Abstract

The family physician program (FPP) is one of the most significant health care reforms in Iran; however, many studies showed that this program has not been able to achieve its intended objectives because of a variety of challenges. This program, despite the existing challenges, is going to be expanded across the country. To improve the likelihood of its success, identification of the structural and infrastructural challenges is necessary. This systematic review was conducted to assess the structural and infrastructural challenges of FPP in Iran. This systematic review of the literature was conducted in order to investigate the infrastructure and structure needs of the current program in Iran. All published articles related to the FPP in Iran were the subject of this study. The eligibility criteria included original articles, reviews, or case studies published in English or Persian during 2011–2021 related to the challenges in the referral system of FPP in Iran. Data were extracted based on Sample, Phenomenon of Interest, Design, Evaluation, Research type technique and were reported based on the structure of Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses. International credible scholarly databases were searched. The search strategy was defined based on keywords and the search syntax. This study identified different challenges of the referral system in the areas associated with legal structure, administration, and social structure. The identified challenges in this program should be addressed in order to ensure that this program will lead to improved quality of care and equity in Iran health care system.

Keywords: Family, health plan implementation, health systems plan, managed care programs, physicians

Introduction

The World Health Organization (WHO) has identified three goals for health care systems: enhancing population health, a responsive and fair financing system, and financial risk protection.[1] The family practice has been recommended by WHO[2] as a means to achieve quality improvement, cost-effectiveness, and equity in the health care system. Studies confirmed that family practice has improved health outcomes, even in settings with poor health equity,[3,4] and many countries have incorporated it into their health care system.

In 2004, the Family Physician Program (FPP), consisting of outpatient-based general physicians (without additional graduate training) to practice preventative medicine and serve as referral gatekeepers, was included in the fifth Development Plan of Iran and formally initiated in the rural areas in the year 2005. Six years later, the program was expanded to urban settings with populations of 5000 to 20,000, along with an additional pilot implementation in cities with populations up to 50,000 in three provinces of Iran,[5] as a collaborative effort between the Ministry of Health and Medical Education (MoHME) and Ministry of Cooperatives Labor and Social Welfare (MoCLSW).

The FPP is one of the most significant health care reforms in Iran in recent years, aiming to increase public access to health services, decrease unnecessary referrals, achieve health equity and justice, improve services quality, achieve universal health coverage, maintain and improve the health of the community, and provide health services to all individuals and families regardless of age, gender, and socio-economic status.[6]

However, many studies showed that this program has not been able to achieve its intended objectives because of a variety of challenges.[7,8,9,10,11,12] Among the requirements for the FPP to achieve these are adequate structures and infrastructures. However, studies indicate that the program was initiated without addressing these critical needs.[7,13,14,15]

This program, despite the existing challenges, is going to be expanded across the country. To improve the likelihood of its success, identification of the structural and infrastructural challenges is necessary. This systematic review of the literature was conducted in order to investigate the infrastructure and structure needs of the current FPP in Iran.

Materials and Methods

This study aimed to systematically review published articles that investigated the infrastructure and structure of the FPP and were reported based on the structure of Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA).

Eligibility criteria

All published articles related to the implementation of the FPP in Iran were the subject of this study. The eligibility criteria were original, qualitative studies published in English or Persian between 2011 and 2021.

Exclusion criteria were gray literature, quantitative studies, and studies published in languages other than English or Persian.

Information sources

In January 2022, international credible scholarly databases (Google Scholar and PubMed) and Persian databases (Iran Medex, Magiran, Iran Doc, and SID) were searched. In addition, the references of the selected articles were hand-searched to find relevant studies.

Search strategy

The search strategy was defined based on keywords and the search syntax, which was first defined for the PubMed database and then revised according to each database's specific framework of search method.

The following keywords were used in both English and Persian: “family physician”, “family physician care program”, “general practice”, “general medicine”, “general practitioner”, “general physician”, “structure”, “infrastructure”, “law”, “regulation”, “administrative”, “policy making”, “insurance”, “outcomes”, “assessment”, “service quality”, “implementation”, “evaluation”, “impact”, “performance”, challenges”, “achievements”, “role”, and “Iran”. Searches employed terms individually and in combinations using Boolean operators “AND” and “OR”.

Selection process

Based on the title and abstract of the articles, two reviewers independently evaluated articles returned by the search regarding the inclusion criteria. Studies were classified into three categories: “excluded”, “included”, or “probable”. The reviewers then evaluated the full text of the articles they would categorize as “probable” and re-assigned them to “included” or “excluded”. The lists generated by the reviewers were compared, and articles for which both reviewers were in agreement on categorization were excluded or included, respectively. Where there was disagreement between the reviewers’ assigned category of an article, the disputed articles were included or excluded based on evaluation by a third reviewer.

Data collection process

All selected articles were carefully studied, and the following data were extracted based on Sample, Phenomenon of Interest, Design, Evaluation, Research type (SPIDER) technique. These data include the title, authors, year of publication, name of the journal, study design, participants, instruments, settings, variables, strengths, and weaknesses.

Data items

The challenges related to the structures and infrastructures of the FPP in Iran were the data item in this study.

Study risk of bias assessment

Two independent reviewers conducted the eligibility, quality assessment, and data extraction stages of the systematic review and sought the opinion of a third reviewer in case of a difference of opinion.

A methodologist checked the validity of studies based on the international guidelines for reporting of research, such as the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Studies (COREQ) and Case Reports (CARE) guideline, and those published articles with low validity were excluded from the study.

Results

Study selection

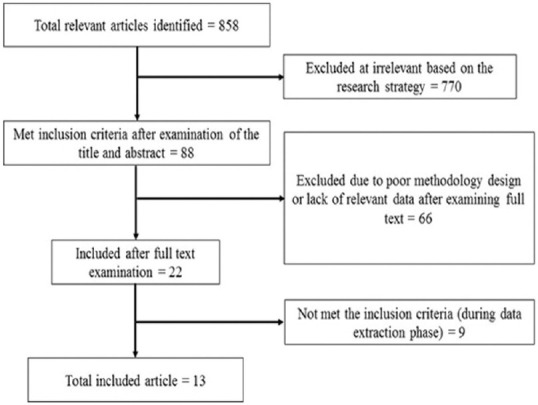

Out of 858 articles retrieved by the search strategy, 88 were retrieved after review of titles and abstracts. After reviewing the full text, 66 studies were excluded because of either poor methodology design or lack of relevant data. Another nine studies were excluded during data extraction because they did not meet the entire inclusion criteria. This resulted in a final total of 13 eligible empirical studies included in the present review [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

The flowchart of the publication selection

Study characteristics

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the final 13 studies. All 13 studies used qualitative methods. Data were collected through interviews and focus group discussions, and one study used document analysis. A total of 328 interviews and 29 focus group discussions were conducted in these studies.

Table 1.

The characteristics of the included studies

| Authors | Publication year | Study design | Data collection | Participants | Sample size | Location | Urban/rural family physician |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sarvestani et al.[8] | 2017 | Exploratory- descriptive qualitative study | Interview | Family physicians and specialists | 17 | Fasa city | Urban |

| Doshmangir et al.[5] | 2017 | Qualitative study | Interview | Informants from Ministry of Health, health insurance organizations, management and planning organization of Iran, Iran Medical Council, medical universities, health research centers | 19 | Cities of Iran | Urban |

| Fardid et al.[9] | 2019 | Qualitative study | Interview and focus group | National and regional policy-makers, managers, physicians, patients, health professionals, FP officers who influenced the decision-making process, and design and implementation of the FP program | 24 Interview and three focus groups | Fars province | Urban |

| Mehrolhassani et al.[14] | 2021 | Qualitative study | Interview | National and provincial level policy-makers and managers | 44 | Kerman province | Urban |

| Dehnavieh et al.[7] | 2015 | Qualitative study | Interview | Informants from the medical university, health service insurance, medical system, social physicians, researchers in the field of family physicians | 21 | Cities in Kerman provinces | Urban |

| Shiyani et al.[16] | 2016 | Qualitative study | Interview and Document analysis | Policy makers, managers of medical universities, key informants | 26 | Iran | Urban |

| Bolbanabad et al.[13] | 2019 | Qualitative study | Interview and focus group | Managers, experts, family physicians, specialists, midwives, health insurance experts and service recipients, community health care workers (behvarz*) | 30 interview and five focus groups (36) | Kordestan province | Rural |

| Farzad Far et al.[17] | 2018 | Qualitative study | Interview and focus group | Family physicians, midwives, managers, health insurance managers, service recipients | 37 interview and 21 focus groups | Kordestan, Alborz and West Azarbaijan provinces | Urban |

| Kaskaldareh et al.[18] | 2021 | Qualitative study | Interview | Health network managers and assistants, family physicians, and information security experts of the University | 15 | Gilan province | Urban/Rural |

| Damari et al.[19] | 2017 | Qualitative study | Interview and focus group | Informants and experts, Professors from Tehran and Iran Universities of Medical Sciences, Members of the Islamic Consultative Assembly, Managers of Medical System Organizations, Nursing System, Health Insurance, Social Security Organization and Plan and Budget Organization | 40 | Mazandaran and Fars provinces | Urban |

| Alaie et al.[20] | 2020 | Qualitative study | Interview | Policy makers informants, | 26 | Iran | Urban/Rural |

| Hooshmand et al.[21] | 2020 | Qualitative and quantitative study | Interview | Managers and family physicians | 20 | Khorasan Razavi province | Rural |

| Abedi et al.[15] | 2017 | Qualitative study | Interview | Family physician, senior managers, experts, board members | nine | Iran | Urban |

*Behvarz is a kind of health care worker who works in the rural services in the health house

The participants included family physicians and other specialists, policymakers, managers, non-physician health professionals such as mid-wives and Behvarz (community health workers), and patients. Informed officials of the Ministry of Health, Health Insurance Organizations, Management, and Planning Organization of Iran, Iran Medical Council, medical universities, health research centers and members of the Islamic Consultative Assembly, Plan and Budget Organization, and researchers in the field of family medicine were among the participants.

Nine of the 13 studies investigated the urban FPP, two studies investigated the rural FPP, and two studies investigated both [Table 2].

Table 2.

The main findings of 13 studies regarding the challenges associated with the infrastructure and structure of FPP

| Writer (year) | The infrastructural challenges | The structural challenges |

|---|---|---|

| Sarvestani et al. (2017)[8] | No attempts for acculturation Failure in expertizing the program | Treatment-based instead of prevention-based (deviation from the main goal) |

| Doshmangir et al. (2017)[5] | Current health insurance system was not ready to embrace a great health system reform such as FP Delayed reimbursement by health insurance to the family physicians Lack of a pooled fund and fragmented health insurance system Lack of a public insurance scheme Insufficient number of family physicians Lack of adequate financial resources, underestimation of the required funds for the plan, allocating the available financial support by entities other than the responsible institutions, lack of clear and stable financial resources for the program Lack of the necessary hardware platform and sufficient internet speed for the utilization of electronic health records (EHR) inadequate introduction of the FPP, not giving accurate and comprehensive information about the benefits and features of FPP to public. | Lack of a united health leadership and governance in the country Lack of cooperation between stakeholders, intra-/inter-sectional cooperation No rational medical tariffs based on relative value of health services |

| Fardid et al. (2019)[9] | Lack of health electronic records (fragmented databases) Lack of acculturation (patients insisting to the FPs for unnecessary referral to a specialist, resistance by the public and the specialist toward implementation of the program) Multiple insurance funds. | Violation of the regulations by the FPs Inadequate regulations (such as working hours of FPs until 12 in morning) Delayed payments to the FP Spending the allocated budget for other purposes |

| Mehrolhassani et al. (2021)[14] | Hasty implementation of the program without addressing the infrastructure Lack of necessary software Lack of strong information technology infrastructure Lack of access to Internet in the offices Lack of proper health-based and preventative health care education for FPs Neglecting culture building and lack of acculturation Insufficient attempts to properly introduce the program and provide sufficient information to the public Long delay (years) in payment of the approved budget for the UFPP Multiple insurance organizations and policies The payment and service purchase system: “per capita” payment to the family physicians and their teams as and “single payment” for levels 2 and 3. | Government transitions lead to new plans regardless of previous efforts Government transitions lead to the replacement of policy-makers Considering political factors instead of expertise-oriented factors for selecting officials Lack of a well-considered plan for health, treatment, and health education (the education system failed to prepare the family physician) No effective interaction between different levels of the referral system Weakness of inter- and intra-sectoral communication |

| Dehnavieh et al. (2015)[7] | Hasty implementation of the program Starting the FPP before integrating the existing insurances Insufficient financial resources Lack of backup software for methods of payments Neglecting culture building and lack of acculturation Insufficient attempts to properly introduce the program and provide sufficient information to the public Insufficient number of physicians with the required skills and education Inappropriate physical space. Shortage and poor distribution of resources. Problems related to the patient’s electronic file. | Delay in payments Lack of a united leadership Weakness of financial processes Lack of effective supervision on payment methods in the cities Incomprehensive, confusing, and unclear laws and regulation Inappropriate communication between providers Long delay before sending out the memorandum and instructions Work overload of physicians |

| Lack of a coherent information bank Unclear methods of payment to other forces. | ||

| Shiyani et al. (2016)[16] | Weakness of health educational system in providing health-based training for family physicians and helping them develop the adequate skills and competency. | Lack of a united leadership and governance and fragmentation of health policy making Inadequate laws on the responsibilities of each sector Inadequate operation supervision of physicians’ and patients Chaos in the health system Neglecting the multi-disciplinary nature of the health system by policy makers Conflict of interests of the FPP with Ministry of Health Body, the physicians’ union and the private sector, prioritizing personal interests over community interests Using a top-down approach instead of a participatory approach Medicalization of management (selecting physicians as managers, which leads to management inefficiency and conflict of interest in the policy-making process) Prioritize the organizational perspective over the technical perspective |

| Bolbanabad et al. (2019)[13] | Lack of manpower and facilities for treating emergency patients Insufficient attempts to properly introduce the program and provide sufficient information to the public Neglecting the culture building process by the program managers No educational program for the health workers in FPP Providing treatment-based medical education in the universities Delay budgeting Insurance deductibles Not providing para clinical services in the centers Lack of adequate facilities in comprehensive health centers Lack of comprehensive and coherent health records Lack of the required infrastructure for electronic health record systems Failure to send correct information to higher levels Lack of health-oriented vision of insurance Lack of proper supervision structure in the insurance organization. | Frequent changes in FPP Lack of a proper monitoring and control mechanism Failure to follow the rules and instructions correctly Weakness in attracting cross-sectoral cooperation and inadequate cooperation of intra-departmental units |

| Farzad Far et al. (2018)[17] | Unclear payment methods Delays in payments Problem in providing the budget Insufficient attempts to properly introduce the program and provide sufficient information to the public Inconsistency of the general practitioner training curriculum with the FPP Treatment-based and not prevention-based education Lack of training and retraining for staff Insufficient number of medical centers and medical equipment. | Unclear job description Writing the program’s executive protocol with a one-dimensional view Lack of a clearly defined monitoring system Frequent change of management of the FPP |

| Kaskaldareh et al. (2021)[18] | Lack of IT specialists in the health care network Difficult access to the networks Low integration of the existing information systems Middleware bugs Lack of proper hardware and software Lack of budget. | Frequent change of management of the FPP Unclear payment methods Failure to register information because of a high number of clients Poor inter- and intra-sectoral cooperation |

| Damari et al. (2017)[19] | Lack of a united leadership and governance in the referral system Role conflict and ambiguity between the Ministry of Health and Medical Education and the Ministry of Cooperatives, Labour, and Social Welfare Weaknesses in inter-sectoral and intra-sectoral cooperation Weaknesses in multi-level service evaluation and monitoring | |

| Alaie et al. (2020)[20] | Lack of culture building (via educational systems and mass media such as TV) Lack of budget allocation Treatment-based education Inadequate budget for insurance. | Conflict of interests (physicians as policy makers with clear interest in the program, conflict of interests between the physicians and the specialists and between the Ministry of Health and Ministry of Cooperatives, Labour and Social Welfare) Lack of trans-sectoral perspective in health care decision making Lack of coordination between the treatment sector and prevention sector of the Ministry of Health Dependency of the progress of the program on individuals and governments Lack of a united management on a national level Lack of a national policy for tariff Neglecting the role of research in policy making One-dimensional approach to health policy making Lack of an effective cooperation between the Ministries of Health and Medical Education and the Ministry of Cooperatives, Labour and Social Welfare Using a top-down approach instead of a participatory approach Unclear job description |

| Hooshmand et al. (2020)[21] | No pilot before implementation of the main FPP Inadequate housing and welfare infrastructure for human resources Inadequate transportation facilities for human resources Lack of public awareness Inadequate training for service providers Lack of valid and reliable checklists for FPP assessment Delays in payment Inadequate criteria for per capita income definition Insurance deductibles. | Lack of inter- and intra-sectoral cooperation |

| Abedi et al. (2017)[15] | Hasty implementation of the program without proper assessment of the structure and resources Lack of human resources specially in the private sector Lack of proper training based on the program requirements Lack of a legal mechanism to ensure the needed office space for the family physicians in the private sector Inadequate number of facilities specially in the private sector No infrastructure for electronic health records Using a per capita model instead of a function-based model for payments to the health care team Lack of expert insurance inspectors to assess the function of physicians. | Insufficient regulations for the presentation and implementation of the service package of the FFP Lack of inter- and intra-sectoral cooperation |

Challenges associated with the structure of the FPP

Table 3 shows the challenges associated with the structure of the FPP. These fell into three broad categories: legal, administrative, and societal.

Table 3.

Challenges associated with the structure of FPP

| Theme | Subtheme | Categories |

|---|---|---|

| Legal structure | Laws and regulations | Incomprehensive and unclear rules |

| Cumbersome laws | ||

| Failure to comply with the rules | ||

| Policy making | Lack of trans-sectoral perspective in health care policy making | |

| Writing the program’s executive protocol with a one-dimensional view | ||

| Use of a top-down approach instead of a participatory approach | ||

| Prioritize the organizational perspective over the technical perspective | ||

| Lack of research in developing policy | ||

| Treatment-based instead of health-based approach | ||

| Administrative structure | Lack of a united stewardship and governance system in the health system for the FPP and fragmentation in policy making in the field of health | |

| Lack of cooperation | ||

| Role conflict and ambiguity between different sectors and stakeholders | ||

| Lack of continuity in the program leadership | ||

| Leadership issue | ||

| Quality control | ||

| Medicalization of management | ||

| Competing interest | ||

| Educational issues | ||

| Lack of a specified monitoring system | ||

| Inadequate efforts to facilitate the necessary cultural shift toward adoption of FPP | ||

| Social structure | Insufficient attempts of public educational systems and mass media such as TV to promote FPP | |

| Neglecting culture building and lack of acculturation |

Legal structure

Six studies addressed the challenges related to laws and regulations. Unclear rules, cumbersome laws, and failure to comply with the rules were among the problems identified.[9,13] Ambiguity in the rules addressing the implementation of the FPP resulted in both an excessive workload of physicians and inequity and inaccessibility of care because of the scheduling of physician work hours.[7,9,15,18] There was also inadequate clarity of rules and regulations to identify the specific roles and responsibilities of each sector and stakeholder.[16]

Not only these outcomes but the process of the policy-making itself showed a number of problems. The lack of a trans-sectoral perspective in health care policy making, writing the program's executive protocol with a one-dimensional view, using a top-down approach instead of a participatory approach, prioritizing the organizational perspective over the technical perspective, the lack of research in developing policy, and applying a treatment-based approach instead of a health-based one are some of the examples identified.[8,16,17,20]

Administrative structure

Challenges within the administrative structure included fragmentation, role conflict, competing interests, leadership issues, and quality control.

The lack of a united stewardship and governance system in the health system for the FPP and fragmentation in policy-making in the field of health were the main challenges reported.[5,7,17,19,20] The lack of cooperation was also noted[5,13,15,18,19,21] between MoHME and MCLSW, between the treatment and the prevention sector inside the MoHME, between different levels of the referral system, and between individual service providers.[7,14,20]

Role conflict and ambiguity between different sectors and stakeholders were other challenges.[17,19,20] Role conflict between the MoHME and the MCLSW and the lack of transparency and clarity about authorities responsible for the implementation of the FPP are some of the examples.[19] There were conflicting interests between different stakeholders. There were conflicts between family physicians and specialists, between MoHME and MCLSW, between the Association of Physicians and the private sector, and between the relative priorities of individuals’ interests over collective interests.[16,20]

A lack of continuity in the program leadership was identified. There were frequent changes in the management of the FPP.[13,17,18] In Iran, the programs and plans have been dependent upon the individuals and managerial personal decisions,[20] and the government/management transition has led to the change of policymakers and the creation of new plans, which disregard previous efforts.[14] Adding to this issue of leadership was an emphasis on political factors, instead of expertise-oriented considerations, for selecting officials, which led to appointing authorities without the required experience and expertise for the FPP management.[14] Another problem in this area was the medicalization of management, that is, selecting clinicians as managers, which led to inefficient management. It also presented a conflict of interest in policy-making: The interests of the physicians appointed as managers were directly influenced by the policies they made.[16]

Six studies addressed a lack of quality control. There was no specified monitoring system, weak multi-level service evaluation and monitoring, inadequate operational supervision of physicians and patients, and a lack of effective supervision of diverse methods of payments in the urban FPP.[7,13,16,17,19] There were no valid and reliable checklists for FPP assessment,[21] and expert insurance inspectors to assess the performance of physicians were lacking.[15]

Other quality issues were related to the educational system. The FPP requires health and prevention-based approaches to training, but the general practitioners involved in the program had received treatment-based training. There was no proper training or re-training based on the program's needs.[13,15,17,20,21] Dehnavieh et al. and Shiyani et al. showed that the training program has failed to equip the family physicians with the required skills and competency for the FPP.[7,16]

Social structure

Inadequate efforts to facilitate the necessary cultural shift toward the adoption of FPP were another structural problem.[7,8,13,14,17,20,21] There was little buy-in by either the general public or specialist physicians. Many patients insisted that the FPs make unnecessary referrals to specialists. There was also active opposition to the program by many specialists.[9] The public did not have access to accurate and comprehensive information about the benefits and features of FPP.[5] The capacities of the public education system and mass media such as TV to promote the program had not been fully utilized.[20]

Challenges associated with the infrastructure of the FPP

Shown in Table 4 are the infrastructural challenges to the FPP. There were shortfalls in computational, physical, human, and financial resources.

Table 4.

Challenges associated with infrastructure in FPP

| Theme | Subtheme | Categories |

|---|---|---|

| Computational resources | Lack of health electronic records | |

| Fragmented information databases | ||

| Difficulty accessing networks | ||

| Lack of proper hardware and software | ||

| Middleware bugs | ||

| Lack of IT specialists in the health care sector | ||

| Physical resources | Inadequate physical space | |

| Lack of necessary equipment | ||

| Misdistribution of resources | ||

| Lack of welfare and transportation facilities for human resources | ||

| Human resources | Shortage of human resources | |

| Financial resources | Inappropriate health insurance system | Lack of fund pooling |

| A fragmented health insurance system | ||

| Lack of a backup software for payment methods | ||

| Inappropriate insurance deductibles | ||

| Absence of a public insurance scheme | ||

| Delayed reimbursements | ||

| Lack of health-oriented vision of insurance | ||

| Lack of a proper supervision structure in the insurance organization | ||

| Unclear methods of payment | ||

| Per capita payment instead of function-based payment to the health team | ||

| Inadequate criteria for per capita income definition | ||

| Financial challenges | Inadequate and delayed budgeting | |

| Rational medical tariffs based on relative value of health services | ||

| Weak accounting practices |

Computational resources

The main infrastructure challenge was related to information technology (IT). Effective implementation of the FPP requires a comprehensive and coherent health information system, accessible to all levels of referral and service providers. Studies reported a lack of health electronic records, fragmented information databases, difficulty accessing networks, a lack of proper hardware and software, middleware bugs, and a lack of IT specialists in the health care sector.[7,9,13,14,15,18] Compounding this was a lack of access to, or a low speed of, connection to the internet.

Physical resources

There was inadequate physical space.[7,14] The lack of a legal mechanism allocating the needed physical space for the FPP, especially in the private sector, was identified as the major reason.[15] In addition to facilities, necessary equipment was lacking, especially in the private sector.[13,15,17] This lack of resources has been exacerbated by the mal-distribution of resources.[7] Also lacking was housing, welfare, and transportation infrastructure for the physicians working in rural settings, which resulted in high rates of resignation.[21]

Human resources

These resignations exacerbated an already present shortage of human resources. The study by Abad et al. mentioned the lack of physician manpower to provide treatment of emergency patients and a lack of para-clinical services in family physician centers.[13]

Financial resources

The current health insurance system was not ready to embrace an enormous health system reform such as the FPP. There were shortfalls in insurance infrastructure, such as a lack of fund pooling, a fragmented health insurance system,[5,7,9,14] a lack of backup software for payment methods,[7] inappropriate insurance deductibles,[13,21] the absence of a public insurance scheme,[5] delayed reimbursements,[5,17,21] a lack of health-oriented vision of insurance,[13] a lack of a proper supervision structure in the insurance organization,[13] unclear methods of payment,[7,17,18] per capita payment instead of function-based payment to the health team,[14,15] and inadequate criteria for per capita income definition.[21]

Additional financial challenges included inadequate and delayed budgeting.[7,13,14,17,18,20] Doshmangir et al. identified underestimation of the required funds, diversion of the allocated budget for purposes other than the FPP, spending of the allocated finances by entities other than those responsible, the lack of clear and stable financial resources for the program,[5] no rational medical tariffs based on the relative value of health services, and weak accounting practices.[5,7,9,20]

Discussion

The FPP, an evidence-based intervention to achieve health equity and efficiency,[22,23,24,25] was established in Iran 2 decades ago in rural areas and about 1 decade ago in two provinces of Iran (Mazandaran and fars). Although it was considered a revolutionary reform,[26,27] in Iran's health system, it was not able to achieve the desired impact; in some provinces, it even could not go beyond the limited pilot phase. In most provinces of Iran, the program was not expanded to urban areas with a population more than 20,000 individuals, except in two provinces of Mazandaran and Fars, which was expanded to the whole urban and rural areas; however, in these two provinces, there was a shift and modification in the payment and referral system.[28]

Several investigations of the reasons behind this failure were undertaken and assessed the challenges of the program implementation.[7,8,9,10,11,12] On many occasions, failure in program implementation is rooted in poor planning and inadequate provision of the necessary structure and infrastructure.[29] This systematic review was designed to collate and summarize these issues related to the structure and infrastructure of FPP in Iran for the first time. The infrastructure related to electronic health records, electronic referral system, inappropriate and incomplete support of all the insurance systems from the FPP, and the lack of a comprehensive pooling system for all insurance systems are examples of these issues and challenges.

Previous studies showed that the hasty implementation led to initiation of the program without assessing the required structure, resources, and infrastructures.[7,14,15] Therefore, the FPP suffered from many structural weaknesses from the outset. Some of the main structural challenges identified are related to law and regulation. There is no regulation that obliged the insurance coverage for the FPP program, and also, there is confusion in the stewardship and inter-sectoral collaboration between the main leading organizations like MHME and social security organization. Strong governance and clear laws and regulation in other countries led to the successful implementation of the FPP.[30]

The poor administrative structure was also identified as a challenge in the main structure of FPP in Iran. The service package and guidelines are not clear, and the referral from the primary to secondary referral level is challenging as the management and administration are different at the primary level (Deputy of Health) and secondary level (Deputy of Treatment). Also, there is a dual and different monitoring and evaluation system by social security organization and MHME that created confusion and resulted in the violation of the rights of FPs in one hand and people's rights on the other hand. No mechanism was defined to monitor the ongoing program, while the fragmented leadership increased the confusion in the supervision and monitoring process.[19,31] Mohammadibakhsh et al. suggested that strengthening the control tools such as laws and regulations and the financing and payment system can have a “significant synergistic effect” on the success of the FPP program.[32]

Foundational issues such as the educational needs of the family physicians, raising public awareness, and cultural context were neglected in this program.

Because of the poor knowledge related to the benefit of FPP, people consider the FPP to be a factor in denying the freedom of self-referral to specialists, and there is resistance against this program, like the protests to the mandatory referral in Fars and Mazandaran provinces, which led to the withdrawal/change in the referral law in Fars province.

Although complementary and continued education has been held for a group of GPs that work at the FPPs, not all FPs have received the required training and have no motivation to attend training because the payment mechanism does not have a clear relationship with their knowledge, attitude, and performance. Some studies have shown that medical education in Iran is perceived as irrelevant by the community to its social needs and does not consider public demands or participation.[33,34] Education of the public and physician education specifically focused on the competencies needed for their role in FPP are areas of opportunity for significant improvement.

All these structural weaknesses in the FPP were because of policy-making which had a one-dimensional view, with a top-down approach that lacked a trans-sectorial and technical perspective.[8,16,17,20] Practically, the enforcers and implementers of this law at the level of the universities did not and do not have a meaningful presence in the program policy-making; for this reason, there is no strong executive support in the universities for the serious implementation of the plan, and the quality of the implementation process depends on the nature of the people and not the determined policies.

Among the required infrastructures for this program, that related to IT was identified as one of the main challenges. The lack of comprehensive and coherent health records, poor internet connection in many areas, the lack of required hardware, and software and firmware bugs were among the reported challenges, along with insufficient and inadequate IT specialists employed in the health care sector.

The IT infrastructure is necessary for providing an accurate medical registry to facilitate follow-up, feedback, and reverse feedback processes. Many studies reported poor follow-up, feedback, and reverse feedback in the FPP,[19,35,36,37,38] which can be attributed to the lack of the required IT infrastructure. Studies show that an information system is necessary to achieve health goals. It could guide a proper performance-based budget allocation, monitoring, and evaluation of the program and increase the program's accountability and transparency. This improves the quality of care and reduces the patient's risk and medical errors.[30,39,40]

Poor and insufficient provision of resources including human, financial, physical space, welfare, and equipment was another infrastructural challenge. In the FPP, the number of FPs seems to be sufficient for now, but we have a relative shortage of psychologists, nutrition experts, and health care workers in some areas. In addition, because of the disproportionate increase in per capita payment compared to the existing inflation, there is practically no or little incentive for FPs to work in this system, especially in deprived and remote areas. Therefore, in the future, the country faces a shortage of FPs, especially in remote and deprived areas. No program can be successful without its required resources.[32]

Many infrastructural challenges of the FPP in Iran were related to the insurance system. Unfortunately, the insurance coverage of this program was limited to very few schemes and did not include many other existing insurance systems.[35,41,42] Experiences of other countries show that “tax-based financing and social insurance” can provide a more sustainable financial resource for FPP and lead to better performance.[32] However, in Iran, the general insurance funds have not yet been aggregated and consolidated.

Skilled leadership and continuity of leadership over time were significant shortcomings in the program. There is a high shift and turnover at the leadership and managerial level in insurance organizations and ministerial and medical university levels. With each change of leadership, institutional memory suffered and lessons needed to be re-learned.

Conclusions

Many of the challenges noted in the present study were not apparent until a systematic retrospective study of reasons for the failure was undertaken. This precluded meaningful adaptation and correction of problems in “real-time”.

The FPP is a long-term plan, and its results are determined over time; the results are not immediately apparent. The legal obligation to enforce the regulations related to referral, and service packages, without prejudice is crucial for the success of the implementation of the program. Persistent efforts in pursuing the program goals by all stakeholders are essential in order for the program to realize its full potential. Studies such as those identified by this review should continue to be undertaken to allow ongoing identification and correction of challenges facing the program to allow FPP to blossom in Iran as it has elsewhere.

Financial support and sponsorship

This systematic review was supported by the Deputy of Health, Ministry of Health and Medical Education and the World Health Organization, Iran Office under the grant number 202640666.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Murray CJ, Frenk J. A framework for assessing the performance of health systems. Bull World Health Organ. 2000;78:717–31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization (WHO). Conceptual and strategic approach to family practice: Toward universal health coverage through family practice in the Eastern Mediterranean Region. 2014. [Last accessed on 2021 Dec 27]. Available from: https://applications.emro.who.int/dsaf/EMROPUB_2014_EN_1783.pdf.

- 3.Van der Voort C, Van Kasteren G, Chege P, Dinant GJ. What challenges hamper Kenyan family physicians in pursuing their family medicine mandate.A qualitative study among family physicians and their colleagues? BMC Fam Pract. 2012;13:1–5. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-13-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization. The World Health Report 2003: Shaping the Future. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Doshmangir L, Bazyar M, Doshmangir P, Mostafavi H, Takian A. Infrastructures required for the expansion of FPP to urban settings in Iran. Arch Iran Med. 2017;20:589–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sajadi HS, Majdzadeh R. From Primary Health Care to Universal Health Coverage in the Islamic Republic of Iran: A Journey of Four Decades.Archives of Iranian Medicine (AIM) 2019:22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dehnavieh R, Kalantari AR, Sirizi MJ. Urban FPP in Iran: Challenges of implementation in Kerman. Med J Islam Repub Iran. 2015;29:303. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sarvestani RS, Kalyani MN, Alizadeh F, Askari A, Ronaghy H, Bahramali E. Challenges of FPP in urban areas: A qualitative research. Arch Iran Med. 2017;20:446–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fardid M, Jafari M, Moghaddam AV, Ravaghi H. Challenges and strengths of implementing urban FPP in Fars Province, Iran. J Educ Health Promot. 2019;8:36. doi: 10.4103/jehp.jehp_211_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hooshmand E, Nejatzadegan Z, Ebrahimipour H, Bakhshi M, Esmaili H, Vafaeenajar A. Rural family physician system in Iran: Key challenges from the perspective of managers and physicians, 2016. Int J Healthc Manag. 2019;12:123–30. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nejatzadegan Z, Ebrahimipour H, Hooshmand E, Tabatabaee SS, Esmaili H, vafaeeNajar A. Challenges in the rural family doctor system in Iran in 2013-14: A qualitative approach. Fam Pract. 2016;33:421–5. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmw033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Behzadifar M, Behzadifar M, Heidarvand S, Gorji HA, Aryankhesal A, Taheri Moghadam S, et al. The challenges of the family physician policy in Iran: A systematic review and meta-synthesis of qualitative researches. Fam Pract. 2018;35:652–60. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmy035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mohammadi Bolbanabad J, Mohammadi Bolbanabad A, Valiee S, Esmailnasab N, Bidarpour F, Moradi G. The views of stakeholders about the challenges of rural family physician in Kurdistan province: A qualitative study. Iran J Epidemiol. 2019;15:47–56. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mehrolhassani MH, Kohpeima Jahromi V, Dehnavieh R, Iranmanesh M. Underlying factors and challenges of implementing the urban FPP in Iran. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21:1336. doi: 10.1186/s12913-021-07367-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abedi G, Marvi A, Soltani Kentaie SA, Abedini E, Asadi Aliabadi M, Safizadehe Chamokhtari K, et al. SWOT analysis of implementation of urban FPP from the perspective of beneficiaries: A qualitative study. J Mazandaran Univ Med Sci. 2017;27:79–93. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shiyani M, Rashidian A, Mohammadi A. A study of the challenges of family physician implementation in Iran health system. Hakim. 2016;18:264–74. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Farzadfar F, Jafari S, Rahmani K, Valiee S, Bidarpour F, Molasheikhi M, et al. Views of managers, health care providers, and clients about problems in implementation of urban family physician program in Iran: A qualitative study. Sci J Kurd Univ Med Sci. 2017;22:66–83. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaskaldareh M, Najafi L, Zaboli R, Roshdi I. Explaining the barriers and deficiencies of a family physician program based on electronic health record: A qualitative research. TB. 2021;20:12–26. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Damari B, Vosough Moghaddam A, Rostami Gooran N, Kabir MJ. Evaluation of the urban family physician and referral system program in fars and Mazandran Provinces: History, achievements, challenges and solutions. SJSPH. 2016;14:17–38. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alaie H, Amiri Ghale Rashidi N, Amiri M. A qualitative analysis on family physician's program to identify the causes as well as challenges of the failure of program accomplishment. JHOSP. 2020;19:55–66. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hooshmand E, Nejatzadegan Z, Ebrahimipour H, Esmaily H, Vafaee Najar A. The challenges of the family physician program in the north east of Iran from the perspective of managers and practitioners working on the plan. JABS. 2019;9:1794–808. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Atun RA, Kyratsis I, Jelic G, Rados-Malicbegovic D, Gurol-Urganci I. Diffusion of complex health innovations-implementation of primary health care reforms in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Health Policy Plan. 2007;22:28–39. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czl031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stange KC, Jaén CR, Flocke SA, Miller WL, Crabtree BF, Zyzanski SJ. The value of a family physician. J Fam Pract. 1998;46:363–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Strasser R. Rural health around the world: Challenges and solutions. Fam Pract. 2003;20:457–63. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmg422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Siddiqi S, Kielmann AA, Khan MS, Ali N, Ghaffar A, Sheikh U, et al. The effectiveness of patient referral in Pakistan. Health Policy Plan. 2001;16:193–8. doi: 10.1093/heapol/16.2.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bayati M, Keshavarz K, Lotfi F, KebriaeeZadeh A, Barati O, Zareian S, et al. Effect of two major health reforms on health care cost and utilization in Fars Province of Iran: FPP and health transformation plan. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20:382. doi: 10.1186/s12913-020-05257-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.National Unit of Reform of Health System. The Status of Family Physician and Reform System. Tehran: Andishmand Publication; 2005. pp. 3–7. In Persian. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hatam N, Joulaei H, Kazemifar Y, Askarian M. Cost efficiency of the FPP in Fars province, southern Iran. Iran J Med Sci. 2012;37:253. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Carmichael DG. Project Management Framework. London: CRC Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cylus J, Richardson E, Findley L, Longley M, O’Neill C, Steel D. United Kingdom: Health system review. Health Syst Transit. 2015;17:1–126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mehtarpour M, Tajvar M. Policy analysis of family physician plan and referral system in iran using policy analysis triangle framework. Health-Based Res. 2018;4:31–49. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mohammadibakhsh R, Aryankhesal A, Jafari M, Damari B. Family physician model in the health system of selected countries: A comparative study summary. J Educ Health Promot. 2020;9:160. doi: 10.4103/jehp.jehp_709_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Deputy of Social Affairs, Ministry of Health and Medical Education. The Narration of the Socialization of Health in Iran. 2018 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Deputy of Social Affairs, Ministry of Health and Medical Education. Report of Socializing Health Conferences in Major Research Areas of Iran Health System [Google Scholar]

- 35.Golalizadeh E, Moosazadeh M, Amiresmaili M, Ahangar N. Challenges in second level of referral system in FPP: A qualitative research. J Med Counc IRI. 2012;29:309–21. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Khedmati J, Davari M, Aarabi M, Soleymani F, Kebriaeezadeh A. Evaluation of urban and rural FPP in Iran: A systematic review. Iran J Public Health. 2019;48:400–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Azami-Aghdash S, Tabrizi JS, Mohseni M, Naghavi-Behzad M, Daemi A, Saadati M. Nine years of publications on strengths and weaknesses of FPP in rural area of Iran: A systematic review. J Anal Res Clin Med. 2016;4:182–95. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Keshavarzi A, Kabir MJ, Ashrafian H, Rabiee SM, Hoseini S, Nasrollahpour Shirvani SD. An assessment of the Urban FPP in Iran from the viewpoint of managers and administrators. J Babol Univ Med Sci. 2017;19:67–75. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Busse R, Riesberg A. Health Care Systems in Transition: Germany. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe on behalf of the European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies. 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Health Council of Canada. Primary Health Care: A Background Paper to Accompany Health Care Renewal in Canada: Accelerating Change. 2005. [Last accessed on 2021 Dec 29]. Available from: https://www.ryerson.ca/openlearningmodules/Midwifery/Module1Lesson1/Webpage/2.44-BkgrdPrimaryCareENG.pdf.

- 41.Tavakoli F, Nasiripour A, Riahi L, Mahmoodi M. The effect of health policy and structure of health insurance on referral system in the urban FPP in Iran. J Healthc Manag. 2017;8:85–93. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Safizadehe Chamokhtari K, Abedi G, Marvi A. Analysis of the patient referral system in urban FPP, from stakeholders perspective using swot approach: A qualitative study. J Mazandaran Univ Med Sci. 2018;28:75–87. [Google Scholar]