Abstract

Nucleoside analogues acyclovir, valaciclovir, and famciclovir are the preferred drugs against human Herpes Simplex Viruses (HSVs). However, the viruses rapidly develop resistance against these analogues which demand safer, more efficient, and nontoxic antiviral agents. We have synthesized two non-nucleoside amide analogues, 2-Oxo-2H-chromene-3-carboxylic acid [2-(pyridin-2-yl methoxy)-phenyl]-amide (HL1) and 2-hydroxy-1-naphthaldehyde-(4-pyridine carboxylic) hydrazone (HL2). The compounds were characterized by different physiochemical methods including elementary analysis, FT-IR, Mass spectra, 1H–NMR; and evaluated for their antiviral efficacy against HSV-1F by Plaque reduction assay. The 50% cytotoxicity (CC50), determined by MTT test, revealed that HL1 (270.4 μg/ml) and HL2 (362.6 μg/ml) are safer, while their antiviral activity (EC50) against HSV-1F was 37.20 μg/ml and 63.4 μg/ml against HL1 and HL2 respectively, compared to the standard antiviral drug Acyclovir (CC50 128.8 ± 3.4; EC50 2.8 ± 0.1). The Selectivity Index (SI) of these two compounds are also promising (4.3 for HL1 and 9.7 for HL2), compared to Acyclovir (49.3). Further study showed that these amide derivatives block the early stage of the HSV-1F life cycle. Additionally, both these amides make the virus inactive, and reduce the number of plaques, when infected Vero cells were exposed to HL1 and HL2 for a short period of time.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s13205-023-03658-0.

Keywords: Amide derivative, Herpes Simplex Virus, Cytotoxicity, Antiviral, Plaque assay

Introduction

Among the human viruses Herpes Simplex Virus type-1 (HSV-1) and type-2 (HSV-2) are the commonest pathogen (Cory et al. 2018). HSV-1 is typically transmitted through oral-to-oral or Oro-genital contact, causing oral herpes around the mouth (Chang et al. 1994) and or around the genitalia as genital herpes (McGeoch and Gatherer 2005). Herpes viruses can infect people of different ages for centuries, with HSV-1 being more prevalent than HSV-2 (Cory et al. 2018). After establishing the initial infection, the HSV virion retrogradely transported to ganglia and can remain dormant for an indefinite period or reactivate periodically, to cause recurrent infections (Whitley and Roizman 2001; Valyi-Nagy et al. 2007; Kather et al. 2010). One approach to develop antiviral drug is to identify agents that can either target the structural components of virions, or inhibit viral replication by blocking crucial interactions between the virus and host cells. Both HSV-1 and HSV-2 can target the Central Nervous System (CNS) and slowly replicate in nerve ganglia to initiate a latent infection, particularly in dorsal root ganglia (Kawaguchi et al. 2001). Latent genomes of HSVs can be activated at various times throughout the host’s life, resulting in lytic infections at primary infection site, causing skin sores, lesions, keratitis, or other mucocutaneous diseases (Cowan et al. 2003). Moreover, HSV often causes encephalitis or systemic infections in immune-compromised individuals, requiring antiviral drugs (Erlich 1997). Currently, the gold-standard anti-HSV drugs include nucleoside analogues acyclovir (ACV) and ganciclovir that specifically target the viral thymidine kinase (Elion 1989). These antivirals can heal skin lesions caused by HSV, usually within 4–5 days (Hull and Brunton 2010). However, when the thymidine kinase (TK) gene is modified (TKa), or the virion does not express functional TK as in the TK¯ virus, the impact and selectivity of nucleoside drugs are reduced as observed in immunocompromised patients (Falanga et al. 2021; Reyes 2003). Those TK− viruses have been treated by non-nucleoside pyrophosphate analogue foscarnet and deoxycytidine analogue cidofovir, both of which inhibit DNA-polymerase of HSV (Majewska and Mlynarczyk-Bonikowska 2022). Foscarnet is used to treat viral-retinitis, acyclovir-resistant HSV, Cytomegalovirus (CMV), and Varicella Zoster virus (VZV) infection (Razonable 2011), esophagitis or colitis, and allogeneic stem cell transplant (Razonable 2011; Wagstaff and Bryson 1994), either alone or in combination with ganciclovir or acyclovir. When those antivirals are ineffective alone or had strong side effects (Tan 2014) by selectively binding to the herpes virus DNA-polymerase that block the cleaving process to inhibit the DNA chain elongation (Poole and James 2018), although, it can inhibit human DNA polymerase at higher concentrations (Wagstaff and Bryson 1994). However, these antiviral drugs are neither able to stop the viral spread nor get rid of the virion from the host, may lead to viral resistance (Piret and Boivin 2011; Bag et al. 2013).

The 2-amino benzamide derivatives SNX-7081, SNX-2112, and SNX-25a exhibit significant anti-HSV activities through selective binding of the ATP binding pocket of N-terminus of HSV heat shock proteins (HSP90)’s at non-cytotoxic concentrations, in virus-infected Vero cells with an EC50 close to ACV (Xiang et al. 2012). Additionally, a ribosomally synthesized lantibiotic peptide Labyrinthopeptin-A1 had broad anti-HSV activity (Férir et al. 2013),while SNX-7081 and SNX-2112 gels are active at various dosages (Férir et al. 2013; Okawa et al. 2009). Two recent studies showed that inhibitors of Hsp90 stop HSV-1 proliferation by interacting with UL42-Hsp90 complex (Okawa et al. 2009), and controlling cofilin-mediated F-actin rearrangement to prevent HSV-1 entry to neuronal cells (Qin et al. 2022; Song et al. 2022). Pyridine derivatives are used in diverse therapeutic areas, and thus, many novel bioactive compounds with pyridine scaffolds have been synthesized. Pyridine moiety-enclosed natural products have also been effective against cancer (Tahir et al. 2021), while 5-[(3′-aralkyl amido/amino-alkyl)phenyl]-1,2,4-triazole [3,4-b]-1,3,4-thiadiazole have in-vitro antiviral activity against HSV-1 at 125–250 µg/ml; and Japanese Encephalitis virus at 7.8–125 µg/ml (Pandey et al. 2012). The high-throughput screening revealed that the iron-chelator 2-hydroxy1-naphthaldehyde isonicotinoyl hydrazone has anticancer, anti-plasmodial, and antiviral activities (Davison et al. 2009; John et al. 2016). Earlier studies revealed that the immunomodulators Imiquimod and Resiquimod can inhibit HSV DNA-polymerase,while Thiazolylphenyl and Thiazolylamide are inhibitors of HSV helicase (Kan et al. 2012). Another unique molecule 4-Hydroxyquinoline-3-carboxamide can prevent HSV-1 infection by inhibiting immediate-early (IE) and late (L) gene transcripts (Oien et al. 2002). Several novel compounds containing pyridine scaffolds have shown biological efficiency and anticancer activity (De et al. 2022) with diverse pharmacological properties. Moreover, Coumarins, both natural and synthetic, are reported to have antitumor, anticancer, and anti-microbial effects (Majnooni et al. 2019; Kawaii et al. 2001; Kawase et al. 2003; Liu et al. 2019). All the above studies have motivated us to synthesize pyridine derivatives HL1 and HL2, as promising anti-HSV candidates. This study, for the first time, is aimed to the synthesis, spectroscopic characterization, and biological significance of molecules condensed with coumarinyl and pyridyl groups as two non-nucleoside amide derivatives HL1 and HL2,with evaluation of their in vitro cytotoxicity and antiviral activity against HSV-1 along with the mode or mechanism of action.

Experiments

Materials and procedures

All aqueous solutions were made with Milli-Q water (Millipore). Coumaric acid, 2-(chloromethyl) pyridine hydrochloride, and tetrahydrofuran were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, India; while Thionyl chloride, Ethyl acetate, 2-Hydroxy-1-naphthaldehyde, Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) were obtained from E. Merck, Germany. A Perkin-Elmer LX-1 FTIR-spectrophotometer was used to capture the FTIR-spectra (KBr disc, 4000–400 cm−1), and a Bruker (AC) 300 MHz FT-NMR spectrometer to capture the NMR-spectra, utilizing TMS as an internal standard. The collection of ESI-Mass spectra was accomplished by using XEVOG2QTOF# YCA351 Spectrometer, Water HRMS model, and all measurements were carried out at 35–37 °C.

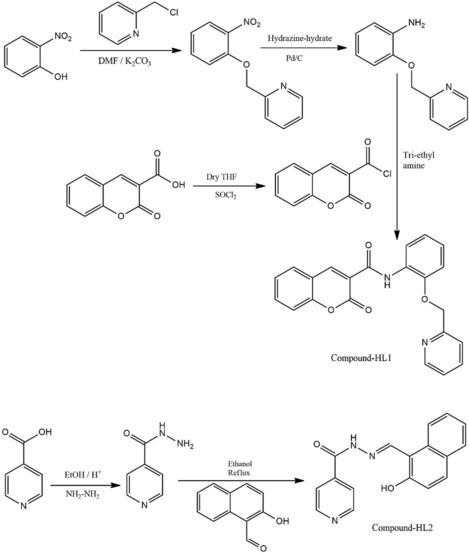

Synthesis of the compound HL2

Step-1: Coumaric acid (190 mg; 1 mM) was added in dry tetrahydrofuran (25 ml) in a round bottom (RB) 100 ml flask and mixed with one drop of DMF. Then thionyl chloride (SOCl2, 1.5 mM) was added drop-by-drop to this mixture, under cold condition, and refluxed for two hours. Cooling of the reactant was done at 35–37 °C, while vacuum evaporator was used for solvent evaporation. Finally, an acid chloride was collected from the solids.

Step-2: 2-Nitrophenol (139 mg, 1 mmol), K2CO3 (2 mmol) and 2-(Chloro-methyl) pyridine hydrochloride (164 mg) was mixed in an RB flask (100 ml), and then refluxed for 4 h. The mixture was filtered, dried in vacuum; and finally placed into ice-water. The product was added in ethyl ethanoate and was reduced by a mixture of Hydrazine-hydrate and palladium charcoal to get the desired product.

Step-3: One mmol of the compounds, each from both Step 1 and Step 2, were taken in an RB flask (100 ml) and mixed with tri-ethyl amine (1.2 mmol), and then agitated for one hour. A light yellowish-green precipitate was accumulated (yield 70%) as the product (Scheme 1). Micro-analytical data: C22H16N2O4; Calculated. (Found): C, 70.96 (70.92); H, 4.33 (4.36); N, 7.52 (7.57) %. NMR 1H (CDCl3, 400 MHz) δ:11. 390 (s, 1H), 9.020 (s, 1H), 8.59 (t, J = 6.4 Hz, 2H), 7.98 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 7.82 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 7.73 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H). 7.67 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 7.42 (t, J = 5.6 Hz, 2H), 7.07 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 7.02 (t, J = 8 Hz, 2H), 5.34 (s, 2H), 3.1 (s, 2H). (Fig. S1). 13C-NMR (20 mM; 75 MHz; CDCl3; δ, ppm): 161.39,159.23, 156.60, 154.55, 147.81, 137.14, 137.14, 134.24, 129.92, 127.77, 125.37, 124.67, 122.73 (2C), 121.44, 121.04, 119.01, 118.70, 116.61, 111.61, 71.18, 40.07, 30.89. (Fig S2). Mass: (M + Na) + 395.08 (Fig. S3). IR: 3454 cm−1 (amido, N–H), 1700 cm−1 (lactone C = O), 1602 cm −1 (amido, C = O) (Fig. S4).

Scheme 1.

Chemical synthesis of HL1 and HL2

Synthesis of HL2

Step-1: 2-Naphthol (2.1 g) and hexa-methylene tetramine (HMTA, 2.5 g) were heated in acetic acid (20 ml) at 60 °C. Then H2SO4 (98%, 4 ml) was added drop-wise to the above solution and the mix was refluxed for 10 h. The crude product was collected after cooling, added to the ice-water mixture, and then ethanol was recrystallized to produce a yellow solid with 82% yield.

Step-2: 2-Hydroxy-1-naphthaldehyde (0.86 g) and 4-pyridine carboxylic hydrazide (0.68 g) were refluxed in CH3CH2OH (30 ml) for 8 h under N2. After cooling to 37 °C the precipitate was collected, and the final product was recrystallized from ethanol to obtain a yellow solid (yield, 90%) (Scheme 1). Micro-analytical data: C17H13N3O2; Calcd. (Found): C, 70.09 (70.12); H, 4.50 (4.46); N, 14.42 (14.37) %. 1H NMR (DMSO-d6, 300 MHz) δ:12.54 (s, 1H), 12.42 (s, 1H), 9.49 (s, 1H), 8.94 (d, J = 5.7 Hz, 2H), 8.57 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 1H), 7.96 (d, J = 9 Hz, 2H). 7.90 (d, J = 1.8 Hz11, 1H), 7.89 (d, J = 1.5 Hz, 1H), 7.25 (d, J = 9 Hz, 1H), 7.43 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 7.64 (m, 1H) (Fig. S5). 13C-NMR (20 mM; 75 MHz; DMSO-d 6; δ, ppm): 161.481, 158.658, 150.938 (3C), 148.445, 140.254, 133.580, 132.078, 129.449, 128.320, 124.071, 121.901 (2C), 121.381, 119.291, 108.985 (Fig. S6). Mass: (M + Na)+ 314.14 (Fig. S7). IR: 3427.79 cm−1 (aromatic -OH), 1678.84 cm−1 (amido C = O), 1623 cm−1 (Schiff’s bass C = N) (Fig. S8).

Viruses and the cell line

Vero cells (ATCC) were maintained and cultured in fresh DMEM with 10% FBS (Invitrogen), using 100 µg/ml streptomycin and 100 Unit/ml penicillin at 37 °C in 5% CO2. Standard strain of HSV-1F (ATCC VR-733) was used as stock virus. The virus was produced after plaque purification, and the virus stocks were kept at − 80 °C in cryovials for future use. When necessary, the stocks of the virus were grown on Vero cells to measure the titre(s) by plaque assay and used for further work (Bag et al. 2013).

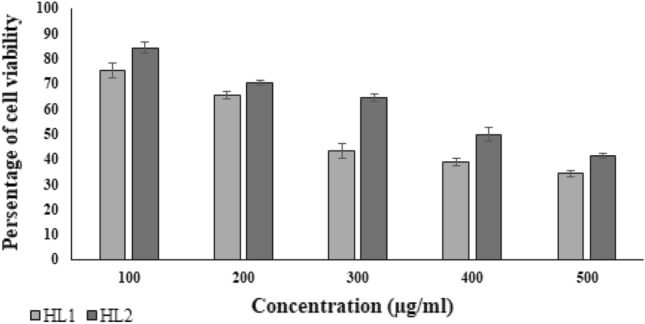

Determination of cytotoxic concentration (CC50)

The cellular toxicity of HL1 and HL2 was determined by assessing the morphology of untreated and compound- treated Vero cells. Monolayers of Vero cells were cultivated onto ninety-six well plates at 1.0 × 105 cells per well. Different concentrations of HL1 and HL2 and the reference drug ACV were added to each culture well, in triplicate, at a final volume of 100 µl, following a 6-h incubation at 37 °C in 5% CO2. A negative control (DMSO 0.1%) was used in place of the standard drug. The treated cells were incubated for two days at 37 °C in 5% CO2, and after the incubation period, each well was exposed to 10 µl of MTT reagent, and incubated at 37 °C for 4 h. The resultant formazan was then solubilized by adding diluted HCl (0.04N), and an ELISA reader was used to measure the absorbance at 570 nm with a reference wavelength of 690 nm. The viable cell percentage was calculated by the equation:

The 50% cytotoxic concentration (CC50) that causes obvious morphological alterations in 50% of Vero cells was calculated in comparison to the cell control (Bag et al. 2013, 2014).

Determination of Antiviral activity by Plaque reduction assay

The antiviral potential of HL1 and HL2 against HSV-1F was evaluated by standard Plaque reduction assay. Monolayers of 1.0 × 105 Vero cells per well were plated onto ninety-six well culture plates. The monolayers were then exposed to the virus (MOI 0.5) and incubated for one hour to allow viral adsorption, followed by 4–6 h incubation at 37 °C in 5% CO2. Then HL1 and HL2 were added to the culture well at 25, 50, 100, 150, and 200 µg/ml in triplicate, at the final volume of 100 µl. DMSO (0.10%) was added into the marked wells, as a negative control. Following three days of incubation at 37 °C with five present CO2, the plaque assay was conducted (Bag et al. 2014).

Molecular Docking study

Molecular docking is a tool to study the small molecules–protein interaction, identification of potential inhibitor(s), and evaluation of the potency and toxicity of the molecules. The information can help to find a pharmacophore against the target protein, identify the best target, and understand protein inhibition mechanisms through the analysis of interactions (Sharma et al. 2022; Sepay et al. 2021). Energy-minimized structures of HL1/HL2 as well as viral glycoprotein B (gB) and glycoprotein D (gD) were used to analyse the extent of interaction using AutoDock Vina. DFT calculation was used for energy minimization of ligands and Acyclovir. Here, B3LYP functional and 6-311G basis set was employed to get energy minimized structure of HL1/HL2 and ACV. Protein Data Bank provided the structural coordinates for gB (PDB ID: 5v2s) (Cooper et al. 2018) and gD (2c36 for gD) (Honess and Roizman 1975). For gB, a 126 × 126 × 126 grid box at x = 59, y = − 34, z = 125 was selected, and for gD, it was 60 × 60 × 60 grid box at x = 55, y = 37, z = 85. The results of the docking study were presented by Chimera 1.10.2 and Discovery Studio 4.1 Client.

Dose–response study by using Plaque reduction assay

Vero cells plated in 6-well plates at a density of 5 × 106 cells/well, were exposed to the serial dilutions of the test molecules HL1 and HL2 (0–200 µg/ml) for 15 min at 37 °C. Then, HSV-1 (hundred PFU/well) virion was added in the wells and exposed for 1 h. The unabsorbed virus and compounds were subsequently removed from the wells by washing the cells with PBS twice, and overlaid with different dilutions of the test compounds. The supernatant was removed after an additional 72 h of incubation, the wells were fixed with methanol and then stained with Giemsa (Sigma, USA). The viral inhibition (%) was calculated as:

where “Plaque(s) count in Exp” indicates the plaque counts from virus infection, treated with test compound(s); and “Plaques count in Control” indicates the number of plaques derived from virus (HSV-1F)-infected cells, with control (DMSO) treatment (Bag et al. 2014). The 50% effective concentration (EC50) for antiviral activity was provided as the concentration of the antiviral compound that produced 50% suppression of the virus-mediated plaque formation (Kawase et al. 2003).

Virus attachment and internalization/penetration study

In order to examine the potential impact of the test compounds HL1 and HL2 on viral attachment, a series of experiments were conducted using Vero cell monolayers in six-well plates. The pre-chilled Vero cells were at 4 °C for 1 h were plated at a density of 106 cells/well and exposed to HSV-1F (100 PFU/well), along with HL1 and HL2 at 100 µg/ml, ACV at 5.0 µg/ml, or DMSO at 0.1% for 3 h at 4 °C for virus binding. Following incubation, the wells were washed twice with chilled PBS to eliminate unbound virus particles and to facilitate the formation of plaques the cells were overlaid with 1% methylcellulose. After a 72-h incubation the resulting viral plaques were stained and enumerated. For viral penetration, Vero cells were pre-chilled at 4 °C for 1 h and subsequently exposed to HSV-1F at 100 PFU/well for 3 h at 4 °C, facilitating viral adsorption. The infected cells were then treated with the HL1 and HL2 at 100 µg/ml, DMSO at 0.1%, or ACV at 5.0 µg/ml for another 20 min at 37 °C, to enable viral penetration. Then the extracellular non-penetrated viral particles were neutralized by citrate buffer (pH 3.0) for 1 min, the cells were washed in PBS and overlaid to support plaque formation. Following a 72-h incubation period at 37 °C the resulting viral plaques were stained and quantified, as described by Bag et al. (2013).

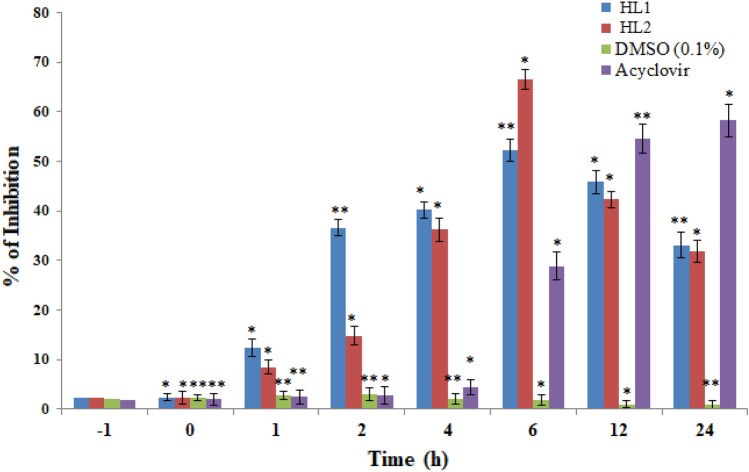

Time response assay

Time response assay was performed to study the mechanism for preventing HSV-1F infection by HL1 and HL2 at diverse time intervals, till 12 h. Vero cell monolayers were seeded in 96-well plates and were treated with HL1 or HL2 (100 µg/ml) for 24 h (long term) or one hour (short term); and then washed with PBS, before inoculating with HSV-1F (MOI: 1) in DMEM (pre-infection). To study the combined effect of the test molecules and virus, Vero cell monolayers were treated simultaneously with HSV-1F (MOI: 1), HL1 and HL2 (100 µg/ml) or ACV (5 µg/ml). After one-hour incubation at 37 °C, the compound-virus mixture was removed, and cells were washed before overlay with media (Co-infection). To evaluate whether the test molecules had any effects after viral entry to the host-cell, Vero cells were exposed to HSV-1F for 1 h, and washed to remove viral inoculum. The infected cells were re-washed and subsequently overlaid with media containing the test agents HL1 and HL2 (100 µg/ml) or ACV (5 µg/ml) as post-infection. For continuous compound treatment, cells were pre-treated for 1 h with HL1 or HL2, mixed with HSV-1F, and overlaid with media containing the test compounds after viral entry (Throughout infection). For all of the above experiments, assays were carried out following a total incubation of 48 h post-infection (p.i.). In each experiment the DMSO (0.1%) treatment was included as a control (Liu et al. 2019; Bag et al. 2014).

Quantification of viral mRNA expression, untreated or treated with test agents

The HSV-1F infected Vero cells were first exposed to test agents HL1 and HL2 (2 × EC50) for 1 h, 2 h, 4 h, 6 h and 8 h pre-infection and co-infection, respectively. While for post-infection study HL1 and HL2 were added to HSV-1F treated Vero cells at 2, 4 and 6 h post-infection, so that the cells were exposed to HL1/HL2 for 2–8 h, 4–8 h, and 6–8 h p.i. respectively. Following manufacturer's instructions, the RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen, Germany) was used to purify the RNA of virus-infected or uninfected cells treated or untreated with test compound(s), 8 h after the infection. The Revert Aid First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Thermo Scientific, USA) was used to convert cDNA from total RNA (0.1 mg/ml) in RNase-free water with 20 µl of RT-mix using a PCR (BIORAD Thermocycler). The qPCR was carried out with those products in triplicate in an ABI Prism 7000 sequence detection system, using SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Qiagen, Germany), as per manufacturer instructions (Applied Biosystems, CA, USA), setting as: 40 cycles of 15 s at 95 °C, and 60 s at 60 °C during the course of an initial 10 min of denaturation at 95 °C (Liu et al. 2019; Bag et al. 2014). The primer sequences used in this study was displayed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Primer lists

| Serial no | Name of gene | Sequences of primer | Tm |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | GAPDH |

F-5′GAGAAGGCTGGGGCTCATTT-3′ R-5′GCTGACGATCTTGAGGCTGT-3 |

59.4 59.4 |

| 2 | ICP4 HSV-1 |

F-5′GGCGACGACGACGATAAC-3′ R-5′-CGAGTACAGCACCACCAC-3′ |

58.2 58.2 |

| 3 | ICP8 HSV-1 |

F-5′-GCTCGGACAAGGTAACCATAG-3′ R-5′-CACGAGGAAGAAGCGGTAAA-3′ |

55.7 53.7 |

| 4 | gB HSV-1 |

F-5′-GGAACACAAGGCCAAGA-3′ R-5′-GTTGGGAACTTGGGTGT-3′ |

57.3 57.9 |

| 5 | DNA Pol HSV-1 |

F-5′GAACATCGACATGTACGGGATTA-3′ R-5′-GGTCCTTCTTCTTGTCCTTCAG-3′ |

58.9 60.3 |

Statistical analysis

Results were presented as SEM (n = 6), using one-way variance of analyses (ANOVA) before Dunnett's test. In comparison to the control, a value of p < 0.05 was accepted as statistically significant.

Results

The characterization of HL1 and HL2.

The 1H NMR spectrum of HL1 shows a singlet at 11.39 ppm, which corresponds to the N–H proton of the amido linkage (Fig. S1). Other aromatic protons are observed at 9.02–7.02 ppm (Fig. S1). In HL2 the singlets are observed at 12.54 ppm (δ(O–H)), and 12.42 ppm (δ(N–H)); while imine-H have been assigned at 9.49 ppm (δ(N = C–H)), and other Hs are at 7.40–8.56 ppm, based on spin–spin interaction (Fig. S5). The molecular ion peak (M + Na)+ at 395.08 (HL1, Fig. S3) and 314.14 (HL2, Fig. S7) support the identity of these two compounds. In FT-IR spectra the stretching vibrations are found at 3454 cm−1 (amido, N–H), 1700 cm−1 (lactone C = O), and 1602 cm−1 (amido, C = O) refer to respective groups in HL1 (Fig. S4). Similarly, the stretching at 3427.79 cm−1 correspond to aromatic –OH, 1678.84 cm−1 for amido C = O), 1623 cm−1 for Schiff’s bass, and C = N of HL2 (Fig. S8).

Cell viability assay

The conventional MTT assay was used to evaluate the cytotoxicity of the test compounds HL-1 and HL-2 at various concentrations on Vero cells (Fig. 1). Fifty percent cytotoxic concentration (CC50) was calculated from the concentration that causes observable morphological changes in 50% of Vero cells, compared to cell Control (Fig. 1). The CC50 values for test compounds HL1 and HL2 were 270.40 µg/ml and 362.6 µg/ml respectively, indicating that HL1 is more cytotoxic than HL2. These findings revealed the safety of our test compounds HL1 and HL2 for potential biomedical applications.

Fig. 1.

Determination of cytotoxic concentration of HL1 and HL2

The morphological changes of Vero cells showing cytopathic effect of test agents including Vero cell control, HSV-1F-infected cells; and HSV-1-infected cells treated with HL1 and HL2 at their EC50 concentrations as presented in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Morphological changes of an HSV-1F-infected Vero cell under inverted light microscope showing cytopathic effect (CPE) at CC50 doses of the test compounds HL1 and HL2. Uninfected Vero cells served as the cell control

Evaluation of anti-HSV-1 activity of HL1 and HL2 by plaque reduction assay

In this study, the efficacy of the test compounds HL1 and HL2 was evaluated during viral replication by adding them at different stages of the virus life cycle (pre-infection, co-infection, and post-infection), via MTT assay and confirmed by Plaque reduction assay. The results showed that our test compounds HL1 and HL2 were ineffective to protect Vero cells pre-infected with HSV-1F. However, when the test-compounds were administered during co-infection, or immediately after viral entry, both HL1 and HL2 effectively prevented the cytopathic effect (CPE) and plaque number at EC50 of 63.4 ± 3.0 and 37.2 ± 2.8 µg/ml with selectivity index (SI) of 4.3 and 9.7, compared to Acyclovir with EC50 of 2.8 ± 0.1 and SI of 49.3 (Table 2). Collectively, the findings indicate that HL1 and HL2 may be useful in preventing the infection caused by HSV-1F and reducing the corresponding adverse effects of infection.

Table 2.

Assessment of anti-HSV-1F activity of HL1 and HL2

| Test compound | CC50a | EC50b | Selectivity indexc |

|---|---|---|---|

| HL2 | 362.6 ± 2.5 | 37.2 ± 2.8 | 9.7 |

| HL1 | 270.4 ± 3.2 | 63.4 ± 3.0 | 4.3 |

| Acyclovir | 128.8 ± 3.4 | 2.8 ± 0.1 | 49.3 |

aCC50 of HL1 and HL2 in Vero cells at µg/ml

b50% reduction of virus mediated toxicity by HL1 and HL2 (µg/ml)

cSelectivity Index (SI) = CC50 × (1/EC50)

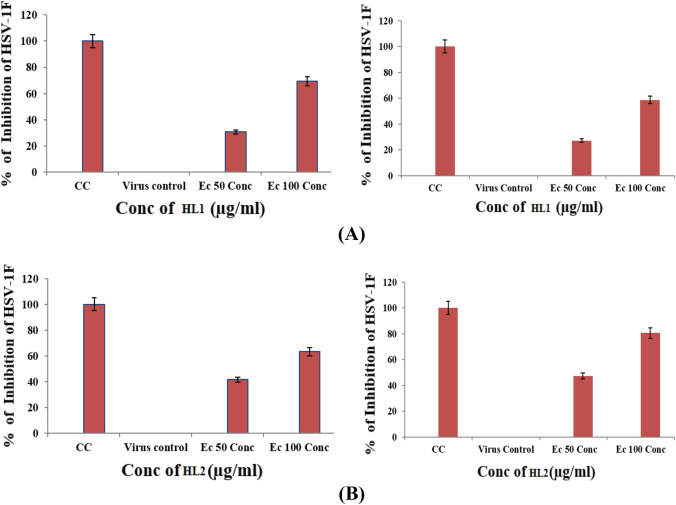

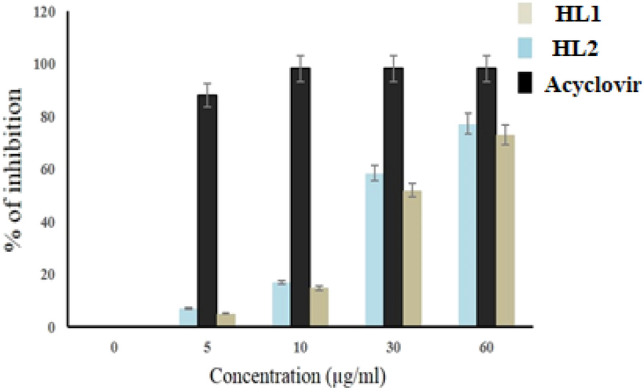

Dose–response assay of HL1 and HL2

The monolayers of Vero cells (1.0 × 106 cells/ml) grown onto 96 well plates were infected with HSV-1F (1.0 MOI) and incubated at 37 °C in 5% CO2 for 1 h to facilitate viral adsorption. HL1 or HL2 was added (0–60 µg/ml) to culture wells at final volume of 100 µl in triplicate, using DMSO (0.1%) and acyclovir (0–5 µg/ml) as control. After 3 days of incubation at 37 °C in 5% CO2, the MTT test was carried out (Bag et al. 2013). The results depicted in Fig. 3, revealed that ACV at 5.0 µg/ml can inhibit about 90% of the virion, while HL1 inhibit about 70% virus at 60 µg/ml. However, HL2 demonstrated better activity that HL1, both at 60 µg/ml. Thus, HL2 revealed better antiviral potential than its counterpart, compared to ACV at 5.0 µg/ml (Fig. 3), indicating better correlation of test molecules concentration vs viral inhibition rate.

Fig. 3.

Dose–response Assay of test compounds HL1, HL2 and Acyclovir against HSV-1F

Molecular docking study

The results of the docking study showed that HL2 has a better binding affinity toward viral proteins than HL1. The binding energy of standard antiviral ACV with viral glycoproteins gB and gD was found to be − 6.1 and − 6.6 kcal mol−1, respectively. The change of free energy during HL1 interaction with gB and gD were − 7.5 and − 7.7 kcal mol−1, respectively; whereas it was − 8.3 and − 8.2 kcal mol−1 for HL2. Therefore, HL2 is a better inhibitor of these two envelop proteins of HSV-1 than that of HL1. Moreover, the HL2 can interact with both the glycoproteins with almost equal efficiency. The working unit of viral glycoprotein gB consists of three identical peptide chains (Red, Blue, and Green) attached through self-assembly (Fig. 4a) in three-fold symmetry, and our docking results demonstrated that HL2 can bind at the Ecto-region of the glycoproteins (Fig. 4b) through conventional and non-conventional H-bond. Here, only one H-bond was observed between the oxygen of phenolic OH and H–N of I114 residue. The aromatic C-H close to pyridyl-N is involved in C = O…H–C type of non-conventional H-bond with three Q101 residue of each chain (Fig. 4b). Due to three identical peptide chains with three-fold symmetry the HL2 binding region have amino acids with same position number, as present in the Fig. 4b. Similar interactions were also observed between imine C–H and C = O of I114. In gD, the test compounds bind at the surface near the C-terminal region (Fig. 4c); while Hydrogen bonding is observed between pyridyl-N of HL2 and S276, as well as Q278 individually, along with the amide C = O of HL2 and I202 residue (Fig. 4d). However, the P275 residue involved in the hydrophobic interaction with pyridine ring. The ortho-hydrogen of pyridine nitrogen showed to interact with H273, I274, and D279 residues, via non-conventional H-bond. Another non-conventional H-bond was involved between amide C = O and F201. It is interesting to note that the binding energy of HL2 with the investigated proteins are different, due to the microenvironment and the number of residues interacting with test molecules. Further, we observed only one H-bond between I114 and HL2, that stabilizes the molecule in the gB protein. However, in gD, there are four H-bonds. Moreover, residues Q5, F201, S276 and Q278 are involved in H-bond with HL2. Therefore, the role of these residues to the binding of test compounds to gD is significant.

Fig. 4.

Docking pose of HL2 in gB (a); interactions between amino acids of gB and HL2 (b); docking pose of HL2 in gD (c); and interactions between amino acids of gD and HL2 (d). Three identical peptides with three-fold symmetry (e)

The time of-addition assay

This study aimed to determine which step of the viral life cycle is affected by the test compounds HL1 and HL2. Virus adsorption was measured by incubating HSV-1F (100 plaque forming unit/well) with the prechilled (1 h, 4 °C) Vero cell monolayer (1 × 106 cells/well) on a six-well plate at 4 °C for 3 h. Our results demonstrated that both compounds can prevent plaque formation when added during virus adsorption and in the early stages of viral replication, after entry (Fig. 5). Further, HSV-1F infection was severely hindered when test compound(s) interact at the time of infection, suggesting that the antiviral activity of HL1 and HL2 are not due to their direct effects on Vero cells, but on the viral particles, which may hinder virion’s ability to establish infection after host-cell entry. Our results also revealed that both HL2 (37.2 µg/ml) and HL1 (63.4 µg/ml) significantly inhibited HSV-1 within 1–6 h post-infection, indicating that the effect of test compounds at an early stage of virus infection (Fig. 5). However, both HL1 and HL2 were unable to inhibit the virus attachment/penetration or growth during pre-infection or co-infection.

Fig. 5.

The inhibitory effect of HL1 and HL2 (EC50) on Vero cells infected with HSV-1F during Pre-infection (− 1 h), Co-infection (0 h), or post-infection (2–6 h), after 3 days by MTT assay, followed by Plaque-reduction assay; and represented as the rate of inhibition/suppression of infection

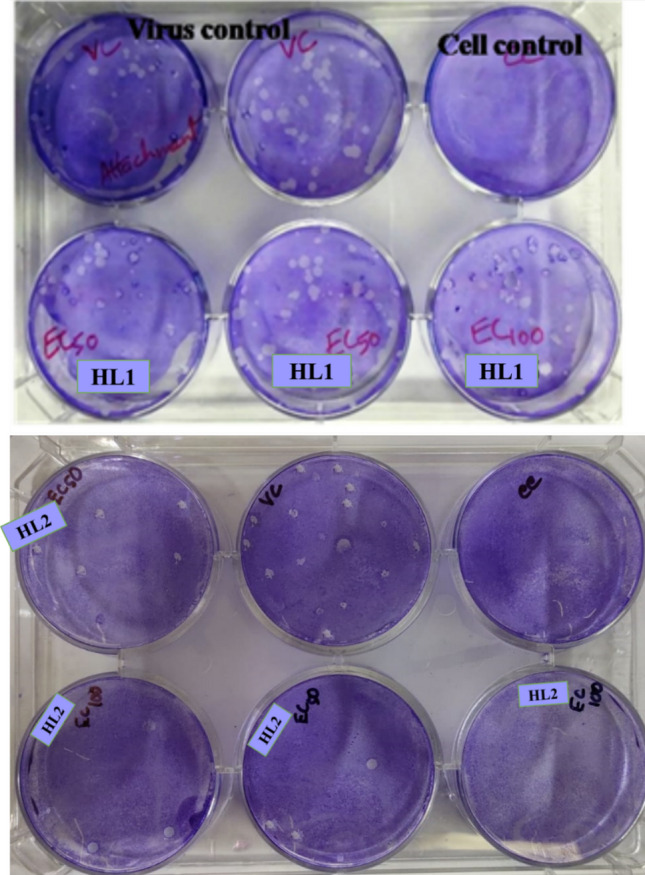

Attachment and internalization/penetration in absence or presence of HL1 and Hl2

To investigate the antiviral mechanism of action of HL1 and HL2 on HSV-1F, we conducted a direct virus inactivation assay. The results demonstrated that HL1 and HL2 significantly inhibit the infectivity of HSV-1F when added at doses of EC50 and EC100, followed by a 1-h incubation period (Fig. 6). This suggests that HL1 and HL2 bind to virus particles and thereby neutralize the virion infectivity. The reduction in plaques number, presented in Fig. 6, was nearly similar to the direct treatment, suggesting that the test compounds may influence attachment of the virion. In a parallel experiment, cells were incubated with HSV-1F for 3 h at 4 °C, then added with HL1 or HL2, and kept at 37 °C for internalization. Further incubation for 20 min at 37 °C, and then treated at low pH can inactivate the virions attached on the cell surface. We also perform a time-of-addition assay to explore antiviral activity of test compounds, by determining its impact on different stages of HSV-1 life cycle, specifically, on virus attachment and penetration events. However, the results (Fig. 7A and B) indicated that HL1 and HL2 did not exert any effect on HSV-1F attachment or penetration, indicating that HL1 and HL2 has antiviral activity primarily through virus inactivation, rather than interfering with attachment or penetration processes.

Fig. 6.

Representative Photograph showing the plaque reduction assay in presence or absence of HL1 and HL2, during virus Attachment/ and internalization/Penetration

Fig. 7.

Effect of HL1 (A) and HL2 (B) on the entry of HSV-1F in Vero cells by virus Attachment/ and internalization/ Penetration assay

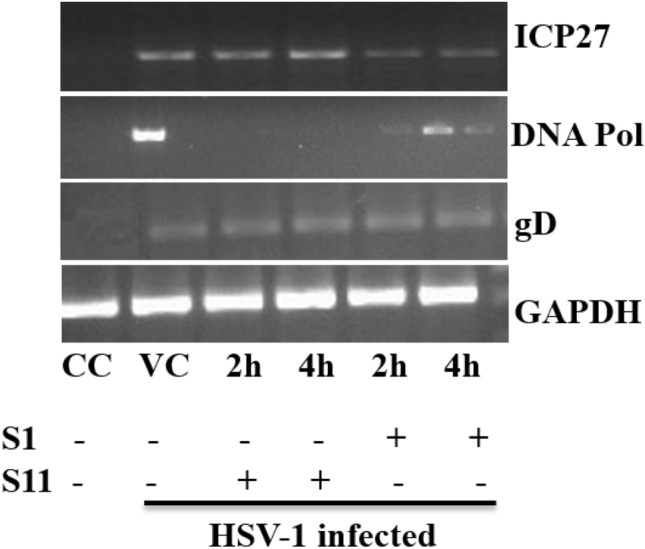

Effect of test compounds on gene expression of HSV-1

To determine whether HL1 and HL2 treatment on virus-infected Vero cell can inhibit early replication of HSV-1, we have assessed the expressions of four major proteins, in the untreated or compound-treated virus-infected or uninfected cells, including viral ICP4, ICP27, DNA-polymerase, and envelope glycoprotein gD in pre-treatment (1–8 h), co-treatment and post-treatment (2–6 h) time. The kinetic study reported that the peak rate of synthesis of immediate-early (IE/α) genes takes place between 2 and 4 h (Honess and Roizman 1975), early genes (E/β) between 6 and 12 h, and late genes (L/γ) at 10–16 h post-infection (Roizman et al. 2013). However, each viral genes have different time-points to reach a peak during transcription (Ibáñez et al. 2018), and IE transcript ICP4 usually express at 1–2 h,while transcript ICP27 and DNA-pol after 4 h (Krummenacher et al. 2005; Mandal et al. 2021). Thus, we have isolated the RNA from virus-infected HL1 and HL2 treated or untreated cells after 8 h post-infection, and thus, a time-point of 8 h was selected for the detection of IE, E, and rising quantities of L-transcripts. The inhibition of attachment and/or internalization of virions by HL1 and HL2 may be prevented by interfering with the surface receptor of host-cell or by direct neutralization of the virus, as evident from the time-of-addition assay and gene expression analysis. The PCR results displayed that the mRNA expression of compound-treated virus was diminished by HL1 and HL2. After pre-treatment, DNA transcripts were drastically decreased by co-treatment with the test compounds HL1 and HL2, while 2–8 h post-treatment had little effect, as the reduction of viral plaques (pfu/ml) was insignificant (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8.

Role of HL1 and HL2 on HSV-1F-induced expression of gD, DNA-polymerase, and ICP27, isolated from uninfected and HSV-1 infected Vero cells. Lane 1: Control cell; Lane 2: HSV-1F + Cell; Lane 3, 4: HSV-1F + Cells + HL2 at 2 h and 4 h post-infection; Lane 5, 6: HSV-1 + Cells + HL1 at 2 h and 4 h after-infection. Data from three studies with similar findings are expressed as Mean SEM (*P 0.05; **P 0.01)

Further, the effect of HL1 and HL2 on expression of viral mRNA has been studied after the entry of HSV-1F, to address the consequences of time-of-addition. Our goal was to evaluate the effects of compounds on the expression of viral mRNA, following the entry of HSV-1F. Citrate buffer was used for 1 h to inactivate the HSV-1F virion in virus-infected Vero cells, followed by washing in PBS and exposing the cells to HL1 and HL2 at 1, 2, and 4 h post-inoculation. The results showed that test compounds HL1 and HL2 decreased the viral mRNA expression at 2 h and 4 h post-infection, as the IE gene transcript ICP27, early gene DNA-Pol, and late gene transcripts gD failed to express in presence of test agents, while the gene expression at 1 h was negligible. These results collectively indicated that both HL2 and HL1 inhibit HSV-1 transcription in the initial stages of HSV-1F life cycle, after host cell penetration/entry.

Discussion

The HL2 and HL1 required for 50% inhibition (EC50) of viral plaque or virus-mediated CPE was 37.20 µg/ml and 63.4 µg/ml; while 50% cytotoxic concentrations (CC50) were found to be at 362.6 µg/ml and 270.40 µg/ml, respectively. Thus, the selectivity index (SI = CC50 × 1/EC50) of HL2 and HL1 were 9.7 and 4.28. Both HL1 and HL2 contained pyridine moieties with amide linkage as a common structural part, indicating their potential for better anti-HSV activity. The earlier studies reported that several novel chalcone derivatives containing pyridine moieties had antiviral activities against Cucumber Mosaic virus at 500 μg/ml (Chen et al. 2019) , while 1, 5-benzothiazepine derivatives with pyridine moiety showed in vivo antiviral efficacy against Tobacco Mosaic virus (Li et al. 2017). Similarly, the synthesized pyridine thioglycosides have anti-HSV activity at an EC50 of 6.3 g/100 μl (Azzam et al. 2022). The herpes virus is primarily a lytic virus, as it kills the host-cell after infection by inhibiting cellular protein synthesis and DNA damage (Erukhimovitch et al. 2011; Meier et al. 2021). Interestingly, a lead drug PD146626 (9-(methyloxy)-3,4-dihydro-[1]-benzothieno[2,3-f]-[1],[4]-thiazepin-5(2H)-one), structurally similar to HL1 and HL2, prevents HSV-1 replication by blocking the expression of IE genes, especially VP16 and ICPO (Cohen 2020; Hamilton et al. 2002), predominantly inhibit RNA viruses. Moreover, the derivatives of indole, imidazole, thiazole, pyridine, and quinaxoline among the N- and S-containing heterocycles have antiviral properties supports our findings (De et al. 2021). It is worth mentioning here that heterocyclic compounds having pyridine backbone had broad-spectrum antiviral activities (Alizadeh and Ebrahimzadeh 2021). Comparing the basic structure of HL1 and HL2, containing either pyridine moieties or amide linkage or both, it was observed that these compounds have enhanced anti-HSV activities with reduced or a very low cytotoxicity. The pyridine ring present in both HL1 and HL2 may attribute to their antiviral activity, as pyridine-based molecules are known to have multiple biological potentials (Singh and Purohit 2023). Steered molecular dynamics, reported by Singh and Purohit, demonstrated the potential of protein–ligand interaction to create essential regulators of the CDK4/6, that control cell cycle progression (Singh and Purohit 2023). A recent computational study by Dhiman and Purohit (Dhiman and Purohit 2022) revealed that Serratiopeptidase, a metallo-endopeptidase, displayed many mutational hotspots during contact. Our results also showed that at 2 h and 4 h post-infection the quantities of mRNA transcripts of IE (ICP27), E (DNA-Pol), and L (gD) genes failed to express in HL1 and HL2 treated Vero cells,and additionally both HL1 and HL2 reduced viral mRNA replication. However, further studies are required to understand the exact mechanism of action of these compounds and for optimization of their therapeutic potential.

Conclusion

Design of more effective and less toxic or non-toxic cost-effective drugs, following a semi-synthetic sustainable method, is the current interest of scientists engaged in drug development. Herpes viruses, with time, have developed sophisticated survival tactics to evade host defense mechanisms. Heterocyclic compounds are considered as an important area in the field of Medicinal Chemistry because of their diverse bioactivities. Among these compounds pyridine derivatives are especially attractive. In this study we have synthesized two analogues pyridyl-hydrazide-chromone (HL1) and pyridyl-hydrazide-naphthol (HL2), and characterized these compounds spectroscopically. We observed significant anti-HSV-1 activity with no cytotoxicity, but acceptable selectivity index when these compounds were tested against HSV-1F. The compound HL2 was more active than HL1, which prevent the early stage of Herpes Simplex Virus infection by inhibiting the expression of IE gene products at 2–6 h post-infection. Further, our experimental data was verified by a computational study which support the antiviral potential of both the test compounds.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

ADM received a fellowship from the Department of Science & Technology (DST)-INSPIRE, Government of India; and a project under DC was financially supported by a research grant from the DST, Government of West Bengal [Memo 362 (Sanc.)/ST/P/S&T/9G-32/2014].

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

No conflict of interest exists, according to the authors.

Ethical statement

This research uses quality control strain of HSV-1 (ATCC), but no human subjects are involved, and thus there is no need to acquire any ethical approval.

Contributor Information

Chittaranjan Sinha, Email: crsjuchem@gmail.com.

Debprasad Chattopadhyay, Email: debprasadc@gmail.com.

References

- Alizadeh SR, Ebrahimzadeh MA. Antiviral activities of pyridine fused and pyridine containing heterocycles, a review (from 2000 to 2020) MRMC. 2021;21:2584–2611. doi: 10.2174/1389557521666210126143558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azzam RA, Gad NM, Elgemeie GH. Novel thiophene thioglycosides substituted with the benzothiazole moiety: synthesis, characterization, antiviral and anticancer evaluations, and NS3/4A and USP7 enzyme inhibitions. ACS Omega. 2022;7:35656–35667. doi: 10.1021/acsomega.2c03444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bag P, Ojha D, Mukherjee H. An indole alkaloid from a tribal folklore inhibits immediate early event in HSV-2 infected cells with therapeutic efficacy in vaginally infected mice. PLoS One. 2013;8:e77937. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0077937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Bag P, Ojha D, Mukherjee H, Halder UC, Mondal S, Biswas A, Sharon A, Van Luc K, Chakraborty S, Das G, Mitra D, Chattopadhyay D. A Dihydropyrido-indole potently inhibits HSV-1 infection by interfering with the viral immediate early transcriptional events. Antiviral Res. 2014;105:126–134. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2014.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang Y, Cesarman E, Pessin MS, et al. Identification of herpesvirus-like DNA sequences in HIV/AIDS-associated Kaposi’s Sarcoma. Science. 1994;266:1865–1869. doi: 10.1126/science.7997879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z, Li P, Hu D, et al. Synthesis, antiviral activity, and 3D-QSAR study of novel chalcone derivatives containing malonate and pyridine moieties. Arab J Chem. 2019;12:2685–2696. doi: 10.1016/j.arabjc.2015.05.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen JI. Herpesvirus latency. J Clin Invest. 2020;130:3361–3369. doi: 10.1172/JCI136225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper RS, Georgieva ER, Borbat PP, et al. Structural basis for membrane anchoring and fusion regulation of the herpes simplex virus Fusogen gB. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2018;25:416–424. doi: 10.1038/s41594-018-0060-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cory H, Passarelli S, Szeto J, et al. The role of polyphenols in human health and food systems: a mini-review. Front Nutr. 2018;5:87. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2018.00087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowan FM, French RS, Mayaud P, et al. Seroepidemiological study of herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2 in Brazil, Estonia, India, Morocco, and Sri Lanka. Sex Transm Infect. 2003;79:286–290. doi: 10.1136/sti.79.4.286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davison AJ, Eberle R, Ehlers B, et al. The order Herpesvirales. Arch Virol. 2009;154:171–177. doi: 10.1007/s00705-008-0278-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De A, Sarkar S, Majee A. Recent advances on heterocyclic compounds with antiviral properties. Chem Heterocycl Comp. 2021;57:410–416. doi: 10.1007/s10593-021-02917-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De S, Kumar SKA, Shah SK, et al. Pyridine: the scaffolds with significant clinical diversity. RSC Adv. 2022;12:15385–15406. doi: 10.1039/d2ra01571d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhiman A, Purohit R. Identification of potential mutational hotspots in serratiopeptidase to address its poor pH tolerance issue. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2022 doi: 10.1080/07391102.2022.2137699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elion GB. The purine path to chemotherapy. Biosci Rep. 1989;9:509–529. doi: 10.1007/BF01119794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erlich KS. Management of herpes simplex and varicella-zoster virus infections. West J Med. 1997;166:211–215. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erukhimovitch V, Bogomolny E, Huleihil M, Huleihel M. Infrared spectral changes identified during different stages of herpes viruses infection in vitro. Analyst. 2011;136:2818. doi: 10.1039/c1an15319f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falanga A, Del Genio V, Kaufman EA, et al. Engineering of Janus-Like dendrimers with peptides derived from glycoproteins of herpes simplex virus type 1: toward a versatile and novel antiviral platform. IJMS. 2021;22:6488. doi: 10.3390/ijms22126488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Férir G, Petrova MI, Andrei G, et al. The lantibiotic peptide labyrinthopeptin A1 demonstrates broad anti-HIV and anti-HSV activity with potential for microbicidal applications. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e64010. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton HW, Nishiguchi G, Hagen SE, et al. Novel Benzthiodiazepinones as antiherpetic agents: SAR improvement of therapeutic index by alterations of the seven-membered ring. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2002;12:2981–2983. doi: 10.1016/S0960-894X(02)00578-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honess RW, Roizman B. Regulation of herpesvirus macromolecular synthesis: sequential transition of polypeptide synthesis requires functional viral polypeptides. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1975;2:1276–1280. doi: 10.1073/pnas.72.4.1276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hull C, Brunton S. The role of topical 5% acyclovir and 1% hydrocortisone cream (Xerese™) in the treatment of recurrent herpes simplex Labialis. Postgrad Med. 2010;122:001–006. doi: 10.3810/pgm.2010.09.2216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibáñez FJ, Farías MA, Gonzalez-Troncoso MP, Corrales N, Duarte LF, Retamal-Díaz A, González PA. Experimental dissection of the lytic replication cycles of herpes simplex viruses in vitro. Front Microbiol (virology) 2018;9:Article 2406. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.02406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- John SF, Aniemeke E, Ha NP, et al. Characterization of 2-hydroxy-1-naphthaldehyde isonicotinoyl hydrazone as a novel inhibitor of methionine aminopeptidases from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Tuberculosis. 2016;101:S73–S77. doi: 10.1016/j.tube.2016.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kan Y, Okabayashi T, Yokota S, et al. Imiquimod suppresses propagation of herpes simplex virus 1 by upregulation of cystatin A via the adenosine receptor A1 pathway. J Virol. 2012;86:10338–10346. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01196-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kather A, Raftery MJ, Devi-Rao G, et al. Herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1)-induced apoptosis in human dendritic cells as a result of downregulation of cellular FLICE-inhibitory protein and reduced expression of HSV-1 antiapoptotic latency-associated transcript sequences. J Virol. 2010;84:1034–1046. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01409-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawaguchi Y, Tanaka M, Yokoymama A, et al. Herpes simplex virus 1 α regulatory protein ICP0 functionally interacts with cellular transcription factor BMAL1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:1877–1882. doi: 10.1073/pnas.98.4.1877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawaii S, Tomono Y, Ogawa K, et al. The antiproliferative effect of coumarins on several cancer cell lines. Anticancer Res. 2001;21:917–923. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawase M, Sakagami H, Hashimoto K, et al. Structure-cytotoxic activity relationships of simple hydroxylated coumarins. Anticancer Res. 2003;23:3243–3246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krummenacher C, Supekar VM, Whitbeck JC, et al. Structure of unliganded HSV gD reveals a mechanism for receptor-mediated activation of virus entry: structure of unliganded HSV gD. EMBO J. 2005;24:4144–4153. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li T, Zhang J, Pan J, et al. Design, synthesis, and antiviral activities of 1,5-benzothiazepine derivatives containing pyridine moiety. Eur J Med Chem. 2017;125:657–662. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2016.09.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu G, Wang C, Wang H, et al. Antiviral efficiency of a coumarin derivative on spring viremia of carp virus in vivo. Virus Res. 2019;268:11–17. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2019.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majewska A, Mlynarczyk-Bonikowska B. 40 years after the registration of acyclovir: Do we need new anti-herpetic drugs? IJMS. 2022;23(3):431. doi: 10.3390/ijms23073431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majnooni MB, Fakhri S, Smeriglio A, et al. Antiangiogenic effects of Coumarins against cancer: from chemistry to medicine. Molecules. 2019;24:4278. doi: 10.3390/molecules24234278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandal J, Das Mahapatra A, Mandal KC, Chattopadhyay D. An extract of Stephania hernandifolia, an ethnomedicinal plant, inhibits Herpes Simplex Virus-1 entry. Archiv Virol. 2021;166:2187–2198. doi: 10.1007/s00705-021-05093-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGeoch DJ, Gatherer D. Integrating reptilian herpesviruses into the family Herpesviridae. J Virol. 2005;79:725–731. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.2.725-731.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meier AF, Tobler K, Leisi R, et al. Herpes simplex virus co-infection facilitates rolling circle replication of the adeno-associated virus genome. PLoS Pathog. 2021;17:e1009638. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1009638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oien NL, Brideau RJ, Hopkins TA, et al. Broad-spectrum antiherpes activities of 4-hydroxyquinoline carboxamides, a novel class of herpesvirus polymerase inhibitors. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2002;46:724–730. doi: 10.1128/AAC.46.3.724-730.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okawa Y, Hideshima T, Steed P, et al. SNX-2112, a selective Hsp90 inhibitor, potently inhibits tumor cell growth, angiogenesis, and osteoclastogenesis in multiple myeloma and other hematologic tumours by abrogating signalling via Akt and ERK. Blood. 2009;113:846–855. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-04-151928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandey VK, Tusi Z, Tusi S, Joshi M. Synthesis and biological evaluation of some novel 5-[(3-Aralkyl Amido/Imidoalkyl) Phenyl]-1,2,4-Triazolo[3,4-b]-1,3,4-thiadiazines as antiviral agents. ISRN Org Chem. 2012;2012:760517. doi: 10.5402/2012/760517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piret J, Boivin G. Resistance of herpes simplex viruses to nucleoside analogues: mechanisms, prevalence, and management. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55:459–472. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00615-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poole CL, James SH. Antiviral therapies for herpesviruses: current agents and new directions. Clin Ther. 2018;40:1282–1298. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2018.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin S, Hu X, Lin S, et al. Hsp90 inhibitors prevent HSV-1 replication by directly targeting UL42-Hsp90 complex. Front Microbiol. 2022;12:797279. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2021.797279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Razonable RR. Antiviral drugs for viruses other than human immunodeficiency virus. Mayo Clin Proc. 2011;86(10):1009–1026. doi: 10.4065/mcp.2011.0309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyes M. Acyclovir-resistant genital herpes among persons attending sexually transmitted disease and human immunodeficiency virus clinics. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:76. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.1.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roizman B, Knipe DM, Whitley RJ. Herpes simplex viruses in fields’ virology. In: Knipe DM, Howley P, Griffin DE, Lamb RA, Martin MA, Racaniello VR, Roizman B, editors. Fields’ virology. New York: Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott-Williams and Wilkins; 2013. pp. 1840–1841. [Google Scholar]

- Sepay N, Saha PC, Shahzadi Z, et al. A crystallography-based investigation of weak interactions for drug design against COVID-19. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2021;23:7261–7270. doi: 10.1039/D0CP05714B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma B, Bhattacherjee D, Zyryanov GV, Purohit R. An insight from computational approach to explore novel, high-affinity phosphodiesterase 10A inhibitors for neurological disorders. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2022 doi: 10.1080/07391102.2022.2141895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh R, Purohit R. Computational analysis of protein-ligand interaction by targeting a cell cycle restrainer. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2023;231:107367. doi: 10.1016/j.cmpb.2023.107367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song X, Wang Y, Li F, et al. Hsp90 inhibitors inhibit the entry of herpes simplex virus 1 into neuron cells by regulating cofilin-mediated F-actin reorganization. Front Microbiol. 2022;12:799890. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2021.799890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tahir T, Ashfaq M, Saleem M, et al. Pyridine scaffolds, phenols and derivatives of Azo moiety: current therapeutic perspectives. Molecules. 2021;26:4872. doi: 10.3390/molecules26164872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan BH. Cytomegalovirus treatment. Curr Treat Options Infect Dis. 2014;6(3):256–270. doi: 10.1007/s40506-014-0021-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valyi-Nagy T, Shukla D, Engelhard HH, et al. Latency strategies of alphaherpesviruses: herpes simplex virus and varicella-zoster virus latency in neurons. In: Minarovits J, Gonczol E, Valyi-Nagy T, et al., editors. Latency strategies of herpesviruses. Boston: Springer US; 2007. pp. 1–36. [Google Scholar]

- Wagstaff AJ, Bryson HM. Foscarnet. A reappraisal of its antiviral activity, pharmacokinetic properties and therapeutic use in immunocompromised patients with viral infections. Drugs. 1994;48(2):199–226. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199448020-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitley RJ, Roizman B. Herpes simplex virus infections. The Lancet. 2001;357:1513–1518. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04638-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiang Y-F, Qian C-W, Xing G-W, et al. Anti-herpes simplex virus efficacies of 2-aminobenzamide derivatives as novel HSP90 inhibitors. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2012;22:4703–4706. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2012.05.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article.