Introduction

Sepsis – life threatening organ dysfunction in response to severe infection1 – affects more than 48 million of people globally each year.2 Early recognition and appropriate management improve sepsis outcomes. Although more than 30 years have passed since the first formal definition of sepsis and more than 15 years since the Surviving Sepsis Campaign (SSC) first published broadly-adopted management guidelines, the understanding of sepsis and its treatment continues to evolve rapidly. This article reviews the key history of and recent advances in sepsis treatment, including new research in the domains of antibiotics, fluids, vasopressors, and adjunctive therapies, such as corticosteroids and renal replacement therapy. We also highlight remaining areas of clinical uncertainty and areas for future research.

Definition

Sepsis, first formally defined in 1991,3 has since 2016 been defined according to the Third International Consensus Definition for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3) as life-threatening organ dysfunction caused by a dysregulated host response to infection.1 The organ dysfunction component of the definition may be operationalized as an increase of 2 or more points in the Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score. The SOFA score assesses the function of 6 major organ systems (neurologic, cardiovascular, respiratory, hepatic, renal, and hematologic) on a scale of 0 (no dysfunction) to 4 (most severe dysfunction).1 In the current definition, septic shock is defined as the presence of sepsis and circulatory, cellular, and metabolic abnormalities that are associated with a greater risk of mortality than sepsis alone (receipt of vasopressors and serum lactate greater than 2 mmoL/L in the absence of hypovolemia).1

Therapies

Because sepsis is a common, complex, and life-threatening illness, recommendations regarding treatments have often preceded research to understand their effectiveness and safety. Moreover, sepsis research of different designs conducted in different contexts has frequently produced conflicting results. Although supportive therapies like the administration of intravenous antibiotics, fluid, and vasopressors have been central to sepsis therapy for two decades, only in recent years has evidence from detailed studies of sepsis phenotyping and large, randomized clinical trials started to make clear the complex picture of how these simple-seeming therapies may affect sepsis outcomes.

Antibiotics

Since 2004, sepsis management guidelines have recommended initiation of antimicrobial therapy within an hour of presentation to patients with severe sepsis and septic shock. In 2006, Kumar and colleagues4 observed that, among 2,731 patients with septic shock at hospitals in Canada and the United States, each hour of delay in initiation of effective antimicrobial therapy was associated with a mean decrease in survival of 7.6% (95% CI, 3.6–9.9%).4 Similarly, a retrospective analysis of 28,150 patients with severe sepsis and septic shock5 found that the risk of mortality increases linearly for each one hour delay in antibiotic administration.5 After the New York State Department of Health required hospitals to follow protocols for early treatment of severe sepsis and septic shock in 2013, a study of 49,331 patients found that longer time to the administration of antibiotics was associated with higher risk-adjusted in-hospital mortality (odds ratio, 1.04 per hour).6 Results were similar among children presenting with sepsis.7

Although observational studies have consistently demonstrated an association between early antibiotic administration and improved outcomes for patients with sepsis and hypotension, results have been less consistent in studies of patients with sepsis without hypotension and in prospective randomized trials attempting to assess the causal effect of decreased time-to-antimicrobial therapy on sepsis outcomes. The PHANTASi (Prehospital Antibiotics against Sepsis) multicenter randomized trial examined whether prehospital administration of antibiotics increased survival for patients with sepsis, severe sepsis, or septic shock.8 The trial found that antibiotic administration in the ambulance did not improve survival regardless of illness severity. Interpretation of the trial, however, was limited by the small number of patients with shock, lower than expected mortality rate, and a significant number of randomization violations.8

Recent research has shifted focus to minimizing risks associated with antibiotic administration, particularly antibiotic stewardship and the optimal choice of antibiotic. The Surviving Sepsis Campaign Guidelines recommend initiating therapy with one or more antibiotics for patients presenting with sepsis or septic shock covering all likely pathogens and narrowing antibiotic coverage once a pathogen is identified.9 Questions about when to narrow empiric therapy remain unanswered. A recent study found that, among critically ill adults whose cultures ultimately grew methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), 98% of blood cultures demonstrated Gram positive cocci by 48 hours, whereas only 85% of respiratory cultures were positive by 48 hours.10 A similar study among critically ill adults whose cultures ultimately grew Gram-negative rods (GNRs)11 found that (1) 54.2% of respiratory cultures and 18.6% of blood cultures demonstrated resistance to ceftriaxone and (2) 87% of respiratory cultures and 85% of blood cultures that ultimately grew GNRs resistant to ceftriaxone had demonstrated growth by 48 hours.11 The rapid evolution of methods for early molecular identification of pathogens for patients with sepsis offers the potential to significantly expedite identification of the causal organism and facilitate early narrowing of antibiotic therapy in the near future.12

In current practice, most patients with septic shock receive empiric antibiotic therapy with activity against Pseudomonas aeruginosa and resistant GNRs.9,13 Anti-pseudomonal penicillins and cephalosporins are two of the most commonly administered classes of antibiotic for empiric coverage of resistant GNRs in patients with sepsis.9,13 Recent observational data has suggested that concurrent receipt of piperacillin-tazobactam and vancomycin may be associated with elevations in serum creatinine concentration and that receipt of cefepime or ceftazidime may cause neurotoxicity.14,15,16,17,18,19,20 Prospective randomized trials are urgently needed to compare effectiveness and safety of anti-pseudomonal penicillins versus anti-pseudomonal cephalosporins for initial empiric antibiotic therapy in patients with sepsis.

Intravenous Fluid Administration

In addition to antibiotics, the administration of intravenous (IV) fluid is a fundamental component of early sepsis management.21 The physiologic rationale for administering IV fluids to patients with sepsis and hypotension is to increase venous return, increase stroke volume and cardiac output, and increase organ perfusion and oxygen delivery to reverse tissue hypoxia. Despite tens of millions of patients receiving IV fluid therapy for sepsis over the last 20 years, our understanding of the optimal approach to fluid therapy in sepsis, overall and for specific subsets of patients, remains limited. Fundamental questions are only recently beginning to be answered regarding the optimal timing, dose, duration, and composition of IV fluid for patients with sepsis.22,23

The concept that early IV fluid administration might improve outcomes for patients with sepsis was first popularized by a 2001 study of early goal-directed therapy (EGDT) by Rivers et al.24 In this landmark trial, 263 patients presenting to a single ED with severe sepsis or septic shock were randomized to usual care or EGDT. In the usual care group, patients were to receive a central venous catheter and an arterial catheter, administration of 500 mL boluses of IV fluid every 30 minutes to achieve a central venous pressure of 8–12 mmHg, and vasopressor administration as required to achieve a mean arterial pressure goal of 65 mmHg. Patients in the EGDT group were to receive the same therapies plus central venous oxygen saturation monitoring (ScvO2) and, for patients with an ScvO2 less than 70%, transfusion of red blood cells to achieve a hematocrit of at least 30 percent and infusion of dobutamine. During the 6 hours of intervention, patients in the EGDT group received significantly more fluid than patients in the usual care group (4981 ± 2984 liters vs 3499 ± 2438 liters, P < 0.001), and more frequently received blood transfusion (64.1% vs 18.5%, P < 0.001) and inotropic support (13.7% vs 0.8%, P < 0.001). In-hospital mortality rates were significantly lower in the EGDT group compared to the usual care group (38% vs 46.5%, P = 0.009).24

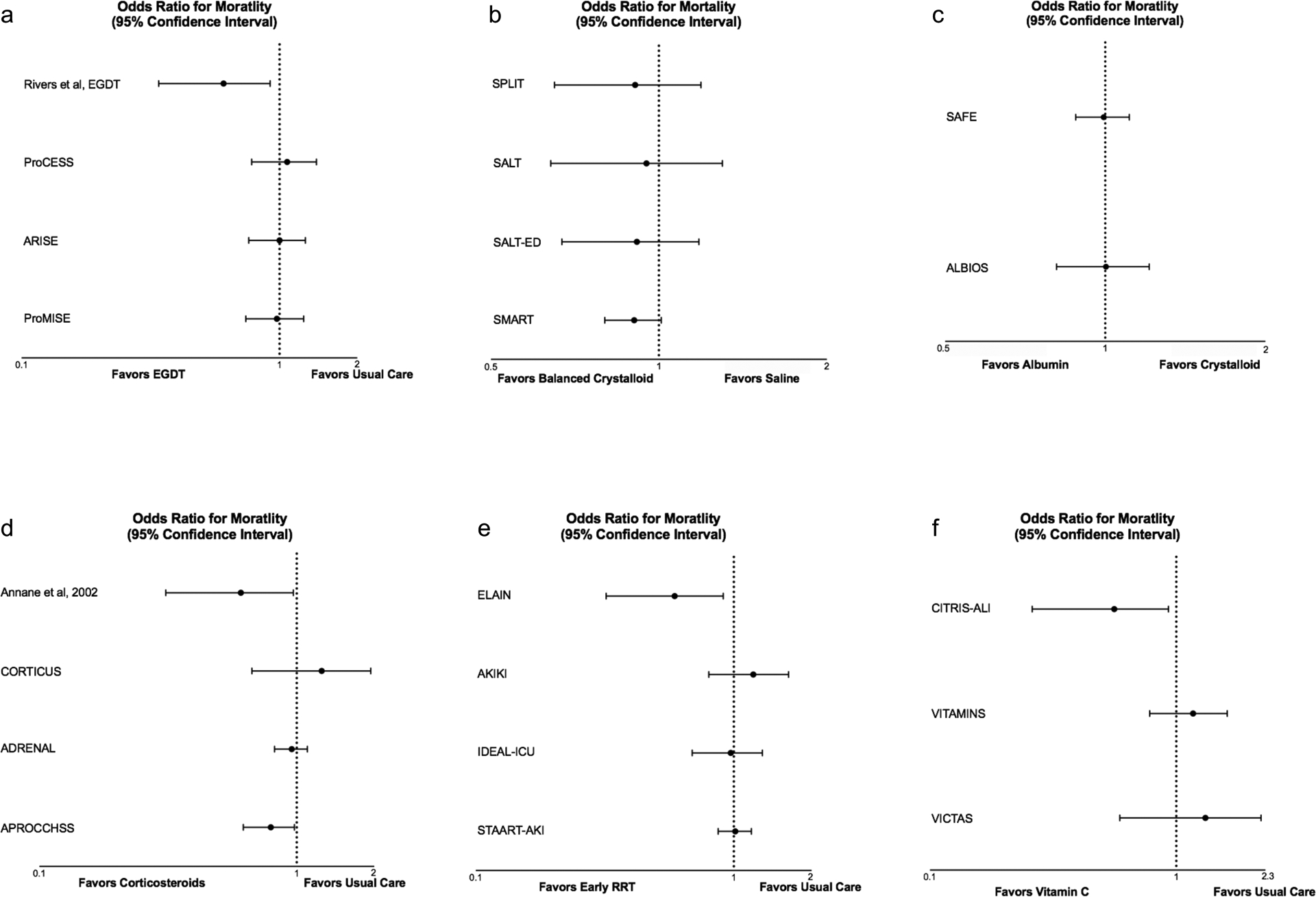

Based on the results of the Rivers EGDT study, and dozens of before-after studies of EGDT implementation, the Surviving Sepsis Campaign recommended fluid bolus administration as a foundational component of early sepsis management. Three subsequent large, multicenter trials, ProCESS,25 ARISE,26 and ProMISe27, randomized a combined 4201 patients to EGDT or usual care across 138 centers in 7 countries. Each of the three trials found no difference in clinical outcomes between EGDT and usual care (Figure 1a). A meta-analysis of the individual patient data did not identify benefit in any of the pre-specified subgroups.28 Several possible explanations exist for the difference in findings between the trial by Rivers et al and ProCESS, ARISE, and ProMISe trials. First, in the decade between the trial by Rivers et al and the subsequent three trials, the administration of IV fluid boluses for early sepsis became more common in usual care and the separation between groups in the volume of IV fluid received may not have been sufficient to contribute to differences in outcome in the subsequent three trials. Second, the trial by Rivers et al occurred in a single ED in a specific setting, and the average SvO2 values at presentation were much lower in this trial than in the subsequent three trials (e.g., 46.6 ± 11.2 in Rivers et al vs 71 ± 13 in ProCESS). This suggests that differences in patient population, severity, or phase of illness may have accounted for differences in the effect of early fluid therapy on outcomes. Third, the differences in outcomes between groups in the 263-patient single-center trial may have occurred due to chance imbalances.

Figure 1. Effect of sepsis therapies on mortality in large, randomized trials.

Odds ratios are unadjusted and calculated from raw data reported in trials unless specified otherwise.

Panel a – mortality from the Rivers and ProCESS trials are 60-day mortality, ARISE and ProMISE are 90-day mortality. ProMISE is an adjusted OR.

Panel b – SPLIT, SALT, SALT-ED and SMART show ORs for in-hospital mortality.

Panel c – SAFE and ALBIOS show ORs for 28-day mortality.

Panel d – Annane and CORTICUS report 28-day mortality in non-responders, ADRENAL and APROCCHSS report 90-day mortality. Annane and ADRENAL are adjusted ORs.

Panel e – ELAIN, STAART-AKI, and IDEAL-ICU report 90-day mortality, AKIKI reported 60-day mortality.

Panel f – CITRIS ALI and VITAMINS report 28-day mortality, VICTAS reported 180-day mortality.

Significant uncertainty remains regarding the optimal volume of IV fluid for patients with early sepsis and septic shock. In addition to the studies of EGDT in high-income countries, recent studies evaluating EGDT and fluid administration for infection in low- and middle-income countries have reported worse clinical outcomes with early IV fluid administration for patients with acute infection.29,30,31 How the results of these trials apply to the patient populations and care settings in high-income countries remains uncertain. The ongoing NHLBI PETAL Network’s CLOVERS trial (NCT03434028) is a large, multicenter, randomized trial comparing liberal vs restrictive IV fluid administration in early sepsis, the results of which may provide the first rigorous data comparing these common approaches to early sepsis fluid management.

In the absence of definitive evidence, guidelines differ in their recommendations. The most recent Surviving Sepsis Campaign Guidelines suggest early administration of 30 mL/kg IV fluid for septic shock or sepsis-induced hypoperfusion,9 whereas the guidelines from the American College of Emergency Physicians Take Force agrees with delivering an intravenous fluid bolus during the initial management of patients with hypotension or findings of hypoperfusion but does “not support a prespecified volume of body mass-adjusted volume of fluid for all patients.”32 While the optimal use of IV fluid boluses or vasopressors in early sepsis management remains unclear, the results of the ProCESS, ARISE, and ProMISe trials do make clear that many patients with early sepsis may be safely managed without invasive monitoring. In recent clinical practice, patients with sepsis and even septic shock on low doses of vasopressors are cared for without a central venous catheter or arterial catheter in many settings.33 Future research must address whether use of dynamic measures of fluid responsiveness, such as assessment of stroke volume change in response to a passive leg raise or stroke volume variation during invasive mechanical ventilation, can improve outcomes by balancing the risks and benefits of fluid therapy in early sepsis.

The choice of IV fluid composition for sepsis resuscitation has generated significant recent interest. Historically, the majority of the isotonic crystalloid solution administered to patients with sepsis has been saline (0.9% sodium chloride).34,35 Saline contains 154 mmol/L of sodium and chloride, whereas isotonic crystalloid solutions referred to as “balanced crystalloids” (e.g., lactated Ringer’s, Plasma-Lyte, Normosol) contain buffers and a chloride concentration more similar to that of plasma (98–112 mmol/L). The administration of solutions with high chloride concentrations has been associated with hyperchloremic metabolic acidosis, decreased renal perfusion, hypotension, and acute kidney injury.

Four recent randomized trials compared balanced crystalloids to saline among adults (Figure 1b). Two pilot trials, SPLIT (0.9% Saline vs Plasma-lyte 148 [PL-148] for ICU fluid therapy)36 and SALT (isotonic Solution Administration Logistical Testing),37 demonstrated the feasibility of comparing balanced crystalloids to saline among acutely ill adults. Two larger trials, the SMART (Isotonic Solutions and Major Adverse Renal Events Trial)38 and SALT-ED (Saline against Lactated Ringer’s or Plasma-Lyte in the Emergency Department)39 trials, compared saline to balanced crystalloids among ICU patients and ED patients, respectively. Among the 15,802 patients in the SMART trial, use of balanced crystalloid resulted in a lower rate of the composite outcome of death, new renal-replacement therapy, or persistent renal dysfunction, compared with use of saline. In the SALT-ED trial, among non-critically ill adults treated in the emergency department, there was no difference between groups in the primary outcome of hospital-free days, but fewer patients experienced death, new renal-replacement therapy, or persistent renal dysfunction in the balanced crystalloid group. A secondary analysis of the SMART trial dataset found that, among 1641 patients with a diagnosis of sepsis, use of balanced crystalloids was associated with an absolute risk reduction in 30-day in-hospital mortality of 4.9 percentage points, compared with saline.40 The effect of balanced crystalloids vs saline on mortality was greater among patients for whom fluid choice was controlled starting in the ED compared with patients for whom fluid choice was controlled starting in the ICU.41 These findings raise the hypothesis that the effect of fluid composition on clinical outcomes may be greatest during the initial phase of sepsis resuscitation, when the volume of fluid being administered is greatest, abnormalities in acid-base are most profound, and risk for the development of acute kidney injury is highest.

Although isotonic crystalloid solutions are the most common intravenous fluid administered to patients with sepsis, the potential benefits of colloid solutions have also been investigated. Two basic types of colloid solutions have been evaluated for patients with sepsis: human albumin solution, a purified blood product with oncotic and anti-inflammatory effects, and semi-synthetic colloid solutions, solutions with fluid, electrolytes, and synthesized high molecular weight molecules. The physiologic rationale for using colloids is the concept that high molecular weight molecules are more likely to retain fluid in plasma rather than moving into the interstitium and contributing to edema and end-organ dysfunction. Recent advances in understanding the manner in which the endothelial glycocalyx regulates the movement of proteins out of the plasma during health and its disruption during disease have raised questions about the applicability of the traditional Starling model of fluid dynamics, specifically whether resuscitation with colloids really requires significantly less fluid volume than resuscitation with crystalloids.

The first major trial to compare colloids to crystalloids among critically ill adults was the Saline versus Albumin Fluid Evaluation (SAFE) trial, which randomized 3497 adult ICU patients to receive 4% albumin and 3500 to receive 0.9% sodium chloride for fluid resuscitation.42 Mortality did not significantly differ between the albumin group (20.9%) and saline group (21.1%) overall (Figure 1c). In a subgroup analysis of patients with severe sepsis, however, the relative risk of 28-day mortality in the albumin group was 0.87, as compared with 1.05 among patients without severe sepsis (P value for interaction = 0.06). The subsequent Albumin Italian Outcome Sepsis (ALBIOS) trial randomized 1818 patients with severe sepsis or septic shock to crystalloid administration alone or crystalloid and 20% albumin (rather than 4% as in SAFE) in order to maintain a serum albumin level of 30 g/L.43 Patients in the albumin group experienced a lower heart rate, a higher mean arterial pressure, and lower net fluid balances. Death by day 28 or day 90 did not differ between groups – although a post hoc subgroup analysis suggested albumin might benefit patients with septic shock. Meta-analyses have suggested a potential improvement in mortality with albumin administration in patients with sepsis.44–45 The Surviving Sepsis Campaign Guidelines recommend crystalloids as the initial resuscitation fluid, but encourage consideration of albumin for patients who have received significant volumes of crystalloid. In the absence of definitive data suggesting that use of albumin improves outcomes, the high relative cost of albumin means crystalloid solutions are likely to remain the first-line therapy for fluid therapy in sepsis.

In an attempt to synthesize colloid solutions less expensive than albumin, starches, dextrans, and gelatins were developed and evaluated in a series of large, randomized trials. Together, these trials suggest that semi-synthetic colloids may cause acute kidney injury and should not be routinely administered to patients with sepsis.46,47,48,49

Vasoactive Therapy

Patients with sepsis who remain hypotensive after initial fluid resuscitation frequently receive vasopressors to maintain mean arterial pressure (MAP). Historically, dopamine was used as the first-line vasopressor for patients with septic shock. However, a large randomized trial demonstrated that dopamine is associated with more frequent adverse events (particularly tachyarrhythmias) than norepinephrine50 and a meta-analysis suggested that dopamine may be associated with an increased risk of death.51

If blood pressure cannot be maintained at goal with moderate doses of norepinephrine alone, a second vasopressor is often added. The most widely used second vasopressors are vasopressin, epinephrine, and angiotensin II. The Vasopressin and Septic Shock Trial (VASST) examined the addition of vasopressin to norepinephrine among 778 adults with septic shock.52 VASST found no decrease in mortality with use of vasopressin overall, but suggested lower mortality in a subgroup of patients who presented with less severe shock.52 Post-hoc analysis of the VASST trial suggested early administration of vasopressin might reduce the need for renal replacement therapy.52,53 The Vasopressin versus Norepinephrine as Initial Therapy in Septic Shock (VANISH) trial investigated this possibility. VANISH found that early vasopressin administration did not increase the number of renal-failure free days but might have decreased the receipt of renal replacement therapy.54 Several trials have examined use of vasopressin analogues such as terlipressin and selepressin. These trials found no difference in key clinical outcomes with selepressin and more serious adverse events associated with use of terlipressin.55,56 While the results of trials examining the effect of vasopressin on outcomes of septic shock are inconclusive, vasopressin decreases the required dose of norepinephrine and remains a commonly used second-line vasopressor.9,52

The newest vasopressor approved for treatment of distributive shock is angiotensin II, a potent endogenous vasoconstricting agent. After promising results in a pilot study,57 the Angiotensin II for the Treatment of High-Output Shock (ATHOS-3) trial randomly assigned patients with vasodilatory shock who were receiving more than 0.2 μg/kg/min norepinephrine or another vasopressor equivalent to receive an infusion of either angiotensin II or placebo.58 In this trial, patients assigned to angiotensin II were more likely to reach the primary end point, defined as increase in mean arterial pressure from baseline of at least 10 mmHg or an increase to at least 75 mmHg without an increase in the dose of background vasopressors at 3 hours.58 Whether use of angiotensin II improves clinical outcomes remains uncertain. How angiotensin II compares to the other available second-line vasopressors, such as vasopressin and epinephrine, remains a key clinical knowledge gap to be addressed in future research.

Other Supportive Therapies: Corticosteroids

Corticosteroid administration for patients with septic shock has been the subject of research and debate for decades. Overt adrenal insufficiency and relative adrenal insufficiency can occur in sepsis and septic shock but are difficult to recognize and diagnose.59 Administration of corticosteroids to patients with sepsis can increase blood pressure and improve vascular tone.60 Several large randomized trials have provided evidence regarding the effects of corticosteroid treatment on physiology and outcomes in septic shock (Figure 1d).

In 2002, Annane and colleagues performed a 300-patient randomized, double-blind, parallel group trial comparing 7 days of hydrocortisone and fludrocortisone to placebo.61 All patients underwent a 250-μg ACTH stimulation test. The primary analysis found that, among patients who did not experience an increase in cortisol of 9 micgrams/dL after ACTH administration, the 28-day mortality rate in the steroid group was lower than the placebo group (hazard ratio, 0.71; 95% CI, 0.52–0.97).61

In 2008, the Corticosteroid Therapy of Septic Shock (CORTICUS) multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial assigned patients with septic shock to receive either 50mg hydrocortisone or placebo every 6 hours for 5 days.62 They found that hydrocortisone administration was associated with a faster reversal of shock compared with placebo, but no change in mortality at 28 days. Steroid administration was also associated with more episodes of infection, hyperglycemia, and hypernatremia.62

In 2018, the Adjunctive Corticosteroid Treatment in Critically Ill Patients with Septic Shock (ADRENAL) trial randomized 3800 patients to receive 200mg/day of hydrocortisone via continuous infusion for 7 days or placebo. At 90 days, 511 patients (27.9%) in the hydrocortisone group and 526 (28.8%) in the placebo group had died (odds ratio, 0.95; 95% CI 0.82–1.10; P=0.50).63 The hydrocortisone group had faster resolution of shock and appeared to experience more days alive and not admitted to an intensive care unit.63

Also in 2018, the multicenter, double-blind, randomized Activated Protein C and Corticosteroids for Human Septic Shock (APROCCHSS) trial64 compared 50mg of hydrocortisone every 6 hours and 50μg fludrocortisone by mouth once daily to placebo (in addition to comparing activated drotrecogin alfa vs placebo in a factorial design).64 Among 1241 patients included in the trial, 90-day mortality was significantly lower in the hydrocortisone and fludrocortisone group (43%) than in the placebo group (49.1%) (relative risk, 0.88; 95% CI, 0.78 to 0.99).64 The treatment group also experienced more vasopressor-free days and organ-failure-free days. Hyperglycemia was more common in the treatment group but other adverse events did not differ.64

Although the optimal approach to steroid administration in sepsis remains uncertain and varies widely in current practice, the currently available data suggest that for patients with sepsis who are requiring moderate or high doses of vasopressors, administration of corticosteroids is a reasonable approach to decreasing catecholamine receipt, shortening the duration of shock, and potentially improving survival for some patients.

Other Supportive Therapies: Renal Replacement Therapy

Acute kidney injury is one of the most common complications of sepsis. When to initiate renal replacement therapy (RRT) for patients without urgent indications has been the subject of significant research (Figure 1e).65

The ELAIN randomized, single-center, parallel-group trial compared early initiation (within 8 hours of stage 2 AKI) versus delayed initiation (within 12 hours of stage 3 AKI or no initiation) of RRT for critically ill patients with KDIGO stage 2 AKI and plasma neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin level > 150 ng/mL.65 Early initiation of RRT appeared to reduce 90-day mortality (39.3%) compared with delayed initiation (54.7%) (hazard ratio, 0.66; 95% CI 0.45 to 0.97).65

The Artificial Kidney Initiation in Kidney Injury (AKIKI) multicenter, prospective, two-group randomized trial randomized 620 critically ill adults with AKI at least KDIGO stage 3 who were receiving mechanical ventilation, catecholamine infusion, or both to either early (within 6 hours) or delayed (up to 72 hours) initiation of RRT. A total of 250 of 311 patients in the early group and 244 of the 308 patients in the delayed group had a diagnosis of sepsis. Mortality was similar in the early and delayed initiation groups. Catheter-related bloodstream infections occurred more frequently in the early initiation group (10% vs 5%).66

The STARRT-AKI trial (Standard versus Accelerated Initiation of Renal-Replacement Therapy in Acute Kidney Injury) compared accelerated vs standard initiation of RRT among patients with stage 2 or 3 AKI by KDIGO classification.67 Among 3019 patients, 1689 (57.7%) of whom had a diagnosis of sepsis, death by 90 days occurred in 643 (43.9%) in the accelerated initiation group and in 639 (43.7%) in the standard initiation group (relative risk, 1.00; P=0.92).67 Significantly more adverse events occurred in the accelerated initiation group.67

The Initiation of Dialysis Early Versus Delayed in the Intensive Care Unit (IDEAL-ICU) randomized, open-label, multicenter trial compared early initiation (within 12 hours) versus delayed initiation (within 48 hours) of RRT for severe AKI in patients with early septic shock.68 The trial was stopped early for futility when 58% of the patients in the early initiation group and 54% of patients in the delayed initiation group had died.68

In concert, the results of these four large, multicenter, randomized trials demonstrate that nearly half of patients with AKI for whom RRT initiation is delayed ultimately do not require RRT and that early initiation of RRT may increase the risk of adverse events. Therefore, for most patients with sepsis and AKI, delaying initiation of RRT and carefully watching for the development of urgent indications appears to be the safest approach.

Other Supportive Therapies: High-Dose Vitamin C

Preclinical research has suggested that the administration of vitamin C may attenuate systemic inflammation, improve coagulopathy, and attenuate vascular injury in sepsis.69,70,71 Recent randomized clinical trials, however, have not demonstrated benefit from high-dose vitamin C administration in terms of clinical outcomes in sepsis (Figure 1f).72,73,74

Summary

Care for patients with sepsis has improved significantly over the last two decades. Early broad spectrum antibiotics for patients with sepsis-induced hypotension remain the cornerstone of management. Unanswered questions include the optimal choice of initial broad spectrum antibiotic and the approach to antibiotic de-escalation. With regard to fluid therapy, data from recent randomized trials suggest balanced crystalloids may produce better outcomes in sepsis than saline, and the role for albumin remains uncertain. The optimal volume of IV fluid in each phase of sepsis remains unknown. Whether dynamic measures of fluid responsiveness improve outcomes remains an urgent knowledge gap. Norepinephrine is the first-line vasopressor for patients with septic shock. When to initiate vasopressors and which vasopressor should be second line require additional research. Corticosteroids represent a reasonable adjunctive therapy in septic shock. Early renal replacement therapy and administration of vitamin C have not been shown to improve outcomes in sepsis. Research comparing the effectiveness of available therapies for sepsis and systems to reliably deliver evidence-based sepsis care have the potential to continue to improve sepsis outcomes in the future.

Clinics Care Points:

For most patients presenting with sepsis or septic shock, empiric broad spectrum antibiotics should be administered as soon as is feasible and narrowed after 48–72 hours as information on the causative organism becomes available.

Recent large, randomized trials found that use of balanced crystalloids may result in better outcomes than saline for patients with sepsis and septic shock; the role for albumin infusion remains uncertain.

For patients with septic shock, treatment with corticosteroids decreases the dose of catecholamines required to maintain blood pressure, increases the number of vasopressor-free days, and may decrease risk of death.

Early renal replacement therapy and high-dose vitamin C have been demonstrated to not improve clinical outcomes for patients with sepsis or septic shock.

Synopsis:

This review article summarizes current scientific evidence regarding the treatment of sepsis. We highlight recent advances in sepsis management with a focus on antibiotics, fluids, vasopressors, and adjunctive therapies like corticosteroids and renal replacement therapy.

Sources of Funding:

M.W.S. was supported in part by the NHLBI (K23HL143053).

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with the current work.

REFERENCES

- 1.Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, et al. The Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA. 2016;315(8):801. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.0287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rudd KE, Johnson SC, Agesa KM, et al. Global, regional, and national sepsis incidence and mortality, 1990–2017: analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study. The Lancet. 2020;395(10219):200–211. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32989-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Levy MM, Fink MP, Marshall JC, et al. 2001 SCCM/ESICM/ACCP/ATS/SIS International Sepsis Definitions Conference: Crit Care Med. 2003;31(4):1250–1256. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000050454.01978.3B [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kumar A, Roberts D, Wood KE, et al. Duration of hypotension before initiation of effective antimicrobial therapy is the critical determinant of survival in human septic shock*: Crit Care Med. 2006;34(6):1589–1596. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000217961.75225.E9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ferrer R, Martin-Loeches I, Phillips G, et al. Empiric Antibiotic Treatment Reduces Mortality in Severe Sepsis and Septic Shock From the First Hour: Results From a Guideline-Based Performance Improvement Program. Crit Care Med. 2014;42(8):7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Seymour CW, Gesten F, Prescott HC, et al. Time to Treatment and Mortality during Mandated Emergency Care for Sepsis. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(23):2235–2244. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1703058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Evans IVR, Phillips GS, Alpern ER, et al. Association Between the New York Sepsis Care Mandate and In-Hospital Mortality for Pediatric Sepsis. JAMA. 2018;320(4):358. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.9071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alam N, Oskam E, Stassen PM, et al. Prehospital antibiotics in the ambulance for sepsis: a multicentre, open label, randomised trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2018;6(1):40–50. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(17)30469-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rhodes A, Evans LE, Alhazzani W, et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: International Guidelines for Management of Sepsis and Septic Shock. Crit Care Med. 2017;45(3):486–552. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000002255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Melling PA, Noto MJ, Rice TW, Semler MW, Stollings JL. Time to First Culture Positivity Among Critically Ill Adults With Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Growth in Respiratory or Blood Cultures. Ann Pharmacother. 2020;54(2):131–137. doi: 10.1177/1060028019877937 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Buell KG, Casey JD, Noto MJ, Rice TW, Semler MW, Stollings JL. Time to First Culture Positivity for Gram-Negative Rods Resistant to Ceftriaxone in Critically Ill Adults. J Intensive Care Med. 2021;36(1):51–57. doi: 10.1177/0885066620963903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim J-S, Kang G-E, Kim H-S, Kim HS, Song W, Lee KM. Evaluation of Verigene Blood Culture Test Systems for Rapid Identification of Positive Blood Cultures. BioMed Res Int. 2016;2016:1–6. doi: 10.1155/2016/1081536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Magill SS, Edwards JR, Beldavs ZG, et al. Prevalence of Antimicrobial Use in US Acute Care Hospitals, May-September 2011. JAMA. 2014;312(14):1438. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.12923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rutter WC, Burgess DR, Talbert JC, Burgess DS. Acute kidney injury in patients treated with vancomycin and piperacillin-tazobactam: A retrospective cohort analysis. J Hosp Med. 2017;12(2):77–82. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Long B, April MD. Are Patients Receiving the Combination of Vancomycin and Piperacillin-Tazobactam at Higher Risk for Acute Renal Injury? Ann Emerg Med. 2018;72(4):467–469. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2018.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carreno J, Smiraglia T, Hunter C, Tobin E, Lomaestro B. Comparative incidence and excess risk of acute kidney injury in hospitalised patients receiving vancomycin and piperacillin/tazobactam in combination or as monotherapy. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2018;52(5):643–650. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2018.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bellos I, Karageorgiou V, Pergialiotis V, Perrea DN. Acute kidney injury following the concurrent administration of antipseudomonal β-lactams and vancomycin: a network meta-analysis. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2020;26(6):696–705. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2020.03.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.O’Callaghan K, Hay K, Lavana J, McNamara JF. Acute kidney injury with combination vancomycin and piperacillin-tazobactam therapy in the ICU: A retrospective cohort study. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2020;56(1):106010. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.106010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Appa AA, Jain R, Rakita RM, Hakimian S, Pottinger PS. Characterizing Cefepime Neurotoxicity: A Systematic Review. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2017;4(4):ofx170. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofx170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boschung-Pasquier L, Atkinson A, Kastner LK, et al. Cefepime neurotoxicity: thresholds and risk factors. A retrospective cohort study. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2020;26(3):333–339. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2019.06.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Angus DC, van der Poll T. Severe Sepsis and Septic Shock. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(9):840–851. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1208623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Self WH, Semler MW, Bellomo R, et al. Liberal Versus Restrictive Intravenous Fluid Therapy for Early Septic Shock: Rationale for a Randomized Trial. Ann Emerg Med. 2018;72(4):457–466. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2018.03.039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Malbrain MLNG, Van Regenmortel N, Saugel B, et al. Principles of fluid management and stewardship in septic shock: it is time to consider the four D’s and the four phases of fluid therapy. Ann Intensive Care. 2018;8(1):66. doi: 10.1186/s13613-018-0402-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Emanuel R, Bryant N, Suzanne H, et al. Early Goal-Directed Therapy in the Treatment of Severe Sepsis and Septic Shock. N Engl J Med. Published online 2001:10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.The ProCESS Investigators. A Randomized Trial of Protocol-Based Care for Early Septic Shock. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(18):1683–1693. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1401602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.The ARISE Investigators and the ANZICS Clinical Trials Group. Goal-Directed Resuscitation for Patients with Early Septic Shock. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(16):1496–1506. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1404380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mouncey PR, Osborn TM, Power GS, et al. Trial of Early, Goal-Directed Resuscitation for Septic Shock. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(14):1301–1311. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1500896 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.The PRISM Investigators. Early, Goal-Directed Therapy for Septic Shock — A Patient-Level Meta-Analysis. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(23):2223–2234. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1701380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Andrews B, Semler MW, Muchemwa L, et al. Effect of an Early Resuscitation Protocol on In-hospital Mortality Among Adults With Sepsis and Hypotension: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2017;318(13):1233. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.10913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Andrews B, Muchemwa L, Kelly P, Lakhi S, Heimburger DC, Bernard GR. Simplified Severe Sepsis Protocol: A Randomized Controlled Trial of Modified Early Goal–Directed Therapy in Zambia*. Crit Care Med. 2014;42(11):2315–2324. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maitland K, Kiguli S, Opoka RO, et al. Mortality after Fluid Bolus in African Children with Severe Infection. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(26):2483–2495. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1101549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yealy DM, Mohr NM, Shapiro NI, Venkatesh A, Jones AE, Self WH. Early Care of Adults With Suspected Sepsis in the Emergency Department and Out-of-Hospital Environment: A Consensus-Based Task Force Report. Ann Emerg Med. Published online April 2021:S0196064421001177. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2021.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cardenas-Garcia J, Schaub KF, Belchikov YG, Narasimhan M, Koenig SJ, Mayo PH. Safety of peripheral intravenous administration of vasoactive medication: Peripheral Administration of VM. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(9):581–585. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hammond NE, Taylor C, Finfer S, et al. Patterns of intravenous fluid resuscitation use in adult intensive care patients between 2007 and 2014: An international cross-sectional study. Moine P, ed. PLOS ONE. 2017;12(5):e0176292. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0176292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McIntyre L, Rowe BH, Walsh TS, et al. Multicountry survey of emergency and critical care medicine physicians’ fluid resuscitation practices for adult patients with early septic shock. BMJ Open. 2016;6(7):e010041. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Young P, Bailey M, Beasley R, et al. Effect of a Buffered Crystalloid Solution vs Saline on Acute Kidney Injury Among Patients in the Intensive Care Unit: The SPLIT Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2015;314(16):1701. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.12334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Semler MW, Wanderer JP, Ehrenfeld JM, et al. Balanced Crystalloids versus Saline in the Intensive Care Unit. The SALT Randomized Trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;195(10):1362–1372. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201607-1345OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Semler MW, Self WH, Wanderer JP, et al. Balanced Crystalloids versus Saline in Critically Ill Adults. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(9):829–839. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1711584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Self WH, Semler MW, Wanderer JP, et al. Balanced Crystalloids versus Saline in Noncritically Ill Adults. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(9):819–828. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1711586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brown RM, Wang L, Coston TD, et al. Balanced Crystalloids Versus Saline in Sepsis: A Secondary Analysis of the SMART Trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. Published online August 27, 2019:rccm.201903–0557OC. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201903-0557OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jackson KE, Wang L, Casey JD, et al. Effect of Early Balanced Crystalloids Before ICU Admission on Sepsis Outcomes. Chest. Published online August 2020:S0012369220342951. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.08.2068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.A Comparison of Albumin and Saline for Fluid Resuscitation in the Intensive Care Unit. N Engl J Med. Published online 2004:10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Caironi P, Tognoni G, Masson S, et al. Albumin Replacement in Patients with Severe Sepsis or Septic Shock. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(15):1412–1421. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1305727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rochwerg B, Alhazzani W, Sindi A, et al. Fluid Resuscitation in Sepsis: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161(5):347. doi: 10.7326/M14-0178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bansal M, Farrugia A, Balboni S, Martin G. Relative Survival Benefit and Morbidity with Fluids in Severe Sepsis - A Network Meta-Analysis of Alternative Therapies. Curr Drug Saf. 2013;8(4):236–245. doi: 10.2174/15748863113089990046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Brunkhorst FM, Meier-Hellmann A, Moerer O, et al. Intensive Insulin Therapy and Pentastarch Resuscitation in Severe Sepsis. N Engl J Med. Published online 2008:15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Guidet B, Martinet O, Boulain T, et al. Assessment of hemodynamic efficacy and safety of 6% hydroxyethylstarch 130/0.4 vs. 0.9% NaCl fluid replacement in patients with severe sepsis: The CRYSTMAS study. Crit Care. 2012;16(3):R94. doi: 10.1186/11358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Myburgh JA, Finfer S, Bellomo R, et al. Hydroxyethyl Starch or Saline for Fluid Resuscitation in Intensive Care. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(20):1901–1911. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1209759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Perner A, Haase N, Guttormsen AB, et al. Hydroxyethyl Starch 130/0.42 versus Ringer’s Acetate in Severe Sepsis. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(2):124–134. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1204242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Daniel DB, Patrick B, Jacques D, et al. Comparison of Dopamine and Norepinephrine in the Treatment of Shock. N Engl J Med. Published online 2010:11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Melzer D Dopamine versus Norepinephrine in the Treatment of Septic Shock: A Meta-analysis. J Emerg Med. 2012;42(6):751. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2012.04.084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Russell JA, Hébert PC, Granton JT, Ayers D. Vasopressin versus Norepinephrine Infusion in Patients with Septic Shock. N Engl J Med. Published online 2008:11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gordon AC, Russell JA, Walley KR, et al. The effects of vasopressin on acute kidney injury in septic shock. Intensive Care Med. 2010;36(1):83–91. doi: 10.1007/s00134-009-1687-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gordon AC, Mason AJ, Thirunavukkarasu N, et al. Effect of Early Vasopressin vs Norepinephrine on Kidney Failure in Patients With Septic Shock: The VANISH Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2016;316(5):509. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.10485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Study Group of investigators, Liu Z-M, Chen J, et al. Terlipressin versus norepinephrine as infusion in patients with septic shock: a multicentre, randomised, double-blinded trial. Intensive Care Med. 2018;44(11):1816–1825. doi: 10.1007/s00134-018-5267-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Laterre P-F, Berry SM, Blemings A, et al. Effect of Selepressin vs Placebo on Ventilator- and Vasopressor-Free Days in Patients With Septic Shock: The SEPSIS-ACT Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2019;322(15):1476. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.14607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chawla LS, Busse L, Brasha-Mitchell E, et al. Intravenous angiotensin II for the treatment of high-output shock (ATHOS trial): a pilot study. Crit Care. 2014;18(5):534. doi: 10.1186/s13054-014-0534-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Khanna A, English SW, Wang XS, et al. Angiotensin II for the Treatment of Vasodilatory Shock. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(5):419–430. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1704154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Patel GP, Balk RA. Systemic Steroids in Severe Sepsis and Septic Shock. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185(2):133–139. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201011-1897CI [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Schumer W Steroids in the Treatment of Clinical Septic Shock: Ann Surg. 1976;184(3):333–341. doi: 10.1097/00000658-197609000-00011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Annane D, Sebille V, Charpentier C, et al. Effect of Treatment With Low Doses of Hydrocortisone and Fludrocortisone on Mortality in Patients With Septic Shock. :10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sprung CL, Singer M, Kalenka A, Cuthbertson BH. Hydrocortisone Therapy for Patients with Septic Shock. N Engl J Med. Published online 2008:14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Venkatesh B, Finfer S, Cohen J, et al. Adjunctive Glucocorticoid Therapy in Patients with Septic Shock. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(9):797–808. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1705835 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Annane D, Renault A, Brun-Buisson C, et al. Hydrocortisone plus Fludrocortisone for Adults with Septic Shock. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(9):809–818. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1705716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zarbock A, Kellum JA, Schmidt C, et al. Effect of Early vs Delayed Initiation of Renal Replacement Therapy on Mortality in Critically Ill Patients With Acute Kidney Injury: The ELAIN Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2016;315(20):2190. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.5828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gaudry S, Hajage D, Schortgen F, et al. Initiation Strategies for Renal-Replacement Therapy in the Intensive Care Unit. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(2):122–133. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1603017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.The STARRT-AKI Investigators. Timing of Initiation of Renal-Replacement Therapy in Acute Kidney Injury. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(3):240–251. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2000741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Barbar SD, Clere-Jehl R, Bourredjem A, et al. Timing of Renal-Replacement Therapy in Patients with Acute Kidney Injury and Sepsis. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(15):1431–1442. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1803213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Fisher BJ, Seropian IM, Kraskauskas D, et al. Ascorbic acid attenuates lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury*: Crit Care Med. 2011;39(6):1454–1460. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182120cb8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Fisher BJ, Kraskauskas D, Martin EJ, et al. Mechanisms of attenuation of abdominal sepsis induced acute lung injury by ascorbic acid. Am J Physiol-Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2012;303(1):L20–L32. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00300.2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Medical Respiratory Intensive Care Unit Nursing, Fowler AA, Syed AA, et al. Phase I safety trial of intravenous ascorbic acid in patients with severe sepsis. J Transl Med. 2014;12(1):32. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-12-32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Fowler AA, Truwit JD, Hite RD, et al. Effect of Vitamin C Infusion on Organ Failure and Biomarkers of Inflammation and Vascular Injury in Patients With Sepsis and Severe Acute Respiratory Failure: The CITRIS-ALI Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2019;322(13):1261. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.11825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Fujii T, Luethi N, Young PJ, et al. Effect of Vitamin C, Hydrocortisone, and Thiamine vs Hydrocortisone Alone on Time Alive and Free of Vasopressor Support Among Patients With Septic Shock: The VITAMINS Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2020;323(5):423. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.22176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sevransky JE, Rothman RE, Hager DN, et al. Effect of Vitamin C, Thiamine, and Hydrocortisone on Ventilator- and Vasopressor-Free Days in Patients With Sepsis: The VICTAS Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2021;325(8):742. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.24505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]