Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic has had deep influence on American life. However, the burden of the pandemic has not been distributed equally among members of a population based on their demographic features. The purpose of this study was to investigate whether sex, age, race, and religion were associated with COVID-19 positivity rates in Boone County, Missouri over a 22-month period (March 15, 2020 to December 2, 2021) of the pandemic. We analyzed the data using age distribution histograms, two-way delta tables, and trend analysis graphs to highlight our study findings. We evaluated those graphs with each demographic feature across a collection of defined epochs of key events, such as vaccine release, Delta variant, vaccine boosters, and initial Omicron variant. Our results supported the hypothesis that males and minority races such as Black or African Americans and All-Other are more likely to have a higher COVID-19 positivity rate across our defined epochs.

Introduction

The coronavirus disease (COVID-19) is an infectious disease caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus [1]. Since the COVID-19’s emergence in Wuhan, China in December 2019, it has rapidly spread worldwide. The disease was declared a pandemic on March 11, 2020 by the World Health Organization (WHO) [2]. While many patients recover without the need for any hospitalization or specialized care, COVID-19 is known to severely impact the elderly and those with chronic illnesses and co-morbidities such as diabetes, obesity, and hypertension [2]. By April 1, 2020, COVID-19 had infected more than 800,000 people and caused over 40,000 deaths in 205 countries and territories [3]; and more recently it has infected more than 614 million people and taken more than 6.5 million lives worldwide [4]. COVID-19 has deeply affected the United States, China, and Europe [3][5][6]. The coronavirus pandemic has also caused enormous economic, public health, and social damages [4][6][7]. We should draw our attention that the risk factors of COVID-19 are still under investigation, but some demographic factors, such as age, gender, sex, race/ethnicity, marital status, and religion could be a reason for increasing both the testing and positivity rates within a population. These rates significantly vary among different demographic features between the period before the release of the vaccine (before November 2020) and the period after the release of the vaccine (after November 2020). It is worth noting that evidence of social inequalities related to COVID-19 is already emerging in UK, Spain and USA [8][9]. According to the Spanish government, the rate of COVID-19 infection is six or seven times higher in the most deprived areas compared to the least deprived regions [8]. Similarly in the USA, it has been found that the positive test results with dramatically increased risk of death in New York city and Illinois were observed among residents with the most disadvantaged counties [8][10]. Wales and England have also found that people who are Asian, Black, and minority ethnic accounted for 34.5% of the 4873 critical COVID-19 cases [8][11].

The emergence and persistence of COVID-19 in the United States after the death of more than half a million Americans has undoubtedly affected and altered American life [3][12][13]. Since COVID-19 is an airborne and infectious disease, it has been advertised by mainstream media and news channels as “a great equalizer” where social standing has no effect on vulnerability [12]. However, data shows that vulnerability to COVID-19 is not identical across American society, but reflects stark racial differences [12]. Disproportionate rates of infection and death from COVID-19 within communities of different races/ethnicities have laid bare the tragic consequences of pervasive and systemic inequities in living, medical care, working, and environmental conditions [14]. For example, in the capital city of the United States, Washington D.C., African Americans represent approximately 46% of the population but make up 75% of COVID-19 deaths [12]. Also, the history of inner cities has left Black Americans with fewer economic and educational opportunities than their White counterparts and has exposed them to social risks associated with more severe negative effects [8][15]. Those risks could increase the probability of getting affected by population health diseases such as COVID-19 [8][15]. We should note that COVID-19 has had a significant impact on ethnic minority and racial populations in the United States [16], but the role of economic inequities and geographic differences in these discrepancies have not been adequately studied [16]. Previous studies have shown that non-white race, male sex, older age and a preferred language other than English were associated with higher infection rates for COVID-19 [17]. Among those infected, individual race, sex, and age were associated with increased likelihood of hospitalization [17]. As of September 1st, 2022, there had been more than 612 million confirmed cases globally, including more than 6.5 million deaths. The United States is the leading country with more than 95 million confirmed cases and more than 1.05 million deaths [18]. In November of 2020 many pharmaceutical companies announced that the results of the vaccine trials showed high efficacy for the majority of the trial individuals [19]. This discovery started a new era of the pandemic which lasted until our present time [19][20]. The coronavirus pandemic has caused a huge number of challenges to the global public health system as well as the global economy since its emergence until now [20]. Additionally, the economic crisis initiated by the COVID-19 pandemic was unprecedented in its scale [20]. According to the U.S. Department of Labor, the unemployment rate reached 14.7% in April 2020, and the total value of exports of all the 50 states decreased by 29.8%, from $414.95 billion in the second quarter of 2019 to $291.47 billion in the second quarter of 2020 [20]. The unemployment rate also declined to 10.2% in July 2020 [20].

In the United States, COVID-19 has had a significant impact on ethnic/racial minorities, and excessively affected underserved groups, especially Native American, Latin American, and African American [16][21], with economic, environmental, geographic, political, and social discrepancies that predate the pandemic. In this study, we describe potential factors that contribute to the COVID-19 differences in Boone County, Missouri from March 2020 until December 2021 from both social determinants and demographic feature perspectives. For example, in June 2020, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported that 33.8% of COVID-19 cases in the United States were Latin Americans, and 21.8% were African Americans. These groups comprise only 13% and 18% of the US population, respectively [21]. In December 2021, our study showed that 0.274% of COVID-19 cases in Boone County, Missouri were Hispanics, and 14.23% were Black or African Americans. In our study, we analyzed the associations of COVID-19 testing and positivity rates with demographic features such as age, religion, race, and sex, for patients in Boone County, Missouri. We have divided our study analysis into five study epochs which affected the positivity rates for the individuals in Boone County, Missouri. The first and second study epochs are the periods before and after the release of vaccines in November 2020. The third study epoch is before and after the appearance of the Delta variant in June 2021. The fourth study epoch is before and after the vaccine booster shot (September 2021). Finally, the fifth and last study epoch is before and after the appearance of the Omicron variant (late November 2021). We hypothesized that minority race, male sex, and any kind of religious faith (Theist) are associated with higher COVID-19 positivity rates. We also hypothesized that minority race, male sex, and any kind of religious faith (Theist) have higher positivity rates before and after the vaccine release and before and after the vaccine boosters. On the other hand, minority race, male sex, and any kind of religious faith (Theist) will have higher positivity rates during the Delta and the Omicron variants epochs.

Methods

Localized COVID-19 Test Data: Boone County, Missouri consists of 11 primary cities and towns: Columbia, Ashland, Centralia, Hallsville, Harrisburg, Sturgeon, Hartsburg, Rocheport, McBaine, Huntsdale, and Pierpont. Boone County is part of the Mid-Missouri geographic region within the Midwestern U.S. and is home to 180,463 residents (see www.como.gov/coronavirus/) Based on data from the 2019 U.S. Census Bureau, most of the Boone County population identify as non-Hispanic White (79%), followed by Black or African American 9%, with all other races making up the remaining 12%. The county has 93,841 females (52%) and 86,622 males (48%), per censusreporter.org/. The percentage of the population that affiliates with any religion is 39.4%, and 60.6% of the Boone County population are not religious, per www.factsbycity.com. We used data from the Cerner Electronic Health Record (EHR) from the University of Missouri Hospital and Clinics in the Mid-Missouri area on individuals who were tested for COVID-19 between March 2020 and December 2021. The data includes the demographic information for 236,809 patients. We combined the races and ethnicities of Other, Some-Other-Race, Unknown, Unable-to-Acquire, Refused or Declined, Hispanic, Asian, Native Hawaiian, and American Indian (i.e., all except “non-Hispanic White” and “non-Hispanic Black or African American” into one category called “All Other”. As shown in table 1, White counted for 76.4%, Black or African American counted for 14.23%, where “All Other” races added up to 9.37%. The “All Other” consists of the following categories: Some Other Race was combined with Other and added up to 4.5%, Asian added up to 2.3%, Refused or Declined and Unable to Acquire were combined with Unanswered and added up to 2.05%, Hispanic added up to 0.274%, American Indian added up to 0.143% and Native Hawaiian added up to 0.087%. It was statistically more informative to combine all the smaller categories into one bigger category of “All Other”. We combined all religious identifications in the population sample (Lutheran, Baptist, Catholic, Methodist, Latter Day Saints, Protestant, Amish, Episcopalian, Disciples of Christ, Presbyterian, Church of Christ, Pentecostal, Assembly of God, United Church of Christ, Nazarene, Community of Christ, Church of God, Christian Science, Salvation Army, Adventist, Mennonite, Yahweh, Mormon, Unitarian/Universalist, Jehovah’s Witness, Islam, Bahai, Jewish, Hindu, Christian, Muslim, and Other) into one category called “Theist”, and combined “None” with “Atheist”. For all these features (race/ethnicity, marital status and religion), we combined all “Unknown” missing values, nan, or Null into one category called “Unanswered”.

Table 1:

Two-way table (race vs. sex) showing the race analysis of the COVID-19 positive individuals in Boone County, Missouri.

| Race: No. (%) |

White | Black or African | Other | Asian | No Answer | Hispanic | American Indian | Native Hawaiian | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cohort Size: No. (%) | 12,261 (76.4) | 2,284 (14.23) | 722 (4.5) | 370 (2.3) | 330 (2.055) | 44 (0.274) | 23 (0.143) | 14 (0.087) | 16,049 (100) |

| Sex: No. (%) | |||||||||

| Female | 6,633 (41.33) | 1,291 (8.04) | 343 (2.13) | 201 (1.25) | 131 (0.815) | 25 (0.156) | 12 (0.075) | 6 (0.037) | 8,643 (53.85) |

| Male | 5,628 (35.07) | 993 (6.19) | 379 (2.37) | 169 (1.05) | 199 (1.24) | 19 (0.118) | 11 (0.068) | 8 (0.05) | 7,406 (46.15) |

Boone County’s COVID-19 Positivity Rates by Demographic Features: We calculated the positivity rate of COVID-19 by using the following equation: PR(X) = P (X)/TT (X) 100 and where PR(X) is the positive rate for a (sub-)population X, TP (X) is the positive cases, TT (X) is the total tested. The total number of tested individuals from Boone County was 148,328. The total number of individuals with positive tests was 15,903, which gives a 10.72% positivity rate in the testing population. The first demographic feature studied before and after the vaccine release was sex. The total number of tested females in Boone County was 86,175 (58.1%), and the number of males was 62,153 (41.9%). The total number of females who tested positive was 8,595 (54.05%), 4,550 (54.1%) before the vaccine release and 4,045 (54%) after the vaccine release. The total number of males who tested positive was 7,308 (45.95%), 3,861 (45.9%) before the vaccine release, and 3,447 (46%) after the vaccine release. The second demographic feature studied before and after the vaccine release was race/ethnicity. The total number of tested White individuals was 116,200 (78.33%), 19,981 (13.47%) Black or African Americans, and 12,147 (8.2%) were All Other Races. The total number of White individuals who tested positive was 12,261 (77.1%), 6,637 (78.9%) before the vaccine release and 5,624 (75.07%) after the vaccine release. The total number of Black or African Americans who tested positive was 2,284 (14.36%), 1,097 (13.05%) before the vaccine release, and 1,187 (15.84%) after the vaccine release. The total number of All Other Race individuals who tested positive were 1,358 (8.54%), 677 (8.05%) before the vaccine release, and 681 (9.09%) after the vaccine release. The third demographic feature studied before and after the vaccine release was religion. The total number of tested Theist individuals was 60,900 (41.05%), 65,227 (43.98%) Atheist, and 22,201 (14.97%) was Unanswered. The total number of Theist individuals who tested positive was 6,213 (39.07%), 3,364 (40%) before the vaccine release and 2,849 (38.03%) after the vaccine release. The total number of Atheist who tested positive was 6,764 (42.53%), 3,496 (41.56%) before the vaccine release, and 3,268 (43.62%) after the vaccine release. The total number of Unanswered individuals who tested positive was 2,926 (18.4%), 1,551 (18.44%) before the vaccine release, and 1,375 (18.35%) after the vaccine release.

Statistical Exploration: The descriptive statistics for the age of the tested individuals is as follows, mean of 34.42, standard deviation (STD) of 20.48, minimum of 0, 25% percentile of 20, 50% percentile (median) of 31, 75% percentile of 49, and maximum of 104. To test our hypothesis, we first conducted a Chi-Square test (X2) to find any positive or negative association between COVID-19 results and sex, race, or religion, which is calculated using the following equation: X2 = ∑(Oi Ei)2/Ei, where X2 is the Chi-Square, Oi is the observed value and Ei is the expected value. The degrees of freedom for the X2 are calculated using the following formula df = (r 1)(c 1), where r is the number of rows and c is the number of columns. A two sided alpha level of 0.05 was used to determine statistical significance in all hypothesis tests. The X2 test results is written using the following formula: X2(df = degrees of freedom, N = sample size) = Chi-Square statistic value, p = p-value. The sample size is equal to 74,769 which is the total number of the tested individuals in Boone County. We only counted one positive test for each individual to avoid inflating population PR. First, a X2 Test of Independence was performed to assess the relationship between COVID-19 and sex. There was a significant relationship between the two variables as shown in the following X2 test result: X2 (1, 74769) = 14.45, p = .0001436. Second, a X2 Test of Independence was performed to assess the relationship between COVID-19 and race. There was a significant relationship between the two variables as shown in the X2 test result below: X2 (2, 74769) = 20.18, p = .00004158. Third and lastly, a X2 Test of Independence was performed to assess the relationship between COVID-19 and religion. There was no significant relationship between the two variables as shown in the following X2 test result: X2 (2, 74769) = 1.19, p = .5512.

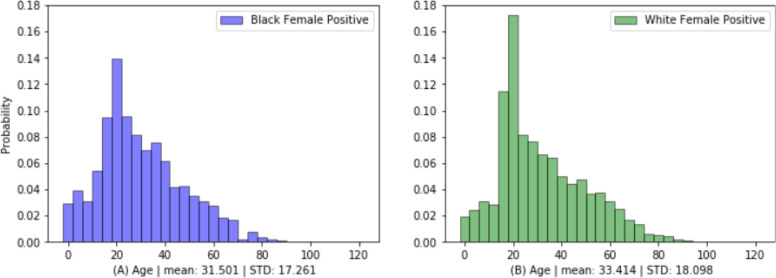

Figure 1 probability mass function (PMF), i.e., histogram normalized to area 1.0, for the age distribution by sex (graph A) for Black or African American females showing that younger (ages 16-44) individuals were testing positive for COVID more than older individuals, (graph B) for White females showing that younger (ages 16-32) were testing positive for COVID more than older individuals. The mean age for the Black or African American females is 31.5 while the mean age for the White females is 33.4. The standard deviation (STD) for the Black or African American females is 17.2, whereas the standard deviation (STD) for the White females is 18.1. Both histograms clearly show that Black or African American females are likely to test COVID positive more than the White females. Black or African American females tend to test COVID positive at higher rate than the White females especially in the ages of 0-12 and between 28-44.

Figure 1:

Histogram for the Age Distribution by Sex (graph A on the left) for Black or African American females showing that younger (ages 16-44) individuals were testing positive for COVID more than older individuals, (graph B on the right) for White females showing that younger (ages 16-32) were testing positive for COVID more than older individuals. Both histograms clearly show that Black or African American females are more likely to test COVID positive than the White females.

Results

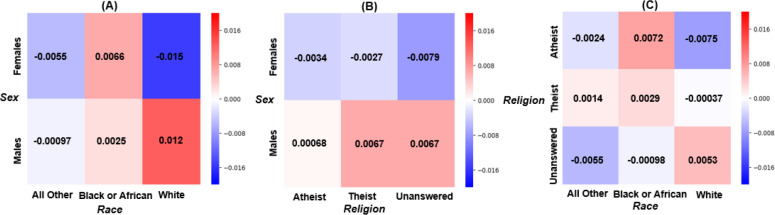

Bivariate Analysis: Heatmaps were computed from two-way delta tables to highlight our study findings. The “red” color represents a higher possibility of testing positive for COVID (higher delta percentage values), and the “blue” color represents a lower possibility of testing positive for COVID (lower delta percentage values). Numbers were computed by calculating the difference of the percentage as deltas between the individuals who tested positive and the entire tested individuals (positive tested minus all tested). Those tables were computed to study the association between the demographic features of sex, race/ethnicity, and religion for the tested individuals and their positivity rates. Figure 2.A represents a two-way delta table for sex and race, showing a large disparity between White females versus White males, with males (red square, 0.012) significantly more likely to test COVID positive than their female (blue square, -0.015) counterparts. On the other hand, Black or African American females are more likely to test positive for COVID comparing to Black or African American males. Also, the All-Other races/ethnicities males are more likely to test positive for COVID than All-Other races/ethnicities females.

Figure 2:

Two-way Delta Tables for (A) Sex and Race, showing a large disparity between White females versus White males, with males significantly more likely to test COVID positive than their female counterparts, (B) Sex and Religion, showing Theist and Unanswered males more likely to test COVID positive than their female counterparts, (C) Religion and Race, showing a large disparity between White Atheist versus Black or African American Atheist, with Black or African American Atheist significantly more likely to test COVID positive than their White counterparts.

Figure 2.B represents a two-way delta table for sex and religion, showing that patients who affiliated with a religious belief (Theist) and Unanswered males (both red squares, 0.0067) were more likely to test COVID positive than their female (blue squares, -0.0027 and -0.0079, respectively) counterparts. In addition, the Atheist females are less likely to test positive for COVID comparing to the Atheist males. The Unanswered females are the least likely to test positive for COVID, whereas Unanswered and Theist males are the most likely to test positive for COVID. Figure 2.C represents a two-way delta table for religion and race, showing a large disparity between White Atheists versus Black or African American Atheists, with Black or African American Atheists (red square, 0.0072) significantly more likely to test COVID positive than their White (blue square, -0.0075) counterparts. Also, Black or African American Theists are more likely to test positive for COVID compared to White Theists, but the White Unanswered are more likely to test positive than the Black or African American Unanswered. Additionally, it clearly shows that Atheists of All-Other race/ethnicity (light blue square, -0.0024) were more likely to test COVID positive than to White, Atheists (dark blue square, -0.0075). Also, Black or African American Atheists (red square, 0.0072) were more likely to test COVID positive than White Atheists (dark blue square, -0.0075).

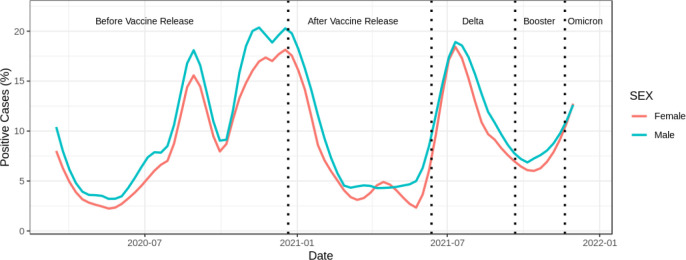

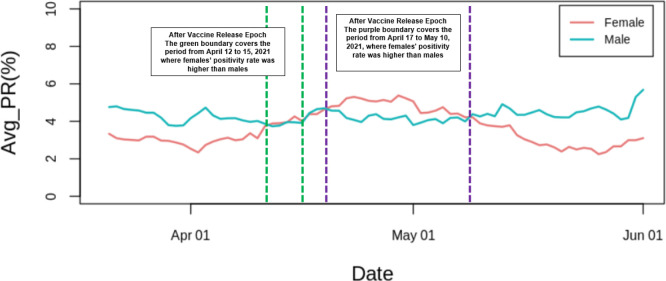

Time trend analysis for the tested individuals by sex: Figure 3 shows the time trend for the tested individuals by sex, (M)ale and (F)emale in Boone County from March 15, 2020 to December 2, 2021. In the time series plots, we computed the locally estimated scatterplot smoothing (LOESS) to refine the daily fluctuations in positive cases. In Figure 3 we can see a major decrease in late December 2020 and early January 2021 for PR(M) and PR(F) after the release of the vaccine. It is worth mentioning that females only had a higher PR than males in the mid epoch of after the vaccine release around end of April and beginning of May 2021. The PR for both sexes started to increase again in June 2021 due to the appearance of the Delta variant. Males had a higher PR than females during the Delta variant crisis. Figure 3 also shows a significant decrease in the positivity rate for both sexes in September 2021 due to the vaccine boosters. We see lower PR(F) than PR(M) during the vaccine boosters. Finally, they started to increase again in late November 2021 because of the first recorded case of the Omicron variant, where males seemed to have higher PR than females during this epoch. The results in Figure 3 supported our hypothesis that the male sex is associated with higher PR before and after vaccine release, Delta variant, vaccine boosters, and Omicron variant. Figure 4 shows the significant change for females compared to males over a 21-day moving average during the after vaccine release epoch (between April 01, 2021 and June 01, 2021). Figure 4 shows a more detailed view of the after vaccine release epoch. We can notice a slightly increase in the PR for females between April 12, 2021 and April 15, 2021 (green boundary). We can clearly see the increase in the PR for females from April 17, 2021 until May 10, 2021 (purple boundary).

Figure 3:

Time trend analysis for the PR by sex for the tested individuals in Boone County. It shows a disparity between males and females, with males associated with higher PR than their female counterparts. Females only had a higher PR than males in the middle of the After Vaccine Release epoch around end of April and early May 2021.

Figure 4:

After Vaccine Release Epoch focus on 21-day moving average by sex between the period of April 01, 2021 and June 01, 2021. It shows higher PR(F) than PR(M) from April 12, 2021 until April 15, 2021 (green boundary). It also shows significantly higher PR(F) than PR(M) from April 17, 2021 until May 10, 2021 (purple boundary).

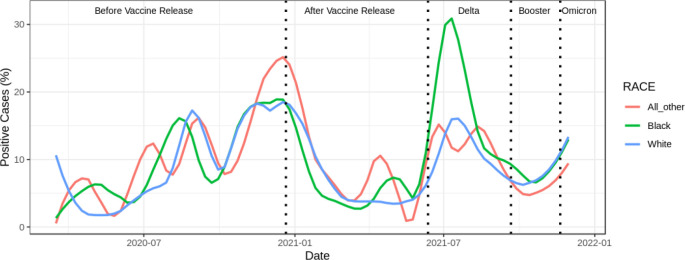

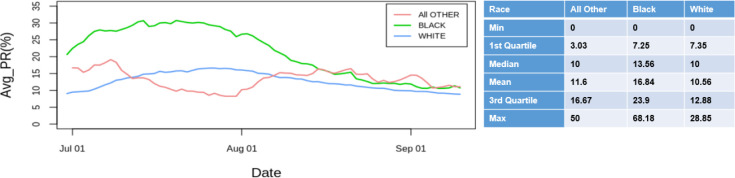

Time trend analysis for the tested individuals by race: Figure 5 shows the time trend for PR by race from March 15, 2020 to December 2, 2021. Figure 5 clearly shows a major decrease in the PR in late December 2020 and early January 2021 for the three races after the release of the vaccine. The All Other continue to have a higher PR than White individuals and Black or African Americans after the vaccine release. Before the vaccine release, Black or African Americans and All Other had a higher PR than White individuals. The period between November 10, 2020 and January 15, 2021 had a significant changes for the three races. The All Other showed a very high peak compared to White and Black or African Americans. The PR for the three races started to increase again in June 2021 due to the appearance of the Delta variant. Black or African American faced a drastic increase in the PR during the Delta variant epoch compared to White and All Other individuals especially between June 10, 2021 and October 11, 2021. We should also note that there are no data anomalies or spikes but the COVID-19 positivity level is just significantly higher. The Black or African Americans shows the highest local maximum (highest peak) in mid July 2021. On the other hand, All Other shows the lowest local minimum during the Delta epoch. Figure 5 also shows a significant decrease in the PR for the three races in September 2021 due to the booster (third vaccine shot) roll-out. Additionally, White and All Other Race faced lower PR than Black or African Americans during the vaccine boosters. Finally, the PR started to increase again in late November 2021 because of the first recorded case of the Omicron variant. All Other Race seemed to have a lower PR than the other two races. The results in Figure 5 support our hypothesis that minority race is associated with higher PR before and after vaccine release, Delta variant, booster shot, and Omicron variant. Figure 6 shows the significant change for Black or African American compared to All Other over a 21-day moving average during the Delta epoch (between June 2021 and September 2021). Figure 6 shows a more detailed view of the Delta epoch. Black or African Americans had a much higher average PR especially in mid and late July 2021, whereas All Other had a much lower average PR for this epoch. It also shows the significant difference in the descriptive statistics for Black or African Americans compared to White and All Other over the 3-week moving average during the Delta epoch. The Black or African American has the highest PR mean at 16.84 compared to 11.6 for All Other and 10.56 for White from mid July 2021 until early August 2021. Additionally, Black or African American has the highest PR median at 13.56 compared to 10 for All Other and White from mid July 2021 until beginning of August 2021.

Figure 5:

Time trend analysis for the PR by race for the tested individuals in Boone County. The All Other had a higher PR in December 22, 2020 than White and Black or African Americans. In Mid April 2021, All Other had much higher PR than White and Black or African Americans before it decreased drastically towards the end of June 2021. In Mid July 2021, Black or African Americans had a much higher PR compared to White and All Other.

Figure 6:

Delta Epoch focus on 21-day moving average by race (graph on the left) between the period of July 10, 2021 and September 10, 2021. It shows significantly higher PR for Black or African Americans than All Other. The descriptive statistics table on the right shows a higher PR mean at 16.84 for Black or African American compared to 11.6 for All Other and 10.56 for White during this epoch.

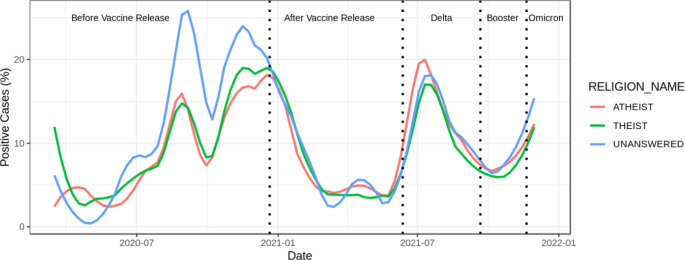

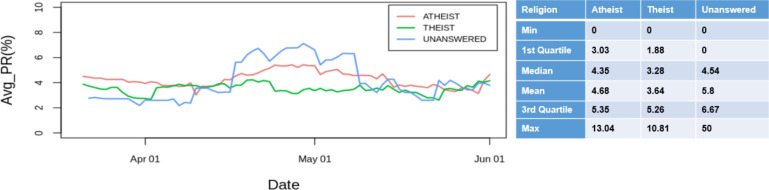

Time trend analysis for the tested individuals by religion: Figure 7 shows the time trend for PR by religion from March 15, 2020 to December 2, 2021. There were significant changes within the three religious indicators between July 05, 2020 and January 10, 2021. In Figure 7 we can notice a significant decrease in the number of PR in late December 2020 and early January 2021 for the three religious indicators after the release of the vaccine. The decrease is almost similar throughout the three religious indicators with a slight favor for the “Unanswered”. It is also important to note that Unanswered had a higher PR before the vaccine release period than Theist and Atheist. The number of the PR for the three religious indicators began to increase again in June 2021 due to the appearance of the Delta variant. The three religious indicators faced a very similar amount of increase in the PR during the Delta variant crisis with Atheist slightly higher followed by Unanswered then Theist. Figure 7 shows a significant decrease in the PR for the three religious indicators in September 2021 due to the booster shot (third vaccine shot) roll-out. Additionally, the three religious indicators faced almost the same level of the lower PR during the vaccine boosters. Finally, the PR started to increase again in late November 2021 because of the first recorded case of Omicron variant. The three religious indicators started to increase in the same manner with a faster growing to the Unanswered. Finally, there is not enough evidence to support the hypothesis that individuals who affiliate with any religious belief (Theist) are more likely to have a higher PR before and after the vaccine release, during Delta and Omicron variants crisis and before and after the booster shot compared to the Atheist and Unanswered. Figure 8 shows the significant change for Unanswered and Atheist compared to Theist over a 21-day moving average during the after vaccine release epoch (between April 2021 and June 2021). Figure 8 shows a more detailed view of the after vaccine release epoch. Unanswered and Atheist had a slightly higher average PR from April 15, 2021 until May 10, 2021 than Theist. It shows the difference in the descriptive statistics for Unanswered and Atheist compared to Theist over the 3-week moving average during the after vaccine release epoch. The Unanswered has slightly higher PR mean at 5.8 followed by Atheist at 4.68 compared to 3.64 for Theist from mid April 2021 until early May 2021. Additionally, Unanswered has slightly higher PR median at 4.54 followed by Atheist at 4.35 compared to 3.28 for Theist from April 15, 2021 until May 15, 2021.

Figure 7:

Trend analysis for PR by religion for the tested individuals in Boone County. The graph shows a significant increase in the PR for the Unanswered in September and November 2020 compared to Theist and Atheist. Also, Unanswered and Atheist show a slightly higher PR from mid April 2021 until early May, 2021 than Theist.

Figure 8:

After Vaccine Release Epoch focus on 21-day moving average by religion (graph on the left) between the period of April 15, 2021 and May 10, 2021. It shows slightly higher PR for Unanswered and Atheist than Theist. The descriptive statistics table on the right shows a higher PR mean at 5.8 for Unanswered and 4.68 for Atheist compared to 3.64 for Theist during this epoch.

Discussion

The results of the histograms and the two-way delta tables support our hypothesis that males are more likely to test positive for COVID than females. The heatmaps show that Black or African Americans Atheist are more likely to test COVID positive comparing to their White counterparts. Also, Black or African Americans Theist are more likely to test COVID positive than White Theist. These significant findings support our hypothesis that minority races (Black or African Americans and All-Other) were more associated with higher PR than White. Finally, there is not enough evidence to support the hypothesis that patients who affiliate with any religious belief (Theist) are more likely to test positive for COVID compared to the Atheist. The time series plots support our hypothesis that male sex and minor races such as Black or African Americans and All Other have higher PR than female sex and White. The time series plot by sex clearly shows that males have higher PR than females except mid, end of April and beginning of May of the after vaccine release epoch. The time series plot by race shows that Black or African Americans have a significantly higher PR than White especially during the Delta variant epoch. Lastly, the time series plot by religion did not show any significant difference between the three religious indicators. It only shows a slightly higher PR for Unanswered and Atheist compared to Theist in the 3-week moving average between mid April and early May 2021 in the after vaccine release epoch. In summary, there is not enough evidence to support the hypothesis that Theists are more likely to have a higher PR than Atheist and Unanswered.

There are several limitations in our study. First of all, the tests have known to have the possibility of false positives and false negatives. Second, we do not have the information about the individuals who did not test in Boone County or tested at some other clinics and facilities other than the University of Missouri hospital and clinics. Third, we do not have the information about the vaccine, vaccine boosters, as well as the first Delta and Omicron recorded cases dates at other hospitals, facilities, clinics and vendors other than the University of Missouri hospital and clinics. Fourth, the “none” in the religion was represented at a high percentage in the tested data that could be errors entered by nurses, or patients who refused to say their religious beliefs. Fifth and most importantly, we do not have vaccination status information for individual study participants.

Conclusion

As COVID is an ongoing source of threat, there will definitely be a continuous need for research studies and analyses to understand its behavior and to monitor the demographic and equitable distribution of life saving resources for fighting the virus. From a demographic perspective, our study shows that males are more likely to test positive for COVID and they are more likely to test positive than females. In addition, males have higher PR than females in our tested population. It also shows that minority races such as Black or African American, and All-Other are more likely to test positive for COVID than White. There was no evidence that religion was associated with the PR in our study population. Our findings support the hypotheses that males and minority races are more likely to have a higher PR during the vaccine period, Delta and Omicron variants as well as the vaccine boosters period in Boone County. However, more resources should be allocated to the most vulnerable sex, race, and religion to address the COVID pandemic in an equitable manner. Therefore, our team is conducting additional studies that will include geospatial analysis based on the zip code addresses and census blocks/tracts of the tested individuals in Boone County to study and define the associations and other features that could be related to the testing, positivity and death rates for COVID.

Acknowledgments

This research is approved by the University of Missouri Institutional Review Board (IRB), project number 2075502.

Figures & Table

References

- 1.Liang D, Shi L, Zhao J, Liu P, Sarnat JA, Gao S, et al. Urban air pollution may enhance COVID-19 case-fatality and mortality rates in the United States. The Innovation. 2020;1(3):100047. doi: 10.1016/j.xinn.2020.100047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tirupathi R, Muradova V, Shekhar R, Salim SA, Al-Tawfiq JA, Palabindala V. COVID-19 disparity among racial and ethnic minorities in the US: a cross sectional analysis. Travel medicine and infectious disease. 2020;38:101904. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2020.101904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kobia F, Gitaka J. COVID-19: Are Africa’s diagnostic challenges blunting response effectiveness? AAS open research. 2020;3 doi: 10.12688/aasopenres.13061.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wu X, Nethery RC, Sabath M, Braun D, Dominici F. Air pollution and COVID-19 mortality in the United States: Strengths and limitations of an ecological regression analysis. Science advances. 2020;6(45):eabd4049. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abd4049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bagchi B, Chatterjee S, Ghosh R, Dandapat D. Coronavirus Outbreak and the Great Lockdown. Springer; 2020. Impact of COVID-19 on global economy; pp. 15–26. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Atalan A. Is the lockdown important to prevent the COVID-19 pandemic? Effects on psychology, environment and economy-perspective. Annals of medicine and surgery. 2020;56:38–42. doi: 10.1016/j.amsu.2020.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zohner YE, Morris JS. COVID-TRACK: world and USA SARS-COV-2 testing and COVID-19 tracking. BioData Mining. 2021;14(1):1–15. doi: 10.1186/s13040-021-00233-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bambra C, Riordan R, Ford J, Matthews F. The COVID-19 pandemic and health inequalities. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2020;74(11):964–8. doi: 10.1136/jech-2020-214401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boserup B, McKenney M, Elkbuli A. Disproportionate impact of COVID-19 pandemic on racial and ethnic minorities. The American Surgeon. 2020;86(12):1615–22. doi: 10.1177/0003134820973356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Louis-Jean J, Cenat K, Njoku CV, Angelo J, Sanon D. Coronavirus (COVID-19) and racial disparities: a perspective analysis. Journal of racial and ethnic health disparities. 2020;7(6):1039–45. doi: 10.1007/s40615-020-00879-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abuelgasim E, Saw LJ, Shirke M, Zeinah M, Harky A. COVID-19: Unique public health issues facing Black, Asian and minority ethnic communities. Current Problems in Cardiology. 2020;45(8):100621. doi: 10.1016/j.cpcardiol.2020.100621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brown KM, Lewis JY, Davis SK. An ecological study of the association between neighborhood racial and economic residential segregation with COVID-19 vulnerability in the United States’ capital city. Annals of Epidemiology. 2021;59:33–6. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2021.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bilal U, Tabb LP, Barber S, Diez Roux AV. Spatial inequities in COVID-19 testing, positivity, confirmed cases, and mortality in 3 US cities: an ecological study. Annals of internal medicine. 2021;174(7):936–44. doi: 10.7326/M20-3936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Strully KW, Harrison TM, Pardo TA, Carleo-Evangelist J. Strategies to address COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and mitigate health disparities in minority populations. Frontiers in Public Health. 2021;9:645268. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.645268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Egede LE, Walker RJ. Structural racism, social risk factors, and Covid-19—a dangerous convergence for Black Americans. New England Journal of Medicine. 2020;383(12):e77. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2023616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lewis NM, Friedrichs M, Wagstaff S, Sage K, LaCross N, Bui D, et al. Disparities in COVID-19 incidence, hospitalizations, and testing, by area-level deprivation—Utah, March 3–July 9, 2020. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2020;69(38):1369. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6938a4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cromer SJ, Lakhani CM, Wexler DJ, Burnett-Bowie SAM, Udler M, Patel CJ. Geospatial analysis of individual and community-level socioeconomic factors impacting SARS-CoV-2 prevalence and outcomes. Medrxiv. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hu T, Yue H, Wang C, She B, Ye X, Liu R, et al. Racial segregation, testing site access, and COVID-19 incidence rate in Massachusetts, USA. International journal of environmental research and public health. 2020;17(24):9528. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17249528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Khubchandani J, Sharma S, Price JH, Wiblishauser MJ, Sharma M, Webb FJ. COVID-19 vaccination hesitancy in the United States: a rapid national assessment. Journal of Community Health. 2021;46(2):270–7. doi: 10.1007/s10900-020-00958-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen J, Zhang P. Clustering US States by Time Series of COVID-19 New Case Counts in the Early Months with Non-Negative Matrix Factorization. Journal of Data Science. 2022;20(1):79–94. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tai DBG, Shah A, Doubeni CA, Sia IG, Wieland ML. The disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on racial and ethnic minorities in the United States. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2021;72(4):703–6. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]