Abstract

The gut-brain axis (GBA) is broadly accepted to describe the bidirectional circuit that links the gastrointestinal tract with the central nervous system (CNS). Interest in the GBA has grown dramatically over past two decades along with advances in our understanding of the importance of the axis in the pathophysiology of numerous common clinical disorders including mood disorders, neurodegenerative disease, diabetes mellitus, non-alcohol fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and enhanced abdominal pain (visceral hyperalgesia). Paralleling the growing interest in the GBA, there have been seminal developments in our understanding of how environmental factors such as psychological stress and other extrinsic factors alter gene expression, primarily via epigenomic regulatory mechanisms. This process has been driven by advances in next-generation multi-omics methods and bioinformatics. Recent reviews address various components of GBA, but the role of epigenomic regulatory pathways in chronic stress-associated visceral hyperalgesia in relevant regions of the GBA including the amygdala, spinal cord, primary afferent (nociceptive) neurons, and the intestinal barrier has not been addressed. Rapidly developing evidence suggests that intestinal epithelial barrier dysfunction and microbial dysbiosis play a potentially significant role in chronic stress-associated visceral hyperalgesia in nociceptive neurons innervating the lower intestine via downregulation in intestinal epithelial cell tight junction protein expression and increase in paracellular permeability. These observations support an important role for the regulatory epigenome in the development of future diagnostics and therapeutic interventions in clinical disorders affecting the GBA.

Keywords: Brain-gut axis, Chronic stress, Depression, Anxiety, Epigenomics, Visceral pain, HPA-axis, Irritable bowel syndrome, Intestinal barrier dysfunction, Glucocorticoid receptor

Introduction

The descriptor gut-brain-axis (GBA) dates to the nineteenth century based on observations that stressful situations were often associated with gastrointestinal symptoms, and provided the basis for our current understanding of the critical role that the GBA plays in homeostatic processes in health and disease (Miller 2018). Early studies using electron microscopy and morphological analysis demonstrated that the vagus nerve, which modulates parasympathetic function in the gastrointestinal tract, consisted mostly of afferents, emphasizing the importance of visceral feedback in the GBA (Hoffman and Schnitzlein 1961). With the emergence of functional brain imaging technologies in the 1980s, the bi-directionality of this axis became apparent. Research indicated that distension of the gut resulted in exaggerated activation of afferent pathways associated with pain registration (visceral hyperalgesia) and smooth muscle response in the common functional bowel disorder, irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) (Azpiroz et al. 2007).

Visceral pain signals are transmitted along A-δ and C nociceptive nerve fibers from the periphery to the central nervous system. The cell bodies of these fibers reside in the dorsal root ganglia (DRG) neurons located adjacent to the spinal column and the fibers synapse in the dorsal horn. Most peripheral nerve fibers will synapse in the Rexed laminae and then ascend in the contralateral spinothalamic tract before terminating in the ventral posterior nuclei and central nuclei of the thalamus. Pain pathways can demonstrate neuroplasticity. For example, the receptive fields of the thalamus may reorganize following injury. The primary and secondary somatosensory cortex receive the bulk of direct projections from the thalamus. The insula, orbitofrontal cortex, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, amygdala, and cingulate are additional regions important in pain processing. The rostral ventromedial medulla, the dorsolateral pontomesencephalic tegmentum, and the periaquaductal gray regions are important structures in the descending regulation of noxious stimuli at the dorsal horn. The neuromatrix theory of pain incorporates the concept of “gate” control of pain which focuses on pain regulation at the spinal cord with more recent evidence that expands the role of the cortex (Vermeulen et al. 2014; Bourne et al. 2014).

Excellent reviews have addressed the emerging role of the epigenomic regulatory pathways on specific components of the GBA including the microbiome (Louwies et al. 2020) and the potential for future development of novel therapeutics (Ligon et al. 2016). This review will emphasize the role of epigenomic regulatory mechanisms in the gut-brain axis in chronic stress-associated enhanced perception of abdominal pain. It is broadly accepted that common psychiatric disorders such as depression and anxiety are exacerbated by environmental stressors and frequently exhibit exaggerated perception of abdominal pain, a common presentation in IBS. Recent research implicates epigenomic regulatory pathways in this process. A growing body of research suggests that impaired intestinal barrier function and dysbiosis in the gut microbiome contribute to the pathophysiology of several common clinical disorders including inflammatory bowel disease, celiac disease, and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (Vancamelbeke and Vermeire 2017), diabetes mellitus, and graft vs host disease (Odenwald and Turner 2017) and IBS (Hanning et al. 2021). We will not discuss the important role of these pathways in regulating the immune system and the GBA response to chronic stress. This is a complex topic suitable for a separate review.

Application of contemporary bioinformatics and multi-omics methods has contributed immensely to advancing our current understanding of the GBA. Recent developments in computing power coupled with machine learning have proven key to understanding how the epigenome regulates gene expression. Thus, the automated processing of large-omic datasets has enabled rapid understanding of how environmental stimuli modify and perturb the human genome, previously considered a fixed template of double stranded helical DNA. Machine learning and deep learning involve machine-based training of algorithms that can be applied to complex problems in biomedical science that were previously considered intractable, resolving features that were not previously well understood using manual techniques. As artificial intelligence matures as a discipline, it is poised to revolutionize experimental biology and the practice of clinical medicine. In the Future Directions section of this review, we will discuss the implications of this sea change on our understanding of the epigenome in relationship to the GBA.

Epigenomic Regulatory Mechanisms: Background

Chronic stress-associated visceral hyperalgesia involves inducible and potentially reversible changes in the regulation of gene expression which are controlled by epigenomic mechanisms. Interest in the role of epigenomics and gene function has grown rapidly over the past two decades because of its significance in numerous important physiological and pathophysiological processes, including pain signaling (Gao et al. 2010; Szyf and Meaney 2008; Denk and McMahon 2012; Weaver et al. 2004; Hong et al. 2015). A molecular definition of the term “epigenetics” is “the study of mitotically and/or meiotically heritable changes in gene function that cannot be explained by changes in DNA sequence” (Martienssen et al. 1996). Contemporary usage is “epigenomics”, elements of which are shown by examples in Table 1, and include genome architecture organized by the chromatin landscape, functional RNA species including enhancer RNAs, long non-coding RNAs, microRNAs and other catalytic species, chromatin-histone dynamics, histone variants, post-translational modifications of amino acids on the amino-terminal tail of histones, and covalent modifications of DNA bases. DNA methylation describes the addition of a methyl group to the carbon-5 position of the cytosine pyrimidine ring and occurs predominantly in cytosine guanine dinucleotide-rich regions known as CpG islands found in the 5ʹ regulatory regions of most genes, except in human neurons where other mechanisms may also be involved (Guo et al. 2014; Kinde et al. 2015). At some promoters, CpG’s may act to fine-tune regulatory processes by directing gene expression patterns and cell fate (Saxonov et al. 2006; Deaton and Bird 2011).

Table 1.

Examples of elements that are considered part of the epigenome in this review From: The Role of Epigenomic Regulatory Pathways in the Gut-Brain Axis and Visceral Hyperalgesia

| Histone modifications | ||||

| Localization within the genome | Histone modifications (examples) | |||

| Transcription start site, gene promoter | H3K27ac | H3K4me3 | ENCODE Project Consortium (2012) | |

| Active enhancers | H3K27ac | H3K4me1 | ||

| Gene bodies of transcribed genes | H3K36me3 | |||

| Gene repression | H3K9me3 | H3K27me3 | ||

| Widespread gene activation | H3K9ac | |||

| DNA methylation | ||||

| CpG islands | Usually located 5’ to the transcription start site, except in brain | Bird (1986) | ||

| Three-dimensional genome architecture | ||||

| Component | Function (and structure) | |||

| Chromatin compartments A, B | A is euchromatin (predominately transcribed genes); B is heterochromatin (mostly repressed genes) | Dekker et al. (2017) | ||

| Topologically associating domains (TADs) | Fundamental, insulated compartments of gene expression, number about 4500 in humans | |||

| Lamina associating domains (LADs) | Heterochromatin compartments located at the nuclear periphery | |||

| Enhancers | Non-coding regulatory sequences that form chromatin loops with gene promoters and regulate gene expression | |||

| Super-enhancers | Long non-coding sequences that gather specific enhancers in response to extrinsic and intrinsic stimuli | Hnisz et al. (2013) | ||

| Dynamic, subnuclear condensates | ||||

| Transcriptional condensates | Formed by super-enhancers through liquid-liquid phase separation for amplification of gene expression | Shrinivas et al. (2019) | ||

| Nucleosomes | ||||

| The fundamental structural unit of DNA packaging consisting of 8 histone proteins that wrap around the genome. Allele-specific sliding of the nucleosome exposes gene promoters for transcription | Zhang et al. (2017) | |||

| Transcription factors | ||||

| Proteins that contain DNA-binding domains, activation domains, and intrinsically disordered domains. Act in gene transcription, the cell cycle, and other functions. About 2000 transcription factors have been identified in the human genome | Lambert et al. (2018) | |||

| Non-coding functional RNAs | ||||

| Enhancer RNAs | Short RNAs found at active enhancers—may help form chromatin loops that link enhancers with promoters | Sartorelli and Lauberth (2020) | ||

| Long non-coding RNAs | Catalytic RNAs that act within different subnuclear compartments similar to protein-coding genes | Volders et al. (2019) | ||

| microRNAs | Short RNAs that act in a generic manner through non-traditional base pairing with the 3’ end of genes | Saliminejad et al. (2019) | ||

| circRNAs | Short circular RNAs, also known as piRNAs, serve regulatory functions and may be involved in splicing | Wang et al. (2019) | ||

It is broadly accepted that epigenomic modifications include a role for long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) which may play an important role in environmentally induced changes in chromatin accessibility (Klemm et al. 2019; Han and Chang 2015). Histone modifications function, alone, or in combination, to help alter chromatin accessibility. Chromatin remodeling complexes, such as neuronal progenitor and neuronal barrier-to-autointegration factor (BAF) is a family of essential proteins including SMARCA4 and SMARCB1, which act to slide the nucleosome off of a gene promoter in an allele-specific manner (Barutcu et al. 2016).

In the context of histone modifications, acetylation and methylation have been well-studied, but these enzymatic systems remain poorly understood in the clinical setting (Morgan and Shilatifard 2020). The acetylation of lysine 27 and/or lysine 9 on histone 3 (H3K27ac or H3K9ac) mark active promoters, enhancers, and super-enhancers (Luo et al. 2020). Methylation of lysine 9 on histone 3 (H3K9me2/me3), catalyzed by methyltransferases such as G9a (Ehmt2), GLP (Ehmt1) and Suv39h1/Suv39h2, is often associated with silenced gene transcription and condensed chromatin (Fischle et al. 2005; Hyun et al. 2017). However, heterochromatin, which is contained in the so-called “B compartment” of nuclear chromatin, within lamina associating domains (LADs) located at the periphery of the nucleus, and surrounding the nucleolus, does contain several genes that are actively transcribed (Allshire and Madhani 2018). In contrast, methylation of lysine 4 on histone 3 (H3K4me3) is strongly enriched at promoter regions of active genes where chromatin exists in an open conformation (Ruthenburg et al. 2007; Santos-Rosa et al. 2002).

The Central Nervous System (CNS) Substrate for Glucocorticoid Receptor Effects

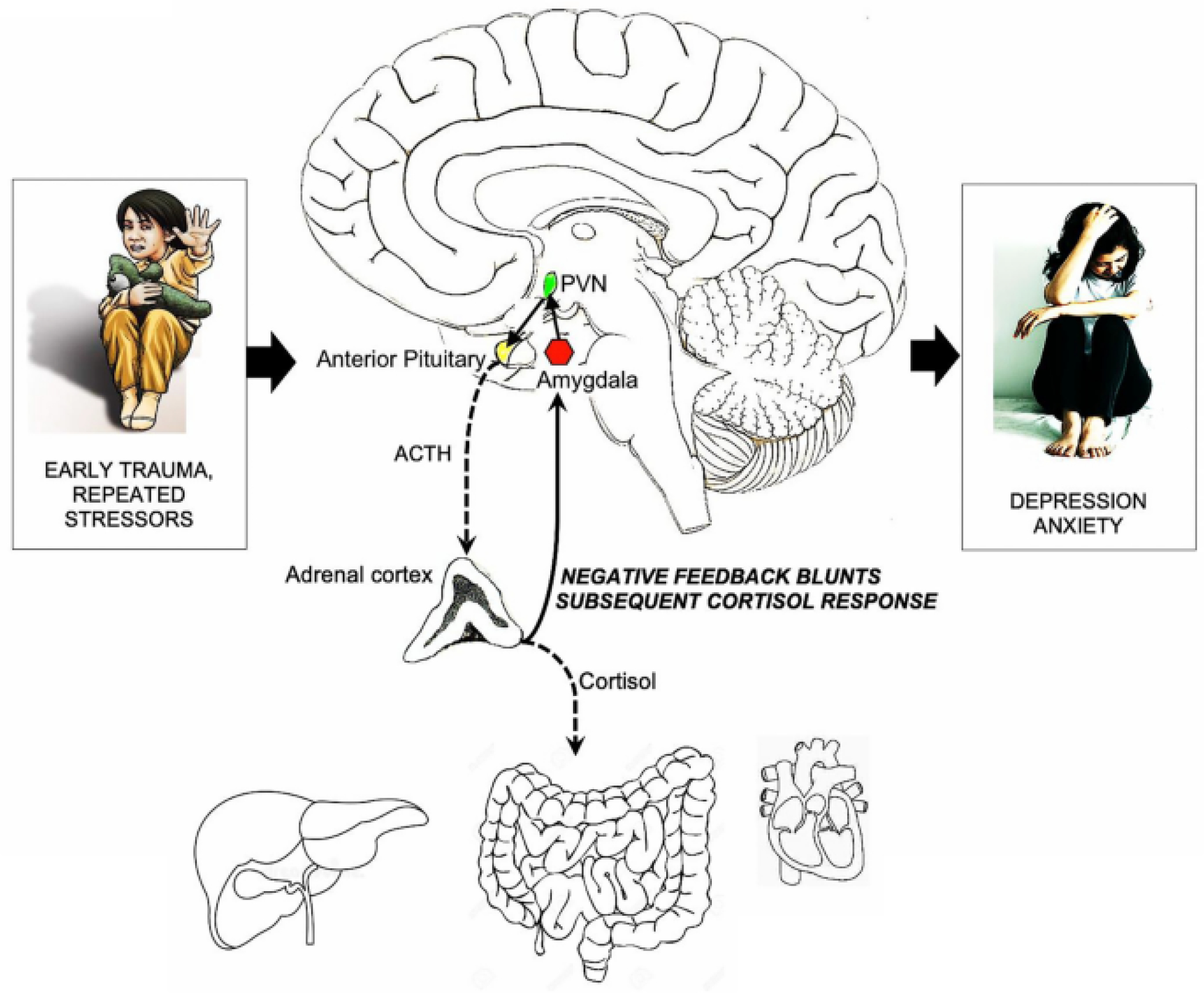

Acute and chronic stress activate well-described physiologic (acute stress) and pathophysiologic (chronic stress) changes in the central nervous system (CNS) and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, including elevation in corticosterone (rodents), cortisol (humans) and activation of the autonomic nervous system which can culminate in the enhanced perception of abdominal discomfort (Fig. 1) (Ulrich-Lai and Herman 2009; Nicolaides et al. 2015). For example, Johnson et al. demonstrated that exposure of the central amygdala (CeA) to elevated corticosterone (CORT) or water avoidance stress (WAS) increased corticotrophin releasing factor (CRF) expression and heightened visceral and somatic sensitivity. Infusion of CRF antisense oligodeoxynucleotides into the CeA decreased CRF expression and attenuated visceral and somatic hypersensitivity in both models (Johnson et al. 2015).

Fig. 1.

Hyperactivity of the glucocorticoid receptor (NR3C1)-CRH defense response pathway during early life leads to a blunted cortisol response later in life, in some cases resulting in depression and anxiety. Corticotropin releasing hormone is the human homologue of CRF

Epigenetic molecular mechanisms have been implicated in the dysregulation of the HPA axis. Histone acetylation is governed by histone acetyltransferases (HATs) and histone deacetylases (HDACs), the latter which remove the acetyl groups from both histone and non-histone proteins. HDAC inhibitors, including valproic acid and Trichostatin A (TSA), are molecules that block HDAC function. Using a validated model of moderate chronic intermittent psychological stress, such as water avoidance stress (WAS) stress, Tran et al. examined the hypothesis that epigenetic mechanisms within the CNS play a role in chronic stress-induced visceral hypersensitivity (Tran et al. 2013). TSA or vehicle were administered via an i.c.v. cannula. Visceral pain was assessed 24 h after the final WAS session and quantified by recording the number of abdominal contractions in response to graded pressures of colorectal distensions (CRD). In a separate group of rats that were exposed to repeated WAS or SHAM stress, the amygdala was isolated to assess the methylation status of glucocorticoid receptor (GR) and corticotropin releasing factor (CRF) genes via bisulfite sequencing and verified by pyrosequencing. GR and CRF gene expression were quantified via qRT-PCR. Stressed rats exhibited visceral hypersensitivity that was significantly attenuated by TSA. Compared to SHAM controls, methylation of the NR3C1 gene was increased following WAS, while expression of the NR3C1 gene was decreased. Methylation of the CRF promoter was decreased with WAS with a concomitant increase in CRF expression. This was one of the first studies to implicate the involvement of central epigenetic mechanisms in regulating stress-induced visceral hypersensitivity. Tran et al. (2015) subsequently reported that bilateral infusions of a histone deacetylase inhibitor into the CeA attenuated anxiety-like behavior as well as somatic and visceral hypersensitivity resulting from elevated CORT exposure. Furthermore, deacetylation of histone 3 at lysine 9 (H3K9), through the coordinated action of the NAD + -dependent protein deacetylase sirtuin-6 (SIRT6) and nuclear factor kappa B (NFκB), sequesters GR expression leading to disinhibition of CRF; thereby, providing additional support for the importance of epigenetic pathways in the amygdala in regulating the experience of chronic pain and anxiety. Currently, five classes of HDACs have been identified. Additional research is required to elucidate whether other HDACs are involved in the pathophysiology of chronic visceral pain or have distinct functions. Several HAT/HDAC and DNMT inhibitors are currently being used in the clinic for the treatment of various malignancies. It will be interesting to examine the potential role of these reagents to modulate pain signaling pathways.

The majority of research has been conducted in animal models, which can differ from human regulatory pathways. The clinical significance of the differences is unclear and an active area of research. Maternal and childhood stress are known risk factors that contribute to the development of depression and implicate that epigenetic changes are likely a key mechanism by which environmental stressors interact with the genome and genetic effects that lead to long term changes in behavior. With a more complete understanding of the role that enhancers, super-enhancers, non-coding RNAs, chromatin topology, transcription factors, and other regulatory elements play in epigenomics, it is apparent that early studies were limited by a singular focus on the impact of psychological stress on differential methylation of CpG islands near the promoters of candidate genes (Park et al. 2019). The early literature on DNA methylation is inconsistent regarding the impact of epigenetic modifications because of potentially confounding factors. For example, studies should control for the heterogeneous patient populations and the use of psychotropic agents due to their widespread use in depressed populations and their established effects on DNA methylation (Lotsch et al. 2013), studies that lacked appropriate controls, and some that may exhibit conformation bias (Li et al. 2019).

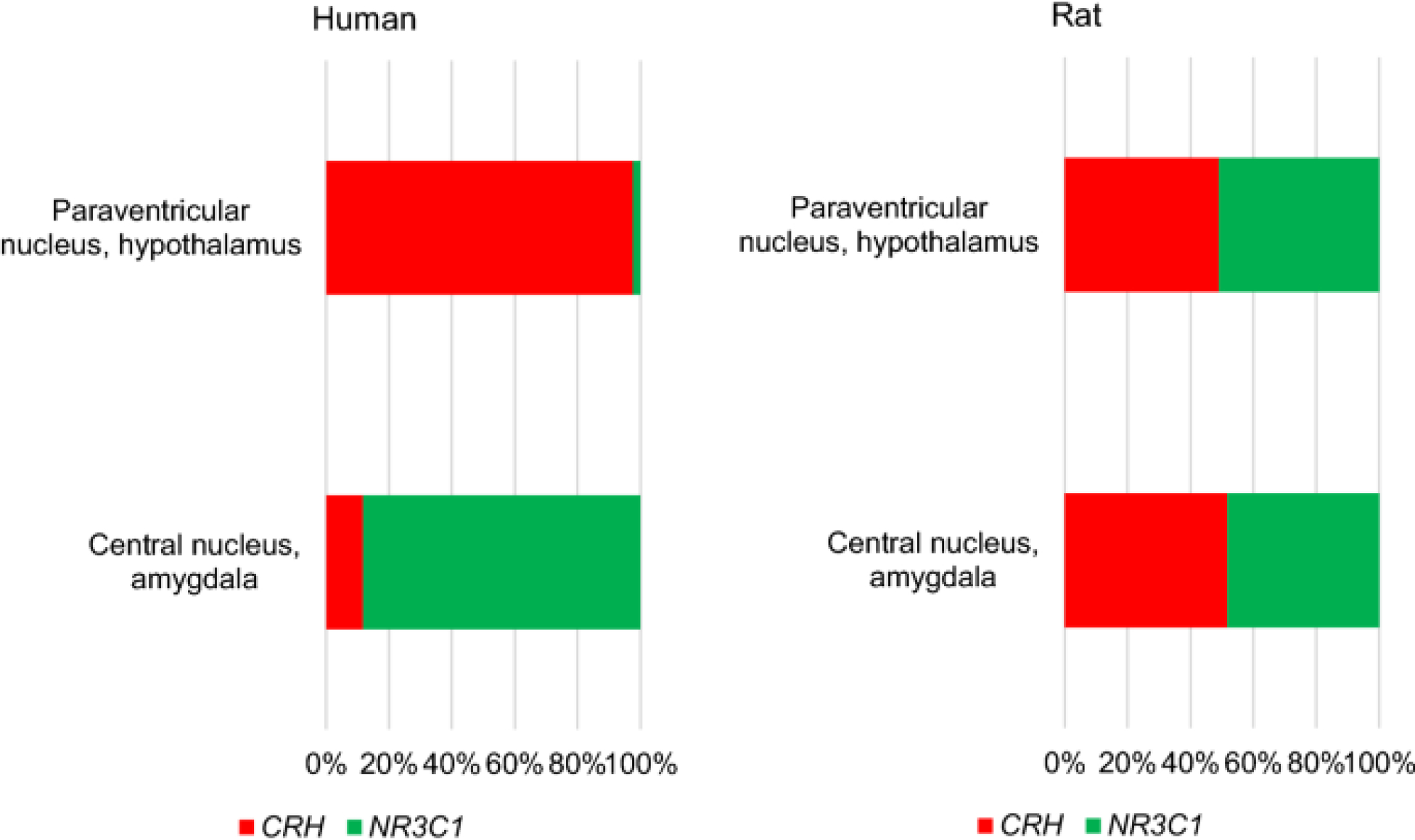

There has been some debate about whether chronic stress impacts NR3C1 in the CeA or hypothalamus as the key event in the initiation of blunted cortisol response following chronic psychological stress. For example, although it has been suggested that co-localized NR3C1 and CRF in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus are targeted for CpG methylation during stress, this is difficult to prove unequivocally from localization studies in which methylation levels are altered by 1 or 2% in rodent models of chronic stress (Brown et al. 2019). Comparison of normal expression levels of NR3C1 and CRH mRNA levels in these structures shows profound differences in relative amounts using other brain regions as controls (Fig. 2). In addition to the CeA comprising a much smaller volume of the amygdala in humans compared with other species, it also contains higher levels of NR3C1 gene expression relative to CRH, and more elevated expression of CRH mRNA in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus relative to NR3C1 mRNA levels in healthy controls (Fig. 2) (Gilbert and Ng 2018). In rat brain, the relative amounts of the basal expression of these two genes are similar (Fig. 2). Although these results are preliminary in nature, they suggest that humans may have evolved more specialized stress response pathways.

Fig. 2.

Relative amounts of NR3C1 mRNA and CRH mRNA in human brain and rat brain in the CeA and paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus (Tüchler and Kralik 2016)

Depression, Anxiety and Visceral Hyperalgesia: Background and the Emerging Role of Epigenomic Mechanisms

Anxiety and depression are common comorbidities in patients with IBS. A recent meta-analysis of 73 studies found that patients with IBS had a three–fourfold significantly higher likelihood of depression then healthy controls (Zamani et al. 2019). Geng et al. performed a meta-analysis of 22 studies, 16 of which were judged to be “high quality (Newcastle Criteria) with 1,244 IBS and 1048 inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) patients were included. They found no difference in the prevalence of depression and anxiety between these different patient populations, but the IBS patient population had more severe depression (P < 0.01) and anxiety (P < 0.0006) than patients diagnosed with IBD (Geng et al. 2018).

Rome IV criteria for IBS include: recurrent abdominal pain, on average, at least 1 day/week in the last 3 months, along with two or more of the following criteria: (i) associated with defecation; (ii) associated with a change in frequency of stool; (iii) associated with a change in form (appearance) of stool; and (iv) present for at least 6 months before diagnosis (Drossman 2016). Using Rome IV diagnostic criteria for IBS and a Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale score of ≥ 8 as the cut-off score, 45% of IBS patients reported anxiety and 26% depression (Midenfjord et al. 2019). Addante et al. studied IBS patients and healthy controls (HCs) who completed validated questionnaires measuring GI symptoms, psychosocial/somatic variables, physical [physical component score (PCS)] and mental [mental component score (MCS)]. Health-related quality of life (HRQOL) was assessed with the Short-Form-36 questionnaire (Addante et al. 2019). The strongest predictor of MCS was perceived stress in IBS and depression symptoms in HCs. GI symptom anxiety was the strongest predictor of PCS in both. Greater perceived stress, somatic symptom severity and less mindfulness were linked to larger reductions in HRQOL for IBS compared with HCs (Addante et al. 2019).

The linkage between pathophysiologic factors and symptoms in IBS remains poorly understood. It is also unclear whether these factors have cumulative effects on patient-reported outcomes (PROs). Simren et al. investigated whether pathophysiologic alterations associated with IBS have cumulative or independent effects on PROs in a retrospective analysis of data from 3 cohorts of patients with IBS based on Rome criteria, seen at a specialized unit for functional gastrointestinal disorders in Sweden from 2002 to 2014 (Simren et al. 2019). All patients underwent assessments of colonic transit time (radiopaque markers); compliance, allodynia, and hyperalgesia (rectal barostat); anxiety and depression (Hospital Anxiety and Depression scale), as pathophysiologic factors. PROs included IBS symptom severity, somatic symptom severity, and disease-specific quality of life. Allodynia (perception of pain or discomfort by non-noxious stimuli) was observed in 36% of patients, hyperalgesia (increased sensitivity to pain or enhanced intensity of pain sensation) in 22%, accelerated colonic transit in 18%, delayed transit in 7%, anxiety in 52%, and depression in 24%. With increasing number of pathophysiologic abnormalities, there was an increase in IBS symptom severity, somatic symptom severity, and a gradual reduction in quality of life (Simren et al. 2019). Thus, the available literature supports there is a connection between depression, anxiety and functional gastrointestinal disorders, particularly IBS.

The amygdala is a CNS structure that mediates the defense (“fight or flight”) response to a threat, and overactive amygdala activity causes chronic stress mediated, in part, through activation of the CRF system (Roozendaal et al. 2009). Alterations in amygdala activity are apparent in women who report a history of early-life stress (ELS) and those diagnosed with chronic pain disorders. Prusator et al. hypothesized that unpredictable ELS, previously shown to induce visceral hypersensitivity in adult female rats, alters GR and CRF expression in the central amygdala (CeA) (Prusator and Greenwood-Van Meerveld 2017). After neonatal ELS, visceral sensitivity and gene expression of GR and CRF were quantified in adult female rats. After unpredictable ELS, adult female rats exhibited visceral hypersensitivity and increased expression of GR and CRF in the CeA. After predictable ELS, adult female rats demonstrated normo-sensitive behavioral pain responses and upregulation of GR but not CRF in the CeA. After exposure to ELS paradigms, visceral sensitivity and gene expression within the CeA were not affected in adult male rats. The role of GR and CRF in modulating visceral sensitivity in adult female rats after ELS was investigated using oligodeoxynucleotide sequences targeted to the CeA for knockdown of GR or CRF. Knockdown of GR increased visceral sensitivity in all rats and revealed an exaggerated visceral hypersensitivity in females with a history of predictable or unpredictable ELS compared with that of controls. Knockdown of CRF expression or antagonism of CRF1 receptor in the CeA attenuated visceral hypersensitivity after unpredictable ELS. This is one of the first studies to examine the effect of ELS on adult visceral hypersensitivity and supports a shift in GR and CRF regulation within the CeA after ELS that underlies the development of visceral hypersensitivity in adulthood.

In a subsequent report, Louwies and Greenwood-Van Meerveld hypothesized that epigenetic mechanisms alter GR and CRH expression in the CeA and underlie chronic visceral pain after ELS. Neonatal rats were exposed to unpredictable, predictable ELS, or odor only (no stress control) from post-natal days 8–12 (Louwies and Greenwood-Van Meerveld 2020). In adulthood, visceral sensitivity was assessed or the CeA was isolated for Western blot or ChiP-qPCR to study histone modifications at the GR and CRH promoters. Female adult rats underwent stereotaxic implantation of indwelling cannulas for microinjections of garcinol (HAT inhibitor) into the CeA. After 7 days of microinjections, visceral sensitivity was assessed or the CeA was isolated for ChIP-qPCR assays. Unpredictable ELS increased visceral sensitivity in adult female rats, but not in male counterparts. ELS increased histone 3 lysine 9 (H3K9) acetylation in the CeA and H3K9 acetylation levels at the GR promoter in the CeA of adult female rats. After unpredictable ELS, H3K9 acetylation was increased and GR binding was decreased at the CRH promoter. Administration of garcinol in the CeA of adult females, that underwent unpredictable ELS, normalized H3K9 acetylation and restored GR binding at the CRH promoter. Thus, dysregulated histone acetylation and GR binding at the CRH promoter in the CeA is a potentially important pathway for memory retention of ELS events underlying visceral pain in adulthood.

A recent report supports that micro-RNA imbalance in the prefrontal cortex (PFC) might be involved in central sensitization (Satyanarayanan et al. 2019). Male Sprague Dawley rats were subjected to unpredictable chronic mild stress (UCMS) and spared nerve injury (SNI) to initiate depressive-like behavior and chronic pain behavior, respectively. Next-generation sequencing was employed to analyze PFC microRNAs in both the UCMS and SNI models. Rats exposed to either UCMS or SNI exhibited both depressive-like and chronic pain behaviors. Five specific microRNAs (miR-10a-5p, miR-182, miR-200a-3p, miR-200b-3p, and miR-429) were simultaneously downregulated in the depressive-like and chronic pain models after 4 weeks of short-term stress. Gene ontology revealed that the 4-week period of stress enhanced neurogenesis. Only the miR-200a-3p level was continuously elevated under prolonged stress, supporting the potential roles of reduced neurogenesis, inflammatory activation, disturbed circadian rhythm, lipid metabolism, and insulin secretion in the co-existence of pain and depression.

Some caveats bear mentioning. Antenatal stress affects the epigenetic profiles of GR (and GR-related genes), but the effects in mother and infant appear to be distinct. For example, maternal antenatal experience of war (Mulligan et al. 2012) or partner violence (Radtke et al. 2011) increased the GR methylation status examined in blood samples from the newborn and adolescents, while the mother’s epigenetic profile was unaffected. Methylation of the GR gene in human offspring is increased by parental psychopathology (Turecki and Meaney 2016) and early-life trauma (Smart et al. 2015) but aside from some studies looking at post-mortem brains (Chen et al. 2011; Alt et al. 2010; McGowan et al. 2009), the epigenome was typically examined in blood, which may or may not represent tissue-specific epigenetic changes occurring in the brain. For example, a study in mice revealed similar methylation changes in the GR-related gene and the FK506 binding protein, in the blood and hippocampus following treatment with high dose of corticosterone (Ewald et al. 2014). However, a study correlating epigenetic cytosine-phosphate-guanine (CpG) sites in the blood and temporal lobe biopsy tissues indicated that only 8% of methylation markers were consistent in the blood and brain (Walton et al. 2016).

Epigenetics and Peripheral Pain Pathways: Spinal Pain Pathways and Primary Afferent DRG Neurons

Spinal Pathways

The bulk of research examining the role of epigenetic regulatory pathways on pain perception in the spinal cord has focused on acute and chronic neuropathic pain caused by damage or disease affecting the somatosensory nervous system. Chemokine CXC receptor 4 (CXCR4) in spinal glial cells has been implicated in neuropathic pain. However, the regulatory cascades of CXCR4 in neuropathic pain remain elusive. Pan et al. investigated the functional regulatory role of miRNAs in the pain process and its interplay with CXCR4 and its downstream signaling. miR-23a, by directly targeting CXCR4, regulates neuropathic pain via the thioredoxin-Interacting Protein (TXNIP)-associated NLRP3 inflammasome axis in spinal glial cells (Pan et al. 2018). The NLRP3 inflammasome is a key component of the innate immune system that mediates caspase-1 activation and secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1β/IL-18 in response to microbial infection and cell damage. These results suggest that epigenetic interventions against miR-23a, CXCR4, or TXNIP may potentially serve as novel therapeutic avenues in treating peripheral nerve injury-induced nociceptive hypersensitivity.

Yadav and Weng investigated the role of enhancer of zeste homolog-2 (EZH2), a subunit of the polycomb repressive complex 2, in the spinal dorsal horn in the genesis of neuropathic pain in rats induced by partial sciatic nerve ligation (Yadav and Weng 2017). EZH2 is a histone lysine methyltransferase, which catalyzes the methylation of histone H3 on K27 (H3K27), resulting in gene silencing. EZH2 and tri-methylated H3K27 (H3K27TM) in the spinal dorsal horn were increased in rats with neuropathic post-nerve injuries. EZH2 was predominantly expressed in neurons in the spinal dorsal horn under normal conditions. The number of neurons with EZH2 expression was increased after nerve injury. Nerve injury significantly increased the number of microglia with EZH2 expression by more than sevenfold. Intrathecal injection of the EZH2 inhibitor attenuated the development and maintenance of mechanical and thermal hyperalgesia in rats with nerve injury. Such analgesic effects were concurrently associated with the reduced levels of EZH2, H3K27TM, Iba1, GFAP, TNF-α, IL-1β, and MCP-1 in the spinal dorsal horn in rats with nerve injury supporting that targeting the EZH2 signaling pathway could be an effective approach for the management of neuropathic pain.

Circular RNAs (circRNAs) are emerging as new players in regulation of gene expression, but whether and how circRNAs are involved in chronic pain is poorly understood. Pan et al. reported that the increase of circRNA-Filip1 mediated by miRNA-1224 in an argonaute 2 (Ago2)-dependent way in the spinal cord is involved in regulation of nociception via targeting Ubr5. Ago2 is the core component of micro-RNA (miRNA)-induced silencing complex and ubiquitin protein ligase E3 component N-recognin 5 (Ubr5) is best known as an important regulator in various cancers (Pan et al. 2019). This study supports a potentially interesting novel epigenetic mechanism of interaction between miRNA and circRNA in pain induced by chronic inflammation.

G-protein-coupled receptors (GPR) are considered to be cell surface sensors of extracellular signals and, thereby, have a crucial role in signal transduction and attractive targets for drug discovery. Jiang et al. examined the expression and the epigenetic regulation of the G protein-coupled receptor GRP151 in the spinal cord after spinal nerve ligation (SNL) and the contribution of GPR151 to neuropathic pain in male mice (Jiang et al. 2018). The GPR151 gene encodes an orphan member of the class A rhodopsin-like family of G-protein-coupled receptors. SNL dramatically increased GPR151 expression in spinal neurons. GPR151 mutation or spinal inhibition by shRNA alleviated SNL-induced mechanical allodynia and heat hyperalgesia. When the CpG island in the GPR151 gene promoter region was demethylated, the expression of DNA methyltransferase 3b (DNMT3b) was decreased, and the binding of DNMT3b with GPR151 promoter was reduced after SNL. Overexpression of DNMT3b in the spinal cord decreased GPR151 expression and attenuated SNL-induced neuropathic pain. Krüppel-like factor 5 (KLF5), a transcriptional factor of the KLF family, was upregulated in spinal neurons, and the binding affinity of KLF5 with GPR151 promoter was increased after SNL. Inhibition of KLF5 reduced GPR151 expression and attenuated SNL-induced pain hypersensitivity. mRNA microarray analysis revealed that mutation of GPR151 reduced the expression of a variety of pain-related genes in response to SNL, particularly mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathway-associated genes suggesting that GPR151, increased by DNA demethylation and the enhanced interaction with KLF5, contributes to the maintenance of neuropathic pain via increasing MAPK pathway-related gene expression.

Primary Afferent Dorsal Root Ganglia (DRG) Neurons

Ding et al. reported sodium channel (Nav1.6) upregulation involving tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α)/signal transducer and activator of the transcription 3 (STAT3) pathway and subsequent STAT3-mediated histone H4 hyper-acetylation in the Scn8a gene promoter region in dorsal root ganglion (DRG), which contributed to lumbar 5 ventral root transection (L5-VRT)-induced neuropathic pain (Ding et al. 2019). Scn8a is a gene that encodes an alpha subunit of the voltage-gated sodium channel Nav1.6 which mediates voltage-dependent sodium ion permeability of excitable membranes. Intraperitoneal injection of the TNF-α inhibitor thalidomide reduced the phosphorylation of STAT3 and decreased the recruitment of STAT3 and histone H4 hyper-acetylation in the Scn8a promoter, and subsequently attenuated Nav1.6 upregulation in DRG neurons and mechanical allodynia induced by L5-VRT. This represents a potentially novel epigenetic mechanism to explain mechanical allodynia.

The methyl-CpG-binding domain protein 1 (MBD1), an epigenetic repressor, regulates gene transcriptional activity. Mo et al. report that MBD1 in primary sensory DRG neurons is important for the genesis of acute pain and neuropathic pain as DRG MBD1-deficient mice exhibited reduced responses to acute mechanical, heat, cold, and capsaicin stimuli and blunted nerve injury-induced pain hypersensitivities (Mo et al. 2018). Overexpression of MBD1 led to spontaneous pain and evoked pain hypersensitivities in the wild-type (WT) mice and restores acute pain sensitivities in the MBD1-deficient mice. Mechanistically, MDB1 represses the mu-opioid receptor gene Oprm1 and Kcna2 gene expression that encodes the potassium channel Kv1.2 protein by recruiting DNA methyltransferase DNMT3a into these two gene promoters in the DRG neurons. These observations suggest that DRG MBD1 may be an important player under the conditions of acute pain and chronic neuropathic pain.

Zhou et al. reported that decreased colonic miR-199a/b correlates with visceral pain in the 2,4,6-trinitrobenzene sulfonic acid (TNBS) rat model and in patients with diarrhea-prone irritable bowel syndrome (IBS-D) (Zhou et al. 2016). Reduced miR-199a expression in rat DRG and colon tissue was associated with heightened visceral hypersensitivity. In vivo upregulation of miR-199a decreased visceral pain via inhibition of transient receptor potential cation channel subfamily V member 1 (TRPV1) receptor signaling. TRPV1 is also known as the capsaicin receptor and the vanilloid receptor 1 which is primarily expressed in sensory neurons and plays an important role in heat sensation and nociception. These results support that miR-199 precursors may be promising therapeutic candidates for the treatment in patients with visceral pain (Zhou et al. 2016).

Hong et al. examined the role of epigenetic regulatory pathways on specific genes involved in pain signaling in DRG neurons in the male chronic intermittent water avoidance stress (WAS) model (Hong et al. 2015). Chronic stress was associated with increased methylation of the glucocorticoid receptor (GR) gene Nr3c1 promoter and reduced expression of this gene in L6–S2 DRG neurons innervating the colon but not L4–L5 DRG neurons contributing to the sciatic nerve distribution. GR acts as a positive transcription factor in the pathways studied in this model. Stress was associated with upregulation in DNMT1-mediated methylation of the cannabinoid (CB) receptor 1 gene Cnr1 promoter and downregulation of glucocorticoid receptor–mediated expression of the CB-1 receptor (CNR1) in L6–S2, but not L4–L5, DRGs. Concurrently, chronic stress increased expression of the histone acetyltransferase EP300 and increased histone acetylation at the Trpv1 gene promoter and expression of the TRPV1 receptor in L6–S2 DRG neurons. Gene silencing knockdown of DNMT1 and EP300 in L6–S2 DRG neurons of rats reduced DNA methylation and histone acetylation, respectively, and prevented chronic stress-induced increases in visceral pain. These effects were reversible over the course of one month after completion of the WAS paradigm (Hong et al. 2015).

Epigenetic Pathways, Visceral Hyperalgesia: The Role of Intestinal Barrier Dysfunction

The observation that chronic stress is associated with region-specific alterations in pain signaling in DRG neurons innervating the rat colon (Zheng et al. 2016) but not sciatic nerve distribution, and decreased intestinal epithelial tight junction (TJ) protein expression that inversely correlated with the magnitude of enhanced visceral pain (Creekmore et al. 2018; Zong et al. 2019) support the conclusion that impaired intestinal barrier function may underlie chronic stress-associated visceral allodynia and hyperalgesia. It is noteworthy that the baseline level of GR protein expression in healthy control rats is significantly greater in the colon compared to the jejunum which may help explain the region-specific differences in chronic stress-associated reduction in TJ protein expression and increased permeability observed in the colon compared to the jejunum (Zheng et al. 2013). However, it is largely unknown how epigenetic pathways play a role in regulating epithelial TJ gene expression and function in chronic stress-associated visceral hyperalgesia.

Zhou et al. reported that in studies involving knockout mice and analyses of human intestinal tissue samples from patients with IBS-D, micro-RNA 29 reduces expression of the tight junction, claudin-1, and nuclear factor-kB-repressor factor to increase intestinal paracellular permeability (Zhou et al. 2015). Specifically, Intestinal tissues from patients with IBS-D (but not IBS with constipation or controls) demonstrated increased levels of MIR29 A and B, but reduced levels of CLDN1 and NKRF. Induction of colitis with TNBS and water avoidance stress increased levels of Mir29a and Mir29b and colon epithelial permeability in wild-type mice but markedly less in Mir29−/− mice. In microarray and knockdown experiments, MIR29A and B were found to reduce levels of NKRF and CLDN1 messenger RNA, and alter levels of other messenger RNAs that regulate intestinal permeability supporting a potentially significant role for this pathway in IBS-D patients (Zhou et al. 2015).

Wiley et al. reported that chronic WAS stress increased pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-6 expression prior to a decrease in TJ proteins the rat colon that inversely correlated with decreased occludin expression. Treatment with IL-6 induced visceral hyperalgesia (Wiley et al. 2020). Chronic stress and IL-6 increased repressive histone H3K9me2/me3 methylation and decreased transcriptional GR binding to the TJs occludin and claudin-1 gene promoters, leading to down-regulation of protein expression and increase in paracellular permeability. Intrarectal administration of a H3K9 methylation antagonist prevented chronic stress–induced visceral hyperalgesia in the WAS rat. In a human in vitro colonoid model, elevated cortisol decreased occludin expression, which was prevented by the GR antagonist RU486, and IL-6 increased H3K9 methylation and decreased TJ protein levels, which were prevented by preferential inhibitors of H3K9 methylation including UNC0642. It will be important to compare the results obtained with IL-6 with other relevant pro-inflammatory cytokines in future studies, determine whether there are specific roles for H3K9 di-methylation and trimethylation involving specific TJ proteins and examine likely differences in epigenetic regulatory pathways based on biological sex. For example, methylation of other repressive histones such as H3K27 may play a role in regulation of epithelial barrier function (Rosenfeld et al. 2009). It is also possible that reciprocal changes (decreased function) in activator histones such as H3K27 acetylation that are associated with active gene expression may also play a role in down-regulation in intestinal epithelial TJ gene and protein expression. Chronic stress- and pro-inflammatory cytokine–mediated increase in intestinal epithelial permeability has been implicated in the pathophysiology of numerous medical conditions including inflammatory bowel disease, Celiac disease, graft vs host disease, and type 1 diabetes mellitus (Camilleri 2019; Odenwald and Turner 2017), suggesting that the proposed role of H3K9 methylation may have impact beyond visceral hyperalgesia. With the emergence of molecularly targeted, region-specific interventions in the GI tract, these observations have the potential to lead to novel treatments for disorders associated with enhanced intestinal epithelial cell paracellular permeability (Tian et al. 2019).

Epigenetics and the Gut-Brain Axis: The Role of the Microbiome

The past two decades has witnessed the emergence of the microbiota as an important component of gut-brain function and generated broad interest for its contribution to normal physiology and, when perturbed (dysbiosis), the pathophysiological basis of psychiatric, neurodevelopmental, age-related, neurodegenerative, autoimmune, diabetes mellitus, obesity and functional GI disorders. The microbiota and the brain communicate with each other via various routes including the immune system, tryptophan (serotonin) and, possibly, purine metabolism, the vagus nerve, primary afferent sensory nerves, and the enteric nervous system via microbial metabolites such as short-chain fatty acids, branched chain amino acids, and peptidoglycans. Impaired intestinal epithelial barrier function appears to play a potentially pivotal role in this process via an increase in paracellular permeability to macromolecules. Several factors can influence microbiota composition in early life, including infection, mode of birth delivery, use of antibiotic medications, nutrition, environmental stressors, and host genetics. Microbial diversity diminishes with aging. Stress, in particular, can significantly impact the microbiota-gut-brain axis at all stages of life. Animal models have linked the regulation of fundamental neural processes, such as neurogenesis and myelination, to microbiome and activation of microglia (Mars et al. 2020; Cryan et al. 2019).

The literature examining a role for epigenetic regulatory pathways in the microbiome-gut-brain axis is rapidly evolving area of research. Hullar and Fu observed that gut microbiome alterations can induce epigenetic changes associated with human diseases and developmental disorders (Hullar and Fu 2014). The intestinal microbiome generates a variety of short-chain fatty acids (SCFA) for energy and ATP production. Bacteria from Clostridium, Eubacterium, and Butyrivibrio genera are able to synthesize butyrate from non-digestive fibers in the GI lumen that have inhibitory effects on HDACs (Bourassa et al. 2016). Germ-free (GF) mice demonstrated different histone 3 and histone 4 tail acetylation and methylation patterns in several tissues compared to control animals. These epigenetic changes were reversed after colonization with normal microbiota, or after supplementation of the diet in the GF mice with butyrate and other SCFAs (Puddu et al. 2014; Krautkramer et al. 2016).

Other studies support widespread dysregulation in mRNA expression in the amygdala of germ-free (GF) mice which were associated with behavioral changes (Stilling et al. 2015; Hoban et al. 2017, 2018). Specifically, GF mice demonstrated decreases in miR-182-5p and miR-183-5p, which are involved in amygdala-dependent stress and fear-related outputs, and decreases in miR-206-3p, which is known to alter brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) expression. Microbial colonization on post-natal day 21 partially restored miRNA expression patterns, that partially normalized impaired amygdala-dependent fear memory recall. miRNA expression was also dysregulated in the hippocampus of GF mice, that led to altered expression in genes associated with axon guidance, a prerequisite to locate and recognize synaptic partners during development. Colonization of the gut of adolescent mice did not reverse behavioral deficits supporting the significance that the timing of colonization plays on normal development (Chen et al. 2017).

Evidence supports that butyrate can cross the blood–brain barrier and alter the epigenome in the CNS. For example, in a rat model of depression, chronic butyrate treatment inhibited histone deacetylases in the brain, which lead to increases in BDNF and improvement of the phenotype (Wei et al. 2014). The GI microbiome contributes to the absorption and secretion of minerals including iodine, zinc, selenium, cobalt and other cofactors that participate in epigenetic processes. Other key metabolites of gut microbiota such as S-adenosylmethionine (SAM), acetyl-CoA, NAD, alpha-KG, and ATP serve as essential cofactors for epigenetic enzymes that regulate DNA methylation and histone modifications (Paul et al. 2015).

Some bacteria such as Helicobacter pylori are specifically linked to DNA methylation and decrease expression of O6-methylguanine DNA methyltransferase resulting in changes of local epigenetic signatures (Sepulveda et al. 2010). Other bacteria are capable of secreting proteins with epigenetic properties. For example, Mycobacterium tuberculosis produces a protein (Rv3423.1), which exhibits histone acetyltransferase activity in host cells and acetylates histone H3 at K9/K14 positions (Jose et al. 2016). Another secreted mycobacterial protein, Rv1988 that interacts with chromatin, has methyltransferase activity and methylates histone H3 at the H3R42 position which represses the expression of affected genes (Yaseen et al. 2015).

Other components of the gut-brain axis appear to be epigenetically influenced by the presence of the microbiota. For example, germ-free mice do not develop immune tolerance and demonstrate impaired intestinal barrier integrity. The absence of Lactobacilli and Bifidobacteria which are an important source of butyrate appears to be particularly important. Butyrate inhibits HDACs and, thereby, suppresses nuclear NF-κB activation, upregulates PPARγ expression and decreases IFNγ production in gut immune cells, promoting an anti-inflammatory gut environment (Berni Canani et al. 2012; Fofanova et al. 2016).

In summary, there is growing evidence supporting that microbiota can influence epigenetic regulatory pathways via the afferent (sensory) branch of the gut-brain axis. It is less well known how the efferent branch of the axis affects the intestinal microbiota which is an important area for future investigation. Overall, the significance and impact of intestinal microbiota on the GBA and epigenomic regulatory pathways requires confirmatory studies designed to prove causality. It is likely that intestinal microbiota will have a particularly important role in the post-partum “plastic” phase of intestinal development and the gut immune system (Milani et al. 2017; Wang et al. 2018; Butel et al. 2018).

Future Directions

Epigenomic mechanisms broadly impact pharmacodynamics, pharmacokinetics, adverse drug reactions, drug addiction, and drug resistance, all of which inform the identification of novel biomarkers as novel therapeutic targets and development of personalized medicine (Peedicayil 2019). With the rapid growth in interest in the role of epigenomic mechanisms in the regulation of the gut-brain axis, it is an opportune time to apply emerging strategies and tools such as deep learning to help guide the identification of potentially high-risk drug interactions, novel biomarkers, and therapeutic targets (Kalinin et al. 2018).

A contemporary view of molecular biology and human genetics shifts the paradigm from a linear gene-centric functional emphasis (with missense codons located within exons serving a primary role in human disease) to a different view of the human genome as a dynamic structure with three-dimensional (3D) chromatin interactions and histone modifications, along with other non-coding regulatory elements (Table 1). Genome variants including SNPs are located within non-coding epigenomic regulatory domains that have been significantly associated with IBS and other disorders of the gastrointestinal tract.

The microbiome certainly plays a significant role in the etiology of stress effects on the GBA, but more research needs to be undertaken in this domain to more clearly understand the cause and effect. In contrast, large consortia funded by the US National Institutes of Health and the European Union, including programs such as ENCODE (Luo et al. 2020), 4D Nucleome (Dekker et al. 2017), and the International Human Epigenome Consortium (Stunnenberg et al. 2016) clearly demonstrate that most significant genetic associations with human disease are mutations located in transcriptional enhancers (Buniello et al. 2019).

The recognition that the functional human genome operates in three dimensions and varies over time led to the discovery of enhancers, super-enhancers, and transcriptional condensates (Consortium 2012; Banani et al. 2017). For example, the glucocorticoid gene, NR3C1, maintains fixed enhancer chromatin loops to the thousands of genes that it regulates (Prekovic et al. 2019). The endogenous hormone progesterone only selects a specific subset of topology-associated domain (TAD)-specific enhancers to mediate its effects through chromatin loops within the human genome (Le Dily and Beato 2015) now considered a general property of hormone-regulated gene regulation on a genomewide basis (Le Dily et al. 2019). Recent research on estrogen has revealed that in the murine uterus, active chromatin looping between estrogen-specific super-enhancers are in place prior to puberty, but are reorganized by intrinsic effects of the hormone during puberty (Hewitt et al. 2020).

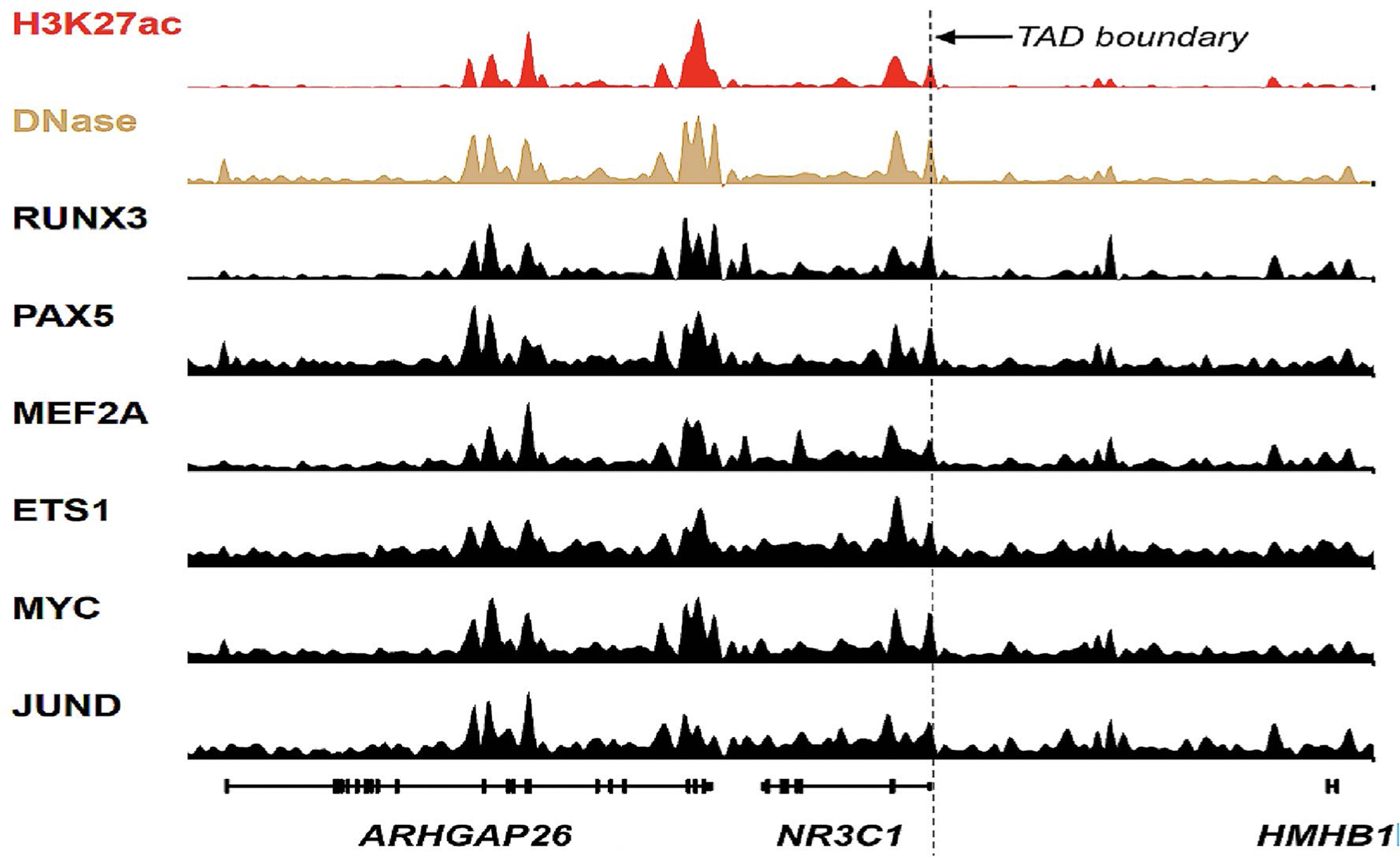

Recently discovered short-lived subnuclear liquid condensates, formed by specific super-enhancers or sets of super-enhancers, are pharmacodynamic targets for drugs that were thought to act primarily through cell surface receptors and solute carriers (Klein et al. 2020). This discovery has uncovered a new class of therapeutic targets that were previously unrecognized and provides an opportunity to develop drugs that modulate intrinsic hormone levels (Viny and Levine 2020). Of particular interest is that the super-enhancer that regulates NR3C1 gene expression only becomes part of a transcriptional condensate that is activated in animal models following an artificially induced defense response. One example of a NR3C1 gene super-enhancer is shown in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

A super-enhancer that controls the expression of NR3C1, ARHGAP26, and HMHB1 genes and its associated master transcription factors co-localized with histone 2 lysine 27 acetylation (H3K27ac) and DNase I allele-specific sensitivity (DNase) in blood cells. TAD Topologically associated domain. Modified from the figure published by Federation et al. 2018

The emergence of powerful computational methods in artificial intelligence such as deep learning has led to a greater understanding of epigenetic mechanisms that impact genome dynamics, including the impact of environmental perturbations such as psychological stress as well as insight into inter-individual variation in drug response. For example, using genome sequence as input, advanced deep learning methods can accurately predict in seconds the presence of epigenomic modifications including differential histone modifications, expression quantitative trait loci (eQTLs), and patient-specific adverse drug events, biological features that previously have taken years of biomedical research to understand and characterize (Fudenberg et al. 2020; Schwessinger et al. 2020). The use of these technologies to understand the impact of stress on epigenetic modification of the gut-brain axis must be guided by assiduous biological expertise to understand how patients are differentially affected by stress-induced epigenetic modifications.

Funding

John Wiley from NIDDK Grant No. R01 DK098205 and from National Institutes of Health Grant Nos. R21AT009253 and R21NS113127. Shaungsong Hong from National Institutes of Health Grant No. P30 DK34933.

References

- Addante R, Naliboff B, Shih W, Presson AP, Tillisch K, Mayer EA, Chang L (2019) Predictors of health-related quality of life in irritable bowel syndrome patients compared with healthy individuals. J Clin Gastroenterol 53(4):e142–e149. 10.1097/MCG.0000000000000978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allshire RC, Madhani HD (2018) Ten principles of heterochromatin formation and function. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 19(4):229–244. 10.1038/nrm.2017.119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alt SR, Turner JD, Klok MD, Meijer OC, Lakke EA, Derijk RH, Muller CP (2010) Differential expression of glucocorticoid receptor transcripts in major depressive disorder is not epigenetically programmed. Psychoneuroendocrinology 35(4):544–556. 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2009.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azpiroz F, Bouin M, Camilleri M, Mayer EA, Poitras P, Serra J, Spiller RC (2007) Mechanisms of hypersensitivity in IBS and functional disorders. Neurogastroenterol Motil 19(1 Suppl):62–88. 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2006.00875.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banani SF, Lee HO, Hyman AA, Rosen MK (2017) Biomolecular condensates: organizers of cellular biochemistry. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 18(5):285–298. 10.1038/nrm.2017.7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barutcu AR, Lajoie BR, Fritz AJ, McCord RP, Nickerson JA, van Wijnen AJ, Lian JB, Stein JL, Dekker J, Stein GS, Imbalzano AN (2016) SMARCA4 regulates gene expression and higher-order chromatin structure in proliferating mammary epithelial cells. Genome Res 26(9):1188–1201. 10.1101/gr.201624.115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berni Canani R, Di Costanzo M, Leone L (2012) The epigenetic effects of butyrate: potential therapeutic implications for clinical practice. Clin Epigenetics 4(1):4. 10.1186/1868-7083-4-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bird AP (1986) CpG-rich islands and the function of DNA methylation. Nature 321(6067):209–213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourassa MW, Alim I, Bultman SJ, Ratan RR (2016) Butyrate, neuroepigenetics and the gut microbiome: can a high fiber diet improve brain health? Neurosci Lett 625:56–63. 10.1016/j.neulet.2016.02.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourne S, Machado AG, Nagel SJ (2014) Basic anatomy and physiology of pain pathways. Neurosurg Clin N Am 25(4):629–638. 10.1016/j.nec.2014.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown A, Fiori LM, Turecki G (2019) Bridging basic and clinical research in early life adversity, dna methylation, and major depressive disorder. Front Genet 10:229. 10.3389/fgene.2019.00229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buniello A, MacArthur JAL, Cerezo M, Harris LW, Hayhurst J, Malan-gone C, McMahon A, Morales J, Mountjoy E, Sollis E, Suveges D, Vrousgou O, Whetzel PL, Amode R, Guillen JA, Riat HS, Trevanion SJ, Hall P, Junkins H, Flicek P, Burdett T, Hindorff LA, Cunningham F, Parkinson H (2019) The NHGRI-EBI GWAS Catalog of published genome-wide association studies, targeted arrays and summary statistics 2019. Nucleic Acids Res 47(D1):D1005–D1012. 10.1093/nar/gky1120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butel MJ, Waligora-Dupriet AJ, Wydau-Dematteis S (2018) The developing gut microbiota and its consequences for health. J Dev Orig Health Dis 9(6):590–597. 10.1017/S2040174418000119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camilleri M (2019) Leaky gut: mechanisms, measurement and clinical implications in humans. Gut 68(8):1516–1526. 10.1136/gutjnl-2019-318427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen ES, Ernst C, Turecki G (2011) The epigenetic effects of antidepressant treatment on human prefrontal cortex BDNF expression. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 14(3):427–429. 10.1017/S1461145710001422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen JJ, Zeng BH, Li WW, Zhou CJ, Fan SH, Cheng K, Zeng L, Zheng P, Fang L, Wei H, Xie P (2017) Effects of gut microbiota on the microRNA and mRNA expression in the hippocampus of mice. Behav Brain Res 322(Pt A):34–41. 10.1016/j.bbr.2017.01.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Consortium EP (2012) An integrated encyclopedia of DNA elements in the human genome. Nature 489(7414):57–74. 10.1038/nature11247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creekmore AL, Hong S, Zhu S, Xue J, Wiley JW (2018) Chronic stress-associated visceral hyperalgesia correlates with severity of intestinal barrier dysfunction. Pain 159(9):1777–1789. 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cryan JF, O’Riordan KJ, Cowan CSM, Sandhu KV, Bastiaanssen TFS, Boehme M, Codagnone MG, Cussotto S, Fulling C, Golubeva AV, Guzzetta KE, Jaggar M, Long-Smith CM, Lyte JM, Martin JA, Molinero-Perez A, Moloney G, Morelli E, Morillas E, O’Connor R, Cruz-Pereira JS, Peterson VL, Rea K, Ritz NL, Sherwin E, Spichak S, Teichman EM, van de Wouw M, Ventura-Silva AP, Wallace-Fitzsimons SE, Hyland N, Clarke G, Dinan TG (2019) The microbiota-gut-brain axis. Physiol Rev 99(4):1877–2013. 10.1152/physrev.00018.2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deaton AM, Bird A (2011) CpG islands and the regulation of transcription. Genes Dev 25(10):1010–1022. 10.1101/gad.2037511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dekker J, Belmont AS, Guttman M, Leshyk VO, Lis JT, Lomvardas S, Mirny LA, O’Shea CC, Park PJ, Ren B, Politz JCR, Shendure J, Zhong S, Network DN (2017) The 4D nucleome project. Nature 549(7671):219–226. 10.1038/nature23884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denk F, McMahon SB (2012) Chronic pain: emerging evidence for the involvement of epigenetics. Neuron 73(3):435–444. 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.01.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding HH, Zhang SB, Lv YY, Ma C, Liu M, Zhang KB, Ruan XC, Wei JY, Xin WJ, Wu SL (2019) TNF-alpha/STAT3 pathway epigenetically upregulates Nav1.6 expression in DRG and contributes to neuropathic pain induced by L5-VRT. J Neuroinflammation 16(1):29. 10.1186/s12974-019-1421-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drossman DA (2016) Functional gastrointestinal disorders: history, pathophysiology, clinical features and rome IV. Gastroenterology. 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.02.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ENCODE Project Consortium (2012) An integrated encyclopedia of DNA elements in the human genome. Nature 489(7414):57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewald ER, Wand GS, Seifuddin F, Yang X, Tamashiro KL, Potash JB, Zandi P, Lee RS (2014) Alterations in DNA methylation of Fkbp5 as a determinant of blood-brain correlation of glucocorticoid exposure. Psychoneuroendocrinology 44:112–122. 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2014.03.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Federation AJ, Polaski DR, Ott CJ, Fan A, Lin CY, Bradner JE (2018) Identification of candidate master transcription factors within enhancer-centric transcriptional regulatory networks. bioRxiv 2:1207. 10.1101/345413 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fischle W, Tseng BS, Dormann HL, Ueberheide BM, Garcia BA, Shabanowitz J, Hunt DF, Funabiki H, Allis CD (2005) Regulation of HP1-chromatin binding by histone H3 methylation and phosphorylation. Nature 438(7071):1116–1122. 10.1038/nature04219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fofanova TY, Petrosino JF, Kellermayer R (2016) Microbiome-epigenome interactions and the environmental origins of inflammatory bowel diseases. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 62(2):208–219. 10.1097/MPG.0000000000000950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fudenberg G, Kelley DR, Pollard KS (2020) Predicting 3D genome folding from DNA sequence with Akita. Nat Methods 17(11):1111–1117. 10.1038/s41592-020-0958-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao J, Wang WY, Mao YW, Graff J, Guan JS, Pan L, Mak G, Kim D, Su SC, Tsai LH (2010) A novel pathway regulates memory and plasticity via SIRT1 and miR-134. Nature 466(7310):1105–1109. 10.1038/nature09271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geng Q, Zhang QE, Wang F, Zheng W, Ng CH, Ungvari GS, Wang G, Xiang YT (2018) Comparison of comorbid depression between irritable bowel syndrome and inflammatory bowel disease: a meta-analysis of comparative studies. J Affect Disord 237:37–46. 10.1016/j.jad.2018.04.111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert TL, Ng L (2018) Chapter 3 The allen brain atlas: toward understanding brain behavior and function through data acquisition, visualization, analysis, and integration. In: Gerlai RT (ed) Molecular-genetic and statistical techniques for behavioral and neural research. Academic Press, San Diego, pp 51–72 [Google Scholar]

- Guo JU, Su Y, Shin JH, Shin J, Li H, Xie B, Zhong C, Hu S, Le T, Fan G, Zhu H, Chang Q, Gao Y, Ming GL, Song H (2014) Distribution, recognition and regulation of non-CpG methylation in the adult mammalian brain. Nat Neurosci 17(2):215–222. 10.1038/nn.3607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han P, Chang CP (2015) Long non-coding RNA and chromatin remodeling. RNA Biol 12(10):1094–1098. 10.1080/15476286.2015.1063770 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanning N, Edwinson A, Ceuleers H, Peters SA, De Man JG, Hassett LC, De Winter BY, Madhusudan G (2021) Intestinal barrier dysfunction in irritable bowel syndrome: a systematic review. Therap Adv Gastroenterol 14:1756284821993586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewitt SC, Grimm SA, Wu SP, DeMayo FJ, Korach KS (2020) Estrogen receptor alpha (ERalpha)-binding super-enhancers drive key mediators that control uterine estrogen responses in mice. J Biol Chem 295(25):8387–8400. 10.1074/jbc.RA120.013666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hnisz D, Abraham BJ, Lee TI, Lau A, Saint-André V, Sigova AA et al. (2013) Super-enhancers in the control of cell identity and disease. Cell 155(4):934–947 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoban AE, Stilling RM, Moloney GM, Moloney RD, Shanahan F, Dinan TG, Cryan JF, Clarke G (2017) Microbial regulation of microRNA expression in the amygdala and prefrontal cortex. Microbiome 5(1):102. 10.1186/s40168-017-0321-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoban AE, Stilling RM, Moloney G, Shanahan F, Dinan TG, Clarke G, Cryan JF (2018) The microbiome regulates amygdala-dependent fear recall. Mol Psychiatry 23(5):1134–1144. 10.1038/mp.2017.100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman HH, Schnitzlein HN (1961) The numbers of nerve fibers in the vagus nerve of man. Anat Rec 139:429–435. 10.1002/ar.1091390312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong S, Zheng G, Wiley JW (2015) Epigenetic regulation of genes that modulate chronic stress-induced visceral pain in the peripheral nervous system. Gastroenterology 148(1):148–157 e147. 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.09.032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hullar MA, Fu BC (2014) Diet, the gut microbiome, and epigenetics. Cancer J 20(3):170–175. 10.1097/PPO.0000000000000053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyun K, Jeon J, Park K, Kim J (2017) Writing, erasing and reading histone lysine methylations. Exp Mol Med 49(4):e324. 10.1038/emm.2017.11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang BC, Zhang WW, Yang T, Guo CY, Cao DL, Zhang ZJ, Gao YJ (2018) Demethylation of G-protein-coupled receptor 151 promoter facilitates the binding of kruppel-like factor 5 and enhances neuropathic pain after nerve injury in mice. J Neurosci 38(49):10535–10551. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0702-18.2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson AC, Tran L, Greenwood-Van Meerveld B (2015) Knockdown of corticotropin-releasing factor in the central amygdala reverses persistent viscerosomatic hyperalgesia. Transl Psychiatry 5:e517. 10.1038/tp.2015.16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jose L, Ramachandran R, Bhagavat R, Gomez RL, Chandran A, Raghunandanan S, Omkumar RV, Chandra N, Mundayoor S, Kumar RA (2016) Hypothetical protein Rv3423.1 of Mycobacterium tuberculosis is a histone acetyltransferase. FEBS J 283(2):265–281. 10.1111/febs.13566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalinin AA, Higgins GA, Reamaroon N, Soroushmehr S, Allyn-Feuer A, Dinov ID, Najarian K, Athey BD (2018) Deep learning in pharmacogenomics: from gene regulation to patient stratification. Pharmacogenomics 19(7):629–650. 10.2217/pgs-2018-0008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinde B, Gabel HW, Gilbert CS, Griffith EC, Greenberg ME (2015) Reading the unique DNA methylation landscape of the brain: Non-CpG methylation, hydroxymethylation, and MeCP2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 112(22):6800–6806. 10.1073/pnas.1411269112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein IA, Boija A, Afeyan LK, Hawken SW, Fan M, Dall’Agnese A, Oksuz O, Henninger JE, Shrinivas K, Sabari BR, Sagi I, Clark VE, Platt JM, Kar M, McCall PM, Zamudio AV, Manteiga JC, Coffey EL, Li CH, Hannett NM, Guo YE, Decker TM, Lee TI, Zhang T, Weng JK, Taatjes DJ, Chakraborty A, Sharp PA, Chang YT, Hyman AA, Gray NS, Young RA (2020) Partitioning of cancer therapeutics in nuclear condensates. Science 368(6497):1386–1392. 10.1126/science.aaz4427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klemm SL, Shipony Z, Greenleaf WJ (2019) Chromatin accessibility and the regulatory epigenome. Nat Rev Genet 20(4):207–220. 10.1038/s41576-018-0089-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krautkramer KA, Kreznar JH, Romano KA, Vivas EI, Barrett-Wilt GA, Rabaglia ME, Keller MP, Attie AD, Rey FE, Denu JM (2016) Diet-microbiota interactions mediate global epigenetic programming in multiple host tissues. Mol Cell 64(5):982–992. 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.10.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert SA, Jolma A, Campitelli LF, Das PK, Yin Y, Albu M et al. (2018) The human transcription factors. Cell 172(4):650–665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Dily F, Beato M (2015) TADs as modular and dynamic units for gene regulation by hormones. FEBS Lett 589(20 Part A):2885–2892. 10.1016/j.febslet.2015.05.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Dily F, Vidal E, Cuartero Y, Quilez J, Nacht AS, Vicent GP, Carbonell-Caballero J, Sharma P, Villanueva-Canas JL, Ferrari R, De Llobet LI, Verde G, Wright RHG, Beato M (2019) Hormone-control regions mediate steroid receptor-dependent genome organization. Genome Res 29(1):29–39. 10.1101/gr.243824.118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M, D’Arcy C, Li X, Zhang T, Joober R, Meng X (2019) What do DNA methylation studies tell us about depression? Syst Rev Transl Psychiatry 9(1):68. 10.1038/s41398-019-0412-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ligon CO, Moloney RD, Meerveld G-V (2016) Targeting epigenetic mechanisms for chronic pain: a valid approach for the development of novel therapeutics. J Pharmacol Ex Ther 357(1):84–93. 10.1124/jpet.115.231670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lotsch J, Schneider G, Reker D, Parnham MJ, Schneider P, Geisslinger G, Doehring A (2013) Common non-epigenetic drugs as epigenetic modulators. Trends Mol Med 19(12):742–753. 10.1016/j.molmed.2013.08.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louwies T, Greenwood-Van Meerveld B (2020) Sex differences in the epigenetic regulation of chronic visceral pain following unpredictable early life stress. Neurogastroenterol Motil 32(3):e13751. 10.1111/nmo.13751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louwies T, Johnson AC, Orock A, Yan T, van Meerveld BG (2020) The microbiota-gut-brain axis: an emerging role for the epigenome. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 245(2):138–145. 10.1177/1535370219891690 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo Y, Hitz BC, Gabdank I, Hilton JA, Kagda MS, Lam B, Myers Z, Sud P, Jou J, Lin K, Baymuradov UK, Graham K, Litton C, Miyasato SR, Strattan JS, Jolanki O, Lee JW, Tanaka FY, Adenekan P, O’Neill E, Cherry JM (2020) New developments on the encyclopedia of DNA elements (ENCODE) data portal. Nucleic Acids Res 48(D1):D882–D889. 10.1093/nar/gkz1062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mars RAT, Yang Y, Ward T, Houtti M, Priya S, Lekatz HR, Tang X, Sun Z, Kalari KR, Korem T, Bhattarai Y, Zheng T, Bar N, Frost G, Johnson AJ, van Treuren W, Han S, Ordog T, Grover M, Sonnenburg J, D’Amato M, Camilleri M, Elinav E, Segal E, Blekhman R, Farrugia G, Swann JR, Knights D, Kashyap PC (2020) Longitudinal multi-omics reveals subset-specific mechanisms underlying irritable bowel syndrome. Cell 182(6):1460–1473 e1417. 10.1016/j.cell.2020.08.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martienssen RA, Riggs AD, Russo VEA (1996) Epigenetic mechanisms of gene regulation. Cold Spring Harbor laboratory Press, Plainview [Google Scholar]

- McGowan PO, Sasaki A, D’Alessio AC, Dymov S, Labonte B, Szyf M, Turecki G, Meaney MJ (2009) Epigenetic regulation of the glucocorticoid receptor in human brain associates with childhood abuse. Nat Neurosci 12(3):342–348. 10.1038/nn.2270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Midenfjord I, Polster A, Sjovall H, Tornblom H, Simren M (2019) Anxiety and depression in irritable bowel syndrome: exploring the interaction with other symptoms and pathophysiology using multivariate analyses. Neurogastroenterol Motil 31(8):e13619. 10.1111/nmo.13619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milani C, Duranti S, Bottacini F, Casey E, Turroni F, Mahony J, Belzer C, Delgado Palacio S, Arboleya Montes S, Mancabelli L, Lugli GA, Rodriguez JM, Bode L, de Vos W, Gueimonde M, Margolles A, van Sinderen D, Ventura M (2017) The first microbial colonizers of the human gut: composition, activities, and health implications of the infant gut microbiota. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 10.1128/MMBR.00036-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller I (2018) The gut-brain axis: historical reflections. Microb Ecol Health Dis 29(1):1542921. 10.1080/16512235.2018.1542921 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mo K, Wu S, Gu X, Xiong M, Cai W, Atianjoh FE, Jobe EE, Zhao X, Tu WF, Tao YX (2018) MBD1 contributes to the genesis of acute pain and neuropathic pain by epigenetic silencing of Oprm1 and Kcna2 genes in primary sensory neurons. J Neurosci 38(46):9883–9899. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0880-18.2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan MAJ, Shilatifard A (2020) Reevaluating the roles of histone-modifying enzymes and their associated chromatin modifications in transcriptional regulation. Nat Genet 52(12):1271–1281. 10.1038/s41588-020-00736-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulligan CJ, D’Errico NC, Stees J, Hughes DA (2012) Methylation changes at NR3C1 in newborns associate with maternal prenatal stress exposure and newborn birth weight. Epigenetics 7(8):853–857. 10.4161/epi.21180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicolaides NC, Kyratzi E, Lamprokostopoulou A, Chrousos GP, Charmandari E (2015) Stress, the stress system and the role of glucocorticoids. NeuroImmunoModulation 22(1–2):6–19. 10.1159/000362736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odenwald MA, Turner JR (2017) The intestinal epithelial barrier: a therapeutic target? Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 14(1):9–21. 10.1038/nrgastro.2016.169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan Z, Li GF, Sun ML, Xie L, Liu D, Zhang Q, Yang XX, Xia S, Liu X, Zhou H, Xue ZY, Zhang M, Hao LY, Zhu LJ, Cao JL (2019) MicroRNA-1224 splicing circularRNA-Filip1l in an Ago2-dependent manner regulates chronic inflammatory pain via targeting Ubr5. J Neurosci 39(11):2125–2143. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1631-18.2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan Z, Shan Q, Gu P, Wang XM, Tai LW, Sun M, Luo X, Sun L, Cheung CW (2018) miRNA-23a/CXCR4 regulates neuropathic pain via directly targeting TXNIP/NLRP3 inflammasome axis. J Neuroinflammation 15(1):29. 10.1186/s12974-018-1073-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park C, Rosenblat JD, Brietzke E, Pan Z, Lee Y, Cao B, Zuckerman H, Kalantarova A, McIntyre RS (2019) Stress, epigenetics and depression: a systematic review. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 102:139–152. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2019.04.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul B, Barnes S, Demark-Wahnefried W, Morrow C, Salvador C, Skibola C, Tollefsbol TO (2015) Influences of diet and the gut microbiome on epigenetic modulation in cancer and other diseases. Clin Epigenetics 7:112. 10.1186/s13148-015-0144-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peedicayil J (2019) Pharmacoepigenetics and pharmacoepigenomics: an overview. Curr Drug Discov Technol 16(4):392–399. 10.2174/1570163815666180419154633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prekovic S, Schuurman K, Manjón AG, Buijs M, Peralta IM, Wellenstein MD, Yavuz S, Barrera A, Monkhorst K, Huber A, Morris B, Lieftink C, Silva J, Győrffy B, Hoekman L, van den Broek B, Teunissen H, Reddy T, Faller W, Beijersbergen R, Jonkers J, Altelaar M, de Visser KE, de Wit E, Medema R, Zwart W (2019) Glucocorticoids regulate cancer cell dormancy. bioRxiv. 10.1101/750406 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Prusator DK, Greenwood-Van Meerveld B (2017) Amygdala-mediated mechanisms regulate visceral hypersensitivity in adult females following early life stress: importance of the glucocorticoid receptor and corticotropin-releasing factor. Pain 158(2):296–305. 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puddu A, Sanguineti R, Montecucco F, Viviani GL (2014) Evidence for the gut microbiota short-chain fatty acids as key pathophysiological molecules improving diabetes. Mediators Inflamm 2014:162021. 10.1155/2014/162021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radtke KM, Ruf M, Gunter HM, Dohrmann K, Schauer M, Meyer A, Elbert T (2011) Transgenerational impact of intimate partner violence on methylation in the promoter of the glucocorticoid receptor. Transl Psychiatry 1:e21. 10.1038/tp.2011.21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roozendaal B, McEwen BS, Chattarji S (2009) Stress, memory and the amygdala. Nat Rev Neurosci 10(6):423–433. 10.1038/nrn2651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenfeld JA, Wang Z, Schones DE, Zhao K, DeSalle R, Zhang MQ (2009) Determination of enriched histone modifications in non-genic portions of the human genome. BMC Genomics 10:143. 10.1186/1471-2164-10-143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruthenburg AJ, Allis CD, Wysocka J (2007) Methylation of lysine 4 on histone H3: intricacy of writing and reading a single epigenetic mark. Mol Cell 25(1):15–30. 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.12.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saliminejad K, Khorram Khorshid HR, Soleymani Fard S, Ghaffari SH (2019) An overview of microRNAs: biology, functions, therapeutics, and analysis methods. J Cell Physiol 234(5):5451–5465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos-Rosa H, Schneider R, Bannister AJ, Sherriff J, Bernstein BE, Emre NC, Schreiber SL, Mellor J, Kouzarides T (2002) Active genes are tri-methylated at K4 of histone H3. Nature 419(6905):407–411. 10.1038/nature01080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sartorelli V, Lauberth SM (2020) Enhancer RNAs are an important regulatory layer of the epigenome. Nat StructMol Biol 27(6):521–528. 10.1038/s41594-020-0446-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satyanarayanan SK, Shih YH, Wen YR, Palani M, Lin YW, Su H, Galecki P, Su KP (2019) miR-200a-3p modulates gene expression in comorbid pain and depression: molecular implication for central sensitization. Brain Behav Immun 82:230–238. 10.1016/j.bbi.2019.08.190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxonov S, Berg P, Brutlag DL (2006) A genome-wide analysis of CpG dinucleotides in the human genome distinguishes two distinct classes of promoters. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103(5):1412–1417. 10.1073/pnas.0510310103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwessinger R, Gosden M, Downes D, Brown RC, Oudelaar AM, Telenius J, Teh YW, Lunter G, Hughes JR (2020) DeepC: predicting 3D genome folding using megabase-scale transfer learning. Nat Methods 17(11):1118–1124. 10.1038/s41592-020-0960-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sepulveda AR, Yao Y, Yan W, Park DI, Kim JJ, Gooding W, Abudayyeh S, Graham DY (2010) CpG methylation and reduced expression of O6-methylguanine DNA methyltransferase is associated with Helicobacter pylori infection. Gastroenterology 138(5):1836–1844. 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.12.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]