Abstract

Background

The format for residents to present hospitalized patients to teaching faculty is well defined; however, guidance for presenting in clinic is not uniform.

Objective

We report the development, implementation, and evaluation of a new standardized format for presenting in clinic: the Problem-Based Presentation (PBP).

Methods

After a needs assessment, we implemented the format at the teaching clinics of our internal medicine residency program. We surveyed participants on innovation outcomes, feasibility, and acceptability (pre-post design; 2019-2020; 5-point scale). Residents' primary outcomes were confidence in presentation content and presentation order, presentation efficiency, and presentation organization. Faculty were asked about the primary outcomes of resident presentation efficiency, presentation organization, and satisfaction with resident presentations.

Results

Participants were 111 residents and 22 faculty (pre-intervention) and 110 residents and 20 faculty (post-intervention). Residents' confidence in knowing what the attending physician wants to hear in an outpatient presentation, confidence in what order to present the information, and how organized they felt when presenting in clinic improved (all P<.001; absolute increase of the top 2 ratings of 25%, 28%, and 31%, respectively). Residents' perceived education in their outpatient clinic also improved (P=.002; absolute increase of the top 2 ratings of 19%). Faculty were more satisfied with the structured presentations (P=.008; absolute increase of the top 2 ratings of 27%).

Conclusions

Implementation of a new format for presenting in clinic was associated with increased resident confidence in presentation content, order of items, overall organization, and a perceived increase in the frequency of teaching points reviewed by attending physicians.

Introduction

The Subjective, Objective, Assessment, and Plan (SOAP) format was developed in the 1960s to standardize clinical documentation.1 The SOAP format is still the primary guide for residents' oral patient presentations to attending physicians,2 which facilitates a shared mental model for communication. In our experience, the format is effective for hospital presentations or clinic patients presenting with a single issue; however, trainees often struggle to adapt the SOAP format to a clinic patient presenting with multiple problems. An alternative case presentation format, SNAPPS (Summarize history and findings; Narrow the differential; Analyze the differential; Probe preceptor about uncertainties; Plan management; Select case-related issues for self-study) is designed to facilitate the learner's expression of clinical uncertainties and promote self-directed learning.3,4 Similarly, we found learners struggled to adapt the SNAPPS model to the presentation of a clinic patient with multiple problems. The One-Minute Preceptor5,6 is a more preceptor-centered intervention that does not inform the organization of the learner's presentation.

We could not find uniform guidance in the literature of any presentation styles other than SOAP, SNAPPS, or the One-Minute Preceptor5-8 in discussions of teaching in the ambulatory setting for any specialty. In a recent review, Logan et al9 confirms the paucity of evidence and offers advice for teaching in clinic. Given this gap in the literature, we developed and implemented a new format for presenting in clinic: the Problem-Based Presentation (PBP). In this report, we describe the needs assessment, development, and implementation of the PBP format, and present preliminary outcomes of the rollout of the format. Directors of residency clinics and clerkships could use the results of this study to guide residents and students during presentations in teaching clinics.

Objectives

We report the development, implementation, and evaluation of a new standardized format for residents presenting patients to faculty preceptors in clinic: the Problem-Based Presentation (PBP).

Findings

Implementation of the PBP was associated with increased resident confidence in presentation content, order of items, overall organization, and a perceived increase in the frequency of teaching points reviewed by attending physicians.

Limitations

There is lack of objective measures of efficiency, teaching, or adherence to PBP format.

Bottom Line

Implementation of the PBP format in residency programs and adoption into medical school curricula could lead to a standardized outpatient presentation format where residents feel prepared and confident presenting in clinic when they enter clinical training.

Methods

Setting and Participants

The PBP format innovation was implemented at the Tinsley Harrison Internal Medicine Residency program teaching clinics in January 2020. The program has more than 100 residents and is located in Birmingham, Alabama, a medium-sized metropolitan area in the United States. Residents have their continuity clinics at university-based and veterans affairs-based sites. We followed guidance from the 6-step approach for curriculum design.10

Intervention

Needs Assessment

During intern orientation in June 2015, we administered an anonymous survey; all 60 interns participated (internal medicine, medicine-pediatrics, preliminary medicine, anesthesiology, neurology, and medicine-genetics; representing 40 medical schools). The survey asked interns if they were taught a standard oral presentation format for various clinical settings as well as their confidence in presenting. All indicated they were taught a format for hospital admission oral presentations, 98% (59 of 60) for subsequent day hospital presentations, 83% (50 of 60) for acute outpatient presentations, and 72% (43 of 60) for follow-up outpatient visits for patients with multiple problems. Ninety-two percent (55 of 60) were comfortable or very comfortable presenting a subsequent day hospital patient, while only 53% (32 of 60) were comfortable presenting an outpatient follow-up visit.

Development of the Educational Innovation

To understand how resident outpatient presentations evolve over training, 30 of the categorical internal medicine residents participated in 1 of 3 focus groups in fall 2015 (12 postgraduate year [PGY]-1, 5 PGY-2-3, and 13 PGY-2-3 trainees, respectively). A trained focus group leader, unaffiliated with the residency program, facilitated each session with an interview guide (see online supplementary data) to explore each question until saturation was reached. Participants were informed that sessions would be audio-recorded, transcribed, and de-identified to facilitate participation.

Using an inductive approach, 2 coauthors (R.R.K, E.D.S.) conducted a content analysis of transcripts independently to derive themes, which they subsequently reviewed and reconciled until both reviewers agreed on 3 main themes that encompassed the experience of participants. The themes were: (1) presenting in clinic is challenging in part because there are no clear expectations of how to present and feedback is not given; (2) resident presentations evolve based on trial and error, nonverbal cues from attendings, and role modeling upper-level resident presentations; and (3) most residents eventually adapt a problem-based presentation style, with an opening sentence, which is felt to add important organization to clinic presentations, making them cognitively easier to both present and to follow. Utilizing the focus group themes, 3 coauthors (S.S.S., R.R.K., E.D.S.: clinician educators with leadership roles in the internal medicine residency program) developed the PBP format.

The presentation format begins with an opening statement to orient the preceptor to important chronic conditions and the patient concerns addressed during the visit (Table). This is followed by a mini-SOAP presentation for each medical condition or new issue and ends with preventative health measures, anticipated return to clinic date, and suggested level of billing. This flow may reduce cognitive load for the learner and preceptor by developing a plan for each problem one by one and finishing each issue before moving on to the next. We recommend beginning with the most concerning problem (to either the patient or the trainee) and continuing to more stable, chronic issues. Physical examination findings or test results are incorporated into the SOAP for each problem rather than as a separate section in the presentation. The PBP format was designed between October and December 2019.

Table.

The Problem-Based Presentation Structure and Example

| Structure | Example |

| Opening Sentence • Name • Age • Major medical problems • New or return • Last seen in clinic/last seen by you • Issues addressed today Problem 1 • Subjective No. 1 • Objective No. 1 • Assessment/plan No. 1 Problem 2 • Subjective No. 2 • Objective No. 2 • Assessment/plan No. 2 Problem 3 • Subjective No. 3 • Objective No. 3 • Assessment/plan No. 3 Health Maintenance (if addressed) (Even if busy, try to address 1 item each visit) • Vaccines • Age-appropriate screening • Habits Return to Clinic and Billing Level | Mr M is a 70-year-old man with a history of hypertension and COPD who presents today for follow-up. He was last seen by me 3 months ago for a regular visit. Today we discussed new wrist pain, hypertension, and health maintenance. Regarding his right wrist pain, he states onset was gradual and is worse with activity. Associated with numbness/tingling. OTC meds are not helping. Physical examination is notable for positive Tinel's and Phalen's sign. Likely carpal tunnel syndrome, plan to use splint and physical therapy, follow-up in 2 months. [pause for attending feedback] For his hypertension, he is taking his amlodipine 10 and lisinopril 20 as prescribed. BP today is 145/88, but he reports SBP is 120s at home. I provided him with a BP log and we will review it at his next appointment. [pause for attending feedback] For health maintenance, he is due for a screening colonoscopy. He also received his flu shot today. Other immunizations up to date. I want to see him back in 3 months and bill him a level 4. |

Abbreviations: COPD, Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; OTC, over the counter; BP, blood pressure; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

Innovation Implementation

To disseminate the new format to faculty preceptors and residents, we created a PBP Quick Guide (online supplementary data), which was posted in their clinic presentation areas. We identified faculty champions to promote the new format during clinic sessions and oriented new interns each academic year, beginning July 2020.

Outcomes Measured

We evaluated resident and faculty perspectives toward the outpatient presentation before (October 2019) and after (October 2020) the implementation of the PBP format with a locally developed cross-sectional survey. Authors discussed survey items iteratively for clarity before finalizing items.

The survey for residents included primary (confidence in content, order, efficiency, and organization) and secondary outcomes (presentation format changes based on preceptor or patients' problem, time spent, teaching points from attending, confidence in plan, satisfaction, and clinic importance) as well as 2 open-ended questions (results not presented). The survey for faculty included primary outcomes (resident presentation efficiency, presentation organization, and satisfaction with resident presentations) and secondary outcomes (impact of presentation format on teaching, patient care advice, and other aspects). The online supplementary data contain the surveys.

Analysis

We used the Mann-Whitney U test (pre/post) analysis with Bonferroni correction due to multiple testing (for residents, adjusted P<.013 for primary outcomes, P<.007 for secondary outcomes). To illustrate the magnitude of the differences, as the ordinal data were not normally distributed, we report the absolute increase of the top 2 ratings. The pre- and post-surveys were not paired to specific individuals.

The local Institutional Review Board at the University of Alabama at Birmingham Heersink School of Medicine approved the study (IRB-15041001).

Results

The response rate for residents was 85% (111 of 130, pre) and 85% (110 of 130, post) and for faculty 88% (22 of 25, pre) and 80% (20 of 25, post). Online supplementary data show participant characteristics.

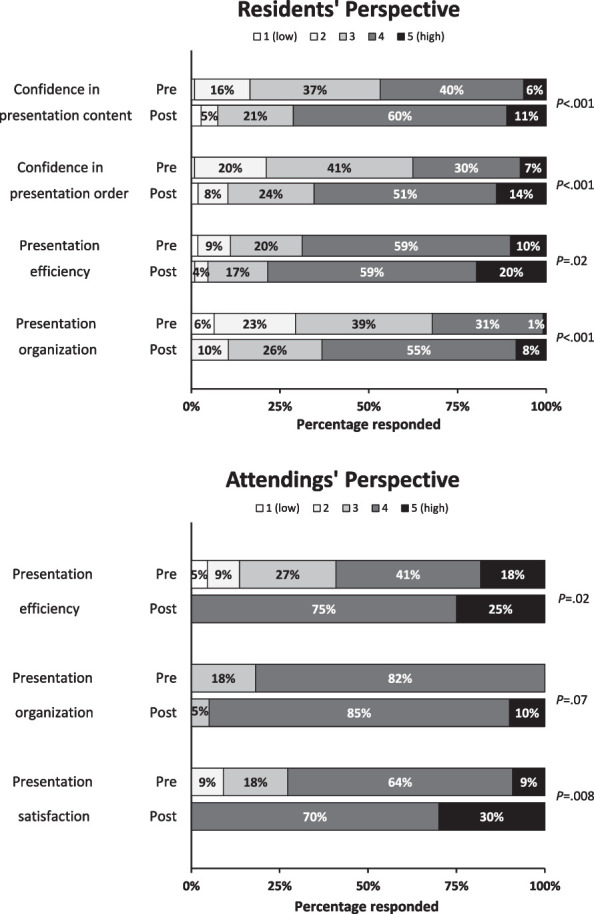

The Figure shows the primary outcomes for residents and faculty. We observed significant improvements in residents' confidence in presentation content, presentation order, and presentation organization (all P<.001; an absolute increase of the top 2 ratings of 25%, 28%, and 31%, respectively; Figure, top panel). Faculty were more satisfied with the presentation (P=.008; an absolute increase of the top 2 ratings of 27%; Figure, bottom panel).

Figure.

Resident and Attending Pre-Post Results

Note: Resident (top panel) and attending (bottom panel) perspectives during patient presentations in teaching clinics (primary outcomes). Each graph shows the distribution of answers, divided via Likert scale response, with sum adding to 100%. Values represent low to high for the respective question (full wording of each survey item and scale is available in online supplementary data). P values are for comparison pre vs post (Mann-Whitney U test, significance level using Bonferroni's correction, P=.013 for residents and P=.017 for attendings).

Resident secondary endpoints that reached significance were the decrease in perception that the resident had to change the format of a patient presentation based on different attendings (P=.002; an absolute decrease of the top 2 ratings of 19%) or different patient problems (P<.001; an absolute decrease of the top 2 ratings of 29%), and an increase in the perceived frequency of teaching points reviewed by attending physicians (P=.002; an absolute increase of the top 2 ratings of 19%; online supplementary data). None of the faculty secondary endpoints reached statistical significance (online supplementary data).

Discussion

The PBP format for clinic patients improved residents' perceived confidence in presentation content, presentation order, and organization in their outpatient clinic. Residents also perceived an increase in the frequency of teaching points reviewed by attending physicians. Faculty were more satisfied with the structured presentation.

This study adds to the limited literature of approaches to improve the teaching experience in clinic. We hope that other institutions that implement a PBP format will see similar improvements from both resident and faculty perspectives. If PBP is proven generalizable, widespread implementation in residency programs and adoption into medical school curricula could lead to a standardized outpatient presentation format where residents feel prepared and confident with this skill when they enter clinical training. To aid other institutions, we created a website with a PBP teaching slide deck and handouts.11

The study has limitations. We did not use objective measures of efficiency, teaching, or clinical outcomes and did not track adherence. Also, generalizability is limited as we only examined the impact at one large academic internal medicine program. We believe this study is a necessary step for proof of concept.

Future research steps include: (1) demonstrating generalizability to medical student outpatient medicine clerkships and to other internal medicine residency programs; (2) demonstrating applicability to other fields, such as pediatrics, family medicine, or procedural specialties; and (3) examining the impact of PBP on specific domains of teaching in clinic (eg, clinical reasoning).

Conclusions

Implementation of a new PBP format for presenting in clinic was associated with increased resident confidence in presentation content, order of items, overall organization, and an increase in the perceived frequency of teaching points reviewed by attending physicians.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank April Agne and Jennifer Bares for leading the focus groups and overall assistance during this study.

Funding Statement

Funding: The authors report no external funding source for this study.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The authors declare they have no competing interests.

The Problem-Based Presentation format has been presented in workshop and abstract form at the Southern Society of General Internal Medicine Regional Meeting, February 14, 2020, and February 3, 2023, Society of General Internal Medicine Annual Meeting, April 20-23, 2021, and the Association of Program Directors in Internal Medicine national conference October 9, 2020.

The opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors alone and do not reflect the views of the US Department of Veterans Affairs.

References

- 1.Weed L. Medical records that guide and teach. N Engl J Med . 1968;278(12):652–657. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196803212781204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hadvani T, Hubenthal E, Chase L. Transitions to inpatient medicine clerkship's SOAP: notes and presenting on rounds. MedEdPORTAL . 2016;12:10366. doi: 10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10366. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wolpaw TM, Wolpaw DR, Papp KK. SNAPPS: a learner-centered model for outpatient education. Acad Med . 2003;78(9):893–898. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200309000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wolpaw T, Papp KK, Bordage G. Using SNAPPS to facilitate the expression of clinical reasoning and uncertainties: a randomized comparison group trial. Acad Med . 2009;84(4):517–524. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31819a8cbf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aagaard E, Teherani A, Irby DM. Effectiveness of the one-minute preceptor model for diagnosing the patient and the learner: proof of concept. Acad Med . 2004;79(1):42–49. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200401000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Neher JO, Gordon KC, Meyer B, Stevens N. A five-step “microskills” model of clinical teaching. J Am Board Fam Pract . 1992;5(4):419–424. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dent JA. AMEE guide no 26: clinical teaching in ambulatory care settings: making the most of learning opportunities with outpatients. Med Teach . 2005;27(4):302–315. doi: 10.1080/01421590500150999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cohen DA, Truglio J. Fitting it all in: an interactive workshop for clinician-educators to improve medical education in the ambulatory setting. MedEdPORTAL . 2017;13:10611. doi: 10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Logan AA, Rao M, Evans G. Twelve tips for teaching and supervising post-graduate trainees in clinic. Med Teach . 2022;44(7):720–724. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2021.1912307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thomas PA, Kern DE, Hughes MT, Chen BY. Curriculum Development for Medical Education A SixStep Approach 3rd ed Johns Hopkins University Press; 2016.

- 11.The University of Alabama at Birmingham. Division of General Internal Medicine Heersink School of Medicine Problem Based Presentation (PBP) Accessed May 2, 2023. https://go.uab.edu/pbp.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.