Abstract

Background

Sunlight contains ultraviolet B (UVB) radiation that triggers the production of vitamin D by skin. Vitamin D has widespread effects on brain function in both developing and adult brains. However, many people live at latitudes (about > 40 N or S) that do not receive enough UVB in winter to produce vitamin D. This exploratory study investigated the association between the age of onset of bipolar I disorder and the threshold for UVB sufficient for vitamin D production in a large global sample.

Methods

Data for 6972 patients with bipolar I disorder were obtained at 75 collection sites in 41 countries in both hemispheres. The best model to assess the relation between the threshold for UVB sufficient for vitamin D production and age of onset included 1 or more months below the threshold, family history of mood disorders, and birth cohort. All coefficients estimated at P ≤ 0.001.

Results

The 6972 patients had an onset in 582 locations in 70 countries, with a mean age of onset of 25.6 years. Of the onset locations, 34.0% had at least 1 month below the threshold for UVB sufficient for vitamin D production. The age of onset at locations with 1 or more months of less than or equal to the threshold for UVB was 1.66 years younger.

Conclusion

UVB and vitamin D may have an important influence on the development of bipolar disorder. Study limitations included a lack of data on patient vitamin D levels, lifestyles, or supplement use. More study of the impacts of UVB and vitamin D in bipolar disorder is needed to evaluate this supposition.

Background

The sunlight that penetrates the atmosphere and reaches the Earth’s surface has profound effects on human physiology and behavior, and is fundamental to human health (Wirz-Justice 2021). Daylight is the most powerful signal to entrain the human circadian system to the 24 h rotation of the Earth (Foster 2021; Roenneberg 2007). Daylight contains ultraviolet B radiation (UVB) that is absorbed by skin, triggers production of vitamin D, and is the major source of vitamin D for both children and adults (Holick 2017). Some of the many aspects of human health affected by daylight include sleep, mood, alertness, cognition, bone health, calcium homeostasis, neuroendocrine and cardiovascular regulation, and eyesight (Wirz-Justice 2021; Holick 2004; Paul 2019; LeGates 2014; Blume 2019; Crnko 2019; Lagreze 2017).

In prior studies, we analyzed the impact of solar insolation (incoming solar radiation) on several aspects of bipolar I disorder. Solar insolation is defined as the total amount of electromagnetic energy from the Sun striking a surface area of the Earth, and includes all wavelengths of visible and invisible light (NASA 2021). An inverse relation was found between the maximum monthly increase in solar insolation in springtime and the age of onset of bipolar I disorder (Bauer 2017). Due to the frequent symptoms of circadian disruption in patients with bipolar disorder, our studies of solar insolation focused the discussion on visible light and circadian entrainment (Bellivier 2015; Gonzalez 2014; Takaesu 2018).

The purpose of this exploratory analysis was to investigate the association between UVB and the age of onset of bipolar I disorder using a large, global sample. Recent findings emphasize the broad range of non-skeletal vitamin D functions including actions on the developing and adult brain and the association of vitamin D deficiency with neurological and psychiatric disorders (Cuomo 2019; Hoilick 2004; Mayne 2019; Cui 2021; Bailon 2012; Berk 2009; Patrick 2015; Eyles 2020). Although UVB is approximately the same proportion of the total broadband solar insolation at all locations, many people live at latitudes that do not receive enough UVB during winter months to produce vitamin D from skin absorption (Webb 1988; Wacker 2013). The association of the age of onset of bipolar disorder with UVB is of particular importance given the high global rate of vitamin D deficiency (Holick 2017; Palacios 2014), and relevance of the age of onset to the outcome in bipolar disorder (Joslyn 2016; Menculini 2022).

Methods

All patients included in the study had a diagnosis of bipolar disorder made by a psychiatrist according to DSM-IV or DSM-5 criteria. The researchers were from university medical centers and specialty clinics, as well as individual practitioners. Data were collected retrospectively between 2010 and 2016 and 2019–2021, by patient questioning, record review or both. Details about the methodology for data collection were previously published (Bauer 2012; Bauer 2017; Bauer 2022). Study approval, including for data collection, was obtained according to local requirements, using local institutional review boards.

Data collection sites

Data were obtained at 75 data collection sites located in 41 countries in both hemispheres. The data collection sites in the northern hemisphere were in Austria: Graz, Wiener Neustadt; Canada: Calgary, Halifax, Ottawa; China: Hong Kong; Colombia: Medellín; Denmark: Aalborg, Aarhus, Copenhagen; Ethiopia: Barhir Dar; Estonia: Tartu; Finland: Helsinki; France: Paris (2 sites);Germany: Dresden, Frankfurt, Würzburg; Greece: Athens, Thessaloniki (2 sites); India: Bengaluru, Hyderabad, Wardha; Ireland: Dublin; Israel: Beer Sheva; Italy: Cagliari, Sardinia (2 sites), Milan, Piacenza, Rome, Siena; Japan: Tokyo (3 sites); Malaysia: Kuala Lumpur; Mexico: Mexico City; Netherlands: Groningen; Norway: Oslo, Trondheim; Poland: Poznan; Russia: Khanti-Mansiysk; Serbia: Belgrade; Singapore; South Korea: Jincheon; Spain: Barcelona, Vitoria; Sweden; Gothenburg; Stockholm; Taiwan: Taichung; Thailand: Bangkok; Turkey: Ankara; Konya; Tunisia: Tunis; Uganda: Kampala; UK: Glasgow; and USA: Grand Rapids, MI, Iowa City, IA, Kansas City, KS, Los Angeles, CA, Palo Alto, CA, Rochester, MN, San Diego, CA, and Worcester, MA. The collection sites in the southern hemisphere were in Australia: Adelaide, Melbourne/Geelong; Argentina: Buenos Aires; Brazil: Porto Alegre, Salvador, São Paulo; Chile: Santiago (2 sites); Indonesia: Mataram; New Zealand: Christchurch; and South Africa: Cape Town.

Data variables

The data collected for each patient included sex, age of onset, onset location, family history of mood disorders, polarity of first episode, history of psychosis, episode course, history of alcohol and substance abuse, and history of suicide attempts. Four birth cohort groups were used: born before 1940, between 1940 and 1959, between 1960 and 1979, and after 1979.

All the patient actual onset locations were grouped into reference onset locations, which represent all the onset locations within a 1 × 1 degree grid of latitude and longitude. The reference onset location was used to obtain the UVB data for each patient and used in the analysis.

UVB

The surface UVB (280–315 nm) data are estimated by the NASA CERES ((Clouds and Earth’s Radiant Energy System), Wielicki 1996; Su 2005) and were downloaded from the NASA POWER database, based on 20-year Meteorological and Solar Monthly & Annual Climatologies (January 2001—December 2020), and accessed via the POWER Climatology API, Version: v2.2.22 (NASA 2022). For each reference onset location, the monthly average UVB expressed in watts/square meter (W/m2), and the daily average daylight hours for each month were obtained. For consistency with prior research, the average monthly W/m2 values for UVB for each reference site were converted to the average total daily kilojoule/square meter as:

for each month.

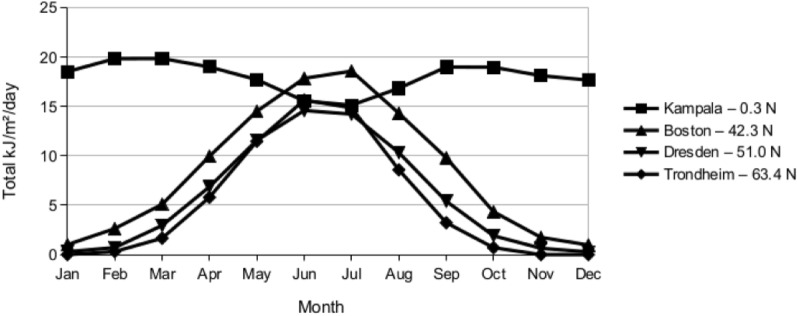

The UVB received at the Earth’s surface varies greatly by geographical location. See Fig. 1. UVB transmission through the atmosphere is greatly reduced by clouds, ozone and heavy air pollution (NASA 2022; Su 2005). For locations at the same latitude with similar cloud patterns, increasing elevation will increase surface UVB.

Fig. 1.

Total UVB kJ/m2/day by Month for Selected Reference Locations

Above approximately 40° latitude N or S, there is insufficient UVB for vitamin D synthesis in winter (November through February in the northern hemisphere) (Webb 1988; Holick 2004). This study analyzed the relation between the threshold for UVB sufficient for vitamin D production in skin and the age of onset of bipolar disorder. Several researchers have estimated thresholds from 0.7 to 1.0 kJ/m2/day UVB (McKenzie 2009; O’Neill 2016). This analysis used a threshold of 0.75 kJ/m2/day UVB.

Statistics

The generalized estimating equations (GEE) statistical technique was used to accommodate the correlated data, and unbalanced number of patients within each reference onset location. The GEE model uses a marginal or population-averaged approach, to estimate the effect across the entire population rather than within a cluster (Zeger 1986). The dependent variable was the age of onset. An exchangeable correlation matrix was selected, which is appropriate for a large number of clusters including many with a single observation (Stedman 2008). Sidak’s adjustment for multiple comparisons was used to make pair-wise comparisons between the birth-cohorts. A significance level of 0.001 was used for all evaluations to reduce the chance of type I error. The corrected quasi-likelihood independence model criterion was used to assist with model fitting (Pan 2001). SPSS version 28.0.0.0 was used for all analyses.

Results

Data for 11,063 patients with bipolar disorder were obtained from the 75 collection sites, including 8080 patients with a diagnosis of bipolar I disorder. Of those with bipolar I disorder, 6972 patients had all variables in the best model. The demographic characteristics of the 6972 patients with bipolar I disorder are shown in Table 1. The mean age of onset for the 6972 patients was 25.6 years, shown distributed by latitude range in Table 2. The 6972 patients had an onset in 582 onset locations in 70 countries. There was a mean of 12 patients at each onset location, with 4% of the 582 locations having only one patient. Of the 6972 patients, 1293 (18.5%) had an onset in the southern hemisphere, and 1598 (22.9%) had an onset in the tropics.

Table 1.

Demographics of Bipolar I patientsa (N = 6972)

| Parameter | Value | N | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Female | 4054 | 58.3 | |

| Male | 2894 | 41.7 | |

| First Episode | |||

| Manic/Hypomanic | 3384 | 50.2 | |

| Depressed | 3358 | 49.8 | |

| Family History of Mood Disorder | |||

| No | 3328 | 47.7 | |

| Yes | 3644 | 52.3 | |

| History of Alcohol or Substance Abuse | |||

| No | 3492 | 69.5 | |

| Yes | 1531 | 30.5 | |

| History of psychosis | |||

| No | 1986 | 35.4 | |

| Yes | 3622 | 64.6 | |

| Comorbid Anxiety/Panic/OCD | |||

| No | 3854 | 77.4 | |

| Yes | 1123 | 22.6 | |

| Cohort Age Group | |||

| DOB after 1979 | 1732 | 24.8 | |

| DOB 1979–1960 | 3234 | 46.4 | |

| DOB 1959–1940 | 1738 | 24.9 | |

| DOB before 1940 | 268 | 3.8 | |

| Onset Hemisphere | |||

| Northern | 5679 | 81.5 | |

| Southern | 1293 | 18.5 | |

| Parameter | Mean | SD | |

| Age of Onset | 25.6 | 10.4 | |

aMissing values excluded

Table 2.

Mean Age of Onset by Latitude Range (N = 6972)

| Latitude Range North + South |

Mean Age of Onset | N | Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0–9 | 26.6 | 511 | 9.97 |

| 10–19 | 24.3 | 797 | 9.49 |

| 20–29 | 24.8 | 375 | 11.39 |

| 30–39 | 25.5 | 2023 | 10.38 |

| 40–49 | 26.6 | 2368 | 10.59 |

| 50–59 | 24.4 | 682 | 10.16 |

| 60–69 | 22.7 | 216 | 11.29 |

| Total | 25.6 | 6972 | 10.43 |

The best fitting model estimated the age of onset using an intercept, 1 or more months of less than 0.75 mean monthly kJ/m2/day of UVB at the patient onset location, family history of mood disorders and patient birth cohort. All estimated coefficients were significant at the P < 0.001 level. The age of onset for patients at an onset location with at least 1 month < 0.75 mean monthly kJ/m2/day of UVB was 1.66 (99% CI [-2.614, -0.712]) years younger than for patients at an onset location elsewhere as shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Estimated parameters explaining age of onset for patients with bipolar I disorder below a threshold of mean monthly kJ/m2/day of 0.75 UVB light for 1 or more months during the year (N = 6972)

| 99% Confidence Interval | Coefficient Significance | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameters | Coefficient estimate (β) | Standard Error | Lower | Upper | Wald Chi-squared | P |

| Intercept | 40.300 | 1.0867 | 38.107 | 42.429 | 1375.305 | < 0.001 |

| Family history of mood disorders | − 1.914 | 0.2316 | − 2.368 | − 1.460 | 68.309 | < 0.001 |

| Cohort age groups | ||||||

| DOB after 1979 | − 19.768 | 1.0344 | − 21.796 | − 17.741 | 365.219 | < 0.001 |

| DOB 1979–1960 | − 13.575 | 1.0509 | − 15.635 | − 11.516 | 166.865 | < 0.001 |

| DOB 1959–1940 | − 7.509 | 1.0339 | − 9.536 | − 5.483 | 52.750 | < 0.001 |

| DOB before 1940 | 0 | |||||

| UVB kJ/m2/day < 0.75 for 1 or more months | − 1.663 | 0.4853 | − 2.614 | − 0.712 | 11.739 | < 0.001 |

Dependent variable: Age of onset (years). Model: intercept, family history of mood disorders (Y/N), cohort age groups, UVB kJ/m2/day < 0.75 for 1 or more months (Y/N). All Sidak pairwise comparisons between family history of mood disorders and cohort age groups were significant at the < 0.001 level

Of the 582 onset locations, 198 (34.0%) had at least 1 month of less than 0.75 mean monthly kJ/m2/day of UVB. All of these onset locations were at latitudes of 40 degrees or greater N or S, and included 2247 (32.2%) of patients.

Discussion

An association between UVB and the age of onset of bipolar disorder was observed. Patients at locations with 1 or more months of less than the threshold for UVB sufficient for vitamin D production had an onset that was 1.66 years younger. However, there are major limitations to this exploratory study. There is no data on patient vitamin D levels, lifestyle, sun exposure, sunscreen use or if taking vitamin D supplements. There is no data on dietary habits, although lower vitamin D levels were reported in vegetarians (Crowe 2011), or on skin pigmentation which effects absorption of UV radiation (Jablonski 2010). There is no data on whether patients take medications that interact with vitamin D such as many anti-epileptic drugs (Wakeman 2021; Fan 2016). There is no data on country vitamin D fortification. Yet, despite these limitations, an association between UVB and the age of onset of bipolar disorder was seen. This suggests that the role of UVB and vitamin D in bipolar disorder needs to be studied.

Vitamin D deficiency is frequently present in patients with psychiatric disorders. Many studies have reported vitamin D deficiency in patients with schizophrenia and major depressive disorder (MDD), with some opposite findings in MDD (Cui 2021; Valipour 2014; Bivona 2019). There are fewer studies of patients with bipolar disorder, but vitamin D status in these patients was similar to that of patients with other psychiatric disorders (Cereda 2021). The frequent medical comorbidity in patients with bipolar disorder may lead to poor eating habits, and limit exercise and sunlight exposure, which may also contribute to findings of vitamin D deficiency (Eyles 2020). Additionally, vitamin D deficiency and insufficiency is very common in international studies of people admitted for inpatient psychiatric treatment (Seiler 2022).

Vitamin D is a neurosteroid that has multiple roles in the brain throughout life. Vitamin D is involved in regulating brain development, maintaining function in the adult brain, and protecting the aged brain (Cui 2021; Eyles 2020; Groves 2014). Vitamin D acts on the brain by both genomic and non-genomic pathways. The genomic pathway involves vitamin D receptors that are found throughout most regions of the brain (Cui 2021; Eyles 2020; Groves 2014). The actions of vitamin D within the brain influence neurotransmission, neuroprotection, synaptic plasticity, immunomodulation, and calcium signaling. This includes involvement of vitamin D in the release of neurotransmitters including dopamine, gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), and serotonin, and neuroprotective effects that suppress oxidative stress and inhibit inflammation (Cui 2021; Eyles 2020; Groves 2014). The role of vitamin D in the development and severity of psychiatric disorders is an area of active research, including for bipolar disorder (Berridge 2017; Berridge 2015; Patrick 2015; Eghtedarian 2022; Eyles 2013).

Other Limitations

Details about vitamin D production, and mechanisms of action in the brain were out of scope. Issues related to vitamin D assay methods, and differences between international guidelines for thresholds and supplementation were not discussed (Guistina 2020; Bouillon 2017). Changing needs for vitamin D across the lifespan, and strategies to address global vitamin D deficiency were not discussed (Bouillon 2017; Mendes 2020). UVB-related pathologies related to excessive exposure including skin cancers and ocular diseases were not discussed (Gies 2018). The potential use of vitamin D supplements as a treatment for bipolar disorder was out of scope (Marsh 2017). The surface UVB values were estimated from available satellite data and may differ slightly from direct surface UVB measurements (Su 2005). The global procedures implemented to prevent depletion of stratospheric ozone and resultant decreases in UVB were not included (Barnes 2019; NASA 2021).

Conclusion

UVB is fundamental to the development of vitamin D, which is widely involved in the regulation of brain activities. In this large global study, patients at locations where the available UVB was below the threshold required for vitamin D production for at least 1 month had a younger age of onset of bipolar I disorder. UVB and vitamin D may have an important influence on the development of bipolar disorder. Further investigation of the role of UVB exposure and vitamin D in bipolar disorder is needed to evaluate this supposition.

Acknowledgements

None.

Author contributions

MB and TG completed the initial draft, which was reviewed by all authors. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. Ole A. Andreassen is supportet by the Research Council of Norway (#223273) and the South Eastern Norway Health Region (#2019–108). Michael Berk is supported by a NHMRC Senior Principal Research Fellowship (1156072). Pierre A. Geoffroy, Chantal Henry and Josselin Houenou received grants from the French Agence Nationale pour la Recherche (ANR-11-IDEX-0004 Labex BioPsy “Olfaction and Bipolar Disorder” collaborative project, ANR-10-COHO-10–01 psyCOH and ANR-DFG ANR-14-CE35–0035 FUNDO). Seong Jae Kim is supported by research funds from the Institute of Medical Science, Chosun University, Republic of Korea, 2022. Mok Yee Ming, Mythily Subramaniam, and Wen Lin Teh received funding from the National Medical Research Centre (NMRC) Centre Grant (Ref No: NMRC/CG/M002/ 2017_IMH). Raj Ramesar is supported by the South African Department of Science and Innovation and Medical Research Council. Eduard Vieta acknowledges the support by CIBER -Consorcio Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red- (CB07/09/0004), Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation. EV thanks the support of the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (PI18/00805, PI21/00787) integrated into the Plan Nacional de I + D + I and co-financed by the ISCIII-Subdirección General de Evaluación and the Fondo Europeo de Desarrollo Regional (FEDER); the Instituto de Salud Carlos III; the Secretaria d'Universitats i Recerca del Departament d'Economia i Coneixement (2017 SGR 1365), the CERCA Programme, and the Departament de Salut de la Generalitat de Catalunya for the PERIS grant SLT006/17/00357. Thanks the support of the European Union Horizon 2020 research and innovation program (EU.3.1.1. Understanding health, wellbeing and disease: Grant No 754907 and EU.3.1.3. Treating and managing disease: Grant No 945151). Biju Viswanath is supported by the Intermediate (Clinical and Public Health) Fellowship (IA/CPHI/20/1/505266) of the DBT/ Wellcome Trust India Alliance.

Availability of data and materials

The data will not be shared or made publicly available.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

The authors provide consent for publication.

Competing interests

Eric D. Achtyes has served on advisory boards or consulted for Alkermes, Atheneum, Janssen, Karuna, Lundbeck/Otsuka, Roche, Sunovion and Teva. He has received research support from Alkermes, Astellas, Biogen, Boehringer-Ingelheim, InnateVR, Janssen, National Network of Depression Centers, Neurocrine Biosciences, Novartis, Otsuka, Pear Therapeutics, and Takeda. Ole A. Andreassen is a consultant to CorTechs.ai and has received speakers honorarium from Janssen, Lundbeck, and Sunovion. Alessandro Cuomo is /has been a consultant and/or a speaker and/or has received research grants from Angelini, Glaxo Smith Kline, Italfarmaco, Lundbeck, Janssen, Mylan, Neuraxpharm, Otsuka, Pfizer, Recordati, Sanofi Aventis, Viatris. Andrea Fagiolini is /has been a consultant and/or a speaker and/or has received research grants from Angelini, Apsen, Boheringer Ingelheim, Glaxo Smith Kline, Italfarmaco, Lundbeck, Janssen, Mylan, Neuraxpharm,Otsuka, Pfizer, Recordati, Sanofi Aventis, Viatris, Vifor. Lars Vedel Kessing has within the preceeding three years been a consultant for Lundbeck and Teva. Rasmus W. Licht has received research grants from Glaxo Smith Kline, honoraria for lecturing from Pfizer, Glaxo Smith Kline, Eli Lilly, Astra-Zeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Janssen Cilag, Lundbeck, Otsuka, Servier and honoraria from advisory board activity from Glaxo Smith Kline, Eli Lilly, Astra-Zeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Janssen Cilag, Sunovion and Sage. Richard J. Porter has received research software by SBT-pro, and travel support from Servier and Lundbeck. Andreas Reif has received honoraria for ad boards and talk from Medice, Shire/Takeda, Janssen, LivaNova, Boehringer, SAGE/Biogen, cyclerion and COMPASS. Eduard Vieta has received grants and served as consultant, advisor or CME speaker for the following entities: AB-Biotics, AbbVie, Adamed, Angelini, Biogen, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Celon Pharma, Compass, Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma, Ethypharm, Ferrer, Gedeon Richter, GH Research, Glaxo-Smith Kline, Janssen, Lundbeck, Medincell, Merck, Novartis, Orion Corporation, Organon, Otsuka, Roche, Rovi, Sage, Sanofi-Aventis, Sunovion, Takeda, and Viatris, outside the submitted work. All other authors report no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Balion C, Griffith LE, Strifler L, Henderson M, Patterson C, Heckman G, Llewellyn DJ, Raina P. Vitamin D, cognition, and dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurology. 2012;79(13):1397–1405. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31826c197f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes PW, Williamson CE, Lucas RM, Robinson SA, Madronich S, Paul ND, Bornman JF, Bais AF, Sulzberger B, Wilson SR, Andrady AL. Ozone depletion, ultraviolet radiation, climate change and prospects for a sustainable future. Nat Sustain. 2019;2(7):569–579. doi: 10.1038/s41893-019-0314-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer M, Glenn T, Alda M, Andreassen OA, Ardau R, Bellivier F, et al. Impact of sunlight on the age of onset of bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2012;14:654–663. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2012.01025.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer M, Glenn T, Alda M, Aleksandrovich MA, Andreassen OA, Angelopoulos E, et al. Solar insolation in springtime influences age of onset of bipolar I disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2017;136:571–582. doi: 10.1111/acps.12772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer M, Glenn T, Achtyes ED, Alda M, Agaoglu E, Altınbaş K, et al. Association between polarity of first episode and solar insolation in bipolar I disorder. J Psychosom Res. 2022;160:110982. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2022.110982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellivier F, Geoffroy PA, Etain B, Scott J. Sleep- and circadian rhythm-associated pathways as therapeutic targets in bipolar disorder. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2015;19(6):747–763. doi: 10.1517/14728222.2015.1018822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berk M. Vitamin D: Is it relevant to psychiatry? Acta Neuropsychiatr. 2009;21:205–206. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-5215.2009.00402.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berridge MJ. Vitamin D cell signalling in health and disease. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2015;460(1):53–71. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berridge MJ. Vitamin D and depression: cellular and regulatory mechanisms. Pharmacol Rev. 2017;69(2):80–92. doi: 10.1124/pr.116.013227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bivona G, Gambino CM, Iacolino G, Ciaccio M. Vitamin D and the nervous system. Neurol Res. 2019;41(9):827–835. doi: 10.1080/01616412.2019.1622872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blume C, Garbazza C, Spitschan M. Effects of light on human circadian rhythms, sleep and mood. Somnologie. 2019;23(3):147–156. doi: 10.1007/s11818-019-00215-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouillon R. Comparative analysis of nutritional guidelines for vitamin D. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2017;13(8):466–479. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2017.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cereda G, Enrico P, Ciappolino V, Delvecchio G, Brambilla P. The role of vitamin D in bipolar disorder: Epidemiology and influence on disease activity. J Affect Disord. 2021;278:209–217. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Crnko S, Du Pré BC, Sluijter JPG, Van Laake LW. Circadian rhythms and the molecular clock in cardiovascular biology and disease. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2019;16(7):437–447. doi: 10.1038/s41569-019-0167-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowe FL, Steur M, Allen NE, Appleby PN, Travis RC, Key TJ. Plasma concentrations of 25-hydroxyvitamin D in meat eaters, fish eaters, vegetarians and vegans: results from the EPIC–Oxford study. Public Health Nutr. 2011;14(2):340–346. doi: 10.1017/S1368980010002454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui X, McGrath JJ, Burne THJ, Eyles DW. Vitamin D and schizophrenia: 20 years on. Mol Psychiatry. 2021;26(7):2708–2720. doi: 10.1038/s41380-021-01025-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuomo A, Fagiolini AJ. Vitamin D and psychiatric illnesses. Vitamin D UpDates. 2019;21(22):25–30. https://www.vitamind-journal.it/en/wpcontent/uploads/2019/04/03_Fagiolini_1_19_EN-2.pdf. Accessed 28 May 2023.

- Eghtedarian R, Ghafouri-Fard S, Bouraghi H, Hussen BM, Arsang-Jang S, Taheri M. Abnormal pattern of vitamin D receptor-associated genes and lncRNAs in patients with bipolar disorder. BMC Psychiatry. 2022;22(1):178. doi: 10.1186/s12888-022-03811-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eyles DW. Vitamin D: brain and Behavior. JBMR plus. 2020;5(1):e10419. doi: 10.1002/jbm4.10419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eyles DW, Burne TH, McGrath JJ. Vitamin D, effects on brain development, adult brain function and the links between low levels of vitamin D and neuropsychiatric disease. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2013;34(1):47–64. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2012.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan HC, Lee HS, Chang KP, Lee YY, Lai HC, Hung PL, Lee HF, Chi CS. The impact of anti-epileptic drugs on growth and bone metabolism. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17(8):1242. doi: 10.3390/ijms17081242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster RG. Fundamentals of circadian entrainment by light. Light Res Technol. 2021;53(5):377–393. doi: 10.1177/14771535211014792. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gies P, van Deventer E, Green AC, Sinclair C, Tinker R. Review of the Global Solar UV Index 2015 Workshop Report. Health Phys. 2018;114(1):84–90. doi: 10.1097/HP.0000000000000742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giustina A, Bouillon R, Binkley N, Sempos C, Adler RA, Bollerslev J, Dawson-Hughes B, Ebeling PR, Feldman D, Heijboer A, Jones G, Kovacs CS, Lazaretti-Castro M, Lips P, Marcocci C, Minisola S, Napoli N, Rizzoli R, Scragg R, White JH, Formenti AM, Bilezikian JP. Controversies in Vitamin D: a statement from the third international conference. JBMR plus. 2020;4(12):e10417. doi: 10.1002/jbm4.10417.PMID:33354643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez R. The relationship between bipolar disorder and biological rhythms. J Clin Psychiatry. 2014;75(4):e323–e331. doi: 10.4088/JCP.13r08507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groves NJ, McGrath JJ, Burne TH. Vitamin D as a neurosteroid affecting the developing and adult brain. Annu Rev Nutr. 2014;34:117–141. doi: 10.1146/annurev-nutr-071813-105557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holick MF. Sunlight and vitamin D for bone health and prevention of autoimmune diseases, cancers, and cardiovascular disease. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;80(6 Suppl):1678S–S1688. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/80.6.1678S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holick MF. The vitamin D deficiency pandemic: Approaches for diagnosis, treatment and prevention. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2017;18(2):153–165. doi: 10.1007/s11154-017-9424-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jablonski NG, Chaplin G. Human skin pigmentation as an adaptation to UV radiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;2(Suppl 2):8962–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914628107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joslyn C, Hawes DJ, Hunt C, Mitchell PB. Is age of onset associated with severity, prognosis, and clinical features in bipolar disorder? A Meta-Analytic Review Bipolar Disord. 2016;18(5):389–403. doi: 10.1111/bdi.12419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagrèze WA, Schaeffel F. Preventing Myopia. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2017;114(35–36):575–580. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2017.0575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeGates TA, Fernandez DC, Hattar S. Light as a central modulator of circadian rhythms, sleep and affect. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2014;15(7):443–454. doi: 10.1038/nrn3743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh WK, Penny JL, Rothschild AJ. Vitamin D supplementation in bipolar depression: A double blind placebo controlled trial. J Psychiatr Res. 2017;95:48–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2017.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayne PE, Burne THJ. Vitamin D in Synaptic Plasticity, Cognitive Function, and Neuropsychiatric Illness. Trends Neurosci. 2019;42(4):293–306. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2019.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenzie RL, Liley JB, Björn LO. UV radiation: balancing risks and benefits. Photochem Photobiol. 2009;85(1):88–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.2008.00400.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menculini G, Verdolini N, Gobbicchi C, Del Bello V, Serra R, Brustenghi F, Armanni M, Spollon G, Cirimbilli F, Brufani F, Pierotti V, Di Buò A, De Giorgi F, Sciarma T, Moretti P, Vieta E, Tortorella A. Clinical and psychopathological correlates of duration of untreated illness (DUI) in affective spectrum disorders. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2022;61:60–70. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2022.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendes MM, Charlton K, Thakur S, Ribeiro H, Lanham-New SA. Future perspectives in addressing the global issue of vitamin D deficiency. Proc Nutr Soc. 2020;79(2):246–251. doi: 10.1017/S0029665119001538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NASA, The Power Project. https://power.larc.nasa.gov/. 2022. Accessed 28 May 2023.

- NASA-funded Network Tracks the Recent Rise and Fall of Ozone Depleting Pollutants. 2021. https://www.nasa.gov/feature/goddard/2021/nasa-funded-network-tracks-the-recent-rise-and-fall-of-ozone-depleting-pollutants. Accessed 28 May 2023.

- O'Neill CM, Kazantzidis A, Ryan MJ, Barber N, Sempos CT, Durazo-Arvizu RA, Jorde R, Grimnes G, Eiriksdottir G, Gudnason V, Cotch MF, Kiely M, Webb AR, Cashman KD. Seasonal changes in vitamin D-effective UVB availability in Europe and associations with population serum 25-Hydroxyvitamin D. Nutrients. 2016;8(9):533. doi: 10.3390/nu8090533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palacios C, Gonzalez L. Is vitamin D deficiency a major global public health problem? J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2014;144 pt A:138–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2013.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan W. Akaike's information criterion in generalized estimating equations. Biometrics. 2001;57(1):120–125. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.2001.00120.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick RP, Ames BN. Vitamin D and the omega-3 fatty acids control serotonin synthesis and action, part 2: relevance for ADHD, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, and impulsive behavior. FASEB J. 2015;29(6):2207–2222. doi: 10.1096/fj.14-268342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul S, Brown TM. Direct effects of the light environment on daily neuroendocrine control. J Endocrinol. 2019;243(1):R1–8. doi: 10.1530/JOE-19-0302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roenneberg T, Kumar CJ, Merrow M. The human circadian clock entrains to sun time. Curr Biol. 2007;17(2):R44–R45. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seiler N, Tsiglopoulos J, Keem M, Das S, Waterdrinker A. Prevalence of vitamin D deficiency among psychiatric inpatients: a systematic review. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2022;3:1–7. doi: 10.1080/13651501.2021.2022701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stedman MR, Gagnon DR, Lew RA, Solomon DH, Brookhart MA. An evaluation of statistical approaches for analyzing physician-randomized quality improvement interventions. Contemp Clin Trials. 2008;29(5):687–695. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2008.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su W, Charlock TP, Rose FG. Deriving surface ultraviolet radiation from CERES surface and atmospheric radiation budget Methodology. J Geophys Res Atmospheres. 2005 doi: 10.1029/2005JD005794. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Takaesu Y. Circadian rhythm in bipolar disorder: a review of the literature. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2018;72(9):673–682. doi: 10.1111/pcn.12688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valipour G, Saneei P, Esmaillzadeh A. Serum vitamin D levels in relation to schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99(10):3863–3872. doi: 10.1210/jc.2014-1887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wacker M, Holick MF. Sunlight and Vitamin D: A global perspective for health. Dermatoendocrinol. 2013;5(1):51–108. doi: 10.4161/derm.24494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakeman M. A literature review of the potential impact of medication on vitamin D status. Risk Manag Healthc Policy. 2021;14(14):3357–3381. doi: 10.2147/RMHP.S316897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb AR, Kline L, Holick MF. Influence of season and latitude on the cutaneous synthesis of vitamin D3: exposure to winter sunlight in Boston and Edmonton will not promote vitamin D3 synthesis in human skin. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1988;67(2):373–378. doi: 10.1210/jcem-67-2-373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wielicki BA, Barkstrom BR, Harrison EF, Lee RGB, III, Smith GL, Cooper JE. Clouds and the Earth’s Radiant Energy System (CERES): An Earth Observing System Experiment. Bull Amer Meteor Soc. 1996;77:853–868. doi: 10.1175/1520-0477(1996)077<0853:CATERE>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wirz-Justice A, Skene DJ, Münch M. The relevance of daylight for humans. Biochem Pharmacol. 2021;191:114304. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2020.114304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeger SL, Liang KY. Longitudinal data analysis for discrete and continuous outcomes. Biometrics. 1986;42:121–30. [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data will not be shared or made publicly available.