Abstract

Various aspects of online learning have been addressed in studies both pre- and during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, most pre-pandemic studies may have suffered from sampling selection issues, as students enrolled in online courses were often not comparable to those taking classes on campus. Similarly, most studies conducted during the initial stages of the pandemic might be confounded by the stress and anxiety associated with worldwide lockdowns and the abrupt switch to online education in most universities. Furthermore, existing studies have not comprehensively explored students' perspectives on online learning across different demographic groups, including gender, race-ethnicity, and domestic versus international student status. To address this research gap, our mixed-methods study examines these aspects using data from an anonymous survey conducted among a large and diverse sample of students at a mid-size university in the Northeastern United States. Our findings reveal important insights: (1) Females are nearly twice as likely as males to prefer online asynchronous classes and feel self-conscious about keeping their cameras on during online synchronous (e.g., Zoom) classes. However, gendered views and preferences align in other aspects of online learning. (2) Black students show a stronger preference for Zoom classes compared to online asynchronous classes and emphasize the importance of recording Zoom meetings. Hispanic students are twice as likely to prefer asynchronous online classes, which offer greater flexibility to manage multiple responsibilities. (3) International students value the ability to learn at their own pace provided by online learning but express dissatisfaction with the lack of peer interaction. On the other hand, domestic students are more concerned about reduced interaction with teachers in online education. Domestic students also exhibit a higher tendency to turn their cameras off during Zoom classes, citing reasons such as self-consciousness or privacy. These findings carry significant implications for future research and educational practice, highlighting the need for tailored approaches that consider diverse student perspectives.

Keywords: Distance education, Online learning, Post-secondary education, Pedagogy, Student demographics

1. Introduction

The COVID-19 virus outbreak forced many academic institutions to shift their education from in-person to remote in a matter of days (Dhawan, 2020). Many professors, lacking experience in online education, were left to determine a proper adjustment for their courses during this transition while students, lacking experience in taking online classes, were left to adjust (Gillis & Krull, 2020). As a result, most research on students’ views and experiences with online learning conducted at the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic likely confounds the stress and turmoil caused by the pandemic itself and by the abrupt transition to online learning with the effectiveness of online course delivery.

At the same time, studies of students’ experiences with online learning and its effectiveness conducted in pre-pandemic times suffer from the sample selectivity problem: most students had a choice about whether to enroll in online classes. We can reasonably expect that students who self-select into online courses are more advanced and disciplined and/or more burdened with multiple responsibilities restricting their options of attending classes on campus. This leaves researchers at a likely impasse for finding comparable samples of on-campus and online learners.

As the COVID-19 pandemic wanes and college education returns to normal, it offers researchers a unique opportunity to better understand students’ perceptions of online learning, since almost all college students have experienced both online and on-campus learning. Given this changing landscape of online learning in higher education, the current mixed methods study explores student perceptions of various types of online and in-person learning and how features such as camera use in live synchronous online classes inform student preferences. Our study includes a large, diverse sample of students (n = 690) from a mid-size university at the Northeast coast of the United States (approximately 6000 students total), which allows us to compare experiences of students from different demographic groups:

-

•

Males and females.

-

•

Black, White, and Hispanic students.

-

•

International and domestic students.

2. Literature review

2.1. The origins and types of online learning

Distance or remote learning is a form of education in which the teacher and student are separated geographically and often engage with the content at different times (Kentnor, 2015). The first major online learning experience in the United States happened in 1950 when the University of Houston, TX, began to provide collegiate courses over the nation's first university-licensed radio station, KUHF-FM (Fisher, 2012).

Two major forms of remote learning have since developed, known as asynchronous (async) and synchronous (sync) classes. Synchronous communication, the most akin to in-person learning, requires student and teacher to be logged in at the same time, to review the material. Asynchronous communication offers more flexibility, by allowing the participant to engage with the content at their convenience. The difference between sync and async learning is similar to a difference between a phone call and email conversation. Group discussions have shifted from conversations within the classroom to making comments in an online forum and responding to others without their physical presence. Cameras during sync classes have been introduced to help increase engagement, but some universities have stated that they do not require cameras to be on during classes for various reasons (Castelli & Sarvary, 2021; Kahn, El Kouatly Kambris, & Alfalahi, 2021).

Thus, the pedagogy for online learning is not a new emerging method of teaching and learning; rather, the eruption of the COVID-19 pandemic has worsened the situation and forced educational institutions to shift to online learning abruptly and entirely, to reduce the spread of the COVID-19 virus (Chung et al., 2020; Pokhrel & Chhetri, 2021). This shift has impacted students’ social interactions and performance, caused widespread stress and anxiety, so it is important to review prior studies within the pre-pandemic versus during-pandemic framework.

2.2. General perceptions of online learning before the COVID-19 pandemic

Long before the COVID-19 pandemic, empirical research has highlighted the preferences and issues students have with online learning (see Bygstad et al., 2022; Goldenson et al., 2021). One U.S. Department of Education meta-analysis found students in online learning outperformed students in traditional classrooms, and preferred online conditions (Means et al., 2009). Several studies found flexibility and agency were factors that drove students towards the online format: students felt they had greater control over their learning, experienced enough student interaction, and were able to gain new knowledge through online learning (Eastmond, 1998; Stone & Perumean-Chaney, 2011). Several studies have also found students’ appreciation of flexibility in online learning, particularly in asynchronous courses: the ability to choose their place of study, schedule and timing, and determine the pace of studies (Alexander et al., 2009; Nollenberger, 2015), easy use of online devices like laptops and smartphones (Stanciu & Gheorghe, 2017).

In addition to effectiveness, early research has found online learning environments to foster relationships and interpersonal skills: online networks offer interactions with people who have different social characteristics and opportunities to find shared interests (Wellman et al., 1996). However, subsequent studies are more likely to find a perceived lack of community as a common issue with online learning (Means et al., 2009; Nollenberger, 2015; Song et al., 2004). In addition, the Department of Education's meta-analysis noted that research results did not find online learning to be a superior method, even though it has some advantages over in-person learning (Means et al., 2009). A 13-country European study found that students saw online learning as less effective than in-person learning (Tartavulea et al., 2020). A South African-based study found online-learning students faced isolation and sometimes lacked confidence, especially those who were new to online learning (De Metz & Bezuidenhout, 2018).

2.3. Perceptions of online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic

During the COVID-19 pandemic, empirical research found similar themes of flexibility and convenience motivating students to prefer online learning (Muthuprasad et al., 2021). When Harvard medical students were forced to go remote with their education, student evaluations of the experience revealed a conducive learning environment, with high course ratings (Goldenson et al., 2021). From nursing students who were able to use training videos for active learning (Zhou et al., 2020) to accounting majors where online students overwhelmingly outperformed in-person and hybrid students (McCarthy et al., 2019), online learning benefits continued throughout the pandemic.

However, criticisms were also present. One study found students strongly preferred face-to-face classes (Aguilera-Hermida, 2020) while others found technical issues like internet connectivity were a common problem in developing countries (Muthuprasad et al., 2021). Moreover, the pandemic may have induced additional burdens, and several studies found evidence of increased levels of anxiety and stress, lack of focus, and fatigue in students, which may have affected their perceptions of online learning (Curelaru et al., 2022; Parker et al., 2021).

2.4. Perceptions of camera use in online synchronous learning

An important aspect of live online learning is the use of cameras to connect in the virtual environment. Most teachers make camera use optional but then, few students keep their cameras on, resulting in a disconnected educational experience (Castelli & Sarvary, 2021) and slower pace (Kahn, El Kouatly Kambris, & Alfalahi, 2021). Students have generally reported minimal camera use when not required (Bucholz, 2020; Melgaard et al., 2022; Hariharan & Merkel, 2021), acknowledging self-consciousness, uncomfortable surroundings, feeling insecure (Bashir et al., 2021; Bergdahl et al., 2022; Kahn et al., 2021), and also internet connection and focus issues (Castelli & Sarvary, 2021). Adherence to social norms is also important: Hariharan & Merkel (2021) found 94% of students favored keeping their cameras off for fear of being the only visible student.

Conversely, research suggests that when cameras are on, physical appearance and visible background become the primary focus of students, creating significant barriers to engagement with course material (Castelli & Sarvary, 2020; Neuwirth et al., 2021; Rajab & Soheib, 2021). This problem may be exacerbated for marginalized populations whose race, ethnicity, or gender identity may affect camera use (Oinas et al., 2022; Aresan & Tiru, 2022; Castelli & Sarvary, 2021). Research also finds that students report wanting others to keep their cameras on for increased interactivity and intimacy in the classroom (Schwenck & Pryor, 2021; Sedereviciute-Paciauskien et al., 2022). Additionally, students prefer professors to keep their cameras on (Kahn et al., 2021).

Amidst these mixed findings, students often feel they should make decisions about turning on their camera (Williams & Pica-Smith, 2022). On the other hand, teachers feel a heightened sense of responsibility for their students’ success and, when cameras remain off, they frequently experience the sensation of “teaching into the void” (p. 39). Overall, reduced camera use appears to be common in sync online classrooms but may cause decreased levels of engagement and poorer educational experiences (Melgaard et al, 2022; Cavinato et al., 2021).

2.5. Gendered differences in higher education and online learning

Recognizing gender differences in experiences of students with online learning can help improve student engagement and success. Literature on gender differences in response to online learning has been of significant interest following the pandemic, mainly regarding STEM students due to gender biases in these fields (Nadile et al., 2021; Stolk et al., 2021).

Research has shown that women in STEM were nearly three times less likely to feel comfortable asking or answering questions in class, despite their race, generation status, GPA, or academic year compared to men (Nadile et al., 2021). Women reported decreased confidence in material and increased fear of judgement from peers or instructors. Female STEM majors reported increased external motivations in seeking self-improvement (Stolk et al., 2021). Even in the social sciences, where women make up a larger portion of students, such gendered differences in learning comfort may still exist; in a survey of political science students, females enrolled in more online courses while males had primarily on-campus schedules (Glazier, Hamann, Pollock, & Wilson, 2019).

Evidence suggests the shift to online learning may have also exacerbated pre-existing physical and mental health conditions (i.e. anxiety), particularly for female students (Li & Che, 2022). Considering synchronous learning and camera use, Castelli and Sarvary (2021) found female students more likely to report concerns over their appearance, physical location, or the presence of others in their background, perhaps indicative of symptomology of social anxiety. Conversely, some studies found support for a higher female student satisfaction with online learning (Aresan & Tiru, 2022; Chung et al., 2020; Elkins et al., 2021) and their greater confidence in these settings (Aresan & Tiru, 2022). Female participants were more comfortable speaking during online courses, using their camera, and being satisfied with teachers’ pedagogy (Aresan & Tiru, 2022). Together, these findings suggest that the traditional classroom or spaces in which women must display themselves may provoke a social anxiety associated with gendered expectations whereas online learning, according to Aresan and Tiru (2022), may provide a reprieve from the anxious conditions associated with such emotion work. The experience of social anxiety in these settings may also align with the concerns of female STEM students in the prior paragraph (Stolk et al., 2021), in which women feel far less comfortable asking questions or engaging in the coursework in front of others.

2.6. Educational experiences and perceptions of Black and Hispanic students

Before examining the experiences of Black and Hispanic college students, it is imperative to acknowledge the systemic challenges they incur throughout primary and secondary education.

2.6.1. Structural disparities

Structural limitations in education are a common challenge within both Black and Hispanic communities. Chakraborty and Bosman (2005) found significant inequalities regarding personal computer ownership in Black compared to White households. Despite efforts to close this gap, the “digital divide” is still a prevalent concern (Vigdor et al., 2014). These issues were exacerbated during the COVID-19 pandemic, as the shift to online learning posed a significant barrier to success for students who may not have equal access to technology (Hassan & Daniel, 2020). Friedman et al. (2021) found that 10.1% of children were without adequate access to internet and electronic devices in 2020. Of those, the largest group of individuals who reported insufficient technological access were Black children whose parents had less than a high school education.

During the height of the pandemic, non-White students faced many barriers while navigating the educational system (Allen et al., 2020). Hispanic students were more likely to engage in remote learning and struggle with technical issues in K-12 education (Dorn et al., 2020a, Dorn et al., 2020b). Both Black and Hispanic students are more likely to live in poverty (Gaitan, 2013) and struggle to participate in online instruction, which led to learning loss during the pandemic (Dorn et al., 2020a, Dorn et al., 2020b).

2.6.2. Online learning in college

Hispanic and Black students share challenges within higher education as well: compared to White students, Black and Hispanic students are 2.7 and 1.8 times less likely, correspondingly, to own a laptop (Reisdorf et al., 2020). Students among minority demographic groups report lower satisfaction with online education overall and greater challenges with peer and professor interactions (Arbelo et al., 2019; Ke & Kwak, 2013). When on camera in sync classes, Hispanic students are more concerned about their appearance (Castelli & Sarvary, 2021). However, other studies find that Hispanic students appreciate the convenience and flexibility of asynchronous online classes, citing the need to juggle multiple roles/responsibilities (Means & Neisler, 2021; Kumi-Yeboah, 2018) while also emphasizing self-motivation and individual agency associated with online learning (Kauffman, 2015; Arbelo et al., 2019).

Perceived levels of racism and discrimination amongst non-White students can also have a detrimental effect on student learning and educational achievement (Brown et al., 2005; Johnson et al., 2007). Perceived lack of diversity on campus may also threaten some students’ sense of belonging (Gao & Liu, 2021) and lead minority students to prefer online education, which we assess in our study.

The focus of our study on these demographic groups is particularly important given recent collegiate enrollment trends. In 2021, the Hispanic college student population increased by more than 40% (Krogstad, Passel, & Noe-Bustmante, 2020), while the Black college student population has been steadily decreasing (Miller, 2020). With a booming Hispanic and dwindling Black student population, we need to better understand the perspectives and preferences of these groups regarding online learning.

2.7. Experiences of international students

Research that draws a comparative analysis between international and domestic college students in the U.S. is limited (Han et al., 2022; Li & Che, 2022), though there are some studies that have examined this aspect outside of the U.S. (Cranfield et al., 2021; Demuyakor, 2020). For example, Demuyakor (2020) examined the perception of online learning in China by international (Ghanaian) students: most were pleased with the effectiveness and credibility of online course content, but they mentioned two drawbacks: the lack of social interaction and high cost of internet data.

Han et al. (2022) interviewed 7 international graduate students in U.S. institutions. While professors helped students cope with the pandemic transition, students felt professors were more accessible in person than online. Lack of interactions with peers was also taxing. However, online discussion mode was preferred over in-person one due to ease and comfort (Han et al., 2022). Relatedly, Li and Che (2022) found international students used cameras less often in online classes, especially in classes of larger sizes.

The paucity of studies comparing international and domestic students' perceptions of online learning creates a serious knowledge gap, while the enrollment of international students in U.S. institutions of higher education has been steadily growing in the past few decades (FWD.us, 2021). Thus, it is important to examine the international students’ views and experiences with online learning, which is one of our study aims.

3. Current study: data and methods

Considering the above-noted limitations in previous research, our study helps remedy many of these issues and fill the knowledge gaps by (a) expanding the sample size and versatility to allow comparisons among various demographic groups of students, and (b) timing this study to coincide with the post-pandemic return to normal operations on U.S. college campuses.

3.1. Research questions

Our main goal in this exploratory study is to better understand university students’ experiences and perceptions of online learning (both synchronous and asynchronous) when compared with traditional classes. To make the distinction between different modes of course delivery easier, we use the term “Zoom classes” when referring to live synchronous online classes that students attend virtually at the assigned class time, “async” to indicate online asynchronous courses that have no live class sessions, and “on-campus” for traditional in-person classes.

More specific research questions of our study include comparing different demographic groups of students:

-

•

What mode of course delivery (Zoom, async, or on-campus) do students prefer and why?

-

•

What do students see as the main advantages and disadvantages of online learning compared to traditional, on-campus learning?

-

•

What are the main reasons for students to keep their camera off during Zoom classes?

3.2. Survey development and administration

To investigate these questions, we conducted an anonymous online mixed-methods survey of students at a mid-size private university in the Northeast United States that has a diverse student body in the Spring 2022 semester. No exclusion criteria prevented any students at the University from participating unless they indicated that they were not at least 18 years of age. This study was approved by the University's Institutional Review Board and all participants gave informed consent prior to gaining access to the survey questions.1 Respondents were then asked to reflect on their experiences and share their views regarding advantages and disadvantages of online learning.2 The survey included yes-no, multiple-choice, and Likert-scale questions, as well as free-response questions about students' perceptions of online learning – see the full survey at tinyurl.com/tostosurvey. In the survey, we have partially adapted questions about online learning from Baczek et al. (2021), Castelli and Sarvary (2021), Gillis and Krull (2020), and Murphy et al. (2020) as we found these studies to align closely with our own goals of understanding the effects of recent changes to learning format at the university level.

3.3. Sample characteristics

Over 900 students (out of about 6000) provided responses to the survey. This is a relatively high response rate – about 15% – for this type of online surveys (Pyrczak & Tcherni-Buzzeo, 2018). At the same time, only 690 of 914 survey respondents (just over 75%) also answered the demographic portion of the survey. Demographic characteristics of these respondents are presented in Table 1 , including information on key variables of interest in our study – gender, age, race, and ethnicity – separately for international (n = 148) and domestic (n = 542) students.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of the sample, with breakdown by domestic/international student status.

| Overall |

Domestic students |

International students |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 235 | 34.1% | 157 | 29.0% | 78 | 52.7% |

| Female | 419 | 60.8% | 352 | 65.1% | 67 | 45.3% |

| Transgender | 6 | 0.9% | 6 | 1.1% | 0 | 0.0% |

| Nonbinary | 21 | 3.0% | 18 | 3.3% | 3 | 2.0% |

| Other | 8 | 1.2% | 8 | 1.5% | 0 | 0.0% |

| Race | ||||||

| Native American | 2 | 0.3% | 2 | 0.4% | 0 | 0.0% |

| Asian | 132 | 19.3% | 22 | 4.1% | 110 | 74.3% |

| Black/African American | 71 | 10.4% | 47 | 8.8% | 24 | 16.2% |

| White/Caucasian | 434 | 63.5% | 431 | 80.6% | 3 | 2.0% |

| Other | 43 | 6.3% | 32 | 6.0% | 11 | 7.4% |

| Ethnicity | ||||||

| Hispanic/Latinx | 98 | 14.3% | 92 | 17.0% | 6 | 4.1% |

| Non-Hispanic | 589 | 85.7% | 449 | 83.0% | 140 | 95.9% |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 375 | 54.9% | 373 | 69.7% | 2 | 1.4% |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 62 | 9.1% | 39 | 7.3% | 23 | 15.5% |

| Age | ||||||

| 18–21 | 348 | 51.3% | 338 | 63.2% | 10 | 6.9% |

| 22–30 | 237 | 34.9% | 126 | 23.6% | 11 | 77.1% |

| 31+ | 94 | 13.8% | 71 | 13.3% | 23 | 16.0% |

| Class level | ||||||

| Freshman | 79 | 11.5% | 68 | 12.6% | 11 | 7.4% |

| Sophomore | 108 | 15.7% | 105 | 19.4% | 3 | 2.0% |

| Junior | 116 | 16.8% | 115 | 21.3% | 1 | 0.7% |

| Senior | 112 | 16.3% | 110 | 20.3% | 2 | 1.4% |

| Master's | 260 | 37.7% | 130 | 24.0% | 130 | 87.8% |

| Ph.D. | 14 | 2.0% | 13 | 2.4% | 1 | 0.7% |

| Residential Status | ||||||

| On-campus | 241 | 34.9% | 233 | 43.0% | 8 | 5.4% |

| Commuter | 355 | 51.4% | 220 | 40.6% | 135 | 91.2% |

| Fully online |

94 |

13.6% |

89 |

16.4% |

5 |

3.4% |

| Total | 690 | 100% | 542 | 78.6% | 148 | 21.4% |

Note: Most demographic variables have some missing data.

3.4. Analytical approach: mixed methods

A combination of closed-ended and open-ended questions in the survey provided opportunities for employing mixed methods research.

3.4.1. Quantitative analysis

Statistical analyses are based on students' answers to closed-ended questions regarding students’ preferences of the type of class (on-campus, Zoom, or async), keeping their camera off during Zoom classes, and their views on advantages and disadvantages of online learning. When comparing categorical responses across demographic groups, we used chi-square tests to determine whether the differences are statistically significant (the results of chi-square tests are listed underneath each table, Table 2, Table 3, Table 4, Table 5 ).

Table 2.

Class type preference by demographic group.

| On-campus/In-Person |

Zoom/Online Synchronous |

Independent/Online Asynchronous |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 131 | 66.5% | 38 | 19.3% | 34 | 17.7% |

| Female | 231 | 60.9% | 50 | 13.4% | 110 | 29.0% |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||||

| Black non-Hispanic | 30 | 58.8% | 16 | 31.4% | 8 | 16.0% |

| Hispanic | 52 | 56.5% | 13 | 14.1% | 29 | 32.2% |

| White non-Hispanic | 234 | 65.9% | 30 | 8.6% | 95 | 26.8% |

| Student status | ||||||

| Domestic | 322 | 63.5% | 53 | 10.6% | 140 | 27.7% |

| International | 60 | 58.3% | 39 | 37.5% | 15 | 15.0% |

Note: Group differences statistically significant at the 0.05 level are marked in bold. Below are the chi-square results for specific demographic group comparisons.

Male vs female – preference for async classes: χ2 (df = 1, N = 571) = 8.65, p = .003.

Race/ethnicity – preference for Zoom classes: χ2 (df = 2, N = 493) = 22.47, p < .001.

Domestic vs international – preference for Zoom classes: χ2 (df = 1, N = 604) = 48.25, p < .001.

Domestic vs international – preference for async classes: χ2 (df = 1, N = 605) = 7.09, p = .008.

Table 3.

Gender preferences in online learning.

| Male |

Female |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | |

| Advantages of Online Learning | ||||

| Access to Online Materials | 125 | 53.0% | 193 | 46.1% |

| Learning at Own Pace | 157 | 66.5% | 271 | 64.7% |

| Ability to Stay at Home | 161 | 68.2% | 307 | 73.3% |

| Class interactivity | 13 | 5.5% | 19 | 4.5% |

| Ability to Record a Meeting | 87 | 36.9% | 132 | 31.5% |

| Comfortable Surroundings | 116 | 49.2% | 254 | 60.6% |

| Disadvantages of Online Learning | ||||

| Reduced Teacher Interaction | 166 | 70.3% | 289 | 69.0% |

| Technical Problems | 96 | 40.7% | 176 | 42.0% |

| Lack of Peer Interaction | 155 | 65.7% | 245 | 58.5% |

| Poor Learning Conditions at Home | 37 | 15.7% | 65 | 13.4% |

| Lack of Self-Discipline | 82 | 34.7% | 171 | 40.8% |

| Social Isolation | 99 | 42.0% | 173 | 41.3% |

| Ever Kept Camera Off? | ||||

| Yes | 168 | 71.5% | 350 | 83.9% |

| Reasons for Keeping Cameras Off | ||||

| Self-Consciousness | 44 | 27.0% | 169 | 49.7% |

| Social conformity | 40 | 24.4% | 80 | 23.5% |

| Distractions/Multi-Tasking | 46 | 28.0% | 126 | 37.0% |

| Technical Issues | 18 | 11.0% | 11 | 3.2% |

Note: Group differences statistically significant at the 0.05 level are marked in bold. Below are the chi-square results for male v. female group comparisons.

Advantage – Comfortable surroundings: χ2 (df = 1, N = 655) = 8.08, p = .004.

Disadvantage – Distractions/multi-tasking: χ2 (df = 1, N = 505) = 3.91, p = .05.

Disadvantage – Self-consciousness: χ2 (df = 1, N = 503) = 23.28, p < .001.

Disadvantage – Technical issues: χ2 (df = 1, N = 503) = 12.36, p < .001.

Turning off camera during class: χ2 (df = 1, N = 652) = 14.25, p = .001.

Camera off due to self-consciousness: χ2 (df = 1, N = 503) = 23.28, p < .001.

Camera off due to distractions/multi-tasking: χ2 (df = 1, N = 503) = 3.91, p = .05.

Camera off due to technical issues: χ2 (df = 1, N = 503) = 12.36, p < .001.

Table 4.

Racial and ethnic differences in online learning.

| Black Non-Hispanic |

Hispanic |

White Non-Hispanic |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Advantages of Online Learning | ||||||

| Access to Online Materials | 31 | 50.0% | 56 | 57.1% | 160 | 42.6% |

| Learning at Own Pace | 47 | 75.8% | 62 | 63.3% | 229 | 60.9% |

| Ability to Stay at Home | 45 | 72.6% | 74 | 75.5% | 293 | 77.9% |

| Class Interactivity | 2 | 3.2% | 8 | 8.2% | 6 | 1.6% |

| Ability to Record a Meeting | 28 | 45.2% | 32 | 32.7% | 98 | 26.1% |

| Comfortable Surroundings | 28 | 45.2% | 55 | 56.1% | 223 | 59.3% |

| Disadvantages of Online Learning | ||||||

| Reduced Interaction with the Teacher | 38 | 61.3% | 61 | 62.2% | 288 | 76.6% |

| Technical Problems | 30 | 48.4% | 40 | 40.8% | 134 | 35.6% |

| Lack of Peer Interaction | 33 | 53.2% | 51 | 52.0% | 230 | 61.2% |

| Poor Learning Conditions at Home | 8 | 12.9% | 22 | 22.4% | 55 | 14.6% |

| Lack of Self-Discipline | 29 | 46.8% | 46 | 46.9% | 150 | 39.9% |

| Social Isolation | 24 | 38.7% | 38 | 38.8% | 156 | 41.5% |

| Ever Kept Camera Off? | ||||||

| Yes | 48 | 77.4% | 81 | 82.7% | 327 | 87.7% |

| Reasons for Keeping Cameras Off | ||||||

| Self-Consciousness | 21 | 43.8% | 47 | 59.5% | 142 | 44.7% |

| Social Conformity | 12 | 25.0% | 9 | 11.4% | 83 | 26.0% |

| Distractions/Multi-Tasking | 16 | 33.3% | 28 | 35.4% | 107 | 33.5% |

| Technical Issues | 1 | 2.1% | 3 | 3.8% | 17 | 5.3% |

Note: Group differences statistically significant at the 0.05 level are marked in bold. Below are the chi-square results for race/ethnicity group comparisons.

Advantage – Access to online materials: χ2 (df = 2, N = 536) = 7.09, p = .03.

Advantage – Ability to record a meeting: χ2 (df = 2, N = 536) = 9.92, p = .007.

Advantage – Class interactivity: χ2 (df = 2, N = 536) = 11.59, p = .003.

Disadvantage – Reduced interaction with the teacher: χ2 (df = 2, N = 536) = 12.14, p = .002.

Camera off due to social conformity: χ2 (df = 2, N = 446) = 7.66, p = .02.

Table 5.

Preferences of domestic versus international students in online learning.

| Domestic |

International |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | |

| Advantages of Online Learning | ||||

| Access to Online Materials | 248 | 45.7% | 84 | 56.8% |

| Learning at Own Pace | 329 | 60.6% | 117 | 79.1% |

| Ability to Stay at Home | 421 | 77.5% | 78 | 52.7% |

| Class Interactivity | 14 | 2.6% | 19 | 12.8% |

| Ability to Record a Meeting | 156 | 28.7% | 75 | 50.7% |

| Comfortable Surroundings | 319 | 58.7% | 76 | 51.4% |

| Disadvantages of Online Learning | ||||

| Reduced Teacher Interaction | 397 | 73.1% | 83 | 56.1% |

| Technical Problems | 209 | 38.5% | 76 | 51.4% |

| Lack of Peer Interaction | 313 | 57.6% | 104 | 70.3% |

| Poor Learning Conditions at Home | 87 | 16.0% | 15 | 10.1% |

| Lack of Self-Discipline | 228 | 42.0% | 44 | 29.7% |

| Social Isolation | 221 | 40.7% | 68 | 45.9% |

| Ever Kept Camera Off? | ||||

| Yes | 459 | 85.2% | 85 | 57.4% |

| Reasons for Keeping Cameras Off | ||||

| Self-Consciousness | 216 | 48.4% | 17 | 20.5% |

| Social conformity | 104 | 23.3% | 17 | 20.2% |

| Distractions/Multi-Tasking | 150 | 33.6% | 31 | 36.9% |

| Technical Issues | 22 | 4.9% | 8 | 9.6% |

Note: Group differences statistically significant at the 0.05 level are marked in bold. Below are the chi-square results for domestic vs international group comparisons.

Advantage – Access to online materials: χ2 (df = 1, N = 691) = 5.72, p = .05.

Advantage – Learning at one's own pace: χ2 (df = 1, N = 691) = 17.33, p < .001.

Advantage – Ability to stay home: χ2 (df = 1, N = 691) = 35.73, p < .001.

Advantage – Class interactivity: χ2 (df = 1, N = 691) = 26.92, p < .001.

Advantage – Ability to record a meeting: χ2 (df = 1, N = 691) = 25.17, p < .001.

Disadvantage – Reduced teacher interaction: χ2 (df = 1, N = 691) = 15.90, p < .001.

Disadvantage – Technical problems: χ2 (df = 1, N = 691) = 7.94, p = .005.

Disadvantage – Lack of peer interaction: χ2 (df = 1, N = 691) = 7.75, p = .005.

Disadvantage – Lack of self-discipline: χ2 (df = 1, N = 691) = 7.32, p = .007.

Turning off camera during class: χ2 (df = 1, N = 687) = 54.15, p < .001.

Camera off due to self-consciousness: χ2 (df = 1, N = 529) = 22.18, p < .001.

3.4.2. Qualitative analysis: thematic coding

Analysis of qualitative responses to open-ended questions was conducted by all authors. Using principles rooted in grounded theory (Charmaz, 2002; Saldana, 2013; Emerson, 2001), these question responses were coded to uncover participant meaning and shared experiences among university students (Charmaz, 2012; Lofland et al., 2006). The qualitative questions used for coding asked students why they kept the camera off and what are the reasons for their class type preferences (on-campus, Zoom, or async).

For each question, two different authors were assigned who independently coded all responses into broad themes that emerged organically from the data. Once these themes were established, the full group of researchers met to compare findings and finalize the themes for each question. Next, a third researcher independently coded a set of 100 sequential responses to the identified themes to establish the inter-rater reliability and ensure that perceived meanings derived from qualitative responses were accurate (Armstrong et al., 1997; Belotto, 2018). Any discrepancies in the authors' coding were reconciled by the full group of researchers to arrive at the final set of codes for each student's answer. The coded themes are summarized in an online appendix at tinyurl.com/tostocodes.

3.4.3. Integration of methods

Mixed methods study design allows combining the ‘bird's eye view’ of the preferences of large groups of students in different demographic categories with an up-close and personal look into students' feelings and thoughts on the matter. In the Results section, you can see an integration of statistical analyses with students' quotes, which enhances our understanding of reality and offers a paradigm superior to single-method studies (Johnson & Onwuegbuzie, 2004; Pyrczak & Tcherni-Buzzeo, 2018).

4. Results

Among about 690 respondents who provided their demographic information, some interesting differences emerged within the demographic categories of gender, race/ethnicity, and domestic vs international student status (see Table 2 on their class type preferences), and we describe these findings in more detail below.

4.1. Gender differences

Of the 690 respondents who did indicate their gender, about 34% identified as male and 61% identified a female (Table 1). About 5% identified as transgender, non-binary or “other”. Due to the variability and low number of respondents within this latter category, the sections below focus on gender differences between males and females.

4.1.1. Gendered differences in class preference

In their preferences of synchronous online (Zoom), asynchronous online (async), and on-campus courses (see Table 2), both genders rank on-campus courses similarly, as their top choice (66.5% of males and 60.9% of females). Their preferences for Zoom classes differ, but the difference does not reach statistical significance (19.3% of males vs 13.4% of females liked Zoom classes best). Where gendered preferences differ substantially is async classes (17.7% of males vs 29% of females ranked async as their first choice, the difference is statistically significant).

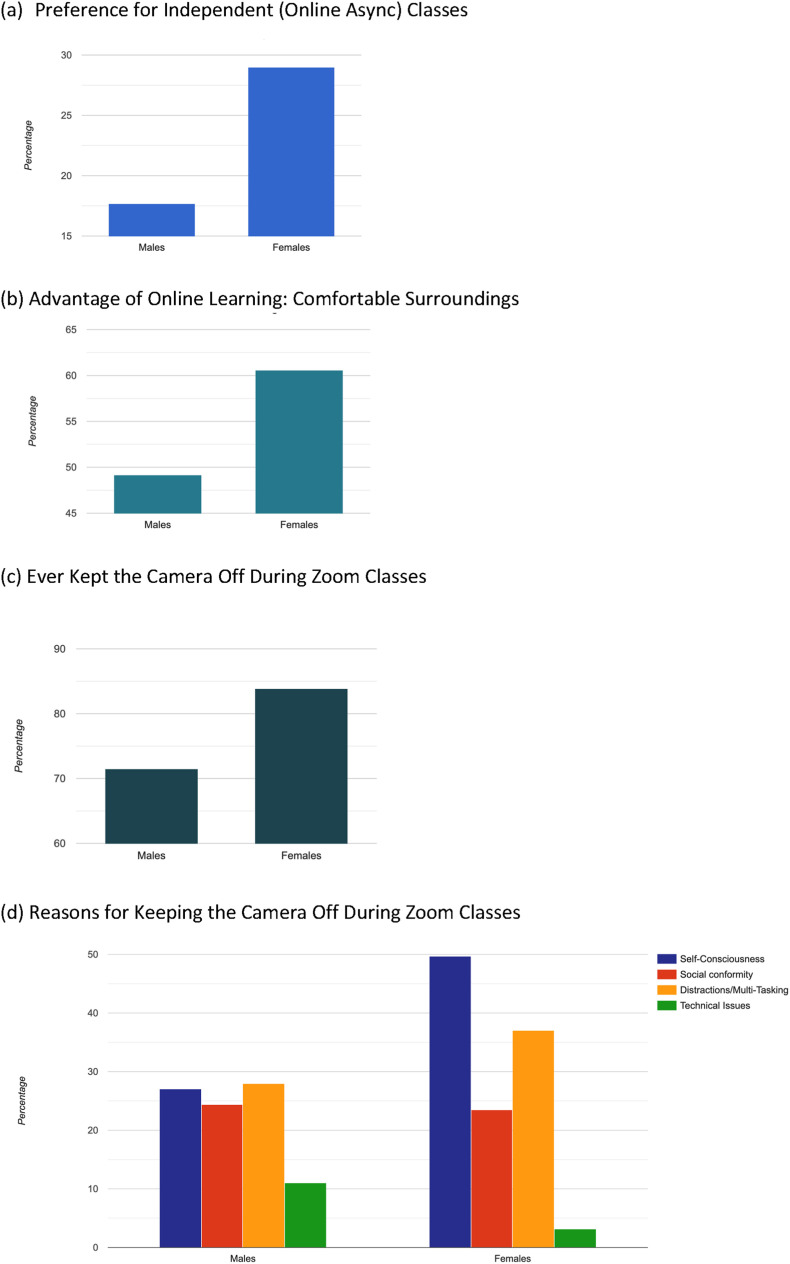

Ability to stay home was selected as the main advantage of online learning by most participants (73.3% of females and 68.2% of males), but gender differences become statistically significant only when respondents are asked specifically about comfortable surroundings as an advantage of online learning (60.6% of women chose this option compared to 49.2% of men).3 The visual representation of the key gender differences in online class preferences is presented in Fig. 1 (a) and (b). “Zoom synchronous is my favorite type of class due to the convenience and interactions. You still get the classroom experience from the comfort of your own home” (Hispanic, female, 26 years old). A close second advantage selected by almost two thirds of respondents of both genders was learning at their own pace (selected by 66.5% of males and 64.7% of females). As one participant noted, “Asynchronous learning allows for me to work at my own pace and have convenience to do schoolwork wherever I want” (White, male, 26 years old).

Fig. 1.

Key gender differences in online learning preferences

(a) preference for independent (online async) classes

(b) advantage of online learning: comfortable surroundings

(c) ever kept the camera off during zoom classes

(d) reasons for keeping the camera off during zoom classes.

Very few respondents listed class interactivity as an advantage of online learning (5.5% of men and 4.5% of women), and many of them consistently acknowledged the ability to interact with peers as a reason for why they ranked synchronous and asynchronous classes differently. “I like getting to ask questions in real-time with in-person classes. I also like seeing my classmates' faces and actually talking to them” (Hispanic, female, 22 years old). When probing the issue of interactivity further, over two thirds of both genders reported reduced teacher interaction as the main disadvantage of online education, with peer interaction being a close second. One participant clarified: “On-campus is more interactive and effective because it's one on one, [an] opportunity to relate with the professor and other students” (Black, male, 32 years old).

4.1.2. Gendered differences in camera use

After students were asked if they ever kept their camera off during Zoom classes, those who said yes (over 70% of respondents) were prompted to explain why. Their responses were then coded by the researchers according to several non-exclusive themes: self-consciousness, distractions/multi-tasking, social conformity, and technological issues.

Women were significantly more likely to keep their camera off during Zoom classes (83.9%) than men (71.5%), and females’ explanations for this often included self-consciousness as a reason to avoid camera use (49.7%) compared to only 27% of men. As one participant indicated, “I am uncomfortable with peers seeing my home environment, I do not have a private space in my home” (White, female, 21 years old). The main reason for men to turn off the camera during Zoom classes had to do with distractions or wanting to multi-task without being noticed (28%). As one participant noted, “I left my camera off due to being at work during some of the class times overlapping with my job” (White, male, 20 years old). Importantly, an even higher proportion of women (37%) listed distractions/multi-tasking reasons as well. Men and women did not significantly differ in their reporting of social conformity (aligning personal camera use with what the rest of the class was doing), but contrary to common gender stereotypes, males were significantly more likely to cite technical reasons (11%) compared to women (3.2%). It is possible that men used technical issues as a more acceptable justification for staying off camera rather than giving more personal reasons related to self-consciousness or privacy. Key gender differences in camera use and reasons for turning it off during online classes are visualized in Fig. 1(c) and (d).

4.2. Racial and ethnic differences

Among the respondents who provided their demographic information, 375 (54.9%) were non-Hispanic White, 62 (9.1%) were non-Hispanic Black, and 98 (14.3%) identified as Hispanic (see Table 1). For convenience, hereinafter we will use “Black” and “White” in the text when referring to “non-Hispanic Black” and “non-Hispanic White”. Even though a large percentage of students identified as Asian (132, or 19.3%), most of them were international students (see Table 1), with origins as wide-ranging as Taiwan, India, Saudi Arabia, and Indonesia, among many other Asian countries. Thus, analyzing these students as a uniform group would have been misleading. The sections below present analyses for Black and Hispanic students, especially in comparison with White students.

4.2.1. Black students’ perspectives

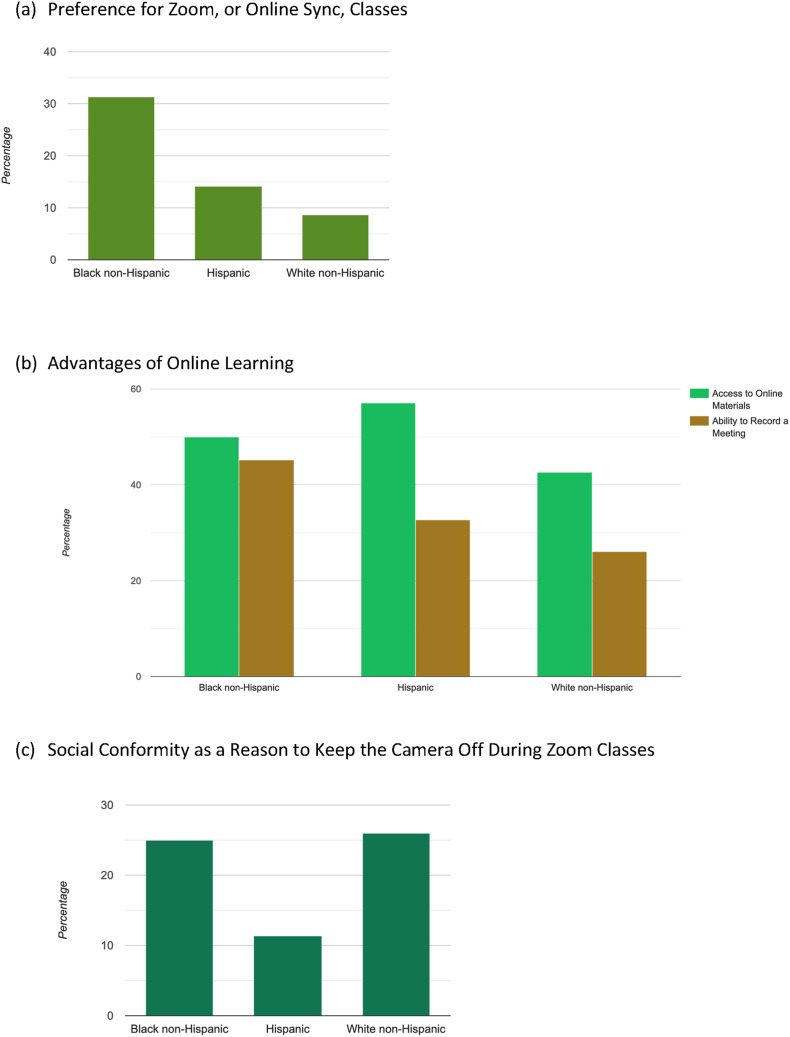

Among the survey respondents, Black students were twice as likely to prefer Zoom classes as their first choice (31.4%) compared to Hispanic (14.1%) or White students (8.6%) – see Table 2. As the main advantage of online learning (see Table 4), Black students especially note the convenience of learning at their own pace (75.8% vs 63.3% of Hispanics and 60.9% of Whites, just below statistical significance). Qualitative analysis revealed this preference to be related to participation in extracurriculars like sports and internships. “Sometimes internships, jobs, or home life come in the way, and it is not as easy to travel to campus.” (Black, female, 21 years old).

Additionally, Black students are significantly more likely to highlight a key feature of the software used for online synchronous classes: the ability to record and upload any class meeting to accessible educational platforms. This allows students to rewatch certain parts of a lecture, pause to take additional notes, or watch entire lectures missed due to athletics, sickness, or another circumstance. “I prefer synchronous classes because most professors will record the course if someone were to miss it, and as a student-athlete, it's hard to avoid missing one or two classes because of games. The synchronous classes also give me the ability to attend class almost anywhere … with on-campus courses, it is easier to fall behind if you miss a class because it is not recorded …” (Black, female, 19 years old). Other students note their preference for Zoom as “getting to class can be difficult” (Black female, 19 years old) or describe their preference for synchronous courses because of the ability to “learn in the comfort of [their] home” (Black, male, 23 years old).

Although Black students like Zoom courses, they seem to dislike asynchronous ones (16% of Black versus 32.2% of Hispanic and 26.8% of White students choose async as #1) – see Table 2. At the same time, these differences do not reach statistical significance at the conventional p < .05 level, and many of the disadvantages of online learning are judged by these racial/ethnic groups similarly (see Table 4). For example, self-discipline necessary for success in async courses is identified as a problem for online learning by almost 47% of Black and Hispanic students and by 39.9% of White students (see Table 4). “For independent work, students must have discipline to complete the work online” (Black, female, 40 years old). Additionally, some students mentioned that asynchronous courses unintentionally encourage students to “just get the work done” for the grade, rather than for education. “Asynchronous is last because I tend to not learn very often … and just complete assignments just to get them done.” (Black, female, 19 years old). Interestingly, the only statistically significant difference among racial/ethnic groups in the disadvantages of online learning was reduced interaction with the teacher: White students (76.6%) are much more likely than Black (61.3%) or Hispanic (62.2%) students to be bothered by this. “Nothing compares to in-person learning; the social environment, the increased opportunity to ask questions or have your confusion noticed by professors … is best in person.” (White, female, 21 years old).

4.2.2. Hispanic students’ perspectives

Unlike Black students, Hispanic students like online asynchronous classes (32.2% of Hispanics rated online asynchronous as their preferred class type, compared to 16% of Black students – see Table 2). Even though these differences did not reach statistical significance, qualitative analyses revealed that, for many Hispanic students, asynchronous classes stood out for convenience-associated factors. “I'm remote and 2 h away from school so having online classes is a cheaper and better option” (Hispanic, female, 22 years old). Juggling multiple responsibilities also seemed to be a common reason for preferring asynchronous classes among Hispanic students, and this extended beyond time needed for extracurricular activities: “As a student and full-time mental health worker, independent work is more sustainable and better suited to my needs” (Hispanic, female, 27 years old). Another student notes: “As a working professional, I need flexibility in the hours I choose to do class and assignments” (White, female, 19 years old).

Other students put an emphasis on individualism for preferring asynchronous learning. “It provides additional time for me to further research if I do not understand something and if I am reading a textbook, I can re-read it as many times as I want without the pressure of having to hurry because of a timeline” (Hispanic, female, 41 years old). Agency over one's learning is a common theme. “At times where I feel more productive, I can do my work at that time rather than having a scheduled meeting time” (Hispanic, male, 23 years old). Interestingly, the individualistic aspect is also reflected in Hispanic students being less likely to worry about social conformity when turning their camera off during Zoom classes: only 11.4% of Hispanics mentioned social conformity versus 25% of Blacks and 26% of Whites, and this difference is statistically significant (see Table 4). We visualized the differences among racial/ethnic categories in online learning preferences in Fig. 2 .

Fig. 2.

Key racial/ethnic differences in online learning preferences

(a) preference for zoom, or online sync, classes

(b) advantages of online learning

(c) social conformity as a reason to keep the camera off during zoom classes.

Continuing with the qualitative analyses of student responses, we see other reasons for Hispanic students to prefer asynchronous classes:

-

•

“It works better for my needs rather than attending physical classes. I'm also 30 years old, so being surrounded by 18-year-olds in school feels really weird” (Female, 29 years old).

-

•

“I love [asynchronous] classes because I hate lectures … In the other classes you are forced to interact with professors … Most classes you are talked at and then you leave” (Female, 20 years old).

4.3. Differences between international and domestic students

We see drastically different preferences of domestic and international students for Zoom and asynchronous online class: international students prefer Zoom classes almost 4 times more (37.5%) than domestic students (10.6%), while domestic students prefer async classes almost twice as often (27.7%) as international students (15%), and these differences are statistically significant (see Table 2). However, international students’ preferences in the mode of course delivery (on-campus, Zoom, or async) are difficult to interpret properly since their choice of online classes may be severely limited due to U.S. visa restrictions limiting the number of online (async) courses for international students within the U.S., whereas domestic students are able to enroll in fully online courses with no restrictions in the U.S.

Additional information is provided in Table 5 on how differently international and domestic students perceive advantages and disadvantages of online learning (almost all differences are statistically significant). 79.1% of international students chose learning at one's own pace as the top advantage of online learning (vs 60.6% of domestic students), while domestic students see the ability to stay home as the main advantage of online learning (77.5% of domestic vs 52.7% of international). International students are almost twice as likely as domestic students to emphasize the ability to record a meeting (50.7% vs 28.7%) and almost 5 times more likely to underscore class interactivity (12.8% vs 2.6%) as benefits of online learning.

Among the disadvantages of online learning, lack of peer interaction is the main problem for international students (70.3%) while only 57.6% of the domestic group named it as a problem. Conversely, reduced interaction with a teacher ranked high among domestic students (73.1%) while being less of a problem for international students (56.1%). International students are much less likely to worry about self-discipline required for online learning (29.7% vs 42% of domestic students).

When using camera during Zoom classes, international students are less likely to turn their camera off than domestic students (57.4% vs 85.2%). They are also significantly less likely to mention self-consciousness or privacy as a reason for turning of the camera (20.5% of international vs 48.4% of domestic students). Almost half of domestic students expressed concerns about appearance or privacy. “I am self-conscious of my image and do not want to show myself when I am home” (White, non-binary, 22 years old) and “I don't want people seeing me in my living area. It is a private space that I share with people who I want to share it with, not random classmates …” (White, male, 21 years old).

5. Discussion

Our study examines the preferences and opinions of college students regarding various aspects of online learning, such as preferred class type (on-campus, Zoom, and asynchronous online), decisions to turn the camera off during Zoom classes and reasons behind these decisions, and views on advantages and disadvantages of online learning. Having a large and versatile sample from a mid-size university in the Northeast answering our anonymous survey allows us to use mixed methods to compare students of various demographic groups in their views and preferences.

We find that men and women have different preferences for asynchronous online classes, 28% of women but only 17% of men ranking it as their first choice. This is likely related to the camera use in synchronous class: women prefer to turn the camera off during online classes, mentioning self-consciousness as a common reason. In other ways, both genders are very similar in their views of online learning.

Class type preferences differ significantly among Black, White, and Hispanic students, with Black students preferring Zoom classes at a higher rate (31.4%) than online asynchronous ones (16%), and Hispanic students preferring asynchronous courses (32.2%) to Zoom classes (14.1%). These findings echo existing research, which finds that Hispanic students much more often than non-Hispanics cite challenges managing responsibilities at home with their educational obligations and find online options more convenient (Means & Neisler, 2021; Kumi-Yeboah, 2018). Overall, flexibility and convenience of online learning is a prominent factor identified in previous studies to be important for students (Alexander et al., 2009; Muthuprasad et al., 2021; Nollenberger, 2015), and our study adds to this body of evidence.

Lack of interaction with professors was the only significant difference observed among the racial and ethnic groups, with 76.6% of White students noting this as a disadvantage of online learning compared to 62.2% of Hispanic students and 61.3% of Black students. In fact, perceived lack of interaction or sense of community among online students has been noted as one of the main online learning challenges by previous researchers (De Metz & Bezuidenhout, 2018; Nollenberger, 2015; Song et al., 2004).

International students' preferences in terms of the mode of course delivery may be limited due to visa restrictions, so the exact interpretation of these differences between international and domestic students is unclear. In terms of online learning advantages, international students prefer learning at their own pace (79.1%) and the ability to record a meeting (50.7%), while domestic students prefer being able to stay at home (77.5%) as the main advantage of online learning. The main disadvantage of online learning for international students is lack of peer interaction (70%) while for domestic students, it is reduced interaction with the teacher (73%). It also emerged in our study that international students are much less likely to turn off their camera during Zoom classes or to mention self-consciousness/privacy as a reason for doing so.

Our findings echo the results of some prior research, although studies that draw comparisons between international and domestic students are scarce (Han et al., 2022; Li & Che, 2022). Previous studies reported that international students struggled with a lack of social interaction generally (Demuyakor, 2020) and peer interaction more specifically (Han et al., 2022). Another study, though conducted outside the U.S., found that students (in Wales, South Africa, and Hungary) reported a lack of peer interaction as a significant disadvantage of online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic (Cranfield et al., 2021).

5.1. Study limitations and directions of future research

Since our survey relies on a convenience sample, the question naturally arises whether the students who answered the survey are different from those did not (self-selection bias). A relatively high response rate and the fact that the demographics of our sample closely resemble the demographics of the university overall assuage these concerns. Like any self-report survey, our study relies on people's own opinions about themselves, and these opinions may be distorted by social desirability. However, this concern is minimized by the anonymity of the survey. In addition, the survey itself was not empirically validated in either the prior studies from which questions were adapted or the current work. While this poses a minor limitation, the questions were adapted to apply specifically to the potential experiences of students at the studied University, making our concern over this issue quite minimal.

It is possible that the experiences of students are unique to the university from which the sample was drawn since the faculty at this university had extensive preparation and training for online learning and course hybridization well before the start of the COVID-19 pandemic (so the transition to online learning likely went more smoothly than it could have gone otherwise). However, enough time has passed from the initial hectic stage of the pandemic switch to online learning, and extensive training in online delivery methods has been conducted in many colleges since then. Future studies at other universities and colleges will be able to answer the questions of generalizability more fully.

Another limitation is that we have not been able to meaningfully incorporate some gender categories (for example, non-binary and transgender students) and races (for example, Asian students). This is an important direction of future research with more targeted samples. While exploratory analyses were conducted in these areas, it was also beyond the scope of this single paper to review findings related to class differences, experiences of graduate versus undergraduates, and other characteristics that may affect these class-based experiences. However, we believe that the gendered, racial, and ethnic differences explored here provide particularly salient and timely consideration of the needs of today's student populations.

5.2. Implications for practice

The results of our study, even taking limitations into account, are valuable for informing not only future research but also educational practices at the institutions of higher education. Depending on the demographic makeup of the student body or students taking specific courses, college administrators and faculty can adjust their approaches to meet the preferences and constraints of their students and more accurately anticipate student demand for specific online course modalities.

At the same time, it may be premature to make specific or far-reaching recommendations based on the results of one study. It would be important to first see some replications and extensions of this research on different student populations, to ensure that the demographic differences among college students in their preferences for online learning, which we have uncovered in our study, hold in different contexts. Moreover, we encourage faculty to use the survey questions listed at tinyurl.com/tostosurvey to poll your students on those aspects of course delivery and educational practice that you are considering changing or updating.

6. Conclusions

This is one of the first studies that included a comprehensive assessment of student views on various aspects of online learning and comparisons across several important demographic groups of students: based on gender, race/ethnicity, and international versus domestic student status, while using a large and diverse sample of students at a mid-size university in Northeastern United States. The insights gained in this study are an important post-pandemic update on online learning research and should inform future studies and help make educational practices more sensitive to the needs of specific demographic groups of students.

Credit Author Statement:

Online learning in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic: Mixed-methods analysis of student views by demographic group

Samantha A. Tosto: conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, investigation, writing - original draft, writing - review & editing.

Jehad Alyahya: conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, investigation, writing - original draft, writing - review & editing.

Victoria Espinoza: conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, investigation, writing - original draft, writing - review & editing.

Kylie McCarthy: conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, investigation, writing- original draft, writing- review & editing.

Maria Tcherni-Buzzeo, PhD: conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, investigation, writing - original draft, writing - review & editing, supervision.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

Our sincere gratitude goes to the anonymous reviewers who provided excellent feedback and insightful suggestions to improve this paper. Any remaining shortcomings of the paper are exclusively our responsibility as the authors. We are also very grateful to Patryk Jaroszkiewicz for his contributions at the early stages of this research project.

Footnotes

The use of the survey was approved as exempt by the Institutional Review Board of the researchers' university, in IRB Protocol #2022-039.

As an incentive, the participants were offered a chance to win one of five $25 Amazon gift cards by providing an email address in a separate raffle disconnected from their survey responses.

This difference between genders held significance in regression analyses, even when accounting for age and race/ethnicity (results are available from the corresponding author upon request).

References

- Aguilera-Hermida A.P. College students' use and acceptance of emergency online learning due to COVID-19. International Journal of Educational Research Open. 2020;1 doi: 10.1016/j.ijedro.2020.100011. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S266637402030011X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander M.W., Perreault H., Zhao J.J., Waldman L. Comparing AACSB faculty and student online learning experiences: Changes between 2000 and 2006. Journal of Educators Online. 2009;6(1):n1. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ904063.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Allen J., Mahamed F., Williams K. Disparities in education: E-Learning and COVID-19, who matters? Child & Youth Services. 2020;41(3):208–210. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/0145935X.2020.1834125 [Google Scholar]

- Arbelo F., Martin K., Frigerio A. Hispanic students and online learning: Factors of success. HETS Online Journal. 2019;9(2) https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A596061560/AONE [Google Scholar]

- Aresan D., Tiru L.G. Student satisfaction with the online teaching process. Academicus International Scientific Journal. 2022;13(25):184–193. https://www.ceeol.com/search/article-detail?id=1010131 [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong D., Gosling A., Weinman J., Marteau T. The place of inter-rater reliability in qualitative research: An empirical study. Sociology. 1997;31(3):597–606. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0038038597031003015 [Google Scholar]

- Baczek M., Zaganczyk-Baczek M., Szpringer M., Jaroszynski A., Wozakowska-Kaplon B. Students' perception of online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic: A survey study of polish medical students. Medicine. 2021;100(7):1–6. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000024821. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7899848/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bashir A., Bashir S., Rana K., Lambert P., Vernallis A. Post- COVID-19 adaptations: The shifts towards online learning, hybrid course delivery and the implications for biosciences courses in the higher education setting. Frontiers in Education. 2021;6 doi: 10.3389/feduc.2021.711619. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Belotto M.J. Data analysis methods for qualitative research: Managing the challenges of coding, interrater reliability, and thematic analysis. Qualitative Report. 2018;23(11):2622–2633. https://www.proquest.com/openview/21b8de9a65315a8d00d10bbe0a8b062d/1 [Google Scholar]

- Brown R.A., Morning C., Watkins C. Influence of African American engineering student perceptions of campus climate on graduation rates. The Journal of Engineering Education. 2005;94:263–271. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/j.2168-9830.2005.tb00847.x [Google Scholar]

- Bucholz E.K. Creating a welcoming and engaging environment in an entirely online biomedical engineering course. Biomedical Engineering Education. 2020;1(1):165–169. doi: 10.1007/s43683-020-00024-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bygstad B., Øvrelid E., Ludvigsen S., Dæhlen M. From dual digitalization to digital learning space: Exploring the digital transformation of higher education. Computers & Education. 2022;182 https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0360131522000343 [Google Scholar]

- Castelli F.R., Sarvary M.A. Why students do not turn on their video cameras during online classes and an equitable and inclusive plan to encourage them to do so. American Practice in Ecology and Evolution. 2021;11(8):3565–3576. doi: 10.1002/ece3.7123. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/ece3.7123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavinato A.G., Hunter R.A., Ott L.S., Robinson J.K. Promoting student interaction, engagement, and success in anonline environment. Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry. 2021;413:1513–1520. doi: 10.1007/s00216-021-03178-x. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00216-021-03178-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty J., Bosman M.M. Measuring the digital divide in the United States: Race, income and personal computer ownership. The Professional Geographer. 2005;57(3):395–410. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.0033-0124.2005.00486.x [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz K. In: Handbook of interview research. Gubrium J.F., Holstein J.A., editors. SAGE; 2002. Grounded theory analysis; pp. 675–694. [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz K. The power and potential of grounded theory. Medical Sociology. 2012;6(1):2–15. [Google Scholar]

- Chung E., Subramaniam G., Dass L.C. Online learning readiness among university students in Malaysia amidst COVID-19. Asian Journal of University Education. 2020;16(20):46–58. https://myjms.mohe.gov.my/index.php/AJUE/article/view/10294 [Google Scholar]

- Cranfield D.J., Tick A., Venter I.M., Blignaut R.J., Renaud K. Higher education students' perceptions of online learning during COVID-19: A comparative study. Education Sciences. 2021;11(403):1–17. https://www.mdpi.com/1216712 [Google Scholar]

- Curelaru M., Curelaru V., Cristea M. Students' perceptions of online learning during COVID-19 pandemic: A qualitative approach. Sustainability. 2022;14(8138):1–21. https://www.mdpi.com/1710362 [Google Scholar]

- De Metz N., Bezuidenhout A. An importance–competence analysis of the roles and competencies of e-tutors at an open distance learning institution. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology. 2018;34(5):27–43. https://ajet.org.au/index.php/AJET/article/view/3364 [Google Scholar]

- Demuyakor J. Coronavirus (COVID-19) and online learning in higher institutions of education: A survey of the perceptions of Ghanaian international students in China. The Online Journal of Communication and Media Technologies. 2020;10(3):1–9. https://www.ojcmt.net/article/coronavirus-covid-19-and-online-learning-in-higher-institutions-of-education-a-survey-of-the-%E2%80%8E%E2%80%8E8286%E2%80%8E [Google Scholar]

- Dhawan S. Online learning: A panacea in the time of COVID-19 crisis. Journal of Educational Technology Systems. 2020;49(1):5–22. doi: 10.1177/0047239520934018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dorn E., Hancock B., Sarakatsannis J., Viruleg E. McKinsey & Company; 2020. COVID-19 and student learning in the United States: The hurt could last a lifetime.https://www.childrensinstitute.net/sites/default/files/documents/COVID-19-and-student-learning-in-the-United-States_FINAL.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Dorn E., Hancock B., Sarakatsannis J., Viruleg E. Vol. 8. McKinsey & Company; 2020. pp. 6–7.https://wasa-oly.org/WASA/images/WASA/5.0%20Professional%20Development/4.2%20Conference%20Resources/Winter/2021/covid-19-and-learning-loss-disparities-grow-and-students-need-help-v3.pdf (COVID-19 and learning loss—disparities grow and students need help). [Google Scholar]

- Eastmond D.V. Adult learners and internet-based distance education. New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education. 1998;78:33–41. https://www.learntechlib.org/p/85356/ [Google Scholar]

- Elkins R., McDade R., Collins M., King M. Student satisfaction with online learning experiences associated with COVID-19. Research Directs in Health Sciences. 2021;1(1):1–11. https://www.learntechlib.org/p/218355 [Google Scholar]

- Emerson R. Waveland Press; 2001. Contemporary field research: Perspectives and formulations. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher J.E. Magazine. Second. Vol. 10. KUHT-TV: The University of Houston’s; 2012. Great Vision. Houston History; pp. 30–34. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman J., York H., Mokdad A.H., Gakidou E. U.S. children “learning online” during COVID-19 without internet of a computer: Visualizing the gradient by race/ethnicity and parental educational attainment. Socius. 2021;7 doi: 10.1177/2378023121992607. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/2378023121992607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FWD us International students & Graduates in the U.S. FWD.us. 2021. https://www.fwd.us/news/international-students/

- Gaitan C.D. SAGE; 2013. Creating a college culture for Latino students: Successful programs, practices, and strategies. [Google Scholar]

- Gao F., Liu H.C.L. Guests in someone else's house? Sense of belonging among ethnic minority students in a Hong Kong university. British Educational Research Journal. 2021;47(4):1004–1020. https://bera-journals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/berj.3704 [Google Scholar]

- Gillis A., Krull L.M. COVID-19 remote learning transition in spring 2020: Class structures, student perceptions, and inequality in college courses. Teaching Sociology. 2020;48(4):283–299. doi: 10.1177/0092055X20954263. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/0092055X20954263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glazier R.A., Hamann K., Pollock P.H., Wilson B.M. Age, gender, and student success: Mixing face-to-face and online courses in political science. Journal of Political Science Education. 2019;16(2):142–157. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/15512169.2018.1515636 [Google Scholar]

- Goldenson R.P., Avery L.L., Gill R.R., Durfee S.M. The Virtual homeroom: Utility and benefits of small group online learning in the COVID-19 era. Elsevier Public Health Emergency Collection. 2021;51(2):152–154. doi: 10.1067/j.cpradiol.2021.06.012. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0363018821001109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han Y., Chang Y., Kearney E. “It's doable”: International graduate students' perceptions of online learning in the U.S. during the pandemic. Journal of Studies in International Education. 2022;26(2):165–182. doi: 10.1177/10283153211061433. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/10283153211061433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hariharan J., Merkel S. Classroom management strategies to improve learning experiences for online courses. Journal of Microbiology and Biology Education. 2021;22(3):1–3. doi: 10.1128/jmbe.00181-21. doi.org/10.1128/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassan S., Daniel B.J. During a pandemic, the digital divide, racism, and social class collide: The implications of COVID-19 for Black students in high schools. Child & Youth Services. 2020;41(3):253–255. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/0145935X.2020.1834956 [Google Scholar]

- Johnson R.B., Onwuegbuzie A.J. Mixed methods research: A research paradigm whose time has come. Educational Researcher. 2004;33(7):14–26. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.3102/0013189X033007014 [Google Scholar]

- Johnson D.R., Soldner M., Leonard J.B., Alvarez P., Inkelas K.K., Rowan-Kenyon H., Longerbeam S. Examining a sense of belonging among first year undergraduates from different racial/ethnic groups. Journal of College Student Development. 2007;48:525–542. https://muse.jhu.edu/pub/1/article/221315/summary [Google Scholar]

- Kahn S., El Kouatly Kambris M., Alfalahi H. Perspectives of University students and faculty on remote education experiences during COVID-19: A qualitative study. Education and Information Technologies. 2021;27:4141–4169. doi: 10.1007/s10639-021-10784-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kauffman H. A review of predictive factors of student success in and satisfaction with online learning. Research in Learning Technology. 2015;23 https://repository.alt.ac.uk/2415/ [Google Scholar]

- Ke F., Kwak D. Online learning across ethnicity and age: A study on learning interaction, participation, perception, and learning satisfaction. Computers & Education. 2013;61:43–51. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0360131512002072 [Google Scholar]

- Kentnor H.E. Distance education and the evolution of online learning in the United States. Curriculum and Teaching Dialogue. 2015;17(1):21–34. [Google Scholar]

- Krogstad J.M., Passel J.S., Noe-Bustmante L. Pew Research Center; 2020. Key facts about U.S. Latinos for national hispanic heritage month.https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2022/09/23/key-facts-about-u-s-latinos-for-national-hispanic-heritage-month/ [Google Scholar]

- Kumi-Yeboah A. Designing a cross-cultural collaborative online learning framework for online instructors. Online Learning. 2018;22(4):181–201. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1202361.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Che W. Challenges and coping strategies of online learning for college students in the context of COVID-19: A survey of Chinese universities. Sustainable Cities and Society. 2022;83 doi: 10.1016/j.scs.2022.103958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lofland J., Snow D.A., Anderson L., Lofland L. 4th ed. Wadsworth Publishing; 2006. Analyzing social settings: A guide to qualitative observation and analysis. [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy M., Kusaila M., Grasso L. Intermediate accounting and auditing: Does course delivery mode impact student performance? Journal of Accounting Education. 2019;46:26–42. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0748575118300411 [Google Scholar]

- Means B., Neisler J. Teaching and learning in the time of COVID: The student perspective. Online Learning Journal. 2021;25(1):8–27. [Google Scholar]

- Means B., Toyama Y., Murphy R., Bakia M., Jones K. The United States Department of Education; 2009. Evaluation of evidence-based practices in online learning: A meta-analysis and review of online learning studies.https://repository.alt.ac.uk/629/ [Google Scholar]

- Melgaard J., Monir R., Lasrado L.A., Fagerstrom A. Academic procrastination and online learning during the COVID -19 pandemic. Procedia Computer Science. 2022;196:117–124. doi: 10.1016/j.procs.2021.11.080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller B. American Center for Progress; 2020. It's time to worry about college enrollment declines among black students.https://www.americanprogress.org/article/time-worry-college-enrollment-declines-among-black-students/ [Google Scholar]

- Murphy L., Eduljee N.B., Croteau K. College student transition to synchronous virtual classes during the COVID-19 pandemic in northeastern United States. Pedagogical Research. 2020;5(4):1–10. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1275517.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Muthuprasad T., Aiswarya S., Aditya K.S., Jha G.K. Students' perception and preference for online education in India during COVID-19 pandemic. Social Sciences & Humanities Open. 2021;3(1) doi: 10.1016/j.ssaho.2020.100101. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2590291120300905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadile E.M., Williams K.D., Wiesenthal N.J., Stahlhut K.N., Sinda K.A., Sellas C.F., Salcedo F., Camacho Y.I.R., Perez S.G., King M.L., Hutt A.E., Heiden A., Gooding G., Gomez-Rosado J.O., Ford S.A., Ferreira I., Chin M.R., Bevan-Thomas W.D., Barreiros B.M.…Cooper K.M. Gender differences in student comfort voluntarily asking and answering questions in large-enrollment college science courses. Journal of Microbiology & Biology Education. 2021;22(2) doi: 10.1128/jmbe.00100-21. https://journals.asm.org/doi/pdf/10.1128/jmbe.00100-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuwirth L.S., Jovic S., Mukherji B.R. Reimagining higher education during and post-COVID-19: Challenges and opportunities. Journal of Adult and Continuing Education. 2021;27(2):141–156. [Google Scholar]

- Nollenberger K. Comparing alternative teaching modes in a masters program: Student preferences and perceptions. Journal of Public Affairs Education. 2015;21(1):101–114. doi: 10.1080/15236803.2015.12001819. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Oinas S., Hotulainen R., Koivuhovi S., Brunila K., Vainikainen M.P. Remote learning experiences of girls, boys and non-binary students. Computers and Education. 2022;183(1) [Google Scholar]

- Parker S.W., Hansen M.A., Baranowski C. COVID-19 campus closures in the United States: American student perceptions of forced transition to remote learning. Social Sciences. 2021;10(62):1–18. https://www.mdpi.com/2076-0760/10/2/62/pdf [Google Scholar]

- Pokhrel S., Chhetri R. A literature review on impact of COVID-19 pandemic on teaching and learning. Higher Education for the Future. 2021;8(1):133–141. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/2347631120983481 [Google Scholar]

- Pyrczak F., Tcherni-Buzzeo M. 7th ed. Routledge; 2018. Evaluating research in academic journals: A practical guide to realistic evaluation. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rajab M.H., Soheib M. Privacy concerns over the use of webcams in online medical education during the COVID-19 pandemic. Cureus. 2021;3(12):13536. doi: 10.7759/cureus.13536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reisdorf B.C., Triwibowo W., Yankelevich A. Laptop or bust: How lack of technology affects student achievement. American Behavioral Scientist. 2020;64(7):927–949. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0002764220919145 [Google Scholar]

- Saldana J. The coding manual for qualitative researchers. SAGE; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Schwenck C.M., Pryor J.D. Student perspectives on camera usage to engage and connect in foundational education classes: It’s time to turn your cameras on. International Journal of Educational Research Open. 2021;2(1) doi: 10.1016/j.ijedro.2021.100079. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Song L., Singleton E.S., Hill J.R., Koh M.H. Improving online learning: Student perceptions of useful and challenging characteristics. The Internet and Higher Education. 2004;7(1):59–70. doi: 10.1016/j.iheduc.2003.11.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stanciu V., Gheorghe M. An exploration of the accounting profession: The stream of mobile devices. Accounting and Management Information Systems. 2017;16(3):369–385. https://www.ceeol.com/search/article-detail?id=567064 [Google Scholar]

- Stolk J.D., Gross M.D., Zastavker Y.V. Motivation, pedagogy, and gender: Examining the multifaceted and dynamic situational responses of women and men in college STEM courses. International Journal of STEM Education. 2021;8(35) https://link.springer.com/article/10.1186/s40594-021-00283-2 [Google Scholar]