Cassidy (VA/R); Karishma Chandra (OP/OCT); Idalew Good (VA/R); Katrina Imson (CC); Sashi Kaur (OP/OCT); Helen Metzler, COA, CCRP (CC/VA/R); Lawrence Morse, MD, PHD (O); Ellen Redenbo, ROUB (OP/OCT); Marisa Salvador (VA/R); David Telander, MD (O); Mark Thomas, CRA (OCT); Cindy Wallace, COA (CC). University of Louisville School of Medicine, KY (Louisville, KY): Charles C. Barr, MD (PI); Amanda Battcher (VA/R); Michelle Bottorff, COA (CC/OCT); Mary Chasteen (VA/R); Kelly Clark (VA/R); Diane Denning, COT (OCT); Amy Schultz (OP); Evie Tempel, CRA, COA (OP); Greg K. Whittington, MPS, PSY (CC). Retina Associates of Kentucky (Lexington, KY): Thomas W. Stone, MD (PI); Todd Blevins (OP/OCT); Michelle Buck, COT, (VA/R/OCT); Lynn Cruz, COT (CC); Wanda Heath (VA/R); Diana Holcomb (VA/R); Rick Isernhagen, MD (O); Terri Kidd, COA (OCT); John Kitchens, MD (O); Cathy Sears, CST, COA (VA/R); Ed Slade, CRA, COA (OP/OCT); Jeanne Van Arsdall, COA (VA/R); Brenda VanHoose, COA (VA/R); Jenny Wolfe, RN (CC); William Wood, MD (O). Colorado Retina Associates (Denver, CO): John Zilis, MD (PI); Carol Crooks, COA (VA/R); Larry Disney (VA/R); Mimi Liu, MD (O); Stephen Petty, MD (O); Sandra Sall, ROUB, COA (CC/VA/R/OP/OCT). University of Iowa Hospitals & Clinics (Iowa City, IA): James C. Folk, MD (PI); Tracy Aly, CRA (OP/OCT); Abby Brotherton (VA); Douglas Critser, CRA (OP/OCT); Connie J. Hinz, COT, CCRC (CC/VA/R); Stefani Karakas, CRA (OP/OCT); Cheyanne Lester (VA/R); Cindy Montague, CRA (OP/OCT); Stephen Russell, MD (O); Heather Stockman (VA/R); Barbara Taylor, CCRC (VA/R); Randy Verdick, FOPS (OP/OCT). Retina Specialists (Towson, MD): John T. Thompson, MD (PI) ; Barbara Connell (VA/R); Maryanth Constantine (CC); John L. Davis Jr (VA/R); Gwen Holsapple (VA/R); Lisa Hunter (OP/OCT); C. Nicki Lenane (CC/VA/R/OCT); Robin Mitchell (CC); Leslie Russel, CRA (OP/OCT); Raymond Sjaarda, MD (O). Retina Consultants of Houston (Houston, TX): David M. Brown, MD (PI); Matthew Benz, MD (O); Llewellyn Burns (OCT); JoLene G. Carranza, COA, CCRC (CC); Richard Fish, MD (O); Debra Goates (VA/R); Shayla Hay (VA/R); Theresa Jeffers, COT (VA/R); Eric Kegley, CRA, COA (OP/OCT); Dallas Kubecka (VA/R); Stacy McGilvra (VA/R); Beau Richter (OCT); Veronica Sneed, COA (VA/R); Cary Stoever (OCT); Isabell Tellez (VA/R); Tien Wong, MD (O). Massachusetts Eye & Ear Infirmary/Harvard Vanguard Medical Associates (Boston, MA): Ivana Kim, MD (PI); Christopher Andreoli, MD (O); Leslie Barresi, CRA, COA, OCT-C (VA/OP/OCT); Sarah Brett (OP); Charlene Callahan (OP); Karen Capaccioli (OCT); William Carli, COA (VA/R/OCT); Matthew Coppola, COA (VA); Nicholas Emmanuel (CC); Claudia Evans, OD (VA/R); Anna Fagan, COA (VA/R); Marcia Grillo (OCT); John Head, CRA, OCT-C (OP/OCT); Troy Kieser, COA, OCT-C (CC/VA/R); Ursula Lord, OD (VA/R); Edward Miretsky (CC); Kate Palitsch (OCT); Todd Petrin, RN (OCT); Liz Reader (CC); Svetlana Reznichenko, COA (VA); Mary Robertson, COA (VA); Demetrios Vavvas, MD, PHD (O). Palmetto Retina Center (West Columbia, SC): John Wells, MD (PI); Cassie Cahill (VA/R); W. Lloyd Clark, MD (O); Kayla Henry (VA/R); David Johnson, MD (O); Peggy Miller (CC/VA/R); LaDetrick Oliver, COT (OP/OCT); Robbin Spivey (OP/OCT); Mallie Taylor (CC). Retina and Vitreous of Texas (Houston, TX): Michael Lambert, MD (PI); Kris Chase (OP/OCT); Debbie Fredrickson, COA (VA/R); Joseph Khawly, MD, FACS (O); Valerie Lazarte (VA/R); Donald Lowd (OP/OCT); Pam Miller (CC); Arthur Willis, MD (O). Long Island Vitreoretinal Consultants (Great Neck, NY): Philip J. Ferrone, MD (PI); Miguel Almonte (OCT); Rachel Arnott, (CC); Ingrid Aviles (VA/R/OCT); Sheri Carbon (VA/R); Michael Chitjian (OP/OCT); Kristen DAmore (CC); Christin Elliott (VA/R); David Fastenberg, MD (O); Barry Golub, MD (O); Kenneth Graham, MD (O); Ann-Marie Lavorna (CC); Laura Murphy (VA/R); Amanda Palomo (VA/R); Christina Puglisi (VA/R); David Rhee, MD (O); Juan Romero, MD (O); Brett Rosenblatt, MD (O); Glenda Salcedo (OP/OCT); Marianne Schlameuss, RN (CC); Eric Shakin, MD (O); Vasanti Sookhai (VA/R). Wills Eye Institute (Philadelphia, PA): Richard Kaiser, MD (PI); Elizabeth Affel, MS, OCT-C (OCT); Gary Brown, MD (O); Christina Centinaro (CC); Deborah Fine, COA (OCT); Mitchell Fineman, MD (O); Michele Formoso (CC); Sunir Garg, MD (O); Lisa Grande (VA/R); Carolyn Herbert (VA/R); Allen Ho, MD (O); Jason Hsu, MD (O); Maryann Jay (OCT); Lisa Lavetsky (OCT); Elaine Liebenbaum (OP); Joseph Maguire, MD (O); Julia Monsonego (OP); Lucia O’Connor (OCT); Carl Regillo, MD (O); Maria Rosario (DE); Marc Spirn, MD (O); James Vander, MD (O); Jennifer Walsh (VA/R). Ohio State University Eye Physicians & Surgeons-Retina Division (Dublin, OH): Frederick H. Davidorf, MD (PI); Amanda Barnett (OP/OCT); Susie Chang, MD (O); John Christoforidis, MD (O); Joy Elliott (CC); Heather Justice (VA/R); Alan Letson, MD (O); Kathryne McKinney, COMT (CC); Jeri Perry, COT (VA/R); Jill A. Salerno, COA (CC); Scott Savage (OP); Stephen Shelley (OCT). Retina Associates of Cleveland (Beachwood, OH): Lawrence J. Singerman, MD (PI);Joseph Coney, MD (O); John DuBois (OP/OCT); Kimberly DuBois, LPN, CCRP, COA (VA/R); Gregg Greanoff, CRA (OP/OCT); Dianne Himmelman, RN, CCRC (CC); Mary Ilc, COT (VA/R); Elizabeth Mcnamara (VA/R/OP); Michael Novak, MD (O); Scott Pendergast, MD (O); Susan Rath, PA-C (CC); Sheila SmithBrewer, CRA (OP/OCT); Vivian Tanner, COT, CCRP (VA/R); Diane E. Weiss, RN, (CC); Hernando Zegarra, MD (O). Retina Group of Florida (Fort Lauderdale, FL): Lawrence Halperin, MD (PI); Patricia Aramayo (OCT); Mandeep Dhalla, MD (O); Brian Fernandez, MD (OP/OCT); Cindy Fernandez, MD (CC); Jaclyn Lopez (CC); Monica Lopez (OCT); Jamie Mariano, COA (VA/R); Kellie Murphy, COA (OCT); Clifford Sherley, COA (VA/R); Rita Veksler, COA (OP/OCT). Retina-Vitreous Associates Medical Group (Beverly Hills, CA): Firas Rahhal, MD (PI); Razmig Babikian (DE); David Boyer, MD (O); Sepideh Hami (DE); Jeff Kessinger (OP/OCT); Janet Kurokouchi (CC); Saba Mukarram (VA/R); Sarah Pachman (VA/R); Eric Protacio (OCT); Julio Sierra (VA/R); Homayoun Tabandeh, MD, MS, FRCP (O); Adam Zamboni (VA/R). Elman Retina Group, P.A. (Baltimore, MD): Michael Elman, MD (PI); Tammy Butcher (CC); Theresa Cain (OP/OCT); Teresa Coffey, COA (VA/R); Dena Firestone (VA/R); Nancy Gore (VA/R); Pamela Singletary (VA/R); Peter Sotirakos (OP/OCT); JoAnn Starr (CC). University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (Chapel Hill, NC): Travis A. Meredith, MD (PI); Cassandra J. Barnhart, MPH (CC/VA/R); Debra Cantrell, COA (VA/R/OP/OCT); RonaLyn EsquejoLeon (OP/OCT); Odette Houghton, MD (O); Harpreet Kaur (VA/R); Fatoumatta NDure, COA (CC). Ophthalmologists Enrolling Patients but No Longer Affiliated with a CATT Center: Ronald Glatzer, MD (O); Leonard Joffe, MD (O); Reid Schindler, MD (O). Resource Centers Chairman’s Office (Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, OH): Daniel F. Martin, MD (Chair); Stuart L. Fine, MD (Vice-Chair; University of Colorado, Denver CO); Marilyn Katz (Executive Assistant). Coordinating Center (University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA): Maureen G. Maguire, PhD (PI); Mary Brightwell-Arnold, SCP (Systems Analyst); Ruchira Glaser, MD (Medical Monitor); Judith Hall (Protocol Monitor); Sandra Harkins (Staff Assistant); Jiayan Huang, MS (Biostatistician); Alexander Khvatov, MS (Systems Analyst); Kathy McWilliams, CCRP (Protocol Monitor); Susan K. Nolte (Protocol Monitor); Ellen Peskin, MA, CCRP (Project Director); Maxwell Pistilli, MS, MEd (Biostatistician); Susan Ryan (Financial Administrator); Allison Schnader (Administrative Coordinator); Gui-shuang Ying, PhD (Senior Biostatistician). OCT Reading Center (Duke University, Durham, NC): Glenn Jaffe, MD (PI); Jennifer Afrani-Sakyi (CATT PowerPoint Presentations); Brannon Balsley (OCT Technician Certifications); Linda S. Bennett (Project Manager); Adam Brooks (Reader/SD-Reader); Adrienne Brower-Lingsch (Reader); Lori Bruce (Data Verification); Russell Burns (Senior Technical Analyst/Senior Reader/SD Reader/OCT Technician Certifications); Dee Busian (Reader); John Choong (Reader); Lindsey Cloaninger (Reader Reliability Studies/Document Creation/CATT PPT Files); Francis Char DeCroos (Research Associate); Emily DuBois (Data Entry); Mays El-Dairi (Reader/SD-Reader); Sarah Gach (Reader); Katelyn Hall (Reader Reliability Studies/Data Verification/Document Creation); Terry Hawks (Reader); Cheng-Chenh Huang (Reader); Cindy Heydary (Senior Reader/Quality Assurance Coordinator/SD Reader/Data Verification); Alexander Ho (Reader, Transcription); Shashi Kini (Data Entry/Transcription); Michelle McCall (Data Verification); Daaimah Muhammad (Reader Feedback); Jayne Nicholson (Data Verification); Jeanne Queen (Reader/SD-Reader); Pamela Rieves (Transcription); Kelly Shields (Senior Reader); Cindy Skalak (Reader); Adam Specker (Reader); Sandra Stinnett (Biostatistician); Sujatha Subramaniam (Reader); Patrick Tenbrink (Reader); Cynthia Toth, MD (Director of Grading); Aaron Towe (Reader); Kimberly Welch (Data Verification); Natasha Williams (Data Verification); Katrina Winter (Senior Reader); Ellen Young (Senior Project Manager). Fundus Photograph Reading Center (University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA): Juan E. Grunwald, MD (PI); Judith Alexander (Director); Ebenezer Daniel, MBBS, MS, MPH, PhD (Director); Elisabeth Flannagan (Administrative Coordinator); E. Revell Martin (Reader); Candace Parker (Reader); Krista Sepielli (Reader); Tom Shannon (Systems Analyst); Claressa Whearry (Data Coordinator). National Eye Institute, National Institutes of Health: Maryann Redford, DDS, MPH (Program Officer). Committees Executive Committee: Daniel F. Martin, MD (chair); Robert L. Avery, MD; Sophie J. Bakri, MD; Ebenezer Daniel, MBBS, MS, MPH; Stuart L. Fine, MD; Juan E. Grunwald, MD; Glenn Jaffe, MD, Marcia R. Kopfer, BS, COT; Maureen G. Maguire, PhD; Travis A. Meredith, MD; Ellen Peskin, MA, CCRP; Maryann Redford, DDS, MPH; David F. Williams, MD. Operations Committee: Daniel F. Martin, MD (chair); Linda S. Bennett; Ebenezer Daniel, MBBS, MS, MPH; Frederick L. Ferris III, MD; Stuart L. Fine, MD; Juan E. Grunwald, MD; Glenn Jaffe, MD; Maureen G. Maguire, PhD; Ellen Peskin, MA, CCRP; Maryann Redford, DDS, MPH; Cynthia Toth, MD. Clinic Monitoring Committee: Ellen Peskin, MA, CCRP (chair); Mary Brightwell-Arnold, SCP; Joan DuPont; Maureen G. Maguire, PhD; Kathy McWilliams, CCRP; Susan K. Nolte. Data and Safety Monitoring Committee: Lawrence M. Friedman, MD (chair); Susan B. Bressler, MD; David L. DeMets, PhD; Martin Friedlander, MD, PhD; Mark W. Johnson, MD; Anne Lindblad, PhD; Douglas W. Losordo, MD, FACC; Franklin G. Miller, PhD.

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available at www.ophthalmologyretina.org.