Abstract

Engineered nickel oxide nanoparticle (NiO-NP) can inflict significant damages on exposed plants, even though very little is known about the modus operandi. The present study investigated effects of NiO-NP on the crucial stress alleviation mechanism Ascorbate-Glutathione Cycle (Asa-GSH cycle) in the model plant Allium cepa. Cellular contents of reduced glutathione (GSH) and oxidised glutathione (GSSG), was disturbed upon NiO-NP exposure. The ratio of GSH to GSSG changed from 20:1 in NC to 4:1 in roots exposed to 125 mg L−1 NiO-NP. Even the lowest treatments of NiO-NP (10 mg L−1) increased ascorbic acid (2.9-folds) and cysteine contents (1.6-folds). Enzymes like glutathione reductase, ascorbate peroxidase, glutathione peroxidase and glutathione–S-transferase also showed altered activities in the affected tissues. Further, intracellular methylglyoxal, a harbinger of ROS (Reactive oxygen species), increased significantly (~ 26 to 65-fold) across different concentrations NiO-NP. Intracellular H2O2 (hydrogen peroxide) and ROS levels increased with NiO-NP doses, as did electrolytic leakage from damaged cells. The present work indicated that multiple pathways were compromised in NiO-NP affected plants and this information can bolster our general understanding of the actual mechanism of its toxicity on living cells, and help formulate strategies to thwart ecological pollution.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s12298-023-01314-8.

Keywords: Antioxidants, Engineered nanoparticle hazard, Environmental pollutant, GSH:GSSG ratio, Methylglyoxal, Reduced glutathione, ROS

Introduction

Engineered metallic nanoparticles are often manufactured for specific purposes, their uniform shapes, external coatings, or internal shells, distinguish them from their natural counterparts. These engineered nanoparticles thus have unique chemical and physical characteristics and can most often outcompete their natural cohorts, especially when binding with metal-dependent proteins, in living systems (Cameron et al. 2022). Nickel oxide nanoparticle (NiO-NP) was already under scientific scrutiny, since their uses in electronics and consumer goods industry became popular in the last few decades, because of their electrical conductivity and ferromagnetic properties (Tan et al. 2019). NiO-NP can act as a cyto-genotoxic agent, and even at low concentrations was shown to be interrupting ROS homeostasis by destroying the antioxidant framework of plant cells, interfering with membrane and organellar integrity, and causing extensive damage to nucleus, affecting genomic DNA stability (Manna and Bandyopadhyay 2017a, b).

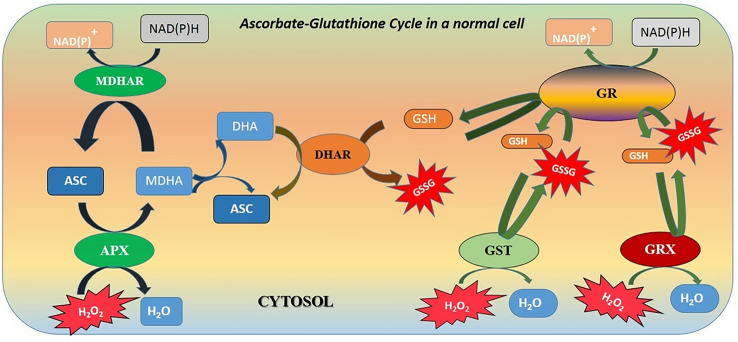

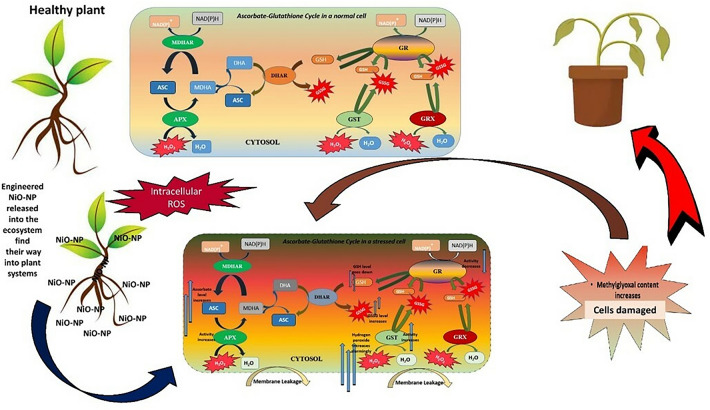

The ascorbate-glutathione cycle (Asa-GSH cycle) (Fig. 1) is a major, if not the most important, mechanism of stress amelioration in any living system (Jozefczak et al. 2012). Reduced glutathione- (GSH), a thiol tripeptide, upholds the integrity of a cell by balancing homeostasis between the cellular ROS network and other cellular mechanisms of signalling, growth and development. Evolution of the GSH cycle is a major adaptive advancement that cells attained to survive the hostile oxidative environment billions of years ago, when disintegration of ROS became imperative for the cell’s survival (Mittler et al. 2011). Both plants and animals share great similarity in their respective glutathione cycles, which links the gap between oxidative and reduced species by a thiol-disulphide reaction mediated through NADPH-dependent Glutathione Reductase (GR), and run the two-way cascade of formation of disulphide glutathione (GSSG) (Noctor et al. 2012). ROS in optimum quantity plays an important role in signal transduction within a cell (Berni et al. 2019) and GSH keeps ROS within the functional range by converting into GSSG in turn. For conversion of H2O2 into water, ascorbate peroxidase (APx) is the electron donor (Meyer 2008). At the penultimate step, GSSG converts back to GSH via electrons sourced from NADPH using Glutathione Reductase (GR) (Meyer 2008). Hence, there are two supply chains for GSH, viz., reduction of GSSG and the de novo synthesis of GSH, whose turnover is slower (Meyer and Fricker 2002). Under stress, de novo synthesis steps-up but conversion of GSSG to GSH slows down, which negatively influence the electron flow creating a deficit of 2 electrons and causing removal of excess ROS from the cell. The ratio of GSH and GSSG is thus an important marker depicting the health of a cell (Jones 2002). In lower eukaryotes like yeast, changes in GSH/GSSG ratio are directly correlated to cell growth and apoptosis (Schafer and Buettner 2001).

Fig. 1.

Generalized view of ascorbate-glutathione (Asa-GSH) cycle (modified from Noctor et al. 2012; without using any original image or idea subjected to copyright; ASC-Ascorbate; MDHA-Monodehydroascorbaste; DHA-Dehydroascorbate; MDHAR-Monodehydroascorbate reductase; APX-Ascorbate peroxidase; DHAR-Dehydroascorbate reductase; GRX-Glutaredoxins; NAD(P)+/NAD(P)H-Nicotinamide-adenine dinucleotide phosphate

The authors have earlier reported that NiO-NP cause massive cyto- and geno-toxicity in treated plants through oxidative burst mechanism where excess ROS damaged cells severely. In this study, the authors have shown how NiO-NP handicapped the Asa-GSH cycle homeostasis in the test system, Allium cepa. The authors hypothesised that NiO-NP would alter the GSH/GSSH ratio. Important enzymes of Asa-GSH cycle namely, glutathione reductase (GR), glutathione transferase (GST), glutathione peroxidase (GPx), ascorbate peroxidase (APX), along with reduced glutathione (GR) and oxidised glutathione (GSSG) were quantitated to understand the changes in the GSH/GSSH ratio upon NiO-NP exposure, while perturbations in the levels of non-enzymatic stress markers, cysteine and ascorbate, as well as, the cellular markers of ROS and cytotoxicity, viz., relative electrolyte leakage, hydrogen peroxide and methylglyoxal, were calibrated to show how NiO-NP impaired cellular mechanism. The present work present a unique representation, since there are no reports on the effect of ENPs on Asa-GSH cycle in plants to the best of authors knowledge. Therefore to validate the present body of work, comparisons were drawn from evidences of bulk heavy metals’ interactions with plants and from other ENP’s interaction where ever such an instance was found.

Material and methods

Nanoparticle procurement

Nickel oxide nanoparticle was obtained from Sigma Aldrich, (St. Louis, USA) [Product code 637,130, Molecular weight: 74.69, EC Number: 215-215-7, Pubchem Substance ID 24,882,831, < 50 nm particle size (TEM), 99.8% trace metal basis]. Detailed characterization of NiO-NP using TEM, DLS and Zetasizer confirming their size, hydrodynamic properties and stability in aqueous solution has already been reported by the authors previously (Manna and Bandyopadhyay 2017a, b; Manna et al. 2022).

Plant growth and treatment conditions

Bulbs of Allium cepa (var. Nasik Red), of uniform sizes were collected, and kept on wet, sterilised sand beds, in dark at 23 ± 2 °C in a growth chamber under controlled moisture for root induction. Seven-day old bulbs showing consistent rooting were treated with different doses of NiO-NP (viz. 10, 25, 50, 62.5, 125, 250 and 500 mg L−1 NiO-NP) as hydroponic suspensions following protocol reported earlier (Manna and Bandyopadhyay 2017a, b) for 24 h. A (NC) consisting of bulbs exposed to only double distilled ultrapure water and a positive control treated with aqueous solution of 0.4 mM EMS (Ethyl methane sulphonate) in DD water were also maintained for the same time periods under similar conditions in triplicate. All the treatment sets along with the controls were maintained at ambient temperature (20 °C) throughout the period of treatment. After treatment for 24 h, fresh tissues were harvested and used immediately for various experiments as documented below. All the experiments were done at least thrice to check the authenticity of results.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) of root tips

Apical root tips (~ 5 mm) were cut and fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde and 2% paraformaldehyde in phosphate buffer as per to standard protocol (Pathan et al. 2010), followed by series of graded ethanol dehydration. Later, dehydrated root tips fixed on two-sided carbon tape were visualised under accelerating voltage of 10 kV in a Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) (Zeiss Evo-MA 10).

Detection of relative electrolyte leakage

Integrity of the cell membrane was analysed through relative electrolyte leakage assay following Halder et al. (2017). In short, freshly excised roots from various treatments and the control sets were thoroughly rinsed with DD water, followed by incubation in 15 ml of fresh DD water for 4 h at 25 °C. Roots from NC sets served as control against which electrolyte leakage (R1) were measured using a conductivity meter (Eutech C700, Singapore). The root samples were then autoclaved at 15 psi for 15 min and electrolyte leakage was remeasured (R2). Relative electrolyte leakage was deduced as (R1/R2) × 100.

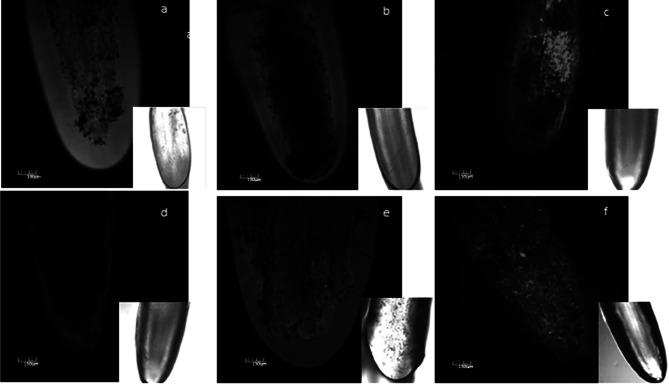

Fluorescent staining of roots to detect presence of thiol and concurrent increase in intracellular H2O2 and ROS

Roots from the control and treated sets were subjected to staining with monochlorobimane, which specifically forms fluorescing adducts with lower group of thiols like GSH. Root tips were incubated in 0.25 μM solution of monochlorobimane in PBS for 30 min at room temperature, and after thorough washings in PBS, were photographed under a Laser Scanning Confocal Microscope (LSCM- Olympus, 1X CLSM 81) using software version: Fluoview FVV 1000 with the 394–430 filter (Das et al. 2018).

Quantification of intracellular methylglyoxal

Methylglyoxal (MG) was quantified following the protocol of Yadav et al. (2005) with minor modifications. 500 mg tissue was homogenized in 0.5 M perchloric acid. After incubation on ice, the mixture was centrifuged at 4 °C for 15 min at 10,000 g. The supernatant was decolorized by adding charcoal and centrifuged again, and then neutralized with saturated solution of potassium carbonate at room temperature before centrifugation for 15 min. For detection of MG, a total 1 ml reaction mix was made by adding 250 µL of 7.2 mM 1, 2- diaminobenzene, 100 µL of 5 M perchloric acid and 650 µL of the neutralized supernatant, which was incubated for 30 min. This reaction mixture was spectrophotometrically analysed at 335 nm. The final concentration was calculated from the standard curve and expressed in terms of nmol g−1 FW.

Biochemical assays of substrates of Asa-GSH cycle

Reduced glutathione (GSH)

Total reduced glutathione content from both the control and treated sets was estimated following the protocol of Sedlak and Lindsay (1968) with necessary modifications. In short, samples were extracted in 5% (w/v) sulphosalicylic acid (SSA) containing 1 mM ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid disodium salt (Na2EDTA), and centrifuged at 10,000 g for 20 min. Reduced glutathione was measured in a test mixture containing 100 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.5), 1 mM Na2EDTA, 6 U cm−3 Glutathione Reductase (GR), 10 mM 5,5’-dithiobis-(2-nitrobenzoic acid) (DTNB) and 0.16 mg cm−3 NADPH. Absorbance was recorded at 412 nm using a 96-well micro plate reader (Biorad iMark™).

Oxidised glutathione (GSSG)

Measurement of oxidised glutathione was done using the same extract as above following the protocol of Rahman et al. (2006). To 100 μl of cell extract, 2 μl of 2-vinylpyridine was added and incubated for 60 min following which the same protocol for GSH quantification was applied to measure GSSG from a standard curve.

Assays of intermediates enzymes

Glutathione reductase (GR)

Roots were crushed in 100 mM phosphate buffer and centrifuged at 10,000 g for 30 min at 4 °C, and the recovered supernatant was used for this assay. GR (EC 1.6.4.2) activity was assayed as per Das et al. (2018) using 100 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.5) with 0.5 mM Na2EDTA, 0.75 mM DTNB, 0.1 mM NADPH, and 1 mM oxidized glutathione (Smith et al. 1989). After 30 min of incubation at room temperature, the absorbance was read at 412 nm at an interval of 30 s for up to 5 min. GR activity was calculated using the coefficient of absorbance (ε) of 6.22 mM−1 cm−1.

Glutathione transferase (GST)

For this assay, root samples were crushed in 100 mM Tris–HCl buffer (pH 7.5) containing 2 mM Na2 EDTA, 14 mM β-mercaptoethanol and 7.5% (w/v) polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) followed by centrifugation at 10,000 g for 30 min. The resulting supernatant was used for detecting the activity of GST (EC 2.5.1.18) in 100 mM phosphate buffer (pH 6.5) containing 5 mM GSH, and 1 mM 1-chloro-2,4-dinitrobenzene and read at 340 nm. The activity of GST was calculated using ε = 9.6 mM−1 cm−1 (Ando et al. 1988).

Glutathione peroxidase (GPx)

GPx (EC 1.11.1.9) estimation was done according to Das et al. (2018), with slight modifications. 100 mg tissue was homogenised in 2 M Tris–HCL buffer containing 0.25 M sucrose and 50 mM KCl, 1 mM magnesium chloride, 160 mM β-mercaptoethanol, and 0.75 mM phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride and centrifuged at 10,000 g for 30 min. Enzyme activity was measured in a reaction mix containing 20 mM sodium acetate buffer and 30 mM H2O2 and 2 mM guaiacol, added prior to scan. Absorbance was measured at 470 nm and extinction coefficient ε = 26.6 mM−1 cm−1 was used for calculating the content of the enzyme according to Ranieri et al. (2001).

Ascorbate peroxidase (APx)

APx (EC 1.11. 1.11) activity was calculated according to Nakano and Asada (1981) with few changes. Roots from all the sets were crushed in 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) containing 10% PVP, centrifuged at 10,000 g for 30 min and the supernatant was used for further studies. Reaction mixture consisted of 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0), 0.5 mM ascorbic acid, 0.1 mM EDTA, and 100 μL enzyme extract with 0.1 mM H2O2 added just prior to estimation. The change in absorbance at 290 nm was recorded for every 30 s for 3 min. APx activity was further, calculated using extinction coefficient of 2.8 mM−1 cm−1 for ascorbate oxidized at 290 nm and expressed as nmol ascorbic acid decomposed ml−1 protein min−1.

Assessment of non-enzymatic stress markers

Detection of Cysteine

Cysteine was detected in 100 mg of root samples, homogenized in 5% (v/v) chilled perchloric acid (PCA), which was centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C (Genisel et al. 2015). The absorbance of the supernatant was found with acid-ninhydrin reagent at 560 nm following the protocol of Gaitonde (1967) with minute modifications (Das et al. 2018).

Detection of ascorbate

For assessment of ascorbate contents, root tissues were crushed in ice-cold 6% TCA and centrifuged at 10,000 g for 30 min at 4 °C, and the supernatant was used for further analyses (Mukherjee and Chaudhuri 1983). Reaction mixture was made by following Das et al. (2018) with modifications, consisting of the supernatant, 0.2% DNPH (2’, 4’-Dinitrophenylhydrazine) in 0.5 N HCl, 0.01 ml 10% thiourea in 70% ethanol. It was kept in boiling water for 15 min, cooled and concentrated H2SO4 was added. Absorbance was checked at 530 nm and ascorbate quantified from a previously made standard curve was of ascorbic acid. Ascorbate contents were expressed as nmol g−1 FW.

Statistical analyses

The statistical analyses were done using SIGMAPLOT (ver. 14). Data has been presented as mean ± standard error. One way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was done to check if any significance was detected in data from the various experimental groups. The level of significance was established at p ≤ 0.05 at every instance for all the tests throughout the study. In case, of a significant interaction among the factors (species x concentrations of NiO-NP), Post-hoc Tukey’s Test was done.

Results

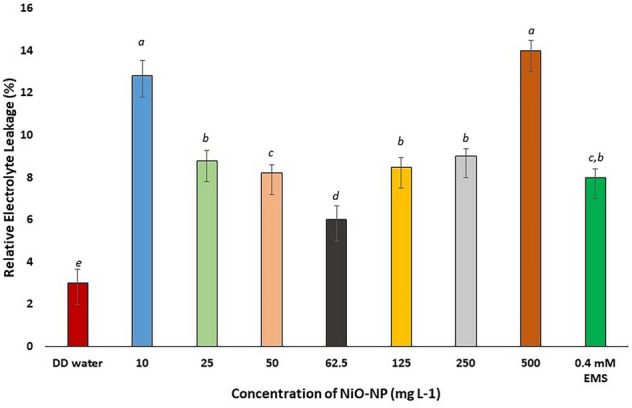

Extensive membrane damage occurs in root tips of A. cepa upon NiO-NP exposure

Damage to cell membrane integrity after NiO-NP exposure was evaluated by quantifying relative electrolyte leakages of root tissues (Fig. 2), comparing NC sets against the treated samples. Treated root samples showed increased electrolyte leakage in all the concentrations of NiO-NP used with respect to control sets. Highest increment in electrolyte leakage was observed in roots exposed to 10 mg L−1 NiO-NP (3.01 in NC to 12.8 at 10 mg L−1 NiO-NP concentration), followed by a 156% increase (7.8 at 25 mg L−1 NiO-NP against NC) at 25 mg L−1 of NiO-NP. At higher doses (250 and 500 mg L−1), electrolyte leakage increased between 150 and 350% with respect to the NC (electrolyte leakage at 250 mg L−1 being 8 and at 500 mg L−1 is 14). Significant increase (p ≤ 0.005) in electrolyte leakage at the lowest dose of NiO-NP indicated extensive membrane damage, while the exposure to higher dosages alluded to extensive cellular injury (Fig. 2). Marginally lower electrolyte leakage in the intermediate doses (62.5–125 mg L−1) might be attributed to the ENP morphology and lesser aggregation.

Fig. 2.

Relative electrolyte leakage in Allium cepa roots on NiO-NP exposure; At least 5 data sets were used for statistical analyses; Different letters at the top of the bars represent significant differences (p < 0.005) between the treatments after performing One-way ANOVA

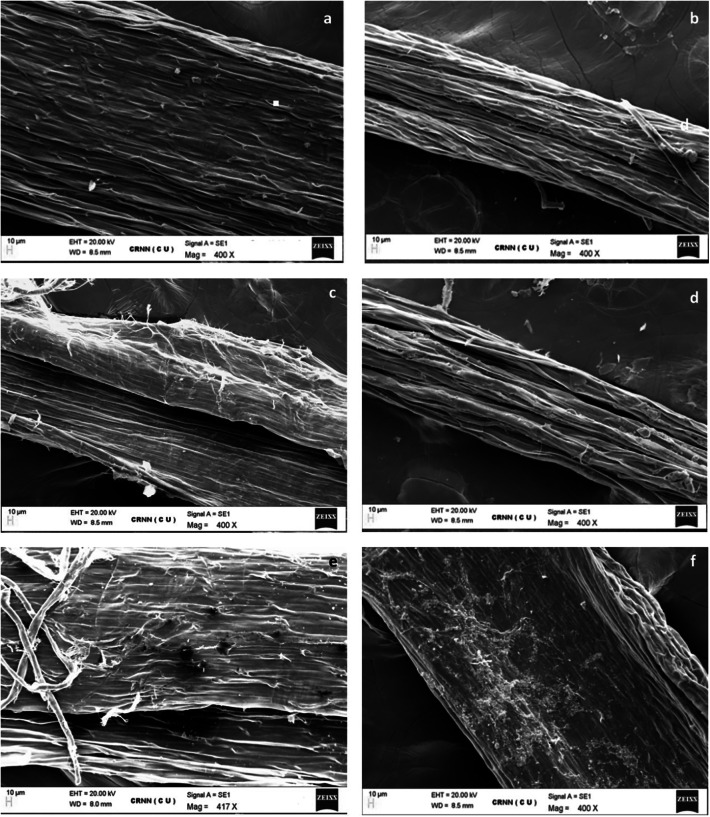

SEM images depict consequential cell membrane damages caused by incrementing doses of NiO-NP

SEM analyses of the control and treated root tips showed substantial changes in their overall morphological features (Fig. 3). Topmost/epidermal layers of the treated roots appeared shrivelling and their margins diminished, exposing the endodermal layer below, as opposed to the usual smooth epidermis of the control root tips (Fig. 3a). Significant cell membrane damages was documented in root tips exposed to even the lowest dose of NiO-NP (10 mg L−1). With increase in dosage, membrane breakdown became more prominent with clumped deposition of NiO-NP on root surfaces at higher concentrations (125–500 mg L−1). The smooth, expanded surface of control roots was damaged, shrunken brittle ones after NiO-NP treatment.

Fig. 3.

a-f Effect of increasing NiO-NP concentration on integrity of cellular membrane in experimental samples detected through SEM imaging (a-negative control, b-10, c-50, d-125, e-250, f-500 mg L−1 of NiO-NP respectively; magnification ~ 400X

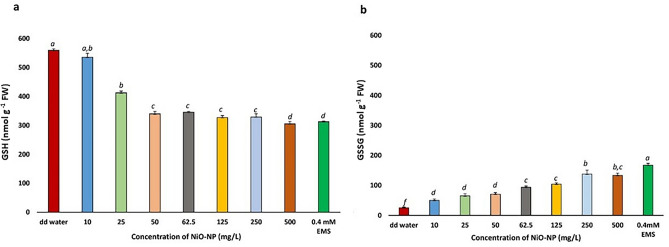

NiO-NP exposure reduces GSH and increases GSSG levels

Steadily diminishing levels of reduced glutathione were observed in the treated root tips concomitant with increasing doses of NiO-NP. While in the NC, GSH was around 560 nmol g−1 FW, after exposure to NiO-NP even at the lowest doses, decrease of cellular GSH content was significant (p ≤ 0.05) with ~ 4% decrease in 10 mg L−1 to 535.8 nmol g fw−1 from 559.53 nmol g fw−1 in NC and 26% decrease in 25 mg L−1 of NiO-NP to 412.41 with respect to the NC sets. GSH levels further dwindled to less than 40% of the NC in roots exposed to 62.5 mg L−1 NiO-NP to 345.83 nmol g fw−1. In NiO-NP concentrations between 125 and 500 mg L−1 of NiO-NP, decrease in GSH content were between 23% (387.39 nmol g fw−1) and 18% (455.56 nmol g fw−1) less than the NC (significant at p ≤ 0.05) (Fig. 4a).

Fig. 4.

a Reduced glutathione (GSH) content in Allium cepa roots on NiO-NP exposure; b Oxidised glutathione (GSSG) content in Allium cepa roots on NiO-NP exposure; At least 5 data sets were used for statistical analyses; Different letters at the top of the bars represent significant differences (p < 0.005) between the treatments after performing One-way ANOVA

A gradual NiO-NP dose dependent increase in GSSG levels were observed in the treated sets. While roots maintained in pure water (NC) showed 25 nmol g−1 of GSSG, it increased to 50 nmol g−1 in roots exposed to 25 mg L−1 and around 100 nmol g−1 in those treated to125 mg L−1NiO-NP, highest increment was noticed in roots grown in 250 mg L−1 NiO-NP (137 nmol g−1). Increase in GSSG content was significant with respect to NC sets at all the concentrations (Fig. 4b).

LSCM studies also confirmed a decrease in the presence of low molecular weight thiols, like GSH, in the affected root tips with concurrent increase of intracellular ROS corresponding to increments in NiO-NP doses. Treated roots, as well as, control sets, showed a marked blue fluorescence of fluorescent GSH-low molecular weight thiol conjugates. Fluorescence in the treated sets were significantly reduced with respect to untreated controls signifying decreased GSH levels (Fig. 5). Lowest fluorescence was recorded in root tips at 62.5 and 125 mg L−1 NiO-NP.

Fig. 5.

a-f Effect of increasing NiO-NP concentration on reduced glutathione (GSH) content in the treated samples following monochlorobimane staining documented through LSCM (a-negative control, b-25, c-50, d-125, e-250 and f-500 mg L−1 of NiO-NP respectively; bar represented 130 μm)

GSH-GSSG ratio is adversely affected by exposure of NiO-NP

GSH:GSSG ratio is an important parameter that determines health of any living cell. A steady decrease in this ratio was documented in exposed roots congruent with increase in NiO-NP concentration. In the NC sets, while this ratio was 21:1, it decreased to 11:1 in roots growing at the lowest dose of NiO-NP (10 mg L−1), further decreasing to around 5:1 and 4:1 in roots exposed to at 62.5 mg L−1 NiO-NP and 125 mg L−1 NiO-NP respectively.

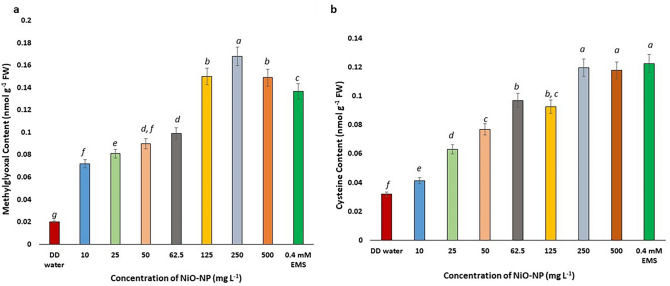

Concentration of Methylglyoxal increases with increasing NiO-NP doses

Methylglyoxal (MG) is a cytotoxic by-product formed via various metabolic mechanisms, primarily during glycolytic process, whose increment in the cell harms cellular proliferation and aids protein degradation. In the present study, a steady rise in MG level was noted in treated root-tips with increasing NiO-NP concentrations, beginning at the lowest dose (10 mg L−1) where a 250% rise in MG was detected (0.02 nmol g−1 at NC to 0.072 nmol g−1 at 10 mg L−1), followed by 300% rise at the next higher concentration (0.081 nmol g−1 at 25 mg L−1) (Fig. 6a). Around 400% increase of MG was recorded in roots exposed to 62.5 mg L−1 amounting to 0.09 nmol g−1, and the highest increase was recorded in roots exposed to 250 mg L−1 of NiO-NP at 0.168 nmol g−1 which is 740% rise over NC. All the increments were significant (p ≤ 0.05) at all the concentrations of NiO-NPs (Fig. 6a).

Fig. 6.

a Methylglyoxal content; b Cysteine content in Allium cepa roots on NiO-NP exposure; At least 5 data sets were used for statistical analyses; Different letters at the top of the bars represent significant differences (p < 0.005) between the treatments after performing One-way ANOVA

Cysteine accumulates in the NiO-NP treated tissues

Increased accumulation of cysteine, an important marker of abiotic stress, was observed in all the NiO-NP treated root tips. Root tips of A. cepa bulbs exposed to 10 mg L−1 of NiO-NP showed an increase of ~ 30% cysteine content over NC from 0.032 nmol g−1 in NC set to 0.0414 nmol g−1 at 10 mg L−1. Cellular concentration of cysteine escalated to 96% over pure water control in roots exposed to 25 mg L−1 NiO-NP amounting to 0.063 nmol g−1. The highest increment in cysteine content was noted at 500 mg L−1 of NiO-NP concentration at 0.148 nmol g−1 (365% increase over NC) (Fig. 6b). All the data showed significant (p ≤ 0.05) increase of cellular cysteine over NC sets. Thus, a positive correlation of cysteine accumulation with that of NiO-NP concentration was confirmed from the present study (Fig. 6b).

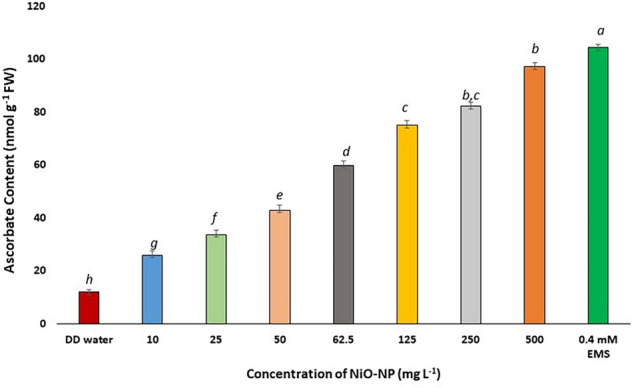

Ascorbate content changes with NiO-NP exposure

Ascorbate plays an integral role as scavenger of ROS especially in the ascorbate-glutathione cycle (Horemans et al. 2000). In the present study, an increase in ascorbate content was noted in all the concentrations of NiO-NP especially at the lowest and median concentrations of the NiO-NP treated (10–62.5 mg L−1) roots of Allium cepa. At lower concentrations of NiO-NP (10–25 mg L−1), ascorbate content increased around 27 and 42% respectively over the NC i.e., from 12.03 nmol g−1 in NCs to 25.87 nmol g−1 at 10 mg L−1 and 33.69 nmol g−1 at 25 mg L−1 (Fig. 7). Increase in ascorbate content with respect to control set was seen in the next two concentrations of NiO-NP (50 and 62.5 mg L−1) as well. Roots exposed to the subsequent higher concentrations of NiO-NP (125–500 mg L−1) showed further increase in ascorbate content. Maximum increase of ~ 144% against NC was noted at the highest concentration of NiO-NP used i.e. (500 mg L−1 equivalent to 97.21 nmol g−1), followed by the positive control. Thus, a steady, significant, dose dependent change of ascorbate was registered in the roots of A. cepa.

Fig. 7.

Ascorbate content in Allium cepa roots on NiO-NP exposure; At least 5 data sets were used for statistical analyses; Different letters at the top of the bars represent significant differences (p < 0.005) between the treatments after performing One-way ANOVA

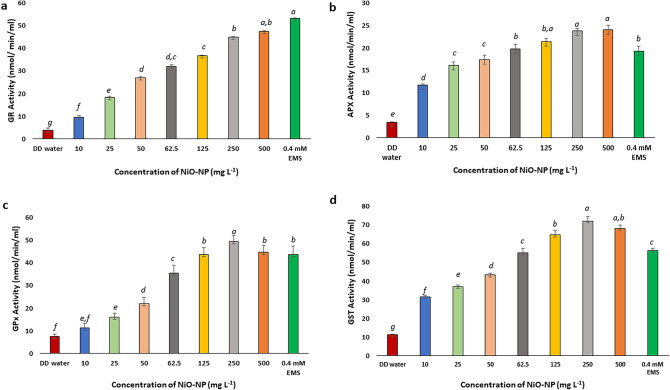

NiO-NP treatment positively affects GR and GPx activities in exposed tissues, and increases APx and GST activities

Glutathione Reductase (GR) is a crucial enzyme responsible for maintaining the pool of reduced GSH by providing –SH group and also acting as a substrate for GST (Yousuf et al. 2012). Root tips of A. cepa after treatment with different concentrations of NiO-NP showed reduction in GR activity in all the sets. While a 9.449 nmol min−1 ml−1 equivalent to decrease of ~ 20% of GR activity was observed in root tips grown in 10 mg L−1 NiO-NP from 3.742 nmol min−1 ml−1 at NC, a consistent dose dependent decrease was observed in all the other concentrations as well (Fig. 8a). Around 50% decrease in GR activity was noted in roots at 62.5 mg L−1 of NiO-NP i.e., 31.94 nmol min−1 ml−1, while a 63% decrease was observed at the highest dose (500 mg L−1) where 47.32 nmol min−1 ml−1 is recorded. Significant (p ≤ 0.05) decrease was observed at all concentrations against the water control.

Fig. 8.

Effect of NiO-NP exposure on enzyme activities in Allium cepa roots. a Glutathione reductase (GR) activity; b Ascorbate peroxidase (APX) activity; c Glutathione peroxidase (GPx) activity; d Glutathione transferase (GST); At least 5 data sets were used for statistical analyses; Different letters at the top of the bars represent significant differences (p < 0.005) between the treatments after performing One-way ANOVA

Glutathione peroxidase (GPx) which is responsible for converting hydrogen peroxide into water through the ascorbate-glutathione cycle, showed increased activity under NiO-NP stress. At 10 mg L−1 NiO-NP concentration, GPx activity was 11.18 nmol min−1 ml−1 documenting a decrease by 10%, from 7.54 nmol min−1 ml−1 at NC; followed by 13.5 and 11% decrease in 25 (16.1 nmol min−1 ml−1) and 50 (21.89 nmol min−1 ml−1) mgL−1 NiO-NP exposures respectively. GPx level also decreased to 49.27 around 27% at 250 mgL−1 NiO-NP. Except at 10 and 50 mg L−1 NiO-NP, decrease of GPx activity in all the other concentrations were significant (p ≤ 0.05) (Fig. 8c). An important observation noted here was that there was a decrease of ~ 15% GPx activity in A. cepa roots (44.55 nmol min−1 ml−1) exposed to positive control against 24% significant decrease in roots exposed to highest dose of 500 mgL−1 of NiO-NP (Fig. 8c).

Ascorbate peroxidase (APx) is responsible for donating electrons in the conversion of hydrogen peroxide to water via the ascorbate-glutathione cycle (Caverzan et al. 2012). In the model system, onion, under NiO-NP treatment, there was a univocal increase in APx activity against NC (3.377 nmol min−1 ml−1) in all the concentrations of NiO-NP used, while an increase in APx activity was observed of ~ 17% at the lowest dose NiO-NP used (10 mg L−1 that showed a value of 11.71 nmol min−1 ml−1) followed by 16.09 nmol min−1 ml−1, an increase of 20% at 25 mg L−1 of NiO-NP, and a significant increase was also registered in all the subsequent concentrations. Highest increase in APx activity was noted in roots exposed to 500 mg L−1 of NiO-NP i.e., 24.039 nmol min−1 ml−1 (77% increase over NC), almost double the APx activity registered in the positive control (Fig. 8b).

GST catalyses the reaction of GSH with reactive oxygen molecules thus protecting the cell against external damages. There is a steady increase in GST activity in the NiO-NP treated sets against the NC. Significant changes were observed in all the sets in a dose specific manner. While there was an increase of ~ 50% GST activity at the lowest dose of 10 mg L−1 NiO-NP i.e., from 11.139 nmol min−1 ml−1 in NC to 31.507 nmol min−1 ml−1 in 10 mg L−1, subsequent concentrations showed further increase in GST activity (43.164 nmol min−1 ml−1 resembling 75% increase over NC at 50 mg L−1). Highest increase was noted at 250 mg L−1 with 72.06 nmol min−1 ml−1 which accounts for 240% increase over control (Fig. 8d).

Discussion

Nanoparticles can easily enter cells through their membranes (Ma et al. 2010). Being dynamic structures, membranes are indeed major targets of environmental stresses, (Itri et al. 2014). NiO-NP caused devastating damages to cell membranes enroute their entry into the cells. Morphological destruction as seen from SEM images culminated in physiological and biochemical disturbances. Frequently related increased membrane permeability, affecting its integrity and cell compartmentation (Dubey 1997). Electrolyte leakage, is induced upon exposure to abiotic or biotic agents of stress (Lee and Zhu 2010). Typically, in the event of cell death cell membrane becomes flaccid, leaking electrolytes like K+ (Hatsugai and Katagiri 2018). Assessment of electrolyte leakage is thus often used as an indirect means of calculating plant cell death in response to various biotic stressors (Maffei et al. 2007) and abiotic signals (Demidchik et al. 2014). Roots are especially susceptible towards K+ efflux (Shabala et al. 2006), often coupled with Ca2+ and H+ efflux (Demidchik 2014). Ahmad et al. (2012) showed electrolytic leakage when two cultivars of Brassica were subjected to treatment with cadmium and lead or a mixture of the two, as was reported when maize was exposed to cadmium (Ekmekçi et al. 2008). Similar observations were reported in Bacopa monnieri, (Mishra et al. 2006), Oryza sativa (Llamas et al. 2000), Silene cucubalus (De Vos et al. 1992) and in Pisum sativum (Rahoui et al. 2010). A sudden rise in electrolytic leakage in A. cepa roots when subjected to NiO-NP exposure as documented here could be justified from these above instances as well. Young roots experiencing NiO-NP exposure could not retain their integrity after losing K+. Relative electrolyte leakage assay confirmed that the cellular membranes were damaged univocally upon NiO-NP exposure (Fig. 2). Loss in membrane potential observed at the lowest NiO-NP dose was already too much, beyond which at higher doses the leakage was irreparable as reported earlier in young date palms (Zouari et al. 2016). Shape of the nanoparticle also play an interesting role in defining toxicity, as amorphous or irregular shaped NPs with more surface defects and active sites generate more ROS than symmetrical NPs (Huang et al. 2017). In the median concentrations of NiO-NPs (50, 62.5, 125 mg L−1), more NPs with active sites are available that increased electrolyte leakage. With increase in concentration and time of exposure NiO-NP dispersion in aqueous solution was decreased and the aggregated forms damaged root epidermal integrity extensively, disturbing conductance of the cellular membranes.

Electrolyte leakage is often followed by oxidative burst, either provoking programmed cell death cascade in extreme cases, or, in case of moderate challenges leading to stress adaptations (Demidchik et al. 2014). Quantification of H2O2 was done in the present study to ascertain whether NiO-NP exposure can incite its formation of H2O2 culminating in disruption of Asa-GSH cycle. H2O2 has an undeniable role in cellular signal transduction and is the most stable of all ROS. It interacts with proteins in the thiol moiety and acts as transcription factor in various genetic cascades too (Slesak et al. 2007). Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) are indispensable to cellular homeostasis, playing key roles in cell signalling. Highly active organelles, viz., mitochondria, peroxisome and chloroplasts, are the chief producers of ROS. Heavy metals are known inducers of intracellular ROS and bulk nickel reportedly induces ROS via NADPH oxidase dependent pathway (Hao et al. 2006). Though the exact mechanism for nickel toxicity has not yet been demarcated, the most prominent expression of exposure is a concurrent shutdown of the biochemical, physiochemical, molecular and ultra-structural networks as evident from the present study too. The dye Amplex Red is classically used as an accurate indicator of cellular ROS- H2O2 (Šnyrychová et al. 2009). Previous work on titanium bulk and nanoparticles in Pisum sativum showed an increase in fluorescence in presence of H2O2 (Giorgetti et al. 2019) and in chamomile upon Cd stress (Kováčik et al. 2014). In the present study too increased fluorescence in Amplex Red stained root tips indicated a concurrent NiO-NP dose dependent rise in H2O2 content. It H2O2 forms the core of the “redox hub” along with GSH:GSSG ratio (Foyer et al. 1997), which interestingly was also compromised in case of perturbation by NiO-NP exposure as evident from this study. Earlier Ghosh et al. (2016) have shown such an increase in H2O2 in plants under ZnO-NP treatment. Nair and Chung (2015) and Da costa and Sharma (2016) also found such a correlation in Brassica juncea and Oryza sativa respectively when exposed to copper oxide nanoparticle, deducing that a rise in H2O2 leads to intracellular perturbations in plants causing potentially irreparable damages. Supplementary Fig. 1 and Supplementary Fig. 2 corroborate the findings.

Cysteine, a small sulphur donating molecule, is of paramount interest because of its multifunctional characteristics. Extremely useful in generation of GSH and proteins (Stroiński, 1999), its role in metal detoxification is elaborate (Gupta et al. 1999). Increase in cysteine content in the present study could be corroborated to the findings of Gupta et al. (2009) in Triticum and Brassica where cysteine registered increased accumulation on advent of cellular ROS (Nouairi et al. 2009). Similar results were earlier shown by Sinha et al. (1996) too in Hg stress on Bacopa monnieri. Initial increase in cysteine level could be owing to upregulated NiO-NP detox process within the cell. However, aggravated presence of thiolic groups, often associated with stress response in a plant, might lead to the increased production of cysteine (Foyer and Noctor 2012) similar to the observation in A. cepa exposed to higher concentrations of NiO-NP. Cysteine residues are interlinked to GSH where thiol group containing proteins are maintained at their native state by the reactive cysteine residues as seen during water stress (Potters et al. 2002).

Methylglyoxal (MG) is a cytototoxic low molecular weight aldehyde formed as an intermediate in various metabolic pathways, especially during abiotic stress (Mostofa et al. 2018). MG is formed directly in response to ROS accumulation and vice versa (Tatsunami et al. 2009). In rice, MG and ROS levels were increased on cadmium exposure (Rahman et al. 2016), as was also seen in Mung beans and Cucurbita maxima (Nahar et al. 2016). Rice plants subjected to copper toxicity also showed higher levels of MG accumulation (Mostofa et al. 2018). When A. cepa roots were exposed to NiO-NP in the present experiment, MG content increased till 250 mg L−1, though at the highest concentration of NiO-NP, MG concentration declined. A possible explanation is that at higher NiO-NP concentrations lesser quantum of nanoparticles can enter the cell owing to aggregate formation and most cells die because of shutdown of the entire antioxidant system. Interestingly, this observation corroborates to the unique relationship among NP shape, size, surface charge and internal physiology of a particular cell in question, abruptly shaped NPs exert more cytotoxicity than regular NPs (Huang et al. 2017), NPs larger in size could not get proper membrane wrapping for internalization due to receptor shortage leading to increased entropy and more surface damages (Hoshyar et al. 2016) which inadvertently leads to increased ROS production and over activity in cell’s antioxidant machineries.

During abiotic stress, GSH shows cellular compartmentalization, for e.g., high peroxisomal and chloroplast GSH levels have significant effects during episodes of high light and salinity stress. Reduction in GSH levels in these organelles lead to ROS accumulation, followed by chlorosis and necrosis. In both plant and animal cells during initial stages, GSH co-localizes with nuclear DNA, and protects nuclear components against ROS, simultaneously regulating stress response genes. GSH:GSSG ratio is a vital parameter determining general health of a cell, when GSSG is formed, only to be is promptly reconverted to GSH by GR using reduced NADPH. A higher flux of GSH is reportedly best suited for cellular balance and stress mitigation (Hoque et al. 2016), with a ratio of 20:1 GSH: GSSG maintained in a healthy cell (Foyer and Noctor 2012). In the present work, the healthy NC root sets demonstrated a GSH:GSSG ratio of 21:1 where as a GSG:GSSG ratio of 11:1 at 10 mg L-1 niO-NP concentration which decreased to 4:1 at 125 mg L-1 NiO-NP concentration were recorded. Lower GSH:GSSG ratio is an indication of oxidative stress in plants (Hasanuzzaman et al. 2012). While relative stress resistance could be attributed to inherently higher GSH: GSSG levels in salt-tolerant plants under salinity stress (Mittova et al. 2003). Similarly, in case of heavy metal exposure, like cadmium (Cd) stress, equilibrium of GSH and their oligomers,phytochelatin was found to be crucial for stress management. That phytochelatins bind with Cd and potentiate their vacuolar aggregation was deemed necessary for ameliorating cadmium induced toxicity in rice, Brassica juncea, Brassica campestris, Mung beans and Pisum sativum (Chou et al. 2012; Iqbal et al. 2010; Wu et al. 2015; Nahar et al. 2016; Pandey and Singh 2012). In susceptible plants, GSH level goes down normally, while in accumulators like Medicago sativa (Zhou et al. 2009) and Holcus lanatus (Raab et al. 2004) showed increased GSH levels on Hg stress. GSH level decreased in the NiO-NP treated sets, when assessed biochemically and using confocal microscope images of monochlorobimane staining, that forms an adduct called bimane-glutathione with GSH (Haugland 2005). This observation has been reported by many researchers in recent times, Sousa et al. (2018) in yeast exposed to NiO-NP, Jahan et al. (2016) and Meyer et al. (2008) in Arabidopsis and in case of salinity stress in rice (Das et al. 2018).

Heavy metal induced increase or decrease in ascorbate levels in the treated plants depended intrinsically on physiology of the plant and their biochemical interactions. Earlier work on effect of chromium exposure has shown decreased ascorbate levels in Ocimum tenuiflorum (Rai et al. 2004). Similarly, reduction in ascorbate content was noted in potato tubers under cadmium toxicity and the resistant varieties showed higher residual ascorbate content. Ascorbic acid content decreased in Hydrilla verticillata after exposure to high doses of copper for a prolonged period of time (Gupta et al. 1996). However, at higher concentrations, lack of sulphate-reducing enzymes made ascorbate content scarce in the treated tissue in Zea mays (Nussbaum et al. 1988). In A. cepa roots exposed to varying concentrations of NiO-NPs showed a similar trend of decrease in ascorbate content with increasing NiO-NP dosage. Ascorbate, as well as GSH, available in relatively higher percentage in plant cells, constitute the intricate “redox hub” in the chloroplast (Foyer and Noctor 2012). These nucleophiles, along with NADPH and a set of enzymes form the glutathione-ascorbate cycle, acting on peroxides, not only under stress but at different phases of the plant life cycle to boost growth and development (Vivancos et al. 2010). Catalases, along with the Asa-GSH cycle, constitute the primary H2O2 elimination pathways, restituting the intricate homeostasis in cellular systems. However, such a specific mechanism has not yet been elucidated in NiO-NP stress. The authors have already reported that consequent to NiO-NP induced damage to the epidermal cells of exposed A. cepa roots, physicochemical collapse of cellular system ensues, paralysing antioxidant networks, further inducing genomic damages (Manna and Bandyopadhyay 2017a, b).

A major enzyme of the ascorbate-glutathione cycle is ascorbate peroxidase (APx) (EC 1.11.1.11), a class I heme-peroxidase, that catalyses conversion of H2O2 into water, ascorbate is being the substrate (Asada 1992). APx isoforms are found in chloroplasts, peroxisomes, mitochondria, cytosols or glyoxisomes (Caverzan et al. 2012). Most heavy metals cause an increase in the APx activity in plants. Increased APx activity was detected in rice subjected to aluminium stress (Rosa et al. 2010), in bean and tobacco subjected to iron toxicity (Pekker et al. 2002) as also in cases of copper, cadmium, zinc and arsenic stress in Brassica juncea (Rao and Sekhawat 2014). Coffee cells showed increased APx activity on bulk Ni exposure (Gomes-Junior et al. 2006), as did Maize, after going through Ni infusion (Baccouch et al. 2006). In wheat, several fold increase in APx and GST were observed after Ni exposure (Gajewska and Skłodowska 2007). Interestingly no reports on APx content variation after NiO-NP treatment exist, and among the nanoparticles tested, ZnO and CuO exposure induced APx accumulation (Da costa and Sharma 2016). It can thus be deduced that by modulating APx levels, A. cepa roots too tried ameliorating toxic NiO-NP doses via the glutathione-ascorbate cycle.

Glutathione peroxidase (EC 1.11.1.9.), first discovered in mammalian red blood cell, is responsible for maintenance of cellular membranes (Paglia and Valentine 1967). Plant GPxs differ in having a central cysteine and a total of 8 isoforms have been worked on so far (Toppo et al. 2008). A major participant of H2O2 degradation especially during stress response of a cell, GPx also helps in preventing DNA damage (Passaia et al. 2015). Moreover, some isoforms are responsible for switching on apoptotic cascades as well, but the main function of GPx is in reduction of cellular ROS interlinked with Glutathione transferase (GST) functions (Ighodaro et al. 2018).

Glutathione Reductase (EC 1.6.4.2) is one of the homodimeric, flavo-protein oxidoreductases that channel the reaction where GSSG is reduced to form reduced sulphydryl GSH using NADPH, connecting the ASA-GSH cycle and maintenance of higher flux of intracellular GSH, in return sustaining GR in its active dimeric form. In fact, with Superoxide Dismutase (SOD), GR forms the first line of defence against ROS in any normal cell helping in keeping the GST moiety constant. In case of nanoparticle stress, along with catalase, these enzymes form the backbone that breaks down intracellular H2O2 (Gill et al. 2013). Increased activities of GR, GPx and GST were reported in graphene oxide nanoparticles treated Vicia faba plants. Tolerance or susceptibility to such NPs ultimately depended on internal GSH: GSSG pool and the related enzyme activities (Anjum et al. 2013). Though Faisal et al. (2013) reported an increase in GSH content in tomato in a pioneering work upon NiO-NP exposure, the present study shows an opposite trend. NiO-NP treated A. cepa seedlings showed that GSH levels depended on the intrinsic nature of the specific plant being studied. Hence, both these contra-indicative observations are possible in the respective plants and reflect the nature and biochemical status of those particular cellular components under stress. Interestingly Tripathi et al. (2017) have reported that ZnO-NP caused decreased level of APX and GR in Pisum sativum in concordance with the present work.

In the present work, the authors have shown that NiO-NP acts analogous to its bulk counterpart when Allium cepa root tips are exposed to it even for 24 h. We found that in order to tackle the excess intrusion of an essential metal in form of its oxide nanoparticle (NiO-NP) and the oxidative burst that follows, the plant upregulates its antioxidants, most notably the ascorbate-glutathione cycle. Presently, Asa-GSH cycle becomes overwhelmed after exposure to 125 mg L−1 of NiO-NP, when most of the assays indicated shutdown of the antioxidant mechanism. Figure 9 shows a complete overview of the work presented here. In previous reports we have shown how NiO-NP paralyses the cell, with the collapse of the antioxidant network, including SOD, Catalase, POD and other enzymes. Here we have shown that major damages to the Asa-GSH cycle actually compromises this network. Thus, the present work bolsters knowledge and understanding how exactly NiO-NP causes cellular damage and leads to complete shutdown of biochemical and physiological processes.

Fig. 9.

Schematic presentation of possible mechanism of NiO-NP affected Asa-GSH cycle and cell cycle in A. cepa roots (Prepared by the authors without using any copyrighted images/objects)

Conclusion

Ascorbate-glutathione cycle is indispensable for any living cell, which either directly or through its products controls the survival of a cell by amelioration of stress. Such a mechanism is well established in numerous model systems. However, if such is the standard modus operandi in case of NiO-NP stress was not exactly known so far. How NiO-NP cripples Asada-Halliwell cycle to corrupt the cellular integrity in the roots of a model toxicological system, Allium cepa, has not been elucidated so far. In this manuscript, the authors have highlighted such a mechanism to conclude that NiO-NP indeed corrodes Asa-GSH cycle preventing cellular well-being, reiterated through biochemical assays and confocal microscopy. This manuscript aims to fill the gap in knowledge that indeed GSH:GSSG ratio and the pertaining cycle holds the redox flux necessary for cell survival. Detailed analyses of Asa-GSH cycle in plants under nanoparticle stress is scarce and this work can act as a connecting link to better understanding of NiO-NP toxicity in a model system.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the facilities provided by the Department of Botany (CAS Phase VII), University of Calcutta, DBT-IPLS facility, University of Calcutta for confocal microscopy facility and IM would like to thank UGC under Government of India for CSIR-UGC NET fellowship scheme.

Authors’ Contribution

All the authors univocally approved for the work. IM designed the experiments, set out the framework and carried out the experiments and prepared the manuscript and data interpretation and MB supervised and checked the manuscript and helped in the preparation.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors would like to declare that there is no conflict of competing interest, and no commercial or financial aid which can be construed as a conflicting interest, has been involved in the study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Ahmad P, Ozturk M, Gucel S. Oxidative damage and antioxidants induced by heavy metal stress in two cultivars of mustard (Brassica juncea L.) plants. Fresenius Environ Bull. 2012;21(10):2953–2961. doi: 10.1078/0176-1617-00833. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ando K, Honma M, Chiba S, Tahara S, Mizutani J. Glutathione transferase from Mucor javanicus. Agric Biol Chem. 1988;52(1):135–139. doi: 10.1271/bbb1961.52.135. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Anjum NA, Singh N, Singh MK, Shah ZA, Duarte AC, Pereira E, Ahmad I. Single-bilayer graphene oxide sheet tolerance and glutathione redox system significance assessment in faba bean (Vicia faba L.) J Nanoparticle Res. 2013;15(7):1770. doi: 10.1007/s11051-013-1770-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Asada K. Ascorbate peroxidase–a hydrogen peroxide-scavenging enzyme in plants. Physiol Plant. 1992;85(2):235–241. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3054.1992.tb04728.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baccouch M, Choura S, El-Borgi S, Nayfeh AH. Selection of physical and geometrical properties for the confinement of vibrations in nonhomogeneous beams. J Aerosp Eng. 2006;19(3):158–168. doi: 10.1061/(ASCE)0893-1321(2006)19:3(158). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berni R, Luyckx M, Xu X, Legay S, Sergeant K, Hausman JF, Guerriero G. Reactive oxygen species and heavy metal stress in plants: impact on the cell wall and secondary metabolism. Environ Exp Bot. 2019;161:98–106. doi: 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2018.10.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron SJ, Sheng J, Hosseinian F, Willmore WG. Nanoparticle effects on stress response pathways and nanoparticle-protein interactions. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(14):7962. doi: 10.3390/ijms23147962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caverzan A, Passaia G, Rosa SB, Ribeiro CW, Lazzarotto F, Margis-Pinheiro M. Plant responses to stresses: role of ascorbate peroxidase in the antioxidant protection. Genet Mol Biol. 2012;35(4):1011–1019. doi: 10.1590/S1415-47572012000600016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou TS, Chao YY, Kao CH. Involvement of hydrogen peroxide in heat shock-and cadmium-induced expression of ascorbate peroxidase and glutathione reductase in leaves of rice seedlings. J Plant Physiol. 2012;169(5):478–486. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2011.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Da Costa MVJ, Sharma PK. Effect of copper oxide nanoparticles on growth, morphology, photosynthesis, and antioxidant response in Oryza sativa. Photosynthetica. 2016;54(1):110–119. doi: 10.1007/s11099-015-0167-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Das P, Manna I, Biswas AK, Bandyopadhyay M. Exogenous silicon alters ascorbate-glutathione cycle in two salt-stressed indica rice cultivars (MTU 1010 and Nonabokra) Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2018;25(26):26625–26642. doi: 10.1007/s11356-018-2659-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demidchik V, Straltsova D, Medvedev SS, Pozhvanov GA, Sokolik A, Yurin V. Stress-induced electrolyte leakage: the role of K+-permeable channels and involvement in programmed cell death and metabolic adjustment. J Exp Bot. 2014;65(5):1259–1270. doi: 10.1093/jxb/eru004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Vos CR, Vonk MJ, Vooijs R, Schat H. Glutathione depletion due to copper-induced hytochelatin synthesis causes oxidative stress in Silene cucubalus. Plant Physiol. 1992;98(3):853–858. doi: 10.1104/pp.98.3.853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubey RS. Nitrogen metabolism in plants under salt stress. In: Jaiwal PK, Singh RP, Gulati A, editors. Strategies for Improving Salt Tolerance in Higher Plants. New Delhi: Oxford and IBH Publ Co; 1997. pp. 129–158. [Google Scholar]

- Ekmekçi Y, Tanyolac D, Ayhan B. Effects of cadmium on antioxidant enzyme and photosynthetic activities in leaves of two maize cultivars. J Plant Physiol. 2008;165(6):600–611. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2007.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faisal M, Saquib Q, Alatar AA, Al-Khedhairy AA, Hegazy AK, Musarrat J. Phytotoxic hazards of NiO-nanoparticles in tomato: a study on mechanism of cell death. J Hazard Mater. 2013;250:318–332. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2013.01.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foyer CH, Lopez‐Delgado H, Dat JF, Scott IM. Hydrogen peroxide‐and glutathione‐associated mechanisms of acclimatory stress tolerance and signalling. Physiol Plant. 1997;100(2):241–254. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3054.1997.tb04780.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Foyer CH, Noctor G. Managing the cellular redox hub in photosynthetic organisms. Plant Cell Environ. 2012;35(2):199–201. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2011.02453.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaitonde MK. A spectrophotometric method for the direct determination of cysteine in the presence of other naturally occurring amino acids. Biochem J. 1967;104(2):627. doi: 10.1042/bj1040627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gajewska E, Skłodowska M. Effect of nickel on ROS content and antioxidative enzyme activities in wheat leaves. Biometals. 2007;20(1):27–36. doi: 10.1007/s10534-006-9011-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genisel M, Erdal S, Kizilkaya M. The mitigating effect of cysteine on growth inhibition in salt-stressed barley seeds is related to its own reducing capacity rather than its effects on antioxidant system. Plant Growth Regul. 2015;75(1):187–197. doi: 10.1007/s10725-014-9943-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh M, Jana A, Sinha S, Jothiramajayam M, Nag A, Chakraborty A, Mukherjee A. Effects of ZnO nanoparticles in plants: cytotoxicity, genotoxicity, deregulation of antioxidant defenses, and cell-cycle arrest. Mutat Res Genet Toxicol Environ Mutagen. 2016;807:25–32. doi: 10.1016/j.mrgentox.2016.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill SS, Anjum NA, Hasanuzzaman M, Gill R, Trivedi DK, Ahmad I, Tuteja N. Glutathione and glutathione reductase: a boon in disguise for plant abiotic stress defense operations. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2013;70:204–212. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2013.05.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giorgetti L, Spanò C, Muccifora S, Bellani L, Tassi E, Bottega S, Castiglione MR. An integrated approach to highlight biological responses of Pisum sativum root to nano-TiO2 exposure in a biosolid-amended agricultural soil. Sci Total Environ. 2019;650:2705–2716. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.10.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomes-Junior RA, Moldes CA, Delite FS, Gratão PL, Mazzafera P, Lea PJ, Azevedo RA. Nickel elicits a fast antioxidant response in Coffea arabica cells. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2006;44(5–6):420–429. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2006.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta M, Sinha S, Chandra P. Copper-induced toxicity in aquatic macrophyte, Hydrilla verticillata: effect of pH. Ecotoxicology. 1996;5(1):23–33. doi: 10.1007/BF00116321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta M, Cuypers A, Vangronsveld J, Clijsters H. Copper affects the enzymes of the ascorbate-glutathione cycle and its related metabolites in the roots of Phaseolus vulgaris. Physiol Plant. 1999;106(3):262–267. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3054.1999.106302.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta M, Sharma P, Sarin NB, Sinha AK. Differential response of arsenic stress in two varieties of Brassica juncea L. Chemosphere. 2009;74(9):1201–1208. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2008.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halder T, Upadhyaya G, Ray S. YSK2 type Dehydrin (SbDhn1) from Sorghum bicolor showed improved protection under high temperature and osmotic stress condition. Front Plant Sci. 2017;8:918. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.00918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao F, Wang X, Chen J. Involvement of plasma-membrane NADPH oxidase in nickel-induced oxidative stress in roots of wheat seedlings. Plant Sci. 2006;170(1):151–158. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2005.08.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hasanuzzaman M, Hossain MA, Jaime A, da Silva T, Fujita M. Plant response and tolerance to abiotic oxidative stress: antioxidant defense is a key factor. In: Venkateswarlu B, Shanker AK, Chitra Shanker M, editors. Crop stress and its management: perspectives and strategies. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands; 2012. pp. 261–315. [Google Scholar]

- Hatsugai N, Katagiri F. Quantification of plant cell death by electrolyte leakage assay. Bio-Protoc. 2018;8(5):e2758–e2758. doi: 10.21769/BioProtoc.2758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haugland RP (2005) The handbook: a guide to fluorescent probes and labeling technologies, Doctoral dissertation, Univerza v Ljubljani, Fakulteta za farmacijo

- Hoque TS, Hossain MA, Mostofa MG, Burritt DJ, Fujita M, Tran LSP. Methylglyoxal: an emerging signaling molecule in plant abiotic stress responses and tolerance. Front Plant Sci. 2016;7:1341. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.01341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horemans N, Foyer CH, Potters G, Asard H. Ascorbate function and associated transport systems in plants. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2000;38(7–8):531–540. doi: 10.1016/S0981-9428(00)00782-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hoshyar N, Gray S, Han H, Bao G. The effect of nanoparticle size on in vivo pharmacokinetics and cellular interaction. Nanomedicine. 2016;11(6):673–692. doi: 10.2217/nnm.16.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang YW, Cambre M, Lee HJ. The toxicity of nanoparticles depends on multiple molecular and physicochemical mechanisms. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18(12):2702. doi: 10.3390/ijms18122702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ighodaro OM, Akinloye OA. First line defence antioxidants-superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT) and glutathione peroxidase (GPX): their fundamental role in the entire antioxidant defence grid. Alexandria J Med. 2018;54(4):287–293. doi: 10.1016/j.ajme.2017.09.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Iqbal N, Masood A, Nazar R, Syeed S, Khan NA. Photosynthesis, growth and antioxidant metabolism in mustard (Brassica juncea L.) cultivars differing in cadmium tolerance. Agr Sci China. 2010;9(4):519–527. doi: 10.1016/S1671-2927(09)60125-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Itri R, Junqueira HC, Mertins O, Baptista MS. Membrane changes under oxidative stress: the impact of oxidized lipids. Biophys Rev. 2014;6(1):47–61. doi: 10.1007/s12551-013-0128-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahan MS, Nozulaidi M, Khairi M, Mat N. Light-harvesting complexes in photosystem II regulate glutathione-induced sensitivity of Arabidopsis guard cells to abscisic acid. J Plant Physiol. 2016;195:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2016.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones DP. Redox potential of GSH/GSSG couple: assay and biological significance. Meth Enzymol. 2002;348:93–112. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(02)48630-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jozefczak M, Remans T, Vangronsveld J, Cuypers A. Glutathione is a key player in metal-induced oxidative stress defenses. Int J Mol Sci. 2012;13(3):3145–3175. doi: 10.3390/ijms13033145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kováčik J, Babula P, Klejdus B, Hedbavny J, Jarošova M. Unexpected behavior of some nitric oxide modulators under cadmium excess in plant tissue. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(3):e91685. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0091685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee BH, Zhu JK. Phenotypic analysis of Arabidopsis mutants: electrolyte leakage after freezing stress. Cold Spring Harb Protoc. 2010;1:pdb.prot4970. doi: 10.1101/pdb.prot4970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llamas A, Ullrich CI, Sanz A. Cd2+ effects on transmembrane electrical potential difference, respiration and membrane permeability of rice (Oryza sativa L) roots. Plant Soil. 2000;219(1–2):21–28. doi: 10.1023/A:1004753521646. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ma X, Geiser-Lee J, Deng Y, Kolmakov A. Interactions between engineered nanoparticles (ENPs) and plants: phytotoxicity, uptake and accumulation. Sci Total Environ. 2010;408(16):3053–3061. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2010.03.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maffei ME, Mithöfer A, Boland W. Insects feeding on plants: rapid signals and responses preceding the induction of phytochemical release. Phytochemistry. 2007;68(22–24):2946–2959. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2007.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manna I, Bandyopadhyay M. Engineered nickel oxide nanoparticle causes substantial physicochemical perturbation in plants. Front Chem. 2017;5:92. doi: 10.3389/fchem.2017.00092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manna I, Bandyopadhyay M. Engineered nickel oxide nanoparticles affect genome stability in Allium cepa (L.) Plant Physiol Biochem. 2017;121:206–215. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2017.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manna I, Mishra S, Bandyopadhyay M. In vivo genotoxicity assessment of nickel oxide nanoparticles in the model plant Allium cepa L. The Nucleus. 2022;2022:1–12. doi: 10.1007/s13237-021-00377-w. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer AJ. The integration of glutathione homeostasis and redox signaling. J Plant Physiol. 2008;165(13):1390–1403. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2007.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer AJ, Fricker MD. Control of demand-driven biosynthesis of glutathione in green Arabidopsis suspension culture cells. Plant Physiol. 2002;130(4):1927–1937. doi: 10.1104/pp.008243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra S, Srivastava S, Tripathi RD, Govindarajan R, Kuriakose S, Prasad MNV. Phytochelatin synthesis and response of antioxidants during cadmium stress in Bacopa monnieri L.) Plant Physiol Biochem. 2006;44(1):25–37. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2006.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittler R, Vanderauwera S, Suzuki N, Miller GAD, Tognetti VB, Vandepoele K, Van Breusegem F. ROS signaling: the new wave? Trends Plant Sci. 2011;16(6):300–309. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2011.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittova V, Theodoulou FL, Kiddle G, Gómez L, Volokita M, Tal M, Guy M. Coordinate induction of glutathione biosynthesis and glutathione-metabolizing enzymes is correlated with salt tolerance in tomato. FEBS Lett. 2003;554(3):417–421. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(03)01214-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mostofa MG, Ghosh A, Li ZG, Siddiqui MN, Fujita M, Tran LSP. Methylglyoxal–a signaling molecule in plant abiotic stress responses. Free Radic Biol Med. 2018;122:96–109. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2018.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee SP, Choudhuri MA. Implications of water stress-induced changes in the levels of endogenous ascorbic acid and hydrogen peroxide in Vigna seedlings. Physiol Plant. 1983;58(2):166–170. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3054.1983.tb04162.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nahar K, Hasanuzzaman M, Alam MM, Rahman A, Suzuki T, Fujita M. Polyamine and nitric oxide crosstalk: antagonistic effects on cadmium toxicity in mung bean plants through upregulating the metal detoxification, antioxidant defense and methylglyoxal detoxification systems. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2016;126:245–255. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2015.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nair PMG, Chung IM. Study on the correlation between copper oxide nanoparticles induced growth suppression and enhanced lignification in Indian mustard (Brassica juncea L.) Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2015;113:302–313. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2014.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakano Y, Asada K. Hydrogen peroxide is scavenged by ascorbate-specific peroxidase in spinach chloroplasts. Plant Cell Physiol. 1981;22(5):867–880. [Google Scholar]

- Noctor G, Mhamdi A, Chaouch S, Han YI, Neukermans J, Marquez-Garcia BELEN, Foyer CH. Glutathione in plants: an integrated overview. Plant Cell Environ. 2012;35(2):454–484. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2011.02400.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nouairi I, Ammar WB, Youssef NB, Miled DDB, Ghorbal MH, Zarrouk M. Antioxidant defense system in leaves of Indian mustard (Brassica juncea) and rape (Brassica napus) under cadmium stress. Acta Physiol Plant. 2009;31(2):237–247. doi: 10.1007/s11738-008-0224-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nussbaum S, Schmutz D, Brunold C. Regulation of assimilatory sulfate reduction by cadmium in Zea mays L. Plant Physiol. 1988;88(4):1407–1410. doi: 10.1104/pp.88.4.1407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paglia DE, Valentine WN. Studies on the quantitative and qualitative characterization of erythrocyte glutathione peroxidase. J Lab Cin Med. 1967;70(1):158–169. doi: 10.5555/uri:pii:0022214367900765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandey N, Singh GK. Studies on antioxidative enzymes induced by cadmium in pea plants (Pisum sativum) J Environ Biol. 2012;33(2):201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passaia G, Margis-Pinheiro M. Glutathione peroxidases as redox sensor proteins in plant cells. Plant Sci. 2015;234:22–26. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2015.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pathan AK, Bond J, RnE G. Sample preparation for SEM of plant surfaces. Mater Today. 2010;12:32–43. doi: 10.1016/S1369-7021(10)70143-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pekker I, Tel-Or E, Mittler R. Reactive oxygen intermediates and glutathione regulate the expression of cytosolic ascorbate peroxidase during iron-mediated oxidative stress in bean. Plant Mol Biol. 2002;49(5):429–438. doi: 10.1023/A:1015554616358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potters G, De Gara L, Asard H, Horemans N. Ascorbate and glutathione: guardians of the cell cycle, partners in crime? Plant Physiol Biochem. 2002;40(6–8):537–548. doi: 10.1016/S0981-9428(02)01414-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Raab A, Feldmann J, Meharg AA. The nature of arsenic-phytochelatin complexes in Holcus lanatus and Pteris cretica. Plant Physiol. 2004;134(3):1113–1122. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.033506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman I, Kode A, Biswas SK. Assay for quantitative determination of glutathione and glutathione disulfide levels using enzymatic recycling method. Nat Protoc. 2006;1(6):3159. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman A, Mostofa MG, Nahar K, Hasanuzzaman M, Fujita M. Exogenous calcium alleviates cadmium-induced oxidative stress in rice (Oryza sativa L.) seedlings by regulating the antioxidant defense and glyoxalase systems. Rev Bras Bot. 2016;39(2):393–407. doi: 10.1007/s40415-015-0240-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rahoui S, Chaoui A, El Ferjani E. Membrane damage and solute leakage from germinating pea seed under cadmium stress. J Hazard Mater. 2010;178(1–3):1128–1131. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2010.01.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rai V, Vajpayee P, Singh SN, Mehrotra S. Effect of chromium accumulation on photosynthetic pigments, oxidative stress defense system, nitrate reduction, proline level and eugenol content of Ocimum tenuiflorum L. Plant Sci. 2004;167(5):1159–1169. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2004.06.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ranieri A, Castagna A, Baldan B, Soldatini GF. Iron deficiency differently affects peroxidase isoforms in sunflower. J Exp Bot. 2001;52(354):25–35. doi: 10.1093/jexbot/52.354.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao S, Shekhawat GS. Toxicity of ZnO engineered nanoparticles and evaluation of their effect on growth, metabolism and tissue specific accumulation in Brassica juncea. J Environ Chem Eng. 2014;2(1):105–114. doi: 10.1016/j.jece.2013.11.029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rosa SB, Caverzan A, Teixeira FK, Lazzarotto F, Silveira JA, Ferreira-Silva SL, Margis-Pinheiro M. Cytosolic APx knockdown indicates an ambiguous redox responses in rice. Phytochemistry. 2010;71(5–6):548–558. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2010.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafe FQ, Buettner GR. Redox environment of the cell as viewed through the redox state of the glutathione disulfide/glutathione couple. Free Radical Biol Med. 2001;30(11):1191–1212. doi: 10.1016/S0891-5849(01)00480-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sedlak J, Lindsay RH. Estimation of total, protein-bound, and nonprotein sulfhydryl groups in tissue with Ellman's reagent. Anal Biochem. 1968;25:192–205. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(68)90092-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shabala S, Demidchik V, Shabala L, Cuin TA, Smith SJ, Miller AJ, Newman IA. Extracellular Ca2+ ameliorates NaCl-induced K+ loss from Arabidopsis root and leaf cells by controlling plasma membrane K+-permeable channels. Plant Physiol. 2006;141(4):1653–1665. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.082388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha S, Gupta M, Chandra P. Bioaccumulation and biochemical effects of mercury in the plant Bacopa monnieri (L) Environ Toxicol Water Qual. 1996;11(2):105–112. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2256(1996)11:2<105::AID-TOX5>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Slesak I, Libik M, Karpinska B, Karpinski S, Miszalski Z. The role of hydrogen peroxide in regulation of plant metabolism and cellular signalling in response to environmental stresses. Acta Biochim Pol. 2007;54(1):39. doi: 10.18388/abp.2007_3267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith IK, Vierheller TL, Thorne CA. Properties and functions of glutathione reductase in plants. Physiol Plant. 1989;77(3):449–456. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3054.1989.tb05666.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Šnyrychová I, Ayaydin F, Hideg É. Detecting hydrogen peroxide in leaves in vivo–a comparison of methods. Physiol Plant. 2009;135(1):1–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3054.2008.01176.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sousa CA, Soares HM, Soares EV. Nickel oxide (NiO) nanoparticles induce loss of cell viability in yeast mediated by oxidative stress. Chem Res Toxicol. 2018;31(8):658–665. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrestox.8b00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroiński A. Some physiological and biochemical aspects of plant resistance to cadmium effect. I. Antioxidative system. Acta Physiol Plant. 1999;21:175–188. doi: 10.1007/s11738-999-0073-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tan HW, An J, Chu CK, Tran T. Metallic nanoparticle inks for 3D printing of electronics. Adv Electron Mater. 2019;5(5):1800831. doi: 10.1002/aelm.201800831. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tatsunami R, Oba T, Takahashi K, Tampo Y. Methylglyoxal causes dysfunction of thioredoxin and thioredoxin reductase in endothelial cells. J Phar Sci. 2009;111(4):426–432. doi: 10.1254/jphs.09131FP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toppo S, Vanin S, Bosello V, Tosatto SC. Evolutionary and structural insights into the multifaceted glutathione peroxidase (Gpx) superfamily. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2008;10(9):1501–1514. doi: 10.1089/ars.2008.2057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tripathi DK, Singh S, Singh S, Pandey R, Singh VP, Sharma NC, Chauhan DK. An overview on manufactured nanoparticles in plants: uptake, translocation, accumulation and phytotoxicity. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2017;110:2–12. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2016.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vivancos PD, Wolff T, Markovic J, Pallardó FV, Foyer CH. A nuclear glutathione cycle within the cell cycle. Biochem J. 2010;431(2):169–178. doi: 10.1042/BJ20100409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Q, Su N, Chen Q, Shen W, Shen Z, Xia Y, Cui J. Cadmium-induced hydrogen accumulation is involved in cadmium tolerance in Brassica campestris by reestablishment of reduced glutathione homeostasis. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(10):e0139956. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0139956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yadav SK, Singla-Pareek SL, Reddy MK, Sopory SK. Transgenic tobacco plants overexpressing glyoxalase enzymes resist an increase in methylglyoxal and maintain higher reduced glutathione levels under salinity stress. FEBS Lett. 2005;579(27):6265–6271. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yousuf PY, Hakeem KUR, Chandna R, Ahmad P. Role of glutathione reductase in plant abiotic stress. In: Prasad MNV, editor. Abiotic Stress Responses in Plants: Metabolism, Productivity and Sustainability. New York: Springer New York; 2012. pp. 149–158. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou ZS, Guo K, Elbaz AA, Yang ZM. Salicylic acid alleviates mercury toxicity by preventing oxidative stress in roots of Medicago sativa. Environ Exp Bot. 2009;65(1):27–34. doi: 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2008.06.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zouari M, Ahmed CB, Zorrig W, Elloumi N, Rabhi M, Delmail D, Abdallah FB. Exogenous proline mediates alleviation of cadmium stress by promoting photosynthetic activity, water status and antioxidative enzymes activities of young date palm (Phoenix dactylifera L.) Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2016;128:100–108. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2016.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.