Abstract

Background

Pinus is the largest genus of Pinaceae and the most primitive group of modern genera. Pines have become the focus of many molecular evolution studies because of their wide use and ecological significance. However, due to the lack of complete chloroplast genome data, the evolutionary relationship and classification of pines are still controversial. With the development of new generation sequencing technology, sequence data of pines are becoming abundant. Here, we systematically analyzed and summarized the chloroplast genomes of 33 published pine species.

Results

Generally, pines chloroplast genome structure showed strong conservation and high similarity. The chloroplast genome length ranged from 114,082 to 121,530 bp with similar positions and arrangements of all genes, while the GC content ranged from 38.45 to 39.00%. Reverse repeats showed a shrinking evolutionary trend, with IRa/IRb length ranging from 267 to 495 bp. A total of 3,205 microsatellite sequences and 5,436 repeats were detected in the studied species chloroplasts. Additionally, two hypervariable regions were assessed, providing potential molecular markers for future phylogenetic studies and population genetics. Through the phylogenetic analysis of complete chloroplast genomes, we offered novel opinions on the genus traditional evolutionary theory and classification.

Conclusion

We compared and analyzed the chloroplast genomes of 33 pine species, verified the traditional evolutionary theory and classification, and reclassified some controversial species classification. This study is helpful in analyzing the evolution, genetic structure, and the development of chloroplast DNA markers in Pinus.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12864-023-09439-6.

Keywords: Pinus, Complete chloroplast genome, Comparative analysis, Phylogenetic relationships

Introduction

Pinus (Pinaceae) is the largest conifer genus among existing gymnosperms with more than 110 identified species. The genus natural distribution is mainly in the northern hemisphere, but it has been introduced and cultivated as a planation species all over the world [1]. As the most primitive group in modern genera of Pinaceae, Pinus has a long evolutionary history. Its fossil records can be traced back to 100 MYA [1–3], with a great potential for studying conifers evolutionary classification and species differentiation [3–6]. Pines are the main component of northern temperate forest and arid forest land, and are also important source of afforestation and industrial processing raw materials as well as their important ecological and economic values [7].

Pinus classification has always been a hot topic in phylogeny. Little et al. [8] proposed a classification system that divides Pinus into 3 Subgenera, 5 Sections, 15 Subsections and 94 species, and determined their basic classification framework. With scientific and technological advancements, Pinus classification system has gone through several revisions and improvements [1, 6, 9, 10]. Notably, Gernandt et al. [9] divided Pinus into 2 Subgenera (Subgenus: Strobus and Pinus), 4 Sections (Sections: Trifoliae, Pinus, Parrya, and Quinquefoliae) and 11 Subsections (Subsections: Pinus, Pinaster, Contortae, Australes, Ponderosae, Balfourianae, Cembroides, Nelsoniae, Kremfianae, Gerardianae, and Strobus) based on chloroplast gene sequence, nuclear DNA, and morphological evidence of 101 species. This classification system has been widely recognized [5, 11, 12]. However, the classification of individual species at the Subsection level has been controversial. Since Pinus squamata discovery, its classification efforts have been a hot issue. Li Xiangwang [13] discovered P. squamata and thought that it is close to P. bungeana. Price [14] pointed out that P. squamata may be a component of Subsection Gerardianae, or it may represent a separate Subsection. Li Xiangping et al. [15] incorporated P. squamata into Subsection Balfourianae. With wood anatomical data, Wang Changming et al. [16] supported the view that P. squamata is close to P. bungeana. In Gernandt et al. [9] traditional classification, P. squamata is also classified into the Subsection Gerardianae where P. bungeana and P. gerardiana are located. Although it is more likely that P. squamata belongs to Subsection Gerardianae, previous studies only relied on morphology and limited DNA data.

The chloroplast genome structure of terrestrial plants is stable [17] and has a large amount of genetic information, which can be used for phylogenetic inference and species classification [18]. In previous studies, chloroplast sequences have been extensively utilized as molecular markers in plant phylogeny research. However, due to the lack of complete chloroplast genome sequence data, many studies on chloroplast genome were limited to only few fragments, so the application of complete chloroplast genome sequence to phylogeny has not been widely applied [19–26]. The complete chloroplast genome sequence is much better than some fewer fragments in species phylogeny and classification determination [27–29]. With the development of new generation sequencing technology, phylogenetic analyses have ushered in a new era [30] and made it easier to obtain complete chloroplast genome sequences for many species. A large number of sequence data provide basic data for chloroplast genome structure study, gene composition, and also lay a foundation for plants phylogeny, classification, and species identification.

In this study, the complete chloroplast genomes of 33 published species of Pinus were characterized, and used to conduct genome comparative and phylogenetic analyses. We aimed to: (1) explore the size and structure differences of complete chloroplast genomes among the studied species; (2) identify highly variable regions in the studied chloroplast genomes; and (3) reconstruct pines phylogenetic relationship, and verify and supplement the traditional classification system.

Results

Characteristics of Pinus chloroplast (cp.) genomes

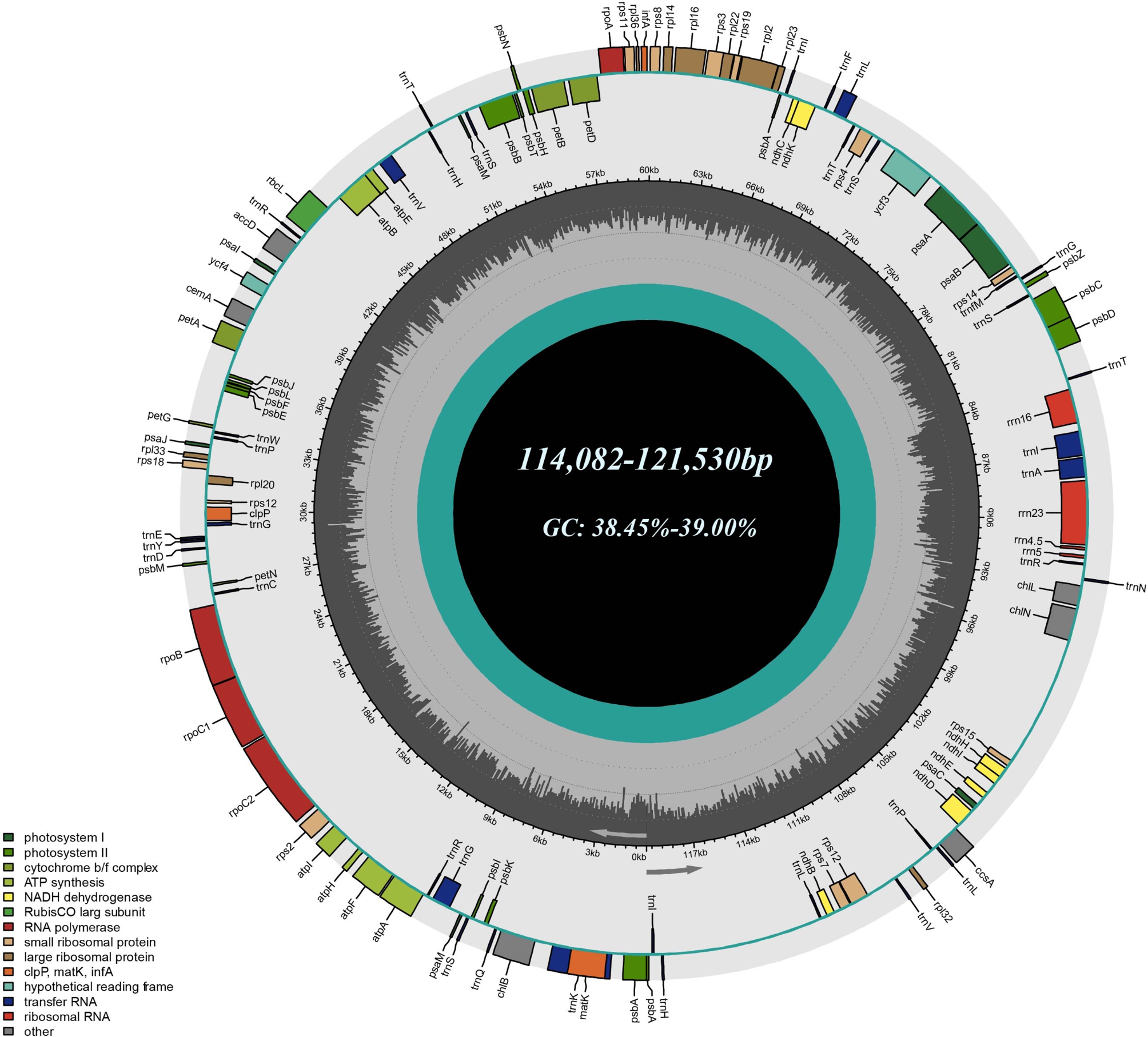

The cp. genomes of the 33 published pine species presented typical chloroplast genome structure, which consisted of a pair of inverted repeats (IRa/b) that divided into two single-copy regions: large single-copy (LSC) and small single-copy (SSC) regions (Fig. 1). Chloroplast genomes sequence similarity among 33 species was more than 95%. There was no significant difference in the size, gene, and genome structure among the studied chloroplast genomes. The genomes’ quadripartite structure was not obvious, which was mainly manifested by the reduction of the IR regions. The chloroplast genome length ranged from 114,082 to 121,530 bp, LSC region of which ranged from 62,747 to 66,364 bp, SSC region ranged from 49,112 to 54,288 bp, and IR regions ranged from 267 to 495 bp. The species with the largest chloroplast genome length was P. taeda, and the smallest was P. pinceana. The chloroplast genome size of Pinus was lower than that of most other seed plants, which may be related to the reduction of IR regions during evolution. Total GC content was 38.45-39.00%, with no significant difference among the 33 species (Table 1). The GC content of the genome was an important indicator to judge the genetic relationship between species, which further showed that the chloroplast genomes of the 33 pine species were highly similar.

Fig. 1.

Gene cycle maps of 33 Pinus species. Color bars represent different functional groups. The dark and light gray columns in the inner circle correspond to the GC and AT contents, respectively

Table 1.

Summary of Pinus chloroplast genome features

| Species | Accession number | Genome size(bp) | GC% AT% | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LSC | SSC | IRA | IRB | Total | ||||

| Pinus aristata | NC_039809.1 | 65,192 | 52,606 | 312 | 312 | 118,422 | 38.62 | 61.38 |

| Pinus armandii | NC_029847.1 | 64,548 | 51,767 | 475 | 475 | 117,265 | 38.79 | 61.21 |

| Pinus bungeana | NC_028421.1 | 65,373 | 51,538 | 475 | 475 | 117,861 | 38.83 | 61.17 |

| Pinus contorta | MH612863.1 | 65,836 | 54,131 | 267 | 267 | 120,501 | 39.00 | 61.00 |

| Pinus crassicorticea | NC_041150.1 | 65,737 | 53,216 | 388 | 388 | 119,729 | 38.55 | 61.45 |

| Pinus densiflora | NC_042394.1 | 65,654 | 53,231 | 495 | 495 | 119,875 | 38.49 | 61.51 |

| Pinus elliottii | NC_042788.1 | 65,600 | 53,308 | 484 | 484 | 119,876 | 38.46 | 61.54 |

| Pinus gerardiana | NC_011154.4 | 65,131 | 51,771 | 358 | 358 | 117,618 | 38.90 | 61.10 |

| Pinus greggii | NC_035947.1 | 65,536 | 53,995 | 485 | 485 | 120,501 | 38.45 | 61.55 |

| Pinus jaliscana | NC_035948.1 | 65,553 | 54,192 | 485 | 485 | 120,715 | 38.46 | 61.54 |

| Pinus koraiensis | NC_004677.2 | 64,523 | 51,717 | 475 | 475 | 117,190 | 38.80 | 61.20 |

| Pinus krempfii | NC_011155.4 | 65,036 | 51,257 | 348 | 348 | 116,989 | 38.91 | 61.09 |

| Pinus lambertiana | NC_011156.4 | 64,578 | 51,715 | 473 | 473 | 117,239 | 38.79 | 61.21 |

| Pinus massoniana | NC_021439.1 | 65,557 | 53,212 | 485 | 485 | 119,739 | 38.55 | 61.45 |

| Pinus monophylla | NC_011158.4 | 64,752 | 50,811 | 458 | 458 | 116,479 | 38.73 | 61.27 |

| Pinus morrisonicola | NC_039616.1 | 64,104 | 51,770 | 381 | 381 | 116,636 | 38.75 | 61.25 |

| Pinus nelsonii | NC_011159.4 | 64,935 | 50,991 | 454 | 454 | 116,834 | 38.89 | 61.11 |

| Pinus oocarpa | NC_035949.1 | 65,485 | 54,141 | 485 | 485 | 120,596 | 38.47 | 61.53 |

| Pinus parviflora | NC_039615.1 | 66,364 | 53,410 | 475 | 475 | 120,724 | 38.58 | 61.42 |

| Pinus pinceana | NC_039587.1 | 64,346 | 49,112 | 312 | 312 | 114,082 | 38.81 | 61.19 |

| Pinus pinea | NC_039585.1 | 65,357 | 53,634 | 490 | 490 | 119,971 | 38.45 | 61.55 |

| Pinus pumila | NC_041108.1 | 64,606 | 51,844 | 475 | 475 | 117,400 | 38.80 | 61.20 |

| Pinus sibirica | NC_028552.2 | 63,908 | 51,781 | 473 | 473 | 116,635 | 38.72 | 61.28 |

| Pinus squamata | NC_039614.1 | 64,706 | 51,825 | 398 | 398 | 117,327 | 38.73 | 61.27 |

| Pinus strobus | NC_026302.1 | 62,747 | 51,885 | 472 | 472 | 115,576 | 38.77 | 61.23 |

| Pinus sylvestris | NC_035069.1 | 65,559 | 53,209 | 495 | 495 | 119,758 | 38.50 | 61.50 |

| Pinus tabuliformis | NC_028531.1 | 65,618 | 53,038 | 495 | 495 | 119,646 | 38.53 | 61.47 |

| Pinus taeda | NC_021440.1 | 66,272 | 54,288 | 485 | 485 | 121,530 | 38.50 | 61.50 |

| Pinus taiwanensis | NC_027415.1 | 65,670 | 53,081 | 495 | 495 | 119,741 | 38.51 | 61.49 |

| Pinus teocote | NC_039586.1 | 65,516 | 53,910 | 485 | 485 | 120,396 | 38.46 | 61.54 |

| Pinus thunbergii | NC_001631.1 | 65,696 | 53,021 | 495 | 495 | 119,707 | 38.50 | 61.50 |

| Pinus wangii | NC_039613.1 | 65,600 | 51,521 | 476 | 476 | 118,073 | 38.70 | 61.30 |

| Pinus yunnanensis | NC_043856.1 | 65,619 | 53,098 | 495 | 495 | 119,707 | 38.52 | 61.48 |

All chloroplast genomes contained a total of 108 genes, including 72 protein-coding (PCGs), 32 tRNA, and four rRNA genes. Only the trnI-GAU gene and part of psbA gene were distributed in the IR region. All genes had the same location and arrangement across the different chloroplast genomes (Table 2). Among the above annotated genes, 14 genes contained introns, including 8 PCGs (atpF, petB, petD, rpl2, rps12, rpl16, rpoC1, and ycf3) and 6 tRNA (trnV-UAC, trnL-UAA, trnK-UUU, trnI-GAU, trnG-UCC and trnA-UGC) genes. Among them, rps12 and ycf3 contained two introns, the remaining 12 contained one intron; matK was located on the intron of trnK-UUU; trnH-GUG, trnI-CAU, trnS-GCU, trnT-GGU, psbA and psaM had two gene copies in the genome. In addition, as in angiosperms, rps12 was also trans-spliced during transcription in Pinus.

Table 2.

List of genes annotated in the chloroplast genome of Pinus species

| Function | Genes |

|---|---|

| Ribosomal RNAs | rrn4.5, rrn5, rrn16, rrn23 |

| Transfer RNAs | trnA-UGC*, trnC-GCA, trnD-GUC, trnE-UUC, trnF-GAA, trnG-GCC, trnG-UCC*, trnH-GUG, trnI-CAU, trnI-GAU*, trnK-UUU*, trnL-CAA, trnL-UAA*, trnL-UAG, trnM-CAU, trnfM-CAU, trnN-GUU, trnP-UGG, trnP-GGG, trnQ-UUG, trnR-ACG, trnR-CCG, trnR-UCU, trnS-GCU, trnS-GGA, trnS-UGA, trnT-GGU, trnT-UGU, trnV-GAC, trnV-UAC*, trnW-CCA, trnY-GUA |

| RNA polymerase | rpoA, rpoB, rpoC1*, rpoC2 |

| Maturase | matK |

| Ribosomal proteins (SSU) | rps2, rps3, rps4, rps7, rps8, rps11, rps12**, T, rps14, rps15, rps18, rps19 |

| Ribosomal proteins (LSU) | rpl2*, rpl14, rpl16*, rpl20, rpl22, rpl23, rpl32, rpl33, rpl36 |

| ATP synthase | atpA, atpB, atpE, atpF*, atpH, atpI |

| Photosystem I | psaA, psaB, psaJ, psaM, psaC, psaI |

| Photosystem II | psbI, psbJ, psbH, psbT, psbN, psbM, psbK, psbD, psbA, psbL, psbC, psbE, psbF, psbB, psbZ |

| RubisCO large subunit | rbcL |

| Cytochrome b/f complex | petL, petA, petB*, petG, petN, petD* |

| Chlorophyll biosynthesis | chlB, chlL, chlN |

| Protease | clpP |

| Acetyl-CoA carboxylase | accD |

| Inner membrane protein | cemA |

| Cytochrome c biogenesis | ccsA |

| Translation initiation factor | infA |

| Hypothetical chloroplast reading frames(ycf) | ycf1, ycf2, ycf3**, ycf4, ycf12 |

*Genes containing one intron; ** genes containing two introns; T trans-splicing of the related gene. Genes in boldface type have two gene copies

The number and sequence of rRNA genes were the same as those of “typical” seed plant plastids such as Nicotiana, and they were all arranged in the order of 16 S, 23 S, 4.5 and 5 S rRNA [31]. However, there were some differences in the content of other genes between Pinus and angiosperms. Angiosperms lost trnP-GGG and three chl genes (chlB, chlL, chlN) during evolution [32]. The gene rpl23 deletion had been reported in the plastids of angiosperms Spinacia [33, 34] and Trachelium [32]. The gene rps16 had experienced many independent losses in land plants [32, 35, 36]. Similarly, the chloroplasts of Pinus also lacked rps16. In addition, unlike Pinus, in many prokaryote and eukaryote lineages, the gene accD had been lost independently [37].

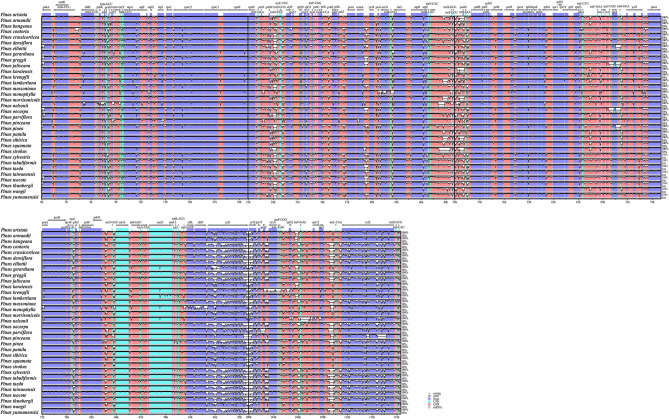

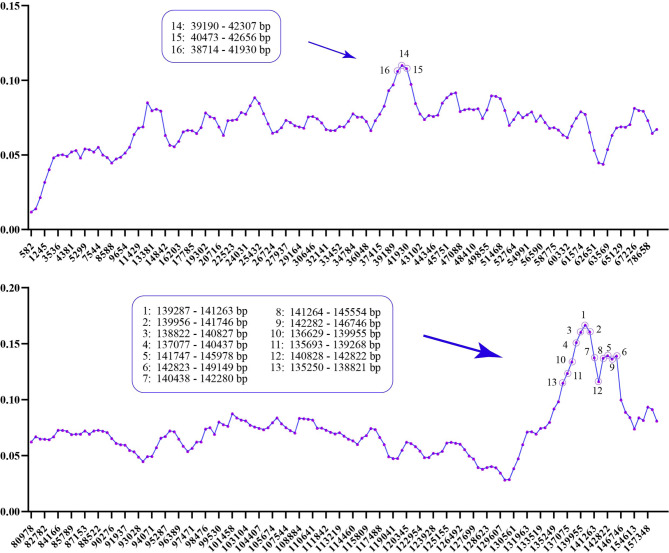

Highly variable regions in the Pinus chloroplast genomes

The comparative visualization of the complete chloroplast genomes of the 33 species clearly showed sequences differences. As a whole, all genomes were relatively conservative and the variation of most coding genes and all rRNAs was relatively small. The regions with obvious gap were mostly concentrated in non-coding regions, among which psbM-trnD, cemA-ycf4, trnV-trnH, trnT-psbM, trnT-rps4-trnS, psbD-trnT-rrn16, psaC-ccsA, rpl32-trnV and rps7-trnL were the most significant; and in the coding regions, atpE, ycf1 and ycf2 were the most significant (Fig. 2). In order to further analyze the differences in the studied 33 Pinus chloroplast genomes, we identified highly variable regions by calculating the nucleotide diversity (Pi). Two highly variable regions psbM-trnD-trnY-trnE-clpP-rps12 and chlN-ycf1 were obtained by screening the 16 regions with the highest Pi value (0.10616–0.16672) (Fig. 3; Table S1). Chloroplast genome rearrangement analysis results showed that rearrangement events of genome were not obvious (Fig. S1).

Fig. 2.

Visualization of genome alignment of the complete chloroplast genome of 33 Pinus. The cp. genome of P. armandii was used as reference. X-axis indicates the sequence coordinates in the whole cp. genome. Y-axis represents the similarity of the aligned regions, indicating percent identity to the reference genome (50–100%)

Fig. 3.

Sliding-window analysis showing the nucleotide diversity (Pi) values of the aligned Pinus chloroplast genomes. The dimension areas are the 16 areas with the highest Pi value

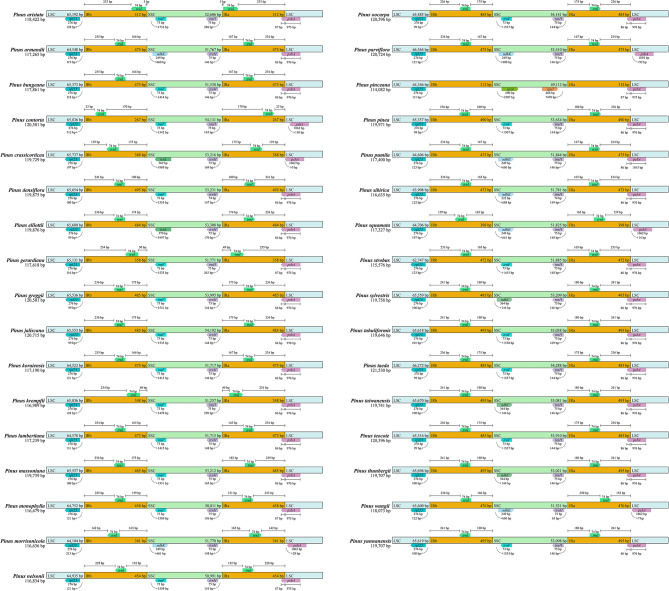

The chloroplast genomes of Pinus have a contracted IR region

The single copy and inverted repeat boundary maps of the 33 species showed that, similar to most terrestrial plants, the cpDNA genome could be divided into four parts, including LSC, SSC, and two IR regions that separated them. However, the difference was that the IR regions of Pinus was not complete as they lost a large number of reverse repeat copies during their evolution. The IR regions had shrunk significantly, with a size of only 267–495 bp. Only trnI gene and part of psbA gene were retained in IRa region, and only trnI was retained in IRb region. The size range of LSC was 62,747 − 66,364 bp, and the size range of SSC was 49,112 − 54,288 bp, yet the size difference between the two regions was not obvious. With the exception of 6 species (P. contorta, P. crassicorticea, P. morrisonicola, P. parviflora, P. squamata, P. wangii), the IRa/LSC junction in the chloroplast genomes of the other 28 species was located in psbA, and the range extending to the IRa region was 86–87 bp (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Comparison of the Large Single-Copy (LSC), Small Single-Copy (SSC), and inverted repeat (IR) boundary regions across the 33 Pinus chloroplast genomes

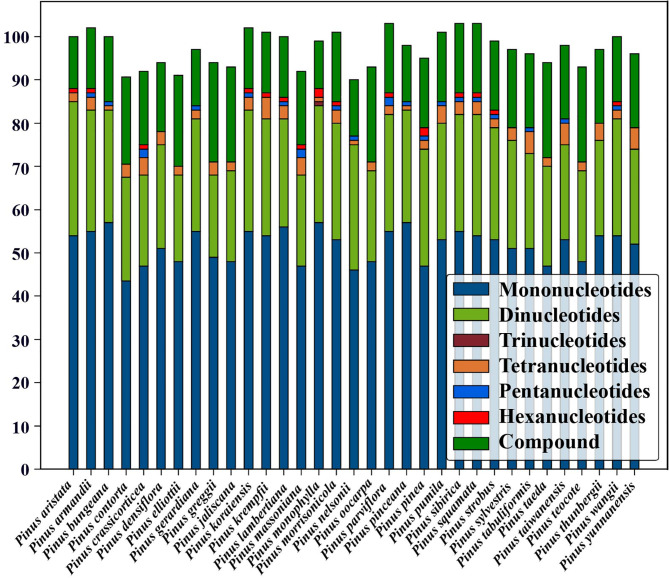

SSRs and long repeats analysis

A total of 3,205 simple sequence repeats (SSRs) with a length ranging from 8 to 230 bp were detected in the studied 33 species. Among them, there were 1,708 mononucleotide repeats with the highest frequency, mainly A or T single nucleotide, with obvious base preference. The rest were dinucleotide (817), compound (548), tetranucleotide (92), pentanucleotide (22), hexanucleotide (17), and trinucleotide repeats (1). The number of trinucleotide repeats was the least, and it appeared only once in P. monophylla. Only 4 types of SSRs were detected in 10 species, all of which lacked trinucleotide, pentanucleotide, and hexanucleotide repeats. The comparison results among the 33 species showed that the largest number of SSRs (103) appeared in P. parviflora, P. sibirica, and P. squamata, and the smallest number (90) appeared in P. nelsonii (Fig. 5; Table S2).

Fig. 5.

Numbers and types of simple sequence repeats (SSR) in the 33 Pinus chloroplast genomes

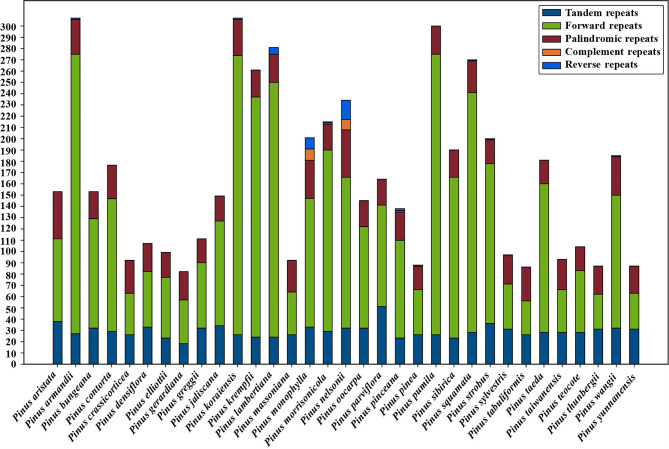

A total of 5,436 long repeats were detected across the 33 species, including tandem (965), forward (3531), palindromic (876), complement (21), and reverse (43) repeats. Among these sequences, forward repeats were the most abundant. The species comparison results showed that P. armandii and P. koraiensis contained the largest number of repeat sequences (307), and P. gerardiana was the least (82). The difference of forward repeats among species was the most obvious, and the difference between the species (P. pumila) with the largest number and the species (P. tabuliformis) with the smallest number was 219. The number of tandem repeats and palindromic repeats was similar, the species with the largest number of tandem repeats was P. parviflora (51), and the species with the largest number of palindromic repeats were P. aristata (42) and P. nelsonii (42). The number of complement repeats was the least, and only appears in 4 species (P. monophylla, P. morrisonicola, P. nelsonii, P. pinceana). There were no reverse repeats detected in 21 species (Fig. 6; Table S3).

Fig. 6.

Analyses of repeated sequences in complete chloroplast genomes of 33 Pinus species

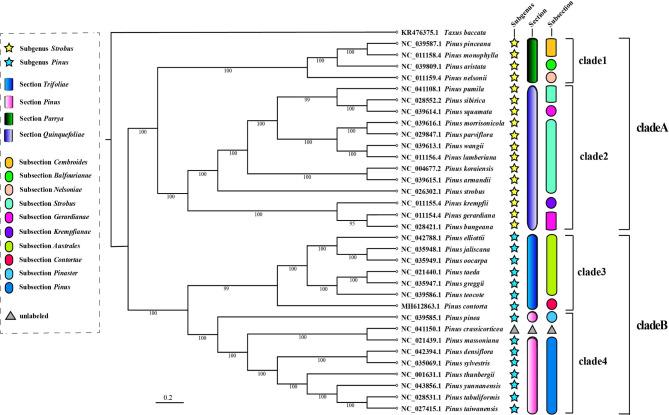

Revisiting the phylogenetic relationships with complete chloroplast genomes

The complete chloroplast genomes of the 33 species were analyzed by maximum likelihood (ML) method. Gernandt et al. [9] proposed a traditional classification system through chloroplast gene sequences, based on which we annotated the phylogenetic results. The 33 studied species cover 2 Subgenera, 4 Sections, and 10 Subsections of the traditional classification system. The phylogenetic tree showed that the 33 species were divided into 2 large branches and 4 small branches, which were consistent with the traditional classification system. This result strongly supported the feasibility of Subgenus and Section in the traditional classification. However, there were still some issues in the Subsections division. Gernandt et al. [9] classified P. squamata as Subsection Gerardianae, but our phylogenetic analysis results were not supportive. P. squamata and species in the Subsection Strobus were clustered into one branch, and were closest to P. sibirica in the Subsection Strobus. Therefore, it could be considered to be included in Subsection Strobus. In addition, P. crassicorticea, which had never been mentioned in the traditional classification system, was classified as Subgenus Pinus, Section Pinus, Subsection Pinus according to its phylogenetic position (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Maximum-likelihood phylogenetic tree based on complete chloroplast genome sequences of 33 Pinus species. Taxus baccata was used as outgroup

Discussion

IR regions reduction resulted in variable cpDNA sizes in Pinus

Chloroplast genomes of most terrestrial plants were composed of double stranded closed circular DNA molecules with conservative structure and typical quadripartite structure, including a LSC, a SSC, and two IR regions separated by LSC and SSC regions [17]. Although the chloroplast genomes of most gymnosperms, such as cycads, Ginkgo and Gnetophytes, had the typical quadripartite structure of seed plants [38–41], they had changed in the chloroplast genomes of Pinaceae and Cupressophytes. In previous studies, it was proposed that the IR was highly simplified in Pinaceae, but completely lost in Cupressophytes, and Pinaceae and Cupressophytes lost different IR copies, Pinaceae lost IRb, and Cupressophytes lost IRa [42, 43]. P. thunbergii in Pinus also proved that each IR region was shortened to 495 bp [44]. Our results were similar to the previous conclusions, the quadripartite structure of the studied 33 pine species was not obvious, and the size of each IR region is only 267–495 bp, showing a decreasing trend. However, IRa and IRb did not differ in size, and also did not reflect the IRb loss (Table 1). In addition, the results showed that there was no significant difference in the size of LSC and SSC regions, and there was a possibility that part of IR region could be translocated into SSC region. The chloroplast genome of seed plants usually contains 101–118 different genes [45], and the genome size ranges from 120 to 160 kb [46]. The studied 33 pine species contained 108 different genes, and the size of chloroplast genome ranged from 114,082 to 121,530 bp (Tables 1 and 2). It can be seen that the reduction of IR region resulted in the size of chloroplast genome, and the types of genes in Pinus are lower than those in other seed plants. Although the chloroplast genomes of Pinaceae and Cupressophytes do not contain typical IR, they still evolve specific IR related to chloroplast genome rearrangement. The chloroplast genomes of some conifers have shown very low collinearity [43, 47]. Strauss et al. [48] also speculated that in Pinaceae cpDNA, rearrangement may occur after IR reduction. However, genome synteny (Fig. S1) of Pinus chloroplast genomes revealed no obvious gene rearrangement events. This may be related to the strong conservation and high similarity of pines chloroplast genome structure.

Significance of chloroplast markers in population genetics

The existence and nature of repeat sequences had been proven to be of great significance for evolution and population genetics studies [49, 50]. A total of 7 types of SSRs were detected in the 33 pine species, of which 1,078 were mononucleotide repeats, mainly A or T single nucleotide, with base preference (Fig. 5; Table S2). The A/T base preference of pines chloroplast genomes was the same as that of many seed plants, SSRs were usually composed of polyA or polyT repeat sequences [51–54]. Recently, genomic SSRs markers have been widely used in Pinus [55–57]. However, compared with genomic SSRs, chloroplast SSRs markers were abundant in number, high in polymorphism and rich in species variability [58]. The newly discovered SSRs in this study will contribute to future studies on Pinus genetic diversity and phylogeography. Pines are rich in long repeats, a total of 5,436 repeats were detected in the studied 33 species, of which forward repeats had the highest frequency (Fig. 6; Table S3). All repeats detected in this study, together with the above SSRs, had laid a foundation for the development of population genetic markers [59].

We screened 16 regions with the highest Pi values among the studied 33 pines, the regions they represent were psbM-trnD-trnY-trnE-clpP-rps12 and chlN-ycf1 (Fig. 3; Table S1). These two highly variable regions will provide potential molecular markers for population genetics studies. In gymnosperms, chloroplasts were generally inherited by paternity [60, 61]. Therefore, the highly variable regions detected in the present study can provide information for the development of specific DNA bar codes of Pinus, and then serve as an effective means to identify male pines parents.

Phylogenetic analysis of complete chloroplast genome reconstruction

Chloroplast genome was characterized by abundant gene capacity, conservative structure, low evolution rate, and high copy number. It had always been the main object of phylogenetic and molecular evolution research [45, 62]. Studies on the phylogeny of chloroplast genome initially relied on single gene sequences [63, 64], but single gene sequences contained less information, resulting in low support rates for many branches [30, 65, 66]. With the accumulation of data, the resolution and support rate of multi gene joint sequence reconstruction phylogenetic analysis had been significantly improved [67–69], and had been widely used [18, 20]. Among them, Gernandt et al. [9] conducted phylogenetic analysis based on chloroplast matK and rbcL sequences of 101 species of pines and constructed the classification system of Pinus. However, with the accumulation of complete genome data of Pinus chloroplasts, it was necessary to verify the traditional classification system. In this study, we reconstructed the phylogenetic relationships of the complete cp. genomes of the 33 pine species. Except for P. squamata, the classification of other species was consistent with the traditional results. Different from previous research results [9, 13–16], this study supported P. squamata to join Subsection Strobus (Fig. 7). Similarly, P. nelsonii, P. krempfii, and P. contorta also had the problem of unclear classification in previous studies [70], and the present study also gave reference which supported P. nelsonii joining Section Parrya, P. krempfii joining Section Quinquefoliae and P. contorta joining Section Trifoliae. This work is helpful to further understanding the evolution of chloroplasts in Pinus and will promote the research progress of pines phylogeny and taxonomy.

Conclusions

We conducted comparative and phylogenetic analyses of the complete chloroplast genomes of 33 pine species. Pinus chloroplast genomes structure was conservative, sequence similarity was high, and the IR region showed a decreasing trend. The discovery of two highly variable regions provided reference information for the development of Pinus chloroplast DNA bar code for future use. We reconstructed the phylogenetic relationship among the 33 pine species using the complete chloroplast genomes, which provided better resolution than that from traditional chloroplast DNA sequences. According to the phylogenetic results, we verified the traditional classification system and revised the position of P. squamata. With the increasing abundance of chloroplast genome information in Pinus, the systematic analysis and summary will enhance our understanding of Pinus evolutionary history, phylogeny, and taxonomy.

Materials and methods

Data collection and processing

The chloroplast genome sequences of 33 published pine species were downloaded from NCBI, including P. taristata, P. armandii, P. bungeana, P. contorta, P. crassicorticea, P. densiflora, P. elliottii, P. gerardiana, P. greggii, P. jaliscana, P. koraiensis, P. krempfii, P. lambertiana, P. massoniana, P. monophylla, and P. morrisonicola, P. nelsonii, P. oocarpa, P. parviflora, P. pinceana, P. pinea, P. pumila, P. sibirica, P. squamata, P. strobus, P. sylvestris, P. tabuliformis, P. taeda, P. taiwanensis, P. teocote, P. thunbergii, P. wangii, and P. yunnanensis. The sequences of 33 complete chloroplast genomes were aligned using MAFFT v7.0 [71] and then manually checked and modified for subsequent analysis.

Comparative genomic analysis

mVISTA v.7 program [72] was used for multiple sequence alignment analysis, and the sequences were processed by CPGAVAS2 (http://www.herbalgenomics.org/cpgavas). Considering the chloroplast genome of P. armandii as a reference, the differences of the whole chloroplast genome of the 33 pine species were compared under the Shuffle-LAGAN model. Nucleotide diversity was used as a parameter to identify the cp. genome highly variable region. Here, we used DnaSP v.6.1 [73] software to estimate nucleotide diversity, the step length and window length were set to 200 and 800 bp, respectively, then used GraphPad-prism v.9.0 (https://www.graphpad.com/scientific-software/prism) to visualize the data. Chloroplast genome rearrangement analysis was performed using the default settings of the Mauve v.2.3 [74] plug-in in Geneious v.11.0 [75].

Detection of long repeat sequences and simple sequence repeats

The online REPuter (https://bibiserv.cebitec.uni-bielefeld.de/reputer) [76] was used to identify long repeats (tandem, forward, reverse, palindromic, and complement repeats). The minimum repetition size was limited to no less than 30 basis points, the Hamming distance value was 3, and other settings remained at the default value. The SSRs of the chloroplast genomes of the 33 pine species were identified by microsatellite marker identification tool (MISA) (https://webblast.ipk-gatersleben.de/misa), the minimum number of repeats was used to identify mononucleotides, dinucleotides, trinucleotides, tetranucleotides, pentanucleotides, and hexanucleotides were 8, 4, 4, 3, 3 and 3, respectively; the sequence length between two SSRs was no more than 100 bp, and it was registered as a compound [77].

Phylogenetic analysis

In order to determine the phylogenetic location of the 33 pine species, we used the complete chloroplast genome sequences for phylogenetic analysis with Taxus as an outgroup. The complete chloroplast genome sequences were downloaded from NCBI. MAFFT v7.0 [71] was used for sequence alignment, and ModelFinder [78] was used to find the most suitable alternative models TVM + F + R2 for the complete chloroplast genome sequences. Phylogeny was constructed by ML analysis, and ML analysis was performed by IQ-tree v1.6 [79] with 1000 bootstrap repeats. Using Figtree v1.4 (https://github.com/rambaut/Figtree) edit the two phylogenetic trees.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Authors’ contributions

QX analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. HZ and DL collected data and samples in the field. WL and YAE conceived the study and revised the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by grant from National Key R&D Plan for the Fourteenth Five Year Plan (2022YFD2200304).

Data Availability

All data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and within its supplementary materials published online. All data used in the study were collected in the public database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/). Accession numbers of 33 species are as follow: P. aristate, NC_039809.1; P. armandii, NC_029847.1;

P. bungeana, NC_028421.1; P. contorta, MH612863.1; P. crassicorticea, NC_041150.1; P. densiflora, NC_042394.1; P. elliottii, NC_042788.1; P. gerardiana, NC_011154.4; P. greggii, NC_035947.1; P. jaliscana, NC_035948.1; P. koraiensis, NC_004677.2; P. krempfii, NC_011155.4; P. lambertiana, NC_011156.4;

P. massoniana, NC_021439.1; P. monophyla, NC_011158.4; P. morrisonicola, NC_039616.1; P. nelsonii, NC_011159.4; P. oocarpa, NC_035949.1; P. parviflora, NC_039615.1; P. pinceana, NC_039587.1; P. pinea, NC_039585.1; P. pumila, NC_041108.1; P. sibirica, NC_028552.2; P. squamata, NC_039614.1; P. strobus, NC_026302.1; P. sylvestris, NC_035069.1; P. tabuliformis, NC_028531.1; P. taeda, NC_021440.1; P. taiwanensis, NC_027415.1; P. teocote, NC_039586.1; P. thunbergii, NC_001631.1; P. wangii, NC_039613.1; P. yunnanensis, NC_043856.1.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable. No specific permits were required for the collection of specimens for this study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Richardson DM. Ecology and biogeography of Pinus. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Klymiuk AA, Stockey RA, Rothwell GW. The first organismal concept for an extinct species of Pinaceae. Int J Plant Sci. 2011;172:294–313. doi: 10.1086/657649. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Willyard A, Syring J, Gernandt DS, Liston A, Cronn R. Fossil calibration of molecular divergence infers a moderate mutation rate and recent radiations for Pinus. Mol Biol Evol. 2007;24(1):90–101. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msl131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu L, Hao ZZ, Liu YY, Wei XX, Cun YZ, Wang XQ. Phylogeography of Pinus armandii and its relatives: heterogeneous contributions of geography and climate changes to the genetic differentiation and diversification of chinese white pines. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(1):e85920. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0085920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zeb U, Dong WL, Zhang TT, Wang RN, Shahzad K, Ma XF, et al. Comparative plastid genomics of Pinus species: insights into sequence variations and phylogenetic relationships. J Syst Evol. 2020;58(2):118–32. doi: 10.1111/jse.12492. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jin WT, Gernandt DS, Wehenkel C, Xia XM, Wei XX, Wang XQ. Phylogenomic and ecological analyses reveal the spatiotemporal evolution of global pines. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2021;118(20):e2022302118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2022302118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zheng WJ, Fu LG. Flora of China. Beijing: Science Press; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Little EL, Critchfield WB. Subdivisions of the genus Pinus (pines) Washington: Miscellaneous Publication; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gernandt DS, López GG, García SO, Liston A. Phylogeny and classification of Pinus. Taxon. 2005;54(1):29–42. doi: 10.2307/25065300. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gernandt DS, Liston A, Piñero D. Phylogenetics of Pinus subsections Cembroides and Nelsoniae inferred from cpDNA sequences. Syst Bot. 2003;28(4):657–73. doi: 10.1043/02-63.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Saladin B, Leslie AB, Wüest RO, Litsios G, Conti E, Salamin N, et al. Fossils matter: improved estimates of divergence times in Pinus reveal older diversification. BMC Evol Biol. 2017;17(1):95. doi: 10.1186/s12862-017-0941-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Singh SP, Gumber S, Singh RD, Pandey R. Differentiation of diploxylon and haploxylon pines in spatial distribution, and adaptational traits. Acta Ecol Sin. 2023;43(1):1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.chnaes.2021.07.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li XW. Pinus yunnanensis-new series-new species. Acta Bot Yunnanica. 1992;14(3):258–60. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Price RA, Liston A, Strauss SH. Phylogeny and systematics of Pinus. Cambridge Univ; 2000.

- 15.Li XP, Zhu ZD. Analysis of fatty acids in seed oil of Pinus bungeana and its taxonomic problems. J Nanjing Forest Univ (Nat Sci) 1993;36(01):27–34. doi: 10.3969/j.jssn.1000-2006.1993.01.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang CM, Li XW, Mu QY, Xiao SQ. Study on wood structure and classification of Pinus bungeana. J Sichuan Agric Univ. 1998;16(1):165–9. doi: 10.16036/j.issn.1000-2650.1998.01.026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mower JP, Vickrey TL. Structural diversity among plastid genomes of land plants. Adv Bot Res. 2018;85:263–92. doi: 10.1016/bs.abr.2017.11.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moore MJ, Soltis PS, Bell CD, Burleigh JG, Soltis DE. Phylogenetic analysis of 83 plastid genes further resolves the early diversification of eudicots. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(10):4623–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907801107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cai Z, Penaflor C, Kuehl JV, Leebens-Mack J, Carlson JE, dePamphilis CW, et al. Complete plastid genome sequences of Drimys, Liriodendron, and Piper: implications for the phylogenetic relationships of magnoliids. BMC Evol Biol. 2006;6:77. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-6-77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jansen RK, Cai Z, Raubeson LA, Daniell H, dePamphilis CW, Leebens-Mack J, et al. Analysis of 81 genes from 64 plastid genomes resolves relationships in angiosperms and identifies genome-scale evolutionary patterns. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(49):19369–74. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709121104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jansen RK, Kaittanis C, Saski C, Lee SB, Tomkins J, Alverson AJ, et al. Phylogenetic analyses of Vitis (Vitaceae) based on complete chloroplast genome sequences: effects of taxon sampling and phylogenetic methods on resolving relationships among rosids. BMC Evol Biol. 2006;6:32. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-6-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moore MJ, Bell CD, Soltis PS, Soltis DE. Using plastid genome-scale data to resolve enigmatic relationships among basal angiosperms. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(49):19363–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708072104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Parks M, Cronn R, Liston A. Increasing phylogenetic resolution at low taxonomic levels using massively parallel sequencing of chloroplast genomes. BMC Biol. 2009;7:84. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-7-84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goremykin VV, Holland B, Hirsch-Ernst KI, Hellwig FH. Analysis of Acorus calamus chloroplast genome and its phylogenetic implications. Mol Biol Evol. 2005;22(9):1813–22. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msi173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leebens-Mack J, Raubeson LA, Cui L, Kuehl JV, Fourcade MH, Chumley TW, et al. Identifying the basal angiosperm node in chloroplast genome phylogenies: sampling one’s way out of the Felsenstein zone. Mol Biol Evol. 2005;22(10):1948–63. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msi191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lin CP, Huang JP, Wu CS, Hsu CY, Chaw SM. Comparative chloroplast genomics reveals the evolution of Pinaceae genera and subfamilies. Gen Biol and Evol. 2010;2:504–17. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evq036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang SD, Jin JJ, Chen SY, Chase MW, Soltis DE, Li HT, et al. Diversification of Rosaceae since the late cretaceous based on plastid phylogenomics. New Phytol. 2017;214(3):1355–67. doi: 10.1111/nph.14461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li HT, Yi TS, Gao LM, Ma PF, Zhang T, Yang JB, et al. Origin of angiosperms and the puzzle of the jurassic gap. Nat Plants. 2019;5(5):461–70. doi: 10.1038/s41477-019-0421-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Meng KK, Chen SF, Xu KW, Zhou RC, Li MW, Dhamala MK, et al. Phylogenomic analyses based on genome-skimming data reveal cyto-nuclear discordance in the evolutionary history of Cotoneaster (Rosaceae) Molec Phylogen Evol. 2021;158:107083. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2021.107083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Delsuc F, Brinkmann H, Philippe H. Phylogenomics and the reconstruction of the tree of life. Nat Rev Genet. 2005;6(5):361–75. doi: 10.1038/nrg1603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shinozaki K, Ohme M, Tanaka M, Wakasugi T, Hayashida N, Matsubayashi T, et al. The complete nucleotide sequence of the tobacco chloroplast genome: its gene organization and expression. EMBO J. 1986;5(9):2043–9. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1986.tb04464.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jansen RK, Cai Z, Raubeson LA, Daniell H, Depamphilis CW, Leebens-Mack J, et al. Analysis of 81 genes from 64 plastid genomes resolves relationships in angiosperms and identifies genome-scale evolutionary patterns. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(49):19369–74. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709121104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thomas F, Massenet O, Dorne AM, Briat JF, Mache R. Expression of the rpl23, rpl2 and rps19 genes in spinach chloroplasts. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16(6):2461–72. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.6.2461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schmitz-Linneweber C, Maier RM, Alcaraz JP, Cottet A, Herrmann RG, Mache R. The plastid chromosome of spinach (Spinacia oleracea): complete nucleotide sequence and gene organization. Plant Mol Biol. 2001;45(3):307–15. doi: 10.1023/a:1006478403810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Doyle JJ, Doyle JL, Palmer JD. Multiple independent losses of two genes and one intron from legume chloroplast genome. Syst Bot. 1995;20(3):272–94. doi: 10.2307/2419496. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ohyama K. Chloroplast and mitochondrial genomes from a liverwort, Marchantia polymorpha–gene organization and molecular evolution. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 1996;60(1):16–24. doi: 10.1271/bbb.60.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee HL, Jansen RK, Chumley TW, Kim KJ. Gene relocations within chloroplast genomes of Jasminum and Menodora (Oleaceae) are due to multiple, overlapping inversions. Mol Biol Evol. 2007;24(5):1161–80. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McCoy SR, Kuehl JV, Boore JL, Raubeson LA. The complete plastid genome sequence of Welwitschia mirabilis: an unusually compact plastome with accelerated divergence rates. BMC Evol Biol. 2008;8:130. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-8-130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wu CS, Lai YT, Lin CP, Wang YN, Chaw SM. Evolution of reduced and compact chloroplast genomes (cpDNAs) in gnetophytes: selection toward a lower-cost strategy. Mol Phylogen Evol. 2009;52(1):115–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2008.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lin CP, Wu CS, Huang YY, Chaw SM. The complete chloroplast genome of Ginkgo biloba reveals the mechanism of inverted repeat contraction. Genome Biol Evol. 2012;4(3):374–81. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evs021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wu CS, Wang YN, Liu SM, Chaw SW. Chloroplast genome (cpDNA) of Cycas taitungensis and 56 cp protein-coding genes of Gnetum parvifolium: insights into cpDNA evolution and phylogeny of extant seed plants. Mol Biol Evol. 2007;24(6):1366–79. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wu CS, Wang YN, Hsu CY, Lin CP, Chaw SM. Loss of different inverted repeat copies from the chloroplast genomes of Pinaceae and cupressophytes and influence of heterotachy on the evaluation of gymnosperm phylogeny. Genome Biol Evol. 2011;3:1284–95. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evr095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wu CS, Chaw SM. Highly rearranged and size-variable chloroplast genomes in conifers II clade (cupressophytes): evolution towards shorter intergenic spacers. Plant Biotechnol J. 2014;12(3):344–53. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wakasugi T, Tsudzuki J, Ito S, Nakashima K, Tsudzuki T, Sugiura M. Loss of all ndh genes as determined by sequencing the entire chloroplast genome of the black pine Pinus thunbergii. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91(21):9794–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.21.9794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jansen RK, Ruhlman TA. Plastid genomes of seed plants. Springer Netherlands; 2012.

- 46.Wicke S, Schneeweiss GM, dePamphilis CW, Müller KF, Quandt D. The evolution of the plastid chromosome in land plants: gene content, gene order, gene function. Plant Mol Biol. 2011;76(3–5):273–97. doi: 10.1007/s11103-011-9762-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wu CS, Lin CP, Hsu CY, Wang RJ, Chaw SM. Comparative chloroplast genomes of Pinaceae: insights into the mechanism of diversified genomic organizations. Genome Biol Evol. 2011;3:309–19. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evr026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Strauss SH, Palmer JD, Howe GT, Doerksen AH. Chloroplast genomes of two conifers lack a large inverted repeat and are extensively rearranged. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988;85(11):3898–902. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.11.3898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cavalier-Smith T. Chloroplast evolution: secondary symbiogenesis and multiple losses. Curr Biol. 2002;12(2):R62–4. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00675-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nie X, Lv S, Zhang Y, Du X, Wang L, Biradar SS, et al. Complete chloroplast genome sequence of a major invasive species, crofton weed (Ageratina adenophora) PLoS ONE. 2012;7(5):e36869. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cheon KS, Kim KA, Kwak M, Lee B, Yoo KO. The complete chloroplast genome sequences of four Viola species (Violaceae) and comparative analyses with its congeneric species. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(3):e0214162. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0214162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yang J, Hu G, Hu G. Comparative genomics and phylogenetic relationships of two endemic and endangered species (Handeliodendron bodinieri and Eurycorymbus cavaleriei) of two monotypic genera within Sapindales. BMC Genomics. 2022;23(1):27. doi: 10.1186/s12864-021-08259-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Xu K, Lin C, Lee SY, Mao L, Meng K. Comparative analysis of complete Ilex (Aquifoliaceae) chloroplast genomes: insights into evolutionary dynamics and phylogenetic relationships. BMC Genomics. 2022;23(1):203. doi: 10.1186/s12864-022-08397-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wu L, Nie L, Xu Z, Li P, Wang Y, He C, et al. Comparative and phylogenetic analysis of the complete chloroplast genomes of three Paeonia Section Moutan Species (Paeoniaceae) Front Genet. 2020;11:980. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2020.00980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yang B, Sun H, Qi J, Niu S, Ei-Kassaby YA, Li W. Improved genetic distance-based spatial deployment can effectively minimize inbreeding in seed orchard. For Ecosyst. 2020;7(1):117–27. doi: 10.1186/s40663-020-0220-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Miao YB, Fang P, Yang ZH, Zhu XM, Gao Q, Liu Y, et al. Genetic structure analysis of Pinus sylvestris var. Mongolica under different geographical environments. J Beijing For Univ. 2018;40(10):43–50. doi: 10.13332/j.1000-1522.20170438. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Liu L, Zhang S, Lian C. De Novo Transcriptome sequencing analysis of cDNA Library and large-scale Unigene Assembly in Japanese Red Pine (Pinus densiflora) Int J Mol Sci. 2015;16(12):29047–59. doi: 10.3390/ijms161226139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ebert D, Peakall R. Chloroplast simple sequence repeats (cpSSRs): technical resources and recommendations for expanding cpSSR discovery and applications to a wide array of plant species. Mol Ecol Resour. 2009;9:673–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-0998.2008.02319.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nie X, Lv S, Zhang Y, Du X, Wang L, Biradar SS, et al. Complete chloroplast genome sequence of a major invasive species, crofton weed (Ageratina adenophora) PLoS ONE. 2012;7(5):e36869. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sutton BC, Flanagan DJ, El-Kassaby YA. A simple and rapid method for estimating representation of species in spruce seedlots using chloroplast DNA restriction fragment length polymorphism. Silvae Genet. 1991;40:119–23. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sutton BC, Flanagan DJ, Gawley JR, Newton CH, Lester DT, El-Kassaby YA. Inheritance of chloroplast and mitochondrial DNA in Picea and composition of hybrids from introgression zones. Theor Appl Genet. 1991;82(2):242–8. doi: 10.1007/BF00226220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Korpelainen H. The evolutionary processes of mitochondrial and chloroplast genomes differ from thoseof nuclear genomes. Sci Nat. 2004;91(11):505–18. doi: 10.1007/s00114-004-0571-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Savolainen V, Chase MW, Hoot SB, Morton CM, Soltis DE, Bayer C, et al. Phylogenetics of flowering plants based on combined analysis of plastid atpB and rbcL gene sequences. Syst Biol. 2000;49(2):306–62. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/49.2.306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chase MW, Soltis DE, Olmstead RG, Morgan DL, Donald H, Mishler BD, et al. Phylogenetics of seed plants:an analysis of nucleotide sequences from the plastid gene rbcL. Ann Mo Bot Gard. 1993;80(3):528–50. doi: 10.2307/2399846. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rokas A, Williams BL, King N, Carroll SB. Genome-scale approaches to resolving incongruence in molecular phylogenies. Nature. 2003;425(6960):798–804. doi: 10.1038/nature02053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Jeffroy O, Brinkmann H, Delsuc F, Philippe H. Phylogenomics: the beginning of incongruence? Trends Genet. 2006;22(4):225–31. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2006.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Qiu YL, Lee J, Bernasconi-Quadroni F, Soltis PS, Zanis M, Zimmer EA, et al. The earliest angiosperms: evidence from mitochondrial, plastid and nuclear genomes. Nature. 1999;402(6760):404–7. doi: 10.1038/46536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Soltis PS, Soltis DE, Chase MW. Angiosperm phylogeny inferred from multiple genes as a tool for comparative biology. Nature. 1999;402(6760):402–4. doi: 10.1038/46528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Fishbein M, Hibsch-Jetter C, Soltis DE, Hufford L. Phylogeny of Saxifragales (angiosperms, eudicots): analysis of a rapid, ancient radiation. Syst Biol. 2001;50(6):817–47. doi: 10.1080/106351501753462821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Syring J, Willyard A, Cronn R, Liston A. Evolutionary relationships among Pinus (Pinaceae) subsections inferred from multiple low-copy nuclear loci. Am J Bot. 2005;92(12):2086–100. doi: 10.3732/ajb.92.12.2086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Katoh K, Standley DM. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Mol Biol Evol. 2013;30(4):772–80. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Mayor C, Brudno M, Schwartz JR, Poliakov A, Rubin EM, Frazer KA, et al. VISTA: visualizing global DNA sequence alignments of arbitrary length. Bioinformatics. 2000;16(11):1046–7. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/16.11.1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Librado P, Rozas J. DnaSP v5: a software for comprehensive analysis of DNA polymorphism data. Bioinformatics. 2009;25(11):1451–2. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Darling AC, Mau B, Blattner FR, Perna NT. Mauve: multiple alignment of conserved genomic sequence with rearrangements. Genome Res. 2004;14:1394–403. doi: 10.1101/gr.2289704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kearse M, Moir R, Wilson A, Stones-Havas S, Cheung M, Sturrock S, et al. Geneious basic: an integrated and extendable desktop software platform for the organization and analysis of sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2012;28(12):1647–9. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kurtz S, Choudhuri JV, Ohlebusch E, Schleiermacher C, Stoye J, Giegerich R. REPuter: the manifold applications of repeat analysis on a genomic scale. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:4633–42. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.22.4633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Beier S, Thiel T, Münch T, Scholz U, Mascher M. MISA-web: a web server for microsatellite prediction. Bioinformatics. 2017;33(16):2583–5. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btx198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kalyaanamoorthy S, Minh BQ, Wong TKF, von Haeseler A, Jermiin LS. ModelFinder: fast model selection for accurate phylogenetic estimates. Nat Methods. 2017;14(6):587–9. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Nguyen LT, Schmidt HA, von Haeseler A, Minh BQ. IQ-TREE: a fast and effective stochastic algorithm for estimating maximum-likelihood phylogenies. Mol Biol Evol. 2015;32(1):268–74. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msu300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and within its supplementary materials published online. All data used in the study were collected in the public database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/). Accession numbers of 33 species are as follow: P. aristate, NC_039809.1; P. armandii, NC_029847.1;

P. bungeana, NC_028421.1; P. contorta, MH612863.1; P. crassicorticea, NC_041150.1; P. densiflora, NC_042394.1; P. elliottii, NC_042788.1; P. gerardiana, NC_011154.4; P. greggii, NC_035947.1; P. jaliscana, NC_035948.1; P. koraiensis, NC_004677.2; P. krempfii, NC_011155.4; P. lambertiana, NC_011156.4;

P. massoniana, NC_021439.1; P. monophyla, NC_011158.4; P. morrisonicola, NC_039616.1; P. nelsonii, NC_011159.4; P. oocarpa, NC_035949.1; P. parviflora, NC_039615.1; P. pinceana, NC_039587.1; P. pinea, NC_039585.1; P. pumila, NC_041108.1; P. sibirica, NC_028552.2; P. squamata, NC_039614.1; P. strobus, NC_026302.1; P. sylvestris, NC_035069.1; P. tabuliformis, NC_028531.1; P. taeda, NC_021440.1; P. taiwanensis, NC_027415.1; P. teocote, NC_039586.1; P. thunbergii, NC_001631.1; P. wangii, NC_039613.1; P. yunnanensis, NC_043856.1.