Abstract

Chronic itch is a socioeconomic burden with limited management options. Non‐histaminergic itch, involved in problematic pathological itch conditions, is transmitted by a subgroup of polymodal C‐fibres. Cowhage is traditionally used for studying experimentally induced non‐histaminergic itch in humans but encounters some limitations. The present study, therefore, aims to design a new human, experimental model of non‐histaminergic itch based on the application of bovine adrenal medulla (BAM)8–22, an endogenous peptide that activates the MrgprX1 receptor. Twenty‐two healthy subjects were recruited. Different concentrations (0.5, 1 and 2 mg/ml) of BAM8‐22 solution and vehicle, applied by a single skin prick test (SPT), were tested in the first session. In the second session, the BAM8‐22 solution (1 mg/ml) was applied by different number of SPTs (1, 5 and 25) and by heat‐inactivated cowhage spicules coated with BAM8‐22. Provoked itch and pain intensities were monitored for 9 min, followed by the measurement of superficial blood perfusion (SBP) and mechanical and thermal sensitivities. BAM8‐22 induced itch at the concentration of 1, 2 mg/ml (p < 0.05) and with the significantly highest intensity when applied through BAM8‐22 spicules (p < 0.001). No concomitant pain sensation or increased SBP was observed. SBP increased only in the 25 SPTs area probably due to microtrauma from the multiple skin penetrations. Mechanical and thermal sensitivities were not affected by any of the applications. BAM8‐22 applied through heat‐inactivated spicules was the most efficient method to induce itch (without pain or changes in SBP and mechanical and thermal sensitivities) suggesting BAM8‐22 as a novel non‐histaminergic, human, experimental itch model.

Keywords: BAM8‐22, itch, non‐histaminergic itch, cowhage spicules, pain

1. INTRODUCTION

Itch, defined as an unpleasant somatosensation that evokes the desire to scratch, 1 could be considered a minor annoyance often associated with harmless episodic pruritus 2 , 3 caused by minor injuries such as mosquito bites. In its acute form, itch simply prompts a relatively short‐lived scratch response in the affected areas; however, in the last decades, itch started to be considered a disease, especially when it persists for more than 6 weeks becoming chronic. 4 Chronic itch occurs under conditions such as psoriasis, prurigo nodularis, uremic pruritus, drug‐induced itching, or atopic dermatitis (AD). 4 Itch interferes with functions such as damaging the affected skin areas, sleep, attention, and sexual activity, resulting in reduced quality of life for up to 10% of patients. 5 , 6 To date, there are no completely efficient treatments for particularly non‐histaminergic itch, 7 although new promising treatment options are under development. 8

Itch is classified into two distinct categories: histaminergic and non‐histaminergic. Histaminergic itch is triggered by a subgroup of mechanoinsensitive C‐fibers (CMi‐fibers) that express on their surface histamine‐receptor 1 and 4 (H1/4R) and transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 (TRPV1). 9 , 10 On the other hand, a subgroup of polymodal C‐fibers (PmC‐fibres) transmits non‐histaminergic itch, and they are activated by two different pathways. 2 , 11 The first one is mediated by the binding to the protease‐activated receptors (PAR2 and PAR4), followed by the co‐activation of transient receptor potential ankyrin 1 (TRPA1) and the transmission through PmC‐ and Aδ‐fibers. 12 , 13 , 14 The second pathway is mediated by the binding to Mas‐related G protein‐coupled receptors (Mrgprs), 11 in particular MrgprA3, MrgprC11 and MrgprX1. 15 The insertion of cowhage spicules (which contain mucunain, an exogenous PAR2‐agonist 12 ) is the most used human experimental model to study non‐histaminergic itch even if the number of spicules is impossible to standardize and difficult to obtain. 16 Bovine adrenal medulla (BAM)8–22 is an endogenous peptide that activates MrgprX1 and induces itch via the G protein‐q/11 α‐subunit (Gαq/11) pathway. 17 , 18 , 19 Sikand et al. 17 demonstrated that skin application of BAM8‐22 evokes itch and nociceptive sensations that are not blocked by an antihistamine drug.

The present study aimed to measure and compare non‐histaminergic itch induced by BAM8‐22 under different conditions: (1) Skin prick test (SPT) with concentrations of 0.5, 1 and 2 mg/ml BAM8‐22 solutions; (2) introducing 1 mg/ml BAM8‐22 solution with different number of lancet SPTs (1, 5 and 25); and (3) by skin insertion of chemically heat‐inactivated cowhage spicules soaked in BAM8‐22 solution (1 mg/ml).

2. METHODS

2.1. Subjects and study design

For the present study, 22 subjects were recruited (14 males and eight females, 25.5 ± 3.9 years, range 19–35). All of them were healthy, and exclusion criteria included acute or chronic itch or pain; skin disease; previous or current neurologic, musculoskeletal or mental illnesses; pregnancy or lactation and use of medications (e.g. painkillers or antihistamine). The protocol (N‐20190062) was approved by the Regional Ethics Committee and all participants signed an informed consent form in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration, and it is registered on clinicaltrial.gov (NCT04197440). The study (randomized, single‐blinded, controlled trial) included two sessions over 7 days. During the first session of the experiment, two areas (4 × 4 cm, 4 cm apart) on both forearms of each subject were selected. The four areas were treated, by standard allergy skin prick test (SPT) lancets (Allergopharma, Germany) with three BAM8‐22 solutions with different concentrations (0.5, 1 and 2 mg/ml) and vehicle (sterile water). After 7 days, in the second session, the three areas were treated with BAM8‐22 solution (1 mg/ml) by SPT lancets, respectively 1, 5 and 25 pricks, evenly distributed to each area. In the fourth area, heat‐inactivated cowhage spicules soaked in BAM8‐22 solution (1 mg/ml) were applied.

In both sessions, after each application, itch and pain were monitored for 9 min through a VAS scale, followed by the measurement of neurogenic flare response (by superficial blood perfusion) and quantitative sensory tests.

2.2. Administration of BAM8‐22

BAM8‐22 (Sigma‐Aldrich, SML0729) was dissolved in distilled sterile water (following manufacturer's instructions) and three solutions were obtained (concentration: 0.5, 1 and 2 mg/ml).

First session: Standard allergy skin prick test (SPT) lancets were used to deliver the three concentrations of BAM8‐22 and vehicle. Twenty microlitres of solution was placed in the center of the selected area and one prick was performed by applying 120 g of pressure.

Second session: BAM solution (1 mg/ml) was applied using SPT lancet and 1, 5 and 25 pricks were performed in three areas. In the fourth area, heat‐inactivated cowhage spicules soaked in BAM8‐22 solution (1 mg/ml) were applied.

The application of 1 mg/ml in the first session and one prick in the second session are identical.

2.3. Cowhage preparation and application

Cowhage spicules were inactivated by autoclaving (120°C for 50 min) and then soaked overnight in BAM8‐22 solution (1 mg/ml). Previously, the inactivation procedure was tested on a small sample of subjects, confirming that the inactivated spicules did not induce itch or pain upon application (data not shown). About 25–30 spicules were gently rubbed in the middle of the skin area (∅ 1 cm) and, 9 min after the application, they were removed by tape. 12

2.4. Assessment of itch and pain intensities

After each BAM8‐22 provocation, the durations and intensities of itch and pain were assessed by a modified Visual Analogue Scale (VAS, eVAS Software, Aalborg University, Denmark) installed on a Samsung Note 10.1 Tablet (Samsung, Seoul, South Korea). Subjects were instructed to rate on the two bars (one for itch and one for pain) itch and pain intensities from 0 to 10 continuously throughout the 9‐min sampling (conducted at 0.2 Hz). 0 indicated “no itch/pain” and 10 indicated “worst imaginable itch/pain”. The subjects can only see the outer labels (0–10), whilst the change in sensitivity is related to a difference in the color gradient (from white to black) on the scale. After the recording, the data are automatically transformed to values from 0 to 100 by the application used. Temporal itch and pain intensity profiles were generated from the VAS/time data. The peak of itch and pain intensity was extracted, and the area under the curve (AUC) was calculated using the trapezoidal method.

2.5. Neurogenic inflammation reactivity

Neurogenic inflammation reactivity, assessed by superficial blood perfusion (SBP), was measured using Full‐Field Laser Perfusion Imaging (‘FLPI’, Axminster, Devon, UK). One picture was taken with the sensor of the device placed approximately 25 cm above the induction area (display rate: 5 Hz, exposure time: 8.3 ms and gain: 160 units). The FLPI imaging data were analyzed using MoorFLPI Review V4.0 proprietary software. It used a region of interest (ROI) approach. The ROI corresponded to the defined area of 4 × 4 cm. From each ROI, mean and peak perfusion values were extracted.

2.6. Measurement of mechanically evoked itch

Mechanically evoked itch was assessed using three von Frey filaments (North Coast Medical, Gilroy, CA, USA): 9.8, 13.7, and 19.6 mN (size 4.08, 4.16, and 4.31, respectively). Von Frey filaments are mostly used to assess hyperkinesis (enhanced itch to normally itch‐provoking stimuli). 20 Subjects were instructed to rate the itch intensity elicited by stimulations of each filament on a numerical rating scale (NRS) from 0 to 10 (0 = “no itch”; 10 = “worst imaginable itch”). A stimulation was composed of three pricks in short succession (approximately 1 s in between), and it was repeated three times for each filament. To perform statistical analysis, a total average was calculated.

2.7. Measurement of mechanical pinprick pain thresholds (MPT) and mechanical pinprick pain sensitivity (MPS)

To measure the MPT, a pinprick set (MRC Systems GmbH, Germany) was used. The set consists of seven needles each with a diameter of 0.6 mm and different force applications: 8, 16, 32, 64, 128, 256, and 512 mN. Starting with the lightest, five ascending/descending series of stimuli (rate of each stimulus: 2 s on and 2 s off) were performed and the subjects were instructed to report when the perception of sharpness or pain was first sensed. The final threshold was calculated as the geometric mean of the five thresholds obtained.

To assess the MPS, the same pinprick set was used. Each stimulator was applied, from the lightest in ascending order, and for each stimulus, participants reported a pain rating on an NRS from 0 to 10 (0 = “no pain”; 10 = “worst imaginable pain”). This procedure was performed twice. The results were calculated as the arithmetic mean of the reported pain ratings.

2.8. Thermal sensitivity

A thermal stimulator Medoc Pathway (Medoc Ltd, Ramat Yishay, Israel) was used to measure cold detection threshold (CDT), warm detection threshold (WDT), cold pain threshold (CPT), heat pain threshold (HPT), and suprathreshold heat sensitivity (STHS). The thermal stimulator (3 × 3 cm) was placed on the selected area and a starting temperature of 32°C was set. An ascending or descending ramp stimulus of 1°C/s was delivered until the subjects identified the specific threshold by pushing a stop button that terminated the measurement and returned the temperature to baseline at a rate of 5°C/s. For the CDT, the subjects pressed the button as soon as cold or a decrease in temperature was felt. For the WDT, the subjects pushed the button as soon as warm or an increase in temperature was perceived. For CPT and HPT, the subjects were instructed to press the button as soon as the cold (for CPT) or warm (for HPT) ramp stimulus gave rise to a painful sensation. Each simulation was repeated three times and the results were calculated as the arithmetic mean of the thresholds.

For the STHS, the subjects reported a pain rating (from 0 to 10) to two suprathreshold heat pain stimuli. A stimulus is composed of an ascending ramp (from 32 to 50°C, 5°C/s), a plateau of 3 s at 50°C and a descending ramp (from 50 to 32°C, 5°C/s). To perform statistical analysis, the arithmetic means of the two measurements were calculated.

2.9. Statistical analysis

Data handling and calculation of descriptive statistics were performed in Excel (Windows, Redmond, WA, USA), statistical testing was performed in SPSS software (v26, IBM Corporation, NY, USA), whereas the graph plotting was conducted in GraphPad Prism 6 (GraphPad Software Inc., CA, USA). After a Shapiro–Wilk normality test, a repeated measure analysis of variance (RM‐ANOVAs), followed by Sidak post hoc test was used to analyze the data. p‐Value ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant. RM‐ANOVAs were constructed using the following factors: condition (BAM8‐22 2, 1, 0.5 mg/ml, 1, 5, 25 pricks, inactivated spicules, and vehicle) and time (every 30 s of 9 min of VAS only for itch/pain temporal profile analysis). Moreover, a Pearson product–moment correlation was run to determine if there was a correlation between BAM8‐22 concentration, from 0 (vehicle) to 2 mg/ml, and itch induced.

3. RESULTS

Twenty‐two participants took part in this study and all completed the experimental procedure without any adverse reactions. All the eight conditions were compared: 0.5, 1, 2 mg/ml, 1, 5 and 25 pricks, inactivated spicules soaked in BAM8‐22 solution, and 1 vehicle SPT. As expected, in all the tests performed, the results of the two conditions 1 mg/ml and 1 prick were not statistically different. In the “Results” session, the conditions were renamed, in order, as follows: 0.5, 1, 2 mg/ml, 1P, 5P, 25P, spicules, and vehicle.

3.1. Itch intensity induced by BAM8‐22

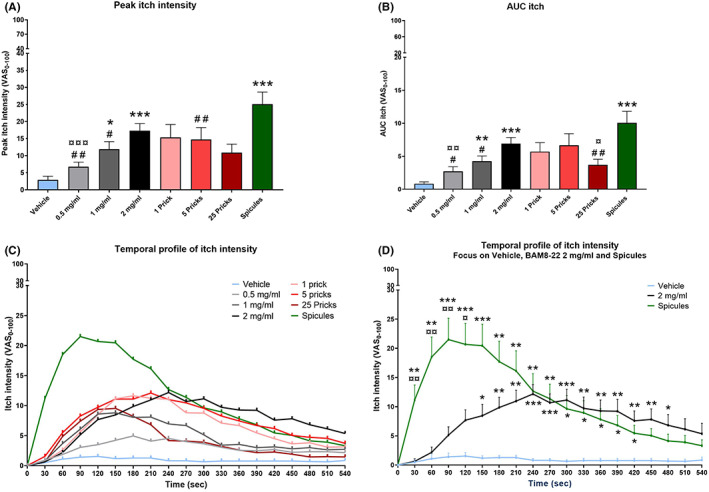

The itch profiles induced by BAM8‐22 are shown in Figure 1, and the values are reported in Table 1. BAM8‐22 induced significantly more itch compared to vehicle both for peak of itch intensity (F 4,90 = 9.20; Figure 1A) and area under the curve (AUC; F 4,82 = 9.19; Figure 1B). Concerning peak itch intensity (Figure 1A), 1, 2 mg/ml and spicules resulted in statistical higher than vehicle (Sidak, vehicle vs. 1 mg/ml p < 0.05, vs. 2 mg/ml p < 0.001, vs. spicules p < 0.001). Moreover, the peak intensity evoked by spicules was higher than the peak intensity of 0.5, 1 mg/ml, and 5P (Sidak, spicules vs. 0.5 mg/ml p < 0.01, vs. 1 mg/ml p < 0.05, vs. 5P p < 0.01). A significant difference was detected between 2 and 0.5 mg/ml (Sidak, p < 0.001). For AUC, 1, 2 mg/ml and spicules resulted in statistically higher intensities than vehicle (Sidak, vehicle vs. 1 mg/ml p < 0.01, vs. 2 mg/ml p < 0.001, vs. spicules p < 0.001). AUC after spicules, stimulation was higher than 0.5, 1 mg/ml and 25P (Sidak, spicules vs. 0.5 mg/ml p < 0.05, vs. 1 mg/ml p < 0.05, vs. 25P p < 0.01), whereas AUC of 2 mg/ml was higher than 0.5 mg/ml and 25P (Sidak, 2 mg/ml vs. 0.05 mg/ml p < 0.01, vs. 25P p < 0.05). In addition, the correlations between BAM8‐22 concentration (0‐vehicle, 0.5, 1 and 2 mg/ml) and itch induced were calculated for peak and AUC. In both cases, there was a significant, positive correlation between concentration and itch intensity (peak: r = 0.558, p < 0.001; AUC r = 0.559, p < 0.001).

FIGURE 1.

Itch induced by BAM8‐22. (A) Peak itch intensity. (B) AUC itch. (C) Temporal profile of itch intensity. (D) Temporal profile of itch intensity, focused on BAM8‐22 2 mg/ml, inactivated spicules and vehicle. Significance indicators: any condition vs. vehicle (*) p < 0.05, (**) p < 0.01, (***) p < 0.001; any condition vs. BAM8‐22 coated spicules (#) p < 0.05, (##) p < 0.01; any condition vs. BAM8‐22 2 mg/ml (¤) p < 0.05, (¤¤) p < 0.01, (¤¤¤) p < 0.001. Vehicle = light blue, BAM8‐22 0.5 mg/ml = light grey, BAM8‐22 1 mg/ml = dark grey, BAM8‐22 2 mg/ml = black, 1 prick = pink, 5 pricks = red, 25 pricks = dark red and inactivated spicules = green. Itch, defined as an unpleasant somatosensation that evokes the desire to scratch, 1 could be considered a minor annoyance often associated with harmless episodic pruritus2,3 caused by minor injuries such as mosquito bites. In its acute form, itch simply prompts a relatively short‐lived scratch response in the affected areas; however, in the last decades, itch started to be considered a disease, especially when it persists for more than 6 weeks becoming chronic. 4 Chronic itch occurs under conditions such as psoriasis, prurigo nodularis, uremic pruritus, drug‐induced itching or atopic dermatitis (AD). 4 Itch interferes with functions such as damag pain were assessed by a modified Visual Analogue Scale (VAS, eVAS Software, Aalborg University, Denmark) installed on a Samsung Note 10.1 Tablet (Samsung, Seoul, South Korea). Subjects were instructed to rate on the two bars (one for itch and one for pain) itch and pain intensities from 0 to 10 continuously throughout the 9‐min sampling (conducte

TABLE 1.

Peak and AUC of itch and pain

| Peak itch (VAS0–100) | AUC itch (VAS0–100) | Peak pain (VAS0–100) | AUC pain (VAS0–100) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vehicle | 2.91 ± 5.05 | 0.83 ± 1.31 | 1.68 ± 3.86 | 0.71 ± 1.85 |

| 0.5 mg/ml | 6.82 ± 6.14 | 2.71 ± 3.27 | 3.09 ± 6.46 | 1.21 ± 2.20 |

| 1 mg/ml | 11.91 ± 10.42 | 4.24 ± 3.71 | 1.18 ± 2.06 | 0.48 ± 1.17 |

| 2 mg/ml | 17.36 ± 9.70 | 6.91 ± 4.34 | 2.59 ± 4.45 | 1.11 ± 1.95 |

| 1 Prick | 15.36 ± 17.73 | 5.70 ± 6.36 | 1.14 ± 2.90 | 0.66 ± 1.64 |

| 5 Pricks | 14.77 ± 16.28 | 6.66 ± 8.26 | 3.45 ± 6.77 | 1.80 ± 3.92 |

| 25 Pricks | 10.91 ± 11.69 | 3.68 ± 4.06 | 5.73 ± 7.26 | 1.99 ± 3.30 |

| Spicules | 25.09 ± 16.62 | 10.07 ± 8.17 | 3.54 ± 5.22 | 1.33 ± 2.41 |

Note: Means ± SDs of peak and AUC (0–10 scale) of itch and pain induced by BAM8‐22.

The graph of the temporal profile of itch intensity (Figure 1C) showed that spicules induced a more intense itch intensity compared to the other conditions and peaked around 90 s, whereas itch induced by BAM8‐22 2 mg/ml lasted for a longer duration and peaked around 240 s. Only spicules and 2 mg/ml showed statistical differences with vehicle (time × condition: F 7,142 = 5.33) and, focusing on these three conditions (Figure 1D), itch induced by spicules was higher than vehicle from 30 to 420 s (Sidak, 30 and 60 s p < 0.01, from 90 to 150 s p < 0.001, from 180 to 270 s p < 0.01, from 300 to 420 s p < 0.05), whereas 2 mg/ml was higher than vehicle from 150 to 480 s (Sidak, 150 s p < 0.05, 180 and 210 s p < 0.01, from 240 to 300 s p < 0.001, from 330 to 450 s p < 0.01, 480 s p < 0.05). Differences between spicules and 2 mg/ml were detected from 30 to 90 s (p < 0.01) and at 120 s (p < 0.05).

3.2. Pain intensity induced by BAM8‐22

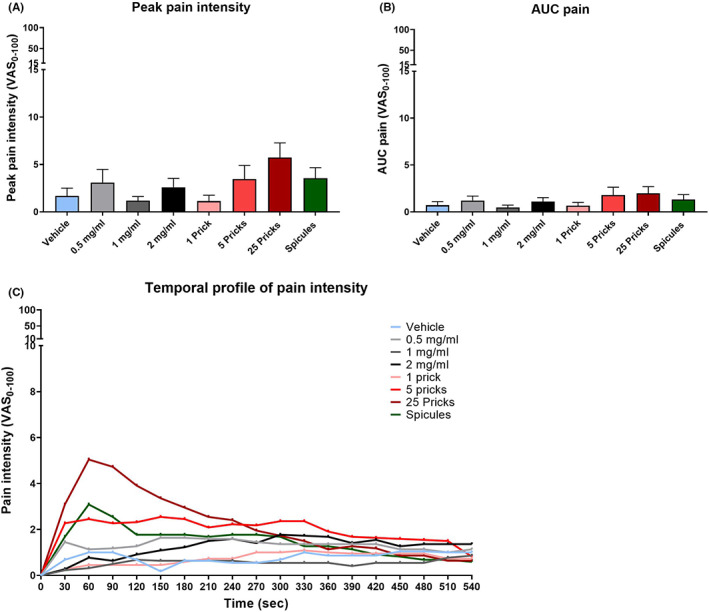

The pain intensities induced during the applications of BAM8‐22 are shown in Figure 2 and listed in Table 1. After an RM‐ANOVA, the main effect was found by analysing the peak pain intensities (F 4,75 = 3.49, p < 0.05). After a post hoc test, no differences between groups were detected (Figure 2A). For AUC, there were no statistical differences between groups (p = 0.113, Figure 2B). A visual inspection of the temporal profile of pain (Figure 2C) indicated that the pain intensity in the 25P area was higher than in the other areas and peaked around 60 s.

FIGURE 2.

Pain induced by BAM8‐22. (A) Peak pain intensity. (B) AUC pain. (C) Temporal profile of pain intensity. Vehicle = light blue, BAM8‐22 0.5 mg/ml = light grey, BAM8‐22 1 mg/ml = dark grey, BAM8‐22 2 mg/ml = black, 1 prick = pink, 5 pricks = red, 25 pricks = dark red and inactivated spicules = green

3.3. Neurogenic inflammation reactivity induced by BAM8‐22

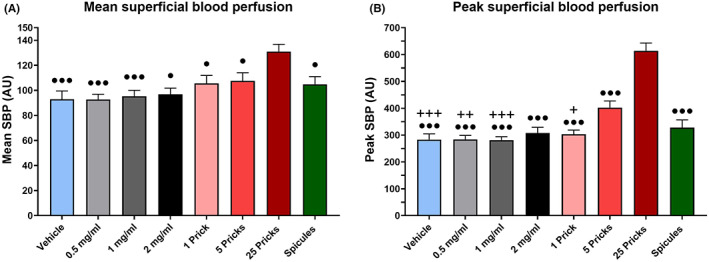

Superficial blood perfusion (SBP) was used to assess neurogenic inflammation reactivity (Figure 3, Table 2). The mean SBP was higher for 25P than the other activations (F 5,98 = 7.55; Sidak, 25P vs. vehicle, 0.5, 1 mg/ml p < 0.001; vs. 2 mg/ml, 1P, 5P and spicules p < 0.05; Figure 3A). This result was confirmed by the analysis of the peak SBP (Figure 3B). All the other areas had a peak lower than the 25P (F 4,77 = 34.85; Sidak, p < 0.001). Moreover, the peak of 5P was higher than other conditions, in particular vehicle, 0.5, 1 mg/ml and 1P (Sidak, 5P vs. vehicle and 1 mg/ml p < 0.001, vs. 0.5 mg/ml p < 0.01, vs. 1P p < 0.05).

FIGURE 3.

Superficial blood perfusion and mechanical sensitivity. (A) Mean SBP. (B) Peak SBP. Significance indicators: any condition vs. 25 pricks (•) p < 0.05, (•••) p < 0.001; any condition vs. 5 pricks (+) p < 0.05, (++) p < 0.01, (+++) p < 0.001. Vehicle = light blue, BAM8‐22 0.5 mg/ml = light grey, BAM8‐22 1 mg/ml = dark grey, BAM8‐22 2 mg/ml = black, 1 prick = pink, 5 pricks = red, 25 pricks = dark red and inactivated spicules = green. Values are presented as mean + SEM.

TABLE 2.

Superficial blood perfusion, mechanical and thermal assessments

| Mean SBP (AU) | Peak SBP (AU) | MEI (NRS0–10) | MPT (mN) | MPS (NRS0–10) | CDT (°C) | CPT (°C) | WDT (°C) | HPT (°C) | STHS (NRS0–10) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vehicle | 92.90 ± 31.12 | 283.23 ± 101.18 | 0.70 ± 0.80 | 206.11 ± 231.63 | 1.17 ± 1.13 | 26.95 ± 2.99 | 12.61 ± 7.94 | 35.52 ± 1.67 | 43.63 ± 3.59 | 8.16 ± 1.71 |

| 0.5 mg/ml | 92.70 ± 19.65 | 284.18 ± 69.03 | 0.83 ± 0.94 | 220.59 ± 274.64 | 1.08 ± 0.94 | 27.31 ± 2.86 | 12.73 ± 7.31 | 35.87 ± 1.77 | 43.44 ± 4.07 | 8.11 ± 1.75 |

| 1 mg/ml | 95.33 ± 21.99 | 281.36 ± 59.52 | 0.77 ± 0.56 | 176.90 ± 243.67 | 0.95 ± 0.74 | 27.89 ± 1.82 | 12.53 ± 7.53 | 35.68 ± 1.64 | 43.66 ± 3.69 | 8.03 ± 1.73 |

| 2 mg/ml | 96.90 ± 22.94 | 307.41 ± 102.33 | 1.12 ± 1.04 | 205.91 ± 241.80 | 1.05 ± 1.01 | 27.88 ± 2.54 | 11.75 ± 7.90 | 35.38 ± 2.09 | 43.37 ± 3.74 | 7.95 ± 1.77 |

| 1 Prick | 105.56 ± 29.67 | 303.32 ± 72.50 | 0.78 ± 0.75 | 228.60 ± 235.05 | 0.87 ± 0.80 | 27.63 ± 1.92 | 12.04 ± 7.89 | 35.70 ± 1.86 | 44.28 ± 3.05 | 7.90 ± 1.80 |

| 5 Pricks | 107.58 ± 30.43 | 402.27 ± 116.07 | 0.71 ± 0.85 | 249.64 ± 295.80 | 0.91 ± 0.91 | 26.81 ± 3.14 | 12.54 ± 8.39 | 35.73 ± 2.50 | 44.04 ± 3.49 | 8.09 ± 1.85 |

| 25 Pricks | 130.93 ± 27.36 | 613.77 ± 136.93 | 0.64 ± 0.66 | 230.04 ± 251.44 | 0.82 ± 0.77 | 27.46 ± 2.36 | 12.09 ± 8.22 | 35.91 ± 2.47 | 44.13 ± 3.25 | 8.08 ± 1.83 |

| Spicules | 104.85 ± 28.69 | 327.77 ± 135.19 | 1.17 ± 1.04 | 207.75 ± 265.10 | 1.06 ± 1.09 | 27.85 ± 2.07 | 13.42 ± 8.19 | 36.07 ± 2.10 | 43.92 ± 3.62 | 8.09 ± 1.71 |

Note: Means ± SDs of superficial blood perfusion, mechanical and thermal sensitivity tests.

Abbreviations: CDT, cold detection threshold; CPT, cold pain threshold; HPT, heat pain threshold; Mean and peak SBP, superficial blood perfusion; MEI, mechanically evoked itch; MPS, mechanical pain sensitivity; MPT, mechanical pain threshold; STHS, suprathreshold heat sensitivity; WDT, warmth detection threshold.

3.4. Mechanical sensitivity

The results of mechanical sensitivity, mechanically evoked itch (MEI), mechanical pain threshold (MPT) and mechanical pain sensitivity (MPS) are shown in Table 2.

In mechanically evoked itch, it was detected a difference between spicules and 25P. In particular, the itch evoked in the spicules area was higher than the one evoked in the 25P area (F 5,106 = 2.54; Sidak, p < 0.05).

In mechanical pain threshold and mechanical pain sensitivity, no differences between groups were detected (MPT: F 3,65 = 0.65, p = 0.591; MPS: F 3,64 = 1.85, p = 0.145).

3.5. Thermal sensitivity

BAM8‐22 did not induce any changes in thermal sensitivity (Table 2). There were no statistical differences in thermal detection threshold, and this is true for both cold and warm (CDT: F 7,147 = 1.33, p = 0.241; WDT: F 3,71 = 0.96, p = 0.422). The same result was obtained by the analysis of the pain detection thresholds (CPT: F 7,147 = 0.37, p = 0.917; HPT: F 7,147 = 0.99, p = 0.441). Moreover, neither in STHS any difference was detected (F 3,72 = 0.48, p = 0.723).

4. DISCUSSION

BAM8‐22 provoked itch when applied with one lancet prick at concentrations of 1 and 2 mg/ml and when applied with heat‐inactivated cowhage spicules at a concentration of 1 mg/ml. BAM8‐22 did not induce neurogenic inflammation or changes in mechanical and thermal sensitivities. The BAM8‐22 coated, inactivated, cowhage spicules caused the highest itch intensity suggesting this as a new non‐histaminergic human experimental itch model.

4.1. Itch and pain induced by BAM8‐22

Bovine adrenal medulla (BAM)8–22 is an endogenous peptide derived from proenkephalin A via proteolytic cleavage. BAM8‐22 activates MrgprA3 and MrgprX1 (also known as MrgprC11) and induces itch via Gαq/11 pathway. 19 Additionally, activation of Mas‐related G protein‐coupled receptors by BAM8‐22 induces the activation of TRPA1 receptors. 15

The results of the present study confirmed the role of BAM8‐22 as a pruritogen in humans. In fact, BAM8‐22 induced a significant itch sensation compared to the vehicle, when it was applied by a single SPT at concentrations of 1 and 2 mg/ml and when applied by inactivated cowhage spicules in concentrations of 1 mg/ml. When employing SPT, BAM8‐22 is most likely applied at the dermoepidermal junction at depths of approximately 0.5–1.5 mm, 21 , 22 whereas the application by spicules most likely only activates the keratinous layer of the skin (0.05–0.15 mm). 23 , 24 In mice, itch is mostly transmitted by a subpopulation of peptidergic neurons expressing MrgprA3 receptors on their surface and by a small subgroup of non‐peptidergic neurons expressing MrgprD. 25 It has been demonstrated in mice that neurons expressing MrgprD innervate the very superficial stratum granulosum, whereas peptidergic neurons innervate the deeper located stratum spinosum. 25 , 26 The results seem to confirm that, also in humans, the fibers transmitting BAM8‐22‐induced itch innervate both the most superficial layer of the skin (reached by spicules) and the deeper ones (reached by SPT). Moreover, the itch intensity has previously been found to be positively correlated with the concentration of the BAM8‐22 solutions, 17 although the concentration required to saturate skin receptors to obtain the highest itch intensity remains unknown. The baseline concentration of BAM8‐22 in human skin is unknown, whereas the expression of proenkephalin A (BAM8‐22 precursor) is observed in fibroblasts and keratinocytes which are particularly relevant in pathological conditions, such as psoriasis. 27 Proenkephalin A has been found to be upregulated or altered in fibroblasts and keratinocytes, and therefore could be a contributing factor to chronic itch. 27 The higher itch intensity induced by spicule versus itch induced by SPT could be explained by the fact that the application of spicules activated a bigger area (evoking spatial integration) than a single prick, allowing the substance to reach more receptors. To test this theory, in the present study, the BAM8‐22 solution was applied by SPT with different numbers of pricks. The area covered by 25 pricks approximately resembles the area stimulated by spicules, but the 25 pricks caused significantly lower AUC suggesting that the spatial summation was not prominent for the multiple pricks, although spatial summation for itch has previously been suggested. 23 The pain sensation associated with the 25 pricks could possibly mask the itch response; it was proposed that, in healthy subjects, pain inhibits itch and itch dysesthesias 28 , 29 , 30 by the activity of the spinal cord Bhlbb5 interneurons. 31

4.2. Neurogenic inflammation

In the present experiment, superficial blood perfusion was assessed by FLPI, a technique that illuminates a skin area by using a laser light pattern in the wavelength of around 750 nm (within the reflectance spectrum of hemoglobin 240–242). 32 The speckle pattern is the contrast laser pattern produced by the reflection of the laser light from the investigated surface. An increased SBP exhibits a lowered contrast. 33

The superficial blood perfusion after 25 skin pricks was higher in mean and peak than after all the other conditions. Moreover, also 5 pricks induced a higher peak SBP than the vehicle, 0.5, 1 mg/ml and 1 prick. The increased SBP was probably due to the delivery method that caused microtrauma to the skin. The absence of neurogenic inflammation in all the other areas is indirect evidence of non‐histaminergic itch induced by BAM8‐22 as seen in other studies in which non‐histaminergic itch models do not provoke SBP responses 32 in contrast to histamine activation of CMi‐fibers. 34 As such the present data confirmed that BAM8‐22 induced itch by histamine‐independent pathways. 17

4.3. Mechanical and thermal sensitivity assessments

Mechanical and thermal sensitivities were not affected by BAM8‐22. Regarding mechanical sensitivity, this seems to indicate that the mechanoreceptors in the skin are neither inhibited nor sensitized by BAM8‐22. Von Frey filaments of a given intensity and pinprick pain stimulation can stimulate different groups of sensory receptors and afferent fibers and in particular, C‐, Aβ‐ and Aδ‐fibers. 35 The lack of thermal sensitivity changes confirmed previous studies. 36

5. LIMITATIONS

One limitation of the spicules application is to ensure the exact number of spicules is introduced in each experiment, although care is taken to control the number. A second limitation, still related to the challenge of cowhage application, is that the comparison between the 1 prick condition and a single spicule application soaked with BAM8‐22 is missing in the present study. Despite this drawback, cowhage spicules seem to be the most effective method for non‐histaminergic itch induction with BAM8‐22. Itch induced by multiple skin pricks (lancets) seems to be inhibited by the pain induced by this delivery method and hence is a confounding factor. In this study, the arterial blood pressure was not measured, and we cannot rule out the lack of involvement of the sympathetic system in blood perfusion. Lastly, baseline measurements are missing, although, the vehicle areas were randomized across application areas and left and right forearms.

6. CONCLUSIONS

BAM8‐22 is an endogenous peptide that activates Mrgprs and thereby induces non‐histaminergic itch. Different concentrations (from 0.5 to 2 mg/ml) and different delivery methods (single skin prick tests with 1, 5, or 25 pricks and heat‐inactivated cowhage spicules) were tested in the present study. BAM8‐22 at the concentration of 1 and 2 mg/ml and inactivated spicules induced a moderate itch intensity without any changes in superficial blood perfusion and mechanical and thermal sensitivities. Inactivated spicules soaked in BAM8‐22 solution resulted in the best experimental delivery method since induced the highest itch intensity.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

LAN, SLV and GEA designed the study. GEA collected and analyzed the data and drafted the manuscript. All authors discussed the results and commented on and approved the manuscript. All authors agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None to declare.

STATEMENT OF EXCLUSIVITY

The data included in the present article have not been published elsewhere.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

None.

Aliotta GE, Lo Vecchio S, Elberling J, Arendt‐Nielsen L. Evaluation of itch and pain induced by bovine adrenal medulla (BAM)8–22, a new human model of non‐histaminergic itch. Exp Dermatol. 2022;31:1402‐1410. doi: 10.1111/exd.14611

Funding information

Center for Neuroplasticity and Pain (CNAP), Aalborg University. The Center for Neuroplasticity and Pain (CNAP) is supported by the Danish National Research Foundation (DNRF121).

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- 1. Darsow U, Ring J, Scharein E, Bromm B. Correlations between histamine‐induced wheal, flare and itch. Arch Dermatol Res. 1996;288:436‐441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Andersen HH, Elberling J, Arendt‐Nielsen L. Human surrogate models of histaminergic and non‐histaminergic itch. Acta Derm Venereol. 2015;95:771‐779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Frese T, Herrmann K, Sandholzer H. Pruritus as reason for encounter in general practice. J Clin Med Res. 2011;3:223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Andersen HH, Arendt‐Nielsen L, Gazerani P. Glial cells are involved in itch processing. Acta Derm Venereol. 2016;96:723‐729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Matterne U, Apfelbacher CJ, Loerbroks A, et al. Prevalence, correlates and characteristics of chronic pruritus: a population‐based cross‐sectional study. Acta Derm Venereol. 2011;91:674‐679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Anand P. Capsaicin and menthol in the treatment of itch and pain: recently cloned receptors provide the key. Gut. 2003;52:1233‐1235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Patel T, Yosipovitch G. Therapy of pruritus. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2010;11:1673‐1682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bordon Y. JAK in the itch. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2017;16:753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Imamachi N, Park GH, Lee H, et al. TRPV1‐expressing primary afferents generate behavioral responses to pruritogens via multiple mechanisms. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(27):11330‐11335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Shim W‐S, Tak M‐H, Lee M‐H, et al. TRPV1 mediates histamine‐induced itching via the activation of phospholipase A2 and 12‐lipoxygenase. J Neurosci. 2007;27:2331‐2337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Akiyama T, Tominaga M, Davoodi A, et al. Cross‐sensitization of histamine‐independent itch in mouse primary sensory neurons. Neuroscience. 2012;226:305‐312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Andersen HH, Sørensen A‐KR, Nielsen GAR, et al. A test–retest reliability study of human experimental models of histaminergic and non‐histaminergic itch. Acta Derm Venereol. 2017;97:198‐207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Højland CR, Andersen HH, Poulsen JN, Arendt‐Nielsen L, Gazerani P. A human surrogate model of itch utilizing the TRPA1 agonist trans‐cinnamaldehyde. Acta Derm Venereol. 2015;95:798‐803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lee SE, Jeong SK, Lee SH. Protease and protease‐activated receptor‐2 signaling in the pathogenesis of atopic dermatitis. Yonsei Med J. 2010;51:808‐822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wilson SR, Gerhold KA, Bifolck‐Fisher A, et al. TRPA1 is required for histamine‐independent, mas‐related G protein–coupled receptor–mediated itch. Nat Neurosci. 2011;14:595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Christensen JD, Lo Vecchio S, Elberling J, Arendt‐Nielsen L, Andersen H. Assessing punctate Administration of Beta‐alanine as a potential human model of non‐histaminergic itch. Acta Derm Venereol. 2019;99:222‐223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sikand P, Dong X, LaMotte RH. BAM8–22 peptide produces itch and nociceptive sensations in humans independent of histamine release. J Neurosci. 2011;31:7563‐7567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sanjel B, Maeng H‐J, Shim W‐S. BAM8‐22 and its receptor MRGPRX1 may attribute to cholestatic pruritus. Sci Rep. 2019;9:10888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Han S‐K, Dong X, Hwang J‐I, Zylka MJ, Anderson DJ, Simon MI. Orphan G protein‐coupled receptors MrgA1 and MrgC11 are distinctively activated by RF‐amide‐related peptides through the Gαq/11 pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:14740‐14745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Andersen HH, Akiyama T, Nattkemper LA, et al. Alloknesis and hyperknesis—mechanisms, assessment methodology, and clinical implications of itch sensitization. Pain. 2018;159:1185‐1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gibson RA, Robertson J, Mistry H, et al. A randomised trial evaluating the effects of the TRPV1 antagonist SB705498 on pruritus induced by histamine, and cowhage challenge in healthy volunteers. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e100610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gazerani P, Pedersen NS, Drewes AM, Arendt‐Nielsen L. Botulinum toxin type a reduces histamine‐induced itch and vasomotor responses in human skin. Br J Dermatol. 2009;161:737‐745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. LaMotte RH, Shimada SG, Green BG, Zelterman D. Pruritic and nociceptive sensations and dysesthesias from a spicule of cowhage. J Neurophysiol. 2009;101:1430‐1443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sikand P, Shimada SG, Green BG, LaMotte RH. Similar itch and nociceptive sensations evoked by punctate cutaneous application of capsaicin, histamine and cowhage. Pain. 2009;144:66‐75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Akiyama T, Carstens E. Neural processing of itch. Neuroscience. 2013;250:697‐714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zylka MJ, Rice FL, Anderson DJ. Topographically distinct epidermal nociceptive circuits revealed by axonal tracers targeted to Mrgprd. Neuron. 2005;45:17‐25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Slominski AT, Zmijewski MA, Zbytek B, et al. Regulated proenkephalin expression in human skin and cultured skin cells. J Invest Dermatol. 2011;131:613‐622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Baron R, Schwarz K, Kleinert A, Schattschneider J, Wasner G. Histamine‐induced itch converts into pain in neuropathic hyperalgesia. Neuroreport. 2001;12:3475‐3478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Brull SJ, Atanassoff PG, Silverman DG, Zhang J, Lamotte RH. Attenuation of experimental pruritus and mechanically evoked dysesthesiae in an area of cutaneous allodynia. Somatosens Mot Res. 1999;16:299‐303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Andersen HH, Yosipovitch G, Arendt‐Nielsen L. Pain inhibits itch, but not in atopic dermatitis? Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2018;120:548‐549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Dhand A, Aminoff MJ. The neurology of itch. Brain. 2014;137:313‐322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Andersen, H. H. Studies on Itch and Sensitization for Itch in Humans ; 2017.

- 33. Eriksson S, Nilsson J, Sturesson C. Non‐invasive imaging of microcirculation: a technology review. Med Devices (Auckl). 2014;7:445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Schmelz M, Schmidt R, Bickel A, Handwerker HO, Torebjörk HE. Specific C‐receptors for itch in human skin. J Neurosci. 1997;17:8003‐8008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Owens DM, Lumpkin EA. Diversification and specialization of touch receptors in skin. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2014;4:a013656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. van Laarhoven AIM, Marker JB, Elberling J, Yosipovitch G, Arendt‐Nielsen L, Andersen HH. Itch sensitization? A systematic review of studies using quantitative sensory testing in patients with chronic itch. Pain. 2019;160:2661‐2678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.