Abstract

Background:

Lack of recognition in national programs, poor referral system, and non-availability of trained human resources are the important barriers for the delivery of perinatal depression (PND) services in low- and middle-income countries (LAMICs). To address this there is an urgent need to develop an integrative and non-specialist-based stepped care model. As part of its research thrust on target areas of India’s National Mental Health Programme (NMHP), the Indian Council of Medical Research funded a research project on the outcome of PND at four sites. In this article, we describe the development of the primary health care worker-based stepped care model and brief psychological intervention for PND.

Methods:

A literature review focused on various aspects of PND was conducted to develop a model of care and intervention under NMHP. A panel of national and international experts and stakeholders reviewed the literature, opinions, perspectives, and proposal for different models and interventions, using a consensus method and WHO implementation toolkit.

Results:

A consensus was reached to develop an ANM (Auxillary nurse midwife)-based stepped-care model consisting of the components of care, training, and referral services for PND. Furthermore, a brief psychological intervention (BIND-P) was developed, which includes the components of the low-intensity intervention (eg, exercise, sleep hygiene).

Conclusion:

The BIND-P model and intervention provide a practical approach that may facilitate effective identification, treatment, and support women with PND. We are currently evaluating this model across four study sites in India, which may help in the early detection and provision of appropriate and integrative care for PND.

Keywords: brief psychological intervention, depression, low-and middle-income countries, perinatal depression, primary care

1 |. INTRODUCTION

Perinatal depression (PND) affects up to 18% to 20% of women in low- and middle-income countries (LAMICs) including India (Upadhyay et al., 2017) and has deleterious effects on the health of mother and child (Dadi, Miller, Bisetegn, & Mwanri, 2020). Further, it remains under-recognized, under-diagnosed, and under-treated due to stigma, poor awareness, cultural factors, lack of adequate human resources, misconception or myths, and financial constraints in these countries (Ransing, Agrawal, Bagul, & Pevekar, 2020; Ransing et al., 2020). Despite growing awareness of the need for detection and treatment of PND, barriers in the health care system such as overburdened mental health professionals, unavailability of an integrative model of care, and the burden of co-morbid medical disorders, make intervention delivery difficult (Jones, 2019). There is an urgent need to address the burden of PND and to reduce the treatment gap in India.

Evidence from high-income countries for brief psychological interventions to screen and manage PND is promising (Stephens, Ford, Paudyal, & Smith, 2016). Also, published literature suggests that screening for PND, supplemented with interventions, is associated with a 2 to 4-fold increase in the use of perinatal mental health care services (detection, assessment, referral, and treatment) when compared to screening alone (Byatt, Levin, Ziedonis, Moore Simas, & Allison, 2015). Multipronged strategies targeted at multiple levels of the health-care system are needed to address the barriers for delivery of perinatal mental health services (Jones, 2019). India needs an integrated model of care aimed at training primary health care workers (HCWs) to address the burden of PND. The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends the use of a stepped-care model, use of self-help psychological interventions, and non-specialist based delivery of interventions to reduce the treatment gap (Dua et al., 2016; Haugh et al., 2019; Hermens, Muntingh, Franx, van Splunteren, & Nuyen, 2014). A range of potentially scaleable psychological interventions exists (WHO, 2017). However, published evidence suggests that these models are easy to recommend, but difficult to implement in practice (Hermens et al., 2014) and the effectiveness of such interventions in LAMICs is limited (Arjadi, Nauta, Chowdhary, & Bockting, 2015).

Non-specialist interventions for depression provide an option for delivery of services where healthcare resources are scarce. However, these interventions or models of care should be flexible enough to meet the needs of Indian women affected by a wide range of adversities such as physical illness (eg, anemia, malnutrition), lack of access to primary care, poverty, and gender-based violence (Priya, Chaturvedi, Bhasin, Bhatia, & Radhakrishnan, 2019; Swaminathan et al., 2019; Tandon, Jain, & Malhotra, 2018). Furthermore, psychological interventions or models should be applicable even in rural or remote regions. Such interventions should be effective across a wide range of delivery methods such as those that are HCWs-based, self-guided, or with minimal supervision (eg, self-help skills requiring brief monitoring).

To address these limitations, there is a need for collaborative efforts among various stakeholders (government, private), policymakers, mental health professionals, public health experts, and researchers. This article describes one such collaborative effort—the process of development of a model of care and intervention for PND using the consensus method. This model is currently being implemented as a part of randomized control trial across four centers in India and is funded by the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR).

2 |. METHODS

This study aims to describe the process of development of a scalable model of care for PND, a brief intervention manual, training process, and practical guidance for implementation, drawn from scientific literature, the professional experience of the authors, and experts. To this end, the authors reviewed resources with mentors from India, United States, and Egypt in a workshop. The initial plan for various aspects of the intervention was developed after extensive discussions among the authors, fellow researchers, and teachers and mentors in a capacity building workshop organized by the ICMR, PGIMER- Dr. RML Hospital, University of Pittsburgh, and Universities of Mansoura and Cairo (Hawk et al., 2017).

We examined the literature for: (a) systematic reviews on the clinical and psychosocial presentation of PND across the world and India; (b) epidemiological research on PND; (c) existing interventions and models in India or other countries; (d) challenges in implementations and strategies using WHO implementation toolkit (WHO, 2014). The preliminary consensus draft of the model and interventions was then further discussed with obstetricians, pediatricians, psychiatrists, psychologists, and public health experts outside the first group working at all four centers over 8 months. After extensive discussion and revision of the model, interventions, and delivery system, a final draft was prepared and circulated. The approved model and intervention are being implemented and evaluated for efficacy, applicability, and cross-cultural acceptability across four centers in India.

3 |. RESULTS

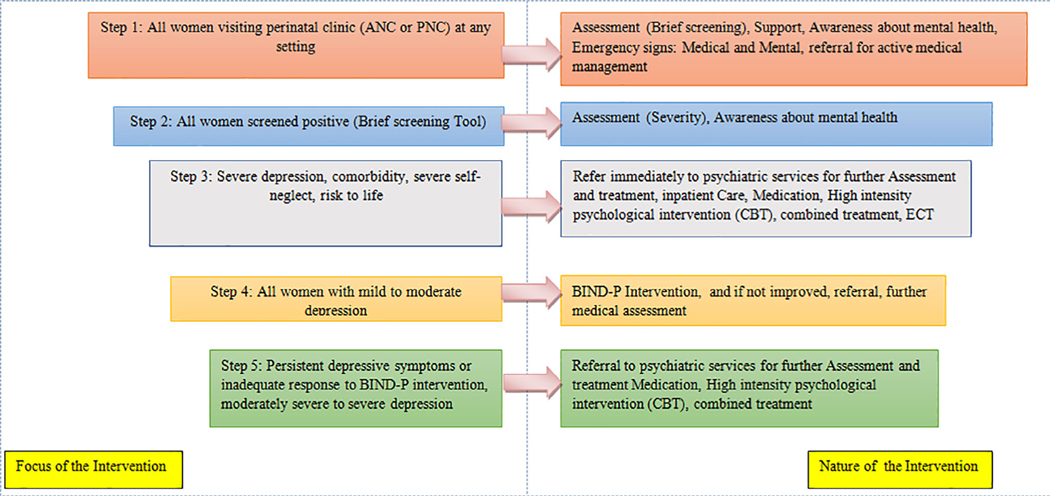

Initially, we considered implementing the WHO’s Mental Health Gap Action Programme (mhGAP) and Thinking healthy manual (WHO, 2008). But considering the human resources, national priorities towards maternal mental health, and the possibility of future integration of perinatal mental health in the national health mission, the BIND-P was designed for implementation across various levels of the Indian health care delivery systems. Further, the experts favored improving referral services over non-specialist based interventions. We conceptualized a stepped care model of care for PND that enables the screening and delivery of a brief psychological intervention (BIND-P Intervention) (Figure 1,2). The model depicts the assessment, referral, and management protocol for HCWs and mental health professionals. The process of development included these core aspects: theoretical background, screening and assessment for PND, the content of the intervention, delivery of the intervention and monitoring, and guidance-training model.

FIGURE 1.

BIND-P model for PND services

FIGURE 2.

Steps for management of PND in the BIND-P model

The BIND-P model focusses on primary HCWs [e.g. Accredited Social Health Activist (ASHA), Auxiliary nurse midwife (ANM), Nurse, and Multipurpose Health Worker (MPW)] based care. The primary HCWs based models have been useful in many LMIC countries including India (George, Kumar, & Girish, 2020; Lund et al., 2020; Stansert Katzen et al., 2020). Studies reported better compliance, increased resilience and coping strategies, and improved perceptions about health services leading to an increase in referral rate with these models. In India, ANM is regarded as one of the trusted HCWs and is the pillar of several national programs (Mavalankar & K, 2010). The experts as well as key stakeholders opined that ANMs are more acceptable, accessible, and trusted in various public health settings (clinical or community) and therefore an ANM-based delivery model will be more acceptable and utilizable. Further, the model is flexible enough to fit into all tiers of the Indian Health care system (Primary, secondary, and tertiary) and adaptable to different settings and resource availability.

Screening and Assessment for PND (Figure 2) starts with a brief assessment which includes PHQ-2 for screening and If score (≥3), PHQ-9 for severity assessment. It also attempts to identify the multiple potential triggers that may prompt the referral of women for assessment at higher centers. Some of these triggers are indicative of underlying serious medical or mental conditions. The decision to refer would also be strongly supported if there is a previous history of mental illness. This likely to influence the likelihood of referral and access to diagnosis and treatment of PND.

The BIND-P intervention will be delivered over three sessions (fortnightly, 15 to 20 minutes each session) (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Components of BIND-P intervention

| Session | Components/steps | Tools required |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Psycho-education | 1. HCW will begin the conversation explaining the benefits of good mental health for a child’s development (most mothers were majorly concerned about the child’s health only) 2.Concept of maternal psycho-social wellbeing and its role in infant or child’s health 3. A brief discussion of Biopsychosocial model of PND, modalities of treatment available |

Video or flipchart |

| 2. Relaxation exercise | 1.Progressive muscle relaxation 2.Breathing exercises 3. Visual guided imagery |

Video or flipchart, Monitoring chart Activity workbook |

|

3. Health Promotion |

1. Nutrition 2. Exercise 3. Social support 4. Sleep hygiene 5. Training For Healthy Thinking |

Video or flipchart, Activity workbook (Nutrition, sleep, exercise) |

3.1 |. First session: Psycho-education

The session is split into two parts each of approximately 7.5 minutes. In the first part, ANM (HCW) will provide a brief introduction about herself, rapport building, and discussion about reports of PHQ-2 or PHQ-9. During the interactive part of the session, the ANM will educate in more detail about mental health, depression, and the core therapeutic component for three sessions and coaches the woman to complete activities for the week using the BIND-P monitoring chart, activity workbook [(Table1.0, supplementary files (chart 1, 2,3)], and follow-ups.

3.2 |. Second session: Relaxation exercise

During this session, previous sessions activities will be briefly recapped and ANM will provide a brief and simple progressive muscle relaxation, breathing exercises, and visual guided imagery. Besides, women will be informed about the activity workbook to be completed at home and monitoring chart to be brought in the next visit. This is done to instill a sense of involvement in the therapeutic process and provide greater encouragement for later sessions.

3.3 |. Third session: Health promotion

This session will be focused on health promotion and emphasize nutrition, exercise, social support, sleep hygiene, and training for thinking healthy. The self-explanatory diet, exercise, and sleep chart will be provided to women with PND for self-monitoring of activity. She will be trained in healthy thinking and social support.

The HCWs (ANM) will assess and deliver the BIND-P intervention at the first contact with women in maternal and child services of any system. This is conceptualized to simplify and systematize the integration of mental health in routine mother-child services. ANM will follow the additional elements of this standard protocol (welcome address, registration, baseline assessment protocol) of routine care. At the place of delivery of the sessions, information on the effects of mental health on the wellbeing of child and mother will be displayed. The ANM will keep all records of weekly scores on PHQ-2 or PHQ-9 and an overview of sessions completed using the activity workbook [supplementary files (chart1, 2,3)]. She will provide necessary psycho-social support and close monitoring to the women with PND. The activity workbooks will be provided for monitoring of activities (eg, exercise, sleep). Also, telephonic supports will be provided to all women during pregnancy.

The BIND-P Guidance and training model has been prepared to train the HCW in the BIND-P intervention and stepped care model (Ransing et al., 2020). The training involves didactic lectures, video presentations, self-assessments, group work, suggested readings, and onsite training. The training is offered over three days with monthly follow up session and is free of charge to ANM. Also, professionals such as clinical psychologists will provide the support as and when required. The training manual consists of structured training for each session, case discussions, questions and assessments, active listening, and communication skills. The ANM will also be trained to identify, assess, manage, and report risks, adverse or serious adverse events encountered during the support sessions to the clinical psychologist or psychiatrist. The implementation of the BIND-P model is currently ongoing across four sites of India where authors work.

4 |. DISCUSSION

In India, the mental health-care workforce has been extremely limited, as evidenced by the large treatment gap, that is, the proportion of patients in need who are not receiving appropriate medical care (NMHS, 2016). WHO has estimated the treatment gap for mental disorders to be between 76% and 85% in LMICs compared to 35% to 50% in high-income countries (HICs) (Demyttenaere et al., 2004). The WHO mhGAP recommends training of non-specialist health-care providers (primary care physicians and HCWs) to deliver effective, evidence-based treatments at the community level(WHO, 2008). It is envisaged that the BIND-P model could be used to strengthen the capacity of HCWs for early detection of, screening for, intervention in, and management of PND. We designed a systematic and integrative approach to deliver the components of intervention for women with PND through HCWs (Nurse, ANMs, or ASHA workers) at the primary care, clinical setting, and community level. Furthermore, we attempted to address several key questions related to the implementation of PND services in India with the provision of a model of care and intervention which was developed after a review of available scientific literature, experts’ opinions, stakeholders’ perspectives, and future potential for scaling up under NMHP.

Research on screening women for PND is limited in India, although several scales are available to screen women for PND, such as the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS), PHQ-9, and Whooley’s questionnaire (Bavle et al., 2016; Dere, Varotariya, Ghildiyal, Sharma, & Kaur, 2019; Ransing, Deshpande, et al., 2020). We preferred to use the PHQ-2 and PHQ-9, as these scales have been translated and validated in several Indian languages and used in various contexts (Ganguly et al., 2013; Shidhaye, Gangale, & Patel, 2016) and demonstrated good psychometric properties for screening the population with different disorders (Ambaw, Mayston, Hanlon, & Alem, 2017; Reddy, Philpot, Ford, & Dunbar, 2010). Furthermore, we are training the HCW (ANM) in PHQ-9, or PHQ-2 administration, which will not only beneficial to detect PND but also to extend screening and intervention for different disorders (eg, diabetes, hypertension) under the National Health Mission in the future.

The BIND-P intervention is primarily conceptualized as a psychosocial intervention directed towards the prevention and treatment of PND. It also emphasizes prevention of common medical disorders (CMD) (eg, anemia) and promotion of health. It consists of the core strategies of PND management at a primary level and behavioral activation. Evidence suggests that exercise, psycho-education, diet, and sleep hygiene are helpful to promote perinatal mental health, treat PND, and prevent CMD (Chowdhary et al., 2014; Sikander et al., 2019). The intervention was therefore adapted to focus on these components along with identifying strengths and increasing social support. The intervention is designed to be flexible enough to allow for additional techniques to be added in the future to make it more comprehensive. These needs were considered in the design process through consultations with experts. These consultations provided important information that informed the development of the content (eg, easy adaptation of content), guidance model, and delivery system. It must be noted that due to the potential threat of a high degree of staff turnover and difficulties in attending the ANC clinic for ANC women in a rural and remote region, the number of sessions was reduced to three.

In India, anemia and other medical disorders (eg, hypothyroidism) during pregnancy are highly prevalent and often remain undetected or un-treated leading to pregnancy-related complications (Dhanwal et al., 2016; Tandon et al., 2018). There is a significant overlap in the clinical presentation of depression and these medical conditions leading to high false-positive in the PHQ-9 (Marcus & Heringhausen, 2009; Ransing, Deshpande, et al., 2020; Tudosa et al., 2010). In India, the ANM’s are adequately trained in the detection of these CMD. Therefore, an ANM based model and intervention can reduce adverse outcomes such as low birth weight, pre-term labor by improving nutrition, sleep, and reducing the symptoms of depression. Due to the preference for a male child in India, women with a previous female child are often more depressed (Patel, Rodrigues, & DeSouza, 2002) due to gender-related expectations. Therefore, we decided to include more pictures of female children in the preparation of the manual or project materials.

The BIND-P model offers primary level interventions to perinatal women, including self-help interventions (eg, information and education-based intervention), self-guided therapeutic interventions, HCWs-supported therapeutic interventions, and support systems, which have shown promise in treating PND in previous studies (Chowdhary et al., 2014). Further, the greater time and resources for engagement may improve the utilization and effectiveness of this intervention.

The BIND-P model of care may be adapted to other Indian states or countries with low-resource settings. Further, this model is designed as flexible for implementation in government or private settings providing perinatal care. However, qualitative and quantitative research is needed before any adaptation. Intervention characteristics and implementation processes often have the greatest positive impact on implementation. In terms of the BIND-P intervention, the relative advantages (three sessions) and strength of evidence of the content appear to be important factors facilitating the implementation. Processes used to develop a model of care and intervention also served to facilitate the implementation, especially in terms of engaging diverse stakeholders (eg, nurses, psychiatrist).

We expect some challenges during the implementation of this model of care. Barriers for implementation of the model can be the lack of readiness of the system, limited resources, lower relative priority for mental health compared to other maternal medical illness, patient workload, lack of incentives to ANM, low adaptability (support and length of treatment), negative beliefs, and poor motivation. However, implementation processes such as planning, engaging, reflecting, and evaluation can positively impact implementation in all settings.

The development of the BIND-P has been carried out in consultations with stakeholders and as per the WHO implementation toolkit (WHO, 2014). We attempted to understand the implementation barriers and facilitators, which will help to improve the utility, accessibility, acceptability, and sustainability of the model and intervention within the different frameworks of the Indian health care system (private and government, urban and rural, tertiary, and secondary) and NMHP. Further, the content of the intervention and narrated videos can improve access for people with low literacy. The BIND-P model and intervention have a more scalable potential than other interventions.

The BIND-P intervention is a non-personalized intervention aimed to improve adherence and outcomes. The personalization of the intervention often contributes to non-therapeutic discussion and drifts away from the key task of intervention, ultimately resulting in a reduction in patient adherence and outcomes. In terms of limitations, it should be noted that the consensus method is prone to subject bias, and opinion bias.

Through the BIND-P model of care, the training is being offered to ANMs at each center. The findings from the first batch of trained participants report a considerable increase in knowledge, skill, and confidence in dealing with women with PND. We also observed an increase in the capacity to screen, offer brief interventions, and offer referral services for PND. In upcoming trials, both model and care will be tested across four centers and three Indian Languages with support from ICMR to examine the effectiveness of the intervention.

The facilitators and barriers to implementation are likely to be linked to the model of implementation, the local population, and the health care system. Therefore, these factors are further evaluated through qualitative interviews or validated scales for generalization of findings. Lessons learned from this model and intervention can assist policymakers, researchers, and stakeholders to implement a perinatal intervention in their countries and other parts of India.

5 |. CONCLUSIONS

The BIND-P is a new stepped care model of care and intervention, primary HCWs based, aimed to address PND more comprehensively and effectively from a public health perspective. It can contribute to the understanding of factors that may influence the implementation of PND services within clinical and community settings, and serve to identify potential strategies for improving implementation in the future. It may be valuable to explore coverage, reach, outcomes, and implementation of the BIND-P model and intervention in different settings.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work is part of the BIND-P project (CTRI/2018/07/014836). The work was supported by the Indian Council Medical Research (ICMR) under Capacity Building Projects for National Mental Health Programme, ICMR-NMHP. We thank Dr. Soumya Swaminathan (then Secretary, Dept. of Health Research, DHR), Dr. Balram Bhargav, current Secretary DHR, Prof. V.L. Nimgaonkar, Dr. Ravinder Singh, Dr. Harpreet Singh, and Dr. Krushnaji Kulkarni. We thank the faculty of “Cross-Fertilized Research Training for New Investigators in India and Egypt” (D43 TW009114, HMSC File No. Indo-Foreign/35/M/2012-NCD-1, funded by Fogarty International Centre, NIH). We are also thankful to the National Coordinating Unit of ICMR for NMHP Projects for their constant support and guidance. We thank the Data Management Unit of ICMR for designing the database. The content of this manuscript is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of NIH or ICMR. NIH and ICMR had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Funding information

Indian Council of Medical Research, Grant/Award Number: No.5/4-4/151/M/2017/NCD-I

SOURCE OF FUNDING

This study was funded by Indian Council of Medical Research ICMR), New Delhi (No.5/4-4/151/M/2017/NCD-I).

Abbreviations:

- PND

Perinatal depression

- HCW

Health care worker

- NMHP

National Mental Health Program

- ICMR

Indian Council of Medical Research

- BIND-P

Brief Intervention by Nurse for Depression in Pregnancy

- mhGAP

Mental Health Gap Action Programme

- ANM

Auxiliary nurse-midwife

- ASHA

Accredited Social Health Activist

- ANC

Antenatal Clinic

- PNC

Postnatal Clinic

Footnotes

ETHICS STATEMENT

Ethical approvals were obtained from the BKL Walwalkar Rural Medical College; Maharashtra, Lady Hardinge Medical College; New Delhi, Yenepoya Medical College; Karnataka and Dharwad Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences (DIMHANS); Karnataka.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.

REFERENCES

- Ambaw F, Mayston R, Hanlon C, & Alem A. (2017). Burden and presentation of depression among newly diagnosed individuals with TB in primary care settings in Ethiopia. BMC Psychiatry, 17(1), 57. 10.1186/s12888-017-1231-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arjadi R, Nauta MH, Chowdhary N, & Bockting CLH (2015). A systematic review of online interventions for mental health in low and middle income countries: A neglected field. Global Mental Health (Cambridge, England), 2, e12. 10.1017/gmh.2015.10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bavle AD, Chandahalli AS, Phatak AS, Rangaiah N, Kuthandahalli SM, & Nagendra PN (2016). Antenatal depression in a tertiary care hospital. Indian Journal of Psychological Medicine, 38 (1), 31–35. 10.4103/0253-7176.175101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byatt N, Levin LL, Ziedonis D, Moore Simas TA, & Allison J. (2015). Enhancing participation in depression care in outpatient perinatal care settings: A systematic review. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 126(5), 1048–1058. 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhary N, Sikander S, Atif N, Singh N, Ahmad I, Fuhr DC, … Patel V. (2014). The content and delivery of psychological interventions for perinatal depression by non-specialist health workers in low and middle income countries: A systematic review. Best Practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology, 28(1), 113–133. 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2013.08.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dadi AF, Miller ER, Bisetegn TA, & Mwanri L. (2020). Global burden of antenatal depression and its association with adverse birth outcomes: An umbrella review. BMC Public Health, 20(1), 173. 10.1186/s12889-020-8293-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demyttenaere K, Bruffaerts R, Posada-Villa J, Gasquet I, Kovess V, Lepine JP, … WHO World Mental Health Survey Consortium. (2004). Prevalence, severity, and unmet need for treatment of mental disorders in the World Health Organization world mental health surveys. JAMA, 291(21), 2581–2590. 10.1001/jama.291.21.2581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dere S, Varotariya J, Ghildiyal R, Sharma S, & Kaur DS (2019). Antenatal preparedness for motherhood and its association with antenatal anxiety and depression in first time pregnant women from India. Industrial Psychiatry Journal, 28(2), 255. 10.4103/ipj.ipj_66_19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhanwal DK, Bajaj S, Rajput R, Subramaniam KAV, Chowdhury S, Bhandari R, … Shriram U. (2016). Prevalence of hypothyroidism in pregnancy: An epidemiological study from 11 cities in 9 states of India. Indian Journal of Endocrinology and Metabolism, 20(3), 387–390. 10.4103/2230-8210.179992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dua T, Barbui C, Patel AA, Tablante EC, Thornicroft G, Saxena S, & WHO’s mhGAP Guideline team. (2016). Discussion of the updated WHO recommendations for mental, neurological, and substance use disorders. The Lancet. Psychiatry, 3(11), 1008–1012. 10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30184-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganguly S, Samanta M, Roy P, Chatterjee S, Kaplan DW, & Basu B. (2013). Patient health questionnaire-9 as an effective tool for screening of depression among Indian adolescents. The Journal of Adolescent Health: Official Publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine, 52(5), 546–551. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.09.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George C, Kumar V, & Girish N. (2020). Effectiveness of a group intervention led by lay health workers in reducing the incidence of postpartum depression in South India. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 47, 101864. 10.1016/j.ajp.2019.101864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haugh JA, Herbert K, Choi S, Petrides J, Vermeulen MW, & D’Onofrio J. (2019). Acceptability of the stepped care model of depression treatment in primary care patients and providers. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings, 26(4), 402–410. 10.1007/s10880-019-09599-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawk M, Nimgaonkar V, Bhatia T, Brar JS, Elbahaey WA, Egan JE, … Deshpande SN (2017). A ‘Grantathon’ model to mentor new investigators in mental health research. Health Research Policy and Systems, 15(1), 92. 10.1186/s12961-017-0254-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermens MLM, Muntingh A, Franx G, van Splunteren PT, & Nuyen J. (2014). Stepped care for depression is easy to recommend, but harder to implement: Results of an explorative study within primary care in The Netherlands. BMC Family Practice, 15, 5. 10.1186/1471-2296-15-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones A. (2019). Help seeking in the perinatal period: A review of barriers and facilitators. Social Work in Public Health, 34(7), 596–605. 10.1080/19371918.2019.1635947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lund C, Schneider M, Garman EC, Davies T, Munodawafa M, Honikman S, … Susser E. (2020). Task-sharing of psychological treatment for antenatal depression in Khayelitsha, South Africa: Effects on antenatal and postnatal outcomes in an individual randomised controlled trial. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 130, 103466. 10.1016/j.brat.2019.103466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcus SM, & Heringhausen JE (2009). Depression in childbearing women: When depression complicates pregnancy. Primary Care, 36(1), 151–165, ix. 10.1016/j.pop.2008.10.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mavalankar D, & K V. (2010). The Changing Role of Auxiliary Nurse Midwife (ANM) in India: Implications for Maternal and Child Health (MCH). Esocialsciences.Com, Working Papers. [Google Scholar]

- National Mental Health Survey of India, 2015–16. (2016). Retrieved August from http://indianmhs.nimhans.ac.in/Docs/Report2.pdf

- Patel V, Rodrigues M, & DeSouza N. (2002). Gender, poverty, and postnatal depression: A study of mothers in Goa, India. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 159(1), 43–47. 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.1.43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Priya A, Chaturvedi S, Bhasin SK, Bhatia MS, & Radhakrishnan G. (2019). Are pregnant women also vulnerable to domestic violence? A community based enquiry for prevalence and predictors of domestic violence among pregnant women. Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care, 8(5), 1575–1579. 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_115_19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ransing R, Deshpande SN, Shete SR, Patil I, Kukreti P, Raghuveer P, … Bantwal P. (2020). Assessing antenatal depression in primary care with the PHQ-2 and PHQ-9: Can it be carried out by auxiliary nurse midwife (ANM)? Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 53, 102109. 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ransing R, Kukreti P, Deshpande S, Godake S, Neelam N, Raghuveer P, … Padma K. (2020). Perinatal depression-knowledge gap among service providers and service utilizers in India. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 47, 101822. 10.1016/j.ajp.2019.10.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ransing RS, Agrawal G, Bagul K, & Pevekar K. (2020). Inequity in distribution of psychiatry trainee seats and institutes across Indian states: A critical analysis. Journal of Neurosciences in Rural Practice, 11(2), 299–308. 10.1055/s-0040-1709973 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy P, Philpot B, Ford D, & Dunbar JA (2010). Identification of depression in diabetes: The efficacy of PHQ-9 and HADS-D. The British Journal of General Practice: The Journal of the Royal College of General Practitioners, 60(575), e239–e245. 10.3399/bjgp10X502128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shidhaye R, Gangale S, & Patel V. (2016). Prevalence and treatment coverage for depression: A population-based survey in Vidarbha, India. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 51(7), 993–1003. 10.1007/s00127-016-1220-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sikander S, Ahmad I, Atif N, Zaidi A, Vanobberghen F, Weiss HA, … Rahman A. (2019). Delivering the thinking healthy Programme for perinatal depression through volunteer peers: A cluster randomised controlled trial in Pakistan. The Lancet Psychiatry, 6(2), 128–139. 10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30467-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stansert Katzen L, Tomlinson M, Christodoulou J, Laurenzi C, le Roux I, Baker V, … Rotheram Borus MJ (2020). Home visits by community health workers in rural South Africa have a limited, but important impact on maternal and child health in the first two years of life. BMC Health Services Research, 20(1), 594. 10.1186/s12913-020-05436-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephens S, Ford E, Paudyal P, & Smith H. (2016). Effectiveness of psychological interventions for postnatal depression in primary care: A meta-analysis. Annals of Family Medicine, 14(5), 463–472. 10.1370/afm.1967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swaminathan S., Hemalatha R., Pandey A., Kassebaum NJ., Laxmaiah A., Longvah T., … Dandona L. (2019). The burden of child and maternal malnutrition and trends in its indicators in the states of India: The global burden of disease study 1990–2017. The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health, 3(12), 855–870. 10.1016/S2352-4642(19)30273-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tandon R, Jain A, & Malhotra P. (2018). Management of iron deficiency anemia in pregnancy in India. Indian Journal of Hematology & Blood Transfusion: An Official Journal of Indian Society of Hematology and Blood Transfusion, 34(2), 204–215. 10.1007/s12288-018-0949-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tudosa R, Vartej P, Horhoianu I, Ghica C, Mateescu S, & Dumitrache I. (2010). Maternal and fetal complications of the hypothyroidism-related pregnancy. Maedica, 5(2), 116–123. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Upadhyay RP, Chowdhury R, Salehi A, Sarkar K, Singh SK, Sinha B, … Kumar A. (2017). Postpartum depression in India: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 95(10), 706–717C. 10.2471/BLT.17.192237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO (2008). Mental health gap action programme. In In mhGAP: Mental Health Gap Action Programme: Scaling Up Care for Mental, Neurological and Substance Use Disorders, WHO headquarters, Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO. (2014). Implementation research toolkit. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/tdr/publications/year/2014/9789241506960_workbook_eng.pdf [Google Scholar]

- WHO. (2017). Scalable psychological interventions for people in communities affected by adversity. Retrieved from. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/254581/WHO-MSD-MER-17.1-eng.pdf; jsessionid=0EDF71ED3E69E589339AC715F1D65165?sequence=1

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.