Abstract

Research conducted in the past 15 years has yielded crucial insights that are reshaping our understanding of the systems physiology of branched-chain amino acid (BCAA) metabolism and the molecular mechanisms underlying the close relationship between BCAA homeostasis and cardiovascular health. The rapidly evolving literature paints a complex picture, in which numerous tissue-specific and disease-specific modes of BCAA regulation initiate a diverse set of molecular mechanisms that connect changes in BCAA homeostasis to the pathogenesis of cardiovascular diseases, including myocardial infarction, ischaemia–reperfusion injury, atherosclerosis, hypertension and heart failure. In this Review, we outline the current understanding of the major factors regulating BCAA abundance and metabolic fate, highlight molecular mechanisms connecting impaired BCAA homeostasis to cardiovascular disease, discuss the epidemiological evidence connecting BCAAs with various cardiovascular disease states and identify current knowledge gaps requiring further investigation.

The branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs) — isoleucine, leucine and valine — are essential amino acids that are primarily derived from the diet, although they can also be generated de novo by the gut microbiota1,2. Beyond their role as building blocks for protein synthesis and the widely appreciated function of leucine as a nutrient stimulus for the serine/threonine protein kinase mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) complex3, the biochemical processing of BCAAs yields an array of metabolic intermediates, many of which have unique signalling properties that we are only now beginning to discover.

Increased circulating levels of the BCAAs were first identified >50 years ago in the foundational studies by Cahill and colleagues in individuals with obesity and insulin resistance4. With the widespread application of metabolomic profiling over the past decade, increased levels of BCAAs and related metabolites are now widely considered to be a metabolic hallmark of obesity, insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) in humans5,6. Metabolic disturbances are intimately involved in the pathogenesis of cardiovascular disease (CVD), and independent associations have emerged that support a direct role for BCAAs in heart failure (HF)7–9, vascular disease10,11, hypertension12 and arrhythmias13. Therefore, the link between BCAAs and CVD has become an area of intense interest in both the clinical and basic science arenas. Mechanistic work in this area is in its infancy, with models and tools requiring development in order to directly test the causal relationship between tissue-level disturbances in BCAAs and CVD. Nonetheless, efforts to expand our understanding of how BCAAs influence cardiovascular physiology have already identified promising new candidate molecular targets for treating CVD. In this Review, we outline the current understanding of the factors regulating BCAA abundance and metabolic fate, provide an in-depth discussion of the emergent mechanistic and epidemiological findings implicating altered metabolism of BCAAs in the aetiology of CVD and highlight important areas for future research.

Systems biology of BCAA metabolism

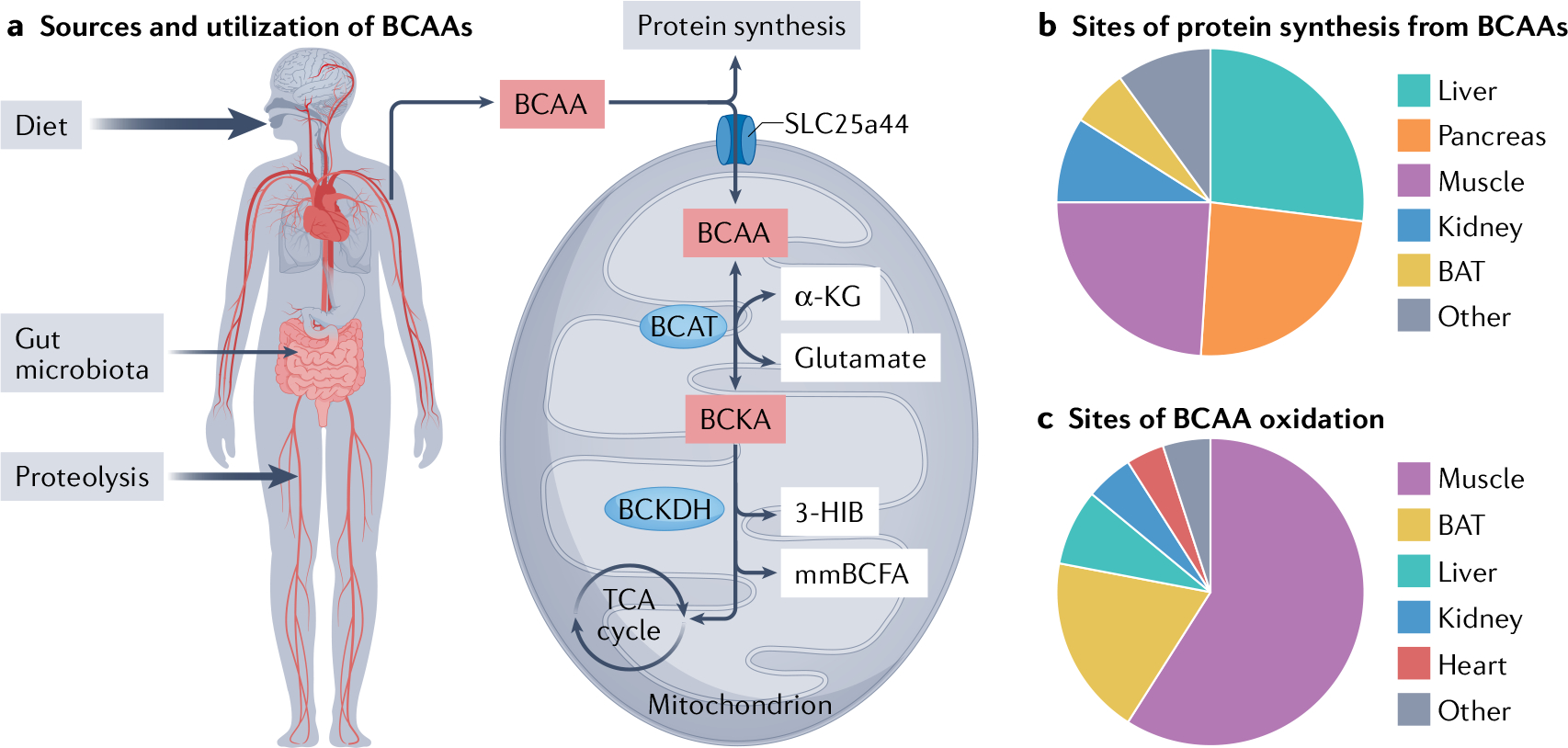

The circulating pool of BCAAs is determined by the rate of their release from proteolysis and their utilization in protein synthesis and oxidation. The BCAA oxidation pathway can terminate at the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle or earlier in the formation of intermediates that have paracrine signalling activity, such as 3-hydroxyisobutyrate (3-HIB)14, or that are used for the generation of monomethyl branched-chain fatty acids (mmBCFAs)15. How the balance of these outcomes is controlled is currently unclear. BCAA oxidation occurs in the mitochondria, after the BCAAs have been imported by the newly identified solute carrier, SLC25a44 (REF.16). The initial enzymatic steps in the BCAA catabolic pathway are shared by isoleucine, leucine and valine. First, BCAAs undergo reversible transamination mediated by mitochondrial BCAA aminotransferase (BCAT2), yielding branched-chain α-keto acids (BCKAs). Second, the BCKAs undergo irreversible decarboxylation by the BCKA dehydrogenase (BCKDH) complex6. After multiple additional reactions, the BCAA catabolic pathway terminates in the generation of acetyl-CoA and succinyl-CoA and their oxidation in the TCA cycle or contribution via anaplerotic reactions to cellular biosynthetic pathways.

Important physiological roles are emerging for several intermediates of BCAA oxidation, including BCKA17, 3-HIB14 and mmBCFA15. Landmark tracing studies in mice have demonstrated that the major sites of BCAA oxidation are skeletal muscle (59%), brown adipose tissue (19%), liver (8%), kidney (5%) and heart (4%), whereas the major sites of BCAA incorporation into protein are the liver (27%), pancreas (24%), skeletal muscle (24%), kidney (9%) and brown adipose tissue (6%)18 (FIG. 1). Therefore, in addition to the direct influence of BCAAs and related metabolites on the heart, local defects in the BCAA metabolic pathway in the liver, fat and skeletal muscle could have a potent inter-organ effect on the cardiovascular system elicited by secondary factors such as adipokines, myokines or non-coding RNAs through exosome-mediated transfer.

Fig. 1 |. Major sources and sites of BCAA supply and utilization.

a | Branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs) — isoleucine, leucine and valine — are essential amino acids. The circulating pool of BCAAs is derived from the diet and proteolysis, with a smaller contribution from de novo synthesis by the gut microbiota. Circulating BCAAs are used for protein synthesis or are metabolized. BCAA are imported into the mitochondria by the mitochondrial BCAA carrier, SLC25a44. The first two steps in the BCAA catabolic pathway, mediated by the branched-chain amino transferase (BCAT) and the branched-chain α-keto acid dehydrogenase (BCKDH) enzymes, are shared for all three BCAAs. The catabolic pathway terminates at the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle, but also generates important metabolic intermediates, such as the valine metabolite 3-hydroxyisobutyrate (3-HIB) and the monomethyl branched-chain fatty acids (mmBCFAs), which contribute to intracellular and paracrine signalling. b | Major sites of BCAA incorporation into protein34. c | Major sites of BCAA metabolism34. α-KG, α-ketoglutarate; BAT, brown adipose tissue; BCKA, branched-chain α-keto acid.

Much insight has been gleaned from the study of systemic changes in BCAA metabolism in metabolic diseases6, such as maple syrup urine disease. This congenital syndrome is caused by rare mutations in the genes encoding BCAA metabolic enzymes and results in systemically impaired BCAA metabolism. However, how the various CVD states reshape systemic BCAA homeostasis is unclear. One common observation in the setting of HF is the coordinated downregulation of many genes encoding proteins in the BCAA oxidative pathway in the heart9. Consequently, it is tempting to speculate that increased circulating levels of BCAAs in CVD are simply reflective of intrinsic shifts in cardiac BCAA metabolism. However, the level of BCAA oxidation in the TCA cycle in the healthy heart is relatively low compared with the level at other major sites of BCAA oxidation, rendering this explanation unlikely17–19. Additionally, in terms of mass, the heart is a minor site of BCAA oxidation relative to other tissues, such as skeletal muscle and fat18. Therefore, impairments in non-cardiac BCAA oxidation are likely to be the source of increases in circulating BCAAs in CVD. Low levels of BCAA oxidation in the healthy heart can be attributed to high baseline inhibitory phosphorylation of the cardiac BCKDH complex responsible for the first, irreversible step in BCAA oxidation, and low expression of the newly identified mitochondrial BCAA carrier, SLC25a44 (REF.17). Therefore, rather than generating catabolic intermediates, an alternative fate of BCKAs is reamination to their cognate BCAAs, as shown by 13C tracing studies in isolated hearts from healthy rats17. Similarly, exposure of isolated cardiomyocyte mitochondria to BCKAs results in a substantial accumulation of BCAAs, indicative of active BCKA reamination in the heart20. This process does not occur in liver mitochondria, which lack the BCAT enzyme responsible for reamination20. These data suggest that CVD-mediated changes in the other tissue compartments regulating BCAA homeostasis, such as skeletal muscle, liver and adipose tissue (FIG. 1), are responsible for the rise in circulating BCAA levels in CVD. Therefore, a ‘spill-over’ model of BCAAs in CVD is proposed, in which altered BCAA metabolism in one compartment leads to increased exposure in another, such as the heart, with potential pathogenic consequences. Future studies surveying systemic and cellular changes in BCAA utilization across the various CVD states are needed to determine causal mechanisms. An exciting question still to be addressed is how do alterations in cardiovascular health influence systemic BCAA utilization?

Mechanisms linking BCAAs and CVD

Heart failure.

Human epidemiological studies primarily show an association between increased plasma BCAA concentrations in HF and adverse outcomes. Similarly, increased plasma levels of BCAAs are observed in some, but not all, animal models of HF. Serum metabolomics performed in rats with HF induced by myocardial infarction (MI) showed that BCAA concentrations discriminate between animals with HF and sham-operated controls and that serum BCAA concentrations increase progressively over time in parallel with worsening cardiac function21. These changes in circulating BCAA levels were accompanied by downregulation of the genes encoding proteins in the BCAA catabolic pathway in the heart and accumulation of cardiac BCAAs21. Likewise, in mice with MI-induced HF, cardiac BCAA concentrations were increased, accompanied by decreases in the abundance of BCAA catabolic enzymes in the heart, consistent with decreased BCAA metabolism over time22. However, no increases in circulating BCAA levels were observed22. HF induced by pressure overload via transaortic constriction (TAC) in mice leads to increases in cardiac BCKA concentrations, with downregulation of genes encoding proteins involved in BCAA catabolism9. Although plasma concentrations of BCAAs or BCKAs in these TAC mice were not reported, a human cohort of individuals with HF with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) was used to validate the findings in the mouse model, while also demonstrating an increase in circulating levels of α-keto-β-methylvalerate (the ΒCΚΑ of isoleucine)9. In another study in human patients with dilated cardiomyopathy, a marked increase in cardiac BCAA concentrations was found compared with controls, together with evidence of impaired BCAA metabolism demonstrated by decreased levels of mitochondrial protein phosphatase 1K (PPM1K) and BCAT2, with increased inhibitory phosphorylation of BCKDH23. Comparative metabolomics in mouse models of both TAC-induced and MI-induced HF also showed an increase in cardiac BCAA concentrations, but with no changes in plasma BCAA levels in either model24. In this study, cardiac BCAA levels positively correlated with cardiac insulin resistance and negatively correlated with cardiac function24. In 2022, findings were reported from a new ‘chemogenetic’ mouse model of HF, driven by cardiac delivery of adeno-associated virus (AAV9) expressing the yeast enzyme d-amino acid oxidase25. When animals are fed d-alanine, the enzyme generates hydrogen peroxide in the cardiomyocytes, leading to dilated cardiomyopathy. Unbiased transcriptomic and metabolomic profiling in this model of HF induced by oxidative stress found that BCAA catabolic enzyme gene expression was downregulated, with a concomitant increase in cardiac BCAA concentrations, but no change in plasma BCAA concentrations25. These animal models consistently demonstrate impaired cardiac BCAA metabolism and increased tissue concentrations of BCAAs as shared features of cardiac dysfunction, while increases in circulating BCAA levels, as is observed in humans with HF, are model-dependent. Interestingly, integrated omics studies comparing changes in cardiac metabolic pathways in mouse models of physiological (endurance training) and pathological (TAC) hypertrophy have found that downregulation of BCAA metabolism (akin to the well-d escribed reversion to the cardiac fetal gene programme9) seems to be a unique feature of cardiac injury not seen in physiological hypertrophy26,27.

A fundamental question relating to the mechanisms linking BCAAs and HF is how much does the increased delivery of BCAAs to the heart contribute to HF pathogenesis compared with perturbations in intrinsic cardiac BCAA metabolism? Using dietary BCAA supplementation, pharmacological manipulation of BCAA metabolism and genetic animal models, several studies have attempted to answer this question. In mice with MI, oral administration of BCAAs in the drinking water increases cardiac BCAA concentrations and worsens cardiac function compared with mice given normal water22. Mice lacking Ppm1k (also known as Pp2cm), encoding the protein phosphatase that activates BCKDH and therefore BCAA catabolism, have an increase in both plasma and cardiac concentrations of BCAAs and BCKAs compared with wild-type mice9,28. Ppm1k−/− mice also have a mild decline in cardiac function over time, with no obvious cardiac structural changes9. However, when Ppm1k−/− mice are exposed to cardiac stress in the form of TAC, they show accelerated progression of HF9.

The small-molecule allosteric inhibitor of BCKDH kinase (BDK), 3,6-dichlorobenzo[b]thiophene-2-carboxylic acid (BT2), is a powerful tool for studying the role of BCAA metabolism in various pathological conditions29. Just 1 week of BT2 administration leads to nearly complete dephosphorylation and maximal activation of BCKDH in the heart, skeletal muscle, kidneys and liver of mice29 and rats30, with reductions in plasma BCAA and BCKA concentrations. Likewise, BT2 rescues the BCAA catabolic defect seen in Ppm1k−/− mice and normalizes plasma BCAA and BCKA concentrations9. Several studies have now shown that BT2 treatment can delay HF progression in mice when administered at the onset of TAC9,22,23, and can stabilize cardiac function when administered 2 weeks after TAC31. The findings from these studies indicate that defective cardiac BCAA catabolism contributes to both HF pathogenesis and progression, given that impaired baseline cardiac BCAA catabolism (for example, in Ppm1k−/− mice) predisposes animals to worsened cardiac function under stress, and that restoration of cardiac BCAA catabolism (via BT2 treatment) improves cardiac function under stress. However, because these models use approaches that affect systemic BCAA metabolism, and therefore change both circulating and cardiac BCAA concentrations, the precise contribution of impaired cardiac-specific BCAA metabolism to cardiac dysfunction is unclear.

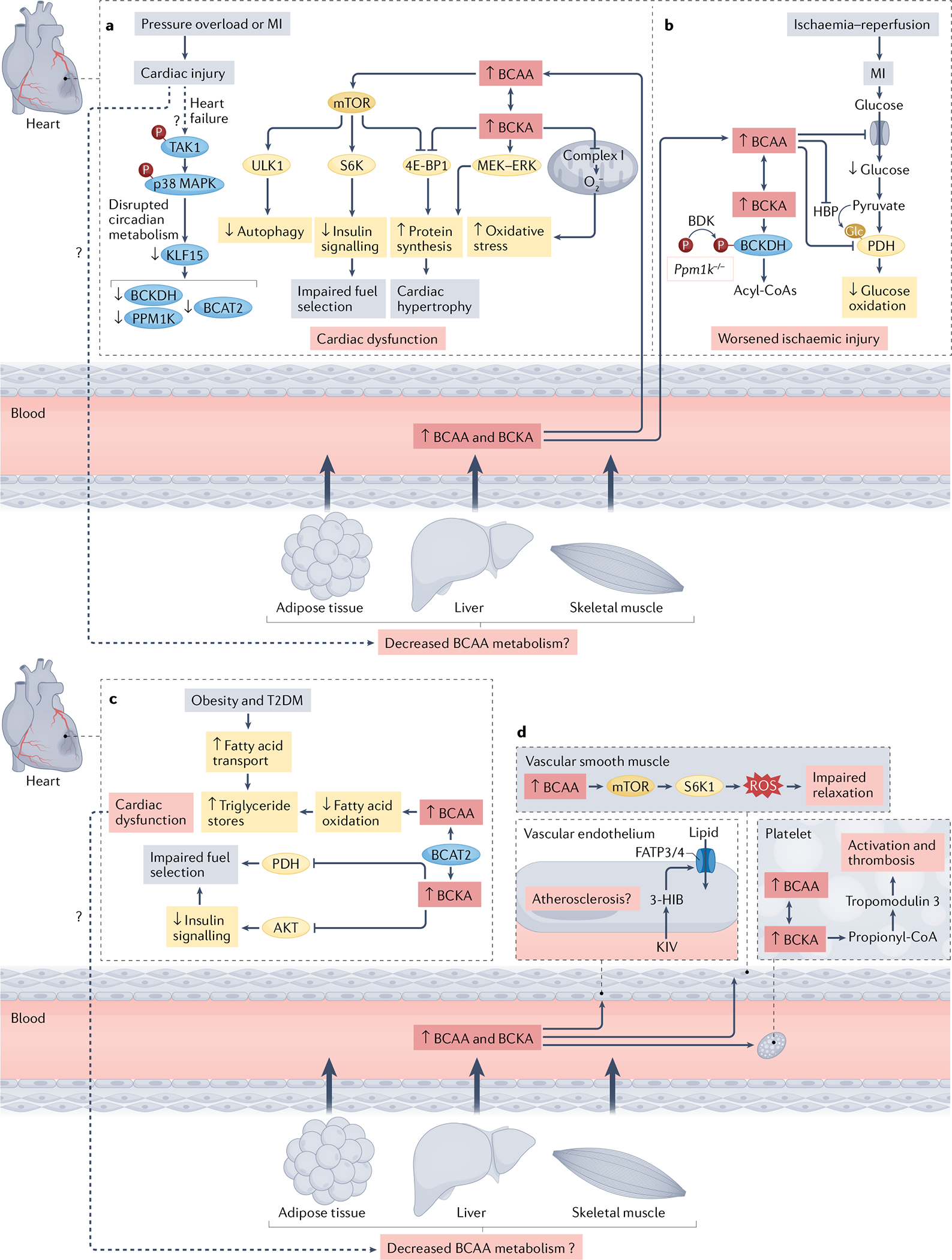

Several mechanisms have been proposed to connect impaired cardiac BCAA metabolism and accumulation of cardiac BCAAs with cardiac dysfunction (FIG. 2a). BCAAs are well known to be prime activators of mTOR, activation of which has been observed in HF induced by MI or pressure overload32. Oral supplementation with BCAAs after MI leads to worsening cardiac function in mice, accompanied by increased mTOR phosphorylation and decreased autophagy22. This decline in cardiac function can be prevented by concomitant treatment with the mTOR inhibitor rapamycin, implying mTOR-dependent deleterious effects of cardiac BCAAs22. Increased cardiac BCAA concentrations are also associated with mTOR activation — as measured by phosphorylation of mTOR and its downstream targets ribosomal protein S6 kinase-β1 (also known as P70S6K) and insulin receptor substrate 1 — in cardiac tissue from humans with dilated cardiomyopathy23. These changes are associated with decreases in phosphorylation of enzymes involved in insulin signalling, namely AKT (also known as protein kinase B) and glycogen synthase kinase 3, suggesting that BCAA-mediated mTOR activation might contribute to cardiac insulin resistance23. This finding is consistent with animal models of cardiac insulin resistance (mice fed a high-fat diet) that show decreased cardiac BCAA oxidation and increased cardiac BCAA concentrations19. Acute 30-min exposure of rat isolated hearts to concentrations of BCKAs that are the same as those observed in the plasma of individuals with HF is sufficient to activate protein translation, with a corresponding increase in phosphorylation of eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E-binding protein 1, which activates protein synthesis by inactivating the translation repressor function of this protein17. Acute exposure to BCKAs also causes widespread changes in the cardiac phosphoproteome, suggesting activation of the MEK–ERK mitogen-activated protein kinase signalling pathway, which has been implicated in the development of pathological cardiac hypertrophy17,33.

Fig. 2 |. Potential mechanisms connecting dysregulated BCAA metabolism with CVD.

a | In heart failure, the central circadian regulator of branched-chain amino acid (BCAA) metabolism, Krüppel-like factor 15 (KLF15), is downregulated via a mechanism involving transforming growth factor-β-activated kinase 1 (TAK1) and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signalling. This leads to decreased expression of BCAA metabolic enzymes, including mitochondrial BCAA aminotransferase (BCAT2), branched-chain α-keto acid dehydrogenase (BCKDH) and mitochondrial protein phosphatase 1K (PPM1K) and accumulation of BCAAs and branched-chain α-keto acids (BCKAs) in the heart. Cardiac injury also potentially impairs BCAA metabolism in peripheral tissues, resulting in increased circulating BCAA and BCKA levels, and therefore increased delivery of BCAAs and BCKAs to the heart. The BCAA leucine promotes activation of serine/threonine-protein kinase mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) in the heart, which blunts autophagy via serine/threonine protein kinase ULK1 (ULK1), promotes insulin resistance via serine phosphorylation of the insulin receptor substrate 1 mediated by ribosomal protein S6 kinase (S6K) and stimulates protein synthesis by phosphorylation of the translational repressor 4E-B P1. BCKAs also lead to increased phosphorylation of 4E-B P1 and induce the MEK–ERK mitogen-activated protein kinase signalling pathway, which promotes protein synthesis. Moreover, exposure to BCKAs impairs mitochondrial complex I activity in the heart, resulting in superoxide generation and oxidative stress. b | In ischaemia–reperfusion injury, whole-body deletion of Ppm1k in mice results in the accumulation of circulating and cardiac BCAAs and BCKAs. This accumulation leads to inhibition of glucose transport and oxidation via decreased O-linked N-acetylglucosaminylation (Glc) of pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH), and worsened ischaemic injury. c | In animal models of obesity and insulin resistance, BCAA accumulation decreases fatty acid oxidation and increases triglyceride stores. Exposure of the heart to concentrations of BCKAs observed in obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) inhibits AKT and PDH, resulting in impaired fuel selection. Whether these changes in substrate utilization result in cardiac dysfunction remains to be determined. It is also uncertain whether cardiac-intrinsic changes elicit alterations in BCAA metabolism in other tissues, such as the liver, skeletal muscle or adipose tissue. d | BCAAs impair vascular relaxation in an mTOR-dependent manner that involves reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation. BCAA oxidation in platelets promotes thrombosis by stimulating the propionylation of tropomodulin 3, which leads to platelet activation. The valine-derived metabolite 3-hydroxybutyrate (3-H IB), has been shown to increase transendothelial lipid transport dependent on solute carrier family 27 member 3 (FATP3) and long-chain fatty acid transport protein 4 (FATP4). Whether this BCAA–lipid interplay contributes to atherosclerosis remains to be determined. Dashed arrows in the figure depict pathways that are uncertain. BDK, branched-chain keto acid dehydrogenase kinase; HBP, hexosamine biosynthetic pathway; KIV, α-ketoisovalerate; MI, myocardial infarction.

Cardiac metabolism has a circadian pattern, such that ATP production is maximized during the wake cycle and remodelling and repair processes occur during the sleep cycle34. Perturbations in this circadian rhythmicity can lead to a host of cardiometabolic diseases, including HF35. Like other metabolic pathways, cardiac BCAA metabolism is under circadian regulation. In the heart, mTOR activity is at its peak during the awake-to-sleep transition, during which protein translation is increased36. Feeding mice a BCAA-rich diet at the end of the awake period augments this mTOR-mediated increase in protein translation, resulting in increased cardiac mass and cardiomyocyte size37. This BCAA effect is not observed when mice are concurrently treated with rapamycin or fed a BCAA-rich diet at the beginning of the awake period, whereas deletion of a crucial cardiomyocyte circadian gene — Arntl (also known as Bmal1), encoding aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator-like protein 1 — renders the heart insensitive to time-o f-day fluctuations in BCAA responsiveness37. Moreover, although chronic feeding of a BCAA-rich diet at the end of the awake period does not result in cardiac dysfunction per se, it exacerbates HF following TAC compared with mice fed a BCAA-rich diet at the beginning of the awake period37. How cardiac injury disrupts intrinsic circadian metabolism is an area of active investigation.

The transcription factor Krüppel-like factor 15 (KLF15) is a central regulator of circadian BCAA metabolism in the heart38. Mice lacking cardiac KLF15 have altered cardiac conduction and are susceptible to arrhythmias39. Moreover, HF induced by pressure overload in mice reduces Klf15 expression, with coordinated downregulation of gene expression of multiple BCAA metabolic enzymes and a corresponding increase in intramyocardial BCKA concentrations9. Similar decreases in cardiac KLF15 expression have also been observed in human cardiomyopathy40,41. Overexpression of Klf15 in cultured cardiomyocytes induces the expression of BCAA metabolic enzymes9. Therefore, given that KLF15 is a translational regulator of BCAA catabolism, the downregulation of KLF15 is a potential upstream event in cardiac injury that results in the accumulation of cardiac BCAAs and BCKAs.

Other studies have suggested that the accumulation of BCAAs and BCKAs, from either the downregulation of cardiac BCAA metabolism or the increased delivery of BCAAs and BCKAs from the plasma, might lead to mitochondrial dysfunction and affect redox homeostasis. Mitochondria isolated from normal mouse cardiomyocytes and treated with BCKAs have dose-dependent inhibition of complex I-mediated respiration and an increase in superoxide production9. Mitochondria isolated from cardiomyocytes from Ppm1k−/− mice also show an increase in superoxide production, together with evidence of increased oxidative modification (carbonylation) of proteins from Ppm1k−/− cardiac tissue lysates9. Knockdown of Ppm1k in cultured cardiomyocytes leads to the induction of cell death associated with loss of mitochondrial membrane potential and possible opening of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore42.

Changes in cardiac fuel selection are a hallmark of most cardiac diseases43. BCAAs can be oxidized to the level of the TCA cycle to function as anaplerotic substrates for ATP production. Therefore, the decrease in BCAA metabolism seen in HF could result in an energetic deficit and contribute to pathogenesis and disease progression. However, metabolic tracing studies using both 14C-labelled and 13C-labelled BCAAs and BCKAs consistently show that the absolute amount of BCAA oxidation in the heart is quite low, with minimal contribution to ATP production when compared with fatty acids and glucose17–19. This finding has been validated in a study of humans with HF, in which changes in metabolites were compared across the myocardium in failing hearts44. Moreover, cardiac BCAA oxidation is only slightly augmented by BT2 treatment, despite clear increases in BCKDH activity17–19. These findings of minimal cardiac BCAA oxidation could be related to the low level of expression of the newly described mitochondrial BCAA carrier, SLC25a44, in the heart17.

Decreased cardiac BCAA metabolism is unlikely to contribute to an energy deficit per se; however, several studies hint at an interplay between BCAA metabolism and the metabolism of other fuel substrates. Dietary restriction of BCAAs in Zucker obese rats normalized circulating BCAAs to levels seen in lean control rats45,46. Isolated heart perfusion studies with 13C stable isotope tracing showed that dietary BCAA restriction decreases glucose oxidation and increases cardiac fatty acid oxidation coupled with a decrease in intracardiac triglyceride stores46 (FIG. 2c). The mechanisms underlying this shift in fuel selection are not completely understood, but rats receiving the BCAA-restricted diet had decreased cardiac concentrations of hexokinase 2 and solute carrier family 2, facilitated glucose transporter member 4. Interestingly, dietary BCAA restriction had no effect on cardiac BCKDH activity or the abundance of downstream metabolites, suggesting that the observed metabolic changes are independent of flux through BCKDH46. In cultured cardiomyocytes, either overexpression of solute carrier family 2, facilitated glucose transporter member 1 (which increases glucose uptake) or provision of high-glucose media decreased expression of the transcription factor KLF15, which leads to coordinated downregulation of enzymes in the BCAA metabolic pathway and accumulation of intracellular BCAAs. This glucose–BCAA regulatory network is necessary for sustained mTOR activation and growth signalling in the setting of hypertrophic stimuli both in vitro and in vivo47. In cultured cardiomyocytes treated with phenylephrine, which stimulates hypertrophy, and in mice undergoing TAC, BT2 treatment alters the expression of genes involved in fuel utilization. Expression of the gene encoding pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH) kinase, isoenzyme 4 (Pdk4) is increased, which would be expected to decrease glucose oxidation via inhibitory phosphorylation of PDH. In addition, expression of the gene encoding the plasma membrane fatty acid transporter, platelet glycoprotein 4 (Cd36), as well as the genes encoding enzymes involved in fatty acid β-oxidation (acyl-coenzyme A oxidase 1, palmitoyl (Acox1); acyl-coenzyme A dehydrogenase, long-chain (Acadl); and acyl-coenzyme A dehydrogenase, medium-chain (Acadm)) were increased31.

In most studies, BCAAs and BCKAs are assumed to exert equivalent physiological effects; however, evidence suggests that these metabolites might influence distinct intracellular processes. For instance, studies in isolated pancreatic islets from mice lacking Bcat2, which catalyses the reversible transamination of BCAA to BCKA (FIG. 1), showed that conversion of α-ketoisocaproate (KIC) and glutamate to leucine and α-ketoglutarate is necessary for KIC-stimulated insulin secretion48. By contrast, Bcat2 is not needed for leucine to stimulate insulin secretion48. Mice lacking Bcat2 in the heart accumulate cardiac BCAAs, with a corresponding decrease in cardiac BCKAs and, interestingly, have improved insulin-stimulated glucose oxidation compared with wild-type mice49. Exposure of cardiac Bcat2-knockout hearts to increased concentrations of BCKAs suppressed insulin-stimulated glucose oxidation rates, suggesting that the accumulation of BCKAs, but not BCAAs, results in cardiac insulin resistance49. In the heart, reverse transamination of BCKA to BCAA can occur when mitochondrial BCAA transport is limited or when baseline activity of cardiac BCKDH is low17. Whether BCAT enzymes predominantly function in the forward or reverse direction not only helps to determine the fate of BCKAs, but also contributes to the cellular levels of other important metabolites, such as glutamate and α-ketoglutarate. A study of cells from patients with acute myeloid leukaemia showed that BCAT activity is crucial to facilitate α-ketoglutarate-mediated DNA methylation and leads to widespread changes in gene expression that drive leukaemic phenotypes50. Whether similar changes in DNA modification result from BCKA metabolism in the heart is an exciting area for future investigation.

The upstream events that trigger downregulation of cardiac BCAA metabolism in response to stress are unclear. However, two separate studies — one in mice using TAC and one using heart tissue from patients with dilated cardiomyopathy — have shown a decrease in the gene expression and protein abundance, respectively, of KLF15, which acts upstream of several BCAA catabolic enzymes, including PPM1K and BCAT2 (REFS.9,23). In addition, an increase in phosphorylation of mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 7 (MAP3K7; also known as transforming growth factor-β activating kinase 1) and of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (p38 MAPK) was observed in the human study23. Because transforming growth factor-β-mediated activation of p38 MAPK inhibits KLF15 expression51, MAP3K7 could be an early mediator of stress-induced changes in cardiac BCAA metabolism23.

Atherosclerosis and endothelial dysfunction.

Data supporting the role of BCAAs in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis are conflicting52 and depend on the animal models used, the presence or absence of other atherosclerotic and metabolic risk factors, and the specific BCAA studied. In support of an anti-atherogenic role for BCAAs, adding leucine to the drinking water of Apoe−/− mice decreases serum LDL-cholesterol levels through increasing hepatic cholesterol efflux to bile acids and results in a >50% reduction in aortic atherosclerotic plaque53. In both cell culture systems and in macrophages derived from Apoe−/− mice, leucine supplementation decreases macrophage lipid content and foam cell formation54.

In the setting of insulin resistance, elevated plasma leucine concentration is associated with impaired endothelium-dependent vascular relaxation in Zucker obese rats with T2DM, suggesting that increased BCAA levels might be linked to impaired nitric oxide (NO) metabolism55. This association is supported by data showing that infusion of leucine in the rat isolated kidney increases renal vascular resistance in a NO-dependent manner56. Conversely, in studies using isolated aortic rings from rats, inhibition of leucine catabolism leads to increased NO-independent contractility57. The mechanisms linking elevated leucine concentration with endothelial dysfunction are not fully delineated, but could involve activation of mTOR. Incubation of mouse aortic rings with leucine increases phosphorylation of 40S ribosomal protein S6, a marker of mTOR activation, and reduces endothelium-dependent relaxation evoked by acetylcholine58. Similarly, overexpression of ribosomal protein S6 kinase (S6K) in mouse aortic rings is sufficient to reproduce this phenotype, and overexpression of an S6K dominant-negative construct abrogates impairment of endothelial relaxation by leucine58. Mechanistically, the increase in leucine-d riven mTOR signalling induces a pro-oxidant gene programme, leading to increased generation of reactive oxygen species and subsequent vascular endothelial dysfunction58,59 (FIG. 2d).

The role of the valine metabolite 3-HIB is under-studied among the potential mechanisms connecting BCAA metabolism to atherosclerosis (FIG. 2d). In a study of how the transcriptional co-activator peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ coactivator 1α (PGC1α) coordinates angiogenesis and fuel delivery to skeletal muscle, 3-HIB was identified as a crucial regulator of transendothelial fatty acid uptake and transport14. Overexpression of skeletal muscle PGC1α led to excessive 3-HIB production and accumulation of lipid in the muscle, resulting in insulin resistance14. Although these findings provide insight into the association between BCAAs and insulin resistance, whether 3-HIB-mediated transendothelial flux of fatty acids affects the development of atherosclerosis is unknown.

Deposition of lipids and cholesterol in the vascular endothelium and the infiltration of inflammatory cells are early processes in atherosclerotic plaque formation. Following plaque rupture, activation of platelets and the coagulation cascade ultimately lead to intravascular thrombus with subsequent myocardial or cerebrovascular infarction. The effects of BCAAs on platelet activity have been investigated in mouse models and humans. In healthy human volunteers, acute ingestion of BCAAs increased platelet BCAA concentrations accompanied by collagen-induced platelet activation and aggregation60. Interestingly, whereas downregulation of BCAA catabolism tends to be associated with adverse cardiovascular outcomes, platelets from Ppm1k−/− mice in this study had reduced activation and were less prone to arterial thrombosis than platelets from wild-type mice. Instead, the abundance of downstream BCAA catabolic intermediates, especially α-ketoisovalerate (the BCKA of valine), was associated with increased platelet activation, possibly due to increased propionylation of key proteins involved in thrombosis60. These findings suggest that platelets are sensitive to BCAA exposure, consistent with a metabolic overflow model, in which decreased oxidation elsewhere results in a higher BCAA load in these cells and, subsequently, increased BCAA-dependent activation of thrombotic pathways.

Myocardial ischaemia and reperfusion.

BCAAs also have a role in the cardiac response to ischaemia and reperfusion (FIG. 2b). A study using Ppm1k−/− mice showed that accumulation of cardiac BCAAs downregulates the hexosamine biosynthetic pathway, thereby decreasing O-linked N-acetylglucosamine (O-GlcNAc) modification of PDH and inhibiting glucose oxidation. This BCAA-related inhibition of glucose oxidation worsens cardiac function after ischaemia and reperfusion61. Conversely, in mice with T2DM (induced by a high-fat diet and low-dose streptozotocin), activation of cardiac BCAA metabolism via PPM1K overexpression or BDK inhibition via BT2 administration ameliorated ischaemia–reperfusion injury by decreasing oxidative stress62.

Arrhythmias.

Sudden, lethal cardiac arrhythmias are the most common cause of sudden cardiac death63, but aside from genetic determinants, ischaemic heart disease and HF, the risk factors that predispose individuals to these events are poorly understood. Using an N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea mutagenesis screen, a variant in the Bcat2 gene was identified that predisposes mice to sudden cardiac arrhythmias13. These mice experience sudden death at a young age, associated with an increase in plasma BCAA levels, without any overt cardiac dysfunction. Cardiomyocytes isolated from these mice have impaired electrophysiological properties, including prolonged QTc and PR intervals, and evidence of inducible pro-arrhythmic characteristics. Similar electrophysiological properties were seen in human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes incubated in the same concentrations of BCAA as observed in the mouse model. These findings were reversed when the cardiomyocytes were treated with rapamycin, indicating that the pro-arrhythmic effects of BCAAs are mTOR-dependent 13.

Ageing.

Ageing and CVD are intricately linked. Ageing is a major risk factor for the development of CVD, whereas freedom from CVD is a major determinant of longevity and healthspan. Therefore, the interplay between BCAA metabolism and lifespan has implications for the future development of CVD.

Dietary and caloric restriction have long been reported to prolong lifespan across numerous species, and similar results are observed with the inhibition of nutrient-sensing pathways such as mTOR, insulin-like growth factor 1 and AMP/ATP-binding subunit of AMP-activated protein kinase64. Many of these beneficial effects have been attributed to protein restriction, and several studies have uncovered how dietary BCAA restriction, in particular, might influence longevity and healthspan. However, it should be noted that associations between BCAA intake and ageing or age-related disorders remain controversial, and the underlying mechanisms are complex65 and beyond the scope of this Review.

Observationally, calorie restriction in mice is associated with a decrease in circulating BCAA concentrations that inversely correlate with lifespan66. Mice fed a long-term diet of excess BCAAs had hyperphagia, obesity and decreased lifespan compared with mice fed an isocaloric and macronutrient content-controlled diet with normal BCAA concentrations66. Interestingly, this effect was not the result of increased BCAA-mediated signalling through mTOR, which might have been predicted, but instead was related to appetite control through the imbalance of BCAAs and other essential amino acids. Rebalancing the BCAA–essential amino acid ratio in BCAA-excess mice eliminated hyperphagia and promoted longevity67. Dietary BCAA restriction in genetic mouse models of accelerated ageing extends lifespan, reduces frailty and improves metabolic health, with certain sex-specific effects on these outcomes, depending on the age at which the BCAA-restricted diet is started68. Despite improvements in age-r elated phenotypes, dietary BCAA restriction does not delay the cardiomyopathy that is characteristic in these genetic models68, highlighting the complex interplay between dietary BCAA intake, systemic BCAA metabolism and cardiac function.

Epidemiology of BCAAs in CVD

Metabolomic studies reporting on the association between BCAAs and CVD have been conducted in numerous epidemiological cohorts (TABLE 1). In the sections that follow, we describe the findings of these studies across a broad range of CVD states.

Table 1 |.

Human epidemiological studies showing associations between BCAAs and CVD

| End point | Population | Findings | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| HF | |||

| Prevalent HFrEF | Single-centre registry of individuals presenting for coronary angiography (HFrEF, n = 279; HFpEF, n = 282; no HF, n = 191) | Plasma BCAA levels higher in HFrEF than in HFpEF and no HF controls | 7 |

| Death | Single-centre registry of individuals with HFrEF (n = 1,032) | Plasma leucine and valine were part of a prognostic metabolite profile that predicts survival on top of established clinical models and biomarkers | 8 |

| MACE (death and HF hospitalization) | Single-centre registry of individuals presenting with STEMI (n = 138) | Higher plasma BCAA levels predicted MACE independently and better than NT-proBNP level | 69 |

| Peak VO2 | HF-ACTION clinical trial (n = 453) | Metabolite factor containing BCAAs, phenylalanine, tyrosine, methionine and ornithine associated with increased peak VO2 | 70 |

| Incident HF hospitalization | Individuals from the Hong Kong Diabetes Register with T2DM and no HFrEF (n = 2,139) | Increased plasma BCAA levels associated with increased risk of incident HFrEF | 71 |

| Response to CRT | Single-centre, prospective study of individuals with HFrEF receiving CRT (n = 24) and controls without HFrEF (n = 10) | Higher plasma BCAA levels predicted response (improvement in ejection fraction) to CRT | 72 |

| Incident left ventricular diastolic dysfunction | Prospective, family-based population study of individuals without HF (n = 570) | Higher plasma leucine and valine levels associated with maintenance of diastolic left ventricular function | 73 |

| 90-day change in 6MWD and NT-proBNP level | FIGHT clinical trial (n = 254) | Higher plasma BCAA levels predicted improvements in 6MWD and NT-proBNP level | 87 |

| CAD | |||

| Prevalent CAD | Single-centre registry of individuals with (n = 214) or without (n = 214) CAD presenting for coronary angiography | Plasma BCAA levels associated with presence of CAD | 10 |

| CAD severity | Single-centre registry of individuals presenting for coronary angiography (n = 1,873) | Plasma BCAA levels associated with severity of CAD | 11 |

| Incident death and MI | Single-centre registry of individuals presenting for coronary angiography (n = 2,023) | Plasma BCAA levels predicted death | 74 |

| Incident HF hospitalization or death from cardiovascular causes | Single-centre registry of individuals presenting with STEMI who did (n = 96) or did not (n = 96) undergo HF hospitalization or die from cardiovascular causes | Higher plasma BCAA levels associated with increased risk of HF hospitalization or death from cardiovascular causes | 75 |

| Incident stroke, MI or death from cardiovascular causes | PREDIMED clinical trial of individuals without CVD who did (n = 226) or did not (n = 744) experience stroke or MI, or die from cardiovascular causes | Higher plasma BCAA levels associated with increased risk of stroke, MI and death from cardiovascular causes | 76 |

| Incident stroke, MI or death from cardiovascular causes; carotid IMT; inducible ischaemia on cardiac stress testing | Population-based cohort study of individuals without baseline CVD who did (n = 253) or did not (n = 253) develop incident CVD | Higher plasma BCAA levels associated with increased risk of stroke, MI and death from cardiovascular causes, as well as carotid IMT and ischaemia on cardiac stress testing | 77 |

| Incident stroke, MI or coronary revascularization | Individuals from the prospective Women's Health Study without CVD (n = 27,041) | Higher plasma BCAA levels associated with increased risk of MI and coronary revascularization | 78 |

| Prevalent coronary artery calcium (subclinical atherosclerosis) | Individuals from the population-based Diabetes Heart Study (n = 700) | Higher plasma BCAA levels associated with coronary artery calcium only in European Americans | 79 |

| Incident MI or death from cardiovascular causes | African American individuals free from CVD in a population-based cohort study (Jackson Heart Study) (n = 2,346) | Higher plasma leucine level associated with decreased risk of incident MI or death from cardiovascular causes | 80 |

| MACE (stroke, MI, HF and revascularization) or death | Older men from the community-dwelling Australian CHAMP cohort (n = 918) | Lower BCAA levels associated with increased risk of frailty, MACE and death | 86 |

| Hypertension | |||

| Incident hypertension | Individuals without hypertension from the prospective, population-based PREVEND study (n = 4,169) | Higher plasma BCAA levels associated with increased incidence of hypertension | 12 |

| Prevalent hypertension | Population-based cohort study in Japan (n = 8,589) | Higher plasma BCAA levels associated with prevalent hypertension | 81 |

| Incident hypertension | Individuals without hypertension from a prospective, population-based cohort study in Iran (n = 4,288) | Increased dietary intake of BCAAs associated with increased incidence of hypertension | 83 |

| Prevalent hypertension, pulse wave velocity | Female twins from the TwinsUK registry (n = 1,898) | Increased dietary intake of leucine associated with decreased pulse wave velocity and lower central systolic blood pressure | 84 |

| Other CVD | |||

| Acute stroke | Single-centre, prospective study of individuals with acute stroke (n = 84) | Plasma BCAA levels decreased in acute stroke, and lower plasma BCAA levels associated with poor neurological outcomes | 85 |

| Arrhythmia | Individuals from the population-based German KORA study (n = 2,304) | Higher plasma BCAA levels associated with altered cardiac conduction and repolarization | 13 |

6MWD, 6-min walk distance; BCAA, branched-chain amino acid; CAD, coronary artery disease; CRT, cardiac resynchronization therapy; CVD, cardiovascular disease; HF, heart failure; HFpEF, heart failure with preserved ejection fraction; HFrEF, heart failure with reduced ejection fraction; IMT, intima-media thickness; MACE, major adverse cardiovascular events; MI, myocardial infarction; NT-proBNP, amino-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide; STEMI, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus; VO2, oxygen consumption.

Heart failure.

As we have discussed, elevations in plasma BCAA levels are associated with impaired cardiac function. In a cross-sectional study of individuals with HF with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF), HFrEF or no HF, plasma levels of BCAAs were significantly higher in those with HFrEF than in those who had HFpEF or no HF7. Importantly, beyond simply being associated with the presence of HF, plasma BCAA levels are predictive of clinical outcomes. In a single-centre study in >1,000 individuals with HFrEF, leucine, valine and BCAA-derived acylcarnitines were identified as components of a plasma metabolite profile that incrementally predicted survival, independent of established HFrEF risk prediction tools and biomarkers8. Moreover, in 138 individuals with ST-segment elevation MI and acute HF, baseline BCAA level outperformed amino-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP; an established risk biomarker) level in predicting adverse cardiovascular events over a 3-year follow-up period69. Plasma BCAA levels were also associated with maximal oxygen consumption in individuals with HFrEF in the HF-A CTION clinical trial70. These studies all showed associations between BCAAs and HF, independent of T2DM. However, an investigation using the Hong Kong Diabetes Register found that baseline plasma BCAA levels in a cohort of ~2,100 individuals with T2DM predicted incident HF after adjustment for other established HF risk factors. This finding suggests that elevated plasma BCAA levels could act as metabolic mediators of HF pathogenesis in the setting of T2DM71.

Interestingly, in a study of 24 individuals with HFrEF undergoing cardiac resynchronization therapy, increased plasma BCAA levels at baseline were associated with improvement in left ventricular systolic function72. Moreover, in individuals without structural heart disease who were followed up over time with serial echocardiography, increased baseline plasma BCAA levels were associated with a decreased risk of developing left ventricular diastolic dysfunction, which is a marker of future adverse cardiovascular events73. These findings, which seem to contradict the results of other studies discussed above, suggest that in certain populations and conditions, increased plasma BCAA concentrations might be beneficial.

Coronary artery disease.

Plasma BCAA levels have also emerged as a biomarker of several other CVDs. A BCAA-related signature is not only associated with the presence of coronary artery disease (CAD) but also with CAD severity in individuals undergoing coronary angiography. Of note, this association is independent of BMI, T2DM status and glycated albumin level (a marker of insulin resistance)10,11. Additionally, the plasma BCAA signature independently predicted MI and adverse cardiovascular events in this cohort10,74. In patients with ST-segment elevation MI requiring percutaneous coronary intervention, baseline plasma BCAA levels were associated with an increased risk of death from cardiovascular causes and the development of acute HF75.

In the primary prevention PREDIMED study76, baseline plasma leucine and isoleucine concentrations were independently associated with an increased risk of incident MI and death from cardiovascular causes. Similarly, in a European cohort of individuals with no CVD, plasma concentrations of isoleucine and the aromatic amino acids tyrosine and phenylalanine independently predicted the development of atherosclerosis as measured by carotid intima–media thickness, as well as inducible myocardial ischaemia seen on exercise stress testing77. Therefore, plasma BCAA level can predict future atherosclerotic disease in those with a wide range of baseline cardiovascular risks.

In >27,000 women enrolled in the Women’s Health Study78, elevated baseline BCAA levels were associated with incident CVD over almost 19 years of follow-up, with predictive power similar to that of baseline LDL-cholesterol levels. Interestingly, the association between BCAAs and CVD was stronger in women who developed T2DM before developing CVD than in those without T2DM78, again implicating BCAAs in the pathogenesis of CVD in patients with T2DM.

The association between BCAAs and CAD might depend on race. In an analysis from the Diabetes Heart Study79, in which untargeted metabolomics was performed in a racially diverse cohort, BCAA levels were associated with coronary artery calcium (an indicator of subclinical atherosclerosis) in European Americans after adjusting for age, sex, BMI, diabetes duration, LDL-cholesterol level and statin use. By contrast, this association was not seen in African Americans79. Moreover, elevated leucine levels were associated with a decreased risk of incident CAD in a metabolomics analysis from the Jackson Heart Study80, in which the study population is composed of African American individuals.

Hypertension, stroke and arrhythmia.

Compared with HF and CAD, few studies have been conducted on the metabolic phenotypes of hypertension, stroke and arrhythmias in humans. Nonetheless, evidence is beginning to emerge that supports an association between BCAAs and these conditions. In a study in >4,100 participants of the PREVEND study12, baseline BCAA concentration predicted incident hypertension over ~9 years of follow-up, independent of hypertension risk factors (including age, sex, history of T2DM, tobacco and alcohol consumption, BMI, systolic blood pressure, estimated glomerular filtration rate, urinary albumin excretion, and levels of glucose, total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, triglycerides and insulin). Similar associations have been observed in cross-sectional analyses of two separate cohorts of Asian individuals (8,589 Japanese81 and 472 Chinese82 individuals), in which plasma BCAA levels positively correlated with blood pressure. Consistent with these findings, in a study examining dietary protein intake in 6,493 Iranian individuals without hypertension, a dietary amino acid pattern rich in BCAAs was associated with an increased risk of hypertension over 3 years of follow-up83. Of note, however, plasma BCAA levels were not measured in this study. By contrast, in a study in 1,898 female twins from the TwinsUK registry, increased dietary intake of BCAAs was associated with a reduced risk of arterial stiffness and incident hypertension84. However, plasma BCAA concentrations were not correlated with dietary BCAA intake in this study, indicating that both tissue-level perturbations in BCAA metabolism and dietary intake of BCAA are necessary to affect plasma BCAA concentrations.

Among the CVD outcomes investigated in the primary prevention PREDIMED study76, incident stroke was most strongly associated with increased baseline BCAA concentrations. By contrast, in another study, plasma BCAA levels were decreased in patients with acute ischaemic stroke compared with control individuals, and a lower BCAA concentration predicted poor neurological outcomes85. These disparate findings are likely to be due to the disease state — prediction of stroke versus response to acute stroke, respectively — but also reflect the dynamic changes that can occur in systemic BCAA metabolism depending on the pathophysiological condition.

Epidemiological data linking BCAA and cardiac arrhythmias are limited; however, plasma valine and leucine levels were shown to be correlated with several electrocardiographic parameters — such as PR interval, QRS duration and QTc interval — in 2,304 individuals enrolled in the German, community-based KORA F4 study13. These findings suggest that cardiac exposure to increased BCAA concentrations can affect cardiac conduction and repolarization13.

Ageing.

In humans, ageing is characterized by increased skeletal muscle metabolism, decreased protein intake and subsequent decreased muscle mass, all of which contribute to frailty65. As a result, decreased plasma BCAA concentrations are often seen in older individuals86. Therefore, in aged populations, increased plasma BCAA levels might reflect better systemic and cardiometabolic health. For example, in the CHAMP study86 of ~900 older men in Australia (mean age 81 years), individuals with low concentrations of BCAA were more likely to be categorized as frail and had an increased risk of death and major adverse cardiac events (stroke, MI, HF and revascularization). Low plasma BCAA levels could also be a marker of severe systemic cardiac disease and, therefore, an indicator of poor prognosis. For instance, in a biomarker substudy from the FIGHT trial87, increased plasma BCAA concentrations predicted 90-day improvements in 6-min walking distance and NT-proBNP level, both of which are important clinical outcomes in HF. Individuals in this trial had advanced HFrEF and had been hospitalized in the previous 14 days. As HF progresses, an imbalance between catabolic and anabolic activity develops, leading to sarcopenia43. As seen with ageing, plasma BCAA level was positively correlated with skeletal muscle mass in individuals with HFrEF88. Therefore, higher plasma BCAA levels in individuals with advanced HFrEF could reflect better systemic health (that is, less sarcopenia) and predict better functional outcomes.

Therapeutic targets

Dietary and pharmacological manipulation of BCAA metabolism offers an exciting prospect for future CVD therapeutics. In maple syrup urine disease, the mainstay of therapy is dietary restriction of BCAAs89. Although dietary restriction of BCAAs has not been investigated in patients with CVD, in the setting of obesity this strategy leads to improvements in markers of metabolic health after ~40 days90. Additionally, sodium phenylbutyrate, a drug used to treat urea cycle disorders, has also been reported to reduce circulating BCAA and BCKA levels91. This finding was subsequently replicated in patients with late-onset, intermediate maple syrup urine disease and in healthy control individuals92. Sodium phenylbutyrate activates BCKDH by binding to and inhibiting BDK in a similar manner to BT2 (REF.92). Because BDK inhibition with BT2 has been shown to improve outcomes in animal models of CVD, the repurposing of sodium phenylbutyrate to treat patients with CVD should be considered in future clinical trials.

Conclusions

The link between BCAAs and a variety of CVD states is well-established. In humans and animals with HF, the BCAA metabolic pathway is consistently downregulated in cardiac tissue, leading to an accumulation of BCAAs and BCKAs, which contributes to HF pathogenesis through a variety of potential mechanisms. Epidemiologically, increased plasma BCAA concentrations are biomarkers for HF, CAD and hypertension and can predict adverse outcomes in individuals with CAD and HF, and predict stroke, MI, coronary revascularization and death from cardiovascular causes in individuals without CVD. The mechanisms underlying dysregulated BCAA metabolism and other CVDs, such as atherosclerosis, hypertension and cardiac arrhythmias, are less well-defined and are active areas of investigation. Several unanswered questions on the role of BCAA metabolism in CVD are areas for future research:

Does impaired BCAA metabolism influence vascular tone and endothelial function, and are the effects mediated by endothelium-dependent or endothelium-independent relaxation?

Do impairments in intrinsic BCAA metabolism in vascular smooth muscle cells contribute to hypertension?

Does BCAA metabolism affect atherosclerotic plaque progression and, if so, through which vascular compartment?

What is the role of BCAA metabolism in monocyte and macrophage recruitment to atherosclerotic plaque and transition to foam cells?

Does impaired BCAA metabolism lead to a pro-atherogenic inflammatory state?

Does endothelial cell BCAA metabolism contribute to the expression of cell adhesion molecules?

The answers to many of these questions call for the generation of cell-specific and tissue-specific animal models to precisely manipulate BCAA metabolism in relevant vascular compartments. Single-cell omics studies in models of vascular disease could also provide insights into the contribution of impaired BCAA metabolism among the cell populations involved in vascular pathology.

Key points.

branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs) — isoleucine, leucine and valine — are essential amino acids that have a crucial role in metabolic homeostasis through nutrient signalling.

High circulating concentrations of BCAAs are a hallmark of metabolic disorders, including obesity, insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes mellitus.

mechanisms underlying the association between BCAAs and cardiovascular disease (CvD) are still being defined, but include activation of the serine/threonine protein kinase mTor, mitochondrial dysfunction, shifts in cardiac substrate utilization and platelet activation.

epidemiological studies have also shown that high plasma BCAA concentrations identify individuals with heart failure, coronary artery disease or hypertension and predict adverse events in these populations.

In some other populations (such as african american individuals without CvD and frail elderly individuals), high plasma BCAA concentrations predict improved cardiovascular outcomes.

areas for future research include the roles of tissue-specific BCAA metabolism and inter-organ BCAA metabolic crosstalk in various CvD states and the roles of impaired BCAA metabolism in vascular function and atherosclerosis.

Acknowledgements

The authors are supported by NIH grants K08HL135275 (R.W.M.) and R01HL160689 (R.W.M.), American Diabetes Association Pathway to Stop Diabetes Award 1-16-INI-17 (P.J.W.), the Edna and Fred L. Mandel Jr. Foundation (R.W.M.) and the Duke School of Medicine Strong Start Award (R.W.M.).

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review information

Nature Reviews Cardiology thanks Gary Lopaschuk, Yibin Wang and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

References

- 1.Ridaura VK et al. Gut microbiota from twins discordant for obesity modulate metabolism in mice. Science 341, 1241214 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pedersen HK et al. Human gut microbes impact host serum metabolome and insulin sensitivity. Nature 535, 376–381 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wolfson RL et al. Sestrin2 is a leucine sensor for the mTORC1 pathway. Science 351, 43–48 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Felig P, Marliss E & Cahill GF Plasma amino acid levels and insulin secretion in obesity. N. Engl. J. Med. 281, 811–816 (1969). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.White PJ & Newgard CB Branched-chain amino acids in disease. Science 363, 582–583 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.White PJ et al. Insulin action, type 2 diabetes, and branched-chain amino acids: a two-way street. Mol. Metab. 52, 101261 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hunter WG et al. Metabolomic profiling identifies novel circulating biomarkers of mitochondrial dysfunction differentially elevated in heart failure with preserved versus reduced ejection fraction: evidence for shared metabolic impairments in clinical heart failure. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 5, e003190 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lanfear DE et al. Targeted metabolomic profiling of plasma and survival in heart failure patients. JACC Heart Fail. 5, 823–832 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sun H et al. Catabolic defect of branched-chain amino acids promotes heart failure. Circulation 133, 2038–2049 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shah SH et al. Association of a peripheral blood metabolic profile with coronary artery disease and risk of subsequent cardiovascular events. Circ. Cardiovasc. Genet. 3, 207–214 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bhattacharya S et al. Validation of the association between a branched chain amino acid metabolite profile and extremes of coronary artery disease in patients referred for cardiac catheterization. Atherosclerosis 232, 191–196 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Flores-Guerrero JL et al. Concentration of branched-chain amino acids is a strong risk marker for incident hypertension. Hypertension 74, 1428–1435 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Portero V et al. Chronically elevated branched chain amino acid levels are pro-arrhythmic. Cardiovasc. Res. 118, 1742–1757 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jang C et al. A branched-chain amino acid metabolite drives vascular fatty acid transport and causes insulin resistance. Nat. Med. 22, 421–426 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Green CR et al. Branched-chain amino acid catabolism fuels adipocyte differentiation and lipogenesis. Nat. Chem. Biol. 12, 15–21 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yoneshiro T et al. BCAA catabolism in brown fat controls energy homeostasis through SLC25A44. Nature 572, 614–619 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Walejko JM et al. Branched-chain α-ketoacids are preferentially reaminated and activate protein synthesis in the heart. Nat. Commun. 12, 1680 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Neinast MD et al. Quantitative analysis of the whole-body metabolic fate of branched-chain amino acids. Cell Metab. 29, 417–429.e4 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fillmore N, Wagg CS, Zhang L, Fukushima A & Lopaschuk GD Cardiac branched-chain amino acid oxidation is reduced during insulin resistance in the heart. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 315, E1046–E1052 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nishi K et al. Branched-chain keto acid inhibits mitochondrial pyruvate carrier and suppresses gluconeogenesis. SSRN Electron. J. 10.2139/ssrn.4022706 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li R et al. Time series characteristics of serum branched-chain amino acids for early diagnosis of chronic heart failure. J. Proteome Res. 18, 2121–2128 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang W et al. Defective branched chain amino acid catabolism contributes to cardiac dysfunction and remodeling following myocardial infarction. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 311, H1160–H1169 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Uddin GM et al. Impaired branched chain amino acid oxidation contributes to cardiac insulin resistance in heart failure. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 18, 86 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sansbury BE et al. Metabolomic analysis of pressure-overloaded and infarcted mouse hearts. Circ. Heart Fail. 7, 634–642 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Spyropoulos F et al. Metabolomic and transcriptomic signatures of chemogenetic heart failure. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 322, H451–H465 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lai L et al. Energy metabolic reprogramming in the hypertrophied and early stage failing heart: a multisystems approach. Circ. Heart Fail. 7, 1022–1031 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kwon HK, Jeong H, Hwang D & Park ZY Comparative proteomic analysis of mouse models of pathological and physiological cardiac hypertrophy, with selection of biomarkers of pathological hypertrophy by integrative proteogenomics. Biochim. Biophys. acta Proteins Proteom. 1866, 1043–1054 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lu G et al. Protein phosphatase 2Cm is a critical regulator of branched-chain amino acid catabolism in mice and cultured cells. J. Clin. Invest. 119, 1678–1687 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tso S-C et al. Benzothiophene carboxylate derivatives as novel allosteric inhibitors of branched-chain α-ketoacid dehydrogenase kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 20583–20593 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.White PJ et al. The BCKDH kinase and phosphatase integrate BCAA and lipid metabolism via regulation of ATP-citrate lyase. Cell Metab. 27, 1281–1293.e7 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen M et al. Therapeutic effect of targeting branched-chain amino acid catabolic flux in pressure-overload induced heart failure. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 8, e011625 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sciarretta S, Forte M, Frati G & Sadoshima J New insights into the role of mTOR signaling in the cardiovascular system. Circ. Res. 122, 489–505 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bueno OF et al. The MEK1-ERK1/2 signaling pathway promotes compensated cardiac hypertrophy in transgenic mice. EMBO J. 19, 6341–6350 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang L et al. KLF15 establishes the landscape of diurnal expression in the heart. Cell Rep. 13, 2368–2375 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Crnko S, Du Pré BC, Sluijter JPG & Van Laake LW Circadian rhythms and the molecular clock in cardiovascular biology and disease. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 16, 437–447 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McGinnis GR et al. Genetic disruption of the cardiomyocyte circadian clock differentially influences insulin-mediated processes in the heart. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 110, 80–95 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Latimer MN et al. Branched chain amino acids selectively promote cardiac growth at the end of the awake period. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 157, 31–44 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fan L, Hsieh PN, Sweet DR & Jain MK Krüppel-like factor 15: regulator of BCAA metabolism and circadian protein rhythmicity. Pharmacol. Res. 130, 123–126 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jeyaraj D et al. Circadian rhythms govern cardiac repolarization and arrhythmogenesis. Nature 483, 96–99 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Haldar SM et al. Klf15 deficiency is a molecular link between heart failure and aortic aneurysm formation. Sci. Transl. Med. 2, 26ra26 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Prosdocimo DA et al. Kruppel-like factor 15 is a critical regulator of cardiac lipid metabolism. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 5914–5924 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lu G et al. A novel mitochondrial matrix serine/threonine protein phosphatase regulates the mitochondria permeability transition pore and is essential for cellular survival and development. Genes Dev. 21, 784–796 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Doehner W, Frenneaux M & Anker SD Metabolic impairment in heart failure: the myocardial and systemic perspective. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 64, 1388–1400 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Murashige D et al. Comprehensive quantification of fuel use by the failing and nonfailing human heart. Science 370, 364–368 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.White PJ et al. Branched-chain amino acid restriction in Zucker-fatty rats improves muscle insulin sensitivity by enhancing efficiency of fatty acid oxidation and acyl-glycine export. Mol. Metab. 5, 538–551 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McGarrah RW et al. Dietary branched-chain amino acid restriction alters fuel selection and reduces triglyceride stores in hearts of Zucker fatty rats. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 318, E216–E223 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shao D et al. Glucose promotes cell growth by suppressing branched-chain amino acid degradation. Nat. Commun. 9, 2935 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhou Y, Jetton TL, Goshorn S, Lynch CJ & She P Transamination is required for α-ketoisocaproate but not leucine to stimulate insulin secretion. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 33718–33726 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Uddin GM et al. Deletion of BCATm increases insulin-stimulated glucose oxidation in the heart. Metabolism 124, 154871 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Raffel S et al. BCAT1 restricts αKG levels in AML stem cells leading to IDHmut-like DNA hypermethylation. Nature 551, 384–388 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Leenders JJ et al. Regulation of cardiac gene expression by KLF15, a repressor of myocardin activity. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 27449–27456 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Grajeda-I glesias C, Rom O & Aviram M Branched-chain amino acids and atherosclerosis: friends or foes? Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 29, 166–169 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhao Y et al. Leucine supplementation via drinking water reduces atherosclerotic lesions in apoE null mice. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 37, 196–203 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rom O et al. Atherogenicity of amino acids in the lipid-laden macrophage model system in vitro and in atherosclerotic mice: a key role for triglyceride metabolism. J. Nutr. Biochem. 45, 24–38 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wu G et al. Dietary supplementation with watermelon pomace juice enhances arginine availability and ameliorates the metabolic syndrome in Zucker diabetic fatty rats. J. Nutr. 137, 2680–2685 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kakoki M et al. Amino acids as modulators of endothelium-derived nitric oxide. Am. J. Physiol. Ren. Physiol. 291, F297–F304 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schachter D & Sang JC Aortic leucine-to-glutamate pathway: metabolic route and regulation of contractile responses. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 282, H1135–H1148 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Reho JJ, Guo DF & Rahmouni K Mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1 signaling modulates vascular endothelial function through reactive oxygen species. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 8, e010662 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhenyukh O et al. Branched-chain amino acids promote endothelial dysfunction through increased reactive oxygen species generation and inflammation. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 22, 4948–4962 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Xu Y et al. Branched-chain amino acid catabolism promotes thrombosis risk by enhancing tropomodulin-3 propionylation in platelets. Circulation 142, 49–64 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Li T et al. Defective branched-chain amino acid catabolism disrupts glucose metabolism and sensitizes the heart to ischemia-reperfusion injury. Cell Metab. 25, 374–385 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lian K et al. PP2Cm overexpression alleviates MI/R injury mediated by a BCAA catabolism defect and oxidative stress in diabetic mice. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 866, 172796 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Adabag AS, Luepker RV, Roger VL & Gersh BJ Sudden cardiac death: epidemiology and risk factors. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 7, 216–225 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Fontana L, Partridge L & Longo VD Extending healthy life span–from yeast to humans. Science 328, 321–326 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Le Couteur DG et al. Branched chain amino acids, aging and age-related health. Ageing Res. Rev. 64, 101198 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Green CL et al. The effects of graded levels of calorie restriction: XIII. Global metabolomics screen reveals graded changes in circulating amino acids, vitamins, and bile acids in the plasma of C57BL/6 mice. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 74, 16–26 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Solon-Biet SM et al. Branched-chain amino acids impact health and lifespan indirectly via amino acid balance and appetite control. Nat. Metab. 1, 532–545 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Richardson NE et al. Lifelong restriction of dietary branched-chain amino acids has sex-specific benefits for frailty and lifespan in mice. Nat. Aging 1, 73–86 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Du X et al. Increased branched-chain amino acid levels are associated with long-term adverse cardiovascular events in patients with STEMI and acute heart failure. Life Sci. 209, 167–172 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ahmad T et al. Prognostic implications of long-chain acylcarnitines in heart failure and reversibility with mechanical circulatory support. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 67, 291–299 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lim LL et al. Circulating branched-chain amino acids and incident heart failure in type 2 diabetes: the Hong Kong diabetes register. Diabetes Metab. Res. Rev. 36, e3253 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Nemutlu E et al. Cardiac resynchronization therapy induces adaptive metabolic transitions in the metabolomic profile of heart failure. J. Card. Fail. 21, 460–469 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zhang ZY et al. Diastolic left ventricular function in relation to circulating metabolic biomarkers in a population study. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 26, 22–32 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Shah SH et al. Baseline metabolomic profiles predict cardiovascular events in patients at risk for coronary artery disease. Am. Heart J. 163, 844–850.e1 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Du X et al. Relationships between circulating branched chain amino acid concentrations and risk of adverse cardiovascular events in patients with STEMI treated with PCI. Sci. Rep. 8, 15809 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ruiz-Canela M et al. Plasma branched-chain amino acids and incident cardiovascular disease in the PREDIMED trial. Clin. Chem. 62, 582–592 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Magnusson M et al. A diabetes-predictive amino acid score and future cardiovascular disease. Eur. Heart J. 34, 1982–1989 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Tobias DK et al. Circulating branched-chain amino acids and incident cardiovascular disease in a prospective cohort of US women. Circ. Genom. Precis. Med. 11, e002157 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Chevli PA et al. Plasma metabolomic profiling in subclinical atherosclerosis: the Diabetes Heart Study. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 20, 231 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Cruz DE et al. Metabolomic analysis of coronary heart disease in an African American cohort from the Jackson Heart Study. JAMA Cardiol. 7, 184–194 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Yamaguchi N et al. Plasma free amino acid profiles evaluate risk of metabolic syndrome, diabetes, dyslipidemia, and hypertension in a large Asian population. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 22, 35 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Yang R et al. Association of branched-chain amino acids with carotid intima-media thickness and coronary artery disease risk factors. PLoS ONE 9, e99598 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Teymoori F, Asghari G, Mirmiran P & Azizi F Dietary amino acids and incidence of hypertension: a principle component analysis approach. Sci. Rep. 7, 16838 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Jennings A et al. Amino acid intakes are inversely associated with arterial stiffness and central blood pressure in women. J. Nutr. 145, 2130–2138 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kimberly WT, Wang Y, Pham L, Furie KL & Gerszten RE Metabolite profiling identifies a branched chain amino acid signature in acute cardioembolic stroke. Stroke 44, 1389–1395 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Le Couteur DG et al. Branched chain amino acids, cardiometabolic risk factors and outcomes in older men: the Concord Health and Ageing in Men Project. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 75, 1805–1810 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Lerman JB et al. Plasma metabolites associated with functional and clinical outcomes in heart failure with reduced ejection fraction with and without type 2 diabetes. Sci. Rep. 12, 9183 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Tsuji S et al. Nutritional status of outpatients with chronic stable heart failure based on serum amino acid concentration. J. Cardiol. 72, 458–465 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Blackburn PR et al. Maple syrup urine disease: mechanisms and management. Appl. Clin. Genet. 10, 57–66 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Fontana L et al. Decreased consumption of branched-chain amino acids improves metabolic health. Cell Rep. 16, 520–530 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Tuchman M et al. Cross-sectional multicenter study of patients with urea cycle disorders in the United States. Mol. Genet. Metab. 94, 397–402 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Brunetti-Pierri N et al. Phenylbutyrate therapy for maple syrup urine disease. Hum. Mol. Genet. 20, 631–640 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]