Abstract

Primary squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck occurs in the skin or squamous epithelial lining tissues of the oral cavity, pharynx, larynx, and sinonasal tract. Although it is a common tumor in horses, distant metastatic spread to the lung is rare. This report describes a case of metastatic pulmonary squamous cell carcinoma in a 23-year-old Morgan gelding. The clinical signs displayed by this gelding in some ways mimicked the typical presentation of equine multinodular pulmonary fibrosis or thoracic lymphoma. The postmortem diagnosis in this case was head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, but a primary site of origin could not be ascertained. Cancer-associated heterotopic ossification (HO) was also identified in this case; this is an exceedingly rare finding with equine pulmonary neoplasia.

Key clinical message:

Careful physical examination should be undertaken in all horses presenting with clinical signs of intrathoracic disease. Clinical and radiographic abnormalities in this case of pulmonary metastatic disease resembled some of those associated with interstitial pneumonia. Rarely encountered in domestic animal species, there has been only 1 previous report of HO in a case of oronasal carcinoma in a horse.

Résumé

Carcinome épidermoïde de la tête et du cou avec ossification hétérotopique, envahissement lymphovasculaire et métastases ganglionnaires et pulmonaires chez un hongre Morgan de 23 ans. Le carcinome épidermoïde primitif de la tête et du cou survient dans la peau ou les tissus épithéliaux squameux de la cavité buccale, du pharynx, du larynx et du tractus naso-sinusien. Bien qu’il s’agisse d’une tumeur courante chez les chevaux, la propagation métastatique à distance au poumon est rare. Ce rapport décrit un cas de carcinome épidermoïde pulmonaire métastatique chez un hongre Morgan de 23 ans. Les signes cliniques présentés par ce hongre imitaient à certains égards la présentation typique de la fibrose pulmonaire multinodulaire équine ou du lymphome thoracique. Le diagnostic post-mortem dans ce cas était un carcinome épidermoïde de la tête et du cou, mais un site d’origine primaire n’a pas pu être déterminé. L’ossification hétérotopique associée au cancer (HO) a également été identifiée dans ce cas; il s’agit d’une découverte extrêmement rare avec la néoplasie pulmonaire équine.

Message clinique clé :

Un examen physique attentif doit être entrepris chez tous les chevaux présentant des signes cliniques de maladie intrathoracique. Les anomalies cliniques et radiographiques dans ce cas de maladie pulmonaire métastatique ressemblaient à certaines de celles associées à la pneumonie interstitielle. Rarement rencontré chez les espèces animales domestiques, il n’y a eu qu’un seul signalement antérieur d’HO dans un cas de carcinome oronasal chez un cheval.

(Traduit par Dr Serge Messier)

Intrathoracic neoplasia is an uncommonly encountered condition in the equine species (1,2). Disseminated (metastatic or secondary) manifestations of cancer represent the most commonly encountered forms of intrathoracic neoplasia in horses, especially lymphosarcoma. Other reported secondary forms of intrathoracic neoplasia include adenocarcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, hemangiosarcoma, lymphangiosarcoma, renal cell carcinoma, myxosarcoma, and melanoma (1–7). The most common primary intrathoracic neoplasm encountered in horses is the pulmonary granular cell tumor with some other cases reported, including pulmonary adenocarcinoma, anaplastic bronchogenic carcinoma, pulmonary carcinoma, pulmonary chondrosarcoma, bronchogenic squamous cell carcinoma, liposarcoma, thyroid carcinoma, primary cardiac hemangiosarcoma, and bronchial myxoma (5,8–10).

The clinical signs associated with thoracic neoplasia are often nonspecific and can be confused with other, more common lower airway diseases in horses (3,11). Careful consideration of historical events, physical examination findings, and advanced diagnostic imaging and testing is often required to confirm neoplasia in horses.

This case outlines the clinical presentation and diagnostic testing used to diagnose an extremely rare pulmonary metastatic squamous cell carcinoma in a horse with the interesting feature of pulmonary heterotopic ossification (HO, or osseous metaplasia). Pulmonary ossification is defined by the presence of mature bone in alveolar or interstitial spaces (12,13). Pulmonary ossification has been reported in human patients with pulmonary infections; interstitial fibrosis; and some renal, gastrointestinal, and soft tissue tumors (12). Pulmonary ossification, however, has been described only extremely rarely in human lung cancer, in which it has been associated with pulmonary adenocarcinoma or squamous cell carcinoma (12–14). To the authors’ knowledge, HO has not been hitherto reported in cases of equine pulmonary neoplasia. The site of origin of the tumor was not determined, but a diagnosis of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma with pulmonary metastasis with ossification, lymphovascular invasion, and nodal metastases was established.

Case description

A 23-year-old Morgan gelding was brought to the University of Missouri Veterinary Health Center (MU-VHC; Columbia, Missouri) for evaluation of a chronic cough of 3 mo duration and weight loss of 1 mo duration. The gelding had a decreased appetite for 4 d prior to presentation. The gelding had been treated with several antimicrobial medications (trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, gentamicin, penicillin, ceftiofur crystalline free acid) and an unspecified oral antihistaminic product for cough, but clinical improvement was not reported. Approximately 3 wk prior to presentation, 2 other horses on the property had developed a green-colored nasal discharge and were coughing; both of these horses improved within 3 d. There were 30 other horses on the farm. This gelding received routine vaccinations (tetanus, eastern equine encephalitis, western equine encephalitis, influenza, and rhinopneumonitis) every other year. The gelding had been living and training in California until 5 y prior to presentation, at which time it had been relocated to Missouri. The gelding’s daily ration consisted of generic pelleted feed (~2.5 kg/d), grass hay (~2.5 kg/d), and free access to grass pasture. The gelding had always been bright and alert despite the recent onset of cough and weight loss.

At admission, the gelding was bright, alert, and responsive, with a reduced body condition score (3/9) (15). Results of vital parameters were within normal limits (rectal temperature: 36.6°C, heart rate: 48 beats/min, and respiratory rate: 16 breaths/min). Mucous membranes were pink and moist with a capillary refill time < 2 s. Cardiac auscultation yielded normal findings, but loud crackles and wheezes were heard throughout the right and left lung fields on both inspiration and expiration. Loud rattling was ausculted in the cranial aspect of the trachea. Borborygmi were normal in character and frequency in all abdominal quadrants. Digital and facial arterial pulses were normal. The maxillary incisors were worn to the gum line. Sharp enamel points and dental attrition affected all dental arcades. There was a firm, round, deep tissue mass measuring ~15 cm × 10 cm at the base of neck on the right side. Another firm, ~6 cm × 4 cm mass was present in the mandibular space, in proximity to the medial aspect of the right mandible. A soft, ~4 cm × 2 cm cutaneous mass slightly rostral to the previously mentioned mass on the mandible was also identified. The throat latch area was diffusely enlarged and firm. Palpation of the throat and the mass lesions did not elicit any signs of pain.

A complete blood (cell) count (CBC) revealed mild, mature neutrophila [8190 cells/μL, reference range (RR): 2400 to 6270 cells/μL] with few reactive lymphocytes observed, and hyperfibrinogenemia (5 g/L, RR: 1 to 4 g/L). Abnormalities identified on plasma biochemistry profile included mild hyperproteinemia (7.7 g/dL, RR: 5.7 to 7.5 g/dL) characterized by mild hypoalbuminemia (2.4 g/dL, RR: 2.5 to 3.6 g/dL) and mild hyperglobulinemia (5.3 g/dL, RR: 2.4 to 4.1 g/dL) with mild total hypocalcemia (11.0 mg/dL, RR: 11.2 to 12.8 mg/dL).

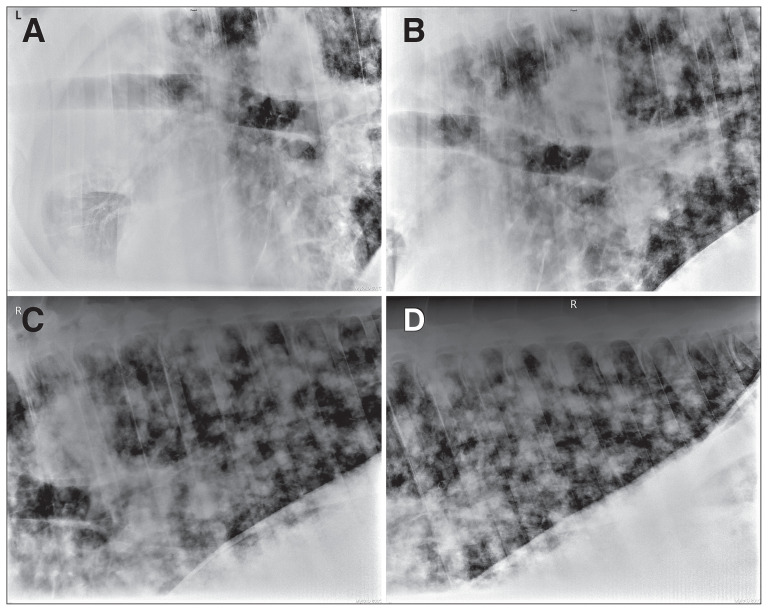

Thoracic ultrasonographic examination revealed multiple nodules visible extensively throughout all lung fields at the surface of both lungs. Consolidation of the left craniodorsal lung field was noted. Ultrasonographic examination of the large mass at the base of the right neck revealed multiple hyperechoic areas surrounded by an ~8 cm × 10 cm soft tissue mass. Due to the mass’ location and appearance, it was suspected to be the right cervical lymph node. The lymph node had an abnormal appearance characterized by lobulation and several regions of marked mixed increased and decreased echogenicity. Abdominal ultrasonography revealed slightly hyperechoic renal cortical parenchyma; the remainder of the abdomen was unremarkable. Thoracic radiography revealed a severe and extensive diffuse nodular pattern (Figure 1 A, B, C, D). The largest nodule was present at the perihilar region and had irregular margins (Figure 1 A, B, C). Tracheobronchial lymphadenopathy was evidenced by radiographically identified dorsal deviation of the trachea (Figure 1 A, B, C). Abnormalities were not detected by an endoscopic examination of the upper respiratory tract (to the level of the bronchial bifurcation). Under ultrasound guidance, a fine needle aspirate of an enlarged cervical lymph node was retrieved. Results were consistent with reactive lymphoid hyperplasia; neoplastic cells were not detected.

Figure 1.

Thoracic radiography in a 23-year-old horse. A to D — There is a severe, diffuse nodular pattern present within the lungs. The nodules have irregular margins and are variable in size. B and C — Large nodules are visible in perihilar region. Deviation of the terminal trachea suggests enlarged tracheobronchial lymph nodes.

Due to the poor prognosis and the owner’s preference, the gelding was euthanized. The gelding was sedated with xylazine (XylaMed; VetOne, Boise, Idaho, USA), 0.625 mg/kg BW, IV, once; and then pentobarbital (Fatal-Plus; Vortech, Dearborn, Michigan, USA), 100 mg/kg BW, IV, was administered.

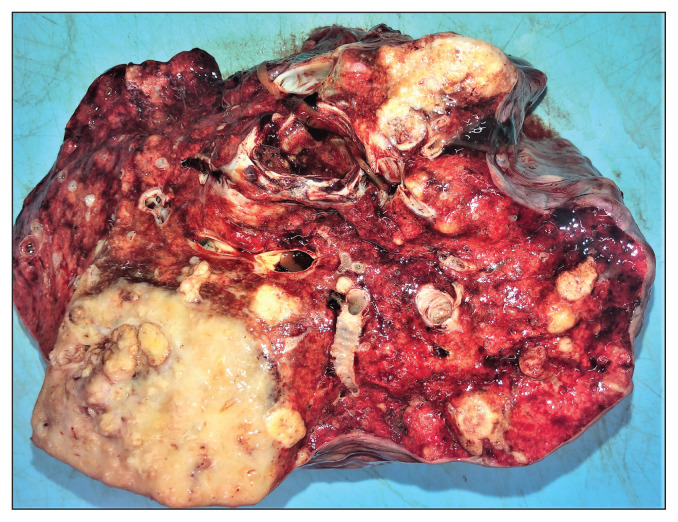

Pathological examination confirmed that the clinically noted subcutaneous nodular mass at the base of neck was an abnormal lymph node. The subcutaneous mass in the mandibular space was associated with the ventral aspect of the caudal part of the left mandible. These masses were tan and solid with multifocal areas of mineralization on the cut surface. The submandibular and prescapular lymph nodes were enlarged, up to 8 × 4 × 4 cm and up to 6 × 4 × 3 cm in size, respectively; and had tan, coalescing nodular foci with multifocal areas of mineralization on the cut surface. The surface of the right longus colli muscle at the dorsolateral aspect of the right side of the esophagus had been extensively replaced by a firm, tan, coalescing nodular mass. There was a similar firm, tan, 15 × 11 × 5 cm, coalescing nodular mass with multifocal areas of mineralization on the cut surface at the thoracic inlet. The lungs had numerous, multifocal to coalescing firm and tan nodular masses; 1 of these in the caudal aspect of the left lung lobe was the largest (20 × 13 × 13 cm) (Figure 2). The oral cavity and trachea were grossly unremarkable. Examination of the paranasal sinuses and brain did not reveal any abnormalities.

Figure 2.

Pathology. Multiple firm, tan, nodular masses are present in the lung of a 23-year-old horse.

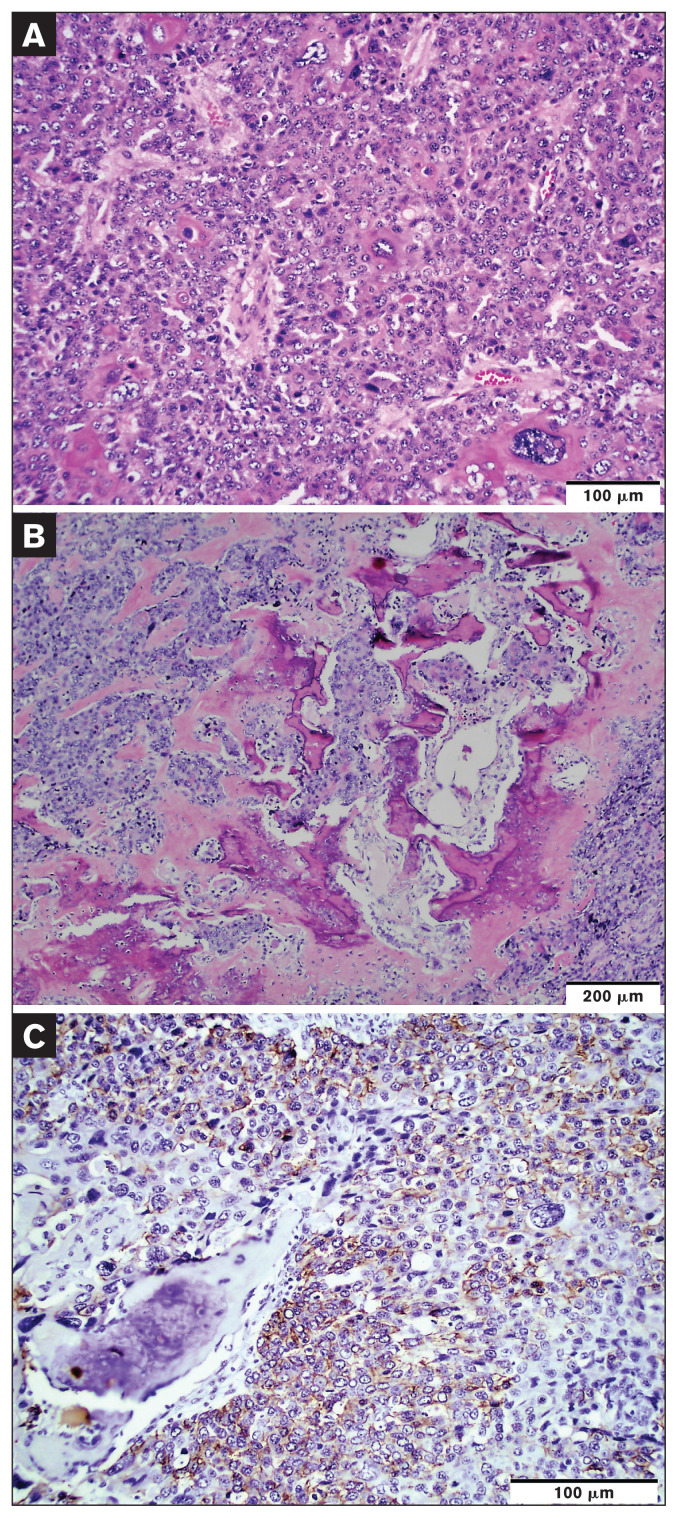

Histological characteristics of the grossly noted masses and enlarged lymph nodes were very similar. Neoplastic masses were composed of nests, islands, and trabeculae of polygonal cells with desmoplasia. Neoplastic cells had variably distinct cell borders; moderate to large amounts of pale eosinophilic fibrillar cytoplasm; and oval to polygonal nuclei with vesicular to coarsely stippled chromatin, with up to 4 small to large, variably distinct nucleoli. There was marked anisocytosis and anisokaryosis with rare multinucleated neoplastic cells and neoplastic cells with karyomegaly (Figure 3 A). It was estimated that there were 20 mitoses per 10 high-power fields. Aggregates of neoplastic cells were noted in multiple lymphovascular spaces. There were frequent random, irregular foci of homogeneous pale, eosinophilic bone matrix and woven bone trabeculae interspersed throughout the neoplasm (Figure 3 B). Neoplastic cells exhibited squamous differentiation and individual cell keratinization in some areas (Figure 3 A). Neoplastic cells stained positive for pan-cytokeratin (cytokeratin MNF116; Dako, M0821, dilution 1:1000) (Figure 3 C) and cytokeratin 5/6 (Dako, M7237, dilution 1:100) whereas they stained negative for vimentin (Dako, M7020, dilution 1:200), cytokeratin 8/18 (Leica, NCL-L-5D3, dilution 1:100), chromogranin A (Bio SB, BSB5347, dilution 1:100), and thyroid transcription factor-1 (Dako, M3575, 1:2000), all by immunohistochemistry (Figure 3). Histology and immunohistochemistry findings were consistent with squamous cell carcinoma, HO, and nodal and pulmonary metastasis.

Figure 3.

Histology and immunohistochemistry. A — The neoplasm is composed of sheets of polygonal cells. There are marked anisocytosis, anisokaryosis, and some neoplastic cells with karyomegaly. Some neoplastic cells exhibit individual cell keratinization. Hematoxylin and eosin stain; scale bar = 100 μm. B — There are foci of bone matrix (osteoid) and irregular immature trabecular bone formation among the tumor area. Hematoxylin and eosin stain; scale bar = 200 μm. C — Neoplastic cells are stained positive for pan-cytokeratin by immunohistochemistry. MACH2 horseradish peroxidase system with Romulin AEC chromogen kit; scale bar = 100 μm.

Discussion

Most head and neck carcinomas are derived from the mucosal epithelium of the oral cavity, pharynx, larynx, or sinonasal tract, and are referred to collectively as “head and neck squamous cell carcinoma” in human medicine (16). In this case, head and neck involvement was confirmed by both gross and histological examinations. However, no gross lesion was observed in the oral cavity, pharynx, larynx, or sinonasal tract; and hence, the primary tumor site could not be determined. In humans, over 50% of primary tumors remain undiscovered in patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma of unknown primary origin despite extensive diagnostic workups that include endoscopy, computed tomography, and magnetic resonance imaging (16).

This case represents an uncommon neoplasm in an adult horse. Although localized squamous cell carcinoma at mucocutaneous interfaces is common in horses (17), its manifestation as head and neck carcinoma with distant metastasis is rare. Due to the deteriorating clinical course of disease and concerns regarding quality of life, this gelding was euthanized. The clinical picture was very similar to that of equine multinodular pulmonary fibrosis, thoracic lymphoma, or metastatic disease of another origin. Clinical signs of thoracic neoplasia are nonspecific and are similar to clinical signs seen with other inflammatory or infectious conditions, including lethargy, exercise intolerance, weight loss, cough, tachycardia, tachypnea, fever, and nasal discharge (2,5,11,18). Because clinical signs of thoracic or pulmonary disease may be nonspecific, it is important to include neoplasia in a listing of differential diagnoses despite its rarity in horses.

There is increasing evidence that manifestations of both periocular and genital squamous cell carcinoma in horses may be induced by Equus caballus Papillomavirus-2 (EcPV-2) infection (19). Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma in humans also often results from papillomavirus infection (hr-HPV) due to high-risk human interactions (20). Indeed, observation that numerous similarities (immunophenotypic, molecular, cytological, and histopathological) exist between human squamous cell carcinoma associated with hr-HPV and squamous cell carcinoma in horses has led to the proposition that the equine disease may represent a spontaneous model for its human counterpart (21). Whereas the phenomenon of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) is important during normal embryogenesis, inappropriate re-activation of EMT is pivotal for acquisition of an invasive malignant phenotype by primary epithelial cells during malignant transformation (22). Various papilloma viral genes have been shown to induce EMT in some forms of both human and equine squamous cell carcinoma (23,24). It remains possible that EcPV-2-derived oncogenes provoked squamous cell carcinoma through activated EMT in our case. However, proof of a relationship between squamous cell carcinoma in this case and activated EMT would have required demonstration of EcPV-2 presence (via PCR) with upregulated mesenchymal (N-cadherin and vimentin) and downregulated epithelial (E-cadherin, beta-catenin, and cytokeratin) markers (20). Unfortunately, PCR testing to demonstrate presence of EcPV-2 via PCR was unavailable in North America at the time this case was presented.

Care must be taken to differentiate cancer from other more common respiratory diseases, as thoracic neoplasia carries a grave prognosis in horses (5). When examining horses with lung disease, it is important to emphasize that many of the routinely used, noninvasive diagnostic tests do not reliably differentiate neoplasia from inflammatory or infectious etiologies (3,11). Chronic inflammatory pulmonary conditions (such as equine multinodular pulmonary fibrosis), metastatic disease, or fungal pneumonia should each be ruled out in cases presenting with a multinodular pattern on thoracic ultrasonography and radiography. A complete evaluation of the pulmonary system is warranted, including minimum database measurements of CBC, serum biochemistry, urinalysis, endoscopy of the upper and lower airways, ultrasonographic and radiographic imaging of the chest, and airway fluid cytology (where appropriate). Pleural fluid was helpful for identification of tumor cells in 12/14 horses diagnosed antemortem with thoracic neoplasia, and peripheral lymph node biopsy was confirmatory in the other 2/14 (2). Cancer diagnosis was not established in this case based on fine-needle aspiration of an enlarged lymph node. It is possible that a surgical biopsy of an enlarged lymph node or a pulmonary biopsy might have yielded a more diagnostic result, but these tests were not pursued in this case due to the gelding’s deteriorating health and the owner’s request for euthanasia (25).

Careful postmortem examination should also be carried out in similar cases, to differentiate types of neoplasia. For this case, extensive immunohistochemical staining was performed. Results indicated that neoplastic disease in this case was squamous cell carcinoma with metastasis involving regional lymph nodes and the lungs. Interestingly, HO (also known as osseous metaplasia or ectopic bone formation in soft tissues) was also identified on histopathological examination of the metastatic pulmonary carcinoma lesions. Heterotopic ossification is defined as the formation of mature lamellar bone in soft tissue sites outside the skeleton, which is an uncommonly encountered pathological process (26). From the human medical perspective, HO has most commonly been identified as a complication of trauma (including surgical trauma and burn injuries) and regarded as a tissue repair process gone awry, but it is also occasionally identified in some rarely encountered genetic diseases (fibrodysplasia ossificans and progressive osseous heteroplasia) and cancer. Cancer-associated HO has been uncommonly reported in some types of carcinoma and adenocarcinoma in human patients (12,13,27). To the authors’ knowledge, it has only been reported in horses in the context of intramuscular HO (traumatic myositis ossificans), in a case of lameness in a horse (28) and in 1 horse with an ossifying oronasal carcinoma (29).

Whereas a complete understanding of the pathogenesis of HO in the context of pulmonary neoplasia is still lacking, it has been proposed to result from osteogenic metaplasia of undifferentiated stromal mesenchymal cells into osteoprogenitor cells, provoked by diverse bone morphogenetic protein (BMP)-secreting tumor cells (30). Upregulated expression of osteoinductive factors (BMP-9, osteocalcin, and osteopontin) by tumor cells has been proposed to cause osteoblast-like transformation in some instances (27).

In their case of colon cancer with HO, Noh et al demonstrated “osteoblast-like transformation” of tumor cells using immunohistochemistry for osteoblast-phenotypical markers (BMP-9, osteocalcin, and osteopontin) (27). Moreover, BMP-9, osteocalcin, and osteopontin overexpression was evident in mesenchymal stromal cells in the surrounding tissues. The authors concluded that the release of these osteoinductive molecules caused osteoblastic differentiation in proximate (uncommitted) mesenchymal stromal cells and led to HO. Although unavailable to our group at this time, future studies of HO associated with equine neoplasia should include immunohistochemical characterization of the expression of these bone-stimulating substances.

In conclusion, this report is the first to describe the case presentation and postmortem findings for a horse with squamous cell carcinoma with HO and pulmonary metastasis. CVJ

Footnotes

Use of this article is limited to a single copy for personal study. Anyone interested in obtaining reprints should contact the CVMA office (hbroughton@cvma-acmv.org) for additional copies or permission to use this material elsewhere.

References

- 1.Sweeney CR, Gillette DM. Thoracic neoplasia in equids: 35 cases (1967–1987) J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1989;195:374–377. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mair TS, Brown PJ. Clinical and pathological features of thoracic neoplasia in the horse. Equine Vet J. 1993;25:220–223. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-3306.1993.tb02947.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davis EG, Rush BR. Diagnostic challenges: Equine thoracic neoplasia. Equine Vet Educ. 2013;25:96–107. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meyer J, Delay J, Bienzle D. Clinical, laboratory, and histopathologic features of equine lymphoma. Vet Pathol. 2006;43:914–924. doi: 10.1354/vp.43-6-914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scarratt WK, Crisman MV. Neoplasia of the respiratory tract. Vet Clin North Am Equine Pract. 1998;14:451–473. doi: 10.1016/s0749-0739(17)30180-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gerding JC, Gilger BC, Montgomery SA, Clode AB. Presumed primary ocular lymphangiosarcoma with metastasis in a miniature horse. Vet Ophthalmol. 2015;18:502–509. doi: 10.1111/vop.12249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Samuelson JP, Echeverria KO, Foreman JH, Fredrickson RL, Sauberli D, Whiteley HE. Metastatic myxosarcoma in a quarter horse gelding. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2018;30:121–125. doi: 10.1177/1040638717719480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kondo H, Wickins SC, Conway JA, et al. Cranial mediastinal liposarcoma in a horse. Vet Pathol. 2012;49:1040–1042. doi: 10.1177/0300985811432348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Manso-Díaz G, Jiménez Martínez M, García-Fernández RA, Herrán R, Santiago I. Mediastinal ectopic thyroid carcinoma and concurrent multinodular pulmonary fibrosis in a horse. J Equine Vet Sci. 2019;77:8–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jevs.2019.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beaumier A, Dixon CE, Robinson N, Rush JE, Bedenice D. Primary cardiac hemangiosarcoma in a horse: Echocardiographic and necropsy findings. J Vet Cardiol. 2020;32:66–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jvc.2020.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wilkins PA. Lower airway diseases of the adult horse. Vet Clin North Am Equine Pract. 2003;19:101–121. doi: 10.1016/s0749-0739(02)00069-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Khudayar H, Tahir O, Manzoor K. Squamous cell carcinoma of the lung with heterotopic ossification. Chest. 2016;150:757A. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang Q, Yin L, Li B, et al. Pulmonary adenocarcinoma with osseous metaplasia: A rare occurrence possibly associated with early stage? Onco Targets Ther. 2013;6:1631–1634. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S48195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim GY, Kim J, Kim TS, Han J. Pulmonary adenocarcinoma with heterotopic ossification. J Korean Med Sci. 2009;24:504–510. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2009.24.3.504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Henneke DR, Potter GD, Kreider JL, Yeates BF. Relationship between condition score, physical measurements and body fat percentage in mares. Equine Vet J. 1983;15:371–372. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-3306.1983.tb01826.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fu TS, Foreman A, Goldstein DP, de Almeida JR. The role of transoral robotic surgery, transoral laser microsurgery, and lingual tonsillectomy in the identification of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma of unknown primary origin: A systematic review. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2016;45:28. doi: 10.1186/s40463-016-0142-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Taylor S, Haldorson G. A review of equine mucocutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Equine Vet Educ. 2013;25:374–378. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marr CM. Cardiac and respiratory disease in aged horses. Vet Clin North Am Equine Pract. 2016;32:283–300. doi: 10.1016/j.cveq.2016.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Scase T, Brandt S, Kainzbauer C, et al. Equus caballus papillomavirus-2 (EcPV-2): An infectious cause for equine genital cancer? Equine Vet J. 2010;42:738–745. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-3306.2010.00311.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Armando F, Mecocci S, Orlandi V, et al. Investigation of the epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT) process in equine papillomavirus-2 (EcPV-2)-positive penile squamous cell carcinomas. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:10588. doi: 10.3390/ijms221910588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Suárez-Bonnet A, Willis C, Pittaway R, Smith K, Mair T, Priestnall SL. Molecular carcinogenesis in equine penile cancer: A potential animal model for human penile cancer. Urol Oncol. 2018;36:532e9–e18. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2018.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lamouille S, Xu J, Derynck R. Molecular mechanisms of epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2014;15:178–196. doi: 10.1038/nrm3758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jung YS, Kato I, Kim HR. A novel function of HPV16-E6/E7 in epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2013;435:339–344. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.04.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Armando F, Godizzi F, Razzuoli E, et al. Epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT) in a laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma of a horse: Future perspectives. Animals. 2020;10:2318. doi: 10.3390/ani10122318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Raphel CF, Gunson DE. Percutaneous lung biopsy in the horse. Cornell Vet. 1981;71:439–448. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meyers C, Lisiecki J, Miller S, et al. Heterotopic ossification: A comprehensive review. JBMR Plus. 2019;3:e10172. doi: 10.1002/jbm4.10172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Noh BJ, Kim YW, Park YK. A rare colon cancer with ossification: Pathogenetic analysis of bone formation. Ann Clin Lab Sci. 2016;46:428–432. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dyson S. Intermuscular heterotopic ossification in the shoulder region sssociated with a hopping-type forelimb lameness. J Equine Vet Sci. 2014;34:532–537. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Silva A, Cassou F, Andrade B, et al. Ossifying oronasal carcinoma in a horse. Braz J Vet Pathol. 2012;5:128–132. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Imai N, Iwai A, Hatakeyama S, et al. Expression of bone morphogenetic proteins in colon carcinoma with heterotopic ossification. Pathol Int. 2001;51:643–648. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1827.2001.01243.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]