Abstract

Tau plays a key role in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) pathophysiology, and accumulating evidence suggests that lowering tau may reduce this pathology. We sought to inhibit MAPT expression with a tau-targeting antisense oligonucleotide (MAPTRx) and reduce tau levels in patients with mild AD. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multiple-ascending dose phase 1b trial evaluated the safety, pharmacokinetics and target engagement of MAPTRx. Four ascending dose cohorts were enrolled sequentially and randomized 3:1 to intrathecal bolus administrations of MAPTRx or placebo every 4 or 12 weeks during the 13-week treatment period, followed by a 23 week post-treatment period. The primary endpoint was safety. The secondary endpoint was MAPTRx pharmacokinetics in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). The prespecified key exploratory outcome was CSF total-tau protein concentration. Forty-six patients enrolled in the trial, of whom 34 were randomized to MAPTRx and 12 to placebo. Adverse events were reported in 94% of MAPTRx-treated patients and 75% of placebo-treated patients; all were mild or moderate. No serious adverse events were reported in MAPTRx-treated patients. Dose-dependent reduction in the CSF total-tau concentration was observed with greater than 50% mean reduction from baseline at 24 weeks post-last dose in the 60 mg (four doses) and 115 mg (two doses) MAPTRx groups. Clinicaltrials.gov registration number: NCT03186989.

Subject terms: Alzheimer's disease, Drug development

Evaluation of a tau-targeting antisense oligonucleotide in a phase 1 trial of patients with mild AD found it was well tolerated and resulted in a sustained reduction of tau protein levels.

Main

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder characterized by cognitive and functional decline resulting in substantial disability1. Onset of pathology is marked by progression of neuroimaging and fluid biomarker measures (preclinical phase) before the appearance of subtle cognitive changes, known as mild cognitive impairment (MCI). The eventual progression to dementia occurs over a variable period of time and is characterized by cognitive and behavioral symptoms that impair an individual’s ability to function in daily life2. Symptom onset typically occurs in patients aged 65 years and older, while symptom onset before age 65 accounts for less than 5% of all patients with AD3. Historically, diagnosis of AD has been primarily focused on clinical criteria4, but accumulating evidence has demonstrated that cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) biomarkers, including amyloid-β 42 (Aβ42) and tau (total tau (t-tau) and phosphorylated tau181 (p-tau181)) as well as positron emission tomography (PET)-amyloid and PET-tau, are reliable surrogate measures of neuropathologic change enabling more robust characterization of patients across the AD continuum5–7. For most patients with AD, treatment remains limited to multidisciplinary management of symptoms, including pharmacological therapies that have no disease-modifying impact. The recent US Food and Drug Administration accelerated approvals of aducanumab and lecanemab provide the first treatment targeting a key disease mechanism in AD, the accumulation of amyloid plaques, for patients with MCI or mild AD. There are over 50 million people worldwide currently living with dementia mostly due to AD, and this number is expected to double every 20 years8; therefore, additional disease-modifying treatments to prevent or slow progression of this disease remain a significant unmet need.

Growing evidence suggests that aggregated, hyperphosphorylated tau may be a key driver of neurodegeneration in AD. Tau protein is encoded by the microtubule-associated protein tau (MAPT) gene and is a microtubule-associated protein primarily expressed in neurons9. Under pathogenic conditions, hyperphosphorylated tau accumulates intracellularly, aggregating into oligomers and fibrils resulting in intraneuronal neurofibrillary tangles, and is associated with cognitive decline in AD10,11. Tau is also secreted from neurons, spreading through specific neural networks via a trans-synaptic route causing propagation of tau pathology that is associated with further synaptic dysfunction and neuronal loss12–15. Preclinical evidence has demonstrated that tau reduction prevents specific Aβ-mediated deficits, supporting a central role of tau in mediating Aβ toxicity in the early pathogenesis of AD. Intracerebroventricular injection of purified Aβ oligomers into adult rodents has been shown to impair long-term potentiation, and this impairment of long-term potentiation in hippocampal slices of wild-type mice is prevented in tau knockout mice16,17. Evidence from amyloid precursor protein (APP) mouse models of AD have shown that both hetero- and homozygote tau deficiency rescued premature mortality and prevented memory deficits in transgenic mice expressing familial AD mutations in human APP (hAPP), which appeared to be conferred by reduced susceptibility to excitotoxicity in tau knockout mice18,19. In addition, knocking out tau rescued memory impairments, loss of synapses and premature death in hAPP mice expressing human mutant PS1 (ref. 20). Given the important role of tau in AD pathophysiology and the accumulating evidence that lowering tau may reduce this pathological effect, we sought to inhibit MAPT expression and thus reduce tau levels, directly targeting a key disease effector mechanism in patients with AD.

MAPTRx (ISIS 814907/BIIB080) is an antisense oligonucleotide (ASO) designed to reduce concentrations of MAPT messenger RNA. MAPTRx is a chemically modified synthetic oligomer that is complementary to an 18-nucleotide stretch of MAPT pre-mRNA. MAPTRx binds within intron 9 of the MAPT pre-mRNA through Watson–Crick base pairing, with hybridization resulting in endogenous ribonuclease H1-mediated degradation of the MAPT mRNA, inhibiting translation of the tau protein. ASO-mediated selective reduction of MAPT mRNA leads to lowered tau protein levels and sustained amelioration of disease-associated phenotypes in transgenic animal models of tauopathy and hyperexcitability21–24. For example, MAPT mRNA-targeting ASOs in a mouse model of tauopathy resulted in a 50% reduction of endogenous intracellular tau, reduced cell-to-cell spread of oligomerized tau, markedly reduced neuronal and cognitive impairments and was not associated with adverse consequences15. Knockdown of tau in animal models and primary neurons did not impair microtubule assembly, axonal transport or sensory, motor or cognitive behavior tasks22,25,26. Moreover, complete tau knockout mice had normal development and cognition with only a minor motor phenotype developing later in life27–30. These data mitigate potential safety concerns of lowering tau as a therapeutic approach for AD and other tauopathies.

In this study, we aimed to evaluate the safety and pharmacokinetics (PK) of MAPTRx in patients with mild AD and explore the hypothesis that precisely targeted degradation of MAPT mRNA using an ASO would result in lowering of t-tau and phosphorylated tau (p-tau) levels in the central nervous system (CNS). We report the results of a first-in-human phase 1b clinical trial evaluating a tau-targeting ASO administered intrathecally as a bolus in adults with mild AD.

Results

Patients

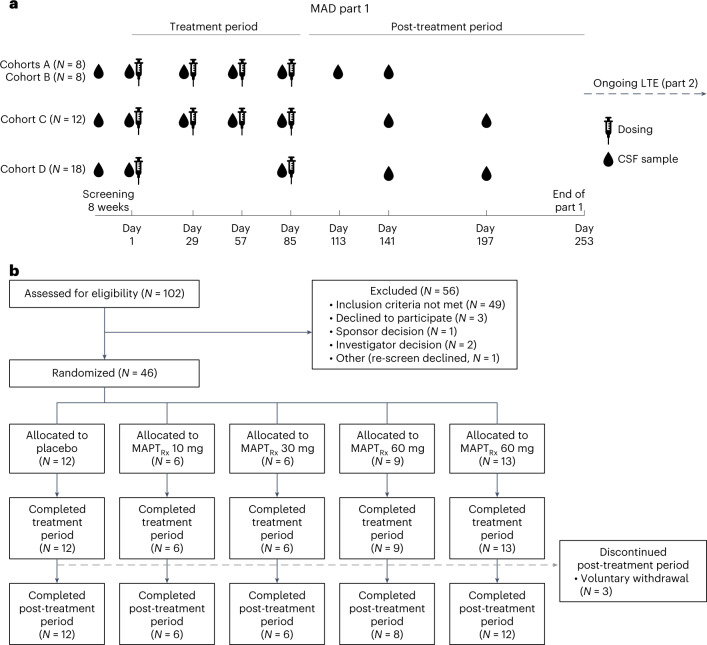

From August 2017 through February 2020, 102 participants were screened for eligibility and 46 underwent randomization according to the protocol (Fig. 1). All participants received all scheduled doses of the study drug (MAPTRx or placebo) during multiple ascending dose (MAD) part 1. Three participants (6.5%) voluntarily withdrew from the study during the post-treatment period: one each from the placebo, 60 mg MAPTRx cohort (four total doses administered monthly) and 115 mg MAPTRx cohort (two total doses administered quarterly). Participants completing MAD part 1 were eligible to participate in the open-label long-term extension (LTE) part 2. Participants randomized to 10 mg or 30 mg MAPTRx (four total doses administered monthly) cohorts experienced a variable gap between completion of the 13 week treatment period of the MAD in part 1 and day 1 of LTE part 2 since the protocol was amended to add the LTE after participants in these cohorts had begun the study. Transition to LTE part 2 was seamless after a 23 week post-treatment period for participants in the 60 mg and 115 mg MAPTRx cohorts.

Fig. 1. Trial design and patient flow diagram.

a, Dosing and CSF sample collection for MAD part 1. CSF samples were obtained before the administration of study drug on days 1, 29, 57 and 85 for cohort A (10 mg MAPTRx or placebo monthly), cohort B (30 mg MAPTRx or placebo monthly) and cohort C (60 mg MAPTRx or placebo monthly) and on days 1 and 85 for cohort D (115 mg MAPTRx or placebo quarterly). The results of CSF samples obtained during screening and on day 1 (baseline) were averaged to serve as the baseline assessment, and the CSF samples on days 29, 57 and 85 served as 28 day, 56 day or 84 day post-dose trough samples. Two CSF samples were obtained in the post-treatment period, on either day 113 or day 141 for cohorts A and B and day 141 and day 197 for cohorts C and D. b, Patient flow during MAD part 1. Eligible patients were randomly assigned in a 3:1 ratio to receive the ASO MAPTRx or placebo in all cohorts.

The characteristics of participants at baseline were representative of relatively younger (mean age of 66 years in both placebo and MAPTRx groups) patients with mild AD and were generally similar across trial groups (Table 1). MAPTRx groups and placebo group had similarly elevated CSF levels of mean t-tau (405.6 ± 132.7 and 387.3 ± 120.9 pg ml−1, respectively) and p-tau181 (40.7 ± 14.2 and 38.7 ± 13.0 pg ml−1, respectively) concentrations at baseline. The mean Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) Sum of Boxes score at baseline was numerically lower for MAPTRx 60 mg and 115 mg treatment groups due to an amendment during the study, which allowed inclusion of participants with a CDR Global Score of 0.5 and Memory Score of 1 in addition to participants with a CDR Global Score of 1.0.

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients at baselinea

| Placebo | MAPTRx | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | (N = 12) | MAPTRx groups (N = 34) | 10 mg monthly (N = 6) | 30 mg monthly (N = 6) | 60 mg monthly Q4W (N = 9) | 115 mg quarterly (N = 13) |

| Age, years | 66 ± 4.6 | 66 ± 6.1 | 64 ± 5.2 | 65 ± 6.1 | 66 ± 6.8 | 67 ± 6.3 |

| Age at diagnosis, years | 65 ± 4.6 | 64 ± 6.4 | 62 ± 5.2 | 64 ± 6.9 | 64 ± 6.6 | 65 ± 6.9 |

| Female, no. (%) | 6 (50) | 17 (50) | 2 (33) | 4 (67) | 5 (56) | 6 (46) |

| Race—white, no. (%) | 12 (100) | 34 (100) | 6 (100) | 6 (100) | 9 (100) | 13 (100) |

| MMSE Total Score | 24.2 ± 1.7 | 23.5 ± 2.4 | 21.5 ± 1.6 | 24.5 ± 1.4 | 24.6 ± 2.5 | 23.2 ± 2.5 |

| RBANS Total Score | 64.9 ± 10.2 | 68.2 ± 12.1 | 58.8 ± 11.2 | 69.2 ± 12.1 | 69.9 ± 9.1 | 70.9 ± 13.4 |

| CDR Global Score, no. (%) | ||||||

| 0.5 | 7 (58) | 23 (68) | 0 (0) | 3 (50) | 9 (100) | 11 (85) |

| 1 | 5 (42) | 11 (32) | 6 (100) | 3 (50) | 0 (0) | 2 (15) |

| CDR Sum of Boxes | 4.1 ± 1.3 | 3.7 ± 1.1 | 4.8 ± 0.5 | 4.7 ± 1.0 | 2.9 ± 0.6 | 3.3 ± 1.1 |

| Concomitant medications, no. (%) | ||||||

| Anticholinesterases | 7 (58) | 21 (62) | 4 (67) | 5 (83) | 4 (44) | 8 (62) |

| Memantine | 1 (8) | 7 (21) | 2 (33) | 0 (0) | 3 (33) | 2 (15) |

| Estrogen replacement | 0 (0) | 3 (9) | 1 (17) | 0 (0) | 1 (11) | 1 (8) |

| APOE4 carrier (%) | 8 (67) | 25 (74) | 5 (83) | 3 (50) | 6 (67) | 11 (85) |

| Homozygous | 2 (16.7) | 8 (23.5) | 2 (33.3) | 0 (0) | 3 (33.3) | 3 (23.1) |

| Heterozygous | 6 (50) | 17 (50) | 3 (50) | 3 (50) | 3 (33.3) | 8 (61.5) |

| CSF t-tau (λpg ml−1) | 387.3 ± 120.9 | 405.6 ± 132.7 | 364.6 ± 98.1 | 386.4 ± 152.3 | 391.0 ± 111.8 | 443.4 ± 153.8 |

| p-tau181 (pg ml−1) | 38.7 ± 13.0 | 40.7 ± 14.2 | 39.1 ± 13.0 | 38.6 ± 16.6 | 39.5 ± 12.6 | 43.2 ± 15.9 |

| t-tau/Aβ42 | 0.6 ± 0.2 | 0.6 ± 0.2 | 0.6 ± 0.2 | 0.6 ± 0.1 | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 0.6 ± 0.2 |

aPlus–minus values are mean ± standard deviation. Patients were assigned to receive either placebo or ascending doses of the ASO MAPTRx. Percentages may not total 100 because of rounding. RBANS, Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status; APOE4, apolipoprotein epsilon 4.

Primary endpoint of safety

Adverse events (AEs) were reported in 94% of participants treated with MAPTRx and 75% of participants treated with placebo; all events were considered mild (88%) or moderate (12%) in severity by investigators (Table 2; for AE incidence and frequency by treatment group, see Extended Data Table 1). A greater percentage of participants receiving MAPTRx experienced mild AEs compared with those receiving placebo; the incidence of moderate AEs was similar.

Table 2.

AEs reported in at least three patients receiving MAPTRx according to severitya

| Event | Mild (grade 1) | Moderate (grade 2) | Severe (grade 3) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MAPTRx groups (N = 34) | Placebo group (N = 12) | MAPTRx groups (N = 34) | Placebo group (N = 12) | MAPTRx groups (N = 34) | Placebo group (N = 12) | |

| Number of patients with event (%) | ||||||

| Any AE (%) | 21 (62) | 5 (42) | 11 (32) | 4 (33) | 0 | 0 |

| Any serious AE | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (16.7) | 0 | 0 |

| Post-LP headacheb | 13 (38) | 1 (8) | 2 (6) | 3 (25) | 0 | 0 |

| Procedural pain | 4 (12) | 1 (8) | 3 (9) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Musculoskeletal pain | 3 (9) | 0 | 1 (3) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Vomiting | 4 (12) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Back pain | 2 (6) | 1 (8) | 1 (3) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Confusional state | 2 (6) | 0 | 1 (3) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Contusion | 1 (3) | 0 | 2 (6) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Diarrhea | 2 (6) | 0 | 1 (3) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Dizziness | 3 (9) | 1 (8) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Fatigue | 3 (9) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Myalgia | 2 (6) | 1 (8) | 1 (3) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Nasopharyngitis | 3 (9) | 2 (17) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Nausea | 3 (9) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Tinnitus | 3 (9) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

aShown are AEs that occurred from the first dose of study drug through the end of MAD part 1 (treatment and post-treatment periods). Each AE was rated as mild, moderate or severe, corresponding to grades of 1, 2 and 3, respectively. In addition, serious AEs were rated as life-threatening (grade 4) or not life-threatening. At each level of summation (overall and according to system organ class or preferred term), patients for whom more than one AE was reported were counted only once for the incidence according to the most severe grade, and if there was a missing severity for the same subject, then the non-missing severity, if available, was chosen for the same subject.

bPost-LP headache indicates both post-LP syndrome and headache that were potentially related to study LP procedure. Related was defined as ‘related’, ‘possible’ or missing relationship to LP procedure.

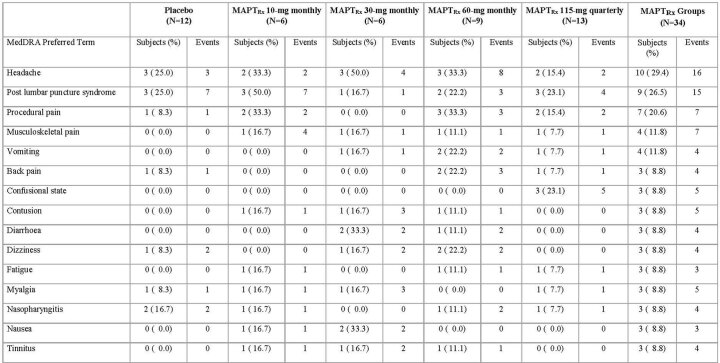

Extended Data Table 1.

Adverse Events Reported in at Least Three Patients* Receiving MAPTRx According to Treatment Group

*Patients reporting more than one adverse event were counted only once for the incidence using the most severe grade and, if there was a missing severity for the same subject, then the non-missing severity, if available, was chosen for the same subject.

**All headache events including those related to lumbar puncture procedure.

The most reported AE in participants treated with MAPTRx was post-lumbar puncture (LP) headache, which was generally considered mild (N = 13); two participants reported post-LP headache considered moderate. Post-LP headache considered potentially related to study procedure occurred after 20% of LPs. There was no evidence of an increased risk of post-LP headache with successive LPs. All post-LP headaches resolved (median duration, <1 day), and no blood patches were required to resolve.

AEs considered potentially related to study drug by Investigators were reported in 15 participants (44%) treated with MAPTRx and no participants treated with placebo. Investigators were blinded to treatment assignment. Most participants (80%) with AEs considered potentially related to study drug experienced mild AEs. Safety magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed 6 months post-baseline, and no clinically meaningful changes were observed on qualitative neuroradiological review. There were no deaths, dose-limiting AEs or discontinuations of dosing regimens during the trial. One participant experienced a delay of approximately 2 months in study drug administration due to coronavirus disease 2019 restrictions.

Two serious AEs occurred in two participants receiving placebo: hospitalization due to diverticulitis and an emergency room visit due to a minor stroke from which both participants recovered. Neither suicidal behavior nor serious suicidal ideation emerged in any participant during the trial. A mildly increased CSF leukocyte count (26–28 cells mm−3, >90% lymphocytes) without any associated symptoms was observed in one participant, a 64-year-old female, 16 weeks after administration of the second MAPTRx 115 mg dose; MRI with contrast and electroencephalographic results were normal. The participant did not transition to the LTE, but follow-up safety MRI and CSF collection performed post-MAD part 1 completion showed that the pleocytosis had completely resolved (5 months after initial finding). Two participants receiving quarterly 115 mg MAPTRx experienced mild confusional state and restlessness 1–2 days after their first and second doses, which resolved within 2–4 days of onset. Both participants had a medical history of anxiety and were treated with psychotropic medications before their enrollment in the study.

Secondary endpoint

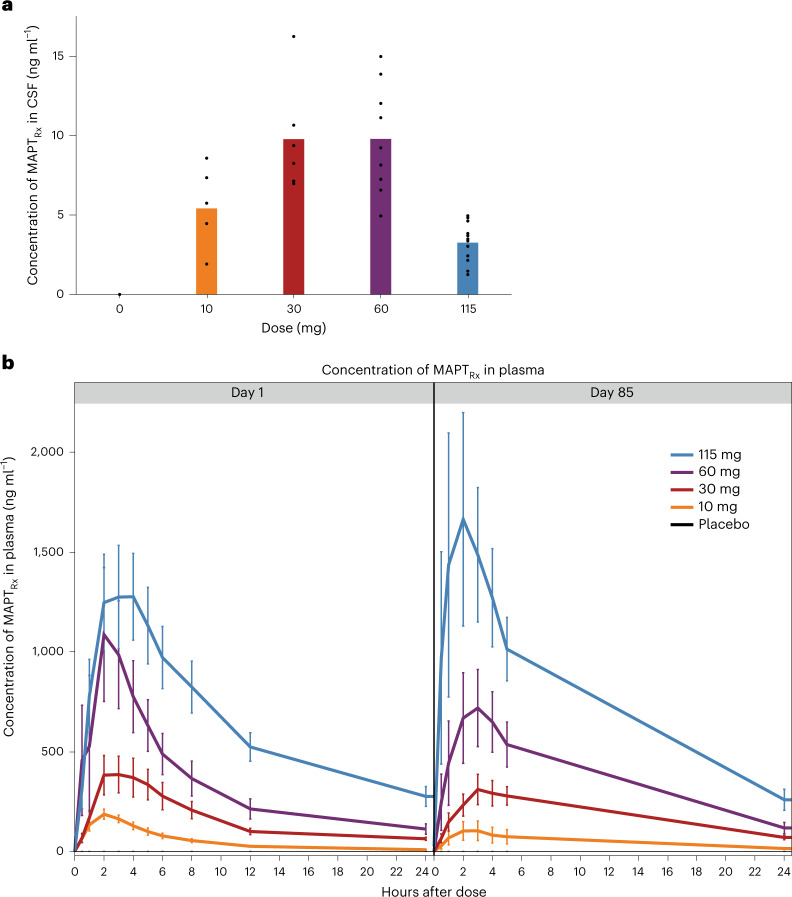

MAPTRx was measurable in the CSF in all participants receiving MAPTRx (Fig. 2a). Pre-dose or trough concentrations increased from the 10 mg monthly dose to those observed at the 30 mg and 60 mg monthly doses. Similar trough CSF concentrations were observed after the 30 and 60 mg monthly doses. It is unclear why there is no apparent difference in MAPTRx CSF trough concentration between the 30 mg and 60 mg MAPTRx groups. Only six participants in each group received 30 mg or 60 mg MAPTRx, and CSF is not a well-mixed compartment with variable results observed previously31. The lowest mean trough CSF concentrations observed after the initial 115 mg quarterly dose were expected considering the longer time for elimination between MAPTRx doses and sample collection (84 days versus 28 days). Mean trough MAPTRx concentrations in CSF generally increased during the treatment period in all dose groups probably due to the slow clearance and long elimination half-life of MAPTRx relative to the dosing interval. The increase over time was less in the 115 mg quarterly cohort compared with the cohorts dosed every month.

Fig. 2. MAPTRx exposure in CSF and plasma.

a, The maximum pre-dose CSF concentration of MAPTRx according to dose group: placebo or the various MAPTRx dose groups (that is, day 28 ‘trough’ (pre-dose) for placebo, 10 mg (n = 6 patients), 30 mg (n = 6 patients) and 60 mg (n = 9 patients) monthly groups; day 84 trough for 115 mg (n = 12 patients) quarterly dose group). Bar represents mean value and points represent individual values. b, Mean ± standard error of the mean concentration of MAPTRx in plasma, according to dose group, over the 24 h periods after the administration of the first dose (left; day 1) and fourth dose for 10 mg (n = 6 patients; all timepoints), 30 mg (n = 6 patients (n = 5 patients at 4 h and 5 h after dose on day 1 and 3 h after dose on day 85)) and 60 mg (n = 9 patients (n = 8 patients at 1 h after dose on day 1)) monthly dose groups and second dose for 115 mg (n = 13 patients on day 1, n = 12 patients on day 85) quarterly dose group (right; day 85). Error bars indicate the standard error.

Exploratory endpoints

Plasma concentrations of MAPTRx

The median peak plasma concentrations of MAPTRx were achieved within 4 h after intrathecal (IT) administration and declined to less than 30% of the peak concentration by 24 h after administration. The concentration of MAPTRx in plasma increased approximately proportionally to the dose over the explored dose range (Fig. 2b). There was no evidence of accumulation of concentration in plasma 24 h after dose administration over the course of the trial, and there was a minor increase (<20%) in the peak concentration at the 115 mg dose level.

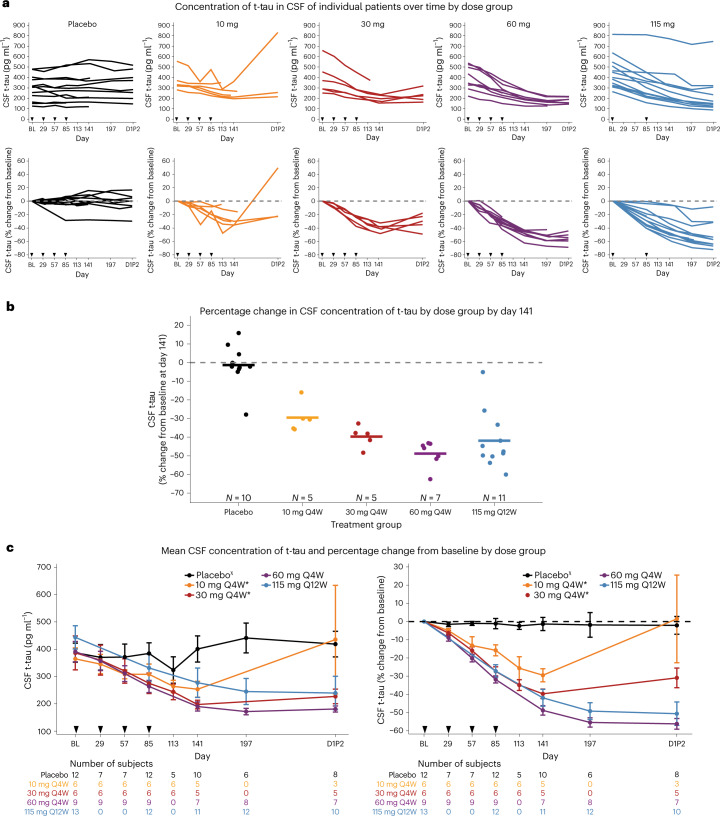

Concentration of t-tau in CSF

In participants receiving MAPTRx, there were dose-dependent decreases in the concentration of t-tau in CSF. Steady-state maximal reduction of the concentration of CSF t-tau was not reached during the 13 week treatment period, and t-tau concentrations continued to decline during the post-treatment period (Fig. 3a). The mean percentage change from baseline in t-tau concentration at 8 weeks post-last dose was −30%, −40%, −49% and −42% in MAPTRx 10 mg, 30 mg and 60 mg monthly and 115 mg quarterly groups, respectively (Fig. 3b). In the higher-dose groups with seamless entry into the LTE, CSF t-tau continued to decline at 24 weeks (day 1 LTE part 2) post-last dose in the 60 mg monthly (N = 7) and 115 mg quarterly (N = 10) MAPTRx groups (−56% and −51% mean percentage change from baseline, respectively; Fig. 3c). The 60 mg and 115 mg MAPTRx groups received almost identical cumulative doses of 240 mg and 230 mg, respectively, over the 13 week treatment period, which may account for the similar t-tau reduction observed in both groups. Participants randomized to 10 mg and 30 mg MAPTRx monthly groups had a variable gap between completing MAD part 1 and starting LTE part 2; the duration between the last dose in MAD part 1 and CSF collection before the first dose in LTE part 2 ranged from 22 to 28 months for the 10 mg group and from 10 to 16 months for the 30 mg group. Despite the prolonged gap, a durable reduction in t-tau concentration was observed in the 30 mg MAPTRx group (−31% mean percentage change from baseline; N = 5) on day 1 of the LTE. T-tau levels had returned to baseline levels in the 10 mg MAPTRx group (N = 3). In participants receiving placebo, the mean percentage change from baseline ranged from −1% to −2.4% among all post-baseline visits (Fig. 3c).

Fig. 3. Effect of MAPTRx on CSF concentrations of t-tau protein.

a, The concentrations of t-tau in CSF over time for individual patients in each dose group; absolute values, measured in picograms per milliliter (pg ml−1), are shown in the top graphs, and the percentage changes from baseline are shown in the bottom graphs. Arrowheads indicate the days on which MAPTRx or placebo was administered. b, The percentage change in the concentration of t-tau in CSF from baseline to the timepoint 56 days after the last dose (day 141). Circles indicate individual patients, and horizontal lines indicate group means. c, The mean concentration of t-tau in CSF (left) and the mean percentage change from baseline (right) over time according to dose group. CSF was not collected at 16 weeks post-last dose (day 197) for the 10 mg and 30 mg groups. Error bars indicate the standard error of the mean. Q4W and Q12W indicates dosing every 4 or 12 weeks, respectively. *Participants assigned to cohort A or B did not seamlessly transition to LTE part 2 and experienced a variable gap ranging from 5 to 19 months between completion of MAD part 1 at day 253 and start of LTE part 2 (D1P2). χPlacebo group was pooled. Subjects assigned to cohorts A or B and randomized to placebo had a variable gap between completion of MAD part 1 and start of LTE part 2 (D1P2).

Additional exploratory outcomes

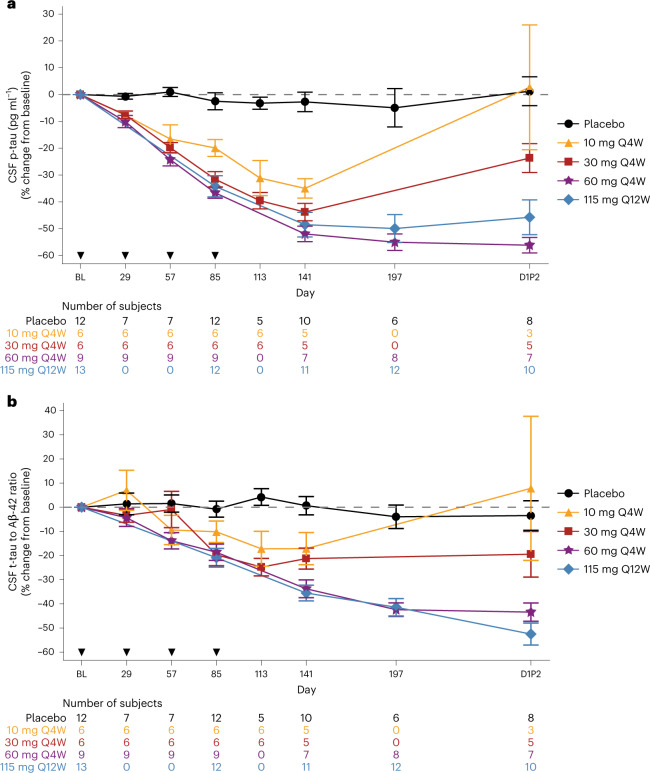

Reductions similar to those observed for t-tau were observed for p-tau181 concentration and the ratio of t-tau to Aβ42 in CSF (Fig. 4). In participants receiving MAPTRx, there were dose-dependent decreases in the concentration of p-tau181 in CSF 8 weeks post-last dose with mean percentage change from baseline of −35%, −44%, −52% and −49% in MAPTRx 10 mg, 30 mg and 60 mg monthly and 115 mg quarterly groups, respectively. CSF p-tau181 continued to decline in participants treated with MAPTRx in 60 mg monthly and 115 mg quarterly groups 24 weeks (day 1 LTE part 2) post-last dose with mean percentage change from baseline of −56% and −46%, respectively.

Fig. 4. Effect of MAPTRx on CSF concentrations of p-tau protein and tau/Aβ42.

a, The mean percentage change from baseline in p-tau over time according to dose group. b, The mean percentage change from baseline in the ratio of t-tau to Aβ42 over time according to dose group. Error bars indicate the standard error of the mean. Q4W and Q12W indicates dosing every 4 or 12 weeks, respectively. *Participants assigned to cohort A or B did not seamlessly transition to LTE part 2 and experienced a variable gap ranging from 5 to 19 months between completion of MAD part 1 at day 253 and start of LTE part 2 (D1P2). χPlacebo group was pooled. Subjects assigned to cohorts A or B and randomized to placebo had a variable gap between completion of MAD part 1 and start of LTE part 2 (D1P2).

Performance on functional, cognitive, psychiatric and neurologic clinical outcomes slightly declined as expected for participants with mild AD over the duration of the treatment and post-treatment periods. While no consistent trends were observed across change from baseline on clinical endpoints, further analyses are ongoing to better understand the longitudinal trajectory of the clinical assessments and the relationship with drug exposure and pharmacodynamic (PD) effects. Exploratory CSF parameters including neurofilament light (NfL) and heavy (NfH), neurogranin (NRGN) and YKL-40 showed no dose-responsive effects at 8 weeks post-last dose of MAPTRx (Supplementary Table 1). CSF NfL levels decreased from baseline in the placebo and 10 mg MAPTRx groups, and a slight increase from baseline was observed in the 30, 60 and 115 mg MAPTRx groups. All groups experienced a slight increase from baseline in CSF NfH with the 30 mg MAPTRx group experiencing the greatest increases in both NfL and NfH. Decrease from baseline in CSF YKL40 was observed in all MAPTRx treatment groups, whereas no change from baseline was observed in the placebo group. CSF NRGN levels decreased from baseline in the 10, 30 and 60 mg MAPTRx groups, and no change from baseline was observed in the placebo or 115 mg MAPTRx groups.

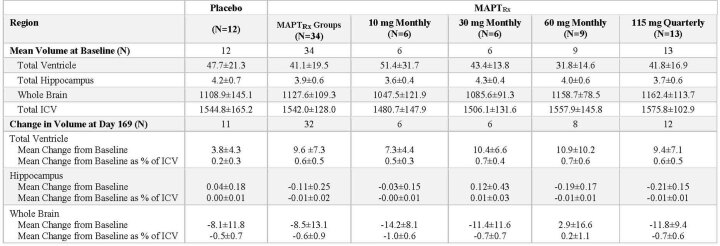

The mean change from baseline in ventricular volume (VV) as a percentage of total intracranial volume 6 months post-baseline was greater in the 10 mg, 30 mg, 60 mg and 115 mg MAPTRx dose groups (0.5%, 0.7%, 0.7% and 0.6%, respectively) than that observed in the placebo group (0.2%; Extended Data Table 2). Ventricular enlargement (VE) was not observed in qualitative neuroradiological review of safety MRIs from participants in MAPTRx or placebo groups. Clinical findings potentially associated with VE were not observed during the treatment or post-treatment periods. Whole-brain volume declined slightly from baseline in all groups and did not differ between participants who received placebo and those who received MAPTRx.

Extended Data Table 2.

Ventricle, Hippocampus and Whole Brain Volumes*

* Volume measured in cm3. Plus–minus values are means ± SD.

ICV: Intracranial Volume (cm3)

Discussion

In this first in human phase 1b study, bolus IT administrations of four monthly doses of MAPTRx at 10 mg, 30 mg and 60 mg or two quarterly doses at 115 mg to adults with mild AD were not accompanied by any severe or serious AEs during the 13 week treatment period or 23 week post-treatment period. The proportion of participants experiencing AEs was greater in those receiving MAPTRx versus placebo (94% versus 75%, respectively), and this was mainly due to an increased incidence of mild AEs in the MAPTRx treatment group (62% versus 42% in placebo). AEs considered potentially related to study drug by investigators were reported more frequently in with MAPTRx-treated participants compared with placebo-treated participants (15 (44%) versus 0, respectively). The most reported AE in participants receiving MAPTRx was post-LP headache, which was generally mild in severity. All study participants were white, and it will be important in larger, later-phase clinical studies of MAPTRx to include a diverse patient population to adequately evaluate both efficacy and safety. Overall MAPTRx treatment was generally well tolerated, with all participants completing the treatment period and over 90% of participants completing the post-treatment period.

MAPTRx administration resulted in dose- and time-dependent reduction in the concentration of CSF t-tau and p-tau181 with approximately 50% mean reduction from baseline observed 24 weeks post-last dose. Further characterization of MAPTRx PK and PD data from the LTE will be important for selection of the optimal dose level and frequency for future clinical studies. It is not feasible to directly quantify the reduction of MAPT mRNA or tau protein in cortical tissue in a clinical trial; however, it is possible to index PD activity with CSF protein assays31,32. Tau is a long-lived protein in the CNS, and thus CSF tau in this study will be a lagging indicator of the reduction of MAPT mRNA and newly synthesized tau in the CNS33. The predicted MAPTRx concentrations in brain tissue at all dose levels in this study are sufficient to provide >50% reduction in t-tau production in the cerebral cortex31. Therefore, it is not surprising that all doses assessed in this study demonstrated a similar trajectory of CSF tau lowering (Figs. 3 and 4), a trajectory that probably reflects potent reductions in new tau synthesis at all doses with a rate-limiting condition of the elimination of existing tau protein. Many of the tau-targeting antibody and vaccine approaches currently in development aim to reduce spread of specific extracellular tau species and are not predicted to have a major impact on intracellular p-tau34. MAPTRx prevents tau protein production, and should lower the levels of all tau species and subsequent posttranslational modifications with the potential to reduce both pathological spreading of extracellular tau and neuronal dysfunction due to intracellular tau accumulation.

Limitations of evaluating CSF t-tau and p-tau to index target engagement include the clearance of existing tau protein and reliance on tau transport to the CSF. Physiological and pathological conditions may impact the rate of synthesis of tau, passive and active release into the extracellular space, and the clearance of tau including degradation by microglia33,35,36. At baseline, CSF tau represents previously synthesized tau. However, at steady state with respect to both ASO distribution and the production and elimination of tau, lowered CSF tau levels should index the reduction of newly synthesized tau21,22,37. In the ongoing LTE, steady-state reductions in CSF t-tau protein levels should emerge that reflect the degree to which newly synthesized tau protein is reduced in the CNS. While measuring CSF tau protein can index PD activity, it cannot inform on regional differences in MAPT mRNA reduction in CNS tissues.

Quantitative assessment of VV showed greater increases in MAPTRx treatment groups compared with placebo. Importantly, VE was not evident on qualitative neuroradiological review of safety MRI scans, and there were no clinical correlates. Quantitative increases in VV have been observed in treatment groups relative to placebo in clinical studies of patients with AD38–41 while other clinical studies of AD have not reported treatment related- increases42–45. The etiology of greater quantitative VE relative to placebo in these studies remains unclear, and associated changes in clinical outcomes were generally not reported in these studies. Slow, progressive whole-brain atrophy (that is, irreversible loss of brain tissue) and VE are characteristic features of AD46,47, and neuroinflammation is a known phenomenon in AD48. Although ‘pseudoatrophy’ (that is, VE due to resolution of inflammatory edema and gliosis) has been described in clinical studies of multiple sclerosis and AD, it has been challenging to differentiate between treatment-induced pseudoatrophy and disease-related atrophy38,39,42,49–51. There were no apparent differences in whole brain volume in MAPTRx treatment groups versus placebo group in this study. Further work is needed to assess the effect of MAPTRx treatment on inflammation or gliosis in humans or animal models. Comparing the rate of VE observed in our study with that observed in the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative is challenging since our patient population was younger (mean age 66 years versus 75 years in the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative)46,47,52. Nearly half of the participants in our study were diagnosed before age 65, representing a much higher proportion of participants with early onset AD compared with the general AD population (46% versus 5%). Disease severity, age and genetic status may influence the degree and rate of increase in VV and requires further evaluation in future studies of the drug.

MAPTRx is the first ASO treatment evaluated in a clinical study of patients with AD. The results from this first in human study demonstrate that MAPTRx engaged its target, as evidenced by the marked dose-dependent and sustained reductions in the concentration of CSF t-tau, and had an acceptable safety profile in participants with mild AD. Intrathecally administered ASOs have been evaluated in other neurodegenerative diseases including spinal muscular atrophy, Huntington’s disease and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis with mixed results53–55. Nusinersen is indicated for the treatment of children and adults with spinal muscular atrophy56. While the results of a large phase 3 study of tominersen in patients with more advanced Huntington’s disease did not show evidence of clinical improvement, post hoc exploratory subgroup analysis investigating the association between disease burden and ASO exposure suggests that younger participants with a lower disease burden might derive benefit from less frequent or lower-dose treatment with tominersen in contrast to the other subgroups57. The tominersen program continues with a new phase 2 clinical trial exploring different doses of the ASO in younger patients with lower disease burden (EudraCT number 2022-001991-32). Results of a phase 3 study of tofersen treatment in patients with SOD1 amyotrophic lateral sclerosis did not achieve statistically significant improvements on clinical endpoints, but trends favoring tofersen were observed across clinical outcome measures of respiratory function, muscle strength and quality of life during the 28 week treatment period with further improvement evolving during the open-label extension, including clinical endpoints at week 52. Importantly, robust lowering of CSF SOD1 protein and plasma NfL chains, a marker of axonal injury and neurodegeneration, were observed53. Tofersen is currently under US Food and Drug Administration and European Medicines Agency review with approval decisions expected in 2023. Treatment of neurodegenerative diseases with ASOs is still in its infancy, and learnings from recent studies on dose level and frequency as well as trial design (treatment duration, sample size and patient selection) will further improve ASO development and clinical trial designs across neurodegenerative diseases.

This first-in-human study of MAPTRx has several limitations mainly due to its small size (N = 46) as is typical of phase 1 studies. The MAPTRx doses evaluated in this study achieved the target t-tau reduction of ~50%, but determining whether this reduction is efficacious will require further evaluation in larger, well-controlled trials. Similarly, MAPTRx-treatment related effects on exploratory biomarkers will require further evaluation in larger trials. Changes in NfL, Nfh, YKL40 and NRGN levels did not appear to be dose responsive and were not concordant, but interpretation of the clinical meaningfulness of these results is limited due to the combination of assay variability and small sample size. Lastly, this study was conducted in relatively young participants with mild AD, and it will be important that future studies of MAPTRx evaluate safety and efficacy in an older population, which may be more representative of late-onset AD. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 2 study of BIIB080 (MAPTRx) is currently underway and includes patients aged 50–80 years with an estimated enrollment of over 700 participants with MCI due to AD or mild AD (Clinicaltrials.gov registration number NCT05399888).

These results demonstrate that antisense-mediated suppression of tau protein synthesis in the CNS of participants with mild AD is possible and warrant further evaluation of the effect of MAPTRx on the clinical course of patients with AD and in other tauopathies.

Methods

Study design and participants

In this randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter, MAD phase 1b trial with an open-label LTE, we evaluated the safety, PK and target engagement of MAPTRx in participants with mild AD. This study was divided into two parts: MAD part 1, was completed in September 2020, and LTE part 2 was completed in May 2022. Participants had the option to enroll in the open-label LTE upon completion of MAD part 1.

Eligible participants were between the ages of 50 and 74 years and had mild AD, defined by a CDR58 Overall Global Score of 1 or Global Score of 0.5 with a Memory Score of 1, Mini-Mental State Examination score (MMSE59) of 20–27 inclusive (scores range from 0 to 30, 20–27 may represent mild AD); CSF pattern of low Aβ42 and elevated t-tau and p-tau consistent with diagnosis of AD; and diagnosis of probable AD based on National Institute of Aging-Alzheimer Association criteria60 (for further details, see Supplementary Information).

MAD part 1 was conducted at 12 centers in Canada, Finland, Germany, the United Kingdom, the Netherlands and Sweden. A centralized automated randomization system assigned participants 3:1 to receive bolus IT injections of MAPTRx or placebo (artificial CSF) within each of four dose cohorts during the 13 week treatment period: cohort A, 10 mg monthly, cohort B 30 mg monthly or cohort C, 60 mg monthly (total of four doses each); or cohort D, 115 mg quarterly (total of two doses). Twenty milliliters of CSF were removed before administration of 20 ml of study drug. There was a 23 week post-treatment period during which no study drug was administered. Participants assigned to cohort A or B did not seamlessly transition to LTE part 2 and experienced a variable gap ranging from 5 to 19 months between completion of MAD part 1 at day 253 and registration for LTE part 2. Participants assigned to cohort C or D seamlessly transitioned to LTE part 2. CSF samples were obtained before each administration of study drug (MAPTRx or placebo), 4 and 8 weeks post-last dose for cohorts A and B, and 8 and 16 weeks post-last dose for cohorts C and D (Fig. 1). Investigators, participants and the sponsor were blinded to trial-group assignments for the trial duration.

The primary objective was evaluation of the safety of MAPTRx. Safety evaluations included collection of AEs, physical and neurologic examination, Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale, laboratory assessments, vital signs, electrocardiograms and safety MRI sequences. At each trial visit, participants were queried for other changes in health status and concomitant medications in an open-ended fashion.

The secondary endpoint was the characterization of the PK of MAPTRx in CSF.

The key exploratory endpoint was CSF t-tau concentration. Additional exploratory endpoints included characterization of MAPTRx PK in plasma; exploration of the effects of MAPTRx on PD biomarkers including CSF concentrations of p-tau, Aβ42 and NfL; and clinical, cognitive and neuroimaging assessments relevant to AD (Supplementary Table 1).

Study drug

MAPTRx is a second-generation 2′-O-(2-methoxyethyl) ASO complementary to a nucleotide sequence in the human MAPT pre-mRNA transcript. The sequence of MAPTRx is (5′ to 3′) ccogttTTCTTACCacocct, where capital letters represent 2′-deoxyribose nucleosides, and small letters 2′-(2-methoxyethyl)ribose nucleosides. Nucleoside linkages represented with a subscript o are phosphodiester, and all others are phosphorothioate. Letters represent adenine, 5-methylcytosine, guanine and thymine nucleobases. Hybridization of MAPTRx to the cognate pre-mRNA via Watson and Crick base pairing results in ribonuclease H1-mediated degradation of the MAPT pre-mRNA, thus selectively preventing production of the tau protein61. Dose selection was guided by a preclinical model in mouse and monkey relating dose level to reduction in MAPT mRNA (model described by Tabrizi et al.31).

Study oversight

The trial was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The trial protocol and all documentation were approved by the institutional review board or independent ethics committee at each investigational site (for list of ethics committees approving the study, see Supplementary Information). All participants provided written informed consent. The trial was sponsored by Ionis Pharmaceuticals, which provided the study drug (MAPTRx and placebo). Personnel from Ionis Pharmaceuticals designed the trial in conjunction with collaborators from Biogen, academic investigators and other disease experts. A Formal Safety Monitoring Group, composed of sponsor personnel with medical and clinical trial expertise and independent from the conduct of the study, authorized each dose escalation after unblinded review of safety data. The investigators collected the data, which were held and maintained by the sponsor. Data were analyzed by personnel from the sponsor and were interpreted by all authors. The investigators vouch for the fidelity of the trial to the protocol and protocol amendments. The authors vouch for the completeness and accuracy of the data. The authors and sponsor made the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Measurement of brain volumes

We obtained three-dimensional T1-weighted structural MRI scans of the head and transferred these data, blinded to trial-group status, to an independent image-analysis provider that performed quality control, processing and volumetric analyses according to established methods. Whole-brain and regional volume changes were calculated using a validated pipeline implemented in VivoQuantTM, composed of a preprocessing module and a multi-atlas segmentation module, followed by visual inspection and manual editing if needed62.

Biomarker analysis

CSF from participants was analyzed with the following assays: Elecsys β-Amyloid (1-42) CSF, Elecsys Total-Tau CSF and Elecsys Phospho-Tau (181P) CSF performed at Roche Diagnostics); NfL (Uman), NfH (Protein Simple, ELLA), YKL40 (Protein Simple, ELLA) and NRGN (Euroimmune) at Immunologix.

Statistical analysis

The primary objective of the trial was the evaluation of the safety of MAPTRx treatment. Safety data were summarized according to treatment group. Quantitative assessments were summarized using descriptive statistics including number of patients, mean, median, standard deviation, standard error of mean, interquartile range (25th percentile, 75th percentile) and range (minimum, maximum). Qualitative assessments were summarized using frequency counts and percentages. All safety analyses were performed in the safety population (all randomized participants receiving at least one dose of study drug). PK parameters were assessed for MAPTRx in CSF and plasma. Analyses of PD biomarkers and exploratory and clinical endpoints were summarized according to treatment group, and MAPTRx -treated groups were compared with the pooled placebo group. While there is no statistical rationale for the sample size, it has been selected on the basis of prior experience with generation 2.0 ASOs31 given by IT bolus injection to ensure that the safety, tolerability, PK and exploratory pharmacodynamics will be adequately assessed while minimizing unnecessary patient exposure. Statistical analyses were performed using Statistical Analysis System (SAS) Version 9.4.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Online content

Any methods, additional references, Nature Portfolio reporting summaries, source data, extended data, supplementary information, acknowledgements, peer review information; details of author contributions and competing interests; and statements of data and code availability are available at 10.1038/s41591-023-02326-3.

Supplementary information

Supplementary clinical study information.

Acknowledgements

We thank the participants and their companions who participated in the study; the sites, study teams from Ionis Pharmaceuticals, Biogen and Syneos for executing the study; N. Fox and I. Malone (University College London Dementia Research Centre, London, UK) for their collaboration on analyses and interpretation of the MRI volumetric data; and J. Matthews (Ionis) and J. Allison (Immunologix, Tampa, FL) for exploratory biomarker analysis support. The study was funded by Ionis Pharmaceuticals and Biogen.

Extended data

Author contributions

C.J.M. was the lead investigator and performed data collection, data interpretation, participant recruitment and writing/critical review of the manuscript. A.B.-H., D.J.B., E.G.B.V., P.P.D., S.D., M.J., A.S., J.O.R., A.C.L. and B.R. performed data collection, data interpretation, participant recruitment and critical review of the manuscript. H.K., E.E.S. and B.F. carried out data analysis and interpretation and critical review of the manuscript. L.M. oversaw study design, data collection, data interpretation and participant recruitment and performed critical review of the manuscript. K.M.M. performed data collection, data interpretation, data analysis and writing of the manuscript. C.Y. performed clinical operations and critical review of the manuscript. T.B. was responsible for regulatory oversight and performed data interpretation and critical review of the manuscript. D.L. performed statistical analysis plan design, data collection, data analysis and data interpretation. D.A.N. performed data analysis, data interpretation and writing and critical review of the manuscript. R.C. performed data analysis/interpretation and critical review of the manuscript. D.L.G., E.H. and E.R. performed data analysis/interpretation and critical review of the manuscript. C.F.B. performed data interpretation and critical review of the manuscript. C.J. oversaw study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation and writing of the manuscript. R.M.L. was responsible for study design and data interpretation and performed writing and critical review of the manuscript.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Medicine thanks Gil Rabinovici, Gina Mazza and the other, anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling editor: Jerome Staal, in collaboration with the Nature Medicine team.

Data availability

To request access to data, please visit Vivli. The individual participant data collected during the trial and that support the research proposal will be available to qualified scientific researchers, in accordance with Biogen’s Clinical Trial Transparency and Data Sharing Policy on www.biogentrialtransparency.com. Data requests are initially reviewed by Vivli and Biogen for completeness and other parameters (relating to scope and meeting sponsor policies) and are then reviewed by an Independent Review Panel. Deidentified data, study protocol and documents will be shared under agreements that further protect against participant reidentification, and data are provided in a secure research environment further protecting participant privacy.

Competing interests

C.J.M. reports advisory board membership for Roche, Lilly, Biogen and Ionis; research grants from Biogen; seminar chair for Biogen; chair of data safety monitoring board for AD trial led by Imperial College; supported by the NIHR Biomedical Research Centre dementia subtheme at UCLH. M.J. reports advisory board membership for Biogen Sweden AB and BioArctic AB. S.D. reports salary support from the Fonds de recherche du Québec – Santé; consultancies from Biogen, Wave Life Sciences, AZTherapies and Janssen Pharmaceuticals; advisory board membership and/or speaker fees from Eisai, Biogen, Sunovion, Innodem Neurosciences, HealthTech Connex and QurAlis; cofounder of AFX Medical Inc. E.G.B.V. reports consultancies from New Amsterdam Pharma, Treeway, ReMynd, Vivoryon, Biogen, Vigil Neuroscience, ImmunoBrain Checkpoint and Brainstorm Therapeutics. PI of studies with AC immune, CogRX therapeutics, New Amsterdam Pharma, Janssen, UCB, Roche, GreenValley, Vivoryon, ImmunoBrain, Alector and Alzheon and sub-I from DIAN-TU, Alzheon, Eli Lilly, Cortexyme, Biogen en Fuij Film Toyama. L.M., K.M.M., C.Y., D.L., D.A.N., R.C., C.F.B., C.J. and R.M.L. are employees of, and hold stock in, Ionis. D.L.G., E.H. and E.R. are employees of, and hold stock in, Biogen. The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors jointly supervised this work: Catherine J. Mummery, Anne Börjesson-Hanson, Daniel J. Blackburn, Everard G. B. Vijverberg, Peter Paul De Deyn, Simon Ducharme, Michael Jonsson, Anja Schneider, Juha O. Rinne, Albert C. Ludolph, Ralf, Bodenschatz, Laurence Mignon, Candice Junge, Roger M. Lane.

These authors contributed equally: Holly Kordasiewicz, Eric E. Swayze, Bethany Fitzsimmons, Laurence Mignon, Katrina M. Moore, Chris Yun, Tiffany Baumann, Dan Li, Daniel A. Norris, Rebecca Crean, Danielle L. Graham, Ellen Huang, Elena Ratti, C. Frank Bennett.

Change history

10/16/2023

A Correction to this paper has been published: 10.1038/s41591-023-02639-3

Extended data

is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41591-023-02326-3.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41591-023-02326-3.

References

- 1.Lane CA, Hardy J, Schott JM. Alzheimer’s disease. Eur. J. Neurol. 2018;25:59–70. doi: 10.1111/ene.13439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.2021 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement.17, 327–406 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.2020 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement.10.1002/alz.12068 (2020).

- 4.McKhann GM, et al. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7:263–269. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shaw LM, et al. Appropriate use criteria for lumbar puncture and cerebrospinal fluid testing in the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2018;14:1505–1521. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2018.07.220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jack CR, Jr., et al. NIA-AA Research Framework: toward a biological definition of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2018;14:535–562. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2018.02.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Braak H, Thal DR, Ghebremedhin E, Del Tredici K. Stages of the pathologic process in Alzheimer disease: age categories from 1 to 100 years. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2011;70:960–969. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e318232a379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alzheimer’s Disease International, G.M., Prince M, Prina M. Numbers of people with dementia worldwide. An update to the estimates in the World Alzheimer Report 2015. Alzheimer’s Disease Internationalhttps://www.alzint.org/resource/numbers-of-people-with-dementia-worldwide/ (2020).

- 9.Dixit R, Ross JL, Goldman YE, Holzbaur ELF. Differential regulation of dynein and kinesin motor proteins by tau. Science. 2008;319:1086–1089. doi: 10.1126/science.1152993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hanseeuw BJ, et al. Association of amyloid and tau with cognition in preclinical Alzheimer disease: a longitudinal study. JAMA Neurol. 2019;76:915–924. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2019.1424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xia C, et al. Association of in vivo [18F]AV-1451 tau PET imaging results with cortical atrophy and symptoms in typical and atypical Alzheimer disease. JAMA Neurol. 2017;74:427–436. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2016.5755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DeVos SL, et al. Synaptic tau seeding precedes tau pathology in human Alzheimer’s disease brain. Front. Neurosci. 2018;12:267. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2018.00267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wu JW, et al. Small misfolded tau species are internalized via bulk endocytosis and anterogradely and retrogradely transported in neurons. J. Biol. Chem. 2013;288:1856–1870. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.394528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Calafate S, et al. Synaptic contacts enhance cell-to-cell tau pathology propagation. Cell Rep. 2015;11:1176–1183. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.04.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Takeda S, et al. Neuronal uptake and propagation of a rare phosphorylated high-molecular-weight tau derived from Alzheimer’s disease brain. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:8490. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shipton OA, et al. Tau protein is required for amyloid β-induced impairment of hippocampal long-term potentiation. J. Neurosci. 2011;31:1688–1692. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2610-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Walsh DM, et al. Naturally secreted oligomers of amyloid β protein potently inhibit hippocampal long-term potentiation in vivo. Nature. 2002;416:535–539. doi: 10.1038/416535a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roberson ED, et al. Reducing endogenous tau ameliorates amyloid β-induced deficits in an Alzheimer’s disease mouse model. Science. 2007;316:750–754. doi: 10.1126/science.1141736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ittner LM, et al. Dendritic function of tau mediates amyloid-β toxicity in Alzheimer’s disease mouse models. Cell. 2010;142:387–397. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.06.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leroy K, et al. Lack of tau proteins rescues neuronal cell death and decreases amyloidogenic processing of APP in APP/PS1 mice. Am. J. Pathol. 2012;181:1928–1940. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2012.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.DeVos SL, et al. Tau reduction prevents neuronal loss and reverses pathological tau deposition and seeding in mice with tauopathy. Sci. Transl. Med. 2017;9:eaag0481. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aag0481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.DeVos SL, et al. Antisense reduction of tau in adult mice protects against seizures. J. Neurosci. 2013;33:12887–12897. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2107-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sud R, Geller ET, Schellenberg GD. Antisense-mediated exon skipping decreases tau protein expression: a potential therapy for tauopathies. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids. 2014;3:e180. doi: 10.1038/mtna.2014.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schoch MK, et al. Increased 4R-tau induces pathological changes in a human-tau mouse model. Neuron. 2016;90:941–947. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2016.04.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vossel KA, et al. Tau reduction prevents Aβ-induced defects in axonal transport. Science. 2010;330:198. doi: 10.1126/science.1194653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Qiang L, Yu W, Andreadis A, Luo M, Baas PW. Tau protects microtubules in the axon from severing by katanin. J. Neurosci. 2006;26:3120–3129. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5392-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dawson HN, et al. Inhibition of neuronal maturation in primary hippocampal neurons from tau deficient mice. J. Cell Sci. 2001;114:1179–1187. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.6.1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fujio K, et al. 14-3-3 proteins and protein phosphatases are not reduced in tau-deficient mice. NeuroReport. 2007;18:1049–1052. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e32818b2a0b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Morris M, et al. Age-appropriate cognition and subtle dopamine-independent motor deficits in aged tau knockout mice. Neurobiol. Aging. 2013;34:1523–1529. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2012.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li Z, Hall AM, Kelinske M, Roberson ED. Seizure resistance without parkinsonism in aged mice after tau reduction. Neurobiol. Aging. 2014;35:2617–2624. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2014.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tabrizi SJ, et al. Targeting Huntingtin expression in patients with Huntington’s disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019;380:2307–2316. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1900907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miller T, et al. Phase 1–2 trial of antisense oligonucleotide tofersen for SOD1 ALS. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;383:109–119. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2003715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sato C, et al. Tau kinetics in neurons and the human central nervous system. Neuron. 2018;98:861–864. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2018.04.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sandusky-Beltran LA, Sigurdsson EM. Tau immunotherapies: lessons learned, current status and future considerations. Neuropharmacology. 2020;175:108104. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2020.108104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Luo W, et al. Microglial internalization and degradation of pathological tau is enhanced by an anti-tau monoclonal antibody. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:11161. doi: 10.1038/srep11161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yamada K, et al. Analysis of in vivo turnover of tau in a mouse model of tauopathy. Mol. Neurodegener. 2015;10:55. doi: 10.1186/s13024-015-0052-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schoch KM, Miller TM. Antisense oligonucleotides: translation from mouse models to human neurodegenerative diseases. Neuron. 2017;94:1056–1070. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Novak G, et al. Changes in brain volume with bapineuzumab in mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2016;49:1123–1134. doi: 10.3233/JAD-150448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fox NC, et al. Effects of Aβ immunization (AN1792) on MRI measures of cerebral volume in Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2005;64:1563–1572. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000159743.08996.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sur C, et al. BACE inhibition causes rapid, regional, and non-progressive volume reduction in Alzheimer’s disease brain. Brain. 2020;143:3816–3826. doi: 10.1093/brain/awaa332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Salloway S, et al. A phase 2 randomized trial of ELND005, scyllo-inositol, in mild to moderate Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2011;77:1253–1262. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182309fa5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nave S, et al. Sembragiline in moderate Alzheimer’s disease: results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase II trial (MAyflOwer RoAD) J. Alzheimers Dis. 2017;58:1217–1228. doi: 10.3233/JAD-161309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Doody RS, Farlow M, Aisen PS, Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study Data Analysis and Publication Committee Phase 3 trials of solanezumab and bapineuzumab for Alzheimer’s disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014;370:1460. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1312889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pasquier F, et al. Two phase 2 multiple ascending-dose studies of vanutide cridificar (ACC-001) and QS-21 adjuvant in mild-to-moderate Alzheimer’s disease. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2016;51:1131–1143. doi: 10.3233/JAD-150376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Siemers ER, et al. Phase 3 solanezumab trials: secondary outcomes in mild Alzheimer’s disease patients. Alzheimers Dement. 2016;12:110–120. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2015.06.1893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Leung KK, et al. Cerebral atrophy in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer disease: rates and acceleration. Neurology. 2013;80:648–654. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318281ccd3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nestor SM, et al. Ventricular enlargement as a possible measure of Alzheimer’s disease progression validated using the Alzheimer’s disease neuroimaging initiative database. Brain. 2008;131:2443–2454. doi: 10.1093/brain/awn146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Leng F, Edison P. Neuroinflammation and microglial activation in Alzheimer disease: where do we go from here? Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2021;17:157–172. doi: 10.1038/s41582-020-00435-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zivadinov R, et al. Mechanisms of action of disease-modifying agents and brain volume changes in multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2008;71:136–144. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000316810.01120.05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.De Stefano N, Arnold DL. Towards a better understanding of pseudoatrophy in the brain of multiple sclerosis patients. Mult. Scler. 2015;21:675–676. doi: 10.1177/1352458514564494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Salloway S, et al. Two phase 3 trials of bapineuzumab in mild-to-moderate Alzheimer’s disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014;370:322–333. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1304839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Manning EN, et al. A comparison of accelerated and non-accelerated MRI scans for brain volume and boundary shift integral measures of volume change: evidence from the ADNI dataset. Neuroinformatics. 2017;15:215–226. doi: 10.1007/s12021-017-9326-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Miller TM, et al. Trial of antisense oligonucleotide tofersen for SOD1 ALS. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022;387:1099–1110. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2204705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schobel, S. A. Preliminary results from GENERATION HD1, a phase III trial of tominersen in individuals with manifest HD. In CHDI 16th Annual HD Therapeutics Conference (2021).

- 55.Viglietta, V. A Ph1b/2a study of WVE-003, an investigational allele-selective, mHTT–lowering oligonucleotide for the treatment of early manifest Huntington’s disease, and review of PRECISION-HD results. In CHDI 16th Annual HDTherapeutics Conference (2021).

- 56.Biogen. SPINRAZA. Prescribing information https://www.spinrazahcp.com/content/dam/commercial/spinraza/hcp/en_us/pdf/spinraza-prescribing-information.pdf (2020).

- 57.Tabrizi SJ, et al. Potential disease-modifying therapies for Huntington’s disease: lessons learned and future opportunities. Lancet Neurol. 2022;21:645–658. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(22)00121-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Morris JC, et al. Clinical dementia rating training and reliability in multicenter studies: the Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study experience. Neurology. 1997;48:1508–1510. doi: 10.1212/WNL.48.6.1508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J. Psychiatr. Res. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Albert MS, et al. The diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7:270–279. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bennett CF, Swayze EE. RNA targeting therapeutics: molecular mechanisms of antisense oligonucleotides as a therapeutic platform. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2010;50:259–293. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.010909.105654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wang X, et al. [P4–266]: application of a multi-atlas segmentation tool to hippocampus, ventricle and whole brain segmentation. Alzheimers Dement. 2017;13:P1385–P1386. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary clinical study information.

Data Availability Statement

To request access to data, please visit Vivli. The individual participant data collected during the trial and that support the research proposal will be available to qualified scientific researchers, in accordance with Biogen’s Clinical Trial Transparency and Data Sharing Policy on www.biogentrialtransparency.com. Data requests are initially reviewed by Vivli and Biogen for completeness and other parameters (relating to scope and meeting sponsor policies) and are then reviewed by an Independent Review Panel. Deidentified data, study protocol and documents will be shared under agreements that further protect against participant reidentification, and data are provided in a secure research environment further protecting participant privacy.