Abstract

What happens during adolescence emerges from early in life and sets the stage for later in life. This linking function of adolescence within the life course is grounded in social, psychological, and biological development and is fundamental to the intergenerational transmission of societal inequalities. This article explores this life course phenomenon by focusing on how the social ups and downs of secondary school shape adolescents’ educational trajectories, translating their backgrounds into their futures through the interplay of their personal agency with the constraints imposed by the stratified institutions they navigate. Illustrative examples include gender differences in risky behavior, racialized experiences of school discipline, immigrant youths’ family relations, LGBTQ students’ school safety, STEM education, adverse childhood experiences, and mindset interventions.

“We tell ourselves stories in order to live…We look for the sermon in the suicide, for the social or moral lesson in the murder of five. We interpret what we see, select the most workable of the multiple choices. We live entirely, especially if we are writers, by the imposition of a narrative line upon disparate images, by the ‘ideas’ with which we have learned to freeze the shifting phantasmagoria which is our actual experience.”

These oft-quoted words by novelist Joan Didion (1979) capture for me the reality that we—as humans—are compelled to extricate patterns and distill narratives from what seems like chaos because that is the only way that we can keep going. We do that as people, but we also do that as social and behavioral scientists. In our work, we are driven to explain some developmental phenomenon because that explanation imposes order on a world that is filled with disorder. How exactly do we come to that explanation? We look for the strongest pattern and then tell a story about it. The story should be empirically based, of course, but effective research is often research that compels and convinces with the narrative it builds on the data.

The research that I have conducted on adolescence has several threads that can be woven together into a larger tapestry. From statistical analyses, interviews, ethnographic observations, and experiments focused on adolescents that I have conducted and from the words, writings, and creative expressions of the adolescents I have worked with has emerged a story about the interplay of adolescents’ social development and academic progress with three basic parts:

Adolescents struggle through a complex and stratified educational system that doubles as a vast social world governed by peer norms that are often opaque, frequently contradictory, and constantly evolving.

Adolescents strive for success in this educational and social system while dealing with its psychological challenges in ways that can seem rationally self-protective at first but have the potential to eventually lead them astray, turning around on themselves so that academic and social success achieved becomes more difficult to translate into success maintained.

Such adolescent experiences offer a story to understand adolescence as a critical stage of life and to see the implications of the growing diversity of the adolescent population in ways that might result in more guidance and support for adolescents and the adults trying to support and protect them from such “growing pains”.

Linking adolescents’ social development and academic progress, this story highlights the stormier side of adolescent life, the pressures of schooling, and the widening of inequality. As such, it runs the risk of reifying the darker narrative of adolescence that has long held sway among adults and that, incidentally, I and many other scholars of adolescence have tried to counter. Yet, it is still an important story to consider because it is relevant to many adolescents and their schools and because it offers a valuable window into the ways that adolescence bridges childhood to adulthood. It just needs to be delivered with the reinforcement that positive youth development is generally the norm rather than the exception, resilience is real and achievable, and even some of the riskier and rockier aspects of adolescence often serve a developmental purpose (National Academies, 2019; Lerner, 2017; Beale-Spencer et al., 2006).

In describing this storyline in the larger discourse about adolescent development, this article—while admittedly not exhaustive and too western-based—draws on a long tradition of multidisciplinary research, including in life course sociology and developmental psychology, that has increasingly documented and interrogated the variability in adolescents’ experiences across diverse settings and groups1. Emphasizing the classic and the new, its goal is to explain why this story about the ways that adolescents manage their sometimes competing and sometimes synergistic roles as students and peers matters, where we can take it, and what we can do with it.

ADOLESCENCE IN LIFE COURSE PERSPECTIVE

If theory provides the underlying story structure for research, then life course theory can structure research on the interplay of adolescents’ social and academic lives. Broadly, life course theory focuses on the intersection of individual developmental pathways with larger social structures across time in ways that allow us to ask new questions and then systematically answer them (Elder, Shanahan, & Jennings, 2015; Elder, Johnson, & Crosnoe, 2003; for a thorough integration of life course theory with the larger family of relational developmental systems theories, see Lerner, Lewin-Bizan, & Warren, 2010).

This perspective has five principles to guide such a process (see Table 1), but two of those principles are particularly important for elucidating novel insights into the adolescent experience (Crosnoe & Johnson, 2011; Johnson, Crosnoe, & Elder, 2011). First, the principle of lifelong development emphasizes that lives are lived the long way. As such, adolescence should be viewed—and studied—as one brief passage in a much longer journey. Thus, the meaningfulness of adolescence lies at least in part in how it emerges from childhood and sets the stage for adulthood but also how adolescence stands out from what comes before and what comes after. We can make better sense of adolescence, therefore, by embedding it within the full course of life. Second, the principle of agency and constraints is about the ways that people try to make their own lives and take charge of their own fortunes even as they are being acted on by outside forces attempting to bound them in and/or push them in certain directions. This principle is all about the environment, the person, and the complicated dance between two.

TABLE 1.

Principles of Life Course Theory

| Principle | Description |

|---|---|

| Life span development | Human development is a lifelong process. |

| Agency & Constraints | Individuals construct their own lives through the choices and actions they take within the opportunities and constraints of history and social circumstance. |

| Time & Place | The life course of individuals is embedded and shaped by the historical times and places they experience over their lifetime. |

| Timing | The developmental antecedents and consequences of life transitions, events, and behavioral patterns vary according to their timing in a person’s life. |

| Linked Lives | Lives are lived interdependently and socio-historical influences are expressed through this network of shared relationships. |

Putting these two principles of life course theory into conversation with each other can illuminate the uniqueness of adolescence as a critical period of the life course and, more specifically, reveal why the interplay of social and academic journeys across adolescence is important to study, understand, and address. To that end, we can derive a guiding story by iteratively considering adolescence on its own, as flowing out of and into other periods of life, and as the product of the interplay of agency and constraints.

ADOLESCENCE ON ITS OWN

To begin, adolescence warrants attention on its own, regardless of what comes earlier or later. Over the course of my career studying adolescence at the intersection of sociology, psychology, and educational science, I have been motivated by two objectives. The first is exploring the social side of secondary school in a modern world that is both socially connected and socially fractured, and the second is understanding what that social side of secondary school means for educational attainment in a global economy that has maximized the lifelong financial, social, political, and health returns of higher education. The multi-year mixed-methods research I did for my 2011 book Fitting In, Standing Out: Navigating the Social Challenges of High School to Get an Education—which combined statistical analyses of population data on U.S. adolescents with ethnographic research in a large, diverse, public U.S. high school—perhaps best encapsulates how these objectives came together.

Like many social and behavioral scientists who set out to study the social side of secondary school, I was influenced by James Coleman’s 1961 book, The Adolescent Society: The Social Life of the Teenager and its Impact on Society. Studying a set of Midwestern high schools in the 1950s, Coleman crafted a story about an almost uniform youth culture in U.S. schools in which adolescents created their own system of norms and values in opposition to conventional adult standards and then enforced conformity to that system. In the ensuing decades, this story has been problematized and complicated in many ways, especially by efforts to better recognize the diverse voices and experiences of young people living in circumstances and traversing schools far removed from the affluent, White, suburban schools that Coleman studied (Carter, 2006; Flores-Gonzalez, 2005; Steinberg, Brown, & Dornbusch, 1997; Way, 2014).

Yet, the vision of secondary school as a highly structured social hierarchy going well beyond academic processes is a clear one that still holds weight. This hierarchy, however, is neither fixed nor uniform, and adolescents have to learn how to “work” that hierarchy to get ahead or, more importantly, not fall behind academically or socially. Depending on which schools adolescents attend, the community and country that shapes the structure of their schooling, and who they are as individuals, this nature of secondary schooling can create seemingly perverse incentives that are sometimes in line with the notion of an oppositional culture but also many times (and in most domains) are not. Of the many developmental domains in which such incentives play out, three are particularly illustrative. They concern risk-taking, sexual activity, and relationships with parents and other adults.

Risky Behavior as Strategy

Risk-taking is a hallmark of adolescence. In varying degrees, adolescents engage in risky and otherwise problem behaviors that adults wish they would avoid. We, as adults, see such behaviors as bad for adolescents, although they often are developmentally appropriate and help to support the transition into adulthood (Duell & Steinberg, 2021). For their part, adolescents may see such behaviors in terms of social status, or related to their position in peer hierarchies at school—how liked they are, how much they are respected or envied. As such, behaviors become social currency and, therefore, potentially good for them.

For example, Allen and colleagues (2005) conducted a study indicating that popularity in U.S. high schools encouraged low-level delinquency and drug use. Adolescents saw moderate engagement in such potentially dangerous behaviors as a source of status but more serious engagement as a source of stigma. Thus, gaining or maintaining popularity may require being a little bad but not too bad. These findings echoed my own research described in Fitting In, Standing Out, which suggested that academic success need not be the death knell for popularity that is often depicted in movies and television. In fact, popular kids tended to do well in school; they just did not do too well—perhaps A− and B+ grades rather than A+ but not a C or lower. Such an orientation toward risky behavior and academic progress allowed them to avoid disappointing the adults in their lives—as perfectly fine students—but not completely satisfy those adults either, as they occasionally got in worrisome trouble. This behavioral calculation of status is about wanting to be liked but also about avoiding being disliked (Pál, Stadtfeld, Grow, & Takács, 2016), wanting to belong but also wanting power or respect (Flores-Gonzalez, 2005; Gordon, Crosnoe, & Wang, 2013), and about the friends who surround an adolescent but also the friends that an adolescents’ friends have and the friends that an adolescent aspires to attract (Frank et al., 2008).

Contrary to common adult views of adolescents, therefore, ample evidence suggests that they are often hyper-rational about their social and academic lives. Through a combination of social processes (e.g., the consequences of individuating from parents) and biological processes (e.g., the development of the brain from back to front, rapid hormone production), they are highly oriented toward peer approval, and peer approval sometimes promotes risky behavior (Eckert, 1989; Monahan, Steinberg, & Cauffman, 2009; Steinberg, 2008). Yet, adolescents engage in such behavior in more thoughtful and planful ways than they are generally given credit for by adults. This tendency toward confounding but explainable behavioral decision-making is on display in the growing literature on bullying and peer victimization, which suggests that bullying is less a psychopathology and more an adaptive and goal-directed behavior. For example, research by Faris and Felmlee (2011) showed that adolescent bullying was most often perpetrated in the middle of a school’s social hierarchy (as an adolescent enacted strategies to climb the social ladder) than at the top (as an adolescent had nowhere else to climb) or at the bottom (as an adolescent saw no viable way to climb). Ellis, Volk, Gonzalez, and Embry (2016) used this refined understanding of bullying to redirect interventions targeting peer victimization in schools. Instead of changing the goal of bullying (i.e., gaining status and resources), the intervention offered alternative mechanisms for achieving that goal (e.g., jobs), with demonstration results pointing to a reduction in key outcomes such as school fights.

This body of research suggests that adults can identify paths of action to reduce risky behavior by getting inside the minds of adolescents and seeing a problem from their perspective.

Sexual Activity and Social Status

This delicate interplay between risky behavior and social status in secondary school does not work for all adolescents. That variability is evident in the growing literature on adolescent sexual behavior that pays special attention to the complexities of gender and race/ethnicity.

Ample quantitative and qualitative evidence suggests that sexual activity in adolescence is generally associated with popularity, which is a key marker of status in a social context like the school. As one example, an article by Helms et al. (2014) reported the interesting finding that, although adolescents in popular peer crowds did not necessarily engage in more sexual activity than other adolescents, their fellow students thought that they did. Yet, other evidence demonstrates that that the status of sexual activity in adolescence is not straightforward for girls. As research by Kreager and colleagues has shown (2009, Kreager, Staff, Gauthier, Lefkowitz, & Feinberg, 2016), the sexual double standard is alive and well in U.S. secondary schools, with girls not gaining a status boost and instead generally receiving a status penalty as they increased their sexual activity.

With such costs of sexual activity in the social context of school, what are adolescent girls’ reasons for engaging in sex? There is of course girls’ sexual desire, a subject too infrequently studied by adolescent scholars to the detriment of theoretical understanding (Harden, 2014; Tolman & McClelland, 2011). There is also the role of associations with older peers, both male and female. Such peer associations, in turn, reflect both biological and social mechanisms related to early puberty, which remains a popular topic for scholars of adolescence (Harden, 2014). Expanding on the role of peers and social influence, there is also the broader conceptualization of social context captured by sexualization, which refers to cultural and media-driven messages encouraging adolescent girls to assess their own social and personal worth in terms of their sexual attractiveness (McKenney & Bigler, 2016).

Research by Brown has helped to underscore the significance of sexualization in the social lives of adolescent girls. It has shown how sexualization and associated behaviors (such as sexual harassment and peer victimization) can organize high school networks in the United States but also more broadly how it is ingrained in social media. Notably, this social media component does not just involve sexualization directed from outside in but also how girls actively curate their own social media presence through self-sexualization. This social and self-sexualization then has implications not only for adolescent girls’ sexual behavior but also for their academic progress. Indeed, it appears to discourages girls’ academic investment and their academic self-presentation; again, achieving academically but striving to appear to others that she is not or that it is not intentional (Brown, 2021; Jewell, Brown, & Perry, 2015; Salomon & Brown, 2019). The complicating wrinkle to this gender story, though, is that Black girls tend to be sexualized more intensely, sexualized at younger ages, and subjected to more sexual harassment (Epstein, Blake, & González, 2017). This adultification is a developmental component of systematic racial/ethnic and gender stratification; how such inequality is lived in daily life.

Thus, adolescent girls often follow seemingly rational decision-making processes about their sexual behavior—whether said behavior is risky or not—to position themselves in a status hierarchy in key social contexts. They do so, however, on an uneven playing field that privileges some and marginalizes others through an overlay of interpersonal judgment that can change how they see themselves and their futures.

Family Bonds that Give and Take

The ecological perspective encourages the study of the adolescent world of secondary school as connected to the larger adult world, including how it is shaped by adult actors like parents and teachers. A clear through-line of developmental research is that strong bonds with adults are hallmarks of adjustment and positive functioning and that this developmental support in part reflects the ability of adults to guide adolescents into more positive peer environments and then protect against the deleterious effects of negative peer environments. This pattern is particularly evident in studies of communities of color and especially immigrant cultures, which tend to show adolescents as more family oriented, more connected to their extended families and community networks, more respectful of adult authority, and readier to believe that adults have their best interests at heart (Zeiders, Updegraff, Umaña-Taylor, McHale, & Padilla, 2016). In such communities, strong family connections and extended family networks are both cultural and functional, valued traditions that provide personal meaning but also help family members survive and thrive in a stratified society that imposes social and economic barriers on them. Adolescents growing up in such communities internalize these norms and values, which shapes how they move through the world, including their peer worlds and the educational system.

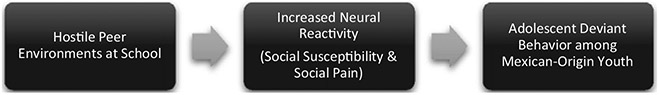

One population that I have studied—Mexican-origin youth—illustrates this pattern. For example, a study in the special issue of this journal on developmental neuroscience showed that close family bonds weakened the pathway from hostile peer environments at school to increased neural reactivity reflecting social susceptibility and social pain and onto the problem behavior of Mexican-origin adolescents (Figure 1). This finding indicates that adolescents do not experience schools’ social dynamics in a vacuum beyond the protection of their families (Schriber et al., 2018). Other studies complicate this pattern. As an example, quantitative findings revealed that feelings of obligation that arose from family bonds narrowed the scope of options Mexican-origin adolescents considered in planning their futures, including higher education (Desmond & López Turley, 2009). As another example, qualitative research revealed that the influence of well-meaning teachers on Mexican-origin adolescents could be socioemotionally protective but educationally restrictive. In counterfeit social capital, teachers simultaneously held positive views of Mexican-origin youth as “good” adolescents and biased views of them as “poor” students, which encouraged the teachers to provide social support and care to students but discouraged them from adequately scaffolding students’ ambitions and aspirations (Ream, 2003).

FIGURE 1.

Neural pathways linking peer environments to behavior. Adapted from: Schriber et al., 2018

In sum, Mexican-origin adolescents and other youth from communities of color—particularly immigrant communities—often enjoy a true source of adult-provided protection as they traverse the unique nature of adolescence unfolding within the social worlds of their schools, but there may be costs to that protection that counters at least some of its benefits. Youth from more historically advantaged segments of the population may face fewer risks and barriers as they traverse adolescence, diluting the potential value of the immediate protections of family but also clearing their paths overall. In this way, this literature on a specific population reveals the larger phenomenon by which adults both give and take in the lives of adolescents.

Lessons about Adolescent Society

With this picture of adolescent social life and educational disparities in mind, we cannot argue that adolescent society is monolithically oppositional. Instead, it is internally contradictory and context-specific, an individually tailored maze. Adolescents chart their own path through that society in ways that serve their own interests, sometimes with help from others, sometimes with extra challenges, and sometimes with a mixture of the two. For many, this journey is in line with positive youth development. For others, it more closely resembles the common—if exaggerated—storm and stress view of adolescence. Adolescents’ navigation of the inevitable perils they face on this journey is clearly a factor in which direction they go. The effort and thought that such navigation requires should inspire respect. Future research in this area needs to bridge social network techniques with more biopsychosocial approaches in longitudinal designs that allow for more densely repeated data collections that track the ups and downs of going to school and how these ups and downs are experienced internally and externally.

ADOLESCENCE THE LONG WAY

Having first considered adolescence on its own, we can approach adolescence within the larger life course. The driving idea of “the long way” is that adolescence is either a pit stop on the highway of life or, more likely, the major connector on this highway.

Adolescence Emerging from Childhood

Adolescence can play out the long way by flowing out of childhood. There are many aspects of childhood that affect how young people transition into and through adolescence. To choose one example, adverse childhood experiences (ACES) refer to potentially traumatic events or circumstances early in the life course—such as family disruption, maltreatment, or community violence—that have downstream consequences for development. Multiple studies link an array of ACES to such short- and long-term outcomes as maladjustment, behavioral and academic challenges, and poor health. They usually focus on stress as the focal mechanism; for instance, frequent exposure to parent’s verbal abuse can over-activate stress response in ways that eventually deteriorate physical health. Notably, the rigid stratification of many societies means that youth of color tend to be exposed to more ACES—including experiences of discrimination—and have fewer resources that can buffer against their developmental impact (Duke, Pettingell, McMorris, & Borowsky, 2010; Felitti et al., 1998; Flaherty et al., 2013).

Focusing on adolescents, McLaughlin and Sheridan (2016) formulated an alternative learning perspective. In this conceptualization (Figure 2), some ACES are threats (e.g., witnessing violence, physical abuse). Sustained exposure to threats can facilitate a fear learning process in which youth see nearly every experience as potentially dangerous, whether it is actually threatening or relatively safe. For example, children who suffer frequent discrimination may become hypervigilant adolescents who encounter even trustworthy adults with suspicion. Other ACES are deprivation (e.g., poverty, parental neglect). Sustained exposure to deprivation can trigger a rewards learning process in which young people cannot distinguish between high- and low-reward situations. For example, children who do not have their basic needs met may become adolescents who cannot discern when the benefits of a new experience likely outweigh its risks. Young people with ACES then move through the educational system employing these two forms of learning, which can undermine academic progress socioemotionally (e.g., reducing challenge-seeking behavior) and cognitively (e.g., disrupting executive functioning). Their resulting academic disadvantage relative to peers without ACES can grow as they enter the more complex curricula of secondary school.

FIGURE 2.

Two learning pathways linking adverse childhood experiences to educational outcomes. Adapted from: McLaughlin & Sheridan, 2016

This unfolding developmental role of ACES underscores that some experience can happen early in life and then, even when time-limited, set in motion a pathway with cascading effects for education. In this way, childhood sets the stage for a rockier start to adolescence. That rockier start is not predetermined and can be overcome, but young people face higher odds of educational problems in adolescence based on something that was done to them or taken away from them in childhood. This cascade is likely especially important for studying racial/ethnic disparities in educational attainment, although the role of ACES in learning gets talked about more in public health than educational research. Perhaps that is because ACES are considered outside the formal purview of the educational system and educational policy. In other words, educational policymakers and school leaders may be less likely to view changing family or community dynamics as part of their mandate than changing school structures or practices.

Adolescence Setting Up Adulthood

Adolescence can also play out the long way by flowing into adulthood. Maintaining the focus on ACES, we know that ACES predicts lower educational attainment into adulthood (Houtepen et al., 2020), but the role of the aforementioned learning pathways in this lifelong process is less clear because of the dearth of long-term longitudinal data.

Some insight into this process can be gleaned from non-educational research from the Three City Study, which has a predominantly low-income Black and Latinx sample (Cherlin, Hurt, Burton, & Purvin, 2004). This research shows that adult women who suffered sexual abuse early in life, including adolescence, had more unstable patterns of union formation in adulthood. Unlike women who had experienced physical abuse in adolescence and earlier, such women did not avoid relationships with men when they entered adulthood. Instead, they sought out such relationships but did not stay in them. The explanation is that the adult survivors of sexual abuse learned to think they needed such a relationship for protection, status, and/or validation without learning the positive relationship dynamics. Coupled with their own socially and economically disadvantages circumstances, this imbalance between two forms of learning left them vulnerable to relationships with less-than-ideal partners and/or to trouble engaging in whatever relationships they did form. A lingering effect of early life—acknowledged, understood, or not—continued to shape how they viewed themselves and interacted with the larger world even years later.

This focus on the enduring risks of early adversity illustrates how adolescence sets the stage for adulthood, but there are more asset-based dimensions of this life course process that can dilute the potential conclusion that early life determines later life in overly negative ways. Indeed, a substantial minority of young people who face adverse experiences in adolescence and earlier are eventually categorized as “resilient” adults using a variety of definitions, often because they develop strong social and psychological assets in adolescence and are connected to networks of support and opportunities for growth and achievement (Klika & Herrenkohl, 2013). As one example, a meta-analysis of studies from multiple countries suggested a process of “self-righting” that reduced the lingering effects of adversity. In this process, strong social and interpersonal support systems counteracted negative learning processes commonly associated with adverse experiences like maltreatment and allowed young people to more consistently and positively chart their futures and manage challenges (Leung, Chan, & Ho, 2020).

High School Social Life as an Illustration of Adolescence as a Connecting Point

My own research on adolescents has lower stakes than ACES research. Rather than studying abuse and violence, I have focused on the pressures of navigating high school peer cultures in the United States—not necessarily social victimization (e.g., bullying) or mixing with the “wrong” crowd but more often simply the work adolescents have to do to stay afloat. The mixed-methods research in Fitting In, Standing Out (2011) elucidated how these ups and downs of high school social life were rooted in childhood experiences and then had long-term effects on adulthood because the academic distractions they engendered at any one point accumulated to reduce college-going. This life course process crossed socioeconomic and racial/ethnic lines but was more acute for young people with personal circumstances that left them quite vulnerable in the social systems of their high schools (e.g., adolescents who were overweight and/or LGBTQ). Fortunately, as with ACES, there was also potential for resilience in this process. As examples, adolescents who gained a sense of connection and accomplishment through extracurricular activities and who developed a more forwardlooking orientation with support from adults in their lives were less affected in the long term by social challenges in high school.

In an offshoot of this research, my monograph with Gordon and Yang (2013) implicated physical attractiveness in the long-term interplay of social and academic experiences anchored in adolescence (Figure 3a,b). This mixed-methods research revealed that U.S. adolescents viewed by a demographically diverse array of others as attractive had an academic advantage in high school because they received the benefit of the doubt in academic matters, were more confident, and had more support. This academic advantage, however, was chipped away by the many academic distractions that went along with being viewed as attractive (e.g., devoting more time to appearance, dating, maintaining a cool posture). The end result was a truly unearned academic boost in the long-term socioeconomic attainment process through adulthood, including in adult educational and occupational attainment. Interestingly, there was a legacy of earlier attractiveness even if attractiveness ultimately faded. For example, if children were considered cute according to prevailing norms (which, of course, are often unfair, culturally contested, and power-laden), that could start a path-dependent process as they moved into high school that gave them status and associated benefits even if they were not considered attractive adolescents. Having been labeled attractive in a specific social system, they carried that label as long as they were in the same system. Furthermore, attractiveness in adolescence was more important than attractiveness in adulthood in predicting adult outcomes. So, there was an adolescent legacy at work, either because an early advantage cumulatively shaped the path to adulthood or because an early experience of status shaped selfviews that carried across life course stages.

FIGURE 3.

(a) Pathways linking social and academic outcomes across the early life course. Adapted from: Crosnoe, 2011. (b) The longitudinal dynamics of adolescent appearance. Adapted from: Gordon et al., 2013

This legacy of social experience taps into popular interest in adolescence, particularly the idea that high school is hard to escape (Senior, 2013). Life course-structured studies—which cross multiple stages of schooling tailoring data collection to each stage—will help to construct life pathways through the educational system that reveal this legacy and how it can be blocked.

ADOLESCENCE EMERGING FROM AGENCY AND CONSTRAINTS

The research and theory discussed up to this point reveals an adolescent experience—in which interactions with the peer worlds of secondary school filter into the academic domain—that is important in its own right but takes on added importance when viewed within the full life course. Most obviously, this phenomenon captures life course theory’s articulation of living lives the long way. Understanding how adolescents’ lives are lived the long way is facilitated through engagement with the second life course principle mentioned above, which is about the interplay of personal agency and environmental constraints (Figure 4).

FIGURE 4.

The Interplay of personal agency and environmental constraints

Adolescents are highly agentic, meaning they have power—or believe they have power—to purposely engage in behaviors and take actions in the pursuit of goals that they want to achieve. In attempting to forge their own way through life, however, they often get boxed in by external forces that block their paths, obscure the future consequences of their actions, and/or provide perverse incentives for their current actions. Pressures to conform to the prevailing peer norms of a school, or in social media more broadly, are examples of interpersonal forces that may hem in adolescents. On the flipside of constraints are environmental affordances, which open opportunities and facilitate forward progress. School programs that build mentoring relationships or provide academic enrichment are organizational forces that may capitalize on adolescents’ own actions and efforts. Of course, such environmental constraints on adolescents’ agency may be amplified by systemic structural barriers that stratify many societies (e.g., institutional racism, sexualization), but, at the same time, such affordances may be amplified by cultural assets and supports that vary across social and cultural groups (e.g., racial/ethnic identity, immigrant networks of support) (Nico & Caetano, 2021; Schoon & Lyons-Amos, 2017).

The bottom line is that, within a set of environmental constraints and affordances, adolescents try to enact their own agency to help themselves, but what works in the short term may not in the long term. This interplay between person and environment is more pronounced when adolescents come from more disadvantaged or marginalized backgrounds that increase the barriers leading to path dependence as well as the importance of assets and resources in breaking that path dependence. Socioeconomic, racial/ethnic, and sexuality-related differences in schooling offer insight into both the negatives and positives of agency and constraints.

Agency and Constraints in STEM Education

Consider STEM (science, technology, engineering, mathematics) education. Extensive research has documented that how adolescents do in the math/science pipeline in secondary school is a critical factor in their college-going and the adult trajectories that college-going predicts. This research also shows that how adolescents do in this pipeline is a direct function of their preparation and skill development from early childhood through early adolescence.

Personal agency is certainly important to young people’s progress in math and science, as ample evidence documents that their own expectancies and aspirations are significant driving forces (Eccles & Wigfield, 2020). Yet, that agency can be acted upon by a variety of environmental constraints that push some students forward and hold others back. These constraints could be interpersonal in nature, such as when peer influences discourage the appearance of “nerdiness” through overt interest in science or when teachers’ engrained biases about gender create “chilly” math classroom for girls (Buontempo, Riegle-Crumb, Patrick, & Peng, 2017; McKellar, Marchand, Diemer, Malanchuk, & Eccles, 2019; Workman & Heyder, 2020).

Notably, however, many environmental constraints are more structural, such as the constraints imposed by the broader socioeconomic and racial/ethnic stratification of the educational system (Morgan, 2005). For example, seats in advanced math and science courses are a finite commodity. In the intense competition for that commodity, students from more privileged socioeconomic strata have advantages in the form of money to buy assistance, institutional biases that work in their favor, and the disproportionate power of their parents. Such dynamics explain precisely why my own research has reported that, holding preparation constant, adolescents with higher-income college-educated parents had greater access to math and science coursework when they attended more socioeconomically diverse schools than students from other kinds of backgrounds attending more middle-class schools. In the former case, the curriculum and teaching tended to be lower quality, but there were greater odds the student in question gained the curricular credentials that colleges valued. In the latter, the curriculum and teaching tended to be higher quality, but the student in question was more likely to be frozen out of the opportunity to learn and advance. In other words, the interplay between student SES and school SES created a tradeoff between access and enrichment (Crosnoe, 2009).

Such dynamics are also why my research has shown that students from more socioeconomically disadvantaged backgrounds were best positioned to actualize their math and science opportunities in constrained circumstances when their performance and aptitude were so far above the bar that their promise could not be denied. They had to be exceptional, to stand out. The flipside was that students from more socioeconomically advantaged backgrounds often gained heightened access to math and science opportunities that their weaker preparation and lower ability suggested that they did not deserve (Crosnoe & Schneider, 2010).

This phenomenon, in which structural/interpersonal dynamics block agency on the low end of the socioeconomic spectrum and make it less consequential on the high end, likely factors into a striking inequality in higher education described in Tough’s 2019 book The Years that Matter Most. This inequality is centered on the privileged position of academically mediocre but socioeconomically advantaged high school students in admissions to elite—but not the most elite—private universities. Because such students lack “better” options but can pay full tuition, they may be more attractive to some colleges than even more accomplished students from less affluent backgrounds regardless of such factors as motivation and effort.

Agency and Constraints in School Discipline

Research on the school-to-prison pipeline also demonstrates how micro-level decisions to discipline students could have macro-level consequences by accumulating to gradually push out “bad apples” from the educational system during adolescence and push them into the criminal justice system in adulthood. This process can occur through practical mechanisms (e.g., absences from school reduce the academic preparation needed to persist in school) and more complicated ones (e.g., schools writing off disciplined students as academic lost causes who warrant less attention and opportunity) (Arum, 2003; Mallett, 2016).

Yes, this process is related (sometimes loosely) to the actions and motivations of individual adolescents, many of whom engage in behaviors that put themselves and others at risk and need to be addressed. Still, the school-to-prison pipeline cannot happen without environmental constraints. Those environmental constraints could be educational policies, such as zero tolerance, that translate minor infractions and even misunderstandings into major consequences. They also could take the form of systemic racism and classism, which can optically transform some behavior or event from harmless into harmful depending on the social location of the actor, such as default labeling of African American boys as trouble or dangerous (Bell, 2015; Marsh & Noguera, 2018). Notably, there are also affordances at work in some schools that protect young people from diverse backgrounds and recognize their assets, such as trauma-informed approaches to schooling, restorative justice programs, and social emotional learning curricula (Durlak, Weissberg, Dymnicki, Taylor, & Schellinger, 2011; Thomas, Crosby, & Vanderhaar, 2019).

Importantly, such varied dimensions of environmental constraints (and affordances) in the school-to-prison pipeline can be influenced by the socioeconomic and racial/ethnic composition of the school, community, and population in which individual adolescents live. For example, a study by my own student shows that that the academic consequences of school suspension for African American boys were more pronounced when they attended schools in which their same-race peers were overrepresented in discipline cases, perhaps because they “looked the part” and had their opportunities constrained as a result. There is also an affordance side to this phenomenon, however, as evidenced by another study conducted by my students. It showed that Latinx boys were disciplined less in school when they lived in “gateway destination” counties where Latinx immigration was a long-established phenomenon, perhaps because their greater “familiarity” afforded them more equitable treatment (Snidal, 2021; Snidal & Ackert, 2021). Both cases suggest how adolescents’ behavior—real or imagined—can be interpreted through an environmentally refracted lens.

Agency and Constraints in the Lives of LGBTQ Adolescents

Over the last decade, research has effectively documented the hostile peer environments that LGBTQ youth face in school, often centered on gender nonconformity and not just sexuality. Illustrating minority stress theory, they can suffer psychologically in these schools. Those social and psychological challenges of navigating school pose academic risks, regardless of preparation or ability (Crosnoe, 2011; Pascoe, 2011; Toomey, McGuire, & Russell, 2012).

As documented in an article in this journal, this frequently worrisome link between the social and academic lives of LGBTQ adolescents in secondary school is not invariant across the growing LGBTQ population (Watson & Russell, 2016). Although some LGBTQ adolescents in the study did academically disengage from school to stay out of harm’s way, others actively engaged in school as way of associating themselves with spaces of achievement. This variation is a window into personal agency, tapping into the ways that some adolescents are able to survey a threatening landscape and figure out how to cope in that moment.

Again, however, that personal agency is enacted within a system of environmental constraints and affordances. For example, growing evidence suggests that some schools create better academic contexts for LGBTQ adolescents through the constructions of clubs and programs that promote inclusivity. Such institutional supports can change peer dynamics or buffer adolescents from the harm of peer dynamics that remain unchanged. In either case, some LGBTQ adolescents enter an educational environment that obviates the need for personal agency or facilitates more positive enactments of agency (Griffin, Lee, Waugh, & Beyer, 2004; Kosciw, Palmer, Kull, & Greytak, 2013).

Another example of the interplay of personal agency and environmental constraints comes from research conducted by another former student (Martin-Storey, Cheadle, Skalamera, & Crosnoe, 2015). This network analysis showed that the social penalties of LGBTQ status were weaker in a predominantly African American school and heightened in a predominantly White school. Perhaps the former allowed students to be treated according to a range of characteristics, rather than one alone, and also presented less conformity pressure overall. Such a pattern reinforces the idea that where adolescents go to school (whether by choice or not) matters—socially, academically, and for the connection between the two.

The Importance of Integrative Perspectives

Reflecting on the balance between personal agency and environmental constraints (and affordances) in adolescents’ lives lived the long way, therefore, there are advantages and disadvantages within interpersonal, institutional, and structural systems that create a space—sometimes small, sometimes larger—for adolescents to operate, and adolescents try very hard to make that agentic operation work. Experiencing this drive to personal agency with still-developing brains that reduce long-term analysis, however, they may make poor decisions (which adults often see clearly) but for good reasons (which adults may not always recognize). Here is where mixed-methods approaches that allow for a quantitative assessment of the environment with qualitative exploration of the individualized experiences of students from different groups within that environment would likely have great impact.

THE CHALLENGES OF DYNAMIC AND CONTEXTUALIZED RESEARCH ON ADOLESCENCE

These insights into adolescence as a dance between personal agency and environmental constraints (and affordances) connecting childhood to adulthood are ultimately why social and behavioral research is important. In my two decades of conducting such research, however, I have accepted that we have the burden of demonstrating that importance to others, especially its practical importance.

The Policy Dilemma

Policy dilemma is a term I use for the reality that, sometimes, the things that most powerfully influence adolescent development are also the most difficult to manipulate through large-scale policy intervention. The social worlds of secondary school fall into that category. After all, we can agree that the peer dynamics of U.S. schools are a developmental ecology, good or bad, but we will have a harder time agreeing on how those dynamics can be changed from the outside. A common argument from sociologists has been that those important but hard-to-manipulate interpersonal ecologies of adolescence can be indirectly changed by linking them to less influential but more policy amenable aspects of schools, like structure, composition, and curriculum (Coleman, 1990). This argument runs through Fitting In, Standing Out.

An argument from developmental scientists may be that the cumulative insights of developmental research offer powerful tools for changing the world that adolescents grow up in, as this scientific literature shapes the ways that adults perceive, treat, and serve adolescents and build the environments in which they emerge from childhood and prepare for adulthood in more positive and healthier ways (National Academies, 2019). The cumulative knowledge about attachment that psychologists have constructed over many decades, for example, has had a profound impact on modern parenting and teaching in developed societies, above and beyond the effectiveness of any specific policy or intervention (Berlin, Zeanah, & Lieberman, 2008; Sears & Sears, 2001).

There is also the argument that we can try harder to locate aspects of the developmental ecology of adolescence that are both meaningfully impactful in everyday life and feasibly policy amenable on a large scale. We need to find the right angle.

A National Intervention for Adolescents

My participation in a large-scale team science project facilitated my learning of this lesson about the policy dilemma. Specifically, the National Study of Learning Mindsets (NSLM) was built on the growth mindset concept that thinking of intelligence as malleable through trial and error—and seeing the brain as a muscle that needs to be worked out—is a factor in academic achievement as well as demographic disparities in achievement.

My colleagues in the sociology of education and I had long criticized this growth mindset research as psychologizing inequality, telling those at the bottom of a highly stratified educational system that they just needed to try harder and believe more in themselves. In working with developmental, social, and cognitive psychologists who were more convinced by the power of growth mindsets, we began to see that we had unfairly simplified this approach to educational inequality. Consequently, we joined forces to study the sociological contextualization of a psychological intervention—how the effectiveness of a growth mindset intervention could be constrained or amplified by environmental differences across schools.

Led by David Yeager, this team launched one of the largest-ever national studies of the variable impact of a psychological intervention. The NLSM was a randomized control trial of an online school-based intervention to help U.S. adolescents develop growth mindsets at the start of high school (Figure 5) that followed the nationally representative sample of over 12,000 ninth graders in more than 60 high schools over time to track their subsequent academic achievement.

FIGURE 5.

Excerpt of intervention in National Study of Learning Mindsets. See: Yeager et al., 2019

As reported in a 2019 article in Nature and in other publications (Yeager et al., 2019, 2021), the growth mindset intervention had an average treatment effect on academic outcomes across ninth grade in this national sample. This effect was positive and significant (e.g., higher grades overall and in math, more academic challenge-seeking, higher enrollment in advanced math coursework). The average, however, was moderate in magnitude because the intervention worked in some schools but not others. For example, it had less value in the academically weakest high schools where opportunities to get ahead were constrained and in the academically strongest schools where pervasive privilege diluted the value of the mindset. The intervention mainly worked between these two ends, in schools that were not too little or too much. Digging deeper revealed that, even when the intervention developed growth mindsets, those mindsets did not translate into academic benefits in math classrooms headed by teachers who did not share their mindsets. Such teachers were not giving adolescents the affordances they needed to act on their mindsets (e.g., by offering opportunities to revise, by using mistakes to teach), especially when adolescents came from groups with long histories of marginalization within schools.

Thus, some schools and classrooms were structured to allow the growth mindset to “turn on” academic consequences, but others blocked—or constrained—that from happening. Which adolescent was exposed to which environment mapped onto the entrenched stratification of the educational system. The takeaway is that an intervention that changes the adolescent likely needs the system to be open to that changed adolescent in order to realize its full effect. At the same time, policies that change the system will likely have variable effects on individual students who engage with the system in different ways. If so, individualized interventions and large-scale policy reforms are not either/or propositions but instead partners that should be packaged together. Designs that marry the national assessment of schools and education from the National Center for Education Statistics with the intensive psychological and cognitive assessment of young people in the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) Study would be an ideal venue for that packaging.

THE STORY OF ADOLESCENCE

Metaphorically, the scientific enterprise is also about the art of story. Legions of scientists work independently and collaboratively across time and place to carefully sift through evidence and arguments as a means of gradually constructing a plausible story about some phenomenon. By necessity, that story will downplay some details and exceptions and gloss over variabilities, but that granular loss is countered by the value of developing a more general and abstract narrative that facilitates collective understanding and action.

Here, the story is about adolescent development; in particular, about the intersection between the social and academic components of adolescents’ developmental journey and how this journey connects their pasts to their futures. It focuses on the under-appreciated role of adolescents as agentic learners—moving through an exceedingly complex social landscape and attempting to make sense of where things stand and how they fit in by looking inward at themselves and outward at the world around them. That social learning, in turn, can support or undermine their academic learning. Whether the synergy between the two forms of learning leans toward the positive or negative or somewhere in between can change from the short term to the long term. Complicating this story is the larger social structure that adolescents grow up in and cannot be separated from, which directly shapes their social learning and their adolescent learning while also affecting the connection between the two.

Adults often dismiss the social ups and downs of adolescence as simply part of growing up, as something adolescents fixate on now but will get over as they age, as a time-limited experience without lasting residue. That common reaction ignores the stakes. The social lives of adolescents are important in their own right because they strike at the heart of the concept of well-being, a concept that is just as likely to connect stages of the life course than differentiate them. They also are important because they factor into other domains of life, such as the educational trajectories that are now widely seen as a key illustration of the highly cumulative nature of the life course in the modern global era. In both cases, what matters to the individual also offers profound insights into the state of society, how it creates opportunities for some and forecloses opportunities for others but also how it can change in the future.

Goal-directed or seemingly random, consumed by the immediate or cognizant of the future, aware of disadvantage and privilege or lacking insight into environmental constraints on personal thought and action, adolescents make their way from childhood into adulthood with an array of strategies along an array of paths. They search for meaning amidst the complexities of their lives along the way, and the researchers who use science to construct a story about adolescence are in effect searching for meaning too.

Acknowledgments

This article is based on the presidential address prepared by the author for the canceled 2020 Biennial Meeting of the Society for Research on Adolescence. The author acknowledges the support of grants from the National Science Foundation (SES-1424111, PI: Robert Crosnoe; 1519686, PIs: Elizabeth Gershoff and Robert Crosnoe; 1760481, PIs: Tama Leventhal and Robert Crosnoe), the National Institutes of Health (NICHD 1R01HD081022-01A1, PIs: Rachel Gordon and Robert Crosnoe; NICHD P2CHD042849, PI: Debra Umberson; NIDA 1R03DA046046-01A1, PI: Robert Crosnoe), and the National Institute of Justice (2014-IJ-CX-0025, PI: Robert Crosnoe) to the Population Research Center (PRC) at the University of Texas at Austin as well as a number of grants to the PRC supporting the development, management, and dissemination of the National Study of Learning Mindsets (e.g., National Science Foundation HRD 1761179, Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation OPP 1197627 and INV-004519, Raikes Foundation 17-01177, William T. Grant Foundation 189706, and Optimus Foundation 47515; PIs: David Yeager, Chandra Muller, and Robert Crosnoe). The presidential address would have included sincere thanks to a large number of people, including former and current mentors, colleagues, and students. Acknowledgements for this article will be limited to those colleagues in the Society for Research on Adolescence who graciously reviewed this manuscript and provided helpful advice (Aprile Benner, Bo Cleveland, Rashmita Mistry, Velma McBride Murry, John Schulenberg, and Tama Leventhal), key early career mentors (formal advisors Glen Elder and the late Sandy Dornbusch as well as Aletha Huston and Barbara Schneider, who guided the William T. Grant project from which so much of the research featured here emerged), and the family members who were the most important supports and inspirations of all (Shannon Cavanagh and Caven, Sue, Joseph, and Caroline Crosnoe).

Footnotes

For diverse perspectives on the socializing role of peers in secondary school and their future implications, see: Kao, Joyner, & Balistreri, 2019; Graham & Echols, 2018; Camacho et al., 2018; Delgado et al., 2016; Way, 2015; Toomey, McGuire, & Russell, 2012; Hughes et al., 2011; Carter, 2006; Milner, 2004

REFERENCES

- Allen JP, Porter MR, McFarland CF, Marsh P, & McElhaney KB (2005). The two faces of adolescents’ success with peers: Adolescent popularity, social adaptation, and deviant behavior. Child Development, 76, 747–760. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2005.00875.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arum R (2003). Judging school discipline: The crisis of moral authority. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bell C (2015). The hidden side of zero tolerance policies: The African American perspective. Sociology Compass, 9, 14–22. 10.1111/soc4.12230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berlin L, Zeanah C, & Lieberman A (2008). Prevention and intervention programs for supporting early attachment security. In Cassidy J, & Shaver PR (Eds.), Handbook of attachment (pp. 745–761). New York: Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- Brown CS (2021). Unraveling bias: How prejudice has shaped children for generations and why it’s time to break the cycle. Dallas: BenBella. [Google Scholar]

- Buontempo J, Riegle-Crumb C, Patrick A, & Peng M (2017). Examining gender differences in engineering identity among high school engineering students. Journal of Women and Minorities in Science and Engineering, 23(3), 271–287. 10.1615/JWomenMinorScienEng.2017018579 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Camacho TC, Medina M, Rivas-Drake D, & Jagers R (2018). School climate and ethnic-racial identity in school: A longitudinal examination of reciprocal associations. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 28, 29–41. 10.1002/casp.2338 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carter P (2006). Keepin’ it real: School success beyond black and white. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cherlin AJ, Hurt TR, Burton LM, & Purvin DM (2004). The influence of physical and sexual abuse on marriage and cohabitation. American Sociological Review, 69, 768–789. 10.1177/000312240406900602 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman J (1961). The adolescent society: The social life of the teenager and its impact on education. New York, NY: Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman JS (1990). Foundations of social theory. Cambridge, MA: Harvard. [Google Scholar]

- Crabbe R, Pivnick LK, Bates J, Gordon RA, & Crosnoe R (2018). Contemporary college students’ reflections on their high school peer crowds. Journal of Adolescent Research, 34, 563–596. 10.1177/0743558418809537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crosnoe R (2009). Low-income students and the socioeconomic composition of public high schools. American Sociological Review, 74, 709–730. 10.1177/000312240907400502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crosnoe R (2011). Fitting in, standing out: Navigating the social challenges of high school to get an education. New York: Cambridge. [Google Scholar]

- Crosnoe R, & Johnson MK (2011). Research on adolescence in the 21st century. Annual Review of Sociology, 37, 439–460. 10.1146/annurev-soc-081309-150008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crosnoe R, & Schneider B (2010). Social capital, information, and socioeconomic disparities in math course work. American Journal of Education, 117, 79–107. 10.1086/656347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delgado MY, Ettekal AV, Simpkins SD, & Schaefer DR (2016). How do my friends matter? Examining Latino adolescents’ friendships, school belonging, and academic achievement. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 45, 1110–1125. 10.1007/s10964-015-0341-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desmond M, & López Turley RN (2009). The role of familism in explaining the Hispanic-White college application gap. Social Problems, 56, 311–334. 10.1525/sp.2009.56.2.311 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Didion J (1979). The white album. New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux. [Google Scholar]

- Duell N, & Steinberg L (2021). Adolescents take positive risks, too. Developmental Review, 62. 10.1016/j.dr.2021.100984 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Duke NN, Pettingell SL, McMorris BJ, & Borowsky IW (2010). Adolescent violence perpetration: Associations with multiple types of adverse childhood experiences. Pediatrics, 125, e778–e786. 10.1542/peds.2009-0597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durlak JA, Weissberg RP, Dymnicki AB, Taylor RD, & Schellinger KB (2011). The impact of enhancing students’ social and emotional learning: A meta-analysis of school-based universal interventions. Child Development, 82, 405–432. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01564.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eccles JS, & Wigfield A (2020). From expectancy-value theory to situated expectancy-value theory: A developmental, social cognitive, and sociocultural perspective on motivation. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 61, 101859. 10.1016/j.cedpsych.2020.101859 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eckert P (1989). Jocks and burnouts: Social identity in the high school. New York: Teachers College Press. [Google Scholar]

- Elder GH Jr, Johnson MK, & Crosnoe R (2003). The emergence and development of life course theory. In Mortimer J, & Shanahan M (Eds.), Handbook of the life course (pp. 3–22). New York: Plenum. [Google Scholar]

- Elder GH, Shanahan MJ, & Jennings JA (2015). Human development in time and place. In Bornstein MH, & Leventhal T (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology and developmental science: Ecological settings and processes in developmental systems, 4 edn (pp. 6–54). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis BJ, Volk AA, Gonzalez JM, & Embry DD (2016). The meaningful roles intervention: An evolutionary approach to reducing bullying and increasing prosocial behavior. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 26, 622–637. 10.1111/jora.12243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein R, Blake J, & González T (2017). Girlhood interrupted: The erasure of black girls’ childhood. Washington, DC: Georgetown Law. [Google Scholar]

- Faris R, & Felmlee D (2011). Status struggles: Network centrality and gender segregation in same-and crossgender aggression. American Sociological Review, 76, 48–73. 10.1177/0003122410396196 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, Williamson DF, Spitz AM, Edwards V, … Marks JS (1998). Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 14, 245–258. 10.1016/S0749-3797(98)00017-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flaherty EG, Thompson R, Dubowitz H, Harvey EM, English DJ, Proctor LJ, & Runyan DK (2013). Adverse childhood experiences and child health in early adolescence. JAMA Pediatrics, 167, 622–629. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flores-Gonzalez N (2005). Popularity versus respect: School structure, peer groups and Latino academic achievement. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 18, 625–642. 10.1080/09518390500224945 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Frank KA, Muller C, Schiller KS, Riegle-Crumb C, Mueller AS, Crosnoe R, & Pearson J (2008). The social dynamics of mathematics coursetaking in high school. American Journal of Sociology, 113, 1645–1696. 10.1086/587153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon RA, Crosnoe R, & Wang X (2013). Physical attractiveness and the accumulation of social and human capital in adolescence and young adulthood: Assets and distractions. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 78(6), 1–137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham S, & Echols L (2018). Race and ethnicity in peer relations research. In Bukowski WM, Laursen B, & Rubin KH (Eds.), Handbook of peer interactions, relationships, and groups (pp. 590–614). New York: Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- Griffin P, Lee C, Waugh J, & Beyer C (2004). Describing roles that gay-straight alliances play in schools: From individual support to school change. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Issues in Education, 1, 7–22. 10.1300/J367v01n03_03 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Harden KP (2014). A sex-positive framework for research on adolescent sexuality. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 9, 455–469. 10.1177/1745691614535934 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helms SW, Choukas-Bradley S, Widman L, Giletta M, Cohen GL, & Prinstein MJ (2014). Adolescents misperceive and are influenced by high-status peers’ health risk, deviant, and adaptive behavior. Developmental Psychology, 50, 2697–2714. 10.1037/a0038178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houtepen LC, Heron J, Suderman MJ, Fraser A, Chittleborough CR, & Howe LD (2020). Associations of adverse childhood experiences with educational attainment and adolescent health and the role of family and socioeconomic factors: A prospective cohort study in the UK. PLoS Med, 17(3), e1003031. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes DL, McGill RK, Ford KR, & Tubbs C (2011). Black youths’ academic success: The contribution of racial socialization from parents, peers, and schools. In Hill N, Mann T, & Fitzgerald H (Eds.), African American children and mental health (pp. 95–124). Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger/ABC-CLIO. [Google Scholar]

- Jewell J, Spears Brown C, & Perry B (2015). All my friends are doing it: Potentially offensive sexual behavior perpetration within adolescent social networks. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 25, 592–604. 10.1111/jora.12150 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MK, Crosnoe R, & Elder GH Jr (2011). Insights on adolescence from a life course perspective. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 21, 273–280. 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00728.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kao G, Joyner K, & Balistreri KS (2019). The company we keep: Interracial friendships and romantic relationships from adolescence to adulthood. New York: Russell Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Klika JB, & Herrenkohl TI (2013). A review of developmental research on resilience in maltreated children. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 14, 222–234. 10.1177/1524838013487808 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosciw JG, Palmer NA, Kull RM, & Greytak EA (2013). The effect of negative school climate on academic outcomes for LGBT youth and the role of inschool supports. Journal of School Violence, 12, 45–63. 10.1080/15388220.2012.732546 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kreager D, & Staff J (2009). The sexual double standard and adolescent peer acceptance. Social Psychology Quarterly, 72, 143–164. 10.1177/019027250907200205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreager DA, Staff J, Gauthier R, Lefkowitz ES, & Feinberg ME (2016). The double standard at sexual debut: Gender, sexual behavior and adolescent peer acceptance. Sex Roles, 75, 377–392. 10.1007/s11199-016-0618-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerner RM (2017). Commentary: Studying and testing the positive youth development model: A tale of two approaches. Child Development, 88, 1183–1185. 10.1111/cdev.12875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerner RM, Lewin-Bizan S, & Warren AEA (2010). Concepts and theories of human development: Historical and contemporary dimensions. In Bornstein MH, & Lamb ME (Eds.), Developmental science: An advanced textbook (pp. 3–49). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Leung DY, Chan AC, & Ho GW (2020). Resilience of emerging adults after adverse childhood experiences: A qualitative systematic review. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 1524838020933865. 10.1177/1524838020933865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallett CA (2016). The school-to-prison pipeline: From school punishment to rehabilitative inclusion. Preventing School Failure: Alternative Education for Children and Youth, 60, 296–304. 10.1080/1045988X.2016.1144554 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh LTS, & Noguera PA (2018). Beyond stigma and stereotypes: An ethnographic study on the effects of school-imposed labeling on Black males in an urban charter school. Urban Review, 50, 447–477. 10.1007/s11256-017-0441-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Storey A, Cheadle JE, Skalamera J, & Crosnoe R (2015). Exploring the social integration of sexual minority youth across high school contexts. Child Development, 86, 965–975. 10.1111/cdev.12352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKellar SE, Marchand AD, Diemer MA, Malanchuk O, & Eccles JS (2019). Threats and supports to female students’ math beliefs and achievement. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 29, 449–465. 10.1111/jora.12384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenney SJ, & Bigler RS (2016). High heels, low grades: Internalized sexualization and academic orientation among adolescent girls. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 26, 30–36. 10.1111/jora.12179 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin KA, & Sheridan MA (2016). Beyond cumulative risk: A dimensional approach to childhood adversity. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 25, 239–245. 10.1177/0963721416655883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milner M (2004). Freaks, geeks, and cool kids: American teenagers, schools, and the culture of consumption. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Monahan KC, Steinberg L, & Cauffman E (2009). Affiliation with antisocial peers, susceptibility to peer influence, and antisocial behavior during the transition to adulthood. Developmental Psychology, 45, 1520–1530. 10.1037/a0017417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan SL (2005). On the edge of commitment: Educational attainment and race in the United States. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (2019). The promise of adolescence: Realizing opportunity for all youth. Washington, DC: National Academies Press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nico M, & Caetano A (Eds.) (2021). Structure and agency in young people’s lives: Theory, methods and agendas. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Pál J, Stadtfeld C, Grow A, & Takács K (2016). Status perceptions matter: Understanding disliking among adolescents. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 26, 805–818. 10.1111/jora.12231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pascoe CJ (2011). Dude, you’re a fag. Berkeley, CA: University of California. [Google Scholar]

- Ream RK (2003). Counterfeit social capital and Mexican-American underachievement. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 25, 237–262. 10.3102/01623737025003237 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Salomon I, & Brown CS (2019). The selfie generation: Examining the relationship between social media use and early adolescent body image. Journal of Early Adolescence, 39, 539–560. 10.1177/0272431618770809 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schoon I, & Lyons-Amos M (2017). A socio-ecological model of agency: The role of structure and agency in shaping education and employment transitions in England. Journal of Longitudinal and Lifecourse Studies, 8, 35–56. 10.14301/llcs.v8i1.404 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schriber RA, Rogers CR, Ferrer E, Conger RD, Robins RW, Hastings PD, & Guyer AE (2018). Do hostile school environments promote social deviance by shaping neural responses to social exclusion? Journal of Research on Adolescence, 28, 103–120. 10.1111/jora.12340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sears R, & Sears M (2001). The attachment parenting book. New York: Little, Brown. [Google Scholar]

- Senior J (2013). Why you never truly leave high school. New York Magazine January 18, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Snidal M (2021). Suspended in context: School discipline, STEM course taking, and school racial/ethnic composition. Social Science Research, 93, 102502. 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2020.102502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snidal M & Ackert E (2021). Latino/a school suspensions across destinations: A test of the racial/ethnic threat hypothesis. Paper presented at the 2021 annual meeting of the Population Association of America. [Google Scholar]

- Spencer MB, Harpalani V, Cassidy E, Jacobs CY, Donde S, Goss TN, … Wilson S (2006). Understanding vulnerability and resilience from a normative developmental perspective: Implications for racially and ethnically diverse youth. In Cicchetti D, & Cohen DJ (Eds.), Developmental psychopathology: Theory and method (pp. 627–672). New York: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L (2008). A social neuroscience perspective on adolescent risk-taking. Developmental Review, 28(1), 78–106. 10.1016/j.dr.2007.08.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L, Brown BB, & Dornbusch SM (1997). Beyond the classroom. New York: Simon and Schuster. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas MS, Crosby S, & Vanderhaar J (2019). Trauma-informed practices in schools across two decades: An interdisciplinary review of research. Review of Research in Education, 43, 422–452. 10.3102/0091732X18821123 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tolman DL, & McClelland SI (2011). Normative sexuality development in adolescence: A decade in review, 2000–2009. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 21, 242–255. 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00726.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Toomey RB, McGuire JK, & Russell ST (2012). Heteronormativity, school climates, and perceived safety for gender nonconforming peers. Journal of Adolescence, 35, 187–196. 10.1016/j.adolescence.2011.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tough P (2019). The years that matter most. New York: Random House. [Google Scholar]

- Watson RJ, & Russell ST (2016). Disengaged or bookworm: Academics, mental health, and success for sexual minority youth. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 26, 159–165. 10.1111/jora.12178 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Way N (2014). Deep secrets: Boys’ friendships and the crisis of connection. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University. [Google Scholar]

- Workman J, & Heyder A (2020). Gender achievement gaps: the role of social costs to trying hard in high school. Social Psychology of Education, 23, 1407–1427. 10.1007/s11218-020-09588-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yeager DS, Carroll JM, Buontempo J, Cimpian A, Woody S, Crosnoe R, … Dweck C (2021). Teacher mindsets help explain where a growth mindset intervention does and doesn’t work. Psychological Science. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeager DS, Hanselman P, Walton GM, Murray JS, Crosnoe R, Muller C, … Dweck CS (2019). A national experiment reveals where a growth mindset improves achievement. Nature, 573, 364–369. 10.1038/s41586-019-1466-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeiders KH, Updegraff KA, Umaña-Taylor AJ, McHale SM, & Padilla J (2016). Familism values, family time, and Mexican-Origin young adults’ depressive symptoms. Journal of Marriage and Family, 78, 91–106. 10.1111/jomf.12248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]