Abstract

During a parasitological survey carried out between May and August 2022 in the River Nyando, Lake Victoria Basin, a single species of Rhabdochona Railliet, 1916 (Nematoda: Rhabdochonidae) was recorded from the intestine of the Rippon barbel, Labeobarbus altianalis (Boulenger, 1900) (Cyprinidae). Based on light microscopy (LM), scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and DNA analyses the parasite was identified as Rhabdochona (Rhabdochona) gendrei Campana-Rouget, 1961. Light microscopy, SEM and DNA studies on this rhabdochonid resulted in a detailed redescription of the adult male and female. The following additional taxonomic features are described in the male: 14 anterior prostomal teeth; 12 pairs of preanal papillae: 11 subventral and one lateral; six pairs of postanal papillae: five subventral and one lateral, with the latter pair at the level of first subventral pairs when counted from the cloacal aperture. For the female: 14 anterior prostomal teeth and the size and absence of superficial structures on fully mature (larvated) eggs dissected out of the nematode body. Specimens of R. gendrei were genetically distinct in the 28S rRNA and cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1 (cox1) mitochondrial gene regions from known species of Rhabdochona. This is the first study that provides genetic data for a species of Rhabdochona from Africa, the first SEM of R. gendrei, and the first report of this parasite from Kenya. The molecular and SEM data reported herein provide a useful point of reference for future studies on Rhadochona in Africa.

Keywords: Cyprinidae, Freshwater fish parasite, Helminths, Lake Victoria Basin, Rippon barbel, River Nyando

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Redescription of Rhabdochona gendrei from Labeobarbus altianalis.

-

•

The first study providing genetic data for a species of Rhabdochona from Africa.

-

•

This is the first scanning electron microscopy study of R. gendrei.

-

•

First report of R. gendrei from Kenya.

-

•

Findings herein provide useful point of reference for future studies on Rhadochona.

1. Introduction

Rhabdochona (Rhabdochona) gendrei Campana-Rouget (1961) is a parasitic intestinal nematode belonging to the Rhabdochonidae Travassos, Artigas et Pereira, 1928, the only superfamily of the Thelazioidea Skryabin, 1915 that includes representatives from fishes (Moravec, 2019). Members of this family are characterized by a funnel or barrel-shaped prostom which is an extension of the anterior end of the vestibule/stoma, the presence of teeth (a result of longitudinal thickenings of the internally lined prostom), a muscular oesophagus encircled by a nerve ring, absence of a gubernaculum, and presence of at least 5 pairs of preanal and 5 pairs postanal papillae in males (Moravec, 2010, 2019). Species of Rhabdochona Railliet (1916) infect the digestive tract of freshwater fishes, while others accidentally infect other vertebrates (Moravec, 2007, 2010, 2019). It is worth noting that species of Rhabdochona occur in all zoogeographical regions (Moravec et al., 2008; Moravec, 2019). To date, only 10 valid species of Rhabdochona (two subgenera Rhabdochona and Globochona) have been recorded in freshwater fishes in Africa (Moravec, 2019). These valid species include: Rhabdochona (Rhabdochona) centroafricana Moravec et Jirků, 2014; Rhabdochona (Rhabdochona) esseniae Mashego (1990); Rhabdochona (Rhabdochona) gendrei Campana-Rouget (1961); Rhabdochona (Rhabdochona) marcusenii Moravec et Jirků, 2014; Rhabdochona (Rhabdochona) moraveci Puylaert (1973); Rhabdochona (Rhabdochona) puylaerti Moravec (1983); Rhabdochona (Rhabdochona) srivastavai Chabaud (1970); Rhabdochona (Globochona) gambiana Gendre (1922); Rhabdochona (Globochona) paski Baylis (1928) and Rhabdochona (Globochona) tricuspidata Moravec et Jirků, 2014. These rhabdochonids have been reported from eight fish families, the Cyprinidae, Cichlidae, Alestidae, Schilbeidae, Gobiidae, Cyprinodontidae, Mormyridae, and Mochokidae (Gendre, 1922; Baylis, 1928; Campana-Rouget, 1961; Chabaud, 1970; Puylaert, 1973; Moravec, 1983; Mashego, 1990; Moravec and Jirků, 2014).

Rhabdochona (Rhabdochona) gendrei was first reported by Gendre (1922) infecting Barbus sp. in Gambia (Oundou – Gambia River Basin). The author gave a description and drawings but assigned the parasite erroneously to the Neotropical species Rhabdochona acuminata (Molin, 1860). Later, Campana-Rouget (1961) described the same species from three cyprinids, Barbus altianalis, Barbus duchesnii and Barbus bynni [presently known as Labeobarbus altianalis (Boulenger, 1900), Labeobarbus intermedius (Rüppell, 1835) and Labeobarbus bynni (Forsskål, 1775), respectively], from Zaïre (now Democratic Republic of Congo - DRC) in Lakes Albert, Edward and Kivu. Moravec (1972) also provided more morphological details of this rhabdochonid from B. duchesnii (now L. intermedius) in Lake Kivu in DRC (Gendre, 1922; Campana-Rouget, 1961; Moravec, 1972). Puylaert (1973) reported this nematode from Barbus camptacanthus [presently known as Enteromius camptacanthus (Bleeker, 1863) in Cameroon (Olounou)]. It was also documented from a mochokid fish, Synodontis sorex Günther, 1864, by Vassiliadès and Troncy (1974) from Chad (Chari River).

The present study provides results on Rhabdochona nematodes collected from Rippon barbel Labeobarbus altianalis (Boulenger, 1900) within the basin of Lake Victoria in Kenya. The nematodes morphologically resemble R. gendrei, hence some clarifications of the species' identity. An integrated approach using a combination of analytical methods [light microscopy (LM), scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and molecular characterization using the partial 28S rRNA and COI genes] was implemented to supplement existing data of taxonomic importance in species identification. So far, SEM and genetic data for species of Rhabdochona from Africa are lacking. Consequently, the present study report on additional taxonomically relevant characters using SEM, provides the first molecular data of R. gendrei in the native L. altianalis from Kenya and extends the geographical records of this parasite to East Africa, Kenya.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Ethical approval for the study

Collection and laboratory handling of all fish samples followed the Kenya Marine and Fisheries Research Institute (KMFRI) and Kisii University's institutional ethical policies and guidelines. No permits were required for this study because it was carried out under the routine surveys of KMFRI a body mandated to conduct research in fisheries, marine and freshwater ecosystems in Kenya.

2.2. Sample collection and examination

A total of 32 L. altianalis individuals were collected from the River Nyando system between May and August 2022 at Koru and Ahero (Fig. 1). Fish were collected with the use of an Electrofisher (SAMUS 1000, Samus Special Electronics, RX 28371, China), and identified following the photographic guide of Okeyo and Ojwang (2015). The names and nomenclature of fish follow FishBase (Froese and Pauly, 2022).

Fig. 1.

A map of River Nyando, in Lake Victoria Basin, showing the study locations at Koru and Ahero.

Identified live fish were packaged in oxygenated plastic bags with the same river water from where they were collected and transported to Kisii University, Department of Biological Sciences laboratory for preliminary parasitological examination. In the laboratory, all fish were euthanised by severing the spinal cord posterior to the skull (Schäperclaus, 1990). Using a Leica Zoom 2000 stereo microscope (model no. Z30V) dissections were done, the intestines were opened carefully with fine forceps, and nematodes were removed using a 000 Camel's hair paintbrush. The recovered rhabdochonids were transferred and washed in 1% physiological saline and then fixed in hot 10% formalin, 70% ethanol for morphological and 96% ethanol for molecular studies. The samples were transported to the parasitology laboratory in the Department of Biodiversity, University of Limpopo, South Africa for further examination and analysis.

2.3. Morphological analyses, microdissection of fully mature eggs and excision of spicules

For LM, 4% formalin and 70% ethanol fixed rhabdochonids were cleared in glycerine (Rindoria et al., 2020), photographed and measured using an Olympus U-DA 0C13617 compound microscope with a digital measuring software (model BX50F no. 4C05604 Olympus Optical Co. Ltd, Japan). Measurements were taken and are given in micrometres (μm), unless otherwise stated, and reported as a range followed, in parentheses, by the mean values. Soft tissues of the posterior end of the male specimens fixed in 70% ethanol were enzymatically digested as per the guide of Rindoria et al. (2020).

For microdissection of the fully mature (larvated) eggs on the female, the female specimens were observed under a dissecting microscope. The mature females with eggs were microdissected using 2 sharped dissecting needles, holding the nematode with one needle and cutting with the other. For SEM, the revealed spicule (after digestion), eggs (after microdissection), and whole specimens fixed in 70% ethanol were prepared by dehydrating through a graded ethanol series, followed by a graded series of hexamethyldisilazane (HMDS) (Nation, 1983; Dos Santos and Avenant- Oldewage, 2015). Specimens were dried in a portable glass desiccator, gold coated using an Emscope SC500 sputter coater (Quorum Technologies, Newhaven, U.K.). Specimens were then studied using a Vega 3 LMH scanning electron microscope (Tescan, Brno, Czech Republic) at 6 kV acceleration voltages.

2.4. Molecular analyses

Genomic DNA was extracted using a Zymo Research Quick-DNA™ Microprep Plus Kit following the manufacturer's instructions. The 28S rRNA and cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1 (cox1) mitochondrial gene regions were amplified using primer sets 502-F (5′-CAA GTA CCG TGA GGG AAA GTT GC-3′) and 536-F (5′-CAG CTA TCC TGA GGG AAA C-3′) (Lagunas-Calvo et al., 2019), and COIint-F (5′-TGA TTG GTG GTT TTG GTA A-3′) and COIint-R (5′-ATA AGT ACG AGT ATC AAT ATC-3′) (Casiraghi et al., 2001), respectively. PCR reactions were performed with a total volume of 25 μl containing: 1 μl of each primer, 12 μl of double distilled water, 7 μl of DreamTaq™ Hot Start Green PCR Master Mix (2X) (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA) and 4 μl of template DNA. The thermal cycling profile had an initial denaturation of 94 °C for 3 min; initial annealing at 94 °C for 30 s and 35 cycles at 54 °C for 30 s, 72 °C for 2 min and final extension at 72 °C for 7 min for the 28S rRNA amplification reaction. The same thermal profile was used for the amplification of the cox1, with an adjustment in the annealing temperature to 45 °C for 1 min.

2.5. Sequence alignment and molecular analyses

Successful amplification reactions were verified using a 1% agarose gel and sent for cleaning, purification and sequencing to Inqaba Biotechnical Industries (Pty) Ltd. (Pretoria, South Africa). Sequence data obtained were inspected, aligned and assembled under default parameters of MUSCLE using Geneious Prime v2022.2. (https://www.geneious.com). The resulting consensus sequences, 28S rRNA (789bp and 790bp) and cox1 (484bp and 523bp) were subjected to a Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST, https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi) (Altschul et al., 1990) to identify the closest congeners. Alignments for each gene region were constructed in Geneious and trimming of the resulting alignment was performed in trimAL v.1.2. using the “gappyout” parameter selection under default settings (Capella-Gutiérrez et al., 2009). The alignments for both gene regions included all available published sequences of Rhabdochona since no comparative sequence data is available for African representatives. The final length of the 28S rRNA alignment was 1083bp and that of the cox1 was 599bp. Details of species included in the phylogenetic inference are presented in Table 1. Spinitectus mexicanus Caspeta-Mandujano, Moravec et Salgado Maldonado, 2000 was used as the outgroup for all alignments (Caspeta-Mandujano et al., 2000; Černotíková et al., 2011; Choudhury and Nadler, 2018). Uncorrected pairwise distances (p-distances) were estimated in MEGA7 (Kumar et al., 2016) and optimal substitution model selection was done using jModelTest v2.1.3. (Darriba et al., 2012). The HKY + G model was implemented for the 28S rRNA alignment, whereas the HKY + I + G was implemented for the cox1 alignment. Maximum likelihood (ML) analyses were computed in phyML using the ATGC Montpellier Bioinformatics Platform (http://www.atgc-montpellier.fr/) (Guindon and Gascuel, 2003) and Bayesian Inference (BI) analyses were performed in MrBayes using the CIPRES (Miller et al., 2010) computational resource. The BI analyses were generated by implementing a data block criterion running two independent Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) chains of four chains for 1 million generations. A sampling of the MCMC chain was set at every 1000th generation and a burn-in was set to the first 25% of the sample generations. Phylogenetic trees generated were visualised in FigTree v1.4.4. (Rambaut, 2018).

Table 1.

Details on the species of Rhabdochona Railliet, 1916 and accession numbers of the 28S rRNA and cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1 (cox1) mitochondrial gene regions used in the phylogenetic analyses. Species sequenced in the present study are in bold. * ‒ Indicate species used as outgroup.

| Species | Host | Locality | 28S | cox | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rhabdochona acuminata | Brycon guatemalensis | (Characiformes: Bryconidae) | Mexico | MK341679 | MK341634 | Santacruz et al. (2020) |

| Mexico | MK341680 | MK341635 | ||||

| Mexico |

MK341681 |

MK341636 |

||||

| Rhabdochona adentata | Profundulus oaxacae | (Cyprinodontiformes: Profundulidae) | Mexico | – | MN927201 | Caspeta-Mandujano et al. (2021) |

| Mexico |

– |

MN927199 |

||||

| Rhabdochona ahuelhuellensis | Ilyodon whitei | (Cyprinodontiformes: Goodeidae) | Mexico | – | MK353475 | Lagunas-Calvo et al. (2019) |

| Mexico | – | MK353476 | ||||

| Mexico |

– |

MK353477 |

||||

| Rhabdochona canadensis | Gila conspersa | (Cypriniformes: Leuciscidae) | Mexico | MK341685 | MK353485 | Santacruz et al. (2020) |

| Mexico | MK341686 | MK353486 | ||||

| Mexico |

– |

MK341637 |

||||

| Rhabdochona gendrei | Labeobarbus altianalis | (Cypriniformes: Cyprinidae) | Kenya | OR096360 | OR088887 | Present study |

|

Kenya |

OR096361 |

OR088888 |

Present study |

|||

|

Rhabdochona guerreroensis |

Sicydium multipunctatum |

(Gobiiformes: Goobiidae) |

Mexico |

– |

MN592669 |

Caspeta-Mandujano et al. (2021) |

| Rhabdochona ictaluri | Ictalurus pricei | (Siluriformes: Ictaluridae) | Mexico | MK353492 | MK353478 | Lagunas-Calvo et al. (2019) |

| Mexico | – | MK353479 | ||||

| Mexico |

– |

MK353480 |

||||

|

Rhabdochona juliacarabiasae |

Eugerres mexicanus |

(Eupercaria: Gerreidae) |

Mexico |

– |

MF405199 |

Caspeta-Mandujano et al. (2021) |

| Rhabdochona kidderi | Rhamdia gautemalensis | (Siluriformes: Heptapteridae) | Mexico | MK353490 | MK353472 | Lagunas-Calvo et al. (2019) |

| Mexico | MK353491 | MK353473 | ||||

| Mexico |

– |

MK353474 |

||||

| Rhabdochona lichthenfelsi | Allotoca regalis, Goodea atripinis | (Cyprinodontiformes: Goodeidae) | Mexico | MK341682 | DQ991009 | Santacruz et al. (2020); Mejía-Madrid et al. (2007) |

| Goodea atripinis | Mexico | – | DQ990982 | Mejía-Madrid et al. (2007) | ||

| Mexico |

– |

DQ990984 |

Mejía-Madrid et al. (2007) |

|||

| Rhabdochona mexicana | Astyanax mexicanus | (Characiformes: Characidae) | Mexico | MK341653 | MK341601 | Santacruz et al. (2020) |

| Mexico | MK341654 | MK341603 | ||||

| Mexico | MK341660 | MK341606 | ||||

| Mexico | MK341661 | MK341607 | ||||

| Mexico | MK341663 | MK341612 | ||||

| Mexico | MK341664 | MK341613 | ||||

| Mexico | MK341665 | MK341614 | ||||

| Mexico | MK341666 | MK341615 | ||||

| Mexico | MK341655 | MK341602 | ||||

| Astyanax aeneus | (Characiformes: Characidae) | Mexico | MK341656 | MK341598 | ||

| Mexico | MK341657 | MK341600 | ||||

| Mexico | MK341658 | MK341596 | ||||

| Mexico | MK341659 | MK341611 | ||||

| Astyanax aeneus | (Characiformes: Characidae) | Guatemala | MK341667 | MK341617 | ||

| Guatemala | MK341668 | MK341619 | ||||

| Guatemala | MK341669 | MK341616 | ||||

| Mexico | MK341670 | MK341620 | ||||

| Mexico |

MK341671 |

MK341621 |

||||

| Rhabdochona salgadoi | Profundulus sp. | (Cyprinodontiformes: Profundulidae) | Mexico | MK341683 | MK341632 | Santacruz et al. (2020) |

| Mexico | MK341684 | MK341633 | ||||

|

Profundulus labialis |

(Cyprinodontiformes: Profundulidae) |

Mexico |

MH778492 |

Caspeta-Mandujano et al. (2021) |

||

| Rhabdochona osoroi | Astyanax aeneus | (Characiformes: Characidae) | Mexico | MK341672 | MK341622 | Santacruz et al. (2020) |

| Mexico | MK341677 | MK341624 | ||||

| Mexico |

MK341678 |

MK341629 |

||||

| Rhabdochona xiphophori | Poecilia mexicana | (Cyprinodontiformes: Poeciliidae) | Mexico | MK353496 | MH778493 | Caspeta-Mandujano et al. (2021) |

| Poeciliopsis gracilis | (Cyprinodontiformes: Poeciliidae) | Mexico | – | MK353483 | Lagunas-Calvo et al. (2019) | |

| – |

– |

Mexico |

– |

MN592670 |

||

| Spinitectus mexicanus* | Pseudoxiphophorus bimaculatus | (Cyprinodontiformes: Poeciliidae) | Mexico | MK341687 | MK341638 | Santacruz et al. (2020) |

3. Results

3.1. Morphometric and morphological analyses

Family Rhabdochonidae Travassos, Artigas et Pereira, 1928.

Rhabdochona (Rhabdochona) gendrei Campana-Rouget (1961) (Fig. 2A–F, 4A-H)

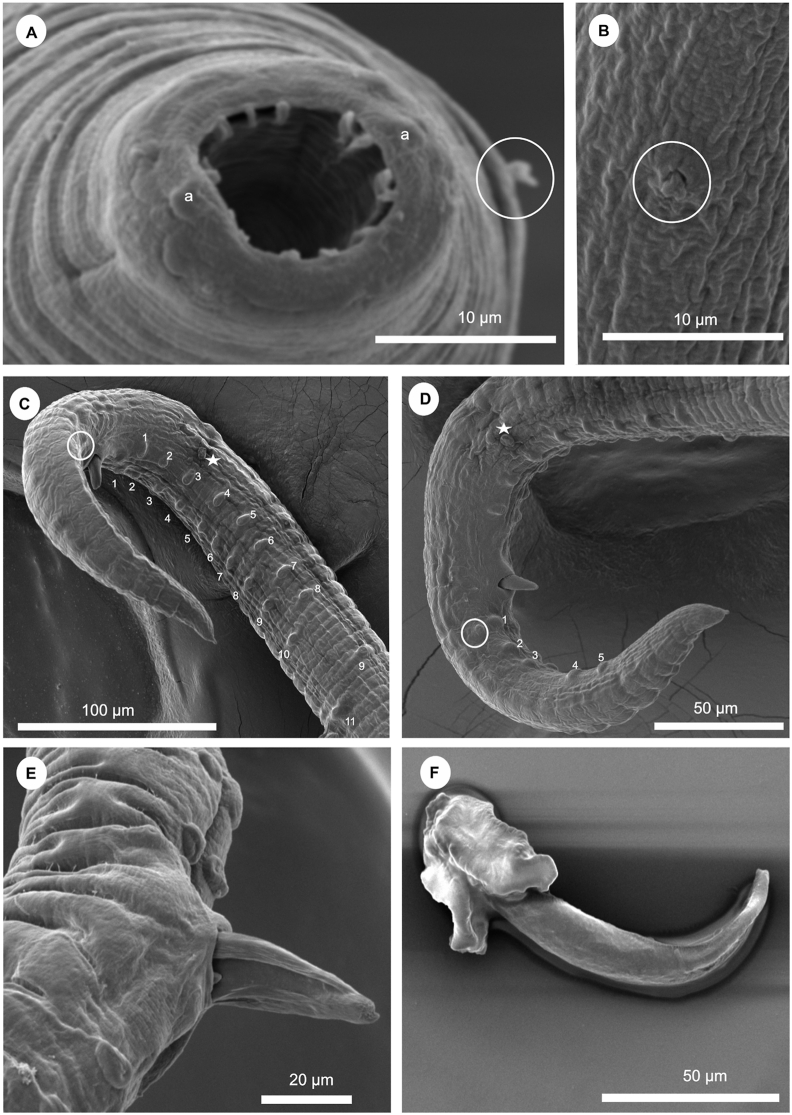

Fig. 2.

Rhabdochona (Rhabdochona) gendreiCampana-Rouget (1961) from Labeobarbus altianalis (Boulenger, 1900), scanning electron micrographs of the male. A – cephalic end, subapical view; B – deirid; (circled); C, D – posterior end of male, ventrolateral view (white stars and white circles indicate a pair of lateral pre- and postanal papillae, respectively); E − right spicule; F – excised right spicule, following enzymatic digestion. Abbreviations: a – amphid; 1–11, and 1–9 – pairs of sub-ventral preanal papillae (in C); 1–5 – pairs of postanal papillae (in D).

Syns:Nec Spiroptera acuminata Molin, 1859; Nec Spiroptera acuminata Von drasche, 1883; Nec Oxyspirura acuminata Stossich, 1897; Nec Rhabdochona acuminata Travassos, Artigas et Pereira,1928; Rhabdochona acuminata sensu Gendre (1922) and Nec Rhabdochona acuminata Vaz et Pereira, 1934.

General description: Medium-sized nematodes. Tetragonal oral opening with a pair of adjacent amphids and four submedian cephalic papillae surrounding the opening. Prostom funnel-shaped, armed with 14 anterior teeth. Vestibule straight, relatively long. Deirids average-sized, biforked/bifurcate, situated approximately mid-length of vestibule. Tail of both sexes conical, with sharply pointed tip.

Male (9 specimens): Length of body 6.02–9.36 (7.36) mm, maximum width 110.40–169.90 (140.06). Vestibule including prostom 131.04–171.20 (153.50) long; length of prostom 21.36–24.80 (23.11), width 17.22–20.74 (18.86). Length of muscular oesophagus 272.45–430.14 (342.76), of glandular oesophagus 2.65–3.92 (3.16) mm. Deirids, nerve ring, and excretory pore 78.23–85.45 (81.53), 205.56–231.84 (216.28), 278.14–311.21 (298.29) from anterior extremity, respectively. Preanal papillae 10–12 pairs: 9–11 sub-ventral and 1 lateral pairs; latter pair approximately at level of third sub-ventral pair (counted from cloacal aperture). Postanal papillae 6 pairs: 5 subventral and 1 lateral pairs; latter pair approximately at level of first subventral pairs (counted from cloaca aperture). Left spicule 426.79–576.30 (519.01) long. Right spicule 150.26–177.94 (161.29) long, tapering at its distal end, without usual dorsal barb. Length ratio of spicules 1:2.57–3.76 (3.23). Tail 263.71–577.69 (348.26) long, with cuticular spike at tip.

Female (5 specimens): Length of body 9.88–20.55 (14.18) mm, maximum width 138.37–348.50 (268.26). Length of vestibule including prostom 148.34–200.35 (163.77); prostom 22.92–24.32 (23.63) long, 15.94–19.11 (17.95) wide, with distinct basal teeth. Deirids, nerve ring and excretory pore 91.56–120.12 (104.20), 221.34–254.63 (236.34), and 311.56–351.02 (328.45), respectively, from anterior extremity. Vulva postequatorial, 4.32–11.36 (8.00) mm from posterior end of body. Size of mature (larvated) eggs 458.75–474.04 (476.66) length, 302.74–353.63 (324.80) width. Tail conical, 274.54–428.43 (348.64) long, with distinct cuticular spike at end.

Host: Labeobarbus altianalis (Boulenger, 1900) (Cyprinidae, Cypriniformes).

Site of infection: Intestine.

Locality/collection date: River Nyando (Lake Victoria Basin) Kisumu County, Kenya (000′ 0°22′S, 34°51′E 35011′E) (see Fig. 1) (collected May 3 and August 3, 2022, by Drs. Nehemiah M. Rindoria and George N. Morara).

Prevalence and intensity of infection: 100% (32 fish parasitized of 32 fish examined); 6–11 nematodes.

Deposition of voucher specimens: A total of twelve voucher specimens (six adult female and six male) were deposited in the Helminthological Collection of the Institute of Parasitology, the Biology Centre of the Czech Academy of Sciences, České Budějovice, Czech Republic (IPCAS N-1030).

Deposition of sequences: Sequence data obtained were deposited in GenBank: 28S rRNA (OR096360–OR096361), cox1 (OR088887–OR88888).

Comments. Reports of Campana-Rouget (1961), Puylaert (1973) and Vassiliadès and Troncy (1974) did not record any measurements on this parasite, but the morphology of specimens of the present material is in agreement with their descriptions. Morphometrics of the taxonomic relevant features of R. gendrei from the present study is within the ranges recorded by Moravec (1972) who gave a redescription of the same nematode from B. duchesnii.

3.2. Molecular analyses

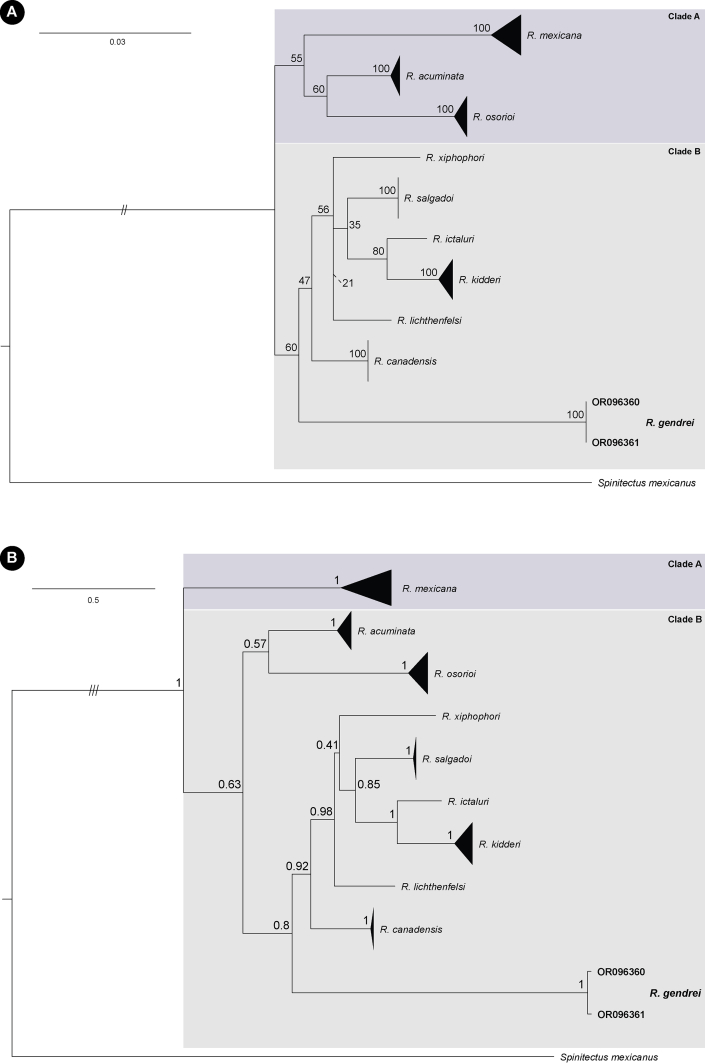

Novel sequences of the 28S rRNA and cox1 were successfully generated for two isolates of R. gendrei. The alignment of the 28S rRNA included sequences of nine species of Rhabdochona from the Neotropical and Nearctic regions. Tree topologies for the ML and BI analyses of the 28S rRNA region were incongruent. Both tree topologies provide support for the monophyly of the genus. The ML analysis (Fig. 5A) recovered Rhabdochona acuminata (Molin, 1860) and Rhabdochona osorioi Santacruz Vázquez, Ornelas-García et Pérez-Ponce de León, 2019 as sister group to Rhabdochona mexicana Caspeta- Mandujano, Moravec et Salgado-Maldonado, 2000 (Clade A) and R. gendrei, from the present study, in the basal position to the remaining species of Rhabdochona (Clade B), with low support values. Similarly, the BI analyses (Fig. 5B) recovered R. gendrei, with moderate to high posterior probability support, in the basal position of the taxa in Clade B.

Fig. 5.

Phylograms of the 28S rRNA gene region based on the A– maximum likelihood and B – Bayesian Inference analyses. Bootstrap and posterior probability support values are presented along branch nodes. The branch length was reduced to two (//) and three (///) times the scale bar.

The primary difference between the ML and BI topologies is in the sister position of R. acuminiata + R. osorioi in the respective clades. Sequences of thirteen species of Rhabdochona were included in the alignment for the cox1 region. ML and BI analyses recovered different tree topologies. The BI analyses recovered R. gendrei as the sister taxon to R. mexicana and, R. acuminata + R. osorioi as a sister clade to R. mexicana + R. gendrei. Rhabdochona juliacarabiasae Caspeta-Mandujano, Salinas-Ocampo, Suárez-Rodríguez, Martínez-Ramírez et Matamoros, 2021 as basal to all ingroup taxa with high posterior probability support values (Fig. 6). The ML tree recovered (not shown) provided low resolution with no nodal support. Interspecific divergence of R. gendrei to congeners ranged between 7.1 and 10.9% (31–130 base pair differences) and 8.4–13.0% (39–67 base pair differences) for the 28S rRNA (Table S1) and cox1 (Table S2) regions, respectively.

Fig. 6.

Bayesian inference phylogram of the cox1 mitochondrial gene region. Posterior probability support values are presented along branch nodes.

4. Discussion

The morphology of the present specimens, particularly the number of anterior prostomal teeth (Fig. 2A, 4A-C), spicules (left and right) (Fig. 2C-F, 3A-B) are more indistinguishable from the inadequately described R. gendrei by Campana-Rouget (1961) who originally described the parasite from Barbus sp., B. altianalis (now L. altianalis), B. duchesnii (now L. intermedius) and B. bynni (now L. bynni) (Cyprinidae) from Zaïre (now DRC) in Lakes Albert, Edward and Kivu, and by Moravec (1972) from B. duchesnii (now L. intermedius) from Lake Kivu in DRC.

Moravec (1972) reported that the number of anterior prostomal teeth is the most important taxonomic feature for species of Rhabdochona. This study recorded 14 anterior prostomal teeth on both the male and the female as observed from the apical view using SEM (Fig. 2, Fig. 4A), which agrees with Puylaert (1973) and the redescription by Moravec (1972) who re-examined Campana-Rouget (1961) specimens using light microscopy and recorded same number of teeth. Moravec (2010) argues that the exact number of teeth in Rhabdochona species can only be determined in apical view and most ideally by use of SEM. The number of anterior prostomal teeth for this nematode is resolved with SEM as 14. Since the cephalic end of R. gendrei had never been examined apically by SEM, the present study findings update the light microscopy observation by Campana-Rouget (1961).

Fig. 4.

Rhabdochona (Rhabdochona) gendreiCampana-Rouget (1961) from Labeobarbus altianalis (Boulenger, 1900), scanning electron micrographs of a female. A (deirids shown by white circle), B, C – cephalic end dorsolateral and anterior views; D– lateral view of the excretory pore (as shown by white arrow); E − detail of vulva sub-ventral view; F, G – fully mature (larvated) eggs dissected out of the nematode body; H – tail tip (white arrows shows openings with a papilla); Abbreviations: a – amphids; c – submedian cephalic papilla; pt – anterior prostomal teeth.

The current study also reports biforked/bifurcate deirid that is reduced in adult males (Fig. 2B). Simple deirids were recorded for the female as observed in Fig. 4A. Our findings are in agreement with bifurcate deirids previously reported by Gendre (1922); Campana-Rouget (1961) and Moravec (1972), but the present study emphasises its reduced nature.

Further, the present study conforms with the findings of Moravec (2010), Campana-Rouget (1961) and Moravec (1972) that the right spicule progressively surrogates the function of the gubernaculum becoming boat-shaped (Fig. 2, Fig. 3A, B). This study recorded the presence of a dorsal barb on the distal end of the shorter (right) spicule (Fig. 2F) following enzymatic digestion and examination under SEM. This structure was recorded by Mashego (1990) as being present on Rhabdochona esseniae collected from Barbus spp. in South Africa. The presence of this structure shows the need to re-examine the type specimens of inadequately described R. esseniae to verify the presence of the dorsal barb under SEM.

Fig. 3.

Rhabdochona (Rhabdochona) gendreiCampana-Rouget (1961) from Labeobarbus altianalis (Boulenger, 1900), light micrographs of an adult male. A – left (longer) and right (shorter) spicules (dorsolateral view); B– left (longer) and right (shorter – showing the boat-like shape) spicules (ventrolateral view); black and white arrows indicate left and right spicules respectively.

The use of SEM in this study revealed some differences with earlier studies (Campana-Rouget, 1961; Moravec, 1972) in terms of pre and postanal papillae with 10–12 pairs of preanal papillae recorded (Fig. 2C): 11 subventral and one pair lateral (at the level of the third subventral pair when counted from the cloaca opening). A total of six pairs of postanal papillae were revealed: of which five pairs are subventral and one pair is lateral lying along the same side of the first postanal papillae (when counted from the cloaca opening) (see Fig. 2D). This one lateral pair was previously recorded by Moravec (1972) as being the second pair of the postanal papillae, with other remaining five pairs (I, III, IV, V, and VI pairs subventral).

The shape and structure of the male and female tail is a good specific taxonomic character in Rhabdochona species. In the present study a conical shape, with a sharp terminal cuticular spike was noted in both sexes of this species (Fig. 2, Fig. 4H). This is in agreement with studies of Campana-Rouget (1961) and Moravec (1972).

A detailed study of fully mature (larvated) eggs dissected out of the nematode body (Fig. 4F–G) did not reveal any possible presence of superficial structures on them (e.g., filaments, other gelatinous formations). The shape of the egg looked oval, smooth, and relatively wide. One end of some of the eggs is provided with protuberance (opercula) Fig. 4F–G). This conforms with the previous record of Moravec (1972, 2019).

Through the use of molecular markers, R. gendrei could successfully be identified as a separate species among congeners. Tree topologies obtained for the 28S region in the present study yielded similar results to Santacruz et al. (2020) with two main clades. In their analyses, Santacruz et al. (2020) recovered two main clades, with R. osorioi as a sister to R. acuminata + R. mexicana. However, in our analyses, the position of R. mexicana was either recovered as a separate paraphyletic clade with R. acuminata + R. osorioi as the sister clade (Fig. 5A) or as basal to all ingroup taxa (Fig. 5B), and the position of R. acuminata + R. osorioi could not be resolved. From the analyses of the cox1 mitochondrial region, R. gendrei was recovered with strong posterior probability support as the sister taxon to R. mexicana that positioned with R. acuminata + R. osorioi as a sister clade (Fig. 6). Rhabdochona juliacarabiasae was recovered as basal to all ingroup taxa, which is contrasting to Lagunas-Calvo et al. (2019), Santacruz et al. (2020) and Caspeta-Mandujano et al. (2021) who recovered R. xiphophori, R. salgadoi and R. mexicana as the basal taxon to all the ingroup taxa, in their respective analyses.

Apart from Caspeta-Mandujano et al. (2021) that included all species with cox1 sequence data and recovered a different tree topology than in the present study, it is clear that the phylogenetic relationship between species of Rhabdochona is still unresolved. No apparent grouping according to endemicity, host preference or zoogeographic region was observed. Moreover, no grouping according to morphological characters is considered to be of taxonomic relevance, such as the number of prostomal teeth, shape of the deirids, presence or absence of superficial formation on eggs, shape of the distal tip of larger spicule and number of post cloacal papillae in males were observed for any of the taxa included in the analyses. Consequently, the phylogenetic relationship of the more than 100 species in the genus from across the globe would need to be supplemented to attempt a more robust and complete analysis. We highly recommend the inclusion of molecular data in future studies on all rhabdochonid species, in particular those from Africa, to facilitate robust classical taxonomic and complimentary phylogenetic analyses.

5. Conclusions

The use of SEM in this study adds to the available LM reports by giving a concise number of anterior prostomal teeth, preanal and postanal papillae as follows, for the male: 14 anterior prostomal teeth; 12 pairs of preanal papillae: 11 subventral and one lateral; six pairs of postanal papillae: five subventral and one lateral, with the latter pair at level of first sub-ventral pairs when counted from cloacal aperture and the presence of a dorsal barb on the distal end of the shorter right spicule. For the female: 14 anterior prostomal teeth and absence of superficial structures on fully mature (larvated) eggs dissected out of the nematode body. Both the 28S rRNA and cox1 gene regions prove to be effective markers in delineation at the species level of rhabdochonids. Rhabdochona gendrei could successfully be placed as a separate species from the available sequence data of Neotropical and Nearctic rhabdochonid species. It should be noted that it is imperative that time and resources are allocated to include complementary approaches, such as in the present study, to define species characters at the material and molecular level to facilitate future studies on this parasitic group and to resolve taxonomic and systematic discrepancies that may arise when restricted data (i.e., geographic, host range) is available to include in analyses.

Declaration of competing interest

None.

Acknowledgements

This work is based on the research supported partly by the Department of Science and Innovation (DSI) and the National Research Foundation (NRF) of South Africa (Grant Number 101054). The funder had no role in the manuscript writing, editing, approval or decision to publish and therefore, accepts no liability whatsoever in this regard.

The authors would like to thank Dr Elijah M. Kembenya (Kenya Marine and Fisheries Research Institute-Sangoro station) for his assistance during field collections. Special thanks to the students Ms Joan M. Maraganga (MSc. Limnology) and Mrs Gladys N. J. Rindoria (BSc Fisheries and Aquaculture) from Kisii University Department of Fisheries and Aquaculture, Ms Judy K. Rindoria (Wildlife Research and Training Institute – Naivasha campus) for your support in collection and examination of the specimens in the laboratory. Special thanks to Professor Frantiŝek Moravec for helping in the preliminary identification of the nematode and sending us scans of old articles on Rhabdochona species. The Spectrum Analytical Facility at the University of Johannesburg is acknowledged for providing infrastructure for acquiring scanning electron micrographs.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ppaw.2023.06.002

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the supplementary data to this article:

Table S1. Matrix showing nucleotide genetic divergence values among sequences of the 28S rRNA gene region of Rhabdochona spp. included in the phylogenetic analyses. Values below the diagonal indicate p-distance (in percentage) and values above the diagonal represent the number of differences in nucleotides. Newly generated sequences are in bold.

Table S2. Matrix showing nucleotide genetic divergence values among sequences of the cox1 mitochondrial gene region of Rhabdochona spp. included in the phylogenetic analyses. Values below the diagonal indicate p-distance (in percentage) and values above the diagonal represent the number of differences in nucleotides. Newly generated sequences are in bold.

References

- Altschul S.F., Gish W., Miller W., Myers E.W., Lipman D.J. Basic local alignment Search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baylis H.A. Some parasitic worms, mainly from fishes, from Lake Tanganyika. Ann. Mag. Nat. Hist. Ser. 1928;101:552–562. [Google Scholar]

- Campana-Rouget Y. Nématodes de Poissons. Résultats scientifiques de l’exploration hydrobiologique des lacs Kivu. Édouard et Albert. 1961;3:1–61. 1952–1954. [Google Scholar]

- Capella-Gutiérrez S., Silla-Martínez J.M., Gabaldón T. trimAl: a tool for automated alignment trimming in large-scale phylogenetic analyses. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1972–1973. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casiraghi M., Anderson T.J.C., Bandi C., Bazzocchi C., Genchi C.A. Phylogenetic analysis of filarial nematodes: comparison with the phylogeny of Wolbachia endosymbionts. Parasitology. 2001;122:93–103. doi: 10.1017/S0031182000007149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspeta-Mandujano J.M., Moravec F., Salgado-Maldonado G. Spinitectus mexicanus n. sp. (Nematoda: cystidicolidae) from the intestine of the freshwater fish Heterandria bimaculata in Mexico. J. Parasitol. 2000;86:83–88. doi: 10.1645/0022-3395(2000)086[0083:SMNSNC]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspeta-Mandujano J.M., Salinas-Ocampo J.C., Suárez-Rodríguez R., Martínez-Ramírez C., Matamoros W.A. Morphological and molecular evidence for a new rhabdochonid species, Rhabdochona (nematoda: Rhabdochonidae), parasitizing Eugerres mexicanus (perciformes: gerreidae), from the lacantún river in the biosphere reserve of montes azules, chiapas, Mexico. Rev. Mex. Biodivers. 2021;92 doi: 10.22201/ib.20078706e.2021.92.3266. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Černotíková E., Horák A., František M. Phylogenetic relationships of some spirurine nematodes (Nematoda: chromadorea: Rhabditida: spirurina) parasitic in fishes inferred from SSU rRNA gene sequences. Folia Parasitol. 2011;58:135–148. doi: 10.14411/fp.2011.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chabaud A.G. Rhabdochona srivastavai n. sp., a parasitic nematode of a gobiid from Madagascar. H.D. Srivastava Commememoration. Indian Vet. Res. Inst. 1970:307–310. [Google Scholar]

- Choudhury A., Nadler S.A. Phylogenetic relationships of spiruromorph nematodes (Spirurina: spiruromorpha) in North American freshwater fishes. J. Parasitol. 2018;104:496–504. doi: 10.1645/17-195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darriba D., Taboada G.L., Doallo R., Posada D. jModelTest 2: more models, new heuristics and parallel computing. Nat. Methods. 2012;9:772. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dos Santos Q.M., Avenant-Oldewage A. Soft tissue digestion of Paradiplozoon vaalense for SEM of sclerites and simultaneous molecular analysis. J. Parasitol. 2015;101:94–97. doi: 10.1645/14-521.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Froese R., Pauly D., editors. FishBase. World Wide Web Electronic Publication. 2022. https://www.fishbase.se/summary/Labeobarbus-altianalis.html/ [Google Scholar]

- Gendre E. Notes d’helminthologie africaine (sixième note) Proceed.Verbaux Soc. Linnean Bordeaux. 1922;73:148–156. [Google Scholar]

- Guindon S., Gascuel O. A simple, fast, and accurate algorithm to estimate large phylogenies by maximum likelihood. Syst. Biol. 2003;52:696–704. doi: 10.1080/10635150390235520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S., Stecher G., Tamura K. MEGA7: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2016;33:1870–1874. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msw054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagunas-Calvo O., Santacruz A., Hernández-Mena D.I., Rivas G., Pérez-Ponce de León G., Aguilar-Aguilar R. Taxonomic status of Rhabdochona ictaluri (Nematoda: Rhabdochonidae) based on molecular and morphological evidence. Parasitol. Res. 2019;118:441–452. doi: 10.1007/s00436-018-6189-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mashego S.N. A new species of Rhabdochona Railliet, 1916 (nematoda: Rhabdochonidae) from Barbus species in South Africa. Ann. Transvaal Mus. 1990;35:147–149. [Google Scholar]

- Mejía-Madrid H.H., Vázquez-Domínguez E., Pérez-Ponce de León G. Phylogeography and freshwater basins in central Mexico: recent history as revealed by the fish parasite Rhabdochona lichtenfelsi (Nematoda) J. Biogeogr. 2007;34:787–801. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2699.2006.01651.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miller M.A., Pfeiffer W., Schwartz T. 2010. Creating the CIPRES Science Gateway for Inference of Large Phylogenetic Trees. Gateway Computing Environments Workshop (GCE) pp. 1–8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moravec F. General characterization of the nematode genus Rhabdochona with a revision of the South American species. Věstn. Českoslov. Spol. Zool. 1972;35:29–46. 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Moravec F. Rhabdochona puylaerti sp. n. (nematoda: Rhabdochonidae) recorded from the african viper Causus rhombeatus (lichtenstein) Folia Parasitol. 1983;30:313–317. 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Moravec F. Some aspects of the taxonomy and biology of adult spirurine nematodes parasitic in fishes: a review. Folia Parasitol. 2007;54:239–257. doi: 10.14411/fp.2007.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moravec F. Some aspects of the taxonomy, biology, possible evolution and biogeography of nematodes of the spirurine genus Rhabdochona Railliet, 1916 (Rhabdochonidae, Thelazioidea) Acta Parasitol. 2010;55:144–160. doi: 10.2478/s11686-010-0017-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moravec F. Academia; Prague, Czech Republic: 2019. Parasitic Nematodes of Freshwater Fishes of Africa; pp. 278–301. [Google Scholar]

- Moravec F., JirKů M. Rhabdochona spp. (Nematoda: Rhabdochonidae) from fishes in the Central African Republic, including three new species. Folia Parasitol. 2014;88:55–62. doi: 10.14411/fp.2014.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moravec F., Říha M., Kuchta R. Two new nematode species, Paragendria papuanensis sp. n. (Seuratoidea) and Rhabdochona papuanensis sp. n. (Thelazioidea), from freshwater fishes in Papua New Guinea. Folia Parasitol. 2008;55:127–135. doi: 10.14411/fp.2008.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nation J.L. A new method using hexamethyldisilazane for preparation of soft insect tissues for scanning electron microscopy. Stain Technol. 1983;58:347–351. doi: 10.3109/10520298309066811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okeyo D.O., Ojwang W.O. A photographic guide to freshwater fishes of Kenya. 2015. https://www.seriouslyfish.com/publications/ Available at:

- Puylaert F.A. Rhabdochonidae parasites de poisons africains d’eau douce et discussion sur la position syste matique de ce groupe. Rev. Zool. Bot. Afr. 1973;87:647–665. [Google Scholar]

- Rambaut A. University of Edinburgh, Institute of Evolutionary Biology; Edinburgh, UK: 2018. FigTree v.1.4.4 Molecular Evolution, Phylogenetics and Epidemiology.http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtree/ Available at: [Google Scholar]

- Rindoria N.M., Dos Santos Q.M., Avenant-Oldewage A. Additional morphological features and molecular data of Paracamallanus cyathopharynx (Nematoda: camallanidae) infecting Clarias gariepinus (Actinopterygii: clariidae) in Kenya. J. Parasitol. 2020;106:157–166. doi: 10.1645/19-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santacruz A., Omelas-García C.P., Pérez-Ponce de León G. Diversity of Rhabdochona mexicana (Nematoda: Rhabdochonidae), a parasite of Astyanax spp. (Characidae) in Mexico and Guatemala, using mitochondrial and nuclear genes, with the description of a new species. J. Helminthol. 2019;94(e34):1–11. doi: 10.1017/S0022149X19000014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santacruz A., Ornelas-García C.P., Pérez-Ponce de León G. Incipient genetic divergence or cryptic speciation? Procamallanus (Nematoda) in freshwater fishes (Astyanax) Zool. Scripta. 2020;49:768–778. doi: 10.1111/zsc.12443. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schäperclaus W. Verlag; Berlin: Akademie: 1990. Fischkrankheiten. [Google Scholar]

- Vassiliadès G., Troncy P.M. Nématodes parasites des Poissons du bassin tchadien. Bull. Inst. Fr. Afr. Noire Ser. A. 1974;36:670–681. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.