Abstract

Purpose:

Although first-line crizotinib treatment leads to clinical benefit in ROS1+ lung cancer, high prevalence of crizotinib-resistant ROS1-G2032R mutation and progression in the central nervous system (CNS) represents a therapeutic challenge. Here, we investigated the anti-tumor activity of repotrectinib, a novel next-generation ROS1/TRK/ALK-tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) in ROS1+ patient-derived preclinical models.

Experimental Design:

Anti-tumor activity of repotrectinib was evaluated in ROS1+ patient-derived preclinical models including treatment-naïve and ROS1G2032R models and was further demonstrated in patients enrolled in on-going phase 1/2 clinical trial (NCT03093116). Intracranial anti-tumor activity of repotrectinib was evaluated in a mouse brain-metastasis model.

Results:

Repotrectinib potently inhibited in vitro and in vivo tumor growth and ROS1-downstream signal in treatment-naïve YU1078 compared with clinically available crizotinib, ceritinib, and entrectinib. Despite comparable tumor regression between repotrectinib and lorlatinib in YU1078-derived xenograft model, repotrectinib markedly delayed the onset of tumor recurrence following drug withdrawal. Moreover, repotrectinib induced profound anti-tumor activity in the CNS with efficient blood-brain barrier (BBB) penetrating properties. Notably, repotrectinib showed selective and potent in vitro and in vivo activity against ROS1G2032R. These findings were supported by systemic and intracranial activity of repotrectinib observed in patients enrolled in the on-going clinical trial.

Conclusions:

Repotrectinib is a novel next-generation ROS1-TKI with improved potency and selectivity against treatment-naïve and ROS1G2032R with efficient CNS penetration. Our findings suggest that repotrectinib can be effective both as first-line and after progression to prior ROS1-TKI.

Keywords: ROS1-tyrosine kinase inhibitor, solvent-front mutation, central nervous system, Resistance, patient-derived preclinical models

INTRODUCTION

Chromosomal rearrangements in ros proto-oncogene1 (ROS1) gene defines a distinct molecular subset in non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) (1–3). The development of ROS1 targeted agents and the approval of crizotinib as a standard first-line therapy has transformed the course of disease for ROS1-driven NSCLC. Although ROS1 tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) markedly improved clinical outcomes, patients inevitably relapse within a few years, and subsequent therapy overcoming acquired resistance remains limited (3,4). Several major resistance mechanisms to ROS1-TKIs have been identified, including secondary mutations within the ROS1 kinase domain and activation of bypass signaling pathways (1,5). Approximately 50–60% crizotinib-resistant mutations are found within the ROS1 kinase, of which ROS1 G2032R solvent-front mutation (SFM) is the most common and recalcitrant resistant mutation. These reports highlight the importance of developing novel ROS1 inhibitors with potent activity against G2032R (1,6).

The brain is considered a major pharmacologic sanctuary because of the blood-brain barrier (BBB) (7,8). Indeed, approximately 50% of patients treated with ROS1-TKIs experience disease progression due to central nervous system (CNS) metastases (7,9). The high incidence of CNS progression and poor prognosis in ROS1-rearranged NSCLC indicates an unmet clinical need for novel ROS1-TKIs with improved efficacy against brain lesions.

Repotrectinib (TPX-0005) is a novel next-generation ROS1/TRK/ALK-TKI specifically designed to overcome refractory SFMs, which commonly emerge in patients with ROS1/NTRK/ALK-rearranged malignancies who have relapsed on currently available TKIs (10). Repotrectinib for TKI-refractory patients is currently under phase 1/2 clinical trial (NCT03093116).

Existing preclinical studies in ROS1-rearranged NSCLC use a limited number of commercial or genetically engineered cell lines. This fails to fully encompass the genetic complexities observed in patients, leading to discrepancies between preclinical and clinical drug responses. Here, we evaluated the antitumor activity of repotrectinib in ROS1+ NSCLC patient-derived cell lines (PDC) and patient-derived xenograft (PDX) models. Moreover, we examined the intracranial antitumor activity of repotrectinib in a brain-metastasis mouse model developed through intracranial PDC implantation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

All patient samples were obtained from patients with ROS1-rearrangements before and after treatment with ROS1-TKIs at Yonsei University Severance Hospital (Seoul, Republic of Korea). All patients provided written informed consent. The study protocol has been approved by the Institutional Review Board of Severance Hospital (IRB no.: 4-2016-0788). Patients treated with repotrectinib are enrolled in clinical trial (NCT-03093116). This study was conducted according to the principles set out in the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki and the United States Department of Health and Human Services Belmont Report.

Establishment of PDCs

Patient-derived cell lines were established from malignant effusions of patients with advanced lung adenocarcinoma (11). Briefly, patient pleural effusion samples were centrifuged at 500 ×g for 10 min at 25ºC and resuspended in PBS. Cells were separated with Focil-PaquePLUS solution, following manufacturer protocol. The interface containing the mononuclear cells was washed twice in HBSS and plated on collage IV-coated plates in RPMI medium supplemented with 10% FBS. To determine whether PDCs maintained patient characteristics, sanger sequencing and whole-exome sequencing were performed. FACS staining of EpCAM confirmed PDCs with over 99% cancer purity.

The following ROS1-rearranged PDCs were used: YU1078 (CD74-ROS1) and YU1079 (CD74-ROS1 G2032R) (Table 1). Sanger-sequencing-identified fusion partners in PDCs were identical to those identified in corresponding patient biopsies.

Table 1.

Patient-derived cell lines (PDCs), patient-derived xenograft models (PDXs) and tumor biopsies from ROS1-rearragned NSCLC patients

| Patient | Type | Model ID | Fusion Partner | Biopsy Site | ROS1 mutation | Targeted therapy preceding biopsy | Best RECIST response | Treatment Duration (month) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient #1-1 | PDC | YU1078 | CD74-ROS1 | Pleural effusion | WT | Naive | - | - |

| Patient #1-2 | PDC | YU1079 | CD74-ROS1 | Pleural effusion | G2032R | Crizotinib | PR | 10 |

| Patient #2 | PDX | YHIM1047 | CD74-ROS1 | Lung | G2032R | Entrectinib | PR | 7 |

| Patient A | Patient biopsy | - | CD74-ROS1 | Lung | WT | Repotrectinib | PR | 10 |

| Patient B | Patient biopsy | - | SLC34A2-ROS1 | Lung | WT | Repotrectinib | PR | 10 |

PDC, Patient-derived Cell Line; PDX, Patient-derived Xenograft; WT, Wild-type; PR, Partial Response

Establishment of PDXs

ROS1-rearranged PDX model YHIM1047 was established as previously described (12) (Table 1).To generate PDC-derived tumor xenograft models, cells (YU1078 and YU1079, 5 × 106 in 100 µl) were implanted subcutaneously into the flanks of 6-week-old female nu/nu mice. Animals were randomly divided (N = 5 per group) when tumors volume reached 150–200 mm3. Each group received one of the following treatments: once-daily crizotinib (50 mg/kg, qd), ceritinib (25 mg/kg, qd), entrectinib (30 mg/kg, qd), lorlatinib (30 mg/kg, qd), cabozantinib (30 mg/kg, qd), and twice-daily repotrectinib (15 mg/kg, b.i.d.). Tumor volumes (0.532 × length × width) were measured with an electronic caliper. Percentage change in tumor volume was calculated as follows: (Vt-V0)/V0 × 100. Tumor growth inhibition (TGI) was calculated with two formulas according to Drilon et al. (10). All mice were euthanized via CO2 inhalation at the end of the experiment. Animal procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) and Animal Research Committee at Yonsei University College of Medicine.

ROS1 tyrosine kinase inhibitors

Repotrectinib (TP therapeutics, CA, USA) was kindly provided by the manufacturer and crizotinib, ceritinib, entrectinib, lorlatinib and cabozantinib were purchased from Selleckchem (TX, USA).

Cell proliferation assay

About 2500 – 3000 cells were seeded in 96-well plates in growth media and incubated overnight at 37°C before adding serially diluted crizotinib, ceritinib, lorlatinib, cabozantinib, repotrectinib and appropriate controls. After treating the drugs, cells were incubated at 37°C for 72 hours before performing Cell Titer Glo (Promega, WI, USA) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Dose-response curves and IC50 values were calculated using GraphPad Prism.

Colony forming assays were performed by seeding the cells in 6-well plates in growth media with appropriate drug-containing media replaced every three days. Plates were fixed in 4% PFA and stained in crystal violet for 1 hour after 14 days of drug treatment.

Immunoblotting

Immunoblots were performed to determine relative phosphorylation of kinases and total protein levels of interest. Protein samples were separated by SPS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membrane for immunoblotting using the corresponding antibodies. P-ROS1 (T2274), ROS1, p-ERK (T202/Y204), ERK, p-AKT (S473), AKT, p-STAT3 (T705), STAT3 and ki-67 were all purchased from Cell Signaling Technologies (MA, USA). Beta-actin was purchased from Sigma (MO, USA).

Intracranial tumor model

Intracranial tumor models were generated through implanting YU1078-luc human NSCLC PDC into brains of female BALB/c nude mice. After anesthetization, mice were immobilized with a stereotactic apparatus for incision of the skull’s right hemisphere. A 0.5 mm burr hole was drilled through the right frontal lobe to implant a guide screw. Next, 5 × 105 cancer cells (diluted in 5 µL PBS) were stereotactically injected for 5 min into the right frontal lobe via the guided screw and the incision was closed with surgical glue. At 13 d post-implantation, when photon flux measured through IVIS reached 1 × 106 photons/second, mice were treated with a daily oral dose of repotrectinib (15 mg/kg, bid), entrectinib (30 mg/kg, qd), lorlatinib (30 mg/kg, qd), and vehicle. Brain metastatic-tumor growth was measured using an IVIS Spectrum Xenogen (Caliper Life Sciences, MA, USA).

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry was performed on 4 µm-thick FFPE tissue sections. Slides were baked, deparaffinized in xylene, passed through graded alcohols, and then antigen retrieved with 1mM EDTA, pH8.0 at 125°C for 30 seconds. Slides were pretreated with Peroxidase Block (Dako USA, Carpentaria, CA) for 5 minutes, and then washed in 50mM Tris-Cl, pH7.4. Slides were blocked using normal goat serum (Dako USA, Carpentaria, CA), and subsequently incubated with anti-phosphSTAT3 monoclonal antibody (Tyr705, D3A2, 1:100; CST)/ anti-Ki67 antibody (D2H10; 1:100) for 1 hour. Slides were then washed in 50mM Tris-Cl, pH7.4 and treated with Signalstain boost IHC detection reagent (HRP, rabbit, #8114, CST) for 30 minutes. After further washing, immunoperoxidase staining was developed using a 3,3’diaminobenzidine (DAB) chromogen (Dako) for 5 min. Slides were counterstained with hematoxylin, dehydrated in graded alcohol and xylene, mounted and coverslipped.

Targeted sequencing

Comprehensive genomic profiling was performed in repeat biopsies in two patients who progressed after repotrectinib. FFPE slides were subjected to Illumina HiSeq based targeted sequencing capturing 171 cancer-related genes. Resultant reads were mapped to the human genome reference (hg19) using Burrows-Wheeler Alignment (BWA) followed by analysis using Genome Analysis ToolKit. Somatic mutations were called using MuTect2 and annotated with Oncotator. FoundationOne® CDx (Foundation medicine, MA, USA) was used to confirm the identified genomic alterations. A whole-genome shotgun library was constructed from 50–1000 ng of extracted DNA and hybrid capture-selected libraries were sequenced at >500× median coverage using the Illumina HiSeq platform. All classes of cancer-related genomic alterations (e.g., base substitutions, indels, rearrangements, and copy-number alterations) were assayed.

Statistics

Statistical analyses were performed in SPSS version 21 and GraphPad Prism 5. All data are expressed as means ± SD or ± SE for three or more independent replications. Between-group differences were evaluated using Student’s t-test, Mann-Whitney test, Kruskal-Wallis with Dunn’s post-hoc test, or ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc test, as appropriate. Significance was set at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Repotrectinib potently inhibits in vitro and in vivo tumor growth in treatment-naïve ROS1-rearranged models

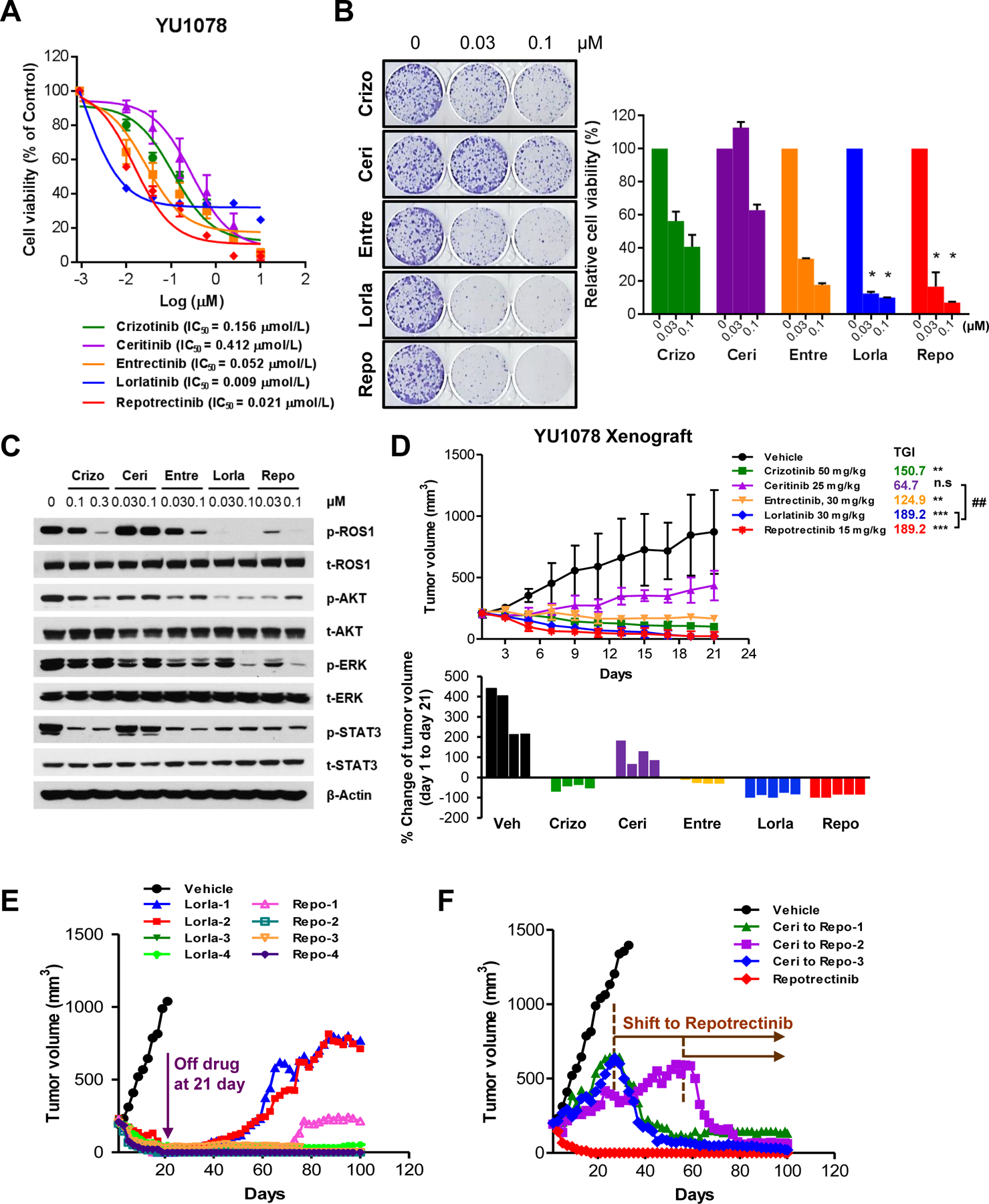

In this study, we established three patient-derived preclinical models including one treatment-naive and two ROS1-TKI-resistant models from ROS1+ NSCLC patients (Table 1). We examined the activities of clinically available ROS1-TKIs including crizotinib, ceritinib, entrectinib, lorlatinib, and repotrectinib in treatment-naive PDC YU1078 cell generated from a ROS1-TKI naïve NSCLC patient with CD74–ROS1(35 years/female). Entrectinib (IC50, 0.052 µM), lorlatinib (IC50, 0.009 µM), and repotrectinib (IC50, 0.021 µM) exhibited potent growth inhibition in YU1078 cells compared with crizotinib (IC50, 0.156 µM) and ceritinib (IC50, 0.412 µM) (Fig. 1A). Colony formation was significantly reduced with lorlatinib and repotrectinib treatment compared with other TKIs (Fig. 1B) and was accompanied by markedly suppressed ROS1 and ERK phosphorylation levels (Fig. 1C).

Figure 1. In vitro and in vivo inhibitory activity of repotrectinib in treatment-naïve ROS1+ patient-derived preclinical models.

A. Cell viability assay of CD74-ROS1 YU1078 treated with ROS1-TKIs for 72 h. B. Colony formation assays involved treatment for 14 d with the indicated dose of ROS1-TKIs; corresponding colony quantification on the right (ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test: *P < 0.05 vs. crizotinib). C. Immunoblots of YU1078 after treatment with indicated crizotinib, ceritinib, entrectinib, lorlatinib, and repotrectinib doses for 6 h. D. Tumor growth of subcutaneous YU1078 xenograft in response to TKI treatment (Kruskal-Wallis with Dunn’s post hoc test: n.s. P > 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs. vehicle. ##P < 0.01 vs. ceritinib. N = 4). Corresponding waterfall plot below represents individual mouse response. E. Tumor growth in individual mice after withdrawal of lorlatinib and repotrectinib at 21 d and F. treatment shift to repotrectinib in ceritinib-treated tumors from D. Data are mean ± SD or ± SE.

Consistent with the in vitro findings, lorlatinib and repotrectinib displayed pronounced tumor regression in subcutaneous YU1078 xenograft model with 189.2% tumor growth inhibition (TGI). Crizotinib and entrectinib resulted in 150.7% and 124.9% TGI, respectively, whereas ceritinib displayed 64.7% TGI (Fig. 1D). Although tumor regression was comparable between lorlatinib and repotrectinib, repotrectinib produced the strongest antitumor effect, which was most apparent after drug withdrawal. After drug withdrawal at 21 d, tumors in three out of four repotrectinib-treated mice were persistently suppressed for over 80 d. One mouse exhibited slow regrowth after 60 d post-drug withdrawal. However, tumors in two out of four lorlatinib-treated mice abruptly re-grew 10 d after drug withdrawal (Fig. 1E). To determine whether repotrectinib is an effective subsequent treatment option after failure to prior ROS1-TKI, we administrated repotrectinib to tumor progressed on ceritinib. Subsequent repotrectinib treatment prominently suppressed tumor growth where of note, upfront repotrectinib completely induced tumor regression (Fig. 1F). Collectively, upfront and subsequent repotrectinib treatment demonstrated potent tumor growth inhibition based on in vitro and in vivo ROS1+ preclinical models.

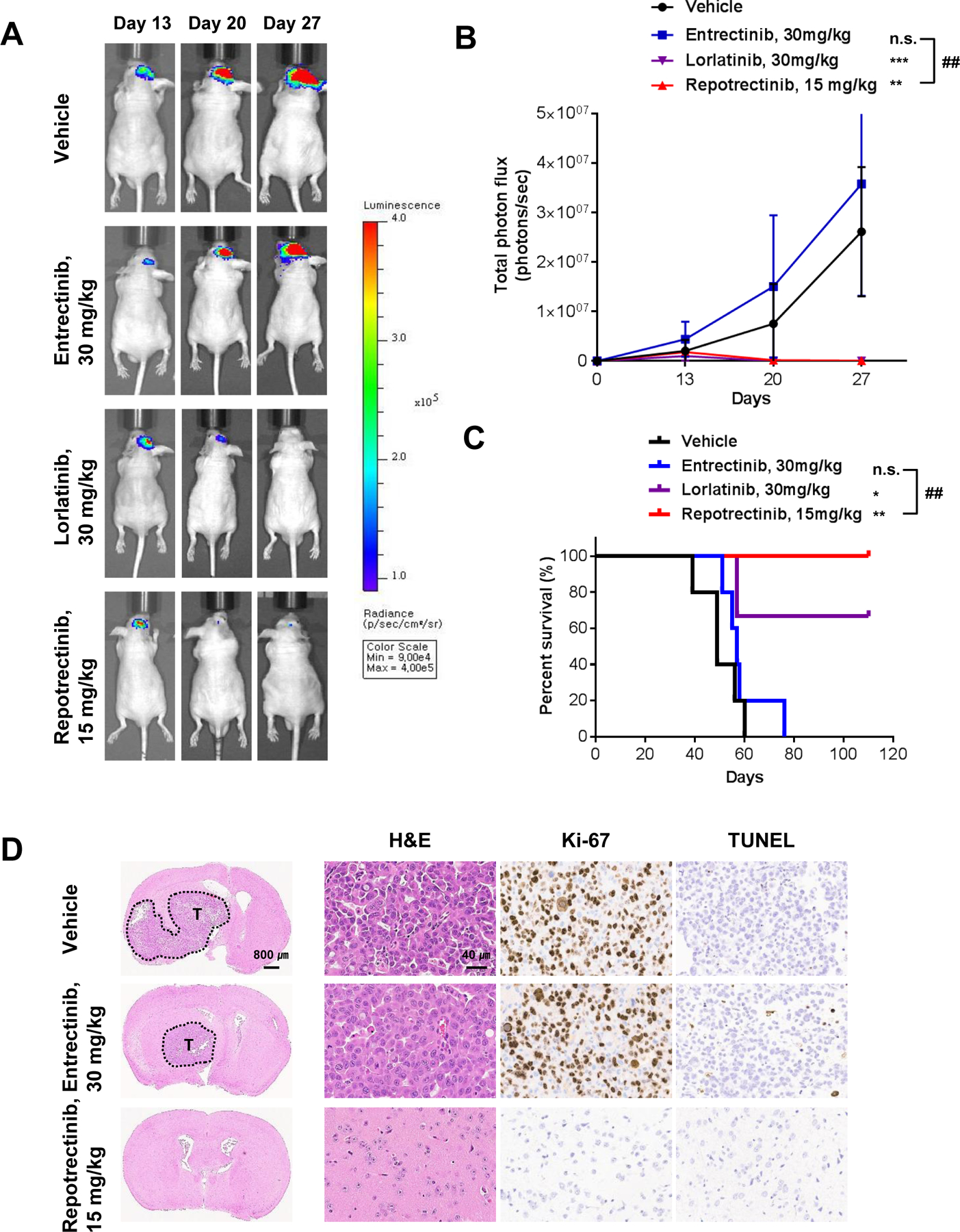

Repotrectinib demonstrates efficient antitumor activity in an intracranial tumor model with a high BBB penetration profile

Lorlatinib and entrectinib have been reported to penetrate the BBB and regress brain metastasis (13–15). We investigated the ability of repotrectinib to penetrate BBB using an intracranial tumor model of luciferase-transduced YU1078 cells (YU1078-luc). Compared with vehicle and entrectinib, repotrectinib treatment significantly reduced tumor load (as measured using photon flux) in the brain without body weight loss (Fig. 2A and 2B). Additionally, all repotrectinib-treated mice survived for up to 110 d, whereas median survival of vehicle- and entrectinib-treated mice was 49 d and 57 d, respectively (Fig. 2C). Lorlatinib showed comparable reduction of tumor load to that of repotrectinib (Fig. 2A and 2B). Immunohistochemistry further revealed that repotrectinib treatment completely suppressed viable brain tumors, with pronounced reduction in Ki67-positive and TUNEL-positive cells compared with vehicle and entrectinib treatment (Fig. 2D).

Figure 2. Antitumor efficacy of repotrectinib in ROS1+ PDC-driven intracranial tumor models.

A. Representative IVIS image of intra-cranial YU1078-luc cells treated with entrectinib once daily, lorlatinib once daily and repotrectinib twice daily. Mice were orally dosed 13 d after intra-cranial injection. B. Average photon count (photons/s) of intra-cranial metastasis over 27 d. Data are mean ± SD. Significance between groups observed at 27 d (Mann-Whitney test: n.s. P > 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs. vehicle. ##P < 0.01 vs. entrectinib. N = 5; lorlatinib N=3). C. Kaplan–Meier survival curve of YU1078-luc injected mice (log-rank test: n.s. P > 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs. vehicle. ##P < 0.01 vs. entrectinib. N = 5; lorlatinib N=3). D. Representative hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), Ki67 and TUNEL staining of brain sections following entrectinib and repotrectinib treatments.

Clinical activity of repotrectinib in ROS1-TKI-naïve and ceritinib-resistant patients

Clinical potency of repotrectinib was demonstrated in a TKI-naïve ROS1+ patient treated with repotrectinib. A 69-year-old female CD74-ROS1-rearranged patient was presented with liver and multiple brain metastasis. After receiving 40 mg repotrectinib once daily on the phase 1 repotrectinib trial, the patient achieved confirmed PR (-80%) based on RECIST1.1, currently ongoing at 20 months (Fig. 3A). The phase 1 repotrectinib trial also included a ROS1+ lung cancer patient who had recurred under ceritinib. Pre-repotrectinib brain imaging revealed multiple asymptomatic brain metastases. This patient tolerated repotrectinib treatment (40–240 mg qd) and achieved confirmed RECIST1.1-based PR (-40%) that is ongoing at 16 months (Fig. 3B). As a clinical proof of concept, the potent intracranial activity of repotrectinib has been observed in TKI-naïve patient and patient who had progressed on prior TKI enrolled in on-going phase 1/2 clinical trial. Multiple metastatic brain lesions disappeared after 2-month treatment and were maintained over 15 months in each patient.

Figure 3. Favorable response to repotrectinib in ROS1-TKI treatment-naïve and ceritinib-resistant patients.

A. Confirmed partial response in a CD74-ROS1 NSCLC patient based on RECIST 1.1 of hepatic and brain metastasis, after treatment with 40 mg repotrectinib once daily at 2 months and 16 months. B. Confirmed partial response of lung and brain metastasis in a CD74-ROS1 NSCLC patient who progressed on ceritinib, after treatment with 40 mg (increased to 240 mg) repotrectinib once daily. Red circles and yellow arrows indicate areas of metastatic tumor disease.

Repotrectinib overcomes crizotinib-resistant ROS1 G2032R

We identified the ROS1-G2032R mutation in YU1079, which was serially established in the same patient as YU1078 but after progressing on crizotinib treatment. Based on recent studies examining lorlatinib and cabozantinib in Ba/F3 cells engineered with CD74–ROS1G2032R (10,13), we investigated these TKIs in our YU1079 with CD74-ROS1G2032R. Cabozantinib (IC50, 0.111 μM) and repotrectinib (IC50, 0.097 μM) effectively inhibited YU1079 ROS1G2032R growth, concomitant with marked reduction in ROS1 and downstream signal phosphorylation (Fig. 4A-4C). However, lorlatinib (IC50, 1.509 μM) was relatively ineffective in inhibiting YU1079 ROS1G2032R growth, possibly due to a weak inhibitory effect on phospho-ROS1, ERK, and STAT3, along with persistent phospho-AKT (Fig. 4C).

Figure 4. Antitumor efficacy of repotrectinib against crizotinib-resistant ROS1 solvent-front mutation G2032R.

A. Cell viability assay of CD74-ROS1 G2032R-mutant YU1079 treated with ROS1-TKIs for 72 h. B. Colony formation assays involved treatment for 14 d with the indicated dose of ROS1-TKIs; corresponding colony quantification on the right (ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test: *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001 vs. crizotinib. #P < 0.05 vs. cabozantinib). C. Immunoblots of YU1079 after 6 h treatment with indicated crizotinib, lorlatinib, cabozantinib, and repotrectinib doses. D. Tumor growth of YU1079 xenograft in response to TKI treatment (Kruskal-Wallis with Dunn’s post hoc test: n.s. P > 0.05, ***P < 0.001 vs. vehicle. #P < 0.05, ###P < 0.001 vs. lorlatinib. N = 5). Corresponding waterfall plot on the right represents individual mouse response. E. Tumor growth of PDX model YHIM1047 harboring CD74-ROS1 G2032R mutation (N = 5) treated with entrectinib and repotrectinib. Corresponding waterfall plot on the right represents individual mouse response. F. Representative Ki67 and pSTAT3 staining of tumor sections following entrectinib and repotrectinib treatments. Data are mean ± SD or ± SE. G. Confirmed partial response in a CD74-ROS1 G2032R mutant NSCLC patient who progressed on crizotinib based on RECIST 1.1, after treatment with 160 mg repotrectinib twice daily at 2 months and 6 months. Red circles indicate areas of metastatic disease.

The in vivo efficacy of these TKIs was further evaluated in YU1079 ROS1G2032R PDX model. Consistent with the in vitro assays, cabozantinib and repotrectinib significantly led to 102.1% and 90.9% TGI, respectively, compared with 22.7% TGI for lorlatinib (Fig. 4D). Considering severe treatment-related toxicities observed in patients receiving cabozantinib (1,16,17), we focused on comparing repotrectinib with clinically available entrectinib in the PDX model YHIM1047 ROS1G2032R, established from a CD74-ROS1 NSCLC patient who progressed on entrectinib. As expected from the patient’s clinical response, entrectinib failed to inhibit tumor growth whereas repotrectinib treatment induced 142.8% TGI (Fig. 4E). Immunohistochemistry revealed marked reduction of phosphorylated STAT3 and Ki-67 in repotrectinib-treated YHIM1047 ROS1G2032R tumors compared with entrectinib and vehicle (Fig. 4F).

The clinical activity of repotrectinib against ROS1 SFM was seen in a 49-year-old female ROS1-rearranged patient who progressed after 44 months of crizotinib treatment with an identified CD74-ROS1 G2032R mutation. The patient received 160mg BID repotrectinib which induced a confirmed PR (-80%) based on RECIST1.1 currently ongoing at 6 months (Fig 4G). Taken together, these results suggest that repotrectinib is a promising therapeutic strategy for ROS1-rearranged NSCLC harboring ROS1G2032R.

Genetic alterations in ROS1-rearranged patients who progressed on repotrectinib

Finally, we investigated genetic mutation status in biopsies of two patients who progressed on repotrectinib in clinical trial using targeted sequencing. Patient A, a 46-year-old male with a 20 pack-year smoking history, was diagnosed with adenocarcinoma. The patient underwent a first biopsy before treatment, followed by a second biopsy after progression on repotrectinib treatment for about 10 months (Table 1). A variant of the ROS1 translocation, CD74-ROS1 fusion, was detected by targeted sequencing. Mutations in the ROS1 kinase domain were not detected. Post-repotrectinib tumor biopsy had mutations in CCND3 (E253Q), TP53 (H178Q&H179Y) and SMAD4 (E538*) which were absent in the corresponding baseline biopsy (Table S1). These mutations occurred at different variant allele frequencies (VAF), 7%, 53% and 47%, respectively. Patient B was a 38-year-old female with adenocarcinoma and had 10 pack-year smoking history. The patient was biopsied following progression on repotrectinib after 10 months of treatment (Table 1). ROS1 fusion partner was identified as SLC34A2. We identified CEBPA (196_197insHP, VAF 41%), RB1 (H555R, VAF 45%), ERBB2 (R143Q, VAF 51%), and TP53 (E171G, VAF 9%) mutations in the post- repotrectinib tumor biopsy. We were unable to demonstrate the absence of these mutations in the baseline biopsy due to lack of available tumor tissue. Altogether, these findings suggest the possibility of non-ROS1 dominant mechanism as acquired resistance to repotrectinib. Further studies are necessary to investigate the functional role of these mutations to elucidate acquired resistance mechanism to repotrectinib.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we demonstrated that repotrectinib is a potent next-generation TKI against ROS1 and ROS1 G2032R mutation with remarkable activity in the CNS. Our findings highlight the potential of repotrectinib as a first-line in ROS1+ NSCLC as well as those with G2032R.

Crizotinib is the FDA-approved standard care in ROS1-rearranged NSCLC with entrectinib emerging as a promising ROS1-TKI recently approved by the FDA. Ceritinib and lorlatinib have both previously showed clinical activity in treatment-naïve ROS1+ NSCLC (8,18). In particular, lorlatinib is the only recommended TKI after progression to crizotinib under NCCN guidelines (19). To our knowledge, repotrectinib exhibited the most potent in vitro and in vivo activity compared with other ROS1-TKIs in treatment-naïve YU1078 model (Fig 1A-D). Despite comparable activity between repotrectinib and lorlatinib, repotrectinib was able to persistently and strongly suppress tumor recurrence in YU1078-derived xenograft model for more than 80 days even after drug withdrawal (Fig 1E). Consistent with previous reports (10), our findings suggest that repotrectinib is a potent ROS1-TKI in the first-line setting.

CNS metastases remain a major cause of morbidity and mortality in ROS1-driven NSCLC. Recent reports highlighted that 36% of ROS1+ patients experience CNS metastasis at baseline or 50% after crizotinib treatment similar to ALK+ NSCLC (9). The low brain to plasma ratio of crizotinib suggests that frequent CNS metastasis during crizotinib treatment may be due to poor BBB penetration and brain exposure (6). For the first time, we demonstrated superior CNS penetration of repotrectinib compared with entrectinib in YU1078-luc intracranial tumor model with significant reduction of metastatic brain lesion and extensive mouse survival over 100 days (Fig. 2). This was clinically supported by two CD74-ROS1 NSCLC patient response data where repotrectinib rapidly regressed tumor and the metastatic brain lesion (Fig. 3). Therefore, upfront repotrectinib therapy could effectively reduce dismal prognosis due to CNS progression, which might overcome current limitations of first-line crizotinib.

Acquired resistance to targeted therapy is a major obstacle for achieving durable response in oncogene-driven NSCLC. Approximately 50–60% of acquired resistance to crizotinib is caused by on-target mutations, of which G2032R is the most recalcitrant and commonly observed mutation in ROS1+ patients. Ceritinib, entrectinib and lorlatinib did not show robust activity against G2032R, as previously reported (10,13). Cabozantinib exhibited comparable activity to repotrectinib but toxicity observed in clinical trials should be managed further (16). Recently, a novel ROS1/NTRK inhibitor DS-6051b was reported to have activity against G2032R in preclinical models but requires validation in the clinical setting (20). Consistent with previous reports demonstrating the activity of repotrectinib in BaF3 CD74–ROS1G2032R cell line and xenograft models (10), we demonstrated prominent anti-tumor activity of repotrectinib in crizotinib-refractory YU1079 ROS1G2032R and entrectinib-refractory YHIM1047 ROS1G2032R. This was supported by pronounced tumor regression in CD74-ROS1 G2032R NSCLC patient (Fig. 4). Recently, preliminary result of TRIDENT1 trial reported meaningful clinical activity and favorable safety profiles of repotrectinib (21,22). The confirmed objective response rate (ORR) was 82% in 11 TKI-naïve ROS1+ NSCLC patients and 39% in 18 TKI-pretreated patients after repotrectinib. ROS1 G2032R patients demonstrated ORR 40% (n=2/5). Most AEs were manageable and grade 1–2. Collectively, repotrectinib is an effective therapy against TKI-refractory ROS1+ NSCLC harboring G2032R.

Upfront next-generation TKI therapy prolonged survival outcome in EGFR-mut and ALK-fusion NSCLC patients and have been approved as standard care in these patients (23,24). Moreover, recent study presented that sequential ALK-TKI treatment fosters development of diverse compound mutations, highly refractory to all available ALK-inhibitors (25). These data implicate that upfront use of repotrectinib could be able to prevent or delay the emergence of G2032R and subsequent compound mutations, potentially improving clinical outcomes. In line with the idea, G2032R or ROS1 compound mutation was not observed in two patients who progressed on first-line repotrectinib in our study (Table S1). Therefore, optimal first-line therapy could be derived from repotrectinib based combinations to prevent both ROS1-dependent and –independent resistance. Although randomized trials evaluating safety, dosing and efficacy of first-line repotrectinib are necessary, potent overall and intracranial activity, G2032R specificity, and favorable safety profiles suggest repotrectinib as a promising first-line TKI.

In conclusion, we demonstrated that repotrectinib is a novel, highly potent, BBB-penetrant next-generation ROS1/TRK/ALK-TKI. Our findings provide evidence for repotrectinib as an effective first-line treatment in ROS1+ NSCLC and after progression to prior ROS1-TKI.

Supplementary Material

Translational Relevance.

We report repotrectinib, a novel next-generation ROS1-TKI as a potent inhibitor against ROS1 and recalcitrant crizotinib-resistant G2032R mutation with efficient activity in the CNS. Repotrectinib demonstrated potent anti-tumor activity compared with clinically available crizotinib, ceritinib, entrectinib and lorlatinib in preclinical studies and showed efficient penetration of the BBB with improved survival in brain-metastatic mouse models. These results were confirmed by clinical responses in treatment-naïve and crizotinib-resistant G2032R ROS1+ NSCLC patients. Therefore, repotrectinib could serve as an effective first-line treatment in ROS1+ NSCLC, including those with G2032R solvent-front mutation.

Acknowledgements:

We thank all the patients who participated in this study. This research was supported by Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Science, ICT & Future Planning (2016R1A2B3016282 to BC Cho) and NRF grant funded by the Korean government (NRF-2018R1D1A1B07050233 to MR Yun).

Footnotes

Conflicts of interests: The authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lin JJ, Shaw AT. Recent Advances in Targeting ROS1 in Lung Cancer. J Thorac Oncol 2017;12:1611–25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim HR, Lim SM, Kim HJ, Hwang SK, Park JK, Shin E, et al. The frequency and impact of ROS1 rearrangement on clinical outcomes in never smokers with lung adenocarcinoma. Ann Oncol 2013;24:2364–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Song A, Kim TM, Kim DW, Kim S, Keam B, Lee SH, et al. Molecular Changes Associated with Acquired Resistance to Crizotinib in ROS1-Rearranged Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2015;21:2379–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schram AM, Chang MT, Jonsson P, Drilon A. Fusions in solid tumours: diagnostic strategies, targeted therapy, and acquired resistance. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2017;14:735–48 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rotow J, Bivona TG. Understanding and targeting resistance mechanisms in NSCLC. Nat Rev Cancer 2017;17:637–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gainor JF, Tseng D, Yoda S, Dagogo-Jack I, Friboulet L, Lin JJ, et al. Patterns of Metastatic Spread and Mechanisms of Resistance to Crizotinib in ROS1-Positive Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. JCO Precis Oncol 2017;2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Park S, Ahn BC, Lim SW, Sun JM, Kim HR, Hong MH, et al. Characteristics and Outcome of ROS1-Positive Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Patients in Routine Clinical Practice. J Thorac Oncol 2018;13:1373–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lim SM, Kim HR, Lee JS, Lee KH, Lee YG, Min YJ, et al. Open-Label, Multicenter, Phase II Study of Ceritinib in Patients With Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer Harboring ROS1 Rearrangement. J Clin Oncol 2017;35:2613–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Patil T, Smith DE, Bunn PA, Aisner DL, Le AT, Hancock M, et al. The Incidence of Brain Metastases in Stage IV ROS1-Rearranged Non–Small Cell Lung Cancer and Rate of Central Nervous System Progression on Crizotinib. Journal of Thoracic Oncology 2018;13:1717–26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Drilon A, Ou SI, Cho BC, Kim DW, Lee J, Lin JJ, et al. Repotrectinib (TPX-0005) Is a Next-Generation ROS1/TRK/ALK Inhibitor That Potently Inhibits ROS1/TRK/ALK Solvent- Front Mutations. Cancer Discov 2018;8:1227–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim S-Y, Lee JY, Kim DH, Joo HS, Yun MR, Jung D, et al. Patient-Derived Cells to Guide Targeted Therapy for Advanced Lung Adenocarcinoma. Scientific Reports 2019;9:19909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kang HN, Choi JW, Shim HS, Kim J, Kim DJ, Lee CY, et al. Establishment of a platform of non-small-cell lung cancer patient-derived xenografts with clinical and genomic annotation. Lung Cancer 2018;124:168–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zou HY, Li Q, Engstrom LD, West M, Appleman V, Wong KA, et al. PF-06463922 is a potent and selective next-generation ROS1/ALK inhibitor capable of blocking crizotinib-resistant ROS1 mutations. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2015;112:3493–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Solomon BJ, Besse B, Bauer TM, Felip E, Soo RA, Camidge DR, et al. Lorlatinib in patients with ALK-positive non-small-cell lung cancer: results from a global phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol 2018;19:1654–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ardini E, Menichincheri M, Banfi P, Bosotti R, De Ponti C, Pulci R, et al. Entrectinib, a Pan-TRK, ROS1, and ALK Inhibitor with Activity in Multiple Molecularly Defined Cancer Indications. Mol Cancer Ther 2016;15:628–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Drilon A, Rekhtman N, Arcila M, Wang L, Ni A, Albano M, et al. Cabozantinib in patients with advanced RET-rearranged non-small-cell lung cancer: an open-label, single-centre, phase 2, single-arm trial. Lancet Oncol 2016;17:1653–60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guisier F, Piton N, Salaun M, Thiberville L. ROS1-rearranged NSCLC With Secondary Resistance Mutation: Case Report and Current Perspectives. Clinical Lung Cancer 2019;20:e593–e6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shaw AT, Felip E, Bauer TM, Besse B, Navarro A, Postel-Vinay S, et al. Lorlatinib in non-small-cell lung cancer with ALK or ROS1 rearrangement: an international, multicentre, open-label, single-arm first-in-man phase 1 trial. Lancet Oncol 2017;18:1590–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ettinger DS, Wood DE, Aggarwal C, Aisner DL, Akerley W, Bauman J, et al. Non-small cell lung cancer, version 2.2020, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology; 2020. Avaliable from: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/nscl.pdf.

- 20.Katayama R, Gong B, Togashi N, Miyamoto M, Kiga M, Iwasaki S, et al. The new-generation selective ROS1/NTRK inhibitor DS-6051b overcomes crizotinib resistant ROS1-G2032R mutation in preclinical models. Nature Communications 2019;10:3604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cho BC, Drilon AE, Doebele RC, Kim D-W, Lin JJ, Lee J, et al. Safety and preliminary clinical activity of repotrectinib in patients with advanced ROS1 fusion-positive non-small cell lung cancer (TRIDENT-1 study). Journal of Clinical Oncology 2019;37:9011- [Google Scholar]

- 22.Drilon A, Cho BC, Kim D-W, Lee J, Lin JJ, Zhu V, et al. 444PDSafety and preliminary clinical activity of repotrectinib in patients with advanced ROS1/TRK fusion-positive solid tumors (TRIDENT-1 study). Annals of Oncology 2019;30

- 23.Soria JC, Ohe Y, Vansteenkiste J, Reungwetwattana T, Chewaskulyong B, Lee KH, et al. Osimertinib in Untreated EGFR-Mutated Advanced Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med 2018;378:113–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peters S, Camidge DR, Shaw AT, Gadgeel S, Ahn JS, Kim DW, et al. Alectinib versus Crizotinib in Untreated ALK-Positive Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med 2017;377:829–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yoda S, Lin JJ, Lawrence MS, Burke BJ, Friboulet L, Langenbucher A, et al. Sequential ALK Inhibitors Can Select for Lorlatinib-Resistant Compound ALK Mutations in ALK-Positive Lung Cancer. Cancer Discovery 2018:CD-17-1256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.