Abstract

Evaporative light scattering detectors (ELSD) are commonly used with high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) to separate and quantify lipids, which are typically not easily detectable by more conventional methods such as UV-visible detectors. In many HPLC-ELSD methods to analyze lipids, a volatile buffer is included in the mobile phase to control the pH and facilitate separation between lipid species. Here, we report an unintended effect that buffer choice can have in HPLC-ELSD analysis of lipids – the identity and concentration of the buffer can substantially influence the resulting ELSD peak areas. To isolate this effect, we use a simple isocratic methanol mobile phase supplemented with different concentrations of commonly used buffers for ELSD analysis, and quantify the effect on peak width, peak shape, and peak area for seven different lipids (POPC, DOPE, cholesterol, sphingomyelin, DOTAP, DOPS, and lactose ceramide). We find that the ELSD peak areas for different lipids can change substantially depending on the mobile phase buffer composition, even in cases where the peak width and shape are unchanged. For a subset of analytes which are UV-active, we also demonstrate that the peak area quantified by UV remains unchanged under different buffer conditions, indicating that this effect is particular to ELSD quantification. We speculate that this ELSD-buffer effect may be the result of a variety of physical phenomenon, including: modification of aerosol droplet size, alteration of clustering of analytes during evaporation of the mobile phase, and mass-amplification or ion-pair effects, all of which could lead to differences in observed peak areas. Such effects would be expected to be molecule-specific, consistent with our data. We anticipate that this report will be useful for researchers designing and implementing HPLC-ELSD methods, especially of lipids.

Keywords: Evaporative light scattering detection (ELSD), High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), lipids

1. INTRODUCTION

Evaporative light scattering detectors (ELSD) are often employed for quantitative analysis of lipids separated by high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) (1–6), largely because most lipids do not contain strong UV-absorbing chromophores and so are not easily detectable by more common spectroscopic detectors (7, 8).

ELSD operates by the following generalized mechanism (8, 9): First, the HPLC column effluent is nebulized with a stream of inert gas. The resulting aerosol is funneled into a heated drift tube where the mobile phase is evaporated, leaving only dried particulate clusters of analyte. These clusters then pass through a light beam where scattering is detected by a photodiode or photomultiplier tube. The extent of scattering is related to the amount of analyte present, which can be quantified by comparison to a standard curve. Across small ranges of analyte concentration, ELSD response factors can be relatively linear (4), but typically ELSD produces a nonlinear response (8). As such, ELSD quantification is sensitive to peak widths and shapes, more so than spectroscopic detectors (8).

HPLC-ELSD methods to study lipids often include buffers in the mobile phase to stabilize pH and to facilitate preferred separation. However, given the sensitivity of ELSD to peak widths and shapes, inclusion of buffers in the mobile phase can have the unintended consequence of substantially altering the ELSD response for some analytes. Indeed, previous work has demonstrated that mobile phase additives such as silver nitrate or triethylamine-formic acid can be utilized to enhance the ELSD signal for some analytes through ELSD-specific mechanisms, including altering droplet size distribution during nebulization, mass-amplification of the dry particles by non-covalent adduct formation during evaporation, and modifying the dry particle size, shape, or residual solvent content (10, 11). Given this, choice of buffer could substantially alter the ELSD response for lipids even in cases where peak widths and shapes are unaltered.

Here, we characterize the effect of mobile phase buffer composition on the chromatographic quantification of lipids by HPLC-ELSD. Our aim is to highlight this often unexamined issue for those performing quantification of lipids by HPLC-ELSD. We examine the effect of buffer composition on the ELSD response of seven different lipids, spanning several lipid classes (sterols, glycerophospholipids, sphingolipids). To isolate the effect of buffer composition, we focus on simple isocratic methanol-based mobile phases supplemented with volatile buffers commonly used in ELSD analysis of lipids: ammonium formate (AF), ammonium acetate (AA), and trifluoroacetic acid (TFA). Only volatile buffers such as these are recommended for HPLC-ELSD methods to not produce overly noisy background signals or foul the ELSD drift tube (12). For those lipids which have appreciable UV chromophores, we also compare the effect of buffer additives on the ELSD vs. UV response.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Materials

Palmitoyl oleoyl phosphatidylcholine (POPC), dioleoylphosphatidylethanolamine (DOPE), 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho-L-serine (DOPS), 1,2-dioleoyl-3-trimethylammonium-propane (DOTAP), d18:1/18:0 C18 Lactosyl(ß) Ceramide (LAC), cholesterol, and egg sphingomyelin were obtained from Avanti Polar Lipids (Alabaster, AL). Astragaloside IV (AGIV) was obtained from the United States Pharmacopeial Convention (Rockville, MD). Other chemicals and solvents were obtained from Thermo Fisher (Waltham, MA) and Millipore Sigma (St. Louis, MO).

2.2. HPLC Mobile Phase

The HPLC mobile phase consisted of methanol with one of the following buffers: 1mM or 10 mM ammonium formate (AF), 1mM or 10 mM ammonium acetate (AA), 0.01% or 0.1% (v/v) trifluoracetic acid (TFA). Mobile phases were filtered by vacuum filtration with a 0.22 μm PVDF membrane (Durapore, Millipore Sigma). Buffer pH values were: 1 mM AF = pH 7.2, 10 mM AF = pH 7.1, 1 mM AA = pH 7.3, 10 mM AA = pH 7.6, 0.01% TFA = pH 4.8, 0.1% TFA = pH 1.4.

2.3. Preparation of lipid samples

Lipid stocks were stored in organic solvent (typically chloroform) at −20°C. To prepare samples for HPLC-ELSD analysis, an appropriate volume of lipid stock was transferred into a glass autosampler vial, dried under N2 gas, and then placed in a vacuum desiccator for 2–24 hours. The resulting lipid film was dissolved in methanol and autosampler caps were sealed with Teflon tape to prevent evaporation. Samples were prepared at the following concentrations: CH = 0.1 g/L, POPC = 0.16 g/L, DOPE = 0.16 g/L, DOPS 0.16 g/L, DOTAP = 0.16 g/L, SM = 0.16 g/L, LAC = 0.16 g/L, AR = 0.1 g/L, AGIV = 0.1 g/L. For many of the lipids, higher concentrations led to solubility problems, determined by visible aggregation or by inconsistent HPLC-ELSD results. Caffeine samples were prepared in 95:5 MeOH:H2O at 0.1 g/L.

2.4. HPLC-ELSD Instrumentation, Method, and Analysis

Samples were analyzed using an Agilent 1200 series HPLC with a 1260 ELSD, operated by ChemStation software (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA), and equipped with a reverse-phase Ultracarb™ ODS C18 column (150 × 4.6 mm, 3 μm) and guard column (UHPLC C18 4.6 mm ID from Phenomenex, Torrance, CA). An isocratic method was used, with the mobile phase consisting of methanol with one of several buffers, as indicated in each data set. HPLC flow rate = 0.5 mL/min, column temperature = 35°C. For lipid samples, ELSD settings were: drift tube temperature = 70°C, Gain = 10, N2 pressure = 3.5 bar. For caffeine samples, the ELSD drift tube temperature was 55°C; at higher temperatures caffeine became volatile, resulting in signal reduction. Week-to-week variation in ELSD peak areas for identical samples was 4–6% (standard deviation/mean). Unless otherwise indicated, ELSD baseline noise was <0.5 mV (standard deviation), indicating that the mobile phase and buffer were sufficiently volatile under the chosen ELSD conditions. For tandem UV-ELSD measurements, an Agilent 1100 series UV detector was used in-line preceding the ELSD detector. λ = 205 nm for lipids and 250 nm for caffeine. Data analysis was performed using ChemStation.

Injection volumes were 20–60 μL, depending on the concentration of the analyte. 9.6 μg of analyte was injected for DOPE, DOPS, DOTAP, SM, POPC, and LAC. 2 μg of analyte was injected for CHOL, Caffeine, AR, and AGIV.

3. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

To isolate the effects of the mobile phase buffer composition on the ELSD response, we conducted HPLC-ELSD analysis of isolated lipids using a simple reverse-phase isocratic method. The mobile phase consisted of methanol with one of several buffers commonly used for HPLC-ELSD: 1mM or 10 mM ammonium formate (AF), 1mM or 10 mM ammonium acetate (AA), 0.01 or 0.1% trifluoracetic acid (TFA). We chose lipid analytes from several major lipid classes: cholesterol (CHOL), POPC, DOPE, sphingomyelin (SM), DOPS, DOTAP, and C18 lactosyl(ß) ceramide (LAC). To illustrate that ELSD-buffer effects could occur for non-lipid analytes, we also analyzed caffeine, allura red (AR, a common food dye) and astragaloside IV (AGIV, a bioactive saponin used in traditional Chinese medicine (13)). In each case, identical samples of each analyte were run under different mobile phase buffer conditions.

We observed that different analytes exhibited different chromatographic sensitivities to buffer conditions, but there were similar trends among some analytes. Therefore, we chose to present the results in the following phenomenological groupings: Group 1) CHOL, LAC, caffeine, and AGIV were analytes for which the ELSD peak area changed under different buffer conditions, while the peak widths and peak shapes (measured by peak symmetry) remained largely unchanged. Group 2) DOPE, POPC, SM were analytes where changes in peak area occurred together with changes in peak widths and/or shapes, and some conditions yielded no measurable signal. Group 3) DOTAP, DOPS, and AR were examples of charged compounds responding to the different buffer conditions.

3.1. Group 1

3.1.1. Cholesterol (CHOL)

CHOL should not be charged under any of the buffer conditions, and as such, we observed that its peak width and shape was relatively insensitive to the mobile phase buffer composition (see example traces in Figure 1A and tabulation of peak widths, symmetries, etc. in Table S1). The relative peak area, however, was observed to vary by a factor of ~2 depending on the buffer condition (Figure 1B). Notably, increasing the concentration of AF increased the ELSD peak area, whereas increasing the concentration of AA moderately suppressed the peak area.

Figure 1. Variation in ELSD response to Group 1 analytes under different HPLC mobile phase buffer conditions.

A) shows example traces of cholesterol injections under different mobile phase buffer conditions. Although some peak fronting was observed in several low buffer concentration conditions (MeOH, 1mM AA, 0.01% TFA), little variation in peak width or peak shape was observed for most conditions. B-D) shows variation in relative peak areas for cholesterol (CHOL), lactosyl(ß) ceramide (LAC), and caffeine (CAF) quantified by ELSD under different mobile phase buffer conditions. Error bars are ± standard deviation of triplicate measurements. Peak areas are calculated relative to MeOH, indicated with a dashed line. Inset shows the chemical structure of each analyte. Cholesterol and caffeine injections contained 2 μg of analyte. LAC injections contained 9.6 μg. Mobile phase consisted of methanol with one of the buffers indicated; MeOH = methanol only, AF = ammonium formate, AA = ammonium acetate, TFA = trifluoroacetic acid. Tabulations of retention times, peak symmetries, and raw peak areas for each analyte are given in Tables S1–S3. * = all samples exhibited substantial baseline noise, and were not analyzed, as discussed in the main text.

3.1.2. C18 Lactosyl(ß) Ceramide (LAC)

LAC is a glycolipid, with a ceramide backbone and a lactose head group. Given its larger hydrophilic head group and lack of ionizable groups, its peak width and shape were insensitive to the buffer condition (Table S2), similar to CHOL. Unlike CHOL however, increasing concentrations of both AF and AA led to moderate suppression of the peak area (25–35%), and the highest response was observed with no buffer present (Figure 1C).

3.1.3. Caffeine (CAF) and Astragaloside IV (AGIV)

To illustrate that ELSD-buffer effects are not specific to lipids, we also examined caffeine and AGIV using the same range of buffer conditions. For caffeine, we observed that the peak width and shape remained relatively unchanged across most buffer conditions (Table S3), but the peak area varied ~3-fold with buffer identity and concentration (Figure 1D). We also note that caffeine samples in 0.1% TFA exhibited substantial baseline noise, and were not analyzed. This is likely due to the lower drift tube temperature required to analyze caffeine (55°C vs. 70°C for all other analytes), leading to insufficient volatilization of TFA. At higher temperatures, caffeine itself became volatile, resulting in loss of ELSD signal. On the other hand, compared to caffeine, AGIV exhibited comparatively modest change (~20%) in peak area (Figure S1 and Table S9). Together, this data highlights that buffer composition can alter ELSD peak areas for analytes other than lipids.

3.1.4. Mobile phase buffer composition does not influence UV peak areas for Group 1 analytes

Changes in peak area with different buffer compositions without an accompanying change in peak width or shape are indicative of an ELSD-specific phenomenon, as the results cannot be attributed to peak broadening, etc. To illustrate this, we performed tandem HPLC-UV-ELSD analysis for CHOL, LAC, and CAF, which have an appreciable UV absorption coefficient unlike most of the analytes we studied. We focused on a subset of the buffer conditions which showed large changes in ELSD signal, and compared the ELSD and UV peak areas (Figure 2). Importantly, we note that while UV absorption can be solvent dependent, changes in UV peak areas under our tested conditions (identical solvent and only small buffer concentrations, ≤ 10 mM), are expected to be minor. Indeed, we observed that while the ELSD peak areas varied considerably between different buffer conditions (Figure 2A, C, E), the UV peak areas exhibited comparatively little variation (Figure 2B, D, F), indicating that the buffer effects were specific to the ELSD detection.

Figure 2. Comparison in variation between ELSD and UV relative peak areas for caffeine (A and B), lactosyl(ß) ceramide (C and D), and cholesterol (E and F) under different HPLC mobile phase buffer conditions.

While substantial variation is observed in ELSD peak areas between the different buffer conditions, comparatively little variation is observed in the UV peak areas. Buffer conditions selected for this analysis were those for which substantial variation in ELSD peak areas was observed. Error bars are ± standard deviation of triplicate measurements. Peak areas are calculated relative to MeOH, indicated with a dashed line. Cholesterol and caffeine injections contained 2 μg of analyte. LAC injections contained 9.6 μg. Mobile phase consisted of methanol supplemented with one of the buffers indicated; MeOH = methanol only, AF = ammonium formate, AA = ammonium acetate.

3.2. Group 2

3.2.1. DOPE

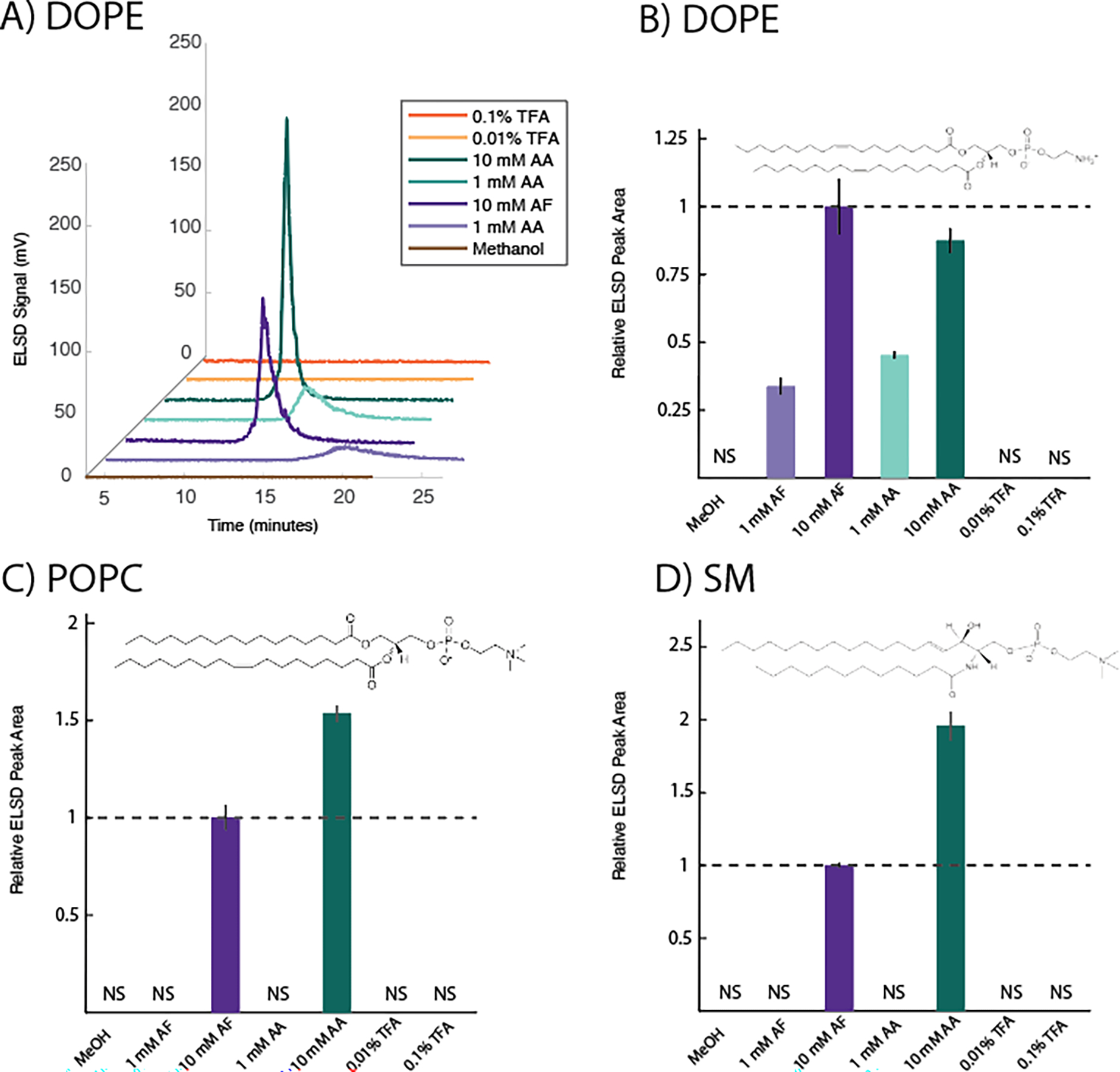

DOPE is a common phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) phospholipid and is zwittterionic at neutral pH (14). In general, lower concentrations of buffer led to longer retention times and considerable peak broadening (Figure 3A and Table S4). Due (at least in part) to the peak broadening effect, ELSD peak areas were very dependent on buffer concentration, with peak areas differing ~3 fold between 1 mM and 10 mM buffer conditions (Figure 3B). Without buffer, or with TFA, no reliable peak could be detected.

Figure 3. Variation in ELSD response to Group 2 lipids under different HPLC mobile phase buffer conditions.

A) shows example traces of DOPE injections under different mobile phase buffer conditions. Increasing concentrations of AA and AF buffers led to sharper and more symmetrical peaks. No peak was observed without buffer or with TFA. B-D) shows variation in relative peak areas for DOPE, POPC, and sphingomyelin (SM) quantified by ELSD under different mobile phase buffer conditions. NS = no signal (no quantifiable peak above baseline was observed). Error bars are ± standard deviation of triplicate measurements. Peak areas are calculated relative to 10 mM AF, indicated with a dashed line. Inset shows the chemical structure of each analyte. All injections contained 9.6 μg of analyte. Mobile phase consisted of methanol supplemented with one of the buffers indicated; MeOH = methanol only, AF = ammonium formate, AA = ammonium acetate, TFA = trifluoroacetic acid. Tabulations of retention times, peak symmetries, and raw peak areas for each analyte are given in Tables S4–S6.

3.2.2. POPC

POPC is often used as the prototypical phosphatidylcholine (PC) lipid, and is zwitterionic at neutral pH (14). It exhibited a rather broad, tailed peak for the buffer conditions under which it could be detected (Table S5). Under most buffer conditions, no quantifiable peak was observed (Figure 3C), suggesting that enough peak broadening and/or delay in retention time occurred to lower the signal near baseline levels, as appeared to be the case for DOPE. Only with 10 mM AA or AF could ELSD peak areas be quantified.

3.2.3. Sphingomyelin (SM)

SM consists of a sphingolipid with a PC head group (15), and is zwitterionic at neutral pH. Notably, SM exhibited very similar sensitivities as POPC, likely because of their identical head group. Similar to POPC, SM exhibited a broad, tailed peak, and under many buffer conditions, no reliable peak could be detected (Table S6). Only with 10 mM AA or AF could ELSD peak areas be quantified (Figure 3D).

3.3. Group 3

3.3.1. DOTAP

At neutral pH, DOTAP is a positively charged, double-tailed lipid, commonly used as a cationic surfactant, and for DNA or RNA transfection (16). It generally eluted early with a sharp peak, with some variation in peak width and shape depending on the buffer condition (Table S7). Increasing concentration of all buffers led to larger peak areas (Figure 4A), but 0.1% TFA yielded a very large signal enhancement, likely due to the ion-pair effect (see Section 3.4 below).

Figure 4. Variation in ELSD response to Group 3 lipids under different HPLC mobile phase buffer conditions.

A-B) show variation in relative peak areas for DOTAP and DOPS quantified by ELSD under different mobile phase buffer conditions. NS = no signal (no quantifiable peak above baseline was observed). Multiple, irregular peaks were observed for DOPS under AA and AF buffer conditions, indicative of sample decay induced by the buffer. Therefore, those conditions were not quantified in the analysis. Error bars are ± standard deviation of triplicate measurements. Peak areas are calculated relative to the buffer condition with the lowest signal, indicated with a dashed line. Inset shows the chemical structure of each analyte. All injections contained 9.6 μg of analyte. Mobile phase consisted of methanol supplemented with one of the buffers indicated; MeOH = methanol only, AF = ammonium formate, AA = ammonium acetate, TFA = trifluoroacetic acid. Tabulations of retention times, peak symmetries, and raw peak areas for each analyte are given in Tables S7–S8.

3.3.2. DOPS

Phosphatidylserine (PS) lipids such as DOPS are negatively charged at neutral pH (14). No signal was observed for the methanol only or 0.01% TFA buffer conditions; but quantifiable peaks were observed for higher concentrations of TFA, possibly due to the ion-pair effect, although much weaker than for DOTAP. Given the multiple ionizable functional groups on DOPS, the observed peaks were sharp and eluted early (Table S8). Interestingly, and unlike any of the other analytes studied, multiple irregular peaks were observed for the AA and AF buffer conditions for DOPS, suggestive of sample degradation in those buffers.

3.3.3. Allura Red AC (AR)

As an example of a charged non-lipid compound, we also analyzed AR. As with the other Group 3 analytes, it exhibited sharp peaks with comparatively little change in width or shape (Table S10), but dramatic changes (>20 fold) in peak area with buffer condition (Figure S2). Perhaps due to a suppressive ion effect, the peak areas observed in TFA were quite low.

3.4. Mechanistic Considerations

What are the underlying physical causes of the different ELSD-buffer effects? It likely depends on the particular effect being observed. For cases where changes in peak area correlated with changes in peak width or shape (e.g. many cases in Group 2), a likely cause is the nonlinear nature of the ELSD response to analyte concentration, reviewed previously (8). For example, as a peak broadens, the concentration of analyte across the peak decreases as the amount of analyte is spread over a larger time window. Due to the nonlinear response, the integrated peak area will be lower than if the same amount of analyte were concentrated in a sharper peak. An example of this appears to occur in the DOPE data, comparing the 1 mM and 10 mM AF and AA buffer conditions (see Figure 3A–B). Additionally, with enough broadening, no quantifiable peak would be observed, and this may explain the lack of signal observed with many buffer conditions for Group 2 analytes.

However, in the cases where peak widths, shapes, and/or UV peak areas remain unchanged with the buffer condition (e.g. many cases in Group 1, and some in Group 3), clearly other mechanisms are at work. We can separate these into 2 categories: mechanisms which enhance the ELSD response, and those which suppress it. One possible enhancement mechanism is the mass-amplification effect, wherein mobile phase additives form non-covalent adducts or ion pairs with the analyte during evaporation, increasing the mass and size of the resulting dry particle and enhancing the ELSD response (10, 11, 17). In our data, this may be a contributing factor for buffers which enhance the ELSD response above the methanol only condition (e.g. 10 mM AF for cholesterol and DOTAP, and TFA conditions for DOTAP and DOPS, see Figures 1B, 4A–B). On the other hand, there are a variety of possible suppressive mechanisms, including alteration of particle sizes, shapes, or densities without a mass-amplification effect, alteration of the residual solvent content in the “dry” particles, and altering the distribution of droplet sizes during nebulization (8). It is not the aim of this short communication to determine the detailed mechanism for each lipid-buffer combination, and indeed many of the mechanisms are not mutually exclusive, and so multiple may be at work in some cases. However we raise these effects as important points to consider when developing HPLC-ELSD methodologies.

4. CONCLUSION

Here, we reported the effects of 3 common mobile phase buffer additives on the ELSD response to 7 lipid species, representing several major lipid classes. We observed that different buffer conditions affected the ELSD peak areas of the lipids differently, enhancing some and suppressing others, some with corresponding changes in peak shapes or widths, and some without. The best all-around buffer under the conditions we studied was 10 mM AF, which permitted quantification of most lipids studied, although it was not the optimum buffer for many. Taken together, our results underscore the need of researchers analyzing lipids by HPLC-ELSD to optimize the buffer conditions for their particular application and to pay special attention to the role that the buffer may play not only in separation, but also in quantification by ELSD.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank Dr. Nathan Cook (Williams College) for instrument support. RJR acknowledges financial support from Williams College and NIH grant R15AI171754.

Footnotes

COMPETING INTERESTS DECLARATION

The authors declare no competing interests.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Olivia Graceffa: Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Visualization, Writing - Review & Editing; Eunice Kim: Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Visualization, Writing - Review & Editing; Rachel Broweleit: Investigation, Formal analysis, Visualization, Writing - Review & Editing; Robert Rawle: Conceptualization, Methodology, Resources, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing Original Draft

REFERENCES

- 1.Melis S, Foubert I, and Delcour JA 2021. Normal-Phase HPLC-ELSD to Compare Lipid Profiles of Different Wheat Flours. Foods. 10:428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Varache M, Ciancone M, and Couffin A-C 2019. Development and validation of a novel UPLC-ELSD method for the assessment of lipid composition of nanomedicine formulation. Int. J. Pharm. 566:11–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kothalawala N, Mudalige TK, Sisco P, and Linder SW 2018. Novel analytical methods to assess the chemical and physical properties of liposomes. J. Chromatogr. B. 1091:14–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roces C, Kastner E, Stone P, Lowry D, and Perrie Y 2016. Rapid Quantification and Validation of Lipid Concentrations within Liposomes. Pharmaceutics. 8:29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Simonzadeh N 2009. An isocratic HPLC method for the simultaneous determination of cholesterol, cardiolipin, and DOPC in lyophilized lipids and liposomal formulations. J. Chromatogr. Sci. 47:304–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Khoury S, Canlet C, Lacroix M, Berdeaux O, Jouhet J, and Bertrand-Michel J 2018. Quantification of Lipids: Model, Reality, and Compromise. Biomolecules. 8:174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hopia AI, and Ollilainen V-M 1993. Comparison of the Evaporative Light Scattering Detector (ELSD) and Refractive Index Detector (RID) in Lipid Analysis. J. Liq. Chromatogr. 16:2469–2482. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Megoulas NC, and Koupparis MA 2005. Twenty Years of Evaporative Light Scattering Detection. Crit. Rev. Anal. Chem. 35:301–316. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Webster GK, Jensen JS, and Diaz AR 2004. An investigation into detector limitations using evaporative light-scattering detectors for pharmaceutical applications. J. Chromatogr. Sci. 42:484–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Allen LB, Koropchak JA, and Szostek Bogdan. 1995. Condensation Nucleation Light Scattering Detection for Conventional Reversed-Phase Liquid Chromatography. Anal. Chem. 67:659–666. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Deschamps FS, Gaudin K, Lesellier E, Tchapla A, Ferrier D, Baillel A, and Chaminade P 2001. Response enhancement for the evaporative light scattering detection for the analysis of lipid classes and molecular species. Chromatographia. 54:607–611. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Young C, and Dolan JW 2003. Success with evaporative light-scattering detection. LCGC Eur. 21:120–128. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li W, and Fitzloff JF 2001. Determination of Astragaloside IV in Radix Astragali (Astragalus membranaceus var. monghulicus) Using High-Performance Liquid Chromatography with Evaporative Light-Scattering Detection. J. Chromatogr. Sci. 39:459–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van Meer G, Voelker DR, and Feigenson GW 2008. Membrane lipids: where they are and how they behave. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 9:112–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Christie WW Sphingomyelin and Related Sphingophospholipids. AOCS Lipid Libr. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Simberg D, Weisman S, Talmon Y, and Barenholz Y 2004. DOTAP (and other cationic lipids): chemistry, biophysics, and transfection. Crit. Rev. Ther. Drug Carrier Syst. 21:257–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Megoulas NC, and Koupparis MA 2004. Enhancement of evaporative light scattering detection in high-performance liquid chromatographic determination of neomycin based on highly volatile mobile phase, high-molecular-mass ion-pairing reagents and controlled peak shape. J. Chromatogr. A. 1057:125–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.