Abstract

Peanut is mostly grown in calcareous soils with high pH which are deficient in available iron (Fe2+) for plant uptake causing iron deficiency chlorosis (IDC). The most pertinent solution is to identify efficient genotypes showing tolerance to limited Fe availability in the soil. A field screening of 40 advanced breeding lines of peanut using NRCG 7472 and ICGV 86031 as IDC susceptible and tolerant checks, respectively, was envisaged for four years. PBS 22040 and 29,192 exhibited maximum tolerance while PBS 12215 and 12,185 were most susceptible. PBS 22040 accumulated maximum seed resveratrol (5.8 ± 0.08 ppm), ferulic acid (378.6 ± 0.31 ppm) and Fe (45.59 ± 0.41 ppm) content. Enhanced chlorophyll retention (8.72–9.50 µg ml−1), carotenoid accumulation (1.96–2.08 µg ml−1), and antioxidant enzyme activity (APX: 35.9–103.9%; POX: 51- 145%) reduced the MDA accumulation (5.61–9.11 µM cm−1) in tolerant lines. The overexpression of Fe transporters IRT1, ZIP5, YSL3 was recorded to the tune of 2.3–9.54; 1.45–3.7; 2.20–2.32- folds respectively in PBS 22040 and 29,192, over NRCG 7472. PBS 22040 recorded the maximum pod yield (282 ± 4.6 g/row), hundred kernel weight (55 ± 0.7 g) and number of pods per three plants (54 ± 1.7). The study thus reports new insights into the roles of resveratrol, ferulic acid and differential antioxidant enzyme activities in imparting IDC tolerance. PBS 22040, being the best performing line, can be the potent source of IDC tolerance for introgression in high yielding but susceptible genotypes under similar edaphic conditions.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s12298-023-01321-9.

Keywords: Iron deficiency, Tolerant and susceptible lines, Phenolics profile, Fe and Zn accumulation, Morpho-physiological traits, Yield attributes

Introduction

Peanut is a leguminous oilseed crop known for its immense potential as a functional food (Geulein 2010). It is rich in energy (564 kcal per 100 g), protein (25–30%), heart-healthy monounsaturated fatty acid (MUFA), and vital micronutrients viz., iron (Fe) and zinc (Zn), along with rare antioxidants like resveratrol, ferulic acid, and Vitamin E (Verma et al. 2022). India represents the largest area for peanut in the world but ranks second in terms of production after China and that too with a huge difference in the production metrics wherein India’s production is approximately 10 million tonnes contributing to 16.8% of the world’s peanut production while China produces 17.5 million tonnes contributing to 34.3% of world’s peanut production (average of 2018–2020; FAOSTAT; Zhou et al. 2022). The major peanut-growing states in India constitute Gujarat, Andhra Pradesh, Rajasthan, Tamil Nadu, Karnataka and Maharashtra with Gujarat contributing the maximum share (37%). The Saurashtra region of Gujarat, which is also known as the ‘groundnut bowl’ of India, is the major peanut growing belt. The soil in this region is mostly calcareous with high pH (approximately 8.0) and low organic matter content (around 0.5%), a condition which favours the transformation of the ferrous (Fe2+) form of Fe to the ferric (Fe3+) form (Baria et al. 2015) making it unavailable to the growing plant for uptake. Thus, despite Fe being the fourth most abundant element in the earth's crust, it remains in the unavailable form for plants in the soil in this part of the country. Iron is a vital component of the electron transport chain in the chloroplast (regulating photosynthesis), a cofactor for a number of key enzymes and required for chlorophyll synthesis (Rebecca et al. 2022). The Fe-deprived plants show interveinal chlorosis, initially in the young expanding leaves, which under severe deficiency, become papery white and necrotic, eventually resulting in reduced yield and poor quality of the produce (Singh et al. 2004; Su et al. 2015). This is further manifested in human beings in terms of anaemia, which is one of the most severe nutritional disorders worldwide (Schmidt et al. 2020). The plants respond to such deprivation broadly through Strategy I (reduction-based) or Strategy II (chelation-based) mechanisms. Peanut, being a dicot, reportedly follows the strategy I mechanism for Fe uptake from the soil wherein H+ extrusion in the rhizosphere facilitates the reduction of Fe (III) to Fe (II) form which gets transported through transporters present on root plasma membrane (PM) (Kumar et al. 2022). The strategy II plants comprising of grasses secrete phytosiderophores in the rhizosphere which forms Fe (III)- phytosiderophore complex that readily moves across the membranes (Lopez- Milan et al. 2012).

The management practices for alleviating Fe deficiency require repeated application of ferrous sulphate (FeSO4) due to the poor phloem mobility of Fe (Irmak et al. 2012) while the chelated Fe sources are less economical for farmers (Pattanashetti et al. 2020). Thus, even after a number of interventions, the severity of IDC can be seen in the farmer’s fields across the Saurashtra region, especially during the Kharif season. Therefore, the development of varieties tolerant to IDC remains the best option but needs sources of such tolerance for introgression. Hence, the identification of genotypes tolerant to IDC in Fe-deprived soils is of utmost priority (Pattanashetti et al. 2018). Limited reports are available in identifying IDC tolerant lines (Singh and Chaudhari 1996; Kannan 1982) and a detailed mechanistic insight into the acquisition of tolerance to IDC is much needed for selecting Fe-efficient genotypes. The screening parameters widely studied for IDC evaluation in the field are Visual Chlorotic Rating (VCR) and SPAD chlorophyll meter reading (SCMR) accompanied by yield attributes (Samdur et al. 1999). However, the morphophysiological screening needs further validation with extensive characterization of the identified genotypes before recommending as IDC tolerant and/ or Fe efficient. Thus, an experiment for screening of IDC tolerance in advanced breeding lines (ABLs) of groundnut was envisaged, using NRCG 7472 as susceptible (Mann et al. 2018) and ICGV 86031 as tolerant (Boodi et al. 2015) checks, respectively, with the following major objectives: (1) Identification of IDC tolerant ABLs based on field screening traits; (2) Understanding the mechanisms of IDC tolerance through physiological, biochemical and molecular basis; (3) Identification of genetic stock best suited for Fe limited conditions.

Materials and methods

Experimental site

The present investigation was carried out during the Kharif seasons of the years 2018, 2019, 2020, and 2021 at the experimental field of ICAR- Directorate of Groundnut Research, Junagadh, Gujarat (Lat. 21°31′ N, Long 70°36′ E) where soil is medium black and calcareous with low organic matter (0.5%) and high pH (> 8.0). The recommended package of practices was followed during the crop season with all the required plant protection measures for maintaining a healthy crop stand. During Kharif 2018 and 2019, field screening of ABLs was done based on VCR, SCMR and yield to shortlist the lines in descending order of tolerance. For the next two years viz., Kharif 2020 and 2021, the same field experiment was undertaken with all the above screening parameters with an additional component of accompanying morphophysiological, biochemical and molecular observations in the laboratory with the shortlisted contrasting ABLs for further validation of their tolerance. The soil pH and diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid (DTPA) extractable Fe during the four years of study are represented in Table 1.

Table 1.

pH and DTPA extractable Fe of the experimental field during 4 years

| Year | Mean soil pH | Mean of DTPA extractable Fe (ppm) |

|---|---|---|

| 2018 | 8.01 (± 0.10) | 3.20 (± 0.10) |

| 2019 | 7.98 (± 0.02) | 2.90 (± 0.10) |

| 2020 | 8.11 (± 0.08) | 3.33 (± 0.25) |

| 2021 | 8.12 (± 0.16) | 3.13 (± 0.21) |

Data mean of three replications; data in the parentheses represent SD

Experimental setup

The experimental material comprised 40 ABLs of peanut grown under field conditions using the Randomized Complete Block Design (RCBD) with each ABLs replicated twice. The spacing was 45 cm × 10 cm for the rows and each row was 5 m in length comprising one row for each genotype. The sampling for all the physiological, biochemical and molecular studies was done at 65–80 days after sowing (DAS), which coincides with the most active growth period of peanut (pegging and pod formation stages) between 9:00 and 11:00 h.

Visual chlorotic rating (VCR) and SPAD chlorophyll meter reading (SCMR)

The VCR of leaves was recorded at 30, 50 and 80 DAS, following Singh and Chaudhari, 1993 (where VCR ratings 1—normal green leaves with no chlorosis, 2—slight yellowing on upper leaves, 3—interveinal chlorosis in upper leaves but no stunting or necrosis, 4—Interveinal chlorosis of most of the leaves with stunting and necrosis of plant tissue, 5—severe chlorosis covering all the leaves with necrosis).

Soil Plant Analysis Device (SPAD) based Chlorophyll meter reading (SCMR) was recorded using a SPAD meter (SPAD-502, Minolta corp., USA). The leaf lamina was fully covered by the SPAD meter sensor to avoid any interference from midribs. The numerical SPAD value is directly proportional to the chlorophyll content in the leaf.

Chlorophyll a, b and carotenoid content

The Chlorophyll a (Chl a) and b (Chl b) content were estimated using the methodology of Hiscox and Israelstam (1979) with the leaves extracted in Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), recording the absorbance at 645 and 663 nm and calculation was done using the formula given by Arnon (1949). Carotenoid content was measured in the same extract with absorbance recorded at 470 nm and calculation was done using the formula given by Lichtenthaler and Welburn (1983). The contents were expressed as µg ml−1.

Fe and Zn accumulation in kernels

The kernel samples were subjected to di-acid (HClO4 + HNO3, 3:10) digestion, using analytical grade reagents including conc. nitric acid (HNO3) and perchloric acid (HClO4). One gram of dried and finely ground seed samples was taken into a 100 ml of Erlenmeyer flask to which 10 ml of conc. HNO3 was added and was kept for 8 h for pre-digestion. After pre-digestion, 10 ml of HNO3 and 3 ml of HClO4 were added. Erlenmeyer flask was then placed on a hot plate in the digestion chamber where it was heated to 100 °C for 1 h and was then raised to 200 °C. Digestion was continued till the appearance of a clear colourless solution. After cooling, the volume was made up to 100 ml with double distilled water and was stored in polypropylene bottles for mineral estimation through atomic absorption spectrophotometer with air-acetylene flame (Model AAnalyst 400; PerkinElmer Corp., USA), at their corresponding wavelengths for estimation.

Lipid peroxidation

Lipid peroxidation was determined in leaf samples as the malondialdehyde (MDA) content (Heath and Packer 1968). Leaves (100 mg) were homogenized in 2 mL 0.1% (w/v) Trichloroacetic acid (TCA) solution. The homogenate was centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 20 min and 0.25 mL of the supernatant was added to 1.75 mL 0.5% (w/v) thiobarbituric acid (TBA) in 20% TCA. The mixture was heated at 95 °C for 20 min and immediately cooled in an ice bath. The samples were then centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 5 min. The absorbance was recorded at 532 nm. The value for non-specific absorption at 600 nm was subtracted. The amount of MDA–TBA complex (red pigment) was calculated from the extinction coefficient as 155 m M−1 cm−1.

Antioxidant enzyme activity

Ascorbate peroxidase (APX) (EC 1.11.1.11) was assayed by recording the decrease in optical density due to ascorbic acid at 290 nm (Nakano and Asada 1981). The reaction mixture (3 mL) contained 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0), 0.5 mM ascorbic acid, 0.1 mM EDTA, 0.1 mM H2O2, 0.1 mL enzyme, and water to make a final volume of 3.0 mL in which 0.1 mL of H2O2 was added to initiate the reaction. A decrease in the absorbance was measured spectrophotometrically and the activity was expressed by calculating the decrease in ascorbic acid content using a standard curve drawn with known concentrations of ascorbic acid.

Peroxidase (POX) (EC 1.11.1.7) activity was measured in terms of an increase in absorbance due to the formation of tetra-guaiacol at 470 nm and the enzyme activity was calculated as per the extinction coefficient of its oxidation product, tetra-guaiacol e = 26.6 m M−1 cm−1 (Castillo et al. 1984). The reaction mixture contained 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 6.1), 16 mM guaiacol, 2 mM H2O2, 0.025 mL enzyme extract, and distilled water to make up the final volume of 2.5 mL. Enzyme activity was expressed as mmol tetra guaiacol formed per min per mg protein.

Profiling of phenolics using Ion chromatograph

Extraction of Phenolic compounds from seed samples

One gram of seeds was kept in 80% HPLC grade methanol in screw cap glass tubes at 4 ℃ for 48 h. The extraction was done using mortar and pestle and the extractant was centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 10 min, which was repeated four times and the supernatant was collected in a volumetric flask and the final volume was made up to 25 mL with 80% methanol. The residue of the supernatant was obtained by evaporating them to dryness under a vacuum dryer at 50 ℃ which was then dissolved in 1 mL mobile phase (Mahatma et al. 2019).

The filtration of extracted phenolics (25 µl) was done using a nylon filter (25 mm × 0.45 µm) and the filtrate was injected in the Ion chromatograph (Dionex, ICS 3000). Acclaim 120 C 18 reverse phase column (5 µm, 4.6 × 250 mm) was used to separate the phenolics. Acetonitrile and acetic acid (2% v/v) were used as gradient mobile phase with a flow rate of 0.5 ml−1 min−1 and the temperature of the column was maintained at 30℃. The detection of the phenolics was done through UV detector at 280 nm. The standards for different components of phenolics were procured from Sigma-Aldrich. Based on their retention time, the identification of different phenolic compounds was done as standardized for peanut seed samples and the chromatogram was obtained.

Yield attributes

The plants were harvested at maturity and upon proper curing, the pods were collected for recording vital yield attributes namely hundred kernel weight (HKW), number of mature pods per 3 plants (NPP) and pod yield (PY).

qRT- PCR for gene expression

In order to look into the expression of genes regulating Fe uptake through the root under Fe-deprived soil conditions, total RNA was extracted from frozen peanut root tissues using RNeasy Plant mini kit (Qiagen, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. RNA was quantified using Nano-spectrophotometer (Nabi, Korea) and quality was checked using agarose gel electrophoresis. Total RNA (1 μg) was used as a template and cDNA was synthesized using QuanTect Reverse Transcription kit (Qiagen, USA). The cDNAs were diluted 1:4 with RNase-free sterile water and used as a template in the qPCR reaction. The qPCR was performed in 20 μL reaction volume which include 2 μL of diluted cDNA, 10 μL 2X QuantiFast SYBR Green PCR master mix (QIAGEN, USA), 10 pmol forward and reverse primers each, and the final volume was adjusted with sterile nuclease-free water. The qPCR was performed on 96 well qTOWER 3G (Analytic jena, Germany) with 3 step cycling conditions: 5 min at 95 °C to completely denature cDNAs, followed by 40 cycles of 15 s at 95 °C and 15 s at 60 °C. To normalize the variance between the samples, actin was used as an endogenous control for analysis of gene expression, and 2−ΔΔCT (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001)) method was used for data analysis. The primer sequence for studying the gene expression of Fe transporters namely NRAMP3, IRT 1, ZIP 5 and YSL 3 were taken from Chen et al. (2019) (Supplementary Table 1).

Statistical analysis

The pooled analysis of variance for VCR rating, SCMR, and pod yield component traits was performed for 42 advanced peanut breeding lines for 2 years (2018 and 2019) using the mixed and general linear model procedures of SAS (Supplementary Table 2). Means separation was done using Fisher’s protected least significant difference (LSD) at 0.05 level of significance. A total of 42 groundnut cultivars were classified based on K means clustering as per Macqueen (1967) and Forgy (1965) using R studio.

The analysis of variance and multiple comparison tests of all the screened genotypes were performed using the doebioresearch package of R studio from the pooled value of three replications during Kharif 2020 and 2021 with error bars on graphs representing the standard deviation in replications. The data for phenolics profiling and relative expression of transporters were analysed and the least significant difference was calculated using the agricolae package of R studio. All the graphs were prepared using the ggplot2 package of R studio. The ABLs and checks represented in the bar plot having the same letter (s) did not differ significantly from each other. The variable principal component analysis was performed using FactoExtra and FactorMiner package and biplot was made using ggplot2 of R studio.

Result

Field screening of advanced breeding lines with checks

There was wide variability among the ABLs of peanuts pertaining to VCR, SCMR, and yield responses (Supplementary Table 3). The Visual chlorotic symptoms started appearing in the leaves at an early growth stage of 35–40 DAS during the four years of field screening. NRCG 7472 (susceptible check) and PBS 12185 scored 4 on the VCR scale (1–5) at this stage and were easily observed as the most yellow lines in the field while PBS 12215 scored 3. At 50 DAS, a few lines having moderate interveinal chlorosis (PBS 29218, 12,029, 15,017, 25,074, 25,087 and 3001) showed some degree of recovery but three lines PBS 12185, 12,215 and NRCG 7472 recorded severe chlorosis in the entire leaves. The genotypes PBS 12185, 12,215 and NRCG 7472 were found to be highly chlorotic with a papery white appearance of leaves along with necrotic patches (VCR score 4–5) at 80 DAS. However, PBS 22040, 19,015, 12,200, 22,050, 22,058, 22,130, 29,192, and ICGV 86031 recorded minimum pigment loss showing green leaves at all the stages of growth. The SCMR was employed for estimating the chlorophyll retention in leaves of the ABLs during Fe- deficit conditions in the soil. The SCMR values (< 30) were recorded in PBS lines 13,020 (29.18), 12,215 (29.23), 12,185 (28.85), and NRCG 7472 (25.85) indicating maximum depigmentation while the SCMR values (> 40) were recorded in PBS 22040 (43.08), 22,058 (40.10), 29,192 (42.08), and ICGV 86031(42.11). The number of pods per 3 plants (NPP) and hundred kernel weight (HKW) recorded maximum values for PBS 22040 and 29,192 along with the tolerant check, ICGV 86031. Considering the performance of all the ABLs during the consecutive years of field screening, PBS 22040 and 29,192 were selected as the lines having a high degree of IDC tolerance (Fig. 1) while PBS 12185 and PBS 12215 were highly susceptible lines when compared to ICGV 86031 and NRCG 7472 as the tolerant and susceptible checks, respectively.

Fig. 1.

IDC susceptible lines (first column: PBS 12185 and PBS 12215) and IDC tolerant lines (second column: PBS 22040 and PBS 29192) based on their VCR score at 80 DAS

Figure 2 represents the K means clustering of the genotypes wherein the two extremes represent the high degree of tolerance (green) and susceptibility (purple) for IDC, respectively. Four clusters were formed based on the screening parameters VCR, SCMR, and yield traits wherein PBS 22040, 19,015, 29,192 and ICGV 86031 formed the cluster 2 (green) with minimum VCR values (1–1.25), maximum SCMR (36–43) and yield (NPP: 40–57; HKW: 49–54 g) while PBS 12185,12,215 and NRCG 7472 were the most susceptible lines forming cluster 4 (purple) recording maximum VCR (4–5); lowest SCMR (26–29) and yield (NPP: 27–28; HKW: 31–35 g). Clusters 1 (red) and 3 (blue) represented the medium performing ABLs with their VCR ranging to the tune of 2.3–3.5 and 1.2–2.4 respectively while their SCMR ranged from 32 to 38 and 33- 40 for clusters 1 and 3 respectively, with the yield traits showing almost at par performance.

Fig. 2.

K means clustering representing the extreme expressions of susceptible and tolerant ABLs based on field screening parameters

Physiological and biochemical strategies to acquire IDC tolerance in peanut ABLs

Chlorophyll and carotenoid content in leaves

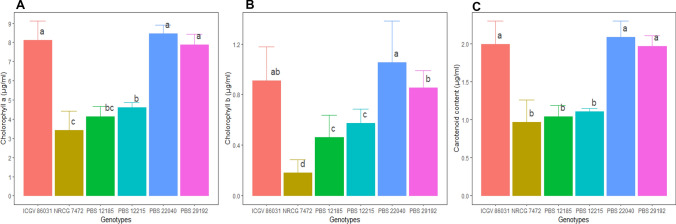

The contrasting ABLs represented significant differences in the pigment content in their leaves with the tolerant lines having their Chl a (Fig. 3A) and b (Fig. 3B) content above 8.15 µg ml−1 (range 7.84–8.45 µg ml−1) and 0.94 µg ml−1 (0.85–1.05 µg ml−1) respectively; while the susceptible lines exhibited the Chl a and Chl b values below 4.04 µg ml−1 (range 3.46–4.60 µg ml−1) and 0.40 µg ml−1 (0.18–0.57 µg ml−1) respectively. Similarly, carotenoid content (Fig. 3C) showed a significantly higher accumulation under Fe- deprived conditions in tolerant lines with PBS 22040 recording the maximum value (2.09 µg ml−1) followed by ICGV 86031 (1.99 µg ml−1) and PBS 29192 (1.97 µg ml−1) with respect to susceptible lines.

Fig. 3.

Chlorophyll a (3A), b (3B) and carotenoid (3C) content (µg ml−1) in leaves of 6 ABLs. The barplot indicated the mean value (n = 6) from pooled value of the experimental years 2020 and 2021, the error bar indicates ± values of standard deviation and the alphabet above the bar denotes the least significant difference between genotypes i.e. mean having the same letter are not significantly different

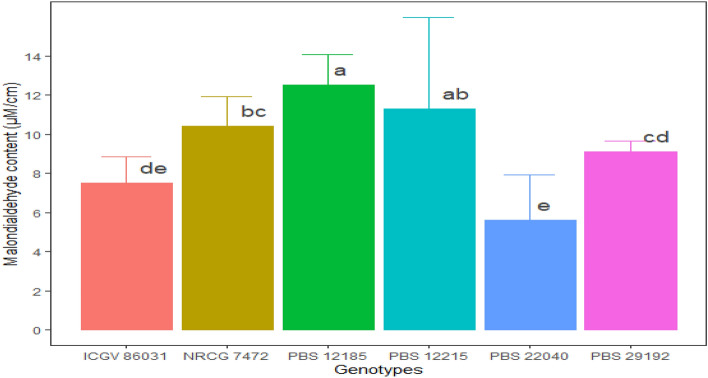

Lipid peroxidation and antioxidant enzyme activities

Minimum lipid peroxidation was recorded for PBS 22040 with the least MDA content (5.61 µM cm−1) followed by ICGV 86031 (7.49 µM cm−1) while PBS 29192 recorded a slightly higher the MDA content (9.11 µM cm−1). Among the susceptible lines, MDA content of both PBS 12185 (12.54 µM cm−1) and 12,215 (11.29 µM cm−1) indicated greater lipid peroxidation as compared to the susceptible check, NRCG 7472 (10.42 µM cm−1) (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Malondialdehyde (MDA content) (µM cm−1) in leaves of IDC tolerant and susceptible ABLs. (The figure indicates the mean value (n = 6) from pooled value of the experimental years 2020 and 2021, the error bar indicates ± values of standard deviation and the alphabet above bar denotes the least significant difference between genotypes i.e., mean having the same letters are not significantly different)

APX (Fig. 5A) recorded significantly higher activity in the PBS 22040 (103.9%), 29,192 (39.84%), and ICGV 86031 (35.9%), while PBS 12215 and 12,185 recorded 4.47% higher APX activity in response to Fe deficiency, as compared to the susceptible check NRCG 7472. However, the POX activity (Fig. 5B) was significantly expressed in all the lines but the activity in tolerant lines was further enhanced (51- 145%) over the susceptible lines (23- 35%), when compared to NRCG 7472), the susceptible check.

Fig. 5.

Effect of Fe deprivation on ascorbate peroxidase (5A) and peroxidase (5B) activities in leaves of tolerant and susceptible genotypes. The barplot indicated the mean value (n = 6) from pooled value of experimental years 2020 and 2021, error bar indicates ± values of standard deviation and alphabets above bar denotes least significant difference between genotypes i.e. mean having a same letter are not significantly different

Figure 6 represents the differential response of tolerant and susceptible lines wherein Fe deprivation in tolerant lines increased the POX activity, carotenoid and chlorophyll accumulation all of which occupy the same quadrant and these contribute to reduced MDA accumulation, contrary to that of susceptible lines which recorded elevation in MDA accumulation due to reduced pigment retention and antioxidant activity.

Fig. 6.

Differential expression of tolerant and susceptible lines for vital traits influenced under Fe deprivation; APX, MDA, Tch, Car, POX represent ascorbate peroxidase activity, malondialdehyde, total chlorophyll, carotenoid content and peroxidase enzyme activity, respectively)

Status of seed phenolics under Fe deprivation

The profiling of phenolics (Fig. 7) is represented through the chromatogram wherein the peaks of various phenolic compounds were observed at their specific retention time with reference to the standard. A significant increase in resveratrol content (44–61%) in the seeds of tolerant lines (PBS 22040 and PBS 29192) when compared with the susceptible check (NRCG 7472) was recorded. Similarly, ferulic acid content indicated a significantly higher accumulation in the seeds of tolerant lines PBS 22040 (378.6 ppm) and 29,192 (337.6 ppm) with respect to NRCG 7472 (124.4 ppm).

Fig. 7.

Chromatogram of profiling of phenolics using Ion chromatograph (Dionex ICS 3000). Acclaim 120 C 18 reverse phase column (5 µm, 4.6 × 250 mm) was used to separate the phenolics

The other phenolics including catechol, chlorogenic acid, caffeic acid, and syringic acid showed variable responses in different lines (Table 2). PBS 29192 accumulated maximum chlorogenic (94.4 ppm), caffeic (81.8 ppm) and syringic acid (846.4 ppm) with respect to the susceptible check (NRCG 7472).

Table 2.

Phenolics status of IDC tolerant lines with respect to NRCG 7472 (susceptible check)

| Genotypes | Chlorogenic acid | Catechol | Caffeic acid | Syringic acid | Ferulic acid | Resveratrol |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PBS29192 | 94.30a | 27.01b | 81.76a | 846.43a | 337.57b | 5.20a |

| NRCG7472 | 60.19c | 30.77a | 78.20b | 838.43b | 124.40c | 3.57b |

| PBS22040 | 68.57b | 31.21a | 75.63c | 773.20c | 378.60a | 5.80a |

| LSD (p < 0.001) | 0.82 | 1.85 | 1.65 | 0.73 | 1.24 | 0.76 |

Data expressed as mean values of three replicates, means having same letters are not significantly different using LSD test

Transporters for Fe uptake at root plasma membrane (PM)

The qRT-PCR study revealed that PBS 22040 recorded an overexpression of transporters ZIP5 (3.70 folds), IRT1 (2.30 folds) and YSL3 (2.20 folds) while PBS 29192 recorded overexpression of IRT1 (9.45 folds), YSL3 (2.32 folds), NRAMP3 (1.52 folds) and ZIP5 (1.45-folds) respectively in the periplasmic membrane of roots over the susceptible check NRCG 7472 (supplementary Fig. 1). There was no significant overexpression of the transporters at root PM of the tolerant check ICGV 86031 over NRCG 7472.

Micronutrient status of the seeds of tolerant and susceptible lines

The accumulation of Zn and Fe in the seeds of peanut genotypes (Fig. 8) recorded distinct variation with PBS 22040 indicating maximum seed Fe content (45.59 ppm) (Fig. 8A) while highest seed Zn content (35 ppm) was observed in ICGV 86031 (Fig. 8B).

Fig. 8.

Fe (8A) and Zn (8B) content (ppm) in seeds of different genotypes. The barplot indicated the mean value (n = 6) from pooled value of experimental years 2020 and 2021, error bar indicates ± values of standard deviation and alphabets above bar denotes least significant difference between genotypes i.e. mean having a same letter are not significantly different

Among the six genotypes, PBS 22040, 29,192 and ICGV 86031 recorded higher seed Fe (> 40 ppm) and Zn (> 30 ppm) accumulation while the other three genotypes (PBS 12185, 12,215, and NRCG 7472) recorded Fe and Zn content in the range of 25–29 ppm and 23- 29 ppm, respectively. Zn being more phloem mobile gets readily remobilized resulting in a narrow difference in seed Zn content of tolerant and susceptible lines.

Yield and yield attributes

PBS 22040 was the highest yielding line in terms of HKW (55 g), and NPP (55) while the HKW and NPP values for PBS 29192 were 51 g and 51 pods per 3 plants respectively (Supplementary Fig. 2). Maximum PY was recorded in PBS 22040 (282 g/ row) followed by ICGV 86031 (257 g/ row) and PBS 29192 (217 g/ row).

The supplementary Table 4 represents a summary of all the physiological, biochemical and yield attributes studied in the screened ABLs during Kharif 2020 and 2021.

Discussion

Identification of IDC tolerant lines through field screening

The VCR and SCMR are reportedly the two widely known screening parameters for the evaluation of IDC responses in the field (Singh et al. 2004). It is suggested that the susceptible lines tend to have higher VCR and lower SCMR while the tolerance to IDC corresponds to higher SCMR values, lower VCR score and superior yield attributes (Samdur et al. 1999). The identified IDC tolerant lines (PBS 22040 and PBS 29192) in this study exhibit similar attributes indicating a higher degree of tolerance to Fe deprived soil conditions.

Physiological, biochemical, and molecular response of IDC tolerant and susceptible lines to Fe deprived conditions

The visual chlorotic appearance of leaves under Fe deprivation is reportedly correlated to the deficiency of chlorophyll and carotenoid content in a number of crops including maize (Sun et al. 2007), Chinese cabbage (Ding et al. 2009) and peanuts (Kong et al. 2014). The pivotal role of Fe in chlorophyll biosynthesis can be ascribed to the formation of the precursors namely δ-aminolevulinic acid and protochlorophyllide (Kong et al. 2014). Thus, greater retention of chlorophyll and carotenoid during Fe limited soil conditions is an integral attribute of IDC tolerance.

The Fe deprivation reportedly generates reactive oxygen species (ROS) due to which there occurs enhanced accumulation of MDA (Kong et al. 2016) and is considered a vital indicator of membrane sensitivity to nutrient deficiency (Oustric et al. 2021). Greater membrane damage to the susceptible ABLs can be attributed to the enhanced lipid peroxidation under Fe deficit conditions due to the encounter of membrane lipids with free radicals. The free radicals cause the decomposition of polyunsaturated fatty acids of the membrane with malondialdehyde (MDA) as the end product (Sperotto et al. 2008). The accumulation of MDA due to ROS generation elicits a signal for the activation of antioxidant enzymes so as to protect the biological membranes from oxidative injury (Asada 1999). The Fe containing antioxidant enzymes, APX and POX, are the indicators, differentiating the tolerant and susceptible genotypes under Fe deficiency (Dasgan et al. 2003). The differential expression of APX activity in sensitive and tolerant lines can be attributed to the greater requirement of physiologically available Fe for its optimum activity (Ranieri et al. 2001; Santos et al. 2019). POX activity was significantly expressed in all the PBS lines with a higher percentage increase in tolerant lines which can be ascribed to the variable expression of different isoforms of POX all of which may not have a haem group which requires Fe for their functioning (Watanabe et al. 2016).

Peanuts reportedly contain rare phenolics namely ferulic acid (Yu et al. 2005) and resveratrol (Yang et al. 2009), which have recently gained attention owing to their immense health benefits (Toomer 2017). The stress condition reportedly elicits an increase in the synthesis and accumulation of resveratrol (Rudolf and Resurreccion 2006) and ferulic acid (Fajardo et al. 1995) but their elevated accumulation in peanut kernels during Fe deficiency has not yet been reported elsewhere. Zheng et al. (2021) reported the alleviation of IDC upon exogenous application of resveratrol. The increase in resveratrol and ferulic acid in seeds of tolerant lines could be attributed to the strong antioxidant capacity of these phenolics to enable the plant’s survival during stress circumventing the ROS by much more efficient scavenging.

The study reports greater Fe accumulation in seeds of IDC tolerant lines along with higher seed Zn accumulation. The Fe and Zn accumulation in seeds being positively correlated with each other, facilitate higher Zn uptake along with Fe (Singh et al. 2022) in tolerant genotypes. The lesser Fe accumulation in seeds of susceptible genotypes is ascribed to the restricted phloem mobility of Fe, which gets retained in the physiologically unavailable form in older leaves (Imensek et al. 2021). The Fe efficient genotypes of soybean also recorded similar results with higher seed Fe content when compared with inefficient genotypes (Vasconcelos and Grusak 2014). Furthermore, the regulatory genes namely NRAMP3, YSL3, IRT1 and ZIP5 have been identified in the root plasma membrane (PM) of peanut crop to mediate Fe/ Zn homeostasis during its deprivation in soil for plant uptake (Chen et al. 2019). The overexpression of these specific transporters at root PM in PBS 22040 and 29,192 might have contributed to the signalling of Fe deficiency to help the plant to strategize to circumvent the Fe-deprived state more efficiently than the susceptible ones.

The genotypes with superiority for any specific trait need to be accompanied by higher yields to be adopted by the farmers for ensuring optimal remuneration of their produce. PBS 22040 recorded the highest values for the yield attributes followed by ICGV 86031 and PBS 29192, over the susceptible lines, indicating the interplay of different component traits which aid in optimal plant performance. The superiority of yield traits in IDC tolerant lines have also been reported earlier in peanut (Boodi et al. 2016).

Conclusion

To realize the genetic yield potential of any cultivar in a given soil condition, it should be able to mine the required quantity of macro- and micro- nutrients. Peanut cultivated in medium black calcareous soil in the Saurashtra region of Gujarat suffers from Fe deficiency, a long-standing problem, causing a widespread occurrence of iron chlorosis affecting yield. Development of IDC tolerant genotypes being the best solution, we attempted to identify such sources of tolerance for further introgression in desired high yielding background. However, IDC tolerance is a complex trait comprising diverse and intertwined physiological, biochemical and molecular components which are activated upon Fe-deficiency in the soil. The study reports the identification of a novel genotype of peanut, PBS 22040- an advance breeding line, as a candidate genotype as a source of IDC tolerance. The over-expressive transporters and the new finding of accumulation of ferulic acid and resveratrol in seeds could be used as genetic and biochemical markers, respectively, for the identification of IDC tolerant lines from segregating populations and germplasm accessions. The identified IDC tolerant line, PBS 22040, offers the most pertinent solution for managing Fe deficiency induced chlorosis in peanut and for preventing yield losses due to the widespread occurrence of iron chlorosis. This genotype also offers a source of IDC tolerance for further exploitation to develop high-yielding IDC tolerant varieties of peanut.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the Director, ICAR- Directorate of Groundnut Research, Junagadh, Gujarat, for providing necessary facilities to conduct this study. The grants provided by the Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR) during the study is duly acknowledged.

Author’s contributions

SS: Conceptualized the research work, coordinated the field and laboratory observations, project supervision and drafted the manuscript; ALS: Supervision and editing of the final draft of MS; KKP and RD: supervision, review of research work and editing of manuscript; CBP and NK: Field observations and data validation for field screening; GK and KR: Fe and Zn estimation, data curation and validation and formal analysis; LT and RN; Ion chromatograph studies and data interpretation, SA: Gene expression studies; MKM and AV: Biochemical observations and manuscript editing; KR and PK: provided the genotypes, result interpretation and manuscript editing.

Funding

The authors declare that no funds, grants, or other support were received during the preparation of this manuscript.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Arnon DI. Copper enzymes in isolated chloroplasts polyphenoloxidase in Beta vulgaris. Plant Physiol. 1949;24:1–15. doi: 10.1104/pp.24.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asada K. The water-water cycle in chloroplasts: scavenging of active oxygen and dissipation of excess photons. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 1999;50:601–639. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.50.1.601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boodi IH, Pattanashetti SK, Biradar BD. Identification of groundnut genotypes resistant to iron deficiency chlorosis. Karnataka J Agric Sci. 2015;28(3):406–408. [Google Scholar]

- Boodi IH, Pattanashetti SK, Biradar BD, Naidu GK, Chimmad VP, Kanatti A, Kumar V, Debnath MK. Morpho-physiological parameters associated with Iron deficiency chlorosis resistance and their effect on yield and its related traits in groundnut. J Crop Sci Biotechol. 2016;19(2):177–187. doi: 10.1007/s12892-016-0005-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Castillo FI, Penel I, Greppin H. Peroxidase release induced by ozone in Sedum album leaves. Plant Physiol. 1984;74:846–851. doi: 10.1104/pp.74.4.846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C, Cao Q, Jiang Q, Li J, Yu R, Shi G. Comparative transcriptome analysis reveals gene network regulating cadmium uptake and translocation in peanut roots under iron deficiency. BMC Plant Biol. 2019;19:35. doi: 10.1186/s12870-019-1654-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dasgan HY, Ozturk L, Abak K, Cakmak I. Activities of Iron-containing enzymes in leaves of two tomato genotypes differing in their resistance to Fe chlorosis. J Plant Nutr. 2003;26:10–11. [Google Scholar]

- Ding H, Duan L, Wu H, Yang R, Ling H, Li WX, Zhang F. Regulation of AhFRO1, an Fe (III)-chelate reductase of peanut, during iron deficiency stress and intercropping with maize. Physiol Plantr. 2009;136(3):274–283. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3054.2009.01219.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fajardo JE, Waniska RD, Cuero RG, Pettit RE. Phenolic compounds in peanut seeds: enhanced elicitation by chitosan and effects on growth and aflatoxin B1 production by Aspergillus flavus. Food Biotechnol. 1995;9:59–78. doi: 10.1080/08905439509549885. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Forgy EW. Cluster analysis of multivariate data: efficiency vs interpretability of classifications. Biometrics. 1965;21:768–769. [Google Scholar]

- Geulein I. Antioxidant properties of resveratrol: a structure activity insight. Innov Food Sci Emerg Technol. 2010;11:210–218. doi: 10.1016/j.ifset.2009.07.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Heath RL, Packer L. Photoperoxidation in isolated chloroplast. I. Kinetics and stoichiometry of fatty acid peroxidation. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1968;125:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(68)90654-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiscox JD, Israelstam GF. A method for extraction of chloroplast from leaf tissue without maceration. Can J Bot. 1979;57:1332–1334. doi: 10.1139/b79-163. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Imenšek N, Sem V, Kolar M, Ivančič A, Kristl J. The Distribution of minerals in crucial plant parts of various elderberry (Sambucus spp.) interspecific hybrids. Plants. 2021;10:653. doi: 10.3390/plants10040653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irmak S, Cil AN, Yücel H, Kaya Z. The effects of iron application to soil and foliarly on agronomic properties and yield of peanut (Arachis hypogaea) J Food Agric Env. 2012;10(3/4):417–442. [Google Scholar]

- Kannan S. Genotypic differences in iron uptake utilization in some crop cultivars. J Plant Nutri. 1982;5:531–542. doi: 10.1080/01904168209362980. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kong J, Dong Y, Song Y, et al. Role of exogenous nitric oxide in alleviating iron deficiency stress of peanut seedlings (Arachis hypogaea L.) J Plant Growth Regul. 2016;35:31–43. doi: 10.1007/s00344-015-9504-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kong J, Dong Y, Xu L, Liu S, Bai X. Role of exogenous nitric oxide in alleviating iron deficiency-induced peanut chlorosis on calcareous soil. J Plant Interact. 2014;9(1):450–459. doi: 10.1080/17429145.2013.853327. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A, Kaur G, Singh P, Meena V, Sharma S, Tiwari M, Bauer P, Pandey AK. Strategies and bottlenecks in hexaploid wheat to mobilize soil iron to grains. Front Plant Sci. 2022;13:863849. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2022.863849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenthaler HK, Wellburn WR. Determination of total carotenoids and chlorophylls a and b of leaf extracts in different solvents. Biochem Soc Trans. 1983;11:591–592. doi: 10.1042/bst0110591. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2 (-Delta DeltaC (T)) Method Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Millan AF, Grusak MA, Abadia J. Carboxylate metabolism changes induced by Fe deficiency in Barley, a strategy II plant species. J Plant Physiol. 2012;169:1121–1124. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2012.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacQueen J (1967) Some methods for classification and analysis of multivariate observations. In: Le Cam LM, Neyman J (eds) Proceedings of the fifth Berkeley symposium on mathematical statistics and probability, 1:281–297. University of California Press, Berkeley

- Mahatma MK, Thawait LK, Jadon KS, Rathod KJ, Sodha KH, Bishi SK, Thirumalaisamy PP, Golakiya BA. Distinguish metabolic profiles and defense enzymes in Alternaria leaf blight resistant and susceptible genotypes of groundnut. Physiol Mol Biol Plants. 2019;25(6):1395–1405. doi: 10.1007/s12298-019-00708-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann A, Singh AL, Kumar A, Parvender OS, Goswami N, Chaudhari V, Patel CB, Zala PV. Exploiting genetic Variation for lime-induced iron-deficiency chlorosis in groundnut (Arachis hypogaea) Indian J Agric Sci. 2018;88(3):482–488. doi: 10.56093/ijas.v88i3.78732. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nakano Y, Asada K. Hydrogen peroxide is scavenged by ascorbate specific peroxidase in spinach chloroplasts. Plant Cell Physiol. 1981;22:867–880. [Google Scholar]

- Toomer OT. Nutritional chemistry of the peanut (Arachis hypogaea) Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2017 doi: 10.1080/10408398.2017.1339015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oustric J, Herbette S, Morillon R, Giannettini J, Berti L, Santini J. Influence of rootstock genotype and ploidy level on common clementine (Citrus clementina Hort. ex Tan) tolerance to nutrient deficiency. Front Plant Sci. 2021;12:634237. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2021.634237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pattanashetti SK, Pandey MK, Naidu GK, Vishwakarma MK, Singh OK, Shasidhar Y, Boodi IH, Biradar BD, Das RR, Rathore A, Varshney RK. Identification of quantitative trait loci associated with iron deficiency chlorosis resistance in groundnut (Arachis hypogaea) Plant Breed. 2020;139:790–803. doi: 10.1111/pbr.12815. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pattanashetti SK, Naidu GK, Prakyath KKV, Singh OK, Biradar BD. Identification of iron deficiency chlorosis tolerant sources from mini-core collection of groundnut (Arachis hypogaea L.) Plant Genet Resour. 2018 doi: 10.1017/S1479262117000326. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ranieri A, Castagna A, Baldan B, Soldatini GF. Iron deficiency differently affects peroxidase isoforms in sunflower. J Expt Bot. 2001;52(354):25–35. doi: 10.1093/jexbot/52.354.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rebecca TV, Benoit L, Seung YR, Laurent N, Hatem R. Mineral nutrient signaling controls photosynthesis: focus on iron deficiency-induced chlorosis. Trends Plant Sci. 2022 doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2021.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolf JL, Resurreccion AVA. Elicitation of resveratrol in peanut kernels by application of abiotic stresses. J Agric Food Chem. 2006;53:10186–10192. doi: 10.1021/jf0506737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samdur MY, Mathur RK, Manivel P, Singh AL, Bandyopadhyay A, Chikani BM. Screening of some advanced breeding lines of groundnut (Arachis hypogaea) for tolerance of lime-induced iron-deficiency chlorosis. Indian J Agric Sci. 1999;69(10):722–725. [Google Scholar]

- Samdur MY, Singh AL, Mathur RK, Manivel P, Chikani BM, Gor HK, Khan MA. Field evaluation of Chlorophyll meter for screening groundnut (Arachis hypogaea L.) genotypes tolerant of iron-deficiency chlorosis. Curr Sci. 2000;79(2):211–214. [Google Scholar]

- Santos CS, Ozgur R, Uzilday B, Turkan I, Roriz M, Rangel AOSS, Carvalho SMP, Vasconcelos MW. Understanding the role of the antioxidant system and the tetrapyrrole cycle in iron deficiency chlorosis. Plants. 2019;8(9):348. doi: 10.3390/plants8090348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt W, Thomine S, Buckhout TJ. Editorial: iron nutrition and interactions in plants. Front Plant Sci. 2020;10:1670. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2019.01670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh AL, Chaudhari V. Screening of groundnut germplasm collection and selection of genotypes tolerant to lime-induced iron chlorosis. J Agric Sci (camb) 1993;121:205–211. doi: 10.1017/S0021859600077078. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Singh AL, Basu MS, Singh NB. Mineral disorders of groundnut. Junagadh: National Research Center for groundnut (ICAR); 2004. p. 85. [Google Scholar]

- Sperotto RA, Boff T, Duarte GL, Fett JP. Increased senescence-associated gene expression and lipid peroxidation induced by iron efficiency in rice roots. Plant Cell Rep. 2008;27:183–195. doi: 10.1007/s00299-007-0432-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su Y, Zhang Z, Su G, Liu J, Liu C, Shi G. Genotypic differences in spectral and photosynthetic response of peanut to iron deficiency. J Plant Nutr. 2015;38(1):145–160. doi: 10.1080/01904167.2014.920392. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sun B, Jing Y, Chen K, Song L, Chen F, Zhang L. Protective effect of nitric oxide on iron deficiency-induced oxidative stress in maize (Zea mays) J Plant Physiol. 2007;164:536–543. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2006.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasconcelos MW, Grusak MA. Morpho-physiological parameters affecting iron deficiency chlorosis in soybean (Glycine max L.) Plant Soil. 2014;374:161–172. doi: 10.1007/s11104-013-1842-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Verma A, Mahatma MK, Thawait LK, Singh S, Gangadhar K, Kona P, Singh AL. Processing techniques alter resistant starch content, sugar profile and relative bioavailability of iron in groundnut (Arachis hypogaea L.) kernels. J Food Compos Anal. 2022;112:104653. doi: 10.1016/j.jfca.2022.104653. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe Y, Nakajima H. Creation of a thermally tolerant peroxidase. Methods Enzym. 2016;580:455–470. doi: 10.1016/bs.mie.2016.05.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J, Martinson TE, Liu RH. Phytochemical profiles and antioxidant activities of wine grapes. Food Chem. 2009;116:332–339. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2009.02.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yu J, Ahmedna M, Goktepe I. Effects of processing methods and extraction solvents on concentration and antioxidant activity of peanut skin phenolics. Food Chem. 2005;90:199–206. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2004.03.048. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng X, Chen H, Su Q, Wang C, Sha G, Ma C, Sun Z, Yang X, Li X, Tian Y. Resveratrol improves the iron deficiency adaptation of Malus baccata seedlings by regulating iron absorption. BMC Plant Biol. 2021;21(1):433. doi: 10.1186/s12870-021-03215-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X, Ren X, Luo H, Huang L, Liu N, Chen W, Lei Y, Liao B, Jiang H. Safe conservation and utilization of peanut germplasm resources in the oil crops Middle-term Genebank of China. Oil Crop Sci. 2022;7(1):9–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ocsci.2021.12.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.