Abstract

Background:

A scoping review of literature about the informed consent process for emergency surgery from the perspectives of the patients, next of kin, emergency staff, and available guiding policies.

Objectives:

To provide an overview of the informed consent process for emergency surgery; the challenges that arise from the perspectives of the patients, emergency staff, and next of kin; policies that guide informed consent for emergency surgery; and to identify any knowledge gaps that could guide further inquiry in this area.

Methods:

We searched Google Scholar, PubMed/MEDLINE databases as well as Sheridan Libraries and Welch Medical Library from 1990 to 2021. We included journal articles published in English and excluded non-peer-reviewed journal articles, unpublished manuscripts, and conference abstracts. The themes explored were emergency surgery consent, ethical and theoretical concepts, stakeholders’ perceptions, challenges, and policies on emergency surgery. Articles were reviewed by three independent reviewers for relevance.

Results:

Of the 65 articles retrieved, 18 articles were included. Of the 18 articles reviewed, 5 addressed emergency informed consent, 9 stakeholders’ perspectives, 7 the challenges of emergency informed consent, 3 ethical and theoretical concepts of emergency informed consent, and 3 articles addressed policies of emergency surgery informed consent.

Conclusion:

There is poor satisfaction in the informed consent process in emergency surgery. Impaired capacity to consent and limited time are a challenge. Policies recommend that informed consent should not delay life-saving emergency care and patient’s best interests must be upheld.

Keywords: Informed consent, emergency surgery, patients, emergency staff

Introduction

Informed consent is a process of constant dialogue between the clinician or investigator whose purpose seeks to respect a patient’s wishes and values (autonomy) to ensure that the treatment is according to the patient’s choice and what the patient would like to be achieved from the treatment.1,2 The authorization given is considered “informed” when there is full disclosure by the physician as well as the patient’s understanding of the diagnosis, treatment options, and the possible risks and benefits. 1 According to the Declaration of Helsinki, informed consent for research must be given by an individual who is capable, must be voluntary, disclosure adequate, must be understood, and for an individual with impaired capability should be obtained from a legally approved representative. 3 Surgical consent involves continuous communication throughout the care of the patient and is not “an event or a signature on a form.” 4 According to the medical dictionary, emergency surgery is defined as a surgical procedure that cannot be delayed, for which there is no alternative therapy or surgeon, and for which a delay could result in death or permanent impairment of health. The informed consent that is required for patients undergoing emergency surgery is a challenge because the clinician is often faced with patients who are unable to provide informed consent. 5 Therefore, in an emergency, setting decisions for the patient may often have to be made by involving the family, society, or other caregivers through “a communitarian approach.” 6 However, in Western cultures like the United Kingdom and United States there are limits on who can legally give consent. 7

In emergency medicine where treatment decisions may have dramatic consequences for the individual patient’s life, it is particularly important that they should be based on the patient’s wishes and values. 8 The emergency physician finds that the ability to maintain the four Belmont report principles of ethical management of patients’ autonomy, non-maleficence, beneficence, and justice are put to the test in the surgical emergency room, where rapid decision-making is required.9,10 The decision-making is even more challenging in the worldwide problem of overcrowded emergency rooms where there are constraints in health service delivery like lack of privacy and confidentiality, treatment delays, and poor physician–patient communication.9,11

The informed consent process in the emergency room should be tailored by the surgeon with consideration for anxious patients who are required to make decisions with serious health and personal consequences. This often involves working with family members serving as surrogate decision-makers for patients who lack the capacity to take part in the informed consent process.12,13 In cases where the patient is unable to give informed consent the caregivers or next of kin if available, have to provide the informed consent. In such cases, the communitarian approach or model whereby decision-making goes beyond the doctor and patient to family, other health carers, and stakeholders in the medical decision-making may be employed. 6

This review aimed to describe the perceptions of the patients, next of kin, and emergency staff that affect the practice of informed consent for emergency surgery and the challenges of informed consent in an emergency surgical setting. This was to get a better understanding of the informed consent process for emergency surgery and to identify possible knowledge gaps that could guide further inquiry in this area.

Justification

What is known in this area of study?

Existing reviews have addressed emergency consent in the setting of developed world health systems.14–16

Previous systematic reviews have mainly addressed emergency invasive procedures not necessarily emergency surgery. 15

Other reviews have looked at observational studies comparing emergency versus elective surgery consent and not emergency surgery consent on its own. 14

What this study adds

There has been no review that addresses ethical and theoretical concepts, and guiding policies for emergency surgery informed consent. This review will look at articles addressing ethical and theoretical policies for emergency surgery consent.

Information about the perceptions of patients, next of kin/surrogate decision-makers, and emergency staff toward emergency surgery consent specifically

This review will demonstrate the knowledge gap caused by paucity of published research in emergency surgery informed consent practice in low-resource settings like countries in sub-Saharan Africa.

This scoping review may provide a guide to areas for further research in emergency surgery informed consent in terms of stakeholders’ perceptions and guiding policies in low-resourced settings. It will give an overview of how to get informed consent for emergency surgery, the challenges that arise, and how to improve communication of informed consent in an emergency setting.

Methods

The scoping review method that we utilized was proposed by Arksey and O’Malley (2005) and includes the following seven processes: (a) identify a research question, (b) identify relevant documents, (c) select documents, (d) chart data, (e) collate, (f) summarize and report results, and (g) consult with relevant stakeholders. We reviewed the literature on the informed consent process for emergency surgery in terms of stakeholders’ perceptions, ethical and theoretical concepts, challenges of emergency surgery informed consent, and policies about emergency surgery consent.

Registration and protocol

This was a scoping review of literature and did not meet the criteria for registration under Campbell, nor PROSPERO (prospective register of systematic reviews) which considers systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Although this review was not a systematic review, we wrote the review according to PRISMA-ScR (preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and scoping reviews) guidelines. 17

Eligibility criteria

We included only journal articles published in English and excluded non-peer-reviewed journal articles, unpublished manuscripts, and conference abstracts. Search terms used were Informed consent emergency surgery; Patients, next of kin, surrogate decision makers, surgeons; emergency Informed consent policies; and ethical and theory emergency surgery informed consent. The content covered was under the themes of emergency surgery consent, ethical and theoretical concepts of informed consent, stakeholders’ perceptions to informed consent, challenges of emergency surgery consent, and policies on emergency surgery consent. Studies that had outcomes about patients, next of kin, and emergency staff understanding and satisfaction with informed consent process for emergency surgery were included.

Information sources and search strategy

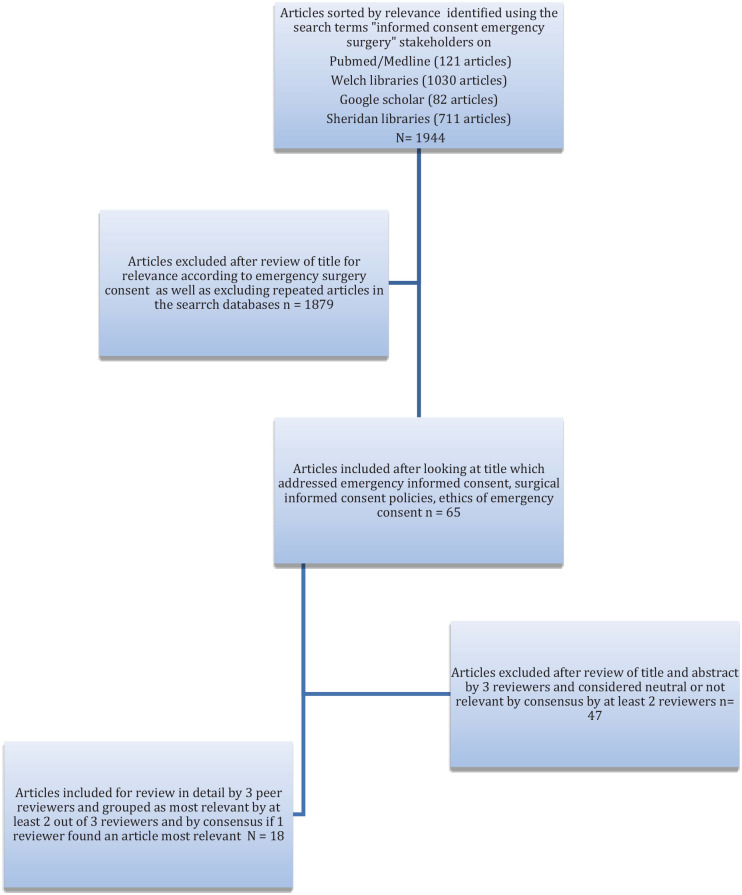

We reviewed literature between 1st July 2021 and 30th August 2021, from online journal articles from 1980 to 2021 using online search engines PubMed/MEDLINE, Google Scholar, Sheridan Libraries, Welch Medical Library, and ScienceDirect. Search terms used were informed consent emergency surgery; patients, next of kin, surrogate decision makers, surgeons; emergency informed consent policies; and ethical and theory emergency surgery informed consent. The search results were summarized in a PRISMA flow chart (Figure 1). Electronic search strategy for literature about stakeholders using Google Scholar used the search terms “emergency surgery” “informed consent” stakeholders, since 2021, and review articles sorted according to most relevant and this yielded 82 results. The titles of the articles were reviewed and relevant articles were selected, and articles that were repeated in other search databases were excluded.

Figure 1.

Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews (PRISMA) chart for article selection.

Study selection

Overall, 65 articles were identified using the above search terms. The abstracts for these articles were then reviewed independently for relevance by three peers (OK, EM, and MH) and conflicts were resolved for some articles where there was varying opinion on relevance. We narrowed down to 18 articles after the review by the 3 peer reviewers.

Data abstraction

We reviewed the articles’ abstracts and extracted data about the type of study, study population, study design, country of study, year of publication, and content covered. The primary outcomes studied were stakeholders’ perspectives (patient, next of kin, surrogate decision-makers, and emergency unit staff), ethical and theoretical policies addressing emergency consent, and emergency consent challenges. The content of the articles was coded according to five themes and these being challenges of emergency informed consent, ethical and theoretical concepts of emergency informed consent, stakeholders’ perspectives, emergency surgery consent, and policies on emergency informed consent.

Quality appraisal

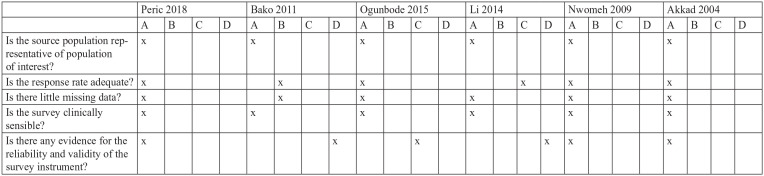

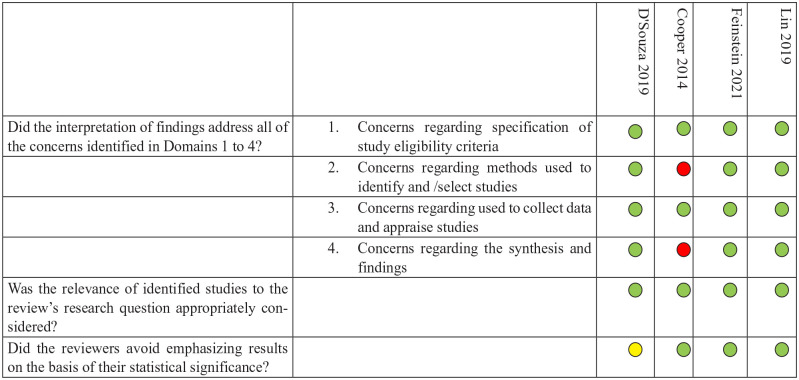

We assessed risk of bias of the cross-sectional studies using the risk of bias instrument for cross-sectional surveys of attitudes and practices by the CLARITY group at McMaster University 18 (Figure 2). Risk of bias assessment of systematic reviews (ROBIS) tool 19 was used to assess the systematic and literature review articles’ conclusions as supported by the evidence of the studies (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

CLARITY risk of bias assessment for cross-sectional studies.

A, definitely yes; B, probably yes; C, probably no; D, definitely no.

Figure 3.

Risk of bias assessment for systematic reviews.

Yes,

Yes,  Maybe,

Maybe,  No

No

Results

There were a total of 1944 articles with relevant titles that were found using the search terms “informed consent emergency surgery” using PubMed, Google Scholar, Welch Medical Library, and Sheridan Libraries. After reviewing the titles and abstracts for relevance and excluding repeated articles in the different databases, 65 articles were identified and further reviewed independently by 3 peer reviewers for relevance. There were five articles that had conflicting reviews for relevance and after consensus discussion two were excluded. A total of 18 relevant journal articles were finally included in the review. The results of these studies were presented in a table showing the authors, research article title, year published, country of study, content covered, themes, study design/type, and study population and summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Relevant articles selected and reviewed.

| Author(s) | Research title | Year published | Country | Content covered | Theme | Study type | Study population |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D’Souza et al. 14 | Room for improvement: a systematic review and meta-analysis on the informed consent process for emergency surgery | 2019 | Not specified | Emergency versus elective informed consent | Emergency informed consent Stakeholders’ perceptions to emergency informed consent |

Systematic review of observational studies | Patients |

| Perić et al. 20 | Patients’ experience regarding informed consent in elective and emergency surgeries | 2018 | Bosnia Herzegovina | Elective versus emergency surgery consent | Emergency informed consent Stakeholders’ perceptions to emergency informed consent |

Prospective cross-sectional study | Patients |

| Davoudi et al. 21 | Challenges of obtaining informed consent in emergency ward: a qualitative study in one Iranian hospital | 2017 | Iran | Challenges of emergency consent | Stakeholders’ perceptions to emergency informed consent Challenges of emergency surgery |

Qualitative study | Patients, patients’ attendants, emergency nurses, and physicians |

| Bako et al. 22 | Informed consent practices and its implication for emergency obstetrics care in Azare, North-Eastern Nigeria | 2011 | Nigeria | Emergency obstetric consent Outcomes of delayed consent |

Emergency informed consent | Cross-sectional study | Obstetric emergency patients |

| Feinstein et al. 15 | Informed consent for invasive procedures in the emergency department | 2021 | USA | Consent for emergency invasive procedures | Stakeholders’ perceptions to emergency informed consent | Systematic review | Pediatric patients, parents of pediatric patients, emergency physicians, adult patients, and family of patients |

| Moskop 23 | Informed Consent and refusal of treatment: Challenges for emergency physicians | 2006 | Doctrine emergency informed consent | Stakeholders’ perceptions to emergency informed consent Ethical and theoretical concepts Challenges of emergency consent |

Ethical review | Emergency physicians | |

| Muskens et al. 24 | When time is critical, is informed consent less so? A discussion of patient autonomy in emergency neurosurgery | 2019 | Emergency neurosurgery consent | Ethical and theoretical concepts of emergency informed consent Challenges of emergency consent |

Moral opinion Ethical review |

Patients, surrogate decision-makers, and neurosurgeons | |

| Ogunbode et al. 25 | Informed consent for caesarean section at a Nigerian university teaching hospital: patients’ perspective | 2015 | Nigeria | Emergency versus elective caesarean section consent | Stakeholders’ perceptions to emergency informed consent | Cross-sectional study | Patients, and next of kin (husbands) |

| Li et al. 26 | Informed consent for emergency surgery—how much do parents truly remember? | 2014 | Singapore | Recall of surgical complications | Challenges of emergency consent | Prospective cohort | Next of kin (parents) |

| Paduraru et al. 27 | Emergency surgery on mentally impaired patients: standards in consenting | 2018 | Paternalism in emergency consent Policies of emergency consent in mentally impaired patients |

Challenges of emergency consent Policies on emergency consent |

Review article | Patients, emergency physicians, and policy-makers | |

| Nwomeh et al. 28 | A parental educational intervention to facilitate informed consent for emergency operations in children | 2009 | USA | Consent tool | Stakeholders’ perceptions to emergency informed consent | Case-control study | Next of kin (parents) |

| Nwomeh et al. 29 | Portable computer assisted parental education facilitates informed consent for emergency operations in children | 2007 | USA | Emergency consent Consent tool |

Stakeholders perceptions | Case-control study | Next of kin (parents) |

| Borak et al. 30 | Informed consent in emergency setting | 1984 | Policy guidelines in emergency consent | Policies on emergency consent Challenges of emergency consent |

Ethical review | Patients and emergency staff | |

| Lawton et al. 31 | Written versus verbal consent: a qualitative study of stakeholder views of consent procedures used at the time of recruitment into a peripartum trial conducted in an emergency setting | 2017 | The Netherlands, UK | Obstetric emergency research consent | Stakeholders’ perceptions to emergency informed consent | Qualitative study | Patients and emergency staff |

| Lin et al. 16 | How to effectively obtain informed consent in trauma patients: a systematic review | 2019 | Ireland, UK, Taiwan, Turkey, USA, and Korea | Emergency trauma consent | Emergency consent Challenges of emergency consent |

Systematic review | Patients and emergency staff |

| Akkad et al. 32 | Informed consent for elective and emergency surgery: questionnaire study | 2004 | UK | Emergency versus elective | Stakeholders’ perceptions to emergency informed consent | Cross-sectional survey | Patients |

| Moore et al. 33 | What emergency physicians should know about informed consent: legal scenarios, cases, and caveats | 2014 | Legal aspects of special scenarios informed consent | Policies on emergency consent | Ethical review | Emergency staff | |

| Cooper et al. 34 | Pitfalls in communication that lead to nonbeneficial emergency surgery in elderly patients with serious illness | 2014 | Emergency consent communication | Challenges of emergency surgery consent | Literature review | Elderly patients |

Of the 18 articles that were reviewed, 5 studies were literature reviews and systematic reviews,14–16,28,34 4 were cross-sectional studies,22,25,31,32 2 were qualitative studies,21,31 3 were ethical articles,24,27,30 2 were cohort/case-control studies,26,29 and 2 were review articles.23,33 The themes explored in these studies were emergency consent, ethical and theoretical concepts of informed consent, stakeholders’ perceptions to informed consent, challenges of emergency surgery consent, and policies on emergency surgery consent. The study populations were elderly patients, emergency obstetric surgery, neurosurgery, orthopedics, trauma, pediatric abdominal surgery, and emergency invasive procedures. There were only two studies from sub-Saharan Africa, and these were both from Nigeria.22,25

Informed consent for emergency surgery

All the articles addressed emergency informed consent in the broader context making comparisons between consent for emergency surgery versus elective surgery. These looked at patient satisfaction with the informed consent process; factors interfering with the consent process like pain, fatigue, analgesic medications, and patient recall; and understanding of the consent process. There was an appreciation of informed consent process for emergency obstetric surgery in one study while another study highlighted the consequences of delay in giving consent in obstetric emergencies. The emergency informed consent process needed to be improved by making it more structured and standardized and evaluating its effectiveness in trauma patients with adequate training of healthcare professionals to be able to provide structured comprehensive information to patients undergoing emergency surgery.

Stakeholder perceptions

A total of 6 articles evaluated stakeholders’ perceptions to the emergency consent process with most of these looking at the perspective of the patients and the emergency staff. The articles studied patient perspectives on informed consent to emergency surgery and assessed patient recall, 26 patient understanding to emergency surgery in obstetric,31,32 neurosurgical procedures, 24 invasive emergency procedures, 15 and pediatric surgery. 28 Overall, it was reported that there was poor recall and understanding for patients undergoing emergency surgery compared with those undergoing elective surgery. For surrogate decision-making, a review article on patients and surrogate decision-makers’ experiences with patients undergoing emergency invasive procedures showed that the informed consent process for pediatric emergency surgery needed to include obtaining assent from the children to increase their sense of control and engagement in their health. Qualitative studies assessed patient satisfaction, surrogate decision-makers, and emergency staff attitudes to the informed consent process for emergency surgery with comparisons between elective and emergency procedures. Most studies reported poor patient satisfaction with the emergency informed consent process, although one study among obstetric patients showed patient satisfaction with the emergency surgery consent.

Challenges of emergency informed consent

The challenges of emergency informed consent were discussed in six articles. These challenges were highlighted with respect to emergency room physicians, neurosurgery patients, mentally impaired patients, elderly patients, trauma patients, and pediatric patients and centered around patient recall and understanding of the informed consent and patient autonomy in emergency settings. The challenges identified were limited time for consent, patient’s impaired capacity to consent, difficulty for the physician to determine the best interests of the patient, and patient’s ability to recall the information provided during the informed consent process.16,23,24,26,27,30 One of the articles proposed the use of laptops during the consent process to improve patients and/or surrogate decision-makers’ understanding of the information provided during the informed consent process for emergency surgery. 29

Ethical and theoretical concepts

There were three articles which addressed ethical concepts of emergency informed consent, but no article specifically addressed theoretical concepts of informed consent for emergency surgery. The ethical concepts discussed were chiefly related to the principle of respect for patient’s autonomy, which may be impaired by the patient’s capacity to make an informed decision as well as limited time for consent in the setting of emergency surgery for patients with impaired capacity to consent.23,24,27 Recommendations for the ethical management of informed consent in emergency neurosurgery that were made included ensuring that an autonomous decision by a capable patient is always respected, risks and benefits of the surgery are adequately communicated to the patient or the surrogate decision-makers, and that informed consent should be waived only when the benefit from the expected procedure would result in poor outcomes if there was delay due to the informed consent process in an incompetent patient. 24 This article referred to policies like the Consent to Treatment Policy of the United Kingdom National Health Service addressing situations when consent may be waived.

Policies on emergency consent

Two articles addressed policies on emergency informed consent. In the United Kingdom, capacity to consent for patients with impaired competence was discussed, and the health professional was expected to use medical council guidelines and the Mental Capacity Act Code to assess capacity to consent in these patients while upholding the patient’s best interests. Legislation and guidelines in the United Kingdom and the United States state that it is the physician’s overall responsibility to make decisions in the best interest of the non-competent or unconscious adult patient based on evidence from prior wishes expressed by the patient, other involved professionals, and the patients’ relatives, and in some cases with the involvement of legally appointed representatives. 27 Physicians also need to familiarize themselves with the legal requirements, policies, and council guidelines, where available, pertinent to emergency informed consent. These may vary from state-to-state in the United States and nation-to-nation. 30

Discussion

This discussion describes the findings of the scoping review in terms of the perceptions of the patients, next of kin, and emergency staff that affect the practice of informed consent for emergency surgery and the challenges of informed consent in an emergency surgical setting. We discuss emergency consent in general, ethical, and theoretical concepts of emergency surgery consent, stakeholders’ perceptions, challenges of emergency surgery consent, and policies addressing emergency consent.

Emergency consent

Informed consent in the emergency setting has challenges where the principle of respect for patient autonomy may be difficult to achieve. The patient may not be able to give informed consent because of diminished capacity, anxiety, pain, and severe illness in a stressful environment, which affects the patient’s ability to give voluntary consent or have the capacity to understand the information given to him to enable decision-making and authorization of care.14,16,35 Surrogate decision-makers, next of kin, or legally appointed representatives may have to be employed to provide consent under such circumstances once impaired capacity to consent has been established following an assessment for capacity to consent by the doctor. However, there are limitations in understanding and recalling information provided during the consent process by even the surrogate decision-makers. A study of parents recall in the informed consent process for children undergoing emergency appendectomy showed that “overall parent recall and comprehension of surgical complications was poor” despite the best efforts of the surgeons. 26 Some patients who have the capacity to consent will in an emergency setting waive their rights to consent and allow the physician to make the decision for them. 36 Even when the patient has the capacity to provide informed consent, findings from a meta-analysis of consent in emergency surgery showed that a lower rate of these patients read the informed consent documents. 14

Studies comparing the informed consent process for emergency and elective surgery showed that patients perceived that informed consent process for emergency surgery is less comprehensive than that of elective surgery.14,22,37 This was attributed to the insufficient time to discuss the consent and for a healthcare professional to explain the consent form, which in some studies was perceived to be difficult to understand, and the discussion of the risks and complications of emergency surgery versus elective surgery. Criteria used by some surgeons to determine the importance of informed consent in an emergency surgery can be categorized under three principles: equality, utility, and justice. 38 Equality means that every individual has an equal life value and chance to be receive the required care. The principle of utility is where actions are to create the greater good for the greatest number of individuals. The principle of justice refers to prioritizing the greatest emergency or the patient in greatest danger. Informed consent might not be obtained when a patient is in a clearly life or death situation and such situations need to be well documented. 38 Indeed, in patients with diminished capacity requiring emergency surgery and in the absence of surrogate decision-makers or legally appointed representatives, the responsibility rested upon the surgeon to provide the treatment in the best interest of the patient without the patient giving informed consent. 27 This is similar in the United States.39,40

Ethical or theoretical concepts

Informed consent is based on the bioethical principle of respect for autonomy. 10 Moskop et al. 23 concluded that in an emergency setting, respect for patient autonomy was important and that appropriate information and informed consent should be obtained from the patient in spite of the emergency physician not having prior understanding of a patient’s values and preferences. In spite of the lack of time and the questionable capacity to consent that may challenge respect for patient autonomy during the informed consent process in an emergency setting, Muskens et al. 24 recommended that patient autonomy should always be respected. The consent process can be viewed using the fair transaction model in which moral transformation is achieved by promoting the consenter/patient’s interests and facilitating mutually beneficial interactions between the patient and the doctor. 41 Fair transaction model described in this article refers to the interaction between the doctor and the patient being based on making a fair decision based on what is in the interest of the patient and a better understanding of what is good for the patient while considering the doctor’s point of view during the informed consent process. Ethical decision-making in surgery has been described using five roots which outline the moral experiences between the surgeon and the patient. These are rescue, proximity, ordeal, aftermath, and presence. Rescue (the power to offer life-saving care), proximity (the great access the patient gives to the surgeon during surgery), ordeal (the extreme experience of surgery), and aftermath (the lasting effects of the surgery) are from the patient’s experience or perspective while presence is in the surgeon’s role during the patient’s experience.42,43

There was no article that addressed theoretical concepts of informed consent in emergency surgery, and the articles mainly discussed ethical principles guiding the informed consent process in general. There is no single theoretical method that can be employed to discuss consent because of the complexity and different perspectives by which consent is understood. Authors not included in this scoping review like Alderson and Goodey 44 discuss the theoretical concepts of how consent is understood in a broader sense. They have described consent as real consent, critical consent, functionalist consent, constructed consent, and postmodern choice. 44 Real consent is considered to be the exchange of medicolegal facts, constructed consent is where consent is looked at as a complex non-singular event, critical consent is when consent is seen as a vital protection, functionalist consent considers consent as a formality while postmodern choices looks at the choice made in itself. 44 The informed consent process especially in emergency surgery leans toward the constructionist theory in which one looks at the perspectives, experiences, and the influence of social factors in the decision-making process during informed consent.

Stakeholders’ perceptions to the informed consent process

Overall, it was reported that there was poor patient recall and understanding for patients undergoing emergency surgery compared with those undergoing elective surgery. Most studies reported poor patient satisfaction with the emergency informed consent process although one study among obstetric patients showed patient satisfaction with the emergency surgery consent.

The informed consent process has other stakeholders beside the patient, these being surrogate decision-makers or the next of kin, legally appointed representatives, healthcare workers, and medical institution administrators. In an emergency setting these various stakeholders have to maintain the ethical principle of preserving the patient’s autonomy and working in the patient’s best interest while balancing other ethical principles of equitable care in social justice and individual versus societal benefit in resource-limited settings. Studies about shared decision-making outlined the roles of family members and the society and the benefits of a communitarian approach toward the informed consent process among patients undergoing surgery especially in an emergency setting.6,4,15,22,25 Nevertheless, the individualistic approach to patient’s autonomy versus the communitarian approach in the decision-making process varies culturally, whereby the individualist approach, is used in Western cultures while the communitarian approach often termed as “Ubuntu,” is used in African and Asian cultures. 45

Patients’ perceptions of the informed consent from various studies comparing the process in elective and emergency surgery showed that there was dissatisfaction in the process, poor understanding of the risks and complications of surgery, and poor recall of the information provided during the consent process.14,26,32,36 These findings were also similar to what was reported by Ochieng et al. 46 among patients undergoing elective surgery in Uganda, a resource-limited low- and middle-income country. In this study, patients’ perceptions of what constituted informed consent for elective surgery were diverse and many patients underwent surgery without knowledge of the identity of the surgeon or the reason for the surgery. 46 Another qualitative study in Iran showed that often there is a paternalistic approach to providing informed consent in an emergency setting, which results in a less patient-centered consent process. 21 However in another study conducted in an Eastern European country, patients undergoing emergency and elective surgery expressed equal satisfaction in the informed consent process. 20 A study among patients who underwent emergency oral surgery interestingly showed that although most patients wanted to know the complications of their surgery, 10% did not want to know this information. 47 This perspective highlights the complexity of how much information patients would like to receive in an emergency setting. It has been suggested that variations in patient perspectives caused by differences in timing of care and the institutional support given can be controlled by carrying out qualitative outcome studies in different settings at different times. 13

Patients who need emergency surgery may be incapacitated and decisions on their care may have to be made by surrogate decision-makers or their next of kin together with the surgeon.48,49 Surrogate decision-makers base their decisions on “the patient’s known wishes, substituted judgments and the patient’s best interests” to preserve the patient’s autonomy. 50 However, a study on the perspectives of surrogate decision-makers of patients in a surgical ICU revealed that often the surrogate decision-makers have not received any prior information about their roles and responsibilities from the healthcare providers and so may make their decisions based on personal perceptions and experiences. 49 A study among parents of children who were due to undergo emergency appendectomy found that the use of a power point presentation to provide information about the surgery improved preoperative communication and understanding of the procedure. 28 Studies have reported that just like patients, surrogate decision-makers may sign consent forms without adequate understanding of the benefits or risks of the care given. Other studies have shown that when the timing for the informed consent process is deferred to a time when the patient is stable, the surrogate decision-makers have a better understanding of the research intervention to be done in cases of emergency room research. 51 The prognosis of patients undergoing emergency surgery is often uncertain and changes rapidly, 49 making it a challenge for the physician to disclose this information to surrogate decision-makers. However, a multicentric study on surrogate decision-makers’ perspectives about information on prognosis showed that they preferred that physicians provide information about the prognosis even when the physician was uncertain of the prognosis. 52 The surrogate decision-makers sometimes also have to deal with the stress of not knowing whether they are actually fulfilling the patient’s wishes as well as the responsibility for the outcomes of their decisions, especially if the outcome is not good. Qualitative studies have shown increased levels of post-traumatic stress disorders among them as a result. 53

Challenges to emergency surgery consent

Our review found that informed consent in an emergency setting has constraints of time and urgency of treatment with potentially life-changing and even uncertain outcomes, coupled with a patient who might not have the capacity to provide the consent. 24 In low- and middle-income countries like Uganda there is overcrowding in emergency rooms of public hospitals resulting in limited resources 54 which may result in inadequate time to provide informed consent for emergency surgery. Informed consent is sometimes not obtained, may be deferred, or may be obtained through a legally appointed surrogate in some emergencies, if delays in obtaining the consent could prevent the patient from getting urgently required life-saving treatment, if the patient has waived their rights to consent, or if the patient is not competent to understand the informed consent process.27,35,36 Sometimes emergency surgery is defined as surgery that needs to take place within 24 h of diagnosis. This then allows for detailed discussion and adequate time for informed consent to be obtained and for decisions to be made. However, unlike elective surgery consent where the condition might not be immediately life-threatening, informed consent for emergency surgery often needs to be given in a short time because of the immediate life-threatening situation requiring a life-saving surgery.

Furthermore, consent for emergency research in an emergency setting such as obstetric emergencies, where alternate methods for providing consent other than written consent are sometimes employed, may result in unintended ethical and logistical challenges for the emergency staff who provide information during the informed consent process. 31 However even in such situations, effort should be made to obtain informed consent with adequate disclosure about the risks and alternative treatment options especially where the treatment has more than minimal risk to the patient. D’Souza et al. 14 found that in studies among patients undergoing emergency surgery, only 20% of patients were able recall information about surgical complications and risks that was disclosed during the consent process because of the limited time for consent, the risk period having elapsed, and often complicated information.

Emergency department patients have reduced autonomy because they often do not have a choice as to where they should receive care and are presenting at these units for the first time. In addition to this, informed consent has to be obtained quickly by the doctor who has no prior knowledge of the patient’s wishes or preferences. 23 In certain emergency surgical conditions, patients’ capacity to provide consent is diminished and yet life-saving treatment may be required. An example of this is in neurosurgical patients who are incapacitated by their illness, have inadequate time for required information to be given to them, and sometimes do not have any surrogate decision-maker to provide consent. In such a scenario the surgeon takes on the responsibility to decide on care in the patient’s best interest. 24 Surgeons also find it challenging to make rapid and deliberate decisions in acute and emergency surgery settings, especially when they are alone, and this affects their ethical judgment, which is required when providing information during the informed consent process. 55 Communication during emergency situations is affected by time constraints, inadequate communication skills of the person providing information as well as patient, and surrogates making it more difficult to explore and integrate patients’ preferences for emergency surgery decisions. 34

Policies on emergency consent

Legislation and guidelines state that it is the physician’s overall responsibility to make decisions in the best interest of the patient based on evidence from prior wishes expressed by the patient, other involved professionals, and the relatives of the patient, and in some cases with the involvement of legally appointed representatives. 27 In the United Kingdom, consent for emergency treatment can be obtained from the patient and “where it is not possible to obtain consent, doctors should provide treatment that is in the patient’s best interests and is immediately necessary to save life or avoid significant deterioration to the patient’s health.” 56 In the United States, state laws allow the physician to provide emergency care without express consent and should be acting in the best interest of the patient, as long as the complications of the procedure can be defended legally. 33 In South Africa, general practice and ethical guidelines for informed consent for health practitioners and researchers state that, in an emergency setting, consent is expected to be obtained because “the circumstances explaining the inability to obtain consent may be too vague for a practitioner to defend him/herself against claims against not obtaining informed consent.” 57 However the South African law requires the healthcare provider to act in the best interest of the patient in emergency cases when the patient lacks the capacity to consent and has no surrogate decision-maker. 58 In Uganda, Uganda National Council of Science and Technology national guidelines state that informed consent might be waived if a research participant presents in an emergency situation and informed consent cannot be reasonably obtained from the individual or his/her representative. 59 In the Uganda Medical and Dental Practitioners’ Council Code of professional ethics, a practitioner shall not “conduct any intervention or treatment without consent except where a bonafide emergency obtains.” 60

Physicians therefore need to familiarize themselves with the legal requirements, policies, and council guidelines, where available, pertinent to emergency informed consent. These may vary from state-to-state and nation-to-nation. 30 It is, however, debatable as to whether regulatory, legal, and ethical policies like assessing a patient’s competence or capacity to provide informed consent that require implementation and documentation are practicable in an emergency setting. 61

Strengths

This scoping review shows the challenges that surround informed consent for emergency surgery and highlights the need to consider different approaches to ensure that the patient’s autonomy is considered. The perspectives of the stakeholders are the key in deriving satisfaction in the informed consent process. This review draws attention to the need to research on the informed concent process in the developing world especially sub-Saharan Africa to appreciate the communitarian and the individualistic approaches to decision-making during the informed consent process.

Limitations and weaknesses

One of the major limitations of this review was the limiting of literature search to only articles written in English. We found only one publication from sub-Saharan Africa, which might make the findings of this scoping review not applicable to low-resource settings. It was assumed that the healthcare provider will know and act in the best interest of the patient in an unbiased professional way without providing guidance on how one knows what should be considered as the best interest of the patient. Also, literature published in the early 1990s may not be aligned with that published in the 2020s, as informed consent practices have evolved over the decades and some information might have been missing from earlier publications.

Best practices

The informed consent process for emergency surgery needs to be highlighted in the training of emergency doctors and nurses. Regular refresher courses can be done to address the different challenges that arise at different times during the consent process. Policies guiding this process need to be developed with the guidance of the institutional ethics committees to guide emergency staff on how to foster ethical practice, and protect patient autonomy especially in situations where patients’ capacity to consent is impaired like surgical emergencies. Patients and their next of kin can be sensitized about their rights through messages placed in the emergency departments as posters or notices to create awareness of their rights and how to get help or information about their rights.

Research agenda

This review shows that there is a paucity of studies on informed consent for emergency surgery in low-resource settings like sub-Saharan Africa. Research in sub-Saharan Africa could provide better understanding of how limited resources affect emergency informed consent process practice and the stakeholders’ perception of emergency informed consent in these settings. It could also be useful to study how decision-making during the informed consent process is influenced by the cultures and norms that are within this region which might vary with the Western culture.

There was little research published about policies on informed consent in emergency directly. Policies on informed consent were general and not specific to emergency surgery consent. Research needs to be done to help develop policies specific to consent for emergencies in collaboration with research ethics committees at institutional and national levels.

Educational implications

Informed consent practices for emergencies like surgery where the patient may lack the capacity to consent need to be incorporated into the training of medical students and nurses. There should be information provided about national and/or institutional guiding policies where available, and these should be readily available for referencing in the emergency departments. Refresher training of emergency staff can be done regularly by institutional research and ethics committees and professional medical councils to update staff on how to manage the evolving challenges encountered during emergency informed consent. Patient education about their rights during emergencies can be done through civil rights bodies, ministry of health government bodies, and advice on how to get this information provided within the emergency departments of the health institutions.

Conclusion

Stakeholders’ perceptions are centered around patients, next of kin, or surrogate decision-makers’ ability to recall, understand information within a limited time, resulting in poor satisfaction in the informed consent process in emergency surgery as compared with elective surgery. Emergency staff face the challenge of providing adequate information while respecting the patients’ autonomy and ensuring that the informed consent process does not delay life-saving emergency care. When there is impaired capacity to consent, the best interest of the patient must be upheld within the available legal and ethical frameworks and policies.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-smo-10.1177_20503121231176666 for Informed consent process for emergency surgery: A scoping review of stakeholders’ perspectives, challenges, ethical concepts, and policies by Olivia Kituuka, Ian Guyton Munabi, Erisa Sabakaki Mwaka, Moses Galukande, Michelle Harris and Nelson Sewankambo in SAGE Open Medicine

Acknowledgments

I acknowledge the support of Dr Joe Ali of Johns Hopkins University who provided guidance on the concept of this article and aided in getting access to the various online journal articles. I also acknowledge the support of the Berman Institute of Bioethics faculty at Johns Hopkins University for providing support toward training in Bioethics and developing the concept of this article. Research reported in this publication was supported by the Fogarty International Center of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number D43TW010892. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Author contributions: OK conducted the literature search, reviewed articles, and drafted the article. EM reviewed the articles for relevance, reviewed, and revised the article. IA reviewed and revised the article. MH reviewed articles for relevance, reviewed, and revised the article. MG reviewed and revised the article. NS reviewed and revised the article, provided guidance on writing up the article.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This research was supported by the Fogarty International Center of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number D43TW010892 under the Makerere University international Bioethics Research and Training program. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

ORCID iDs: Olivia Kituuka  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7779-4035

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7779-4035

Erisa Sabakaki Mwaka  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1672-9608

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1672-9608

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1.Hall DE, Prochazka AV, Fink AS.Informed consent for clinical treatment. CMAJ 2012; 184(5): 533–540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abaunza H, Romero K.Elements for adequate informed consent in the surgical context. World J Surg 2014; 38: 1594–1604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Medical Association. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA 2013; 310(20): 2191–2194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bernat JL, Peterson LM.Patient-centered informed consent in surgical practice. Arch Surg 2006; 141(1): 86–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tisherman SA.Defining community and consultation for emergency research that requires an exemption from informed consent. AMA J Ethics 2018; 20(5): 7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mendel J.The patient, the doctor and the family as aspects of community: new models for informed consent. Monash Bioeth Rev 2007; 26: 68–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Code of Federal Regulations, 45 CFR 46.117, 46 Sect. 45 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Naess A-C, Foerde R, Steen PA.Patient autonomy in emergency medicine. Med Health Care Philos 2001; 4(1): 71–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aacharya RP, Gastmans C, Denier Y.Emergency department triage: an ethical analysis. BMC Emerg Med 2011; 11(1): 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beauchamp TL, Childress JF. (eds.). Principles of biomedical ethics. 8th ed.Oxford, London: Oxford University Press, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barish RA, McGauly PL, Arnold TC.Emergency room crowding: a marker of hospital health. Trans Am Clin Climatol Assoc 2012; 123: 304–311. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McCullough LB, Jones JW.Unravelling ethical challenges in surgery. Lancet 2009; 374(9695): 1058–1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peterson LM.Human values in the care of the surgical patient. Arch Surg 2000; 135(1): 46–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.D’Souza RS, Johnson RL, Bettini L, et al. (eds.). Room for improvement: a systematic review and meta-analysis on the informed consent process for emergency surgery. Mayo Clin Proc 2019; 94: 13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Feinstein MM, Adegboye J, Niforatos JD, et al. Informed consent for invasive procedures in the emergency department. Am J Emerg Med 2021; 39: 114–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lin Y-K, Liu K-T, Chen C-W, et al. How to effectively obtain informed consent in trauma patients: a systematic review. BMC Med Ethics 2019; 20(1): 1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med 2018; 169(7): 467–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.CLARITY Group. Tool to assess risk of bias in case-control studies. Canada: McMaster University, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Whiting P, Savović J, Higgins JPT, et al. ROBIS: a new tool to assess risk of bias in systematic reviews was developed. J Clin Epidemiol 2016; 69: 225–234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Perić O, Tirić D, Penava N.Patients’ experience regarding informed consent in elective and emergency surgeries. Med Glas (Zenica) 2018; 15(2): 179–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Davoudi N, Nayeri ND, Zokaei MS, et al. Challenges of obtaining informed consent in emergency ward: a qualitative study in one Iranian hospital. Open Nurs J 2017; 11: 263–276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bako B, Umar N, Garba N, et al. Informed consent practices and its implication for emergency obstetrics care in Azare, north-eastern Nigeria. Ann Med Health Sci Res 2011; 1(2): 149–158. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moskop JC.Informed consent and refusal of treatment: challenges for emergency physicians. Emerg Med Clin North Am 2006; 24(3): 605–618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Muskens IS, Gupta S, Robertson FC, et al. When time is critical, is informed consent less so? A discussion of patient autonomy in emergency neurosurgery. World Neurosurg 2019; 125: e336–e340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ogunbode O, Oketona O, Bello F.Informed consent for caesarean section at a Nigerian university teaching hospital: patients’ perspective. Trop J Obstet Gynaecol 2015; 32(1): 55–63. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li FX, Nah SA, Low Y.Informed consent for emergency surgery—how much do parents truly remember? J Pediatr Surg 2014; 49(5): 795–797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Paduraru M, Saad A, Pawelec K.Emergency surgery on mentally impaired patients: standard in consenting. J Mind Med Sci 2018; 5(1): 16–20. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nwomeh BC, Hayes J, Caniano DA, et al. A parental educational intervention to facilitate informed consent for emergency operations in children. J Surg Res 2009; 152(2): 258–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nwomeh BC, Caniano DA, Upperman JS, et al. 72: portable computer assisted parental education facilitates informed consent for emergency operations in children. J Surg Res 2007; 137(2): 181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Borak J, Veilleux S.Informed consent in emergency settings. Ann Emerg Med 1984; 13(9): 731–735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lawton J, Hallowell N, Snowdon C, et al. Written versus verbal consent: a qualitative study of stakeholder views of consent procedures used at the time of recruitment into a peripartum trial conducted in an emergency setting. BMC Med Ethics 2017; 18(1): 1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Akkad A, Jackson C, Kenyon S, et al. Informed consent for elective and emergency surgery: questionnaire study. BJOG 2004; 111(10): 1133–1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moore GP, Moffett PM, Fider C, et al. What emergency physicians should know about informed consent: legal scenarios, cases, and caveats. Acad Emerg Med 2014; 21(8): 922–927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cooper Z, Courtwright A, Karlage A, et al. Pitfalls in communication that lead to nonbeneficial emergency surgery in elderly patients with serious illness: description of the problem and elements of a solution. Ann Surg 2014; 260(6): 949–957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.O’Neill O.Some limits of informed consent. J Med Ethics 2003; 29(1): 4–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Boisaubin EV, Dresser R.Informed consent in emergency care: illusion and reform. Ann Emerg Med 1987; 16(1): 62–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kay R, Siriwardena A.The process of informed consent for urgent abdominal surgery. J Med Ethics 2001; 27(3): 157–161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Timofte D, Ionescu L, Danila R, et al. The principle of informed consent in emergency surgery—equivocal situation in making life-saving decisions. Rev Rom Bioet 2015; 13(2): 279–289. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bhimani AD, Macrinici V, Ghelani S, et al. Delving deeper into informed consent: legal and ethical dilemmas of emergency consent, surrogate consent, and intraoperative consultation. Orthopedics 2018; 41(6): e741–e746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schweikart SJ.Who makes decisions for incapacitated patients who have no surrogate or advance directive? AMA J Ethics 2019; 21(7): 587–593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Miller FG, Wertheimer A. Preface to a theory of consent transactions: beyond valid consent: In: The ethics of consent: Theory and practice. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2009, pp.79–106. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Little M.The fivefold root of an ethics of surgery. Bioethics 2002; 16(3): 183–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vanderpool HY.Surgeons as mirrors of common life: a novel inquiry into the ethics of surgery. Tex Heart Inst J 2009; 36(5): 449–450. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Alderson P, Goodey C.Theories of consent. BMJ 1998; 317(7168): 1313–1315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ekmekci PE, Arda B.Interculturalism and informed consent: respecting cultural differences without breaching human rights. Cultura (Iasi) 2017; 14(2): 159–172. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ochieng J, Buwembo W, Munabi I, et al. Informed consent in clinical practice: patients’ experiences and perspectives following surgery. BMC Res Notes 2015; 8(1): 765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Degerliyurt K, Gunsolley JC, Laskin DM.Informed consent: what do patients really want to know? J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2010; 68(8): 1849–1852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Brewster LP, Palmatier J, Manley CJ, et al. Limitations on surrogate decision-making for emergent liver transplantation. J Surg Res 2012; 172(1): 48–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lilley EJ, Morris MA, Sadovnikoff N, et al. “Taking over somebody’s life”: experiences of surrogate decision-makers in the surgical intensive care unit. Surgery 2017; 162(2): 453–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Berger JT, DeRenzo EG, Schwartz J.Surrogate decision making: reconciling ethical theory and clinical practice. Ann Intern Med 2008; 149(1): 48–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Woolfall K, Frith L, Gamble C, et al. How parents and practitioners experience research without prior consent (deferred consent) for emergency research involving children with life threatening conditions: a mixed method study. BMJ Open 2015; 5(9): e008522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Evans LR, Boyd EA, Malvar G, et al. Surrogate decision-makers’ perspectives on discussing prognosis in the face of uncertainty. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2009; 179(1): 48–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wendler D.The theory and practice of surrogate decision-making. Hastings Cent Rep 2017; 47(1): 29–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nseyo U, Cherian MN, Haglund MM, et al. Surgical care capacity in Uganda: government versus private sector investment. Int Surg 2018; 102(7–8): 387–393. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Torjuul K, Nordam A, Sørlie V.Ethical challenges in surgery as narrated by practicing surgeons. BMC Med Ethics 2005; 6(1): 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.British Medical Association. Consent and refusal by adults with decision making capacity—a toolkit for doctors. London: British Medical Association, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 57.South African Medical Association. General ethical guidelines for health researchers. South Africa: South African Medical Association, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Anthony S. In: Medical Protection Society (ed.), Consent to medical treatment in South Africa. South Africa: Medical Protection Society, 2011, p. 5. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Uganda National Council of Science and Technology. National guidelines for research involving humans as research participants. Kampala, Uganda: Uganda National Council of Science and Technology, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Uganda Medical and Dental Practitioners Council. Code of professional ethics. Kampala, Uganda: Uganda Medical and Dental Practitioners Council, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dahlberg J, Dahl V, Forde R, et al. Lack of informed consent for surgical procedures by elderly patients with inability to consent: a retrospective chart review from an academic medical center in Norway. Patient Saf Surg 2019; 13(1): 1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-smo-10.1177_20503121231176666 for Informed consent process for emergency surgery: A scoping review of stakeholders’ perspectives, challenges, ethical concepts, and policies by Olivia Kituuka, Ian Guyton Munabi, Erisa Sabakaki Mwaka, Moses Galukande, Michelle Harris and Nelson Sewankambo in SAGE Open Medicine