Abstract

The aim of this study was to investigate the incidence, treatment and survival of patients with peritoneal metastases (PM) of unknown origin. All Dutch patients diagnosed in 2017 and 2018 with PM of unknown origin (PM-CUP) were evaluated. Data were extracted from the Netherlands Cancer Registry (NCR). Patients with PM-CUP were categorized into the following histological subtypes: 1) adenocarcinoma, 2) mucinous adenocarcinoma, 3) carcinoid, 4) unspecified carcinoma and 5) other. Treatments were compared between the different histological subtypes in patients with PM-CUP. Overall survival (OS) was calculated using the Kaplan–Meier method for all patients with cancer of unknown origin and between histological subtypes in patients with PM-CUP. Significant differences in OS were assessed by using the log-rank test. In total, 3026 patients were diagnosed with cancer of unknown origin, 513 (17%) among them were diagnosed with PM-CUP. Most PM-CUP patients received best supportive care only (76%), whereas 22% received systemic treatment and 4% underwent metastasectomy. Median OS was 1.1 months for all patients with PM-CUP but varied from 0.6 months to 30.5 months depending on the underlying histology. In this study, PM-CUP were diagnosed in 17% of all patients with cancer of unknown primary and the reported survival in this cohort was extremely poor. Since survival differed among histological subtypes and recently more treatment options became available for a selected group of patients with peritoneal malignancies, it is of great importance to identify the histology of the metastases and whenever possible the primary tumor.

Keywords: Peritoneal metastases, Cancer of unknown origin, Incidence, Histology, Treatment, Survival

Introduction

Peritoneal metastases (PM) are thought to be caused mainly by dissemination of tumor cells trough the abdominal cavity. As a result, relatively high incidences of PM are described from multiple primary intra-abdominal tumors such as colorectal, ovarian and gastric cancer [1–4]. However, PM may also be diagnosed in patients in whom the primary tumor site is unknown and remains unknown after initial workup [5, 6]. In approximately 3–5% of all patients diagnosed with metastatic cancer, the primary tumor location remains unknown [5–7]. In patients with metastases from an unknown origin, survival is generally poor [7, 8].

For long, PM were generally considered as incurable with only very few treatment options available. However, the amount of new treatment strategies for PM from a variety of primary tumors is currently expanding. Multimodal treatments such as cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (CRS-HIPEC) in a selected group of patients with PM from colorectal, ovarian or gastric cancer, have revealed promising results on survival in several studies [9–11]. In case of more extensive intraperitoneal disease not amendable for complete cytoreduction, alternative treatment options such as systemic therapy or chemotherapy applied intraperitoneally by pressurized intraperitoneal aerosol chemotherapy (PIPAC) or intraperitoneally administered chemotherapy (INTERACT) are currently being investigated [12–16]. This evolution in treatment options emphasizes the value of determining the primary tumor location in patients with PM whenever possible.

In PM from an unknown origin (PM-CUP), the underlying tumor histology differs among patients [5, 7]. This is important as PM from different tumor histologies may result in a different biological behavior and therefore require other diagnostic tools and treatment strategies. Thus, a better understanding of different histological subtypes in patients with an unknown primary tumor is warranted and may contribute to a more suitable approach in these patients.

Therefore, the aim of this study is to determine the incidence, treatment and survival of patients with PM-CUP and to gain more insight into the different histological subtypes of these patients.

Methods

Data source

For this nationwide cohort study, data were extracted from the Netherlands Cancer Registry (NCR). Specially trained data managers of the NCR routinely collect data on patient, tumor and treatment characteristics from medical records. For the specification of primary tumor location, location of metastases and histologic characteristics, the International Classification of Disease for Oncology (ICD-O) was used. The NCR provided follow-up information on vital status, which was obtained by linking NCR data to the municipal administrative database in which all deaths and emigrated inhabitants of the Netherlands are registered. The latest linkage with the municipal administrative database for the present study was January 31, 2020. Since all data were anonymized, no ethics approval was obligated for this study.

Study population

All patients diagnosed in 2017 and 2018 with cancer of unknown primary (C80.9) were screened for eligibility. Patients with PM-CUP were included for analyses. PM were defined according to the ICD-O (C48.0 – C48.2, C48.8). Patients with PM were subcategorized as follows: 1) isolated PM-CUP, which included all patients with only PM-CUP and 2) PM-CUP and systemic metastases, which included all patients with PM-CUP and concurrent other metastases. Patient and tumor characteristics included in this study are sex, age and histological subtype. The histology of the primary tumor was categorized into 1) adenocarcinoma (8140, 8144, 8310, 8380, 8441), 2) mucinous carcinoma (8480, 8481), 3) carcinoid (8240, 8249), 4) unspecified carcinoma (8000, 8001, 8010, 8020, 8012, 8032, 8041, 8046, 8070) and 5) other (8490, 8680, 8801, 8803, 8936, 8980, 8246, 8244, 8013, 8120, 8315, 8720). The treatments for patients with PM-CUP were defined as: 1) metastasectomy, 2) systemic treatment or 3) only best supportive care (BSC) and no tumor directed treatment. Within patients who underwent resection of metastases, resection of other metastases than the peritoneum was also included.

Statistical analysis

Proportion of frequencies was presented for patients with PM-CUP. Baseline characteristics of patients with isolated PM-CUP were compared to patients with PM-CUP and concurrent systemic metastases of unknown origin by means of the Chi-square test for categorical variables or unpaired T-test for continuous variables. All tests were two-sided and a p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Treatments were compared between the different histological subtypes in patients with PM-CUP by means of the Chi-square test.

Median overall survival (OS) was calculated using the Kaplan–Meier method for all patients with cancer of unknown origin and for patients with PM-CUP between the different histological subtypes. Significant differences in OS were assessed by using the Log-rank test. OS was calculated from time of diagnosis until death or loss to follow-up. All patients alive on January 31, 2020, were censored. All analyses were performed with SAS statistical software (SAS system 9.4, SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Study population

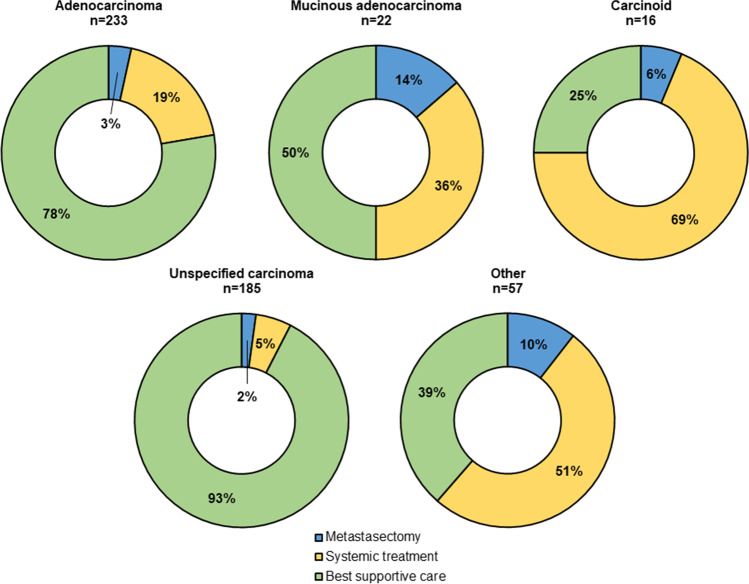

In 2017 and 2018, 3026 patients were diagnosed with cancer from an unknown primary origin. Among them, 513 (17%) patients had PM-CUP of which 160 (31%) presented with isolated PM-CUP and 353 (69%) presented with PM-CUP and concurrent systemic metastases of unknown origin (Fig. 1). In patients where the primary tumor location is unknown, the peritoneum ranks 5th as metastatic site after the liver (n = 1316, 43%), lymph nodes (n = 1178, 39%), lung (n = 870, 29%) and bone (n = 743, 25%). In patients with PM-CUP and concurrent systemic metastases of unknown origin (n = 353), in 156 patients (44%) 2 organs were involved (peritoneum and one other site), in 101 patients (29%) 3 organs were involved, in 67 patients (19%) 4 organs were involved, in 29 patients (8%) > 5 organs were involved. Baseline characteristics of PM-CUP patients are presented in Table 1. Patients with isolated PM-CUP were older and had more often a (mucinous) adenocarcinoma compared to patients with PM-CUP and concurrent systemic metastases of unknown origin.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of the study population

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients with peritoneal metastases of unknown origin

| Total PM-CUP | Isolated PM-CUP | PM-CUP and systemic metastases | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 513 | n = 160 | n = 353 | P value | |

| Sex, n (%) | ||||

| Male | 227 (44) | 70 (44) | 157 (44) | |

| Female | 286 (56) | 90 (56) | 196 (56) | 0.878 |

| Age, median (IQR) | 74 (66–82) | 78 (71–85) | 72 (64–80) | < 0.001 |

| Tumor histology, n (%) | ||||

| Adenocarcinoma | 233 (45) | 93 (58) | 140 (40) | |

| Mucinous adenocarcinoma | 22 (4) | 14 (9) | 8 (2) | |

| Carcinoid | 16 (3) | 1 (1) | 15 (4) | |

| Unspecified carcinoma | 185 (36) | 42 (26) | 143 (41) | |

| Other | 57 (11) | 10 (6) | 47 (13) | < 0.001 |

Percentages might not add up due to rounding; PM-CUP indicates peritoneal metastases of unknown origin; IQR indicates interquartile range

Treatments in PM-CUP

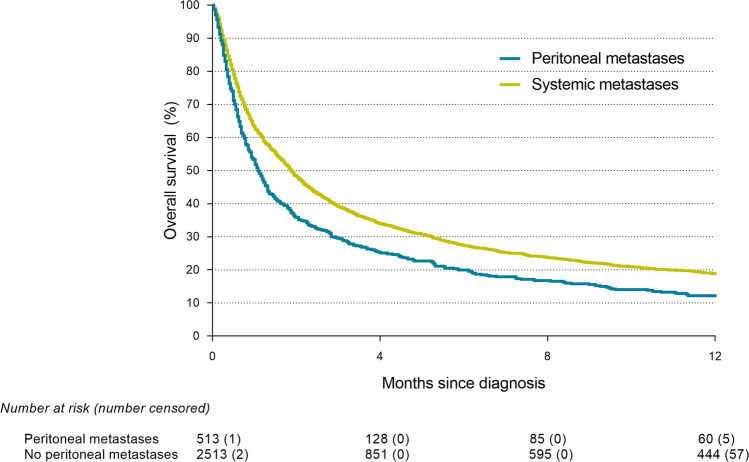

Of all PM-CUP patients, 22 (4%) patients underwent resection of metastases, 102 (20%) patients received systemic treatment and 389 (76%) patients received only BSC. In patients with isolated PM-CUP, 5 (3%) patients underwent resection of metastases, 25 (16%) patients received systemic treatment and 130 (81%) received only BSC and in patients with PM-CUP and concurrent systemic metastases of unknown origin, 17 (5%) patients underwent resection of metastases, 77 (22%) received systemic treatment and 259 (73%) patients received only BSC (p = 0.153). Figure 2 provides an overview of the applied treatments between the different histological subtypes within patients with PM-CUP. Treatments differed significantly between the histological subtypes (p < 0.001). Patients with mucinous adenocarcinoma more often underwent metastasectomy (14%) whereas patients with a carcinoid more often received systemic treatment (69%).

Fig. 2.

Treatments for patients with peritoneal metastases of unknown origin between the different histological subtypes

Survival of PM-CUP

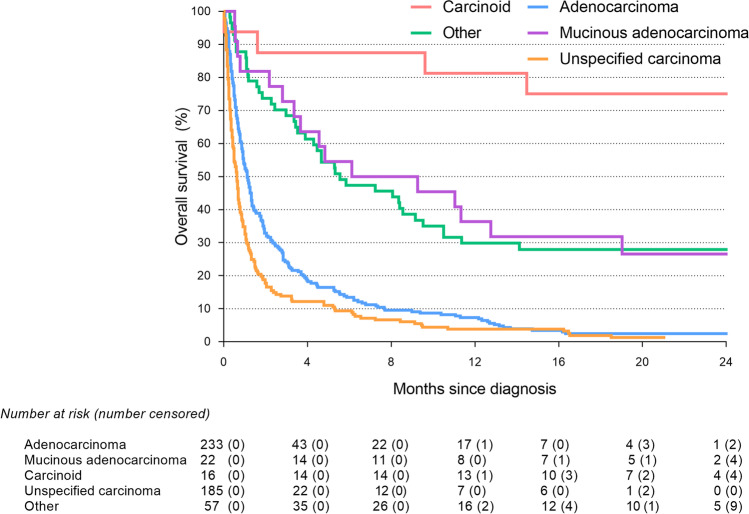

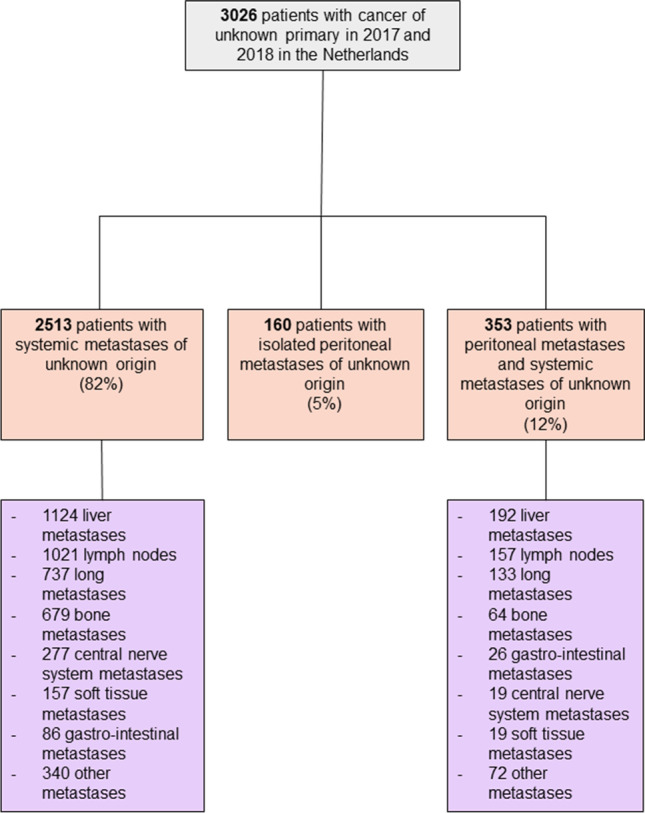

Median follow-up time in patients with PM-CUP was 4.2 months. Patients with PM-CUP had a significantly shorter OS (1.1 months, interquartile range [IQR] 0.4–4.0) as compared to patients with cancer of unknown origin without peritoneal involvement (1.9 months, IQR 0.6–7.1) (p < 0.001) (Fig. 3). Median OS did not differ significantly between the patients with isolated PM-CUP (1.1 months, IQR 0.5–3.8) as compared to patients with PM-CUP and concurrent systemic metastases of unknown origin (1.1 months, IQR 0.4–4.2) (p = 0.712). Median OS was significantly better in PM-CUP patients undergoing metastasectomy (8.2 months, IQR 3.9-not reached) or receiving systemic treatment (8.7 months, IQR 3.6–19.0) as compared to PM-CUP patients receiving only BSC (0.7 months, IQR 0.3–1.5) (p < 0.001). Median OS was 1.1 months (IQR 0.5–2.8) for PM-CUP patients with an adenocarcinoma, 7.7 months (IQR 2.8-not reached) for PM-CUP patients with a mucinous adenocarcinoma, 30.5 months (IQR 22.4-not reached) for PM-CUP patients with a carcinoid and 0.6 months (IQR 0.3–1.3) for PM-CUP patients with an unspecified carcinoma (p < 0.001) (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

Survival of patients with cancer of unknown primary (Log-rank: p < 0.001)

Fig. 4.

Survival of patients with peritoneal metastases of unknown primary between the different histological subtypes (Log-rank: p < 0.001)

Discussion

The present study showed that PM-CUP was diagnosed in 17% of all patients with an unknown primary tumor. Among these patients, 31% patients presented with isolated PM-CUP. To date, this is the highest reported incidence of PM-CUP in population-based studies [5, 6, 17].

We have previously shown that PM-CUP were diagnosed in 11% of all patients with an unknown primary tumor in a cohort diagnosed from 1984 and upwards. Previously published population-based studies reported an incidence of PM-CUP ranging from 9 to 13%, with 2012 as the most recent reported year [5, 6, 17]. Interestingly, these reported incidence rates of PM-CUP were lower than in the incidence of 17% in the present study. Meanwhile, recent literature showed that the incidence of cancer from an unknown primary in general decreases due to the improvement and increased use of diagnostic tools such as positron emission tomography (PET)–computed tomography (CT) or more extensive morphological examination and therefore more effective detection of the primary tumor [5, 18]. The increasing incidence of PM-CUP in this study could be a relative increase due to an overall decrease of patients with cancer of unknown primary. This could be caused by a lack of further diagnostic testing for a primary tumor due to the dismal prognosis of patients in whom PM-CUP are present, in contrast to patients with metastases where the suspected prognosis warrants further investigation.

Patients with PM-CUP have a dismal prognosis with a median OS of 1.1 months as shown in this study. This is comparable to the median OS of 42 days in PM-CUP patients reported in our previously published cohort [5]. This implies that limited progress, on improving the prognosis of these patients, has been made in the past decade.

A finding with clinical importance is that patients with PM-CUP with a carcinoid histology had a remarkably higher survival than patients with other histological subtypes. Previous studies also reported that neuroendocrine carcinomas (e.g., carcinoid) of unknown primary in general have a more prognostic favorable clinicopathological entity as compared to other metastases of unknown primary [19]. This is partly explained by the inherently less aggressive behavior of neuroendocrine tumors as well as the availability of an effective systemic treatment [20]. Indeed, in the current cohort the proportion of patients receiving systemic treatment is relatively high in PM-CUP patients with a carcinoid as compared to the other histological types. Not surprisingly, the treatment in these patients consisted predominantly of hormone therapy, such as octreotide. One has to realize however that according to a population-based study on neuroendocrine carcinomas, the survival of neuroendocrine carcinomas of unknown primary was worse than those with an identified primary tumor [21]. This is probably because metastases of unknown primary in general are often characterized by a more aggressive tumor behavior [22].

In the present study, almost 80% of the patients with PM-CUP did not receive any treatment. An explanation for this remarkably high number could be that half of the patients already died within the first month after the diagnosis. Consequently, these patients did not have the opportunity to start with any form of treatment. In a previous report, we showed that 87% of the patients did not receive any treatment. In this cohort, upward from 1984, the usage of systemic therapy was increased from 8% in the earliest period to 16% in most recent years (2010) [5]. In our present cohort, 20% of all patients received systemic treatment, which empowers this previous reported increasing trend in systemic treatment application for patients with PM-CUP. Nevertheless, survival did not improve in this period of time despite this increasing trend in systemic treatment application.

Patients who received tumor-directed treatment in the current study had a significantly better OS compared to patients who did not receive any treatment. However, these reported outcomes should be interpreted with care because it is conceivable that treatment selection bias might play an important role, as patients with a good condition are more likely to receive tumor-directed treatment [23]. Furthermore, especially in patients with cancer of unknown primary, performance status appeared to be an important prognostic factor for survival. Therefore, according to the Dutch guidelines, it is recommended to make a distinction between patients with a low performance status and a good performance whether to receive tumor-directed treatment or not. Unfortunately, in the present study, data on performance status was missing in a substantial number of patients and therefore, possible influence on the given treatments could not be investigated.

As previously stated, new multimodal treatment strategies for peritoneal malignancies have changed the prognosis of patients with PM from a variety of origins. In patient with isolated and limited colorectal PM, survival was significantly better in patients undergoing CRS-HIPEC, and therefore this treatment strategy is now recommended by most (inter)national guidelines [10, 24, 25]. Furthermore, promising results have been published in studies on CRS-HIPEC for strictly selected patients with PM from ovarian cancer and currently a randomized controlled trial (PERISCOPE II, NCT03348150) investigates the role of this treatment modality in patients with isolated limited gastric PM [9, 11]. Besides new treatment options with curative intent, different variants of intraperitoneal chemotherapy are currently being explored for patients with more extensive disease [12, 13, 15, 16]. Hence, as effective treatment options are becoming more available for patients with peritoneal malignancies, it is crucial that the primary tumor will be identified. However, despite the recommendation in the Dutch guidelines for a high dose CT or PET/CT scan in patients with an unknown primary tumor, a recent study demonstrated that only 25% of these patients received this extensive diagnostic work-up [23]. This clearly needs more attention in daily clinical practice.

This study has some limitations. First, data on performance status were missing in a substantial amount of patients and therefore possible influence of this factor could not be investigated. Second, there was no data available about the use of diagnostic tools in PM-CUP patients. However, this study used nationwide data from the NCR which provides highly accurate data on tumor and patients characteristics, strengthening the generalizability.

Conclusions

This study provides an up-to-date overview of the incidence of patients with PM-CUP. PM-CUP were diagnosed in 17% of all patients with cancer of unknown primary and the survival of all patients with PM-CUP was extremely poor. Moreover, in comparison with our previous reported cohort, a continuous increasing trend in the application of systemic treatment has been shown. Nevertheless, this increasing trend did not result in better survival outcomes for patients with PM-CUP. Despite this, survival differed among each histological subtype and recently more treatment options became available for a selected group of patients with peritoneal malignancies. Therefore, it is of great importance to identify the histology of the PM and the primary tumor whenever possible.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by A. Rijken, F.N. van Erning and I.H.J.T. de Hingh. The first draft of the manuscript was written by A. Rijken, and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Declarations

Disclosures

De Hingh: An unrestricted research grant for unrelated research from RanD Biotech and ROCHE, paid to the institute. The other authors declare no conflict of interest.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Lemmens VE, Klaver YL, Verwaal VJ, Rutten HJ, Coebergh JWW, de Hingh IH. Predictors and survival of synchronous peritoneal carcinomatosis of colorectal origin: a population-based study. Int J Cancer. 2011;128(11):2717–2725. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hennessy BT, Coleman RL, Markman M. Ovarian cancer. Lancet. 2009;374(9698):1371–1382. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61338-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thomassen I, van Gestel YR, van Ramshorst B, Luyer MD, Bosscha K, Nienhuijs SW, et al. Peritoneal carcinomatosis of gastric origin: a population-based study on incidence, survival and risk factors. Int J Cancer. 2014;134(3):622–628. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rijken A, Bakkers C, van Erning FN, van der Geest LG, de Vos-Geelen J, Besselink MG, et al. Incidence, Treatment, and Survival of Synchronous Peritoneal Metastases in Pancreatic Cancer: Update of a Nationwide Cohort. Pancreas. 2021;50(6):827–833. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0000000000001857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thomassen I, Verhoeven RHA, van Gestel YRBM, van de Wouw AJ, Lemmens VEPP, de Hingh IHJT. Population-based incidence, treatment and survival of patients with peritoneal metastases of unknown origin. Eur J Cancer. 2014;50(1):50–56. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2013.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van de Wouw AJ, Janssen-Heijnen MLG, Coebergh JWW, Hillen HFP. Epidemiology of unknown primary tumors; incidence and population-based survival of 1285 patients in Southeast Netherlands, 1984–1992. Eur J Cancer. 2002;38(3):409–413. doi: 10.1016/S0959-8049(01)00378-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pavlidis N, Pentheroudakis G. Cancer of unknown primary site. Lancet. 2012;379(9824):1428–1435. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61178-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rassy E, Parent P, Lefort F, Boussios S, Baciarello G, Pavlidis N (2020) New rising entities in cancer of unknown primary: Is there a real therapeutic benefit? Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 147:102882 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.van Driel WJ, Koole SN, Sikorska K, Schagen van Leeuwen JH, Schreuder HWR, Hermans RHM, et al. Hyperthermic Intraperitoneal Chemotherapy in Ovarian Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(3):230–240. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1708618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Verwaal VJ, Bruin S, Boot H, van Slooten G, van Tinteren H. 8-year follow-up of randomized trial: cytoreduction and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy versus systemic chemotherapy in patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis of colorectal cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15(9):2426–2432. doi: 10.1245/s10434-008-9966-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang XJ, Huang CQ, Suo T, Mei LJ, Yang GL, Cheng FL, et al. Cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy improves survival of patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis from gastric cancer: final results of a phase III randomized clinical trial. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18(6):1575–1581. doi: 10.1245/s10434-011-1631-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alyami M, Bonnot PE, Mercier F, Laplace N, Villeneuve L, Passot G, et al. Pressurized intraperitoneal aerosol chemotherapy (PIPAC) for unresectable peritoneal metastasis from gastric cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2021;47(1):123–127. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2020.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Boer NL, Brandt-Kerkhof ARM, Madsen EVE, DIepeveen M, van Meerten E, van Eerden RAG et al (2019) Concomitant intraperitoneal and systemic chemotherapy for extensive peritoneal metastases of colorectal origin: protocol of the multicentre, open-label, phase I, dose-escalation INTERACT trial. BMJ Open 9(12):e034508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Rovers KP, Lurvink RJ, Wassenaar ECE, Kootstra TJM, Scholten HJ, Tajzai R et al (2019) Repetitive electrostatic pressurised intraperitoneal aerosol chemotherapy (ePIPAC) with oxaliplatin as a palliative monotherapy for isolated unresectable colorectal peritoneal metastases: protocol of a Dutch, multicentre, open-label, single-arm, phase II study (CRC-PIPAC). BMJ Open 9(7):e030408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Lurvink RJ, Rauwerdink P, Rovers KP, Wassenaar ECE, Deenen MJ, Nederend J et al (2021) First-line palliative systemic therapy alternated with electrostatic pressurised intraperitoneal aerosol chemotherapy (oxaliplatin) for isolated unresectable colorectal peritoneal metastases: protocol of a multicentre, single-arm, phase II study (CRC-PIPAC-II). BMJ Open 11(3):e044811 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Bakrin N, Tempfer C, Scambia G, de Simone M, Gabriel B, Grischke EM et al (2018) PIPAC-OV3: A multicenter, open-label, randomized, two-arm phase III trial of the effect on progression-free survival of cisplatin and doxorubicin as Pressurized Intra-Peritoneal Aerosol Chemotherapy (PIPAC) vs. chemotherapy alone in patients with platinum-resistant recurrent epithelial ovarian, fallopian tube or primary peritoneal cancer. Pleura Peritoneum 3(3):20180114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Schroten-Loef C, Verhoeven RHA, de Hingh IHJT, van de Wouw AJ, van Laarhoven HWM, Lemmens VEPP. Unknown primary carcinoma in the Netherlands: decrease in incidence and survival times remain poor between 2000 and 2012. Eur J Cancer. 2018;101:77–86. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2018.06.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Greco FA, Oien K, Erlander M, Osborne R, Varadhachary G, Bridgewater J, et al. Cancer of unknown primary: progress in the search for improved and rapid diagnosis leading toward superior patient outcomes. Ann Oncol. 2012;23(2):298–304. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdr306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stoyianni A, Pentheroudakis G, Pavlidis N. Neuroendocrine carcinoma of unknown primary: a systematic review of the literature and a comparative study with other neuroendocrine tumors. Cancer Treat Rev. 2011;37(5):358–365. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2011.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pavel M, Öberg K, Falconi M, Krenning EP, Sundin A, Perren A, et al. Gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2020;31(7):844–860. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2020.03.304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Riihimäki M, Hemminki A, Sundquist K, Sundquist J, Hemminki K. The epidemiology of metastases in neuroendocrine tumors. Int J Cancer. 2016;139(12):2679–2686. doi: 10.1002/ijc.30400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Riihimäki M, Thomsen H, Hemminki A, Sundquist K, Hemminki K (2013) Comparison of survival of patients with metastases from known versus unknown primaries: survival in metastatic cancer. BMC Cancer 13:36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Meijer L, Verhoeven RHA, de Hingh IHJT, van de Wouw AJ, van Laarhoven HWM, Lemmens VEPP, et al. Extensive diagnostic work-up for patients with carcinoma of unknown primary. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2021;38(2):231–238. doi: 10.1007/s10585-021-10073-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Klaver CEL, Groenen H, Morton DG, Laurberg S, Bemelman WA, Tanis PJ. Recommendations and consensus on the treatment of peritoneal metastases of colorectal origin: a systematic review of national and international guidelines. Colorectal Dis. 2017;19(3):224–236. doi: 10.1111/codi.13593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bushati M, Rovers KP, Sommariva A, Sugarbaker PH, Morris DL, Yonemura Y, et al. The current practice of cytoreductive surgery and HIPEC for colorectal peritoneal metastases: Results of a worldwide web-based survey of the Peritoneal Surface Oncology Group International (PSOGI) Eur J Surg Oncol. 2018;44(12):1942–1948. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2018.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]