Setting and Problem

The practice of medicine includes many skills that are difficult to teach and master, including the development of broad differential diagnoses. Opportunities to practice these skills require time, attention, and, optimally, a safe, structured setting. Typically, trainees exercise these skills informally during patient care or in didactic “table case” sessions. These exercises are limited by the need to cover the most common or iconic presentations or are subject to those diagnoses that present for care. Time constraints and patient volumes make opportunities for teaching and skills exercises increasingly rare. Games are an effective, fun, and low-resource method of teaching and are increasingly being used in medical education.1,2 We seek to create games that help trainees develop skills not amenable to didactics and that require practice to master.

Intervention

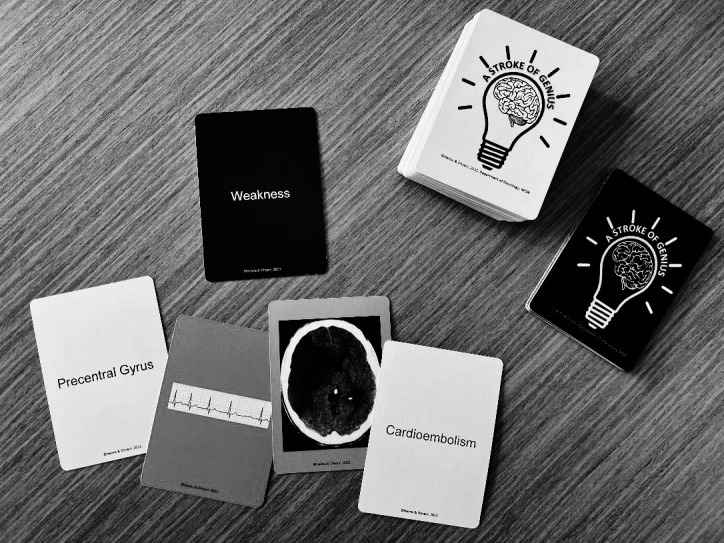

We created a card game for trainees to develop and exercise differential diagnostic skills. In the game there are 2 card decks. The first includes presenting symptoms, such as “Weakness.” The second contains 4 types of cards: Anatomy, such as “Precentral Gyrus”; Predisposing Condition, such as a tracing of atrial fibrillation; Pathology, such as a CT scan of a stroke; and Pathophysiology, such as “Cardioembolism.” Trainees draw a hand of 7 cards from the second deck and must play a card that matches the symptom card. Each trainee plays any card from their hand that works with the symptom, but it must also work with the previously played cards. Consequently, the evolving case becomes more specific with subsequent plays (see Figure). Trainees are encouraged to argue for their card and discuss possible explanations. A proctor, usually an attending or fellow who can monitor several games at once, makes the final decision. The last player to play an appropriate card on the case wins the hand. A new symptom card is then played. This original game, called Stroke of Genius, presents neurovascular concepts and is played in groups of 4 lasting 1 hour. After Institutional Review Board approval, players were surveyed to rank ease of play, enjoyability, and effectiveness in reinforcing neurovascular concepts, as well as whether games should be included more frequently in educational settings. A second version, presenting otolaryngology concepts, was adapted to an online format for individual practice, with a random generator presenting a symptom card and then a sequence of random concept cards for the trainee to consider how they could relate. This format could also be used as a 2-minute “warm-up” before didactics or even prior to rounds to initiate discussion.

Figure.

A Stroke of Genius: Game Play Example

Outcomes to Date

The neurovascular game has been played by more than 65 medical students and residents (24 residents) and has been extremely well received. Median evaluations (for the whole group and the resident subgroup) on a 1 to 5 Likert scale were 5 for ease of play, 5 for enjoyability, and 5 for effectiveness at reinforcing neurovascular concepts. All 65 trainees surveyed ranked the game as somewhat or very effective and somewhat or very enjoyable. Written comments also stated that trainees would like to do more of this sort of learning. This game presents hundreds of case combinations in the span of 1 hour and may be played repeatedly. The structure of matching cards presenting anatomy, predisposing conditions, pathology, and pathophysiology to a presenting symptom can be adapted to almost any area of medicine, as evidenced by the successful use in both neurovascular disease and otolaryngology. Games increase individual trainee engagement and encourage active creativity and discussion of content, while creating a limited faculty burden.

References

- 1.Watsjold BK, Cosimini M, Mui P, Chan TM. Much ado about gaming: an educator's guide to serious games and gamification in medical education. AEM Educ Train . 2022;6(4):e10794. doi: 10.1002/aet2.10794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gentry SV, Gauthier A, L'Estrade Ehrstrom B, et al. Serious gaming and gamification education in health professions: systematic review. J Med Internet Res . 2019;21(3):e12994. doi: 10.2196/12994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]