Abstract

Background & objectives:

Both innovator and generic imatinib are approved for the treatment of Chronic Myeloid Leukaemia-Chronic phase (CML-CP). Currently, there are no studies on the feasibility of treatment-free remission (TFR) with generic imatinib. This study attempted to determine the feasibility and efficacy of TFR in patients on generic Imatinib.

Methods:

In this single-centre prospective Generic Imatinib-Free Trial-in-CML-CP study, twenty six patients on generic imatinib for ≥3 yr and in sustained deep molecular response (BCR ABLIS ≤0.01% for more than two years) were included. After treatment discontinuation, patients were monitored with complete blood count and BCR ABLIS by real-time quantitative PCR monthly for one year and three monthly thereafter. Generic imatinib was restarted at single documented loss of major molecular response (BCR ABLIS>0.1%).

Results:

At a median follow up of 33 months (interquartile range 18.7-35), 42.3 per cent patients (n=11) continued to be in TFR. Estimated TFR at one year was 44 per cent. All patients restarted on generic imatinib regained major molecular response. On multivariate analysis, attainment of molecularly undetectable leukaemia (>MR5) prior to TFR was predictive of TFR [P=0.022, HR 0.284 (0.096-0.837)].

Interpretation & conclusions:

The study adds to the growing literature that generic imatinib is effective and can be safely discontinued in CML-CP patients who are in deep molecular remission.

Keywords: Chronic myeloid leukaemia, generic imatinib, treatment-free remission

With the availability of tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI), chronic myeloid leukaemia (CML) has become a manageable disease rather than being fatal1. The international randomized study of interferon vs. STI571 (IRIS) trial reported overall survival of 83.3 per cent at 10 yr with imatinib mesylate in patients with CML2,3. Generic imatinib for the treatment of CML has been available since 2002 in India, 2012 in Europe, 2015 in Canada and 2016 in the USA4-6. Efficacy of generic imatinib has remained controversial because of lack of large comparative studies with innovator molecule7-9. Despite that, generic imatinib is widely used because of its lower cost implication, and consequently improved adherence to TKI10,11.

Lifelong treatment with TKI has a significant impact on quality of life (QoL)12. Therefore, treatment-free remission (TFR) has emerged as an important goal in the management of CML. With the incorporation of TFR from clinical trials to real-world practise, a successful TFR is now being increasingly recognized as a state of operational cure. In the French Stop Imatinib 1 (STIM1) trial, nearly 40 per cent of patients continued to be in TFR at a median follow up of 77 months13. Similar data on achievement of TFR with generic imatinib are lacking. Therefore, in this prospective study, the feasibility of TFR with generic imatinib was evaluated.

Material & Methods

This single-centre prospective trial Generic Imatinib-Free Trial-in-CML-Chronic phase (CP) was conducted in the department of Clinical Hematology and Medical Oncology, Postgraduate Institute of Medical Eeducation & Research, Chandigarh, India, from January 2017 to December 2020. The study protocol was approved by the Institute Ethics Committee and written informed consent was obtained from all the participants. The trial was registered under clinical trial registry, India (CTRI/2018/08/015357). The diagnosis of CML was based on bone marrow examination and demonstration of the Philadelphia chromosome on karyotype or detection of BCR (breakpoint cluster region) ABL (abelson) transcript by reverse transcription-PCR. The molecular response was assessed by an Xpert BCR-ABL1 Monitor (Cepheid, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) using an automated cartridge system. Xpert BCR-ABL/ABL1 test results were converted to the International Scale using an assay specific conversion factor determined by comparison with an International Scale reference assay14. The PCR detection limit for this assay was BCR-ABL1 transcript level >0.001 per cent; this cut-off for molecular response, i.e. MR5 was used to define molecularly undetectable leukaemia. Deep molecular response (DMR) was defined as BCR-ABL1IS ≤0.01 per cent (MR4) and major molecular response (MMR) was defined as BCR-ABL1IS≤0.1 per cent (MR3). CML-CP patients aged more than 18 yr on generic imatinib (Veenat, beta crystalline form, Natco pharmaceuticals, Hyderabad, India) for more than three years and with sustained DMR for more than two years were eligible for the study. All patients were evaluated for eligibility in the study and those eligible were enrolled after obtaining informed consent. All patients with intermediate/high Sokal score at baseline were explained the possibility of higher risk of molecular relapse at the time of enrolment.

After treatment discontinuation, patients were followed up with complete blood count and RQ-PCR for BCR-ABLIS monthly for the first one year and every three months thereafter. Loss of MMR at any single-time point was the criteria for TFR failure and an indication to restart imatinib.

Statistical analysis: To identify prognostic factors, all variables associated with the outcome at 0·2 level on univariate analysis were simultaneously entered into a Cox regression model; significance was set at P=0.05. Estimates for hazard ratios and corresponding 95 per cent confidence intervals were obtained for significant outcome factors. Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS statistical software version 20.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results & Discussion

During the study period from January 2017 to November 2019, 110 patients of CML-CP who were on Imatinib and were in DMR were screened. Of these, 39 patients were on generic Imatinib for greater than three years and were in DMR for more than two years were evaluated. Of the 39 patients, 13 were excluded (no consent: 8, loss to follow up: 2, loss of DMR when RQ PCR BCR-ABL1IS was repeated just prior to the treatment cessation: 2). A total of 26 patients who met the inclusion criteria were included in the study. The median age of the study population was 57 yr (range, 32-73 yr) and the male:female ratio was 1.2:1. Baseline Sokal score was low in 16 (61.5%), intermediate in eight (30.7%) and high in two (7.7%). Most patients were on long-term imatinib, the median duration of treatment with generic imatinib was 6.9 yr (range, 3.1-15). At the time of treatment discontinuation, 18 (69.2%) patients had MR5 and remaining eight (30.8%) had MR4. Prior to imatinib discontinuation, the median duration of DMR was 4.2 yr (range, 2.1-10 yr; Table).

Table.

Baseline characteristics of study population

| Characteristic | Data |

|---|---|

| Age (yr), median (range) | 57 (32-73) |

| Gender, n (%) | |

| Male | 14 (54) |

| Female | 12 (46) |

| Sokal, n (%) | |

| Low | 16 (61.5) |

| Intermediate | 8 (30.8) |

| High | 2 (7.7) |

| Duration of imatinib prior to discontinuation (yr), median (range) | 6.9 (3.1-15) |

| Depth of remission, n(%) | |

| > MR5 | 18 (69.2) |

| ≤ MR5 | 8 (30.8) |

| Duration of deep molecular remission (yr), median (range) | 4.25 (2.1-10) |

MR, molecular response

After a median follow up of 33 months (Interquartile range 18.7-35), 11 of the 26 patients (42.3%) continued to be in TFR, while 15 (57.7%) had loss of MMR. Among the patients who lost MMR, eight were in MR5, while the remaining seven were in MR4 at the time of TKI discontinuation. The median duration of treatment prior to treatment discontinuation was six years (range, 3.1-8.5) and was not statistically different from those who sustained TFR (P<0.09). The median time to loss of MMR was three months (range, 2-21 months). Twelve of the 15 patients (80%) had loss of MMR within six months of treatment discontinuation, whereas the other three had loss of MMR at nine, 12 and 21 months, respectively. The estimated probability of remaining in TFR was 61 per cent at three months (Kaplan–Meier analysis), 53 per cent at six months and 44 per cent at 12 months. None of the patients had experienced loss of complete hematologic response (CHR) and/or progression to accelerate/blast phase.

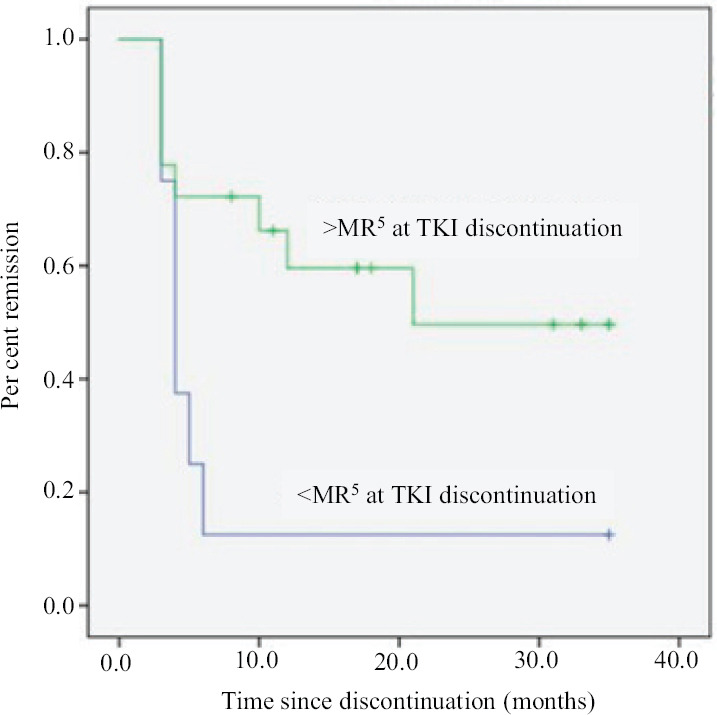

Age, gender, baseline Sokal score, time to MMR, depth of molecular remission, duration of imatinib and duration of DMR were analyzed as potentially predictive factors for TFR durability. On univariate analysis, only depth of molecular response (CMR vs. not in CMR) at the time of treatment discontinuation was found to be predictive of TFR durability (P=0.020; Figure). On multivariate analysis using cox regression, only depth of molecular response remained significant (P=0.022) with HR 0.284 (0.096-0.837).

Figure.

Kaplan-Meier plot of major molecular remission free survival by depth of molecular response at treatment discontinuation (>MR5 vs. ≤MR5). TKI, tyrosine kinase inhibitor.

Three of the 26 patients (11.5%) developed TKI withdrawal syndrome after stopping imatinib. Two patients had fatigue and non-specific body aches after one month of imatinib discontinuation. One female developed bilateral lower limb pain with left suprapatellar bursitis after seven months of treatment discontinuation. She responded to anti-inflammatory agents and continues to be in TFR at 33 months follow up. All 15 patients with loss of MMR were restarted on treatment with generic imatinib and attained MMR after a median duration of one month (range, 1-4 months). At a median follow up of 33 months (range, 19-35), all 15 of these patients continued to be in MMR.

Generic imatinib has provided a cost-effective alternative TKI option to large number of patients with CML.TFR with generic versions of imatinib has not been studied till date. Wide range of generic versions of imatinib (alpha, beta or gamma crystalline forms of imatinib mesylate) is available across different countries15-18. There are growing number of studies with different generic forms of imatinib with contradicting findings. While majority of studies have shown that generic and innovator imatinib are equally efficacious15, a few have suggested loss of responses when switched from innovator to generic version of imatinib8. Besides, certain studies have also suggested that medication persistence may be lower with generic imatinib, mainly driven by excessive adverse events as compared to innovator19. Persistence on a given TKI for more than three years and attainment of DMR - both are pre-requisites for TFR trial; therefore, a TFR study on generic imatinib potentially addressees both tolerability and efficacy controversies that surround generic imatinib use. One year TFR rate of 44 per cent with generic imatinib in the current study is similar to the previous studies with innovator imatinib13,20. None of our patients had disease progression, and all patients with TFR failure were able to re-attain MMR with generic imatinib. These findings again support the efficacy and feasibility of TFR with generic imatinib.

While the duration of TKI treatment and duration of deep molecular response are known prognostic factors for a durable TFR21, they were not found to be prognostic in the present study. This may be explained by the relatively small number of patients who received imatinib for less than four years or had sustained DMR for less than three years in our study group (4 and 6 patients, respectively). In our cohort, only depth of molecular response (CMR vs. not in CMR) at the time of treatment discontinuation was found to be predictive of TFR durability (P=0.020; Figure). However, the potential impact of factors on the durability of TFR could be impacted by small sample size and larger data sets are required to confirm the findings.

Cost-benefit analysis was not specifically done in the present investigation. Currently, the monthly cost of most brands of generic imatinib ranges from ₹ 1000-1400 (INR). Even if additional costs of frequent (three monthly) RQ-PCR BCR-ABL-IS testing (₹ 6000-8000/yr) is taken into consideration, TFR is likely to have a cost–benefit advantage in select patients who maintain their TFR in the long term. In addition to cost savings, TFR is also associated with significant improvements in QoL due to reversal of fatigue, diarrhoea, pigmentation and other toxicities associated with TKI use22. However, the effect on toxicities may not be unilateral. New or worsening musculoskeletal pains, pruritus or exacerbation of previous inflammatory conditions have been reported with stoppage of TKI use, and are termed as TKI withdrawal syndrome. The incidence of transient TKI withdrawal syndrome in the form of mild musculoskeletal symptoms was found to be 30 per cent in previous studies with innovator imatinib23. The Korean Imatinib Discontinuation Study (KIDS) study from Korea demonstrated that the occurrence of TKI withdrawal syndrome was associated with lower risk of molecular relapse24. In the present study, three patients (11.5%) developed TKI withdrawal, one of them continues to be in TFR at 19 months follow up.

As this study included patients taking a single-generic imatinib version, findings may not be generalizable to other generic versions of imatinib. Limited patient number, lack of comparator arm with innovator molecule and short duration of follow up are the other limitations of the study.

To conclude, the present study showed similar rates of TFR with generic imatinib. The findings of this study should instil confidence in the minds of CML patients and physicians regarding the safety as well as efficacy of generic imatinib in achieving TFR. Further research and larger studies are needed to confirm the study findings.

Data availability statement: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Footnotes

Financial support & sponsorship: The study procedures and investigations of RQ-PCR were funded by host Institute.

Conflicts of Interest: None.

References

- 1.Yanamandra U, Malhotra P. CML in India: Are we there yet? Indian J Hematol Blood Transfus. 2019;35:1–2. doi: 10.1007/s12288-019-01074-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hochhaus A, Larson RA, Guilhot F, Radich JP, Branford S, Hughes TP, et al. Long-term outcomes of imatinib treatment for chronic myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:917–27. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1609324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Deininger M, O'Brien SG, Guilhot F, Goldman JM, Hochhaus A, Hughes TP, et al. International randomized study of interferon vs. STI571 (IRIS) 8-year follow up: Sustained survival and low risk for progression or events in patients with newly diagnosed chronic myeloid leukemia in chronic phase (CML-CP) treated with imatinib. Blood. 2009;114:1126. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Experts in Chronic Myeloid Leukemia. The price of drugs for chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) is a reflection of the unsustainable prices of cancer drugs: From the perspective of a large group of CML experts. Blood. 2013;121:4439–42. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-03-490003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Conti RM, Padula WV, Larson RA. Changing the cost of care for chronic myeloid leukemia: The availability of generic imatinib in the USA and the EU. Ann Hematol. 2015;94(Suppl 2):S249–57. doi: 10.1007/s00277-015-2319-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen CT, Kesselheim AS. Journey of generic imatinib: A case study in oncology drug pricing. J Oncol Pract. 2017;13:352–5. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2016.019737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eskazan AE, Soysal T. The tolerability issue of generic imatinib in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia (Comment on Adi J Klil-Drori et al., Haematologica 2019;104(7): e293) Haematologica. 2019;104:e330. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2019.222000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saavedra D, Vizcarra F. Deleterious effects of non-branded versions of imatinib used for the treatment of patients with chronic myeloid leukemia in chronic phase: A case series on an escalating issue impacting patient safety. Leuk Lymphoma. 2014;55:2813–6. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2014.893302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alwan AF, Matti BF, Naji AS, Muhammed AH, Abdulsahib MA. Prospective single-center study of chronic myeloid leukemia in chronic phase: Switching from branded imatinib to a copy drug and back. Leuk Lymphoma. 2014;55:2830–4. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2014.904508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mathews V. Generic imatinib: The real-deal or just a deal? Leuk Lymphoma. 2014;55:2678–80. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2014.921299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Campbell D, Blazer M, Bloudek L, Brokars J, Makenbaeva D. Realized and projected cost-savings from the introduction of generic imatinib through formulary management in patients with chronic myelogenous leukemia. Am Health Drug Benefits. 2019;12:333–42. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yanamandra U, Malhotra P, Sahu KK, Sushma Y, Saini N, Chauhan P, et al. Variation in adherence measures to imatinib therapy. J Glob Oncol. 2018;4:1–10. doi: 10.1200/JGO.2016.007906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Etienne G, Guilhot J, Rea D, Rigal-Huguet F, Nicolini F, Charbonnier A, et al. Long-term follow-up of the french stop imatinib (STIM1) study in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:298–305. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.68.2914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.López-Jorge CE, Gómez-Casares MT, Jiménez-Velasco A, García-Bello MA, Barrios M, Lopez J, et al. Comparative study of BCR-ABL1 quantification: Xpert assay, a feasible solution to standardization concerns. Ann Hematol. 2012;91:1245–50. doi: 10.1007/s00277-012-1468-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ćojbašić I, Mačukanović-Golubović L, Vučić M, Ćojbašić Ž. Generic imatinib in chronic myeloid leukemia treatment: Long-term follow-up. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2019;19:e526–31. doi: 10.1016/j.clml.2019.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abou Dalle I, Kantarjian H, Burger J, Estrov Z, Ohanian M, Verstovsek S, et al. Efficacy and safety of generic imatinib after switching from original imatinib in patients treated for chronic myeloid leukemia in the United States. Cancer Med. 2019;8:6559–65. doi: 10.1002/cam4.2545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Danthala M, Gundeti S, Kuruva SP, Puligundla KC, Adusumilli P, Karnam AP, et al. Generic imatinib in chronic myeloid leukemia: Survival of the cheapest. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2017;17:457–62. doi: 10.1016/j.clml.2017.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.de Lemos ML, Kyritsis V. Clinical efficacy of generic imatinib. J Oncol Pharm Pract. 2015;21:76–9. doi: 10.1177/1078155214522143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Klil-Drori AJ, Yin H, Azoulay L, Harnois M, Gratton MO, Busque L, et al. Persistence with generic imatinib for chronic myeloid leukemia: A matched cohort study. Haematologica. 2019;104:e293–5. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2018.211235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saussele S, Richter J, Guilhot J, Gruber FX, Hjorth-Hansen H, Almeida A, et al. Discontinuation of tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy in chronic myeloid leukaemia (EURO-SKI): A prespecified interim analysis of a prospective, multicentre, non-randomised, trial. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19:747–57. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30192-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Saußele S, Richter J, Hochhaus A, Mahon FX. The concept of treatment-free remission in chronic myeloid leukemia. Leukemia. 2016;30:1638–47. doi: 10.1038/leu.2016.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Flynn KE, Weinfurt KP, Lin L, Radich JP, Schiffer CA, Mauro MJ, et al. Patient-reported outcome results from the U.S. life after stopping TKIs (LAST) study in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2019;134(Suppl 1):705. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hughes TP, Boquimpani C, Kim DW, Benyamini N, Clementino NC, Shuvaev V, et al. Treatment-free remission (TFR) in patients (pts) with chronic myeloid leukemia in chronic phase (CML-CP) treated with second-line nilotinib (NIL): First results from the ENESTop study. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(15 Suppl):7054. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee SE, Choi SY, Song HY, Kim SH, Choi MY, Park JS, et al. Imatinib withdrawal syndrome and longer duration of imatinib have a close association with a lower molecular relapse after treatment discontinuation: The KID study. Haematologica. 2016;101:717–23. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2015.139899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]