This noninferiority randomized clinical trial evaluates the effect of using no fixation on recurrence rates among patients undergoing open retromuscular ventral hernia repair.

Key Points

Question

Is no transfascial suture fixation of retromuscular mesh noninferior to transfascial suture fixation in open retromuscular ventral hernia repair (RVHR)?

Findings

In this registry-based randomized clinical trial of 325 adults with a ventral hernia defect width of 20 cm or less with fascial closure, not fixating the mesh in open RVHR was found to be noninferior to fixation.

Meaning

It is safe to abandon transfascial mesh fixation in this population of patients undergoing open RVHR.

Abstract

Importance

Transfascial (TF) mesh fixation in open retromuscular ventral hernia repair (RVHR) has been advocated to reduce hernia recurrence. However, TF sutures may cause increased pain, and, to date, the purported advantages have never been objectively measured.

Objective

To determine whether abandonment of TF mesh fixation would result in a noninferior hernia recurrence rate at 1 year compared with TF mesh fixation in open RVHR.

Design, Setting, and Participants

In this prospective, registry-based, double-blinded, noninferiority, parallel-group, randomized clinical trial, a total of 325 patients with a ventral hernia defect width of 20 cm or less with fascial closure were enrolled at a single center from November 29, 2019, to September 24, 2021. Follow-up was completed December 18, 2022.

Interventions

Eligible patients were randomized to mesh fixation with percutaneous TF sutures or no mesh fixation with sham incisions.

Main Outcome and Measures

The primary outcome was to determine whether no TF suture fixation was noninferior to TF suture fixation for open RVHR with regard to recurrence at 1 year. A 10% noninferior margin was set. The secondary outcomes were postoperative pain and quality of life.

Results

A total of 325 adults (185 women [56.9%]; median age, 59 [IQR, 50-67] years) with similar baseline characteristics were randomized; 269 patients (82.8%) were followed up at 1 year. Median hernia width was similar in the TF fixation and no fixation groups (15.0 [IQR, 12.0-17.0] cm for both). Hernia recurrence rates at 1 year were similar between the groups (TF fixation, 12 of 162 [7.4%]; no fixation, 15 of 163 [9.2%]; P = .70). Recurrence-adjusted risk difference was found to be −0.02 (95% CI, −0.07 to 0.04). There were no differences in immediate postoperative pain or quality of life.

Conclusions and Relevance

The absence of TF suture fixation was noninferior to TF suture fixation for open RVHR with synthetic mesh. Transfascial fixation for open RVRH can be safely abandoned in this population.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03938688

Introduction

The transfascial (TF) fixation of mesh with percutaneous sutures in open retromuscular ventral hernia repairs (RVHR) is a common practice and one currently under debate. Open RVHR with mesh was originally described with use of TF sutures for mesh fixation, which were purportedly necessary for keeping the mesh flat to allow ingrowth and to take tension off of the midline fascial closure.1,2,3,4,5 These theories led surgeons to believe mesh fixation may play a role in preventing hernia recurrence.5 Despite this, there are some potential downsides to TF suture fixation, including increased time in surgery and greater postoperative pain, and little evidence supports the notion that TF sutures offload midline tension or improve mesh ingrowth.2,6,7,8,9 Given the lack of clarity or objective data around the impact of TF sutures, we aimed to evaluate the effect of using no fixation on hernia recurrence rates, compared with our standard of care of placing slowly absorbing TF sutures.

Our study aims to evaluate the effect of using no fixation on recurrence rates compared with our standard of care of using TF sutures. We hypothesize that hernia recurrence rates for patients who receive no fixation will be noninferior to those receiving TF sutures.

Methods

Study Design and Oversight

This is a prospective, registry-based, double-blinded, noninferiority, parallel-group randomized clinical trial (RCT) comparing TF suture fixation of mesh with no fixation of mesh in patients undergoing open RVHR. The Abdominal Core Health Quality Collaborative served as the platform for data collection. Patient enrollment and operations were conducted at the Cleveland Clinic Center for Abdominal Core Health (Main Campus, Cleveland Clinic Foundation, Cleveland, Ohio). All procedures were performed by 1 of 5 surgeons (C.C.P., D.M.K., S.R., M.J.R., or A.S.P.). The trial was conducted and analyzed in accordance with the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) guidelines for RCTs. Institutional review board approval was granted prior to enrollment, and all study participants provided written informed consent. The trial was not amended after initiation. The full protocol is available in Supplement 1.

Patients and Study Setting

Patients were eligible with a ventral incisional hernia width of 20 cm or less measured intraoperatively during elective open RVHR with mesh through a midline incision, with fascial closure required. Exclusion criteria included a defect with a maximal hernia width larger than 20 cm, a nonmidline approach, minimally invasive approaches, bridged repairs (anterior fascia not closed), mesh placements in a nonretromuscular position, and parastomal hernias. Patients were recruited from the surgeons’ clinics, and all procedures were performed at the Cleveland Clinic Main Campus. Race and ethnicity data were collected for every patient entered into the registry database, including those in the study.

Surgical Intervention

A standard RVHR was performed as previously described.4 After appropriate synthetic mesh was selected and placed into the retromuscular position, the patients were randomized. Those randomized to the mesh fixation group had eight No. 1 polydioxanone (PDS; Ethicon) TF sutures placed through 3-mm skin incisions in the lateral abdominal wall, using a laparoscopic suture passer. Patients randomized to the no fixation group had eight 3-mm sham counter incisions made at similar sites, and no suture fixation to the mesh (suture or sealant) was permitted. Care was taken to avoid buckling of the mesh during fascial closure.

Study Outcomes

The primary outcome of this study was the rate of pragmatic hernia recurrence at 1 year, determined by a weighted formula consisting of physical examination, computed tomographic scan, and the Hernia Recurrence Inventory (HRI) questionnaire as previously described by Krpata et al.10 The algorithm is available in eTable 1 in Supplement 2. One-year computed tomographic scans were recommended to all participants and were read by 5 enrolling surgeons (C.C.P., D.M.K., L.R.A.B., M.J.R., and A.S.P) who were all blinded to the operating surgeon, interventional group, or postoperative course. Consensus of 2 of 3 surgeons was required to determine presence or absence of hernia recurrence.

Secondary outcomes included postoperative pain, quality of life (QOL), and opioid consumption. Pain was assessed using the Numeric Pain Rating Scale (NRS-11) and Patient-Reported Outcome Measurement Information System (PROMIS) Pain Intensity short form (3a).11,12 The NRS-11 pain assessments were conducted at baseline, daily for the first 7 postoperative days, at 1 postoperative month, and at 1 postoperative year. The PROMIS Pain Intensity 3a scores were obtained at baseline and postoperatively at 1 month and 1 year. The NRS-11 measures current pain on a scale of 0 to 10, where 10 is the worst pain imaginable. The PROMIS Pain Intensity 3a questionnaire consists of 3 questions designed to assess pain over 1 week that are answered on a scale of 1 to 5, where 1 indicates no pain and raw scores are converted to T-scores, with higher values meaning more pain. Opioid consumption was measured by assessing in-hospital intravenous and oral opioid consumption converted to morphine millequivalents collected daily. Patient-reported total opioids consumed after discharge, measured using standard postoperative assessment forms from the Abdominal Core Health Quality Collaborative. Hernia-specific changes in QOL were measured by the Hernia-Related Quality-of-Life Survey (HerQLes), a validated 12-question survey obtained at baseline and postoperatively at 30 days and 1 year.10 The HerQLes score was converted to a summative score from 0 to 100, with higher scores representing improved QOL and abdominal wall function. Finally, patients were asked whether they believed they received TF suture fixation by asking the question, “Do you feel stitches are holding your mesh in place?” at the 30-day and 1-year follow-up points.

Data Collection

Clinical evaluation was conducted by the treating surgeon at 30 days (±15 days) and 1 year (±3 months) or additionally if complications occurred. Long-term follow-up was attempted in all patients. Patients were deemed lost to follow-up after 6 telephone calls without a response.

Power Calculation

Our study investigated the noninferiority of no TF fixation sutures compared with TF fixation sutures for 1-year hernia recurrence rates after RVHR. Hernia recurrence was chosen as the primary outcome instead of postoperative pain because we believed that a reduction in postoperative pain that was offset by an increased recurrence rate would not justify abandoning TF fixation. Our 1-year follow-up period was believed to adequately encompass technical failures that might be related to lack of mesh fixation. We estimated a 5% hernia recurrence rate based on a prior RCT evaluating mesh weight with routine TF suture fixation.13 Based on surgeon consensus, we determined a noninferiority margin of 10%. With an 80% power to detect a noninferiority margin difference of 10%, a sample size of 162 patients per arm was needed, and assuming loss to follow-up of 20%, the randomization goal was a total of 325 patients.

Randomization and Blinding

Patients were enrolled by treating physicians or qualified research personnel. Randomization was generated by a statistician (C.T.) and allocation was completed by a local research coordinator (K.C.M. and A.F.). Eligible patients were randomized in a 1:1 fashion in the operating room to either TF sutures or no TF sutures immediately after mesh placement. No stratification was performed. A central concealed randomization scheme was housed in Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) and used a random number of blocks. Investigators were blinded until the mesh was placed into the abdomen to limit selection bias on size of synthetic mesh and potential mesh overlap based on randomization allocation. Patients remained blinded until the conclusion of the study. Postoperative assessors remained blinded throughout the study period, and sham counterincisions were made in the no suture group to maintain blinding. One-year radiographic assessments were performed by blinded surgeons. This study was analyzed on an intention-to-treat basis for our primary outcome.

Statistical Analysis

Categorical variables were reported as frequencies and percentages. Continuous variables were reported as medians (IQRs). Patient characteristics and operative comparisons were summarized by the treatment group. For our primary analysis, hernia recurrence was considered a binary outcome (yes or no) and reported at 1 year. Prespecified covariates included for adjustment of our primary outcome were age, sex, American Society of Anesthesiologists class, body mass index, diabetes, smoking, use of immunosuppressants, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, recurrent hernia, hernia width, and history of an abdominal wall surgical site infection.

Testing for the noninferiority of recurrence rates was performed on an intention-to-treat basis and conducted by first converting the predetermined noninferiority margin of a 0.1-point difference to an odds ratio threshold of 2.00. Noninferiority was then determined by testing the upper boundary of the 95% CI for the difference in odds. If the 95% CI of the no fixation intervention lay entirely below the margin, noninferiority of the intervention would be concluded. A per-protocol analysis was also performed, where patients lost to follow-up were included as censored data, and hazard ratios were used as treatment effect estimation. Additionally, a time-to-event analysis was conducted to measure differences in recurrence between the 2 groups over the 1-year follow-up period to determine whether no fixation was associated with earlier technical failures.

Secondary outcomes of interest, as measured by the NRS-11 and PROMIS Pain Intensity 3a questionnaires, were compared using mean (SD) differences and tested using the likelihood ratio. Median differences were tested using differences in odds ratios using nonparametric approaches. The difference in mean scores at follow-up after surgery between groups was compared using linear mixed-effect models that include group × time interaction, prespecified covariates, and repeated measurements as random effects. For the QOL outcome, repeated measures were performed to determine the difference in the mean change in score from the preoperative assessment to the postoperative assessments for the HerQLes QOL instrument, controlling for baseline differences.

All statistical tests were 2-sided, and P < .05 was considered statistically significant. No adjustments were made for multiple comparisons, and secondary end points should be considered exploratory. Data were analyzed using R, version 4.0.0 (R Project for Statistical Computing). No imputations were performed for missing data. An independent data and safety monitoring board reviewed the safety and efficacy of the data at 100-patient intervals.

Results

Baseline Characteristics of Patients

Between November 29, 2019, and September 24, 2021, a total of 325 patients (140 men [43.1%] and 185 women [56.9%]; median age, 59 [IQR, 50-67] years) were randomized to either arm: 162 (49.8%) received mesh fixation (fixation group) and 163 (50.2%) received no mesh fixation (no fixation group) (a CONSORT diagram can be seen in Figure 1). The overall patient follow-up included 269 patients (82.8%) at 1 year. All eligible patients completed follow-up by December 18, 2022. All patients were well matched on baseline demographics and comorbidities (Table 1). There were no significant differences in operative characteristics between the groups (Table 2). Median hernia width was 15 (IQR, 12-17) cm for both groups.

Figure 1. CONSORT Diagram.

HRI indicates Hernia Recurrence Inventory; MIS, minimally invasive surgery.

Table 1. Patient Demographic Characteristics, Comorbid Conditions, and Hernia and Wound Characteristics.

| Characteristic | Patient groupa | |

|---|---|---|

| Fixation (n = 162) | No fixation (n = 163) | |

| Sex | ||

| Men | 64 (39.5) | 76 (46.6) |

| Women | 98 (60.5) | 87 (53.4) |

| Age, median (IQR), y | 59.5 (50.2-66.0) | 59.0 (49.0-67.0) |

| BMI, median (IQR) | 32.9 (29.0-36.3) | 33.0 (29.6-36.5) |

| Diabetes | 32 (19.8) | 45 (27.6) |

| Active smoking (within 30 d) | 15 (9.3) | 19 (11.7) |

| Immunosuppression | 10 (6.2) | 7 (4.3) |

| COPD | 19 (11.7) | 18 (11.0) |

| Recurrent hernia | 96 (59.3) | 87 (53.4) |

| History of abdominal wall SSI | 35 (21.6) | 35 (21.5) |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared); COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; SSI, surgical site infection.

Unless otherwise indicated, data are expressed as No. (%) of patients.

Table 2. Operative Details.

| Variable | Patient groupa | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fixation (n = 162) | No fixation (n = 163) | ||

| ASA class | |||

| 1 | 1 (0.6) | 1 (0.6) | .76 |

| 2 | 23 (14.2) | 25 (15.3) | |

| 3 | 136 (84.0) | 132 (81.0) | |

| 4 | 2 (1.2) | 5 (3.1) | |

| OR time, median (IQR), min | 332 (282-374) | 332 (280-370) | .90 |

| Wound status | |||

| Clean | 140 (86.4) | 143 (87.7) | .64 |

| Clean/contaminated | 17 (10.5) | 13 (8.0) | |

| Contaminated | 5 (3.1) | 7 (4.3) | |

| Transversus abdominus release performed | 160 (98.8) | 162 (99.4) | .56 |

| EHS classificationb | |||

| M1 (subxiphoidal) | 59 (36.4) | 48 (29.4) | .17 |

| M2 (epigastric) | 148 (91.4) | 147 (90.2) | .58 |

| M3 (umbilical) | 155 (95.7) | 159 (97.5) | .51 |

| M4 (infraumbilical) | 142 (87.7) | 148 (90.8) | .45 |

| M5 (suprapubic) | 37 (22.8) | 45 (27.6) | .34 |

| L1 (subcostal) | 4 (2.5) | 3 (1.8) | .69 |

| L2 (flank) | 6 (3.7) | 12 (7.4) | .15 |

| L3 (iliac) | 8 (4.9) | 12 (7.4) | .37 |

| L4 (lumbar) | 0 | 0 | NA |

| Hernia, median (IQR), cm | |||

| Width | 15 (12-17) | 15 (12-17) | .80 |

| Length | 23 (19-25) | 24 (20-26) | .18 |

| Mesh, median (IQR), cm | |||

| Width | 30 (30-40) | 30 (30-42.5) | .15 |

| Length | 30 (30-40) | 30 (30-40) | .14 |

| Mesh to defect ratio, median (IQR) | 2.3 (2.0-2.8) | 2.5 (2.0-2.9) | .44 |

Abbreviations: ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists; EHS, European Hernia Society; L, lateral; M, midline; NA, not applicable; OR, operating room.

Unless otherwise indicated, data are expressed as No. (%) of patients.

Each patient can have more than 1 M or L level.

Primary End Point

At 1 year, 132 of 162 patients (81.5%) in the fixation arm and 137 of 163 (84.0%) in the no fixation arm completed follow-up. All patients (n = 269) were evaluated with at least 1 modality of follow-up: 91 with HRI questionnaire only (46 [28.4%] in the fixation group and 45 [27.6%] in the no fixation group), 151 with clinical examinations (74 [45.7%] in the fixation group and 77 [47.2%] in the no fixation group), and 142 with radiographic evaluation (63 [38.9%] in the fixation group and 79 [48.5%] in the no fixation group). The intention-to-treat analysis demonstrated a hernia recurrence in 12 of 162 patients (7.4%) in the fixation group and 15 of 163 (9.2%) in the no fixation group (P = .70). Patient-reported bulge (HRI) accounted for 22 total recurrences, with 9 in the fixation and 13 in the no fixation groups. Three patients in the fixation and 2 in the no fixation groups experienced radiographic and clinical recurrence. Recurrence-adjusted risk difference was found to be −0.02 (95% CI, −0.07 to 0.04). The upper bound of the 95% CI of adjusted risk difference of 0.043 was less than our predetermined 0.10 margin, and noninferiority can be concluded. An additional sensitivity analysis was performed to determine the effect of those patients lost to follow-up showing that if the treatment group (no fixation) had 20% more recurrences among those lost to follow-up (3 patients), the upper boundary of the 95% CI would surpass our predetermined margin of 0.10 and our noninferiority conclusion would be overturned. A per-protocol analysis, which omitted the patients lost to follow-up, demonstrated a hernia recurrence of 12 of 132 patients [9.1%]) in the fixation group and 15 of 137 (10.9%) in the no fixation group with an adjusted risk difference of −0.02 (95% CI, −0.08 to 0.05) maintaining noninferiority. A secondary subanalysis showed no difference in time to recurrence at 1 year (eFigure in Supplement 2).

Secondary End Points

Pain and QOL

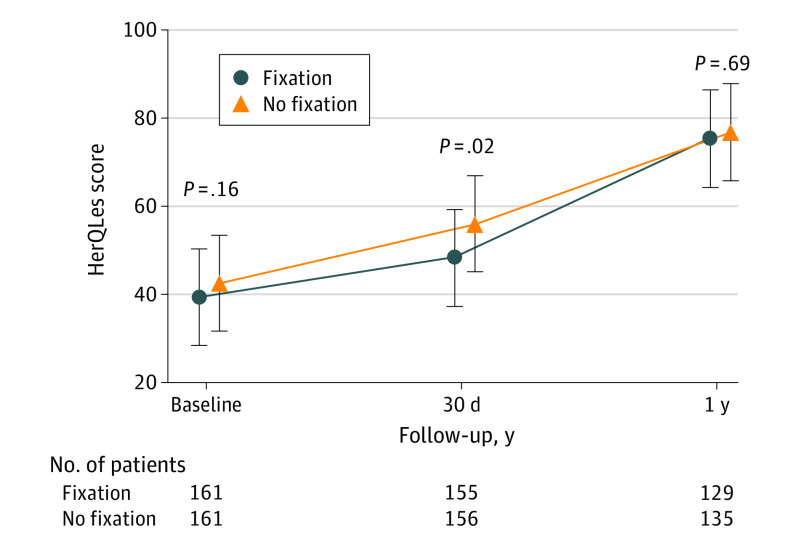

The analysis of pain as assessed by the NRS-11 and PROMIS Pain Intensity 3a scores revealed no significant differences between the 2 groups at any time point (Figure 2). There were no differences in total in-hospital intravenous and/or oral opioid consumption between the 2 groups with median morphine milliequivalents of 355 (IQR, 255-548) in the fixation group and 325 (IQR, 160-609) in the no fixation group (P = .45). At 30 days, opioid consumption was similar between the fixation and no fixation groups, with mean (SD) tablet use (oxycodone, 5 mg) of 19.4 (10.0) and 19.5 (11.3), respectively. Patients had similar baseline QOL measurements with improvements in both groups over time (Figure 3). Quality of life in the no fixation group was better at 30 days, as measured by the HerQLes questionnaire (median, 53.3 [IQR, 31.7-75.4] vs 41.7 [IQR, 23.3-66.7]; P = .02). There were no QOL differences at the 1-year time point. Length of stay was the same between the 2 groups, with a median of 5 (IQR, 4-7) days for each group (P > .99). There were no significant differences in the patient’s perception of feeling transfascial fixation sutures at 30 days and 1 year: 99 of 154 (64.3%) in the fixation group and 92 of 151 (60.9%) in the no fixation group responded yes to feeling sutures at 30 days (P = .63), and 72 of 132 (54.5%) in the fixation group and 69 of 140 (49.3%) in the no fixation group responded yes to feeling sutures at 1 year (P = .46).

Figure 2. Pain Scores.

A, Pain as measured by Patient Reported Outcome Measurement Information System (PROMIS) Pain Intensity short form scores at baseline and postoperatively at 30 days and 1 year. Three questions are answered on a scale of 1 to 5, where 1 indicates no pain; raw scores are converted to T-scores, with higher values meaning more pain. B, Pain as measured by Numeric Pain Rating Scale (NRS-11) scores at baseline and postoperative days (POD) 1 to 7 and 30 and 1 year. Scores range from 0 to 10, where 10 is the worst pain imaginable. Scores were significantly different on POD 1 and 6. Error bars represent 95% CIs. The number of patients represents how many individuals provided scores at each time point.

Figure 3. Quality of Life Measured by HerQLes Scores.

Scores range from 0 to 100, with higher scores representing improved quality of life and abdominal wall function. Error bars represent 95% CIs. The number of patients represents how many individuals provided scores at each time point.

30-Day Outcomes

At 30 days, there was a significant difference in surgical site occurrence (SSO) rates, with 7 of 136 patients (5.2%) in the fixation group vs 22 of 138 (15.9%) in the no fixation group (P = .007). In the no fixation group, the SSOs consisted of wounds with serous drainage (n = 6), superficial cellulitis (n = 6), seromas (n = 5), delayed healing wounds (n = 2), exposed mesh and superimposed surgical site infection (n = 2), and fascial disruption (n = 1); in the fixation group, SSOs included seromas (n = 4), hematomas (n = 2), and serous drainage from the wound (n = 1). There were no significant differences in recurrence, reoperation, or readmission rates at 30 days. The remainder of 30-day and 1-year outcomes are presented in eTables 2 and 3 in Supplement 2. Nine patients (2.8%) underwent reoperation and there were 5 deaths.

Discussion

In this RCT, we found that hernia recurrence rates for defects with a width of 20 cm or less among patients undergoing open RVHR with synthetic mesh were similar at 1 year, regardless of TF suture fixation or no fixation. Additionally, while TF sutures have been theoretically linked to postoperative pain, we found no differences in pain between the 2 groups regarding the NRS-11 and PROMIS Pain Intensity 3a questionnaires. Conducting this trial was greatly aided by using a registry-based model, of which we have prior experience with other completed trials. The registry allowed for rapid accrual of appropriate patients with collection of data and a patient follow-up schedule that was already in the routine practice of our surgeons. This allowed this trial to be performed with minimal additional infrastructure or overhead.

There are 3 main theoretical advantages of TF suture fixation for extraperitoneal mesh. First, fixation is thought to distribute the forces across the hernia repair and help offload tension on the midline, which might provide benefit, particularly in the early stages of wound healing. Second, the sutures are thought to help keep the mesh flat between the layers of the abdominal wall to aid with tissue incorporation. Third, the placement of sutures is promoted to prevent mesh migration in the early postoperative period.5 Despite these purported advantages of TF suture fixation, we did not observe any clinically significant deleterious effects associated with the abandonment of TF sutures regarding fascial dehiscence or early wound morbidity, despite a median defect size of 15.0 cm. However, we did identify a higher rate of minor wound morbidity in the no fixation group at 30 days. Whether this is related to technical issues with mesh placement and early inflammation is unknown and should be the focus of future studies. However, these wound issues were not associated with increased rates of 1-year mesh-related complications. Our findings challenge the notion that TF sutures are a requisite technical aspect of these operations, and we have abandoned them in our practice in patients meeting these criteria.

In the initial descriptions of retromuscular ventral hernia repair with mesh, TF suture fixation was promoted as a technique to offset tension on the midline repair and maintain a flat mesh during anterior fascial closure.14 While initial descriptions of this procedure promoted TF sutures, the necessity of these sutures has come into question.4 Using a formal posterior component separation with transversus abdominis release allows the surgeon to place a larger piece of mesh, and often overlap all bony areas and reach the medial border of the psoas muscle. Given this overlap, the value of securing the mesh in the lateral abdominal wall might not be as relevant.

A surprising finding in our study was the absence of a difference in pain between the 2 groups, which is further supported by our finding of similar in-hospital and postdischarge opioid consumption between the 2 groups. Importantly, pain at TF sites is the most cited reason for fixation abandonment by proponents of no TF sutures, likely because patients often localize their discomfort to the sides of their abdomens. Despite this, we noted similar rates of patients reporting suture sensation, and our findings led us to conjecture that pain in the lateral abdomen may be more related to the retromuscular dissection rather than the sutures themselves. Notably, our findings also support the clinical scenario in which a surgeon believes fixation may be warranted and suggest that TF sutures can be placed without concern for excessive short- or long-term pain or prolonged operative time. In particular, at extremes of the abdomen, including suprapubic and subxiphoid hernias in which fascial closure might not be adequate, sutures can be placed based at the discretion of the surgeon.

Importantly, the patients randomized to no TF sutures received no fixation of any kind, including glues and adhesives. As such, we cannot comment on the efficacy of adhesives in this population, as they were not studied. Despite this, our patients with hernias in notoriously challenging positions (subxiphoid and suprapubic) did not experience early failures of their repairs attributable to no fixation. We attribute this to attaining wide mesh overlap to the central tendon of the diaphragm and deep into the Retzius space when deemed necessary, which requires experience and expertise in advanced reconstructive techniques. Thus, these results must be interpreted with caution and may not be widely generalizable to all procedures for hernias in the subxiphoid and suprapubic positions. Even more notable is the morbidity associated with these major reconstructions, including reoperation in 9 patients (2.8%) and 5 deaths. Surgeons contemplating these types of repairs should carefully consider their training and resources available to care for these challenging cases.

Limitations

This study has some limitations that must be mentioned. Arguably, 1 year of follow-up may be considered an inadequate duration for the primary outcome of hernia recurrence. We selected this time point because the polydioxanone sutures we use for TF suture fixation dissolve between 4 and 6 months; therefore, it is likely that hernia recurrences related to the absence of sutures would occur within 1 year postoperatively. We also did not identify a pattern of earlier failures in the no fixation group. Still, we acknowledge that recurrences may present at a later postoperative time, and we will continue to follow up these patients for longer-term outcomes. Additionally, there may have been selection bias regarding the size of mesh used and thus the ratio of mesh to hernia. For instance, if a surgeon was concerned that they would be randomized to the no TF suture arm, it is conceivable that they would have dissected further laterally to accommodate greater mesh overlap. Surgeons contemplating abandoning TF suture fixation should consider the ratio of mesh to defect, or the amount of mesh overlap of the defect after fascial closure, prior to adopting this practice.

Conclusions

In this RCT, we found that the absence of TF suture fixation was noninferior to TF suture fixation for RVHR with synthetic mesh when fascial closure can be achieved. Transfascial fixation can safely be abandoned in this population.

Trial Protocol

eTable 1. Breakdown of Modalities Used to Assess for Recurrence at the 1-Year Time Point

eFigure. Time to Recurrence Kaplan Meier Plot Between the 2 Groups

eTable 2. 30-Day Recurrence, Reoperation, Readmission Rates, and Wound Outcomes

eTable 3. One-Year Clinical Outcomes

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Pauli EM, Rosen MJ. Open ventral hernia repair with component separation. Surg Clin North Am. 2013;93(5):1111-1133. doi: 10.1016/j.suc.2013.06.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mathes T, Prediger B, Walgenbach M, Siegel R. Mesh fixation techniques in primary ventral or incisional hernia repair. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021;5(5):CD011563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clarke JM. Incisional hernia repair by fascial component separation: results in 128 cases and evolution of technique. Am J Surg. 2010;200(1):2-8. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2009.07.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Krpata DM, Blatnik JA, Novitsky YW, Rosen MJ. Posterior and open anterior components separations: a comparative analysis. Am J Surg. 2012;203(3):318-322. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2011.10.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rangwani SM, Kraft CT, Schneeberger SJ, Khansa I, Janis JE. Strategies for mesh fixation in abdominal wall reconstruction: concepts and techniques. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2021;147(2):484-491. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000007584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Etemad SA, Huang L, Phillips SE, et al. Mechanical vs non-mechanical mesh fixation in open retromuscular ventral hernia repair: a comparative analysis from the Americas Hernia Society Quality Collaborative. J Am Coll Surg. 2018;227(4):S106. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2018.07.218 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berler DJ, Cook T, LeBlanc K, Jacob BP. Next generation mesh fixation technology for hernia repair. Surg Technol Int. 2016;29:109-117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weltz AS, Sibia US, Zahiri HR, Schoeneborn A, Park A, Belyansky I. Operative outcomes after open abdominal wall reconstruction with retromuscular mesh fixation using fibrin glue versus transfascial sutures. Am Surg. 2017;83(9):937-942. doi: 10.1177/000313481708300928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rosen MJ, Krpata DM, Petro CC, et al. Biologic vs synthetic mesh for single-stage repair of contaminated ventral hernias: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Surg. 2022;157(4):293-301. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2021.6902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krpata DM, Schmotzer BJ, Flocke S, et al. Design and initial implementation of HerQLes: a hernia-related quality-of-life survey to assess abdominal wall function. J Am Coll Surg. 2012;215(5):635-642. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2012.06.412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Breivik EK, Björnsson GA, Skovlund E. A comparison of pain rating scales by sampling from clinical trial data. Clin J Pain. 2000;16(1):22-28. doi: 10.1097/00002508-200003000-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DeWalt DA, Rothrock N, Yount S, Stone AA; PROMIS Cooperative Group . Evaluation of item candidates: the PROMIS qualitative item review. Med Care. 2007;45(5)(suppl 1):S12-S21. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000254567.79743.e2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krpata DM, Petro CC, Prabhu AS, et al. Effect of hernia mesh weights on postoperative patient-related and clinical outcomes after open ventral hernia repair: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Surg. 2021;156(12):1085-1092. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2021.4309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stoppa R, Petit J, Henry X. Unsutured Dacron prosthesis in groin hernias. Int Surg. 1975;60(8):411-412. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol

eTable 1. Breakdown of Modalities Used to Assess for Recurrence at the 1-Year Time Point

eFigure. Time to Recurrence Kaplan Meier Plot Between the 2 Groups

eTable 2. 30-Day Recurrence, Reoperation, Readmission Rates, and Wound Outcomes

eTable 3. One-Year Clinical Outcomes

Data Sharing Statement