Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic forced health systems to rapidly shift to deliver healthcare virtually, however, there is a limited understanding of this shift from the patient's perspective. We conducted semi-structured interviews with patients in three clinical areas (mental health, chronic care, and surgical care) and used patient journey mapping to visualize their experiences. Themes suggest that (1) patient's preference of modalities was contextually dependent, (2) that providers must continually converse with patients to select appropriate modalities, and (3) that providers must account for multiple factors such as a patient's digital and health literacy, comfort level with the modality and their medical needs.

Keywords: patient expectations, clinician–patient relationship, patient perspectives/narratives, patient engagement, telehealth

Introduction

Virtual care is not new to Canada; however, the pandemic encouraged its widespread adoption among clinicians from a low and stable baseline.1,2 Healthcare systems scaled virtual care delivery models at an unprecedented pace to maintain hospital capacity and have maintained it between waves of the pandemic. 3 Despite the several years of experience with high rates of virtual care use, there is limited understanding of the implementation and ongoing use of virtual technologies from a patient's perspective.

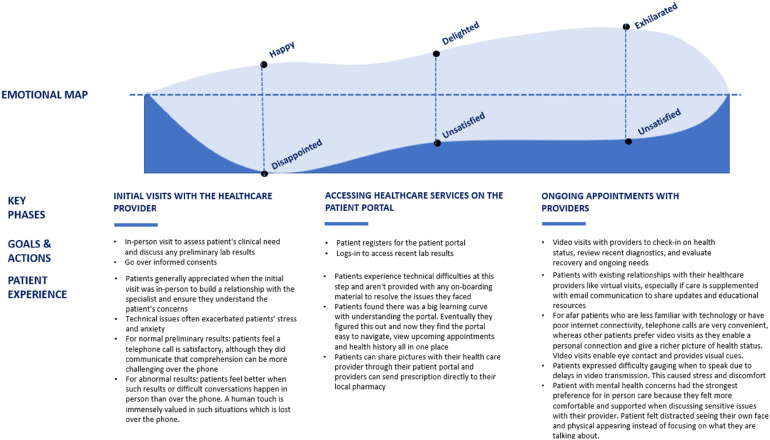

Patient Journey Mapping

Patient journey maps are a visual representation of a patient's experience with the healthcare system. This tool captures insights into a patient's activities, interactions with virtual technologies, feelings, and motivations through each key phase. It also highlights pain points, which presents opportunities to develop meaningful solutions.

Objectives

This paper uses patient journey mapping to describe patient experiences interacting with virtual care modalities in their healthcare journey. We present three distinct profiles and describe the similarities and differences in experiences interacting with virtual care technologies. The map developed can help optimize virtual care services in the future.

Results

Three distinct profiles were developed after analyzing the patient interviews in three clinical areas- mental health, chronic care, and surgical care. We identified three key phases evident in their journeys: (1) initial visit, (2) accessing healthcare information and booking appointments, and (3) ongoing appointments. These phases were mapped as one patient journey map (Figure 1). The critical challenges that patients in each profile faced are outlined.

Figure 1.

Patient journey map.

Mental Health

Description

Patient X has depression and anxiety and access their nurse and psychiatrist via phone and video. X found video consultations exacerbated their mental health symptoms.

Challenge: Video Consults can Exacerbate Mental Health Symptoms

X understands that clinicians need to see their body language to provide appropriate treatment; however, they find it distracting that they can see their own face over the call. This causes them to look away from the screen which disrupts their thought process. Therefore, X prefers in-person visits to virtual care modalities; however, if they had to use virtual care, their preference would still be to use video because it allows them to see their provider.

“It's distracting to me to see my face up there when I am trying to talk to the doctor or the nurse or whoever … I keep looking away from the screen because even out of the corner of my eye, I can see that I’m on the screen … It would be like having an in-person interview with a mirror in front of me. I would not be comfortable with it.” —Patient X

Solution: Lessons Learned

This exemplifies the need for healthcare providers to consider patient choice when determining the optimal modality to deliver patient care virtually and to continually engage in conversations with patients to understand whether virtual care was meeting their needs. In this case, asking X to turn off their video, while keeping their video on could have helped the provide alleviate X's discomfort.

Chronic Care

Description

Patient Y sees a nephrologist and urologist every 6 months to manage their chronic kidney disease. During the pandemic, they accessed these providers virtually through video and phone. Y established a strong relationship with their specialists because of their regular contact. Therefore, when Y was diagnosed with gout and prescribed a medication, they contacted their nephrologist for make sure it was safe. Their attempt was unsuccessful.

Challenge: Disconnect Between Providers in a Patient's Circle of Care

Y's disease requires regular appointments with providers with whom they already have a relationship. Therefore, they generally preferred virtual care for their occasional visits.

“To be honest, that visit for three and a half hours, it was wonderful that I was at home because I had the luxury of my home. So, if I wanted to lay down and talk to them I can, or sit up, or if I want to grab a drink or snack, where if I was in the hospital … I wouldn’t be doing that”—Patient Y

From Patient Y's experience with gout, they found a disconnection between their family physician and specialists at the hospital. Although it is possible that the nephrologist was away from their office, the lack of timely access to a trusted physician was a major pain point for Y. Appropriate communication among healthcare providers is especially important for those managing chronic illnesses.

“When I ended up with gout I went to my family doctor and then she prescribed me medication … I did get the medication the family doctor prescribed but I was afraid to take it. So, I called the nephrologist a couple times, but he didn’t call me …. So, I suffered with gout for two weeks. I called the nephrologist for two weeks and never heard back …”—Patient Y

Solutions: Lessons Learned

The nature of chronic illnesses allows patients to build strong relationships with their physicians. Therefore, ensuring that these physicians are all connected and accessible via multiple modalities like email, electronic messaging, or phone would help maintain the continuum of care. In this case, had different modalities been leveraged to maintain communication between Y's primary care provider and the nephrologist and/or the physician covering for them (in the case of an absence) Y's quality of care could have been improved. Analyzing this patient's journey provides insight into the disconnect amongst physicians in a patient's care circle and the importance of physician communication using different modalities within and between organizations.

Surgery

Description

Patient Z had a lobectomy after being diagnosed with lung cancer and recovered at home using virtual care to communicate with their providers. During recovery, Z developed a serious infection but was able to treat this by emailing their physician a picture.

Challenge: Building a Strong Relationship With the Surgeon

During the initial lung surgery consult, the surgeon assessed the patient's clinical needs which required taking images to assess the surgical site. Although Z preferred virtual follow-up visits via video or phone modalities, they still indicated that at least one in-person visit is necessary pre-surgery to build rapport with the surgeon.

“I also had a phone visit with a pulmonary specialist, and it was an initial visit, we had never met before, I was just referred to him for breathing issues and I found it really not satisfactory. Because Dr X I have dealt with, so even though I prefer to do an in person visit with him, I know what he's like … We’ve had lots of visits in person, so I have a better understanding of who I’m dealing with, his manner and how he approaches things. To have a referral and a brand-new doctor that I have never met, and I still have never met him, to do that initial visit, like a fact finding visit really does not work for me.”—Patient Z

Solution: Lessons Learned

For patients undergoing surgery, having initial consults in-person builds strong relationships with the clinical team. However, patient preference for type of physician engagement is context dependent. For example, Z was glad they did not have to go in person to have their wound evaluated and appreciated that follow-up appointments occurred virtually.

Evidence of Impact: Comparing Key Phases of Patients’ Journey

Table 1 compares patient experiences among the three profiles. We found that patients X, Y, and Z appreciated having the option to connect with their providers virtually, but their modality preference varied and was context dependent. To address this, providers need to engage in conversations with patients to understand their experience and acknowledge that these preferences may change throughout their healthcare journey.

Table 1.

Similarities and Differences Among Key Phase in the Patient Journeys of Patient X (Mental Health Profile), Patient Y (Chronic Care Profile), and Patient Z (Surgery Profile).

| Similarities | Differences | |

|---|---|---|

| Initial visits with the healthcare provider |

|

|

| Accessing healthcare information and booking appointments on patient portal |

|

|

| Ongoing appointments with healthcare providers |

|

|

Conclusion

The patient journey map highlights distinct dissatisfactions and pain points patients experience within the mental health, chronic care, and surgery profiles. The map demonstrates the importance of patient choice when choosing virtual care modalities and the need for improved coordination among hospital systems, services, and personnel. Guidance on the use of various virtual care modalities can be developed by regulatory organizations which consider speciality-specific nuances including the nature of the healthcare encounter (i.e, initial visit vs follow-up or new vs established relationship), patient preference including access and comfort with technology, and patients’ physical and cognitive capacities. Developing policies outlining patients’ access rights to various virtual care modalities (e.g, when does patient preference supersede, how, and when should it be considered alongside clinical appropriateness) could also support the development of this guidance. Additionally, hospitals can independently mandate that virtual care modalities are driven by patient choice and clinical appropriateness and monitor to ensure adherence. Having said this, considerations should be given to ensure that options are presented seamlessly so providers and patients can switch between modalities. Providers should also feel supported through training, and technical staff when coordinating virtual care delivery (eg, matching encounter reason to appropriate virtual care modality). We found patient journey mapping to be a valuable tool to design health services, as it is a low effort process that can provide operational insights from a patient's perspective and address different populations and use cases.

Footnotes

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical Approval: Ethical approval to report this case series was obtained from Women's College Hospital via Clinical Trials Ontario (CTO# 3356).

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the Ontario Ministry of Health.

Informed Consent: Verbal informed consent was obtained from the patient(s) for their anonymized information to be published in this article.

ORCID iD: Karishini Ramamoorthi https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7066-0560

References

- 1.Canadian Medical Association. VIRTUAL CARE in CANADA: Discussion Paper . 2019. https://www.cma.ca/sites/default/files/pdf/News/Virtual_Care_discussionpaper_v2EN.pdf

- 2.Hafner M, Yerushalmi E, Dufresne E, Gkousis E. The potential socio-economic impact of telemedicine in Canada. Rand Health Q. 2022;9(3):6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Webster P. Virtual health care in the era of COVID-19. Lancet. 2020;395(10231):1180-1. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30818-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]