Abstract

Introduction:

Immune checkpoint blockade (ICB) is a rapidly emerging field of oncology that has revolutionized the metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC) treatment. Four recent treatment regimens Nivolumab-Ipilimumab, Pembrolizumab-Axitinib, Nivolumab-Cabozantinib, and Pembrolizumab-Lenvatinib—have demonstrated improved clinical endpoints compared to standard of care and are endorsed by NCCN (2021). However, data on patient-reported outcomes (PROs) for patients receiving these regimens are limited. We conducted a comparative assessment of the quality and standardization of PROs endpoints and data reported for these randomized controlled trials (RCTs).

Patients and Methods:

We systematically identified all RCTs evaluating combination ICB for ccRCC. PROs-specific data were abstracted from the final version of 4 RCT protocols, as well as clinical and PROs specific manuscripts published between April 2018 and April 2021. We used 3 previously published guides standardizing PROs research to objectively score the data: i) 24-point PROEAS; ii) 12-point SPIRIT-PRO; and iii) 14-point CONSORT-PRO.

Results:

The CheckMate 214, KEYNOTE 426, CheckMate 9ER, and CLEAR studies had PROEAS scores of 88% (21/24), 37% (9/24), 83% (20/24), and 16% (4/24), respectively, and SPIRIT-PRO scores of 50% (6/12), 75% (9/12), 66% (8/12), and 41% (5/12) respectively. The CONSORT-PRO scores were 86% (12/14) for CheckMate 214 and 43% (6/14) for CheckMate 9ER, but scores were not available for the CLEAR and KEYNOTE 426 studies because of a lack of sufficient data. The average SPIRIT-PRO score across the 4 RCTs was 58%, indicating a reasonable adoption of PROs research in data management and analysis. The CheckMate 214 trial had the longest follow-up and most comprehensive published PROs data.

Conclusion:

Our analysis identified the limitations of current PROs data in combination ICB approved for mRCC. This analysis will enable clinicians to better interpret the current PROs results and emphasize the importance of better incorporation of PROs endpoints in future mRCC trial design.

Keywords: Patient Reported Outcomes, Health Related Quality of Life, Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma, Clear Cell Carcinoma, Kidney Cancer, Immune Checkpoint Blockade, Clinical Trial Design

Introduction

The therapeutic landscape of metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC) has been transformed by the discovery of immune checkpoint inhibitors.1,2 Between 2018 and 2021, this revolution led to FDA approvals for 4 different immune checkpoint blockade (ICB) combinations to treat patients with treatment-naïve mRCC.3-6 The combinations nivolumab with ipilimumab, pembrolizumab with axitnib, nivolumab with cabozantinib, and pembrolizumab with lenvatinib, are recommended by the NCCN guidelines for the first-line treatment of clear cell RCC, and- all of these combinations have met their predefined primary and secondary clinical activity outcomes, leading to improved overall survival (OS) and progression free survival (PFS) compared to sunitinib.7

In an exciting era of new therapy combinations, it is very important to have well-designed clinical trials to best capture patients’ quality of life. Patient-reported outcomes (PROs) are defined by the FDA as patient-centered self-reported questionnaires completed by patients to measure outcomes and effects of the study intervention on health-related quality of life (HRQoL) using pertinent clinical measures.8,9 These tools aim to involve patients in their treatment process by allowing them to express their perceptions of the value of the treatment regimen and measure the impact of a drug beyond its survival benefit. 8-10 The growing importance of PROs in treatment decisions has brought forth proposed standardization guidelines for PROs analysis and reporting. 11-13

Three commonly used guidelines for studying PROs have predefined criteria as follows: Recommendations for Interventional Trials– (SPIRIT-) PRO provides itemized recommendations to standardize PROs data collection in the protocols of clinical trials in which PROs are primary or key secondary endpoints.14 Similarly, the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials– (CONSORT-) PRO provides recommendations focused on standardizing high-quality reporting of PROs data. The Standards in Analyzing Patient-Reported Outcomes and Quality of Life (SISAQoL) Consortium published recommendations in 2020 that focus on normalizing the methodology used for the design and analysis of PROs endpoints in cancer-related randomized clinical trials (RCTs).15,16 Our group has previously developed and published a study using quantitative scoring scale (PROEAS) to evaluate the quality of the methods used to analyze and report PROs endpoints in RCTs, this scoring scale was based on the 2020 recommendations of the SISAQoL Consortium.17 Furthermore, a focused article on quality initiatives within the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) Quality Care Symposium have further addressed value-based strategies, including PROs.18

The current state of reporting PROs outcomes related to cancer treatments has been met with gaps and deficiencies. Many trials have not reported PROs data; others have inadequate content as well as a lack of standardization, which makes it difficult to draw robust conclusions related to treatment. Many systematic reviews have reviewed the suboptimal quality of PROs reporting in detail.17,19-21

Given this context, we aimed to provide an objective review identifying the strengths and limitations of the current PROs data stemming from these 4 RCTs, enabling decision makers to better interpret the current data and for scientists and policy makers to better-design PROs endpoints and use them in future mRCC randomized clinical trials. We compared PROs endpoints for the 4 RCTs that led to the NCCN endorsement for the ICB combination regimens used to treat patients with mRCC.3-6 This comparative review used the previously published PROs guidelines PROEAS, SPIRIT-PRO, and CONSORT-PRO, as noted above.

Patients and Methods

We conducted a review of the FDA Office of Hematology and Oncology Products archives to identify combination drug approvals issued between April 2018 and June of 2021 for first-line treatment of mRCC. For each approved drug combination, we identified the pivotal clinical trial leading to FDA approval and retrieved the final protocol from PubMed and ClinicalTrials.gov. We attempted to source each trial’s protocol, its primary manuscript reporting the clinical results, a subsequent manuscript reporting updated clinical results, and any secondary manuscript reporting PROs (detailed in Figure 1).

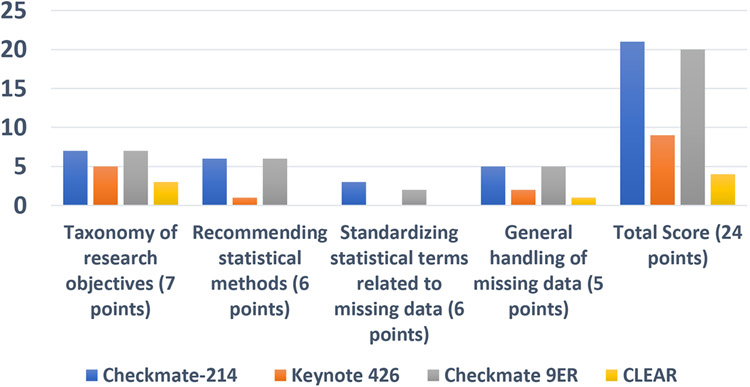

Figure 1a.

Summary of the PROEAS

Our search identified the primary and follow-up clinical and PROs-specific publications reporting on these 4 trials, including 5 papers on CheckMate 214 (4 clinical and 1 PROs-specific),22-26 2 publications on KEYNOTE 426 (both clinical), 27,28 1 publication on CheckMate 9ER (clinical with PROs data included), 29 and 1 publication on CLEAR (clinical).30 Of note, there was a 10-month time interval between the dates of publication of the primary clinical manuscript for CheckMate 214 and the PROs-specific manuscript.

Between January and April 2021, 2 authors (JC, JA) collected data for scoring PROs endpoint content from the final version of the 4 RCTs protocols, and all primary and secondary published manuscripts. The data extraction sheets were derived from our previous publication and used the 24-point PROEAS, which was based on the 2020 recommendations of the SISAQoL Consortium.16,17 These data metrics are related to the 14-point CONSORT-PRO and the 12-point SPIRIT-PRO predefined evaluation criteria. The PROEAS is comprised 4 categories: taxonomy of research objectives, statistical methods, standardizing statistical terms related to missing data, and general handling of missing data. PROEAS score were collected from both published final protocols and all manuscripts.17 The SPIRIT-PRO categories include administrative information; introduction methods for participants, interventions, and outcomes; methods for data collection, management, and analysis; and methods for monitoring. These data were collected from the published protocols only.14 The CONSORT-PRO15 categories were grouped by title and abstract, introduction, methods, randomization, results, and discussion. These data were collected from the published manuscripts only. Each item was scored “1” if it was adequately reported or “0” if it was not clearly reported or not reported at all; all items were weighted equally. The scores were independently collected and reviewed for consensus by 2 authors (JC, AS). The scoring was subject to additional independent (blinded) review by a third researcher (JAC) if no consensus was reached. This study only included publicly available data; therefore, institutional review board approval was not required.

The PROs scores from the 4 RCTs were extracted in detail using the PROEAS, SPIRIT-PRO, and CONSORT-PRO. Scoring for each guideline was collected in detail within excel (Supplemental Table 1a, 1b, and 1c). The guidance for standardization of PROs research was provided by the SISAQOL consortium. Scoring guidelines included PROEAS, which incorporates data from both the protocol and published manuscripts, SPIRIT-PRO, which includes data from protocols only, and CONSORT-PRO, which includes data from manuscripts only.

Statistical Analysis

For each clinical trial study, we aimed to assess the reporting quality of PROs endpoints according to three pre-established PRO guidelines. Assessment results are reported as quantitative scores on different scales depending on the guideline. Scores were compared descriptively between clinical trials. Bar plot and Heat map graph are used to display the scores for PRO subcategories and individual PRO assessment items across the clinical trials, respectively (Supplemental Figures 1a, 1b, 1c). No formal hypothesis test was performed. All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS (Version 25.0, IBM Corp, Armonk, NY) and R version 3.4.1.

Results

The PROs instruments used in the 4 RCTs are as follows: CheckMate 214 used the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–General (FACT-G), European Quality of Life 5-Dimension 3-Level System (EuroQoL EQ-5D-3L), and 19-item Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–Kidney Symptom Index (FKSI-19); KEYNOTE 426 used the EuroQoL EQ-5D-3L, European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire for Patients with Cancer-Core 30 (EORTC QLQ-C30), and Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy -Kidney Symptom Index – Disease-Related Symptoms (FKSI-DRS); CheckMate 9ER used the EuroQoL EQ-D5-3L and FKSI-19; and CLEAR used the EuroQoL EQ-5D-3L, EORTC QLQ-C30, and FKSI-DRS. The above-mentioned PROs instruments are summarized in Table 1 by protocol.

Table 11.

| Protocol | CheckMate 214 | KEYNOTE 426 | CheckMate 9ER | CLEAR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identified PROs instruments in the study design | EuroQol EQ-5D-3L | EuroQol EQ-5D-3L | EuroQOL EQ-5D-3L | EuroQol EQ-5D-3L |

| FKSI 19 | EORTC QLQ-C30 | FKSI 19 | EORTC QLQ-C30 | |

| FACT-G | FKSI-DRS | FKSI-DRS |

EuroQoL EQ-5D-3L (European Quality of Life 5-Dimension 3-Level System), FKSI 19 (19 item Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy -Kidney Symptom Index), EORTC QLQ-C30 (European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire for Patients with Cancer-Core 30), FKSI-DRS (Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy -Kidney Symptom Index – Disease-Related Symptoms)

Figure 1a summarizes the PROEAS scores for each study using the defined categories. The median score was 14.5 (CheckMate 214 received 21 points, KEYNOTE 426 received 9 points, CheckMate 9ER received 20 points, and CLEAR received 4 points). We noted a significant difference in PROEAS in CheckMate 214 (21) and CheckMate 9ER (20) compared to KEYNOTE 426 (9) and CLEAR (4). Both the CheckMate 214 and CheckMate 9ER trials scored full points for taxonomy for research objectives (7/7 points), standardization goals for statistical methods (6/6 points), and statistical assessment plan for handling of missing data (5/5 points); for standardizing statistical terms relating to missing data CheckMate 214 scored 3/6 points and CheckMate 9ER scored 2/6 points. KEYNOTE 426 scored 5/7 points for taxonomy for research objective, 1/6 for standardization goals for statistical methods, 2/5 for statistical assessment plan for handling of missing data, and 1/6 for standardizing statistical terms relating to missing data. Finally, CLEAR scored the lowest, scoring 3/7 points for taxonomy for research objectives, 0/6 for standardization goals for statistical methods, 1/5 for statistical assessment plan for handling of missing data, and 0/6 for standardizing statistical terms relating to missing data.

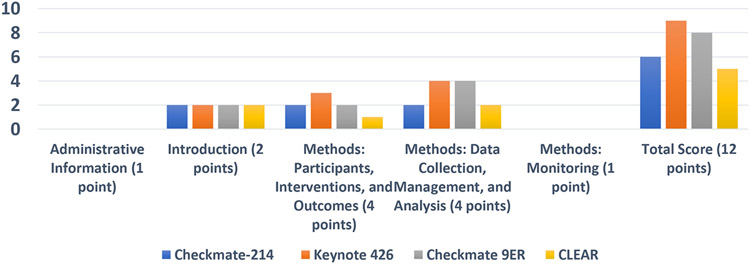

Figure 1b summarizes the SPIRIT-PRO scores across the trials. The total scores using the SPIRIT-PRO–defined categories across the 4 RCTs fell within a comparatively narrow range of 5 to 9, with a median score of 7. Overall, KEYNOTE 426 had the highest SPIRIT-PRO score (9/12 points). KEYNOTE 426 and CheckMate 9ER met all criteria for PROs standardization for data collection, management, and analysis.

Figure Ib.

Summary of SPIRIT-PRO

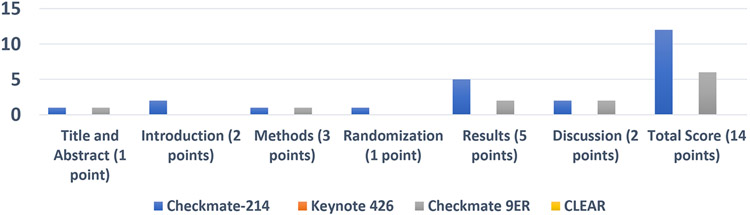

Figure 1c summarizes CONSORT-PRO scores for the trials. Only 2 trials, CheckMate 214 and CheckMate 9ER, had reported data across the categories of this PROs instrument, either in a PROs-specific manuscript or in the primary clinical manuscript. 22-25,29

Figure Ic.

Summary of CONSORT-PRO

Discussion

Among the 3 guidelines, the PROEAS was the most comprehensive guideline because of its robust data collection strategy. There was a significant difference in PROEAS scores between the trials, and this difference was driven by inclusion of PROs-specific standardization of methods for handling statistics and missing data between trials. These observed differences suggest that the CheckMate trials included more PROs-specific standardization and better general handling of PROs data. With the publication lag of PROs results, the CONSORT-PRO instrument was limited in utility. CheckMate 214 had the higher scores in general, which may reflect availability of more complete data with a longer follow-up period. Data from CheckMate 9ER is significant, as it presents reasonable PROs data within the context of a primary clinical manuscript.29 Delayed reporting of PROs results from completed trials is a major limitation in evaluating the incremental benefit of primary clinical endpoints in the context of patients’ important quality of life endpoints.

Scores on SPIRIT-PRO were similar across all 4 RCTs, illustrating progress with goals to include PROs endpoints in clinical trial design. However, there remains an opportunity for advancing high-quality PROs research in future trials. Across the 4 RCTs, the most in-depth PROs results were reported in the PROs dedicated publications.23 Publishing PROs results as part of the primary clinical results can be informative and complementary in interpretation of results (eg the primary clinical manuscript of CheckMate 9ER).29 The study with the longest follow-up, CheckMate 214, also provided the most complete data on PROs. There are no PROs-dedicated publications for CheckMate 9ER or KEYNOTE 426. Though the CLEAR trial’s primary manuscript was published very recently, it included no results on PROs. KEYNOTE 426 has had substantial time from original publication, but there has been no PROs-dedicated publications. The authors have presented data in an abstract form at European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) Virtual Congress 2020, but not in a peer-reviewed manuscript.26 Similarly, authors have presented PROs data in an oral abstract from 2021 American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) Annual Meeting, but it had limited analysis and was not a peer-reviewed manuscript.31 These examples illustrate the lack of robust reporting of PROs data in manuscript format.

The reporting of PROs data often lags behind the fast-paced reporting of clinical outcomes, and for many new treatments, we have limited insight into PROs. For instance, Arcerio et al32 reported a systematic review of PROs for patients receiving approved oncology therapies, noting that only 40% of FDA-approved and 58% of EMA-approved indications had published QoL evidence. Further, only 6% of FDA-approved and 11% of EMA-approved indications included clinically meaningful improvements in patients’ QoL. There has been growing attention for the importance of PROs endpoints; however, this area of research is still evolving, and the current drug development efforts lack standardization of PROs endpoints methodology, analysis, and reporting.32 Specifically, for immune checkpoint blockade, a recent review by our group noted that only 52.3% of RCTs published any PROs data, with limited standardization in PROs analysis, and the majority (85.7%) used descriptive statistics. 17 With increased awareness of the equal importance of both clinical and PROs for advancing the application of novel combinations in clinical practice there would be a great benefit to setting the reporting standards in oncology such that PROs, albeit in limited form be published alongside or be included in the primary clinical manuscript. The more comprehensive PRO-specific manuscripts are valuable and should be promoted for publication in primary oncology journals rather than the secondary journals on quality of life that often may be missed by the clinician readership. The other potential scenario for lack of PROs data is if a study shows no significant difference in PRO scores, although this information would still be helpful to know and published in a formal manuscript setting. The significance for improving research on PROs has also been emphasized by the ASCO Value Framework as well.33

PROs assessments are especially relevant for patients with mRCC, as advancing research and demand for new treatment options rapidly introduces clinically efficacious but potentially toxic new drug regimens into clinical practice.22, 27, 29, 30 This practice is supported by comparable clinical efficacy endpoints despite limited published information on PROs data.

Including PROs data is critical as frontline complex mRCC regimens move toward triplet combinations (eg, NCT04736706).34 Therefore, the results of this study will affect both clinicians and policy makers who are assessing the current state of the standardization of methodology, analysis, and reporting of PROs in RCTs that lead to NCCN support. These results highlight the many limitations of comparing PROs data across trials. Our study aims to improve the design and conduct of future clinical trials for mRCC, incorporating PROs endpoints as an essential patient-centered study outcome.

Advances in health care technology provide new strategies to enhance PROs data collection. Wearable devices that contain sensors, smartphone and computerized applications for symptom monitoring, digital questionnaires, virtual teleconferencing and telemedicine, and AI- and cloud-based platforms are among some of the innovations that may be integrated into clinical trials to improve PROs data collection. Regulatory agencies, such as the FDA, have provided a framework to establish standards for wearable technologies with clinical and research applications. 35

In this study, each of the RCTs’ strengths and limitations regarding PROs were summarized. The results provide clinicians an informed resource on the PROs related to combination ICB regimens while also providing information for patients’ shared decision making. In addition, areas where further focus and improvement may be needed can be identified via further analysis of the subcategories of the PROEAS, SPIRIT-PRO, and CONSORT-PRO (Supplemental Table 1a, 1b, and 1c) with a score of 0 across all trials suggest areas where further focus and improvement may be needed.

A major limitation of this study was that complete PROs data was not available in manuscript form for all 4 RCTs; some were available as only abstracts and oral presentations. This was primarily due to time lapse between reporting primary clinical endpoints compared to PROs results. For instance, CheckMate 214 had the longest follow-up time of the 4 RCTs and is currently the only trial with a PROs-dedicated publication.23 Accordingly, the most reliable PROs outcomes for an ICB combination were from CheckMate 214. Another limitation is that the PROs in the RCTs were not co-primary or secondary endpoints but were largely exploratory endpoints, and therefore cross-trial comparisons in this setting are discouraged. As per the SISAQoL recommendations, comparative conclusions on data are considered appropriate only if PROs is a primary or secondary endpoint. In our review, PROs endpoints were exploratory in all except the CLEAR study, which included PROs as a secondary endpoint. In addition, more rigor with handling missing data, like underreported PROs data or missing follow-up information in longitudinal data collection, is needed. Further limitations include the variability of PROs instruments used in each trial—only the EuroQoL EQ-5D-3L was used in all 4 RCTs. The variability of PROs endpoint design, analysis, and data reporting among the 4 RCTs available at the time of this writing limits an in-depth comparative evaluation of PROs across the studies. Standardization of data extraction is warranted to allow for reliable cross-trial comparisons. Further, it is also noteworthy that the PROs guidelines encompass different predefined evaluation criteria. SPIRIT- PRO provides data only from the published PRO endpoints in the protocols of clinical trials. The CONSORT- PRO provides data from published reports/manuscripts only that include PRO results. Whereas, PROEAS incorporates data on PROs from both the clinical trial design and reported analysis. Based on predefined evaluation criteria of the three guidelines, in the authors’ opinion, PROEAS provides the most comprehensive and robust information on PROs.

This study provides the opportunity to review PRO reporting methodologies in the treatment of mRCC with ICB. Trials with better CONSORT-PRO and PROEAS scores, in particular Checkmate 214 and Checkmate 9ER, provide published information in manuscript form to guide treatment discussions between patients and providers. Longer follow up, including additional PRO-specific publications across these 4 trials may provide additional PRO data to help with clinical decision making.

In summary, PROs measurement in clinical trials is an evolving area with significance in drug development as it brings the patients’ voices into the policy and clinical decisions for adopting drug regimens in clinical practice. Policy makers and clinicians alike should have timely, standardized PROs endpoints, and take into consideration the global benefit of drug regimens on both clinical efficacy and PROs.36 To the authors’ knowledge, this study is the first to comparatively evaluate PROs results from the 4 RCTs on combination ICB for mRCC. However, there remain unanswered questions regarding the choice of the most specific survey tools and accurate statistical endpoints to best reflect clinically valuable benefits for patients receiving novel ICB combination therapies. 22,27,29,30

Supplementary Material

Highlights:

Standardization and reporting of PROs endpoints must be improved.

The time delay between publication of the clinical results and PROs results creates a gap in the knowledge.

Our publication provides clinicians a comparative resource for combination ICB PROs endpoints in mRCC trials.

Acknowledgements:

We would like to acknowledge the editorial office: Editorial assistance was provided by the Moffitt Cancer Center’s Office of Scientific Publishing by Daley Drucker. No compensation was given beyond her regular salary.

This work has been supported in part by the Participant Research, Interventions, and Measurement Core at the H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center & Research Institute, a comprehensive cancer center designated by the National Cancer Institute and funded in part by Moffitt’s Cancer Center Support Grant (P30-CA076292)

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosure:

HJ has been a consultant for RedHill Biopharma, Janssen Scientific Affairs, Merck and has received funding from Kite Pharma. BM is a NCCN committee member. PS is a NCCN Vice Chair committee member. JAC has been a consultant for Exelixis and Pfizer.

References

- 1.Hargadon KM, Johnson CE, Williams CJ. Immune checkpoint blockade therapy for cancer: An overview of FDA-approved immune checkpoint inhibitors. International Immunopharmacology. 2018;62:29–39. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2018.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Riley RS, June CH, Langer R, Mitchell MJ. Delivery technologies for cancer immunotherapy. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery. 2019;18(3):175–196. doi: 10.1038/s41573-018-0006-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nivolumab Combined With Ipilimumab Versus Sunitinib in Previously Untreated Advanced or Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma (CheckMate 214) - Full Text View - ClinicalTrials.gov. Accessed May 6, 2021. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02231749 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Study to Evaluate the Efficacy and Safety of Pembrolizumab (MK-3475) in Combination With Axitinib Versus Sunitinib Monotherapy in Participants With Renal Cell Carcinoma (MK-3475-426/KEYNOTE-426) - Study Results - ClinicalTrials.gov. Accessed May 6, 2021. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/results/NCT02853331 [Google Scholar]

- 5.A Study of Nivolumab Combined With Cabozantinib Compared to Sunitinib in Previously Untreated Advanced or Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma - Full Text View - ClinicalTrials.gov. Accessed May 6, 2021. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03141177 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lenvatinib/Everolimus or Lenvatinib/Pembrolizumab Versus Sunitinib Alone as Treatment of Advanced Renal Cell Carcinoma - Full Text View - ClinicalTrials.gov. Accessed May 6, 2021. https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02811861 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Motzer RJ, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center Þ, Jonasch E, et al. Continue NCCN Guidelines Panel Disclosures NCCN Guidelines Version 4.2021 Kidney Cancer.; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Patient-Reported Outcome Measures: Use in Medical Product Development to Support Labeling Claims ∣ FDA. Accessed May 6, 2021. https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/patient-reported-outcome-measures-use-medical-product-development-support-labeling-claims [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.LeBlanc TW, Abernethy AP. Patient-reported outcomes in cancer care-hearing the patient voice at greater volume. Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology. 2017;14(12):763–772. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2017.153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bottomley A. The Cancer Patient and Quality of Life. The Oncologist. 2002;7(2):120–125. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.7-2-120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.The Lancet Oncology. Immunotherapy: hype and hope. The Lancet Oncology. 2018;19(7):845. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30317-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.The Lancet Oncology. Calling time on the immunotherapy gold rush. The Lancet Oncology. 2017;18(8):981. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30521-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Calvert MJ, O’Connor DJ, Basch EM. Harnessing the patient voice in real-world evidence: the essential role of patient-reported outcomes. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery. 2019;18(10):731–732. doi: 10.1038/d41573-019-00088-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Calvert M, Kyte D, Mercieca-Bebber R, Slade A, Chan AW, King MT. Guidelines for inclusion of patient-reported outcomes in clinical trial protocols the spirit-pro extension. JAMA - Journal of the American Medical Association. 2018;319(5):483–494. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.21903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Calvert M, Blazeby J, Altman DG, Revicki DA, Moher D, Brundage MD. Reporting of patient-reported outcomes in randomized trials: The CONSORT PRO extension. JAMA - Journal of the American Medical Association. 2013;309(8):814–822. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Coens C, Pe M, Dueck AC, et al. International standards for the analysis of quality-of-life and patient-reported outcome endpoints in cancer randomised controlled trials: recommendations of the SISAQOL Consortium. The Lancet Oncology. 2020;21(2):e83–e96. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30790-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Safa H, Tamil M, Spiess PE, et al. Patient-Reported Outcomes in Clinical Trials Leading to Cancer Immunotherapy Drug Approvals From 2011 to 2018: A Systematic Review. JNCI: Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2020;113(5):532–542. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djaa174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Basch E, Hershman D, Gurtshaw C, Schweizer AP, Krzyzanowska M. ASCO’s quality care symposium and the evolving science of value-based care. Journal of Oncology Practice. 2020;16(3):113–114. doi: 10.1200/OP.20.00034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bylicki O, Gan HK, Joly F, Maillet D, You B, Péron J. Poor patient-reported outcomes reporting according to CONSORT guidelines in randomized clinical trials evaluating systemic cancer therapy. Annals of Oncology. 2015;26(1):231–237. doi: 10.1093/ANNONC/MDU489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kyte D, Retzer A, Ahmed K, et al. Systematic Evaluation of Patient-Reported Outcome Protocol Content and Reporting in Cancer Trials. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2019;111(11):1170–1178. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djz038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pe M, Dorme L, Coens C, et al. Statistical analysis of patient-reported outcome data in randomised controlled trials of locally advanced and metastatic breast cancer: a systematic review. The Lancet Oncology. 2018;19(9):e459–e469. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30418-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Motzer RJ, Tannir NM, McDermott DF, et al. Nivolumab plus Ipilimumab versus Sunitinib in Advanced Renal-Cell Carcinoma. New England Journal of Medicine. 2018;378(14):1277–1290. doi: 10.1056/nejmoa1712126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cella D, Grünwald V, Escudier B, et al. Patient-reported outcomes of patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma treated with nivolumab plus ipilimumab versus sunitinib (CheckMate 214): a randomised, phase 3 trial. The Lancet Oncology. 2019;20(2):297–310. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30778-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Motzer RJ, Rini BI, McDermott DF, et al. Nivolumab plus ipilimumab versus sunitinib in first-line treatment for advanced renal cell carcinoma: extended follow-up of efficacy and safety results from a randomised, controlled, phase 3 trial. The Lancet Oncology. 2019;20(10):1370–1385. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30413-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Motzer RJ, Escudier B, McDermott DF, et al. Survival outcomes and independent response assessment with nivolumab plus ipilimumab versus sunitinib in patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma: 42-month follow-up of a randomized phase 3 clinical trial. Journal for ImmunoTherapy of Cancer. 2020;8(2):891. doi: 10.1136/jitc-2020-000891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Albiges L, Tannir NM, Burotto M, et al. Nivolumab plus ipilimumab versus sunitinib for first-line treatment of advanced renal cell carcinoma: Extended 4-year follow-up of the phase III CheckMate 214 trial. ESMO Open. 2020;5(6). doi: 10.1136/esmoopen-2020-001079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rini BI, Plimack ER, Stus V, et al. Pembrolizumab plus Axitinib versus Sunitinib for Advanced Renal-Cell Carcinoma. New England Journal of Medicine. 2019;380(12):1116–1127. doi: 10.1056/nejmoa1816714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Powles T, Plimack ER, Soulières D, et al. Pembrolizumab plus axitinib versus sunitinib monotherapy as first-line treatment of advanced renal cell carcinoma (KEYNOTE-426): extended follow-up from a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. The Lancet Oncology. 2020;21(12):1563–1573. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30436-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Choueiri TK, Powles T, Burotto M, et al. Nivolumab plus Cabozantinib versus Sunitinib for Advanced Renal-Cell Carcinoma. New England Journal of Medicine. 2021;384(9):829–841. doi: 10.1056/nejmoa2026982 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Motzer R, Alekseev B, Rha S-Y, et al. Lenvatinib plus Pembrolizumab or Everolimus for Advanced Renal Cell Carcinoma. New England Journal of Medicine. 2021;384(14):1289–1300. doi: 10.1056/nejmoa2035716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Motzer RJ, Porta C, Alekseev B, et al. Health-related quality-of-life (HRQoL) analysis from the phase 3 CLEAR trial of lenvatinib (LEN) plus pembrolizumab (PEMBRO) or everolimus (EVE) versus sunitinib (SUN) for patients (pts) with advanced renal cell carcinoma (aRCC). Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2021;39(15_suppl):4502–4502. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2021.39.15_suppl.4502 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Arciero V, Delos Santos S, Koshy L, et al. Assessment of Food and Drug Administration- And European Medicines Agency-Approved Systemic Oncology Therapies and Clinically Meaningful Improvements in Quality of Life: A Systematic Review. JAMA Network Open. 2021;4(2):2033004. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.33004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schnipper LE, Davidson NE, Wollins DS, et al. Updating the American society of clinical oncology value framework: Revisions and reflections in response to comments received. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2016;34(24):2925–2933. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.68.2518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.A Study of Pembrolizumab (MK-3475) in Combination With Belzutifan (MK-6482) and Lenvatinib (MK-7902), or Pembrolizumab/Quavonlimab (MK-1308A) in Combination With Lenvatinib, Versus Pembrolizumab and Lenvatinib, for Treatment of Advanced Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma (MK-6482-012) - Full Text View - ClinicalTrials.gov. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04736706 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Spreafico A, Hansen A, Abdul Razak A. The Future of Clinical Trial Design in Oncology. Cancer discovery, (2021), 822–837, 11(4). https://www.fda.gov/downloads/MedicalDevices/DigitalHealth/UCM568735.pdf [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Calvert MJ, O’Connor DJ, Basch EM. Harnessing the patient voice in real-world evidence: the essential role of patient-reported outcomes. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery. 2019;18(10):731–732. doi: 10.1038/d41573-019-00088-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.