Abstract

Phosphate is one of the most costly and complex environmental pollutants that leads to eutrophication, which decreases water quality and access to clean water. Among different adsorbents, biochar is one of the promising adsorbents for phosphate removal as well as heavy metal removal from an aqueous solution. In this study, biochar was impregnated with nano zinc oxide in the presence of glycine betaine. The Zinc Oxide Betaine-Modified Biochar Nanocomposites (ZnOBBNC) proved to be an excellent adsorbent for the removal of phosphate, exhibiting a maximum adsorption capacity of phosphate (265.5 mg. g−1) and fast adsorption kinetics (~100% removal at 15 min at 10 mg. L−1 phosphate and 3 g. L−1 nanocomposite dosage) in phosphate solution. The synthesis of these benign ZnOBBNC involves a process that is eco-friendly and economically feasible. From material characterization, we found that the ZnOBBNC has ~20–30 nm particle size, high surface area (100.01 m2. g−1), microporous (25.79 Å) structures, and 7.64% zinc content. The influence of pH (2–10), coexisting anions (Cl, , and), initial phosphate concentration (10–500 mg. L−1), and ZnOBBNC dosage (0.5–5 g. L−1) were investigated in batch experiments. From the adsorption isotherms data, the adsorption of phosphate using ZnOBBNC followed Langmuir isotherm (), confirming the mono-layered adsorption mechanism. The kinetic studies showed that the phosphate adsorption using ZnOBBNC followed the pseudo-second-order model (), confirming the chemisorption adsorption mechanism with inner-sphere complexion. Our results demonstrated ZnOBBNC as a suitable, competitive candidate for phosphate removal from both mock lab-prepared and real field-collected wastewater samples when compared to commercial nanocomposites.

Keywords: Biochar, Betaine HCl, Ammonium zinc carbonate, Zinc oxide, Phosphate, Adsorption

1. Introduction

The World Health Organization reported that about 2.1 billion people lacked access to safe drinking water in 2018. A lack of sanitation facilities leads to this problem in various regions of the globe. Sources of fresh water, such as lakes and streams, are vulnerable to pollutants, and they are becoming a significant concern worldwide (WHO, 2018).

Phosphate is a non-renewable inorganic salt that is used in fertilizers to increase the production of crops. Excess amounts of phosphate in the soil, which may leach out through rainwater and make their way into water resources, can cause ecological effects like eutrophication (decaying of algae), hypoxia (decreased oxygen level in aquatic plants), and impact the water quality (Blaney et al., 2007). Eutrophication can be driven by phosphorous concentrations as low as 100 μg. L−1 (Blaney et al., 2007). The heavy amount of growth of blue-green algae and hyacinth-like plants can produce short or long term environmental effects (Bektaş et al., 2004). The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (US EPA) suggests that total P in streams or other flowing waters do not exceed 0.10 mg. L−1 and 0.05 mg. L−1 in any stream that reaches lakes or reservoirs (Polomski et al., 2009). There are different methods currently used for the removal of phosphate ions from surface water, such as sediment dredging, phosphate inactivation, hypolimnetic aeration/withdrawal. However, these techniques are not useful in the long term and cost-effective. Besides, these techniques also increase the disturbance in the ecosystem (Ritt et al., 2019). Phosphate remediation is an incredibly complex and costly environmental problem, which will cost $298.1 billion for treatment utilizing traditional wastewater treatment plants, to satisfy the standards of the US EPA (EPA, 2008).

Biochar is one of the adsorbents that can be used for the removal of phosphate from aqueous solutions. Biochar is a highly aromatic, carbon-rich solid material, which is produced by low-cost and relatively low temperature pyrolysis from a renewable resource or waste materials like wood chips, rice straw, dried leaves, etc. (Yang et al., 2019), (Liu et al., 2019a, 2019b, 2019c). The biochar is utilized for sequestering carbon, treatment of contaminants, improvement of soil fertility, and recycling of agricultural by-products. The pyrolysis temperature, residence time, heat transfer rate and feedstock types are the main parameters that control the biochar’s properties. The production and storage of the biochar in soils help to improve soil quality and thereby to increase the yield of the crops and decrease climate change by carbon sequestration (Woolf et al., 2010). The removal of contamination depends on the properties of biochar, such as pore size distribution, ion-exchange capacity, and high surface area (Ahmad et al., 2014). Biochar can also improve the plant growth and soil quality by providing essential elements like phosphorous, nitrogen, and other minerals, and by increasing soil pH, respectively.

Several research reported the removal of phosphate using different adsorbents including H2O2 oxidized wood (Mia et al., 2017), biochar-derived organic matter (BDOM) (Mia et al., 2017), anaerobically digested sugar beet tailing (DSTC) (Yao et al., 2011), La (III)-, Ce (III)- and Fe (III) derived orange waste biochar (Biswas et al., 2007). The La (III)-, Ce (III)- and Fe (III) derived orange waste biochar waste incapacitated with zirconium (IV) rice straw and swine modified with MgCl2 (Luo et al., 2019), Douglas fir biochar (695 mg2. G−1) modified to magnetite (Fe2O4) nanoparticles (MBC) (Karunanayake et al., 2019).

Biochar was applied to remove different contaminants such as atrazine (Jablonowski et al., 2013), 1,3-dichloropropene (Wang et al., 2016a, 2016b), Pb (II) (Yan et al., 2015), etc. Though there are few studies on the application of biochar on phosphate removal such as Mg/Al-layered double hydroxides (Mg/Al-LDHs) modified biochar (Li et al., 2016), Lanthanum (La)-biochar (Wang et al., 2015), biochar/Mg–Al assembled nanocomposites (Jung et al., 2015a, 2015b), IT Laminaria japonica & IT-derived biochar (Jung et al., 2015a, 2015b), copper oxide biochar (Liu et al., 2019a, 2019b, 2019c), vegetable biochar/layered double oxides (Zhang et al., 2019), as far of our knowledge, there has not been a reported application of zinc oxide-coated wood char for the removal of phosphate from real field water sources.

There is still a need for a water purification media made up of excellent biochar adsorbent that removes phosphate and still efficient in the presence of other contaminants from water. Also, there is a challenge to develop a cheap, effective, versatile, and benign adsorbent. No adsorbent currently exists that satisfies all the above properties. Several commercial adsorbents exist that exhibit one or more of the desirable properties named above, but the search for an extremely versatile composition that supersedes the existing varieties of products has alluded researchers so far.

Herein, we report the preparation and the characterization of ZnOBBNC for phosphate removal from the aqueous solutions. The main objectives of this research were 1) to synthesize ZnOBBNC, 2) to characterize microscopically and spectroscopically ZnOBBNC and phosphate-adsorbed ZnOBBNC, and 3) to study the adsorption of phosphate from water and desorption of phosphate from ZnOBBNC, 4) to investigate the anionic competitive effects, and 5) to test the potential of the ZnOBBNC for phosphate removal using real field-collected water from Adams Field Little Rock Water Reclamation Authority (Little Rock, Arkansas) and the creek of the University of Arkansas at Little Rock.

2. Experimental section

2.1. Materials and methods

Biochar and ammonium zinc carbonate were donated for research by Oregon Biochar Solutions (White City, Oregon) and the Mineral Research and Development Company (Harrisburg, North Carolina), respectively. Betaine HCl was purchased from Nutricost (Lindon, Utah) and used as received. Potassium dihydrogen phosphate (KH2PO4), sulfuric acid (H2SO4), ammonium molybdate, potassium antimonyl tartrate, ascorbic acid, hydrochloric acid (HCl), sodium hydroxide (NaOH), potassium chloride (KCl), sodium chloride (NaCl), potassium nitrate (KNO3), sodium sulfate (Na2SO4), sodium carbonate (Na2CO3) were purchased from the ACROS Organic-Fisher Scientific (New Jersey, USA). Ultra-pure deionized (DI) water was used for all syntheses and experiments.

2.2. Preparation of zinc oxide betaine-modified biochar nanocomposites (ZnOBBNC)

Zinc oxide betaine-modified biochar nanocomposites (ZnOBBNC) were prepared using our recent patented technology (Viswanathan, 2020). Briefly, the nanocomposite glycine betaine was used as a quaternizing agent. Ammonium zinc carbonate (AZnC) was utilized as the alkaline metal salt (consists of 15% zinc oxide) for the synthesis of the ZnOBBNC. Betaine HCl (7.68 g) was dissolved in 25 mL of deionized (DI) water in a beaker and mixed with 25 g of biochar powder. The mixture was allowed to stand for 30 min. Then, 20.4 g of alkaline metal salt was added into it and mixed well. The product was set aside for 30 min before heating in a convection oven for 8 h at 80 °C (Viswanathan, 2020). The scheme of synthesis is given below: (See Scheme 1).

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of ZnOBBNC.

ZnOBBNC were compared with biochar control, betaine-modified biochar, and zinc oxide-modified biochar. The betaine-modified biochar was prepared using the same amount of betaine HCl and was treated with the same amount of biochar. At the same time, the zinc oxide modified biochar was fabricated using ammonium zinc carbonate treated with biochar. The preparation method was like the method described above for the ZnOBBNC.

2.3. Batch adsorption experiments

A phosphate stock solution (500 mg. L−1) was prepared by dissolving 2.20 g of KH2PO4 crystals (from now on called phosphate) in 1000 mL of DI water at room temperature in a 1000 mL volumetric flask. The stock solution was then diluted separately to 10–400 mg. L−1 of the solution in a 500 mL volumetric flask. The pH of all phosphate concentrated solutions was adjusted to pH seven by adding 0.1 M of NaOH or 0.1 M of HCl.

The adsorption experiment was performed in a 125 mL Erlenmeyer flask at room temperature (25 ± 0.5 °C). The ZnOBBNC (3 g. L−1) were treated with 100 mL of different phosphate solutions separately for different time intervals between 0.083 and 24 h. To determine the optimal adsorbent dosage, the adsorption experiments were conducted by adding 100 mL of 100 mg L−1 of phosphate solution with a various adsorbent dosages of 0.5 g. L−1 to 5 g. L−1 using the previous method (Guzman et al., 2012), (Ramasahayam et al., 2012). Aliquots from each experiment were collected at different time intervals and filtered through the glass wool filter. The pH of each phosphate solution after treatment was measured by a pH meter, and it was found to be ~6.55 in all cases. The ascorbic acid method (100 mL of ascorbic acid reagent was prepared by mixing 50 mL of 5 N sulfuric acid, 5 mL of potassium antimonyl tartrate, 15 mL of ammonium molybdate and 30 mL of ascorbic acid in a 100 mL volumetric flask) was used to resolve the phosphate removal in each stock solution (EPA 365.1, 1993). Each aliquot was diluted to 200 μg. L−1 of phosphate solution by adding DI water to a final volume of 50 mL. Each aliquot was then treated with 8 mL of ascorbic acid reagent and set aside for 15 min for color development (EPA 365.2, 1983), (EPA 365.3, 1978). A Thermos-Scientific Spectronic 200 Visible spectroscopy equipment was employed to analyze the data from the above experiment at 880 nm, with the blank and phosphate standard solution treated with the ascorbic acid reagent similar to the above sample. The DI water and phosphate stock solution were utilized as a blank and standard solution for the phosphate determination, respectively. All the experiments were performed in triplicate and average data with error bar is reported.

The batch experiment of influence of pH range, and coexisting anions, were performed using ZnOBBNC to determine the inhibitory effect of various pH ranges, and various coexisting anions on phosphate removal by ZnOBBNC. The details of the experimental process is mentioned in supplementary material appendix SI-1.

The ionic strength and pHpzc of ZnOBBNC were performed using ZnOBBNC to determine a complex formation during phosphate adsorption. The details of the experimental process is mentioned on supplementary material appendix SI-1.

2.4. Metal content in ZnOBBNC adsorbent

Two g of washed ZnOBBNC, and unwashed ZnOBBNC separately were ignited in a crucible cup for in a muffle furnace at 900 °C 24 h. After 24 h, the remaining residue was cooled and weighed. The metal content of each sample was determined from the initial and final weight of the respective sample. The formula used to calculate metal content is given below:

Where 0.803 is a metal factor for zinc (Nakarmi et al., 2018). From this experiment, the zinc content of ZnOBBNC before and after washing were found to be 7.64% and 7.04%, respectively. The theoretical value of zinc content in the prepared ZnOBBNC was found to be 7.32%, which was calculated by the mole concept method. Without applying of metal factor (0.803), the residual values for unwashed and washed ZnOBBNC were found to be 9.48% and 8.77%, respectively.

2.5. Adsorption isotherms and kinetic models

Langmuir, Freundlich, Temkin and Dubinin-Radushkevich isotherms were chosen to study the adsorption mechanism phosphate on ZnOBBNC. The Langmuir adsorption isotherm describes the monolayer adsorption process of the adsorbate-adsorbent system, whereas the Freundlich isotherm explains the heterogeneous surface adsorption mechanism (Micháleková-Richveisová et al., 2017 ), (Park et al., 2016). Temkin isotherm explains a uniform distribution of the binding energy of adsorbent-adsorbate, while D-R Isotherm describes the adsorption mechanism with Gaussian energy distribution on the heterogeneous surface.

Similarly, the Lagergren pseudo-first and second-order kinetics, Elovich equation and Weber-Morris models were chosen to investigate the adsorption mechanism of the phosphate on ZnOBBNC. The physical adsorption of phosphate on the adsorbent is explained by Lagergren pseudo-first-order, while the Lagergren pseudo-second-order illustrates the chemical adsorption of phosphate on the adsorbent (Liu et al., 2020), (Kołodyńska et al., 2017 ). Elovich equation also explains chemisorption, while Weber-Morris model provides information about an intra-particle diffusion as the rate-controlling step. Unlike chemisorption, in physical adsorption, chemical bonds are not formed, but there is the loose bonding between the adsorbent and the adsorbate on the surface of the adsorbent. The quaternary ammonium group (positively charged) of betaine present on the surface of ZnOBBNC can function as a strong anion exchanger. This positively charged group can attract negatively charged phosphate ions in the aqueous solutions resulting in the removal of phosphate. Another possible mechanism can occur during phosphate removal due to the chemisorption on metal oxides. The transition metals might be present in nanostructures with a high surface area. Surface adsorption of the anions might take place through the interaction of the anions with “d” orbitals present on the metal oxide. This chemical bonding could take place independently or synergistically in combination with the anion exchanging groups present on the surface of ZnOBBNC. The role of the cationic groups on the surface of the ZnOBBNC would be to attract the negatively charged phosphate ions. The phosphate ions could attach to the metal oxide nanoparticles because of their proximity to the cationic groups (Viswanathan, 2020). The linear expression of above adsorption isotherms and kinetic models were given in the supplementary material appendix SI-2.

2.6. Material characterization

The powered ZnOBBNC was further analyzed by various instrumental techniques: Environmental Scanning Electron Microscopy (ESEM), High Resolution Transmission Electron Microscopy (HRTEM), X-Ray Diffraction (XRD), X-Ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS), and Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) Surface Area Analysis, Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA), Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FT-IR), Micro-Raman Spectroscopy, and Ion Exchange Chromatography (IEC). Experimental details of these measurements are provided in the supplementary material appendix SI-3.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Characterizations of the nanocomposite specimens

3.1.1. SEM and HRTEM

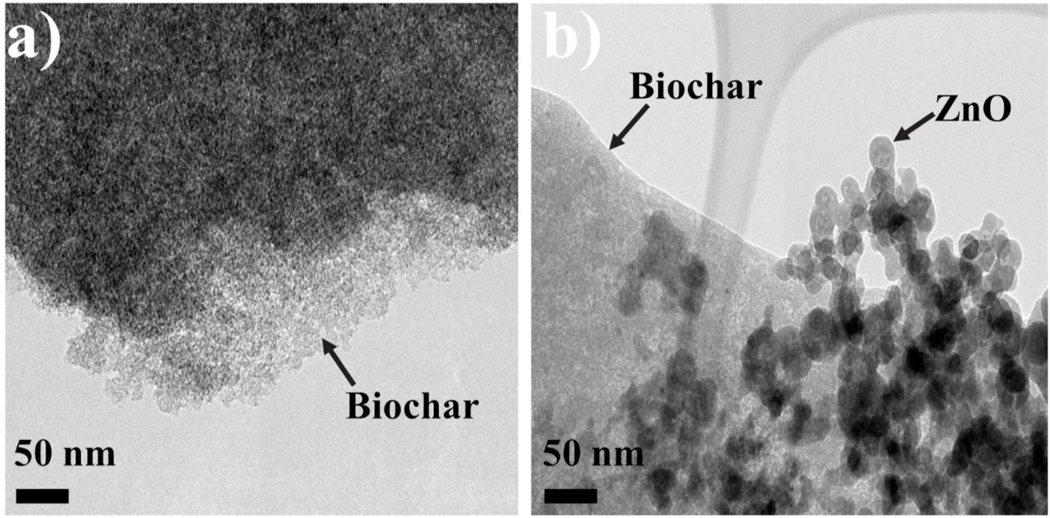

The High Resolution Transmission Electron Microscopy (HRTEM) analysis was performed to investigate the size of composites and ZnO attached to the composites. Fig. 1 displays the HRTEM images of and pure biochar (Fig. 1a) and ZnOBBNC (Fig. 1b). The zinc oxide (pointed out by the arrow) appears spherical in shape and has a size of ~20–30 nm. However, the ZnOBBNC are aggregated, forming a chain-like structure that is attached to surface of biochar (Kanel et al., 2005), (Kanel and Al-Abed, 2011), (Manning et al., 2007). This HRTEM image of ZnOBBNC is similar to a previous report in which ZnO nanoparticles showed a uniform spherical shape (32 nm size) with agglomeration (Jalal et al., 2010).

Fig. 1.

HRTEM images of a) biochar and b) ZnOBBNC.

Figure SI-1 displays the SEM images of ZnOBBNC along with biochar. The SEM image of biochar at 1000x magnification (Figure SI-1a) confirmed the smooth surface of biochar. The SEM image of ZnOBBNC at 1000x magnification (Figure SI-1b) revealed the presence of nanoparticles on the surface of biochar.

3.1.2. X-ray diffractometry (XRD)

Fig. 2 depicts the XRD patterns of ZnOBBNC along with the betaine and biochar controls. The XRD patterns of the ZnOBBNC at 26.38 (010), 29.26 (002), 30.23 (011), 40.33 (012), 47.14 (110), 51.53 (013), and 58.27 (021) two-theta degree confirms the presence of ZnO in hexagonal wurtzite structure. The XRD patterns at 31.07 (100), 33.11 (002), 37.58 (101), and 42.62 (220) two-theta degree demonstrate the presence of ZnO in a cubic zinc blende structure (Akhtar et al., 2012), (Zak et al., 2011). Comparing with the previous report, the XRD patterns of zinc oxide of the ZnOBBNC are similar to the reported patterns (Jalal et al., 2010). The XRD patterns at 12.05, 13.0, 14.46, 19.03, 20.84, 21.67, 23.23, 24.44, and 25.06 two-theta degrees revealed the presence of zinc silicate, which is formed during the reaction of zinc ammonium carbonate with calcium silicate from betaine HCl (Xu et al., 2010), (Ai-yuan et al., 2016). From the Debye-Scherrer equation (supplementary material appendix SI-3), the crystallite size of zinc oxide was estimated to be 8.93 nm for the zinc blende structure and 9.12 nm for the wurtzite structure. The crystallite size of zinc silicate was found to be 34.54 nm.

Fig. 2.

XRD patterns of ZnOBBNC (blue), biochar (black), and betaine-modified biochar (red). (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

The reported size is different from the size of the nanoparticle from HRTEM because HRTEM measures a particle size of the nanoparticle, while the Debye-Scherrer equation derives the crystallite size (single unit cell of the crystal) of the nanoparticle.

3.1.3. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS)

Figure SI-2 represents the XPS survey scan of ZnOBBNC along with the phosphate adsorption and phosphate desorption, which confirm the presence of ZnO at peak Zn2p 1025 eV. The XPS peaks in Figure SI-2 of the ZnOBBNC for the phosphate adsorption obtained after the treatment of 3 g. L−1 ZnOBBNC with 100 mL of 500 mg. L−1 of phosphate solution for 24 h while for phosphate desorption, the XPS peaks obtained after treatment of phosphate adsorbed ZnOBBNC with 100 mL of 0.1 M of NaOH for 4 h, then 100 mL of 0.1 M HCl for 2 h. The atomic% and the weight % of zinc metal were detected to be 9.50 ± 0.37 At.% and 32.31 ± 0.93 wt% for untreated ZnOBBNC, 9.20 ± 0.40 At.%, and 28.74 ± 0.62 wt% for phosphate adsorbed ZnOBBNC, and 0.13 ± 0.01 At.% and 0.68 ± 0.08 wt% for phosphate desorbed ZnOBBNC, respectively. The XPS survey scans also confirmed the presence of C1s, O1s, Cl2p and N1s (Tables SI–1). The phosphate adsorbed ZnOBBNC, and phosphate desorbed ZnOBBNC indicated the presence of a phosphorus element with 10.95 ± 0.75 At. % and 16.19 ± 0.75 wt %, and 0.00 At. % and 0.00 wt %, respectively. Thus, the ZnOBBNC adsorbs phosphate from the solution (500 mg. L−1) and desorb it after treating it with regenerating reagents. However, this data suggest that the ZnOBBNCs are not suitable for multiple uses due to the loss of zinc nanoparticles during the regeneration process, as reflected by the phosphate desorbed XPS survey scan peak (from Figure SI-2).

The weight percentages of zinc after phosphate, adsorption, and phosphate desorption were found to be different from XPS data. So, TGA was performed to get an exact value. Figure SI-3 shows the TGA plot of unwashed ZnOBBNC unwashed (black), washed ZnOBBNC (red), and phosphate adsorbed ZnOBBNC. From this figure SI-3, the weight percentages of each sample were estimated to be 13.52%, 10.86%, and 7.16%, respectively, which are close to the metal content before application of the factor (Nakarmi et al., 2018).

Fig. 3 shows the narrow scan XPS peak of ZnOBBNC contains Zn2p, O1s, C1s, and N1s peaks. The narrow scan of the Zn2p peaks (Fig. 3a), which are composed of one peak with two multiplets, suggests that zinc is in Zn (II) states. The multiplets are distinguished by Zn2p3/2 and Zn2p1/2 (Armelao et al., 2006), (Kamarulzaman et al., 2016), (Simon et al., 2010), which are identified at 1021.51 eV and 1044.51 eV, respectively. The difference in binding energy between each of the spin orbits is found to be around 23 eV which is consistent with ZnO. Fig. 3b and c shows the narrow scan peaks of O1s and C1s peaks: O1s peaks split into three singlets corresponding to (purple), (pink), and (blue) bonds, and C1s peaks split into six singlets showing (blue), (pink), (red), (purple), (green), and pi-pi* satellites (navy) bonds, as illustrated in Tables SI–2. The splitting of the carbon and oxygen peaks confirm the metal oxide bond with the carbon and oxygen atoms of betaine fixated biochar in the ZnOBBNC (Bañuls-ciscar et al., 2016). The narrow scan of the N1s peak (Fig. 3d) exhibit three singlets associated with the (pink), (dark purple), and N+ (orange) bonds, as illustrated in Tables SI–2 (Yang et al., 2014), (Liu et al., 2019a, 2019b, 2019c).

Fig. 3.

XPS scanning of ZnOBBNC: a) Zn2p, b) C1s, c) O1s, and d) N1s peaks.

Figure SI-4 exhibits the plots of nitrogen linear, surface area and pore volume-diameter distribution of ZnOBBNC. More specifically, the surface area and pore size of the ZnOBBNC were found to be 100.01 m2. G−1 and 25.79 Å, respectively, indicating that it has a microporous surface. This value is in agreement with the adsorption mechanism (RanguMagar et al., 2018).

3.1.4. FTIR and Raman Analysis

Figure SI-5 displays the FTIR peaks of ZnOBBNC before and after phosphate adsorption and desorption along with controls, i.e., biochar (black), betaine-modified biochar (red), zinc oxide-modified biochar (blue), phosphate adsorbed ZnOBBNC (green), and phosphate desorbed ZnOBBNC (pink). In this figure, the FTIR peak of betaine-modified biochar associated with the substitution of the N group (-CN stretching) and stretching at ~1244 cm−1 and the peak at ~1420 cm−1 is due to –CO stretching of betaine. The peaks at ~1398 cm-1 and ~1630 cm−1 in ZnOBBNC confirm –CO stretching and –NH bending from betaine. These peaks are different from the peaks of the betaine-modified biochar, which could be due to metal oxide. The peak at ~1004 cm−1 in the ZnOBBNC after phosphate adsorption could be due to phosphate ions (Ritt et al., 2019), (Yavorskyy et al., 2008). However, the peaks at 1400 cm−1 and 1600 cm−1 are missing or less intense in both phosphate adsorption and phosphate desorption, confirming the fact that betaine and metal oxide have been washed away during regeneration (Yao et al., 2011), (Zhang et al., 2019), (Behazin et al., 2016). Figure SI-6 presents the Micro-Raman spectra of ZnOBBNC (black), ZnOBBNC after phosphate adsorption (red), and phosphate desorption (blue). Peaks characteristic to the ZnOBBNC were observed at 1327 cm−1 (D-band) and 1588 cm−1 (G-band). The D-band is indicative of carbonaceous material with aromatic rings, while the G-band is associated with the presence of aromatic ring and bonds (Jia et al., 2017), (Akhavan, 2010).

3.2. Major factors influence on phosphate removal

3.2.1. Influence of initial phosphate concentration

The influence of initial phosphate concentrations (10–500 mg. L−1) were investigated using 3 g. L−1 of the ZnOBBNC at different time intervals between 0.083 and 24 h, as shown in Fig. 4. From the figure, about ~100%, ~85%, ~51%, ~45%, ~30%, ~25%, and ~23% of phosphate removed from the initial concentration of 10, 50, 100, 200, 300, 400, 500 mg. L−1 phosphate, respectively, within 15 min. The removal of phosphate slowly decreased with increasing the initial concentration of phosphate. This maybe due to a decrease in the adsorption sites, which enhance phosphate adsorption. At low concentration, the phosphate removal is faster than that observed in the high concentration, suggesting that the ZnOBBNC is suitable for phosphate removal at low concentration for the aqueous solutions (Nakarmi et al., 2018).

Fig. 4.

Influence of phosphate concentration on ZnOBBNC. Reaction condition: 100 mL of each phosphate solution adsorbed on 3 g. L−1 ZnOBBNC for a reaction time of 0.083–24 h at pH 7.

3.2.2. Influence of adsorbent dosages

The influence of ZnOBBNC dosage (0.5–5 g. L−1) were investigated using the same initial concentration of phosphate (100 mg. L−1) at different time intervals, between 0.083 and 24 h, as shown in Fig. 5. According to the figure, about ~20%, ~22%, ~33%, ~58%, ~61%, and ~67% of phosphate removed from the initial concentration with various dosages of 0.5, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 mg. L−1 of ZnOBBNC, respectively, within 15 min. The result of Fig. 6 showed the increase of phosphate adsorption upon an increase in the dosage of the adsorbent. This is due to the availability of adsorption sites on increasing the dosage of the adsorbent for the same concentration of phosphate solution. Thus, it was concluded that the removal from 5 g. L−1 ZnOBBNC is faster when compared to other dosages (Nakarmi et al., 2018), (Kanel et al., 2006).

Fig. 5.

Influence of dosage of ZnOBBNC. Reaction condition: 100 mL of 100 mg. L−1 phosphate solution adsorbed on 0.5–5 g. L−1 ZnOBBNC for a reaction time of 0.083–24 h at pH 7.

Fig. 6.

A plot of the influence of pH of ZnOBBNC. Reaction condition: 100 mL of 100 mg. L−1 phosphate solution with different pH range (2–10) adsorbed on 3 g. L−1 ZnOBBNC for a reaction time of 24 h.

3.2.3. Influence of pH on phosphate adsorption

Fig. 6 shows the influence of the pH of the solution with ZnOBBNC on the phosphate adsorption process (detail method in supplementary material appendix SI-1). At initial pH 2, the predominant phosphate species were H3PO4, which inhibited the phosphate adsorption. The adsorption capacity at pH 2 was 27.34 mg. g−1, revealing the ZnOBBNC removed very few H3PO4. With an initial pH rise from 2 to 5, the effectiveness of phosphate adsorption (75.01 mg. g−1) improved as the abundance of the ion rose, indicating that ion may improve the affinity adsorbent with the H3PO4. When the initial pH is 7, the maximum phosphate adsorption was reached with an adsorption capacity of 77.91 mg. g−1. The phosphate in the solution was predominantly present in the form of ion, which shows greater affinity for the Zn2+ than other pH values (S. Wang et al., 2018a, 2018b), (Xu et al., 2020). Once the initial pH is at 8, the ZnOBBNC phosphate removal rate begins to decrease (63.79 mg. g−1) and hits the peak at pH 10 (56.63 mg. g−1). Phosphate was primarily in form at high pH. Also, at the high concentration of OH-ions in the solution might inhibit the interaction of the hydroxyl group of ZnOBBNC with ion, leading the competition with the ion in the adsorption solution on the ZnOBBNC surface (Wang et al., 2020).

As shown in Figure SI-7, the pHpzc of the ZnOBBNC was found to be 6.76, indicating the positive charge and negative charge becomes equal (i.e., net zero charge) on the surface of ZnOBBNC at this pH value (detail method in supplementary material appendix SI-1). The surface of ZnOBBNC was positively charged if the pH of the solution was less than pHpzc. In comparison, the ZnOBBNC surface was negatively charged when the pH of the solution was larger than pHpzc (Mahmood et al., 2011).

3.2.4. Influence of coexisting anions and ionic strength on phosphate adsorption

Fig. 7 shows the influence of different coexisting ions, namely, Cl−, , and ions on the phosphate removal of 100 mg. L−1 of phosphate solution by 3 mg. L−1 ZnOBBNC (detail method in supplementary material appendix SI-1). The Cl− ions had a little inhibitory effect on phosphate adsorption and reduced an adsorption capacity from 77.92 mg. g−1 to 72.92 mg. g−1, whereas and ions showed a moderate inhibitory effect and reduced adsorption to 66.60 mg. g−1, and 64.60 mg. g−1 respectively. However, the ions exhibited the highest effect, reduced phosphate adsorption to 61.94 mg. g−1. The decrease in the adsorption capacity may be due to the competitive reaction of coexisting anions with phosphate ions. Wang et al. (2016a, 2016b) reported similar data, validating the result reported in Fig. 7 (Xu et al., 2020), (Wang et al., 2016a, 2016b).

Fig. 7.

A plot of the influence of coexisting anions of ZnOBBNC. Reaction condition: 100 mL of 100 mg. L−1 phosphate solution with 0.01 M of coexisting anions adsorbed on 3 g. L−1 ZnOBBNC for a reaction time of 24 h at pH 7.

There are two possibilities for complex formation during adsorption: inner and outer sphere complexion. In an inner sphere complex, there is a chemical interaction between adsorbent and adsorbate. In an outer-sphere complex, a weak bond, such as a hydrogen bond, occurs on the adsorbent’s outer surface. A reduction in capacity for phosphate adsorption confirms the presence of an outer sphere, and no change or a slight change confirms the inner sphere complex. Ionic strength (detail method in supplementary material appendix SI-1) was tested to determine the outer or inner sphere of complexity. Figure SI-8 shows the ionic strengths of ZnOBBNC. The figure confirms that an inner sphere complex forms during adsorption. The concentration of sodium chloride does not significantly affect phosphate adsorption, which indicates that an inner sphere mono-dentate or bi-dentate complex is formed (Zhang et al., 2017).

3.3. Kinetics studies

The four types of kinetic models (Lagergren pseudo-first-order, pseudo-second-order, Elovich and Weber-Morris) were employed to determine the adsorption process for the ZnOBBNC as shown in Fig. 8, where 3 g. L−1 of ZnOBBNC were treated with 100 mL of 100 mg. L−1 of phosphate solution. The parameters of each kinetic model for phosphate adsorption on to ZnOBBNC are listed in Table 1. As shown in Fig. 8a–c, and Table 1, the correlation coefficient () obtained from pseudo-second-order kinetic () was higher than pseudo-first-order kinetic () and Elovich kinetic (). The adsorption capacity at equilibrium was 78.12 mg. g 1, which is similar to experimental data from Tables SI–3. Hence, the pseudo-second-order kinetic model suit best to adsorption method for the removal of phosphate by ZnOBBNC compared to the pseudo-first-order kinetic and Elovich model confirms chemisorption occurred during the phosphate removal experiment, forming through the formation of chemical bonds between the adsorbent (ZnOBBNC) and the adsorbate (ions in phosphate solution) (Acelas et al., 2015), (Bañuls-ciscar et al., 2016 ).

Fig. 8.

A graph of the kinetic studies for phosphate removal using ZnOBBNC: a) Lagergren pseudo-first-order, b) Pseudo-second order, c) Elovich’s, and d) Weber-Morris Model.

Table 1.

Physiochemical Parameters of Kinetic Models of Phosphate Removal using ZnOBBNC, Phosphate Concentration: 100 mg. L−1, ZnOBBNC: 3 g. L−1, and pH ~7.

| Kinetic model | Equation | Parameters | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Pseudo-First Order | ||||

| 0.6988 | 484.4 × 10−6 | 8.71 | ||

| Pseudo-Second Order | ||||

| 1.0000 | 213.9 × 10−5 | 78.33 | ||

| Elovich Model | ||||

| 0.7962 | 473.4 × 10−3 | 1.95 | ||

| Weber-Morris Model | ||||

| 0.6897 | 671.8 × 10−3 | 55.92 | ||

To determine the intra-particle diffusion, the kinetic data of phosphate adsorption of ZnOBBNC were fitted using Weber-Morris model (). As shown in Fig. 8d, the linear line does not pass through the origin, confirming the experiment does not follow this model, and the intra-particle diffusion is not a rate-controlling step; another kinetic model should be involved to play this role (Dada et al., 2012), (Vijayakumar et al., 2012).

3.4. Adsorption isotherms

The adsorption isotherm of different phosphate concentrations (10, 50, 100, 200, 300, 400, 500 mg. L−1) at room temperature and pH 7 were analyzed to determine the maximum adsorption capacity and understand the interaction of phosphate with ZnOBBNC. Adsorption isotherms i.e. Langmuir, Freundlich, Temkin and D-R models, were plotted as shown in Fig. 9. The isotherm constants and other parameters are listed in Table 2, while the experimental and calculated adsorption capacity values of the ZnOBBNC vary with various phosphate concentrations are tabulated in Tables SI–3. The correlation coefficient () values for Langmuir, Freundlich, Temkin and D-R models were found to be 0.9616, 0.9501, 0.8774, and 0.9035, respectively. The maximum adsorption capacity of phosphate was found to be 265.50 mg. g−1. This value is greater than the reported adsorbent La(OH)3-modified magnetic pineapple biochar (101.16 mg. g−1) (Liao et al., 2018). In Table 3, we summarized the comparison of the ZnOBBNC with other reported adsorbents, confirming the ZnOBBNC has a high maximum adsorption capacity than other adsorbents. Even though the maximum capacity of ZnOBBNC is not greater than Calcium-flour biochar (314.22 mg. g−1) reported by Wang et al. (2018a, 2018b), it has to be mentioned that the synthesis of the lab-synthesized Ca-containing material would be more involved than the commercial biochar being used in our project. Also, the kinetics of phosphate adsorption by the Ca biochar shows that the process is much slower compared to ZnOBBNC. Maximum phosphate adsorption by Ca biochar takes 1.5 h to reach equilibrium as opposed to less than 15 min by ZnOBBNC.

Fig. 9.

A graph of the adsorption isotherms of ZnOBBNC: a) Langmuir, b) Freundlich, c) Temkin, and d) Dubinin-Radushkevich isotherm.

Table 2.

Physiochemical Parameters of Adsorption Isotherms of Phosphate Removal using ZnOBBNC, Phosphate Concentration: 10–500 mg. L 1, ZnOBBNC: 3 g. L−1, and pH ~7.

| Adsorption Isotherm | Equations | Parameters | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Langmuir |

265.50 |

819.0 × 10−5 |

0.9616 | |

| Freundlich |

1.65 |

964.05 × 10−3 |

0.9501 | |

| Temkin |

|

229.29 |

2.59.67 × 10−3 |

0.8774 |

| D-R |

|

223.61 |

1.00 × 10−5 |

0.9035 |

Table 3.

Comparison of ZnOBBNC with reported adsorbents.

| Adsorbents | Maximum Adsorption Capacity | References |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Ferric oxides/biochar hybrid adsorbent | 0.963 mg. g−1 for 2 g in 250 mL. | Jing et al. (2015) |

| biochar nanocomposites | 98.2 mg. g−1 and 159.4 mg.g−1 for 0.05 g in 50 mL | Wang et al. (2016a, 2016b) |

| Ca impregnated biochar | 105.41 mg. g−1 for 0.1 g in 50 mL. | Liu et al. (2016) |

| Waste-marine microalgae derived biochar | 32.57 mg. g−1 for 0.2 g in 100 mL. | Jung et al. (2016) |

| modified biochar | 100 mg. g−1 for 0.1 g in 50 mL. | Gong et al. (2017) |

| Iron-modified biochars | 111 mg. g−1 for 0.2 g in 100 mL. | Yang et al. (2018) |

| Calcium-flour biochar | 314.22 mg. g−1 for 0.1 g in 1 L. | Wang et al.(2018a, 2018b) |

| Magnesium-pretreated biochar | 66.7 mg. g−1 for 2 g in 1 L. | Haddad et al. (2018) |

| modified magnetic pineapple biochar | 101.16 mg. g−1 for 0.025 g in 25 mL. | Liao et al. (2018) |

| Al-modified biochar | 57.49 mg. g−1 for 0.1 g in 50 mL. | Yin et al. (2018a) |

| Mg-Al-modified biochar | 74.47 mg. g−1 for 0.1 g in 50 mL. | Yin et al. (2018b) |

| Biochar-MgAl LDH Nanocomposites | 177.97 mg. g−1 for 5 mg in 40 mL. | Alagha et al. (2020) |

| Phosphogypsum biochar | 102.4 mg. g−1 for 0.025–0.2 mg in 40 mL. | Wang et al. (2020) |

| ZnOBBNC | 265.50 mg. g−1 for 3 g in 1 L. | This study |

From the linear plot of the Langmuir isotherm (Fig. 9a), the RL value was found to be 0.44, which suggests that the experiment follows a Langmuir isotherm and describes the monolayer adsorption on the ZnOBBNC (Kim et al., 2006), (Inyinbor et al., 2016).

3.5. Adsorption mechanism

From Figure SI-9, it shows that the kinetics of phosphate adsorption on ZnOBBNC is faster than the control Betaine-modified biochar and zinc oxide-modified biochar. These results further confirmed that the washed ZnOBBNC showed 80% removal of phosphate, whereas unwashed removed 100% in 4 h. This may be due to some zinc oxide and betaine being washed away. From the results of pH influence, the main phosphate species in water were the H2PO4− ion at pH ranges 5–7, leading chemisorption, which releases OH− ions to the solution as shown below (Nakarmi et al., 2018).

| (1) |

As pH increases, the ZnOBBNC surface holds a more negative charge and OH ion increases on the solution, which creates a competition between phosphate ion and OH− ion on the adsorbent surface (Elkady et al., 2016). Moreover, the zinc oxide and biochar is chelated by the quaternizing reagent (betaine HCl), creating nanocomposites (ZnOBBNC). The transition metal, specifically zinc, in zinc oxide has empty d-orbitals which can receive electrons from the negatively charged adsorbent (ions) that increases phosphate adsorption from the phosphate solution (Xu et al., 2020), (Nakarmi et al., 2020). In addition, there might be an ion exchange between solution phosphate ion and the adsorbent chloride ion during the process of phosphate removal as shown below.

| (2) |

The possible adsorption mechanism during phosphate removal is shown below in Scheme 2.

Scheme 2.

Diagram of possible mechanisms of phosphate removal using ZnOBBNC.

Previous studies showed that the phosphate adsorption occurred through bond (Elkady et al., 2016). Schemes SI–1 shows the interaction of zinc oxide of ZnOBBNC with phosphate ions in the solution. Adsorption isotherms and kinetic models also suggest that the ZnOBBNC exhibit a mono-layered chemisorption mechanism with heterogeneous surface and formation of a mono-dentate and bi-dentate inner-sphere complex (according to the ionic strength) as shown in Schemes SI–2.

3.6. Feasibility of phosphate removal from real field wastewater

To demonstrate the feasibility of phosphate removal by ZnOBBNC from a real field wastewater, batch studies were performed and analyzed in the ion-exchange chromatography (IEC). Two samples of real field wastewater were used in this experiment. One of the real field wastewater contaminated by phosphate ions was obtained from the Adams Field Little Rock Water Reclamation Authority (Little Rock, Arkansas), while another sample was collected from the creek of the University of Arkansas at Little Rock. A 100 mL of each sample was filtered with filter paper and treated with 3 g. L−1 of ZnOBBNC in a 125 mL Erlenmeyer flask for 24 h using a mechanical shaker at room temperature. The treated water samples along with untreated wastewater, were run through the IEC instrument in order to determine the presence of different anions (fluoride, chloride, bromide, nitrite, nitrate, phosphate, and sulfate) in real field wastewater and the removal of anions after treatment with ZnOBBNC. Tables SI–4 summarizes the results of the real field wastewater tests, which confirm the usefulness of ZnOBBNC for real field wastewater treatment without regard of other anions present. Initial concentrations of phosphate ion (1.21 0.03 mg. L−1 of Adams Field wastewater and 1.45 0.02 mg. L−1 of UA Little Rock Creek) were completely removed by ZnOBBNC. Some anions like bromide, nitrite and nitrate were not contained in the wastewater samples.

Furthermore, the ZnOBBNC removed other anions such as sulfate (~30% removal) to some extent from the wastewater. However, ZnOBBNC does not remove fluoride and chloride, but these ions have no effect on the phosphate removal from wastewater. The fluoride ion concentration in the treated water is twice as high as the untreated wastewater that could be due to experimental error. While chloride ion concentration in the treated water is five times greater than that of the untreated wastewater. It may be attributed to the exchange of phosphate ions from solution with ZnOBBNC chloride ions (Chen et al., 2015). Based on these results of the real field wastewater tests (Tables SI–4), it confirms that the ZnOBBNC provides a viable adsorbent for phosphate removal.

4. Conclusion

Biochar has been utilized to synthesize a new form of nanocomposites adsorbent (ZnOBBNC), which is benign and less expensive than commercial nanocomposites. It was prepared by a straightforward technique, which is a time-saving and effortless process. The isotherm and kinetic studies confirmed the chemisorption of phosphate to the heterogeneous surface of the ZnOBBNC. The ZnOBBNC exhibited a high capacity of phosphate (265.5 mg. g−1) and fast kinetic (100% removal at 15 min) in 10 mg. L−1 of phosphate solution. The real field wastewater test also showed positive results. The performance of ZnOBBNC was not influenced by pH and coexisting ions in the aqueous solutions, proving extremely useful in phosphate removal and exhibiting many benefits compared to commercially available nanocomposites. There is no by-product formed during ZnOBBNC use and has no deleterious impacts on the quality of water; additionally, biochar can be used as a soil quality enhancer. The spent ZnOBBNC may thus be used for enhanced soil quality improvement after phosphate treatment.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

This project was financially supported by Synanomet, LLC. Little Rock and the University of Arkansas at Little Rock. This work was also supported by the Center for Integrative Nanotechnology Sciences (CINS) and the Department of Earth Sciences at the University of Arkansas at Little Rock for the instrumental analysis. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy or position of the USEPA or the United States government.

Footnotes

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Amita Nakarmi: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Visualization, Validation, Writing - original draft. Shawn E. Bourdo: Formal analysis, Writing - review & editing. Laura Ruhl: Formal analysis, Writing - review & editing. Sushil Kanel: Writing - review & editing. Mallikarjuna Nadagouda: Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing - review & editing. Praveen Kumar Alla: Formal analysis, Methodology. Ioana Pavel: Writing - review & editing. Tito Viswanathan: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Writing - review & editing.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2020.111048.

References

- Acelas NY, Martin BD, López D, Jefferson B, 2015. Selective removal of phosphate from wastewater using hydrated metal oxides dispersed within anionic exchange media. Chemosphere 119, 1353–1360. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2014.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad M, Rajapaksha AU, Lim JE, Zhang M, Bolan N, Mohan D, Vithanage M, Lee SS, Ok YS, 2014. Biochar as a sorbent for contaminant management in soil and water: a review. Chemosphere 99, 19–33. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2013.10.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ai-yuan M, Jin-hui P, Li-bo Z, Li S, Kun Y, Xue-mei Z, 2016. LEACHING Zn FROM THE LOW-GRADE ZINC OXIDE ORE IN NH 3 -H 3 C 6 H 5 O 7 -H 2 O media. Braz. J. Chem. Eng 33, 907–917. [Google Scholar]

- Akhavan O, 2010. Graphene nanomesh by ZnO nanorod photocatalysts. ACS Nano 4, 4174–4180. 10.1021/nn1007429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akhtar MJ, Ahamed M, Kumar S, Majeed Khan MA, Ahmad J, Alrokayan SA, 2012. Zinc oxide nanoparticles selectively induce apoptosis in human cancer cells through reactive oxygen species. Int. J. Nanomed 7, 845–857. 10.2147/IJN.S29129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alagha O, Manzar MS, Zubair M, Anil I, Mu’azu ND, Qureshi A, 2020. Comparative adsorptive removal of phosphate and nitrate from wastewater using biochar-MgAl LDH nanocomposites: coexisting anions effect and mechanistic studies. Nanomaterials 10. 10.3390/nano10020336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armelao L, Barreca D, Bottaro G, Gasparotto A, Leonarduzzi D, Maragno C, Tondello E, 2006. ZnO: Er(III) nanosystems analyzed by XPS. Surf. Sci. Spectra 13, 9–16. 10.1116/11.20060301. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bañuls-ciscar J, Pratelli D, Abel M, Watts JF, 2016. Surface characterisation of pine wood by XPS. Surf. Interface Anal 48, 589–592. 10.1002/sia.5960. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Behazin E, Ogunsona E, Rodriguez-Uribe A, Mohanty AK, Misra M, Anyia AO, 2016. Mechanical, chemical, and physical properties of wood and perennial grass biochars for possible composite application. BioResources 11, 1334–1348. 10.15376/biores.11.1.1334-1348. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bektaş N, Akbulut H, Inan H, Dimoglo A, 2004. Removal of phosphate from aqueous solutions by electro-coagulation. J. Hazard Mater 106, 101–105. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2003.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biswas BK, Inoue K, Ghimire KN, Ohta S, Harada H, Ohto K, Kawakita H, 2007. The adsorption of phosphate from an aquatic environment using metal-loaded orange waste. J. Colloid Interface Sci 312, 214–223. 10.1016/j.jcis.2007.03.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaney LM, Cinar S, SenGupta AK, 2007. Hybrid anion exchanger for trace phosphate removal from water and wastewater. Water Res. 41, 1603–1613. 10.1016/j.watres.2007.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Huang X, Zhang Y, Yuan D, 2015. A new polymeric ionic liquid-based magnetic adsorbent for the extraction of inorganic anions in water samples. J. Chromatogr. A 1403, 37–44. 10.1016/j.chroma.2015.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dada AO, Olalekan AP, Olatunya AM, Dada O, 2012. Langmuir, Freundlich, Temkin and dubinin–radushkevich isotherms studies of equilibrium sorption of Zn 2 + unto phosphoric acid modified rice husk. IOSR J. Appl. Chem 3, 38–45. 10.9790/5736-0313845. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Elkady MF, Shokry Hassan H, Salama E, 2016. Sorption profile of phosphorus ions onto ZnO nanorods synthesized via sonic technique. J. Eng 2016 10.1155/2016/2308560. United Kingdom. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- EPA, 2008. Clean Watersheds Needs Survey. [Google Scholar]

- EPA365. 1, 1993. Method 365.1,Determination of Phosphorus by Semi-automated Colorimetry. EPA. [Google Scholar]

- EPA365. 2, 1983. Phosphorous,All Forms (Colorimetric,ascorbic Acid, Single Reagent). NPDES. [Google Scholar]

- EPA365. 3, 1978. Phosphorous, All Forms (Colorimetric, Ascorbic Acid, Two Reagent). NPDES. 10.1159/000330408. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gong YP, Ni ZY, Xiong ZZ, Cheng LH, Xu XH, 2017. Phosphate and ammonium adsorption of the modified biochar based on Phragmites australis after phytoremediation. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res 24, 8326–8335. 10.1007/s11356-017-8499-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guzman L, Gunawan G, Viswanathan T, 2012. Removal of phosphorus from contaminated wastewater using an iron-containing quaternized wood nanocomposite. Int. J. Green Nanotechnol 4, 207–214. 10.1080/19430892.2012.706005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Haddad K, Jellali S, Jeguirim M, Ben Hassen Trabelsi A, Limousy L, 2018. Investigations on phosphorus recovery from aqueous solutions by biochars derived from magnesium-pretreated cypress sawdust. J. Environ. Manag 216, 305–314. 10.1016/j.jenvman.2017.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inyinbor AA, Adekola FA, Olatunji GA, 2016. Kinetics, isotherms and thermodynamic modeling of liquid phase adsorption of Rhodamine B dye onto Raphia hookerie fruit epicarp. Water Resour. Ind 15, 14–27. 10.1016/j.wri.2016.06.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jablonowski ND, Borchard N, Zajkoska P, Fernandez-Bayo JD, Martinazzo R, Berns AE, Burauel P, 2013. Biochar-mediated [14C]atrazine mineralization in atrazine-adapted soils from Belgium and Brazil. J. Agric. Food Chem 61, 512–516. 10.1021/jf303957a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jalal R, Goharshadi EK, Abareshi M, Moosavi M, Yousefi A, Nancarrow P, 2010. ZnO nanofluids: green synthesis, characterization, and antibacterial activity. Mater. Chem. Phys 121, 198–201. 10.1016/j.matchemphys.2010.01.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jia Y, Wu C, Lee BW, Liu C, Kang S, Lee T, Park YC, Yoo R, Lee W, 2017. Magnetically separable sulfur-doped SnFe2O4/graphene nanohybrids for effective photocatalytic purification of wastewater under visible light. J. Hazard Mater 338, 447–457. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2017.05.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jing R, Nan L, Lei L, Jing Kun A, Lin Z, Nan Qi R, 2015. Granulation and ferric oxides loading enable biochar derived from cotton stalk to remove phosphate from water. Bioresour. Technol 178, 119–125. 10.1016/j.biortech.2014.09.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung K, Jeong T, Choi H, Kang H-J, Ahn K, 2015a. Phosphate adsorption from aqueous solution by Laminaria japonica-derived biochar-calcium alginate beads in a fixed-bed column: experiments and prediction of breakthrough curves. Environ. Prog. Sustain. Energy 35, 809–814. 10.1002/ep. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jung KW, Jeong TU, Hwang MJ, Kim K, Ahn KH, 2015b. Phosphate adsorption ability of biochar/Mg-Al assembled nanocomposites prepared by aluminum-electrode based electro-assisted modification method with MgCl2 as electrolyte. Bioresour. Technol 198, 603–610. 10.1016/j.biortech.2015.09.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung KW, Kim K, Jeong TU, Ahn KH, 2016. Influence of pyrolysis temperature on characteristics and phosphate adsorption capability of biochar derived from waste-marine macroalgae (Undaria pinnatifida roots). Bioresour. Technol 200, 1024–1028. 10.1016/j.biortech.2015.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamarulzaman N, Kasim MF, Chayed NF, 2016. Elucidation of the highest valence band and lowest conduction band shifts using XPS for ZnO and Zn0.99Cu0.01O band gap changes. Results Phys. 6, 217–230. 10.1016/j.rinp.2016.04.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kanel SR, Al-Abed SR, 2011. Influence of pH on the transport of nanoscale zinc oxide in saturated porous media. J. Nanoparticle Res 13, 4035–4047. 10.1007/s11051-011-0345-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kanel SR, Greneche JM, Choi H, 2006. Arsenic(V) removal from groundwater using nano scale zero-valent iron as a colloidal reactive barrier material. Environ. Sci. Technol 40, 2045–2050. 10.1021/es0520924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanel SR, Manning B, Charlet L, Choi H, 2005. Removal of arsenic(III) from groundwater by nanoscale zero-valent iron. Environ. Sci. Technol 39, 1291–1298. 10.1021/es048991u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karunanayake AG, Navarathna CM, Gunatilake SR, Crowley M, Anderson R, Mohan D, Perez F, Pittman CU, Mlsna T, 2019. Fe3O4 nanoparticles dispersed on Douglas fir biochar for phosphate sorption. ACS Appl. Nano Mater 2, 3467–3479. 10.1021/acsanm.9b00430. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Mann JD, Kwon S, 2006. Enhanced adsorption and regeneration with lignocellulose-based phosphorus removal media using molecular coating nanotechnology. J. Environ. Sci. Heal. Part A 41, 87–100. 10.1080/10934520500299570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kołodynska D, Krukowska J, Thomas P, 2017. Comparison of sorption and desorption studies of heavy metal ions from biochar and commercial active carbon. Chem. Eng. J 307, 353–363. 10.1016/j.cej.2016.08.088. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li R, Wang JJ, Zhou B, Awasthi MK, Ali A, Zhang Z, Gaston LA, Lahori AH, Mahar A, 2016. Enhancing phosphate adsorption by Mg/Al layered double hydroxide functionalized biochar with different Mg/Al ratios. Sci. Total Environ 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.03.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao T, Li T, Su X, Yu X, Song H, Zhu Y, Zhang Y, 2018. La(OH)3-modified magnetic pineapple biochar as novel adsorbents for efficient phosphate removal. Bioresour. Technol 263, 207–213. 10.1016/j.biortech.2018.04.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L, Tan Z, Gong H, Huang Q, 2019a. Migration and transformation mechanisms of nutrient elements (N, P, K) within biochar in straw-biochar-soil-plant systems: a review. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng 10.1021/acssuschemeng.8b04253. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu N, Liu Y, Zeng G, Gong J, Tan X, Jun Wen, Liu S, Jiang L, Li M, Yin Z, 2020. Adsorption of 17β-estradiol from aqueous solution by raw and direct/pre/ post-KOH treated lotus seedpod biochar. J. Environ. Sci 87, 10–23. 10.1016/j.jes.2019.05.026. China. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu SB, Tan XF, Liu YG, Gu YL, Zeng GM, Hu XJ, Wang H, Zhou L, Jiang LH, Zhao B. Bin, 2016. Production of biochars from Ca impregnated ramie biomass (Boehmeria nivea (L.) Gaud.) and their phosphate removal potential. RSC Adv. 6, 5871–5880. 10.1039/c5ra22142k. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Xiangrong, Liao J, Song H, Yang Y, Guan C, Zhang Z, 2019b. A biochar-based route for environmentally friendly controlled release of nitrogen: urea-loaded biochar and bentonite composite. Sci. Rep 9 (9548) 10.1038/s41598-019-46065-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Xiaoning, Shen F, Qi X, 2019c. Adsorption recovery of phosphate from aqueous solution by CaO-biochar composites prepared from eggshell and rice straw. Sci. Total Environ 666, 694–702. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.02.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo L, Wang G, Shi G, Zhang M, Zhang J, He J, Xiao Y, Tian D, Zhang Y, Deng S, Zhou W, Lan T, Deng O, 2019. The characterization of biochars derived from rice straw and swine manure, and their potential and risk in N and P removal from water. J. Environ. Manag 245, 1–7. 10.1016/j.jenvman.2019.05.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahmood T, Saddique MT, Naeem A, Westerhoff P, Mustafa S, Alum A, 2011. Comparison of different methods for the point of zero charge determination of NiO. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res 50 (17), 10017–10023. 10.1021/ie200271d. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Manning BA, Kiser JR, Kwon H, Kanel SR, 2007. Spectroscopic investigation of Cr (III)-and Cr(VI)-treated nanoscale zerovalent iron. Environ. Sci. Technol 41, 586–592. 10.1021/es061721m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mia S, Dijkstra FA, Singh B, 2017. Aging induced changes in biochar’s functionality and adsorption behavior for phosphate and ammonium. Environ. Sci. Technol 51, 8359–8367. 10.1021/acs.est.7b00647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michalekov a-Richveisov a B, Fri stak V, Pipí ska M, Duri ska L, Moreno-Jimenez E, Soja G, 2017. Iron-impregnated biochars as effective phosphate sorption materials. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res 24, 463–475. 10.1007/s11356-016-7820-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakarmi A, Chandrasekhar K, Bourdo SE, Watanabe F, Guisbiers G, Viswanathan T, 2020. Phosphate removal from wastewater using novel renewable resource-based, cerium/manganese oxide-based nanocomposites. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int 1–16. 10.1007/s11356-020-09400-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakarmi A, Kim J, Toland A, Viswanathan T, 2018. Novel reusable renewable resource-based iron oxides nanocomposites for removal and recovery of phosphate from contaminated waters. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol 16, 4293–4302. 10.1007/s13762-018-2058-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Park JH, Ok YS, Kim SH, Cho JS, Heo JS, Delaune RD, Seo DC, 2016. Competitive adsorption of heavy metals onto sesame straw biochar in aqueous solutions. Chemosphere 142, 77–83. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2015.05.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polomski RF, Taylor MD, Bielenberg DG, Bridges WC, Klaine SJ, Whitwell T, 2009. Nitrogen and phosphorus remediation by three floating aquatic macrophytes in greenhouse-based laboratory-scale subsurface constructed wetlands. Water Air Soil Pollut. 197, 223–232. 10.1007/s11270-008-9805-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ramasahayam SK, Gunawan G, Finlay C, Viswanathan T, 2012. Renewable resource-based magnetic nanocomposites for removal and recovery of phosphorous from contaminated waters. Water, Air, Soil Pollut. 223, 4853–4863. 10.1007/s11270-012-1241-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- RanguMagar AB, Chhetri BP, Parnell CM, Parameswaran-Thankam A, Watanabe F, Mustafa T, Biris AS, Ghosh A, 2018. Removal of nitrophenols from water using cellulose derived nitrogen doped graphitic carbon material containing titanium dioxide, 0 Part. Sci. Technol 1–9. 10.1080/02726351.2017.1391906. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ritt CL, Chisholm BJ, Bezbaruah AN, 2019. Assessment of molecularly imprinted polymers as phosphate sorbents. Chemosphere 226, 395–404. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2019.03.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon Q, Barreca D, Gasparotto A, 2010. CuO/ZnO nanocomposites investigated by X-ray Photoelectron and X-ray excited auger electron spectroscopies. Surf. Sci. Spectra 17, 93–101. 10.1116/11.20111002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vijayakumar G, Tamilarasan R, Dharmendirakumar M, 2012. Adsorption, kinetic, equilibrium and thermodynamic studies on the removal of basic dye Rhodamine-B from aqueous solution by the use of natural adsorbent perlite. J. Mater. Environ. Sci 3, 157–170. [Google Scholar]

- Viswanathan T, 2020. Water Purification Compositions and the Method of Producing the Same. US20200002193A1. [Google Scholar]

- Wang B, Lian G, Lee X, Gao B, Li L, Liu T, Zhang X, Zheng Y, 2020. Phosphogypsum as a novel modifier for distillers grains biochar removal of phosphate from water. Chemosphere 238 (124684). 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2019.124684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q, Gao S, Wang D, Spokas K, Cao A, Yan D, 2016a. Mechanisms for 1,3-dichloropropene dissipation in biochar-amended soils. J. Agric. Food Chem 64, 2531–2540. 10.1021/acs.jafc.5b04941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S, Kong L, Long J, Su M, Diao Z, Chang X, Chen D, Song G, Shih K, 2018a. Adsorption of phosphorus by calcium-flour biochar: isotherm, kinetic and transformation studies. Chemosphere 195, 666–672. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2017.12.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Wang Z, Peak D, Tang Y, Feng X, Zhu M, 2018b. Quantification of coexisting inner- and outer-sphere complexation of sulfate on hematite surfaces. ACS Earth Sp. Chem 2, 387–398. 10.1021/acsearthspacechem.7b00154. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang YY, Hao Hao L, Yu Xue L, Sheng Mao Y, 2016b. Removal of phosphate from aqueous solution by SiO2-biochar nanocomposites prepared by pyrolysis of vermiculite treated algal biomass. RSC Adv. 6, 83534–83546. 10.1039/c6ra15532d. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Guo H, Shen F, Yang G, Zhang Y, Zeng Y, Wang L, Xiao H, Deng S, 2015. Biochar produced from oak sawdust by Lanthanum (La)-involved pyrolysis for adsorption of ammonium (NH4þ), nitrate (NO3-), and phosphate (PO43-). Chemosphere 119, 646–653. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2014.07.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO, 2018. WHO Global Water, Sanitation and Hygiene. [Google Scholar]

- Woolf D, Amonette JE, Street-Perrott FA, Lehmann J, Joseph S, 2010. Sustainable biochar to mitigate global climate change. Nat. Commun 1, 1–9. 10.1038/ncomms1053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu H, Wei C, Li C, Fan G, Deng Z, Li M, Li X, 2010. Sulfuric acid leaching of zinc silicate ore under pressure. Hydrometallurgy 105, 186–190. 10.1016/j.hydromet.2010.07.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X, Wang B, Tang H, Jin Z, Mao Y, Huang T, 2020. Removal of phosphate from wastewater by modified bentonite entrapped in Ca-alginate beads. J. Environ. Manag 260 (110130) 10.1016/j.jenvman.2020.110130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan L, Kong L, Qu Z, Li L, Shen G, 2015. Magnetic biochar decorated with ZnS nanocrytals for Pb (II) removal. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng 3, 125–132. 10.1021/sc500619r. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Q, Wang X, Luo W, Sun J, Xu Q, Chen F, Zhao J, Wang S, Yao F, Wang D, Li X, Zeng G, 2018. Effectiveness and mechanisms of phosphate adsorption on iron-modified biochars derived from waste activated sludge. Bioresour. Technol 247, 537–544. 10.1016/j.biortech.2017.09.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z, Xu M, Liu Y, He F, Gao F, Su Y, Wei H, Zhang Y, 2014. Nitrogen-doped, carbon-rich, highly photoluminescent carbon dots from ammonium citrate. Nanoscale 6 (3), 1890–1895. 10.1039/c3nr05380f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X, Yu IKM, Cho DW, Chen SS, Tsang DCW, Shang J, Yip ACK, Wang L, Ok YS, 2019. Tin-Functionalized wood biochar as a sustainable solid catalyst for glucose isomerization in biorefinery. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng 7, 4851–4860. 10.1021/acssuschemeng.8b05311. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yao Y, Gao B, Inyang M, Zimmerman AR, Cao X, Pullammanappallil P, Yang L, 2011. Removal of phosphate from aqueous solution by biochar derived from anaerobically digested sugar beet tailings. J. Hazard Mater 190, 501–507. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2011.03.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yavorskyy A, Hernandez-Santana A, McCarthy G, McMahon G, 2008. Detection of calcium phosphate crystals in the joint fluid of patients with osteoarthritis - analytical approaches and challenges. Analyst 133, 302–318. 10.1039/b716791a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin Q, Ren H, Wang R, Zhao Z, 2018a. Evaluation of nitrate and phosphate adsorption on Al-modified biochar: influence of Al content. Sci. Total Environ 631–632, 895–903. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.03.091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin Q, Wang R, Zhao Z, 2018b. Application of Mg–Al-modified biochar for simultaneous removal of ammonium, nitrate, and phosphate from eutrophic water. J. Clean. Prod 176, 230–240. 10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.12.117. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zak AK, Razali R, Majid WHA, Darroudi M, 2011. Synthesis and characterization of a narrow size distribution of zinc oxide nanoparticles. Int. J. Nanomed 6, 1399–1403. 10.2147/ijn.s19693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Wang X, Chen Z, 2017. A novel nanocomposite as an efficient adsorbent for the rapid adsorption of Ni(II) from aqueous solution. Materials 10, 1–22. 10.3390/ma10101124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, Yan L, Yu H, Yan T, Li X, 2019. Adsorption of phosphate from aqueous solution by vegetable biochar/layered double oxides: fast removal and mechanistic studies. Bioresour. Technol 284, 65–71. 10.1016/j.biortech.2019.03.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.